In 2019, we celebrated 150 years of Finsbury Park being the ‘People’s Park’ – a place where we can all do things together. In 2020 protests across the UK saw public artworks toppled from plinths, while the pandemic left us separated and isolated.

With this in mind, we launched the People’s Park Plinth this summer, as a way to re-explore our public spaces by turning Furtherfield Gallery inside out and expanding its digital arts programme beyond our walls and into the life of Finsbury Park.

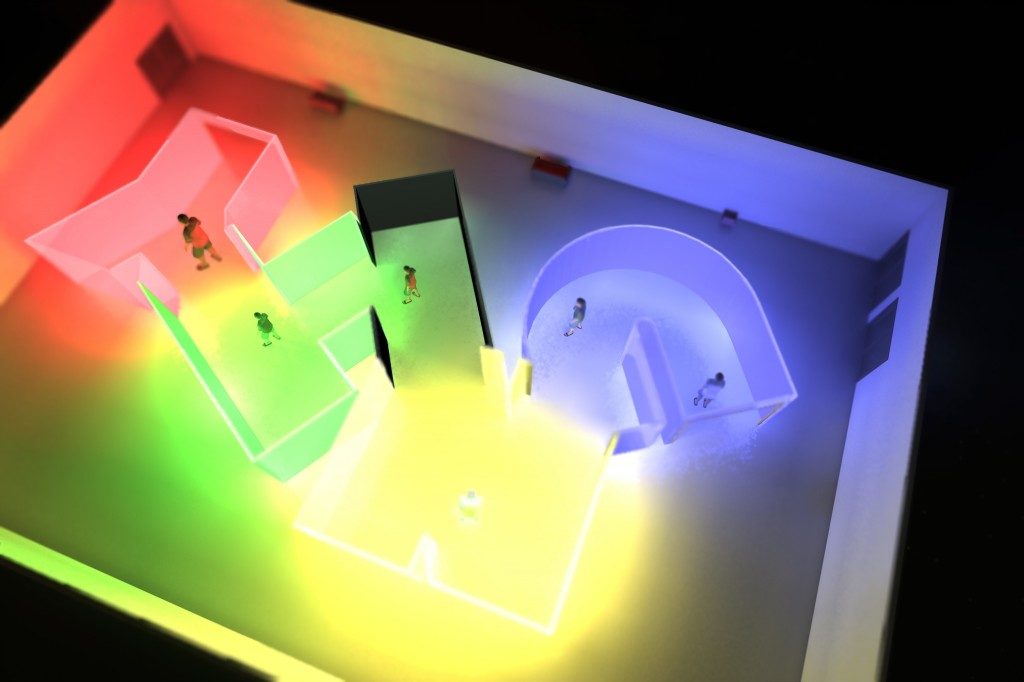

We collaborated with incredibly talented artists, curators and local park members to create 3 ‘taster’ digital public artworks that speak about the park’s heritage and local stories. In May, June, and July we showcased a different digital art experience each month.

In August, the park made its pick! We will be launching a larger commission of Based on a Tree Story this Autumn, and to continue celebrating the heritage, artistry and local voices from Finsbury Park, all the ‘taster’ artworks will be available until January 2022.

If you are in Finsbury Park you can use the camera on your phone to scan the QR codes on the People’s Park Plinth (presented on the exterior of our Gallery building in the centre of the park). They are all free to access, any time, with any smartphone – but you might want to have some headphones handy too.

If you are somewhere else you can click the links on the People’s Park Plinth website to find the artworks.

It’s your park so it’s your pick!

Sign up here to get involved in choosing the artwork that most belongs in the heart of Finsbury Park next year.

Breath Mark x Lisa Hall & Hannah Kemp-Welch

Live until January 2022

A site-specific, interactive sound work creating moments of connection between strangers of all species.

Follow this sound work as it leads you across the park to meeting points for animals, plants and strangers. As you listen, consider the needs of all these inhabitants and our symbiotic relationship that is increasingly under threat. Between heartbeats, vibrations and the alignment of crossing paths, this work sounds out a shared existence, putting these moments of connectivity with strangers of all species on the People’s Park’s Plinth.

The work features interviews with volunteers at Edible Landscapes, a forest gardening group based onsite at Finsbury Park: David Berrie, Imogen Simmonds, Jo Homan, Juliette Ezavin and Theo Betts. The artists were commissioned by Breath Mark, a curatorial collective formed as a part of the Royal College of Art’s MA Curating Contemporary Art Programme Graduate Projects 2021 in partnership with Furtherfield’s People’s Park Plinth project.

Taster: In this first iteration of the artwork, one sound pathway ‘Close to the ground’ is presented.

Larger commission: If this work had been selected in the public vote in August 2021, a further two sound pathways and a trail to find them would have been revealed.

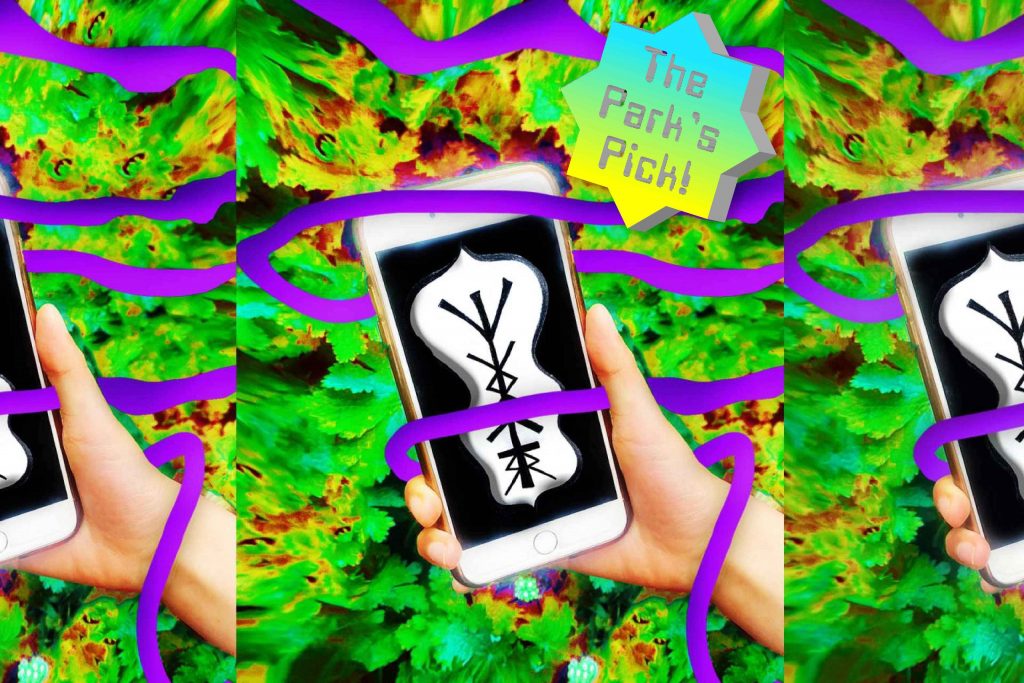

HERVISIONS x Ayesha Tan Jones

Live until January 2022

A site-specific, sonic augmented reality encounter with a digital tree sprite that tells tales of the tree’s past, present and future.

The trees of Finsbury Park are very old, and they have been witness to a lot of change and growth. If the trees had a voice, what would they share?

Based on a Tree Story brings to life Furtherfield Gallery’s nearby resident, a London plane tree dubbed the Trunk Triplets Tree, situated in Finsbury Park and the soils from which they grew, part of the now-extinct ancient woodland, Hornsey Woods. From medieval history to sci-fi futures, their stories are told through an augmented reality and audio experience, giving viewers an insight into the past, while arming them with inspiration and knowledge to help protect the trees into the future.

The project activates a digital tree sprite that shares a fable crafted through local research, site visits and discussion with Ricard Zanoli, the Park Ranger.

Taster: In this first iteration of the artwork one tree story is presented.

Larger commission: This work was selected in the public vote in August 2021 and further two tree stories and a trail of clues to find them will be revealed this Autumn.

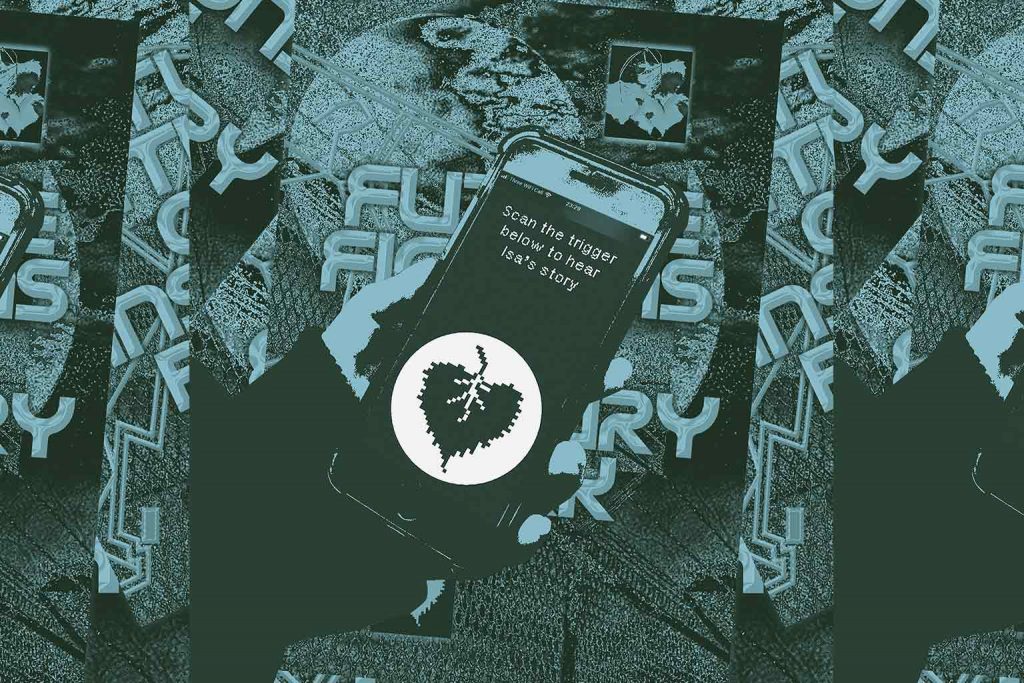

Desree x Drumming School with Alex Dayo x Studio Hyte

Live until January 2022

An augmented reality (AR) sci-fi zine comprising three stories that bring together writers, musicians, and local residents to explore alternative visions of a Finsbury Park of the future.

For this first iteration of the AR zine, released in July 2021 as part of the People’s Park Plinth programme, we present The Light and Dark: an audio-visual story about a fictional character, Isa, who wakes up in a home they don’t recognize, surrounded by land that feels as foreign as the sky they sit under. Isa does not know how they made it there, but they do know they have to make it home before the host finds them. With only the wisdom of Grandwa, and the feeling in their chest, Isa discovers the power of their historical connection to what was, their land.

The Light and Dark has been written by local spoken word artist and writer Desree, and is accompanied by a unique musical composition by musician Alex Dayo and his park-based Drumming School, in collaboration with David Kemp. The visual design, AR experience and animation have been developed by Studio Hyte.

Taster: In this first iteration of the artwork the start of one future fiction is presented.

Larger commission: Had this work been selected in the public vote in August 2021, this fiction would have been completed and two more would have been revealed.

In August, after experiencing all 3 digital artworks, we asked people to pick which one they thought belonged in the heart of Finsbury Park by either:

Or

The park’s pick is Based on a Tree Story, and we are working with HERVISIONS and Ayesha Tan Jones to make a bigger and better version of their digital art experience – and then we will launch it on the People’s Park Plinth this Autumn!

We wanted everyone to express an opinion – even if visitors were far away what they felt mattered too. But if voters lived locally what they felt mattered more for the vote count – so we weighted the vote for anyone using the CultureStake app within or near the park.

If you are an arts organisation you can find out more about how you can use CultureStake to drive collective cultural decision-making at your own digital and physical events.

Breath Mark is a curatorial collective initiated as a part of the Curating Contemporary Art Graduate Projects Programme 2021, Royal College of Art. Comprising six international members, Breath Mark’s curatorial practice responds to the challenges of curating remotely and explores the interconnectivity of physical and digital site-specific experiences.

Members: Kevin Bello, Jindra Bucan, Harriet Min Zhang, Soyeon Park, Yifei Tang and Yuting Tang.

As part of extended public engagement, Breath Mark has collaborated with design studio An Endless Supply, on a digital microsite acting as a reading room allowing audiences to further engage with the artwork’s themes. We encourage visitors to extend their experiences through the texts, sounds and videos here: spaces.rca.ac.uk

Lisa Hall is a sound artist exploring how environments are built-in sound, while Hannah Kemp-Welch is a socially engaged artist concerned with listening. Hannah and Lisa met at London College of Communication while studying MA Sound Arts in 2010. They share an interest in public and private spaces, and how sound and audio technologies build networks and tell stories that often can’t be seen. They have collaborated on sound art projects for performances and installations at Tate Modern, CRiSAP, and Sound Reasons Festival: New Delhi.

https://www.sound-art-hannah.com

HERVISIONS is a femme-focussed curatorial agency supporting and promoting artists working across new and emergent technologies, and platforms with a strong focus on the intersection of art, technology and culture. HERVISIONS partner with institutes, organisations and galleries to create antidisciplinary exhibitions and innovative commissions. Select partners include, LUX, Tate, bitforms and Google Arts and Culture.

IG: @hervisions_

Ayesha Tan Jones AKA YaYa Bones work is a spiritual practice that seeks to present an alternative, queer, optimistic dystopia. They work through ritual, meditating through craft, dancing through the veil betwixt nature and the other. Ayesha weaves a mycelial web of diverse, eco-conscious narratives which aim to connect, enthral and induce audiences to think more sustainably and ethically. Traversing pop music, sculpture, alter-egos, digital image and video work, Ayesha sanctifies these mediums as tool’s in their craft. Selected recent commissions/exhibitions include: Shanghai Biennale (2021) Athens Biennale (2021) Solo Show at Underground Flower Offsite (2020) Serpentine Galleries, London (2019) IMT Gallery, London (2019) Mimosa House, London (2018), ICA, London (2018-2020) Cell Project Space, London (2018) Gropius Bau, Berlin (2018) Yorkshire Sculpture Park (2016-17). Ayesha is represented by Harlesden High Street Gallery, London.

https://www.ayeshatanjones.com/

Desree is an award-winning spoken word artist, writer and facilitator based in London and Slough. Currently Artist in Residence for poetry collective EMPOWORD, Desree explores intersectionality, justice and social commentary. Producer for both Word Up and Word Of Mouth, finalist in 2018’s Hammer & Tongue national final and TEDx speaker, she has featured at events around the UK and internationally, including Glastonbury Festival 2019, Royal Albert Hall and Bowery Poetry New York. Burning Eye Publishers republished Desree’s first pamphlet, I Find My Strength In Simple Things, in May 2021.

Alex Dayo comes from Burkina Faso where his professional musical career started in the 1980’s, accompanying the National Ballet Kouledafourou on tour as well as playing for African Royalty and globally recognised dignitaries at private and public events and the Ensemble des Radios and Televisions of Burkina Faso, based in Bobo-Dioulasso. In 1985, he founded Wountey, a collective of musicians who created a new fusion of traditional and modern music called Plenguedey, and, for fifteen years, toured across Africa and Europe, spreading Burkina Faso’s cultural fusion to a wider audience. His musical collaborations include Ali Farka Toure, Femi Kuti and Salif Keita from Africa and traditional Master Griots from Burkina Faso/Mali/Guinea/Gambia. An accomplished arranger, Alex incorporates African traditional, Fusion, Jazz, Rock, Latin and Caribbean influences. Alex moved to London in 2007, where he set up a drumming school. A highlight of Alex’s career was being chosen to play at the Opening and Closing ceremonies at the London 2012 Olympics.

http://drummingschool.co.uk/zantogola

DESIGN & DEVELOPMENT

Studio Hyte is an award-winning design studio, working between graphic design, interaction, and emergent communication. Their work includes branding, print, website, installation, and exhibition design. Specializing in forward-thinking, multifaceted visual identities within the arts and education sector. Whether through commissioned or self-directed projects, they aim to create meaningful, accessible, and thought-provoking work.

Formed of a small group of individual practitioners, Studio Hyte is the middle ground where all of our interests and practices meet. Their collective practice and research cover a broad spectrum of topics including language, inclusion & accessibility, egalitarian politics & alternative protest, and technology & the human.

IG: @studiohyte

In 2019 we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Finsbury Park, and we time travel through its past and future with the launch of our Citizen Sci-fi programme and methodology. Dominant sci-fi franchises of our time, from Black Mirror to Westworld, have captured popular attention by showing us their apocalyptic visions of futures made desperate by systems of dominance and despair.

What is African-American author, Octavia E. Butler’s prescription for despair? Sci-fi and persistence. Sci-fi as a tool for getting us off the beaten-track and onto more fertile ground, and persistent striving for more just societies.The 2015 book Octavia’s Brood honoured her work, with an anthology of sci-fi writings from US social justice movements and this inspired us to try a new artistic response to the histories and possible futures of Finsbury Park.

Furtherfield’s Citizen Sci-Fi methodology combines citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

Each artwork in the forthcoming exhibition invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

So where do we start? Last year we invited artists, academics and technologists to join us in forming a rebel alliance to fight for our futures across territories of political, cultural and environmental injustice. This year both our editorial and our exhibition programme are inspired by this alliance and the discoveries we are making together.

To kick off this year’s Time Portals programme at Furtherfield, in April we will host the launch and discussion around Jugaad Time, Amit Rai’s forthcoming book. This reflects on the postcolonial politics of what in India is called ‘jugaad’, or ‘work around’ and its disruption of the neoliberal capture of this subaltern practice as ‘frugal innovation’. Paul March-Russell’s essay Sci-Fi and Social Justice: An Overview delves into the radical roots and implications of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). This is a topic close to our hearts given our own recent exhibitions Monsters of the Machine and Children of Prometheus, inspired by the same book. Meanwhile we’ve been hosting workshops with local residents exploring our visions for Finsbury Park 150 years into the future. To get a flavour of these activities Matt Watkins’ has produced an account of his experience of the Futurescapes workshop at Furtherfield Commons in December 2018.

In May we will open the Time Portals exhibition which features several new commissions. These include Circle of Blackness by Elsa James. Through local historical research James will devise a composite character to embody the story of a black woman from the locality 150 years ago and 150 years in the future. James will perform a monologue that will be recorded and produced by hybrid reality technologist Carl Smith and broadcast as a hologram inside the Furtherfield Gallery throughout the summer. While Futures Machine by Rachel Jacobs is an Interactive machine designed and built through public workshops to respond to environmental change – recording the past and making predictions for the future while inspiring new rituals for our troubled times. Once built, the machine occupies Furtherfield Gallery, inviting visitors to play with it.

Time Portals opens on May 9th (2019) with other time traveling works by Thomson and Craighead, Anna Dumitriu and Alex May, Antonio Roberts and Studio Hyte. Visitors will be invited to participate in an act of radical imagination, responding with images, texts and actions that engage circular time, long time, linear time and lateral time in space towards a collective vision of Finsbury Park in 2169.

From April onwards, a world of activities, workshops with local families and their enriching noises, reviews, interviews and an array of experiences will unfold. Together we dismiss the dystopian nightmares and invite communities to join us in one of London’s first “People’s Parks” to revisit and recreate the future on our own terms together.

Marc Garrett will be interviewing Elsa James, about her artwork Circle of Blackness, and Amit Rai about his book Jugaad Time. Both will soon be featured on the Furtherfield web site.

A recent report on digital attitudes shows that while 50% of people in the UK say that the Internet has a positive impact on their lives, only 12% believe it has a positive impact on society.[1] Mark Zuckerberg’s recent failure to give a straight answer to questions about misuse of Facebook’s user data, illustrates a major problem.

Much has been made of the democratising effect of social media platforms. However, while more of us are encouraged to “have our say”, we have less influence over the important decisions that most affect our lives, our localities, and the ways in which our societies are organised. The owners of digital platforms from Facebook to Uber, answer to shareholders in private, rather than to citizens in public. It should therefore not surprise us when they manipulate, monetize and exploit users’ interactions, attitudes and behaviours for their own commercial and political interests.

This problem of privately owned social space is not one that can be resolved by consumer and state regulation alone. It is a wider societal issue that further reinforces to us at Furtherfield, the immense value of park spaces in which neighbours come together each day, renegotiating in public, the spirit of the place through a diverse mingling of purposes.

Over the last six years more than 50,000 people have encountered over 75 digital artworks that Furtherfield has brought to the park, working with international artists who reveal the invisible forces at play in machine and digital infrastructures. This summer Furtherfield extends its programmes beyond the Gallery and Commons venues into public green space of the park as we announce the first exhibitions, workshops and labs as part of Platforming Finsbury Park.

We are inviting park users to collaborate with us to transform the park into a public platform for cultural adventures, social inventions and reflections; to work with artists, hackers and academics from all backgrounds to rethink the social impact of technology and its flows on public spaces; and to bring local needs to the forefront in the context of planetary-scale techno-social advancements.

Currently showing at Furtherfield Gallery in the heart of Finsbury Park is the exhibition Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens: the Art of Eduardo Kac which is free and open to the public every day through May. The exhibition includes Lagoogleglyph, the third in a series of images as part of a global, networked artwork that takes the form of a pixelated bunny painted (in this instance) onto a field in the park, to be enjoyed by people on the ground and seen from Google Earth. In his essay Andrew Prescott, curator of the exhibition and Professor of Digital Humanities at Glasgow University revisits historic antagonisms between culture and technology prompted by reflections on the invention and imagination at play in Kac’s digital poetry.

Meanwhile families are joining artist Michael Szpakowski to use the very same satellite infrastructure to create GPS bunny drawings in his workshop series Let’s Fill the Park With Rabbits!

We hope that Platforming Finsbury Park will also start to flip some assumptions about who and what both art and technology are for. Over 180 languages are spoken in Finsbury Park. We want to make space for conversations and experiments with people from different backgrounds. Alongside the exhibition Andrew Prescott is also leading a series of public workshops on the theme of Digital Transformations promoting dialogue between and across diverse cultures.

In late May, we host Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival, a 3 day lab for artists, scientists and technologists dedicated to “the worker in an age of data and neurotechnologies”. From these will flow art commissions and collaborations towards our next exhibition in July.

Here you can read an interview with designer Ling Tan about the SUPERPOWER wearable technology workshops at Furtherfield Commons last summer in Finsbury Park. Ling tells us about how a group of young women from All Change Arts worked with her to devise activities and to learn about creating and interpreting data to themselves shape attitudes and behaviours. Dani Admis, curator of Playbour, continues this work later in the summer, exploring with local young women how they might effect change on their own terms, using the conceptual power tools of neuroscience.

Finally a provocation to Furtherfield from Simon Poulter, artist, technologist and producer of NetPark, the digital art park at Metal in Southend, who is working in partnership with us. He celebrates our commitment to the commons “as a real thing, worth our energy and stewardship, the point at which people do touch each other and listen.” He also issues a call to action…“It is time to invent another future, lest we will become the disrupted and not the disruptors.”

As Manuel Castells famously put it ‘The flows of power generate the power of flows, whose material reality imposes itself as a natural phenomenon that cannot be controlled or predicted… People live in places, power rules through flows’. [2] And in network society these flows often have the power to wash clean away communities’ ties, extracting value and flowing it to the private interests of absent and distant persons and bodies.

So our future mission grounds us in Finsbury Park, while maintaining our global reach. We are passionate and committed to multiple points of entry, bringing in consenting and diverging voices, to channel and circulate flows locally to generate the power to enact this public place together with verve.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

DOWNLOAD GALLERY HANDOUT

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

In his first solo show in the UK, pioneering media artist Eduardo Kac puts poetry into space in entirely new ways and prompts us to ask “How do words work? What happens if we look at them upside down or inside out? What kind of poem could be made by an astronaut in outer space? What has poetry got to do with green bunnies?”

Kac explores how digital and other technologies provide poets with new possibilities of sound, light and movement. Even space flight offers the poet opportunities. Kac moves the poem off the page and into action. He explores the poetic possibilities of technologies ranging from digital videos and holograms to DNA manipulation and space flight, liberating poetry from the constraints of the printed page.

You can experience poems by Kac in the three rooms of Furtherfield Gallery as well as outside in the park. Follow the rabbit-shaped drawings on the paths in the park to see Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens in Furtherfield Gallery and installed in the field nearby.

Kac’s most famous work is GFP Bunny (2000), in which a rabbit called Alba was created in a laboratory with a gene causing her to glow fluorescent green under blue light. The artist made The Alba Flag (2001), on the outside of the Gallery next to the entrance, to celebrate Alba. Kac’s work with Alba prompted him to create a wordless language called lagoglyphs that give new expression to the bunny.

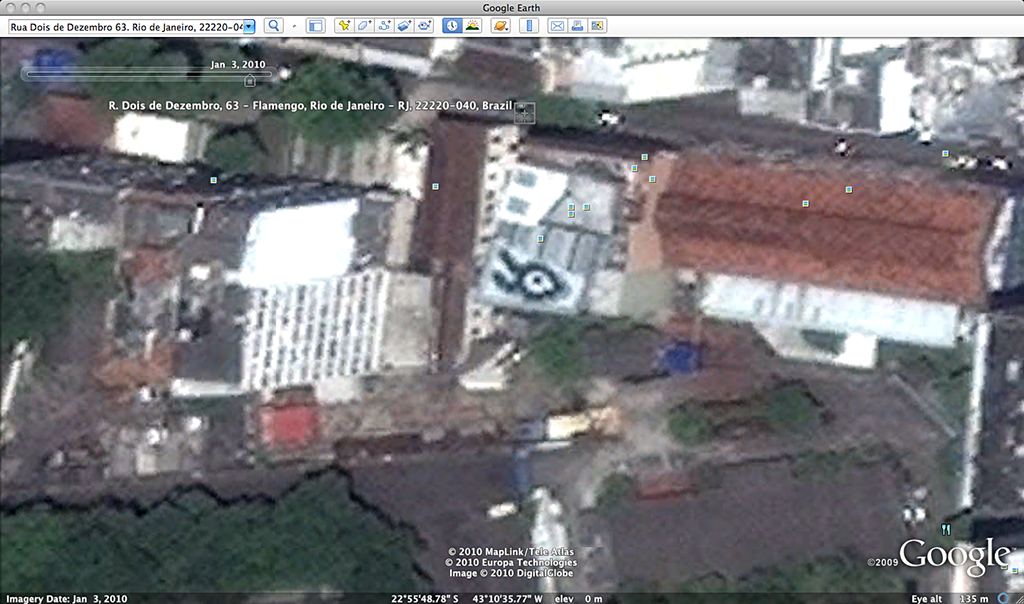

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Kac’s Lagoogleglyph, a work made for viewing from space. Covering a field in Finsbury Park it is optimised by Kac for viewing through satellite imagery and visible in Google Earth. The Lagoogleglyph is part of a series which forms a globally distributed artwork visible only from space. Earlier Lagoogleglyphs were installed at Oi Futuro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (in 2009) and Es Baluard Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Palma de Mallorca, Spain (in 2015).

Also featured in the exhibition:

In Adhuc (1991), holography alters our behaviour as readers. You cannot read the poem left to right. You must dance a little in front of it. As you do this, letters and words shift, drift away and colours change.

Inner Telescope (2017), performed by the French astronaut Thomas Pesquet in the International Space Station, is poetry for zero gravity. The form has neither top nor bottom, front or back, left or right. Sometimes it looks like the French word MOI (me). At other times, it looks like a human figure with the umbilical cord cut. It is the first poem to be made in outer space.

Let’s Fill this Park with Rabbits!

Free family Workshops

Sat 7 April, Sun 22 April & Mon 7 May, 11am – 4.30pm

Furtherfield Gallery

Families and groups of all ages are invited to join artist Michael Szpakowski to design their own giant rabbits and draw them on Finsbury Park by walking your own rabbit route using GPS software. Just turn up on the day to book a place for your group – workshop places will be offered on a first-come first-served basis on each day. Groups and families can also just turn up on each day to join in with the fun and walk some bunny routes in the park.

FREE

Arts and Humanities Research Council Digital Transformations Workshops

Inspired by and building on the Kac exhibition, these workshops will draw together themes and issues which have emerged from the AHRC thematic research programmes including Translating Cultures, Science in Culture, Care for the Future and Connected Communities.

More info

Digital Transformations and Community Engagement

18 April 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

How can we promote collaboration between communities and academic researchers? Do digital methods help create community engagement?

FREE | booking essential

Reconnecting Artistic Practice and Humanities Research

25 April 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

Can a renewed dialogue between humanities scholars and artistic practice provide innovative perspectives to confront current social and cultural challenges?

FREE | booking essential

Language and Diversity

8 May 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

Exploring the role of language and translation in promoting understanding and communication within, between, and across diverse cultures.

FREE | booking essential

Science in Culture

23 May 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

How can art engage with science and technology? And how can art explore the role of science in culture?

FREE | booking essential

Further Eduardo Kac exhibitions are being held in London during 2018 as part of the AHRC Digital Transformations theme. During June, the Horse Hospital, Colonnade, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1JD, will host an exhibition called … and the Bunny Goes Pop!

This exhibition forms part of research undertaken by the Digital Transformations strategic theme of the Arts and Humanities Research Council. It has been curated by Professor Andrew Prescott of the University of Glasgow with assistance from Furtherfield team and Bronac Ferran, with advice and support from the artist.

Eduardo Kac has been a pioneer in exploring the use of new technologies to create innovative poetic experiences. Experimenting with a range of technologies since the 1980s including fax, photocopiers, LED screens, the French videotext service Minitel, holography, conductive ink, and a variety of digital and network technologies. Kac’s distinctive body of work has been featured in exhibitions in New York, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, Madrid, Shanghai, Tokyo and many other venues. He has received the Golden Nica Award, the most prestigious award in the field of media arts and the highest prize awarded by Ars Electronica. This is his first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom.

Andrew Prescott, Professor of Digital Humanities at the University of Glasgow and Theme Leader Fellow for the ‘Digital Transformations’ strategic theme of the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Furtherfield is an internationally renowned arts organisation specialising in labs, exhibitions and debate for increased, diverse participation with emerging technologies. At Furtherfield Gallery and Furtherfield Lab in London’s Finsbury Park, we engage more people with digital creativity, reaching across barriers through unique collaborations with international networks of artists, researchers and partners. Through art Furtherfield seeks new imaginative responses as digital culture changes the world and the way we live.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

From the self-made celebrity of the Instafamous to the personal live-streaming of gamers, online sites of spectatorship are the emerging factories and playgrounds of the 21st century. We shop, share, and produce online, 24/7. As we do we alter the processes of how we work, what is viewed as a product, and our sense of self: work is like play and labour is seemingly without work. Playbour– Work, Pleasure, Survival, is dedicated to the study of the worker as they are asked to draw on internal resources and self-made networks to develop new avenues of work, pleasure and survival.

Over the three days we will form a community-led action research lab that brings together artists, researchers, data scientists, and activists, as well as community participants in an ambitious and intensive programme of experiments, interventions and performances. Led by a diverse community, and working towards a group exhibition at Furtherfield in July 2018, we will explore the converging spaces of work, play and well-being, as well as examine the role of the worker in the age of the Internet.

Playbour– Work, Pleasure, Survival, is an art and research platform dedicated to the study of the worker in an age of data technologies. Our first event is a three-day lab at Furtherfield Commons and we are currently welcoming submissions for people to join us!

We are looking for applications from a range of applicants artists, designers, researchers, curators, and activists, with an interest in the relationship between arts, technology, and design, and who are working on an art or research project relating to shifting realities of work, the worker, and the self, via cognitive capital, digital labour, play and entertainment spaces.

We will explore the contours and value systems we place on work, play, and well-being, and use this to work towards an exhibition at Furtherfield opening mid-July, 2018.

Each day will consist of three sessions DISCUSS, TEST, and PLAY, convened and co-led by artists, academics, designers, and activists. Participants will critically analyze and thoughtfully engage in conversations, conduct research with “workers”, test out ideas through hands-on making activities, and engage in play-driven interventions and performances. Then working in groups, develop the foundation for newly commissioned works for the upcoming exhibition at Furtherfield gallery in July 2018.

Friday 25 May, Playbour, will examine shifting realities of work and professionalism in play and entertainment spaces. Participants will DISCUSS with sociologist Dr. Jamie Woodcock (Oxford Internet Institute) and explore the concepts of playbour, digital labour, immaterial labour, and cognitive capitalism – linking these explicitly to work and play through the example of video games. We will then CONNECT with live streamers. In the afternoon, we will PLAY in a “collective empathy” session with artist Steven Ounanian looking into how pain and suffering are experienced in online contexts.

Saturday 26 May, Body/Machine/Capital, investigates data-driven decision making and the colonisation of body and machine via capital systems. The first half of the day will DISCUSS and TEST with special guests. Later that day participants will begin to develop their “game installation” projects.

Sunday 27 May, Unwitting Extraction, participants will DISCUSS and develop their “game installation” with architect Dr. Itai Palti. Using behavioural science and data technology participants will TEST ideas and thinking for game-based installations through a scientific lens in anticipation of the Furtherfield exhibition. This will be followed by a group lunch and feedback session with Dani Admiss and illustrator, Maz Hemming. To apply for a place please submit your application by midnight GMT Sunday 25 April 2018, to info@workpleasuresurvival.org

A complete application must include the following:

The lab has been organised with its partner Furtherfield Gallery as a pre-event to the Playbour– Work, Pleasure, Survival, exhibition opening in Friday 13 July 2018.Curated by Dani AdmissConcept development Dani Admiss and Cecilia Wee

Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival, is realized in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY).

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Furtherfield is delighted to announce the selection of Sarah Friend’s Clickmine for a new co-commission with NEoN Digital Arts Festival. The work will be exhibited Thursday – Sunday 9-12 November at NEoN Digital Arts Festival in Dundee.

Clickmine is a hyperinflationary ERC-20 token that is minted by a clicking game. Clicking games, like cookie clicker and cow clicker, are the reductio ad absurdum of a ‘game’ (brutalist with a sense of humour). Clickmine moves similar mechanics onto the blockchain, in a hypercapitalist frenzy that makes the generation of useless wealth via clicking more literal than ever before.

The cryptocurrency ecosystem, (particularly the Ethereum network), has been overrun by the phenomena of token sales or ICOs (Initial Coin Offerings). The fervor to purchase ERC-20 tokens (a meta currency that exists on top of Ethereum itself) has reached such an intensity that it stalls the processing time of the network. This has already prompted the creation of satirical coins UselessToken and Ponzicoin.

Clickmine was proposed by Friend in response to The CryptoDetectorist – hoards, coins and trades call for proposals from Furtherfield and NEoN Digital Arts Festival. While archaeology has often understood cultures through excavations of hoards and coins, we asked, what will today’s digital currencies tell future archaeologists about the way we live and trade?

This commission forms part of Furtherfield’s ongoing investigations into the politics of the blockchain, smart contracts, and cryptocurrency systems and NEoN Digital Arts Festival 2017 programme using ‘media archaeology’ to uncover and reconsider the obsolete, persistent, and hidden material cultures of the technological age. It will be launched online and presented at NEoN Digital Arts Festival in Dundee Scotland November 2017 then at the Digital Futures programme at V&A Museum and MoneyLab both in London in Spring 2018.

Friend is an artist and software engineer focused on the development of games, interactive experiences, and open source tools. Her work to-date has been concerned with the polar concerns of privacy and transparency, how to design ethical interfaces, and the political and environmental implications of technical systems.

She is currently working at a blockchain development studio on tools for accounting and analytics, while maintaining an art and game-making practice. Her work has recently been part of exhibitions at the British Public Library, The Center for Contemporary Art Tel Aviv, and Radical Networks, a conference in Brooklyn. She is a judge for Wordplay: the Festival of Writerly Games, exhibiting at Damage Camp, a games conference in Toronto, and presenting on the technical challenges of blockchain games at the Montreal International Games Showcase. Community organizations she is involved with include: Toronto Mesh, The Reported (a database of police-involved deaths in Canada), The Toronto Tool Library, and Dames Making Games.

Furtherfield

Through artworks, labs and debate around arts and technology, people from all walks of life explore today’s important questions. The urban green space of London’s Finsbury Park, where Furtherfield’s Gallery and Lab are located, is now a platform for fieldwork in human and machine imagination – addressing the value of public realm in our fast-changing, globally connected and uniquely superdiverse context. An international network of associates use artistic methods to interrogate emerging technologies to extend access and grasp their wider potential. In this way new cultural, social and economic value is developed in partnership with arts, research, business and public sectors.

NEoN

NEoN (North East of North) based in Dundee, Scotland aims to advance the understanding and accessibility of digital and technology driven art forms and to encourage high quality within the production of this medium. NEoN has organised 7 annual festivals to date including exhibitions, workshops, talks, conferences, live performances and public discussions. It is a platform to showcase national and international digital art forms. By bringing together emerging talent and well-established artists, NEoN aims to influence and reshape the genre. We are committed to helping our fabulous city of Dundee, well known for its digital culture and innovation, to become better connected through experiencing great art, networking and celebrating what our wee corner of Scotland has to offer in the field of digital arts.

State Machines: Art, Work and Identity in an Age of Planetary-Scale Computation

Focusing on how such technologies impact identity and citizenship, digital labour and finance, the project joins five experienced partners Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY) together with a range of artists, curators, theorists and audiences. State Machines insists on the need for new forms of expression and new artistic practices to address the most urgent questions of our time, and seeks to educate and empower the digital subjects of today to become active, engaged, and effective digital citizens of tomorrow.

V&A Digital Futures: Digital Futures

V&A Digital Futures: Digital Futures is a monthly meetup and open platform for displaying and discussing of work by professionals working with art, technology, design, science and beyond. It is also a networking event, bringing together people from different backgrounds and disciplines with a view to generating future collaborations.

Creative Scotland

Creative Scotland is the public body that supports the arts, screen and creative industries across all parts of Scotland on behalf of everyone who lives, works or visits here. It enables people and organisations to work in and experience the arts, screen and creative industries in Scotland by helping others to develop great ideas and bring them to life. It distributes funding from the Scottish Government and The National Lottery.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

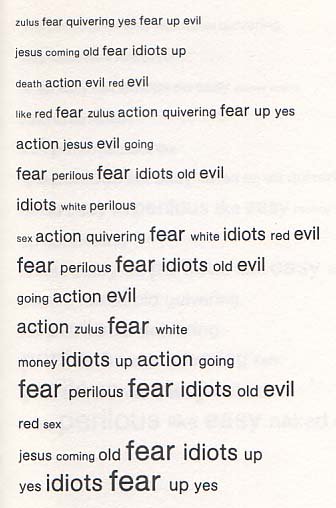

“Your work is so Dada, its just weird…” Even though the sentence was uttered playfully and with no foul intentions, it hit me. It sounded dismissive; in my ears, my friend just admitted disinterest. Calling something “weird” suggests withdrawal. The adjective forecloses a sense of urgency and classifies the work as a shallow event: the work is funny and quirky, slightly odd and soon becomes background noise, ’nuff said. I tried to ignore the one word review, but I will never forget when it was said, or where we were standing. I wish I had responded: “I think we already know too much to make art that is weird.” But unfortunately, I kept quiet.

In his book Noise, Water, Meat (1999), Douglas Kahn writes: “We already know too much for noise to exist.” A good 15 years after Kahn’s writing, we have entered a time dominated by the noise of crises. Hackers, disease, trade stock crashes and brutalist oligarchs make sure there is not a quiet day to be had. Even our geological time is the subject to dispute. But while insecurity dictates, no-one would dare to refer to this time as the heyday of noise. We know there is more at stake than just noise.

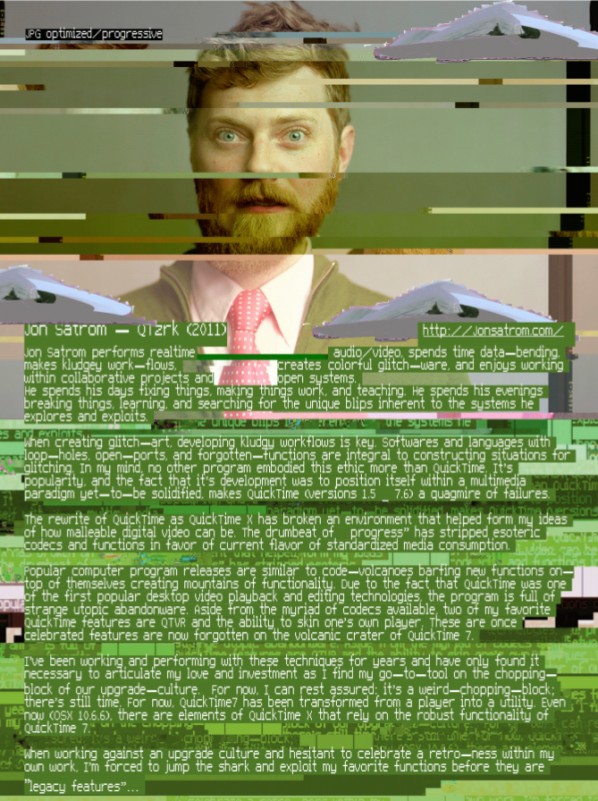

This state is reflected in critical art movements: a current generation of radical digital artists is not interested in work that is uninformed by urgency, nor can they afford to create work that is just #weird, or noisy. The work of these artists has departed from the weird and exists in an exchange that is, rather, strange. it invites the viewer to approach with inquisitiveness – it invokes a state of mind: to wonder. Consequently, these works break with tradition and create space for alternative forms, language, organisation and discourse. It is not straightforward: it is the art of creative problem creation(Jon Satrom during GLI.TC/H).

In 2016 it is easy to look at the weird aesthetics of Dada; its eclectic output is no longer unique. The techniques behind these gibberish concoctions have had a hundred years to become cultivated, even familiar. Radical art and punk alike have adopted the techniques of collage and chance and applied them as styles that are no longer inherently progressive or new. As a filter subsumed by time and fashion, Dada-esque forms of art have been morphed into weird commodities that invoke a feel of stale familiarity.

But when I take a closer look at an original Dadaist work, I enter the mind of a stranger. There is structure that looks like language, but it is not my language. It slips in and out of recognition and maybe, if I would have the chance to dialogue or question, it could become more familiar. Maybe I could even understand it. Spending more time with a piece makes it possible to break it down, to recognize its particulates and particularities, but the whole still balances a threshold of meaning and nonsense. I will never fully understand a work of Dada. The work stays a stranger, a riddle from another time, a question without an answer. The historical circumstances that drove the Dadaists to create the work, with a sentiment or mindset that bordered on madness, seems impossible to translate from one period to the next. The urgency that the Dadaists felt, while driven by their historical circumstances, is no longer accessible to me. The meaningful context of these works is left behind in another time. Which makes me question: why are so many works of contemporary digital artists still described—even dismissed—as Dada-esque? Is it even possible to be like Dada in 2016?

The answer to this question is at least twofold: it is not just the artist, but also the audience who can be responsible for claiming that an artwork is a #weird, Dada-esque anachronism. Digital art can turn Dada-esque by invoking Dadaist techniques such as collage during its production. But the work can also turn Dada-esque during its reception, when the viewer decides to describe the work as “weird like Dada.” Consequently, whether or not today a work can be weird like Dada is maybe not that interesting; the answer finally lies within the eye of the beholder. It is maybe a more interesting question to ask what makes the work of art strange? How can contemporary art invoke a mindset of wonder and the power of the critical question in a time in which noise rules and is understood to be too complex to analyse or break down?

The Dadaists invoked this power by using some kind of ellipsis (…): a tactic of strange that involves the withholding of the rules of that tactic. They employed a logic to their art that they did not share with their audience; a logic that has later been described as the logic of the madmen. Today, in a time where our daily reality has changed and our systems have grown more complex, the ellipses of mad logic (dysfunctionality) are commonplace. Weird collage is no longer strange; it is easily understood as a familiar aesthetic technique. Radical Art needs a provocative element, an element of strange that lures the viewer in and makes them think critically; that makes them question again. The art of wonder can no longer lie solely in ellipsis and the ellipsis can no longer be THE art.

This is particularly important for digital art. During the past decades, digital art has matured beyond the Dadaesque mission to create new techniques for quaint collage. Digital artists have slowly established a tradition that inquisitively opens up the more and more hermetically closed—or black boxed—technologies. Groups and movements like Critical Art Ensemble (1987), Tactical Media (1996), Glitch Art (since ±2001, and later a subgenre that is sometimes referred to as Tactical Glitch Art) and #Additivism (2015) (to name just a few) work in a reactionary, critical fashion against the status quo, engaging with the protocols that facilitate and control the fields of, for instance, infrastructure, standardization, or digital economies. The research of these artists takes place within a liminal space, where it pivots between the thresholds of digital language, such as code and algorithms, the frameworks to which data and computation adhere and the languages spoken by humans. Sometimes they use tactics that are similar to the Dadaist ellipsis. As a result, their output can border on Asemic. This practice comes close to the strangeness that was an inherent component of an original power of Dadaist art.

But an artist who still insists on explaining why a work is weirdly styled like Dada is missing out on the strange mindset that formed the inherently progressive element of Dada. Of course a work of art can be strange by other means than the tactics and techniques used in Dada. Dada is not the father of all progressive work. And not all digital art needs to be strange. But strange is a powerful affect from which to depart in a time that is desperate to ask new critical questions to counter the noise.

Thanks to Amy J. Elias and Jonathan P. Eburne

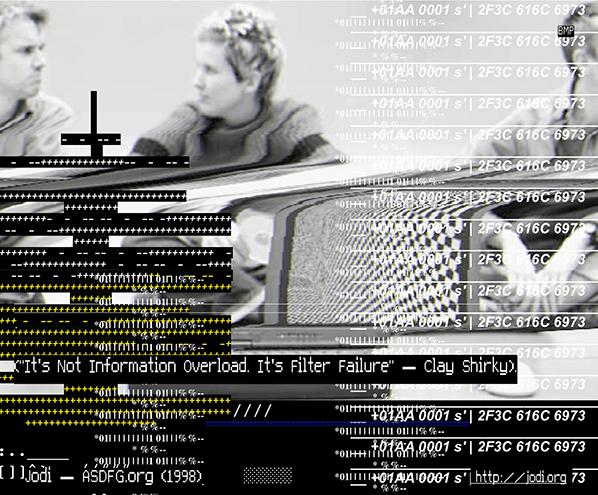

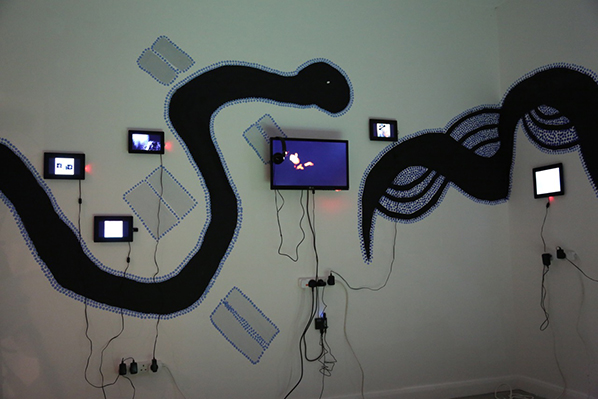

NotesImages in this article are part of the exhibition Filtering Failure curated by Julian van Aalderen and Rosa Menkman in 2011.

Catalogue of exhibition here:

http://www.slideshare.net/r00s/filtering-failure-exhibition-catalogue

In this special feature Steve Jampijimpa Patrick writes about YAMA, the name given to the installation currently on display as part of the exhibition Networking the Unseen at Furtherfield Gallery.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

I want to tell you about YAMA. This is the Warlpiri word for a shadow, or reflection. It’s also a word that we use to describe a meeting or a meeting-place; we gather under a tree that casts a shadow (a reflection of its shape) onto the ground, and we talk in a group – both men and women together, equally – to make decisions and to reflect on ourselves and our lives. But it’s deeper, too. In yapa (Aboriginal) culture, if someone says “you don’t have a shadow”, it means you don’t exist. All the birds, all the small animals, trees – these things all have a shadow; all of your country and everything in it; this is your universe. How can you reflect your universe? And what about you, reader? Does your homeland reflect you?

I’ve been all over the world, searching for ngurra kurlu (the home within). Each country’s, each people’s ngurra kurlu is different. If you don’t speak your language, if you don’t know your culture, the songlines of the animals in your country, how can you express yourself or where you’re from? This reflection happens through language, through dance, art, even food – that’s ngurra kurlu. There is a universe and we are its shadow.

We yapa say “don’t become Australian, become Australia”.

That’s ngurra kurlu.

I am writing this from Germany, we (Neil Jupurrurla Cooke and I) were in England for a week working on YAMA, a multimedia installation with Napanangka (Gretta Louw) for the Networking the Unseen exhibition at Furtherfield. Every day we walked through Finsbury Park and the people we saw were really alive there, playing, walking, school children running through, watching the birds and the squirrels. But when we go into town, we feel closed up again. We went to the Horse Guard. Where I come from, the horses roam free – they are really alive. We don’t know their skin name , we don’t have a song for them because they’re feral animals, brought into our country by kardiyah (white people) – but they’re free. When we see the horses there in London trained to stand still like that, like they’re stone, we feel sad for them.

Then we look around and see those buildings round there (in Westminster). We’ve seen those buildings before. Even though we’d never been to London. They’re like underwater, you know, that coral when it dies – when it’s bleached – that’s what those buildings are like. Every thing, both living and created by the living, is a reflection of our universe. Imagine you are a little ant and you are walking through tombstones – this is how it feels for us to be in that place. I guess the people that made those towers are trying to express power, they want to have power over other people. They build those bleached towers and statues tall on columns to make the other people feel small. That’s a crazy world, when I’m coming at it from my culture.

Your home is going to reflect you and you’re going to reflect your home. So, think about your home and what it says about you.

For us, the things we look up at are the stars. We’ve always known them and learned from them. They are part of our ngurra kurlu. What about that North star that you have here in the northern hemisphere – they say it doesn’t move. Maybe that’s why you have one leader, one queen, who doesn’t change. Down in Australia, we have five emus (the southern cross) – we live by that law. We call ourselves an emu country. You bear countries reflect your stars, too. I like to think that the queen is the ultimate kurlungu (guardian) for the country, but a kurlungu needs to really look after all their people and their country. Is that what’s happening in your country?

I wonder what would happen if you brought an emu up here and just let it walk around. I’ve never seen it but I think it might start heading south. We have a word for ocean, mangku-rla, even though we’re a desert mob. This shows how ancient our songlines are – they existed before us; they created us. We were supposed to be noble savages, from the settlers’ point of view we weren’t supposed to know about the ocean or what was on the other side, but our Emu Dreaming tells the story of the emu swimming across the ocean. He was a nervous emu because he was being chased into the water by dogs. I think that was when the emu went between the continents to make relations with the ostrich and the rhea bird and the moa. There were big, flightless birds like the emu on each of the continents. In the Jardiwanpa story, the emu comes out of the water and shakes himself like a dog. This is reflected in the stars as well; our emu stars (the English name is the Milky Way) come up after the wet season.

In yapa culture, we know that we didn’t create the body: our universe, our country created us. That’s why I am a black man from Australia – my country made me like this. This is what you call evolution. You can have bears in the north, and we have emus in the south. Our countries created those beings. Yapa have always known that this is how things are created.

You live in the bear countries; even without people knowing it, they are reflecting what the bear is trying to teach them. We live by the emu. I can’t tell you what the bear is teaching you, I’d need to live here a lot longer, but you can learn to hunt the knowledge that the bear is trying to show you.

There are food sources for your stomach and there are some for your mind. Both are equally important. If you are hunting for goanna you bring it home and share it with your family and your community. If you are sitting, talking, learning that’s also hunting – you are hunting knowledge and you bring it home and share it with your people. The mind and the physical reflect each other – that’s yama.

The Australian coat of arms is meaningful to us, even though we weren’t asked to choose it. The emu is our teacher, wise and kind, and the kangaroo is like a warrior or a judge, strong and powerful. The nature of our land, our country, is reflected in this coat of arms. When I look at the English coat of arms, I see a lion and a unicorn. Do these animals come from your country? What does this coat of arms represent and what does it reflect about your country?

When I ask you to help me hunt the unicorn, will you understand what I mean?

Hunting the unicorn is a way to understand its ngurra kurlu, to try to understand the country and therefore to understand the people. After all, if you’re hunting something, you have to learn to think like the animal that you’re hunting. It’s a way to fit into the country and to feed on that country; that country nourishes you. That’s the most important skill you can have. It’s a skill to understand the prey, and to think like the prey. It’s something I never understood before. But now I do.

If you know how to reflect yourself, you can then reflect other people. Don’t try to do it back to front.

Calling 13-18 year-olds!

Become a digital media artist. Design your own digital game, make a robot, or design a selfie app. Create small ‘geocached’ artwork for people to find in Finsbury Park, or narrate an audio guide for gallery visitors. Meet and learn with leading artists, and at the end of the programme you can keep your own ‘Raspberry Pi’ pocket computer

FREE, booking essential, limited places so BOOK HERE NOW

For more information contact: alicia.furtherfield@gmail.com

Young Digital Artists in Residence: Adventures in Art and Technology is part of Islington Council’s Summerversity programme.

Featured image: Aram Bartholl, Forgot Your Password?, 2013

Historical art is developed by way of its respective era and society, meaning that it is always made in the present. Today, new technologies open up new possibilities for artistic potential. Currently, art production, which is influenced by new technologies, is reacting strongly to the changing times. Artworks are being created, which react to digitalisation, even if they don’t necessarily reflect the digital format itself (i.e. like works by Aram Bartholl).

In its purest form, digital art is ephemeral and based on a transient technology. The continual advancement of the technology demands on-going improvements; challenges from which many emerging artists refuse to be deterred. On the contrary: the monthly quota of events related to digital art proves the high level of interest around the form.

The global technical networks thereby bring about new atmospheres, or perhaps, infospheres, as media theorist Peter Weibel calls them. In the art world, previously held art-historical considerations are forced towards a re-evaluation. Conventional theories and practices must be called into question. New art forms in the immaterial digital domain demand a general rethink in terms of their conservation, presentation and acquisition. And, of course, the reception of digital art is also different.

According to studies by Hiscox, a preference for original works still dominates both in conventional and online trade. Authenticity and intrinsic value continue to be important criteria when it comes to decision-making regarding the purchase of art. Transparency will remain, for the long term, a fundamental prerequisite for the establishment of trust.

Most acquisitions of digital art take place conventionally by way of galleries. If a collector acquires, for example, a website, then the gallerist sells he or she a domain (which is unique!) and transfers in-addition, a licence contract. This is a material document. The ‘network’ remains virtual, while retaining open all of the attributes of an artwork in the source code, i.e. the artist’s signature, the title, the year in which it was produced, the technique, and information on the programmer or the collector.

The collector can enjoy the work beyond the confines of time and physical location. Simultaneously, he or she is responsible for its preservation, which is the guarantee for the continuation of its existence over time.

Internet art in general is dependant on software, but above all it relies on hardware (computer, hard-drive, interfaces, sensors, monitors, projectors, etc.). Yet for how long will the hardware remain a part of our interactive culture? Forward-looking collectors purchase, in addition to the contract, a series of devices that safeguard the work for the future.

The ability to learn about new approaches in our fast-moving culture occurs both naturally and dynamically. The art market is an extremely non-transparent market, access to the right networks and contacts. Is this likely to change any time soon?

Art history shows us that artists are ahead of their time, anticipating what is to come. One need only cast an eye around the scene, in order to open the door to new ideas and technological marketing methods in the art world.

The German artist, Stephan Vogler, has already done this and in cooperation with a law firm has unleashed intelligent synergies. The artist himself produces digital files – intangible goods, as he calls them – which should also naturally migrate to the art market over the long-term, in the best case scenario, as unique pieces which one – such is the thinking within his system – can acquire with Bitcoin.

Far more interesting than the means of purchase, is the Bitcoin technology that lies behind it.

Stephan Vogler has developed a licence together with experts on legal practice within the art world, which transforms the digital artwork into an independently tradable virtual commodity, which is limited, both in terms of its technology and its legal rights. The system is based on a license agreement under the utilization of the Bitcoin technology. All works will come with an electronic signature, which is recognized, in legal terms, as being an original signature. This also serves as proof that the files existed at a given moment in time. Their authenticity is mathematically verifiable and the right of resale is exclusive. Virtual ownership is technically and legally limited to the respective owner. The owner of the usage rights is registered in a decentralized Bitcoin Blockchain, and the rights regarding the work are assigned through a Bitcoin transaction. In this way, digital artworks become both tradable and collectable objects without the requirement of their materialisation. Purchase and transaction take place simultaneously and the function of the custodian is eliminated. The structure behind the acquisition is thereby extremely transparent.

Artists like Stephan Vogler want to revolutionize the market for digital art through new technology. But independent from this fact, the art world is not sleeping. Collectors, institutions and art market platforms are already taking note.

For example, Austria’s Museum for Modern Art (MAK) has already bought an artwork with Bitcoin.

Cointemporary.com, a curated online platform, offers ephemeral artworks at a fixed Bitcoin (BTC) price – independent from the actual exchange rate. Berlin company ascribe.io develops systems within the Blockchain technology and offers services for art experts, assisting in the professional management of their digital files, i.e. their registration, archival, transfer of ownership etc.

The Winklevoss twins are known as great advocates of the digital currency. Rumours about investments in the art form are rife.

The acquisition of artworks via Bitcoin sounds forward-looking and simple yet should be enjoyed with a good degree of care. The reason for this is that Bitcoin is not controlled by a state and its central bank, but rather is generated by Internet users by way of complicated arithmetic calculations. So what might be the advantage of a Bitcoin purchase?

Collectors of digital art, such as the Belgian, Alain Servais, or Hampus Lindwall, from Sweden, view the purchase of work via the risky Bitcoin currency with scepticism.

It is still too early to really be able to judge the effects of these developments. Ultimately, the discussion as a whole concentrates far less on the system of currency than on the technology itself, which can also be applied to other circumstances. These experiments will only truly bear fruit through the development of a high degree of know-how, the courage to take on legal consequences at the moment of purchase, and through simple decisions in a user-friendly design.

Daniel Rourke: At Furtherfield on November 22nd 2014 you launched a Beta version of a networked project, 6PM Your Local Time, in collaboration with Fabio Paris, Abandon Normal Devices and Gummy Industries. #6PMYLT uses twitter hashtags as a nexus for distributed art happenings. Could you tell us more about the impetus behind the project?

Domenico Quaranta: In September 2012, the Link Art Center launched the Link Point in Brescia: a small project space where, for almost two years, we presented installation projects by local and international artists. The Link Point was, since the beginning, a “dual site”: a space where to invite our local audience, but also a set for photographic documentation meant to be distributed online to a global audience. Fabio Paris’ long experience with his commercial gallery – that used the same space for more than 10 years, persuaded us that this was what we had to offer to the artists invited. So, the space was reduced to a small cube, white from floor to ceiling, with neon lights and a big logo (a kind of analogue watermark) on the back door.

Thinking about this project, and the strong presence of the Link Point logo in all the documentation, we realized that the Link Point was actually not bound to that space: as an abstract, highly formalized space, it could actually be everywhere. Take a white cube and place the Link Point logo in it, and that’s the Link Point.

This realization brought us, on the one hand, to close the space in Brescia and to turn the Link Point into a nomad, erratic project, that can resurrect from time to time in other places; and, on the other hand, to conceive 6PM Your Local Time. The idea was simple: if exhibition spaces are all more or less similar; if online documentation has become so important to communicate art events to a wider audience, and if people started perceiving it as not different from primary experience, why not set up an exhibition that takes place in different locations, kept together only by documentation and by the use of the same logo? All the rest came right after, as a natural development from this starting point (and as an adaptation of this idea to reality).

Of course, this is a statement as well as a provocation: watching the documentation of the UK Beta Test you can easily realize that exhibition spaces are NOT more or less the same; that attending or participating in an event is different from watching pictures on a screen; that some artworks work well in pictures but many need to be experiences. We want to stress the value of networking and of giving prominence to your network rather than to your individual identity; but if the project would work as a reminder that reality is still different from media representation, it would be successful anyway.

Daniel Rourke: There is something of Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zones in your proposal. The idea that geographic, economic and/or political boundaries need no longer define the limits of social collective action. We can criticise Bey’s 1991 text now, because in retrospect the Internet and its constitutive protocols have themselves become a breeding ground for corporate and political concerns, even as technology has allowed ever more distributed methods of connectivity. You foreground network identity over individual identity in the 6PM YLT vision, yet the distinction between the individuals that create a network and the corporate hierarchies that make that networking possible are less clear. I am of course gesturing towards the use of Twitter as the principal platform of the project, a question that Ruth Catlow brought up at the launch. Do you still believe that TAZs are possible in our hyper-connected, hyper-corporate world?

Domenico Quaranta: In its first, raw conceptualization, 6PM YLT had to come with its own smartphone app, that had to be used both to participate in the project and to access the gallery. The decision to aggregate content published on different social platforms came from the realization that people already had the production and distribution tools required to participate in the action, and were already familiar with some gestures: take a photo, apply a filter, add an hashtag, etc. Of course, we could invite participants and audiences to use some specific, open source social network of our choice, but we prefer to tell them: just use the fucking platform of your choice. We want to facilitate and expand participation, not to reduce it; and we are not interested in adding another layer to the project. 6PM YLT is not a TAZ, it’s just a social game that wants to raise some awareness about the importance of documentation, the power of networks, the public availability of what we do with our phones. And it’s a parasitic tool that, as anything else happening online, implies an entire set of corporate frameworks in order to exist: social networks, browsers, operative systems, internet providers, server farms etc.

That said, yes, I think TAZs are still possible. The model of TAZ has been designed for an hyper-connected, hyper-corporate world; they are temporary and nomadic; they exist in interstices for a short time. But I agree that believing in them is mostly an act of faith.

Daniel Rourke: The beta-tested, final iteration of 6pm YLT will be launched in the summer of 2015. How will you be rolling out the project in the forthcoming months? How can people get involved?

Domenico Quaranta: 6PM Your Local Time has been conceived as an opportunity, for the organizing subject, to bring to visibility its network of relationships and to improve it. It’s not an exhibition with a topic, but a social network turned visible. To put it simply: our identity is defined not just by what we do, but also by the people we hang out with. After organizing 6PM Your Local Time Europe, the Link Art Center would like to take a step back and to offer the platform to other organizing subjects, to allow them to show off their network as well.

So, what we are doing now is preparing a long list of institutions, galleries and artists we made love with in the past or we’d like to make love with in the future, and inviting them to participate in the project. We won’t launch an open call, but we already made the event public saying that if anyone is interested to participate, they are allowed to submit a proposal. We won’t accept anybody, but we would be happy to get in touch with people we didn’t know.

After finalizing the list of participants, we will work on all the organizational stuff, basically informing them about the basic rules of the game, gathering information about the events, answering questions, etc.

On the other hand, we have of course to work on the presentation. While every participant presents an event of her choice, the organizer of a 6PM Your Local Time event has to present to its local audience the platform event, as an ongoing installation / performance. We are from Brescia, Italy, and that’s where we will make our presentation. We made an agreement with MusicalZOO, a local festival of art and electronic music, in order to co-produce the presentation and have access to their audience. This is what determined the date of the event in the first place. Since the festival takes place outdoor during the summer, we are working with them on designing a temporary office where we can coordinate the event, stay in touch with the participants, discuss with the audience, and a video installation in which the live stream of pics and videos will be displayed. Since we are expecting participants from Portugal to the Russian Federation, the event will start around 5 PM, and will follow the various opening events up to late night.

One potential reference for this kind of presentation may be those (amazing) telecommunication projects that took place in the Eighties: Robert Adrian’s The World in 24 Hours, organized at Ars Electronica in 1982; the Planetary Network set up in 1986 at the Venice Biennale; and even Nam June Paik’s satellite communication project Good Morning Mr Orwell (1984).

Daniel Rourke: Your exhibition Unoriginal Genius, featuring the work of 17 leading net and new media artists, was the last project to be hosted in the Carroll/Fletcher Project Space (closing November 22nd, 2014). Could you tell us more about the role you consider ‘genius’ plays in framing contemporary art practice?

Domenico Quaranta: The idea of genius still plays an important role in Western culture, and not just in the field of art. Whether we are talking about the Macintosh, Infinite Jest, a space trip or Nymphomaniac, we are always celebrating an individual genius, even if we perfectly know that there is a team and a concerted action behind each of these things. Every art world is grounded in the idea that there are gifted people who, provided specific conditions, can produce special things that are potentially relevant for anybody. This is not a problem in itself – what’s problematic are some corollaries to our traditional idea of genius – namely “originality” and “intellectual property”. The first claims that a good work of creation is new and doesn’t depend on previous work by others; the second claims that an original work belongs to the author.

In my opinion, creation never worked this way, and I’m totally unoriginal in saying this: hundreds of people, before and along to me, say that creating consists in taking chunks of available material and assembling them in ways that, in the best situation, allow us to take a small step forward from what came before. But in the meantime, entire legal systems have been built upon such bad beliefs; and what’s happening now is that, while on the one hand the digitalization of the means of production and dissemination allow us to look at this process with unprecedented clarity; on the other hand these regulations have evolved in such a way that they may eventually slow down or stop the regular evolution of culture, which is based on the exchange of ideas.

We – and creators in particular – have to fight against this situation. But Unoriginal Genius shouldn’t be read in such an activist way. It is just a small attempt to show how the process of creation works today, in the shared environment of a networked computer, and to bring this in front of a gallery audience.

Daniel Rourke: So much online material ‘created’ today is free-flowing and impossible to trace back to an original author, yet the tendency to attribute images, ideas or ‘works’ to an individual still persists – as it does in Unoriginal Genius. I wonder whether you consider some of the works in the show as more liberated from authorial constraints than others? That is, what are the works that appear to make themselves; floating and mutating regardless of particular human (artist) intentions?

Domenico Quaranta: Probably Museum of the Internet is the one that fits best to your description. Everybody can contribute anonymously to it by just dropping images on the webpage; the authors’ names are not available on the website, and there’s no link to their homepage. It’s so simple, so necessary and so pure that one may think that it always existed out there in some way or another. And in a way it did, because the history of the internet is full of projects that invite people to do more or less the same.

Daniel Rourke: 2014 was an exciting year for the recognition of digital art cultures, with the appointment of Dragan Espenschied as lead Digital Conservator at Rhizome, the second Paddles On! auction of digital works in London, with names like Hito Steyerl and Ryan Trecartin moving up ArtReview’s power list, and projects like Kenneth Goldsmith’s ‘Printing out the Internet’ highlighting the increasing ubiquity – and therefore arguable fragility – of web-based cultural aggregation. I wondered what you were looking forward to in 2015 – apart from 6PM YLT of course. Where would you like to see the digital/net/new media arts 12 months from now?

Domenico Quaranta: On the moon, of course!

Out of joke: I agree that 2014 has been a good year for the media arts community, as part of a general positive trend along the last few years. Other highlighs may include, in various order: the September 2013 issue of Artforum, on “Art and Media”, and the discussion sparked by Claire Bishop’s essay; Cory Arcangel discovering and restoring lost Andy Warhol’s digital files from floppy disks; Ben Fino-Radin becoming digital conservator at MoMA, New York; JODI winning the Prix Net Art; the Barbican doing a show on the Digital Revolution with Google. Memes like post internet, post digital and the New Aesthetic had negative side effects, but they helped establishing digital culture in the mainstream contemporary art discourse, and bringing to prominence some artists formerly known as net artists. In 2015, the New Museum Triennial will be curated by Lauren Cornell and Ryan Trecartin, and DIS has been announced to be curator of the 9th Berlin Biennial in 2016.

All this looks promising, but one thing that I learned from the past is to be careful with optimistic judgements. The XXI century started with a show called 010101. Art in Technological Times, organized by SFMoMA. The same year, net art entered the Venice Biennale, the Whitney organized Bitstreams and Data Dynamics, the Tate Art and Money Online. Later on, the internet was announced dead, and it took years for the media art community to get some prominence in the art discourse again. The situation now is very different, a lot has been done at all levels (art market, institutions, criticism), and the interest in digital culture and technologies is not (only) the result of the hype and of big money flushed by corporations unto museums. But still, where we really are? The first Paddles On! Auction belongs to history because it helped selling the first website ever on auction; the second one mainly sold digital and analogue paintings. Digital Revolution was welcomed by sentences like: “No one could fault the advances in technology on display, but the art that has emerged out of that technology? Well, on this showing, too much of it seems gimmicky, weak and overly concerned with spectacle rather than meaning, or making a comment on our culture.” (The Telegraph) The upcoming New Museum Triennial will include artists like Ed Atkins, Aleksandra Domanovic, Oliver Laric, K-HOLE, Steve Roggenbuck, but Lauren and Ryan did their best to avoid partisanship. There’s no criticism in this statement, actually I would have done exactly the same, and I’m sure it will be an amazing show that I can’t wait to see. Just, we don’t have to expect too much from this show in terms of “digital art recognition”. So, to put it short: I’m sure digital art and culture is slowly changing the arts, and that this revolution will be dramatic; but it won’t take place in 2015 🙂

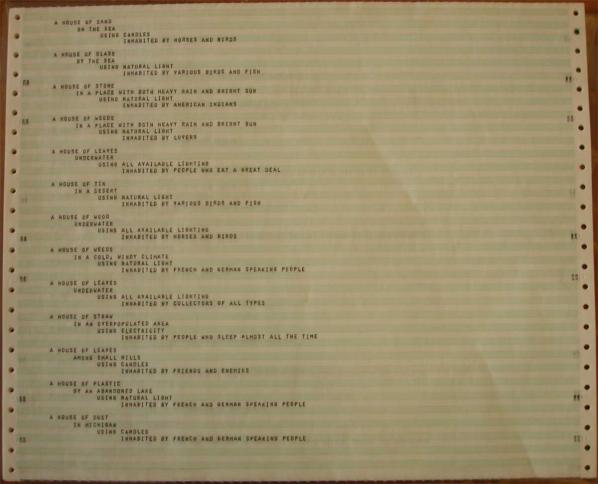

Mainframe Experimentalism

Early Computing And The Foundations Of The Digital Arts

Edited by Hannah B Higgins and Douglas Kahn

University of California Press, 2012

ISBN 978-0-520-26838-8

The history of arts computing’s heroic age is a family affair in Hannah B Higgins and Douglas Kahn’s Mainframe Experimentalism. Starting with the founding legend of the FORTRAN programming workshops that one of the editors’ parents led in their New York apartment in the 60s, the book quickly broadens across continents and decades to cover the mainframe and minicomputer period of digital art. Several of the chapters are also written by children of the artists. Can they make the case that the work they grew up with is of wider interest and value?

The 1960s and 1970s were the era prior to the rise of home and micro computing, when small computers weighed as much as a fridge (before you added any peripherals to them) and large computers took up entire air conditioned offices. Mainframes cost millions of dollars, minicomputers tens of thousands at a time when the average weekly wage was closer to a hundred dollars. To access a computer you had to engage with the institutions that could afford to maintain them – large businesses and universities, and with their guardians – the programmers and system administrators who knew how to encode ideas as marks on punched cards for the computer to run.

Computers looked like unlikely tools or materials for art. The governmental, corporate and scientific associations of computers made them appear actively opposed to the individualistic and humanistic nature of mid-20th Century art. It took an imaginative leap to want to use, or to encourage others to use, computers in art making.

Flowchart for asking your boss for a raise, Georges Perec

Many people were unwilling or unable to make that leap. As Grant Taylor describes in The Soulless Usurper, “Almost any artistic endeavor(sic) associated with early computing elicited a negative, fearful, or indifferent response”(p.19). The idea, or the cognates, of computing were as powerful a force in culture as any access to actual computer hardware, a point that David Bellos makes with reference to the pataphysical bureaucratic dramas of Georges Perec’s Thinking Machines. Those wider cultural ideas, such as structuralism, could provide arts computing with the context that it sorely lacked in most people’s eyes as Edward A. Shanken argues in his discussion of the ideas behind Jack Burnham’s “Software” exhibition, an intellectual moment in urgent need of rediscovery and re-evaluation.