Way back in 1995, the artist collective Critical Art Ensemble (CAE), said “What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself. The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world.” These words now haunt us, and take their place alongside numerous other ignored warnings about global threats to the wellbeing of our societies and the planet.

In this interview with curator Dani Admiss, we discuss how the data-driven gamification of life and everything has shaped the development of Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival at Furtherfield and why the Gallery is currently being transformed into a psychological environment.

Gallery visitors are presented with a series of game-like installations, which are the result of the shared and collective cognitive labour of artists, curators and gallery staff. First the artists, and then the public (as players) are invited to test the processes and experiences offered by new mechanisms of play and labour. Each ‘game’ simulates an experience of how some techniques and technologies of gamification, automation, and surveillance, are at work in our everyday lives, in order to capture all forms of existence.

Marc Garrett: Before the exhibition, you initiated an open call for a Lab. You invited participants to join a three-day art and research lab at Furtherfield Commons, Finsbury Park, London. Could you elaborate why you did this and how it informed the exhibition?

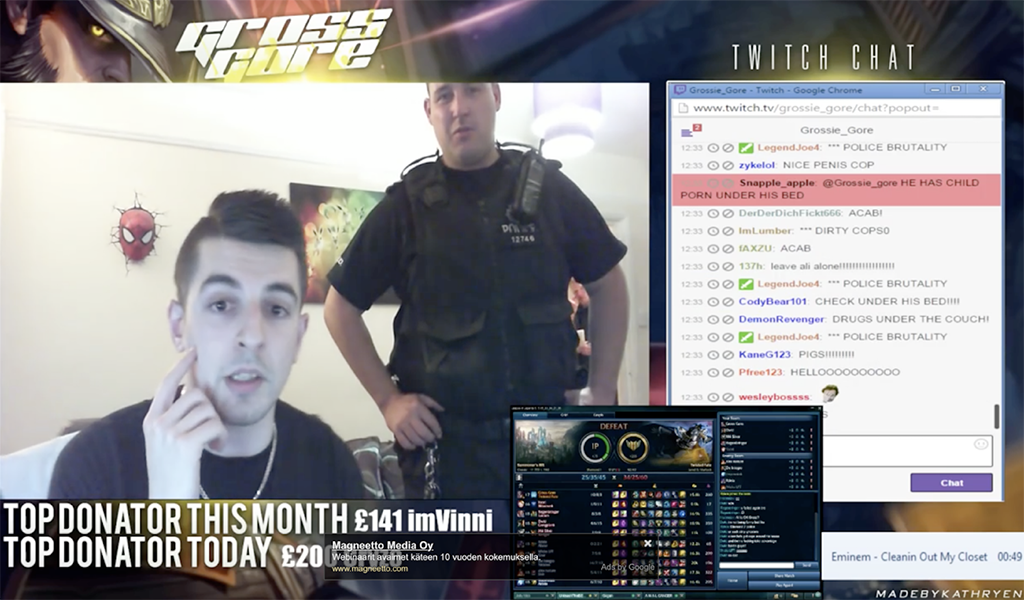

Dani Admiss: A couple of months before the exhibition, I ran a 3 day co-research lab that brought together artists, designers, activists, and researchers. I like to refer to it as a performative, temporary exhibition in the form of a lab. There were discussions, performances, interventions, games, and exercises. We had discussion with Jamie Woodcock on gaming and digital labour, he walked us through an interview session with gamers on the Twitch platform. Steven Levon Ounanian held a performative experiment where we thought about how we might render the suffering online in the real world, Itai Palti worked with us to think about design principles and neuroscience. FUN! The idea was that we would collectively explore, discuss and define key issues that we thought were important to then take forward to develop into games and experiences to share with the public. The aim was to play off each other in a live context to generate new perspectives and ideas.

Building on this, I decided to hold an open call for participants. In my most idealistic moment, I’d say I wanted to try and find ways to expand who gets to produce, stage and display, how we define what these issues actually are for wider audiences. Can this lead to new stories about art, tech, society? Like any project it is never exactly as you imagined it, but I think the majority of people got a lot out of working like this. I did. Working with people that aren’t always the people you expect to be attached to a project always throws up unexpected experiences. Everyone brought their best themselves with them. Open. Interested. Warm. Prepared. Ready to listen, and for fun!

I’d make the lab longer next time, so it wasn’t as intense, and I’d try to have more people join the open call.

MG: The open-curation process you have developed is core to the realisation of the Playbour lab and exhibition. It resonates strongly with Furtherfield’s DIWO ethos. It turns on its head, the traditional approach to curating thematic group shows. Please can you tell us about the process and say why this new approach is important at this time?

DA: DIWO definitely informed Playbour! I think the spirit of co-creative discovery is a powerful tool that curators should use more. I refer to it as co-research, which is ultimately a way to research-with others. What separates it from more traditional approaches to curating is the unclear distinction between author/researcher and subject/participant. The aim is to achieve closer equality between the participant and subject area, in the form of valuing a person’s idea’s and lived-experience as much as other ‘expert’ forms of knowledge. Historically, it has roots in a highly specific context of the radical Left in post-war Italy with Operaismo. This is where the seeds of debate on post-immaterial labour emerged, arising from Hardt, Negri, Bifo, Terranova, etc, and why I originally was interested in working in this way because of the subject matter of the project, however, it became something so much more.

For me, as a curator, creating projects about complex subject areas that bring together embodied and embedded social relations with technical worlds, is something that needs to be done with people rather than to them. I think the most interesting works of art being produced today are treated less like things and instead draw into the very making of the ways in which we get to know what we know. You can see this in works from Cassie Thornton’s project Collective Psychic Architecture (an exploration of “bad support” in Sick Times) 2018, where she extends the responsibilities of the gallery or institution through performative means, or in the high-profile modeling and mapping practices coming out of the Forensic Architecture network. How can curating exist in a wider space than before? I’m trying to work in much more extended and expanded ways with the primary intention to include more end users into the areas we are looking at.

Adopting a co-research model (in the lab, in the show, in the publication, in the micro-commissions) meant that the aim of the exhibition shifts, it becomes less about what the topic is and how it works and more about how it came to be. Brian Holmes once wrote that making an image remakes the world. Yes, but it also distances us from it. Playbour asks people to consider how the world organises us by facilitating moments where people can identify with particular phenomena. I feel this is more fitting and has more potential to create moments of personal learning and change than trying to represent it through curatorial practice. Why do we need this in an age of information? My thinking is that knowledge-projects are not simply objective processes but deeply subjective ones that are enacted through and with others. Finding ways for people to identify in more meaningful ways with the subject will hopefully lead to greater chance that people will gain greater perspective and agency over their own worlds.

MG: The term Playbour brings attention to critiques of gamification and to the extraction of value via social media platforms. But your subtitle then opens up a whole other world of reflection. What are you discovering about the relationship between “work, pleasure and survival”?

DA: The project is exploring the role of the worker in the age of data technologies, but this looks less at the “future of work” and chooses instead to focus on the shifting roles and blurred boundaries of work, play and well-being – how do we place value on these areas, how do we work with and against them?

Quite often when we talk about opaque terms like immaterial labour and cognitive capitalism we fail to grasp the production processes of these phenomena. Immaterial labour depends on the self and our social relations. We are asked to ‘post’, ‘share’, ‘network’, ‘emote’, ‘communicate’, ‘know’. Not so much ‘understand’. These acts inform the control and creation of our subjectivity. At the same time, very little discussion is happening about the fact that so much exploitation -physical, ecological, economical- sits behind the new commons we are all talking about.

Opening the project out to think about work, pleasure, survival, is a provocation. On one level, it is a nod to the fact that this conversation is for a privileged few. Many choose what they do and this ‘choice’ is supposed to operate as an expression of one’s personality. On the other, it’s human nature to get swept up in what is considered the norm, so it’s also a challenge to think about what are your own limits, returning to the idea of inviting people to find moments of identification with these broader issues to their own lived experience.

MG: Why is it important that the work being prepared for Furtherfield gallery is conceived of more, as a series of game experiences, than a display of discrete art objects, or a didactic exhibition on the topic of Play and Labour? Has the gallery’s location in a public park influenced your thinking at all?

DA: Well, first off, it has been a collective process and so I wanted to show that process to people. Secondly, you have to invest part of yourself in play. The more I research the areas of digital and immaterial labour the more I’m keen to work with others to understand the not yet completed transformations of body, society, and world, into a global capitalist system. These are suffuse and pervasive and nudge our behaviours all of the time. Organising the exhibition as experiences is a way for us all to live-out (at least temporarily and in a safe, playful space) the tentacular effects of immaterial labour and economies of knowledge and information. This is not to say let’s walk away from a highly networked society, it’s an invitation back into perspectival agency.

MG: You’ve chosen to put together three themes for the exhibition, ranging across work, pleasure, and survival. Why was it important to choose these three themes in particular?

DA: I’m fascinated by how we are involved in the making of worlds we are then conditioned by. From the learnings in the lab, my own research and collaborations leading up to Playbour, I think gamification, automation, and surveillance are three key areas that scaffold a lot of the debate on digital and immaterial labour.

1) SURVEILLANCE. How we are measured and how we measure ourselves? Traditionally, government control used to come from top-down surveillance techniques, such as the type Michael Straeubig’s Hostile Environment Facility Training (HEFT) is looking at. However, I think we should be talking about how forms of control are exercised through our own self-monitoring processes – self-improvement culture is a perfect example of this. Cassie Thornton’s Feminist Economics Yoga (FEY), is a wonderful remedy for this.

2) AUTOMATION. How technology is removing decision-making from us in the pursuit of a frictionless universe. In Harrison-Mann’s Public Toilet he is talking about how automation is used to address the need of social issues. The starting point is the lack of public services offered in Finsbury Park and how that is altering how we use and experience the public space of the park. He is interested in making a connection between this and how metrics can often end up being exercised in controversial and even arbitrary ways inhibiting people getting what they need, such as disability benefits in the UK.

3) GAMIFICATION. How are rewards and competition embedded into our online interactions and interfaces? Jamie Woodcock has this excellent term that describes gamification-from-above and gamification-from-below. Like the Situationist socialism-from-below. How we might use gamification for our own positive manipulations, diversions and distractions? I think a lot of media and new media practice has long been engaged in gamification-from-below. Marija Bozinovska Jones’ piece Treebour (201) plays on this, transferring manipulation of social relations levelled at online interactions to the “natural” networking of trees.

MG: After visitors have experienced the exhibition, what emotions, thoughts and understandings, would you like them to leave with?

I think you introduced the show in an interesting way in your opening text with the notion of the data body and the extension of our bodies into new spaces with unknown consequences. These happen inside the screen, at the edges of the world, in transit, at the end of the supply chains. At the same time, they also operate on semi-conscious refrains, in our behaviours, actions, thoughts and emotions about the world. Taking part, thinking-with, making-with, are strategies to find ways to open up discussions about how we are all involved in making and unmaking our worlds via different actions. Something like digital and immaterial labour is not a discrete issue reservable for experts who work in this area, the connections and consequences weave in and out of our lives and impact us all. We are constantly reacting to thing around us, taking in these cues and pushing them back out into the world.

In terms of emotions, I don’t want to spread fear and despair, I’m hoping that some visitors will identify with some of the ideas in the show and relate them to something in their life that perhaps they’d not thought of in that way before.

Notes: Main top image by Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour 2018.

DIWO – Do It With Others: Resource

archive.furtherfield.org/projects/diwo-do-it-others-resource

Since the financial crash 10 years ago, we’ve learned that it tends to be everyday people, on the ground, who pick up the pieces and not governments. Millions have been dragged into poverty while those who caused the “crisis”, after creating dangerously high levels of private debt, remain unscathed. [1] The UK Conservative government’s response was an Austerity policy, driven by a political desire to reduce the size of the welfare state. Amadeo Kimberly says, “austerity measures tend to worsen debt […] because they reduce economic growth.”[2] The effect has been devastating, creating all together, more homelessness, precarious working conditions and thus pushing working communities, deeper into debt. In the UK, the NHS is being privatized as we speak. According to a CNBC report, medical bills were the biggest cause of bankruptcies in the U.S in 2013, with 2 million people adversely affected. [3]

The work of artist and activist, Cassie Thornton is included in the upcoming Playbour– Work, Pleasure, Survival exhibition at Furtherfield, curated by Dani Admiss. In this interview I wanted to explore the following questions as revealed in her current Hologram project:

Cassie Thornton is an artist and activist from the U.S., currently living in Canada. Thornton is currently the co-director of the Reimagining Value Action Lab in Thunder Bay, an art and social center at Lakehead University in Ontario, Canada.

Thornton describes herself as feminist economist. Drawing on social science research methods develops alternative social technologies and infrastructures that might produce health and life in a future society without reproducing oppression — like those of our current money, police, or prison systems.

Marc Garrett: Since before the 2008 financial collapse, you have focused on researching and revealing the complex nature of debt through socially engaged art. Your recent work examines health in the age of financialization and works to reveal the connection between the body and capitalism. It turns towards institutions once again to ask how they produce or take away from the health of the artists and workers they “support”. This important turn towards health in your work has birthed a series of experiments that actively counter the effects of indebtedness through somatic work, including the Hologram project.

The social consequences of indebtedness, include the formatting of one’s relationship to society as a series of strategies to (competitively) survive economically, alone, to pay the obligations that you has been forced into. It takes so much work to survive and pay that we don’t have time to see that no one is thriving. Those whom most feel the harsh realities of the continual onslaught of extreme capitalism, tend to feel guilty, and/or like a failure. One of your current art ventures is the Hologram, a feminist social health-care project, in which you ask individuals to join and provide accountability, attention, and solidarity as a source of long term care.

Could you elaborate on the context of the project is, as well as the practices, and techniques, you’ve developed?

CT: Many studies show that the experience of debt contributes to higher levels of anxiety, depression, and suicide. Debt disables us from getting the care we need and leads us away from recognizing ourselves as part of a cooperative species: it is clear that debt makes us sick. In my work for the past decade, I have been developing practices that attempt to collectively discover what debt is and how it affects the imagination of all of us: the wealthy, the poor, the indebted, financial workers, babies, and anyone in-between. Under the banner of “art” I have developed rogue anthropological techniques like debt visualization or auxiliary credit reporting to see how others ‘see’ debt as an object or a space, and how they have been forced to feel like failures in an economy that makes it hard for anyone (especially racialized, indigenous, disabled, gender non-binary, or ‘immigrant’) to secure the basic needs (housing, healthcare, food and education) they need to survive, because it is made to enrich the already wealthy and privileged.

“The rise of mental health problems such as depression cannot be understood in narrowly medical terms, but needs to be understood in its political economic context. An economy driven by debt (and prone to problem debt at the level of households) will have a predisposition towards rising rates of depression.”[4]

After years of watching the pain and denial around debt grow for individuals and entire societies, I was so excited to fall into a ‘social practice project’ that has the capacity to discuss and heal some of this capital-induced sickness through mending broken trust and finding lost solidarity. This project is called the hologram.

MG: What kind of people were involved?

CT: The entire time I lived in the Bay Area I was precarious and indebted. I only survived, and thrived, because of the networks of solidarity and mutual aid I participated in. As the city gentrified beyond the imagination, I was forced to leave. I didn’t want to let those networks die. So, at first, the people who were involved were like me– people really trying to have a stake in a place that didn’t know how to value people over real estate and capital

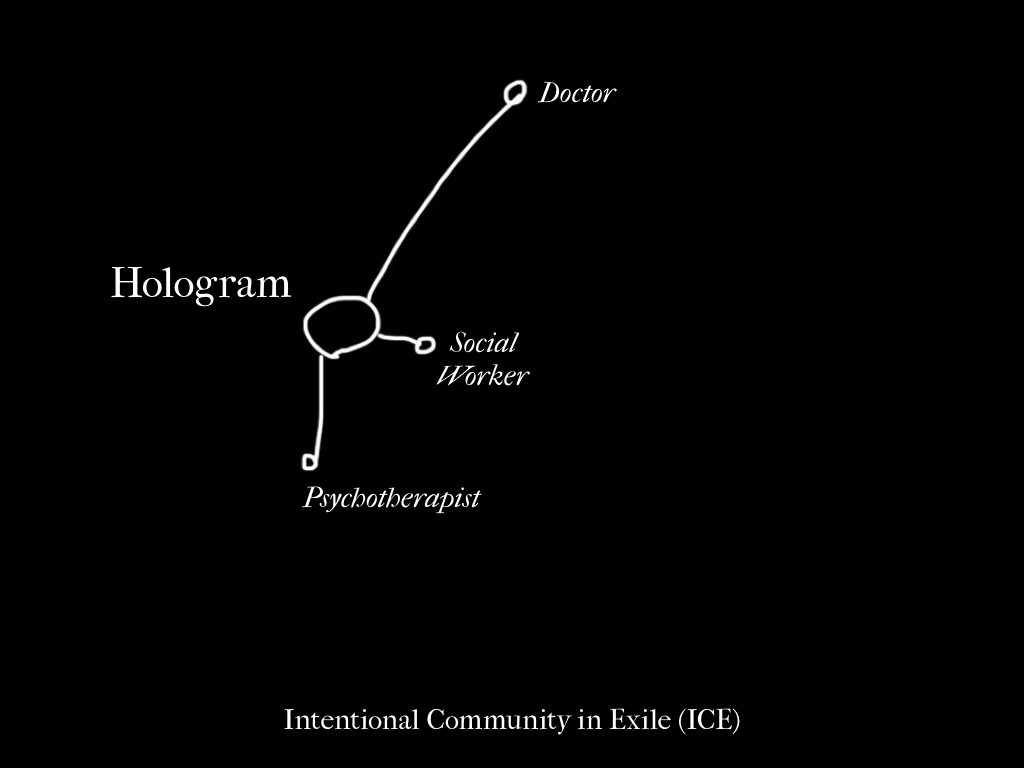

The hologram project developed when, as I was leaving the city, I had invited a group of precariously employed, transient activists and artists to get together in the Bay Area for a week of working together. We aimed to figure out ways to share responsibility for our mutual economic and social needs. This project was called the “Intentional Community in Exile (ICE)” [the ICE pun was always there, now an ever more intense reference in the public eye] and it grew out of an opportunity offered by Heavy Breathing to choreograph an event at The Berkeley Art Museum. They allowed me to go above and beyond my budget to invite a group of 8 women together from across the US to choreograph methods of mutual aid: sharing resources, discussing common problems and developing methods for cooperating to co-develop an economic and social infrastructure that would allow us to thrive together, interdependently. What would it mean for our work as activists and artists to feel that we had roots within an intentional community, even if we didn’t have the experience of property that makes most people feel at home?

Facebook event: “In departing from the idea of a long term home, family, property, or ownership, ICE models a mutual aid society to sustain creative and political practices within a hostile economic system. This project is about finding ways to exit economic precarity by building human relationships instead of accumulating capital– or to make exile warm. After a one week convergence of a small group of collaborators, ICE presents a discussion and performance of life practices as well as frameworks for material and immaterial mutual support.”

The Hologram was one of many ideas that developed as part of this project. One of the group members, Tara Spalty, founder of Slowpoke Acupuncture, (and one of the two acupuncturists you will see at SF protests or homeless encampments) and I fell into this idea when combining our knowledge about the solidarity clinics in Greece, our growing indebtedness and lack of medical records, and the community acupuncture movement. Then the group brainstormed about what the process would be like to produce a viral network of peer support.

MG: What inspired you to do this project? (particularly interested in the Greek influences here and what this means to you)

CT: My practice of looking at debt became boring to me by 2015 as it became more and more clear that individual financial debt was a signal of a larger problem that was not being addressed. The hyper individualism produced by indebtedness allows us to look away from a much bigger deeper story of our collective debts, financial and otherwise. We don’t know what to do with these much bigger debts, which include sovereign debts, municipal debts, debts to our ancestors and grandchildren, debts to the planet, debts to those wronged by colonialism and racism and more. We find it so much easier to ignore them.

When visiting austerity-wracked Greece after living in Oakland, I noticed that Oakland appeared to have far more homeless people on the street. It made me realize that, while we label some places “in crisis,” the same crisis exists elsewhere, ultimately created and manipulated by the same financial oligarchs. The hedge funds that profit off of the bankruptcy in Puerto Rico are flipping houses in Oakland and profiting off of the debt of Greece. We’re all a part of the same global economic systems. The “crisis” in Greece is also the crisis Oakland and the crisis in London. For this reason, I have been interested in what we can all learn from activists, organizers and others in crisis zones, who see the conditions without illusions.

This led me to an interest in the the Greek Solidarity Clinic movement, which since “the crisis” there has mobilized nurses, doctors, dentists, other health professionals and the public at large to offer autonomous access to basic health care. I went to go visit some of these clinics with Tori Abernathy, radical health researcher. Another project using this social technology is called the Accountability Model, by the anonymous collective Power Makes Us Sick. These solidarity clinics are run by participant assembly and are very much tied in to radical struggles against austerity. But they have also been a platform for rethinking what health and care might mean, and how they fit together. The most inspiring example for me was in at a solidarity clinic in Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece. The “Group for a Different Medicine” emerged with the idea that they didn’t want to just give away free medicine, but to rethink the way that medicine happens beyond conventional models, including specifically things like gender dynamics, unfair treatment based on race and nationality and patient-doctor hierarchies. This group opened a workers’ clinic inside of an occupied factory called vio.me as place offer an experimental “healed” version of free medicine.

When new patients came to the clinic for their initial visit they would meet for 90 minutes with a team: a medical doctor, a psychotherapist and a social worker. They’d ask questions like: Who is your mother? What do you eat? Where do you work? Can you afford your rent? Where are the financial hardships in your family?

The team would get a very broad and complex picture of this person, and building on the initial interview they’d work with that person to make a one-year plan for how they could be supported to access and take care of the things they need to be healthy. I imagine a conversation: “Your job is making you really anxious. What can we do to help you with that? You need surgery. We’ll sneak you in. You are lonely. Would you like to be in a social movement?” It was about making a plan that was truly holistic and based around the relationship between health, community and struggles to transform society and the economy from the bottom-up . And when I heard about it, I was like: obviously!

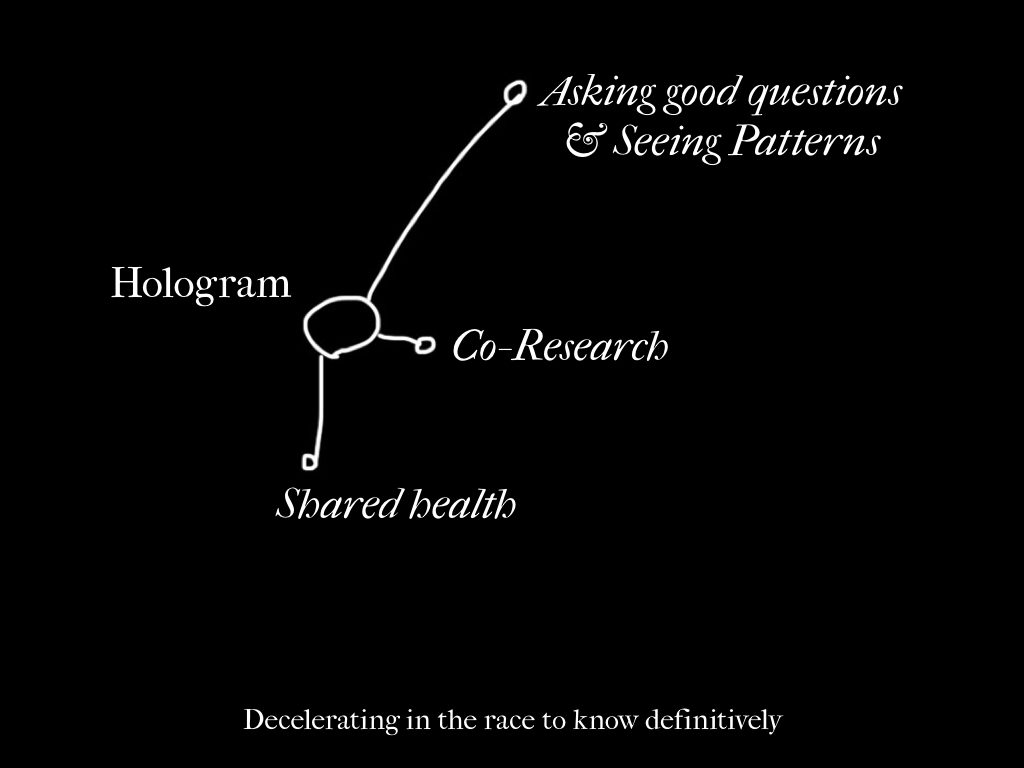

So the Hologram project is an attempt by me and my collaborators in the US and abroad to take inspiration from this model and create a kind of viral network of non-experts who organize into these trio/triage teams to help care for one another in a complex way. The name comes from a conversation I had with Frosso, one of the members of the Group for a Different Medicine, who explained that they wanted to move away from seeing a person as just a “patient”, a body or a number and instead see them as a complex, three dimensional social being, to create a kind of hologram of them.

MG: Could you explain how the viral holographic care system works?

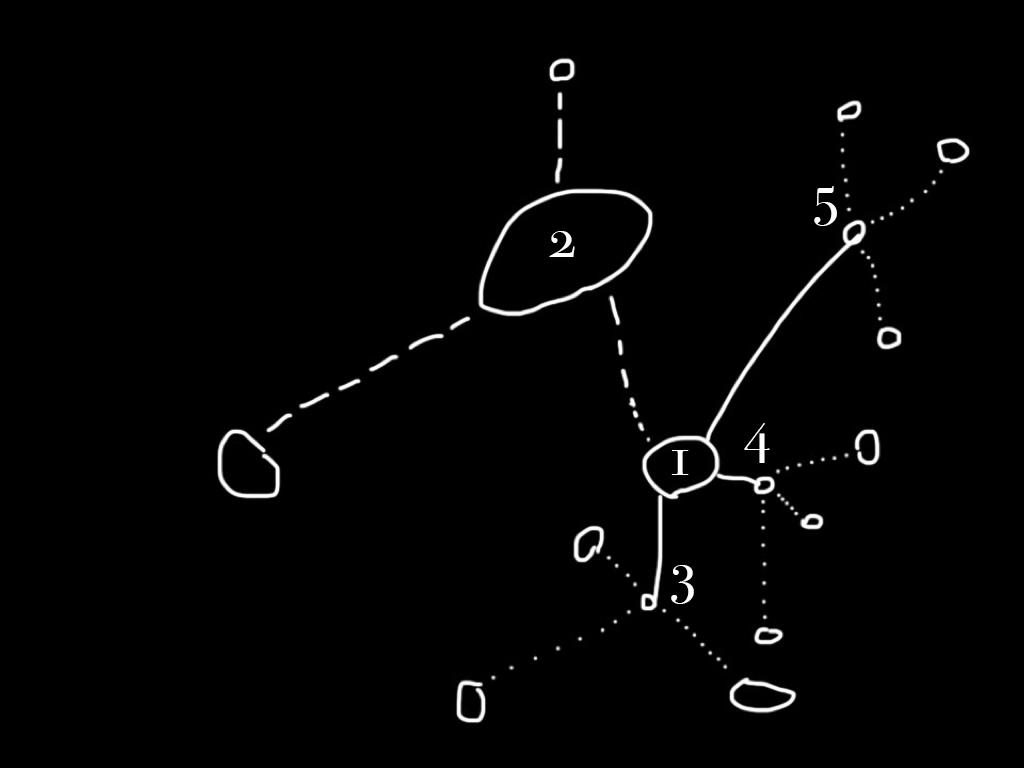

CT: Based on the shape above, we can see that we have three people attending to one person, and each person represents a different quality of concern. In this new model, these three people are not experts or authorities, but people willing to lend attention and to do co-research, to be a scribe, or a living record for the person in the center, the Hologram. We call these three attendees ‘patience’. Our aim is to translate the Workers’ Clinic project to a peer to peer project where the Hologram receives attention, curiosity and long term commitment from the patience looking after her, who are not professionals. Another project using this social technology is called the Accountability Model, by the anonymous collective Power Makes Us Sick.

So the beginning of the process, like that of the Workers’ Clinic, is to perform an initial intake where the three patience ask the Hologram questions which are provided in an online form, about the basic things that help or hurt her social, physical and emotional/mental health. When this (rather extended) process is complete, the Hologram will meet as a group every season to do a general check in. The goal of this process is to build a social and a physical holistic health record, as well as to continue to grow the patience understanding of the Hologram’s integrated patterns.

Ultimately, over time we hope to build trust and a sense of interdependence, so that if the Hologram meets a situation where she has to make a big health decision (health always in an expansive sense) about a medical procedure, a job, a move, she will have three people who can support her to see her lived patterns, to help her ask the right questions, and to support peer research so that the Hologram is not making big decisions unsupported.

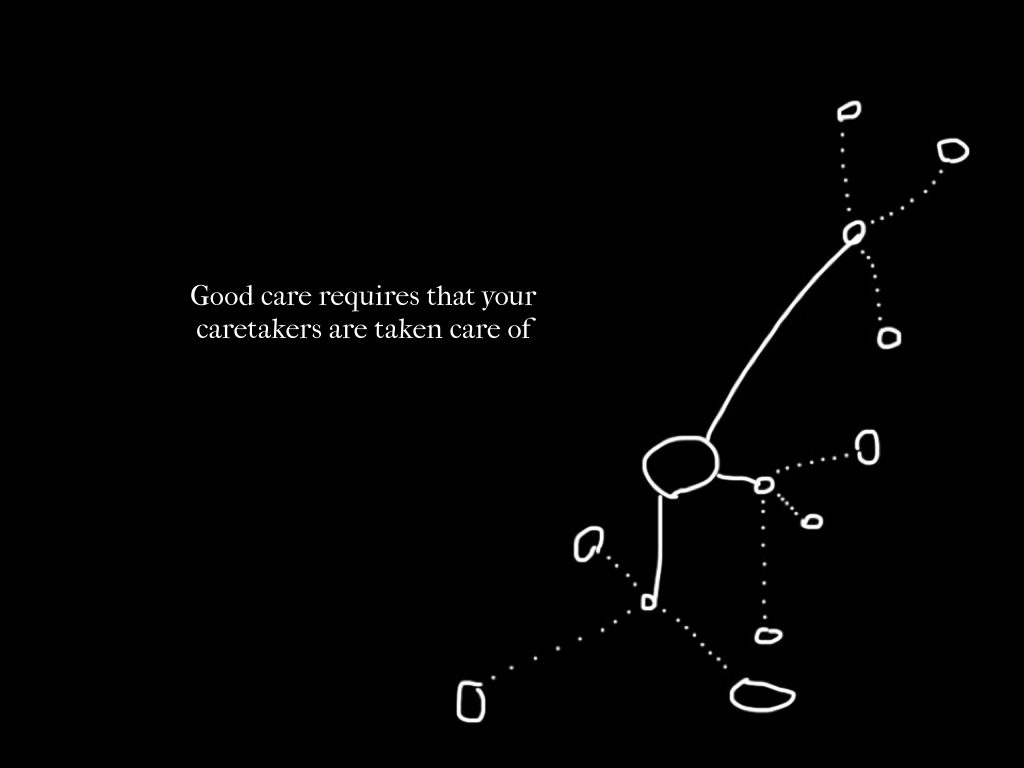

But, in order for the Hologram to receive this care without charge and guilt free, she needs to know that her patience are taken care of as she is. I think this is one part of the project that acknowledges and makes a practice built from the work of feminists and social reproductive theorists – you can’t build something new using the labor of people without acknowledging the work of keeping those people alive; reproducing the energy and care we need to overturn capitalism needs a lot of support. Getting support from someone feels so different if you know they are being, well taken care of. This is also how we begin to unbuild the hierarchical and authoritarian structures we have become accustomed to – with empty hands and empty pockets.

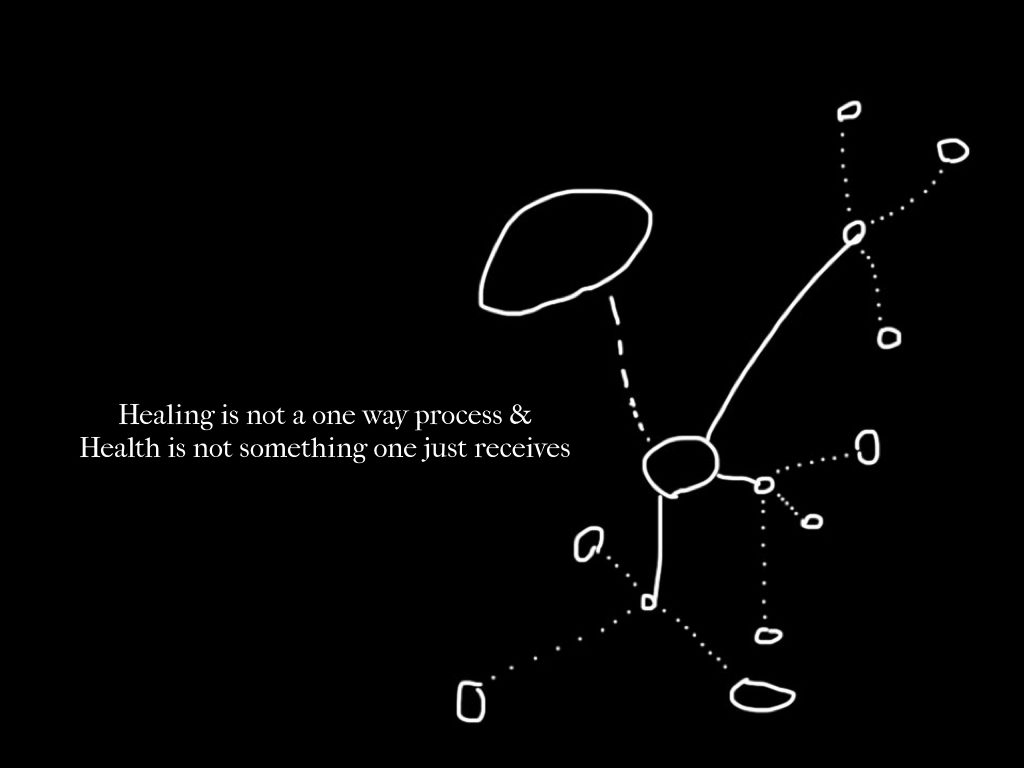

And then, the last important structural aspect of the Hologram project is the real kicker, and touches on the mystery of what it means to be human outside of Clientelist Capitalism – that the real ‘healing’ (if we even want to say it!) comes when the person who is at the center of care, turns outward to care for someone else. This, the secret sauce, the goal and the desired byproduct of every holographic meeting– to allow people to feel that they are not broken, and that their healing is bound up in the health and liberation of others.

The viral structure, is built into this system and there is a reversal of the standard way of seeing the doctor and patient relationship. In this structure it is essential that we see the work of the Hologram as the work of a teacher or explicator, delivering a case that will ultimately allow the patience to learn things they didn’t previously know. This is the most important, (though totally devalued by money) potent and immediately applicable, form of learning we can do, and it is what the medical system has made into a commodity, at the same time as it is seen as ‘women’s work’ or completely useless.

MG: Could you take us through the processes of engagement. For instance, you say a group of four people meet and select one person who will become a Hologram, and that this means they and their health will become ‘dimensional’ to the group. Could you elaborate how this happens and why it’s important for those involved?

CT: We are about to experiment, this fall, with what it means for these groups to form in different ways. We will start with four test cases, where an invited, self-selected person will become a Hologram. She will be supported to select three Patience in a way that suits her, based on an interview and survey. The selection of Patience is a part of the process that we have not had a chance to refine. It is not simple for any individual to understand what support looks like for them, or who they want support from, if they’ve never really had it.

The experiments we will work through this fall will attempt to understand what changes in the experience of the whole Hologram when the Hologram is supported by Patience who are trusted friends and family, acquaintances or highly recommended strangers. An ‘objective’ perspective from an outside participant also adds a layer of formality to the project, because, instead of a casual gathering of friends, an unfamiliar person signals to the other members of the hologram to be on time, and make the meetings more structured than a regular friend to friend chat.

The onboarding process for the Hologram and the Patience includes a set of conversations and a training ritual, which are still quite bumpy. The two roles every participant is involved in, requires a different set of skills, and so they both involve a special kind of “training” that one can do in a group or independently. This “training” is a structured personal ritual that allows participants to witness and adapt their own communication habits so that they feel prepared to participate and set up trust, curiosity and solidarity for the group in the opening intake conversations.

At the completion of the intake process, the Hologram (1) transitions to become a Patience. At this time, the Hologram (1) begins a short training to transition to the other role, and she is supported by her Patience to do this work. At the conclusion of the Hologram’s (1) transition to Patience, and the completion of the new Hologram’s (2) intake process, the original Hologram’s (1) Patience become Holograms (3,4,5).

MG: The Hologram project was first trialed as part of an exhibition called Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time at the Elizabeth Foundation Project Space in New York City, March 31-May 13, 2017. What have you learnt in more recent undertakings of The Hologram project?

CT: Since the original trial one year ago, which lasted for 3 months, the research has shifted to looking at building skills and answering acute questions that will accumulate to support and build the larger project. Starting in the Spring of 2017, I began to offer the Hologram project as a workshop, where participants could test the communication model that is implicit in the Hologram format. The method for offering it is, as a performance artist and rogue architect, creating a situation in a space where people go through a difficult psycho social physical experience together. In the reflective conversations that follow, I ask the groups to use the personal pronoun ‘we’ for the entire duration of the conversation. The idea is that one person’s experience can be shared by the group, and even as temporary Patience we can take a leap and share their experience with them for a duration of time, allowing a Hologram to feel as if their experience is “our” experience. And this feeling that one is not alone in an experience, if carried into other parts of life, has the potential to break a lot of the assumptions and habits that we have inherited from living and adapting to a debt driven hellscape.

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

Would you like to monetise your social relations? Learn from hostile designs? Take part in (unwitting) data extractions in exchange for public services?

Examining the way that the boundaries between ‘play’ and ‘labour’ have become increasingly blurred, this summer, Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival, will transform Furtherfield Gallery into an immersive environment comprising a series of games. Offering glimpses into the gamification of all forms of life, visitors are asked to test the operations of the real-world, and, in the process, experience how forms of play and labour feed mechanisms of work, pleasure, and survival.

What it means to be a worker is expanding and, over the last decade, widening strategies of surveillance and new sites of spectatorship online have forced another evolution in what can be called ‘leisure spaces’. From the self-made celebrity of the Instafamous to the live-streaming of online gamers, many of us shop, share and produce online, 24/7. In certain sectors, the seeming convergence of play and labour means work is sold as an extension of our personalities and, as work continues to evolve and adapt to online cultures, where labour occurs, what is viewed as a product, and even, our sense of self, begins to change.

Today, workers are asked to expand their own skills and build self-made networks to develop new avenues of work, pleasure and survival. As they do, emerging forms of industry combine the techniques and tools of game theory, psychology and data science to bring marketing, economics and interaction design to bear on the most personal of our technologies – our smartphones and our social media networks. Profiling personalities through social media use, using metrics to quantify behaviour and conditioning actions to provide rewards, have become new norms online. As a result, much of public life can be seen as part of a process of ‘capturing play in pursuit of work’.

Although these realities affect many, very little time is currently given over to thinking about the many questions that arise from the blurring between work and play in an age of increasingly data-driven technologies: How are forms of ‘playbour’ impacting our health and well-being? What forms of resistance could and should communities do in response?

To gain a deeper understanding of the answers to these questions, we worked with artists, designers, activists, sociologists and researchers in a three-day co-creation research lab in May 2018. The group engaged in artist-led experiments and playful scenarios, conducting research with fellow participants acting as ‘workers’ to generate new areas of knowledge. This exhibition in Furtherfield Gallery is the result of this collective labour and each game simulates an experience of how techniques of gamification, automation and surveillance are applied to the everyday in the (not yet complete) capture of all forms of existence into wider systems of work.

In addition to a performance by Steven Ounanian during the Private View, the ‘games’ that comprise this exhibition are:

Lab session leads and participants: Dani Admiss, Kevin Biderman, Marija Bozinovska Jones, Ruth Catlow, Maria Dada, Robert Gallager, Beryl Graham, Miranda Hall, Arjun Harrison Mann, Maz Hemming, Sanela Jahic, Annelise Keestra, Steven Levon Ounanian, Manu Luksch, Itai Palti, Andrej Primozic, Michael Straeubig, Cassie Thornton, Cecilia Wee, Jamie Woodcock.

Curated by Dani Admiss.

Concept development Dani Admiss and Cecilia Wee.

Mask Making for Children

Sunday 22 July and 12 August 2018, 11:00 – 16:30

Furtherfield Gallery

FREE

Dani Admiss

When I was 16 I was in a band. I couldn’t sing that well so I used to write lyrics (about vampires) and put them into Babelfish to translate them into French thinking it made me sound automatically cooler.

@daniadmiss

Kevin Biderman

First met you in a dial up world; green block letters on a black screen. Later we traversed through neon colours, pixelated images and imperfect designs. I always knew you were an army brat born out of apocalyptic fears but I never thought you’d turn your back on the counter-culture who raised you. Maybe there will be a third act…

@act3

Marija Bozinovska Jones

The internet has concurrently enhanced and diminished life, yet I appear no longer able to recall life before it. Adding to Jameson’s quote: it is easier to imagine the end of the world, than the end of TECHNOcapitalism.

Ruth Catlow

I am a recovering Web Utopian – decentralised infrastructure does not, it turns out, lead automatically to decentralised power. However i am still most excited by art that happens in wild flows, through collaboration on open channels, rather than being owned, certified and traded like dead matter. I am Ruth and I am one of the voices and pairs of eyes.

@furtherfield

Maria Dada

I regularly translate whole books from German to English using Google Translate. I then take the transcripts and print them using lulu.com. I take pride in the design of the covers for each book. Not all of them are unreadable but most of them just sit on my shelf untouched.

@mariadada

Beryl Graham

I confess:

To buying a mobile phone so that I could text my sweetie.

To being mildly obsessed with weather apps that work best in the North.

To using online dating 15 years ago. The respectable Guardian rather than Tindr of course – hey I’m not an animal.

@berylgraham

Miranda Hall

After school, my friend and I would take screenshots of penises on ChatRoulette then save them in a desktop folder on the family computer called ‘cool fish’

@Miranda__Hall

Arjun Harrison-mann

For Much Longer than I Would Care to Admit, Every Since I Got Msn at the Age of 12, My Msn Profile Picture Was (and I Just Checked, Still Is), a Photoshopped Collage of Michael Jordan.

@arjun_harrisonmann

Maz Hemming

When I was 11, lying about my age to sign up on msn chat to chat about neopets, I ended up as one of the chatroom moderators. Which sometimes ended up with me leaving the window open to idle overnight (or the room would close). On the bonus side when my parents ended up with a bill at the end of the month of £200 (which I didn’t know would happen) we did get broadband. Much cheaper.

@MazHem_

Robert Gallagher

The unread emails in my inbox currently outnumber my Twitter followers by a factor of 47.7461024499 to 1.

@r_gealga

Sanela Jahić

Once my inbox got flooded with promotions of an online store. So my boyfriend and I composed a simple bot, which took random quotes from our sci-fi eBooks collection and posted them as customer reviews on their product pages.

Annelise Keestra

Until more recently than I would admit, I genuinely didn’t think there was any correlation between the file size of a download and data use. As if, there were two kinds of “GB”. Please don’t judge me.

@aut0mne

Steven Levon Ounanian

I think the internet loves me, but just doesn’t know how to show it.

@levontron

Manu Luksch

Our dream rewired. Our powers of prediction grow with every new circuit crammed in. Leap into tomorrow – one trillion calculations a second. And it grows more powerful, becomes smaller. Smart, mobile, personal. Today – in our pockets. Tomorrow – woven into our bodies. Create and share, everything, everywhere. Life in the cloud… with a chance of blue skies. Our time is a time of total connection. Distance is zero. The future is transparent. To be, is to be connected – the network seeks out everyone.” (Dreams Rewired; 2015 – my latest feature film about our hopes and fears of being hyper-connected).

@ManuLuksch

Itai Palti

I started visiting an architecture news forum as a teenager, excited about updates on local building projects. I still visit regularly for the updates, but also make sure to check on an exceptionally cringeworthy, decades-long feud between a couple of regular posters. I think they’d really miss each other if it all stopped.

@ipalti

Joana Pestana

Back in 1999, frustrated, I nurtured no love for my iMacG3 as I had to bare with 1-song-download-per-week for not having Napster.

@joanampestana

Michael Straeubig

Before social networks and Reddit, newsgroups were the places for online discussions. Catering to my interests was comp.ai.philosphy, a group notorious for debates going haywire.

Once I had a very heated discussion with someone I considered to be an immature and irrational teenager. It turned out it was a professor in Artificial Intelligence.

@crcdng

Cassie Thornton

I own/owned these URLs: bizzykitty.com, temporaryartbeautyservices.biz, infinitemuseum.com, evilarchitexture.net, teachingartistunion.org, sfluxuryrealestatejewelry.org, mastercalendar.biz, debtimage.work, institutionaldreaming.com, poetsecurity.net, universityofthephoenix.com, debt2space.info, secretchakra.net, wombco.in, givemecred.com, wealthofdebt.com, strikedebtradio.org, matterinthewrongplace.info, futureunincorporated.com, feministeconomicsdepartment.com, projectherapy.org, and many more I will never remember.

@femnistecondept

Cecilia Wee

The first time I went on the internet was about 1 year after Cyberia cafe opened in central London. I somehow convinced my mum to make a detour from a shopping trip so I could go online to look at 2 websites. Everyone else there was working very hard.

@ceciliawee

Jamie Woodcock

I decided it would be a fun idea to learn to play League of Legends as part of the fieldwork for an esports project. However, I was so bad at it that instead I had to study before playing, reading up on guides and watching streams/videos.

@jamie_woodcock

In the lead up to Furtherfield’s Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival exhibition Maria Dada, Miranda Hall and Cassie Thornton will be taking over the social media channels on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. Each micro-commission is an online space to take in different directions related ideas and themes of #playbour.

Our first week kicks off with Maria. Researcher in the fields of design and material culture, Dada’s Confessional Viral Hoax Engine brings together an interest in the infrastructures and processes used to spread misinformation online with themes of transparency, anxiety, and virtue signalling.

The second week is headed by Miranda Hall, who is a freelance journalist and research assistant at SOAS specialising in digital labour.

In the final week Cassie Thornton, artist, activist and feminist economist, will take-over Furtherfield’s social media channels. You can learn more about her here and her new project being launched on Kickstarter. Her take-over explores ideas surrounding yoga, feminist economics, class war, collective revenge, and social technology.

Dani Admiss is an independent curator and researcher working across art, design, and networked cultures. Her work employs world-building and co-creation to explore changes happening to our social, technological, and ecological, contexts. She is particularly interested in working with others to understand not yet completed transformations of body, society, and earth, into global capitalist systems. She is Founder of Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival, an art and research platform dedicated to the study of the worker in an age of data technologies. daniadmiss.com

Furtherfield is an internationally renowned arts organisation specialising in labs, exhibitions and debate for increased, diverse participation with emerging technologies. At Furtherfield Gallery and Furtherfield Lab in London’s Finsbury Park, we engage more people with digital creativity, reaching across barriers through unique collaborations with international networks of artists, researchers and partners. Through art Furtherfield seeks new imaginative responses as digital culture changes the world and the way we live.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information

This project would not have been possible without the kind support of our partners.

This project has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Playbour: Work, Pleasure, Survival, is realized in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo More (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY).