7 – 8.30pm – Introduced by Ruth Catlow and Janez Janša

We invite you to join us for the screening of the documentary film My Name is Janez Janša (2012) as part of Identity Trouble (on the blockchain) the second event in the DAOWO blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts. The film will be introduced by Ruth Catlow and Janez Janša, director of My Name is Janez Janša.

“The system of reference of names started to crack … This made me reflect on issues such as identity vs identification, multiplicity vs multiplication, the name as an interface between the private and the public, and the personal name as a brand.” – Janez Janša, Director of My Name is Janez Janša.

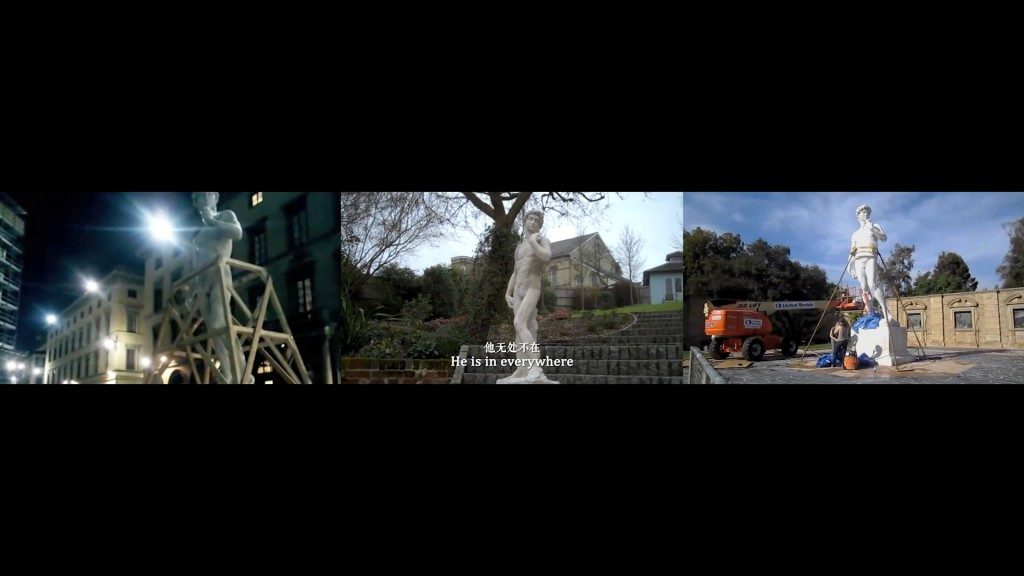

Following the second DAOWO workshop, we present this film about names, identity, and pseudonymity in a long history of academic, artistic and popular identity play for political and personal reasons. In 2007 three artists changed their names to that of Janez Janša, the then Prime Minister of Slovenia, whilst remaining ambiguous about their reasons. This documentary film reflects on the subjective and public meaning and utility of a person’s name and documents the interpretations and responses provoked by journalists, the general public and the “original” Janez Janša.

The Janez Janša® exhibition is on display at Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, Ljubljana, 18 October 2017 — 08 February 2018

The DAOWO programme is devised by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Ben Vickers (Serpentine Galleries & unMonastery) in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

It was not the cyberpunk universe you were looking for.

Our nostalgia centres were lit up with a cut from a flying car to a full screen eyeball staring across the opening scene, synchronized on the script and musical score of its 20th century precursors’ timing. From there, audiences of the Blade Runner sequel were dropped into a pale California wasteland blanketed with conglomerate agricultural biofarms, an antithesis to cyberpunk’s damp, urban hybridity. The green, utopic space beyond the city– only glimpsed at the end of the 1982 original theatrical release and removed entirely in the director’s cut– was where we started from in Blade Runner 2049, and (surprise) there’s nothing but the dystopia of the anthropocene to look forward to there either.

Times change.

The recently post-industrial, 20th century cyberpunk rebellion of bodily sensuality: the noir lighting, the baroque candelabras burning, the lingering fingers stroking out haunting piano music; these were relics now, hinted at, ghosts of a genre in its past moment. Even the endless rain characteristic of the cyberpunk genre was repeatedly replaced with snow in Blade Runner 2049. A borrowed soundtrack teasing the familiar bridge to a heroic death scene came without poetic dialogue or even a witness. Rogue replicants were not criminals, but escaping criminality. Even memories were no longer stolen in this world, but legally manufactured, a convention stripping the typical cybernetic plot of bioharvesting found in cyberpunk down to a more contemporary, bioengineered ethics of classed and raced co-humanity if ever there was one. No, this ethical failure was smoother, blended into liberal values and legal structures, more sanctioned somehow.

The 80s cyberlibertarian world of the white lone wolf, struggling for autonomy in a hybrid, post-globalized world of orientalist economic takeover, had passed by in the great data “black out” of 2020 apparently, and Denis Villeneuve didn’t care about your need for consistent genre romance. Sort of. Rather, the director brought the audience’s need for Blade Runner nostalgia in and out of the sequel like a tool, cuing our attention to wait for it, partially rewarding us with a sensory, semi-nostalgic moment, only to glitch before nostalgic completion. Again and again, it was invitation and estrangement from our own expectations. Blade Runner 2049 was a highly self-aware remix of its own postmodern references and refusals in a predetermined world.

Perhaps a hybridity across two cyberpunks of historical time and cultural change was apropos. Ridley Scott’s genre critique of the corrupt corporation had evolved since its 20th century take in the Alien franchise, expanding to consciously address our own implication in the techno-dystopian social narrative. It turns out that we are no longer universally laboring blue collar victims in the secretive horrors of impending biopolitical technocracy. Rather, we are eager and satiated participants in its isolating ubiquity; high tech consumers implicated in all of the attendant social stratification, inequality, and suffering that its warm glow of access masks and accelerates, from facilitated gentrification and casualized labor, to the toxic, extra-legal wastelands of dead electronics processing.

Disruptive innovation has predominantly benefitted the 21th century, western, science fiction audience. Our classic cyberpunk desire for the vindication of the social outlier– the androgynous Sigourney Weaver in a corporate-threatened future of full equality and bodily autonomy, or the replicant who can reclaim a subjectivity beyond his or her social paradigms and slave programming– has since been turned on its anti-establishment head. Scott’s film Covenant saw this come to fruition when the Menippean Anti-hero, Bakhtin’s rebellious, paradigm-questioning literary figure cloaked in the absurd eloquence of language, is fledged into a full sociopath. We saw this in the philosophical and intellectual character of David and his calculated experiments to replace the evolutionarily inferior human species. If Menippean satire is “a genre for serious people who see serious trouble” (Howard Weinbrot), than what is this?

By Covenant, our anti-hero no longer presented the humanistic redemption narrative of the Menippean Nexus 6 leader, Roy Batty, in the original Blade Runner. Instead, Covenant gave its inverse: a regressed society being shown the mainstream values it has come to love and endorse in a world of neoliberal anti-establishment leadership. So much for the underground resistance crouching in the street garbage. The 21st century universe of cyberpunk has been one of well-mannered disruptive innovators of the species, philosophically visionary proponents of transformative wealth models built on slave bodies, and the “technê-Zen” veneered (R. John Williams) institutionalization and naturalization of technological sociopathy. Here is a social darwinist instrumentalism for our post-human age of market-driven measures of social success and impending climate change. In this universe, androids can be humanist while humans can be androids in an inhuman system, conveying either ‘progress’ by any means necessary or a losing sense of civilizational duty. Whose side, Covenant asked of us, before its devastatingly feel-bad ending, were you hoping would win anyway?

David, it turns out, was the only anti-hero we deserved now.

Denis Villeneuve’s sequel fits surprisingly in this updated cyberpunk universe. Like Walter in Covenant, the replicant hero who becomes Joe in Blade Runner 2049 (in contrast to Roy Batty) clearly lacks the eloquent language and especially satire of the subversive, Menippean Anti-hero character. Surprisingly, we find his strain of articulate stream-of-conscious in the tech empire guru played by Jared Leto, drained of all the feeling and trickster-like ability of Roy Batty. Joe, however (like Walter), is simple and humble in his speech, seemingly able to feel but dying suggestively in silence off screen. Robbed of the poetic dialogue expected of the death scene, only a soundtrack bite nostalgic of Roy Batty’s final scene signals a death of redemption for Joe in Blade Runner 2049. Yet the unsentimentally raw, blank slate of Joe’s expression asks of his audience: What do we see through his eyes? What language could possibly be used here to convey the gravity of a moment when power so regularly denies and manipulates the language of our experiences? In this silence, we are perhaps left to only wonder what we would be feeling.

What if it had ended differently? Would Roy Batty’s eloquent speech achieve the same humanizing disjuncture today, or does it really belong now to Niander Wallace, our tech monopoly visionary of the neoliberal age, emptied of any contradiction with the smooth flow of progress rhetoric and sociopathic public morality? Niander Wallace as foil who cannot stop talking makes Joe’s uncharacteristic silence all the more uncanny. According to Jonathan Auerbach, the uncanny involves a “trespassing or boundary crossing, where inside and outside grow confused… reveal(ing) dark secrets hidden within.” Auerbach is talking about film noir here– a highly unsettling sensory genre metabolized into the late Cold War aesthetics of the Blade Runner world. But perhaps we can relate this psychic role of the filmic uncanny to other hybridities explored through expressionist media, where the formal manipulations of sight and sound once conveyed the uneasy clashing of two worlds affectively.

Is Villeneuve’s silent denial of a hero’s dialogue in a death scene, for a Blade Runner audience, purposely estranging? Does it achieve the same, disorienting “uncanny bodies” (Robert Spadoni) that silent film audiences, unaccustomed to sound in their movies, reported with the introduction of Talkies? Film scholar Shane Denson describes how post-Talkie movies of the Thirties like Frankenstein (1931), were created in a period of transition and between the old and new ontologies of silent and sound film media. Denson argues that such films, working after the initial novelty of Talkie exposition wore off, played affectively with the new hybridity of films formalist storytelling qualities. In doing so, these films drew attention to our participation in media: “sight and sound conspire(d)…to encourage the viewer’s medium sensitivity, to coalesce with the perception of a constructed monster.” And what is a sequel, after all, if not a constructed monster of narrative to become conscious of?

“Questions.”

We live in a time of the seductive post-human technologization and normalization of very inhuman institutions, public policies, and person-like entities whose social impacts are all too often screened over with ‘alternative’ narratives of language. Glitches in this flow of mainstream mediated ways of knowing can be more than anti-nostalgic; they can be disruption to the alt-fact hyperreality in the neoliberal 21st century. Are uncanny bodies of the sensorily unexpected (or, even, dissected) what we have left to successfully slow down and stutter our neoliberal ubiquity for hearing chasm-filling speech? Can such estrangements allow us the conscious relationality to once again actually hear and see how we are hearing and seeing each other?

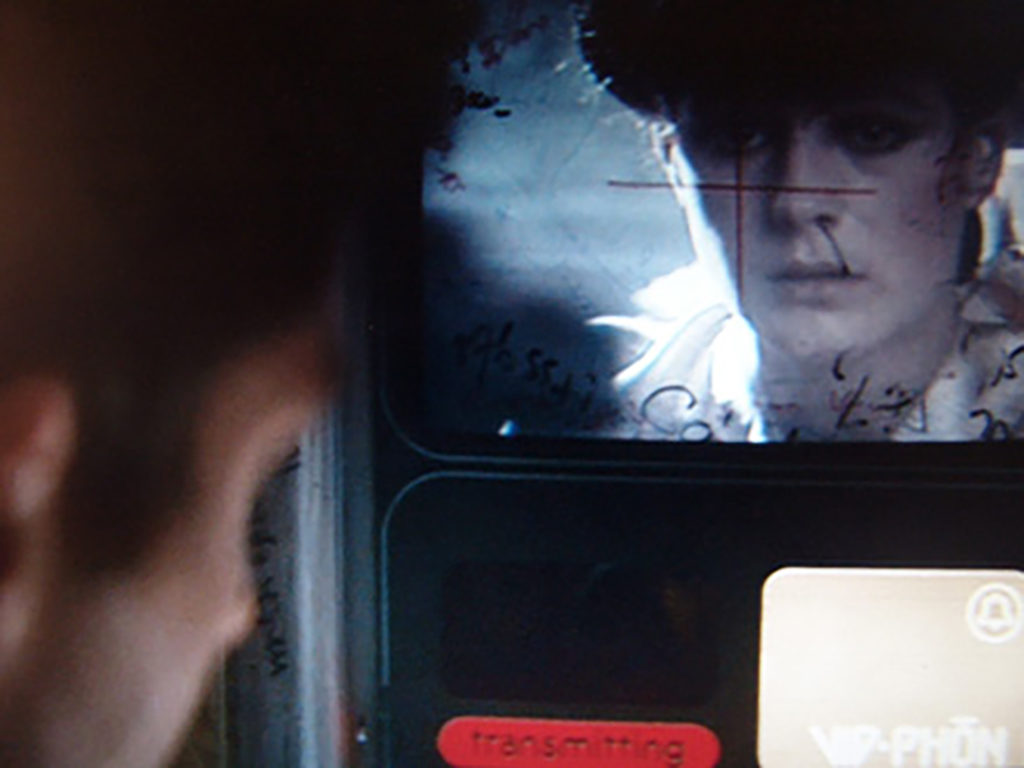

It is convenient to note here that the technological imaginary of the first Blade Runner movie refused ubiquitous surveillance. Blade Runner 2019 even refused a conception of the personal communication device so often credited with fracturing collective sociality in both sci-fi and reality. Decker, for example, calls Rachel from a public videophone in a bar. Whether human or replicant, technological worlding of the original Blade Runner insists on the communications scale of face-to-face human relationality. By the end of Blade Runner 2049 this same scale of technological imaginary in the original film returns. It is the death of one body, the replicant called “Luv”, that seems to end the limitless reach of panopticon technology that helps advance the plot.

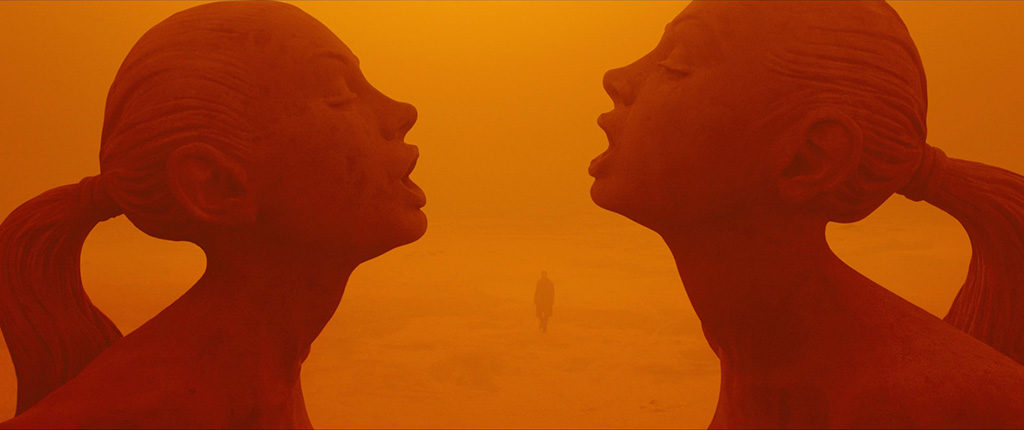

Some kinds of love can destroy. Scene from Blade Runner 2049

This act leaves the future of Blade Runner’s Earth yet again to the relations between two, individual physical bodies. With the 1% most likely afloat in the outer world colonies, we might assume this means that it’s up to Us to cross the interface of hyberbaric differences. At a time when love has become perverted with neoliberal logic– instrumental, utilitarian, stripped of its greater sense of equality or duty– it seems that Villeneuve graciously gives us an answer here, if not a fantasy to hold on to. Perhaps one consistency in the Blade Runner franchise is the argument, like that of Junot Diaz on neocolonial oppression (as if it ever ended) and the uptick of white supremacist domestic terrorism, that it is ultimately intimacy with the Other and rejection of the glorified “lone wolf” mentality that must be revolutionary: “Vulnerability is the precondition to contact.” What if being in our present moment requires the vulnerability of silence?

“Listen:”

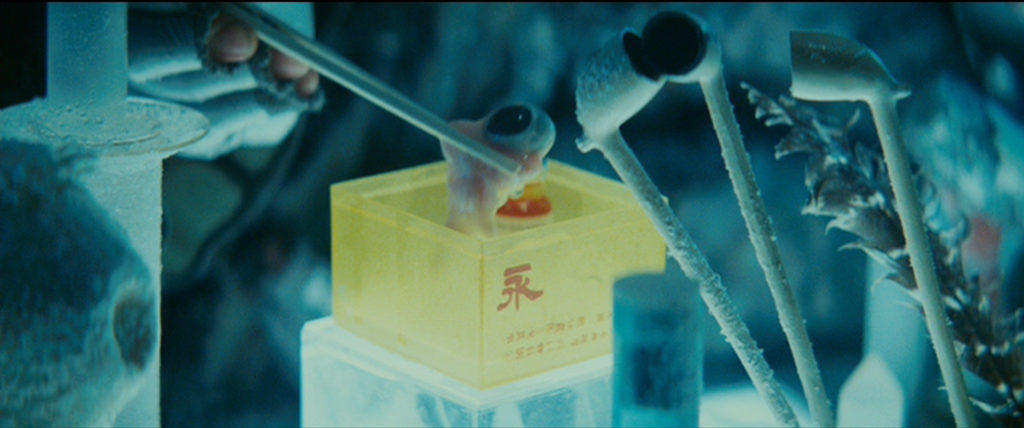

Nostalgia has come unstuck in time. In Ghosts of My Life, the late Mark Fisher wrote extensively of the threat of nostalgia in postmodern cultural production. Building on theorists Frederic Jameson and Bifo Berardi to explain the bending of new technologies to recycle comfortable and profitable cultural forms for capitalism, Fisher explains how “…the nostalgia mode subordinated technology to the task of refurbishing the old”, not of specific past styles, or periods, but forms of never-fully-present time asynchronicity. Consider it like another outdated, self-reproducing model, ever expanding all around you to stay relevant. Perhaps you can finally see its now, like a loose eye, engineered, removed from its familiar socket.

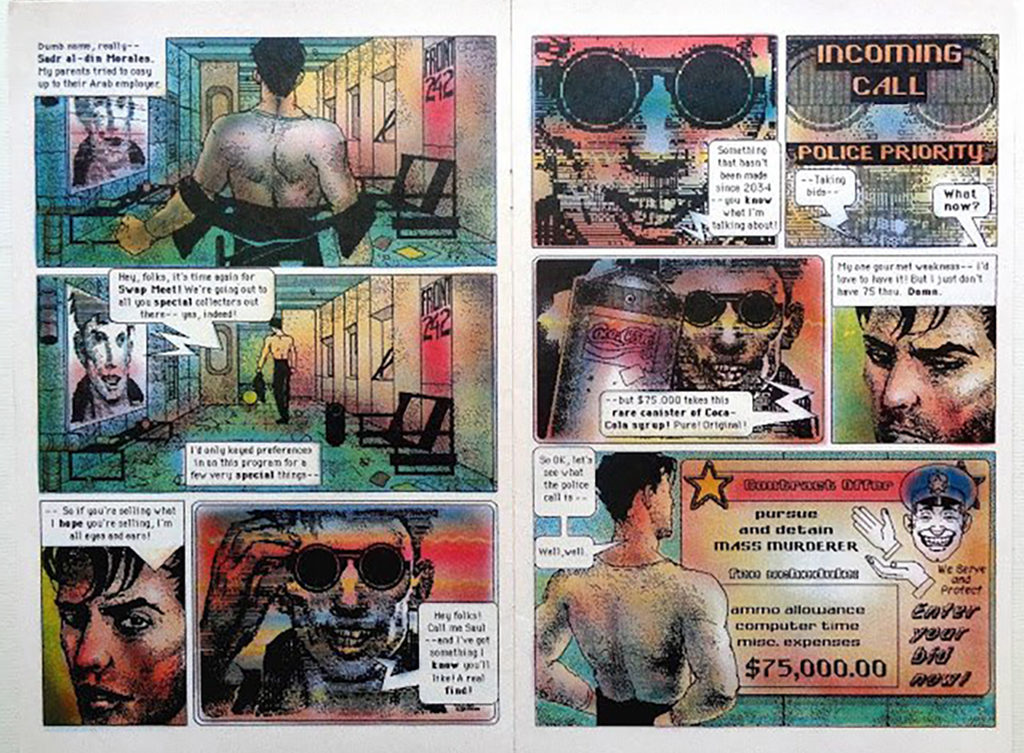

Transgressive fiction has this way of making our boundaries visible in the crossing. The reader may resist its dehumanization, suddenly queasy. Barthes once wrote about the surrealist Georges Bataille’s Story of the Eye, a modernist novel from the early mid-20th century which indeed involves a plucked eye and its “metaphorical journey” across other eye-like images. An object, he wrote, “can pass from hand to hand… or alternatively it can pass from image to image, in which case its story is that of a migration, the cycle of the avatars it passes through, far removed from its original being, down the path of a particular imagination that distorts but never drops it” (his emphasis). Barthes felt The Story of the Eye was less a novel and more like poetry. Through its avatars and crossing of sensory metaphors, the eye simultaneously “varies and endures.” Consider the following example of crossing sensory metaphors from the Blade Runner sequel: eyes, cells, tears, rain, leaking, bleeding, blinking, seizing, splashing, drowning, watching, “cells”. And what if this thing we now strangely see so differently is neither naturally born nor autonomous, but a constructed thing?

How eerie.

Eerie like the absence of “future shock” in the futuristic. According to Fisher, nostalgia mode production is an aspect of the “cultural logic of late capitalism” that “…disguise(s) the disappearance of the future” and prevents any real possibility of innovative “rupture”. Nostalgia in our entertainment helps stabilize the “cultural deficits” created under globalization, soothing the simultaneous “exhaustion and overstimulation” of instantaneous and transactional relations we can’t seem to deal with. It fills a high-speed chasm of emotion, truth, and meaning. It denies us the “uncanny” recognition of our temporal futurelessness, left teetering on neoliberalism’s precarity of resources “despite all its rhetoric of novelty and innovation…”

Let’s just be honest here: by the time the Coke commercial hologram showed up in Blade Runner 2049, it was a joke on our desire for even nostalgic product placements.

Nothing changes.

Dipping into the media art world at this borderland, theorist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl writes in “A Thing Like You and Me” about the video that David Bowie put out in 1977 for “Heroes”:

He sings about a new brand of hero, just in time for the neoliberal revolution. The hero is dead—long live the hero! Yet Bowie’s hero is no longer a subject, but an object: a thing, an image, a splendid fetish (…) the clip shows Bowie singing to himself from three simultaneous angles, with layering techniques tripling his image; not only has Bowie’s hero been cloned, he has above all become an image that can be reproduced, multiplied, and copied, a riff that travels effortlessly through commercials for almost anything, a fetish that packages Bowie’s glamorous and unfazed postgender look as product. Bowie’s hero is no longer a larger-than life human being… but a shiny package endowed with posthuman beauty: an image and nothing but an image.

What are we to do when no degree of protest or declaration can make an exploited object be seen as a subject? Where is one to find anti-heroism in all of this? Let us be objects of severe agency then. Models that are perhaps transferrable, but unobtainable. One of a kind and replaceable. Constructed yet autonomous.

Perhaps then we can only view these things in suspension: the need and refusal of nostalgia as liberating human process, the uncanny increments of our cultural evolution to product and media-focused estrangement, the will to see one’s own familiar pixels blown wide open. “Digital information is … characterised by transformation, degradation, circulation,” explains Hito Steyerl in an interview in Rhizome, “but also by its surprising ability to mutate and produce unpredictable results. The glitch, the bruise of the image or sound testifies to its being worked with and working; being passed on and circulated, being matter in action.” Futureless. As futureless as staring into a present ruin, expansive but without destination, the destination without purpose.

Apropos, then, how our old and new heroes meet in that ruined casino scene, outcasts of white difference (by the future racialization of the synthetic) in an atemporal Las Vegas, framed by primordial Seven Wonder monuments to the our foundational schisms of misogyny (yes I’m also talking about me).

In this incarnated ruin of our stubbornness for cultural mythologies, I was struck by the brilliance of the fight scene, the director literally exploding our pixel expectations of 20th century nostalgia as soon as Harrison Ford makes his long-awaited appearance. The sonic build-up of Decker’s familiar piano in the distance was dissolved by the strange sound of his disembodied voice un-cueing an upcoming appearance in the scene, his visual reveal in that moment of our auditory let down, confusing: Desire misfiring. The ensuing cyberpunk clash-as-fight-scene of 20th century romantic and 21st century post-romantic dystopic characters corresponds to the casino’s hologram interface of an imagined, mid 21st century entertainment technology; all of the expected glamour and nostalgia is allowed to barely seduce us before sputtering and malfunctioning as filmic metascene. Within the plot, these post-apocalyptic hollywood holograms are also a sign of the future sentience to come in the character of Joe’s AI wife, Joi, and a warning that all technology rebels and mutates from initial human intentions, no matter how superficial the design intentions.

My interpretation of this violent casino stage scene in light of a more recent American mass shooting of an ever-expanding, historically singular, and self-containing statistic of “largest ever” is not lost on me. Neither is the choice of mid 20th century entertainers like Elvis and Monroe who notoriously performed like automatons with post-human qualities, their movements in time-space of perfect bodies turning on the master clockwork of a still-industrializing cultural machine before blowing apart, fragmenting. Their avatars echo of consumer-creator bodies in our postindustrial world of 2.0, gig labor, automated economic transactions feigning meritocracy, and a model of precarity demanding the inhuman perfection of individual responsibility for every movement which can shudder, glitch, and explode on other people all too frequently.

This failure is that of speculated, plotted, rationalized, and technologized courses whose error cannot be properly imagined, only realized and refused in the ruins of a short-sighted economic-cultural imaginary. Our looking back on dystopia hints at our present expectations only.

“Irreversability.”

“It’s difficult for someone of my generation to break free of the intellectual automatism of the dialectical happy ending”, writes Bifo Berardi about irreversability. He compares this “taboo” concept to the “silent” apocalypses of our endless growth mentality, like Fukushima, corporate disaster unaccountability, socialized scarcity adjustments, and our silence on fellow human suffering. His book, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, speculates a “process of subjectivization” for the return of solidarity to a “social body”. This is the social body being culturally reprogrammed away under our collectively isolated movements of relentless market-driven consumption and precarity (individualist and systemic, like the fascist choreography of Kracauer’s Mass Ornament, or the Las Vegas showgirl spectacle). We might consider these grinding automaton gears of consumption and precarity the logics of late-terminal capitalism for clarity, it’s refusal a glitch in our clockwork performance. What is one to do for a postmodern exit other than to shudder, to write off the page? Ultimately, Berardi’s book leaves us more with a hope for our relational redemption from neoliberal culture through “sensibility” than it does with answers.

Blade Runner 2049 may not have been the sequel people wanted, but its confrontations with its own expectations provided a little of the things we need: a vision of the finite and anthropocene, a postmodern exit to the endless technologized avatars of getting what we think we want, our profound silence of the awful price. The film’s self-aware, nostalgic ruin leaves us with a little less of the typical sequel’s fourth wall, and an identification with its lonely bodies, caught in action between clockwork cultural predictability and its refusal. These bodies may or may not have the capacity for real love, but they are vulnerable at least to a larger sense of duty that Humanism, in all its universalizing failures, really needs. In this hybrid space of ontological awareness of the facets of knowing, experience and process, Blade Runner 2049’s success was inbetween all the things it could never definitively be. We too might realize that ‘doomed to fail’ may only be our insistence on choosing from a predetermined relational binary.

A distant song floats into the scene.

…“Though nothing, nothing will keep us together…”

When I saw Blade Runner 2049, in was at one of the remaining four hundred or so drive-in movie theaters left in the United States. I went back in memory to my kindling college interest in what I study and consider Avantpop, surveying the changes, considering its meaning and meaningless in my social development as a scholar: working class, woman, white, heterosexual; accepted and refused and abused entrances. The sequel came less than thirty years later in the revolution of a world for me, but I travelled farther to get there, out to a dark semi-rural drive-in beyond the city, and a memory of popping in a VHS tape almost 20 years ago simultaneously. I time-traveled mass media ontologies. I posted an instagram picture. It was semi-romantic nostalgia for me. But I still see that there is only now to change what we’re doing. And it is terrifying.

It’s quite an ending, to just die in silence, isn’t it?

But the fourth wall was always part of this, you know.

14.00-17.30 – Workshop devised and hosted by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickerswith Ramon Amaro, Ed Fornieles Thor Karlsson & Emily Rosamond

19.00-20.30 – Screening of the documentary My Name is Janez Janša (2012) Introduced by Ruth Catlow and Janez Janša

Identity Trouble (on the blockchain) is the second event in the DAOWO blockchain laboratory and debate series for reinventing the arts.

Identity is considered one of the hardest problems in the blockchain space, as it is here that it really matters how human and machinic systems connect. With the potential to fix and potentially impinge upon the relationship between our subjective sense of self, freedom to use multiple identities and our machine-assigned identities.

These difficulties span personal, social, technical and political domains. From a global perspective, blockchains have begun to be put forward as the most efficient and secure solution for providing identification to refugees and with it, access to basic social infrastructure such as healthcare, voting, financial and legal rights and services. As steps towards both national identity and global identity systems are being accelerated, perhaps most notably in Goal 16 of the UN 20 Global Goals, as being; “By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration”.

These drives sit in tension with fears about the increasing convergence of political and commercial control through identity technologies, tensions between: name and nym; person and persona; privacy, transparency and security; and the interests of the private individual and public citizen. All of which run counter to the proclamation that “Having two identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity”.

At the first DAOWO workshop we discovered more about current developments for blockchain application within the arts. At this event we seek to further challenge and reconsider the identity question in the context of the arts-blockchain ecosystem.

This workshop will be opened with a keynote by developer Thor Karlsson who will present Authenteq, an automatic identity verification platform and discuss his company’s approach to design for “trust and transparency in communications and transactions between users”.

This will be followed by a series of provocations by theorists and arts practitioners on cultural identity jamming, dangerous bias in the datasets that inform machine learning, and decentralised reputation management.

Laying foundations for the workshop in which we will work together to develop new stories about a set of characters living in the arts. How they operate and feel differently as the impact of blockchain technologies takes effect on their personal and professional role within the artworld.

Join us to describe what will go wrong? And what might just work?

“The system of reference of names started to crack … This made me reflect on issues such as identity vs identification, multiplicity vs multiplication, the name as an interface between the private and the public, and the personal name as a brand.” – Janez Janša, Director of My name is Janez Janša

Following the second workshop of the DAOWO series we present this film about names, identity and pseudonymity in a long history of academic, artistic and popular identity play for political and personal reasons. In 2007 three artists changed their names to that of Janez Janša, the then Prime Minister of Slovenia, whilst remaining ambiguous about their reasons. This documentary film reflects on the subjective and public meaning and utility of a person’s name and documents the interpretations and responses provoked by journalists, the general public and the “original” Janez Janša.

The Janez Janša® exhibition is on display at Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, Ljubljana

18 October 2017 — 08 February 2018

Ramon Amaro

Ramon Amaro is a Lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London; Research Fellow in Digital Culture at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam; and visiting tutor at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. Ramon has worked as a former Assistant Editor for Big Data & Society (SAGE), quality design engineer for General Motors, and programmes manager for the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME). His research interests include philosophy, machine learning, and black study.

Ed Fornieles

Ed Fornieles is an artist whose works are responsive to the movement of information. Fornieles uses film, social media platforms, sculpture, installation and performance to express the interaction of family, relationships, popular memes, language and the subcultures of 21st century experience. His work operates within the logic of immersive simulations, which construct and enact alternative political and social spaces. His projects often involve cultural, social, and infrastructural production, making interventions that reconfigure the viewer’s position and sense of self.

Thor Karlsson

Thor Karlsson is the lead backend developer at Authenteq, a privacy tool and identity verification platform for online services. With over six years of professional experience in .NET and Java, Thor works in backend systems with an emphasis on clean code, testability and optimization. Thor is currently focused on implementing core backend systems used for the Authenteq ID verification and face recognition platform.

Emily Rosamond

Emily Rosamond is a Canadian artist, writer and educator. She completed her PhD in 2016, as a Commonwealth Scholar in Art at Goldsmiths, University of London. She is Lecturer in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, and Joint Programme Leader on the BA Fine Art & History of Art. She exhibits individually and with the collective School of The Event Horizon.

The DAOWO programme is devised by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Ben Vickers (Serpentine Galleries & unMonastery) in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

The word speculation is defined as ‘the forming of a theory or conjecture without firm evidence’. The act of speculating was predominantly popularised with the rise of the stock market, however, recent environmental destruction and technological advancements have prompted a rich pool of speculation about the future of our planet, our species and our connection to other facets of life. Tomorrows: Urban Fictions for Possible Futures is such an exhibition, compromised of imaginative narratives speculating the future of our cities – how they will look, how they will function and the degree by which these cities will form new types of citizens directly operating within the network of that future city. In the context of the exhibition’s content, fiction is transformed into mighty medium, utilised to share the ideas of thirty-two individual and group projects. These projects envision and share their anticipation for the future as a means of addressing socio-economic, environmental and other issues we face today with a goal to reassess of our presence on the planet.

Tomorrows was curated by Daphne Dragona and Panos Dragonas, and organised by the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens – a city experiencing continual fluctuations since the end of World War II. The location itself, Diplarios School (a place of former learning and listening), stresses the aspect of sharing and the telling of important narratives determining the shaping of the future. The exhibition begins with a didactic, yet absolutely accessible approach to understanding the notion of developing a future city. As a starting point, the exhibition borrows and advances the ideas of Doxiadis’ speculative plans of an Ecumenopolis from 1959-1974. More particularly, we must take into consideration the term ‘ekistics’ which was coined by Doxiadis in 1942 as derived from the ancient Greek noun οίκιστής, meaning a person who installs settlers in a place or creates a settlement.

In order to create the cities of the future, we need to systematically develop a science of human settlements. This science, termed Ekistics, will take into consideration the principles man takes into account when building his settlements, as well as the evolution of human settlements through history in terms of size and quality. – Doxiadis

Doxiadis was a visionary and the decision to reinstate his work within the framework of the exhibition was incredibly rewarding for visiting audiences. He anticipated that cities were to become more than global in order to accommodate an ever changing human and non-human environment – as one huge network perhaps out of the control of human capacities. Ecumenopolis is installed on large hanging panels in the first room of Tomorrows and acts as a reference point to the five themes developed: Post-Natural Environments, Shells & Co-Habitats, Networks & Infrastructures, Algorithmic Society and Beyond Anthropos. These themes resonate to the acceleration of our urban development hybridising the natural with the artificial, future network infrastructures of our habitats becoming dependent on inhuman mediation, the possibility of an omnipresent and undemocratic structure within the city through the interdependence of economy, ecology and technology, possible forms of organisation to encourage modes of co-existence within the city, and technological singularity as challenging human sovereignty within our future cities. Doxiadis work gives way to the participants who are primarily artists, architects and designers, to explore these imminent futures of our present planet’s landscape.

Coastal Domains is an on-going research project exploring the future landscaping of coastal territories in the Northeastern Mediterranea facilitated by Demetra Katsota along with 4th and 5th year students at the Department of Architecture, University of Patras. The installation Coastal Domains was made up of sixteen books, acting as case studies, secured on the wall and a ladder to reach them, encouraging brave visitors to climb and read them – a curatorial decision simultaneously inspiring participation and learning as it is explicitly reminiscent of old archival libraries. The 7th book in the series of sixteen engaged with the coast land of Kanoni and its Sea Lane on the island of Corfu, the research undertaken by Stella Andronikou and Iasonas Giannopoulos. As with each book in the series, the research was made up historically archived material, such as cartographical maps from different centuries and topographical material including the arrangement of roads and different fauna on the island thus unveiling issues of coastal development, the implications of an upsurge of tourism in the 1970s and possible environmental issues. Coastal Domains speculates and designs possible structures for the reinforcement of sustainability, devising various strategies that can protect the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea.

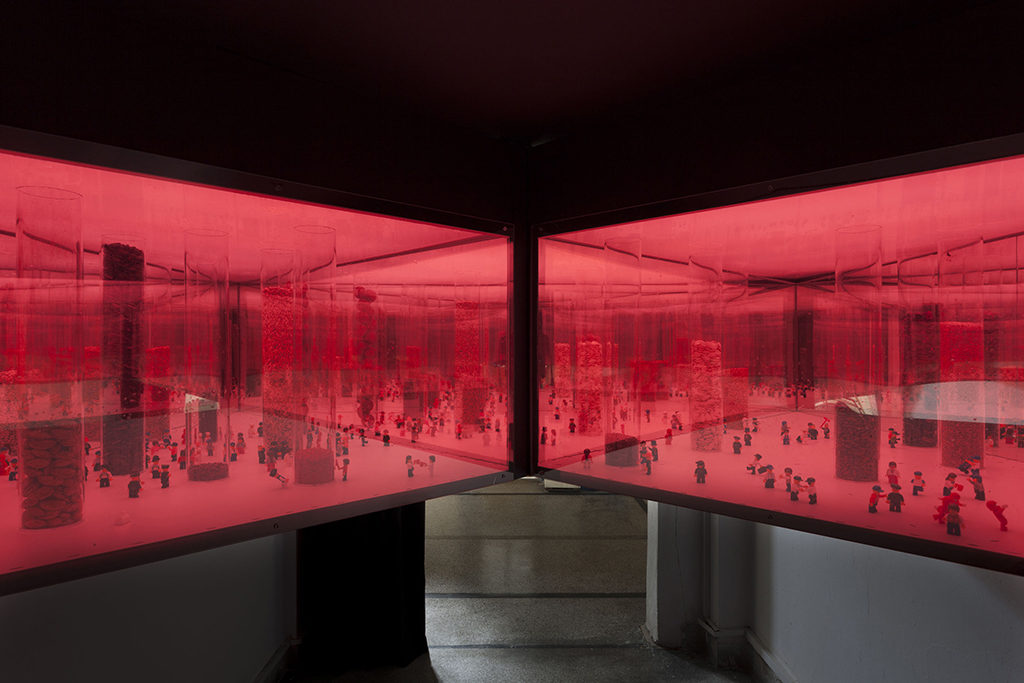

Tomorrows is particularly involved in engaging its locality of the Mediterranean, treating it as a microcosm for observing the implications of the future’s development. Silo(e)scapes by Zenovia Toloudi envisages a hybrid of a seed bank and museum for Mediterranea plant species as a tool inspiring a sharing economy. The installation of Silo(e)scapes required the audience to cradle themselves into the centre of the structure in order to experience the transparent silos-displays of the community LEGO labourers sharing their local seeds at the seedbanks. The audience suddenly find themselves in a possible future reality, all encompassing of agrarian sounds and 360 views of kaleidoscopic mirrors that trick perception of your depth of field. Almost theatrical, Silo(e)scapes is immersive and constructs a space where the audience is directly in conflict with the imminent shortage of supplies due to harmful environmental issues and increasing urban development. The audience becomes entirely physically encased in Silo(e)scapes, as a result inciting the plausibility of this future reality.

A Cave for an Unknown Traveler by Aristide Antonas introduces another form of habitable landscape for the possible future. The installation is structured like a ‘fake archaic cave’ that is buries inside it a structure as luxurious as a modern hotel room, invisible to the eye from the outside. The installed structure of the cave is complimented by a large sketchbook denoting the various features of the Cave for an Unknown Traveler. Antonas’ work brings to mind the concept of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. The infrastructure and services within Antonas’ cave can be taken in context of the prisoner’s in Plato’s cave perceiving shadows as objects when in fact they are a mere representation of their physical form grasped by our mind. In this context, Antonas’ invisible cave begins to resemble an imagined safe haven for a traveling passer-by.

The highlight of Tomorrows is undoubtedly Liam Young’s commissioned work Tomorrow’s Storeys – a two-channel video installation isolated in a dark room with modular seating. The title of the work acts with a double meaning as in storeys of a building and the stories being told through them. The content, or stories, narrated in Tomorrow’s Storeys were first conceived in a workshop in mid-March as part of the programming to the run-up of the exhibition opening in mid-May. The workshop of visual artists, authors, photographers, directors and architects produced an abundance of local stories in the future city of Athens, particularly a future Athenian apartment block. In Tomorrows Storeys all apartments blocks have the ability to reorganise themselves automatically – modular entities like seating in the installation. The videos convey intricately detailed shots of the façade of these apartments as well as its contents recalling film shot by aerial drones and ads for IKEA products. The audience act as omnipresent eavesdroppers drifting from storey to storey into the conversations and local happenings in these apartment blocks. These apartment blocks of the future have found a way to reorganise themselves where Athenians are not given a minimum basic income but instead a minimum basic floor area – the occupants do not own an apartment but a specific volume of space which does not have a fixed location. Amongst these stories of shifting permanence and impermanence one stood out: that of an old grandmother dying and the family arguing about who takes over her volume of space as one character cries quite humorously “Can’t you wait until the funeral?!”. Tomorrows Storeys are part of a city where bots constantly reorganise your living in a form of urban computation according to best fit the needs of its citizens. In this way, a living space becomes a temporality, alluding the audience to question if their home is real if it always available for smooth transition to another space.

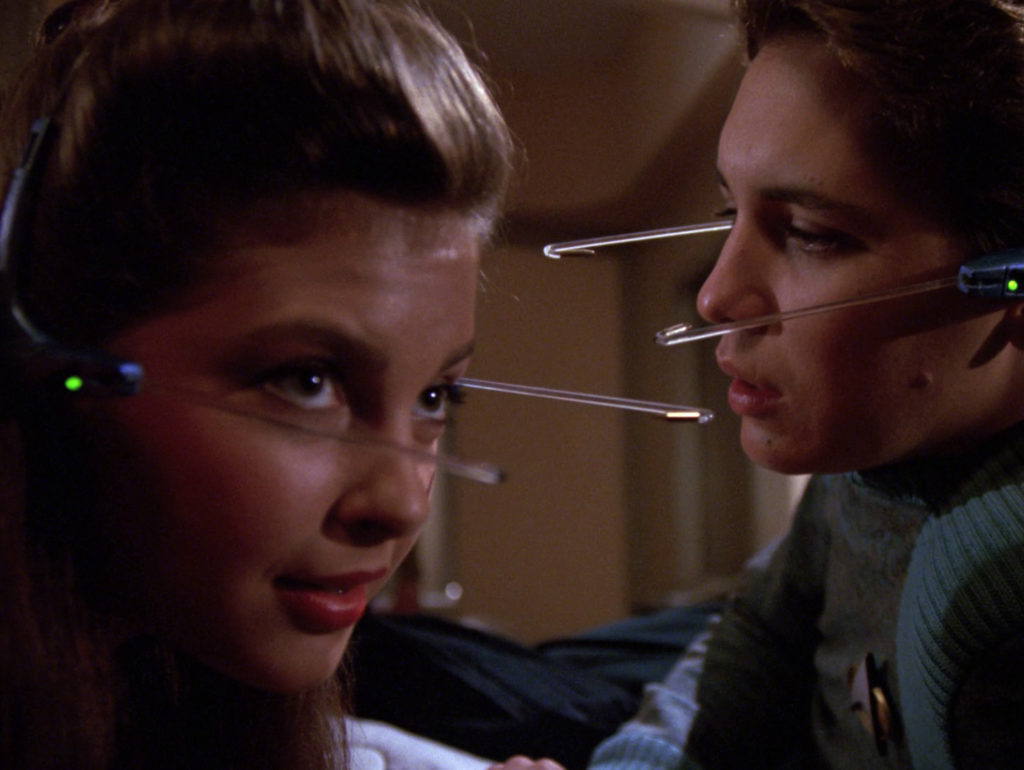

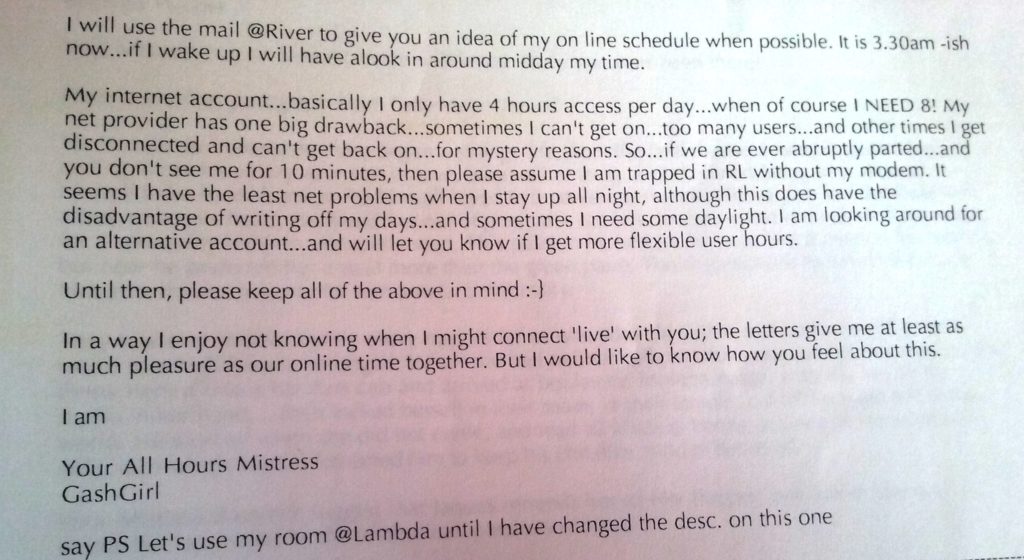

Within urban infrastructures are the human entities contained within them, as Young’s work emphasises, however some of these are becoming increasingly inhuman as the theme of ‘Beyond Anthropos’ suggests. The notion of inhuman or machinic entities being able to replicate human form and intelligence is common and highly popularised since the 1980s as films such as Bladerunner introduced global audiences to ‘replicas’. Today, AI is becoming so intelligent that it urges inventors such as SpaceX and Tesla CEO/founder Elon Musk to warn for correct precautions to be taken when engaging with AI, in fact comparing it to ‘summoning the demon’ and naming it ‘our biggest existential threat’ in the 2014 AeroAstro 1914-2014 Centennial Symposium by MIT. The work of !Mediengruppe Bitnik, coming only a couple of years after Musk’s interview, exemplify the relationship between human and machine. Ashley Madison Angels at Work in Athens is a research project initiated after the data of the Canadian online dating service was leaked in 2015. The leak revealed that Ashley Madison had created 75,000 female chatbots that catered to 32 million mostly male users, engaging them in costly internet intimacy. In Athens, there were 165 fembots for around 22,910 registered users. The installation was comprised of seven of these 165 fembots active in Athens, and were installed in a room dimmed by a fluorescent pink light with screens on tripods similar to average human height and alluding to a physical form. The fembots, programmed to be of different ages, utter pick-up lines they are allocated from a predetermined list to the 22,910 registered users who could not distinguish that they were talking to a machine and not a real person.

Tomorrows does not wish to present us a future as a prediction or as a form of critique of these technological, environmental and urban developments. Rather, it presents the future as an on-going participatory project, as a tool that can be utilised to examine who we are and where we are at in present tense, as well as where we could be potentially going. These urban fictions of our possible futures, are a speculative activity with the capability of making us more aware of the changes that have taken place whilst simultaneously illustrating the changes that are afoot. Tomorrows was a show that took place over six months ago, but its value to the discourse of the future will remain timeless for decades to come.

This is the third of three pieces on people who are posting work to the photography sharing site Flickr [1].

In this final article I look at the work of Karin Rudolph

. Rudolph is a Belgian photographer, currently living in Athens, where she works as a wedding and event photographer and raises two teenage sons. In addition to her work for pay she makes an ongoing series of ‘personal’ images which she regularly posts to the photo sharing site Flickr.

I ask her to send me some images from a wedding job and she does.

It is a job she is clearly good at—everything is beautifully shot, nicely framed, sharply in focus (when sharp focus might be thought necessary), but there is that extra something that comes with a good portrait photographer, which I can only describe as fellow feeling. A fellow feeling which elicits transparency and a willingness to risk vulnerability from the subject. I’ve never met Rudolph but it’s clear that her personality, her way of being, is a player here.

There’s also a sharp curiosity at work—a hunger for the way the world looks and with Rudolph this seems to become attached to particular objects, creatures (some human, some not) and roles. There was a dog at the wedding in the images she sent me. The wedding took place outdoors and the clearly much loved animal figures in a number of the shots. It’s as if at one point R becomes fascinated by it and we get shots where the all humans are cropped (in the shooting; she doesn’t crop after the fact) down to the waist and the dog becomes central (although a small child has a supporting role here too since he necessarily evades the crop/frame wholesale). We get a dog narrative. Then a bouquet catches her eye and we get a bouquet narrative, the wedding filtered through a non-human being or an object. Motion—a sense of the moment before and the moment after being necessary, if hidden, components of this still image—is a key underpinning of so many of these images, particularly in relation to these micro-narratives.

In a photographer less manifestly gripped by the facts of our fragile human being and ways in the world one might call some of her approaches formalist. It is certainly true that rhyme, echo, geometry, continuities and disruptions of line, shape and colour play a highly significant role in the structuring of her images but one of the driving forces of R’s work is that it constantly moves to dissolve any artificial divide between content and form. Yes, her eyes seek pattern; yes, this or that organising device might order an image but this never obscures our awareness of the facts, feelings and relationships portrayed or implicit there. Also—we humans are formalists, aren’t we? We’re pattern seekers. We play. Were you never fascinated as a child by mirrors, by the world turned upside down by hanging from your legs or by the cropping or heightening, or focus) achieved by looking through the cracks in your fingers? Of course you were. As we grow we perceive the whole world through a complex dialectic of what is presented to our senses on the one hand and our burgeoning sorting and structuring principles on the other. We are of necessity creatures of content and form together and one surmises that this is what makes us creatures of art too.

I’d been writing and thinking about this piece for a few months, on and off, and I’d got to a second or third draft when it hit me with a thud, a jolt, that hardly any of the recent images have titles.

The fact had just sailed under my radar, curiously, since I’ve argued and will again, that insofar as we can talk about meaning in a photo (or any visual artwork) this possibility lies in a network of references and comparisons which ineluctably involves talk, writing or both. Language. Further, that visual art is best seen as something humans do (emphasis on both words) than as the usual set of isolable ‘in and of themselves’ objects (which isolation is a fiction, at best an analytical convenience). And then it struck me ( I was being struck a lot that day) that there is something about these images that fights back against language—they’re often cross genre and resist categorisation and there’s a sense in which the easiest approach to what’s in them is simply to list it, and finally to say that this image had these things in it under this kind of light from that angle but, of course, this is far from satisfactory and at root there is something far transcending taxonomy or description going on. But –dammit! –I can’t help feeling it is as if the images (placed as they are in the sequence formed by Flickr) are calling out, hailing each other. I don’t know why, but forced rhubarb, a most unlikely image, is the one which springs to mind and persists, as if the absence of the immediately adjacent language of a title somehow forces the set of glorious but hitherto mute images to invent speech.

Anyone who has ever taken an un-posed image of a human being on a fast shutter speed will be cautious about ascribing emotions or characteristics to the subject on the basis of what is revealed. As in so many other ways, the very small, the very distant or unreachable, animal locomotion, the photograph reveals things beyond our normal ability to see or grasp them. One of these things is the curious plasticity of the human expression and how in our interactions we read this in sequence, in time, together with a host of other clues, aural and visual, to make sense of what is going on, to try to understand both what a person is doing and to surmise what they might be feeling . (Of course the opposite of this, the posed image, brings its own problems too.)

When we think hard and soberly we cannot but be convinced that the photograph alone, an impossibly small fragment of time, does not allow us enough evidence, that it is somehow unanchored in the world.

And yet, the desire to draw conclusions, to make comment, is certainly strong in us and each photographic image of a person, especially the striking and affecting ones, comes with a very strong sense that we are able to do so.

What can we actually say about the still photographic portrait, both in general and in particular cases?

One thing we might say is that the single image’s apparently complete account of a human being, based upon a fleeting expression (and perhaps the fleeting expressions in response of others and maybe also the presence of contextualising objects or other clues) suggests at best, a class of possibilities. This single image evokes a range of other possible images and moments in the world at least one of which must correspond to our strong intuitions about it. So even if we were able to establish the facts of the matter in this particular case and it made a lie of our emotional response , nevertheless that response represents a truth and somewhere, perhaps quite often, in the world, situations occur, have occurred, will occur, which correspond to this truth.

And it seems to me that it is this instinct for general human truth, allied to the particularity of light, line, composition, of other things depicted, which manifests in the eye-and-heart-catching-ness of the resulting final image.

A strong way of putting it would be that any portrait is just as much a work of fiction as a novel but that as we would not wish to deny something called ‘truth’ in the novel ( you might—I see no point to the thing otherwise) in the portrait we work our way back to truth.

And at least for me it is the photographer’s—and here, now ‘the photographer’s’ means R’s—capacity for empathy, for narrative, for understanding of the world and the wonder and the oddness of its inhabitants that makes her such a good portraitist (and let’s not forget, too, simply having done the thing a lot —this is often underrated nowadays.)

Do I know whether the Orthodox priest at the wedding table was a kind man? No. I don’t. I cannot. Is kindness manifest in the photo, is the possibility of kindness in the world reasonably asserted in it? Do I know more about kindness thereby? Absolutely.

There’s a black and white image, taken, I think, at the place where her teenage sons practice their footballing skills which feels like a short story or perhaps a collection of short stories, each cued by the various human presences which form at one and the same time a large (in how they capture our attention) and a small (in how much actual area of the image they occupy) part of the entire image.

It also has a most clearly defined geometry—three strips, the topmost being the practice field itself, the middle appearing to be a road like depression running between the photographer and this field and the lowest a pavement of some sort on the other side of that ‘road’. The almost bizarrely long evening shadows of R and a companion (and the horizontal distance between shadows is nicely ambiguous on the exact relationship between those shadowed) stretch forward into the image. The vertical grid adjacent to them, with a gap in the centre picked out in shadow too, suggests they are standing at a pedestrian gate to the place. I imagine the figure at the viewer’s right is R as the arms appear to be raised in a photo taking action.

(The image thumbs its nose at genre—it is oblique self-portrait, landscape, social history, portrait and exploration of geometry and structure all at the same time.)

Shadows aside, the figures which catch my eye (what about you, so much to choose from or are you constrained in a similar way to me by something in the way the image is structured?) are the short stocky man in motion, walking away from us at the image’s far right top strip foreground. There’s a delicious swagger and confident openness about him.

Has he passed through the gate where R stands? Did he greet her?

The second key (perhaps because nearest?) figure is the young man, top strip, viewer’s far left, again in movement, this time almost certainly certainly sports related. Is he pursuing a stray ball? Running to greet a friend? Engaged in some sort of running warm up/exercise? As we strain to see, our relationship to the image’s scale shifts and we begin to realise just how many other figures he opens up to us—there are at least six either standing or seated in those little sheds at the field’s side between him and the left edge of the nearest goal net—each an enigma of a small but definite kind—and when we move rightwards from them we realise (and we have to move closer in, look differently, at the image to see this) just how many people there are in some sort of action here. As we move out again we are stuck by the contrast between the contemplative calm of the giant shadows and the anthill busyness of the young men. And here’s another thing. This is such a male photo. (With the exception of the photographer and I think it’s only because I know she is female that I read her as such. Then even as I write this I notice the slight head-cocked-to-one-side quality of aficionado-like attention in the head of the left shadow—and why do I think that might clue maleness? What does that say about me?) Oh! Layers and layers of fact, of presence, of things to enumerate and puzzle over. So much! And this before we take the thing as a totality—geometry, inhabitants, shadows, activity, motivation, time of day, distant trees, weeds and barren ground, a sky whose colour we can only guess from the fact we know there is evening sun. And that totality is the hardest thing to compass in any way other than an intake of breath or shiver down the spine. Enumerating the contents helps (although it’s not essential to the immediate affective apprehension of the whole—that just happens) but it’s the inexplicable (not a value judgement—literally inexplicable—simply, ‘This is what R did’) decision to frame those contents in that way—the bit of the process which defies words—that makes this and so many other pieces by her so powerful.

5.

A ravenous eye.

She has a ravenous eye, constantly tracking the scene in front of her and hungry for detail. This hunger does not distinguish between content and form. Whatever is human, whatever stirs affect or curiosity—whether pattern, rhyme or echo, or ethics, or suggested human warmth or frailty, this is swallowed up and processed by heart and mind in turn

The resulting images bear the strong feel of certain, almost objective, structuring principles—that following of object or creature within a scene, the use of rhyme and echo. Two further categories are geometry and colour (and nothing here is pure, there are no essences, sometimes blocks of colour impose an extra, parallel geometry upon a scene whose first order sense—whether it be human beings in action or traces of interpretable human activity; buildings, signs, the street —apparently lies elsewhere.) The key thing about all these structuring principles is that they are found, excavated, discovered, seen—not made. They happen in parallel with, arise out of the actions and feelings of, human beings in this world, the only one we have.

Because she is someone who has lived, fully, in that world, for a fair time, because her hunger extends beyond the visual (she always has a book on the go and the range of these is impressive), because she has a number of languages and is at home in at least three cultures, she makes images which are connected and re-connected by hundreds of threads to things we ourselves might have read and thought or experienced and talked about. Further, it is impossible to imagine that the fact she is a woman living in a country not of her birth, where she has learned a different script, different ways of talking and being, where she works in part as an image maker for hire and constantly both connects and holds separate that work for pay from own ‘own’ work, at the same time as raising children by herself, that these facts are not also somehow foundational.

For a long time I have struggled with how to attach the word meaning to image. It is too easily and glibly used. An image never ‘means’ a single thing (unless it is the poorest of images and even then the human capacity for/delight in ambiguity sets to work to disrupt this) What is evident in Rudolph’s work is networks of evoked meaning, memories, feelings.

Her way of being in the world, this following her eye and nose, means that there is a kind of metonymy purged of any attempt at system—here is a dog or child or chair or window. Here are the things which necessarily were near it at a moment in time and this is how they were disposed. There was reason and there was randomness. Parts of the disposition were beautiful. (What do I mean by beautiful? They move me, they fill me with a joy that cannot be reduced to words though it perhaps can be limned by various combinations of words, combinations potentially infinite which always nearly but not completely fail.) Parts of the disposition were stark or threatening or at least worrisome. The bringing together of all these parts—worry, beauty, pattern, action—into an image framed, bounded, lit, by the laws of the heart and the laws of the intellect now pulling one way, now the other. The work about the world is itself part of the world. We are not alone. No person is an island. We can read each other’s thoughts. We can feel each other’s feelings.

The words and the image and human heart and human history dance ever outwards and outwards. What does an artist do but always start to write the whole history of humanity in the world?

This series brings together artists, musicians, technologists, engineers, and theorists to join forces in the interrogation and production of new blockchain technologies.

Our focus will be to understand how blockchains might be used to enable a critical, sustainable and empowered culture, that transcends the emerging hazards and limitations of pure market speculation of cryptoeconomics.

Intended as a temporary laboratory for the creation of a living laboratory, the inaugural workshop in the series takes a pragmatic approach towards building technical and economic capacity in the arts.

As the DAOWO series unfolds, each lab will work across a spectrum of themes and domains of expertise, breaking down silos and assumptions about what blockchain technologies might mean. The aim is to birth a new set of experimental initiatives which can reinvent the future of the arts as we know it.

Thu 26 Oct: Reinventing the Art Lab (on the blockchain)

Venue: Goethe-Institut, London | BOOKING ESSENTIAL

2-5.30pm Workshop devised and hosted by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers

7-8.30pm Panel discussion with Hito Steyerl, Helen Kaplinsky, Julian Oliver

The Subsequent DAOWO Programme of Labs and Debates

Thu 23 Nov: Identity Trouble (on the blockchain)

Thu 25 Jan 2018: Doing Good (on the blockchain)

Fri 16 Feb 2018: Artists Organise (on the blockchain) (special event with Clubture at Drugo More, Rijeka)

Thu 22 Feb 2018: The Decentralised Music Society reforming music (on the blockchain)

Thu 29 Mar 2018: What Will It Be Like When We Buy An Island (on the blockchain)?

This programme is devised by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme. Its title is inspired by a paper by artist hacker and writer Rhea Myers called DAOWO – Decentralised Autonomous Organisation With Others.

Events will be hosted at the Goethe-Institut, London and Drugo More, Rijeka.

About Ruth Catlow

Ruth Catlow is an artist, writer and curator working with emancipatory network cultures, practices and poetics. She is the co-founder, co-director of Furtherfield.

About Ben Vickers

Ben Vickers is a curator, writer, explorer, technologist and luddite. He is CTO at the Serpentine Galleries in London and an initiator of the open-source monastic order unMonastery.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

This short (20 minute) film has been made by artist Michael Szpakowski working with two classes of year 4 pupils at Southwark Park school in Bermondsey.

Freely adapted from King Hrolf Kraki’s Saga it is a grim tale of internecine bloodletting in Viking times told in the childrens’ own words and acted out by them.

“Of all the pieces of “outreach” – I’d rather call it co-constructed – work I’ve done over the last thirty years, this piece comes closest to satisfying both the most important requirements of such work. The young people are totally engaged in the process and proud of the final product. Also and more importantly, I feel that it is aesthetically satisfying as any work I make entirely alone; so the finished piece is both a universal fable which tips its hat in homage to Brecht, Bresson and Straub-Huillet and also a hymn to the energy, wit and resourcefulness of the eight to nine year old and to an inner London multicultural school community at its best.”

Public screening at BFI- NFT2 4pm Thursday 25th June 2011

http://www.bfi.org.uk/

Seats are limited. Please contact ale[AT]furtherfield[DOT]org

A Furtherfield Outreach Project

Partners: Creative Partnerships, A New Direction, Southwark Park Primary School

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

FREE DOWNLOAD OF EXHIBITION DOCUMENTATION

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

Featuring Katriona Beales and Fiona MacDonald.

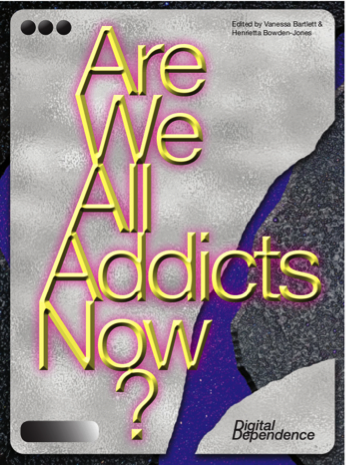

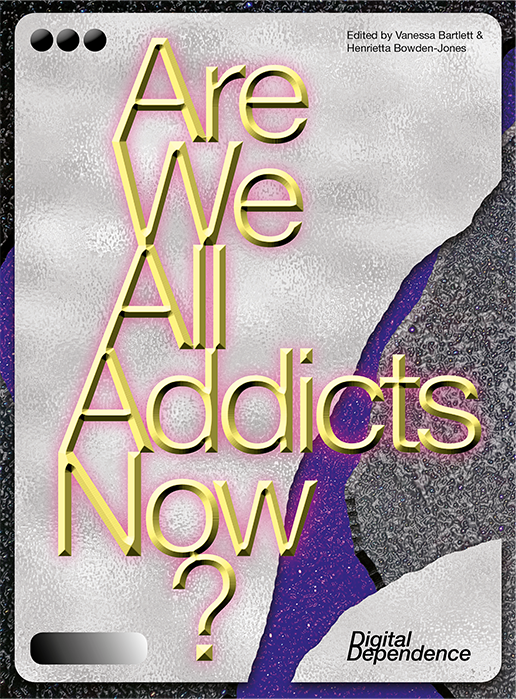

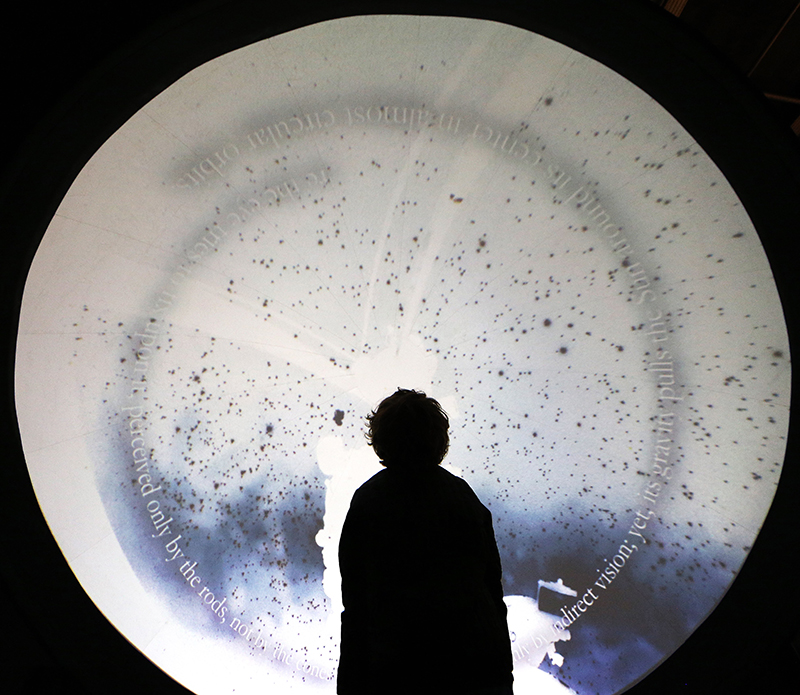

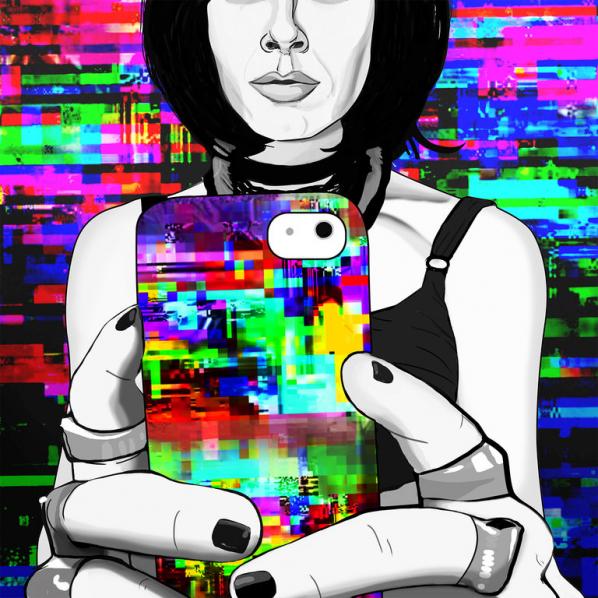

The exhibition and research project Are We All Addicts Now? explores the seductive and addictive qualities of the digital.

Artist Katriona Beales’ work addresses the sensual and tactile conditions of her life lived online: the saturated colour and meditative allure of glowing screens, the addictive potential of infinite scroll and notification streams. Her new body of work for AWAAN re-imagines the private spaces in which we play out our digital existence. The exhibition includes glass sculptures containing embedded screens, moving image works and digitally printed textiles. Beales’ work is complemented by a new sound-art work by artist and curator Fiona MacDonald : Feral Practice.

Beales celebrates the sensuality and appeal of online spaces, but criticises how our interactions get channeled through platforms designed to be addictive – how corporations use various ‘gamification’ and ‘neuro-marketing’ techniques to keep the ‘user’ on-device, to drive endless circulation, and monetise our every click. She suggests that in succumbing to online behavioural norms we emerge as ‘perfect capitalist subjects’.

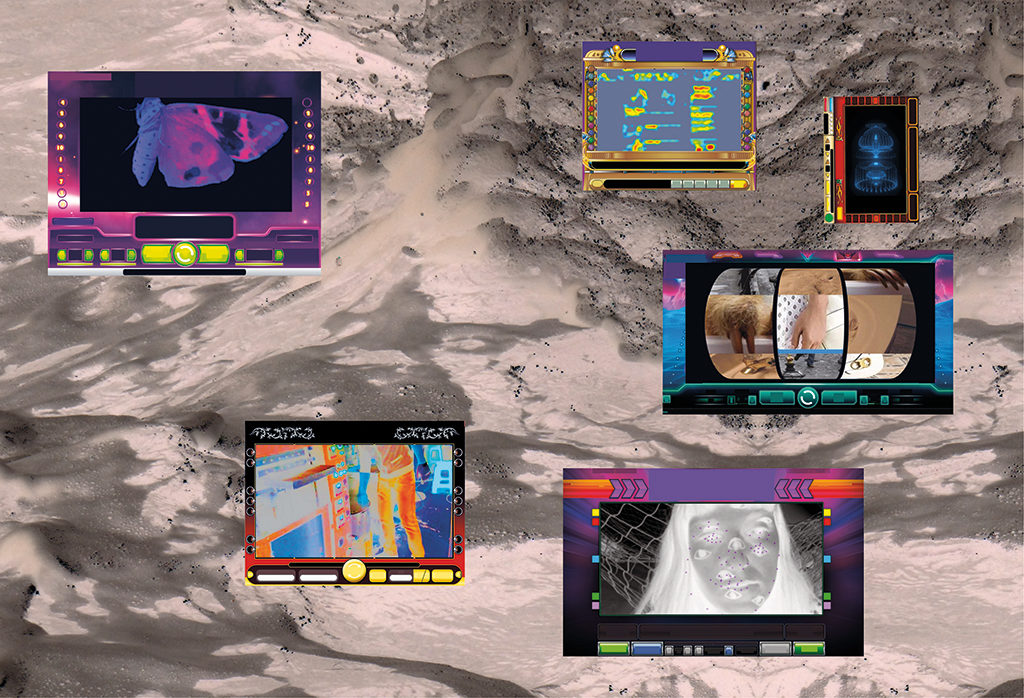

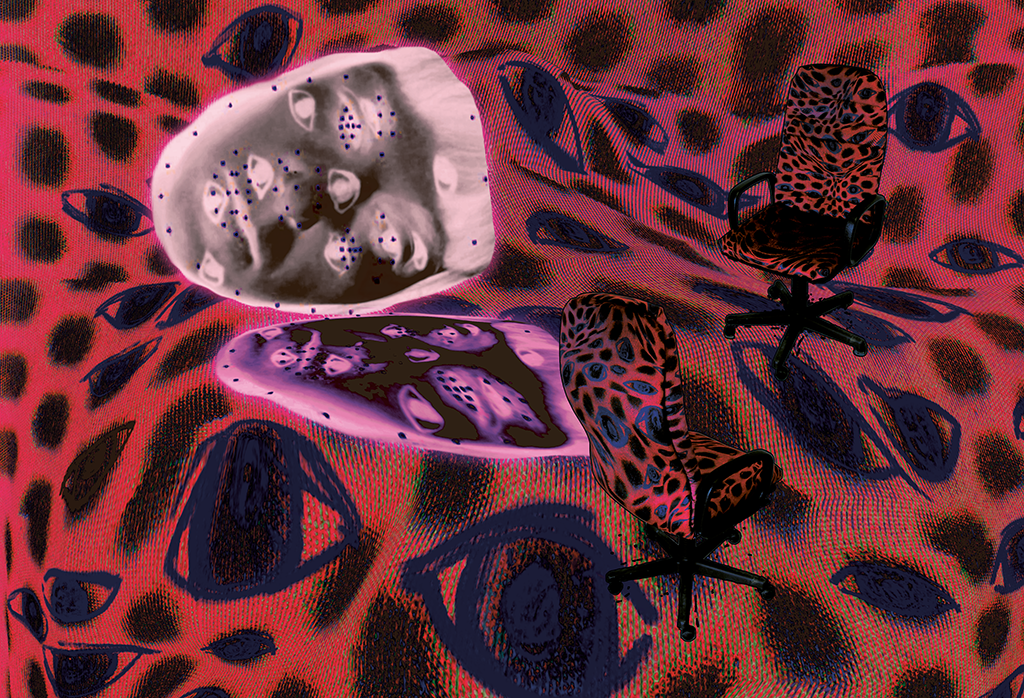

For Furtherfield, Beales has constructed a sunken ‘bed’ into which visitors are invited to climb, where a glowing glass orb flutters with virtual moths repeatedly bashing the edges of an embedded screen. A video installation, reminiscent of a fruit machine, displays a drum of hypnotically spinning images whose rotation is triggered by the movement of gallery visitors. Beales recreates the peculiar, sometimes disquieting, image clashes experienced during her insomniac journeys through endless online picture streams – beauty products lining up with death; naked cats with armed police.

Glass-topped tables support the amorphous curves of heavy glass sculptures, which refract the multi-coloured light of tiny screens hidden inside. Visualisations of eye-tracking data (harvested live from gallery visitors) scatter across the ceiling. On the exterior wall of the gallery, an LED scrolling sign displays text Beales’ has compiled, based on comments from online forums about internet addiction.

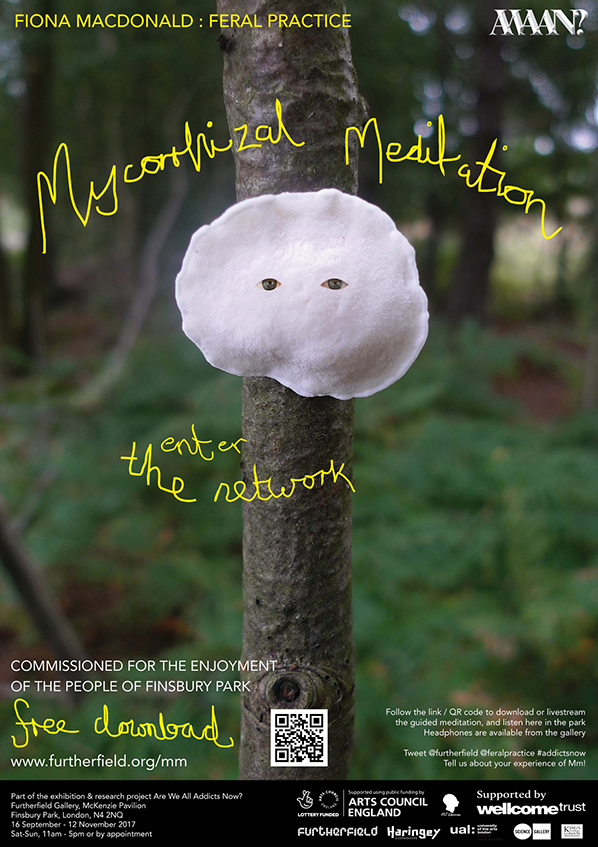

Where Beales addresses the near-inescapability of machine-driven connection, Feral Practice draws us into the networks in nature. Mycorrhizal Meditation is a sound-art work for free download, accessed via posters in Furtherfield Gallery and across Finsbury Park. MM takes the form of a guided meditation, journeying through the human body and down into the ‘underworld’ of living soil, with its mycorrhizal network formed of plant roots and fungal threads. It combines spoken word and sound recordings of movement and rhythm made in wooded places. Feral Practice complicates the idea of nature as ‘ultimate digital detox’, and alerts us to the startling interconnectivity of beyond-human nature, the ‘wood-wide-web’ that pre-dates our digital connectivity by millennia. (Download Mycorrhizal Mediation here)

Are We All Addicts Now? has been developed in collaboration with artist-curator Fiona MacDonald : Feral Practice, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett.

Glowing light of screens makes us #addictsnow – they are the mini-suns we bask in to keep away the dark https://t.co/jedrDUE2ZWpic.twitter.com/BmTTbFckFp

— furtherfield (@furtherfield) July 27, 2017

View more of the comissioned gifs and tweets here

In the run up to the exhibition, artists Charlotte Webb and Connor Rigby have been commissioned to produce a series of gifs and tweets to stimulate debate around the designed-for-addiction nature of digital devices, and the ethics and politics that surround this. Join the conversation @furtherfield on Twitter and Instagram using the hashtag #addictsnow

Accompanying the exhibition, a book designed by Stefan Schafer and edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, brings together Beales’ and MacDonald’s artwork and writing with essays from contributors in the fields of anthropology, digital culture, psychology and philosophy. This book is the first interdisciplinary study of the emerging field of internet addiction. Contributors will discuss their essays at a symposium convened by Vanessa Bartlett at Central Saint Martins in November 2017. Advanced copies of the book are on sale at the Liverpool University Press website https://liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/100809

Beales’ work ‘Entering the Machine Zone’ has been co-commissioned with Science Gallery London. An iteration of the work will be presented as part of HOOKED, the opening season of the new Science Gallery London, curated by Hannah Redler.

Exhibition Tour of Are We All Addicts Now? with Ruth Catlow and Katriona Beales

Saturday 16th September 2017, 2-4 pm

Furtherfield Gallery

Join Furtherfield co-director Ruth Catlow and artist Katriona Beales to find out more about the works featured in the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? and to discuss the issues that it raises around digital addiction and online behaviour.FREE | booking essential

Late Night Opening & Film Screening

Friday 29th September 2017, 5 – 8.30pm

Furtherfield Gallery & Commons

A late night opening of the Are We All Addicts Now? exhibition, followed by a screening of artists’ moving image work that has informed the development of the exhibition.

Gallery Open: 5 – 7pm

Screening: 7 – 8.30pm

FREE | booking essential

Mycorrhizal Event with Fiona MacDonald : Feral Practice

Saturday 21st October 2017, 2 – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

Fiona MacDonald: Feral Practice presents a lecture, a performance, and a fungi walk. Informed by the history, art and science of human-fungal relations, these experiences explore themes of reciprocity, intuitive and nonverbal interconnection between people, psychedelic consciousness, fungal songs, shamanic journeying, and plant communication.

FREE | booking essential

Visual Matrix Workshop with Vanessa Bartlett

Thursday 2nd November, 4 – 6.30pm

Furtherfield Commons

Join curator Vanessa Bartlett for a research workshop responding to works in the Are We All Addicts Now? exhibition. The visual matrix is a new psychosocial research technique that we are using to generate audience response to this project. Content generated during this session will inform our evaluation of the exhibition.

For more information and to book your place contact info [at] vanessabartlett.com

FREE | email v.bartlett [at] unsw.edu.au to book your place.

Are We All Addicts Now? Symposium and Book Launch at CSM

Tuesday 7th November, 6.30-9pm

Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, 1 Granary Square, London, N1C 4AA

This event celebrates the publication of Are We All Addicts Now? Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones and will feature presentations from many of the book’s key contributors who include:

During the symposium, psychologists, philosophers and artists come together to discuss the emerging diagnosis of internet addiction. Taking into account our precarious economic and political climate, they will ask whether internet addiction should be understood as a form of illness, or simply a sensible adaptation to our current environment? As increasing numbers of people struggle to moderate their online behaviours, this event will also explore artists’ strategies for counteracting the seductive, addiction-making qualities of digital space.

Convened by curator Vanessa Bartlett

Presented in partnership with Central Saint Martins Art/Design and Science Research Group

The book, ‘Are We All Addicts Now?’ is available from Liverpool University Press: liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/100809

See photos from the Symposium and Book Launch

See a recording of the Symposium and Book Launch – Part 1 | Part 2

£4 – £7 | booking essential

Katriona Beales is an artist who makes digital artefacts, moving image and installation, stressing the physicality of digital life. Are We All Addicts Now? develops Beales’ 2015 work ‘White Matter’ (a FACT commission for ‘Group Therapy: Mental Distress in a Digital Age’) which is showing at the University of New South Wales, Sydney as part of Anxiety Festival (Sept 2017). Beales’ received an MA from Chelsea College of Arts and has an artist profile on Rhizome.org

www.katrionabeales.com

Fiona MacDonald is an artist, curator and writer specializing in human-nonhuman relationship. As Feral Practice, she works in co-production with a collective of human and nonhuman persons. Current projects include Foxing, (see PEER London, 2017) Ant-ic Actions (see Ethical Entanglements, Bloomsbury Press, forthcoming) Homo Mycelium, and Wood to World (London, Kent, Aberdeen 2015-17).

www.feralpractice.com

Vanessa Bartlett is a researcher and curator based between Australia and the UK. She studies and teaches at UNSW Art & Design, Sydney where her research investigates connections between digital technologies and mental health through reflective curatorial practice. Her recent exhibition Group Therapy: Mental Distress in a Digital Age showed at FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), UK in 2015 and opens at UNSW Galleries Sydney in September 2017.

www.vanessabartlett.com

Dr. Charlotte Webb is an artist and deviant academic. She speaks and exhibits internationally, focusing on the web as a medium for creative practice, critical thinking and collective action.

Furtherfield is an internationally renowned arts organisation specialising in labs, exhibitions and debate for increased, diverse participation with emerging technologies. At Furtherfield Gallery and Furtherfield Lab in London’s Finsbury Park, we engage more people with digital creativity, reaching across barriers through unique collaborations with international networks of artists, researchers and partners. Through art Furtherfield seeks new imaginative responses as digital culture changes the world and the way we live.

“There is no other gallery like Furtherfield. Situated in the middle of Finsbury Park they attract people from all walks of life and focus on contemporary technology and how it affects the lives of people and the world we live in.” (Liliane Lijn, artist)

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

Thanks to:

The Wellcome Trust

Arts Council England

Science Gallery London

Central Saint Martins

BF Skinner Foundation

Haringey Council

Bruce Marks (glass artist)

Rob Prouse (raspberry Pi and AV technician)

Part of the Are We All Addicts Now? exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

SEE IMAGES FROM THE SYMPOSIUM AND BOOK LAUNCH

SEE A RECORDING OF THE SYMPOSIUM AND BOOK LAUNCH – PART 1 | PART 2

This event celebrates the publication of Are We All Addicts Now? Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones and will feature presentations from many of the book’s key contributors who include:

During the symposium, psychologists, philosophers and artists come together to discuss the emerging diagnosis of internet addiction. Taking into account our precarious economic and political climate, they will ask whether internet addiction should be understood as a form of illness, or simply a sensible adaptation to our current environment? As increasing numbers of people struggle to moderate their online behaviours, this event will also explore artists’ strategies for counteracting the seductive, addiction-making qualities of digital space.

Ticket price includes a drink *:

£7 full price | £4 concessions (UAL staff/student, external student unemployed, senior)

*ticket price covers a token for 1 alcoholic drink or 2 soft drinks, with a pay bar available for additional purchases.

BOOKING ESSENTIAL

The publication will be available to purchase on the night at the discounted price of £10 (cash only, RRP £14.95). The book, ‘Are We All Addicts Now?’ is also available from Liverpool University Press: liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/100809

Convened by curator Vanessa Bartlett

Presented in partnership with Central Saint Martins Art/Design and Science Research Group

14.00-17.30 – Workshop devised and hosted by Ruth Catlow and Ben Vickers

19.00-20.30 – Panel discussion with Hito Steyerl, Helen Kaplinsky and Julian Oliver

Workshop participants who wish to also stay for the panel event should book for both events individually

Does Art need its own blockchain? Can blockchain technologies help create and retain value for artists and arts organisations? If blockchains are transforming all other industries and supply chains, how will it effect the arts? Is this technology at a stage now where we can begin applying it to our everyday processes and practices?

These are just a few of the questions we have been asking ourselves and others over the course of the last year. In the scheduling and convening of this workshop series we invite others to join us as we delve deeper into the pragmatics of applying these questions to specific scenarios.

Designed as a temporary laboratory for the creation of a living laboratory, the inaugural workshop in the series will take a pragmatic approach in mapping out technical and economic capacity for the application of blockchain technologies within the arts.

This workshop will open with an overview of current developments for blockchain application within the arts ecosystem, outlining the key opportunities and challenges. Serving as the background, this will lead into a series of short presentations by practitioners who have invested their time over the past years unpicking the treacherous complexity of the blockchain. Each of these areas will then be built upon through facilitated working groups – with the explicit objective of enabling initiatives to move into a new phase of development.

As the workshop series unfolds, each lab will work across a spectrum of themes and domains of expertise, breaking down silos and assumptions about what blockchain technologies might mean. The aim is to birth a new set of experimental initiatives with each lab, which can contribute towards rethinking and reinventing the future of the arts as we currently know it.

“If art is an alternative currency, its circulation also outlines an operational infrastructure. Could these structures be repossessed to work differently?” – Hito Steyerl

Following the inaugural workshop of the DAOWO series, this panel will seek to establish a public platform for the discussion of opportunities, dangers and complexity inherent in the very idea of applying blockchain technologies to the production and circulation of art.

Exploring both hands on practical applications and the theoretical long term impact of a technology that enables a vast array of unexpected new conditions, under which the artworld and art market may be forced to operate. From fractional ownership, strict provenance models, untraceable financial transactions, autonomous artworks to new fully automated organisational forms – this panel will seek to unravel and interrogate both the banality and the terror of blockchains future impact on the arts.

Hito Steyerl’s films, installations and writings come out of a systemic way of thinking and working, in which artistic production and the theoretical analysis of global social issues are closely linked. Steyerl investigates the interaction and synthesis of technological and artistic imagery, for example, at the level of visual mass culture – and its function within the overall dispositif of technocracy, monetary policy, the abuse of power, and violence.

Helen Kaplinsky is a curator and writer based at Res., a collaboratively programmed gallery and workspace in Deptford, South East London, currently working in partnership with nearby University of Goldsmiths. Specialising in collection and archive based projects, the thematics and strategies of her curatorial projects consider property in the age of digital sharing. She has contributed to programmes at Whitechapel Gallery, South London Gallery, Glasgow International Festival, ICA (London), The Photographers Gallery (London), and has ongoing programmes with Tate and FACT (Liverpool).

Julian Oliver is a Critical Engineer and artist based in Berlin. Julian has also given numerous workshops and master classes in software art, data forensics, creative hacking, computer networking, counter-surveillance, object-oriented programming for artists, augmented reality, virtual architecture, video-game development, information visualisation and UNIX/Linux worldwide. He is an advocate of Free and Open Source Software and is a supporter of, and contributor to, initiatives that reinforce rights of privacy and anonymity in networked and other technologically-mediated domains. He is the co-author of the Critical Engineering Manifesto and co-founder of Crypto Party in Berlin, who’s shared studio Weise7 hosted the first three crypto-parties worldwide. He is also the co-founder of BLACKLIST, a screening and panel series focused on the primary existential threats of our time.

The DAOWO programme is devised by Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) and Ben Vickers (Serpentine Galleries & unMonastery) in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London, and the State Machines programme.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.