Join us in London at the DAOWO ‘Blockchain & Art Knowledge Sharing Summit’

DAOWO (Distributed Autonomous Organisations With Others) Summit UK facilitates cross-sector engagement with leading researchers and key artworld actors to discuss the current state of play and opportunities available for working with blockchain technologies in the arts. Whilst bitcoin continues to be the overarching manifestation of blockchain technology in the public eye, artists and designers have been using the technology to explore new representations of social and cultural economies, and to redesign the art world as we see it today.

Discussion will focus on potential impacts, technical affordances and opportunities for developing new blockchain technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

Programme

9.00 Registration

9.30 Welcome and Scene Setting

State of the Arts: Blockchain’s Impact in 2019 and Beyond | A comprehensive overview of developments from critical artistic practices and emergent blockchain business models in the arts. DAOWO Arts and Blockchain pdf download (Catlow & Vickers 2019).

Presentation and hosted discussion with Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers

10.30 Coffee

10.45 Protecting the Rights of Indigenous Australian Artists. What part can Blockchain technologies play?

The Copyright Agency, Australia in conversation with Mark Waugh, DACS UK

11.30 Towards a Decentralised Arts Economy

The launch of Zien, the new dApp for artists will be followed by a presentation and panel discussion with Peter Holsgrove, and artists of A*NA around the implications of tokenising artistic practices.

12.15 Digital Catapult panel

12.45 Wrap up, takeaways and final discussion

Ruth Catlow, Ben Vickers & Mark Waugh

Contributors include:

Ruth Catlow Co-founder of Furtherfield & DECAL Decentralised Arts Lab

Peter Holsgrove, Founder of A*NA

Ben Vickers, CTO Serpentine Galleries, Co-founder unMonastery

Mark Waugh, Business Development Director DACS

Through two UK summits, the DAOWO programme is forging a transnational network of arts and blockchain cooperation between cross-sector stakeholders, ensuring new ecologies for the arts can emerge and thrive.

DAOWO Summit UK is a DECAL Decentralised Arts Lab initiative – co-produced by Furtherfield and Serpentine Galleries in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London. This event is realised in partnership DACS, UK.

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

Octavia E Butler had a vision of time as circular, giving meaning to acts of courage and persistence. In the face of social and environmental injustice, setbacks are guaranteed, no gains are made or held without struggle, but societal woes will pass and our time will come again. In this sense, history offers solace, inspiration, and perhaps even a prediction of what to prepare for.

The Time Portals exhibition, at Furtherfield Gallery and online spaces, celebrates the 150th anniversary of Finsbury Park. As one of London’s first ‘People’s Parks’, designed for free movement and thought, it is the perfect location to create a mass investigation of radical pasts and futures, circling back to the start as we move forwards.

Each artwork invites audience participation – either in its creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more imaginings of past and future urban green spaces and beyond.

Time Portals from Furtherfield on Vimeo.

An interactive wall depicting the urban green space of Finsbury Park as a machine for radical re-assemblage. The external billboard can be scanned with an Augmented Reality app to reveal the secret of realising progressive visions for the future. Scan the message in the Gallery to see the billboard image animated.

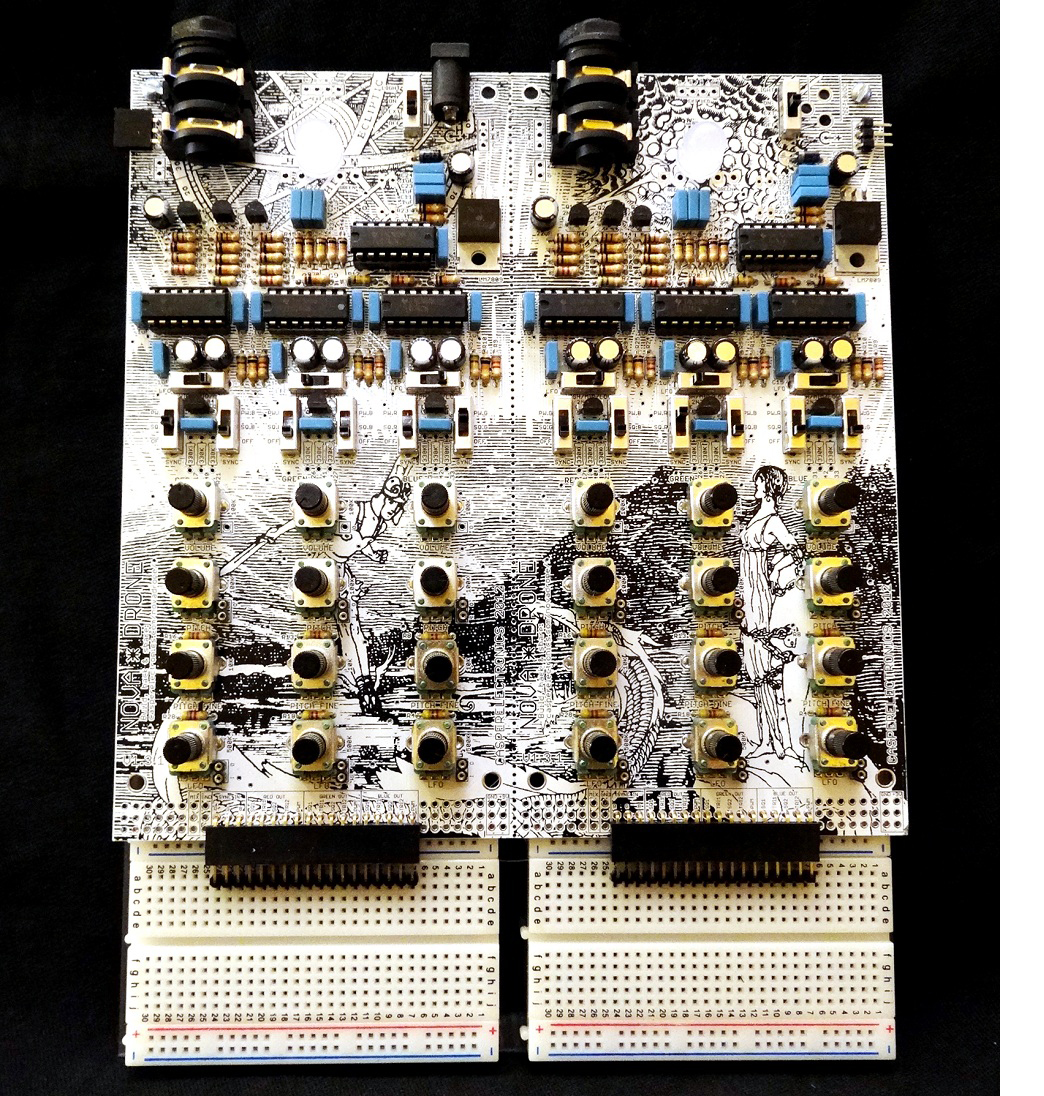

An interactive machine designed and built to respond to environmental change and inspire new rites for our troubled times. A slideshow of the machine as it is imagined and built will be presented alongside a ritualised unveiling in the Autumn.

Join the Future Machine design team at Furtherfield Commons in Finsbury Park to build a new artwork that will help us to respond to environmental change…as the future unfolds. Sign up to take part in up to 4 workshops that involve talking, thinking & making, using interactive technology and scientific sensors, helping to design and build the Future Machine itself.

Workshop times/dates and sign-ups:

In collaboration with Amanda Wilson (MARA Project/Imperial College) and Professor Daniel Polani (University of Hertfordshire). Supported by EMAP, Arts Council England, and Haringey Council

An underwater robotic installation which explores what ‘life’ might mean in a future transformed by climate change and artificial intelligence. The work is based on new research into archaea, which are single-celled, ancient microbes that can survive in hot, polluted environments, combined with the latest innovations in machine learning. Now living at Furtherfield Gallery the “ArchaeaBot” is the ‘ultimate’ species for the end of the world as we know it.

With creative team: Hugo Stanbury, Nick Lambert, Marius Matesan, Carl Smith, James E. Marks, Chris Szkoda

Through in-depth research James revisits a historical black woman who lived in the Finsbury Park area 150 years ago, embodies and reimagines her then and 150 years into the future. Produced together with Ravensbourne University PlayLabZ and Holotronica, experience time travel and holographic mixed reality at the Furtherfield Gallery throughout the summer.

Part 2 of Circle of Blackness will be revealed later in the summer.

This video work is a complete rendition of the 1960s film version of HG Wells Novella re-edited by Thomson & Craighead into alphabetical order from beginning to end. In doing this, the artists attempt to perform a kind of time travel on the movie’s original timeline through the use of a system of classification.

Future Machine Artwork Workshops:

26 Mar, 20 Apr, 11 May, 18 Jun, 13 Jul, Furtherfield Commons

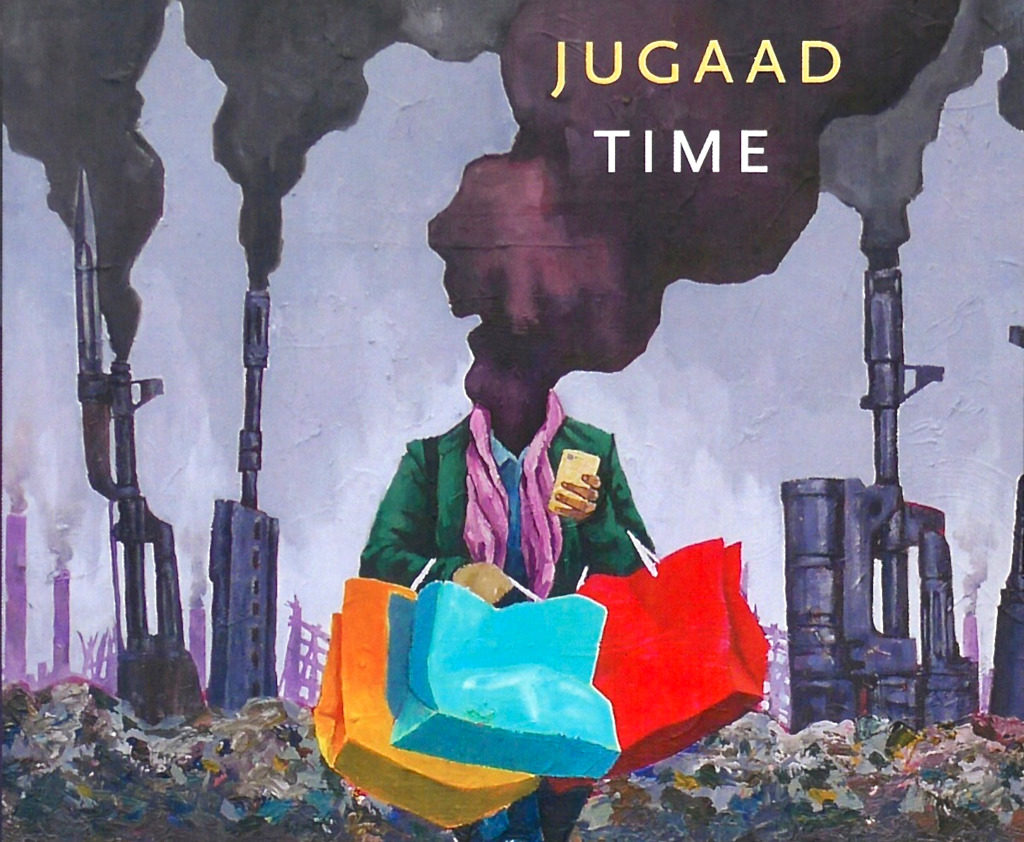

Book Launch Event for Jugaad Time by Amit S. Rai:

27 Apr 14.00-16.00, Furtherfield Commons

Find a Line to Follow and Face The Future! ‘Walkshops’:

5 May 18 May, 10 Aug, Furtherfield Commons

Free, Fair, and Alive! A People’s Park Play Day:

10 Aug 10.00-17.00, Furtherfield Commons

Future of Money Workshops:

10 Aug, 10.00-17.00, Furtherfield Commons, other dates TBC,

Citizen Sci-Fi 3-Day Artworkers Lab Event:

14-15 Sept, time TBC, Furtherfield Commons

Future Machine Procession in Finsbury Park:

12 Oct, 3:00 pm – 8:00 pm, join at any point

This 3-year programme combines citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

#CitSciFi – crowdsourcing creative and technological visions of our communities and public spaces, together.

Anna Dumitriu is a British artist who works with BioArt, sculpture, installation, and digital media to explore our relationship to infectious diseases, synthetic biology and robotics. She has an extensive international exhibition profile including ZKM, Ars Electronica, BOZAR, The Picasso Museum, The V & A Museum, Philadelphia Science Center, MOCA Taipei, LABoral, Art Laboratory Berlin, and The Museum of the History of Science Oxford. She was the 2018 President of the Science and the Arts section of the British Science Association and holds visiting research fellowships at the University of Hertfordshire, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, and Waag Society, as well as artist-in-residence roles with the Modernising Medical Microbiology Project at the University of Oxford, and with the National Collection of Type Cultures at Public Health England. Dumitriu is a renowned speaker and has presented her work at venues including TATE Modern, Princeton University, Imperial College, La Musee de la Chasse et de la Nature, The Mendel Museum and UCLA. Her work is featured in many books including “Bio Art: Altered Realities” published by Thames and Hudson in 2016 and many other significant publications across contemporary art and science including Artforum International Magazine, Leonardo Journal, The Art Newspaper, Art Quarterly, Nature and The Lancet. Dumitriu’s work has a strong focus on the ethical implications of emerging technologies drawing threads across time, exploring future scenarios by reflecting on the past.

Elsa James is a visual artist, activist and producer based in Southend-on-Sea, Essex, who grew up in west London during the 1970s and ’80s. Her solo practice encompasses lens-based performance, language and text, and recently the use of aural and the archive to explore regionality of race; black subjectivity; and the historical, temporal and spatial dimensions of what it means to be black in Britain. She is currently developing work exploring alienation and outsiderness experienced as a black woman living in Essex since 1999. Forgotten Black Essex (2018) embodies two place-specific narratives from our national archives of two overlooked, under-researched and recognised black women in Essex. Her social practice includes advocating for the inclusion of marginalised communities in the arts sector. New Ways of Seeing, Telling and Making (2018), a visual provocation and participatory lab at the Social Art Summit, asked questions about how we can ‘genuinely’ address barriers to participation and involvement in the arts for BAME communities. In 2015 she was commissioned to research the asylum and refugee community in Southend. This culminated in a 38-page report exposing the council’s lack of provision for the needs of asylum seekers, failed asylum seekers and refugees living in Southend.

Rachel Jacobs is an artist, researcher and games designer. She co-founded the artist-led collective Active Ingredient in 1996 and the commercial games company Mudlark Production Company in 2007. She completed a Doctorate in Computer Science in 2014. Rachel is a practising artist exhibiting nationally and internationally, and a Research Associate at the Horizon Digital Economy Institute, University of Nottingham. Her artworks include the award winning ‘Heartlands (Ere Be Dragons)’ one of the first mobile games that took place on city streets in Sao Paulo, Yokhama, Berlin, Paris, Cambridge, Bristol and Nottingham; ‘A Conversation Between Trees’, a touring artwork and schools exchange using environmental sensors to connect forests in the UK and Brazil; and ‘The Prediction Machine’, an interactive installation that predicts the future impacted by climate change. Rachel is currently developing a series of artists interventions ‘Creating Rituals for When The Future Comes’, alongside a mobile interactive artwork the ‘Future Machine’.

Dr Nick Lambert is Director of Research at Ravensbourne University London, where immersive environments and mixed reality experiences are being developed. He researches the application of technology in contemporary art and visual culture. He has written on the history of computer art and engaged with artists and theorists in this field. He has also created artworks for immersive environments including fulldome, and interactive exhibits.

James E. Marks, PsychFi – A natural born new media pioneer, award winning social video, & dimensional computing arts for good maker, curator & speaker. With 4 decades of hands-on experience & experimental knowledge collaborating on Brand / Crowd / Arts Council funded “Sub & Pop Culture Mixed Up Reality Experiences”. Recent collaborations include V&A, London Design Festival, Boomtown Fair, Mobile World Congress, Ravensbourne University, Bethesda, SubPac, Modern Panic, Sci-Fi-London & BBC Click

Marius Matesan is creating narratives using real and virtual installation art, noted mostly for his work on theatre stages across Europe and more recently for his Mixed Reality experiences. Mixing reality with the imaginary, using sound, projection mapping, spatial computing and virtual reality. His work revolves around pushing the boundaries of perception, awareness and reality, creating installations that are often addressing social issues with a psychedelic twist.

Alex May is a British artist creating digital technologies to challenge and augment physical and emotional human boundaries on a personal and societal level in a hyper-connected, software mediated, politically and environmentally unstable world. He works with light, code, and time; notably algorithmic photography, robotic artworks, video projection mapping installations, interactive and generative works, video sculpture, performance, and video art. Alex has exhibited internationally including at the Francis Crick Institute (permanent collection), Eden Project (permanent collection), Tate Modern, Ars Electronica (Austria), LABoral (Spain), the Victoria & Albert Museum, Royal Academy of Art, Wellcome Collection, Science Museum, Bletchley Park, One Canada Square in Canary Wharf, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas (Venezuela), the Science Gallery in Dublin, Princeton University, University of Calgary (international visiting artist 2016), Texas A&M University, and the Beall Center for Art + Technology, University of California, Irvine. Alex is a Visiting Research Fellow: Artist in Residence with the School of Computer Science of University of Hertfordshire, and a Digital Media Arts MA sessional lecturer at the University of Brighton.

http://www.alexmayarts.co.uk

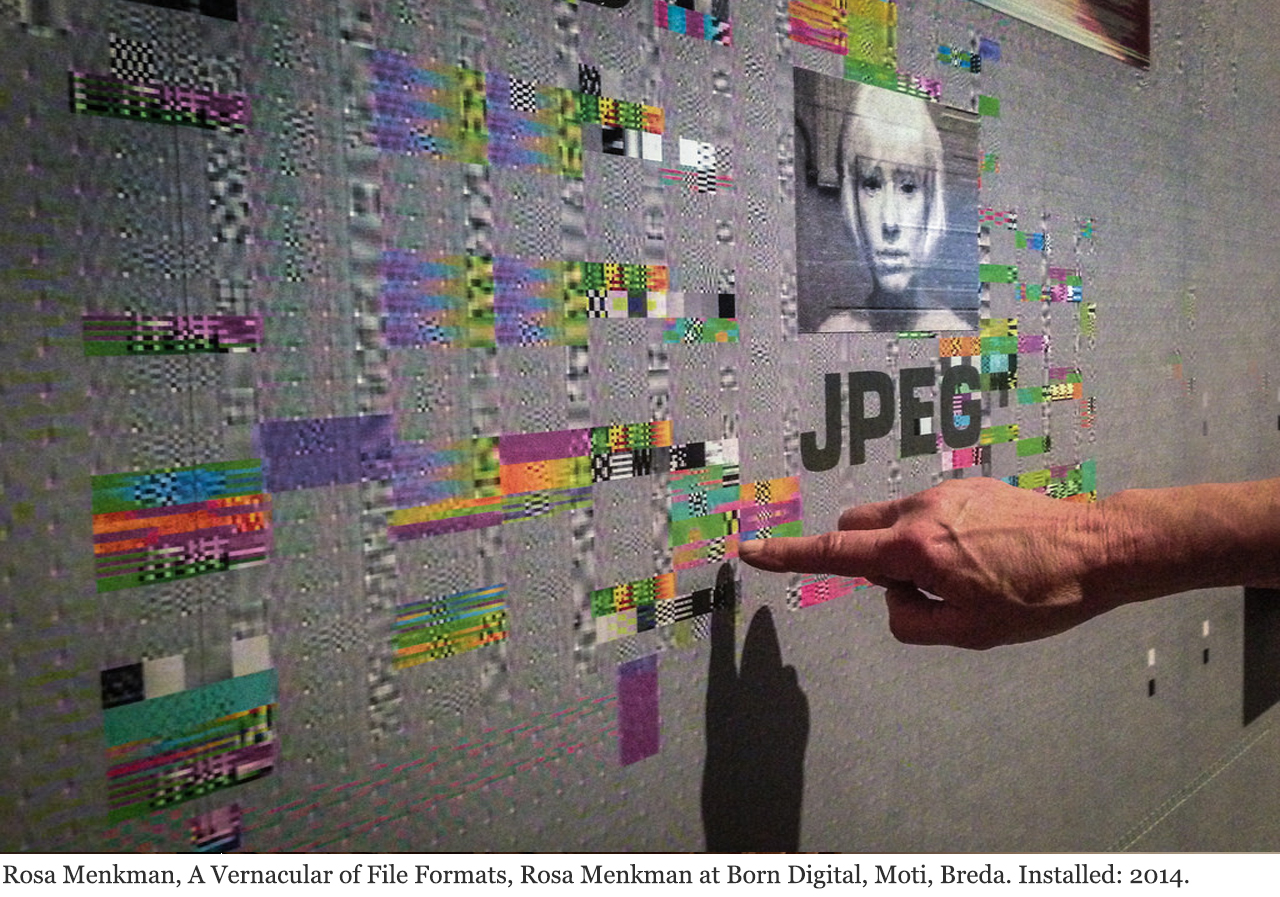

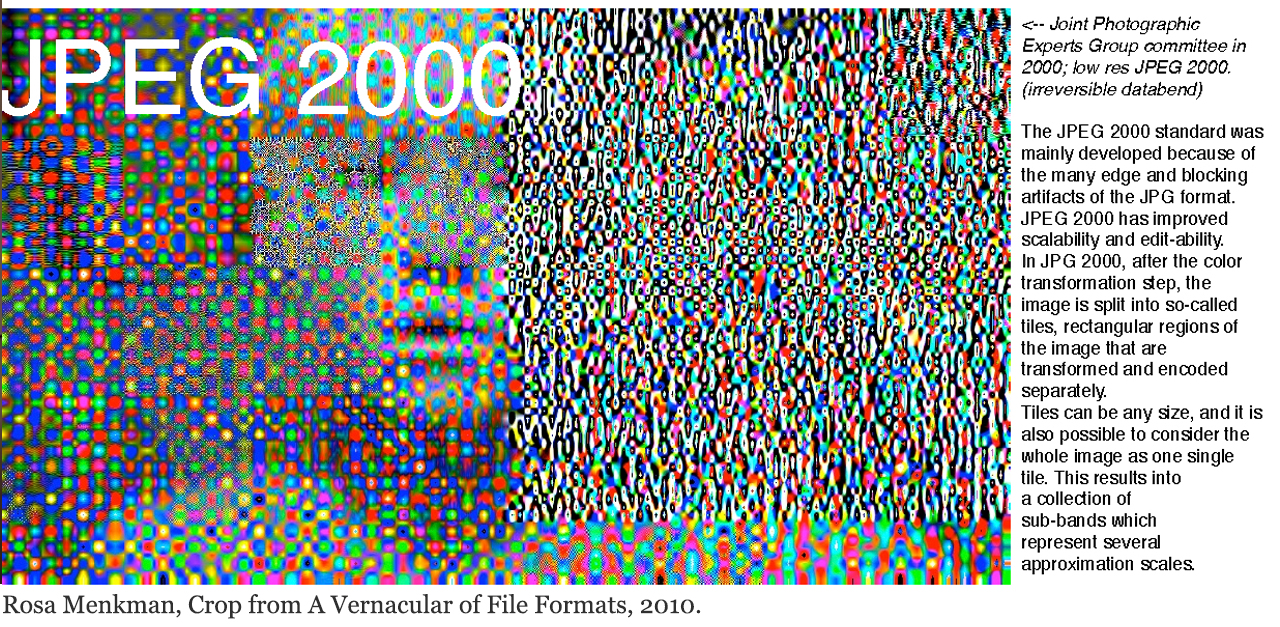

Antonio Roberts is a new media artist and curator based in Birmingham, UK. He uses technology-driven processes to explore issues surrounding open source software, free culture and collaborative practices. His visual and performance work has been featured at galleries and festivals including databit.me in Arles, France (2012), Glitch Moment/ums at Furtherfield Gallery, London (2013), Loud Tate: Code at Tate Britain (2014), glitChicago at the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art in Chicago, US (2014), Permission Taken at Birmingham Open Media and University of Birmingham (2015-2016), Common Property at Jerwood Visual Arts, London (2016), Green Man Festival, Wales (2017) and Barbican, London (2018). He has curated exhibitions and projects including GLI.TC/H Birmingham (2011), the Birmingham editions of Bring Your Own Beamer (2012, 2013), µChip 3 (2015), Stealth (2015), and No Copyright Infringement Intended (2017).

Carl H Smith is Director of the Learning Technology Research Centre (LTRC) and Principal Research Fellow at Ravensbourne University London. His background is in Computer Science and Architecture. He has 17 years experience conducting R+D into the application of hybrid technologies for perceptual, cognitive and creative transformation. He has worked on a number of large-scale FP7 and Leonardo Life Long Learning European projects. He is currently working on 4 EU projects including the Horizon 2020 project ‘[WEKIT] Wearable Experience for Knowledge Intensive Training’ which aims to create ‘Wearable Experience (WE)’ – an entirely new form of media. His research interests include Embodied Cognition, Spatial Literacy, Perceptual Technology and Hyperhumanism. His other projects involve Context Engineering, Umwelt Hacking, Natural Media, Sensory Augmentation, Memory Palaces, Artificial Senses and Body Hacking. He is co-founder of the London Experimental Psychonautics Club and co-founder of the Cyberdelic Society. Both organisations explore the myriad of ways it is possible to produce and examine Altered States of Consciousness. He has previously worked at the Computing departments at London Metropolitan University, Glasgow University and Sheffield University. The Learning Technology Research Centre (LTRC) conducts design research into the application of information and communication technologies to augment, support and transform cognition.

Hugo Stanbury has worked in the event and entertainment industry for over a decade. Inspired most by the area where cutting edge technology is used for properties rather than purpose, he works hard to balance sound technical delivery with new creative concept. He currently works as Operations Director at Holotronica – the UK company behind Hologauze. Hologauze is the world leading gauze for holographic effects with clients from BMW to Beyonce. Holotronica are specialists in a range of holographic displays, analogue holography and 3D content.

Studio Hyte is a London based multidisciplinary design studio who place research and concept above medium. Working between graphic design, interaction and emergent forms of visual communication, we aim to create meaningful and thought provoking work. Formed of a small group of individual practitioners, Studio Hyte is the middle ground where all of our interests and practices meet. As such our collective practice and research covers a broad spectrum of topics including; language, inclusion & accessibility, egalitarian politics & alternative protest and technology & the human. With an emphasis on process, we often create critical narratives through our work in order to conceptualise through making. Collectively, our visual practice is a means through which we can plot out a conceptual landscape in order to understand and explore real-world scenarios. Studio Hyte works on self-directed research projects, commissions and client-led projects for a small pool of like minded organisations and individuals.

Chris Szkoda, Kaws Infinity – Games Designer/ VFX Artist, works on designing mixed/virtual reality apps for a social mixed reality experience playground at Ravensbourne University London. Keen to support social good & diversity projects, working directly with students and helping them make their creative ideas a reality. He has expertise in immersive technology, VR modelling and painting in Google Tilt Brush and MasterpieceVR software.

Jon Thomson (b. 1969) and Alison Craighead (b. 1971) are artists living and working in London. They make artworks and installations for galleries and specific sites including online spaces. Much of their recent work looks at live networks like the web and how they are changing the way we all understand the world around us. Having both studied at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee, Jon is Reader in Fine Art at The Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, while Alison is a reader in contemporary art and visual culture at University of Westminster and lectures in Fine Art at Goldsmiths University.

http://www.thomson-craighead.net/

Artist Rachel Jacobs is working in partnership with Furtherfield to build a Future Machine in Finsbury Park and you are invited to help build it.

Location:

Furtherfield Commons

269-271 Seven Sisters Road

Finsbury Park

N4 2DE

Sign up to take part in four workshops that will involve thinking about the future (in response to environmental change) and helping to design and build the Future Machine, towards an unveiling at Furtherfield Gallery this Autumn and tour of England in 2019/2020.

The workshops are designed to bring together people with ALL views on environmental change – denier, worrier, eco-warrior, confused, conspiracy theorist, lover of trees – everyone is welcome! The workshops will involve talking, thinking, making things with all kinds of arts and craft materials, as well as using interactive technology and scientific sensors. You are welcome to sign up to one or all of the workshops, you don’t need to attend them all to take part.

Furtherfield Commons is a wheelchair accessible venue. Please email the artist at: promises@thepredictionmachine.org if you want to discuss any accessibility requirements.

Workshop times/dates:

Book now!

Refreshments will be provided

The Future Machine sits on a hand cart ready for the journey, travels the country and plugs into a greater whole of many parts. It stands as a witness to the places, people, stories and events of these turbulent times, as the Earth changes, and we take a journey into an uncertain future.

The Future Machine is a new artwork, a large interactive machine, built to help us to respond to environmental change as the future unfolds. The machine will record people’s visions of the future, make predictions, facilitate new rituals and helps us to make decisions about the future we want, not one we fear.

The artwork will be created in collaboration with a team of engineers, programmers, climate scientists from the British Antarctic Survey, researchers from the University of Nottingham, and participants in a series of artist-led workshops, scheduled to take place in London and Nottingham in 2019.

The Future Machine will be built by YOU over the coming months and unveiled in an Autumn ritual – details to follow

The Future Machine is part of Furtherfield’s 2019 programme: Time Portals.

In 2019 we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Finsbury Park, and we time travel through its past and future with the launch of our Citizen Sci-fi programme and methodology. Dominant sci-fi franchises of our time, from Black Mirror to Westworld, have captured popular attention by showing us their apocalyptic visions of futures made desperate by systems of dominance and despair.

What is African-American author, Octavia E. Butler’s prescription for despair? Sci-fi and persistence. Sci-fi as a tool for getting us off the beaten-track and onto more fertile ground, and persistent striving for more just societies.The 2015 book Octavia’s Brood honoured her work, with an anthology of sci-fi writings from US social justice movements and this inspired us to try a new artistic response to the histories and possible futures of Finsbury Park.

Furtherfield’s Citizen Sci-Fi methodology combines citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

Each artwork in the forthcoming exhibition invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

So where do we start? Last year we invited artists, academics and technologists to join us in forming a rebel alliance to fight for our futures across territories of political, cultural and environmental injustice. This year both our editorial and our exhibition programme are inspired by this alliance and the discoveries we are making together.

To kick off this year’s Time Portals programme at Furtherfield, in April we will host the launch and discussion around Jugaad Time, Amit Rai’s forthcoming book. This reflects on the postcolonial politics of what in India is called ‘jugaad’, or ‘work around’ and its disruption of the neoliberal capture of this subaltern practice as ‘frugal innovation’. Paul March-Russell’s essay Sci-Fi and Social Justice: An Overview delves into the radical roots and implications of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). This is a topic close to our hearts given our own recent exhibitions Monsters of the Machine and Children of Prometheus, inspired by the same book. Meanwhile we’ve been hosting workshops with local residents exploring our visions for Finsbury Park 150 years into the future. To get a flavour of these activities Matt Watkins’ has produced an account of his experience of the Futurescapes workshop at Furtherfield Commons in December 2018.

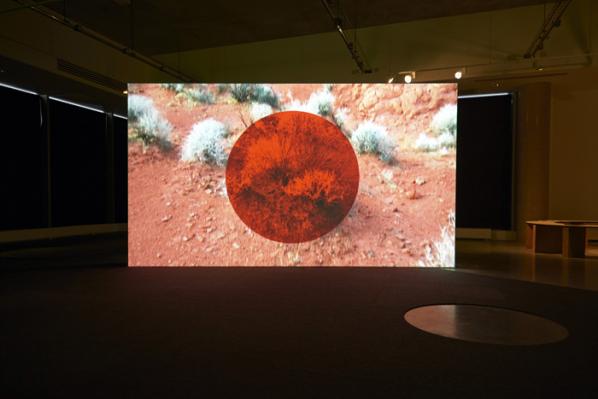

In May we will open the Time Portals exhibition which features several new commissions. These include Circle of Blackness by Elsa James. Through local historical research James will devise a composite character to embody the story of a black woman from the locality 150 years ago and 150 years in the future. James will perform a monologue that will be recorded and produced by hybrid reality technologist Carl Smith and broadcast as a hologram inside the Furtherfield Gallery throughout the summer. While Futures Machine by Rachel Jacobs is an Interactive machine designed and built through public workshops to respond to environmental change – recording the past and making predictions for the future while inspiring new rituals for our troubled times. Once built, the machine occupies Furtherfield Gallery, inviting visitors to play with it.

Time Portals opens on May 9th (2019) with other time traveling works by Thomson and Craighead, Anna Dumitriu and Alex May, Antonio Roberts and Studio Hyte. Visitors will be invited to participate in an act of radical imagination, responding with images, texts and actions that engage circular time, long time, linear time and lateral time in space towards a collective vision of Finsbury Park in 2169.

From April onwards, a world of activities, workshops with local families and their enriching noises, reviews, interviews and an array of experiences will unfold. Together we dismiss the dystopian nightmares and invite communities to join us in one of London’s first “People’s Parks” to revisit and recreate the future on our own terms together.

Marc Garrett will be interviewing Elsa James, about her artwork Circle of Blackness, and Amit Rai about his book Jugaad Time. Both will soon be featured on the Furtherfield web site.

Join us in Edinburgh at the first DAOWO ‘Blockchain & Art Knowledge Sharing Summit’ of 2019

DAOWO (Distributed Autonomous Organisations With Others) Summit UK facilitates cross-sector engagement with leading researchers and key artworld actors to discuss the current state of play and opportunities available for working with blockchain technologies in the arts. Whilst bitcoin continues to be the overarching manifestation of blockchain technology in the public eye, artists and designers have been using the technology to explore new representations of social and cultural economies, and to redesign the art world as we see it today.

This summit will focus on potential impacts, technical affordances and opportunities for developing new blockchain technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

Programme

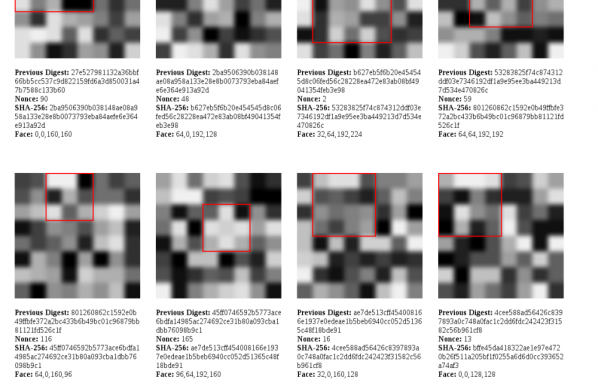

Although the term ‘blockchain’ has trickled downstream into the public domain, the principles behind the technology remain mysterious to many. Embodied within physical assemblages or social interventions that mine, hash and seal the evidence of human practices, creatives have provided important ‘coordinates’ in the form of artworks that help us to unpick the implications of the technology and the extent to which it re-configures power structures.

Hosted by Prof Chris Speed and Mark Daniels with panellists:

Pip Thornton – The Value of Words in an Age of Linguistic Capitalism

Bettina Nissen & Ailie Rutherford – Designing feminist cryptocurrency for Govanhill

Evan Morgan – GeoPact

Jonathan Rankin – OxChain, Pizza Block

Larissa Pschetz – Karma Kettles

Contributors include:

Ruth Catlow, Furtherfield and DECAL

Mark Daniels, New Media Scotland

Clive Gillman, Creative Scotland

Marianne Magnin, Arteïa

Prof Chris Speed, Design Informatics, University of Edinburgh

Ben Vickers, Serpentine Galleries

Through two UK summits, the DAOWO programme is forging a transnational network of arts and blockchain cooperation between cross-sector stakeholders, ensuring new ecologies for the arts can emerge and thrive.

DAOWO Summit UK is a DECAL initiative – co-produced by Furtherfield and Serpentine Galleries in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London. This event is realised in partnership with the Department of Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh and New Media Scotland.

OxChain is a major EPSRC research project which explores how Blockchain technologies can be used to reshape value in the context of international development and the work of Oxfam, involving the Universities of Edinburgh, Northumbria and Lancaster.

When I first heard about MoneyLab, it was back in 2013 or the beginning of 2014, when I was doing my masters in London. A friend of mine handed a flyer to me and I was intrigued by the strange typography and the combination of bright colours. However, I didn’t quite believe that any kind of initiative could really start an alt-economy movement. Not that I didn’t believe in local currency or creative commons, but those gentle approaches generally seemed to lack traction, just like liberals do with voters. I naturally thought MoneyLab was one of those initiatives.

However, as Bitcoin was becoming a hype, the name popped up again; MoneyLab itself was also becoming a hype. While bitterly regretting not being able to be associated as the first wave of participants, I started to think that maybe MoneyLab might be the framework that can really push out alternative economic attempts as mainstream culture. My stance towards economic shifts was somewhat similar to that of William Gibson’s; he said in an interview with the British newspaper The Guardian, ‘What would my superpower be? Redistribution of wealth’. How did that change after reading the MoneyLab Reader 2?

Before going into the details of what blockchain technology can really do, it is crucial to understand a new “unit of value” created in modern society (Pine and Gilmore 1999). Since the most prominent piece of technology of our era is undoubtedly smartphones (with Apple being the first 1 trillion dollar publicly listed company in the US), a lot of transactions are inevitably conducted through apps and web services. The proliferation of the so-called “payments space” signifies the era of UX design, which is the third paradigm of HCI (Human-Computer Interaction), “tak[ing] into account…affect, embodiment, situated meaning, values and social issues” (Tkacz and Velasco 2018). In other words, experience has become the deciding factor of customers’ choices. With vast amounts of data generated at the back of sleek interfaces, one can precisely oversee the users’ behaviour, which then is fed back into the system.

All the payments spaces are essentially digital. This means transactions leave digital traces whether you like it or not. The idea of a cashless society exactly stems from this interest, the authorities can have better understandings of how people make money; in other words, where black money flows. Brett Scott has been pointing out the danger of a cashless society for quite some time now, I saw another variation in this book.

According to Jaya Klara Brekke, blockchain technology can make money programmable, “allow[ing] for very fine-grained (re)programming of the medium of money, from what constitutes, and how to measure, value-generating activity to the setting of parameters on the means and conditions of exchange – what is spendable, where and by whom” (Brekke 2018). The overall impression I got from the MoneyLab Reader 2 about what blockchain technology can really do is basically this. Making a currency programmable using smart contracts.

More than a couple of authors discuss how “contingency” should take place in designed currencies. Contingency is different from randomness; in fact, it could mean exactly the opposite. For example, when coins are distributed in a perfectly random manner, you have absolutely no control in the handling process. If contingency is embedded in a system, it means there are exploitable gaps, which seem to almost randomly benefit people. On the other hand, some individuals would find ways to make use of these gaps, which are considered to be legitimate. Brekke discusses how the way in which contingency is programmed into a currency will be a key for the future of finance, both in terms of experience and redistribution of wealth. Therefore, currency designers will be the next UX designers.

A number of ideas applying blockchain technology to both physical and cultural objects are mentioned in this book, from a self-maintaining forest to blockchain-based marriage. “Terra0” is the concept of an autonomous forest which can “self-harvest its own value” (Lotti 2018). Utopian views of a human-less world are prevalent, but in reality, a healthy forest requires an adequate amount of human intervention. In addition, the value of a forest cannot be determined by itself; trade routes, demand and supply, they are all drawn by human movements. For example in Japan, domestic wood resources are generally not profitable because of the expensive labour costs. Illegally cut trees without certification from Southeast Asia dominate the market, putting domestic ones in a bad position. When a forest itself is not profitable, how can it accumulate capital autonomously? Besides, the oracle problem has not been discussed at all. Unless everything is digital in the first place, there always needs to be somebody to put data onto the blockchain. In other words, the transcendence of the boundaries between the physical and the digital is not possible without human intervention. Blockchain marriage would face a similar problem; who might be the witness if circumventing the government official? Max Dovey investigates the notion of “crypto-sovereignty” while introducing an example of a real blockchain marriage where they “turn[ed] ‘proof of work’… into ‘proof of love’”(Dovey 2018). Just as the sacramental bond between spouses can be broken before Death Do Them Part, so can any cryptographic marriage unravel despite having been recorded in an immutable ledger. Whatever repercussions may exist for divorce, there are no holy or technological mechanisms to prevent it.

Platform co-ops is one of the largest topics in the book besides Universal Basic Income (UBI). A platform co-op is often a cooperatively owned version of a major platform that is supposed to be able to pay better fees to the workers. Also, a platform co-op is often associated with “lower failure rate”; 80% of them survive the first five years when only 41% of other business models do (Scholz 2018). While embracing the positive aspects of platform co-ops, I have this question stuck in my head: can you not make a platform co-op based on a new idea rather than copying existing ones?

Most platform co-ops seem that they are looking at already successful and established concepts such as rental marketplaces for rooms and ride hailing services. As a result, platform co-ops are considered more to be a social movement than an innovation. Why not just run a business right at the centre of Capitalism without being motivated by profit? Many platform co-ops challenge the main stream services such as Airbnb or Uber, however those services operate based on scale; if they have the largest user base, it will be very difficult to take them on, unless they die themselves like Myspace… Moreover, more hardware side of development can be happening around co-ops, but I don’t hear anything except for Fairphone. When can I stop using my ThinkPad with Linux on it?

After reading the MoneyLab Reader 2: Overcoming the Hype, now I’m thinking of how I should design my own currency. Of course whether cryptocurrencies are actually currencies is up to debate; depending on who you ask, Ethereum is a security (SEC), a commodity (CFTC), taxable property (IRS) or a currency (traders).

MoneyLab 2 authors overall suggest that we should not limit our imagination to fit in the existing finance systems, but think beyond. You don’t necessarily need to cling to cryptocurrencies but they may help you shape your ideal financial system.

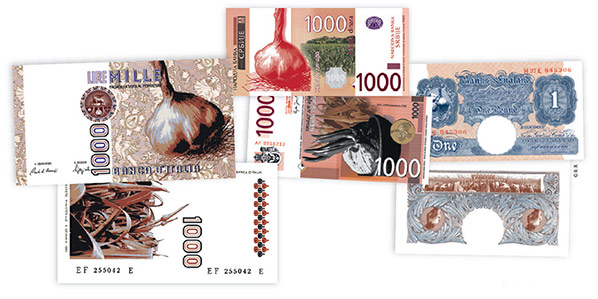

ART AFTER MONEY, MONEY AFTER ART is a workshop with Max Haiven, author of Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization.

In a world turned into a casino is it any wonder that corporate gangsters increasingly run the show? What are the prospects for a democratization of the economy when new technologies appear to further enclose us in a financialized web where every aspect of life is transformed into a digitized asset to be leveraged? Ours seems to be an age when art seems helpless in the face of rising authoritarianism, or like the plaything of the worlds speculator-plutocrats, and age when “creativity” has become the buzzword for the violent reorganization of work and urban life towards an endless “now” of competition and austerity.

And yet… we are witnessing an effervescence of imaginative struggles to challenge, hack and reinvent “the economy.” Artists, technologists and activists are working together not only to refuse the hypercapitalist paradigm but reinvent the methods and measures of cooperation towards different futures. This workshop brings together many of these protagonists and their allies for a discussion on the occasion of the publication of Max Haiven’s new book Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization.

Haiven will kick off the conversation with a short presentation of key themes in the book as they impinge upon the question of working at the intersection of “art” and new technologies (including but not limited to blockchains) to create alternative economic paradigms. The central question is, to what extent can these efforts surpass the (important) desire to redistribute wealth in a world of growing inequalities and, additionally, aim for a much more profound and radical collective reimagining of who and what is valuable.

Austin Houldsworth

Dan Edlestyn

Brett Scott

Cassie Thornton

Kate Genevieve

Emily Rosamond

Jonathan Harris

Ruth Catlow and Martin Zeilinger will chair discussions and the event is sponsored by Anglia Ruskin University

Pluto Press are happy to offer a Furtherfield discount on the book. Add Art After Money to the cart and use the discount code ART15 to get the book at £15.

What happens to the hole when the cheese is gone?

Bertolt Brecht

Transient Hole (Variations) is a hybrid curatorial project and symposium by Viennese artist and curator Alexander Felch. The project`s title refers to a concept for a media artwork, that cannot, properly speaking, be materialized for it deals with a moving void – a transient hole.

Across the floor of a white, three-dimensional room a little black hole is constantly and randomly moving. The hole is simultaneously there and not there. It is a portal to nowhere. But is it really? Might it not lead to transcendence, to another reality, or perhaps our reality can only be understood through this liminal presence of nothingness?

The participants are invited to provide their own interpretation for this problem and develop means to represent it, whether through art or science, to display processes that cannot be depicted in reality. The aim of the project is obviously not to find a solution to this existential paradox but to bring about a reflection on the topic from a myriad of disciplines and different perspectives, which explore the limits of representation. The various responses to the THR problematic will be gathered in a collected volume that is in itself a reflection on the boundary between art and science, reality and fantasy.

The project appears – just like the transient hole – in different cities popping up in various forms and is accompanied by lectures, talks and (sound-) performances.

Contributions by:

Atzgerei Productions, Arnold Berger, Ryan Mc Donagh, Sophie Dvorak, Alexander Felch / Aisek Ifraimov, Mariana Ferreira / Dayjon Edwards, Christoph Höschele, Hrvoje Hirsl, Harald Hund, Sandy Leong, Stefan Lutschinger, Nicholas Moloney, Anja Nowak, Jaysha Obispo, Shinji Toya, Jeroen van Amelsvoort, Anna Vasof, Stefan Voglsinger, Jan Vormann, Yilin Wang, David Wauters, Hui Ye.

Featuring concepts developed by students of Middlesex University London – BA Digital Media and BA Media and Cultural Studies

Monday 12 November – Friday 16 November 2018

Middlesex University

FREE

Saturday 17 November 2018, 11:00 – 16:00

Furtherfield Gallery

FREE

13:00

Opening

14:30

Introduction and Guided Tour

Alexander Felch “Transient Hole Research – Instationarity as an artistic concept / a scientific particularity”

Saturday 17 November 2018, 16:00 – 21:00

Furtherfield Commons

FREE

16:00

Limehouse Hole Atlas Datathon

Navino Evans and Sean McBride (http://histropedia.com/)

18:00

Sound Performances

Karl Salzmann (A) is a sound & visual artist, curator and researcher currently based in Vienna / Austria. Within process-oriented and experimental setups, he develops and presents works that study the materiality of sound and its social, cultural and metaphorical levels of meaning. His artistic activities mainly concern the interaction between sound and visual arts and often relate to works and topics of (sound) art history.

http://www.karlsalzmann.com/

T_A-Z (Paul Gründorfer) (A) is using process-related setups to explore sonic worlds and to realise site specific interventions, developing real time audio systems, that act autonomous or in reference to the spatial constellation. While considering the encounters between analog and digital, structured or improvised elements, he is focusing on the abstract occurrence of sound and its physical impact.

Electronic circuits are interconnected to cause semi-natural entities, autonomous organisms. Voice and articulation are generated through loops in feedback networks. Onomatopoeia.

His artistic activities examine variable connections between transmitter-receiver networks, which function as a conceptual framework for experimentation with sound and transmission of information.

http://tricx.net/

Monsterfrau Lena Wicke Aengenheyster (A/D) – MONSTERFRAU PJ (Performance Jockey) – Part III of the performance serial MONSTERFRAU The voices’ bodies: MONSTERFRAU triggers, mixes and morphes dance music rythms, samples and sounds with her movement. STAATSAFFAIRE: Production of and reflection through artistic projects in music and performance art. Beyond that it is the common optimisation of production environments and network.

http://www.staatsaffaire.com/

–

Visuals:

Simon Sarginson (live coding) (UK)

London edition curated by Alexander Felch + Stefan Lutschinger

Realised in cooperation with Cybersalon, Middlesex University London and the Austrian Cultural Forum London – with kind support by the Federal Chancellery Of Austria.

–

www.facebook.com/transienthole/

www.mdx.ac.uk

www.cybersalon.org

www.furtherfield.org

DOWNLOAD CURATORIAL STATEMENT

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

Feature image: Jeremy Hutchison, Movables, 2017. Photo courtesy of the artist.

We live in a time of stark and often violent paradoxes: the increasing liberalisation of social values in some parts of the world compared to increasing fundamentalism in others; the wealth of scientific discovery and technological advances in contrast to climate denialism, “post-factual” and conspiracy-driven politics; freedom of movement for goods and finance while individual movement is ever more constricted and subject to law; a drive towards agency, legibility and transparency of process while automation, computerisation and digitisation, render more of the world opaque and remote. At every level, mass movement of peoples and the rise of planetary-scale computation is changing the way we think and understand questions of geography, politics, and national identity.

These ever-increasing contradictions are seen most acutely at the border. Not merely the border between physical zones and between nation states, with their differing legal jurisdictions and requirements for entry and residency, but also the border between the physical and digital, when we apparently – but perhaps misleadingly and certainly temporarily – cross over into a different zone of possibility and expression.

This contradiction is also clear in the balkanisation of newly independent and fragmenting states, and in the rising current of nationalism across Europe, which seems to run in parallel to, and might even be accelerated by, digital connectivity. Some of the most outwardly regressive powers themselves employ what Kremlin theorist Vladislav Surkov has called “non-linear strategy”: a strategy of obfuscation and deliberate contradiction clearly indebted to the convolutions and confusions of the digital terrain – and of art. As ever more varied expressions of individual identity are encouraged, revealed, made possible and validated by online engagement, so at the same time a desperate rearguard action is being fought to codify and restrain those identities – online and off. These new emergent identities are, inevitably and by necessity, transient and contingent, slippery and subject to change and redefinition.

The artists featured in Transnationalisms address the effect of these pressures on our bodies, our environment, and our political practices. They register shifts in geography as disturbances in the blood and the electromagnetic spectrum. They draw new maps and propose new hybrid forms of expression and identity. In this exhibition Transnationalisms acknowledges and even celebrates the contradictions of the present moment, while insisting on the transformative possibilities of digital tools and networks on historical forms of nationalism, citizenship, and human rights. While the nation state is not about to disappear, it is already pierced and entangled with other, radically different forms. Alternative models and protocols of citizenship, identity, and nationhood are being prototyped and distributed online and through new technologies. Transnationalisms examines the ways in which these new forms are brought into the physical world and used to disrupt and enfold existing systems. It does not assume the passing of old regimes, but proclaims the inevitability of new ones, and strives to make them legible, comprehensible, and accessible.

Raphael Fabre CNI, 2017

On April 7th, 2017, Raphael Fabre submitted a request for a French ID card. All of his papers were deemed to be legal and authentic and so the demand was accepted and a new national ID card was issued. In fact, the photo submitted to accompany this request was created on a computer, from a 3D model, using several different pieces of software and special effects techniques developed for movies and video games. Just as our relationship with governments and other forms of authority is increasingly based on digital information, so the image on the ID is entirely virtual. The artist’s self-portrait suggests the way in which citizens can construct their own identities, even in an age of powerful and often dehumanising technologies.

Jeremy Hutchison Movables, 2017

The starting point for this work was a found photograph, taken by police at a border point somewhere in the Balkans. It showed the inside of a Mercedes, the headrests torn open to reveal a person hiding inside each seat. This photograph testifies to a reality where human bodies attempt to disguise themselves as inanimate objects, simply to acquire the same freedom of movement as consumer goods. Movables translates this absurdity into a series of photo collages, combining elements of high-end fashion and car adverts, enacting an anthropomorphic fusion between the male form and the consumer product. The results are disquieting yet familiar, since they appropriate a visual language that saturates our everyday urban surroundings, highlighting the connections between transnational freedoms and limitations, and international trade.

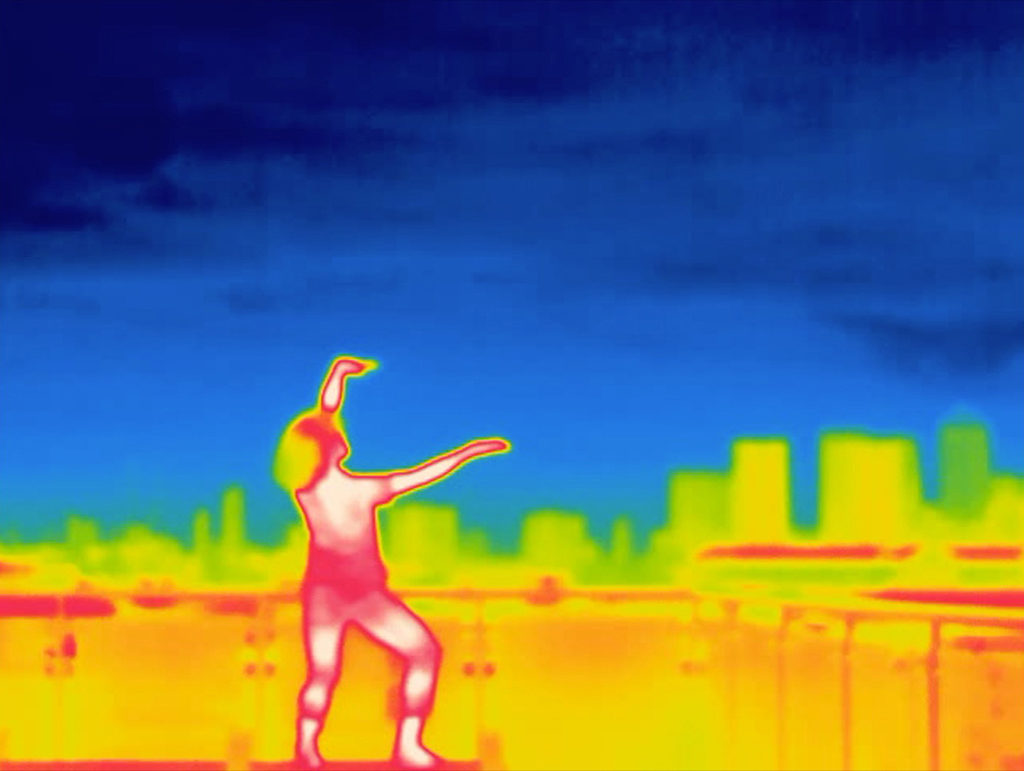

They Are Here

We Help Each Other Grow, 2017

Thiru Seelan dances on an East London rooftop, looking out towards the skyline of the Canary Wharf financial district. His movements are inspired by the dance form Bharatanatyam, traditionally only performed by women and taught to Thiru in secret by his younger sister. Thiru is a Tamil refugee and when he arrived in the UK in 2010, following six months of detention in Sri Lanka during which he was tortured for his political affiliations, Canary Wharf was his first home. His movement is recorded by a heat sensitive camera more conventionally used as surveillance technology and deployed to monitor borders and crossing points, where bodies are recorded and captured through their thermal signature. The song ‘We’ve helped each other grow’, composed and performed by London based Mx World, was chosen with Thiru to soundtrack the performance. Mx is a prefix that does not indicate gender. In the UK, it can be used on many official documents – including passports. The repeated refrain, ‘We’ve helped each other grow’ suggests a communal vision for self and social development.

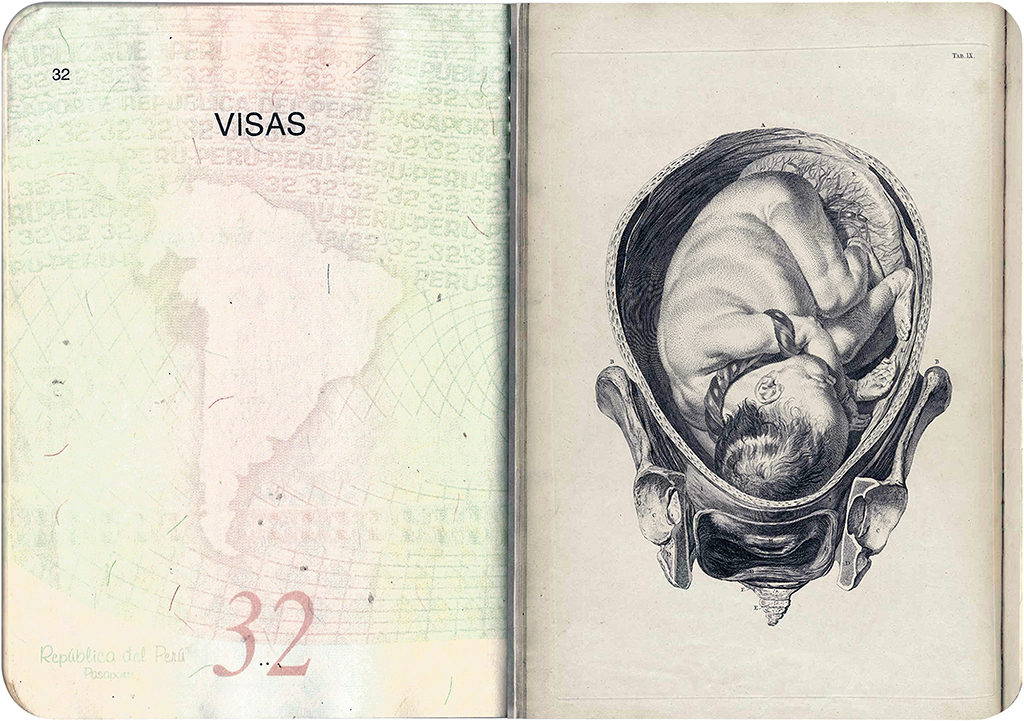

Daniela Ortiz

Jus Sanguinis, 2016

Jus sanguinis, meaning ‘the right of the blood’, is one of the main ways in which people acquire citizenship: from the blood of their parents. Daniela Ortiz is an artist of Peruvian descent living in Spain, where only babies with Spanish blood are recognized as subjects with the right to the nationality at the moment of the birth. As a result, her child would not have access to Spanish nationality. In this performance, undertaken when Ortiz was four months pregnant, she receives a blood transfusion from a Spanish citizen, directly challenging the racist and nationalist regime of citizenship which would classify her Spanish-born child as an immigrant.

The Critical Engineering Working Group (Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev)

VPN, 2018

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) have come into increasing demand in recent years, providing route encryption through hostile networks. In China, Vietnam, Turkey and Pakistan they also serve to mitigate government censorship, so that foreign sites otherwise blocked by state firewalls are made available to VPN users (Twitter, Facebook, Wikipedia, activist sites and digital libraries being the most common).

Vending Private Network takes the form of a condom vending machine, such as those typically seen in toilets. Equipped with mechanical buttons, a coin-slot and USB ports, it offers 4 VPN routes, each adorned with an animated graphic depicting a fantasy destination. Audiences are invited to insert a USB stick into the slot, and a coin into the machine, then to select a VPN destination by pressing a mechanical button, a unique VPN configuration file is then written onto their USB stick. Special instructions (in the form of a README.txt) will also be copied to the USB stick that explain how to use the VPN in a special ‘sheathed’ mode that evades detection methods (namely Deep Packet Inspection, or DPI) used by corporations and state-controlled infrastructure administrators. This is the only means known to work against state controlled firewalls, for instance and requires an extra install of freely available, open source software and leverage economic and cultural privilege to benefit those not included. With each VPN config generated, another is covertly shipped to contacts in Turkey, China, Vietnam and Iran (and other countries to be confirmed).

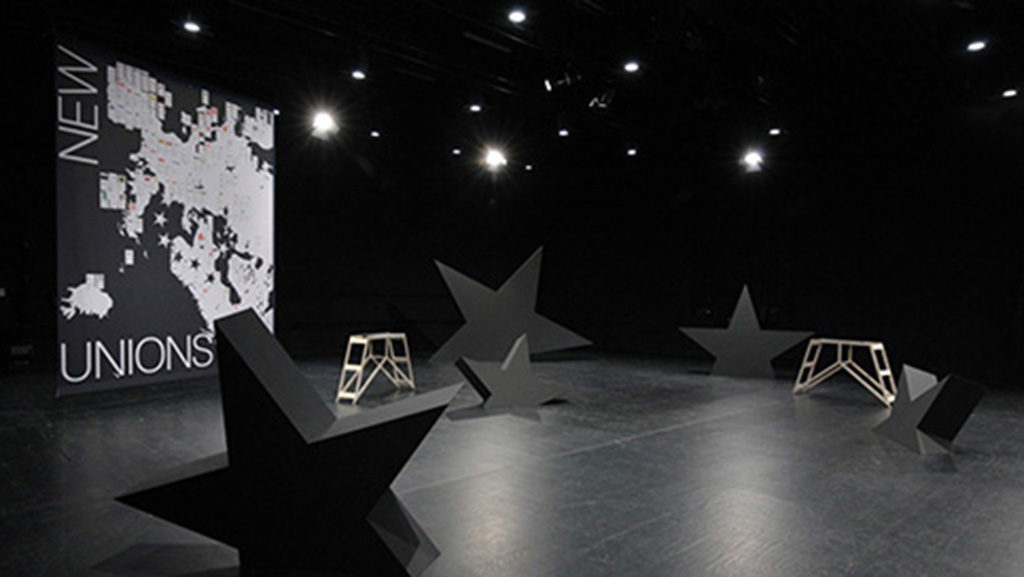

Jonas Staal New Unions, 2016

Jonas Staal’s New Unions is an artistic campaign supporting progressive, emancipatory, and autonomist movements all over Europe, and proposing the creation of a “transdemocratic union” which is not limited by the boundaries of nation states. The New Unions map illustrates the recent, massive rise in social movements and new political parties which are creating new models of political assembly and decision making while challenging traditional national and institutional structures. From the civil initiative in Iceland to collectively rewrite the constitution after the economic crash, to regional independence movements and pan-European solidarity groups, these emerging political experiments propose new forms of transdemocratic practices. This map is the first in a series which is continuously updated to reflect the evolving geography of transdemocracy.

The Critical Engineering Working Group is a collaboration between Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev. Their manifesto begins: “The Critical Engineer considers Engineering to be the most transformative language of our time, shaping the way we move, communicate and think. It is the work of the Critical Engineer to study and exploit this language, exposing its influence.”

criticalengineering.org

Raphaël Fabre works on the interference of fictions and narrative storytelling in the real world, using techniques ranging from digital 3D technologies to set decoration. Born in 1989, he lives and works in Paris.

raphaelfabre.com

Jeremy Hutchison works with situational performance. Operating in sites of production and consumption, he often collaborates with factory employees, migrant labourers, online workers and jobseekers to examine the structures that limit human existence. How are unequal human relations constructed by global capital? How do consumer products function as portraits of exploitative material structures? In the process of developing these works, each context becomes a stage; a metaphor for the production of reason. To some extent, his projects are rehearsals for an uncertain kind of freedom. He was recently a member of the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York.

jeremyhutchison.com

Daniela Ortiz (Cusco, 1985) lives and works in Barcelona. Through her work, she generates spaces of tension in which the concepts of nationality, racialization, social class and gender are explored in order to critically understand structures of inclusion and exclusion in society. Her recent projects and research revolve around the issue of migration control, its links to colonialism, and its management by Europeanwhite states and societies. At the same time, she has produced projects about the Peruvian upper class and its exploitative relationship with domestic workers. Daniela gives talks and participates in discussions on Europe’s migration control system and its ties to coloniality in different contexts.

daniela-ortiz.com

Jonas Staal lives and works in Rotterdam (NL). He has studied monumental art in Enschede (NL) and Boston (US) and received his PhD for research on Art and Propaganda in the 21st Century from the University of Leiden (NL). His work includes interventions in public space, exhibitions, theater plays, publications and lectures, focusing on the relationship between art, democracy and propaganda. Staal is the founder of the artistic and political organization New World Summit and, together with BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht (NL), of the New World Academy.

jonasstaal.nl

They Are Here (f. 2006) is a collaborative practice steered by Helen Walker and Harun Morrison. They are currently based in London and on the River Lea. Their work can be read as a series of context specific games. The entry, invitation or participation can be as significant as the game’s conditions and structure. Through these games, they seek to create ephemeral systems and temporary, micro-communities that offer an alternate means of engaging with a situation, history or ideology. In parallel, they initiate multiyear socially engaged projects that become generative spaces for further works. They Are Here work across media and types of site, particularly civic spaces.

theyarehere.net

James Bridle is an artist and writer working across technologies and disciplines. His artworks and installations have been exhibited in Europe, North and South America, Asia and Australia, and have been viewed by hundreds of thousands of visitors online. He has been commissioned by organisations including the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Barbican, Artangel, the Oslo Architecture Triennale, the Istanbul Design Biennial, and been honoured by Ars Electronica, the Japan Media Arts Festival, and the Design Museum, London. His writing on literature, culture and networks has appeared in magazines and newspapers including Frieze, Wired, Domus, Cabinet, the Atlantic, the New Statesman, and many others, in print and online, and he has written a regular column for the Observer. “New Dark Age”, his book about technology, knowledge, and the end of the future, is forthcoming from Verso (UK & US) in 2018. He lectures regularly on radio, at conferences, universities, and other events, including SXSW, Lift, the Global Art Forum, Re:Publica and TED. He was been a resident at Lighthouse, Brighton, the White Building, London, and Eyebeam, New York, and an Adjunct Professor on the Interactive Telecommunications Programme at New York University.

jamesbridle.com

Furtherfield is an internationally-renowned digital arts organisation hosting exhibitions, workshops and debate for over 20 years. We collaborate locally and globally with artists, academics, organisations and the public to explore digital culture and the changing world we live in. From our unique venues in Finsbury Park we offer a range of ways for everyone to get hands on with emerging technologies and ideas about contemporary society. Our aim is to make critical digital citizens of us all. We can make our own world.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Transnationalisms is realised in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY).

The Alternative UK write about Transnationalisms: We live in an age of transnationalisms. At Furtherfield, artists test all the borders

Join Stacco Troncoso & Ann Marie Utratel (Commons Transition) and Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) to play Commonspoly – the resource-access game where we win by working as a community.

Commonspoly is a hack and a critique of the game Monopoly. Players aim first to re-municipalize private goods and then turn them into a Commons – you’ll learn why this is the best strategy while playing the game.

Rather than compete against each other, players must overcome their conditioning and ‘rational, self-interest’ to instead maximize cooperative behaviours and create a commons-oriented locality. Who wins? Everyone in the community! Unless the speculators take over…which we must fight at all costs. United we stand!

This event at Design Museum in partnership with Furtherfield forms part of Convivial Tools, a programme of talks, debates and workshops exploring new strategies for a more cooperative society, based on the thinking of the late philosopher Ivan Illich.

Stacco Troncoso is the advocacy coordinator for Commons Transition and the P2P Foundation, and a co-founder of the Guerrilla Translation collective. He is the designer and content editor for CommonsTransition.org, the P2P Foundation blog and the Commons Strategies Group website.

Ann Marie Utratel is part of the Commons Transition team, and is a co-founder of the Guerrilla Translation collective. Her work helps connect a widening network of people involved in forward-thinking communities including the Commons and P2P movement, collaborative economy, open licensing, open culture, open cooperativism, and beyond.

Ruth Catlow, artist, curator, and co-founder and co-director of Furtherfield, is a recovering web-utopian and has worked since the mid-90s with network practices in arts, technology and social change.

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

Would you like to monetise your social relations? Learn from hostile designs? Take part in (unwitting) data extractions in exchange for public services?

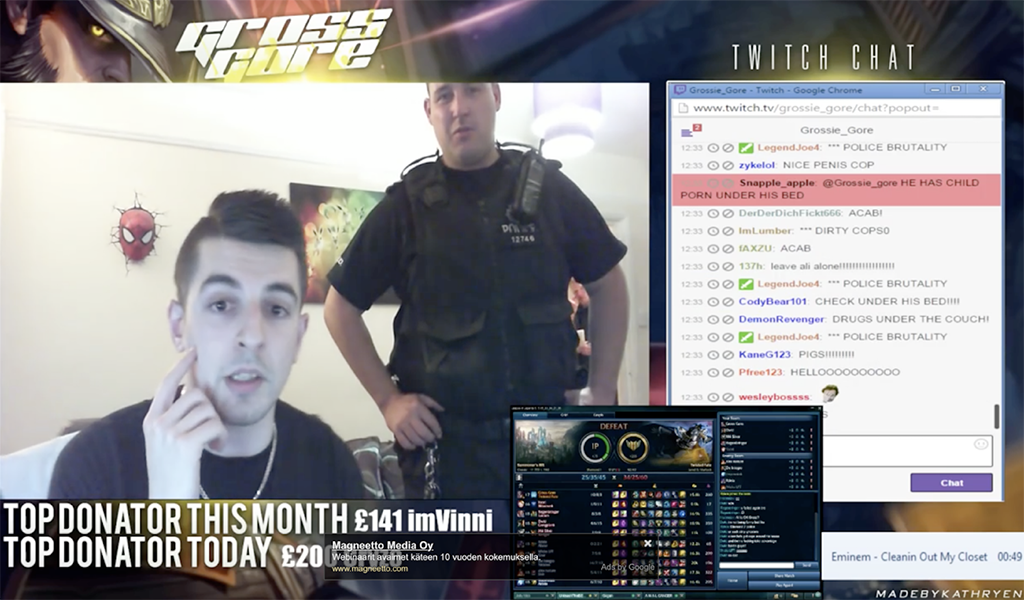

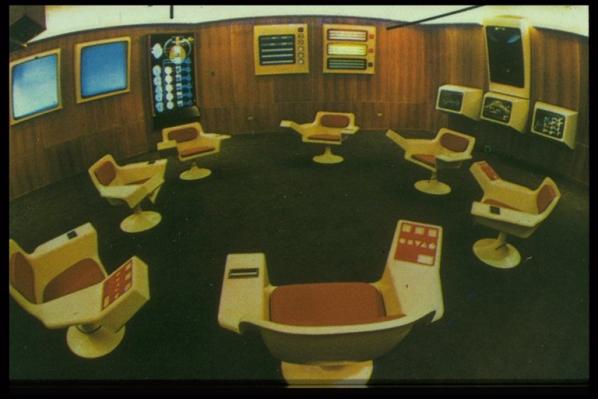

Examining the way that the boundaries between ‘play’ and ‘labour’ have become increasingly blurred, this summer, Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival, will transform Furtherfield Gallery into an immersive environment comprising a series of games. Offering glimpses into the gamification of all forms of life, visitors are asked to test the operations of the real-world, and, in the process, experience how forms of play and labour feed mechanisms of work, pleasure, and survival.

What it means to be a worker is expanding and, over the last decade, widening strategies of surveillance and new sites of spectatorship online have forced another evolution in what can be called ‘leisure spaces’. From the self-made celebrity of the Instafamous to the live-streaming of online gamers, many of us shop, share and produce online, 24/7. In certain sectors, the seeming convergence of play and labour means work is sold as an extension of our personalities and, as work continues to evolve and adapt to online cultures, where labour occurs, what is viewed as a product, and even, our sense of self, begins to change.

Today, workers are asked to expand their own skills and build self-made networks to develop new avenues of work, pleasure and survival. As they do, emerging forms of industry combine the techniques and tools of game theory, psychology and data science to bring marketing, economics and interaction design to bear on the most personal of our technologies – our smartphones and our social media networks. Profiling personalities through social media use, using metrics to quantify behaviour and conditioning actions to provide rewards, have become new norms online. As a result, much of public life can be seen as part of a process of ‘capturing play in pursuit of work’.

Although these realities affect many, very little time is currently given over to thinking about the many questions that arise from the blurring between work and play in an age of increasingly data-driven technologies: How are forms of ‘playbour’ impacting our health and well-being? What forms of resistance could and should communities do in response?

To gain a deeper understanding of the answers to these questions, we worked with artists, designers, activists, sociologists and researchers in a three-day co-creation research lab in May 2018. The group engaged in artist-led experiments and playful scenarios, conducting research with fellow participants acting as ‘workers’ to generate new areas of knowledge. This exhibition in Furtherfield Gallery is the result of this collective labour and each game simulates an experience of how techniques of gamification, automation and surveillance are applied to the everyday in the (not yet complete) capture of all forms of existence into wider systems of work.

In addition to a performance by Steven Ounanian during the Private View, the ‘games’ that comprise this exhibition are:

Lab session leads and participants: Dani Admiss, Kevin Biderman, Marija Bozinovska Jones, Ruth Catlow, Maria Dada, Robert Gallager, Beryl Graham, Miranda Hall, Arjun Harrison Mann, Maz Hemming, Sanela Jahic, Annelise Keestra, Steven Levon Ounanian, Manu Luksch, Itai Palti, Andrej Primozic, Michael Straeubig, Cassie Thornton, Cecilia Wee, Jamie Woodcock.

Curated by Dani Admiss.

Concept development Dani Admiss and Cecilia Wee.

Mask Making for Children

Sunday 22 July and 12 August 2018, 11:00 – 16:30

Furtherfield Gallery

FREE

Dani Admiss

When I was 16 I was in a band. I couldn’t sing that well so I used to write lyrics (about vampires) and put them into Babelfish to translate them into French thinking it made me sound automatically cooler.

@daniadmiss

Kevin Biderman

First met you in a dial up world; green block letters on a black screen. Later we traversed through neon colours, pixelated images and imperfect designs. I always knew you were an army brat born out of apocalyptic fears but I never thought you’d turn your back on the counter-culture who raised you. Maybe there will be a third act…

@act3

Marija Bozinovska Jones

The internet has concurrently enhanced and diminished life, yet I appear no longer able to recall life before it. Adding to Jameson’s quote: it is easier to imagine the end of the world, than the end of TECHNOcapitalism.

Ruth Catlow

I am a recovering Web Utopian – decentralised infrastructure does not, it turns out, lead automatically to decentralised power. However i am still most excited by art that happens in wild flows, through collaboration on open channels, rather than being owned, certified and traded like dead matter. I am Ruth and I am one of the voices and pairs of eyes.

@furtherfield

Maria Dada

I regularly translate whole books from German to English using Google Translate. I then take the transcripts and print them using lulu.com. I take pride in the design of the covers for each book. Not all of them are unreadable but most of them just sit on my shelf untouched.

@mariadada

Beryl Graham

I confess:

To buying a mobile phone so that I could text my sweetie.

To being mildly obsessed with weather apps that work best in the North.

To using online dating 15 years ago. The respectable Guardian rather than Tindr of course – hey I’m not an animal.

@berylgraham

Miranda Hall

After school, my friend and I would take screenshots of penises on ChatRoulette then save them in a desktop folder on the family computer called ‘cool fish’

@Miranda__Hall

Arjun Harrison-mann

For Much Longer than I Would Care to Admit, Every Since I Got Msn at the Age of 12, My Msn Profile Picture Was (and I Just Checked, Still Is), a Photoshopped Collage of Michael Jordan.

@arjun_harrisonmann

Maz Hemming

When I was 11, lying about my age to sign up on msn chat to chat about neopets, I ended up as one of the chatroom moderators. Which sometimes ended up with me leaving the window open to idle overnight (or the room would close). On the bonus side when my parents ended up with a bill at the end of the month of £200 (which I didn’t know would happen) we did get broadband. Much cheaper.

@MazHem_

Robert Gallagher

The unread emails in my inbox currently outnumber my Twitter followers by a factor of 47.7461024499 to 1.

@r_gealga

Sanela Jahić

Once my inbox got flooded with promotions of an online store. So my boyfriend and I composed a simple bot, which took random quotes from our sci-fi eBooks collection and posted them as customer reviews on their product pages.

Annelise Keestra

Until more recently than I would admit, I genuinely didn’t think there was any correlation between the file size of a download and data use. As if, there were two kinds of “GB”. Please don’t judge me.

@aut0mne

Steven Levon Ounanian

I think the internet loves me, but just doesn’t know how to show it.

@levontron

Manu Luksch

Our dream rewired. Our powers of prediction grow with every new circuit crammed in. Leap into tomorrow – one trillion calculations a second. And it grows more powerful, becomes smaller. Smart, mobile, personal. Today – in our pockets. Tomorrow – woven into our bodies. Create and share, everything, everywhere. Life in the cloud… with a chance of blue skies. Our time is a time of total connection. Distance is zero. The future is transparent. To be, is to be connected – the network seeks out everyone.” (Dreams Rewired; 2015 – my latest feature film about our hopes and fears of being hyper-connected).

@ManuLuksch

Itai Palti

I started visiting an architecture news forum as a teenager, excited about updates on local building projects. I still visit regularly for the updates, but also make sure to check on an exceptionally cringeworthy, decades-long feud between a couple of regular posters. I think they’d really miss each other if it all stopped.

@ipalti

Joana Pestana

Back in 1999, frustrated, I nurtured no love for my iMacG3 as I had to bare with 1-song-download-per-week for not having Napster.

@joanampestana

Michael Straeubig

Before social networks and Reddit, newsgroups were the places for online discussions. Catering to my interests was comp.ai.philosphy, a group notorious for debates going haywire.

Once I had a very heated discussion with someone I considered to be an immature and irrational teenager. It turned out it was a professor in Artificial Intelligence.

@crcdng

Cassie Thornton

I own/owned these URLs: bizzykitty.com, temporaryartbeautyservices.biz, infinitemuseum.com, evilarchitexture.net, teachingartistunion.org, sfluxuryrealestatejewelry.org, mastercalendar.biz, debtimage.work, institutionaldreaming.com, poetsecurity.net, universityofthephoenix.com, debt2space.info, secretchakra.net, wombco.in, givemecred.com, wealthofdebt.com, strikedebtradio.org, matterinthewrongplace.info, futureunincorporated.com, feministeconomicsdepartment.com, projectherapy.org, and many more I will never remember.

@femnistecondept

Cecilia Wee

The first time I went on the internet was about 1 year after Cyberia cafe opened in central London. I somehow convinced my mum to make a detour from a shopping trip so I could go online to look at 2 websites. Everyone else there was working very hard.

@ceciliawee

Jamie Woodcock

I decided it would be a fun idea to learn to play League of Legends as part of the fieldwork for an esports project. However, I was so bad at it that instead I had to study before playing, reading up on guides and watching streams/videos.

@jamie_woodcock

In the lead up to Furtherfield’s Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival exhibition Maria Dada, Miranda Hall and Cassie Thornton will be taking over the social media channels on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Each micro-commission is an online space to take in different directions related ideas and themes of #playbour.

Our first week kicks off with Maria. Researcher in the fields of design and material culture, Dada’s Confessional Viral Hoax Engine brings together an interest in the infrastructures and processes used to spread misinformation online with themes of transparency, anxiety, and virtue signalling.

The second week is headed by Miranda Hall, who is a freelance journalist and research assistant at SOAS specialising in digital labour.

In the final week Cassie Thornton, artist, activist and feminist economist, will take-over Furtherfield’s social media channels. You can learn more about her here and her new project being launched on Kickstarter. Her take-over explores ideas surrounding yoga, feminist economics, class war, collective revenge, and social technology.

Dani Admiss is an independent curator and researcher working across art, design, and networked cultures. Her work employs world-building and co-creation to explore changes happening to our social, technological, and ecological, contexts. She is particularly interested in working with others to understand not yet completed transformations of body, society, and earth, into global capitalist systems. She is Founder of Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival, an art and research platform dedicated to the study of the worker in an age of data technologies. daniadmiss.com

Furtherfield is an internationally renowned arts organisation specialising in labs, exhibitions and debate for increased, diverse participation with emerging technologies. At Furtherfield Gallery and Furtherfield Lab in London’s Finsbury Park, we engage more people with digital creativity, reaching across barriers through unique collaborations with international networks of artists, researchers and partners. Through art Furtherfield seeks new imaginative responses as digital culture changes the world and the way we live.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

This project would not have been possible without the kind support of our partners.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival, is realized in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY).

This is a long read by one of the inhabitants of the Zad, about the the fortnight rollercoaster of rural riots that has just taken place to evict the liberated territory of the Zad. It’s been incredibly intense and hard to find a moment to write, but we did our best. This is simply one viewpoint, there are over 1000 people on the zone at the moment and every one of them could tell a different story. Thank you for all the friends and comrades who helped by sharing their stories, rebel spirits and lemon juice against the tear gas.

“We must bring into being the world we want to defend. These cracks where people find each other to build a beautiful future are important. This is how the zad is a model.” Naomi Klein

“What is happening at Notre-Dame-des-Landes illustrates a conflict that concerns the whole world” Raoul Vaneigem

The police helicopter hovers above, its bone rattling clattering never seems to stop. At night its long godlike finger of light penetrates our cabins and farm houses. It has been so hard to sleep this last week. Even dreaming, it seems, is a crime on the Zad. And that’s the point: these 4000 acres of autonomous territory, this zone to defend (Zad), has existed despite the state and capitalism for nearly a decade and no government can allow such a place to flourish. All territories that are inhabited by people who bridge the gap between dream and action have to be crushed before their hope begins to spread. This is why France’s biggest police operation since May 1968, at a cost of 400,000 euros a day, has been trying to evict us with its 2500 gendarmes, armoured vehicles (APCs), bulldozers, rubber bullets, drones, 200 cameras and 11,000 tear gas and stun grenades fired since the operation began at 3.20am on the morning of the 9th of April.

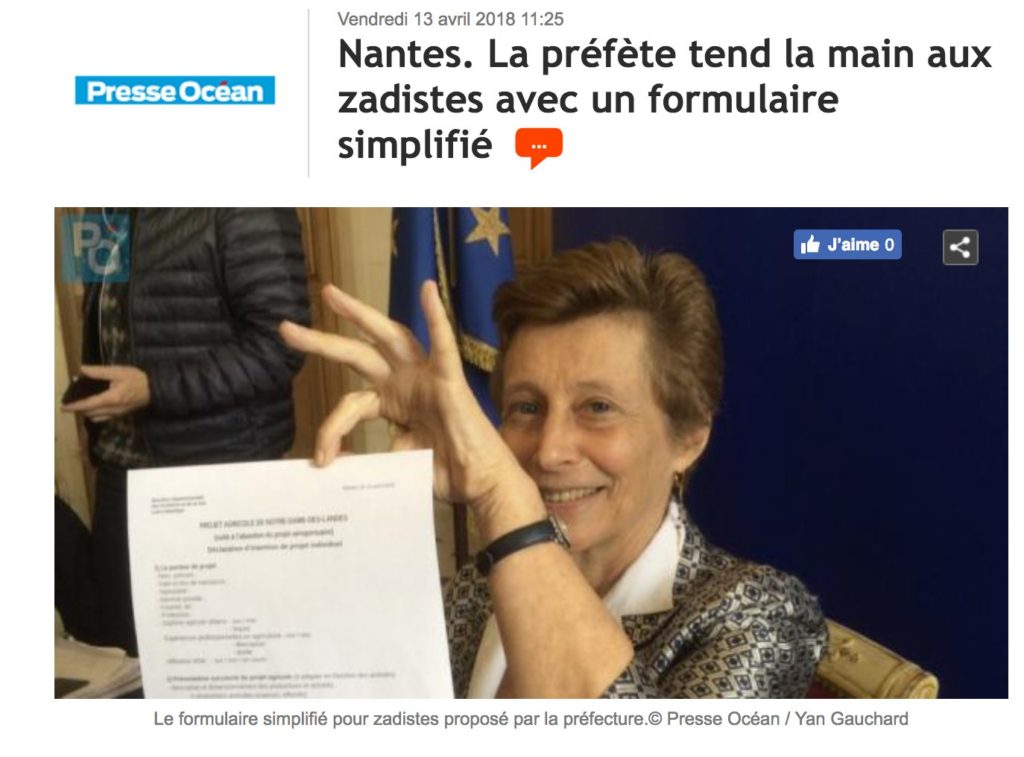

The state said that these would be “targeted evictions”, claiming that there were up to 80 ‘radical’ Zadists that would be hunted down, and that the rest, the ‘good’ Zadists, would have to legalise or face the same fate. The good zadist was a caricature of the gentle ‘neo rural farmer’ returning to the land, the bad, an ultra violent revolutionary, just there to make trouble. Of course this was a fantasy vision to feed the state’s primary strategy, to divide this diverse popular movement that has managed to defeat 3 different French governments and win France’s biggest political victory of a generation.

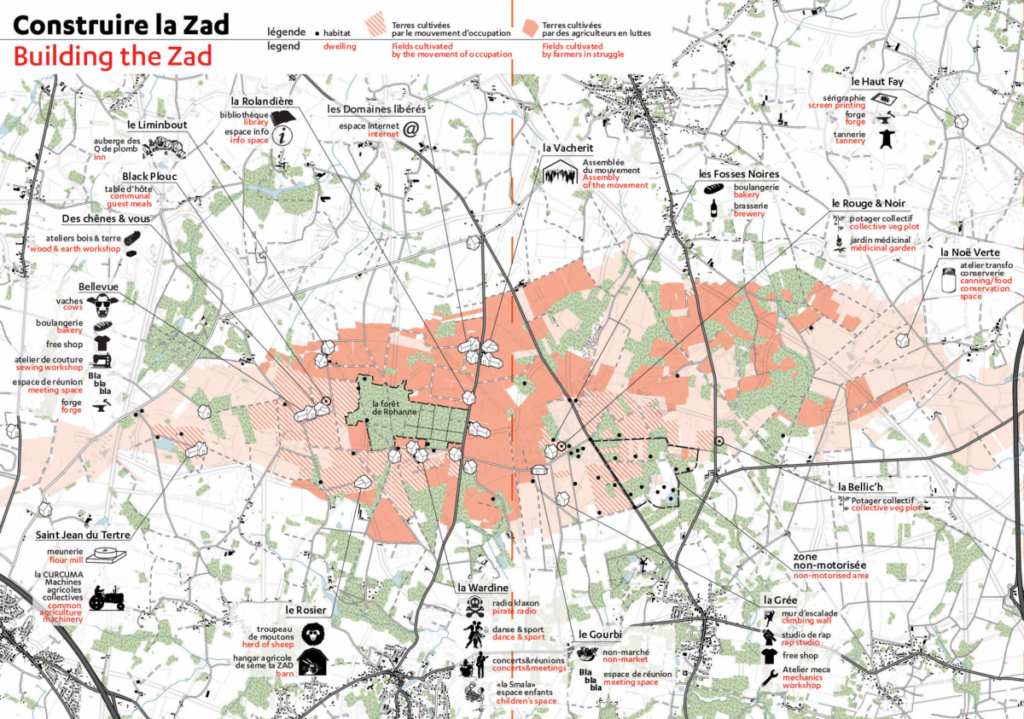

The zad was initially set up as a protest against the building of a new airport for the city of Nantes, following a letter by residents distributed during a climate camp in 2009, which invited people to squat the land and buildings: ‘because’ as they wrote ‘only an inhabited territory can be defended’. Over the years this territory earmarked for a mega infrastructure project, evolved into Europe’s largest laboratory of commoning. Before the French state started to bulldoze our homes, there were 70 different living spaces and 300 inhabitants nestled into this checkerboard landscape of forest, fields and wetlands. Alternative ways of living with each other, fellow species and the world are experimented with 24/7. From making our own bread to running a pirate radio station, planting herbal medicine gardens to making rebel camembert, a rap recording studio to a pasta production workshop, an artisanal brewery to two blacksmiths forges, a communal justice system to a library and even a full scale working lighthouse – the zad has become a new commune for the 21st century. Messy and bemusing, this beautifully imperfect utopia in resistance against an airport and its world has been supported by a radically diverse popular movement, bringing together tens of thousands of anarchists and farmers, unionists and naturalists, environmentalists and students, locals and revolutionaries of every flavour. But everything changed on the 17th of January 2018, when the French prime minister appeared on TV to cancel the airport project and in the same breath say that the zad, the ‘outlaw zone’ would be evicted and law and order returned.

I am starting to write 8 days into the attack, it’s Tuesday the 17th of April my diary tells me, but days, dates even hours of the day seem to merge into a muddled bath of adrenaline socked intensity, so hard to capture with words. We are so tired, bruised and many badly injured. Medics have counted 270 injuries so far. Lots due to the impact of rubber bullets, but most from the sharp metal and plastic shrapnel shot from the stun and concussion grenades whose explosions punctuate the spring symphony of birdsong. Similar grenades killed 21 year old ecological activist Remi Fraise during protests against an agro industrial damn in 2014.

The zad’s welcome and information centre, still dominated by a huge hand painted map of the zone, has been transformed into a field hospital. Local doctors have come in solidarity working with action medic crews, volunteer acupuncturists and healers of all sorts and the comrades ambulance is parked outside. The police have even delayed ambulances leaving the zone with injured people in them, and when its the gendarmerie that evacuates seriously injured protesters from the area sometimes they have been abandoning them in the street far from the hospital or in one case in front of a psychiatric clinic.