For 30 years, Furtherfield has pioneered the critical imagination of art, technology, and networked cultures. In this time dominant global actors have created and imposed systems that support contemporary life for some at the same time as poisoning our planetary-wide environment and societies at an escalating rate. There is an urgent need to adopt the principles of less, again and differently, in a fair and equitable way. Seeking to cause less harm. Acting again on the knowledge that has been available (if ignored or downplayed) for decades. Acting differently in response to emerging knowledge, ways of knowing, being and feeling. Understanding our work in this way, how it exists within a living system, is one way of accepting how we are all material beings situated within vast chains of consequence, enmeshed within larger ones. This requires a different standard of responsibilities, a way to be responsive and accountable in a changing world working to address the uneven impacts on people, creatures, and places that may be geographically remote from us, but which nevertheless bear the cost of our actions.

In 2025 we shift the main focus of our work from our long-standing gallery in Finsbury Park, North London to a mid-sized town on Suffolk’s East coast. With a population of 24,000, Felixstowe town is our new home, where we will join existing communities, cultural partners, ecosystems, and species. This transition is a modal shift for the organisation and means we are doing things differently. In Felixstowe, we begin a new journey of becoming an embedded and community-needs-led art organisation focused on art, technology, and eco-social change. Eco-social change is systemic transformation, integrating social justice and ecology— to create fairer, more resilient futures for all.

With this move we commit to being in relation to communities, contexts, and biodiverse regions that are entirely new to us. In creating this policy we hope not only to “move to” but to “move with” our new location, developing different relationships with ourselves, each other, and the land, at the same time composting and letting go of existing practices and connections that harm. This environmental action plan therefore refers to listening, learning, flexibility, agility, stamina, synchronisation, and interpersonal mobility that will be required.

Our first environment action is to sign up to Culture Declares Emergency. Our second has been to develop an environmental policy for the next three years. Our third will be to make two climate pledges by the end of year one.

“We declare that the Earth’s life-supporting systems are in collapse, threatening biodiversity and human societies everywhere.

Alive to the beauty of our planet, we unite to challenge the dominant global power structures that fail to protect us as they disregard scientific consensus, silence marginalised voices and perpetuate ecocide.

As Declarers, we take action to harness the power of arts and culture to express heartfelt truths and address deep-rooted injustices, to care for and create adaptive, resilient and joyful communities, and to influence the urgent and necessary transformation of harmful global systems.”

On creating this policy, we :

In this new phase, we are committed to

Curated by Sarah Cook together with the Director of Somerset House, Jonathan Reekie.

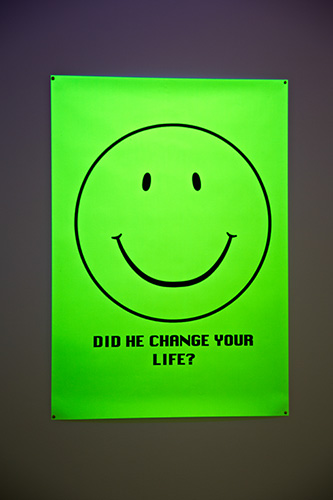

Economy has re-invented time. Development of industrialism and accompanying its advancements, for example, the invention of the railroad, forced standardisation of time. During 1700-1900 this invention increased methods of moving goods, new technologies and large scale investment in the UK’s countries infra-structure (communications network). The result was a complex transport system including roads, rail, canals and the London Underground.[1] Without socio-economic time discipline, it would have been impossible to progress into modernity. Similarly, capitalism and all its products which are well-known to us today, could not have functioned without the disruption of humans’ natural sleep cycle. The artists in the 24/7 exhibition at Somerset House explore the ways of responding, coping with and resisting the capitalist mechanisms of shrinking and controlling our sense of time.

The main focus in 24/7 are the “non-stop processes” of our contemporary culture, and it recognises sleep as pretty much the only time we can unplug from technology, even this time is becoming scarcer and scarcer. The different sections in the show are inspired by Jonathan Crary’s book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. The show is in dialogue with the author’s observations of capitalism’s influence on our everyday lives, creating illusions of timelessness, disorientation and relentless pursuits of capturing, monetising and consuming.

In Marcus Coates’ Self Portrait as Time (2016), the artist’s finger follows the second hand on his wristwatch, creating the illusion of him actually moving it. The work evolves in the space and is a looped video, but also works as a clock, counting time as it passes and constantly reminding the visitors and staff about it. Admittedly, the artistic process at times felt like a trance, and Coates kept loosing the sense of boundaries between himself and the clock.

Benjamin Grosser’s Order of Magnitude (2019), a film containing excerpts of Mark Zuckerberg’s interviews, covering the earliest days of Facebook in 2004 up to Zuckerberg’s appearances before the US Congress in 2018, these recordings reveal what’s changed and what hasn’t changed about the way he speaks and what he says. The film shows him boasting the enormity of Facebook, where the edits present us with him repetitively announcing “more, more, more, growth, more than a billion, much bigger, another billion, more than a hundred billion, more efficient, growing, even more, growing by 50%, billion, more billions, many many more”.

Many have become disillusioned with Silicon Valley and its technology based corporations, and the systems and platforms, which they have co-created at the expense of our privacy. The problem is, we are the silent workforce that these companies feed on. By giving away raw data for analysis and material extraction, we fuel the machine of surveillance capitalism. Unsurprisingly, this is reflected by a significant portion of artworks in the exhibition, which are concerned with what the contemporary meaning of labour is now.

As we enter the age of acceleration and automation, much of our labour is done with the help of machines. As this happens more we will need to keep re-evaluating our position in the process. On the one hand, 24/7 seems to portray humans as slaves to the machines, while our lifestyles are twisted, over full, and packed with too much stuff. Esmeralda Kosmatopoulos presents us with her sculptures of various configurations of empty hands, the fingers arranged to show them presumably texting, holding a phone and sliding up the screen. (Fifteen Pairs of Mouths, 2016-19).

Then we have Tega Brain’s, Unfit Bits (2015), pointing to constant connectedness; relentlessly moving metronomes stimulating smartwatches for those whose insurance forces them to rely on the health and physical performance data, and then Jeremy Bentham’s famous 19th century drawings of the Panopticon.

Many of the artworks in the exhibition work to debunk the myth of immaterial labour. For instance, this is poetically illustrated by Alan Warbuton’s Dust Bunny (2015), a sculpture comprised of finely milled angora-like dust harvested from the inside of ten 3D animation workstations at visual effects studio Mainframe. The volume of dust here represents an estimated 35,000 hours, or 4 years, of constant rendering and processing.

The distressing nature of social media is shown through the lens of architecture rationalising human relations in Pierre Huyghe’s The House Project (2001). The film shows computer-generated high-rise blocks with window lights blinking in the rhythm of the electronic soundtrack by Finnish techno duo Pan Sonic and French sound artist Cédric Pigot. As the track progresses, the beat becomes heavier, faster and the lights begin to run up and down the stairs, across all floors. The two apartment blocks become musical instruments with flashing diodes, generating an eerie and creepy soundtrack.

Among this horde of artworks, there are some which allow space for contemplation. Finnish artist Nastja Säde Rönkkö, one of the Somerset House Studios’ residents, spent 6 months living and working in London without using Internet. Her letters, souvenirs and received gifts are displayed in a glass cabinet, alongside the film documenting her experiences of moving around the city and reflections on the difficulties she had encountered when she refused to use and benefit from the web. In Catherine Richards’ Shroud Chrysalis I (2000), the visitors are invited to be wrapped in a copper blanket by the gallery attendants, and savor time off technology, as the blanket blocks out electromagnetic signals emitted by mobile devices.

The show proposes a retreat and asks us to contemplate the world’s speed and our disconnectedness from a sense of time. At the same time, it overwhelms the space with an abundant amount of artworks, with over 50 beautiful and innovative artworks on display. And, while this diversity is one of the exhibition’s biggest strengths and should be applauded, it is also a weakness. It involved much shifting about and squeezing between displays, and tireless engagement. One’s experience of this ranged from disinterest to awe, as well as disorientation.

The exhibition’s theme is about time. It literally demands a fair chunk of time forcing the visitor to slow down and re-evaluate experiences and perceptions of what time means to us when its so deeply a part of the systems that are accelerating, alongside capitalist means. This big show offers us no way out of the contemporary trappings of capitalism and its intertwined, connections with time. But, it has opened up a space where we can consider it in a context where it involves the mediums and processes of, art, technology, and varied philosophical, political interjections, and observed outlooks. The exhibition presents us the visitor with an opportunity to reflect on the connected world through the experience of disconnectedness which has successfully been woven into the exhibition’s concept. The works shift and turn not with one message, but as oracles, or reminders that, there is a possibility of living differently, where we can create communities in alternative ways and highlight the value of questioning, while critically experimenting with our methods of communication. Time or capitalism, are not the main messages, but it’s more about what we do with them. It is an important and necessary exhibition that needs our immediate attention.

24/7:

A WAKE-UP CALL FOR OUR NON-STOP WORLD

is at Somerset House in London until 23 Feb 2020

somersethouse.org.uk/whats-on/247

Featured Image:

‘Slogans for the 21st Century’

Courtesy of Douglas Coupland

and Maria Francesca Moccia, EyeEm

via Getty Images

Editors present: Yiannis Colakides, Marc Garrett, Inte Gloerich

State Machines: Reflections and Actions at the Edge of Digital Citizenship, Finance, and Art

Today, we live in a world where every time we turn on our smartphones, we are inextricably tied by data, laws and flowing bytes to different countries. A world in which personal expressions are framed and mediated by digital platforms, and where new kinds of currencies, financial exchange and even labor bypass corporations and governments. Simultaneously, the same technologies increase governmental powers of surveillance, allow corporations to extract ever more complex working arrangements and do little to slow the construction of actual walls along actual borders. On the one hand, the agency of individuals and groups is starting to approach that of nation states; on the other, our mobility and hard-won rights are under threat. What tools do we need to understand this world, and how can art assist in envisioning and enacting other possible futures?

This publication investigates the new relationships between states, citizens and the stateless made possible by emerging technologies. It is the result of a two-year EU-funded collaboration between Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL), NeMe (CY), and a diverse range of artists, curators, theorists and audiences. State Machines insists on the need for new forms of expression and new artistic practices to address the most urgent questions of our time, and seeks to educate and empower the digital subjects of today to become active, engaged, and effective digital citizens of tomorrow.

James Bridle, Max Dovey, Marc Garrett, Valeria Graziano, Max Haiven, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Francis Hunger, Helen Kaplinsky, Marcell Mars, Tomislav Medak, Rhea Myers, Emily van der Nagel, Rachel O’Dwyer, Lídia Pereira, Rebecca L. Stein, Cassie Thornton, Paul Vanouse, Patricia de Vries, Krystian Woznicki.

Join editors Yiannis Colakides, Marc Garrett, Inte Gloerich, contributors Max Dovey and Helen Kaplinsky, and respondent Ruth Catlow on Tue 23 Apr from 18.00-20.30 for short presentations with plenty for time for discussion.

This event is hosted at Furtherfield Commons in Finsbury Park*

*Please note this is a separate building to our Gallery and is at the Finsbury Park station entrance to the Park.

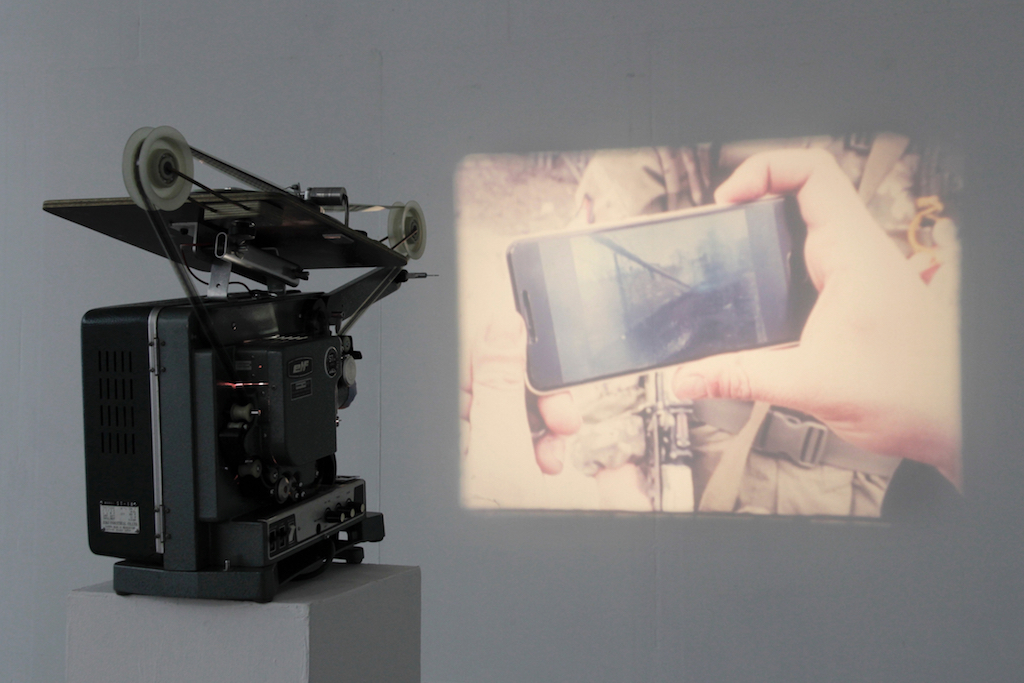

Referring to Ernst Jünger’s proto-fascist concept of the ‘front experience,’ Dani Ploeger’s fronterlebnis takes us to a frontline where digital consumer culture and traditional warfare meet. Combining filmed footage of a journey to the frontline in the Donbass War, Ukraine, alongside vintage military paraphernalia, Ploeger puts the artist in the field with the ‘real’ soldier. These soldiers are men from the far-right Ukraine Volunteer Corps, affiliated with the Right Sector, and remind Ploeger of ‘the weird and wonderful mix of action heroes in Sylvester Stallone’s Expendables series, albeit without the body builder physiques and less carefully manicured.’ Here, Ploeger not only conceives an exhibition which examines the relationship between the cleanliness of modern day technology and the grittiness of traditional warfare, but also highlights wider issues around society’s continued masculinised and fetishised relationship to conducting, and, as some of these pieces show, documenting war. With Ploeger’s ‘weird and wonderful’ group made up exclusively of men, featuring masculine nom de guerres such as Bear and Carpenter, fronterlebnis is an exhibition in which masculinity is in the crosshairs as much as anything else.

The four-piece exhibition is part of Ploeger’s current exploration into the militarisation of public spaces across Western Europe in connection with our increasingly fetishised relationship with consumer technologies, and how these apparently disparate elements converge in various conflicts, ranging from the Donbass War to public security in cities like Brussels and Paris. The soldier’s body has arguably shifted in its role since the latter part of the 20th century, with the advent of sophisticated warfare technologies moving the human body away from the process of killing, at least in popular imaginations of conflict. With this development, the methods of war appear to have shifted, but it is in fronterlebnis that we are able to see how in the Donbass War in Ukraine, traditional warfare not only remains but has now become intertwined with advanced techno-consumer culture.

This juxtaposition of the old and new is present in the first piece you encounter as you enter the gallery. In Patrol (2017), Ploeger captured a firefight on his smartphone. The footage has been transferred to 16mm film and is being projected onto the wall of the gallery in a continuous loop. In the film, we see three soldiers – Bear, Carpenter and Steinar – escort Ploeger around the frontline on the edge of the destroyed seaside village, Shyrokyne. These men, in an assortment of vintage and contemporary battle array, many carrying the iconic Kalashnikov rifle, are seen sharing footage of their exploits on the frontline with each other, which they have captured on their smartphones and GoPros. Steinar, the youngest and, as Ploeger told me, the most fashion conscious in his choice of military gear, is filmed by Ploeger watching footage of the moment where he and Carpenter blow up an unexploded mortar shell. In this piece, the 16mm film echoes the era of the weapons that the men are carrying. The manner in which this film is projected reveals the peculiarity of watching a modern day firefight where many of the weapons and uniforms are from the Soviet era, but the men are astute in their engagement of consumer technology in order to document their experiences of the conflict. In Patrol, the Kalashnikov and the smartphone appear to have made an unlikely pairing.

The other work in the show features such seemingly unlikely pairings of traditional paraphernalia of warfare coupled with different pieces of consumer technology. In artefact (2017), the wooden handguard of a Kalashnikov assault rifle is exhibited like an archaeological artefact. Presented on a white plinth, encased in Perspex glass, you can see that the wood of the handguard has been worn with the indents of many hands, signalling its intense use. This carefully exhibited object is just one half of this piece though. The other half consists of digital video animation in which a high-resolution 3D scan of the handguard is inserted onto a digital model of an AK-47. Presented on a large television screen, the digital model, set against a standard blue sky backdrop reminiscent of game development engines, highlights how many of us only come into contact with these types of weapons in a digitised form; whether that be in video games or through action movies. Ploeger’s engagement with firearms here reminds me of some of his past work that seems to suggest an interest in these weapons in relation to masculinity and phallic imagery. Dead Ken /Less Pink (2016), a short video installation in which Ploeger fires a small revolver at a Ken doll, speaks to the seemingly indelible relationship between firearms and masculinity. When seen in relation to this video installation, artefact signals an enduring fascination in our shared social psyche with these weapons, but also speaks to how these weapons continue to be consumed and represented in relation to masculine identities.

In worse than the quick hours of open battle, was this everlasting preparedness (2017), we can see a more tangible engagement with the co-existence of war artefacts and digital technology. Held in the front pocket of a Soviet army backpack from the Afghanistan War period is a damaged tablet computer which displays a bouncing screensaver, featuring a piece of text from Ernst Jünger’s proto-fascist novel Storm of Steel (1920). Jünger describes his experiences of fighting on the frontline during the First World War and the title of this piece is a translation of the text we see displayed on the tablet. Here, the mediatised depictions of war that are so pervasive in popular culture are delineated from the lived experience of Jünger, who discusses this perennial notion of prepared waiting that is a common, though rarely shown, aspect of war. Here, the worn backpack which has been roughly patched and repaired, presumably by the hands of the man to which it used to belong (men’s hands are for holding guns rather than sewing needles this bag appears to suggest), holds the similarly worn and damaged tablet. These damaged items speak to Ploeger’s past work with electronic waste, which explored our society’s proclivity for abandoning technologies when they become outdated or damaged. In this exhibition, however, Ploeger brings together the old and new, using pieces of (almost) electronic waste alongside other material artefacts to further explore the relationship between the material and digital.

The largest piece of the exhibition, frontline (2016-17), deploys this new and ‘clean’ technology in order to take us to the frontline. The work consists of a big wooden enclosure of about 5 by 5 meters which can be entered through a small opening on its side. The entirely white inside of the space is brightly lit by a large grid of office LED lighting that hangs above it. This enclosed space speaks to the ways in which Westernised notions of conducting war are now considered clean and sterile as a result of the technology that they use. Before entering the space, you are asked to place foot coverings over your shoes, as if you would be entering a sterile space, a futile gesture it would seem as the same coverings are used again and again. This action, however, also references the cultural shift in how Western nations like to represent high-tech warfare as a clean affair.

When you enter the enclosure a sensor is triggered and a soundscape of intense gunfire and explosions suddenly surrounds you. It is only until the you place the VR headset on to your eyes that this soundtrack, fit for an action movie, ceases. Roused by the noise, you are then met with a starkly contrasted image to what was suggested through the preceding gunfire soundscape. Rather than an action scene which complements the sounds previously heard, you enter an uneventful immersive video of soldiers smoking and sitting on the frontline. Using an intricate combination of partial video loops, the men appear to be on a never ending smoking break. frontline, subverts our spectacular expectations of warfare and VR technology by creating a VR experience that – after using sound to further heighten our expectations – foregrounds the mundanity of waiting for something to happen that makes up most of everyday life in an area of conflict.

In frontline, as in all of the pieces that are exhibited as part of fronterlebnis, Ploeger subverts our expectations by combining and repurposing technology to make us question our relationship with our technological devices and how we perceive and engage with them in everyday life. In addition to its examination of digital culture, fronterlebnis also seems to suggest that warfare remains a man’s game. We encounter men who are still prone to having their boy’s toys, but it would seem that in this case they are a GoPro in one hand, and a Kalashnikov in the other. Ploeger’s documentation of these conflicts, made with his own personal technological devices, arguably envelopes him in similar mechanisms of fetishization as the soldiers he was with. Neither soldier nor artist seem able to extract themselves from the seductive realm of audiovisual gadgets and self-mediatization in an era of omnipresent digital consumer culture that even reaches as far as the trenches of a dirty ground war.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

FREE DOWNLOAD OF EXHIBITION DOCUMENTATION

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

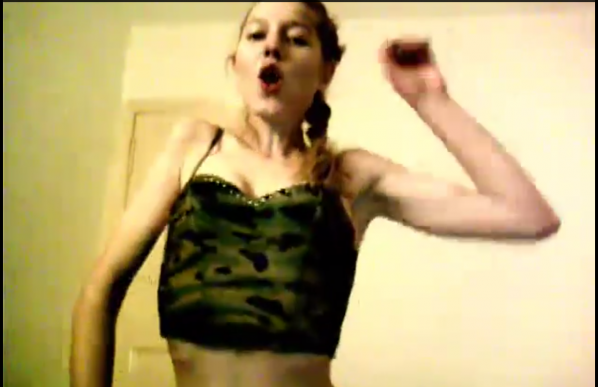

Featuring Katriona Beales and Fiona MacDonald.

The exhibition and research project Are We All Addicts Now? explores the seductive and addictive qualities of the digital.

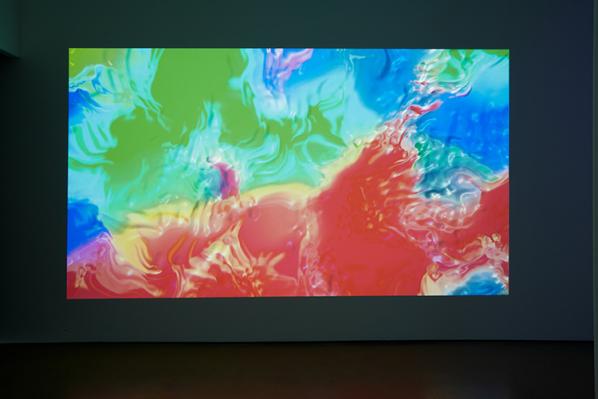

Artist Katriona Beales’ work addresses the sensual and tactile conditions of her life lived online: the saturated colour and meditative allure of glowing screens, the addictive potential of infinite scroll and notification streams. Her new body of work for AWAAN re-imagines the private spaces in which we play out our digital existence. The exhibition includes glass sculptures containing embedded screens, moving image works and digitally printed textiles. Beales’ work is complemented by a new sound-art work by artist and curator Fiona MacDonald : Feral Practice.

Beales celebrates the sensuality and appeal of online spaces, but criticises how our interactions get channeled through platforms designed to be addictive – how corporations use various ‘gamification’ and ‘neuro-marketing’ techniques to keep the ‘user’ on-device, to drive endless circulation, and monetise our every click. She suggests that in succumbing to online behavioural norms we emerge as ‘perfect capitalist subjects’.

For Furtherfield, Beales has constructed a sunken ‘bed’ into which visitors are invited to climb, where a glowing glass orb flutters with virtual moths repeatedly bashing the edges of an embedded screen. A video installation, reminiscent of a fruit machine, displays a drum of hypnotically spinning images whose rotation is triggered by the movement of gallery visitors. Beales recreates the peculiar, sometimes disquieting, image clashes experienced during her insomniac journeys through endless online picture streams – beauty products lining up with death; naked cats with armed police.

Glass-topped tables support the amorphous curves of heavy glass sculptures, which refract the multi-coloured light of tiny screens hidden inside. Visualisations of eye-tracking data (harvested live from gallery visitors) scatter across the ceiling. On the exterior wall of the gallery, an LED scrolling sign displays text Beales’ has compiled, based on comments from online forums about internet addiction.

Where Beales addresses the near-inescapability of machine-driven connection, Feral Practice draws us into the networks in nature. Mycorrhizal Meditation is a sound-art work for free download, accessed via posters in Furtherfield Gallery and across Finsbury Park. MM takes the form of a guided meditation, journeying through the human body and down into the ‘underworld’ of living soil, with its mycorrhizal network formed of plant roots and fungal threads. It combines spoken word and sound recordings of movement and rhythm made in wooded places. Feral Practice complicates the idea of nature as ‘ultimate digital detox’, and alerts us to the startling interconnectivity of beyond-human nature, the ‘wood-wide-web’ that pre-dates our digital connectivity by millennia. (Download Mycorrhizal Mediation here)

Are We All Addicts Now? has been developed in collaboration with artist-curator Fiona MacDonald : Feral Practice, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett.

Glowing light of screens makes us #addictsnow – they are the mini-suns we bask in to keep away the dark https://t.co/jedrDUE2ZWpic.twitter.com/BmTTbFckFp

— furtherfield (@furtherfield) July 27, 2017

View more of the comissioned gifs and tweets here

In the run up to the exhibition, artists Charlotte Webb and Connor Rigby have been commissioned to produce a series of gifs and tweets to stimulate debate around the designed-for-addiction nature of digital devices, and the ethics and politics that surround this. Join the conversation @furtherfield on Twitter and Instagram using the hashtag #addictsnow

Accompanying the exhibition, a book designed by Stefan Schafer and edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, brings together Beales’ and MacDonald’s artwork and writing with essays from contributors in the fields of anthropology, digital culture, psychology and philosophy. This book is the first interdisciplinary study of the emerging field of internet addiction. Contributors will discuss their essays at a symposium convened by Vanessa Bartlett at Central Saint Martins in November 2017. Advanced copies of the book are on sale at the Liverpool University Press website https://liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/100809

Beales’ work ‘Entering the Machine Zone’ has been co-commissioned with Science Gallery London. An iteration of the work will be presented as part of HOOKED, the opening season of the new Science Gallery London, curated by Hannah Redler.

Exhibition Tour of Are We All Addicts Now? with Ruth Catlow and Katriona Beales

Saturday 16th September 2017, 2-4 pm

Furtherfield Gallery

Join Furtherfield co-director Ruth Catlow and artist Katriona Beales to find out more about the works featured in the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? and to discuss the issues that it raises around digital addiction and online behaviour.FREE | booking essential

Late Night Opening & Film Screening

Friday 29th September 2017, 5 – 8.30pm

Furtherfield Gallery & Commons

A late night opening of the Are We All Addicts Now? exhibition, followed by a screening of artists’ moving image work that has informed the development of the exhibition.

Gallery Open: 5 – 7pm

Screening: 7 – 8.30pm

FREE | booking essential

Mycorrhizal Event with Fiona MacDonald : Feral Practice

Saturday 21st October 2017, 2 – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

Fiona MacDonald: Feral Practice presents a lecture, a performance, and a fungi walk. Informed by the history, art and science of human-fungal relations, these experiences explore themes of reciprocity, intuitive and nonverbal interconnection between people, psychedelic consciousness, fungal songs, shamanic journeying, and plant communication.

FREE | booking essential

Visual Matrix Workshop with Vanessa Bartlett

Thursday 2nd November, 4 – 6.30pm

Furtherfield Commons

Join curator Vanessa Bartlett for a research workshop responding to works in the Are We All Addicts Now? exhibition. The visual matrix is a new psychosocial research technique that we are using to generate audience response to this project. Content generated during this session will inform our evaluation of the exhibition.

For more information and to book your place contact info [at] vanessabartlett.com

FREE | email v.bartlett [at] unsw.edu.au to book your place.

Are We All Addicts Now? Symposium and Book Launch at CSM

Tuesday 7th November, 6.30-9pm

Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, 1 Granary Square, London, N1C 4AA

This event celebrates the publication of Are We All Addicts Now? Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones and will feature presentations from many of the book’s key contributors who include:

During the symposium, psychologists, philosophers and artists come together to discuss the emerging diagnosis of internet addiction. Taking into account our precarious economic and political climate, they will ask whether internet addiction should be understood as a form of illness, or simply a sensible adaptation to our current environment? As increasing numbers of people struggle to moderate their online behaviours, this event will also explore artists’ strategies for counteracting the seductive, addiction-making qualities of digital space.

Convened by curator Vanessa Bartlett

Presented in partnership with Central Saint Martins Art/Design and Science Research Group

The book, ‘Are We All Addicts Now?’ is available from Liverpool University Press: liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/100809

See photos from the Symposium and Book Launch

See a recording of the Symposium and Book Launch – Part 1 | Part 2

£4 – £7 | booking essential

Katriona Beales is an artist who makes digital artefacts, moving image and installation, stressing the physicality of digital life. Are We All Addicts Now? develops Beales’ 2015 work ‘White Matter’ (a FACT commission for ‘Group Therapy: Mental Distress in a Digital Age’) which is showing at the University of New South Wales, Sydney as part of Anxiety Festival (Sept 2017). Beales’ received an MA from Chelsea College of Arts and has an artist profile on Rhizome.org

www.katrionabeales.com

Fiona MacDonald is an artist, curator and writer specializing in human-nonhuman relationship. As Feral Practice, she works in co-production with a collective of human and nonhuman persons. Current projects include Foxing, (see PEER London, 2017) Ant-ic Actions (see Ethical Entanglements, Bloomsbury Press, forthcoming) Homo Mycelium, and Wood to World (London, Kent, Aberdeen 2015-17).

www.feralpractice.com

Vanessa Bartlett is a researcher and curator based between Australia and the UK. She studies and teaches at UNSW Art & Design, Sydney where her research investigates connections between digital technologies and mental health through reflective curatorial practice. Her recent exhibition Group Therapy: Mental Distress in a Digital Age showed at FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), UK in 2015 and opens at UNSW Galleries Sydney in September 2017.

www.vanessabartlett.com

Dr. Charlotte Webb is an artist and deviant academic. She speaks and exhibits internationally, focusing on the web as a medium for creative practice, critical thinking and collective action.

Furtherfield is an internationally renowned arts organisation specialising in labs, exhibitions and debate for increased, diverse participation with emerging technologies. At Furtherfield Gallery and Furtherfield Lab in London’s Finsbury Park, we engage more people with digital creativity, reaching across barriers through unique collaborations with international networks of artists, researchers and partners. Through art Furtherfield seeks new imaginative responses as digital culture changes the world and the way we live.

“There is no other gallery like Furtherfield. Situated in the middle of Finsbury Park they attract people from all walks of life and focus on contemporary technology and how it affects the lives of people and the world we live in.” (Liliane Lijn, artist)

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

Thanks to:

The Wellcome Trust

Arts Council England

Science Gallery London

Central Saint Martins

BF Skinner Foundation

Haringey Council

Bruce Marks (glass artist)

Rob Prouse (raspberry Pi and AV technician)

Choose Your Muse is a series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

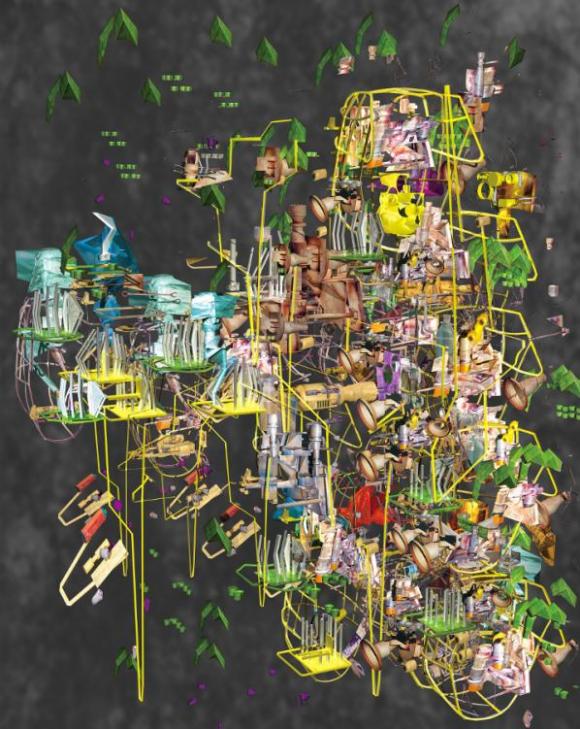

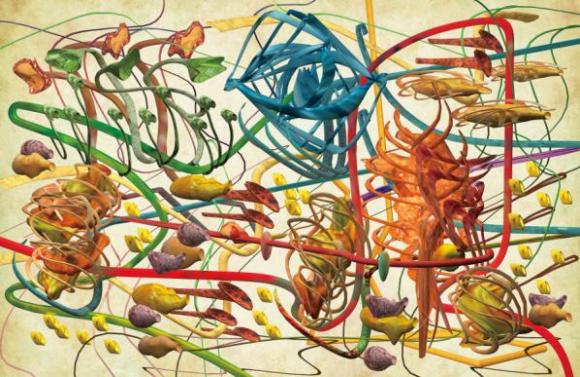

Ryota Matsumoto is a principal and founder of an interdisciplinary design office, Ryota Matsumoto Studio, and an artist, designer and urban planner. Born in Tokyo, he was raised in Hong Kong and Japan. After studies at Architectural Association in London and Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art in early 90’s, he received a Master of Architecture degree from University of Pennsylvania in 2007. Before establishing his office, Matsumoto collaborated with a cofounder of the Metabolist Movement, Kisho Kurokawa, and with Arata Isozaki, Cesar Pelli, the MIT Media Lab and Nihon Sekkei Inc. He is currently an adjunct lecturer at the Transart institute, University of Plymouth.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Ryota Matsumoto: As I have collaborated with the founders of the Metabolist movement of the 60s, Kisho Kurokawa and Arata Isozaki, and had the opportunity to meet Cedric Price at Bedford Square, I am keenly aware of the participatory techno-utopian projects by the Situationist International group. Some of the projects by Japanese Metabolism, Yona Friedman, and Andrea Branzi drew inspiration from the concept of unitary urbanism and further developed their own critical perspectives. Their work has helped me to create my own theoretical platform for the status quo urbanism and its built environment.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

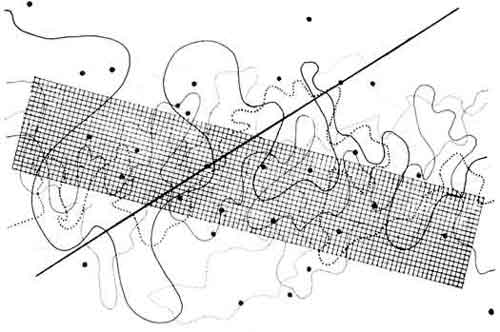

RM: I identify with the free-spirited and holistic approaches of these theorists on the relationship between language, narrative, and cognition. They embraced a wide range of media for visual communication that simultaneously defied categorization as either art or architecture and denounced the rigid policy-driven urban planning. Who would have thought of using photomontage, computer chips, PVC, or anything else they could get their hands on for architectural visualization in those days? Furthermore, their urban strategy of mobile/adaptable/expandable architecture and the theory of psychogeography dérive resonate with my own creative thinking. I interpret urbanization as the outcome of self-generating, spontaneous and collective intelligence design process and believe that the strategic use of hybrid media with incorporation of multi-agent computing provides an alternative approach for both art and design practice.

MG: How is your work different from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

RM: The utopian aspirations of the groups in the 60s were very much the product of the counter-cultural movement of the time: they were politically engaged and had optimistic outlooks for technology-driven progress of cities. In contrast, while I tend to address the current socio-cultural agendas of urban and ecological milieus, my work doesn’t necessarily evoke or represent the utopian or dystopian visions of spatial cities.

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

RM: I explore and question both sustainable and ethical issues of the urban environment that have been influenced by the socio-political realities of the Anthropocene, using visual/cognitive semantics, analogical reasoning, and narrative metaphors. As human population and energy use have grown exponentially with great acceleration, the interactive effects of the planet transforming processes on the environment are impending issues that we have to come to terms with. Thus, my projects hinge on how trans-humanism, the emergence of synthetic biotechnology, and nano-technological innovations can help us respond to the current ecological crisis.

“The themes of my work hinge on how the scientific tenets of trans-humanism, the emergence of synthetic biotechnology and Nano technological innovations might respond to the Anthropocene epoch, and, eventually foster critical thinking in relation to the underlying agendas of the increasing dominance of human-centric biophysical processes and the subsequent environmental crisis.” [1] (Matsumoto 2017)

With my recent work, the symbiotic interplay of the advanced biosynthetic technologies and the preexisting obsolete infrastructures has been explored to search for an alternative trajectory of future environmental possibilities. In short, new technologies can complement old ones instead of completely replacing them, to avoid starting over from a blank slate or facing further ecological catastrophes.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

RM: I was fortunate enough to experience firsthand Hong Kong’s rapid urbanization driven by the staggering economic growth throughout 70s and early 80s. In hindsight, it could be called the beginning of rising prosperity in the Pearl River Delta region. I was fascinated by the fact that both the unregulated Kowloon Walled City and the newly-built Shanghai Bank Tower stood only a few miles apart from each other around the same period. They could be seen as two sides of the same coin, as they both represented the rapid and chaotic economic growth of Hong Kong at that time. It suddenly dawned on me that the juxtaposition and coexistence of polar-opposite elements connoted both visual tension and harmony in a somewhat intriguing way, regardless of their nature, function, and field. That contradiction nurtured and defined my own aesthetic perceptions in both visual art and urban design.

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

Although it might sound like a career detour at first, it is always helpful to go off the beaten path before starting out as an artist. In my case, my experience as an architectural designer and urban planner certainly helped me to break the creative mold and approach my work with a broader perspective. Even now, I still firmly believe that it is always helpful to learn and acquire the wider knowledge and skills from other fields, and that opening up your mind to new ideas will allow you to discover your own unique path in your life.

RM: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

The retrospective of Le Corbusier’s work is the last exhibition I’ve seen and it was very fascinating. He is a great innovator, who had managed to continually reinvent himself to stay ahead of the curve over the course of his life. If you are interested in 20th century architecture encompassing early modernism and the Brutalist movement, it is definitely worth visiting.

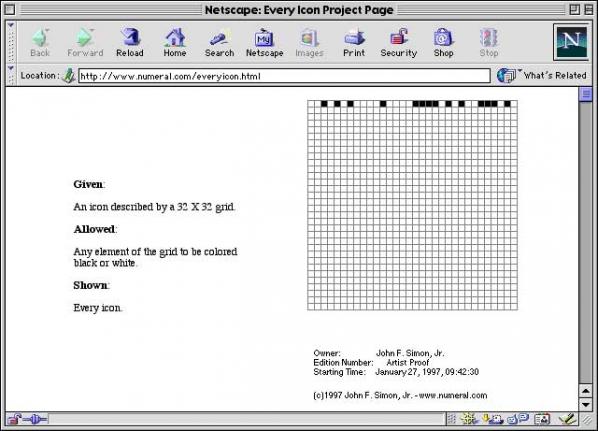

The productive alliance between instruments of computing techne and artistic endeavour is certainly not new. This turbulent relationship is generally charted across an accelerating process outwards, gathering traction from a sparse emergence in the 1960s.[1] Along the way, the union of art and technology has absorbed a variety of nomenclatures and classifiers: the observer encounters a peppering of computer art, new media, Net.art, uttered by voices careening between disparagement, foretelling bleak dystopian dreams, or overflowing with whimsical idealism. Once reserved for specialist applications in engineering and scientific fields, computing hardware has infiltrated the personal domain.Today’s technology can no longer be fully addressed through purely permutational or systematic artworks, exemplified in 60’s era Conceptualism. The ubiquity of devices in daily life is now both representative and instrumental to our changing cultural interface. Technologies of computing, networks and virtuality provide extension to our faculties of sense, allowing us phenomenal agency in communication and representation. As such, their widespread use demands new artistic perspectives more relentlessly than ever.

I, and no doubt many other academic observers, watched the Pokemon Go augmented reality (AR) game erupt into a veritable social phenomenon this year. The rapid global uptake and infiltration of AR in gaming stands in contrast to new media arts, still subject to a dragging refractory period of acceptance and canonization. Perhaps this is emblematic of a conservative art world that persistently recalls an ebullient history of computer art practices. In this lineage, many a nascent techno-artistic breach has been accused of deliberate obfuscation, of cloaked agendas under foreign (‘non-art’) orchestrations.[2] The seductive perceptual forms elicited through augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and immersive reality (IR) devices can be construed as mere spectacle, vulnerable to this type of critique. “Google Daydream” and “HoloLens” chime with a poetic futurism; cynics might instead see ready-to-wear seraphs veiling the juggernauts of Silicon Valley. However, the current groundswell in altered reality discourse may signal a divergence from such skepticism. One recent exemplar is Weird Reality, an altered reality conference that aimed “…to showcase independent and emerging voices, creative approaches, diverse and oftentimes marginalized perspectives, and imaginative and critical positions…. that depart from typical tech fantasies and other normative, corporate media.”[3] This is representative of the expanding, international trend towards artistic absorption of new media and technologies. It is a turn that emphasizes the potential for cultural impact, experimental daring, and even conjures the spectre of the avant-garde: radical transformation.

One of my PhD supervisors wisely admitted “…to stand out, the human artist must be more creative, diversified and willing to take aesthetic and intellectual risks. They can and must know the field they are creating in practically and philosophically, and confidence in their position and contribution to it is essential.”[4] Through this earnest lens, artistic production can serve as a conduit for ideas ranging from the speculative to the revelatory. In these divinations, we might trace a path through the sprawl of new media discourses, and find ourselves somewhere unexpectedly revitalizing. I hope to mark out some of this territory from a position of mediation. I want to invite art and art theory into an arena of uninhibited collusion, using critical writing to facilitate the exchange between digital media theorists and artistic practitioners in the most open sense. Furtherfield.org offers an allied platform for the aims of the Theory, Meet Artist [5] project, articulated here in an interview dialogue.

Originally published in The Fibreculture Journal, Edwina Bartlem’s 2005 article Reshaping Spectatorship: Immersive and Distributed Aesthetics proposes that immersive artwork practices have transformative potential. Across a range of modalities, these works can influence perceptions of ourselves and our extended digital presence in a variety of scenarios and configurations. Whilst participating in such practices, we are prompted to consider IR encounters as form of mediation around our human embodiment, subjective identities and cultural interactions. Bartlem touches on ideas of prosthesis and sensorial augmentation within these immersive experiences. Creation of a synthetic environment is posited as an opportunity for deepened self-reflexivity and awareness.[6] In parallel, a spectrum of narratives around the technologically adapted ‘post-human’ emerge. Their tone and reception hinges upon the artist’s individual performance in roles such as programmer, director, composer or overseer to such works.

Rachel Feery is an Australian artist interested in the intersection of visual art, soundscapes, video projection, experiential installations and technology. Her artistic practice explores alternate realms, the meditative headspace, ethereal imagery and immersive environments. For this interview, Bartlem’s paper is positioned alongside and in dialogue with Feery’s work, Clearing the Cloud.

Clearing the Cloud is described by the artist as “… a multi-sensory work inviting pairs to cloak-up, complete a circuit, and experience simultaneous mapped projections visible through a hooded veil. The artwork aesthetic draws from esoteric sciences and holistic health practices. The environment is intimate, quiet much like a room where one would go to receive therapeutic treatment.

Two participants at a time are invited to cloak up, remove their shoes, and step onto sensors on the ground to generate a circuit of light and sound. Starting with a ‘personalised scan’ followed by a projection of light and sound, all visible and audible within the suit itself, the individuals can either interact with each other or be still and silent. The robe, constructed of a semi-translucent, lightweight fabric with a soft skin-like texture acts as a supplementary skin. One’s field of vision is slightly inhibited by a lightweight mesh that both creates a screen-vision as well as the ability to see through it.”

Jess Williams: I first came into contact with your practice during your talk for Media Lab Melbourne in September this year. You chronicled your process, influences, past works and brought us to Clearing the Cloud. I was struck by the experiential intimacy of the project, and the immersive qualities that you deployed though staging it. In her paper, Bartlem suggests that participants in immersive practices cannot be immersed without being affected by the environment on perceptual, sensory, psychological and emotional levels. What kind of sensorium did you want to create for Clearing the Cloud, and did you contemplate the possibility of this type of affective influence on your participants?

Rachel Feery: In one sense, the project came about while I was thinking about art as therapy, and thinking about technology that has the potential to create a meditative space. The site of the exhibition, Neon Parlour, was previously a centre for healing and meditation. I wanted to create an intimate room that would reflect the building’s history. Speaking of the sensorium, I was drawing from esoteric sciences, looking at auras, and Reiki practices whereby chakras are ‘cleared’. This is all reflected in the visual and environmental elements of the work, but ritual aspect is key. It’s important for participants to enter the artwork through the process of putting the garment on. The ritual is something you have to experience with someone else, and there’s a synchronicity between the people who participate. If either person takes their feet off the sensors, the ‘therapy’ is reset. It becomes apparent that there’s a level of commitment to it, that there’s a trust involved. If one person backs out, the interaction stops and resets.Clearing the Cloud ultimately asks participants to commit and experience the work together. Some participants responded that they felt lighter, and that time had passed out of sync with the seven minutes that had passed in reality. I thought this was an interesting reaction when nowadays, our attention spans are said to be dwindling. I feel there’s something significant in a lot of those esoteric sciences.

JW: Bartlem maintains that immersive art offers more than pure escapism into a constructed simulacra. These types of artworks can also elicit a type of self-awareness or meditation on perception and one’s own agency in the prescribed environment. I’ve noticed a strong tendency to consider transcendence, or the superhuman, in many futurist discourses around technologies that interface with the human body. This spans augmented reality, virtual environments and may well capture less conspicuous (yet ubiquitous) examples, such as fitness metrics or geolocation of the self through GPS. How do you position narratives of extending or ‘hacking’ embodiment within your own work?

RF: There’s an aspect of being both physically present and also outside of yourself whilst engaged in Clearing the Cloud. As a participant, you find yourself looking through a meshed veil that’s being projected on, and if you adjust your focus, you can see coloured projections on the other participant. This dual, simultaneous vision got me thinking about the ways that newer technologies such as AR and VR can affect what we see and the way that we see. Essentially, those applications allow you to see an environment with a filter over it. You have the sense during the ‘clearing therapy’ of an outer body experience, which is something that certain types of meditation aspire to. Escapism can imply you’re ignoring what’s happening in the outside world and going inside yourself, or elsewhere. But technology is blurring these boundaries, becoming increasingly intertwined in everyday activities, both personal and shared. You’re not really escaping if there’s an application present to assist with something, provide new information, or an augmented experience. In that sense, I would agree that it’s not pure escapism. You’re in two places at once. I would say that the word escapism has darker implications, such as detachment and avoidance of reality over a virtual space. Meditation, however, is affiliated with deeper understanding of oneself, and acceptance and appreciation of both worlds. As technology gets more advanced, I think it will have the ability to do both.

I like the idea that two people willingly participate in this scan and projection without question. I feel it relates to this influx of new technology applications that are free and that everyone’s willing to try. On the darker side, I wonder about the consequences of giving away information- effectively, parts of yourself- to participate in the unknown. I also like the idea that Clearing the Cloud is presented as a holistic therapy, a gesture of removing the build-up of accumulated information, or as protection from the data mining we’re exposed to through technological interfacing. We’re made vulnerable to hacking, but in a sense it’s not really hacking anymore, it’s just collecting what we’ve been giving. There’s such a rush to use new applications and technologies but everything is untested. Essentially people become trial subjects through their willing self-disclosure.

JW: You mentioned David Cronenberg’s 1999 film eXistenZ as a formative influence in your creative development. Underpinning the science fiction and horror themes, a specific abject revulsion is reserved in this film for prosthetic extension and modification to the human body. Could the veils (with their accompanying perceptual experiences) used in Clearing the Cloud be viewed as a form of sensory prosthesis?

RF: I would say I was more interested in the idea of accessorising tech, rather than prosthetics. I am drawn to the way that Cronenberg’s characters leave their physical body and enter another state, but again, this is quite geared towards escapism. Using the veils arose through researching a mix of religious and medical robes, futuristic fashion and science-fiction inspired fashion. They all seemed to be white. There’s also a relationship with the cloak to other forms of wearable technology. I’m interested in this – in Google Glass, VR headsets, and related items – as both a current fashion trend and also as a subtle way that technology encroaches on our day to day lives, present as we move through and see our worlds. While I perceive the cloak itself is not so much of a prosthesis, there are certain physical qualities of the material that feel both organic and synthetic. They’re made of a foggy, PVC translucent plastic: when worn, this fabric feels like a skin. The backwards-oriented hood also functions as a way to obscure the face, and presents a form of anonymity that is ultimately within the concept of ‘being cleared’ and ‘regaining yourself.’ There are other associations too: of a uniform, of being part of a community that has been cleared, or erased.

JW: Typically, when audiences are presented with new media or computer mediated artworks, they have limited access to the operational interior of the encounter. Whilst it can be argued that more traditional media or installation works also don’t completely disclose their construction or authorship, new media practices seem subject to increased scrutiny and distrust around how- and to what end- they operate. In her paper, Bartlem proposes that instead of masking the presence of technology and interface, immersive artworks tend to overtly emphasize the synthetic artifice of the experience. In regards to revealing the hierarchies of control implicit in executing works like Clearing the Cloud, how much do you wish the audience to have a certain ‘privilege of access’? For example, do you consider it necessary to directly reference programming script, hardware circuitry, or technologies of surveillance?

RF: The actual technology used in the exhibition was not necessarily about aesthetics. Hardware and devices, such as projectors and Raspberry Pis, were not elements that I wanted audience attention drawn to. Moreover, I think if you give spectators interior access, it can take away the simplicity of the art experience. The most that I would give away would be the materials visible or listed in the artwork. I actually tried my best to mask the technology, hiding cords and mounting the projectors up high to make it feel innocuous and to minimise its physical presence. Once people can identify familiar tech, there is an immediate undermining of mystical impact. For this artwork, I worked with artist and technologist Pierre Proske to write a code that triggers the projection once the sensor pads are activated. The hardware elements are present, but they’re definitely not the focus. Rather, it’s the experience itself, the meditative space created that participants are made most aware of. I think that’s why auras, and energy healing, are so fascinating: they rely on people’s ability to embrace and believe in the healing process, which in turn requires any distractions or doubts to be removed- or at least obscured. Obsfucation was deliberately built into the back-to-front hoods used in Clearing the Cloud. Restriction of the visual frame of reference was intended to encourage immersion in the experience.

JW: As we’ve discussed, the eponymous gesture of “clearing the cloud” reads as recuperative, meditative, and somewhat subversive towards strategic or commercial use of new technologies. This is a position that Bartlem suspects is endemic within artistic instrumentalisation of these types of media. Do you feel a sense of alignment with a more radical manifesto in new media practice?

RF: A lot of my ideas draw from or relate to concepts that have been proposed in science-fiction films… science-fiction is radical. Sci-fi extrapolates the current social, political or technological trends, or explores alternate models. Clearing the Cloud also proposes a need for something that hasn’t quite been quantified, a therapy to restore and protect from encounters with technology. Clouds traditionally connote lightness, and formlessness, but today they weigh heavily on us in a digital data context. We carry more and more information, and give more and more of ourselves. We’re now clouded by our metadata trails, and it’s radical to think that a therapy can address this, and return us to a state of clarity, in a literal and metaphysical sense.

JW: After your talk, I asked you a question around whether Clearing the Cloud‘s artistic narrative could function beyond a ‘closed-circuit’ proposition. Whilst Bartlem scopes immersive and telepresent practices in her paper, she doesn’t directly address works that hybridise the two concepts. She frames telepresent artworks as those that link participants from distant locations, precipitating notions of networks and a multi-user participation within art. How would a multiplicity of network relations impact on a scenario like that you have staged in Clearing the Cloud?

RF: An excellent question, and very relevant to the nature of the work. The participant’s experience centres on a propositional ‘defrag’ of their personal hard-drives, regaining clarity, allowing independent thought free from the prison of past browsing histories and metadata maps. Those in a networked community also benefit from this speculative process: the more persons ‘cleared’, the stronger the authentic connections would be. If you were to be ‘cleared’, and your online history erased, the persons closest to you would also need to be erased in order to completely eliminate any trace of you. It’s like a chain reaction. Although only two people might be scanned at a time, for a complete ‘clearing’ you would need the eventual interfacing of everyone you’ve ever come into contact with. Ideas around utopias were intrinsic to the development of Clearing the Cloud. In one view of the work, those people who have been ‘cleared’ became part of a separate, even sanctified community. This meditation was idealistic, borne of the desire to find a way to protect our identities and those of our networks when they are potentially threatened or compromised by interactions with technology.

Clearing the Cloud was originally exhibited in 2016 as part of This Place, That Place, No Place curated by Irina Asriian (Chukcha in Exile) at Neon Parlour, Melbourne, Australia.

In many of the projects by French Vancouver-based artist Nicolas Sassoon, space and how we perceive it are two of the most inquired questions; it could seem casual that he mostly makes GIFs, but looking at his works you’ll realise the necessity of reflecting on environments, both artificial and spontaneous, using such a specific format. His works ask the viewer to not stop just at the first impressions; sure, most of his GIFs are astounding in terms of animation, use of colours and shapes, but all this technical skill is employed for inquiring our position within environments – not just laptop monitors, but real, concrete buildings and dreamy contexts as well. This is just one of the many introductory points from which we can start talking about INDEX, his latest work which has been featured on the homepage of Rhizome in the first weeks of October and that can be viewed here, on his website.

FL: One of the first things that struck me about this project is the relation between hypnagogic dimensions and the technical features of GIF format. The never ending loop of events and the way in which you can change your perception of the same object are important aspects of both; I wonder what you do think about this, especially from your point of view as an artist.

NS: INDEX is representing a project space/music venue in Vancouver BC where I co-organized electronic music events in 2015. It is depicted in the process of being setup for an event titled Rain Dance which happened in August 2015. When I started working on INDEX I was curious about the process of rendering a detailed scene from memory. I had many memories of the venue during the installation phase, a few days before the event. I began to render these memories and details from the installation period within what I could remember of the overall architecture. In that regard, INDEX is an effort to recollect and fixate details about this particular space at this specific time. Some parts of the work are relatively accurate while some other parts are imaginary. The hypnagogic and effervescent visual aspect of the work is informed by this process. It’s also informed by the nature of the events that took place at this venue.

FL: Speaking of memory, what could be a connection between it and GIFs in your own opinion? What are the technical features of this format that could it make appropriate as mean to show memories? Since you mostly worked with GIFs for many years, I wonder if you started to experience events and places as objects suitable to be translated into this format.

NS: The most tangible connection I can think of between GIFs and memory has to do with the history of the web since GIF is an image format that has survived throughout the evolution of the Internet; it is an ancient species that has survived numerous cataclysms. In my work, the connection between GIFs and memory comes from a desire to reconnect with specific moments and places, to create a form of record of these memories. The representation of these memories is an opportunity to formulate mental images of architectures, landscapes and other elements into visual forms that are minimal, incomplete, and encoded. I also enjoy using the GIF format as a very subjective archive; for example, in opposition to the objectivity of 3D scans from historical artefacts. INDEX contains some historical and factual data but it’s also completely skewed by my own perspective.

FL: This is an interesting reflection; I like the concept of the GIF format behaving as a selfish gene, in terms of adaptability throughout many different contexts and times. In your own opinion, what is the reason behind the fact it has so much importance in the last 20 years (and counting)? I can’t help but think about the relation between the ways we use to connect to the internet (ie the devices we use, the span of time we stay connected, the reasons we’re connected, etc.) and the faster and faster speed of our internet connections. What do you think?

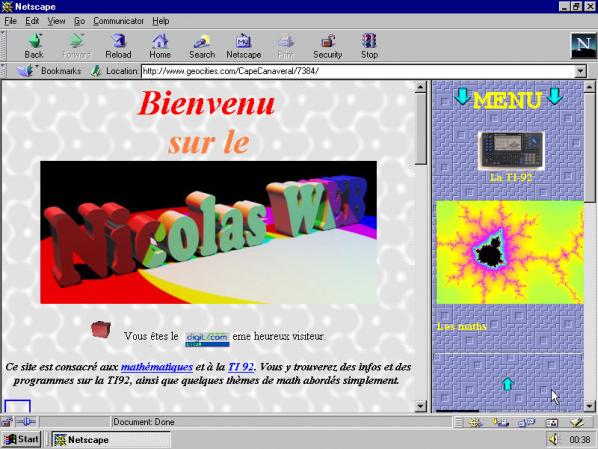

NS: The continuous presence of GIFs online has to do with the format being perfectly adapted to web environments and its relentless user applications. If you look at early HTML pages, GIFs were always a highlight; they allowed users to add dynamic elements throughout their content. Inserting animations in the middle of text, images or diagrams was a novelty. GIFs embodied that novelty; they were a simple and accessible display of something “multi-media” so they became instantly thought after, heavily used, and stored into databases. GIFs are still pervasive today in forums as image profiles or as punctuation in comments; DUMP.FM personified that within the net-art community, but if you look at any forum or social medias platform it’s still present. From a technical standpoint, the GIF format is attractive because it works like simplified video editing; you set up an image sequence, decide on the speed, and loop it forever. Aside from the APNG format – which never really took off – no other image format offers these capabilities. It covers fundamentals, from traditional animation (frame by frame) but also offers flexibility in terms of input since you can make GIFs from literally anything. The looping function has infinite fields of applications and is impactful visually, which is perfect for the attention seeking nature of Internet space.

FL: Yes, GIFs have been very important in the first years of the Web especially because they bring depth to Web environments; the fact that artists like you are bringing this format from the usual contexts (ie laptops’ monitors, smartphones’ screens, etc) to physical spaces totally makes sense to me. In both cases, we’re talking about fixed environments where the never ending GIF’s movement affects their perception. What do you think? What does it change when you work on a project that will be on display on a Web site and another one which will be hosted on the facade of a building? I’m especially thinking in terms of spaces and perception of shapes and colours…

NS: It has been a challenging process to exhibit screen-based works into physical space, mainly because screen space and physical space are so different in terms of experience. Looking at something on a laptop screen feels intimate, but watching the same thing in a gallery or museum is more of a social experience determined by the immediate architecture. I think a lot in terms of experience in my work and I’ve come to adapt this thought process for installations. I determine the scale of my installations based on the architecture in context. I work primarily with projections whose shapes and sizes references windows, doorways, or other architectural features appearing in the space. These referential elements articulate my work in space like an environment adjusted to the architecture; an added layer which plays with the configuration of the space. I often see my installations as projected sets, or giant digital props injecting imaginary scenarios within architecture. It feels like a natural extension of what I’m trying to do with screen-based works, but it also really engages with the architecture in context.

L: Speaking of the importance of GIFs in our daily online routines, I wonder if and how the so-called GIF art has been influential in respect to the broader use of this format by general public; I’m especially thinking to Simple Net Art Diagram (1997) by MTAA, to the way it used the features of this format to add a little magic to what would look like as a diagram – in other terms, do you think the irony, the cleverness and the experimental approach of the first artists working with GIFs have been understood and implemented by non-experts?

NS: I find early GIFs made by artists as influential as the GIFs made by early web designers, scientists, and other random users involved with the format. GIFs are created from pretty much anything and there has been an infinity of cross-overs in terms of influences. So many users have gone beyond the typical level of involvement with this image format, it would be presumptuous to give credit only to the artists. Still it’s amazing to see the format being acknowledged in the recent historical work on Internet Art, and I’m hoping to see many GIFs in the new Rhizome’s NET ART ANTHOLOGY! I also believe the history of GIF is a history of the vernacular which would deserve its own separate study.

FL: When you see the work, you can’t help but think of ’80s computers; in other terms, the black background and the blinking white dots and lines suggest this association. Can I ask you why you did choose this specific aesthetic?

NS: One of my interests for this type of early computer imaging has to do with the formal and optical properties of these graphics; the way they behave on screens and how they produce kinetic experiences. This is visible in works like PATTERNS where I focus on abstracted animations. Working with these out-dated graphics feels similar to working with an engraving technique or a type of craft that belongs to a certain time period. Some crafts and imaging techniques tend to be associated with specific eras. In the case of early computer graphics, their era is the end of the 20th century which I feel strongly connected to. I also look at these graphics for what they generate in terms of aesthetic experience. They are the primary visual language of the display technology we use today, and they’ve generated many revolutions in the way we perceive contemporary images.

FL: You just highlighted one important aspect of your works as whole; This makes your projects, on one hand, to look modernist as they explore how minimum information can create a kinetic effect, rooted in the belief that objects can be reduced to quantifiable patterns and shapes; and on the other, they are nostalgic, reminding us of the times when when creating digital pictures was not so dissimilar from artisanship. What do you think? Am I wrong?

NS: I’ve always been attracted to the idea of developing a craft or skill as far as possible. My focus on early computer graphics was a conscious choice in that sense. It came quite late in my practice when I felt the need to make art for my own sake, without professional incentives. My generation grew up with the first home computers and there is often a generational shift of perception when it comes to early computer graphics. For me, this aesthetic is linked to childhood, fantasy, entertainment, while for other generations it doesn’t have the same emotional input. But no matter the generation, this aesthetic has a definite “time-stamp” and most audiences will associate this aesthetic with that “time-stamp”. The early stages of my practice were very focused on how to appropriate this aesthetic, to turn it into my own visual vocabulary and to articulate it with elements inside and outside of this specific “time-stamp”. I feel many affinities to painting because of this relationship I have with the visual components of my work.

FL: Speaking of painting, the other day I was reading The Social History of Art (1951) by Arnold Hauser and one text passage struck me in relation to INDEX. “[Mannerism] allows spatial values, different standards, different possibilities of movements to predominate in the different sections of the picture. […] The final effect is of real figures moving in an unreal, arbitrarily constructed space, the combination of real details in an imaginary framework, the free manipulation of the spatial coefficients purely according to the purpose of the moment. The nearest analogy to this world of mingled reality is dream.” Now, I’m not suggesting the idea that your project is mannerist, but I can see some shared features; the way you constructed the space makes me feel a set of arbitrary rules working underneath the blinking white lights, the objects you depicted are somehow real but fixed in a non-realistic dimension. What’s your opinion?

NS: When I began this project, I wanted to develop a new direction that I approached with previous works like STUDIO VISIT. I wanted to portray a real space and make it exist within a different dimension. I was picturing an animated relic, completely isolated and playing itself indefinitely. I focused on my memories of the space and on the reasons that led me to render it. Index was a project space which felt important in the cultural landscape of Vancouver, it also had its own personality. I knew the venue would eventually disappear and be forgotten for the most part. I wanted the work to become an expressive record of this, charged with energy and subjectivity. There is also a form of nostalgia expressed in the visual language I use, and I wanted to articulate this sentiment with the work. This is what led most of my formal decisions. I worked with mental images of the space seen through a lens revealing the energy of each object, and how these objects were infused with the activity of the space. For instance, some parts of the floor were made of these very small sections of hardwood flooring, and it was an area where people used to dance. This translated into a very dynamic area in the work, like a multitude of small conveyor belts imbricated into one another.

FL: It seems to me you used isometric projection to depict the objects, a technique employed mostly in technical and engineering drawings; in fact, the scenes look real but not physically reachable, as if they exist on their own – in other terms, they look eternal, recalling the still life paintings by Italian painter Giorgio Morandi. In his case, unlabelled bottles and unrecognisable objects make the scenes unhistorical and closed in themselves; I think it’s interesting the fact you both employed similar devices to depict still life objects – although it’s clear there are many important differences between your works. What do you think?

NS: I’ve always been interested in using screen-based graphics to express the materiality of physical objects or imaginary structures. This is very apparent in early works like FREE CUTS. These works were created as sketches for sculptures, but in the end, they embodied the sculptures on screen. Like paintings, digital images exist on their own plane, and they can develop their own materiality. In my work, this materiality often manifests as a tension between the flatness of the screen and the sculptural properties of the graphics. Sometimes the work feels like it resides in its own plane of existence, like an object stuck between two worlds. This image of something stuck between two worlds is dear to me because it feels so relevant to my experiences on screens. Things can appear so tangible and so distant at the same time, so desirable yet completely unattainable. With isometric perspective, I find a lot of interesting ideas in ancient Japanese works. Isometric perspective is nothing new but it seems to hold a stronger imprint from engineering drawings and video games than from these much earlier art forms. In the case of INDEX, works like The Tale of Genji – a scroll depicting Japanese interiors from the 12th century – were very inspirational. The scroll depicts social scenes with a good level of detail, and it gives the feeling of overlooking the architecture. The vision is fragmented like in INDEX, and you have to unroll – or scroll – to see the rest of the space. These old works feel very contemporary, probably because isometric perspective has been so used in computer graphics.

When looking at the many artistic projects focused on how and why we use the internet, it’s easy to find yourself lost in a field which doesn’t show obvious, strong ties with what we normally know as “traditional art history”. This is due to historical and social reasons that emerged between the 80s, 90s and early 2000. These artists were at the vanguard of art culture and pushed at the edges of what art could be, whilst living in a post-punk and postmodernist era, and on tip of this, the arrival of the Internet in 94 changed everything. Many artists took on the challenge of what the Internet offered the world creatively, and explored it not merely as a marketing tool or a place to upload images and videos, but as a medium in its own right, inventing new technically informed, artistic tools and also building grass root led, networked art groups with new infrastructures as cultural platforms. Turning away from anything relating to the mainstream art world and what was seen as outmoded and tired traditions.

In the last decade, we’ve seen the expansion of the Internet and its use by younger generations where the medium is no longer something you exploit to change the culture, but more to integrate in traditional terms, canonical contexts.However, artist Jan Robert Leegte (born in 1973) is a very important figure to reflect upon, in order to understand this transition; while other artists of his generation were taking the internet for a non-hierarchical distributed system, he chose to explore it from a classical studies background that forged the cardinal points of his artistic research. He reflects an Internet art influenced practice which not only exists online but also in physical space. In fact, we can safely say he can be considered as one of the first Post-Internet artists. This makes him a pivotal figure in this historical segment and it’s under this light that one must visit the online exhibition On Digital Materiality (Carroll / Fletcher Onscreen, 3 August-12 September 2016). It’s a retrospective show presenting some of the most important and representative works of the Dutch artist, who wrote for the occasion an essay in which describes some of the most important aspects of his work.

Leegte says, the “materials I first used were basic HTML objects, buttons, scrollbars, frame borders, table borders, and also plain color fields and found images. I questioned what it was that rendered this practice similar to making installations rather than collages. At first it was the simulacrum of real world interactive elements (buttons, window frames, etc.). The operating system extended this haptic strategy with traditional paper-based forms, like check boxes, text fields, lists, etc, and, along with the form elements and the interactive document, led to an ecosystem of fake 3D, interactive objects.”

The work fluctuates between working on the surface and thinking in three dimensions. The same difference can be found with his use of Photoshop and HTML. If in the former case an image editing software operates directly on the final result, for the latter there is the need to know how to write code while at the same time imagine what the potential results will bring via its translation in the public space, the internet. In this sense, we do not hesitate to define Leegte as an artist who studies and uses the tools of the sculptor; he wonders how to place objects in the space, he feels the problem of contextualising a work in relation to a public and physical environment.

The perception of a substantial difference between surface and space is also proven with his interest in the basic elements of composing the digital interface (scrollbars, mouse pointers, etc). His research examines the artificial environment built by Microsoft and Apple designers. The colours and the shapes were designed to not be perceived as evident mediating agents between the user and the content – in this sense, it is interesting to note that Microsoft has often chosen a minimalist style (shades of grey, square shapes) while with Apple systems the style is usually more exuberant.