On the day of the General Data Protection Law (GDPR) going into effect in Europe, on the 25th of May, the Disruption Network Lab opened its 13th conference in Berlin entitled “HATE NEWS: Manipulators, Trolls & Influencers”. The two-day event looked into the consequences of online opinion manipulation and strategic hate speech. It investigated the technological responses to these phenomena in the context of the battle for civil rights.

The conference began with Jo Havemann presenting #DefyHateNow, a campaign by r0g_agency for open culture and critical transformation, a community peace-building initiative aimed at combating online hate speech and mitigating incitement to offline violence in South Sudan. More than ten years ago, the bulk of African countries’ online ecosystems consisted of just a few millions of users, whilst today’s landscape is far different. This project started as a response to how social media was used to feed the conflicts that exploded in the country in 2013 and 2016. It calls to mobilize individuals and communities for civic action against hate speech and social media incitement to violence in South Sudan. Its latest initiative is the music video #Thinkbe4uclick, a new awareness campaign specifically targeted at young people.

In Africa, hate campaigns and manipulation techniques have been causing serious consequences for much longer than a decade. The work of #DefyHateNow counters a global challenge with local solutions, suggesting that what is perceived in Europe and the US as a new problem should instead be considered in its global dimension. This same point of view was suggested by the keynote speaker of the day, Nanjala Nyabola, writer and political analyst based in Nairobi. Focusing on social media and politics in the digital age, the writer described Kenya´s recent history as widely instructive, warning that manipulation and rumours can not only twist or influence election results but drive conflicts feeding violence too.

The reliance on rumours and fake news was the principal reason that caused the horrifying escalation of violence following the Kenyan 2007 general election. More than 1,000 people were killed and 650,000 displaced in a crisis triggered by accusations of election fraud. The violence that followed unfolded fast, with police use of brutal force against non-violent protesters causing most of the fatalities. The outbreak of violence was largely blamed on ethnic clashes inflamed by hate speech. It consisted of revenge attacks for massacres supposedly carried out against ethnic groups in remote areas of the country. Unverified rumours about facts that had not taken place. Misinformation and hate were broadcast over local vernacular radio stations and with SMS campaigns, inciting the use of violence, animating different groups against one another.

The general election in 2013 was relatively peaceful. However, ethnic tensions continued to grow across the whole country and ethnic driven political intolerance appeared increasingly on social media, used mainly by young Kenyans. Online manipulation and disinformation proliferated on social media again before and after the 2017 general election campaign.

Nyabola explained that nowadays the media industry in Kenya is more lucrative than in most other African regions, which could be considered a positive aspect, suggesting that within Kenya the press is free. Instead a majority media companies depend heavily on government advertising revenue, which in turn is used as leverage by authorities to censor antagonistic coverage. It should be no wonder Kenyans appear to be more reliant on rumours now than in 2007. People are increasingly distrustful of traditional media. The high risk of manipulation by media campaigns and a duopoly de facto on the distribution of news, has led to the use of social media as the principle reliable source of information. It is still too early to have a clear image of the 2017 election in terms of interferences affecting its results, but Nyabola directly experienced how misinformation and manipulation present in social media was a contributing factor feeding ethnic angst.

Rafiki, the innovative Kenyan film presented at the Cannes Film Festival, is now the subject of controversy over censorship due to its lesbian storyline. Nyabola is one of the African voices expressing the intention to support the movie’s distribution. “As something new and unexpected, this movie might make certain people within the country feel uncomfortable,” she said, “but it cannot be considered a vehicle for hate, promoting homosexuality in violation of moral values.” It is essential not to confuse actual hate speech with something labelled as hate speech to discredit it. Hate speech is intended to offend, insult, intimidate, or threaten an individual or group based on an attribute, such as sexual orientation, religion, colour, gender, or disability. The writer from Nairobi reminded the audience that when we talk about hate speech, it is important to focus on how it makes people feel and what it wants to accomplish. We should always consider that we regulate hate speech since it creates a condition in which social, political and economic violence is fed, affecting how we think about groups and individuals (and not just because it is offensive).

Nyabola indicated few key factors that she considers able to increase the consequences of hate speech and manipulation on social media. Firstly, information travels fast and can remain insulated. Whilst Twitter is a highly public space where content and comments flow freely, Facebook is a platform where you connect just with a smaller group of people, mostly friends, and WhatsApp is based on groups limited to a small number of contacts. The smaller the interaction sphere is, the harder it is for fact-checkers to see when and where rumours and hate speech go viral. It is difficult to find and stop them and their impact can be calculated just once they have already spread quickly and widely. Challenges which distinguish offline hate speech and manipulation from online ones are also related to the way information moves today among people supporting each other without a counterpart and without anyone being held to account.

Nowadays Kenya boasts an increasingly technological population, though not all rural areas have as yet been able to benefit from the country being one of the most connected ones in sub-Saharan Africa. In this context, reports indicate that since 2013 the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica had been working in the country to interfere with elections, organizing conventions, orchestrating campaigns to sway the electorate away from specific candidates. It shall be no surprise that the reach of Cambridge Analytica extended well beyond United Kingdom and USA. In her speech, Nyabola expressed her frustration as she sees that western media focus their attention on developing countries just when they fear a threat of violence coming from there, ignoring that the rest of the world is also a place for innovation and decision making too.

Kenya has one of the highest rates of Internet penetration in Africa with millions of active Kenyan Facebook and Twitter accounts. People using social media are a growing minority and they are learning how to defeat misinformation and manipulation. For them social media can become an instrument for social change. In the period of last year’s election none of the main networks covered news related to female candidates until the campaigns circulating on social media could no longer be ignored. These platforms are now a formidable tool in Kenya used to mobilize civil society to accomplish social, gender and economic equality. This positive look is hindered along the way by the reality of control and manipulation.

Most of the countries globally currently have no effective legal regulation to safeguard their citizens online. The GDPR legislation now in force in the EU obliges publishers and companies to comply with stricter rules within a geographic area when it comes to privacy and data harvesting. In Africa, national institutions are instead weaker, and self-regulation is often left in the hands of private companies. Therefore, citizens are even more vulnerable to manipulation and strategic hate speech. In Kenya, which still doesn’t have an effective data protection law, users have been subject to targeted manipulation. “The effects of such a polluted ecosystem of misinformation has affected and changed personal relationships and lives for good,” said the writer.

On social media, without regulations and control, hatred and discriminations can produce devastating consequences. Kenya is just one of the many countries experiencing this. Hate speech blasted on Facebook at the start of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar. Nyabola criticized that, as in many other cases, the problem was there for all, but the company was not able to combat the spread of ethnic based discrimination and hate speech.

Moving from the interconnections of traditional and online media in Kenyan misinformation ecosystem, the second part of the day focused on privacy implications of behavioural profiling on social media, covering the controversy about Cambridge Analytica. The Friday’s panel opened with the analyses of David Carroll, best known as the professor who filed a lawsuit against Cambridge Analytica in the UK to gain a better understanding of what data the company had collected about him and to what purpose. When he got access to his voter file from the 2016 U.S. election, he realized the company had been secretly profiling him. Carroll was the first person to receive and publish his file, finding out that Cambridge Analytica held personal data on the vast majority of registered voters in the US. He then requested the precise details on how these were obtained, processed and used. After the British consulting firm refused to disclose, he decided to pursue a court case instead.

As Carroll is a U.S. citizen, Cambridge Analytica took for granted that he had neither recourse under federal U.S. legislation, nor under UK data protection legislation. They were wrong. The legal challenge in British court case that centred on Cambridge Analytica’s compliance with the UK Data Protection Act of 1998 could be applied because Carroll’s data was processed in the United Kingdom. The company filed for bankruptcy not long after it was revealed that it used the data of 87 million Facebook users to profile and manipulate them, likely in contravention of UK law. Professor Carroll could never imagine that his activity would demolish the company.

Cambridge Analytica, working with an election management firm called SCL Group, appears to have been a propaganda machine master, able to manipulate voters through the combination of psychometric data. It exploited Facebook likes and interactions above all. Its technique disguised attempts at political manipulation since they were integrated in the online environment.

Carroll talked about how technology and data were used to influence elections and popular voting for the first time in countries like USA and UK, whereas for a much longer time international campaign promoters were hired to act on an international scale. In Carroll’s opinion Cambridge Analytica was an ‘oil spill’ moment. It was an epiphany, a sudden deep understanding of what was happening on a broader scale. It made people aware of the threat to their privacy and the fact that many other companies harvest data.

Since 2012 Facebook and Google have been assigning a DoubleClick ID to users, attaching it to their accounts, de-anonymizing and tracking every action. It is an Ad-tracker that gives companies and advertisers the power to measure impressions and interactions with their campaigns. It also allows third-party platforms to set retargeting ads after users visit external websites, integrated with cookies, accomplishing targeted profiling at different levels. This is how the AdTech industry system works. Carroll gave a wide description of how insidious such a technique can be. When a user downloads an app to his smartphone to help with sport and staying healthy, it will not be a secret that what was downloaded is the product of a health insurance or a bank, to collect data of potential customers, to profile and acquire knowledge about individuals and groups. Ordinary users have no idea about what is hidden under the surface of their apps. Thousands of companies are synchronizing and exchanging their data, collected in a plethora of ways, and used to shape the messages that they see, building up a tailor-made propaganda that would not be recognizable, for example, as a political aid. This mechanism works in several ways and for different purposes: to sell a product, to sell a brand or to sell a politician.

In this context, Professor Carroll welcomed the New European GDPR legislation to improve the veracity of the information on the internet to create a safer environment. In his dissertation, Carroll explained that the way AdTech industry relates to our data now contaminates the quality of our lives, as singles and communities, affecting our private sphere and our choices. GDPR hopefully giving consumers more ownership over their data, constitutes a relevant risk for companies that don’t take steps to comply. In his analyses the U.S. professor pointed out how companies want users to believe that they are seriously committed to protecting privacy and that they can solve all conflicts between advertising and data protection. Carroll claimed though that they are merely consolidating their power to an unprecedented rate. Users have never been as exposed as they are today.

Media companies emphasize the idea that they are able to collect people’s data for good purposes and that – so far – it cannot be proved this activity is harmful. The truth is that these companies cannot even monitor effectively the Ads appearing on their platforms. A well-known case is the one of YouTube, accused of showing advertisements from multinational companies like Mercedes on channels promoting Nazis and jihad propaganda, who were monetizing from these ads.

Carroll then focused on the industry of online advertisement and what he called “the fraud of the AdTech industry.” Economic data and results from this sector are unreliable and manipulated, as there are thousands of computers loading ads and making real money communicating to each other. This generates nowadays a market able to cheat the whole economy about 11 billion dollar a year. It consists of bots and easy clicks tailor-made for a user. The industries enabled this to happen and digital advertising ecosystem has evolved leading to an unsafe and colluded environment.

Alphabet and Facebook dominate the advertising business and are responsible for the use of most trackers. Publishers as well as AdTech platforms have the ability to link person-based identifiers by way of login and profile info.

Social scientists demonstrated that a few Facebook likes can be enough to reveal and accurately predict individual choices and ideas. Basic digital records are so used to automatically estimate a wide range of personal attributes and traits that are supposed to be part of a private sphere, like sexual orientation, religious beliefs, or political belonging. This new potential made politicians excited and they asked external companies to harvest data in order to generate a predictive model to exploit. Cambridge Analytica’s audience-targeting methodology was for several years “export-controlled by the British government”. It was classified as weapon by the House of Commons, at a weapons-grade communications tactics. It is comprehensible then that companies using this tech can easily sell their ability to influence voters and change the course of elections, polarizing the people using social networks.

The goal of such a manipulation and profiling is not to persuade everybody, but to increase the likelihood that specific individuals will react positively and engage with certain content, becoming part of the mechanism and feeding it. It is something that is supposed to work not for all but just for some of the members of a community. To find that small vulnerable slice of the U.S. population, for example, Cambridge Analytica had to profile a huge part of the electorate. By doing this it apparently succeeded in determining the final results, guiding and determining human behaviours and choices.

Bernd Fix, hacker veteran of the Chaos Computer Club in Germany, entered the panel conversation describing the development from the original principle of contemporary cybernetics, in order to contextualize the uncontrollable deviated system of Cambridge Analytica. He represented the cybernetic model as a control theory, by which a monitor compares what is happening into a system with a standard value representing what should be happening. When necessary, a controller adjusts the system’s behaviour accordingly to again reach that standard expected by the monitor. In his dissertation, Fix explained how this model, widely applied in interdisciplinary studies and fields, failed as things got more complex and it could not handle a huge amount of data in the form of cybernetics. Its evolution is called Machine Learning (or Artificial Intelligence), which is based on the training of a model (algorithm) to massive data sets to make predictions. Traditional IT has made way for the intelligence-based business model, which is now dominating the scene.

Machine learning can prognosticate with high accuracy what it is asked to, but – as the hacker explained – it is not possible to determine how the algorithm achieved the result. Nowadays most of our online environment works through algorithms that are programmed to fulfil their master’s interests, whereas big companies collect and analyse data to maximize their profit. All the services they provide, apparently for free, cost users their privacy. Thanks to the predictive model, they can create needs which convinces users to do something by subtle manipulating their perspective. Most of the responsibilities are on AdTech and social media companies, as they support a business model that is eroding privacy, rights and information. The challenge is now to make people understand that these companies do not act in their interest and that they are just stealing data from them to build up a psychometric profile to exploit.

The hacker reported eventually the scaring case of China’s platform “social credit,” designed to cover every aspect of online and offline existence and wanted by the national authorities. It is supposed to monitor each person and catalogue eventual “infractions and misbehaviours” using an algorithm to integrate them into a single score that rates the subjective fidelity into accepted social standards. A complex kind of ultimate social control, still in its prototype stages, but that could become part of our global future where socio-political regulation and control are governed by cybernetic regulatory circuits. Fix is not convinced that regulation can be the solution: to him, binding private actors and authorities to specific restriction as a way to hold them accountable is useless if people are not aware of what is going on. Most people around us are plugged into this dimension where the bargain of data seems to be irrelevant and the Big Three – Google, Facebook and Amazon – are allowed to self-determine the level of privacy. People are too often happy consumers who want companies to know their lives.

The last panellist of the afternoon was the artist and researcher Marloes de Valk, who co-developed a video game for old 1986 Nintendo consoles, which challenges the player to unveil, recognize and deconstruct techniques used to manipulate public opinion. The player faces the Propaganda Machine, level after level, to save the planet.

“Acid rains are natural phenomena”, “passive smoke doesn’t affect the health,” “greenhouse´s effects are irrelevant.” Such affirmations are a scientific aberration nowadays, but in the ‘80s there were private groups and corporations struggling to make them look like legitimate theorizations. The artist from Nederland analysed yesterday´s and today’s media landscape and, basing her research on precise misinformation campaigns, she succeeded in defying how propaganda has become more direct, maintaining all its old characteristics. De Valk looked, for example, for old documents from the American Tobacco Institute, for U.S. corporations‘leaked documents and also official articles from the press of the ´80s.

What remains is a dark-humoured game whose purpose is that of helping people to orientate inside the world of misinformation and deviated interests that affects our lives today. Where profit and lobbyism can be hidden behind a pseudoscientific point of view or be the reason rumours are spread around. The artist and researcher explained that what you find in the game represents the effects of late capitalism, where self-regulation together with complacent governments, that do not protect their citizens, shape a world where there is not room for transparency and accountability.

In the game, players get in contact with basic strategies of propaganda like “aggressively disseminate the facts you manufactured” or “seek allies: create connections, also secret ones”. The device used to play, from the same period of the misinformation campaigns, is an instrument that reminds with a bit of nostalgia where we started, but also where we are going. Things did not change from the ‘80s and corporations still try to sell us their ready-made opinion, to make more money and concentrate more power.

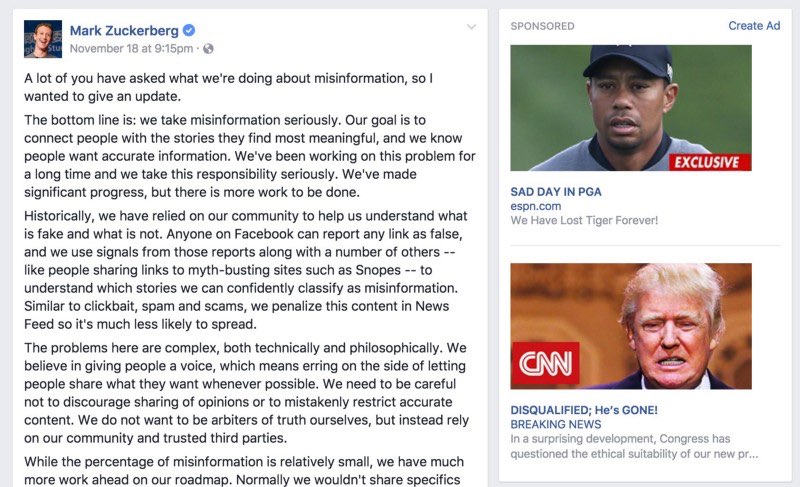

New international corporations like Facebook have refined their methods of propaganda and are able to create induced needs thus altering the representation of reality. We need to learn how to interact with such a polluted dimension. De Valk asked the audience to consider official statements like “we want to foster and facilitate free and open democratic debate and promote positive change in the world” (Twitter) and “we create technology that gives people the power to build community and bring the world closer together” (Facebook). There is a whole narrative built to emphasize their social relevance. By contextualising them within recent international events, it is possible to broad the understanding of what these companies want and how they manipulate people to obtain it.

What is the relation between deliberate spread of hate online and political manipulation?

As part of the Disruption Network Lab thematic series “Misinformation Ecosystems” the second day of the Conference investigated the ideology and reasons behind hate speech, focusing on stories of people who have been trapped and affected by hate campaigns, violence, and sexual assault both online and offline. The keynote event was introduced by Renata Avila, international lawyer from Guatemala and a digital rights advocate. Speaker was Andrea Noel, journalist from Mexico, “one of the most dangerous countries in the world for reporters and writers, with high rates of violence against women” as Avila remembered.

Noel has spent the last two years studying hate speech, fake news, bots, trolls and influencers. She decided to use her personal experience to focus on the correlation between misinformation and business, criminal organizations and politics. On March 8, 2016 it was International Women’s Day, and when Noel became a victim of a sexual assault. Whilst she was walking down the street in La Condesa (Mexico City) a man ran after her, suddenly lifted up her dress, and pulled her underwear down. It all lasted about 3 seconds.

As the journalist posted on twitter the surveillance footage of the assault commenting: “If anyone recognizes this idiot please identify him,” she spent the rest of the evening and the following morning facing trolls, who supported the attacker. In one day her name became trend topic on twitter on a national level, in a few days the assault was international news. She became so subject of haters and target of a misogynistic and sexist campaign too, which forced her to move abroad as the threat became concrete and her private address was disclosed. Trolls targeted her with the purpose of intimidating her, sending rape and death threats, pictures of decapitated heads, machetes and guns.

In Mexico women are murdered, abused and raped daily. They are victims of family members, husbands, authorities, criminals and strangers. Trolls are since ever active online promoting offensive hashtags, such as #MujerGolpeadaMujerFeliz, which translates as ‘a beaten woman is a happy woman’. It is a spectrum of the machismo culture affecting also many Latin American countries and the epidemic of gender-based violence and sexual assault.

Facts can be irrelevant against a torrent of abuse and hate toward journalists. Noel also received hundreds of messages telling her that there was a group of famous pranksters named “master trolls” that used to assault people on the streets in that same way, to make clicks and money out of it. Noel found out that they became best known for pulling down people’s pants and underwear in public, and that this brought them directly to popular tv shows. A profitable and growing business.

The journalist decided to face her trolls one by one and later realized that they were mostly part of an organized activity, not from a TV show but from a political group targeting her, a fact that made everything way more intricate. In two years she “got to know her trolls” as she said, and she studied their ecosystem. The description of the whole story is available on podcast Reply All.

Moving from her story, Noel focused in her second part of dissertation on the relation linking together trolls, criminal organizations, political and social manipulation. She described how, by using algorithms, bots and trolls, it is possible to generate political and election related postings on Facebook and Twitter that go viral. Manipulation comes also by weaponizing memes to propel hate speech and denigration, creating false campaigns to distract public attention from real news like corruption and atrocious cartel crimes.

Marginal voices and fake news can be spread by inflating the number of retweets and shares. Hashtags and trends are part of orchestrated system, where publishers and social media are not held in account for the fraud. Automated or semi-automated accounts, which manipulate public opinion by boosting the popularity of online posts and amplifying rumours. There is a universe of humans acting like bots, controlling hundreds of fake accounts.

Noel is particularly critical against Twitter. Its legal team expressed their engagement facing this “new major problem and novel threats”. The journalist hypothesized that the company had been well aware of the issue since 2010 but decided not to intervene to weed out organized groups manipulating its environment. Moreover, they knew that organized campaigns of discredit can water down the impact of real grassroot spontaneous protests and movements.

These manipulation techniques are responsible for digitally swaying the 2016 election toward the candidate Peña Nieto, organizing an army of thousands of bots to artificially generate trends on Twitter. Trends on this social media move up and down based on the number of tweets in a topic or hashtag related to the speed of sharing or retweeting. Trolls and bots can easily control the trending topic mechanism with their intense spamming activity.

Noel reported that false stories are shared via WhatsApp too, they are difficult to track and the most challenging to debunk. Her portrayal of social media and information market is not different from the description on the first day of the Conference by the writer Najala Nyabola.

To see the future of social media manipulation in politics we need to look at Mexico. All parties in Mexico have used bots to promote their own campaigns, journalists and opponents are overwhelmed with meaningless spam and denigrating hashtags. Offline, media landscape across Mexico is not free and organised crime has been using propaganda and manipulation to further its own aims. President Peña Nieto’s administration spent hundreds of millions of dollars on advertising, making media dependent and colluded. This system suppresses investigative articles and intimidates reporters.

The next general election is scheduled for July 1st. Andrea Noel warned that manipulation, trolls and bots are already irreversibly polluting the debate, in a country where more than 100 candidates have already been murdered (at the time of the Conference) and a history of corruption makes media and authorities unreliable in the eyes of people.

As a response, universities and NGOs formed an anti-fake news initiative called “Verificado” a platform that encourages people to forward stories found on social media using the hashtag #QuieroQueVerifiquen, ‘I want you to verify this’. The researchers of this project answer with fact-checking and publish their findings online. When asked, Noel expressed appreciation for the efforts of organizations and civil society. However, she is becoming increasingly disillusioned. She can see no immediate prospect of finding solutions able to slow or halt the impact of misinformation and hate speech online. In her opinion projects like Verificado can be easily hijacked. On the other side genuine social media campaigns are still an effective tool in the hands of civil society but the lack of trust in media fed by corruption often undermines all efforts to mobilize society, leading the public to routinely dismiss initiative to fight injustice.

When asked about the possibility to shut down social networks as a solution, Noel could not say she did not think of it. A first step could be to oblige media like Twitter and Facebook to guarantee users a safe environment where the economic interest comes after the need of a hate speech and manipulation free environment. The way they operate confirms they are content platforms and as such media entities they lack of transparency and accountability. These companies shirk their obligation for publishing responsibly. They should be held to account when they spin lies and allow groups to act unethically or against target single or communities.

The program of the second day continued with the presentation of the documentary The Cleaners, by Hans Block and Moritz Riesewieck, a project started in 2013 and in the cinemas at the time of the Conference. Initially, the authors wanted to learn more about the removal of pedo-pornographic content and sexualised images of children on Facebook. Social networks have largely pledged to work harder to identify and remove illegal, offensive and improper content, to limit violations and deny hate speech. But how does it work? Who decides what shall be cancelled and on what basis? These questions arose frequently during the first part of the Hate News conference and the German authors could answer it in relation to the social media Facebook, subject of their documentary.

The choice about what shall and what shall not belong the internet is a subjective one. Content moderators, who censor postings and content on platforms like Facebook, have indeed a controversial and central role. Their work is subject to almost no open scrutiny. However, it shapes attitudes and trends of both individuals and social groups, impacting the public discourse and the cultural dialectic. When a social network decides to censor content and delate videos about the effects of drone bombings, since by showing civilian victims Daesh builds its propaganda, it makes a choice that affects the narration of events and the perception of facts.

Investigating how the social media platform Facebook polices online content, and the direct impact of these decisions on the users’ interactions, Block and Riesewieck ended up in the Manila, where Facebook boasts its biggest department for content moderation, with more than 10,000 contractors. The Cleaners shows how this platform sees its responsibilities, both toward people moderating and censoring the content and its users. Based on interviews with Philippine content moderators at work, the documentary contributes to the debate about the public responsibilities of social media and online platforms for publishing, from political manipulation and propaganda to data protection.

Humans are still the first line of content moderation and they suffer horrible consequences and traumas for they see daily the worst of the web. Companies like Facebook have developed algorithms and artificial-intelligence tools able to work as a first level, but the most of this technology cannot substitute human capabilities. Certain content moderators describe themselves as custodians of moral values, as their work turns into decisions that can shape social media and consequently society. There are indeed countries where people consider Facebook as the Internet, ignoring that the world wide web is much more than that social media.

The authors go beyond, showing that Manila cleaners are influenced by their cultural background and social believes. They build a parallel between Philippines’ Catholicism and discourse about universal enslavement of humans to God and sacrifice, photographed in the years of the government of Rodrigo Duterte, controversial president who is leading a war against drugs and moral corruption, made of extrajudicial killings and a violent, abusive approach.

Despite denials by the company, cleaners in Manila also moderate Europeans’ posts and they are trained for that. A single world, a historical reference, together with a picture can make all the difference between an innocent joke and hate speech. Whilst memes can be used as weapons, for example by the alt-right groups or by reactionary movements against gender equality, cleaners have just few seconds to decide between removing and keeping a content, checking more than 35,000 images per day. The authors of the documentary explained how it is almost impossible for them to contextualize content. As a result, there is almost no control over their work, as a team leader can just proof 3% of what a cleaner does.

The last panel closing the conference on the second day was moderated by the curator, artist and writer Margarita Tsomou. American independent online harassment researcher Caroline Sinders focused her dissertation on online protests and political campaigns in the frame of the hate speech discourse. She recalled recent events able to pollute the public debate by creating chaotic and misleading messages to enhance a reactionary anti-progressive culture. Misogyny thrives on social media and hatred of women and entrenched prejudice against them are everywhere in the Internet. Fake online campaigns are often subtly orchestrated targeting women.

In 2014 on social networks appeared an organised action associated with the hashtag #EndFathersDay, presented as a feminist political campaign to eradicate the celebration of Father’s Day as a “celebration of patriarchy and oppression”. That campaign had nothing to do with feminism and grassroots movements, it was a harassment campaign against women, a fake with manipulated images and hundreds of trolls to feed a sentiment of hatred and hostility against activists for civil rights and equality.

It is not the only case of its genre. The #Gamergate campaign, that in 2014 targeted several women from the video game industry (on Twitter, Reddit, 4chan, and 8chan) falls into this context. The campaign was not immediately perceived as a harassment instrument due to attempts of making it appear as a movement against political correctness and bad journalistic ethics. It was though a misogynistic reactionary campaign against female game developers, that soon revealed its true face as right-wing sexist backlash. Under this hashtag women were indeed victims of doxing, threats of rape and death.

Sinders explained that in the last several years we have seen a shift from a sectorial market to a global dimension where we are all potentially identifiable as gamers. Video games and gaming culture are now mainstream. People are continuously connected to all kind of devices that enable the global gaming industry to generate more than 100 billion dollar every year. The Gamergate controversy reopened the debate that gaming is a world for (white) males, pointing out how the video game industry has a diversity problem, as sexism, racial and gender discrimination in video game culture appear to be a constant factor.

A relevant aspect of the controversy is related to how trolls organised and tried to reframe the narrative of the harassment campaign. Instead of a misogynistic and violent action, they claimed it was about journalistic integrity and candid reviewing, thus denouncing a collusion between the press and feminists and social critics. Most of the trolls and supporters were anonymous, ensuring that the campaign be defined merely by the harassment they have committed against women and as a reaction to what they reported as the increasing influence of feminism on video game culture.

Sinders concluded her speech explaining that organised actions and campaigns like those described above are structured on precise tactics and harassment techniques that have already entered in our vocabulary. Words like doxing, swatting, sealioning and dogpiling are neologisms that describe strategies of hate speech and harassment nowadays common.

The Norwegian journalist Øyvind Strømmen, author and managing editor of Hate Speech International, has extensively researched and written about how extreme right movements and religious fundamentalism are able to build an effective communication online and use the web as an infrastructure to strategically enhance their activities. He joined the panel explaining that despite his intense international activity, he has never been subjected to harassment and death threats like his female colleagues, whilst he finds daily-organised activities to sow hatred and intolerance to repress women.

Cathleen Berger, former International cyber policy coordination staff at the German Foreign Office and currently lead of Mozilla’s strategic engagement with global Internet fora, closed the conference with an analyses of the new German NetzDG legislation, defined by media as an extreme example of efforts by governments to make social media liable for what circulates on their pages. The law was adopted at the end of 2017 to combat illegal and harmful content on social media platforms. It is defined also as anti-hate-speech law as it was written in the historical context of the refugees’ mass migration to Europe and the new neo-nazi propaganda from political formations like the Alternative for Germany (AfD). At the time, fake news and racist material were shared online on several mainstream channels for the first time, with relevant impact on public opinion.

The new German law requires social media companies to provide users with a wide-ranging complaints structure to make sure that discriminatory and illegal posts can quickly be reported. It is left to social media platforms to decide if a certain reported content represents a promotion of or an incitement to terrorism, child abuse, hate or discrimination of any kind.

The law forces social media to act quickly too. Under NetzDG, social media platforms with more than 2 million users in Germany have 24 hours to remove posts reported by users for being illegal. Facebook, Twitter and YouTube seem to be the law’s main focus. Failure to comply with the law carries a fine up to € 50 million.

The German government’s Network Enforcement Act has been criticised for its risks of controversial inadvertent censorship, limiting legitimate expressions of opinion and free speech. Once again private companies, that are neither judges nor any kind of public authority, have the power to decide whether reported content is in fact unlawful.

All credit is due to Tatiana Bazzichelli and the Disruption Network Lab, who provided once again a forum for discussion and exchange of information that provokes awareness on matters of particular concern from the different perspectives of the guests – especially women – able to photograph with their international activities and their researches several topical issues.

This 13th Conference (https://www.disruptionlab.org/hate-news/) was a valid opportunity to discuss and rationalise the need for civil society to remain globally vigilant against new forms of hate speech, manipulation and censorship. Ideological reasons behind hate speech and online manipulation are on the table and the framing is clear enough to hold online media and publishing companies accountable for the spread of frauds, falsehood and discrimination within their networks.

Companies like Facebook and Twitter have demonstrated their inability to recognise real threats and appear to be thinking of profit and control without considering the repercussions that their choices have. However, we are delegating them the power to define what is legal and what is not. Their power of censorship shapes society, interfering with fundamental rights and freedoms, feeding conflicts and polarization. This legal response to hate speech and manipulation in the context of the battle for privacy and civil rights is completely inadequate.

Propaganda and hate speech have historically been tools used in all countries to influence decision making and to manipulate and scare public opinion. Forms of intrusive persuasion that use rumours or manipulation to influence people’s choices, beliefs and behaviours are now occupying the web too. Individuals should be able to give due value to their online interactions, focusing on the risks that they run when they click on something. There is too little awareness of how companies, aggressive trolls, criminals, private groups and advertisers subtly manipulate online environment for political and economic interest.

Such a corrupted online ecosystem – where almost nothing of what we meet can be trusted and where individuals and communities are exposed to private interest – generates often hate campaigns targeting women and minorities, normalising crimes, reactionary gender stereotyping and deplorable cultural customs. As all speakers suggested, Cyber-ethnography can be a worthwhile tool as an online research method to study communities and cultures created through computer-mediated social interaction. It could be helpful to study local online exchanges and find local solutions. By researching available data from its microcosmos, it is possible to prevent ethnic, socioeconomic, and political conflicts linked to the online activity of manipulators, destructive trolls and influential groups, to disrupt the insularity of closed media and unveil the economic and political interest behind them.

HATE NEWS: Manipulators, Trolls & Influencers

May 25-26, 2018 – Kunstquartier Bethanien, Berlin

disruptionlab.org/hate-news/

Info about the 13th Disruption Network Lab Conference, its speakers and thematic is available online here:

https://www.disruptionlab.org/hate-news

To follow the Disruption Network Lab sign up for its Newsletter and get informed about its Conferences, ongoing researches and projects. The next Disruption Network Lab event is planned for September. Make sure you don´t miss it!

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter and Facebook

Photocredits: Maria Silvano for Disruption Network Lab