Buy Now and use code: CSF19ASRA for a 30% discount

In India, the practice of jugaad—finding workarounds or everyday, usually non-technical hacks to solve problems—emerged out of subaltern strategies of negotiating poverty, discrimination, and violence. Yet it is now celebrated in management literature as ‘disruptive innovation’. In this book Rai considers how these time-efficiencies always exceed their role in neoliberal and authoritarian postcolonial economies and are put into motion by subaltern practitioners themselves.

On Sat 27 Apr from 14.00-16.00 Rai will introduce this important work to guests followed by a Q and A session with Furtherfield Co-Founding Director, Marc Garrett – with plenty for time for discussion.

This event is hosted at Furtherfield Commons in Finsbury Park* and has been supported by the Borderlines Research Group in Creative Economies and Postcolonial Intersectionality at Queen Mary, University of London.

“This original and innovative work will enable a new and perhaps paradigm-shattering interpretation of the coimplication of digital assemblages, temporality, and affect. Drawing on a rich ethnographic archive, Amit S. Rai is deeply sensitive to how gender, class, and caste are implicated in emergent techno-perceptual assemblages. His invaluable book is also an effective antidote to the Eurocentricity of digital media studies.” — Purnima Mankekar, author of Unsettling India: Affect, Temporality, Transnationality

“Jugaad Time is an important intervention into cartographies of postdigital media cultures. By drawing on the specificity of South Asian cultures, it enriches our understanding of the heterogeneity of these processes. The postcolonial study of media technologies is a vibrant and crucial field of inquiry; Amit S. Rai’s outstanding work is an essential contribution to global approaches to new media scholarship.” — Tiziana Terranova, author of Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age

The event form parts of Furtherfield’s 2019 programme Time Portals.

Octavia E Butler had a vision of time as circular, giving meaning to acts of courage and persistence. In the face of social and environmental injustice, setbacks are guaranteed, no gains are made or held without struggle, but societal woes will pass and our time will come and again. In this sense, history offers solace, inspiration, and perhaps even a prediction of what to prepare for.

The Time Portals exhibition, held at Furtherfield Gallery (and across our online spaces), celebrates the 150th anniversary of the creation of Finsbury Park. As one of London’s first ‘People’s Parks’, designed to give everyone and anyone a space for free movement and thought, we regard it as the perfect location from which to create a mass investigation of radical pasts and futures, circling back to the start as we move forwards.

Each artwork in the exhibition therefore invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

*Please not this is a separate building to our Gallery and is at the Finsbury Park station entrance to the Park.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

The blockchain is widely heralded as the new internet – another dimension in an ever-faster, ever-more powerful interlocking of ideas, actions and values. Principally the blockchain is a ledger distributed across a large array of machines that enables digital ownership and exchange without a central administering body. Within the arts it has profound implications as both a means of organising and distributing material, and as a new subject and medium for artistic exploration.

This landmark publication brings together a diverse array of artists and researchers engaged with the blockchain, unpacking, critiquing and marking the arrival of it on the cultural landscape for a broad readership across the arts and humanities.

Contributors: César Escudero Andaluz, Jaya Klara Brekke, Theodoros Chiotis, Ami Clarke, Simon Denny, The Design Informatics Research Centre (Edinburgh), Max Dovey, Mat Dryhurst, Primavera De Filippi, Peter Gomes, Elias Haase, Juhee Hahm, Max Hampshire, Kimberley ter Heerdt, Holly Herndon, Helen Kaplinsky, Paul Kolling, Elli Kuru , Nikki Loef, Bjørn Magnhildøen, Rhea Myers, Martín Nadal, Rachel O Dwyer, Edward Picot, Paul Seidler, Hito Steyerl, Surfatial, Lina Theodorou, Pablo Velasco, Ben Vickers, Mark Waugh, Cecilia Wee, and Martin Zeilinger.

Read a review of the book by Regine Debatty for We Make Money Not Art

Read a review of the book by Jess Houlgrave for Medium

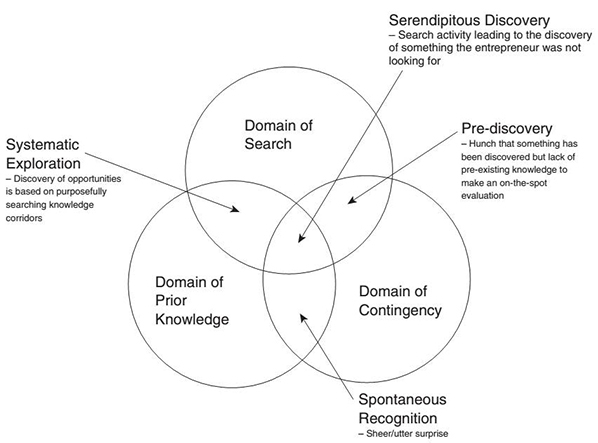

What is serendipity? Notoriously difficult to translate1, it is described as a trivial encounter, a pleasing coincidence, or a moment or encounter that was unplanned and occurred without intentionally looking for it. For Olma there appears to be much more at stake than a charming French accident. In the book ‘In Defence of Serendipity: For a Radical Politics of Innovation’ (2016), Olma gallops through the oppressive apparatus of the creative industries and the tireless illusion of innovation that captivates the hearts of young creatives and designers all over Europe, before finally resting on a call to arms for a radical politics of innovation that encompasses creativity, citizenship and social emancipation.

The notion of serendipity – with its playful innocent charm that promises the unexpected or unplanned potential from the incidental – represents much more than the romantic possibility of chance. As part of his research for the book Olma co-organised a conference on creativity with the Institute of Network Cultures in 20142, where social scientist Pek van Andel 3 provided an anecdotal sentence, which for Olma describes what is at stake in defending serendipity –

“The new and unknown cannot be extrapolated logically from the old and the known” (Andel, 2014).

There are many assumptions surrounding creativity and the production of knowledge, and this possibility to discover the new or the unknown with methods outside of the structures or logic enforced by institutional programs is quite a cunning place to situate a critique on cultural production. After all what is more valuable in contemporary culture than producing the new & the unknown?

For Olma, the aims of culture programs for creatives and designers to create, build and imagine the ‘new’ are misguided, and form part of the many ‘false sleeves of innovation’ in which he seeks to re-instate a political vision for innovation. (Un)fortunately for Olma, he is sat right in the epicentre of this ‘slack innovation culture’, based in a small studio in East Amsterdam where the majority of the artist-run spaces have quickly become boutique hotels, co-work spaces and commercial creative labs. Amsterdam is perhaps only matched by Berlin in its ability to brand a certain lifestyle – a concoction of social innovation and tech entrepreneurism – connected through flexible work spaces, fab labs and start-up hubs that all contributed to the city becoming the official European city of Innovation in 20164.As an artist who moved to the Netherlands to participate in the wide variety of workshops, conferences and collaborative enterprises offered by the wide range of labs, media organisations and institutions in Amsterdam I found Olma’s critique on the lack of political agenda from Dutch cultural organisations thoroughly devastating. For Olma, much of this type of creative activism is an empty political gesture, a speculation and an ideological indulgence for a lost millennial generation attempting to engineer a game-changing prototype or white paper that could make the world a better place (if it ever became anything more than a 5 minute Prezi). To borrow the term coined by Evgeny Morozov, the creative sector has long been adapting the approach of ‘Technological Solutionism’ – programming or designing a technical solution to a social problem – and this is ultimately leading to what Olma describes as ‘Changeless change’. Olma sees this as a dominant, restrictive logic that has pervaded not just the creative economy but other sectors of education, healthcare and state services for years. He insists that defending the possibility of spontaneity, chance and coincidence in the face of regulated, market-driven creative programs is the way to make innovation innovative again.

“The paradox is that while relying on informal and idiosyncratic forms of interpersonal exchange, cybernetics spawned a techno-social ontology, reducing human beings to increasingly calculable, controllable and predictable factors within systems” (pg 160, 2016)

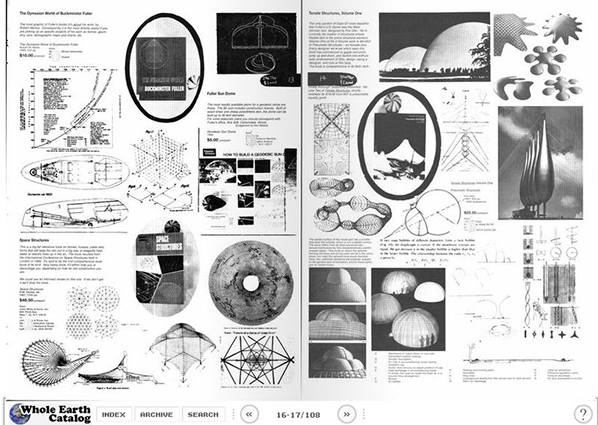

Olma occasionally describes conditions in the past century where serendipity was openly facilitated and creative innovation demonstrated radical political values. Universities – such as the well cited Black Mountain college (whose students included John Cage & Buckminster Fuller) – and co-working spaces originally provided much potential for chance encounters at little or no cost, and even the invention of cybernetics involved a degree of spontaneity. The hippy counter-culture movement and the communalists of the late 1960s were making a radical attempt to form an alternative social transformation and organise flexible communes and temporary networks. If you go back to this starting point it is easier to grasp how the premise of Silicon Valley originated from a radical politics of innovation. Buckminster Fuller, Stuart Brand and even Steve Jobs were designing and building alternative visions of the world which are now perpetually carried in the pockets of over 160 million people. These were creatives, designers, hackers and hippies who built their own vision of reality and successfully sold it to the western world. It is little wonder then that even after half a century creatives still believe in the emancipatory potential for technological design to engineer large-scale social change. This attitude resides in young creatives like a hangover, with many believing the most important part of any project is the ability to harness the power of the network and ‘scale up’ or utilize the latest technologies (e.g. IoT blockchain, A.I) in order to ‘build a better world’.

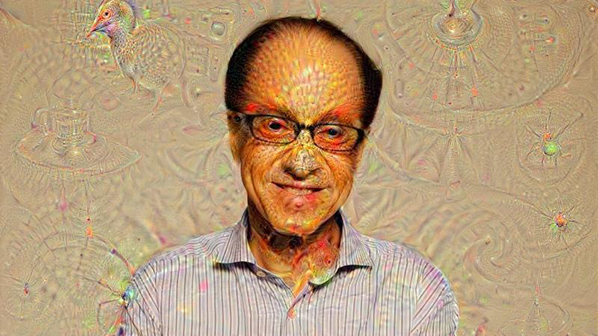

The global dominance that Silicon Valley has managed to groom over the creative economy has left very little room for creatives, designers and technologists to imagine future(s) other than the ones packaged and sold by the CEOs of the four major tech companies (GAFA5). Olma dives into the disillusion perpetuated by figures like Ray Kurzweil and Elon Musk and offers some insight into how the idea of the singularity is proliferated as an artificial salvation from a crisis that – arguably – they are responsible for. What is so powerful about these myths is the way they are presented as an inevitability, a natural outcome of what is known as ‘Moore’s law’ (the theory that computing power grows exponentially). Aside from the fact that, as Olma highlights, this theory (it’s not a law) is beginning to look more and more unlikely due to increasing demand and finite resources, 6 the mythical fantasy is also a fantastic narrative that – regardless of plausibility – enchants the masses, enticing them towards the promise of a techno-spiritual enlightenment. The singularity, similar to The Enlightenment, is an alternative way to defy the gods and transcend both space and time (whether that is flying to Mars with Elon Musk or staying alive forever by eating nothing but berries with Ray Kurzweil 7). It also reintroduces the notion of a collective consciousness and mobilises the technologists, hackers and creative programmers towards a transcendent , spiritual (post-human) awakening. What distresses me is how often artists and designers (including myself!) are encouraged either through directed funding programs or just through their own curiosity to unwittingly contribute free or intellectual labour to improve, train and develop the latest technology. This is very familiar in the development and production of Artificial intelligence. When Google releases the source code for A.I products such as DeepMind’s neural network 8, they are doing so predominantly to crowd-source the development of the software and improve the ‘machine learning’ process of the application. This way, the countless enthusiasts creating their own ‘neural nets’ or simply sharing more ‘slug dog puppies’ 9 incidentally form an army of free researchers, crowd-sourcing the big data and enabling companies to train and deploy more powerful machine learning systems. The sweeping tide towards Artificial Intelligence and eventual leap towards the singularity – whilst being very good for sensationalising and selling further tech products – lures over the collective creative imagination of many artists and creative technologists and consequently makes it increasingly challenging to design an mobilise an alternative vision that does not just further the one sided Singularity story. In the final chapters of the book, Olma quotes Julian Assange who famously said “there are only two types of belief systems that are capable of transforming change on a global scale, that of silicon valley libertarianism and that of radical Islam”(pg 211, 2016). The way in which Olma maps out how Californian hippy counter-culture advanced into techno-libertarianism to the prospect of a technological enlightenment, highlights how ‘a belief system [can] turn populations into docile followers of the dominant logic of power’ (pg 119, 2016) The conclusive effect of Olma’s analysis is that there is a generation of young people who assume that transformative social change can be engineered through programming, code and technical design, and not through politics. Furthermore, the promise of a collective consciousness in the form of the singularity propagates the belief that this particular strain of Randian individualism will eventually give way to something egalitarian, collective and enlightening.

“Today, a radical politics of innovation must be directed toward the recapture of the state by an ideology that is a polemic for the reinvention of a public sphere whose accidental sagacity will generate potential futures we don’t even dare dream about” (pg 217, 2016)

While admitting that the odds of reclaiming a practice of innovation that is genuinely alternative, transformative and political are slim, Olma offers us some potential new directions to consider. After relentlessly exposing the libertarian attitude that has permeated through technological innovation into creative culture, Olma considers how to collectively care for the imaginary ‘we’. Rather than champion a Luddite perspective in relation to digital technology, Olma asks us to re-consider the effect tech culture has had on creative practices up to this point. He asks us to distance ourselves from creative programs that provide ‘simulations of serendipity’, which are in-fact co-ordinated idealogical parameters that only produce vague, washy attempts to ‘make the world a better place’. Olma asks us to call their bluff and put an end to intellectual entrepreneurialism and champion creative engagements that are political to their core. No more tinkering prototypes or speculative designs that show no political agenda than simply ‘making the world a better place’– a reactionary counter culture is needed. Fixing this creative depression is key to articulating and mobilising a collective response to neo-liberal politics and free market economics. Olma goes on to state that “Creativity and citizenship should be two sides of the same coin”. If artists and designers are able to direct their own autonomous practices that are not based on imitating the same technological solution-ism we have been subject to till now, then a vehicle for alternative political programs through creative expression is possible. However, my concern is that the current creative and start-up infested world might be so deeply ingrained that it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to try and distinguish between what Olma describes as ‘false innovation’ and identify what qualifies as ‘good innovation’. Making such a distinction is based on political subjectivity, which will always fall short on a old framework of left and right ideological values. Take for example a typical Dutch design competition called What Design Can Do, which last year asked designers to respond to what they call the ‘refugee challenge’ 10. 3D printed modular homes, food trucks, democratic voting apps and interactive maps provided business, charities and NGOs with a huge selection of ideas and concepts to help contribute towards improving the humanitarian crisis. Now, even without fully evaluating the impact of each project I would still find it difficult to dismiss all the endeavours as nothing more than what Olma describes as ‘change-gymnastics’ (pg77,2016). I think what Olma is requesting in his writing is for a more audible and self-reflective practice of innovation so that “the social contexts of the technologies used [are] part and parcel of its practice” (pg 68, 2016). In this sense, perhaps a greater critical evaluation is required when determining the value of social innovation. When considering Olma’s analysis in the context of 2017, forming a radical politics in the face of neo-liberal or neo-fascist regimes should hopefully galvanize and mobilise a unified resistance, however one has to be aware of the fused social corporate structure in which these common forms of resistance will eventually manifest. Brands are quickly tapping into and attempting to integrate alongside social activism 11 and an agency I was recently introduced to titled Doyougetme.world? specialises in connecting brands with ‘radical’ activism12. Although these initiatives may appear to be the latest attempts from corporations to engage with young consumers I believe they highlight the hybrid culture in which this radical politics of innovation will need to emerge. What if a mass mobilisation was initiated or deployed by a brand or corporation, as imagined in this uncanny piece of short fiction that was published this month by Andrea Phillips entitled ‘The Revolution, as bought to you by Nike’ 13. In this story, Nike launch a pitch perfect campaign in order to start a social revolution and the strategies of brand engagement become the tools with which to manifest large scale disruption to globalized power and corruption. The plausibility of such an attempt is very credible at a time when both citizens and companies are converging to protest against president Donald Trump and his decisive actions seem to divide citizens and open up new markets of political consumers. Considering these manoeuvres, one should be prepared for a radical politics of innovation to be a multifaceted, multi-political project, and not rely on a traditional political framework to evaluate creativity, innovation and citizenship. It is an important time to ask how creativity, social innovation and tech culture can support social mobility and radical politics, when what feels like an uncontrollable rise of neo-fascism, rather than dismiss existing creative practises of innovation it is an opportunity to consider how creativity can once again become the vehicle to take us out of ‘changeless change’ and into a radical politics of innovation.

Max Dovey

‘In Defence of Serendipity : For a Radical Politics of Innovation’ by Sebastian Olma is out now from Repeater Books http://repeaterbooks.com/books/in-defence-of-serendipity-sebastian-olma/

Max Dovey is a researcher, artist and critic based in Netherlands.

Www.maxdovey.com