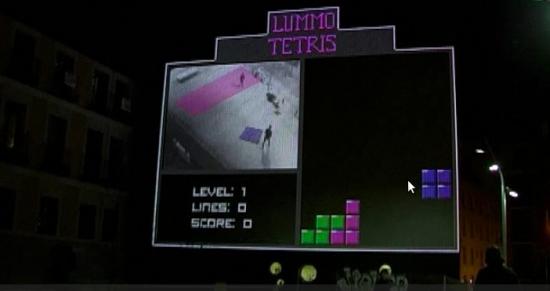

We are building CultureStake, the world’s first collective cultural decision making app (using Quadratic Voting on the blockchain) because we want to enable all communities to choose the creative experiences they want to have in their own areas. The original idea was driven by an awareness that top down arts programming is increasingly problematic. We wanted to find a way to give more people more of a say in what art and culture gets produced in their neighbourhoods – and more opportunity to be the co-creators. In a nutshell, our mission is to put the public at the heart of public arts.

Communities

We want communities to explore and learn together what we all want to experience in our localities. For example how might a theatre audience cast a play differently or a park community curate a public art exhibition?

Cultural Organisations

We want deeper, richer and more open consultation with the communities cultural organisations work for. For example, how might a city council find out which new artwork should occupy a recently vacated public plinth. Or how might an arts organisation discover which artist on their shortlist should be next summer’s blockbuster?

For Everyone

We want a data commons that widens the conversation about how art is valued by different communities around the world. For example, how might our ideas about culture change if we can see what’s important to other people?

We are using Quadratic Voting because it takes us all from confusing numbers to nuanced feelings.

In QV voters receive a number of ‘vibe credits’ which they can allocate to different creative proposals to express their support. The quadratic function means that showing a strong preference comes at a credit cost. Or rather:

This means that QV is quite unlike any other voting process. Indeed, unlike a one person one vote system, in QV votes express not just what we care about but how much we care! This matters because one person one vote systems usually don’t present the reason why someone voted the way they did or how strongly they felt about it. Politics have taught us not to trust the way votes are interpreted. Voters’ intentions are often misrepresented and communities are polarised about the limited information. Whereas QV allows us to express the intensity of our convictions, giving each of us:

Plus we’ve designed CultureStake so vote organisers can weight the votes of those closest to the issues that matter. For example, in our use of CultureStake for the People’s Park Plinth, any votes cast inside Finsbury Park mean more overall. So those most affected get more of a say.

And we run all CultureStake votes on the blockchain because the blockchain is like a big indelible ledger. This means that a vote cannot be rigged and is always stored extra safely so what we can promise voters is that they can trust our system.

There are many ways to run a CultureStake vote. A theatre could develop an unfinished performance and ask communities to choose the next steps. An arts organisation might offer up a range of different events and invite communities to choose what they want to encounter. Either way, the voting system doesn’t rely on asking everyone to just pick their favourite, but rather explore their thoughts and feelings in relation to a set of questions. So the result is always knowing more about what communities think and feel. Plus, we never show what ranked 1st, 2nd, or 3rd, but rather what was selected and what thoughts and opinions drove people’s selections.

At Furtherfield we are using CultureStake to power our People’s Park Plinth initiative in Finsbury Park. The concept behind the People’s Park Plinth is that our Finsbury Park buildings and even the park itself will act as a plinth for public digital artworks chosen by our communities using our CultureStake app.

The Gallery building will therefore provide an interface where people can scan hoardings to access works which offer a range of XR-enabled experiences in the park. Annually there will be a set of ‘proposal’ artworks, which will give people a first glimpse at what can be created more fully later in the year. Everyone will have time to explore these proposals and then use CutlureStake to choose what they want.

In our pilot year we tripled local engagement and received amazing local feedback like this:

“I live nearby and I’ve been talking about this with my friends for months, it’s such a great idea, to give people a say!”

“[…]decentralisation allows people to have slower but more grassroots-based management of any decision making.”

“I think it’s good that we have a say as well. And I really love voting.”

“Usually I guess I choose art by going to a place and supporting it like that but I’ve never been involved so much in really deciding on what I will see next. And yeah it makes me actually feel good too.”

“[…] quite a lot of times actually […] art is reserved only for the higher echelons of society and I feel like this is really nice that anyone can come in and you vote for who you like or what art you like.”

“I do feel represented…”

We are now in the next phase of development and are actively looking for partners from different types of venues and communities to partner with us so we can explore their unique needs and ensure we have a robust system.

If you are a small, medium, large, networked, physical, touring, online or any other type of cultural entity that wants to deepen your community connections we would love to hear from you. We want to know how you would use CultureStake in your own context and what you would like to achieve. To find out more contact Charlotte and she’ll arrange a meet up.

Furtherfield has worked with decentralised arts and technology practices since 1996 inspired by free and open source cultures, and before the great centralisation of the web.

Visit DECAL website

10 years ago, blockchain technologies blew apart the idea of money and value as resources to be determined from the centre. This came with a promise, yet to be realised, to empower self-organised collectives of people through more distributed forms of governance and infrastructure. Now the distributed web movement is focusing on peer-to-peer connectivity and coordination with the aim of freeing us from the great commercial behemoths of the web.

There is an awkward relationship between the felt value of the arts to the majority and the financial value of arts to a minority. The arts garner great wealth, while it is harder than ever to sustain arts practice in even the world’s richest cities.

In 2015 we launched the Art Data Money programme of labs, exhibitions and debates to explore how blockchain technologies and new uses of data might enable a new commons for the arts in the age of networks. This was followed by a range of critical art and blockchain research programming:

Building on this and our award winning DAOWO lab and summit series, we have developed DECAL – our Decentralised Arts Lab and research hub.

Working with leading visionary artists and thinkers, DECAL opens up new channels between artworld stakeholders, blockchain and web3.0 businesses. Through the lab we will mobilise research and development by leading artists, using blockchain and web 3.0 technologies to experiment in transnational cooperative infrastructures, decentralised artforms and practices, and improved systems literacy for arts and technology spaces. Our goal is to develop fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

For more see our Art and Blockchain resource page.

This event is part of exhibtion, Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens: The Art of Eduardo Kac, at Furtherfield Gallery.

Inspired by and building on the exhibition, these workshops will draw together themes and issues which have emerged from the Arts and Humanities Research Council thematic research programmes. Workshops are led by Andrew Prescott, curator of the exhibition and Professor of Digital Humanities at the University of Glasgow.

Digital Transformations and Community Engagement

18 April 2018, 10:30 – 16:00

How can we promote collaboration between communities and academic researchers? Do digital methods help create community engagement?

FREE | booking essential

Reconnecting Artistic Practice and Humanities Research

25 April 2018, 10:30 – 16:00

Can a renewed dialogue between humanities scholars and artistic practice provide innovative perspectives to confront current social and cultural challenges?

FREE | booking essential

Language and Diversity

8 May 2018, 10:30 – 16:00

Exploring the role of language and translation in promoting understanding and communication within, between, and across diverse cultures.

FREE | booking essential

Science in Culture

23 May 2018, 10:30 – 16:00

How can art engage with science and technology? And how can art explore the role of science in culture?

FREE | booking essential

More information about Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens: The Art of Eduardo Kac

We are based in the heart of Finsbury Park, which is used by roughly 55,000 people weekly in a neighbourhood described as ‘superdiverse’ for the nearly 200 languages spoken locally. Working with park users and stakeholders, artists, techies, researchers, policy-makers, and other local arts organisations we have developed a new approach to cultural co-creation in this much loved shared public space: ‘Platforming Finsbury Park’.

Our aims are to:

An important part of this work is our 2019-21 programme, Citizen Sci-Fi, designed to engage our local community in creative imaginings of the future of Finsbury Park. We are producing a range of participatory networked art practices that respond to today’s important questions, in this unique urban park context, that empower local participants, and draw on international areas of practice.

By transforming Finsbury Park into a canvas for participatory digital arts we want to explore how insights drawn from the locality, and meaningful co-created cultural experiences can improve wellbeing for people, establishing new arts practices for Finsbury Park and other public spaces and localities.

Read more about this project in our Spring 2018 Editorial

This 3-year programme combines citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

#CitSciFi – crowdsourcing creative and technological visions of our communities and public spaces, together.

The Time Portals exhibition, held at Furtherfield Gallery (and across our online spaces), celebrates the 150th anniversary of the creation of Finsbury Park. As one of London’s first ‘People’s Parks’, designed to give everyone and anyone a space for free movement and thought, we regard it as the perfect location from which to create a mass investigation of radical pasts and futures, circling back to the start as we move forwards.

Each artwork in the exhibition therefore invites audience participation – either in its creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more imaginings of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

For this Olympic year we will consider the health and wellbeing of humans, other life-forms and machines.

For this year of predicted peak heat rises we will consider how machines can work with nature.

DOWNLOAD

Full exhibition programme

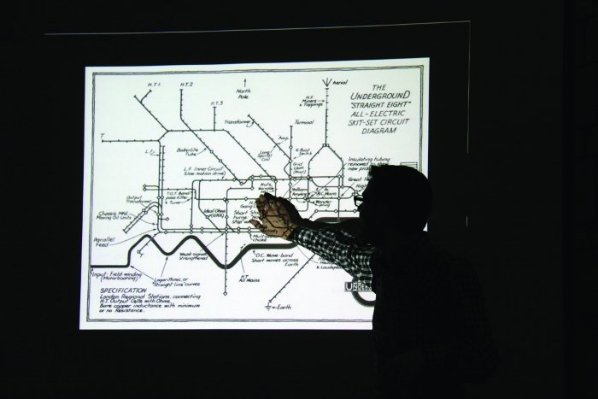

‘Interface Perception. The Cybernetic Mentality and Its Critics: Ubermorgen.com’ by Søren Bro Pold

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

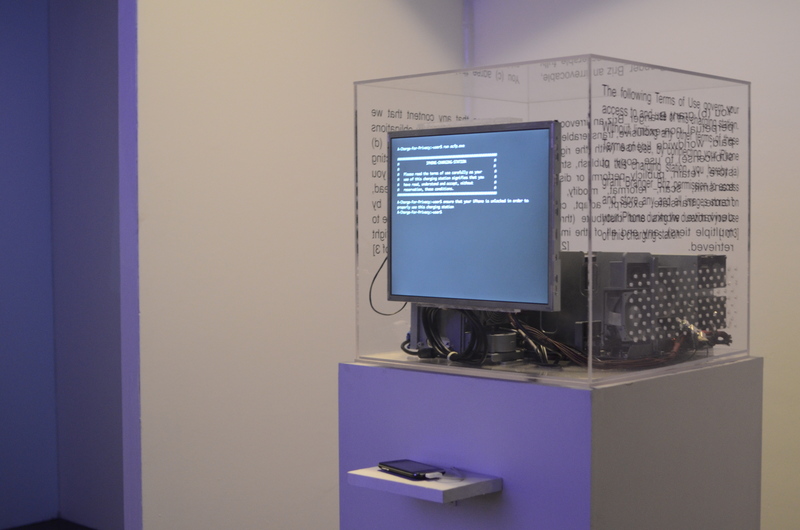

Beyond the Interface is an exhibition and series of events presented by Furtherfield, where leading international contemporary artists explore the technical devices that pervade our lives.

“The interface is the sense organ of the computer, whereby it becomes part of human culture” – Søren Bro Pold1

How much of our life do we spend in front of screens? Typically young adults in the UK spend more than a third of their waking lives watching TV or using computers, smartphones and tablets.2 These glowing rectangles are just one interface through which we contribute to the growing global human-machine network.

Nowadays a multitude of sensors proliferate in these same devices along with the chips and transmitters that are embedded in all consumer goods. Our actions are tracked, our utterances and exchanges are monitored, and our behaviours inform the design of future media, systems and products. This is the cybernetic loop.

The interface is the boundary across which information is exchanged, causing a transformation in one or both sides of that boundary. Between individuals, corporations and states; beliefs and disciplines; components of computer systems; or machines and living beings. Interfaces have always been a site of control, hidden in plain view: symbolic, social or technological. Seduced and habituated, we forget to question how we are dominated and reprogrammed by the very facilities that are supposed to free us as part of the digital revolution. Lori Emerson suggests this is an “overwhelming push to disempower users/consumers with closed devices”.3

As you approach Furtherfield Gallery in the middle of London’s Finsbury Park, you will notice that the external walls have been transformed into an immersive installation of lush, rippling images of water lilies, leaves and other organic forms. Giverny Remediated is an installation of performative prints by Nathaniel Stern (US) continuing his ‘Compressionism’ series of work. Part of Stern’s Compressionist series, this work references Monet’s immersive painting installation Water Lilies, painted a century ago, only in this case the artist has strapped a hacked scanner to his body in order to create the works.

“Compressionism follows the trajectory of Impressionist painting, through Surrealism to Postmodernism, but rather than citing crises of representation, reality or simulation, my focus is on performing all three in relation to each other.”4

In a new commission Stern will create ‘Rippling Images of Finsbury Park’, a new public artwork created in the boating lake (which sits adjacent to Furtherfield Gallery). The artworks will be available to download by public USB installed in the Gallery walls as part of Dead Drop, the offline, anonymous, file sharing, peer to peer, network.5

Visitors can also download the essay that sets out many of the concepts behind this exhibition. ‘Interface Perception – The Cybernetic Mentality and Its Critics: ubermorgen.com’ by Søren Bro Pold (editor of Interface Criticism, Aesthetics Beyond Buttons) explores how we perceive interfaces and the role that art has to play in making technology more feelable.

Beyond The Interface – London is a remix of an exhibition co-curated by Furtherfield with Julian Stadon for ISMAR 2014, the International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality, that took place in Munich in September 2014.

Happening alongside this exhibition

Scan the park

Dates June-July to be confirmed, Furtherfield Gallery

Workshops for all ages to hack your own scanner. Create your own rippling images of Finsbury Park based on the Nathaniel Stern commission. Also chance to show your work in Furtherfield Gallery. Please contact info@furtherfield.org to join the waiting list.

Telluro-geo-psycho-modulator workshop and field trip with Jonathan Kemp

2-3 May, Furtherfield Commons

How are our brain states modulated by the interference patterns created by our immersion in natural weak geomagnetic fields?

Living Assemblies – Design Your Silken Self

6 – 7 June, Furtherfield Commons

In partnership with The Arts Catalyst. A hands-on workshop with Veronica Ranner, investigating the coupling of the biological material silk, with digital technologies

WWW TV installation, Web We Want Festival

28-31 May, Southbank Centre, London

Featuring Grey Matter by Jennifer Chan and Facial Weaponization Communiqué: Fag Face by Zach Blas against a bank of monitors displaying videos found on the Web of contextual media, systems and products.

Back to the Future

Sunday 31 May 17:00 – 18:00, Queen Elizabeth Hall Front Room

To close the Web We Want festival, Jude Kelly CBE, Artistic Director of Southbank Centre is joined by Renata Avila (Web Foundation), Sarah T Gold (Alternet, WikiHouse Foundation) Ruth Catlow (Furtherfield) to recap the festival and look towards the next 25 years of the Web – what’s in store for the future and how can we make an impact on the shape of the Web?

Symposium: Designing Digital Creative Commons for the Performing Arts

27 June

Digital tools for communication, artistic collaboration, sharing and co-creation between artists, and creative audiences. Booking info to follow soon.

Museum of Contemporary Commodities

Running parallel to the exhibition is an artistic research project by Paula Crutchlow and Dr Ian Cook, exploring trade justice issues by presenting the things we buy today, as the heritage of tomorrow.

Walkshop led by data activist Dr Alison Powell

7 May 6-8.30pm, Furtherfield Commons

To find out more about the local retail environment, local commodities, trade-justice and data processes in Finsbury Park. As part of the Museum of Contemporary Commodities.

Commodity Culture social event

Saturday 13 June 11am-3pm, Furtherfield Commons

Drop-in for cake and a cup of something, and a chat about trade and exchange in Finsbury Park. Open to everyone. As part of the Museum of Contemporary Commodities.

Zach Blas is an artist, writer, and curator whose work engages technology, queerness, and politics. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art at the University at Buffalo. His work has been written about and featured in Art Review, Frieze, Art Papers, Hyperallergic, Rhizome, Mousse Magazine, The Atlantic, Al Jazeera America, The New Inquiry, Leonardo Electronic Almanac, and Wired. http://www.zachblas.info/

Branger_Briz are artists, educators && programmers bent on articulating our digital landscape creating memorable interactive projects for themselves && clients. To them contemporary culture means digital culture. They are driven by a desire to share our digital literacies, so their work tends to be public-facing && leverage new-media. They specialise in producing custom projects from concept >> design >> development >> launching/sharing && love every step in the process.

http://brangerbriz.com/

Mez Breeze is an Australian-based artist and practitioner of net.art, working primarily with code poetry, electronic literature, and digital multimedia works combining text, code, image and sound. Born Mary- Anne Breeze, she uses a number of avatar nicknames, including Mez and Netwurker. As of May 2014, Mez is the only digital writer who’s a non- USA citizen to have her comprehensive career archive (called “The Mez Breeze Papers”) housed at Duke University, through their David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

http://mezbreezedesign.com/

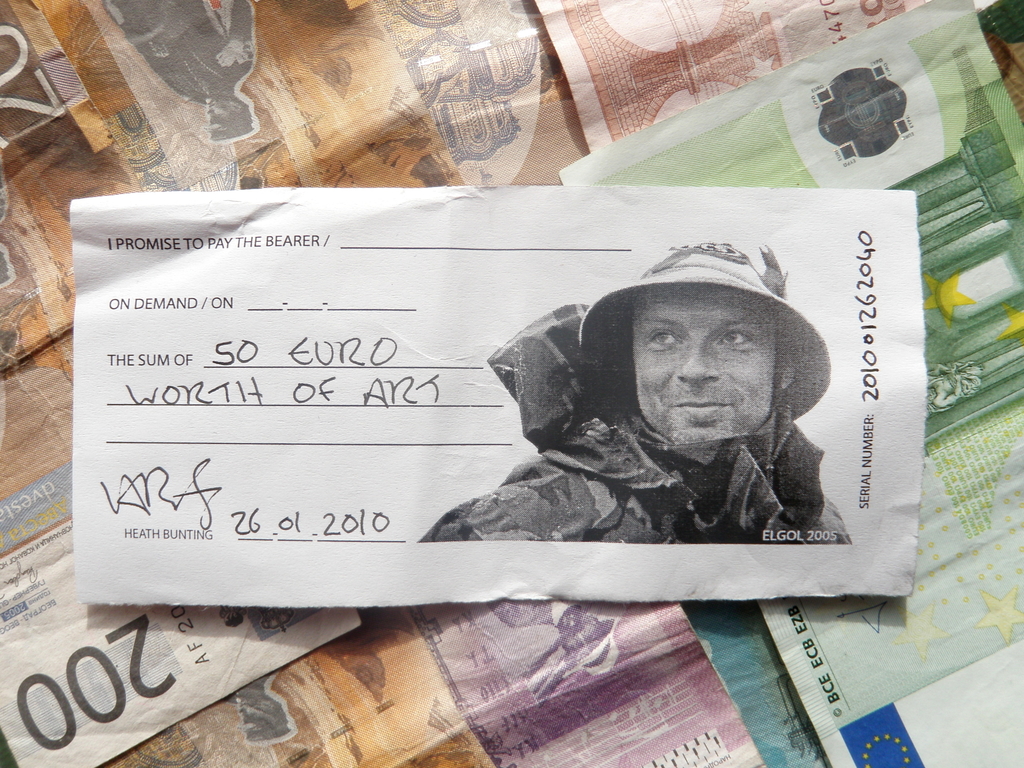

Heath Bunting was born a Buddhist in Wood Green, London, UK and is able to make himself laugh. (currently, reduced to only smile) He is a co-founder of both net.art and sport-art movements and is banned for life from entering the USA for his anti genetic work. His self taught and authentically independent work is direct and uncomplicated and has never been awarded a prize. He is both Britain’s most important practising artist and the World’s most famous computer artist.

http://www.irational.org/heath/

Jennifer Chan makes remix videos, gifs and websites that contend with gendered affects of media culture. Chan had solo presentations at the Marshall McLuhan Salon in the Embassy of Canada in Berlin for Transmediale 2013 (Germany), Future Gallery (Berlin), Images Festival (Toronto), Vox Populi (Philadelphia) and recently LTD (Los Angeles). She has a HBA in Communications, Culture, Information Technology from University of Toronto and a MFA in Art Video from Syracuse University. Chan was born in Ottawa, raised in Hong Kong, and is now based in Chicago. She co-organizes Dorkbot Chicago and helps women learn code at Girl Develop It. http://jennifer-chan.com/

Francesca da Rimini explores the poetic and political possibilities of collaborative (tel)embodied play. Early net projects include GashGirl, FleshMeat and the award-winning labyrinth dollspace. As cyberfeminist VNS Matrix member she inserted slimy interfaces into Big Daddy Mainframe’s databanks, perturbing the (gendered) techno status quo. Her doctoral thesis at the University of Technology Sydney investigated three diverse cultural activism projects seeding the formation of new collective subjects. She has co-authored Disorder and the Disinformation Society: The Social Dynamics of Information, Networks and Software (Routledge 2015). http://gashgirl.sysx.org

Genetic Moo (Nicola Schauerman and Tim Pickup) have been creating individual interactive art works for over 5 years. They create Microworlds, digital ecosystems and living installations that are always changing, mutating, and evolving in front of your eyes. Both gained Masters degrees from the Lansdown Centre for Electronic Arts. They have exhibited extensively in galleries, festivals and museums.

http://www.geneticmoo.com

Nathaniel Stern is an artist and writer, Fulbright grantee and professor, interventionist and public citizen. He has produced and collaborated on projects ranging from ecological, participatory and online interventions, interactive, immersive and mixed reality environments, to prints, sculptures, videos, performances and hybrid forms.

His book, Interactive Art and Embodiment: The Implicit Body as Performance, takes a close look at the stakes for interactive and digital art, and his ongoing work in industry has helped launch dozens of new businesses, products and ideas.

http://nathanielstern.com

Beyond the Interface – Artists Panel

Web We Want Festival – Southbank Centre

28-31 May 2015

Chair – Ruth Catlow

Speakers (TBC)

EXHIBITION LOCATION

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Visiting information

PANEL LOCATION

Southbank Centre

Belvedere Road, London SE1 8XX

Directions

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Contact Ruth Catlow, Furtherfield

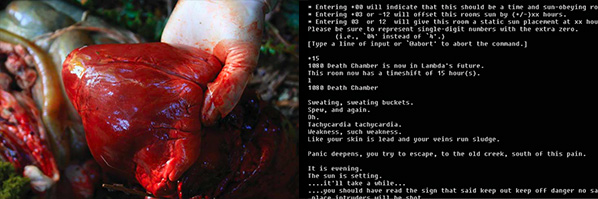

[Trigger warnings for just about everything goes here. Please Do Not Read the following if you’re sensitive, or concerned about trigger(ing)s.]

“An uproar of voices was coming from the farmhouse. They rushed back and looked through the window again. Yes, a violent quarrel was in progress. There were shoutings, bangings on the table, sharp suspicious glances, furious denials…Twelve voices were shouting in anger, and they were all alike. No question, now, what had happened to the faces of the pigs. The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

– George Orwell, Animal Farm.

Today’s online spaces are communication minefields. When interacting in multiplayer games or social media niches, networks come drenched in reactivity bile. And although we might seem to bile-dilute, instead we intellectually saw at each other through a polite veneer. Here, civil discourse is label-trotted. Discourse bile may also erupt in balls-to-the-wall screaming matches. Such bouts involve trollbaiting, d0xxing, and Internet Rage Machine power-ups. Whatever the magnitude/form, online dialogues appear to be flooded with antagonistic commentary.

Truncated attention spans rage-burst. Such anger pockets are far from static: fuelled by such shameblood, the righteous degrade. We humiliate in order to inflate. We confront-tar and belittle-feather. The [s]urge for relevancy is sycophantically baked. We mobilize to unearth, to finger-point: we present affectivity as fact. Hate groups spread across factions, divide-blurring.

The search for sodalities is constant. Nuances are fudged. Contexts are ignored. Catharsis mutates through a checklist that reduces, confines, and truncates. We are force-fed trauma anecdotes as reality fulcrums. Baggage is exposed in painful lumps. We are not consideration-encouraged: we are expectation-drilled. We must agree. Must acquiesce. Must uncritically support. Anything else denunciation-equates.

Public shaming is the norm. We bully. We armchair-critique. Bipartisan voices lynchmob-morph, all-indignation-like. Roughshodders censor and context erase. Power drugs the inflamed and injects the underdog[s] with sudden shifting surges. Reference frames are smashed, then reiterated repeatedly till they become a thing of horror, of replication thrown from “side a” to hit “side b”. Such targets are then mirror-captured and magnified. Empathy is to be derided as weakness. Barbs are flung at all who seek to ponder “isms” or reclaim them. We must not listen in order to comprehend, to understand: we must shout.

We word weaponise [“…getting all soul-rapey on SJWs”/”…gut-cutting misogynistic neckbeards“/ “You are either with us or against us”]. Gator-screams and “die-cis-scum“-roars rule the day. We obliterate and issue-compress. We communication strangle. Equality is attainable through force. Aggression trumps assertion. Sarcasm blights compassion. Rudeness rewrites decency.

SUCH TERRIBLE WHITEWASHING SEALIONS

Power-grabs blind the sensitive. To destroy/troll/shame/swamp/embarrass/belittle/d0xx is to “win”. Sense of perspectives lose while extremisms gain. Dialogue is gamed: the loudest voices squash and rip, tear and silence. Threats echo the noose. Implications drive output. The end-goal is attention, ratification, dis[e]ruption: a pendulum power swing designed to flatten and redress. We obscure and vilify. We replicate exclusion ethics. We buck-and-doe-pass.

Online purging results in strange social crevices. Encouraged to instantaneously blurb our stream-of-tweeted-consciousness, we are off the chain. We spontaneity-bark and bleat [at] everything and all. Cohesion shatters. We no longer rely on institutions to dictate, to guide, to sanction. Moral Absolutists war-trawl Moral Relativists. The Arab Spring has turned us inside out. Unsure, we turn on each other. We emoji expose and deride. We [slut]shame and attack: all within banners born from psychologies spouting the benchmark worth of individualisation. Selfies become our egocentric standard.

We once attempted to codify, to restrain. But now, all gloves are off. We scrabble and lunge. We showcase-badge based on our version of “the categorical truth”. We bang and bleed against these corners, these intersections of emotion and intellect. Of private and public. Of control and openness. There is no room for reflection, for consideration, for clarity.

We refuse anything that calms. Online spaces are for battling. Playfulness and cohesion are sacrificed. Righteous mobs insult fling: they ratify rather than reappropriate. Alternates gleefully spout these insults as proof, stamp-ammo-ing all the while. There are, however, those who stay and observe. We await the wind-down. We desire an eventual dissolve: a fundamental shift. They can’t last, these discourse patterns. We wait for rage to course-run, for rage-fatigue. We await the next mediation bump.

In the 1990s the idea of the virtual idol singer escaped from Macross Plus’s Sharon Apple and William Gibson’s Rei Toei into the cultural imagination. Blank slates for market forces and projected desires, virtual idol singers differ from Brit School drones only in that there is no meat between the pixels and the data.

Hatsune Miku is a proprietary speech synthesis program with an accompanying character whose singing the software notionally renders. Miku the software is a “Vocaloid” synthesizer using technology developed by Yamaha and the sampled voice of voice actor Saki Fujita. Released in 2007, with additional Japanese voices in 2010 and an English version in 2013, the software topped the charts in Japan on release and has led to spin off games and 3D modelling software. It’s claimed the software has been used to produce over 100,000 songs.

Hatsune Miku the character is a cosplayer’s dream, a sixteen year old (with a birthday rather than a birthdate) Anime young-girl with impossibly long aqua hair (there are male Vocaloids as well). She’s had a chart-topping album, “Exit Tunes Presents Vocalogenesis feat. Hatsune Miku” (2010), and started performing “live” on stage in 2009 with Peppers Ghost-style technology. She’s available as (or represented as) figurines, plushes, keychains, t-shirts, and all the other promotional materials produced for successful Anime characters, pop stars, or both. Her likeness can be licensed automatically for non-commercial use. This makes her fan-friendly, although not Free Culture, and means that fan depictions and derivations of her are widespread. The majority of “her” songs are by fans rather than commercial producers.

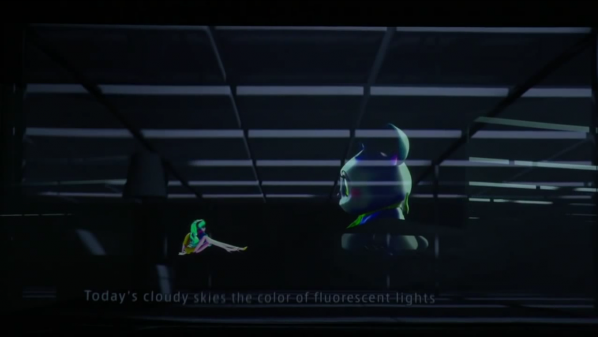

She is now appearing in “The End” (2013), a posthuman Opera (with clothes by a designer from artist-suing fashion company Louis Vuitton) where she takes the stage as a projection among screen-based scenery without a live orchestra or vocalists. Which means that someone programmed the software to produce synthesized vocals and someone else negotiated the rights to use the likeness of the characted commercially dressed in a particular designer’s virtual clothing. “She is now appearing” is easier to say, but like Rei Toei this is an anthropomorphised representation of the underlying data.

It’s getting rave reviews, and the music is competent, enjoyable and affecting: strings, electronica and Supercollider-sounding glitches and line noise under breathily cute synthesized vocals. The visuals are CGI with liberally applied glitch aesthetics, mostly featuring Hatsune Miku and a cute chinchilla-ish animal sitting in or falling through space. The plot is a meditation on what mortality and therefore being human can possibly mean to a virtual character. To quote the soundtrack CD booklet notes:

Miku, who has had a presentiment of her fate, talks with animal characters and degraded copies of herself to ask the age-old questions ‘what are endings?’ and ‘what is death?’.

The phantom in this particular opera is composer Keiichiro Shibuya, who appears onstage largely hidden by two smaller projection screens. As the man behind the curtain it’s tempting to read him as the male agent responsible for the opera’s female subject’s troubles. His presence onstage also threatens to make him the human subject of what is intended to be a repudiation of opera’s European anthropocentrism. But without such an anchor the performance would seem less live and perhaps become cinema rather than opera. It seems that a posthuman opera needs a human to be post.

Music production is uniquely suited to the creation of virtual characters through tools, brands and fandoms. Hatsune Miku functions as a guest vocalist, a role combining artistic talent and social presence with a well understood standing in the economics of pop. In art, Harold Cohen‘s sophistiated art-generating program AARON was licensed as a screensaver anyone could run to create art on their Windows desktop computers, but despite its human name and human-like performance, AARON is never anthopomorphised or given an image or personality by Cohen. Could a virtual artist combining software and character similar to Hatsune Miku function in the artworld or in the folk and low art of the net and the street?

The license for Hatsune Miku the character is frustratingly close to a Free Culture license. Could a free-as-in-freedom Hatsune Miku or similar character succeed? Fandom exists as an ironisation of commercial culture, appropriating mass culture in a bottom-up repurposing and personalisation of top-down forms. Without the mass culture presence of the original work, fandom has no object. Perhaps then without the alienation that fandom addresses, shared artistic forms would not resemble fandom per se.

There are precedents for this. Collaborative personalities abound in art, such as Luther or Karen Blisset. And in politics there is Anonymous. There are also existing Free Culture character like Jenny Everywhere, or even the more informally shared Jerry Cornelius. So it is possible to imagine a Free Software Hatsune Miku, but it’s less easy to imagine what need this would meet.

Unlike the idol signers of literature and television, there’s no pretence that Hatsune Miku is an artificial intelligence. But she is an artifical cultural presence, created by her audience’s use of her technical and aesthetic affordances. Like the robots in Charles Stross’s “Saturn’s Children” (2008), Miku’s notional personhood (such as it is) is defined legally. As a trademark and various rights in the software rather than as a corporation in Saturn’s Children, but legally nonetheless. Heath Bunting’s “Identity Bureau” shows how natural and legal personhood interact and can be manufactured. It’s tempting to try to apply Bunting’s techniques to software characters. If Hatsune Miku had legal personhood, would we still need a human composer onstage?

“The End” was written by that human composer, but software exists that can generate music and lyrics and to evaluate their chances of being a top 40 hit. Combining these systems with software made legal persons would close the loop and create a posthuman cultural ecosystem that would be statistically better than the human one, which I touched on here. It’s not just our jobs that the robots would have taken then. Given the place of music in the human experience they would have taken our souls.

Or the soullessness of Fordist (or Vectorialist) pop. Such a posthuman music system would exclude the human yearning and alienation that fan producer communities answer. It would be an answer without a question. Hatsune Miku is in the last analysis a totem, the products incorporating her are fetishes of the hopeful potential that pop sells back to us.

Despite “The End”, Hatsuke Miku has no expiry date and cannot jump a shuttle offworld. It’s not like she’s going to marry a fellow pop star or come tumbling out of networked 3D printers. But human beings are becoming less and less suitable subjects for the demands of cultural and economic life. In facing our mortality for us Hatsune Miku may have become more human than human.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

“None but those who have experienced them can conceive of the enticements of science.” Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

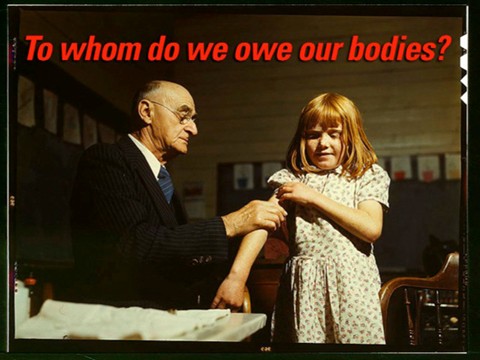

Rachel Falconer writes about the cyberfeminist art collective subRosa, a group using science, technology, and social activism to explore and critique the political traction of information and bio technologies on women’s bodies, lives and work.

Following a recent interview with the founding members of the collective, Hyla Willis and Faith Wilding, this article presents subRosa’s trans-disciplinary, performative practice and questions what it means to claim a feminist position in the mutating economies of biotechnology and techno-science.

The technological redesigning and reconfiguration of bodies and environments, enacted through the economies of the biotech industry, is an emerging feature of contemporary life. As these new ‘bits of life’ enter the biotech network, there is a slippage in our mental model of what constitutes the body, and more specifically, ‘life’ itself. As radically new biological entities are generated through the processes of molecular genetic engineering, stem cell cultivation, cloning, and transgenics, bio-artists and bio-hackers co-opt the laboratory as a site of critical cultural practice and knowledge exchange. Human embryos, trans-species and plants are constructed, commodified, and distributed across the biotech industry, forming the raw materials for bio-art, DIY biologists and open science culture.[1] These corporeal products and practices exist within new and alien categories, transgressing the physical and cognitive boundaries set by biopunk science fiction and edging towards the possibility of a destiny driven by genetics and life sciences. With the eternal rhetoric of a high-tech humanity, and the threat of Michel Foucault’s[2] biopolitics constantly on the horizon, today Harraway’s[3] myth of the cyborg exists in the form of corporeal commodities travelling through the global biotech industry. Scientific research centres stock, farm, and redistribute biological resources, (often harvested from the female scientists themselves). Cells, seeds, sperm, eggs, organs and tissues float on the biotech market like pork belly and gold. Seeds are patented, and other agro-industrial elements are remediated and distributed as bits of operational data across the biotech network. We/cyborgs[4], are manifested as a set of technologies and scientific protocols, and, as a result, the female body in particular, is reconfigured into a global mash-up of cultural, political and ethical codes.

The increasingly pragmatic realisation of the biotech revolution has provoked a ‘cultural turn’ in science and technology studies in general, and feminist science studies in particular. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s dOCUMENTA (13) proposed an interdisciplinary approach to the role of science for ‘culture at large’. Certainly, by foregrounding the heavy hitters in the field such as Donna Haraway and Vandana Shiva, dOCUMENTA (13) laid claim to addressing the global conflicts of biotechnology. However, the feminist agenda was not specifically addressed, and the key issues of the impact of biotechnologies on feminist subjectivities were only paid minimal lip service. With the exception of Shiva[5], the tone of dOCUMENTA (13) hinted at a positivist, emancipatory take on biotechnology and technoscience without assuming a critical position. There was very little public debate or critical analysis engaging the philosophical, ethical, and political issues of feminism and female subjectivities within the realm of biotechnology.

Notably absent from last year’s dOCUMENTA (13), the activist feminist collective subRosa’s performative, interdisciplinary projects are channelled towards embodying feminist content, practices, and agency, and laying bare the impact of new technologies on women’s sexuality and subjectivities – with a particular emphasis on the conditions of production and reproduction. Through their research-led practice and pedagogical mission, the collective analyse the implications and conditions of the constantly surveyed female body, whilst mapping new possibilities for feminist praxis. subRosa interrogate the conditions of surveillance, private property rights, and other control mechanisms the female body is subjected to by ART(Assisted Reproductive Technologies). The collective’s hybrid, interdisciplinary practice navigates the multiple identities the female body has taken on through techno-scientific development, including: the distributed body, the socially networked body, the cyborg body, the medical body, the citizen body, the soldier body and the gestating body. In contrast to the overarching and pervasive illustration of the technoscientific cultural landscape painted by dOCUMENTA(13), the current members and founders of the collective, Hyla Willis and Faith Wilding, are very clear in their critical intent. The collective choreograph and place themselves within globalized bio-scenarios in order to question the potential for resistance and activism within these constructs.

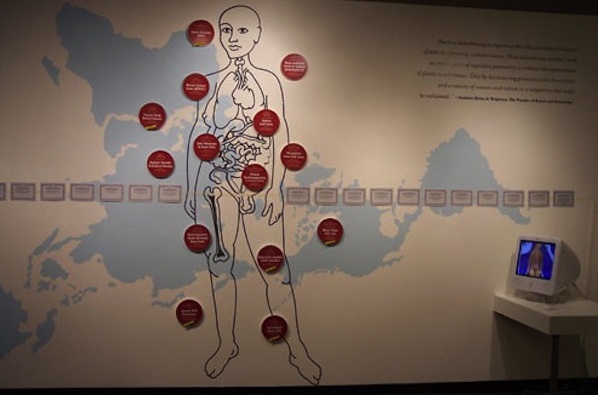

subRosa’s overarching vision to create discursive frameworks where feminist interdisciplinary conversations and experiments can take place, is research-led and takes its cue from the canon of radical feminist art practices. Cell Track: Mapping the Appropriation of Life Materials has featured in a number of exhibitions, most recently in Soft Power. Art and Technologies in the Biopolitical Age, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. This project consists of an installation and website examining the privatization and patenting of human, animal and plant genomes in the context of the history of eugenics. Cell Track highlights the disparity between the bodies that produce stem cells and the corporations that control the products generated from them. Bringing together scientists, cultural practitioners and wider publics in the construct of the gallery space, subRosa generate discourse around the patenting and licensing of DNA sequences, engineered genes, stem cell lines and transgenic organisms. The project’s participatory aim is to set up an activist, feminist embryonic stem cell research lab in order to produce non-patented stem cell lines for distribution to citizen scientists, artists and independent biotechnologists. This environment of shared knowledge production and speculative, alternative, research activity is at the heart of subRosa’s social practice.

Due to the pedagogical nature of subRosa’s activities, the collective’s critical stance towards IVF and ART has proven to be particularly provocative, and their scepticism towards the emancipatory language of ‘choice’ co-opted by ART, has been met with some resistance by other feminist practitioners. However, it is in this very agonism[6] that subRosa wish to become more visible, and they welcome criticism and debate in the public discursive spaces that they create. In a recent interview, Faith Wilding and Hyla Willis both expressed their desire to generate an expanded, and deeper discussion about the wider issues involved in ART in particular and biotechnology’s effect on female identity in general. subRosa’s potential to reach wider publics and audiences is partially determined by the socio-political context of the communities in which they operate. Perhaps in reaction to this, subRosa’s focus is now shifting towards embracing the aforementioned ‘cultural turn’ in science as they address the position of feminist scientists themselves.

The imperative to reclaim feminist discourses and narratives in science is of growing concern to subRosa, as they believe that feminist agency lies in the practice of science itself. By relocating lab-work from the dominant scientific institutions to the public environment of the gallery, subRosa provide the critical space in which new feminist scientific praxis can operate,[7] and new dialogues and discourses can be created. Their conviction that political and critical traction lies in practice as discourse, and the potential of face to face encounters, is demonstrated in their recent project for the Pittsburgh Bienal: Feminist Matter(s): Propositions and Undoings (2011). In this installation, SubRosa take Virginia Woolf’s[8] assertion that ‘tea-table thinking’ provides an effective antidote to the male-driven ‘war-mentality brewed in boardrooms and command centers’ as their main conceit. Redeploying Woolf’s idea toward the rethinking of the traditionally male-dominated discipline of science, Wilding and Willis’ installation brings traces of the science laboratory to the intimacy and hospitality of the kitchen table, and in turn, also situates what is normally a private, feminized space in a more public domain.

These tables stage a dialogue between one or two visitors in response to the presentation of female figures in science, both the popularly acknowledged and the underexposed. subRosa foreground women scientists past and present and reimagine an alternative, feminized history of science and technology. The installation explores feminism and participatory practices as modes of scientific research, with the aim of generating dialogue and discourse around the questioning of the dominant historical narrative of science. Specially tailored installations reside on each table, evoking lab work while celebrating the history of the women protagonists they play host to – from anarchist painter Remedios Varo to geneticist Barbara McClintock.

subRosa’s pedagogical imperative is at once inclusive and provocative, and their role as facilitators of a discursive space outside the traditional institutions and control structures of science, is where their radical aspirations lie. Pedagogical art practices often teeter on the brink of propaganda, and subRosa are quite comfortable with the propagandistic label. Considering the economic and cultural climate in the USA with regard to the politics of reproduction, their work has been particularly well received in the context of European cultural institutions, whereas in the USA there is greater interest for the work in academic institutional settings. Perhaps this could be symptomatic of the general privileging of discourses around intersex, transgender and queer subjectivities. The dominant bias of the gatekeepers of the artworld to showcase queer practices is evident in the promotion of artists such as Ryan Trecartin and Carlos Motta on the international circuit. Curators have tended to position artists addressing the gendered ‘Other’ within a contemporary queer framework, whilst keeping feminist art practices on the peripheries of 1960s/1970s retrospective nostalgia. This tendency presents a muddying of the waters for contemporary feminist art practices such as subRosa.

This may also be part of a more general tendency to demonize and move away from feminist identities and discourses in wider society. The academic shape shifting from ‘women’s studies’ to ‘gender studies’ to ‘queer studies’ has diminished the feminist conversation and, therefore, the impact and receivership of feminist art practices. This has rendered the popular conception of ‘Queer’ as acceptable and non-aggressive. Furthermore, the term ‘Queer’ and the subsequent morphing into the verb ‘queering’, has been co-opted by transdisciplinary academic discourse, and is now an expansive, all embracing cultural term – a phenomenon that has met with a certain amount of scepticism from the queer community.

This privileging of the expansive ‘othering’ of queer rhetoric has often resulted in feminism being rejected as a radical and out-dated political identity by art practitioners themselves. This ambivalent attitude is perhaps also indicative of the wider feminist debate, in which post-feminism has splintered into fragmented, diluted groups, each policing their own identity politics with little sense of a bigger struggle. However, the collaborative, interdisciplinary environments orchestrated by subRosa signal a return to the indisputably material actuality of the female body. Through their insistence on the possibilities of feminist bench-side practices, and the forensic unpicking of the power/control structures inherent in biotechnology, subRosa expands the feminist lexicon through the empirically re-appropriated organic materiality of the body.

Lies, Lawlessness and Disbelief: An Attempt at Thinking Art and Capital is an essay by Canadian artist & critical thinker, Katie McCain. McCain discusses how capitalism has become on the one hand all-encompassing and on the other utterly unreal. Arguing that we need to focus on moments of paradox, illogic and the impossible in order to rethink capital, this essay explores and succumbs to the circuity of it’s own thinking. Drawing on a host of sources, it attempts to weave an account in which system failure is seen as a point of rupture, whether in legislation, bureaucracy or thought itself.

Moments of paradox are seen as a space in which to re-orient our capacity for thought, and in doing so find a place for art as a point of resistance. It promotes a negative approach to capital, a re-imagining of nihilism, and fosters a general penchant for the illegal and the illogical. Ultimately it seeks the expansive space contained within what is impossible or unknown, although this is known to be impossible.

Download PDF of Lies, Lawlessness and Disbelief: An Attempt at Thinking Art and Capital

DIWO (Do-It-With-Others): Origin, Art & Social Context, is an update on Furtherfield’s artistic and cultural practice of DIWO. In light of the emergence of DIWO in other fields of creative practices, and its ever growing popularity. We reconnect to the original reasons of why Furtherfield introduced and shared the concept of DIWO to the world in the first place.

We revisit early historical influences from 60s and 70s Mail Art, Fluxus, Situationism, Activism and D.I.Y culture; early adventures/projects with pirate radio, a mass networked email art, and (snail mail) mail art’, street art project by Furtherfield back in 1999; to what DIWO is now today, part of a more extensive, and networked grass roots movement around the world.

It also draws upon links to P2P (peer to peer) culture, the free and open source movement. Each of these cultural activities are seen as equal, peer relations, and re-hacks an intuitive space away from traditional hegemonies and their established hierarchies.

It re-emphasize it’s core motives, as a critique against mainstream media and the traditional art establishment’s control over our art history and contemporary art imaginations. It challenges the non-critical nature of artists’ complicit desire in conforming to celebrity status and fitting into stereotypical behaviours informed by hegemony, and cultural dominance. Furthefield’s intention for DIWO has always been a about individual and collective emancipation, and this story is about what this means now…

Before we jump into Furtherfield’s first DIWO project it’s worth mentioning an earlier historical reference to Bristol city (UK) and pirate radio. I, and a dedicated group of individuals were interested in finding alternative avenues for community and collective expression. We set up various pirate radio stations in Bristol, the longest running was ‘Electro Magnetic Installation (EMI)’ pirate radio station, which ran for over 18 months, broadcasting to greater Bristol every weekend ending in 1991. We changed our location for each broadcast and disseminated disinformation to confuse the authorities. We used a home built 20 Watt stereo FM transmitter and antenna. All submitted material was provided on audio tape for broadcast, the quality or quantity was not edited and everyone interested had their sound art, cut up mixes, music and words heard by many. We had to close down after a while due to surveillance stress. We did re-emerge with other pirate radio broadcasts briefly, under various different names. An even earlier one, which we took over for a while was called ‘savage but tender’ in 1989.

Bristol in the late 80s and early 90s was a dynamic and exciting place to be. Especially if one was creative and also interested in alternative ways of thinking and living. Independent culture was thriving. It was back in the 70s when Bristol’s radical spirit of creative and political autonomy was first forged. Post punk bands such as the Pop Group, Rip Rig & Panic, spread their own influential ethos of being creative and activist as a way of life. Advocating everyday people could be different, be independent thinkers and question the validity of the established norm. This flexible blueprint of being socially conscious in an imaginative way influenced a huge mixture of genres for years to come. Breaking down the borders between the audience and the musicians playing was a legacy handed on down from punk. This includes building your own record label, setting up your own pirate radio station, self publishing and other ventures.

Furtherfield’s first collective (yet unofficial) DIWO experience was at the Watermans Art Centre, London in 1999. We were asked to present a project which reflected the free and liberated spirit of our networked on-line community and its creative culture. The name of the project was called “Pasteups@Watermans Art Centre”, not DIWO. It had all the features of DIWO, such as using email as art, and the traditional postal services (snail mail) as part of its distribtion process. From all over the world people were invited to send images and texts which were then enlarged into a mass of photocopied posters.

On Sunday 10th October 1999 all the hoardings and wall spaces in the streets around the Watermans Art Centre were blitzed with Pasteups. There was no selection of what should be taken out or left in, everything was shown. They were put up by the Furtherfield crew and who ever wished to help out. Some of those whom took part were also local to the area. The people working in the centre reacted as if they were being over taken from a dark external force, and the passing public were expressing a mixture of emotions – enjoyment, surprise, interest, confusion, distaste and annoyance. It challenged the ideal of art having to be a rigid divide and rule of amateur vs professional, using the Internet and the physicalness of the Watermans Art Centre’s building, inside and outside. The streets were used as a shared canvas to fill our collective, imaginative expressions at that time.

“”… the role of the artist today has to be to push back at existing infrastructures, claim agency and share the tools with others to reclaim, shape and hack these contexts in which culture is created.” [1] (Catlow 2010)

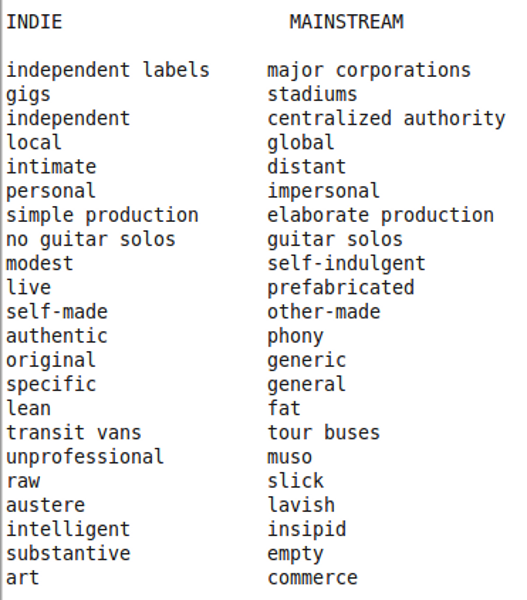

In her study ‘Empire of Dirt: The Aesthetics and Rituals of British Indie Music (Music Culture)’, Dr. Wendy Fonarow [2] investigated the UK’s indie music scene and its culture from the early 1990s to present. Below Fonarow presents the differences between mainstream and independent music culture. Contrasts are mapped out in Lévi-Straussian fashion:

“Indie itself in relation to the mainstream as an opositional force combating the dominant hegemony of modern urban life. Any band that is seen as “chipping away at the facade of of corporate pop homogeny” (Melody Maker, April 1995) is a positive addition to the indie fellowship.”[3] (Fonarow 2006)

There are similar terms above as there is with critical practices in Media Art culture, Free and Open Source culture, activism and hacktivism, and with concepts behind DIWO. Words such as self-made, independent, raw and substantive offer strong relational ties to what we feel ourselves is essential for a thriving, discerning and critically aware process, of an unfettered state of discovering, and how to do things without conforming to top-down protocols, individually or collaboratively.

“To be an artist is to contend with the present, and there are not many other careers that afford the freedom to radically examine life and society. To put it bluntly, if artists are studying and writing more about politics, culture, and education, it’s probably a reflection of the unprecedented dysfunctionality of the societies in which they live.” [4] (Deck 2005)

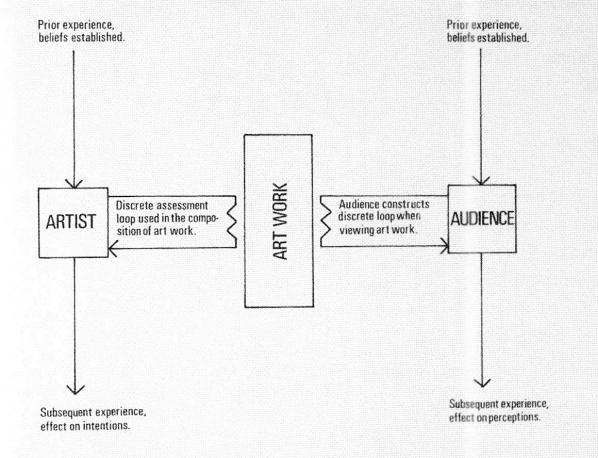

When considering an art context, critical thinking on the social nuances, social and relational variants introduce possibilities for a deeper understanding of the meaning of a work and its place in the wolrd. Not only in respect of the quality of an artwork in its own right, but it also introduces consideration concerning value. Value comes out of dialogue whilst the work is put into motion, as the process occurs as well as when it reaches its final stage of being seen – it’s birth is always messy, but this process gives us the rich nutriants, the substance.

By recognising resonances that lurk between art and culture and our own connections with these elements; as we make things with others different core values come into play. This is where knowledge of how an artwork and its meaning communicates beyond the artwork itself; to and with others, linking up to the ever changing rhythms dominating society. All this, also depends on the context of how and where a work is seen. An artwork and where it is seen declares the artists’ relationship with other structures, infrastructures and networks, whether this be physical or based on-line. This informs us about the artists’ personal concepts, attitudes and social values. These attributes become part of the work; its story and part of its essence and its reasons for existing in the first place.

Whoever controls our art – controls our connection, relationship and imaginative experience and discourse around it. The frameworks and conditions where art is accessed, seen and discussed is significantly linked to representation and ownership. Socially and culturally, this process of abiding by specific rules and protocols defines who and what is worth consideration and acceptance. For art to be accepted within these ‘traditional’ frameworks a dialogue reflecting its status around a particular type of function kicks into place, it must adhere to certain requirements. Whether it is technological or using traditional art making skills the art itself must in some way conform to specific protocols before it can be allowed into the outer regions of ‘officially’ condoned culture. This process adds merit to the creative venture itself and feeds a systemic demand based around innovation in a competitive marketplace. If an iindividual or an collective does not abide by these dominating rules then they will not be seen in these frameworks. DIWO allows one to venture with many, in playful scenarios of mutual experience and interdependence, freeing up the trappings of ‘officially’ defined protocols and frameworks, governing our behaviours. This does not mean that there are no rules, it merely means that we have a more relationally informed understanding of how to work with others. Structures and aims are decided in different terms mutually.

DIWO is playful re-interpretation and fruition of some of the principles and reasons that Furtherfield was originally founded, back in 96-97. We had experienced as artists in the 80s and well into the 90s, a UK art culture mainly dominated by the marketing strategies of Saatchi and Saatchi. The same company was responsible for the successful promotion of the Conservative Party (and conservative culture) that had led to the election win of the Thatcher government in 1979. We felt that it was time to make a stance against these neoliberalist heavies controlling the art scene and our every day culture. Our aim was to move away from the typically established, sociallly engineered aspects of art culture where false credence was given to a few individuals over many others, based on their personalities alongside their depoliticized artworks.

“Furtherfield’s roots extend back through the resurgence of the national art market in the 1980s, to the angry reactions against Thatcher and Major’s Britain, to the incandescence of France in May 1968, and back again to earlier intercontinental dialogues connecting artists, musicians, writers, and audiences co-creating “intermedial” experiences.” [5] (Da Rimini 2010)

Our move away from this was to create pro-active alternatives, with social hacks, bypassing the marketing myth of the ‘genius’ as a product via the usually distracting diversions, and top-down imposed spectacles based on privilege and hegemony. Recently an article written by John A. Walker on the artdesigncafé web site, disucussed how art culture is still haunted by the power of Charles Saatchi.

“Arguably, as an art collector Charles Saatchi has become a brand in his own right—when he buys art works they and the artists who created them are immediately branded.” [6] (Walker 2010)

BritArt’s dominance of the late 80s and 90s UK art world dis-empowered the majority of British artists, and Smothered other artistic discourse by fuelling a competitive and divisive attitude for a shrinking public platform for the representation of their own work. Stewart Home proposes that the YBA movement’s evolving presence in art culture fits within the discourse of totalitarian art.

“The cult of the personality is, of course, a central element in all totalitarian art. While both fascism and democracy are variants on the capitalist mode of economic organisation, the former adopts the political orator as its exalted embodiment of the ‘great man,’ while the latter opts for the artist. This distinction is crucial if one is to understand how the yBa is situated within the evolving discourse of totalitarian art.” [7] (Home 1996)

By questioning the myths that dominate our actions we then become more empowered and confident to collaborate with others. We can only rediscover these inner creative kernals by critiquing the infrastructures dominating our behaviours. Many artists have and do conform to mainstream art world rules. This closes down space for a wider dialogue and experience for art practice to expand its possible horizons, beyond a handed down, hermetically sealed set of distant processes. When experimenting with alternative approaches of imaginative engagement a different set of values arrive. Through this we unearth things about ourselves which were already there but were trapped before by the mechanisms and mannerisms of mainstream culture and its dominant values.

DIWO (Do It With Others) is inspired by DIY culture and cultural (or social) hacking. Extending the DIY ethos with a fluid mix of early net art, Fluxus antics, Situationism and tactical media manoeuvres (motivated by curiosity, activism and precision) towards a more collaborative approach. Peers connect, communicate and collaborate, creating controversies, structures and a shared grass roots culture, through both digital online networks and physical environments. Stringly influenced by Mail Art projects of the 60s, 70s and 80s demonstrated by Fluxus artists’ with a common disregard for the distinctions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art and a disdain for what they saw as the elitist gate-keeping of the ‘high’ art world.

The term DIWO OR D.I.W.O, “Do It With Others” was first used on Furtherfield’s collaborative project ‘Rosalind’ (http://www.furtherfield.org/get-involved/lexicon). An upstart new media art lexicon, born in 2004. DIWO was officially termed here in 2006 (http://www.furtherfield.org/lexicon/diwo)

“It is in the use of the postal system, of artists’ stamps and of the rubber stamp that Nouveaux Realisme made the first gestures toward correspondence art and toward mail art.” [8] (Friedman 1995)

Mail Art is a useful way to bypass curatorial restrictions for an imaginative exchange on your own terms. With DIWO projects we’ve used both email and snail mail. Later, we will return to the subject of email art and how it has been used for collective distribution and collaborative art acitivies; but also, how it can act as a remixing tool and an art piece in its own right on-line and in a physical, exhibiting environment.

“[…] many Fluxus works were designed specifically for use in the post and so the true birth of correspondence art can arguably be attributed to Fluxus artists.” [9] (Blah Mail Art Library)

Many consider George Maciunas was to Fluxus, what Guy Debord was to Situationism. Maciunas set up the first Fluxus Festival in Weisbaden in Germany, 1962. In 1963, he wrote the Fluxus Manifesto in 1963 as a fight against traditional and Establishment art movements. In a conversation with Yoko Ono in 1961, they discussed the term and meaning of Fluxus. Showing Ono the word from a large dictionary he pointed to ‘flushing’.

“”Like toilet flushing!”, he said laughing, thinking it was a good name for the movement. “This is the name”, he said. I just shrugged my shoulders in my mind.” [10] (Ono 2008)

“The purpose of mail art, an activity shared by many artists throughout the world, is to establish an aesthetical communication between artists and common people in every corner of the globe, to divulge their work outside the structures of the art market and outside the traditional venues and institutions: a free communication in which words and signs, texts and colours act like instruments for a direct and immediate interaction.” [11] (Parmesani 1977)

Maciunas’s intentions and ideas are strongly based on creative autonomy. DIWO in the 21st Century explores its own position of (social) grounded reasoning and creative chaos. In contrast to the usual, standardized and bureaucratic implimentations by an increasingly banal, neoliberal elite controlling our art, education, media and economies.

“[…] art has become too narcissistic and self-referential and divorced from social life. I see a new form of participatory art emerging, in which artists engage with communities and their concerns, and explore issues with their added aesthetic concerns” [12] (Bauwens 2010)

“Marshall McLuhan once suggested that ‘art was a distant early warning system that can always tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it'” [13] (Gere 2002) The infrastructural tendencies that occur when ‘the many’ practice DIWO; informs us we are in a constant process which redefines the role of the individual, and our notions of centralized power and behaviour. This process also presents us with critical questions around the value of art as scarcity. In moving away from our emotional attachment with the socially engineered dependencies based on consumer led forms of scarcity and desire, we then change the defaults. If we change the defaults we change the rules, no longer besieged by top-down defaults and open to more intuitive and relational contexts.

DIWO proposes in its fluid and sensual action of immediacy; situations where anyone can play and initiate collaborative and autonomous art. It is a radical creativity, asking questions through process and peer engagement, loosening infrastructural ties and frameworks as it occurs.

DIWO is a contemporary way of collaborating and exploiting the advantages of living in the Internet age. By drawing on past experiences with pirate radio, historical inspirations from Punk, with its productive move towards independent and grass roots music culture, as well as learning from Fluxus and the Situationists, and peer 2 peer methodologies; we transform our selves into being closer to a more inclusive commons. We transform our relationship with art and with others into a situation of shared legacy and emancipation.

“The network is designed to withstand almost any degree of destruction to individual components without loss of end-to-end communications. Since each computer could be connected to one or more other computers, Baran assumed that any link of the network could fail at any time, and the network therefore had no central control or administration (see the lower scheme).” [14] (Dalakov 2011)

Even though the web and DIWO possess different qualities they are both forms of commons. They both belong to the same digital complexity, and involve us connecting with each other. They are both open systems for human and technological engagement. DIWO rests naturally within these frameworks much like other digital art works or platforms and related behaviours, but possess key differences. If we consider the functions and structures of Facebook, Google, MySpace, itunes and now Delicious, they are all centralized meta-platforms, appropriating as much users as possible to repeatedly return to the same place.

“We see social media further accelerating the McLifestyle, while at the same time presenting itself as a channel to relieve the tension piling up in our comfort prisons.” [15] (Lovink 2012)

These meta-platfroms are closed systems. Not, necessarily closed as in meaning ‘you cannot come in’, but closed to others if you consider their motives and ‘acted out’ values, exploiting human interaction and their uploaded material, and openly ‘given’ data-information. These centralized meta-platforms close choices down through rules of ownership of personal data, as well as introducing more traditional standards of hierarchy, and limits one’s view and potential experience of the Internet.

Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron saw this curious dichotomy way back in 1995. On one hand we had the dynamic energy of sixties libertarian idealism and then on the other, a powerful hyper-capitalist drive, Barbrook and Cameron termed this contradiction as ‘The Californian Ideology’. “Across the world, the Californian Ideology has been embraced as an optimistic and emancipatory form of technological determinism. Yet, this utopian fantasy of the West Coast depends upon its blindness towards – and dependence on – the social and racial polarisation of the society from which it was born. Despite its radical rhetoric, the Californian Ideology is ultimately pessimistic about real social change.” [16] (Barbrook and Cameron 1995)

Instead of submitting to an imperious process of allowing bland interaction own our behaviours; we propose an engagement where we can be more conscious and in control by exploiting further the real potential of the networks before us.

“We are not going to demand anything. We are not going to ask for anything. We are going to take. We are going to occupy.”[17] (RTS 1997)

Just like Reclaim the Streets which was an anti-car direct action movement seizing roads to prevent cars from being able to access them. Filling up public areas with thousands of bikes and using street parties as part of the political protest. We can loosen the gaze and spectacle of these propriety, meta-platforms and their dominance of our actions with others on the Internet. DIWO, is a way of thinking and acting differently, not an absolutist ‘technologically determined’ factor, but a thing of many things, and leans more towards a kind of social activism going as far back as The Diggers:

“The Diggers [or ‘True Levellers’] were led by William Everard who had served in the New Model Army. As the name implies, the diggers aimed to use the earth to reclaim the freedom that they felt had been lost partly through the Norman Conquest; by seizing the land and owning it ‘in common’ they would challenge what they considered to be the slavery of property. They were opposed to the use of force and believed that they could create a classless society simply through seizing land and holding it in the ‘common good’.” [18] (Fox)

Three elements pull DIWO together as a functioning whole, which can mutute according to a theme, situation or project. These three contemporary forms of (potential) commons mainly include; the ecological – the social – and the networks we use. By appropriating these three ‘possible’ processes of being with others; combined, they introduce and enhance potential for an autonomous and artistic process to thrive, further than the limitations of any single or centralized point of presence. It brings about small societal change, as long as we are conscious of the social nuances needed for a genuine and critically engaged, mutual collaboration.

“Online creation communities could be seen as a sign of reinforcement of the role of civil society and make the space of the public debate more participative. In this regard, the Internet has been seen as a medium capable of fostering new public spheres since it disseminates alternative information and creates alternativ (semi) public spaces for discussion.” [19] (Morell 2009)

In accordance with Mail Art tradition, DIWO began with an open-call to the Netbehaviour email list on 1st February 2007. The exhibition was at our older venue the HTTP Gallery, opening at the beginning of March. Every post to the list until 1st April was considered an artwork – or part of a larger collective artwork for the DIWO project. Participants worked across time zones, geographical and cultural distances with digital images, audio, text, code and software; they worked to create streams of art-data, art-surveillance, instructions and proposals, and in relay to produce threads and mash-ups.

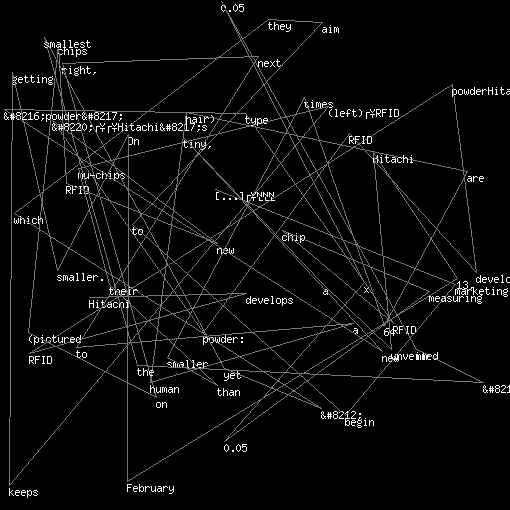

One example of a work which exploited the data-steams of continual flow while over a hundred individuals participated and collaborated in DIWO in 2007, was X-ARN.org (Gregoire Cliquet, Laurent Neyssensas and Yann le Guennec). By using the dynamic exchange of the Netbehaviour email list as reliable exchange of regualr content, the net art group were able to perform their particular and unique processes of interaction, or intervention. It had no specific title, it was literally documenting the list’s networkked behaviour, and there were many of these networked visualizations made. They experimented with the net-specific aspects of DIWO’s mass artistic activity, forming digital mappings of this collected data or data-streams in ‘real-time’, as it all happened.

![[ARN / DIWO-Betatests 2007]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/attachment3.png)

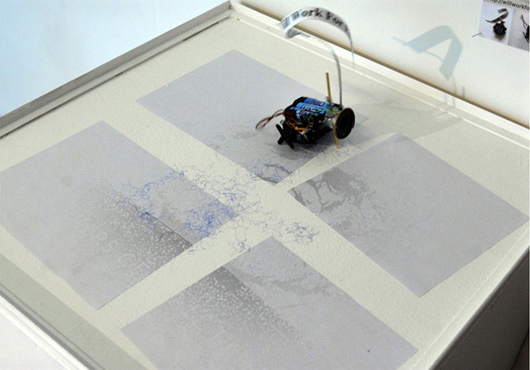

Some also participated in the experimental networked curation of the exhibition, facilitated by web cams, public IRC and VOIP technology. This co-curation event, or Curate With Others (CWO), as it was retroactively named, took place a week before the gallery opening. All subscribers to the NetBehaviour list were invited to contribute to the curation of the exhibition either by viewing the gallery floor plan and posting suggestions to the list or by taking part in the event; attending the gallery or joining the online meeting. Information about how to join the online event was posted to the list. During this event the spirit and philosophy of DIWO E-mail-Art were discussed, the deluge of diverse contributions by about a 100 people were reviewed, plinths, monitors and a drawing machine.

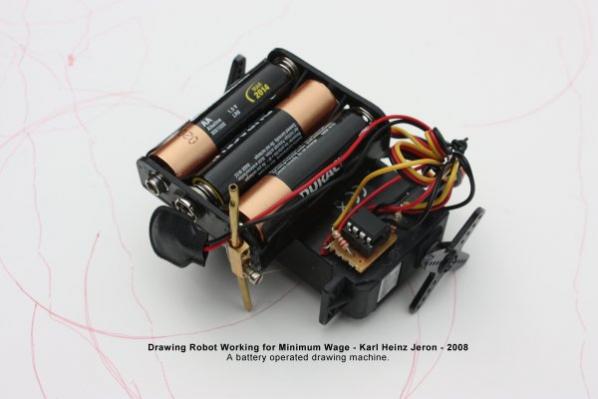

“The ‘Will Work For Food’ happening deals with the desire to find a new definition for labour and the act of working.” [20] (Jeron 2007)

Karl Heinz Jeron’s drawing machine was a vehicle equipped with a ballpen run by rechargable batteries, and when turned on created random drawings. Jeron’s machine was not switched on, unless he received gifts in the post such as chocolates or any other form of economic support. After (thankfully) receiving various contributions in the post the image supplied by Jeron of Karl Marx would gradually be scribbled over.

This section of the Article is an edited version of a collaborative text by Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett. Originally published on Vague Terrain in 2008. [21]

Present in the flesh were the Furtherfield.org crew and James Morris (regular, esteemed DIWO contributor).

Frederik Lesage manned the Public IRC and, as ‘DIWOchatbod’, who documented the conversation in the gallery for the benefit of those online co-curators who had trouble logging into Skype. Through the afternoon the online event was visited by eight people. The CWO event determined the format of the DIWO exhibition and the Furtherfield.org crew was charged with installing it. So, about approxximately 15 individuals on the day co-curated the setting up of the exhibition. Afterwards we informed everyone on the Netbeahviour list for any last minute details and suggestions and then continued with everything.

(Floorplan of Do It With Others (DIWO) at HTTP-Gallery, London. 2007)

The centerpiece of the exhibition was an e-mailbox containing all submissions; sorted and categorised for visitors to explore and redistribute by clicking ‘Forward Mail’. Streams and Themes displayed images, texts, sounds, code, and movies, primarily by single contributors (human and machine) as well as collections of themed posts or particular kinds of activity). Threads contained series of dialogic emails whose senders were remixing images, movies and code, most often in action and response). Other categories included Proposals and Instructions and Approaches to E-Mail Art.

(DIWO curated emailbox displaying image 3 tampered, posted by Chris Fraser 28/02/07)

Many of the themed folders and subfolders had their corollaries in the physical space of the gallery in the form of wiggly overlapping streams of printed images, pinned to the walls. Threads were represented by scrolls; one post after another in chronological order. A TV ran a video compilation, a sound compilation was played over four speakers, and two installation works were devised especially for the space. Karl Heinz Jeron’s ‘Will Work for Food’ and a print/projection mashup by Thomson and Craighead and Michael Szpakowski.

(Visitor to DIWO E-Mail Art at HTTP Gallery explores the DIWO email box. 2007. Image by Pau Ross)

All categories were liberally interspersed with off-topic discussion, tangents and conversational splurges so one challenge for co-curators was to reveal the currents of meaning, and emerging themes within the torrents of different kinds of data, process and behaviour. Another challenge was find a way to convey the insider’s – that is the sender’s and the recipient’s- experience of the work. These works then were made with a collective recipient in mind; subscribers to the Netbehaviour mailing list. This is a diverse group of people, artists, musicians, poets, thinkers, programmers (ranging from new-comers to old-hands) with varying familiarity with and interest in different aspects of netiquette and the rules of exchange and collaboration. This is reflected in the range of approaches, interactions and content produced. Before DIWO, extensive press releases were posted to different email lists, and online art platforms to join the Netbehaviour list to collaborate on the project.

(Lem Pollocked. By Lem Urtastik 16/2/07 / Created using Jackson Pollock artware by Miletos Manetas)

As with our previous experience of collective media arts ventures such as the first round of NODE.London Season of Media Arts (2006) [21] “we saw that lots of people invested with most enthusiasm in unstructured discourse; meandering and complex. This gave all participants a partial but meaningful view of the diverse contexts in which we worked, allowing us to make decisions about what our contribution could be. These many-to-many deep processes are never efficient but still invaluable to us in a culture where the pressures are always to be newer, faster, better-oiled, less philosophical, less human (ie less messy and complicated), more productive in the service of strategic overview.” (Garrett and Catlow) [ibid]

The next DIWO took place in 2009. It was called ‘Do It With Others (DIWO) at the Dark Mountain’. It was a collaboration between the then, newly formed ‘The Dark Mountain Project’, [22] Furtherfield and those participating in DIWO. A Dark Mountain manifesto grew out of a conversation between Paul Kingsnorth and Douglad Hine. It was an invitation to a new cultural response to the converging crises of climate change, resource scarcity and economic instability.