In 2019, we celebrated 150 years of Finsbury Park being the ‘People’s Park’ – a place where we can all do things together. In 2020 protests across the UK saw public artworks toppled from plinths, while the pandemic left us separated and isolated.

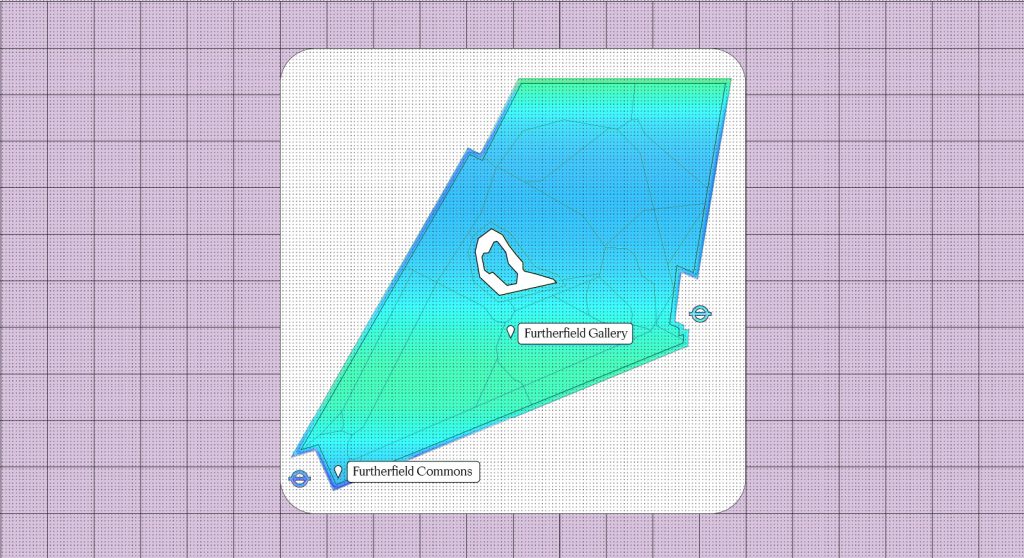

With this in mind, we launched the People’s Park Plinth this summer, as a way to re-explore our public spaces by turning Furtherfield Gallery inside out and expanding its digital arts programme beyond our walls and into the life of Finsbury Park.

We collaborated with incredibly talented artists, curators and local park members to create 3 ‘taster’ digital public artworks that speak about the park’s heritage and local stories. In May, June, and July we showcased a different digital art experience each month.

In August, the park made its pick! We will be launching a larger commission of Based on a Tree Story this Autumn, and to continue celebrating the heritage, artistry and local voices from Finsbury Park, all the ‘taster’ artworks will be available until January 2022.

If you are in Finsbury Park you can use the camera on your phone to scan the QR codes on the People’s Park Plinth (presented on the exterior of our Gallery building in the centre of the park). They are all free to access, any time, with any smartphone – but you might want to have some headphones handy too.

If you are somewhere else you can click the links on the People’s Park Plinth website to find the artworks.

It’s your park so it’s your pick!

Sign up here to get involved in choosing the artwork that most belongs in the heart of Finsbury Park next year.

Breath Mark x Lisa Hall & Hannah Kemp-Welch

Live until January 2022

A site-specific, interactive sound work creating moments of connection between strangers of all species.

Follow this sound work as it leads you across the park to meeting points for animals, plants and strangers. As you listen, consider the needs of all these inhabitants and our symbiotic relationship that is increasingly under threat. Between heartbeats, vibrations and the alignment of crossing paths, this work sounds out a shared existence, putting these moments of connectivity with strangers of all species on the People’s Park’s Plinth.

The work features interviews with volunteers at Edible Landscapes, a forest gardening group based onsite at Finsbury Park: David Berrie, Imogen Simmonds, Jo Homan, Juliette Ezavin and Theo Betts. The artists were commissioned by Breath Mark, a curatorial collective formed as a part of the Royal College of Art’s MA Curating Contemporary Art Programme Graduate Projects 2021 in partnership with Furtherfield’s People’s Park Plinth project.

Taster: In this first iteration of the artwork, one sound pathway ‘Close to the ground’ is presented.

Larger commission: If this work had been selected in the public vote in August 2021, a further two sound pathways and a trail to find them would have been revealed.

HERVISIONS x Ayesha Tan Jones

Live until January 2022

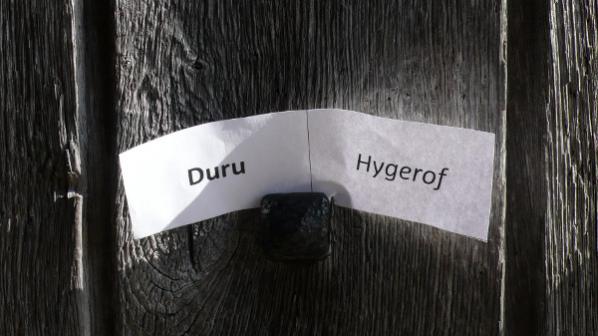

A site-specific, sonic augmented reality encounter with a digital tree sprite that tells tales of the tree’s past, present and future.

The trees of Finsbury Park are very old, and they have been witness to a lot of change and growth. If the trees had a voice, what would they share?

Based on a Tree Story brings to life Furtherfield Gallery’s nearby resident, a London plane tree dubbed the Trunk Triplets Tree, situated in Finsbury Park and the soils from which they grew, part of the now-extinct ancient woodland, Hornsey Woods. From medieval history to sci-fi futures, their stories are told through an augmented reality and audio experience, giving viewers an insight into the past, while arming them with inspiration and knowledge to help protect the trees into the future.

The project activates a digital tree sprite that shares a fable crafted through local research, site visits and discussion with Ricard Zanoli, the Park Ranger.

Taster: In this first iteration of the artwork one tree story is presented.

Larger commission: This work was selected in the public vote in August 2021 and further two tree stories and a trail of clues to find them will be revealed this Autumn.

Desree x Drumming School with Alex Dayo x Studio Hyte

Live until January 2022

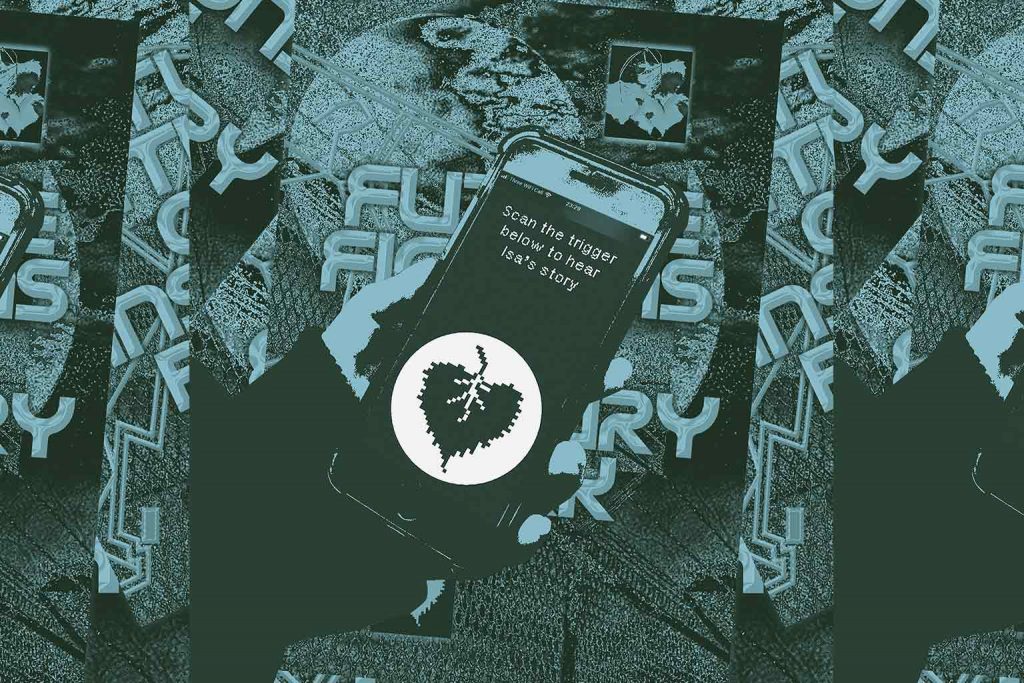

An augmented reality (AR) sci-fi zine comprising three stories that bring together writers, musicians, and local residents to explore alternative visions of a Finsbury Park of the future.

For this first iteration of the AR zine, released in July 2021 as part of the People’s Park Plinth programme, we present The Light and Dark: an audio-visual story about a fictional character, Isa, who wakes up in a home they don’t recognize, surrounded by land that feels as foreign as the sky they sit under. Isa does not know how they made it there, but they do know they have to make it home before the host finds them. With only the wisdom of Grandwa, and the feeling in their chest, Isa discovers the power of their historical connection to what was, their land.

The Light and Dark has been written by local spoken word artist and writer Desree, and is accompanied by a unique musical composition by musician Alex Dayo and his park-based Drumming School, in collaboration with David Kemp. The visual design, AR experience and animation have been developed by Studio Hyte.

Taster: In this first iteration of the artwork the start of one future fiction is presented.

Larger commission: Had this work been selected in the public vote in August 2021, this fiction would have been completed and two more would have been revealed.

In August, after experiencing all 3 digital artworks, we asked people to pick which one they thought belonged in the heart of Finsbury Park by either:

Or

The park’s pick is Based on a Tree Story, and we are working with HERVISIONS and Ayesha Tan Jones to make a bigger and better version of their digital art experience – and then we will launch it on the People’s Park Plinth this Autumn!

We wanted everyone to express an opinion – even if visitors were far away what they felt mattered too. But if voters lived locally what they felt mattered more for the vote count – so we weighted the vote for anyone using the CultureStake app within or near the park.

If you are an arts organisation you can find out more about how you can use CultureStake to drive collective cultural decision-making at your own digital and physical events.

Breath Mark is a curatorial collective initiated as a part of the Curating Contemporary Art Graduate Projects Programme 2021, Royal College of Art. Comprising six international members, Breath Mark’s curatorial practice responds to the challenges of curating remotely and explores the interconnectivity of physical and digital site-specific experiences.

Members: Kevin Bello, Jindra Bucan, Harriet Min Zhang, Soyeon Park, Yifei Tang and Yuting Tang.

As part of extended public engagement, Breath Mark has collaborated with design studio An Endless Supply, on a digital microsite acting as a reading room allowing audiences to further engage with the artwork’s themes. We encourage visitors to extend their experiences through the texts, sounds and videos here: spaces.rca.ac.uk

Lisa Hall is a sound artist exploring how environments are built-in sound, while Hannah Kemp-Welch is a socially engaged artist concerned with listening. Hannah and Lisa met at London College of Communication while studying MA Sound Arts in 2010. They share an interest in public and private spaces, and how sound and audio technologies build networks and tell stories that often can’t be seen. They have collaborated on sound art projects for performances and installations at Tate Modern, CRiSAP, and Sound Reasons Festival: New Delhi.

https://www.sound-art-hannah.com

HERVISIONS is a femme-focussed curatorial agency supporting and promoting artists working across new and emergent technologies, and platforms with a strong focus on the intersection of art, technology and culture. HERVISIONS partner with institutes, organisations and galleries to create antidisciplinary exhibitions and innovative commissions. Select partners include, LUX, Tate, bitforms and Google Arts and Culture.

IG: @hervisions_

Ayesha Tan Jones AKA YaYa Bones work is a spiritual practice that seeks to present an alternative, queer, optimistic dystopia. They work through ritual, meditating through craft, dancing through the veil betwixt nature and the other. Ayesha weaves a mycelial web of diverse, eco-conscious narratives which aim to connect, enthral and induce audiences to think more sustainably and ethically. Traversing pop music, sculpture, alter-egos, digital image and video work, Ayesha sanctifies these mediums as tool’s in their craft. Selected recent commissions/exhibitions include: Shanghai Biennale (2021) Athens Biennale (2021) Solo Show at Underground Flower Offsite (2020) Serpentine Galleries, London (2019) IMT Gallery, London (2019) Mimosa House, London (2018), ICA, London (2018-2020) Cell Project Space, London (2018) Gropius Bau, Berlin (2018) Yorkshire Sculpture Park (2016-17). Ayesha is represented by Harlesden High Street Gallery, London.

https://www.ayeshatanjones.com/

Desree is an award-winning spoken word artist, writer and facilitator based in London and Slough. Currently Artist in Residence for poetry collective EMPOWORD, Desree explores intersectionality, justice and social commentary. Producer for both Word Up and Word Of Mouth, finalist in 2018’s Hammer & Tongue national final and TEDx speaker, she has featured at events around the UK and internationally, including Glastonbury Festival 2019, Royal Albert Hall and Bowery Poetry New York. Burning Eye Publishers republished Desree’s first pamphlet, I Find My Strength In Simple Things, in May 2021.

Alex Dayo comes from Burkina Faso where his professional musical career started in the 1980’s, accompanying the National Ballet Kouledafourou on tour as well as playing for African Royalty and globally recognised dignitaries at private and public events and the Ensemble des Radios and Televisions of Burkina Faso, based in Bobo-Dioulasso. In 1985, he founded Wountey, a collective of musicians who created a new fusion of traditional and modern music called Plenguedey, and, for fifteen years, toured across Africa and Europe, spreading Burkina Faso’s cultural fusion to a wider audience. His musical collaborations include Ali Farka Toure, Femi Kuti and Salif Keita from Africa and traditional Master Griots from Burkina Faso/Mali/Guinea/Gambia. An accomplished arranger, Alex incorporates African traditional, Fusion, Jazz, Rock, Latin and Caribbean influences. Alex moved to London in 2007, where he set up a drumming school. A highlight of Alex’s career was being chosen to play at the Opening and Closing ceremonies at the London 2012 Olympics.

http://drummingschool.co.uk/zantogola

DESIGN & DEVELOPMENT

Studio Hyte is an award-winning design studio, working between graphic design, interaction, and emergent communication. Their work includes branding, print, website, installation, and exhibition design. Specializing in forward-thinking, multifaceted visual identities within the arts and education sector. Whether through commissioned or self-directed projects, they aim to create meaningful, accessible, and thought-provoking work.

Formed of a small group of individual practitioners, Studio Hyte is the middle ground where all of our interests and practices meet. Their collective practice and research cover a broad spectrum of topics including language, inclusion & accessibility, egalitarian politics & alternative protest, and technology & the human.

IG: @studiohyte

Recently I was approached to conceive and run an outreach project to accompany a solo show of work by Eduardo Kac at Furtherfield Gallery in North London’s Finsbury Park.

Among the works on show was one of Kac’s Lagoogleglyphs, large scale stylised representations of rabbits (something of a signature obsession for him) painted in some sort of sportsground emulsion directly onto a section of the park and allegedly of a scale which make it harvestable by the satellites Google rents for its various mapping activities.

Being completely frank, I have to say I entertained a degree of scepticism about Kac’s work—some of it falling within, in my view, one or both of two entertainment based metaphors—the ‘one-liner’ and the ‘theme park’—neither particularly positive elements of my critical lexicon.

Be that as it may, some of the work, particularly the less grandiose pieces (that delicate bunny flag flapping above the gallery!) were touched enough with real poetry to make me want to take up the challenge.

I say ‘challenge’ advisedly for I’m only ever interested in doing anything which in some sense challenges me and I also felt that my ambivalence about Kac would result in anything I ended up making containing a return element of ‘challenge’ or, perhaps more gently put, practical critique.

The word challenge also described the sense I had of wanting to counterpose collaboration, the collective, the everyday, to the artist with a capital ‘A’; of going some way to claiming art as a way of seeing and feeling and thinking together for All ( also with a capital ‘A’).

Reaching back in memory I pondered two remix/homage projects from the noughties which somehow straddled, in a pleasantly clunky fashion, practices both cutting edge digital (at least in their original moment) and time honoured too.

Apposite and practical stimuli for my 2018 purposes, they suggested elegant pathways to both honour previous work and to gently…um… stress-test it.

Both evinced rich humour, a warmth and a concomitant refusal to take themselves too seriously, qualities lacking in much contemporary art and both had a kind of performative klutziness I found entirely engaging.

Both were made in the first years of this millennium when digital and particularly online art was a wild west with a few fragile homesteads scattered here and there and not the orderly space it is today colonised almost entirely by the mainstream art world or commerce or both.

I recalled first a project by Nathaniel Stern where he hired South African billboard sign writers to paint physical representations of various, mostly art related, web pages.

The second was artist duo MTAA’s remix of Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance project, an endurance piece where Hsieh had forced himself to punch a timeclock on the hour, every hour for a whole year.

Reversing the premise MTAA’s Whid and River posted a database of video clips of themselves sleeping, eating, inhabiting the space and left it to the online viewer to watch these being digitally assembled (by Flash—remember that?) into a simulacrum of the original over the assumedly continuous period of a year.

Armed, fortified, prepared thus, I set to work—but I still needed a concrete plan and methodology.

Being a keen runner and the project taking place in a London Park in which I had run a 10k not long before (and now having endurance floating near the top of my mind) I felt some kind of park related physical activity would be an element and this would be a way of coming closer to those who loved the park but for whom the art gallery might not be their first association.

But still I lacked the concrete rabbit themed activity which would offer genuine practical, meaningful and autonomous artistic engagement and creation to participants.

I did not want to control what those participants would do but give them a clearly defined (clearly defined enough that all inputs from three separate days of activity could be brought together into a final unified work) and interesting task within which they would need to deploy creativity, focus and skill.

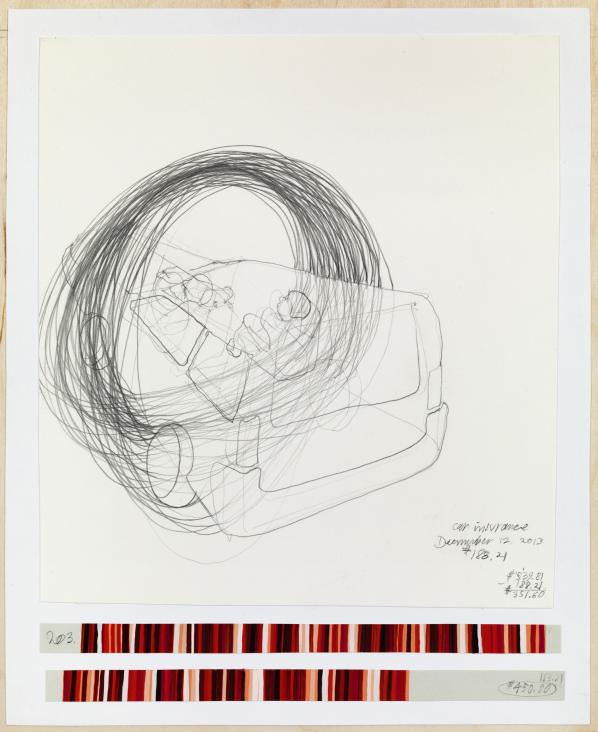

The fad for exercise related GPS devices had previously passed me by but one day whilst running with my daughter, who uses her phone and GPS enabled software to document her running in data and map form, I had a small epiphany—here there (might) be rabbits.

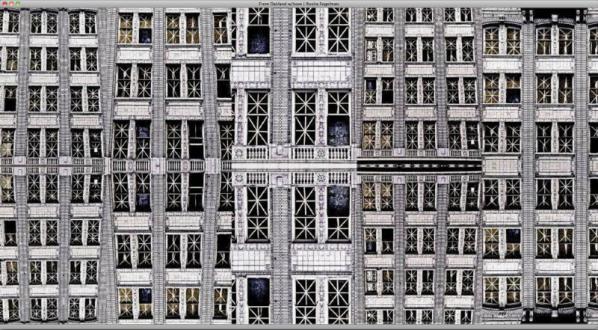

Rabbits, giant GPS rabbits, first planned and sketched by participating teams in marker pen over a satellite image of the park—ears, eyes, paws, body, fluffy tails emergent within its various paths and trails and features and obstructions.

And then, using these maps, we would carefully and attentively walk-out each monster rabbit trapping and freezing it as a succession of data, a series of co-ordinates in the memory of the GPS watch I would wear, finally to be reconstitututed as a continuous line drawing in turn fed back into a fresh satellite view of the park.

But that succession of co-ordinates, actuated by the actual movements of the human body (like a giant pencil lead or nib or brush) will resolve itself into something ancient—line, preconceived and then drawn out by human beings.

Being, together, both the very oldest form of mark making and something blink-of-an-eye recent too (well, as recent as the noughties efflorescence of so-called locative media which I shamelessly pillaged here.)

Inaccuracy in some measure a feature of both ancient and modern—the error margin of even GPS and GLONASS together, two sets of four satellites working in concert; the mix of will and skill and the fallibility and triumph too of flesh and bone and sinew which is part of what thrills and moves us in the arts.

This is what I had in mind.

Repeatedly outlining then co-performing an activity which I learned to summarise simply and precisely, almost automatically, one might have thought boredom or a dozy, parroted, routine might threaten.

And how anxious I was each time as to whether and in what way each new team would engage with—buy into—adopt as theirs, as ours—the task.

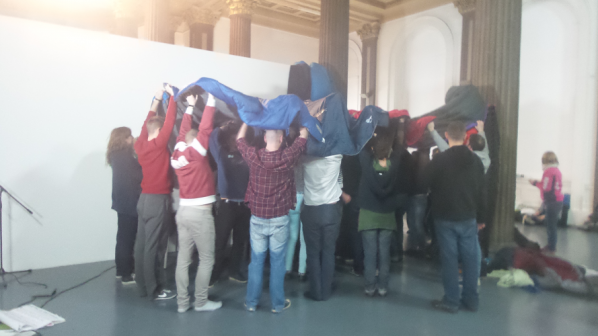

But how striking the variation both in the simple, basic act of depicting in continuous line each new rabbit-of-the-imagination and the forty minutes lively sociability surrounding that initial sketching and subsequent walking-out.

Balancing the competing claims of making something serious, something with some kind of weight, some satisfying end product, whilst making space for others’ fun and dreams and and will and whimsy is neither easy nor is it trivial.

In the end people seemed to have a good time, they seemed at ease, went at it with a will and—it seems to me—something rich and affecting emerged.

Thanks to all at Furtherfield and thanks—no, not thanks, but credit—to my fellow artists: Alessandra, Anna, Candy, Chris, Elliot, Evgenia, Franc, George, Grace, Henry, Jade, Lenon, Léonie, Lucian, Luka, Martin, Matthew, Maya, Negev, Niyah, Pryle, Rémi, Rosalie, Sara, Shiri, Stefan, Thea and Tyler.

This interview was originally printed in Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain published in partnership with Torque Editions in 2017.

Marc Garrett: One of many interesting and experimental things about the album Platform, released with Holly Herndon in 2015, is the decision to break away from the perspective of singular genius, and involve a variety of collaborators. This included artist Spencer Longo, Claire Tolan (of Tactical Tech), and Dutch design studio Metahaven. On the 4AD press release page it says that it ‘underscores the need for new fantasies and strategic collective action.’ Under the name of Holly Herndon, along with Holly, you all became a kind of cooperative, collective construction. What inspired you and Holly to explore what could be seen as a decentralized body, or assemblage of individuals as a collective? Or how would you describe your working identity and the importance of this move?

MD: To put it in pretty boring terms, it has become a core part of our mission to be pretty candid about what we do. Holly had been making albums and touring by herself, and then during the early experiments that later became Platform (Chorus and Home) we had begun working together, as we were occupying this tiny apartment in San Francisco, and I was working on this weird net concrete stuff in one room, and Holly was writing for voice in the other, and I think both of us picked up from the ambient sound that the two worked really well together! For the Chorus video we had seen the work of the Japanese artist Akihiko Taniguchi, and really enjoyed the collaborative process of putting that video together, and so then sought out Metahaven, who we’d been in touch with for some time out of aligned interests. Basically most art production at a certain high level is collaborative, and I think it’s just part of our idealistic view on the world that this be transparent and celebrated. Beyond that, when we were coming up with the vision for Platform it also felt very necessary as a political gesture to make a point of the project being aligned with certain political interests, and a politicized way of working and acknowledging others. Working this way has changed my life, and made everything more fun and exciting without diminishing the importance of any individual contributions. It makes for better results, I feel, better general feeling, and also creates these very tangible collaborative connections between fields. It’s also just an interesting experiment to run in music when it feels like so many sonic experiments have been done to death – I’m personally interested in how decentralized practices, collaboration and connectivity, can change the construction and dissemination of music, and ultimately it’s power to be a force in the world.

HH: It sometimes feels like our society is ‘every person for themselves’. We promote hyper individualism at the cost of the planet and social health, and the music industry largely parrots this mentality. We realized how problematic this is, and if we are going to be true to ourselves, then the practice should reflect that concern. It’s been a learning curve for me; learning to not control every single aspect (I tend to micromanage), to hear other opinions, to let go, and not feel threatened if someone else’s idea is better than my own. Releasing my debut album solo was an important step in building my confidence, however ultimately the work itself is the most important, and not the ego. Not to mention that we spend a lot of time on computers, which can be lonely, so working with other people helps us to unplug and see the world around us a little more.

MG: In a world that traditionally, economically and politically, supports the values of individuality above community, or peer to peer collaboration. How did the audience, the music industry, and others in the world (presuming they have) come to terms with this adventurous, creative intention?

HH: It was varied, but overwhelmingly positive. When we were doing press around the record, it was difficult to get some journalists to write about the other artists and thinkers that I was collaborating with, or even just referencing. Those that understood the gesture really embraced the idea, and that successfully provided a platform to highlight everyone’s work.

There are a few industry complications; for example, the project is released under my birth name, so in some ways I am still at the centre of the orbit, which is a problematic professional necessity, but also helps somehow. We used the idea of the Trojan Horse a lot, as in a way my easily understood singular presence served as a gateway into this whole other universe of people. It’s a balancing act, as in various different scenarios you feel different expectations as to what the industry wants; on a pop level they want a simple narrative of my face, and tend to focus on often mundane characteristics such as my gender and education. On other levels you see that the experiment has opened up a different narrative potential, where people’s interest in the record and it’s cast forks off into the direction of their choosing.

It’s really noticeable live, where the audiences have been really supportive. After the shows you experience all kinds of people who come along, hanging out with different people who were on stage – Mat has his own audience somehow, and the same with Colin Self, who often tours with us. As a result of opening up the process and allowing the full breadth of interests and approaches to shine through a little more than is standard, at different shows we have people come up to talk to us about the music, or nerd out about cryptocurrencies and ICO’s, or Chelsea Manning. It feels meaningful, and gratifying for that. We always address the location of the show, whether through the visual or sound, and try to always be alert and responsive. It’s a special privilege to share that time with people, and I think that the concept comes across quite effectively in a live situation as each individual serves a very different purpose in constructing the collective experience.

MD: I think that Platform was received really well. Holly opening up her practice didn’t diminish her signature on the artworks, and I think that it has really won a lot of people over. I think you can feel at our shows that we have a greater principle to what we do, and I think it has maybe made a lot of space for people to conceive of their own experiments and maybe not be concerned at how being ambitious on a conceptual level will affect the ability for the art to travel in the world. Naturally there is also a throttling effect within aspects of the creative industry, where maybe they didn’t want to deal with the bigger ideas around the record, however I feel that the music is strong enough to kind of live in those circles without knowing the story behind it. Overall I think people were refreshed and encouraged by the idea, and transparency of the whole thing. For us now it is a way of being. In my mind, there is more room for individuality to shine when you can guarantee that someone’s work and ideas will be respected and celebrated. The canon of artistic history has omitted so many people’s ideas and contributions for the purpose of having a simpler market narrative, and yet we live in a time when people can and want to dig deeper, and perhaps have a greater capacity for complexity of information – so we want to try and harness that for something positive. Particularly given our interests in subcultural music history, software, crypto etc. there is really no other option but to put the community first. Without community literally none of this exists. Zero. All of our talents and ideas have been incubated in community environments, so channelling that legacy is important.

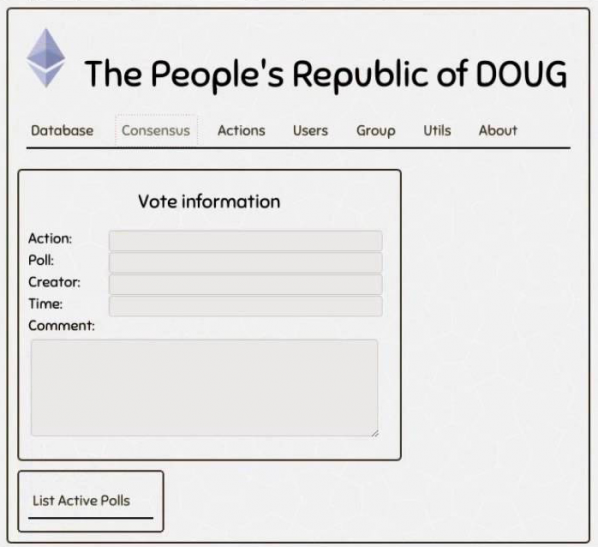

MG: On Platform you released the track called DAO. I am always interested in shifts between the use of technologies as metaphor and as tools that change practice. So, what was interesting to you about Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs)?

MD: I’ll let Holly talk more about where DAO came from, with the telematic performance work she was doing at Stanford. Regarding the blockchain, I’ve been developing my own decentralized publishing framework for the past few years, that shares a lot of the same principles as the Ethereum logic, and I’m looking to have it interact with the blockchain in its next iteration. A lot of the spirit behind the crypto community is so synonymous with the models of collectivity we have already been exploring in our work that it’s the logical next step. I’m particularly interested in what this architectural/infrastructural new capacity can mean for the medium of music itself. With Saga you have this whole other performative dimension added to media with the ability to version work, fork it, and have it perform in real time to it’s surroundings online, which I think is a whole other proposition for the medium very much worth exploring. It’s also fascinating regarding the question of attribution and collaboration, as we have grown to understand that the web as it stands currently is very much designed to privilege those who appropriate and curate others creative work and ideas for free – mirroring greater society, it is a winner takes all environment. I want systems of virtuous attribution that do not consolidate the DRM era of copyright takedowns, but instead build markets and new interactions around collaboration, augmentation and live interaction. There is so much more that could be done, and a lot of the blockchain tech emerging offers clues as to how we can get there quickly. There are also a lot of old ideas masquerading as something shiny and new, so you kind of have to read the small print to distinguish what is a genuinely new proposition, but it is our job as members of marginal communities to educate ourselves and anticipate the best options.

HH: DAO came out of a piece that I wrote called Crossing the Interface, with a libretto by Reza Negarestani. The piece was my first venture into telematic performance, where a soprano (Amanda DeBoer) was in another geographic location, but the audience could hear her physical body moving throughout the space using ambisonics. I wanted her to be hyper present, and physically super human, moving in ways impossible to a human body, to be able to be in multiple places in the room at once, as eventually her voice and her body separate, stalking the room. I was trying to find a way to make something so clearly highly mediated, feel extremely personal and embodied at the same time, which seems appropriate for the DAO concept as it exists in the world – this simultaneously complex and distributed network that is also hyper intimate and moves with collective intent.

The vocal work that Amanda delivered while workshopping that performance was really great, so I used some of those outtakes for the vocal work in DAO. With the instrumental I was simply just trying to capture an atmosphere, a heavy energy with lots of wide stereo movement. It’s also really fun to play live with Colin, because he sings the soprano line with live processing, which creates a nice contrast of heavy electronics with extremely expressive alien vocals, taking the entire gender spectrum and contorting it into a circle.

MG: Do you have any plans to formalize any part of your creative collaboration to work on the blockchain?

MD: Holly and I are starting a studio after we finish this next album to more formally develop work and devices that exist in this new frontier, as it has been so instrumental in our discussions for the past few years. I describe it as a frontier deliberately, as if we are to task ourselves with actually experimenting with our work then it feels almost like a duty to get our hands dirty in these areas. We have already started work on two new projects in this domain, but it’s hard to tell when they will be ready to show to people, and what shape they will eventually take.

MG: OK. Last question, in light of the current suppression of the spirit of humanity by despots, and the rich buying up democracy for their own ends, what part do you see artists playing in the world of blockchain, to disrupt the regurgitation of an already bankrupt system?

MD: IMHO, there are two dimensions to this. First, I encourage artists to become familiar with the language and potential of blockchain technology, as there are a lot of opportunities to attempt to re-engineer how we experience, transact and grow community in the arts outside of centralized traditional channels. Real money is being made, and there is a lot of good will amongst the crypto community who invest faith that better systems can and will be constructed using these logics.

I also encourage artists to develop some fluency around the blockchain ecosystem, for exactly the reason that there needs to be wary and critical voices guarding the community from the business-as-usual corporate crowd, who are increasingly flexing their muscles and influencing the course of its development and maturity. By getting involved early, and being vocal, there is an opportunity to intercept plans for how this next internet runs, and who ultimately it will benefit.

The best case scenario is that we can develop our own systems along the blockchain to change music and the arts for the better. Alternately, we need critical voices active within these conversations to avert the worst case scenario of power consolidating itself even further outside of the greater public awareness.

I should say that the third wild card possibility is that blockchain technology is inherently flawed and infeasible once it has been properly stress tested at scale. Irrespective, if your mandate is to be experimenting, and abreast of where things may be going, there are fewer areas of interest more dynamic and potentially transformative. It’s a lot of fun to think about.

Most households have an unsolved Rubix Cube but you can easily solve it learning a few algorithms.

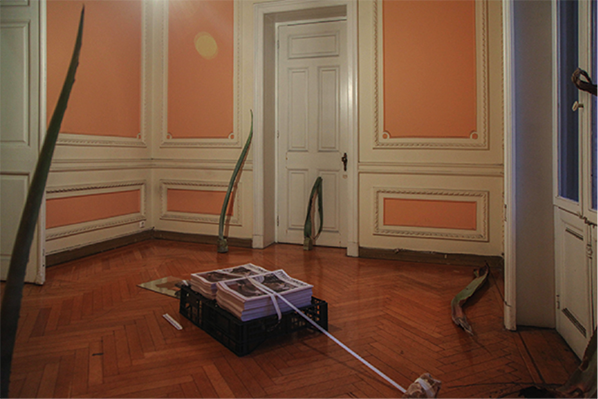

Walking off the Akadimias district and onto the steps leading up towards the entrance of building number 23, I am greeted by a large hall with high red ceilings. The hall is covered with lavish white and black dot marble, and there is a large staircase acting as a guide to the top floors of the manor-like building. This was the home for the Diplomatic Centre of the Third Reich, designed in 1923 by Vassillis Tsagris, and used until 2011 by the Foreign Press Correspondent Union after the Second World War. Since then it has stood derelict and dusty, but for one week, in parallel to the opening of documenta 14, it played temporary host to the artist-in-residence programme of Palais de Tokyo, alongside with Foundation Fluxum/Flux Laboratory, bearing the name Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Six visual artists in residence at Pavillon Neuflize OBC and eight contemporary Greek choreographers envision and fabricate a hybrid space whereby an experimental notion of a community is executed as a situation rather than as a subject. The visual artists and performers involved congregated together in Athens and on site for a two-week workshop in March in order to produce the works. The title, Prec(ar)ious Collectives, is a linguistic amalgamation of the adjectives ‘precarious’ and ‘precious’, implying the state of the collective that performs together.

The opening façade echoes with the humming and reverberated sound of Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos‘ Dusk and Dawn Look Just The Same (Riot Tourism), guiding us towards its installation room. The video installation stands above a mountain of blue powder in a room sectioned off with construction tape. The short sequence of about a minute and a half displays a group of hooded figures, dressed identically. As the soundtrack’s volume begins to escalate, the group progresses from walking to running on the uncannily void and ghostly streets of Athens. A city always bustling with noise is now at its most quiet and pubescent state of the day – dawn. The hooded figures run together and – even though it is in a disordered manner – command your attention and pensiveness until they all reach Omonia Square. The work demonstrates a resistance to a status quo which may be aligned with the political engagement within the city. This is not, however, done in an expected reactionary manner, but instead in a way that promotes uprising through the creation of a meditative state. One cannot help but watch Lemos’ work a couple of times more before leaving it behind and only then noticing the thundering beneath their feet.

This historic building has a basement and is the temporary home of Taloi Havini‘s performative work. The large-scale installation occupying four rooms consists of PVC vinyls, seemingly discarded or hung from the low ceiling. These PVC vinyls are lit by dispersed and differently coloured strings of light, some are red, others are purple and others are cream. The performance is underway and its performers dress themselves with the PVC vinyl and the lights and jolt their bodies vigorously to the rhythm of the thundering – sometimes in sync, sometimes not. The dark basement is transformed into a cavern of rhythmic delight alluding to a ritual where its power lies in the gathering of people.

As one inspects the garments of Wataru Tominaga and those who wear them, this synthesis of the PVC, the space and the performers as a gathering appears to be a motif. Tominaga created the garments during a preliminary workshop, with great care and appreciation of how he and others were to utilise them during Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Originally presented on mannequins before being worn and performed, the garments boast vivid colours and patterns, some of them containing animalistic features such as feathers or fur. Those who wear Tominaga’s work perform in such a way as to invent a new form of communication between themselves and their observers. They move and conjoin like animals, sometimes hiding underneath the fabric and at times evoking the traditional Japanese ‘snake dance’. The performance, being in a transitional space between the ground floor and the first floor, naturally spreads itself upstairs whereby the performers not only continue to wear the garments in obscure ways, but additionally interact with Yu Ji‘s agave plants and other objects.

Yu Ji‘s work, Lycabettus Tongue, Oliv Oliv and This is Good For You! Are formed by the use of displaced agave plants, half-fragmented found mirrors and lights. The agave plants interlock with various architectural patterns of the building such as stair banisters, whilst the mirrors and round-ball lights are positioned in ways offering various points of view for observation and appreciation of space. The work revitalizes the architecture of the building denoting its historical vitality and the synergy of the encompassing works into a haunting existence rather than an abandoned one. Here, haunting is used not for means of negative connotations but instead as a form of aloof yet introspective sensation, exasperated further with Lola Gonzàlez‘s video installation in the next room.

Lola Gonzàlez‘s Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw begins with its protagonists split into groups and observing the city of Athens from various points at the top of the hills. The groups begins to move, run and hop together towards a direction down the hill, whilst a chorus of droning voices begin to chant and harmonise. As the groups get closer and closer to the city, Gonzalez transforms the image into a complete inversion, like one you may find in negative photography. The chanting becomes louder as the three groups get closer and closer to their meeting point within the city – the exact space where the video is being showed. They are finally shown entering the building and making their way up the stairs to the room where they vocalize in unison until they fade away from our view. Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw alludes to an atmosphere in which the power of gathering together evokes a community whose intention is situated between an uncertain balance of peril and strength. It is the same kind of uncertainty that one finds when exploring the top floor of the building only to discover Thomas Teurlai‘s room of machines and looped functions.

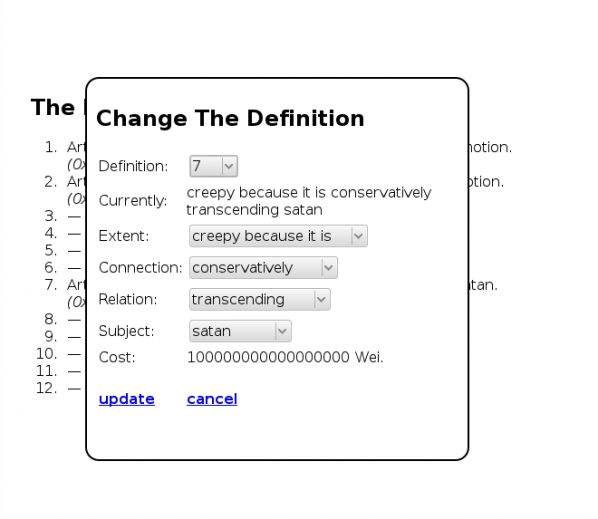

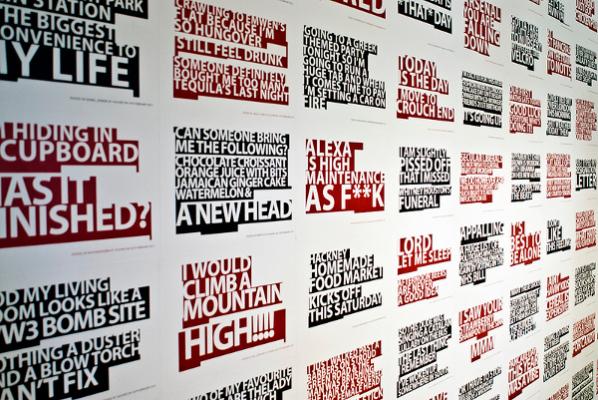

On the top floor, there are still the remnants of neglect, rooms empty of anything but the garbage that piled up over the building’s six years of desertion. Thomas Teurlai‘s Score for bodies and machines consists of a room installation of two printers used by the performers to scan different parts of their bodies. These scans are then plastered on the wall whilst the fluorescent lights constantly trickle on and off. The two performers are attempting to archive as much of the movement involved in their choreography as possible. The looped function of copying and the crackle of its repetitive working-noises do not clash with the choreography but instead drive its energy.

Indeed, it may be the encounter between the building, the communal working spirit of the performers and the result of this effort that defines this rejuvenating energy as a fruitful rebirth of the building’s utility.

To find out more, read Chloe Stavrou’s recent interview with Fabien Danesi of Prec(ar)ious Collectives.

CS: Tell us a little bit about how the collaboration between Palais de Tokyo’s residency Pavilion Neuflize OBC and Fluxum/Flux Laboratory came about. Did this directly contribute to the hybrid of visual/dance performance art or was it the artists’ call?

FD: During two years, the Pavillon Neuflize OBC has worked with the National Opera of Paris for projects at the crossroads between contemporary art and choreography. We wanted to develop this perspective which is a kind of tradition in the history of the Pavilion (created in 2001), if we remember that our institution has a long interest for transdisciplinarity. So the hybridization between visual art and performance wasn’t the artists’ call. On the contrary, we asked them to step aside for collaborating with choreographers. It was really experimental for them.

CS: Neither Palais de Tokyo or Fluxum/Flux Laboratory are situated in Greece. What was the reason for its inception to take place in Athens? Was it because of the traffic Athens would see due to documenta 14 or was it a suggestion by Andonis Foniadakis, the choreographic director?

FD: Since its creation, Fluxum/Flux Laboratory has developed many dance projects in Greece. And it’s due to its founder, Cynthia Odier, that Ange Leccia and myself met Andonis Foniadakis. We started the dialog with Andonis right at the moment of his nomination as the Ballet Director of the Greek National Opera, o Athens appeared quickly as the perfect place for our collaboration. We decided just afterwards to take advantage of the presence of documenta 14 in the city.

CS: The result is quite impressive – specifically since, and correct me if I’m wrong – the work produced was created in only two weeks in March. How did you find the process of working and creating collaboratively in addition to being in an unfamiliar city?

FD: The residents came to Athens for the first time in November 2016. During the first week, we had met the choreographers and dancers but also people who are engaged in the artistic life of the city. We tried to understand and use the pulse of this specific urban energy. We visited some sites for the exhibition and began to question the relevance of our own presence here. The conversations with the choreographers permitted us to create a strong link with Athens and not feel like tourists. We came back for a three-week workshop in March, just before the opening of our show. Between these two stays, we discussed a lot and had decided to start from our situation with the desire to move away from an artificial subject. The notion of the collective seemed a good way of taking charge of what we tried to do – especially because the Pavilion tries every year to create a specific group that gives a specific form to its structure.

CS: Prec(ar)ious Collectives feels like it could be quite nomadic as it is in an unfamiliar environment; however nomadic does not mean it feels odd or out of place – in fact it felt quite the opposite. As a curator, how did you approach Athens and stay conscious of the context(s) surrounding it?

FD: The fact that we didn’t exhibit in a white cube or an artistic space helped us. When we decided to occupy this abandoned building on Akadimias Street, I was sure that we would be related strongly to the city and its history. The context wasn’t outside of the walls – it was here, with us. Of course, we were all conscious that we needed to stay in relation to what was happening in the city. That’s why nobody arrived with their work completed and done. The materials and the main elements of the creations were an artistic answer to this particular context.

CS: I am very curious about the building. I understand it used to be the Diplomatic Centre for the Third Reich during the Second World War. How did you become aware of its existence, and did your decision to curate Prec(ar)ious Collectives have anything to do with the building’s history? If not, what was the reason for selecting this building?

FD: In January 2017, the director of the Pavilion Ange Leccia was in Athens to present some of his work. He visited the exhibition organized by Locus Athens in this space and it impressed him quite a bit. We wanted to work in an abandoned site for underlining the economical and cultural situation in Greece. And Akadimias Street 23 seemed perfect. We didn’t choose it for its history, even if these multiple layers added some density to our proposal. For sure, the different atmospheres of the rooms immediately gave us the possibility to create dialogs between the works while preserving the integrity of each. So, it was a question of ambience in the sense of the architectural conditions aiding the experience of the audience.

CS: I found that a continuous theme within the exhibition was not only the creation of a utopic community, but also an ambience that generates a state of limbo – of transition. Was this a reference to the state of Athens or to the state of artistic production or work?

FD: The notion of limbo is stimulating. And it insists on our «spectral approach». It means that we have tried to give life to this abandoned building. And some installations can be described as floating. In Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos and Lola Gonzalez’s videos, for example, there is the idea of apparition. And even with Taloi Havini’s huge ephemeral camp, we can feel a sort of «in-between» space, archaic and futurist, protective and dangerous. Maybe it was a re-transcription of our impressions about Athens, so appealing and full of energy, but at the same time, so undermined by the political situation.

CS: As a final note, what is the next step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives after its brief residency in Athens? Are there any plans to simulate the experience, albeit differently, again in another context or place?

FD: There won’t be another step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives as a group exhibition. It was really the result of a one-month workshop. But it happens for the best that some encounters initiated in the Pavilion can be developed after the time of the residency.

CS: And any future projects that you will be a part of?

FD: On my side, I will develop a curatorial project next year in Los Angeles in the frame of FLAX residency. Titled The Dialectic of the Stars, I will organize several evenings in different institutions which will permit artists? to drift in the city from one site to another for catching some contradictory parts of the L.A. atmosphere. The idea is to mix French artists and Los Angeles-based artists and to trace a political and poetical constellation.

To find out more read Chloe Stavrou’s recent review: Community Situation: Prec(ar)ious Collectives and documenta 14

Compiler is an experimental platform organised by curator Alisa Blakeney, artist-curator Tanya Boyarkina, artist Oscar Cass-Darweish and choreographer Eleanor Chownsmith, all currently students of MA Digital Cultures, Goldsmiths. The platform is being built in order to “support collaborative, process-driven projects which connect artists and local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange”.

The organisers of Compiler describe it as a kind of ongoing prototype, a structure constantly negotiating the openness to maintain links to varied practices with the coherence of framing, containing, and describing some of the complicated products of digital-analogue interactions. Their focus is looking at what ‘digital culture’ means and having a productive conversation about it.

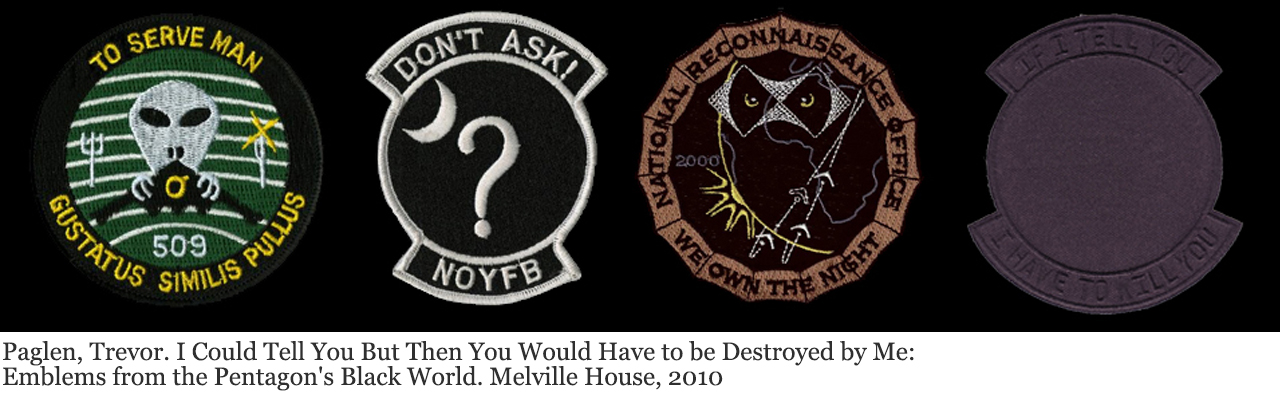

From 6-8 April, the first Compiler, Play Safe took place downstairs at OOTB in New Cross. The exhibition examined practices of surveillance inherent in “states, corporations, technological spaces and the idioms of digital art”. It questioned whether an increasing intensity of surveillance is linked to control, extraction and politics, or can be understood as a pleasurable phenomenon. People were invited to “Dance a website, see through the eyes of a computer, and have our cryptobartender mix you a cocktail to cure your NSA woes”. The work on show, made by students from MA Computational Arts and MA Digital Cultures (both Goldsmiths), included Eleanor Chownsmith’s software and performance which turned website HTML into dance routines, Michela Carmazzi’s photographic project documenting the reactions of Julian Assange and his supporters following the United Nations’ ruling about his case, and Saskia Freeke’s machine which repeatedly and intentionally failed to create a ticker-tape parade using sensors and fans.

An exhibition on the theme of surveillance creates a strange grey area for itself when shown in a building with nine screens of CCTV footage. Oscar Cass-Darweish’s project made a fairly direct link to the CCTV cameras which emphasised this greyness. The project produced a rendering of the exhibition space by using a function usually found in motion detection processes. This function calculates the difference in pixel colour values between frames at a set interval and averages them, creating a visual output of how machines calculate difference over time.

Another work which made links with the room upstairs was Fabio Natali’s Cryptobar, where following an interview with the ‘bartender’ about your data privacy needs you were recommended a cocktail of data-encryption software. Upstairs you could buy, and drink, a cocktail with the same name (the Cryptobar was part of the V&A Friday Late on Pocket Privacy on 28 April).

So far, Compiler has made a variety of spaces for conversation about digital culture through both its artworks and its organisation. Each artwork has a different ‘footprint’ of interactions, linking websites to rooms, success to failure, data privacy to financial transaction via consultation, and making interesting connections between CCTV and code, dance notation and HTML, activism and commerce.

An interesting way to read the Compiler platform is as a series of combinations of human-readable codes and machine-readable codes. The platform ‘compiles’ a different combination each time, and each time the output is different. Through this, the interaction of analogue and digital processes is demystified and muddled, in a distinct way. The platform is in its early days, but it seems likely that new connections and new grey areas will appear over the next few months, as Compiler has its second exhibition (again at OOTB) in May, takes part in the CCS conference at Goldsmiths in June and heads in other directions thereafter.

The exhibition offered plenty to play with, while posing complicated problems in relation to openness and experimentation. When I spoke to Eleanor, Tanya and Alisa about Compiler and its aim to engage local communities in networks of knowledge-exchange , we talked about how it’s an impossible and strange aspiration to have a ‘neutral’ venue. While a cocktail can be delicious and engaging, it’s also expensive. While a cafe is, arguably, a less exclusive space than a gallery, OOTB itself is a cafe which targets a specific audience. Drink prices, decor and a host of other factors mean OOTB, like all spaces, is politicised in a particular way. Their venue choices so far will influence, in subtle and overt ways, their future attempts to engage diverse local communities. The organisers of Compiler acknowledge this; their response is that rather than trying to make an artificial neutrality they are keen to move as the platform develops to new spaces and new and different contexts.

A change of context, message, communication style is not easy; nor does it fit with to an easily recognisable politics or aesthetics. Moving into and out of contexts is something to be done carefully and thoughtfully. It seems to me that the Compiler team will have their work cut out, but if they can direct that work in such a way that the platform is able to communicate in multiple ways at once, ‘networks of knowledge-exchange’ could develop between, and in response to, the markers set by the organisers. The question is, how will they develop?

As curator of the exhibition Monsters of the machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century, I thought it necessary to interview the artists in the exhibition, while it is shown in the magnificent gallery space at Laboral, in Spain, until August 31st 2017. I wanted to get more of an idea of how they see their work in the show relates to the core themes. Mary Shelley’s book Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, has been interpreted in numerous ways since was written in 1816, and then published anonymously in London in 1818.

Eugenio Tisselli is a Mexican artist and programmer. He is a PhD candidate at Z-Node, the Zurich Node of the Planetary Collegium. Previously, he worked as an associate researcher at the Sony Computer Science Lab in Paris and was also a teacher and co-director of the Masters in Digital Arts program at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. In his role as director of the ojoVoz project, he has carried out extended workshops with small-scale farming communities in different parts of the world. The ojoVoz project may be accessed at http://ojovoz.net. His personal projects may be accessed at http://motorhueso.net

Marc Garrett: Can you explain how and why the Sauti ya wakulima, “The voice of the farmers” project came about?

Eugenio Tisselli: In 2010, I came to realize that the way we feed ourselves is actually one of the main drivers of the accelerated destruction of societies and ecosystems that is currently underway. I felt like I had been living in La-La-Land before the veil was ripped off. My life changed radically. At that time, I was collaborating in the megafone.net project which had worked since 2004 with several groups of people at risk of social exclusion in different parts of the world. By offering an unfiltered communications platform, consisting of mobile and web applications, the megafone project tried to help these groups to make their voices widely heard. But, in 2011, I left the project with the purpose of offering its tools and methodologies to farming communities who wished to seek recognition and explore different forms of communication.

The first opportunity took shape in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, where a group of farmers expressed their interest in trying out these tools. I came in contact with this group through a scientific project that studied the direct and indirect effects of climate change on agriculture. The original goal of ‘Sauti ya wakulima’ was that the farmers would use smartphones and a web application to create a collaborative, audiovisual knowledge base of weather-related events, such as droughts, floods or crop diseases. However, the farmers eventually discovered that they could reshape this goal, and started to use the phones to interview other farmers with the purpose of creating a network of mutual exchange of knowledge about agricultural practices and techniques.

Episodes of fruitful learning have happened since then: one farmer learned the proper way to grow maize thanks to a picture taken by one of his colleagues. Another one learned a clever way to build chicken sheds during a trip to an agricultural fair. He took pictures of the sheds and when he came back to his community, he formed a cooperative for chicken production together with three of his colleagues. I could go on, but the project is still active after six years and that is probably the best thing that can be said of ‘Sauti ya wakulima’. It is alive because farmers find it useful, and it’s inspiring to learn from them that the mutual exchange of knowledge can become a key to a more resilient and interesting life. To me, the agricultures depicted in the photos posted by the Tanzanian farmers are not echoes of ‘the past’, but pathways to the future.

MG: What particular themes in the exhibition do you feel relate to the “The voice of the farmers” installation?

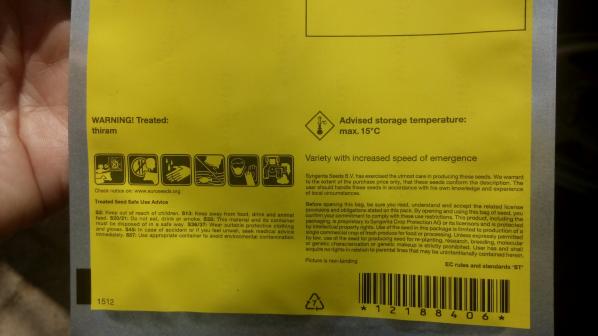

ET: I imagine ‘The monster in the machine’ not as a horrible, threatening ghoul, but as a weird and tricky creature made of language. The ‘body’ of this creature is made up of what we would call ‘principles’, ‘values’ and even ‘ideologies’. And it silently lurks inside the technological artifacts we use every day. The smartphone, for instance, epitomizes the ideal 21st century citizen: a self-sufficient, competitive and efficient individual. And, indeed, the monster that lives inside our smartphones is made of those values: its presence is inscribed in the device’s circuits and from there it casts its spell. What I mean is that technologies are not neutral. They are not empty: they are haunted by whispering ghosts.

If you look at technologies used in agriculture, you will also find a multitude of monsters that softly dictate from the insides of things. Perhaps not by coincidence, genetically modified (GM) seeds speak the same things as mobile phones, only with different words. They tell farmers: “stop sharing seeds with your community, it’s a waste. Become an entrepreneur, there are shitloads of money to be made! Buy me! I’ll make you rich!” The sad thing is that these words are a trap: farmers ultimately become entangled in monetized loops that are beyond their control. Desperation sets in and, in absurdly horrible cases, such as GM cotton farmers in India, suicide becomes the only exit. But there are, indeed, other exits.

It is possible to rewrite the values and ideologies inscribed in technologies, in order to make them speak words that will do less harm. This is one of the key components of Sauti ya wakulima. From the very beginning of the project, the farmers agreed to redefine the smartphones as communal tools for collaborative documentation. They still share them and, when it is someone’s turn to use one, that person knows that she will not be taking pictures and recording sounds with a personal device, but with one that belongs to the group. These dynamics of sharing can create or strengthen reciprocal bonds. Renalda Msaki, a farmer who participates in Sauti ya wakulima, once said that the project had brought the group closer together. When I reflect upon her words, I can see how the monster in the machine can be transformed into a gentler creature that, nevertheless, remains weird and tricky.

MG: What role do you think the artist has when dealing with questions such as Monsters of the Machine exhibition?

ET: I think the artist can take up an incredibly vast range of roles when dealing with machines. But, whatever one does, one shouldn’t be naive about technology. Happily, the times when media artists created huge and complex pieces filled with little technological wonders just because it was exciting to celebrate their ‘magic’ is (almost) over. I used to say that (most) media art was the smiling face of techno-capitalism. Now I would add that, while technology was generally understood as a mediator between us and the world, it has now become a vector that uses humans to create its own mediations with the world. The roles have shifted, and things have taken a perverse turn. There’s a growing chorus of techno-objects that insistently asks us, humans, to drill the Arctic, build pipelines, burn coal, destroy forests and dig up more minerals. And we obey: we must feed the monster. Artists who approach technologies as materials to play with need to be aware of these power relations. We must acknowledge that technologies of all sorts have become overpowering actors that like to command.

Tisselli warns us that we need to be more aware of our responsibilties when implementing technologies into the environment. An important factor of the exhibition was to bring about a vision where the art was not just one type of art. This means different engagements in how we see and work with technology, are reflected as part of its context. Also, technology is not only a human skill, ’21st century scientific studies indicate that other primates and certain dolphin communities have developed simple tools and passed their knowledge to other generations.'[2]

As I write this conclusion, ‘Trump is poised to sign an executive order that will dramatically reduce the role that climate change has in governmental decision-making. The order could impact everything from energy policy to appliance standards.'[3] We live in a time where US policies are written via Twitter, and the rich are typically risking ours and the world’s future for their own ends. Tisselli and the farmers, remind us that, we need to be connecting with the land once more. We need to reclaim the soil before it is lost forever.

Mary Shelley’s distrust of the patriarch in the form of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, is as relevant now as it was 200 years ago. ‘Her portrayal of Dr. Frankenstein as an egocentric obsessive who will stop at nothing until he completes his mission in bringing his creature to life; represents man’s blind quest in pushing on until the precarious end, at whatever cost.'[4] Tisselli echoes this with his own critique towards artists working in technology. If we are to rethink what innovation can be now, what would that look like if we were to update it in a way that included indigenous voices, other levels of equality, and practices beyond what now seems like tired, machismo, and over obsessive, tech-enchantment?

The ‘Monsters of the machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century’ exhibition is on at at Laboral, in Spain until August 31st 2017. http://www.laboralcentrodearte.org/en/exposiciones/monsters-of-the-machine

Those involved in the Sauti ya wakulima / The voice of the farmers project.

The farmers: Abdallah Jumanne, Mwinyimvua Mohamedi, Fatuma Ngomero, Rehema Maganga, Haeshi Shabani, Renada Msaki, Hamisi Rajabu, Ali Isha Salum, Imani Mlooka, Sina

Rafael.

Group coordinator / extension officer: Mr. Hamza S. Suleyman

Scientific advisors: Dr. Angelika Hilbeck (ETHZ), Dr. Flora Ismail (UDSM)

Programming: Eugenio Tisselli, Lluís Gómez

Translation: Cecilia Leweri

Graphic design: Joana Moll, Eugenio Tisselli

Project by: Eugenio Tisselli, Angelika Hilbeck, Juanita Schläpfer-Miller

Sponsored by The North-South Center, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology – Zürich

With the support of The Department of Botany, University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM)

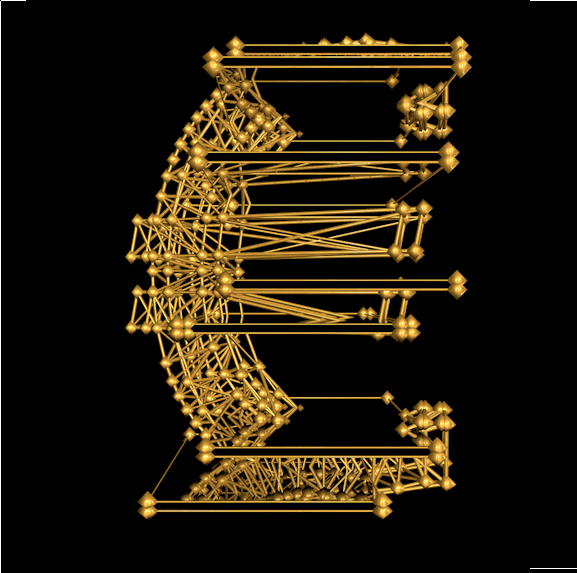

Plantoid (2015) by Okhaos is a self-creating, self-propagating artwork system that uses blockchain technology to gather and manage the resources it needs to become real and to participate in the artworld. Structured as a Decentralised Autonomous Organization (DAO), once it is set in motion the code of the Plantoid system combines the functions of artwork, artist and art dealer in a single piece of software.

As its name implies, the physical Plantoid artworks are cyborg-looking welded sculptures of flowering plants. Flowers are a popular icon of naturalised aesthetics in art and culture. Their aesthetic and art historical appeal makes them an effective subject for subversion. Radicalized flowers wander through recent art like triffids through the English countryside. Helen Chadwick’s “Piss Flowers” (1991-2) are a proto-xenofeminist riposte to idealisation of nature and the body. Mary Anne Francis’s “The Blooming Commons” (2005) combines the ideas of organic and creative fecundity to help artist and audience consider how making art open source affects its aura. Plantoid can easily be cast in this tradition.

The physical form of Plantoid is determined by its blockchain presence, which represents an advance on the state of the art. The Bitcoin blockchain is a database that represents control of resources. Most simply these resources are amounts of Bitcoin but we can encode information representing other resources – and the right to control them – into the blockchain as well. Current general purpose Bitcoin blockchain-based systems such as Counterparty can easily represent tokens for games, for reward and voucher schemes, or for stocks and shares. Placing these on the blockchain does not magically improve them over existing means of issuing them but it does reduce their barrier to entry and make securing and maintaining them easier. It also defamiliarises them by placing them in a new context and makes them accessible and thereby inspirational to new audiences. Melanie Swan turns this idea up to 11 in her excellent survey of the state of the art and its future potential “Blockchain“, describing the application of the idea of blockchains ultimately to the global economy and even the human mind.

Beyond tokens, the blockchain can be a cheap and effective database of existing property and rights, including recording Free Culture licensing. It is simple to create such a system, I made the first one for artworks based on Ethereum myself. It cannot be an effective means of policing DRM (as DRM is inherently broken) and must not be treated as a means of rolling back the limits of and exceptions to the existing property and copyright regimes or of creating new entitlements ex nihilo. This would turn a technology with great (if contentious) potential for liberation into a tool of exploitation. Making a GIF of Apple’s new emoticons and selling the blockchain title to it for $250 reflects existing social pathologies rather than new technological or artistic affordances.

The technobiophilic machine-nature-form hybrid nature of Plantoid is described by Okhaos in terms that cast cryptocurrency as metabolic and reproductive resources. To quote the project page:

Perhaps the initial Plantoid will need $1000 to fully turn into a blossom. Whenever that particular threshold for the Plantoid is reached, the reproduction process starts: the Plantoid only needs to identify a new person or group of persons (ideally, a group of artists) to create a new version of itself. Given the right conditions, the Plantoid is able to manufacture herself, by executing a smart contract that lives on the blockchain, and has the ability to commission welders, companies, and other beings to build and assemble a similar being.

It’s here that we see how Plantoid represents an advance on existing systems. The parameters of each physical Plantoid are encoded on the Ethereum (rather than the Bitcoin) blockchain as smart contracts, representing the economic and manufacturing logic and the aesthetics of its production as a kind of genome. Plantoid is an active artistic production agent rather than a passive registry of existing art.

The defamiliarising effect of the blockchain allows us to unbundle the collections of rights and responsibilities that make up roles within the mainstream artworld. Paying for the creation of art, its storage and restoration, transport and exhibition. Inspiring, designing, manufacturing, promoting, experiencing, critiquing and art. The artist, the gallerist, the critic, the installer, the attendant. A new territory like the blockchain allows us to shake things up rather than to try to double down on existing relations and distribution of wealth in order to extract new rents.

Plantoid opens up the roles of artistic production in precisely this way. It uses the structure of a DAO to incentivise the funding, governance, production, exhibition and reception of Plantoids in a virtuous circle (a positive feedback loop of production). None of this confers ownership or property rights over the physical Plantoid artworks on individual human beings. Their relationships are closer to those of patronage, crowdfunding, or tipping but unbundled further. There are technological precedents for this such as the way Aaron Koblin’s “The Sheep Market” (2008) commissions drawings from clickworkers, Caleb Larsen’s “A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter” (2009) manages its own sale, the way Bitnik’s “Random Darknet Shopper” (2014) orders goods for delivery to the gallery, or Imogen Heap’s release of the single “Tiny Human” (2015) using Ethereum smart contracts

From the project page again:

Plantoids are part of an ecosystem of relationships that is powered by two driving forces: aesthetic beauty and automated governance. Plantoids subtly motivate these interactions, partly through their form and physical beauty, but also by empowering people to participate in their governance. Participants (that is, active members of the DAO) are able to decide on such things as where the Plantoids may be exhibited, whom they might visit, and exactly how they are to be reproduced.

When it receives funds by the audience, the Plantoid evolves and turns into a more beautiful flower, by e.g. moving around a means to gratify the donor and progressively opening up its petals as more and more funds are stored into its wallet. Once enough funds are secured, the Plantoid can use this money to reproduce itself, by commissioning a third party to produce a new Plantoid.

The smart contracts that instantiate these relationships contractually direct human actors to govern the DAO, to manufacture new Plantoids, and to exhibit (and return) the work. The danger of such DAOs is that of any embedded socioeconomic intent – whether corporations, charitable trusts or high frequency trading bots. We may end up with an economic Skynet that reduces us to peons in an algorithmic gig economy, any reflection of our actual needs or desires (such as to make art) perverted by the incentives encoded into an inhuman system. Plantoid exists to ensure the production of art, and its realisation by human artisans. Given the rockstar economics of the artworld and the continued collapse of socioeconomic support for artists outside it that production is badly in need of new means of continuance. The art-economic equivalent of “grey goo” – polychrome goo? – or Terminators armed with spraycans rather than phased plasma rifles seem much less likely scenarios than art DAOs becoming lifeboats or TAZes for the funding of art that is not simply decoration for the 1%. Plantoid’s explicit involvement of human producers in a comradely relationship makes it more a node in the network of collaborative and mutually supportive relationships in the peer economy than an Uberization of artistic production.

Any gap between the ambition and the technology of Plantoid can be crossed by its autopoeitic nature. Ethereum contracts cannot yet manage Bitcoin balances, for example, but using Ethereum’s existing native cryptocurrency “Ether” or one of the proposed systems for managing Bitcoin accounts from Ethereum would address this. Art’s function here, as in its development of religion at the dawn of history, is to create demand for the development of new means of production and relation that a dryly complete rational plan could not reach. Appropriately enough for such a hyperstitional work I discovered it via the blog of renegade philosopher Nick Land.

Without wishing to ventriloquise or reframe its achievements, Plantoid is an exemplary realisation of the potential of mutual interrogation and support of art and cryptocurrency. It’s an art project that uses cryptocurrency and smart contract systems to materially support itself. And that project makes the still abstract potential and operation of cryptocurrency and smart contract tractable to consideration through art. I for one welcome our new hyperstitional DAO artwork overlords.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Choose Your Muse is a series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

Annie Abrahams was born in the Netherlands to a farming family in a rural village in the Netherlands. In 1978 she received a doctorate in biology and her observations on monkeys inspired her curiosity about human interactions. After leaving an academic post she trained as an artist and moved to France in 1987, where she became interested in using computers to construct and document her painting installations. She has been experimenting with networked performance and making art for the Internet since the mid 1990s. Her works have been exhibited and performed internationally at institutions such as the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, New Langton Arts in San Francisco, Centre Pompidou in France, Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki and many other venues.

Through the years we have got to know Annie Abrahams via various online, networked artistic collaborations. In 2010, she had a her first one woman show If not you not me in the UK at Furtherfield’s earlier gallery space, the HTTP Gallery. Since then, she has shown at another mixed show at Furtherfield’s current space in Finsbury Park, London. This exhibition, Being Social included other artsists such as Karen Blissett, Ele Carpenter, Emilie Giles, moddr_ , Liz Sterry, and Thomson and Craighead.

She is known worldwide for her net art and collective writing experiments and is internationally regarded as a pioneer of networked performance art. She creates situations that reveal messy and sloppy sides of human behaviour; capturing real-time moments to illucidate a reality and opening it up, making it available for thought. In an interview with Bomb Magazine in 2014 Abrahams said “My first online performance was my first HTML page. Even then I considered the Internet to be a public space, and everything that I did in that public space asked for a reaction.” [1]

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Annie Abrahams: Life itself, the people I meet. Until now my basic needs in life have hardly been threatened and so the only real problems I encountered were relational problems. Who are you? Why are you different from me? What does it mean to respect you? Is opposing you necessary? And if so, how can I do that?

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

AA: My practice was always based on the difficulty of having to live in a world where I don’t understand anything. Every person I meet opens up another view on this impossibility. Sometimes I write short posts about my encounters. Lately I did one on Shirley Clarke and one on Ed Atkins’ No-one is more “Work” than me. aabrahams.wordpress.com

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

AA: My work is made from these influences. In the beginning I thought this was not ok, because I was educated with the idea that you have to be “unique” and make unique artworks. But now I am proud of my sensibility for what others say and do and the way I work with that.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

AA: Last summer I made a book called from estanger to e-stranger. Ruth Catlow described it as “all-at-once instruction manual, poetry and a series of vignettes of contemporary encounters in language-less places”. There you can find ideas and art works that inspire me, but in general I am not driven by inspiration, my acts are driven by irritation, my art by incomprehension. Art works sooth, make things bearable and sometimes incite to look beyond habits. Btw I am still continuing my research on how language shapes culture, society and me. http://e-stranger.tumblr.com/

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

AA: Stay close to your own concerns, to things you can have a concrete influence on, observe the results of your actions, pay attention, adapt, and always smile to your neighbour in the morning.

MG: Could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for readers to view, and if so why?

AA: For years now every now and then I’ve come back to Darren O’Donnell’s book “Social Acupuncture” and always again I say to myself, “yes, you can think and act art and politics together. Please have a look at the Mammalian Diving Reflex group’s (he is their artistic director) methods. http://mammalian.ca/method/

Featured image: A is for Art, B is for Bullshit: A history of conceptual art for badasses, book by Guido Segni 2015

“Outside of the Internet there’s no glory” Miltos Manetas”

Guido Segni, is an Italian artist whose activity began in the fields of hacktivism and Net Art in the 90s. As part of his practice he questions the nature of identity that resides on the Web (acting under many fake identities, like Dedalus, Clemente Pestelli, Guy McMusker, Angela Merelli, Anna Adamolo, Guy The Bore, Umberto Stanca,Silvie Inb, Fosco Loiti Celant, Guru Miri Goro, Leslie Bleus, Luther Blissett) and the value of digital activity with projects like 15 Minutes, anonymous, and The middle finger response.

The Internet and lists are two things that have always been together, especially now many of us use social networking platorms such as Twitter and Facebook. We can’t track how and when the first “Top 25/10/5” appeared on the Web, but it’s for sure one of the most frequent ways to gain a lot of attention from Internet users, and it can make you feel as if you’re trapped in a never ending, online fast-food loop. However, when I found out that Guido Segni had created his own version of a top 25 list I was naturally intrigued, so I decided to ask him what it was all about.

Filippo Lorenzin: How and when did you start working on Top 25 Expiring Artists?

Guido Segni: It all started in 2013 after a discussion with Luca Leggero, an artist friend of mine who was working on a piece about the ephemerality of internet art pieces, and it stimulated in me many thoughts on the subject. In the beginning I just wanted to create a sort of memento mori, a list of all artists’ expiring websites. It was only a few months later I introduced the idea of it as a competition, transforming the work into an ironic top artists ranking list, based on the expiration date of their websites.

FL: Could you tell us how it works and how are artists ranked on the list?

GS: It works as many of the other ranking lists you can find on the web. The difference stands on the criteria. While many lists circulating on the web (Top 10 young artist to follow, Top 5 internet artist, etc) are often based on unintelligible criteria, in TEIA (Top Expiring Internet Artists) the criteria are as clear as useless and absurd: the whole list is in fact ordered by the expiration date of the artist website. The nearer is the website expiration date, the better ranking the artist website will obtain. It’s a democratic but very competitive race where everyone can reach the first position even if just for a day. Top 25 Expiring Artists is automagically updated every day – you can only see the top 25 but actually the project counts more than 50 artists. To be included in this list an artist just needs to make an email submission sending the URL of his/her/its website.