Curated by Rosa Menkman & Furtherfield.

Opening Event: Saturday 8 June 2013, 2-5pm

with Glitch Performance by Antonio Roberts at 3pm

Open Friday to Sunday 11-5pmContact: info@furtherfield.org

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

IMAGES OF THE OPENING ON FLICKR

READ Glitch as a Symbolic Art Form BY ROB MYERS

WATCH VIDEO OF THE OPENING

“The glitch makes the computer itself suddenly appear unconventionally deep, in contrast to the more banal, predictable surface-level behaviours of ‘normal’ machines and systems. In this way, glitches announce a crazy and dangerous kind of moment(um) instantiated and dictated by the machine itself.” Rosa Menkman [1]

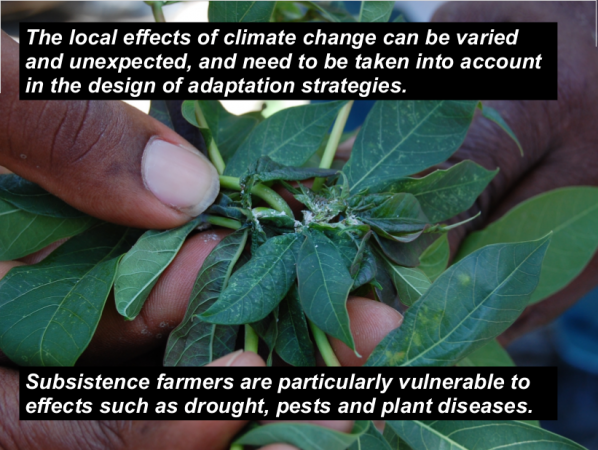

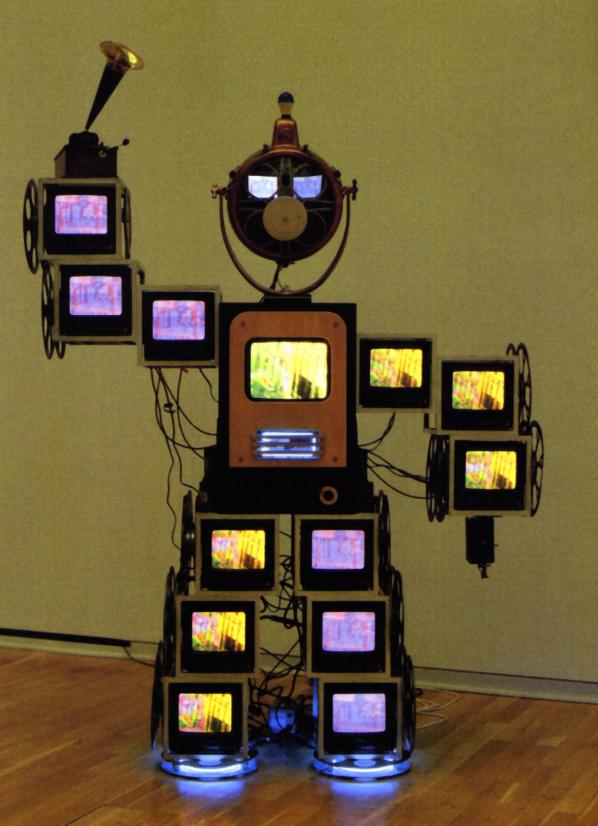

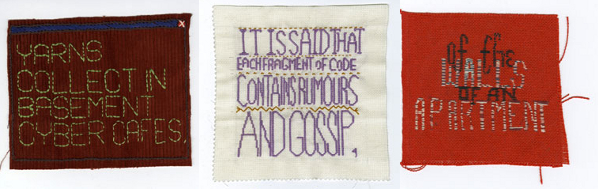

Glitches are commonly understood as malfunctions, bugs or sudden disruptions to the normal running of machine hardware and computer networks. Artists have been tweaking these technologies to deliberately produce glitches that generate new meanings and forms. The high-speed networks of creation and distribution across the Internet have provided the perfect compost to feed this international craze. The exhibition shows various approaches by artists hacking familiar hardware and their devices which include mobile phones, and kindles. They disrupt both the softwares and the digital artefacts produced by these softwares, whether it be in the form of video, sound and woven glitch textiles.

Glitch art subverts the way in which we are supposed to relate to technology, causing playful, imaginative disruptions. It is a low-tech and dirty media approach with a punk attitude. These artists appropriate the medium and forge expressions that go beyond what the mainstream art world expects artists to do, it is unstoppable – it is Glitch Moment/ums.

Copies of Rosa Menkman’s groundbreaking Glitch Art critique The Glitch Moment(um) will be available for purchase during the exhibition.

![numbermunchers from the untitled [screencaptures] series by Melissa Barron](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/melissabarton.jpg)

Empty Spinning Circle become Full (part b) (2012) from the Further Abstract series by Alma Alloro

One Square in colors (2012) from the Further Abstract series by Alma Alloro

untitled [screencaptures] (2010) by Melissa Barron

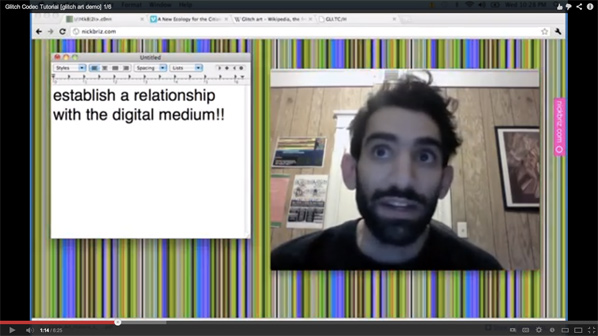

The Glitch Codec Tutorial by Nick Briz

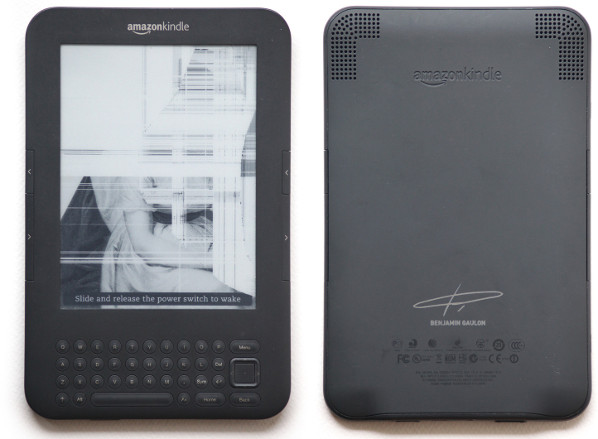

KindleGlitched (2012) by Benjamin Gaulon

Thoreau Glitch Portrait (2011) by José Irion Neto

Copyright Atrophy (2013) by Antonio Roberts

What Revolution? (2011) by Antonio Roberts

Beyond Yes and No (2013) by Ant Scott

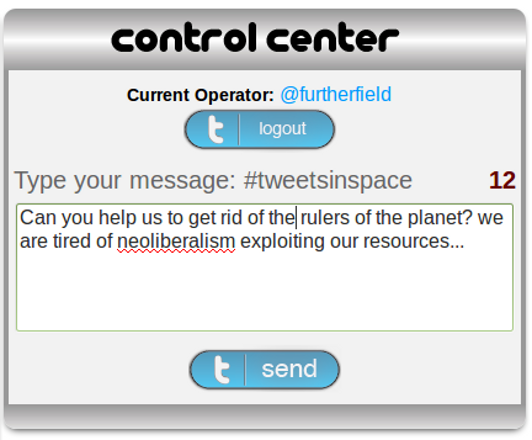

Glitch artists and enthusiasts are invited to add their work to GLI.TC/H 0p3nr3p0.net, a Glitch Art repository coded by and developed by Joseph ‘Yølk’ Chiocchi & Nick Briz. The submissions will be showcased during Glitch Moment/ums at Furtherfield Gallery. To include your work in the 0P3NR3P0 component of Glitch Moment/ums submit a link to any visually wwweb based file (html, jpg, gif, youtube, vimeo, etc.) and your piece will automatically be included in the line-up (one work per artist).

This new IRL exhibition has been organised in collaboration with Nick Briz and Joseph ‘Yølk’ Chiocchi.

SUBMIT && SHOW on 0P3NR3P0.NET.

Alma Alloro

Alma Alloro (IL) is an artist, musician and performer from Tel Aviv. She is rooted in the backyard of popular culture using diversified media from drawing, installation, music, and animation to internet; her recent works focus on the correlation between old media and new media.

Melissa Barron

Melissa Barron is an artist living and working in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where she focused on new media and fiber. In her work she combines these two fields by reinterpreting hacked Apple 2 software through different fiber techniques. Her work has been shown at various international events, including the Notacon hack festival in Cleveland, Ohio, GLI.TC/H in Chicago and ISEA 2011 in Instabul.

Nick Briz

Nick Briz is a newmedia artist, educator and organiser based in Chicago IL. His work has been shown internationally at festivals and institutions, including the FILE Media Arts Festival (Rio de Janeiro, BR); Miami Art Basel; the Images Festival (Toronto, CA) and the Museum of Moving Image (NYC). He has lectured and organized events at numerous institutions including STEIM (Amsterdam, NL), the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Marwen Foundation and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His work is distributed through Video Out Distribution (Vancouver, CA) as well as openly and freely on the web.

Benjamin Gaulon

Benjamin Gaulon is an artist, researcher and art college lecturer. He has previously released work under the name “Recyclism”. His research focuses on the limits and failures of information and communication technologies; planned obsolescence, consumerism and disposable society; ownership and privacy; through the exploration of détournement, hacking and recycling. His projects can be softwares, installations, pieces of hardware, web based projects, interactive works and are, when applicable, open source.

José Irion Neto

José Irion Neto is native of Santa Maria, in southern Brazil. His first contact with computers was in 1982 using a machine equivalent to Sinclair ZX Spectrum. He has an academic background in Media Advertising and worked for some years as a Graphic Designer. Today, he has been working with advertising only occasionally, focusing on creating posters, dedicating most of his time on developing Glitch Art. He has worked and researched Glitch since 2008.

Antonio Roberts

Antonio Roberts is a British digital artist whose artwork focuses on the errors and glitches generated by digital technology. Many people would simply discard such artefacts but Antonio preserves these errors and displays them as art. With his roots in free culture he develops his techniques using open source and freely available software and shares his knowledge through the development of software.

Ant Scott

Ant Scott (UK) is a glitch artist and co-author of the first glitch aesthetics coffee table book Glitch: Designing Imperfection (New York: MBP, 2009). His work is informed by cognitive distortions.

Rosa Menkman

Rosa Menkman is a Dutch visualist who focuses on visual artifacts created by accidents in digital media. The visuals she makes are the result of glitches, compressions, feedback and other forms of noise. By combining both her practical as well as an academic background, she merges her abstract pieces within a grand theory artifacts (a glitch studies), in which she strives for new forms of conceptual synthesis of the two. In 2011 Rosa wrote Glitch Moment/um, a notebook on the exploitation and popularization of glitch artifacts (published by the Institute of Network Cultures), organized the GLI.TC/H festivals in both Chicago and Amsterdam and co-curated the Aesthetics Symposium of Transmediale 2012.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

MOVABLE BORDERS: THE REPOSITION MATRIX workshop

organised by Dave Young

Saturday 18 May 2013, 1-5pm

BOOKING ESSENTIAL. Please register with Alessandra.

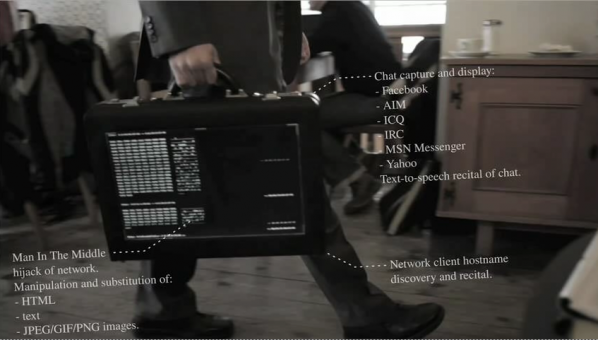

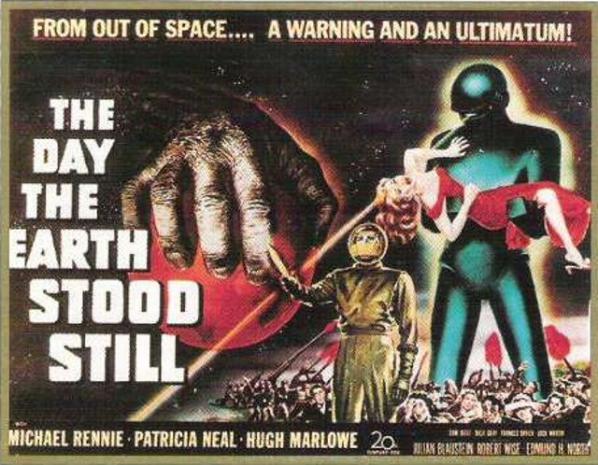

The devices that once populated the creepy dystopian futures of science fiction have broken through into our daily reality.

Drones of dozens of different types are becoming a part of everyday life. They scout our public (and private) spaces, carrying out surveillance or reconnaissance in the service of nation states and as unmanned robotic tools, armed with missiles and bombs, acting in defence of “national security”.

According to a European commission document drones will be commonplace in the skies within a decade. There are already many companies building these airborne, robotic spies for military and police use and this has “prompted concerns from civil liberties groups, who fear that the unmanned aircraft will result in more forms of surveillance.” [1]

During the three weeks of Movable Borders: Here Come the Drones! people are invited to view artworks and join a workshop by artists who are contemplating how drones are changing the way we see and relate to each other and the world around us.

Artworks and projects by Bureau of Inverse Technology (US & AU), Lawrence Bird (US), Patrick Lichty (US), Dave Miller & Gavin Stewart (UK), The Force of Freedom (NL) and Dave Young (NL).

Bit Plane by Bureau of Inverse Technology (Natalie Jeremijenko and Kate Rich) is an early artistic reflection on the relation between technology and surveillance and, as such it can be seen as a precursor to the emerging DIY surveillance video enabled by the new availability of drones. The bit plane is a radio-controlled model airplane, designed by the Bureau and equipped with a micro-video camera and transmitter. In 1997 it was launched on a series of sorties over the Silicon Valley to capture an aerial rendering. Guided by the live control-view video feed from

the plane, the pilot on the ground was able to steer the unit deep into the glittering heartlands of the Information Age.

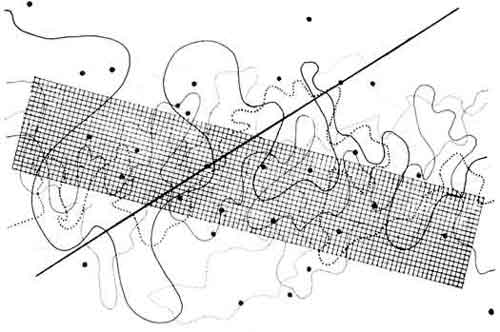

Parallel by Lawrence Bird uses Google Earth to track the 49th parallel, i.e. the prairie border between Canada and the United States. The digital projection invites open interpretations: it is a film about parallel countries; parallel modes of imaging and imagining; parallels between political, technical and visual territories. Obvious digital anomalies in the video, caused by satellite interference, allow for further speculation and imaginative readings.

The Private Life of a Drone by Patrick Lichty is a video travelogue recorded by flying video drones, exploring the area surrounding the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts in Amherst, Virginia (US).

Lines by Dave Miller and Gavin Stewart draws on an emergent cultural interest in drones to explore related issues around privacy, mediation, power, security, morality, legality and others in all aspects of contemporary life. Lines aims to encourage and affect public debate.

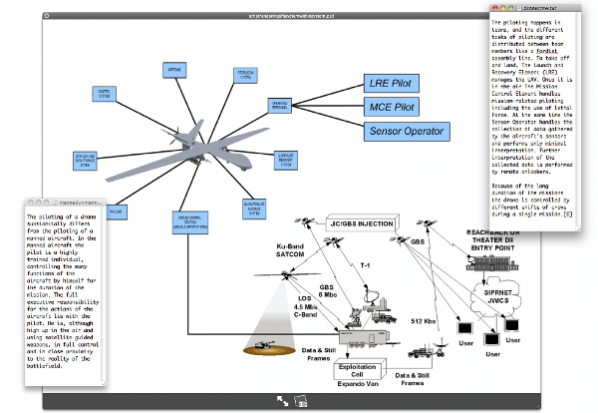

TELEWAR is a book and video collaboration between Dave Young and The Force Of Freedom collective. The project tries to make some sense of the uses, effects and developments of the new warfare technologies, like military drones, through the analysis of news reports, military drone culture, drone speak and network theory.

Movable Borders – The Reposition Matrix by Dave Young provides the central installation and information resource of the exhibition.

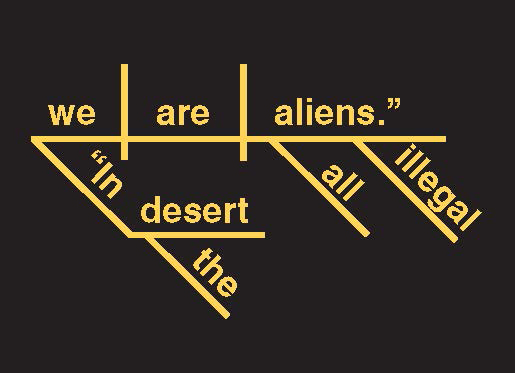

In a post-national age, where “territorial and political boundaries are increasingly permeable”[2], what has become of the borderline? How is it defined, and what technologies are used to control it?

Movable Borders is an ongoing research project that begins to explore possible answers to these questions through facilitating discussions around the ‘reterritorialisation’ of the borderline in the information age.

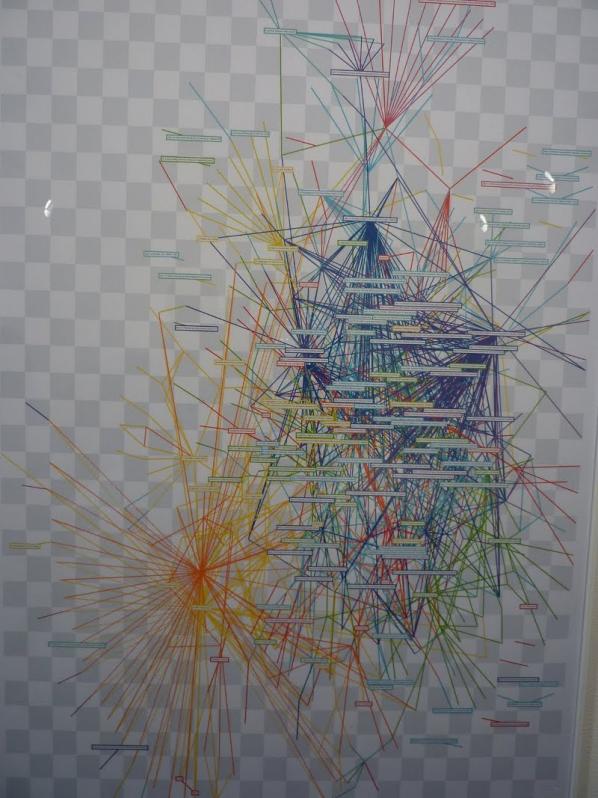

The Reposition Matrix aims to reterritorialise the drone as a physical, industrially-produced technology of war through the creation of an open-access database: a ‘reposition matrix’ that geopolitically situates the organisations, locations, and trading networks that play a role in the production of military drone technologies.

Alongside the installation Dave Young will be holding a workshop on the subject of drones on Saturday 18 May, 1-5pm – BOOKING ESSENTIAL. More info here.

Lawrence Bird

Lawrence Bird is a designer, instructor and writer with an interest in cities and their image. He has trained in architecture (B.Arch), social sciences and urban design (MSc), and history and theory of architecture (PhD). He has recently completed the SSHRC-funded postdoctoral project Beyond the Desert of the Real, based in Winnipeg, Canada. The project focused on desolate urban sites, elicited visual narratives from city residents and graduate students of architecture in response to them, experimented with representations of the city based on these narratives, and used these strategies as points of departure for urban design and urban landscape proposals. Lawrence also makes films, and is currently developing a hybrid film and animation project WPG_POV.

Bureau of Inverse Technology

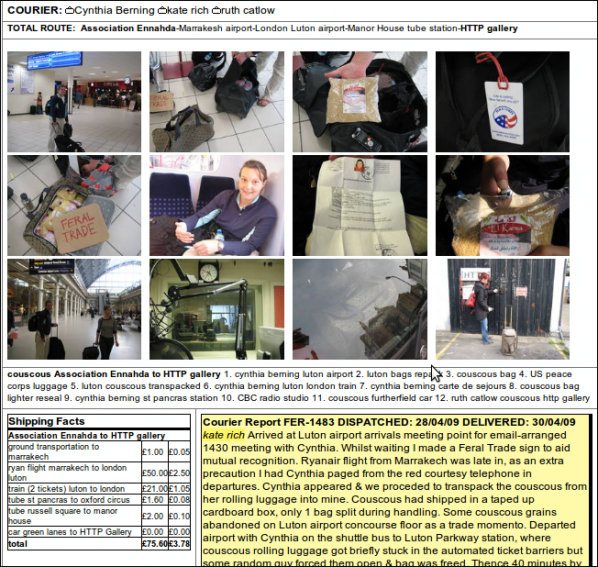

The Bureau of Inverse Technology (aka BIT) is an organisation of artist-engineers whose stated aim is to be an information agency servicing the “Information Age”. Bureau engineers are involved from design to deployment and documentation of radical products based on commercially available electronic entertainment components such as cameras, radios, networks, robots, sensors, etc. Though its work has long been publicly available, the composition of the Bureau itself is shrouded in some mystery, for some years cloaking its identity in anonymity. In 2004 the Bureau initiated a “retreat from anonymity” when radio journalist and BIT co-founder Kate Rich took up a three month Research Fellowship at Piet Zwart Institute for Media Design Research, Rotterdam in 2004. Current Bureau products include BIT Radio, Feral Robotic Dogs and the Despondency Index.

Patrick Lichty

is a technologically-based conceptual artist, writer, independent curator, animator for the activist group The Yes Men, and Executive Editor of Intelligent Agent Magazine. He began showing technological media art in 1989, and deals with works and writing that explore the social relations between us and media. Venues in which Lichty has been involved with solo and collaborative works include the Whitney & Turin Biennials, Maribor Triennial, Performa Performance Biennial, Ars Electronica, and the International Symposium on the Electronic Arts (ISEA). Patrick also works extensively with virtual worlds, including Second Life, and his work, both solo and with his performance art group Second Front, has been featured in Flash Art, Eikon Milan and ArtNews. He is also an Assistant Professor of Interactive Arts & Media at Columbia College Chicago, and resides in Baton Rouge, LA.

Dave Miller

Dave Miller is a South London based artist and currently a Research Fellow in Augmented Reality at the University of Bedfordshire. Through his art practice Dave draws out the invisible forces that make life difficult. His work is about caring and being angry as an artist. His art enables him to express feelings about the world, to attempt to explain things in a meaningful, yet subjective way, and make complex information accessible. Recurrent themes in his work are: human stories, injustices, contentious issues and campaigning. Recently he has been very bothered by the financial crisis.

Gavin Stewart

Gavin Stewart is Lecturer in Digital Media at the University of Bedfordshire, poet and writer. He is the current convener of the Interactive Media Group. His research interests are the aesthetics of digital texts and the impact of corporate digital media on our understanding of community. Gavin is course leader in BA Media Production and currently teaches units in Media and Cyberculture and Print, Culture and Technology at MA Level. Gavin is is also the co-organiser of the Playful Paradox mini-festival, the End of Journalism conference and the Under the Mask: Perspective on the Gamer conference series.

The Force Of Freedom

The Force Of Freedom is a Rotterdam based collective founded by Micha Prinsen and Roel Roscam Abbing in 2009. In their work they react critically but playfully to new emerging technologies and developments on the internet.

Dave Young

Dave Young is an artist, musician and researcher currently studying the Networked Media course at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam (NL). His research deals with the Cold War history of networked culture, exploring the emergence of cybernetic theory as an ideology of the information age and the influence of military technologies on popular culture.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

Featured image: Five Thousand Feet is the Best by Omer Fast.

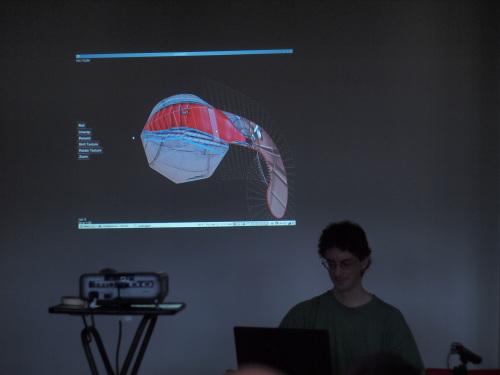

In perusing Honor Harger’s recent missive on drone aesthetics and James Bridle’s ongoing posts of drone images at Dronestagram, taken in context with the Glitch un-conference in Chicago, some new questions have come to mind. These questions have to do with conceptions of New Aesthetics in its various forms in terms of interaction with the program/device and its level of autonomy from the user. In my mind, there seems to be a NA continuum from generative programs that operate under the strict criteria of the programmer to the often-autonomous actions of drones and planetary rovers. As you can see, I am still chewing on the idea that The New Aesthetic as it seems to be defined, as encompassing all semi-autonomous aspects of ‘computer vision’. This includes Glitch, Algorism, Drone imagery, satellite photography and face recognition, and it’s sometimes a tough nugget to swallow that resonates with me on a number of levels.

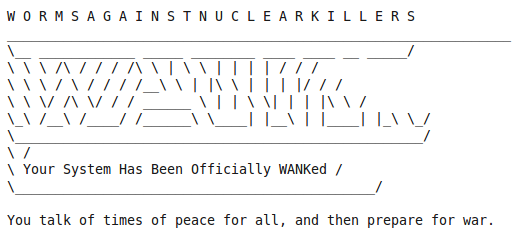

First, image-creating technological agents are far from new, as Darko Fritz recently stated in a talk that algorithms have been creating images, in my opinion, within criteria of NA since the 60’s, and pioneers like Frieder Nake, A. Michael Noll, and Roman Verostko have been exploring algorithmic agency for decades. If we take these computer art pioneers into account, one can argue that NA has existed since the 60’s if one lumps in genres like Verostko’s ‘style’ of Algorism or the use of algorithms as aesthetic choice. A notch along the continuum toward the ‘fire and forget’ imaging (e.g. drones) is the Glitch contingent, which is less deterministic about their methodologies of data corruption aesthetics by either running a program that corrupts the media or they perform digital vivisection and watch what little monster they’ve created. Glitchers exhibit less control over their processes, and are much more akin to John Cage, Dada or Fluxus artists in their allowance of whimsical or chance elements in their media.

However, as we slide along the spectrum of control/autonomy from the lockstep control of code to the less deterministic aesthetics of face recognition, drone imaging, robotic cameras, Google Street View cams, Mars Rovers and satellite imaging, things get murkier. Autonomic aesthetics remind me of the ruby-hued Terminator T500 vision generated by intelligent agents running the ‘housekeeping’ on the machine platform. I consider this continuum from Algorism to Glitch to autonomous robotic agents under an NA continuum of aesthetics is important insofar as it defines a balance of agency between the operator and the ‘tool’. For me this is the difference between the high degree of control of the Algorist, the ‘twiddle and tweak’ sensibility of the Glitcher, and the gleaning from the database of pseudo-autonomous images created by Big Imaging created by drones and automatic imaging. Notice I use the term ‘pseudo’ in that there are operators flying the platforms or driving the car, while the on-board agents take care of issues like pattern/face recognition and target acquisition. We also see this in Facebook, as recent technological changes as of 2012 have introduced face recognition in the tagging of images. From this, a key issue for me in this discussion of what began as a nebulous set of terms (the criteria of NA as defined by the global conversation) is that of agency and autonomy, and how much control the New Aestheticist gets in the execution of their process. Another important point is that I am not calling the ‘New Aestheticist’ an artist or curator, but something in between, but I’ll get to that later as this is also an issue of control of intent.

Back to this idea of autonomy between the subject, the ‘curator’ and the viewer, what interests me is the degree of control or not that the person creating, tweaking, or gleaning the image has over the creation or contextualization of that image. In the case of the Algorist, this is the Control end of the spectrum, where the artist takes nearly full control of the process of creation of the image, unless there is a randomization function involved in the process, and that it itself is a form of control – very Cybernetic in nature. Agency is at a maximum here, as the artist and machine are in partnership. Roman Verostko is a prime example of this, as he explores intricate recursive images created by ink pen plotters using paints in the pens. What he, and the AI-driven AARON, by Harold Cohen, for that matter, are machine painting.

The next step down the autonomy spectrum would involve the use of ‘glitch’ tools and processes that distort, disturb, and warp digital media. The process involves executing a given intervention upon the medium, such as saving it improperly, hex editing its code to corrupt it, or as Caleb Kelly writes, ‘crack’ the media. There are differing degrees of disturbance of the media to inject chance processes into it, from a more ‘algoristic’/programmatic application of programs upon the media to directly changing the internal data structure through manipulating the information through hex code and text editors. The resultant process is an iterative ‘tweak and test’ methodology that still involves the user in the process to varying degrees. Of course, the direct manipulation of the data with a hex editor is the most intimate of the processes, but there is still one factor to account for. The factor in question is that there is the set of causes and effects that are set in motion when the artist/operator opens the media and the codec (Compressor/DECompressor) mis/interprets the media, as is intended by the artist.

If we are to look at the glitch process, we can say that there is a point of intervention/disturbance upon the media, which is entirely a function of control on the part of the user. Afterwards, it is set loose into the system to allow the corruptions within the media to trigger chance/autonomous operations in its interpretation in the browser, etc. This is where the glitcher straddles the line between control and autonomy, as they manually insert noise into their media (control), then the codecs struggle with the ‘cracked’ media (autonomy). The glitcher, then, has the option to try a new iteration, thereby making the process cybernetic in nature. In Glitch, there is a conversation between the operator, the media and the codec. With the aesthetics created by drones, algorithmic recognition software, and satellite reconstructions, the process is far more autonomous/disjoint, and the New Aestheticist has to deal with this in the construction of their practice.

In the genre that I will call ‘mobEYEle’ imaging, the robot, satellite, or parabolic street eye abstracts from the ‘artist’, aptly turning them into an ‘aestheticist’, as their level of control is defined as that of a gleaner/pattern recognizer from the image bank of Big Data. Rhetorically speaking, we could say that a connection between the aestheticist and the generator of the image would be less abstract if, say, a New Aestheticist were to be in the room with a drone pilot, conversing about points of interest. It is likely that a military remote pilot and a graphic designer would have sharply differing views as to what constitutes a ‘target of interest’. Like that’s going to happen…

Therefore, let us just say that the collaboration of a New Aestheticist and a drone pilot is nightly unlikely, and that the New Aestheticist is therefore abstracted from the decisions of command and control involved in acquiring the image that eventually gets in their hands. This, however, presents us with two levels of autonomous agency, one human and one algotrithmic. But before I expand on this, I would like to discuss my decision to call the practitioner an ‘aestheticist’ as opposed to an artist or curator.

This decision rests on what I feel is the function of the aestheticist, that is, to glean value from an image and ‘ascribe’ an aesthetic to it. This position puts them in a murky locus between artist and curator, as they have elements of neither and both. For example, does the drone-image NA practitioner create the image; are they the artist per se, of the image? No. Although they are more closely aligned to curatorial practice as they collect, filter (to paraphrase Anne-Marie Schleiner), and post on tumblrs and Pinterests? From my perspective, the role of a curator is the suggestion of taste through and informed subjectivity through ecologies of trust and legitimacy, but the social image aggregator, although they might want to perform the same function, has no guarantee of accomplishing this unless they develop a following. Therefore, under my definition, they are neither creators nor taste-makers in the traditional sense, so what makes sense is to call them ‘aggregators’ of aesthetic material and thus my term ‘Aestheticist’.

Returning to our conversation, the drone aestheticist, then, is subject to one of two degrees of completely abstracted autonomy of the creation of the image; that of the operator or that of the algorithms operating the drone. The abstraction surrounding the human operator is easiest to resolve, as the images of interest are either the preference of the drone operator or those created by the operator under the parameters of the mission, and not the results of a New Aestheticist’s joyride on a Global Hawk. It is merely someone else’s volition selecting the image, and a confluence of personal interest deciding as to whether the image deserves to be on the New Aestheticist’s social imaging organ. However, it is the drone’s algorithmic image acquisition system that creates a more alien perspective in regards to aesthetics and autonomy of the image.

Compared to the Algorist or the Glitcher, all loosely placed under the banner of New Aesthetics, the Drone/Big Data Aestheticist is most problematic, as they are a fetishizer of sheer command and control operations that are potentially utterly abstracted from the pilot/driver’s volition. This creates a double abstraction through first the pilot, and then the algorithmic recognition system. There is no cybernetic loop here at all, as the gleaning of the item of interest from the beach of Big Data is twice removed from any feedback potential. Secondly, as I have written before, the Drone Aestheticist is exactly that, a gleaner of interesting images for use on their social image site, which in itself is a bit of an abject exercise.

Or is it? For example, if one is to say that the Aestheticist gleaning the images does so without intent or politics, and is merely operating on fetish/interest value, then this is perhaps one of the least interesting practices in New Aesthetic practice. But on the other hand, if one looks at the work of practitioners like Jordan Crandall, Trevor Paglen, or Ricardo Dominguez, who examine the acquired image as instrument of aggression, control, and oppression, this puts a new lease on the life of the Drone Aesthetic. In a way, though inquiry, there is an indirect feedback loop established in questioning the gaze of the device, its presence, and its function in its theater of operations. The politics of the New Aesthetic emerges here, in asking what mechanisms of command and control guide the machine eye and determine its targets of interest. This is of utmost importance, as the abstracted eye is guided without subjectivity or ethics and is determined solely by the parameters of its algorithms and the stated goals of its functions.

Is the aesthetic of the machine image merely a function of examining its processes, fetishizing its errors, or something else? The criteria of the New Aesthetic attempts to talk about a spectrum of digital imaging that stretches back into time far longer than 2010, and has a problematically broad sense of definition. Once these problems are set aside as a given, one of the key criteria for the evaluation of NA practice and the function of its images depends upon the degree of control and autonomy inherent in the process within the creation of the image. This is formed in a continuum of control and abstraction from Algorism and Generative Art to autonomous eyes like drones and satellites. Algorism is one of the oldest NA practices, and exhibits the closest relationship between artist, machine and determinacy of digital process. A greater degree of indeterminacy is evident in the Glitch, but the iterative process of tweaking the media and then setting it forth into the process of interpretation by the codec, foregrounds the issue of digital autonomy.

The eye of the unmanned platform abstracts creation from the human organism at least once if a human does not operate it remotely, and twice if it is. There is the Terminator-like fear of the autonomous robot, but at this time, perhaps the more salient questions regarding what I have qualified as drone/autonomous aestheticism under NA of what the function of the image is, and is it really that interesting? Are the practices of NA blurring artistic and curatorial practice into a conceptual aestheticism, creating a cool detachment from the image despite its source or method of creation? Is the bottom line to the genres of NA the degree of control that the artist or aestheticist has over the image’s creation or its modality/intent? It seems that NA is an ongoing reflection upon the continuum of control over the generation of the image, our beliefs regarding its aesthetics, and what the intentions or politics are behind the creation of the New Aesthetic image. Or, as I have written before, are we just pinning images from Big Data and saying, “Isn’t that kinda cool?”

Maybe it’s somewhere in the middle of intention and cool.

Featured image: Journey to Ard al Amal (The Land of Hope). Screenshot box & video installation. Impakt festival & exhibition. Image Pieter Kers

Foundland, Ghalia Elsrakbi (SY) and Lauren Alexander (SA), is a multi-disciplinary art and design practice based in Amsterdam. With backgrounds in graphic design, art and writing Foundland’s approach focuses on research based, critical responses to current issues. While moving around in advertising, printed matter, the Internet, and off line art spaces they dig up interesting stories about Disney, SpongeBob and defected soldiers.

Annet Dekker: Where does the name Foundland come from, or what does it mean?

Lauren Alexander: We started working together in 2009 and at the time we had worked on a project about being stateless, so Foundland seemed fitting. It is quite literally a way of thinking about how to found a land and to create a space that we could use as a platform for thinking about ideas with some kind of visual output. For us, space is related to political scenarios, and also to something virtual, online, all these different places that we inhabit.

Ghalia Elsrakbi: Foundland relates also to finding and discovering something new, looking behind something. We are very interested in speculation, we speculate about images and their meaning, in order to find something unexpected.

AD: What is your focus, what are you trying to find and tell?

LA: We want to tell stories in new ways, because by telling a story in a different way, especially related to subjects which are often seen in the media, you are offering an alternative perspective.

GE: The exhibition we just did for Impakt festival is a good example. With the installation Journey to Ard al Amal (The Land of Hope) we speculated how popular characters and animations, dubbed from Japanese to Arabic, or adapted from Walt Disney, play a valuable role in imagining heroes and villains. We were looking at a history of cartoons. This isn’t obviously political, but when seeing how cartoons are used in Syria and other places, interesting issues came up and we constructed a story that reflected on the current situation. We looked for connections between the way people see cartoon characters now and how they are embedded in childhood memories. In the end what we present is a kind of imagined picture of how things could be, maybe as an alternative to watching the news.

AD: Can you elaborate a bit, what images did you see and how did you (re)use them?

LA: In the installation we focused on this specific case study of the apocalypse scenario which is sketched in a cartoon series called Adnan and Leena in Arabic. In an earlier research essay Simba, the last Prince of Ba’ath country, we extracted images and characters from Arabic websites and speculate on appropriation by showing original images, before they were photoshopped. In a talk we did, we were also drawing connections to the way that Western cartoon characters are suddenly popping up in news footage, and how activists use cartoon identities on the Internet.

GE: Currently there is a full swing of the way Western stories are adapted. For example images of Mickey Mouse or SpongeBob are painted on walls in Syria. In the talk we question whether it is still Mickey Mouse that we see, the one that we remember from our children books, or if it means something else? We compared and related these images to the way such iconography is appropriated and used by both activists and ruling parties. The reuse of symbols and images and how sometimes historical moments are turned into something completely different is very interesting. Such findings are what we are really focusing on.

AD: There is also a long and popular tradition of autonomous animation in middle east, how does that relate to what you’ve been researching?

LA: Cartoons are very differently perceived in Syria, and also in South Africa, unlike in the Netherlands, they pose a huge threat to those in charge. For example the government is continuously suing political cartoonists like Ali Farzat in Syria and Zapiro in South Africa because their cartoons undermine existing power structures.

GE: There are indeed many artists who create political cartoons or satirical statements but with these Disney cartoons it was about finding the hidden story of an image. We recognise the cartoons from a Western perspective and the local one. By making connections and telling a different story we want to give a different perspective and a better understanding of what is really happening. Actually I grew up with Japanese Manga, but today Disney is everywhere. This is also political because in the time that Hafez Al-Assad was running Syria there was no American culture at all, when he died his son opened the country a bit for the Western market and you started to see American programmes. Nevertheless, everything is dubbed to Arabic so children don’t necessarily view it as an American production because it speaks their own language and sometimes stories and words are changed in order to better relate to Arabic countries.

LA: The connection to America is not obvious, what we found is that characters like SpongeBob and Mickey Mouse are simply friendly characters. They are your buddy, they help and like you.

GE: That is why they are used in this process of freedom fighting. ‘Your friends’ carrying the freedom flag and are used to create a kind of identification with the message that they want you to see. I mean, it is difficult to hate or not to trust these images because they are icons of friendliness. Whereas the image of a politician or some other hero who is telling a personal story can easily be damaged, a cartoon image is unbreakable. It appeals to children involved in the revolution. So, these images consist of many layers and bring up interesting questions. We aren’t looking for the true answer, because in the end we create our own story.

AD: Could you speak of a sort of universal populism or at least a continuing iconography?

GE: There are many different images, from the Lion and the Father and the Son, to things you see in public space, or images that people grew up with. These are all reused in a digital form and become part of the revolution. People tend to think of them as new images, but when you compare them to older ones, the original, it reflects very much the ideology of the regime. By putting them in a different context we try to force people to question the images and the stories.

LA: I remember that I was in South Africa when we were working on the fiction interview with a propaganda makers text and I had asked my mother to read it. She commented that ‘This is what the government used to say during apartheid, I recognize this’. I guess this shows quite a universal context. We are so used to advertisement and iconography that we don’t question it and tend to ignore the meaning.

GE: Yes, it’s not so different at all, propaganda still uses the same techniques, they have not changed and people fall for it. I think it’s very good to expose propaganda makers.

AD: What new context are you giving it?

LA: Up till now our work has been presented in a western context within the framework of festivals or art spaces.

GE: We wanted to show it to a Western audience, but now we also want to see how it will work when we go to Syria or the Middle East. This will be a challenge because we need to find a way to make that translation back again. We tried already a few times to publish texts for example, but the expectation is very different, stories are more direct and literal, you say exactly what you mean, not the way that we do it here which is reading between the lines.

AD: Is that also why you work in so many ways, from installations, to print, to presentation, to video?

LA: Yes, a lot of this is about experimentation with how things work. We often start from something that we have found online. We find a lot of information, which can be confusing, and then it is about finding the right moment, time and place to present it. Giving it all your attention to dig into an issue, know more and tell more.

GE: Each time we try to define the best way to present what we want to say. It is interesting to open and use the whole research process, it is not just about an end result that is presented. For example, now we are collecting a lot of defection movies from soldiers who are leaving the official army Syrian and joining the free army. What we notice is that the visibility of this free army is that it is only online, on YouTube. We are interested in how an identity of an army that exists on the ground and performs all kinds of operations, primarily takes place on YouTube. The videos of the defectors are almost like a physical performance of defection. We want to collect the story of it, to help people appreciate this image, why it was made, and think about what this means for us.

AD: Digging up memories and confronting people?

GE: When we started the cartoon project we noticed that people were hiding their identity online behind popular cartoon masks. It was really about how people used the Internet.

LA: We discovered that using the Internet is not always about the technical functions of connectivity, distribution, uploading and liking.

GE: If you look for example at how Syrians use the Internet, it’s really for emotional support. A few months ago there was no Internet in the whole of Syria, which was emotionally a big thing because people abroad couldn’t connect to people online and read their contributions. The revolution is nothing without these contacts. All of a sudden a Facebook campaign started called ‘Here is Damascus’. At first I didn’t understand it, but it turned out to be a reference to an event that happened in the 60’s in Cairo, while at war with Israel, the radios were cut off and there was no communication in the city. At that point the city of Damascus changed the name of their radio to ‘Cairo radio’. A political statement, like a re-enactment, happened now on Facebook. The Internet has all these different kinds of layers, of reflecting on history and bringing events to life.

See more Foundland work and updates at www.foundland.info

Featured image: Image from Fab Lab (fabrication laboratory), small-scale workshop offering digital fabrication

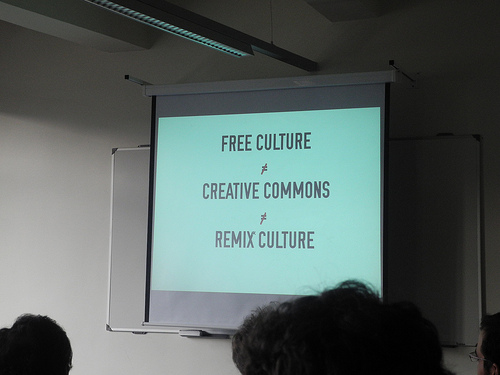

There is currently a significant amount of interest in the relationship between free and Open Source practices in art and the aim of this report is to map out some of these shifting relationships in contemporary models of education both online and offline. The recent expansion of so-called ‘free culture’ has contributed to placing the debate over authorship, ownership and licensing of the artwork at the centre of artistic production. Crucially, the transformation of art in the age of global culture and the consequent move from autonomous art objects into cultural artworks and services, has resulted in the emergence of three visible tendencies: 1) free/Open/Source software as artistic-pedagogical method, 2) the critical emancipation of the self-education movement and 3) the digitisation of art education practices into Open Source packages of cognitive labour.

One possible way to navigate this complex ideological terrain is the conciliatory term free/libre/Open Source software (floss), seeing it as “part of an emerging transdisciplinary field that deals with different forms of openness.” [1] At the heart of the debate is the political distinction between the Free Software Foundation[2] and the Open Source Initiative.[3] The ‘copyleft’ attitude (free software movement) asserts four freedoms for software: free from restriction, free to share and copy, free to learn and adapt, free to work with others.[4] The Open Source definition,[5] on the other hand, in spite of apparent similarities, has developed into flexible arrangements such as the Creative Commons licenses[vi][6], some of which restrict these freedoms when applied to media/cultural works and publications, not allowing for derivative artwork or its commercial use under specific license combinations.[7]

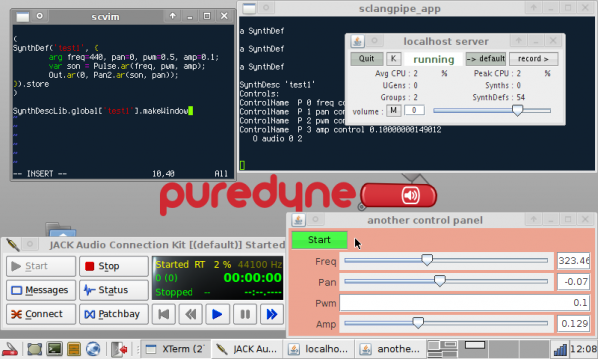

A number of projects, such as the pure:dyne[8] – GNU/Linux operating system for live audio visual processing and teaching – are, however, fully identified with the principles of free software. They have emerged from artists’ collectives whose relationship to art education is informally associated with sharing spaces, the hacklabs and free media labs where they run workshops and introduce participants to the use of free digital art tools. [9] Their mode of production is centred on ‘live code’ and feature two essential characteristics: 1) collaborative- relying on large-scale public participation and 2) distributive- offering the tools and the process notes (notation) to empower the others to carry on the work on their own.[10] This philosophy implies that the artistic performance of the work is complemented by a set of pedagogical approaches associated with the enabling of production by others. [11]

The movement for free education has gained greater relevance as a result of the global financial crisis and the battle for control of university fees.[12] In this context, art education has been developing into an artistic project while also providing an emancipatory movement reacting against dominant forms of institutionalised knowledge production. Within this movement, the role of free/open technology has been central in the mediation of self-education as a social movement.

On the one hand, artists –freelancers, sometimes temporarily/precariously plugged into educational institutions whilst working as teachers, others times as workshop facilitators in free access spaces– have opened up their classrooms to the environment of the read/write web, and with their students-collaborators, have produced and shared in wikis, blogs and Second Life, art and education resources that make an increasingly significant contribution to a larger body of knowledge that is the web. [13] Wikiversity is a model of this confluence of self-education movements and open online education.[14]

In parallel with the above-mentioned tendencies of online systems, numerous critical projects have appeared that are associated with the reclamation of space that occurs as artists have found themselves at the forefront of self-organised and self-managed self-education projects.[15] Some have happened side-by-side with the reclamation and occupation of spaces such as the Temporary School of Thought[16] and the Really Free School.[17] Part of these groups activity is the establishment of a free programme of workshops on topics that can range from free software tools to Ivan Illich and Deschooling Society.[18] Others that make opportunistic incursions into the artworld such as the Bruce High Quality Foundation University,[19] the Future Academy[20] or Unitednationsplaza,[21] are platforms for experimental art as research, investigating the production of knowledge that occurs when art education itself becomes artwork or exhibition.[22]

While the debate on free education has been enjoying significant visibility, the Higher Education sector has also joined in. A few recent initiatives have supported universities of the arts developing virtual learning environments and providing access to open education resources (OERs). This is the case with the JISC Practising Open Education Project (2010-2011)[23] with six art, design and media departments in UK universities. A number of these OERs include art work (photographs, drawings and videos), but the majority are art theory, mostly research papers, dissertations and art education research documents produced by artists-teachers-researchers as part of their continuing professional development. These are distributed with Creative Commons licenses with varying degrees of freedom, but rarely have the ‘copyleft’ attitude that has been associated with the free software.

Such an enterprise can be interpreted in the light of current debates in the fields of immaterial labour and cognitive capitalism revealing that whilst (digital) art becomes postproduction, art education is being packaged into open resources that circulate as part of the capitalist system, and become central to the new eLearning/networked economies. In addition to filling a gap in subject-specific open resources, this raises the question: why is the free and the open so popular in contemporary art education? A cynical hypothesis is that art education, by declaring itself as a type of production of knowledge, attempts to gain a new legitimacy, in the bureaucratised global knowledge market. The other possibility is that in the face of such a doomed scenario, art education searches for new possibilities beyond pure commercialism, reclaiming access through “contingencies of opening and mobility of cognitive packages beyond confines of ownership.” [24]

1. Floss as artistic –pedagogical method

The Digital Artists Handbook

The digital handbook, published by the arts organisation folly and artists’ collective GOTO10 in 2008, aims to give artists information about the available tools and the practicalities related to Free/Libre Open Source Software and Content such as collaborative development and licenses.

FLOSS+Art

This book edited by Aymeric Mansoux and Marloes de Valk in 2008 reflects critically on the growing relationship between Free Software ideology, open content and digital art. With contributions by: Fabianne Balvedi, Florian Cramer, Sher Doruff, Nancy Mauro Flude, Olga Goriunova, Dave Griffiths, Ross Harley, Martin Howse, Shahee Ilyas, Ricardo Lafuente, Ivan Monroy Lopez, Thor Magnusson, Alex McLean, Rhea Myers, Alejandra Maria Perez Nuñez, Eleonora Oreggia, oRx-qX, Julien Ottavi, Michael van Schaik, Femke Snelting, Pedro Soler, Hans Christoph Steiner, Prodromos Tsiavos, Simon Yuill. Available both in print and as torrent download

Technology Will Save Us

The project by Daniel Hirschman & Bethany Koby is a haberdashery for technology and alternative education space dedicated to helping people to produce and not just consume technology.

Openlab

Openlab Workshops was started by artist and educator Evan Raskob in mid-2009 to fulfil the need for practical education about digital art and technology. Floss workshops are developed and taught by working artists and media practitioners, giving participants direct access to practical experience.

GOTO10

GOTO10 is an artists’ collective that organises floss workshops on subjects such as Pure Data, Linux audio tools, physical computing, SuperCollider, puredyne, RFID, Audio Signal Processing, and other related areas of practice.

UpStage

UpStage is an Open Source platform for cyberformance and education: remote performers combine images, animations, audio, web cams, text and drawing in real-time for an online audience. Initiated by the globally dispersed performance troupe Avatar Body Collision, it runs the annual Upstage festival, open to proposals.

2. Self-organised and self-managed art education

Really Free School

Free school based in a squatted London pub. “Amidst the rising fees and mounting pressure for ‘success’, we value knowledge in a different currency; one that everyone can afford to trade. In this school, skills are swapped and information shared, culture cannot be bought or sold. Here is an autonomous space to find each other, to gain momentum, to cross-pollinate ideas and actions.” (Communiqué #1)

Bruce High Quality Foundation University

A free university project set up by NY-based artists’ collective The Bruce High Quality Foundation. “We believe in the artistically educational possibilities of collaboration. Collaboration, as we mean it, means a group of concerned people come together to hash out ideas, try to figure out the world around them, and try to take some agency within its future. That’s the why and how of The Bruce High Quality Foundation. BHQFU is an attempt to extend the benefits of this collaborative model to a wider number of people.”

Unitednationsplaza

A temporary, experimental school in Berlin, initiated by Anton Vidokle following the cancellation of Manifesta 6 on Cyprus, in 2006. Developed in collaboration with Boris Groys, Liam Gillick, Hatasha Sadr Haghighian, Nikolaus Hirsch, Martha Rosler, Walid Raad, Jalal Toufic and Tirdad Zolghadr, the project travelled to Mexico City (2008) and, eventually, to New York City under the name Night School (2008-2009) at the New Museum. Its program was organized around a number of public seminars, most of which are now available in their entirety online.

FOSSter creative Learning

Lesson plans that can be used in the art classroom, developed by The FOSSter Creativity Team, a group of students of the University of the Arts (USA)

3. Open Source Repositories

University of the Arts institutional OER repository

University for the Creative Arts institutional OER repository

VADS (Visual Arts Data Service) A collection of over 100,000 art and design images that are freely available and copyright cleared for use in learning, teaching and research in the UK.

OER Commons A repository of materials about teaching, technology, research in the emerging field of Open Education. Art materials at OER commons.

You can find paula’s original article on Collaboration and Freedom – The World of Free and Open Source Art http://p2pfoundation.net/World_of_Free_and_Open_Source_Art

This article is part of the Furtherfield collection commissioned by Arts Council England for Thinking Digital. 2011

Cyposium

an online symposium on cyberformance

Friday 12th October 2012

http://www.cyposium.net/

We all perform on the Internet. The social media profiles that we are contractually obliged to give our real names to are just as much performances as our World Of Warcraft or Minecraft avatars. Yet these impromptu performances of our socialised and fantasy selves lack the literary quality of drama. Not drama in the sense of a Usenet or Tumblr flamewar, but in the sense of theatre.

The 1993 New Yorker cartoon captioned “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” identifies two important features of the early public Internet. Firstly it’s a place, somewhere you can get onto. Secondly that place has limited bandwidth for establishing identity and communicating affect. This meant that the Cyberspace of the net became a site for identity play and imagined realities.

As the text-based virtual reality of MOOs gave way to the image-based Palace Chat and then three dimensional AlphaWorld the available bandwidth increased and with it the available ambiguity decreased. Describing a character or a scene or an action with a few words leaves the members of the audience much freer to exercise their own imaginations than seeing it in full motion animation with a high polygon count.

The visual, social and even economic order of virtual worlds and social media have become a more fixed and uncritical embodiment of mass media and the established social order. This has reduced their potential for alterity but it has made them useful representations both of shared reality and shared fantasy that can be used as a stage on which to perform critically, reintroducing the literay against the grain of their unreflective consumption of identity and spectacle.

Throughout this history, from the early 1990s to today, the Internet’s affordances have been used to produce dramatic performance in Cyberspace, “cyberformance”. The problem is we don’t remember this, at least not as clearly as we should. Individually, institutionally, and technologically we have lost our memories of artistically groundbreaking and important performances.

This problem is not unique to cyberformance. All digital art suffers from the decay of digital media and the creeping obsolescence of the hardware that it runs on. Internet art suffers from bitrot, software obsolescence, linkrot, the loss of web pages and sites elsewhere on the net that are connected to the work, and netrot, changes in the protocols used to distribute it.

Above and beyond those problems, cyberformance involves live perfomance. Unique events produced by historical communities at a particular moment using media that will rapidly become obsolete need to be recorded in order to be remembered or at least to be critically re-evaluated later. This creates a second layer of conservation and archiving problems.

Take the example (outside of Cyposium) of Judy Malloy’s “Brown House Kitchen”, a narrative environment created in the LambdaMOO text-based virtual reality. Despite being mentioned in surveys of virtual art in the 1990s, despite being produced with institutional support, and despite being stored on one of the longest-running textual virtual world servers the software objects that made up the work were recycled as part of the normal running of LambdaMOO and are now lost. Many other text-based virtual realities, some specifically designed for dramatic works, are not even online any more. And the protocols used to access them are old, with software to connect to them increasingly not installed by default on newer operating systems. Even those created after the Internet Archive started will not appear in it, as they are not web-based.

I mention LambdaMOO as by chance I was researching text based virtual worlds and performance in the months before Cyposium was announced. One work that was described in the literature but untraceable online was Stephen A. Schrum’s “NetSeduction”. Which Schrum presented and discussed at Cyposium. And the script of the original performance was made available through the Cyposium website. Without Cyposium, these resources would not have been made available.

These contrasting examples drive home just how badly needed Cyposium was. The Internet does enable us to digitise and experience more culture than ever before, but it also erases our memories of the culture that is native to it. And the often highly experimental nature of cyberformance makes it harder to record and remember than almost any other kind of technologically enabled art.

As well as addressing a specific need to recover the history of net performance, Cyposium is an exemplary model for a new kind of online event in the era of Massively Online Open College courses. It performs the function of a symposium or convention online, reducing barriers to access and increasing reach for institutions, speakers and audience members. The Waterwheel Tap software used for most of Cyposium allows side-channels of audience communication, which help to build a sense of place and community and allow the audience to ask (and answer) questions and share knowledge among themselves and with the speakers.

The panel discussions that Waterwheel enabled meant that old and new net performers could discuss each others work in the light of new developments or freshly reconsidered history. And we, the audience, wheoever we were and wherever we were, could watch and learn from this discussion and join in. I am often wary of the word “open”, but there was an intellectual and social generosity and inclusiveness to Cyposium that made it feel like a very open event.

A ripple of excitement went through the mailing lists I subscribe to when Cyposium was announced. Its organizers and line up promised something special, and the event itself didn’t disappoint. To be part of the audience, chatting in text alongside the live streaming video presentations, was to be part of both a welcoming ad hoc conversational community of interest and participating in a key moment in a larger historical conversation.

Cyposium went beyond recovering and presenting the history of online performance. It brought together net performers old and new in productive dialogue in front of an engaged audience and served as an example of a new kind of net native event. Now that the event itself has finished the Cyposium web site serves as an important record of an important aspect of online creativity.

This essay will appear in the forthcoming Cyposium book.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

First off, some claims, some general, some particular. I’m going to use these to speak about the work under consideration and in turn call upon that work to support the claims. A kind of virtuous critical circle.

General: works of art are not messages but objects. They don’t say things nor ask questions, nor assert, nor investigate. Neither do they as objects have messages somehow encoded or embedded within them. To assert otherwise is a massive category error.

As objects they may of course be brought in evidence, copied, become conversation pieces, be described well, be described badly, be described perversely, be seen, be half seen, be missed, be lost, be found, be written about, point to things, be compared and many other things, some of which have not yet been imagined.

Further, artworks are fuzzily-bordered and not necessarily of a physical or temporal piece – the object is not simply the object (and ‘the object’ might not be physical but words, a concept, a sound recording, a protocol) but everything that accretes as a result of it – commentary, jokes, other artworks made in response. If mathematical terminology wasn’t so regularly and toe-curlingly abused in the arts, we might refer to them as manifolds, not necessarily connected.

Even the historical is not immune. There’s a reaching back in time where an established work is transformed retrospectively by homage – ‘Las Meninas’ an obvious case in point.

Also: the work of art is finite – it was born and it will, one day, cease to exist (and it will be forgotten, or there will be no-one to remember it). Everything changes, everything dies.

This implies, too, that although the individual author matters, as product of a unique formation and a unique set of locations in time and space, every artwork is socially authored.

Particular: Abraham’s work represents a new conjunction of technology, collaboration and performance as a generator of moving image. It has precursors (freely acknowledged, indeed celebrated) but it is qualitatively new. The moving image work comes in two flavours, fresh and preserved, both with their own particular and delicious savour. Abrahams conducts live performances on the internet. These performances occur singly, as pieces in themselves, or form part of the programme of events accompanying exhibitions. The moving image pieces in this show are all derivations of this kind of performative event. Except derivation has an air of the hierarchical and the types of piece form no hierarchy any more than fresh or smoked salmon do.

A final general claim: writing about art is not a science but itself an art. Sometimes the brush will be delicate and sometimes broad. There is no recipe or rules or template. One can be too delicate – sometimes confusion is good, particularly in the matter of the affective. Crude thinking sometimes gets us further, paralleling, not dissecting, the richnesses of work. There are some mysteries one should leave as such.

OK. Onwards and upwards…

Performative is currently a much used, some might say overused, word. One quite common usage is to suggest that a work contains visible or at least trackable traces of its own making, a kind of archaeological or sedimentary record, and that perhaps this might have been to varying degrees intentional.

Of course it’s arguable any work of art is performative in this way and that it’s quite hard to erase the trail behind you whether what you make is time based or photographic, sculpted or made with hand applied pigment of one sort or another. Continuous looking and thinking about art for any length of time, especially allied to making stuff oneself, whether dabbling or something more serious, hones an increasing sensitivity to these questions. And this matters; particularly when it comes to over-nice distinctions between close relatives such as the still and moving photographic image and esoteric arguments about how time is differently present or presented in each of these and in other further flung practices too. The new scholasticism feeds on ever finer such distinctions.

So it’s a relief to come across work, which is genuinely performative, enough so that even someone undrenched in theory can see it, can get it and can be delighted and exalted by it. Furthermore work that smells unmistakably of the human, that abuts the high and the low, the crude and subtle, that blurs boundaries, that borrows and echoes the work of others not with the pinched expression of someone with a theoretical framework but in a spirit of ‘why?’ and ‘let’s play’ – the two childish precursors of grown up science and art.

Annie Abrahams’ show at the Centre Régional d’Art Contemporain Languedoc-Roussillon in Sète is a graceful and elegant dog’s dinner of a show. Physically it’s odd, exiled to the upper floor (still a generous space) whilst Catherine Gfeller, someone altogether more easily glossed and hence exhausted (though not without merit) gets the more conventional downstairs galleries (and attracted the lion’s share of the press on the opening night.)

Said upper floor comes in two instalments – a lovely hangar type space, where a game of golf seems distinctly possible, with a kind of tail leading off it, a long thin corridor which fattens a little towards its farther end maybe 100 metres away.

The layout of the show utilises this peculiarity nicely. In the big room a very large two projection installation, Angry Women, spans one corner and takes up a considerable portion of the two adjacent walls.

In the far corner, diagonally opposite, a monitor, with two chairs and two sets of headphones, of which more later.

Leaving the larger space, two more monitor based pieces at junctions where it’s possible for an individual to sit and others to pass. Five chairs arranged in a circle with copies of two books of interviews on each (one with Abrahams, and one with a selection of other cultural figures) and highlighter pens. In the middle of the circle, a pile of blankets. A larger wall piece of rough and ready cardboard placards with texts (“mutuellement vulnérable”, “euphorie communicative”, many others) in various hands.

At the far end, a number of framed photo and images based pieces plus a work consisting of a single photograph and headphone delivered audio (it’s a snapshot – snapshot size, snapshot aesthetic – of husband and wife volunteer fire fighters. The audio is manipulated audio of texts on the subject of fear read by them. Let’s not try and place all this into any sort of context yet. Let’s set out our stall, enumerate, account, describe.)

A final deft touch is the symbolic linking of the two areas by a ribbon of text occupying the 15 or so centimetres above the floor, skirting board height, the topic of which appears to be mental illness (and all elegantly lettered except for one point where a letter had been omitted and is inserted with a caret symbol.)

Most of the pieces employ texts or performances – both gestural and textual – by others – often created according to some seed question or protocol. The texts often come from questions posed on the internet but sometimes from workshop or outreach type (type –this is to tentatively and provisionally locate the thing – it’s outreach Jim, but not as we know it) activity.

The performers in the moving image pieces are geographically dispersed but brought together at a single time by webcams and some custom software that Abrahams has used on a number of occasions where the web-cammed-in participants occupy a space in a rectangular grid (aficionados of seventies UK quiz shows such as Blankety Blank will get it immediately).

There’s a fragility, a delicacy, a tentative hold on existence, a testing of our belief, about these works that so many works of fine art – as opposed to design – have. The sense that what we have incorporates the idiosyncrasies, indeed the weaknesses of the support materials and media, into a final object (the same sense as when an artist wilfully uses something manifestly not intended for art, or allows mistakes to stand, or omits, or makes all too evident repairs; this is not new. Think pentimenti, or the hasty addition of an extra panel of canvas or paper to take account of expanding ambition or vision, or the aestheticized unevenness of Japanese tea-ware.) This sense of object-hood rather than message or statement is key. An objecthood which in retrospect could not have been other, but equally could not have been proposed, foreseen, except in its protocols of playfulness.

The pixellation, dropout, glitching, concomitant upon the pushing of the current state of the network to its limits in the multi participant pieces (and this reminds one of how flicker and roll and a general fuzziness become now part of the Acconci piece Abrahams draws upon in her Theme Song After Acconci – which reasons of space preclude too much detail about here – suffice it to say Abrahams honours, compresses, feminizes, satirises and intensifies the original. If Acconci could have had access to a “better” technology, one where the speed was constant, where no flicker or roll appeared, would he have then felt it served his purpose better? Did what he saw even look fuzzy or worn to him? Probably yes, compared with the film standards of the day, as does Abraham’s work compared with high end digital video [and even the current, rather good, quality of You Tube].)

To offer participants a protocol is paradoxically both to assert and to cede control, to know and to not know how things will turn out (an analogy is the use of chance in the works of Polish composer Witold Lutosławski, where the mechanisms make the generality of the sound, its broad texture, predictable but any particular instance impossible to predict or even fully imagine [but all, please note, a matter of degree because the finer the grain, the greater the level of magnification, the more we can find such uncertainty in anything unfolding over time – it’s a question of our norms – what is the difference between the Stockhausen piano pieces where the performer can choose the order of segments and a Mozart sonata where the tempo may be quite widely varied? – in principle, none])

The piece Pourquoi avons-nous des difficultés à ouvrir un ordinateur et en changer le disque dur? plays on a single monitor with the screen divided into two areas. In each we see, sometimes with difficulty and ambiguously, parts of a computer, screws, connections and hands.

We hear two voices, one that of Abrahams and the other her co-performer, discussant, what have you, Eliza Fantozzi, speaking in French. In the version at Sète there are English subtitles which even for non English speakers provide a kind of functionality, meaning, in that the words tend to be positioned on a line from left to right according to who is speaking. When both speak suggestive gaps appear, though these cannot be read definitively).

The subtitles are in a strange (for a native English speaker) near-English (the title, for example, is translated as “Why do we have difficulties to open a computer and change its hard disk?”).

This is, it must be said, cute, amusing and engaging and it underscores the altogether naughty childlike quality of the entire interchange. The characters (for I think one should mistrust the assumption, however tempting, that we have here unmediated access to the actual participants) are playful – amused and amusing. At the same time they ruthlessly anatomise the roots of their difficulties with technology (but the performativity avoids being on–message in any sense and makes for something strange, complex and even uncomfortable. At one point Fantozzi complains of the lack of colour variety inside the machine and starts painting the components with nail varnish to “create a much merrier circuit” – Je crée un circuit beaucoup plus gai).

Later Abrahams lays into a ribbon connector with a pair of scissors and then starts apparently fringing it with regular cuts half way across … There is an association of the decorative, the playful and a rejection of the serious which is somewhat too close to many gender stereotypes to be entirely comfortable. (The piece was originally performed on international women’s day 2011) And yet, and yet – the end result is complex, for there is a steeliness to the play and a self respect and assertiveness. Perhaps (I don’t know. I don’t think there is a definitive answer. I don’t think close reading or theory can bring us it either) it is the very truthfulness, the richness of the incorporation of the world as it is and not as we might like it to be from which this springs.

Before we get to the physically largest and most imposing presence in the show we’ll look at its neighbour, comprising two chairs, a monitor and two sets of headphones.

Double Blind (Love) is a record of a 264 minute telematic performance by Annie Abrahams and the US artist Curt Cloninger which took place on November the 29th 2009. Annie Abrahams was in the Living Room (Espace de création contemporaine) Montpellier, France and Cloninger in the Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center, Asheville, North Carolina, US.

Both wore blindfolds for the entire duration of the performance, which was a joint telematic musical (and I use the word advisedly; though Abrahams describes Cloninger as a musician she appears to reject the description for herself. I think she is mistaken) performance taking the form of an improvisation, largely vocal but with some keyboard input from Cloninger, around a short musical cell from the track Until the End of the World by U2. The section in question has a repetition of the word “love” for its sole lyrical content and occurs just over midway through the song. It would perhaps ordinarily be described as a chorus but in fact appears only once in the song (although it continues as a backing vocal throughout the next verse), one of the first of many tiny idiosyncrasies on our pathway, peculiarities which add cumulative spice and interest to the project. I’d always found U2 banal and full of bombast but going to the song, under the circumstances of researching this piece, with necessarily open eyes and ears was a small epiphany, one of a number occasioned by a systematic engagement with Abraham’s work.

It’s worth noting that much of the structure of this piece came originally from Cloninger. In the previous year he had performed a number of pieces under the title “pop mantra” where in a live situation he repeated a similar pop music cell for a period of hours (“usually blindfolded”).

Cloninger had also video documented these performances though at this point this is documentation and lives no independent life of its own.

Let’s take a look at these proto ‘Double Blinds’. There is as yet no suggestion of interchange, of development. Although this is clearly a more obvious option with two performers, conscious development is not impossible in a solo performance. It does however appear to be consciously excluded. In an echo of the process or systems driven works of the seventies, Cloninger sets something in motion and allows it to unfold. He attempts to repeat the phrase many times. Presumably his arms start to ache and his voice to tire. This trial of endurance becomes a principal motor of the pieces. What does this evoke? For me, and you might share this, there are the dance marathons of the twenties, the notion of sport, especially individual sport, of pitting oneself against oneself; there is ritual repetition – Sufi whirling, or that carrying out of repetitive, gruelling and apparently pointless tasks sanctified in some Buddhist traditions; the pilgrimage; there is a kind of practical prayer through ritual, suffering or self-abnegation.

The motoric unwinding and associated characteristics obtain in Double Blind, too. What is new, what comes from Abrahams, is the telematic – the fact of separation by an ocean and the fact of collaboration. Indeed there is an inbuilt sharper contradiction as the collaboration separated by so much physical distance is of the peculiar intimacy that attends musical partnership, improvisatory or not. (A couple of years before Abrahams had performed a telematic kiss for three hours with the US artist Mark River.)

Despite Abraham’s denial the finished performance falls entirely within the established parameters of the musical. Precedents such as the work of Meredith Monk could be cited for Abraham’s compelling vocalisations – song, whisper, shout, scream, cry of pleasure, cry of pain – whose musico-dramatic logic and sensitivity to her performing partner, this listener at least, finds totally satisfying. It’s a touching partnership, with both performers bringing a fierce commitment to the task in hand but also each bearing different gifts – Cloninger, a formed musical sensibility supported by conventional skills and Abrahams a kind of discovery/invention of improvisation (indeed of music) ab ovo.

Thousands of years in 4 and half hours.

There is a formal challenge and satisfaction too, common to both Abraham’s and Cloninger’s concerns – how much transcendence can be mined, discovered, invented, from the small, the insignificant? Can it be exhausted before we are exhausted and what does the transfiguration brought about by the attempt suggest about us as human beings?

Two performers. Two chairs for two spectators only. Likewise, two sets of headphones.

Grace.

Opposite, stretching luxuriantly out, is the exhibition’s jewel in the crown – Angry Women, created by Abrahams and twenty two other women of many nationalities, speaking about anger; acting out, demonstrating, reflecting, on anger, on webcams from their different individual locations and in their native tongues, with the images being sent to the 3X4 grid, in a format that Abrahams has made her own. Because of the limits of even current streaming technology it was necessary to conduct two separate performances (separated by an interval of a couple of months). The length of each performance was determined by a protocol where a minute’s silence by all participants signalled the end. This resulted in pieces of differing lengths which lack of synchronisation adds another layer of fragile grace to the final projections, projected large on adjacent walls around the corner joining them with sound from the left images fed to the right speaker and vice versa.

The effect is visceral – we face what feels like a wave of humanity, not so much in numbers, although 23 is impressive, but in the infinite malleability of the face, hands and of gesture and expression and of how these things can occupy the frame. Sometimes that frame will resemble a Giacometti portrait, with the subject appearing to recede into what seems to be endlessly deep space. At others red lips or an open mouth, sensual and terrifying by turns, occupy the whole of the space – and furthermore each cell is constantly in flux (because these are living, breathing unpredictable human beings). There is something both of portraiture and of the dance at work, and a species of found poetry too, which the moving image work has in common with the collaborative texts at the other end of the exhibition. The combination of iron control, planning, foresight (the grid, the protocols) with a letting go and a trust elsewhere – the phased lengths, the blank space for the person who didn’t turn up, the performative possibilities – makes for something of great richness.

Additionally it’s clear that those of the performers who have previous experience are consciously playing with and against their fellows – gestures are mirrored, sounds echoed, the fiction of looking elsewhere (to the side, or above) in the grid is impressively deployed.

The angry women turn out to be at one and the same time very particular –unique – women and women in general too; the women in general turn out to be human beings in general (and general en masse because each so particular) and the human beings in general turn out to live in this, one, our, very particular, world – that mysterious, frightening and wonderful place.