By Ruth Catlow and Elly Clarke

Elly and Ruth have been organising workshops and conversations for Furtherfields’ latest project in Felixstowe, Reimagine This Coastal Town. This correspondence followed a 2-day workshop that took place in December 2025 at Hamilton MAS with artists and young visionaries from Felixstowe and East Anglia, exploring crossovers in art and ecology, and possible futures of the town. Creative Participants: Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Elly Clarke (co-curators and hosts); Lora Aziz Josh Hall (Possible Worlds) and Simon Read. Young Visionaries: Lily Hammond, Courtney Hessey and Stan Willey.

Elly: Monday 5th January, 2026

It’s not yet been a month since our two-day co-creation workshop in December, but it already feels so long ago. Christmas happened. Betwixmas happened. And the New Year happened. And then the Venuzeulan president was kidnapped in an extraordinary Stranger Things-style military ambush led by the US president, and the world is waiting for the next rupture [which turned out to be the violently suppressed uprising in Iran.] This is the world we live in, breathe in, are trying to survive in, trying to remain calm in, keep healthy in, care in, look after our bodies and the bodies of others and other species in. But it is also the world we are resilient in. The world we are creating in, imagining in, dreaming in, loving in and living in. The unignorable multiple troubles of our current era – ecological, political, economic, and technological – mean that more and more people are talking about the things that are not working… And these, I believe, are the cracks where (to reference Leonard Cohen) the light can get in. Discussion about the desire for change is entering more and more conversations – and that is a good thing.

For me, and I think for the others, the workshop provided a moment of pause, of calm, of happy being together-ness with people I knew, and people I didn’t. We intentionally structured the workshop only loosely, to give space and time to acknowledge the many ills of our times, but also, importantly, to feel what we actually are feeling in this context. The result was the embodied, palpable sense that so long as we keep meeting and being together over a selection of teas, oranges, and Stan’s delish homemade curry, and forget about the 1-hour meeting format with strictly prescribed lists of actions, we might just be ok.

Thinking together, and sharing collective experiences with people aged in their 20s to 70s made time expand in a way that most templates of organisation today do not allow. Through Simon, we were taken to 1980s Thatcher’s London with the closing down of art spaces. As he was talking I thought of Derek Jarman’s films from that period, and earlier – [for example, Studio Bankside, 1971, which shows the gritty post-industrial site of what is now Tate Modern, occupied by queer punks gleefully cavorting around burning barrels] – even though I don’t think he was part of that scene. Meanwhile, Courtney, who has lived in Felixstowe all her life, speaks for the people she meets. She asks, “but when are we actually going to do these things? What is the action?”

Workshop lunch – Reimagine This Coastal Town Co-creation workshop in Felixstowe, December 2025

Ruth: Thursday 8th January

Yes Elly, I was struck too, by Courtney’s sense of urgency for action.

I’ve just got back from the Listening to the Land Day, a symposium dedicated to artistic and scientific animist practices (as part of the Oxford Real Farming Conference for agroecology and food sovereignty). There, I was reminded that imagination is the place where reality starts for us, and from where we create the blueprint for our actions. When we discuss our hopes and desires with others, we seed patterns in the imaginal realm.

During our workshop at Hamilton MAS, we seeded patterns for future conversations, imaginings, and action not only with other townspeople but also the more-than-human life in the town and its surroundings.

Everyone made crucial contributions to the development of our upcoming public art commission in Felixstowe. The ideas flowed and grew between us as we discussed the proposal by one of our younger LARP participants last spring called Rewilding the Ruins. This proposal also inspired and enthused visitors to our exhibition last summer. The act of ceding sites abandoned by humans to other creatures of the town honours human heritage while recognising the biodiverse communities that emerge and thrive there. Lora suggested the term “renaturing” rather than “rewilding,” as we are prioritising biodiversity in relatively small sites rather than introducing apex predators to large areas of land.

Hopefully, the artwork that Lily goes on to make will not only inspire everyone in the town to get involved in our creative activities and other practical environmental actions, but also support a conversation about how everyone can make simple but important nature-connections – just by turning curious attention to the other lives that thrive in these places.

Life loves to be appreciated! Noticing and appreciation are the first steps to caring.

There was a moment in the workshop where I heard you talk about the importance of love. We were talking about political developments down the English East coast and the wider Earth crisis, and how to “stay with the troubles”.

You asked, “How can we care for anything if we don’t first love it?”

This really struck me because after years of working with critical practice in the artworld I was shocked to realise how rare it is to hear someone talk about love. And when the embers of love fade, the world becomes arid, and our eyes and hearts dull.

Noticing and appreciating the brambles that provide food and shelter for insects and birds around the old military placements of Landguard, and the peacock butterflies that overwinter there, and loving the magical foxes that make their homes in the quiet spaces of abandoned railway stations might be the most important thing anyone can do.

There’s already such a spirited mutualism here in places like Cuppa, our community cafe, and community growing project Edible Felixstowe. And plans are afoot for other inspiring projects to create new pathways for young people to make this town their own in imaginative and creative ways. By generating loving attention and care for other beings, we aim to create the conditions necessary to support these emerging plans for coordinated, human and more-than-human action in the town.

And so the things that remain with me from that day are: Josh’s rage for the cruelty of the politics on the streets of Great Yarmouth and the creative and loving social engine, he and his partner Gabby have established to counter that cruelty, with good food served at a mutual aid cafe (visit the Bakehouse) and bitingly funny poster campaigns; the light in Lora’s eyes, she talked about clambering through barbed wire and brambles to the source of her beloved local river, and the importance of regular encounters with that spring to her spirit. Also, the joy of introducing a group of school children to plum trees, having them pick and taste them for the first time; Lily’s calm love of beauty, pattern and colour in the lives of other beings; Stan’s quick, imaginative, and inspiring transformation of proposals into plans he would like to realise for a local permaculture, growing, and anarchist zine production project. Simon’s slow (years-long) conversations with the estuary are based on a deep ecological knowledge and relationship gained over decades. All contrasting with, and complemented by, Courtney’s sense of urgency.

I realise there is something we can do right now – all of us – and that is to greet the birds as friends every morning. Get to know individuals, observe their ways, learn what they do and what they like, and where they live. We can do that already – all of us – without any additional money, resources, knowledge, plans – and we will probably find ourselves more connected and alive.

Billboards in Felixstowe – with artists Elly Clarke, Simon Read, Josh Hall, Lora Aziz, Ruth Catlow, with Nick the dog.

Elly: Saturday 20th Jan

Hi Ruth,

This sentence: imagination is the place where reality starts for us, and from there we create the blueprint for our actions. is where I want to start… Because I love the poetry of the fact that it was at a Real Farming Conference that you were reminded of imagination being a blueprint for everything. Because to nurture growth – of plants, of ideas, and of communities of all species – requires a balance of care and knowledge, but is also subject to many factors beyond anybody’s control: the weather, climate, labour, health and, increasingly, politics. In the case of Yarmouth, where Josh and his project are literally feeding love to the local community through food, space and shelter, love meets and has to (try to) negotiate with [the largely unloving views of] the right-wing whose flag/ging erections repeatedly signpost their presence. Whilst Felixstowe is not currently suffering this degree of extremism, it would be remiss of us, and irresponsible, not to acknowledge that this is part of the wider context (and climate) our project is landing in.

Your descriptions of Lora’s joy at the climbing over barbed wire to her beloved spring, (and the video of her dipping her child’s feet into it); Stan’s zines and Simon’s slow, ongoing encounters with life (and lives) of the estuary – and Courtney’s urgency, alongside the spirit of mutualism you highlight – are all fuelled by love. As I said in the workshop, I do think that love never gets enough acknowledgement or space when discussing art and nature, and the climate crisis. Love is about noticing – as you say, the brambles, the birds, others around you. It is about at/tending to what is around us. Love naturally inspires and invokes interest and curiosity, which is crucial to the desire and labour of building a better world. So perhaps if Love got more of a look in, if s/he could be part of our group with a name badge pinned to hir chest, we could ensure s/he was involved in all aspects of planning and dreaming, which could offer some important signposting when we need it….

And Lily, when delivering the final edits to her incredible artwork these past days, spoke passionately about how the work was created out of ‘so much love’ – which is evident and palpable. So love is in the work we are doing here. The mentor species are wearing it. The colours are showing it. The fox’s steady gaze holds it. The ruins of Felixstowe are receiving it.

Lunch with Bryony Graham, Director of Hamilton MAS, with Ruth Catlow, Simon Read, Stan Willey, Josh Hall and Lora Aziz.

Ruth: Wednesday 31 January

Yes, Elly, yes!

And to close, I want to reflect on a familiar criticism: that directing our imaginative attention toward interspecies thriving somehow diminishes or distracts from the urgent political struggles of humans across the globe. As if care were a choice, and as if we must decide between loving other people and loving other beings on this planet.

After six or seven years of working with creative practices for interspecies justice, I have learned the opposite. When we come to understand our well-being as bound up with that of other species, we gain sharper insight into the many dimensions and mechanisms of oppression that operate within human societies as well. And we discover that love is not a zero-sum game – not a finite resource. Loving other beings opens new ways of loving, new imaginaries for care and new capacities for justice.

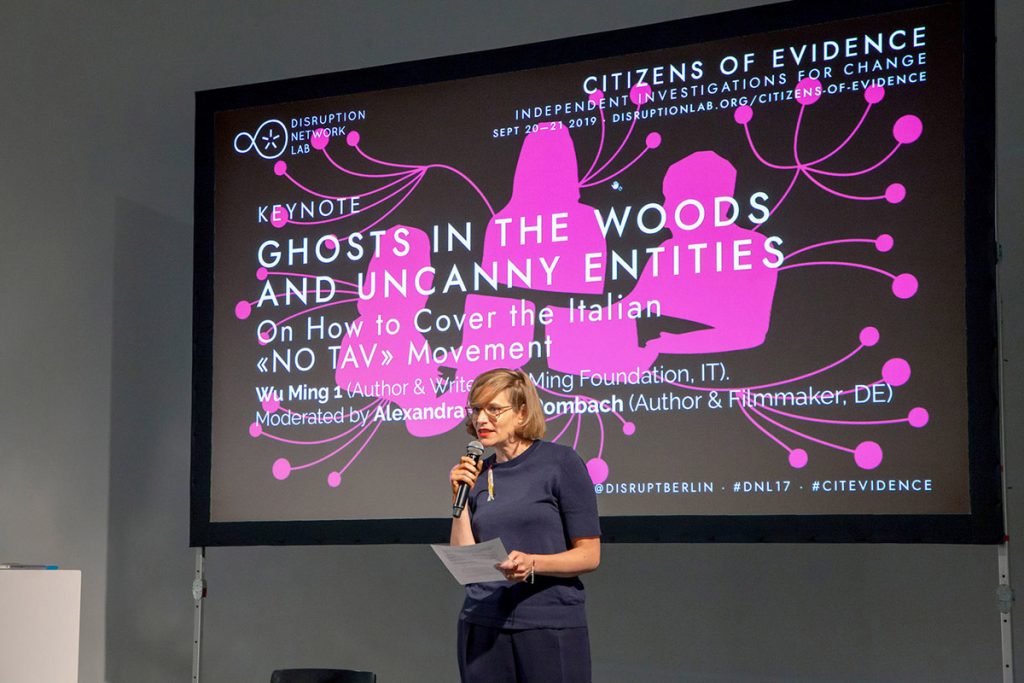

The 21st conference of the Disruption Network Lab “Borders of Fear” was held on the 27th, 28th, and 29th November 2020 in Berlin’s Kunstquartier Bethanien. Journalists, activists, advocates, and researchers shed light on abuses and human rights violations in the context of migration management policies. Keynote speeches, panel discussions and several workshops were held involving a total number of 18 speakers and bringing together hundreds of online viewers.

Drawing on insights from humanities, science and technology studies, participants analysed from different perspectives the spread of new forms of persecution and border control targeting people on the move and those seeking refuge. They reflected collectively on forms of social justice and discussed the politics of fear that crystalize the stigmatisation of migrants. By concretely addressing these issues the conference also investigated the deployment of technology and the role of media to consolidate a well-defined structure of power, and outlined the reasons behind the rise of borders and walls, factors that lead to cultural and physical violence, persecution, and human rights violations.

In her introductory statement Dr. Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder and director of the Distruption Network Lab, presented the programme of the conference meant to address the discourse of borders both in their material function, and in their defining role within a strategy of dehumanization and racialisations of individuals. Across the globe, an unprecedented number of people are on the move due to war, economic and environmental factors. Bazzichelli recalled the urgent need to discuss human-right-related topics such as segregation and pushbacks, refugee camps and militarization of frontiers, considering the new technological artilleries available for states, investigating at the same time how border policing and datafication of society are affecting the narrative around migrants and refugees in Europe and the in the West.

The four immediate key content takeaways of the first day were the will to prevent people from reaching countries where they can apply for refugee status or visa; the externalisation polices of border control; the illegal practice of pushbacks; and systematic human rights violations by authorities, extensively documented but difficult to prove in court.

The conference opened with the short film by Josh Begley “Best of Luck with the Wall” – a voyage across the US-Mexico border – stitched together from 200,000 satellite images, and a talk by lawyer Renata Avila, who gave an overview of the physical and socio-economic barriers, which people migrating encounter whilst crossing South and Central America.

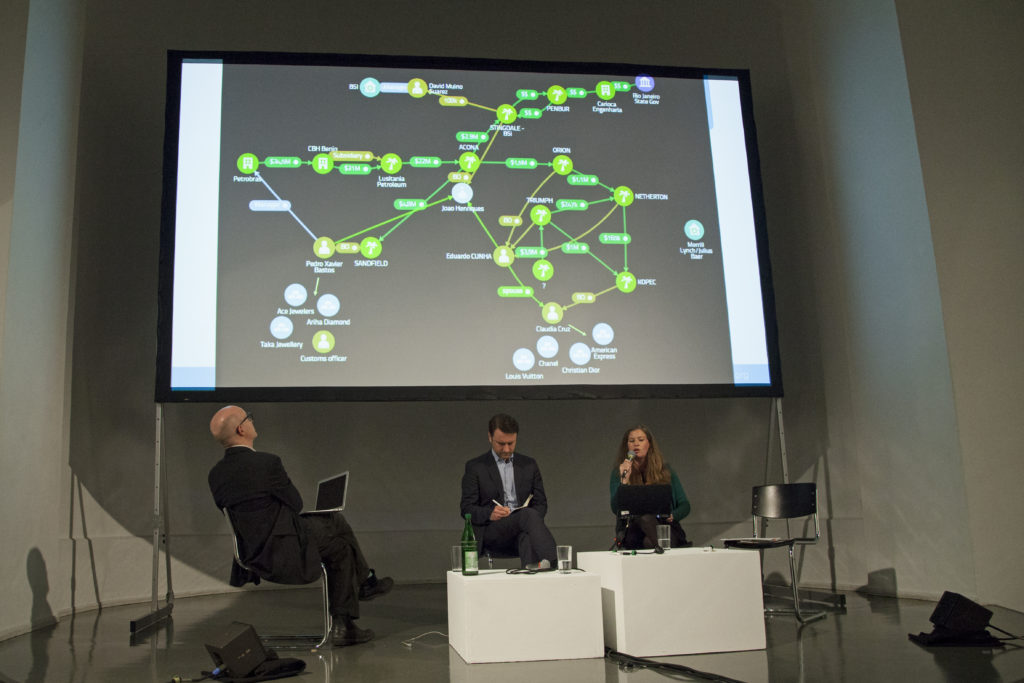

Avila took step from the current crises in South and Central America, to describe the dramatic migration through perilous regions, a result of an accumulation of factors like inequality, corruption, mafia, and violence. Avila pointed out that oligarchic systems from different countries appear to be interconnected in complicated architectures of international tax evasion, ruthless exploitation of resources, oppression, and the use of force. In those same places, people experience the most brutal inequality, poverty and social exclusion.

Since the ‘90s the regional free trade agreement meant open borders for products but not for people. In fact, it was an international policy with devastating effects on local economies and agriculture. People on the move in search for a better future somewhere else found closed borders and security forces attempting to block them from heading north towards Mexico and the U.S. border. In these years, the police forceful response to the migrants crossing borders have been widely praised by the governments in the region.

The fact of travelling alone is a red flag, especially for women, and the first wall people meet is in their own country. People on their way to the north experience every kind of injustice. Latin America has often been regarded as a region with deep ethnic and class conflicts. Abandoning possible stereotypical representations, we see that the bodies of the people on the move are at large sexualised and racialized for political reasons. Race, therefore, is another factor to consider, especially when we look at the journey of individuals on the move. Aside, languages in South America could also represent a barrier for those who travel without translators in a continent with dozens of indigenous languages.

Avila concluded her intervention mentioning the issue of digital colonialism and the relevance of geospatial data. Digital is no longer a separated space, she warned, but a hybrid one relevant for all individuals and whose rules are dictated by a small minority. People and places can be erased by those very few companies that can collect data, and –for example– draw and delete borders.

The panel on the first day titled “Migration, Failing Policies & Human Rights Violations,” was moderated by Roberto Perez-Rocha, director for the international anti-corruption conference series at Transparency International, and delivered by Philipp Schönberger and Franziska Schmidt, coordinators of the Refugee Law Clinic Berlin, together with investigative journalist and photographer Sally Hayden. The panellists referred to their direct experience and work, and reflected on how the EU migration policy is factually enforcing practices that cause violation of human rights, suffering, and desperation.

The Refugee Law Clinic Berlin e. V. is a student association at the Humboldt University of Berlin, providing free of charge and independent legal help for refugees and people on the move in Berlin and on the Greek island of Samos. The organisation also offers training on asylum and residence law in Berlin and runs the website ihaverights.eu, designed to allow access to justice to those in marginalised communities.

Through a legal counselling project on the Greek island of Samos, the collective helps people suffering from European illegal practices at the Union’s borders, providing the urgent need of effective ways to guarantee them access to justice and protection. As Schönberger and Schmidt recalled, refugees, and people on the move within the EU find several obstacles when it comes to the enforcement of their rights. For such a reason, they shall be guaranteed procedural counselling by the law to secure, among other services, a fair asylum procedure. However, the Clinic confirmed that such guarantees are not being completely fulfilled in Germany, nor at Europe’s borders, in Samos, Lesvos, Leros, Kos, or Kios.

The panellists explained how their presence on the island gives a chance to document that these camps of human suffering are actually a structural part of an EU migration policy aimed at deterring people from entering the Union, result of deliberate political decisions taken in Brussels and Berlin. Human rights violations occur before arriving on the island, as people are intercepted by the Greek coastguard or by the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), and then pushed back to the Turkish border.

The camp in Samos, with a capacity of a maximum 648 people, is instead the home to 4,300 residents, with no water, no sanitary services, poisonous food, and no medical services. Even very serious cases documented to local health authorities remain unattended. The list of violations is endless and the complete lack of adequate protection for unaccompanied minors represents another big issue in this like in all others Greek hotspots, together with the precarity of vulnerable groups, whose risks increase with race, gender, and sexual identity.

The legal team from Berlin prepares applications to the EUCHR court and in these years has filed also 60 requests for urgent procedure due to the risk of irreparable harm, which were granted, ordering adequate accommodation and medical treatment for people in extreme danger.

Many observers criticise that the sufferings in the Aegean and on the Greek islands is the result of precise political decisions. Agreed in March 2016, the EU-Turkey deal is a statement of cooperation that seeks to control the crossing of people from Turkey to the Greek islands. According to the deal, every person arriving without documents by boat or without official permission or passage to the Greek islands would be returned to Turkey. In exchange, EU Member States would take Syrian refugees from Turkey. NGOs and international human rights agencies denounce that Turkey, Greece, and the EU have completely failed on humanitarian grounds and dispute the wrong premise that Turkey is a safe country for refugees and asylum-seekers.

Journalist and photographer Sally Hayden looked at the EU-Turkey deal, defining it as a prototype for what would then happen in the central Mediterranean. Libya, a country at war with multiple governments, is the destination of people on move and refugees from all over Africa, willing to cross the Mediterranean Sea. As it is illegal to stop and push people back, for years now the EU has been financing the Libyan coastguard to intercept and pull them back. What follows is a period of arbitrary and endless detention.

Hayden writes about facts; she is not an activist. When she talks about Libya, she refers to objective events she can fact check, and individual stories she has personally collected. Her reports represent a country at war, unsafe not just for refugees and people on the move but for Libyans too. With her work, the journalist has extensively documented how refugees and migrants smuggled into Libya are subject to human trafficking, forced labour, sexual exploitation and tortures, trapped in an infernal circle of violence and death. She recalled her experience with the detainees in Abu Salim, where 500 hundred people suffer from illegal and brutal incarceration inside a centre affiliated with the government in Tripoli. In July 2020, during the conflict, one of these many prisons not far from the city was bombed. At least 53 illegally detained people were killed.

Hayden’s work provides a picture of the results of Europe’s management of the migration crises in the Mediterranean and Northern Africa. EU funds are employed for militarization of borders and externalisation of frontiers control. The political context, in which this occurs, is the cause of years and sometimes decades of lack of investment in reception and asylum systems in line with EU-State’s generic obligations to respect, protect and fulfil human rights.

All panellists called for the immediate intervention to evacuate camps and prisons that were the result of the EU migration policies, to allow migrant victims of abuses and refugees to seek justice and safety elsewhere.

The evening closed with the panel discussion titled “Illegal Pushbacks and Border Violence” and moderated by Likhita Banerji, a human rights and technology researcher at Amnesty International. Banerji reminded the audience that in the first nine months of 2020 there had already been 40 pushbacks, illegal rejections of entry, and expulsions without individual assessment of protection needs, had been documented within Europe or at its external borders. Since these illegitimate practices are widespread, and in some countries systematic, these pushbacks cannot be defined as incidental actions. They appear, instead, to be institutionalised violations, well defined within national policies.

People who shall receive asylum or be rescued, are instead pushed back by police forces, who make sure that the material crossing of the borders remains undocumented. EU member States want to keep undocumented migrants, asylum seekers and refugees outside of their jurisdiction to avoid moral responsibilities and legal obligations. During the second panel of the day, Hanaa Hakiki, legal advisor at the ECCHR Migration Program, filmmaker and reporter Nicole Vögele, and Dimitra Andritsou, researcher at Forensic Architecture, had the chance to go in-depth and to consider the different aspects of these violations.

Hanaa Hakiki, in her intervention “Bringing pushbacks to justice” presented the difficulties that litigators experience in court to materially document pushbacks, which are indeed not meant to be proven. She defined pushbacks as a set of state measures, by which refugees and migrants are forced back over the border – generally shortly after having crossed it – without consideration of their individual circumstances and without any possibility for them to apply for asylum or to put forward arguments against the measures taken.

There are national and international laws that need to be considered in these cases, constituting binding legal obligations for all EU Member States. As a general principle, governments cannot enact disproportionate force, humiliating and degrading treatment or torture, and must facilitate the access to asylum, guarantee protection to people, and provide them access to individualised procedures in this sense.

Member States know that pushbacks have been illegal since a 2012 ECtHR judgment, known as the “Hirsi Jamaa Case,” which found that Italy had violated the law in forcing people back to Libya. However, the effective ban on direct returns led European countries to find other ways to avoid responsibility for those at sea or crossing their borders without documents, and concluded agreements with neighbouring countries, which are requested to prevent migrants from leaving their territories and paid to do so, by any means and without any human rights safeguards in place. By outsourcing rescue to the Libyan authorities, for example, pushbacks by EU countries turned into pullbacks by Libyan coastguard.

Land-pushbacks are still common practice. Hakiki explained that the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) has worked with communities of undocumented migrants since 2014, considering potential legal interventions against the practice of pushbacks at EU borders, and assisting affected persons with individual legal proceedings. She presented three cases the ECCHR litigated in Court (N.D. and N.T. v. Spain; AA vs North Macedonia; SB vs. Croatia) proving that European countries illegally push people back, in violation of human rights laws. Despite the fact that this is still a common practice, it is very difficult to document these violations and have the authorities condemned.

During the beginning of the Syrian conflict, in 2015, refugees were able to travel via Serbia and Hungary into Central and Northern Europe. A couple of years later the EU decided to close down again this so-called Balkan Route, with the result that more and more people found themselves stuck in Bosnia-Herzegovina, prevented from continuing onward to Europe’s territories. From there a person can try to enter the European Union dozens of times, and each time is stopped by Croatian security forces, beaten, and then dragged back across the border to Bosnia-Herzegovina.

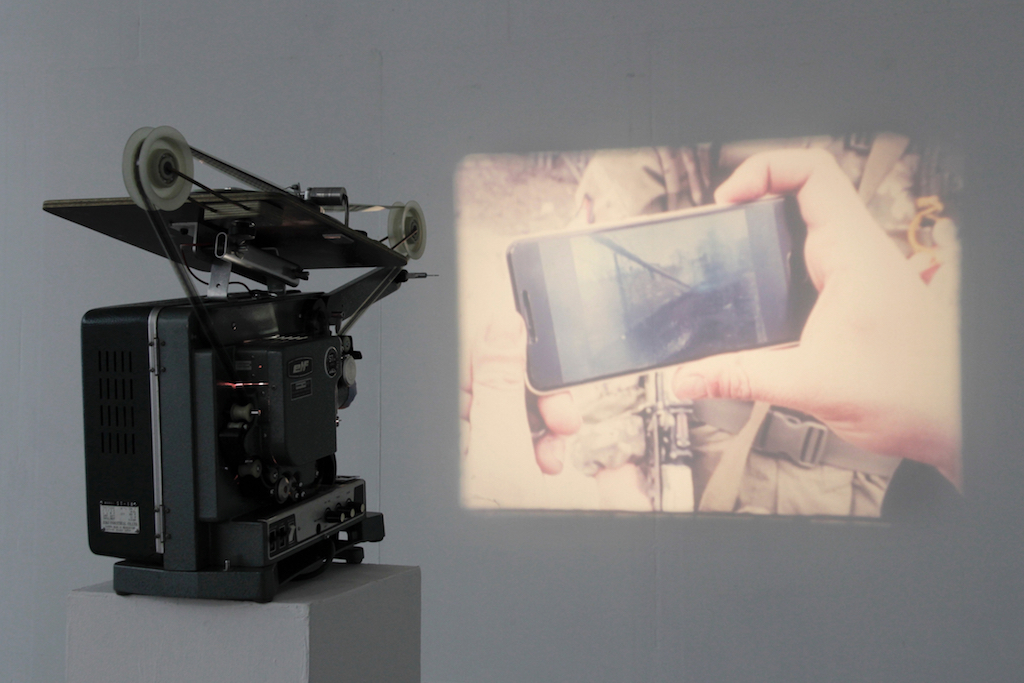

After having seen the effects of these illegal practices and met victims of dozens of violent pushbacks in Sarajevo, in 2019 the reporter Nicole Vögele and her crew succeeded in filming a series of these cross-border expulsions from Croatia to Bosnia Herzegovina near the village of Gradina, in the municipality of Velika Kladuša. The reporter, one of the few who succeeded in documenting this practice, also interviewed those who had just been pushed back by the Interventna Policija officers. The response of the Bosnian authorities to her reportage was a complete denial of all accusations.

Vögele then presented footage taken at the EU external border in Croatia, in March 2020, showing masked men beat up refugees and illegally pushing them back to Bosnia. The journalist and her team found the original video, analysed its metadata, and interviewed the man captured on it. Once again, their work could prove that these practices are not isolated incidents.

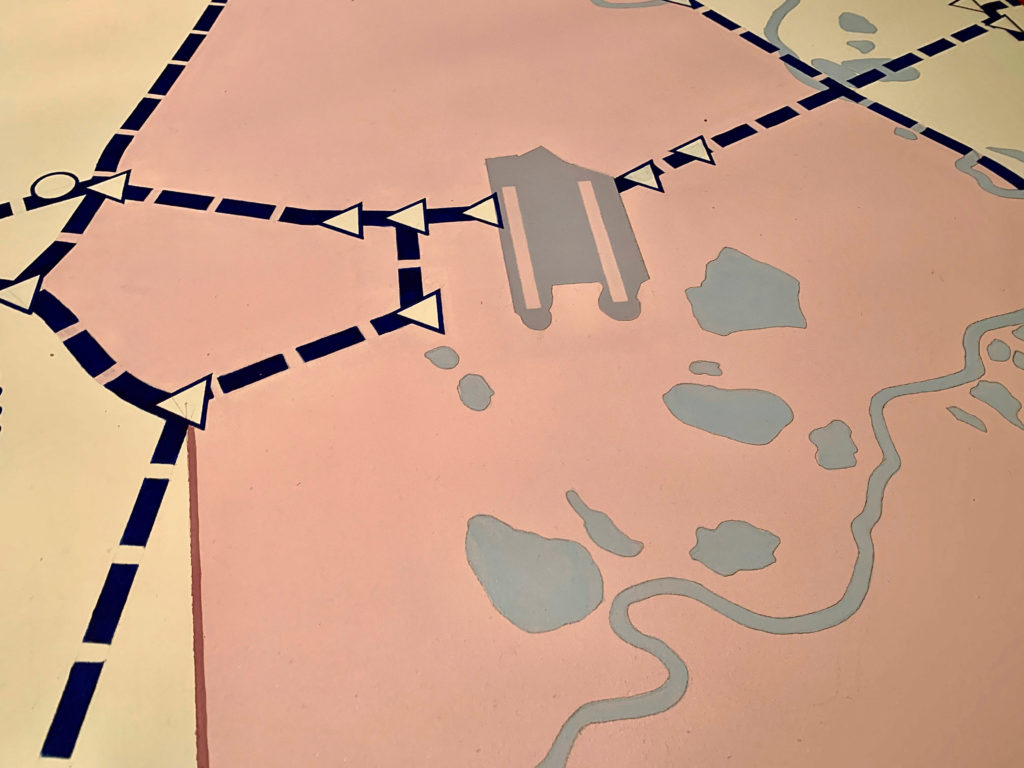

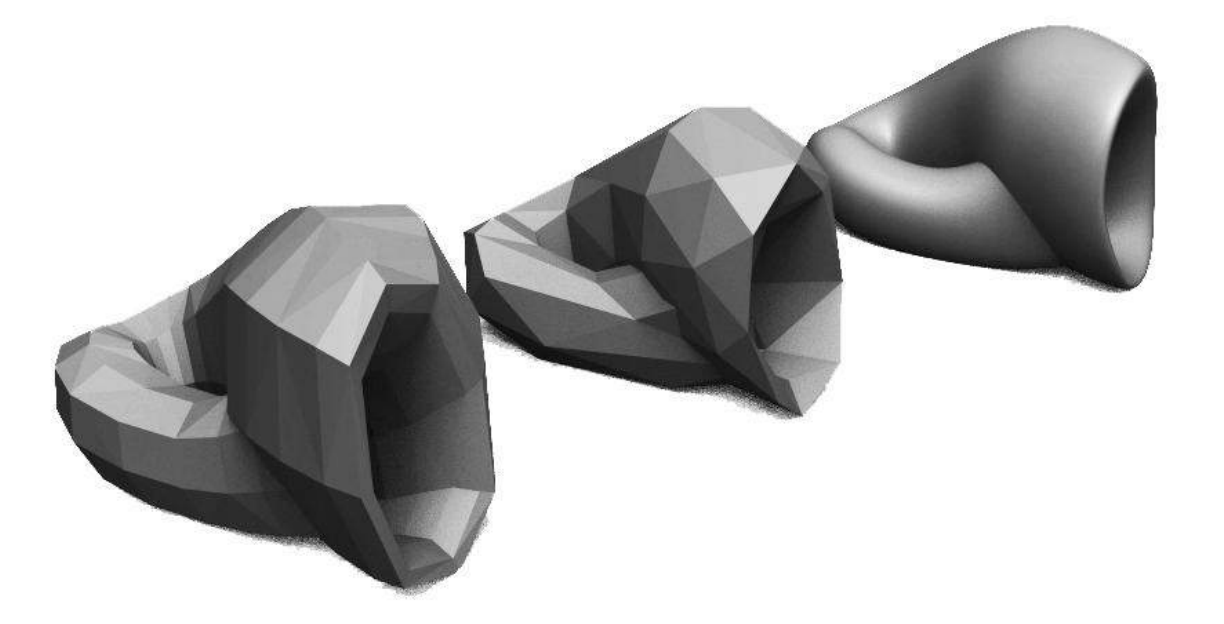

The panel closed with the investigation by Forensic Architecture part of a broader project on cases of pushbacks across the Evros/Meriç river. Team member Dimitra Andritsou presented the organisation founded to investigate human rights violations using a range of techniques, flanking classical investigation methods including open-source investigation video analysis, spatial and architectural practice, and digital modelling.

Forensic Architecture works with and on behalf of communities affected by state and military violence, producing evidence for legal forums, human rights organisations, investigative reporters and media. A multidisciplinary research group – of architects, scholars, artists, software developers, investigative journalists, archaeologists, lawyers, and scientists – based at the University of London, works in partnership with international prosecutors, human rights organisations, political and environmental justice groups, and develops new evidentiary techniques to investigate violations of human rights around the world, armed conflicts, and environmental destruction.

The Evros/Meriç River is the only border between Greece and Turkey that is not sea. For years migrants and refugees trying to cross it to enter Europe have been reporting that unidentified and generally masked men catch, detain, beat, and push people back to Turkey. Mobile phones, documents, and the few personal things they travel with are confiscated or thrown into the river, not to leave any evidence of these violations behind. As Andridsou described, both Greek and EU authorities systematically deny any wrongdoing, refusing to investigate these reports. The river is part of a wider ecosystem of border defence and has been weaponised to deter and let die those who attempt to cross it.

In December 2019, the German magazine Der Spiegel obtained rare videos filmed on a Turkish Border Guard’s mobile phone and on a surveillance, camera installed on the Turkish banks of the river, which apparently documented one of these many pushback operations. Forensic Architecture was commissioned to analyse the footages. A team of experts was then able to geolocate and timestamp the material and could confirm that the images were actually taken few hundred metres away from a Greek military watchtower in Greece.

Andritsou then presented the case of a group of three Turkish political asylum seekers, who entered Greek territory on 4 May 2019, always crossing the Evros/Meriç river. In this case a team of Forensic Architecture could cross-reference different evidence sources, such as new media, remote sensing, material analysis, and witness testimony and verify the group’s entry and their illegal detention in Greece. A pushback to Turkey on the 5 May 2019 led to their arrest and imprisonment by the Turkish authorities.

Ayşe Erdoğan, Kamil Yildirim, and Talip Niksar had been persecuted by the Turkish government on allegations of involvement in Fettulah Gulen’s movement. The group on the run had shared a video appealing for international protection against a possible forced return to Turkey and digitally recorded the journey via WhatsApp. All their text messages with location pins, photographs, videos and metadata prove their presence on Greek soil, prior to their arrest by the Turkish authorities. The investigation could verify that the three were in a Greek police station too, a fact that matches their statement about having repeatedly attempted to apply for asylum there. Their imprisonment is a direct result of the Greek authorities contravening the principle of non-refoulement.

Some keywords resonated throughout the first day of the conference, as a fil rouge connecting the speakers and debates held during the panels and commentaries by the public. Violence, arbitrariness and lawlessness are wilfully ignored –if not backed– by EU Member States, with authorities constantly trying to hide the truth. Thousands of people live under segregation, with no account or trace of being in custody of authorities free to do with them whatever they want.

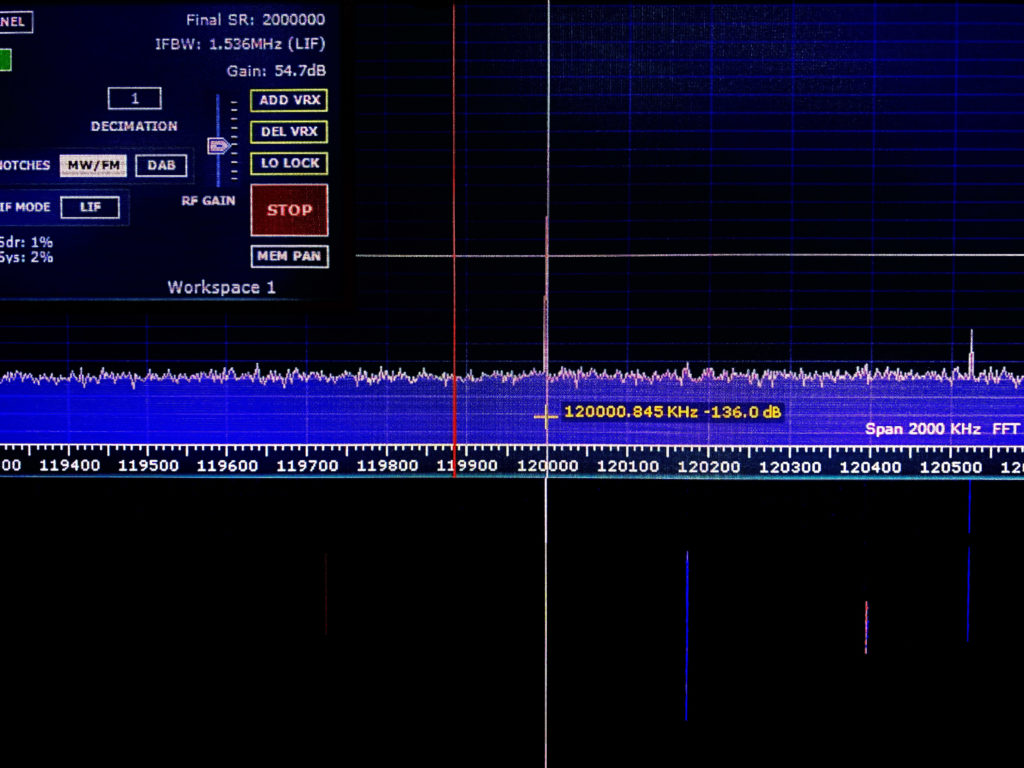

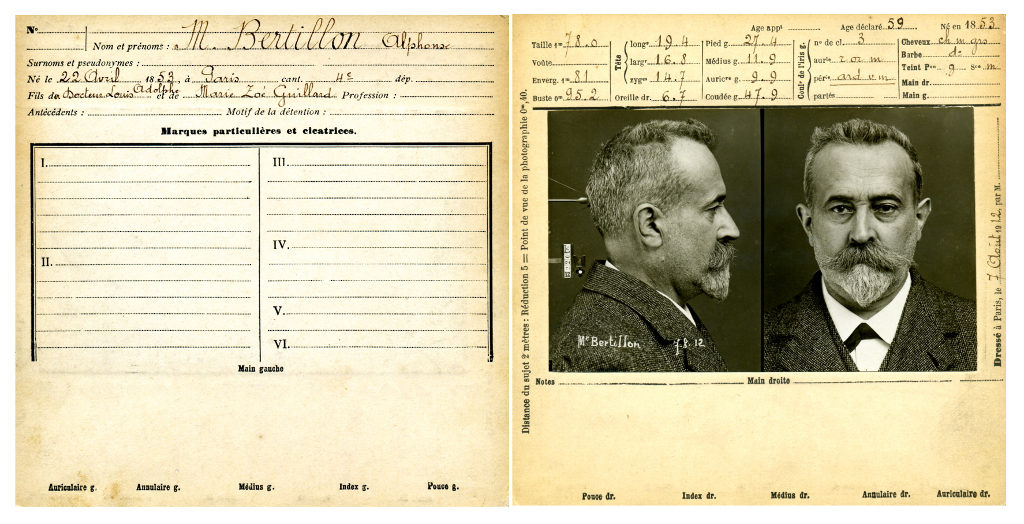

Technology has always been a part of border and immigration enforcement. However, over the last few years, as a response to increased migration into the European Union, governments and international organisations involved in migration management have been deploying new controversial tools, based on artificial intelligence and algorithms, conducting de facto technological experiments and research involving human subjects, refugees and people on the move. The second day of the conference opened with the video contribution by Petra Molnar, lawyer and researcher at the European Digital Rights, author of the recent report “Technological Testing Grounds” (2020) based on over 40 conversations with refugees and people on the move.

When considering AI, questions, answers, and predictions in its technological development reflect the political and socioeconomic point of view, consciously or unconsciously, of its creators. As discussed in the Disruption Network Lab conference “AI traps: automating discrimination” (2019)— risk analyses and predictive policing data are often corrupted by racist prejudice, leading to biased data collection which reinforces privileges of the groups that are politically more guaranteed. As a result, new technologies are merely replicating old divisions and conflicts. By instituting policies like facial recognition, for instance, we replicate deeply ingrained behaviours based on race and gender stereotypes, mediated by algorithms. Bias in AI is a systematic issue when it comes to tech, devices with obscure inner workings and the black box of deep learning algorithms.

There is a long list of harmful tech employed at the EU borders is long, ranging from Big Data predictions about population movements and self-phone tracking, to automated decision-making in immigration applications, AI lie detectors and risk-scoring at European borders, and now bio-surveillance and thermal cameras to contain the spread of the COVID-19. Molnar focused on the risks and the violations stemming from such experimentations on fragile individuals with no legal guarantees and protection. She criticised how no adequate governance mechanisms have been put in place, with no account for the very real impacts on people’s rights and lives. The researcher highlighted the need to recognise how uses of migration management technology perpetuate harms, exacerbate systemic discrimination, and render certain communities as technological testing grounds.

Once again, human bodies are commodified to extract data; thousands of individuals are part of tech-experiments without consideration of the complexity of human rights ramifications, and banalizing their material impact on human lives. This use of technology to manage and control migration is subject to almost no public scrutiny, since experimentations occur in spaces that are militarized and so impossible to access, with weak oversight, often driven by the private sector. Secrecy is often justified by emergency legislation, but the lack of a clear and transparent regulation of the technologies deployed in migration management appears to be deliberate, to allow for the creation of opaque zones of tech-experimentation.

Molnar underlined how such a high level of uncertainty concerning fundamental rights and constitutional guarantees would be unacceptable for EU citizens, who would have ways to oppose these liberticidal measures. However, migrants and refugees have notoriously no access to mechanisms of redress and oversight, particularly during the course of their migration journeys. It could seem secondary, but emergency legislation justifies the disapplication of laws protecting privacy and data too, like the GDPR.

The following part of the conference focused on the journey through Sub-Saharan and Northern Africa, on the difficulties and the risks that migrants face whilst trying to reach Europe. In the conversation “The Journey of Refugees from Africa to Europe,” Yoseph Zemichael Afeworki, Eritrean student based in Luxemburg, talked of his experience with Ambre Schulz, Project Manager at Passerell, and reporter Sally Hayden. Afeworki recalled his dramatic journey and explained what happens to those like him, who cross militarized borders and the desert. The student described that migrants represent a very lucrative business, not just because they pay to cross the desert and the sea, but also because they are used as cheap labour, when not directly captured for ransom.

Once on the Libyan coast, people willing to reach Europe find themselves trapped in a cycle of waiting, attempts to cross the Mediterranean, pullbacks and consequent detention. Libya is a country at war, with two governments. The lack of official records and the instability make it difficult to establish the number of people on the move and refugees detained without trial for an indefinite period. Libyan law punishes illegal migration to and from its territory with prison; this without any account for individual’s potential protection needs. Once imprisoned in a Libyan detention centre for undocumented migrants, even common diseases can lead fast to death. Detainees are employed as forced labour for rich families, tortured, and sexually exploited. Tapes recording inhuman violence are sent to the families of the victims, who are asked to pay a ransom.

As Hayden and Afeworki described, the conditions in the buildings where migrants are held are atrocious. In some, hundreds of people live in darkness, unable to move or eat properly for several months. It is impossible to estimate how many individuals do not survive and die there. An estimated 3,000 people are currently detained there. The only hope for them is their immediate evacuation and the guarantee of humanitarian corridors from Libya –whose authorities are responsible for illegal and arbitrary detention, torture and other crimes– to Europe.

The second day closed with the panel “Politics & Technologies of Fear” moderated by Walid El-Houri, researcher, journalist and filmmaker. Gaia Giuliani from the University of Coimbra, Claudia Aradau, professor of International Politics at King’s College in London, and Joana Varon founder at Coding Rights, Tech and Human Rights Fellow at Harvard Carr Center.

Gaia Giuliani is a scholar, an anti-racist, and a feminist, whose intersectional work articulates the deconstruction of public discourses on the iconographies of whiteness and race, questioning in particular the white narrative imaginary behind security and borders militarization. In her last editorial effort, “Monsters, Catastrophes and the Anthropocene: A Postcolonial Critique” (2020), Giuliani investigated Western visual culture and imaginaries, deconstructing the concept of “risk” and “otherness” within the hegemonic mediascape.

Giuliani began her analyses focusing on the Mediterranean as a border turned into a biopolitical dispositive that defines people’s mobility –and particularly people’s mobility towards Europe– as a risky activity, a definition that draws from the panoply of images of gendered monstrosity that are proper of the European racist imaginary, to reinforce the European and Western “we”. A form of othering, the “we” produces fears through mediatized chronicles of monstrosity and catastrophe.

Giuliani sees the distorted narrative of racialized and gendered bodies on the move to Europe as essential to reinforce the identification of nowadays migrations with the image of a catastrophic horde of monsters, which is coming to depredate the wealthy and peaceful North. It´s a mechanism of “othering” through the use of language and images, which dehumanizes migrants and refugees in a process of mystification and monstrification, to sustain the picture of Europe as an innocent community at siege. Countries of origins are described as the place of barbarians, still now in post-colonial times, and people on the move are portrayed as having the ability to enact chaos in Europe, as if Europe were an imaginary self-reflexive space of whiteness, as it was conceived in colonial time: the bastion of rightfulness and progress.

As Giuliani explained, in this imaginary threat, migrants and refugees are represented as an ultimate threat of monsters and apocalypse, meant to undermine the identity of a whole continent. Millions of lives from the South become an indistinct mass of people. Figures of race that have been sedimented across centuries, stemming from colonial cultural archives, motivate the need to preserve a position of superiority and defend political, social, economic, and cultural privileges of the white bodies, whilst inflicting ferocity on all others.

This mediatized narrative of monsters and apocalypse generates white anxiety, because that mass of racialized people is reclaiming the right to escape, to search for a better life and make autonomous choices to flee the objective causes of unhappiness, suffering, and despair; because that mass of individuals strives to become part of the “we”. All mainstream media consider illegitimate their right to escape and the free initiative people take to cross borders, not just material ones but also the semiotic border that segregate them in the dimension of “the barbarians.” An unacceptable unchained and autonomous initiative that erases the barrier between the colonial then and the postcolonial now, unveiling the coloniality of our present, which represents migration flows as a crisis, although the only crisis undergoing is that of Europe.

On the other side, this same narrative often reduces people on the move and refugees to vulnerable, fragile individuals living in misery, preparing the terrain for their further exploitation as labour force, and to reproduce once again racialized power relations. Here the process of “othering” revivals the colonial picture of the poor dead child, functional to engender an idea of pity, which has nothing to do with the individual dignity. Either you exist as a poor individual in the misery –which the white society mercifully rescues– or as a part of the mass of criminals and rapists. However, these distinct visual representations belong to the same distorted narration, as epitomized in the cartoons published by Charlie Hebdo after the sexual assaults against women in Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015.

Borders have been rendered as testing ground right for high-risk experimental technologies, while refugees themselves have become testing subjects for these experiments. Governments and non-state actors are developing and deploying emerging digital technologies in ways that are uniquely experimental, dangerous and discriminatory in the border and immigration enforcement context. Taking step from the history of scientific experiments on racialized and gendered bodies, Claudia Aradau invited the audience to reconsider the metaphorical language of experiments that orients us to picture high-tech and high-risk technological developments. She includes instead also tech in terms of obsolete tools deployed to penalise individuals and recreate the asymmetries of the digital divide mirroring the injustice of the neoliberal system.

Aradau studies technologies and the power asymmetries in their deployment and development. She explained that borders have been used as very profitable laboratories for the surveillance industry and for techniques that would then be deployed widely in the Global North. From borders and prison systems –in which they initially appeared– these technologies are indeed becoming common in urban spaces modelled around the traps of the surveillance capitalism. The fact that they slowly enter our vocabularies and daily lives makes it difficult to define the impact they have. When we consider for example that inmates’ and migrants’ DNA is collected by a government, we soon realise that we are entering a more complex level of surveillance around our bodies, showing tangibly how privacy is a collective matter, as a DNA sequence can be used to track a multitude of individuals from the same genealogic group.

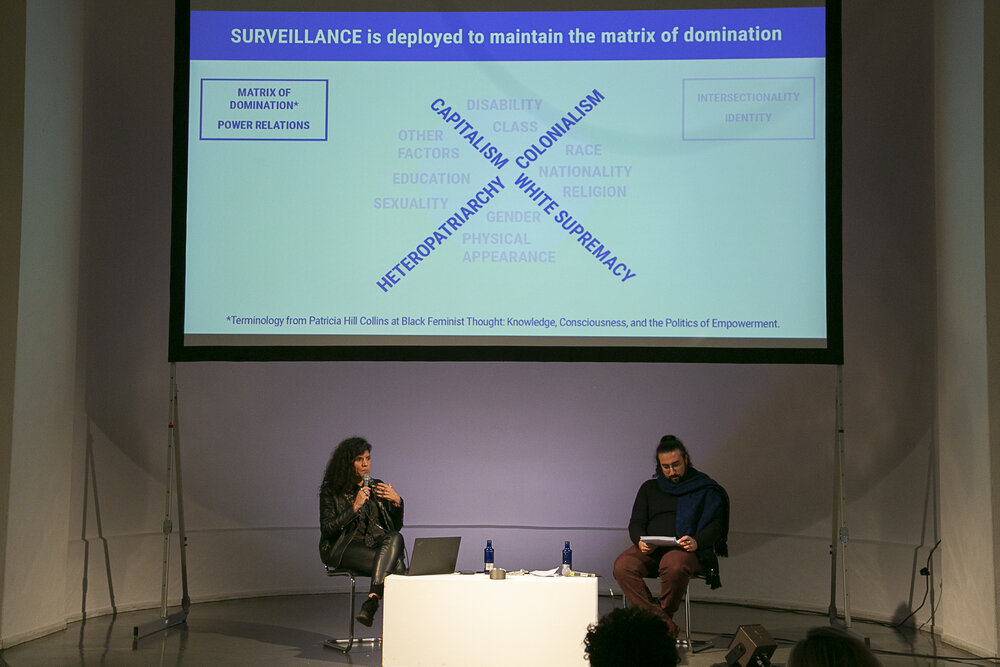

Whilst we see hyper-advanced tech on one side, on the other people on the move walk with nothing to cross a border, sometimes not even shoes, with their personal belongings inside plastic bags, and just a smartphone to orientate themselves, and communicate and ask for help. An asymmetry, which is –once again– being deployed to maintain what Aradau defined as matrix of domination: no surveillance on CO2 emissions and environmental issues due to industrial activities, no surveillance on exploitations of resources and human lives; no surveillance on the production of weapons, but massive deployment of hi-tech to target people on the move, crossing borders to reach and enter a fortress, which is not meant for them.

Aradau recalled that in theory, protocols ethics and demands for objectivity are necessary when it comes to scientific experiments. However, the introduction in official procedures of digital tech devices and software such as Skype, WhatsApp or MasterCard or a set of apps developed by either non-state or state actors, required neither laboratories nor the randomized custom trials that we usually associate with scientific experimentation. These heterogeneous techniques specifically intended to work everywhere and enforced without protocols, need to be understood under neoliberalism: they rely on pilot projects trials and cycles of funds and donors, whose goal is every time to move to a next step, to finance more experiments. Human-rights-centred tech is far away.

Thus, we see always more experiments carried out without protocols, from floating walls tech to stop migrants reaching the Greek shores, to debit cards used as surveillance devices. Creative experiments come also with the so-called refugees’ integration, conceived by small-scale injections of devices into their reality for limited periods, with the purpose of speculatively recompose rotten asymmetries of power and injustice. In Greece, as Aradau mentioned, the introduction of Skype in the process of the asylum application became an obstacle, with applicants continually experiencing debilitation through obsolete technology that doesn’t work or devices with limited access, disorientation through contradictory and outdated information.

There is also a factual aspect: old and slow computers, documents that have not been updated or have been updated at different times, and lack of personnel are justified by saying that resources are limited. A complete lack or shortage of funds, which is one other typical condition of neoliberalism, as we can see in Greece. In this, tech recomposes relations of precarity in a different guise.

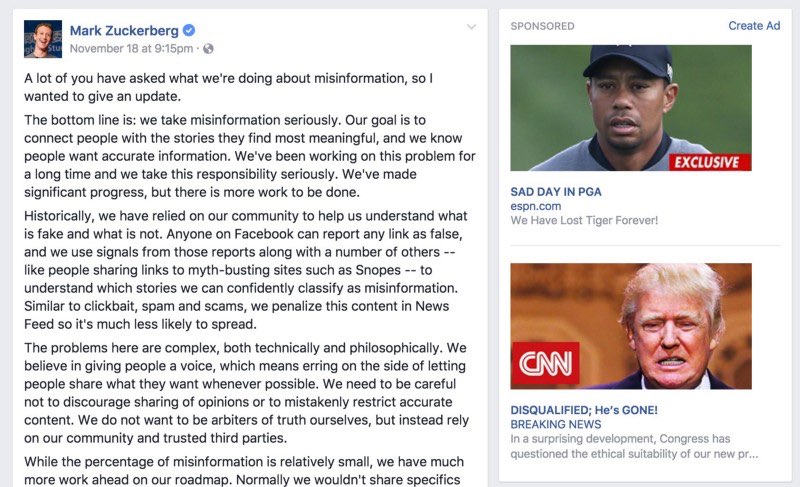

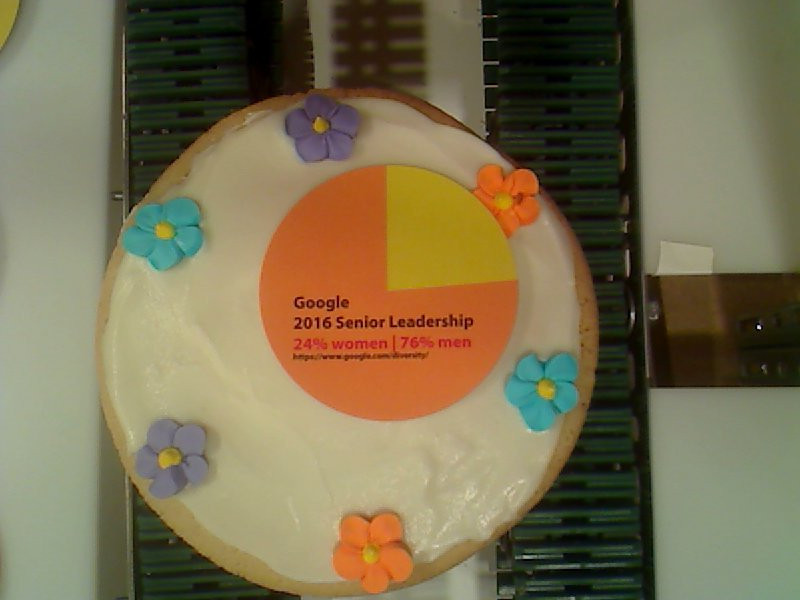

Aradau concluded her contribution focusing on the technologies that are deployed by NGOs, completely or partially produced elsewhere, often by corporate actors who remain entangled in the experiments through their expertise and ownership. Digital platforms such as Facebook, Microsoft, Amazon, or Google not only shape relations between online users, she warned, but concerning people on the move and refugees too. Google and Facebook –for example– dominate the relations that underpin the production of refugee apps by humanitarian actors.

Google is at the centre of a sort of digital humanitarian ecosystem, not only because it can host searches or provide maps for the apps, but also because it simultaneously intercepts data flows so that it acts as a surplus data extractor. In addition, social networks reshape digital humanitarianism through data extractive relations and provide big part of the infrastructure for digital humanitarianism. Online humanitarianism becomes thus a particularly vulnerable site of data gathering and characterised by an overall lack of resources –similarly to the Greek state. As a result, humanitarian actors cannot tackle the depreciation messiness and obsolescence of their tech and apps.

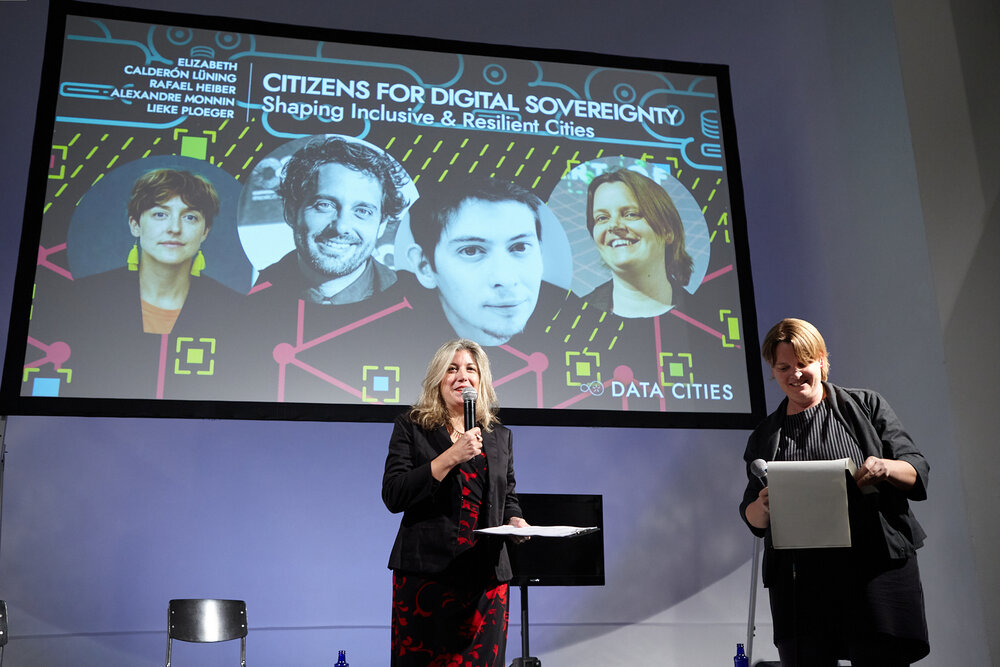

The last day of the conference concentrated on the urgent need to creating safe passages for migration, and pictured the efforts of those who try to ensure safer migration options and rescue migrants in distress during their journey. Lieke Ploeger, community director of the Disruption Network Lab, presented the panel discussion “Creating Safe Passages”, moderated by Michael Ruf, writer and director of documentary and theatre plays. Ruf´s productions include the “Asylum Dialogues” (2011) and the “Mediterranean Migration Monologues” (2019), which have been performed in numerous countries more than 800 times by a network of several hundred actors and musicians. This final session brought together speakers from the Migrant Media Network (MMN), the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS), and SeaWatch e.V. to discuss their efforts to ensure safer migration options, as well as share reliable information and create awareness around migration issues.

The talk was opened by Thomas Kalunge, Project Director of the Migrant Media Network, one of r0g_agency’s projects, together with #defyhatenow. Since 2017 the organisation has been working on information campaigns addressed to people in rural areas of Africa, to explain that there are possible alternatives for safer and informed decisions, when they choose to reach other countries, and what they may come across if they decide to migrate.

The MMN team organises roundtable discussions and talks on various topics affecting the communities they meet. They build a space in which young people take time to understand what migration is nowadays and to listen to those, who already personally experienced the worst and often less discussed consequences of the journey. To approach possible migrants the MMN worked on an information campaign on the ethical use of social media, which also helps people to learn how to evaluate and consume information shared online and recognise reliable sources.

The MMN works for open culture and critical social transformation, and provides young Africans with reliable information and training on migration issues, included digital rights. The organisation also promotes youth entrepreneurship “at home” as a way to build economic and social resilience, encouraging youth to create their own opportunities and work within their communities of origin. They engage on conversations on the dangers of irregular migration, discussing together rumours and lies, so that individuals can make informed choices. One very relevant thing people tend to underestimate, is that sometimes misinformation is spread directly by human smugglers, warned Kalunge.

The MMN also provides people from remote regions with offline tools that are available without an internet connection, and training advisors and facilitators who are then connected in a network. The HyracBox for example is a mobile, portable, RaspberryPi powered offline mini-server for these facilitators to use in remote or offline environments, where access to both power and Internet is challenging. With it, multiple users can access key MMN info materials.

An important aspect to mention is that the MMN does not try to tell people not to migrate. European government have outsourced borders and migration management, supporting measures to limit people mobility in North and Sub-Saharan Africa, and it is important to let people know that there are real dangers, visible and invisible barriers they will meet on their way.

Visa application processes –even for legitimate reasons of travel– are very strict for some countries, often without any information being shared, even with people who are legitimately moving for education, to work or get medical treatment. The ruling class that makes up the administrative bureaucracy and outlines its structures, knows that who controls time has power. Who can steal time from others, who can oblige others to waste time on legal quibbles and protocol matters, can suffocate the others’ existence in a mountain of paperwork.

Human smugglers then become the final resort. Kaluge explained also that, at the moment, the increased outsourcing of the European border security services to the Sahel and other northern Africa countries is leading to diversion of routes, increased dangerousness of the road, people trafficking, and human rights violations.

Closing the conference, Regina Catrambone presented the work that MOAS does around the world and the campaign for safe and legal routes that is urging governments and international organisations to implement regular pathways of migration that already exist. Mattea Weihe presented instead the work of SeaWatch e. V., an organisation which is also advocating for civil sea rescue, legal escape routes and a safe passage, and which is at sea to rescue migrants in distress.

The two panellists described the situation in the Central Mediterranean. Since the beginning of the year, over 500 migrants have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea (November 2020). While European countries continue to delegate their migration policy to the Libyan Coast Guard, rescue vessels from several civilian organisations have been blocked for weeks, witnessing the continuous massacre taking place just a few miles from European shores. With no common European rescue intervention at sea, the presence of NGO vessels is essential to save humans and rescue hundreds of people who undertake this dangerous journey to flee from war and poverty.

However, several EU governments and conservative and far right political parties criminalise search and rescues activities, stating that helping migrants at sea equals encouraging illegal immigration. A distorted representation legitimised, fuelled and weaponised in politics and across European society that has led to a terrible humanitarian crisis on Europe’s shores. Thus, organisations dedicated to rescuing vessels used by people on the move in the Mediterranean Sea see all safe havens systematically shut off to them. Despite having hundreds of rescued individuals on board, rescue ships wait days and weeks to be assigned a harbour. Uncertainty and fear of being taken back to Libya torment many of the people on board even after having been rescued. After they enter the port, the vessels are confiscated and cannot get back out to sea.

By doing so, Europe and EU Member States violate human rights, maritime laws, and their national democratic constitutions. The panel opened again the crucial question of humanitarian corridors, human-rights-based policy, and relocations. In the last years the transfer of border controls to foreign countries, has become the main instrument through which the EU seeks to stop migratory flows to Europe. This externalisation deploys modern tech, money and training of police authorities in third countries moving the EU-border far beyond the Union’ shores. This despite the abuses, suffering and human-rights violations; willingly ignoring that the majority of the 35 countries that the EU prioritises for border externalisation efforts are authoritarian, known for human rights abuses and with poor human development indicators (Expanding Fortress, 2018).

It cannot be the task of private organizations and volunteers to make up for the delay of the state. But without them no one would do it.

States are seeking to leave people on the move, refugees, and undocumented migrants beyond the duties and responsibilities enshrined in law. Most of the violations, and the harmful technological experimentation described throughout the conference targeting migrants and refugees, occurs outside of their sovereign responsibility. Considering that much of technological development occurs in fact in the so-called “black boxes,” by acting so these state-actors exclude the public from fully understanding how the technology operates.

The fact that the people on the move on the Greek islands, on the Balkan Route, in Libya, and those rescued in the Mediterranean have been sorely tested by their journeys, living conditions, and, in many cases, imprisoned, seems to be irrelevant. The EU deploys politics that make people who have already suffered violence, abuse, and incredibly long journeys in search of a better life, wait a long time for a safe port, for a visa, for a medical treatment.

All participants who joined the conference expressed the urgent need for action: Europe cannot continue to turn its gaze away from a humanitarian emergency that never ends and that needs formalised rescue operations at sea, open corridors, and designated authorities enacting an approach based on defending human rights. Sea rescue organisations and civil society collectives work to save lives, raise awareness and demand a new human rights-based migration and refugee policy; they shall not be impeded but supported.

The conference “Borders of Fear” presented experts, investigative journalists, scholars, and activists, who met to discuss wrongdoings in the context of migration and share effective strategies and community-based approaches to increase awareness on the issues related to the human-rights violations by governments. Here bottom-up approaches and methods that include local communities in the development of solutions appear to be fundamental. Projects that capacitate migrants, collectives, and groups marginalized by asymmetries of power to share knowledge, develop and exploit tools to combat systematic inequalities, injustices, and exploitation are to be enhanced. It is imperative to defeat the distorted narrative, which criminalises people on the move, international solidarity and sea rescue operations.

Racism, bigotry and panic are reflected in media coverage of undocumented migrants and refugees all over the world, and play an important role in the success of contemporary far-right parties in a number of countries. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance effective and alternative counter-narratives based on facts. For example, the “Africa Migration Report” (2020) shows that 94 per cent of African migration takes a regular form and that just 6 per cent of Africans on the move opt for unsafe and dangerous journeys. These people, like those from other troubled regions, leave their homes in search of a safer, better life in a different country, flee from armed conflicts and poverty. It is their right to do so. Instead of criminalising migration, it is necessary to search for the real causes of this suffering, war and social injustice, and wipe out the systems of power behind them.

Videos of the conference are also available on YouTube via:

For details of speakers and topics, please visit the event page here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/borders-of-fear

Upcoming programme:

The 23rd conference of the Disruption Network Lab curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli is titled “Behind the Mask: Whistleblowing During the Pandemic.“ It will take place on March 18-20, 2021. More info: https://www.disruptionlab.org/behind-the-mask

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for the newsletter and get informed about its conferences, meetups, ongoing researches and projects.

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

On September 25, 2020, the Disruption Network Lab opened its 20th conference “Data Cities: Smart Technologies, Tracking & Human Rights” curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, founder and program director of the organisation, and Mauro Mondello, investigative journalist and filmmaker. The two-day-event was a journey inside smart-city visions of the future, reflecting on technologies that significantly impact billions of citizens’ lives and enshrine new unprecedented concentrations of power, characterising the era of surveillance capitalism. A digital future which is already here.

Smart urbanism relies on algorithms, data mining, analytics, machine learning and infrastructures, providing scientists and engineers with the capability of extracting value from the city and its people, whose lives and bodies are commodified. The adjective ‘smart’ represents a marketing gimmick used to boost brands and commercial products. When employed to designate metropolitan areas, it describes cities which are liveable, sustainable and efficient thanks to technology and the Internet.

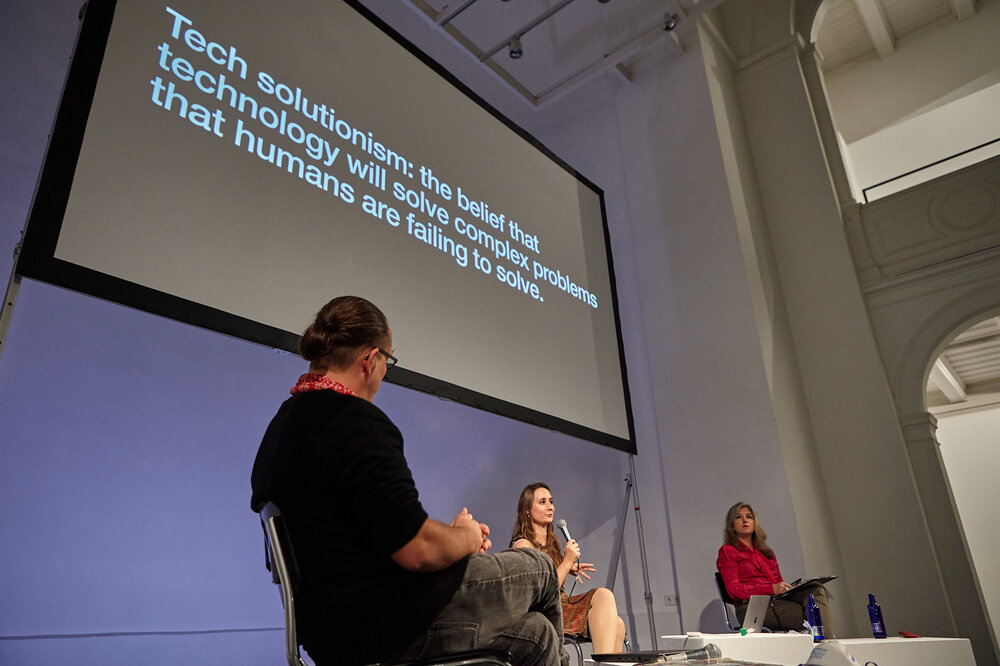

The conference was held at Berlin’s Kunstquartier Bethanien and brought together researchers, activists and artists to discuss what kind of technologies are transforming metropolises and how. The Disruption Network Lab aimed at stimulating a concrete debate, devoid of the rhetoric of solutionism, in which participants could focus on the socio-political implications of algorithmic sovereignty and the negative consequences on fundamental rights of tracking, surveillance and AI. They shared the results of their latest work and proposed a critical approach, based on the motivation of transforming mere opposition into a concrete path for inspirational change.

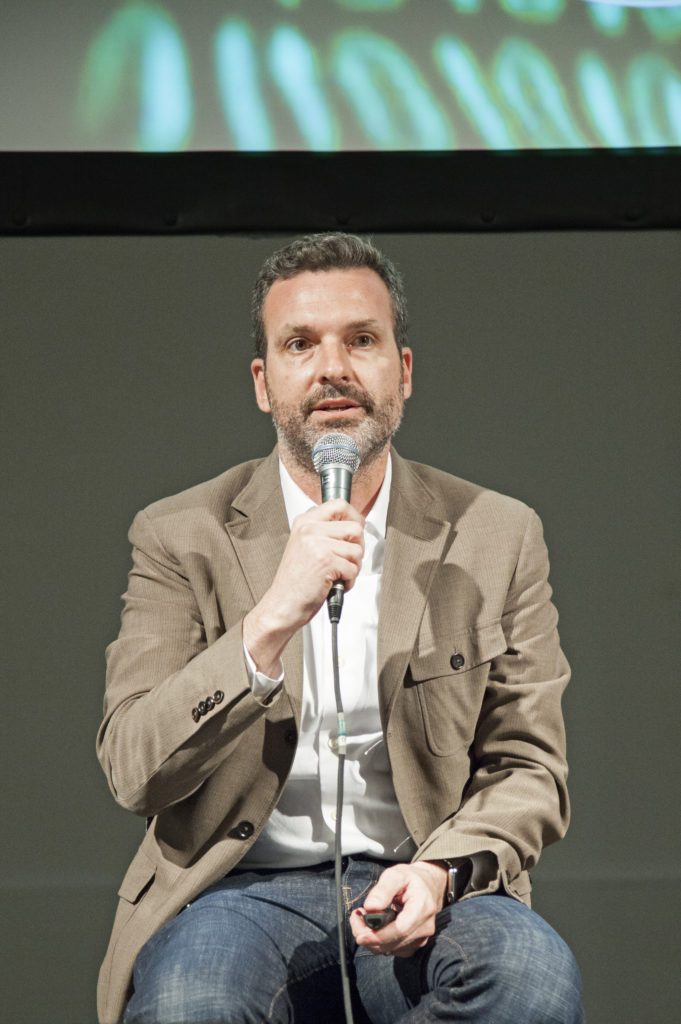

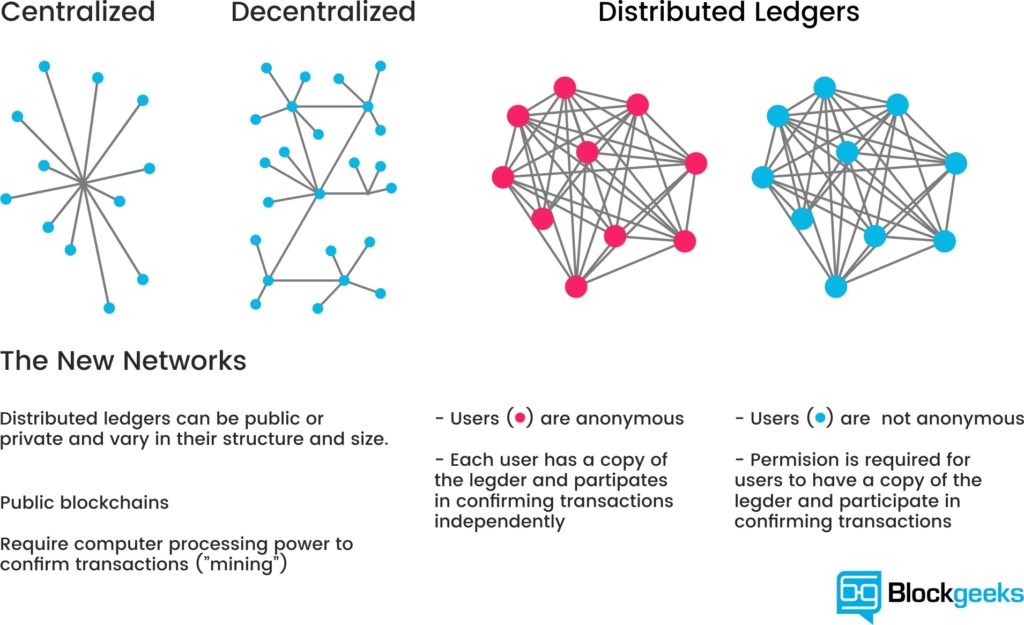

The first part of the opening keynote “Reclaiming Data Cities: Fighting for the Future We Really Want” was delivered by Denis “Jaromil” Roio, ethical hacker, artist and activist. In his talk, moderated by Daniel Irrgang, research fellow at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society, Jaromil focused on algorithmic sovereignty and the incapacity to govern technological transformation which characterises our societies today.

Jaromil looked at increasing investments in AI, robots and machine learning, acknowledging that automated decision-making informed by algorithms has become a dominant reality extending to almost all aspects of life. From the code running on thousands of e-devices to the titanic ICTs-infrastructures connecting us, when we think about the technology surrounding us, we realise that we have no proper control over it. Even at home, we cannot fully know what the algorithms animating our own devices are adopted for, if they make us understand the world better or if they are instead designed to allow machines to study and extract data from us for the benefit of their creators. The same critical issues and doubts emerge with a large-scale implementation of tech within so-called “smart cities”, maximization of the “Internet of Things” born in the 1980s.

Personal data is a lucrative commodity and big data means profit, power, and insights, which is essential to all government agencies and tech firms. Jaromil announced a call-to-action for hackers and programmers, to get involved without compromise and play a key role in building urban projects which will safeguard the rights of those living in them, taking into consideration that by 2050, an estimated 70 per cent of the world’s population may well live in cities.

Jaromil observed that there is too often a tremendous difference between what we see when we look at a machine and what really happens inside it. Since the dawn of the first hacking communities, hackers preferred writing their own software and constructing their own machines. They were free to disassemble and reassemble them, having control over all the functions and direct access to the source code. This was also a way to be independent from the corporate world and authorities, which they mistrusted.

Today, users are mostly unaware of the potential of their own tech-devices, which are no longer oriented strictly towards serving them. They have no exposure to programming and think Computer Science and Informatics are way too difficult to learn, and so entrust themselves entirely to governments and tech firms. Jaromil works to simplify interface and programming language, so people can learn how to program and regain control over their tech. He supports minimalism in software design and a process of democratisation of programming languages which works against technocratic monopolies. His Think & Do Tank—Dyne.org—is a non-profit software house with expertise in social and technical innovation, gathering developers from all over the world. It integrates art, science and technology in brilliant community-oriented projects (D-CENT, DECODE, Commonfare, Devuan), promoting decentralisation and digital sovereignty to encourage empowerment for the people.

The second keynote speaker, Julia Koiber, managing director at SuperrrLab, addressed issues of technology for the common good, open data and transparency, and—like the previous speaker—reflected on uncontrolled technological transformation. Koiber noticed that the more people are mobilising to be decision-makers, rather than passive data providers, the more they see how difficult it is to ensure that publicly relevant data remains subject to transparent control and public ownership. In the EU several voices are pushing for solutions, including anonymised user data to be classified as ‘common good’ and therefore free from the control of tech companies.

Recalling the recent Canadian experience of Sidewalk Labs (Alphabet Inc.’s company for urban tech development), Koiber explained that in order to re-imagine the future of neighbourhoods and cities, it is necessary to involve local communities. The Google’s company had proposed rebuilding an area in east Toronto, turning it into its first smart city: an eco-friendly digitised and technological urban planning project, constantly collecting data to achieve perfect city living, and a prototype for Google’ similar developments worldwide. In pushing back against the plan and its vertical approach, the municipality of Toronto made clear that it was not ready to consider the project unless it was developed firmly under public control. The smart city development which never really started died out with the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. Its detractors argue that city dwellers were meant to be human sensors collecting data to test new tech-solutions and increase corporate profit. Data collected during the provision of public services and administrative data should be public; it belongs to the people, not to a black box company.

As Jaromil and Koiber discussed, in the main capitals of the world the debate on algorithmic sovereignty is open and initiatives such as the “Manifesto in favour of technological sovereignty and digital rights for cities,” written in Barcelona, reflect the belief that it will be crucial for cities to achieve full control and autonomy of their ICTs, which includes service infrastructures, websites, applications and data owned by the cities themselves and regulated by laws protecting the interests and fundamental rights of their citizens. Their implementation shall come within people-centric projects and a transparent participatory process.

The work of the conference continued with the panel “Making Cities Smart for Us: Subverting Tracking & Surveillance,” a cross-section of projects by activists, researchers and artists digging into the false myth of safe and neutral technologies, proposing both counterstrategies and solutions to tackle issues introduced in the opening keynote.

Eva Blum-Dumontet, English researcher on privacy and social-economic rights, dedicated her work to the impact of tech on people, particularly those in vulnerable situations. She opened the talk with the observation that the term ‘smart city’ lacks of an official definition; it was coined by IBM’s marketing team in 2005 without a scientific basis. Since then, tech firms from all over the world have been developing projects to get into governments’ favour and to build urban areas that integrate boundless tech-solutions: security and surveillance, energy and mobility, construction and housing, water supply systems and so on.

As of today, thanks to smart cities, companies such as IBM, Cisco, Huawei, Microsoft and Siemens have found a way to generate the satisfaction of both governments and their suppliers, but do not seem to act in the public’s best interest. In their vision of smart urbanism people are only resources: like water, buildings and administrative services, they are something to extract value from.

Blum-Dumontet explained that when we refer to urban tech-development, we need to remember that cities are political spaces and that technology is not objective. Cities are a concentration of countless socio-economic obstacles that prevent many individuals from living a dignified life. Privilege, bias, racism and sexism are already integrated in our cities´ (tech-)infrastructures. The researcher acknowledged that it is very important to implement people-centric solutions, while keeping in mind that as of now our cities are neither inclusive nor built for all, with typical exclusion of, for instance, differently abled individuals, low-income residents and genderqueer people.

A sharp critique of the socio-economic systems causing injustice, exploitation and criminalisation, also lies at the core River Honer’s work. River is a web developer at Expedition Grundeinkommen and anti-capitalist tech activist, who wants to support citizens and activists in their struggle for radical transformation toward more just cities and societies without relying on solutions provided by governments and corporations.

Her work methodology includes critical mapping and geospatial analyses, in order to visualise and find solutions to structurally unjust distribution of services, access and opportunities in given geographic areas. Honer works with multidisciplinary teams on community-based data gathering, and turns information into geo-visualisation to address social issues and disrupt systems of discriminatory practices which target minorities and individuals. Examples of her work include LightPath, an app providing the safest well-lit walking route between two locations through various cities; Refuge Restroom, which displays safe restroom access for transgender, intersex, and gender nonconforming individuals who suffer violence and criminalisation in the city, and the recent COVID-19 tenant protection map.

Honer’s projects are developed to find practical solutions to systematic problems which underpin a ruthless political-economic structure. She works on tech that ignores or undermines the interests of capitalism and facilitates organisation for the public ownership of housing, utilities, transport, and means of production.

The Disruption Network Lab dedicated a workshop to her Avoid Control Project, a subversive tracking and alert system that Honer developed to collect the location of ticket controllers for the Berlin public transportation company BVG, whose methods are widely considered aggressive and discriminatory.

There are many cities in the world in which activist groups, non-governmental organisations and political parties advocate for a complete revocation of fares on public transport systems. The topic has been debated for many years in Berlin too; the BVG is a public for-profit company earning millions of euros annually on advertising alone, and in addition charges expensive flat fares for all travelers.

The panel discussion was concluded with Norway-based speakers Linda Kronman and Andreas Zingerle of the KairUs collective. The two artists explored topics such as vulnerabilities in Internet-of-Things-devices and corporatisation of city governance in smart cities, as well as giving life to citizen-sensitive-projects in which technology is used to reclaim control of our living environments. As Bazzichelli explained when presenting the project “Suspicious Behaviours” by Kronman, KairUs’s production constitutes an example of digital art eroding the assumptions of objective or neutral Artificial Intelligence, and shows that hidden biases and hidden human decisions influence the detection of suspicious behaviour within systems of surveillance, which determines the social impacts of technology.

The KairUs collective also presented a few of its other projects: “The Internet of Other People’s things” addresses technological transformation of cities and tries to develop new critical perspectives on technology and its impact on peoples’ lifestyles. Their video-installation “Panopticities” and the artistic project “Insecure by Design” (2018) visualise the harmful nature of surveillance capitalism from the unusual perspective of odd vulnerabilities which put controlled and controllers at risk, such as models of CCTV and IP cameras with default login credentials and insecure security systems which are easy to hack or have by default no password-protection at all.

Focusing on the reality of smart cities projects, the collective worked on “Summer Research Lab: U City Sogdo IDB”(2017), which looked at Asian smart urbanism and reminding the panellists that many cities like Singapore, Jakarta, Bangkok, Hanoi, Kuala Lump already heavily rely on tech. In Songdo City, South Korea, the Songdo International Business District (Songdo IBD), is a new “ubiquitous city” built from scratch, where AI can monitor the entire population’s needs and movements. At any moment, through chip-implant bracelets, it is possible to spot where someone is located, or observe people undetected using cameras covering the whole city. Sensors constantly gather information and all services are automatised. There are no discernible waste bins in the park or on street corners; everything seems under tech-control and in order. As the artists explained, this 10-year development project is estimated to cost in excess of 40 billion USD, making it one of the most expensive development projects ever undertaken.

The task of speculative architecture is to create narratives about how new technologies and networks influence and shape spaces and cultures, foreseeing possible futures and imagining how and where new forms of human activity could exist within cities changed by these new processes. Liam Young, film director, designer and speculative architect opened the keynote on the second conference day with his film “Worlds Less Travelled: Mega-Cities, AI & Critical Sci-Fi“. Through small glimpses, fragments and snapshots taken from a series of his films, he portrayed an alternative future of technology and automation in which everything is controlled by tech, where complexities and subcultures are flattened as a result of technology, and people have been relegated to the status of mere customers instead of citizens

Young employs the techniques of popular media, animation, games and doc-making to explore the architectural, urban and cultural implications of new technologies. His work is a means of visualising imaginary future worlds in order to help understand the one we are in now. Critical science fiction provides a counter-narrative to the ordinary way we have of representing time and society. Young speaks of aesthetics, individuals and relationships based on objects that listen and talk back, but which mostly communicate with other machines. He shows us alternative futures of urban architecture, where algorithms define the extant future, and where human scale is no longer the parameter used to measure space and relations.

Young’s production also focused on the Post-Anthropocene, an era in which technology and artificial intelligence order, shape and animate the world, marking the end of human-centered design and the appearance of new typologies of post-human architectures. Ours is a future of data centres, ITCs networks, buildings and infrastructures which are not for people; architectural spaces entirely empty of human lives, with fields managed by industrialised agriculture techniques and self-driving vehicles. Humans are few and isolated, living surrounded by an expanse of server stacks, mobile shelving systems, robotic cranes and vacuum cleaners. The Anthropocene, in which humans are the dominant force shaping the planet, is over.

The keynote, moderated by the journalist Lucia Conti, editor at “Il Mitte”and communication expert at UNIDO, moved from the corporate dystopia of Young, in which tech companies own cities and social network interactions are the only way people interrelate with reality, to the work of filmmaker Tonje Hessen Schei, director of the documentary film “iHuman”(2020). The documentary touches on how things are evolving from biometric surveillance to diversity in data, providing a closer look at how AI and algorithms are employed to influence elections, to structure online opinion manipulation, and to build systems of social control. In doing so, Hessen Schei depicts an unprecedented concentration of power in the hands of few individuals.

The movie also presents the latest developments in Artificial Intelligence and Artificial General Intelligence, the hypothetical intelligence of machines that can understand or learn any task that a human being can.

When considering AI, questions, answers and predictions in its technological development will always reflect the political and socioeconomic point of view, consciously or unconsciously, of its creators. For instance —as described in the Disruption Network Lab´s conference “AI Traps” (2019)—credit scores are historically correlated with racist segregated neighbourhoods. Risk analyses and predictive policing data are also corrupted by racist prejudice leading to biased data collection which reinforces privilege. As a result new technologies are merely replicating old divisions and conflicts. By instituting policies like facial recognition, for instance, we replicate deeply ingrained behaviours based on race and gender stereotypes and mediated by algorithms.

Automated systems are mostly trying to predict and identify a risk, which is defined according to cultural parameters reflecting the historical, social and political milieu, in order to give answers and make decisions which fit a certain point of view. What we are and where we are as a collective —as well as what we have achieved and what we still lack culturally— gets coded directly into software, and determines how those same decisions will be made in the future. Critical problems become obvious in case of neural networks and supervised learning.

Simply put, these are machines which know how to learn and networks which are trained to reproduce a given task by processing examples, making errors and forming probability-weighted associations. The machine learns from its mistakes and adjusts its weighted associations according to a learning rule and using error values. Repeated adjustments eventually allow the neural network to reproduce an output increasingly similar to the original task, until it reaches a precise reproduction. The fact is that algorithmic operations are often unpredictable and difficult to discern, with results that sometimes surprise even their creators. iHuman shows that this new kind of AI can be used to develop dangerous, uncontrollable autonomous weapons that ruthlessly accomplish their tasks with surgical efficiency.

Conti moderated the dialogue between Hessen Schei, Young, and Anna Ramskogler-Witt, artistic director of the Human Rights Film Festival Berlin, digging deeper into aspects such as censorship, social control and surveillance. The panellists reflected on the fact that—far from being an objective construct and the result of logic and math—algorithms are the product of their developers’ socio-economic backgrounds and individual beliefs; they decide what type of data the algorithm will process and to what purpose.