From inside the stillness of lockdown, we used The Hologram’s viral healthcare system to make a space for radical planning for the post-pandemic futures we wanted. In this Live Action Role-Play, or LARP, 12 people made contact with who they would become, individually and collectively, by 2050. In this immersive game participants played characters based on the most powerful and well-supported version of themselves. They time travelled 30 years in three weeks to enact their survival and thriving through multiple emergencies and crises. Human systems collapsed and reformed, in the wake of social upheavals borne of entrenched colonialism and racism and environmental crises. Capitalism ended.

We were made for this // 2050 Fugitive Planning

12 people participated in a series of 3 online events as part of a Live Action Role-Play.

The documentation will be used to generate a sci-fi trailer to inspire future Hologrammers

The Hologram LARP was co-created by Cassie, Lita, Ruth, Magda, Melanie, Shawn, Alessandra, Maggie, Lauren, Stella, Katrine, Darcey, Lyra, Lara and Tamara.

The Hologram is a viral four-person health monitoring and diagnostic system practiced from couches all over the world. Three non-expert participants create a three-dimensional “hologram” of a fourth participant’s physical, psychological and social health, and each becomes, the focus of three other people’s care in an expanding network.

The Hologram is supported by Furtherfield and CreaTures – Creative Practices for Transformational Futures. CreaTures project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870759. The content presented represents the views of the authors, and the European Commission has no liability in respect of the content.

This article reflects on the hopes of Cyberfeminism in response to ‘Revisiting the Future: Technofeminism in the 21st Century‘, a panel discussion between Mindy Seu, Cornelia Sollfrank, Judy Wajcman, and chair Marie Thompson. This conversation took place on the 5th of October 2019 at the Barbican Centre in London, UK, as part of New Suns: A Feminist Literary Festival.

BIG DADDY MAINFRAME

“What’s so special about Lisa? Oh, I’ve had a lot of computers, but my Lisa is different: she works the way I do”

Apple Lisa, video infomercial, 1983

Men, like gods, have always had a thing for creating entities in their own image. Gods create men, men will gods into existence. Men create tools, tools make men in turn. But what if the creator of technology is often a man, and a very specific kind of man? What are, then, the ways in which gender and technology construct one another?

Since the dawn of computation, men found it appealing to automate away the predictable and repetitive labour, often embodied and performed by women. In other words, technology has contributed (among a lot of other things) to the automation of traditional “women’s work”, and it did so on men’s terms [1]. From the Girl-less, Cuss-less Phone, the first automated dial system (1892), to Lisa, the first personal Apple Computer (1983), to Siri and Alexa, digital assistants, (2011 and 2014), the designs of and designs for the pater ex machina have set the bar for the height of technological progress.

Cyberfeminism is a feminist genre that addresses questions of gender and technology while bringing their implications to the fore. Automation is not the only nor the central theme of Cyberfeminism: academics, activists, hackers, artists, women, and non-women tied to this genre, engage with broad questions of gender and technology based on the assumptions that:

Largely, grounded in Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, Cyberfeminism as a movement was formally articulated in 1991 by the Adelaide based artist collective VNS Matrix. VNS designed a billboard titled “A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century” depicting horned bodies, psychedelic vulvas and reciting: “[…]we are the virus of the new world disorder rupturing the symbolic from within; saboteurs of big daddy mainframe; the clitoris is a direct line to the matrix.” That said, the origins of the genre can be traced more accurately as a decentralised global emergence. Cyberfeminism has come to life more like a granular collection of scattered raw data, and less like a single revelation happened at a defined point in time.

In the panel Revisiting the Future: Technofeminisms in the 21st Century, Mindy Seu, Cornelia Sollfrank, Judy Wajcman and Marie Thompson discussed the state of Cyberfeminism today.

ATTESTING TO THE REVIVAL

Chair Marie Thompson points out how, in the past decade, there seems to be a reinvigorated tendency for questions of Cyberfemnism. The increased mainstreaming of concerns around gender and technology in institutional contexts such as Girls Who Code, Women in Tech Festival, and countless diversity initiatives in tech companies are clear examples. To Thomson, the main question is “why should we struggle for Cyberfeminism now?”

“Silicon Valley can do [diversity inclusion campaigns]” says Judy Wajcman, “that’s fine, but what is the kind of big-scale change that must occur at institutional level?”. Wajcman emphasised how important it is to embed inclusion into the fabric of tech companies’ culture rather than it remaining a CSR exercise, or better, rather than supporting and reinforcing existing liberal frameworks.

According to Mindy Seu, Cyberfeminism revival is largely due to the need of big institutions to accumulate cultural capital which is often articulated in superficial measures such as cosmetic diversity initiatives. For Seu, similarly to Wajcman, the main question is ”how can we see feminist values embedded in the ethos of companies?”. Seu also points out how the ascension of women in big cultural (and tech) institutions are often not only hindered by the notorious “glass ceiling”, but also deliberately sabotaged through the so-called “glass cliff”. A glass cliff is a term used to describe a situation where a woman is nominated head of an organisation which is already crumbling. The intention is to signal externally that this organisation is making efforts to get back on track, or make amends for its corrupted past by hiring someone with a perceived higher ethical value. By doing so, the board actively sets up this woman (or anyone, really) to fail, because the organisation has larger structural problems that no person alone can solve (see recent board allegations concerning MIT Media Lab).

“It is as if nothing has happened in between the 90s and now,” Cornelia Sollfrank says. “This means that things [gender inequality within the tech industry] are staying the same, and maybe getting worse… These, mostly young, very young, women do not understand the historical precedents of Cyberfeminism.” While she seems to partially dismiss this revival as a fashion statement, her book ‘The Beautiful Warriors. Technofeminist Praxis in the Twenty-First Century’ sets out to counter this trend by connecting up the insights and practices of 90’s cyberfeminism with new techno-eco-feminists as part of an ongoing social and aesthetic activism.

RE-MAKING THE INTERNET

“This is not a book about women and technology. Nor was this book created for women. Throughout these pages, scholars, hackers, artists, and activists of all regions, races, sexual orientations, and genetic make-ups consider how humans might reconstruct themselves by way of technology. What is a woman anyway?”

Intro from Cyberfeminism Catalog 1990-2020, Mindy Seu, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2019

One strategy to challenge the dominant narrative of men as sole creators and geniuses, argues Seu, is to incorporate women’s voices in the history of computation. As she puts it: “We are taught to focus on engineering, the military-industrial complex, and the grandfathers who created the architecture and protocol. But the internet is not only a network of cables, servers, and computers. It is an environment that shapes and is shaped by its inhabitants.” In her Cyberfeminist index, Seu traces a detailed and precise overview of the diverse body of today’s practices.

Across the panel, there seemed to be a shared awareness of differences in terms of references, strategies, culture, and visual cultures among current activists and academic groups and across generations. One example that stands out is the South Korean Cyberfeminist group Megalia whose main strategy for activism has been online trolling. Looking at their logo, a hand making the gesture to indicate a man’s penis size, it is not hard to understand their style of communication. Megalia could be dismissed as a funny and naive case, but there are deep reasons why South Korean women have implemented such a strategy. For instance, feminism has only entered the public sphere less than a decade ago.

As Judy Wajcman points out, the dominant narratives in feminist discourse are set up by Western standards. For instance, in South America, she notes, Donna Haraway is not as strong an academic reference as in the West. Wajcman also argues that Haraway’s texts, despite advocating for socialist feminism and having strong political agendas, often lack the clarity and simplicity to be accessed by anyone who does not belong to the hyper educated Western academia elite. Seu points the attention towards the fact that Haraway supposedly decided to use contrived language intentionally (as a hack), in order to be deemed interesting and relevant in academic context.

THE OTHER

Cyberfeminism is relevant today more than ever when addressing topics of responsibility, agency, materiality, care, and anthropocentrism. In this sense, Cyberfeminism today transcends identity politics: it becomes an essential cultural tool with respect to survival, equality, and sustainability.

Cyberfeminism can be defined as “a genre of contemporary feminism which foregrounds the relationship between cyberspace, the Internet and technology.” [3]

To foreground is the action of pushing objects that are necessary in the background to the fore. That is bringing the hidden, compounded, interchangeable, opaque to a position that is close enough to the viewer to be observed. In other words, turning the distant and neglected “other” into voices and materials that can be seen, heard, interrogated.

To bring the back to the fore is, on the one hand, to question men’s protagonism, self- importance, and arrogance, thus attempting to dismantle not only the centrality of men as male humans, but that of humanity as a whole. Anthropocentrism has been at the core of technological developments. Humans have predominantly designed for human comfort (with the standard for “human” being effectively set up by men) narrowing down the possibilities of what technologies could be or do.

Complimentarily, foregrounding is also the practice of exposing the material and toxic aspects of technological progress and production both in terms of human labour and ecological implications, from e-waste to amounts of energy voraciously consumed by computational tools and infrastructures, to labour-heavy mining of rare earth minerals.

In stark contrast with the early days of eco-feminism which was expressively anti-technology, the panel maps out emerging strands of (techno) eco-feminism that critically engage with questions of gender, cyberspace, and ecology from a holistic perspective. This approach is not in opposition of technological tools, but rather in conversation with them. In this sense, techno-eco-feminism is close to the Haraway’s idea of questioning scientific methods not with the goal to invalidate them, but rather to ask “what are ways in which science can be used for emancipatory purposes?”

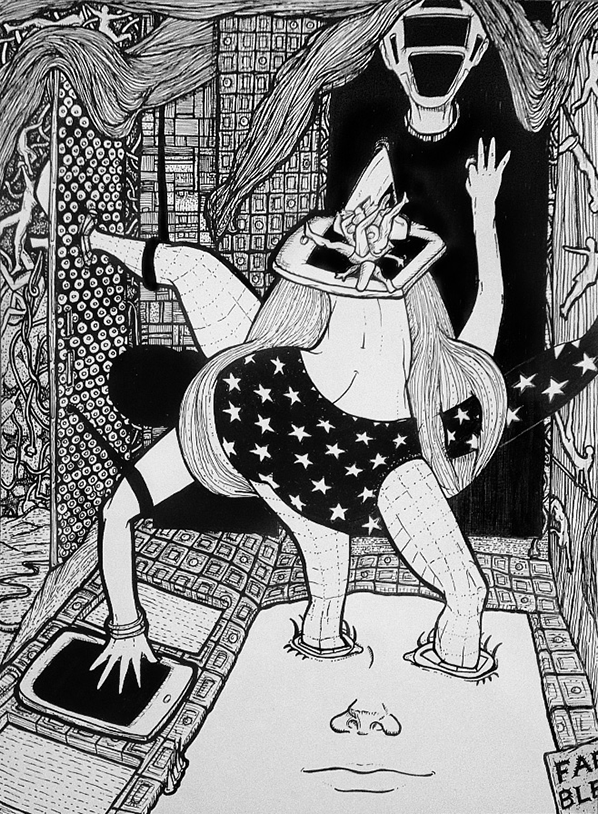

Featured Image:

Artwork by Cecilia Serafini

from New Suns Festival 2019

Header Image:

Screenshot of Siri by Chiara Di Leone

The English tranlsation of The Beautiful Warriors. Technofeminist Praxis in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Cornelia Sollfrank. Can be found here – http://www.minorcompositions.info/?p=976 and all decent book retailers.

Our times are characterized by the accelerating collapse and redrawing of multiple borders: between nation states, personal identities, and the responsibilities we have for each other. Also between the old distinctions, work and pleasure.

Some leaders as part of the new world order, tell us through their political actions and their fashion accessories, that they “Just Don’t Care”. This “political art-form”1 of not caring permits an insidious spread of hatred online and on the ground. In recent times, the digital condition has lent it’s networks and platforms to this poisonous, rhetorical hyperbole, turning against immigrants, and others who do not fit into the framework of a western world, oligarch orientated vision. Mass extraction and manipulation of social data has facilitated the circulation of fake news and the production of fear, anxiety and uncertainty. Together these fuel the machine of structural violence adding to the already challenging conditions created by Austerity policies, growing debt and poverty.

In the face of these outlandish difficulties our digital tools and networks – taken up with a spirit of cultural comradeship. More inspiring narratives are emerging from across disciplines and backgrounds, to experiment with new solidarity-generating approaches that critique and build platforms, infrastructures and networks, offering new possibilities for reassessing and re-forming citizenship and rights.

The exhibition and labs for Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival, have created new contexts for collaboration. Artists (from the local area and internationally), game designers and architects, come together with researchers from psychology and neuroscience addressing the data driven gamification of life and everything.

In her interview, the curator Dani Admiss discusses how they reassess the power relationships of the gallery, park users and the local authorities, asking who owns the cultural infrastructure and public amenities – and so create a polemic to open up questions of public value. The exhibition is open every weekend through 14 July to 19 August 2018.

The artists featured in Transnationalisms exhibition curated by James Bridle address the effect on our bodies, our environment, and our political practices of unstable borders.

“They register shifts in geography as disturbances in the blood and the electromagnetic spectrum. They draw new maps and propose new hybrid forms of expression and identity.”2

“Thiru Seelan, a Tamil refugee who arrived in the UK in 2010 following detention in Sri Lanka during which he was tortured for his political affiliations, dances on an East London rooftop. His movements are recorded by a heat sensitive camera more conventionally often used to monitor borders and crossing points, where bodies are identified through their thermal signature.”3

The show opens at Furtherfield from September 14th to October 26th 2018, touring as part of State Machines the EU cooperation which investigates the new relationships between states, citizens and the stateless made possible by emerging technologies.

We have another interview with artist and activist Cassie Thornton, where we discuss her current project Hologram, which examines health in the age of financialization, and works to reveal the connection between the body and capitalism. Her interview focuses on a series of experiments that actively counter the effects of indebtedness through somatic – or body – work including her focus on the way in which institutions produce or take away from the health of the artists and workers they “support”.

“In my work for the past decade, I have been developing practices that attempt to collectively discover what debt is and how it affects the imagination of all of us: the wealthy, the poor, the indebted, financial workers, babies, and anyone in-between.” Thornton

Finally I interview Tatiana Bazzichelli, artistic director and curator of the Disruption Network Lab, in Berlin, questions about art as Investigation of political misconducts and Wrongdoing. Since 2015, the Disruption Network Lab has cultivated a stage and a sanctuary for otherwise unheard and stigmatised voices to delve into and explore the urgent political realities of their existence at a time when the media establishment has no investment in truth telling for public interest.

“When the speakers are with us and open their minds to our topics, I feel that we are receiving a gift from them. I come from a tradition in which communities, networks and the sharing of experience were the most important values, the artwork by themselves.” Bazzichelli.

The programme creates a conceptual and practical space in which whistleblowers, human right advocates, artists, hackers, journalists, lawyers and activists are able to present their experience, their research and their actions – with the objective of strengthening human rights and freedom of speech, as well as exposing the misconduct and wrongdoing of the powerful.

To conclude, all one needs to say is…

“Whether in the variety of human, backgrounds and perspectives, biodiversity or diversity of technologies, coding languages, devices, or technological cultures. Diversity is Proof of Life.” Ruth Catlow, 2018.

Since the financial crash 10 years ago, we’ve learned that it tends to be everyday people, on the ground, who pick up the pieces and not governments. Millions have been dragged into poverty while those who caused the “crisis”, after creating dangerously high levels of private debt, remain unscathed. [1] The UK Conservative government’s response was an Austerity policy, driven by a political desire to reduce the size of the welfare state. Amadeo Kimberly says, “austerity measures tend to worsen debt […] because they reduce economic growth.”[2] The effect has been devastating, creating all together, more homelessness, precarious working conditions and thus pushing working communities, deeper into debt. In the UK, the NHS is being privatized as we speak. According to a CNBC report, medical bills were the biggest cause of bankruptcies in the U.S in 2013, with 2 million people adversely affected. [3]

The work of artist and activist, Cassie Thornton is included in the upcoming Playbour– Work, Pleasure, Survival exhibition at Furtherfield, curated by Dani Admiss. In this interview I wanted to explore the following questions as revealed in her current Hologram project:

Cassie Thornton is an artist and activist from the U.S., currently living in Canada. Thornton is currently the co-director of the Reimagining Value Action Lab in Thunder Bay, an art and social center at Lakehead University in Ontario, Canada.

Thornton describes herself as feminist economist. Drawing on social science research methods develops alternative social technologies and infrastructures that might produce health and life in a future society without reproducing oppression — like those of our current money, police, or prison systems.

Marc Garrett: Since before the 2008 financial collapse, you have focused on researching and revealing the complex nature of debt through socially engaged art. Your recent work examines health in the age of financialization and works to reveal the connection between the body and capitalism. It turns towards institutions once again to ask how they produce or take away from the health of the artists and workers they “support”. This important turn towards health in your work has birthed a series of experiments that actively counter the effects of indebtedness through somatic work, including the Hologram project.

The social consequences of indebtedness, include the formatting of one’s relationship to society as a series of strategies to (competitively) survive economically, alone, to pay the obligations that you has been forced into. It takes so much work to survive and pay that we don’t have time to see that no one is thriving. Those whom most feel the harsh realities of the continual onslaught of extreme capitalism, tend to feel guilty, and/or like a failure. One of your current art ventures is the Hologram, a feminist social health-care project, in which you ask individuals to join and provide accountability, attention, and solidarity as a source of long term care.

Could you elaborate on the context of the project is, as well as the practices, and techniques, you’ve developed?

CT: Many studies show that the experience of debt contributes to higher levels of anxiety, depression, and suicide. Debt disables us from getting the care we need and leads us away from recognizing ourselves as part of a cooperative species: it is clear that debt makes us sick. In my work for the past decade, I have been developing practices that attempt to collectively discover what debt is and how it affects the imagination of all of us: the wealthy, the poor, the indebted, financial workers, babies, and anyone in-between. Under the banner of “art” I have developed rogue anthropological techniques like debt visualization or auxiliary credit reporting to see how others ‘see’ debt as an object or a space, and how they have been forced to feel like failures in an economy that makes it hard for anyone (especially racialized, indigenous, disabled, gender non-binary, or ‘immigrant’) to secure the basic needs (housing, healthcare, food and education) they need to survive, because it is made to enrich the already wealthy and privileged.

“The rise of mental health problems such as depression cannot be understood in narrowly medical terms, but needs to be understood in its political economic context. An economy driven by debt (and prone to problem debt at the level of households) will have a predisposition towards rising rates of depression.”[4]

After years of watching the pain and denial around debt grow for individuals and entire societies, I was so excited to fall into a ‘social practice project’ that has the capacity to discuss and heal some of this capital-induced sickness through mending broken trust and finding lost solidarity. This project is called the hologram.

MG: What kind of people were involved?

CT: The entire time I lived in the Bay Area I was precarious and indebted. I only survived, and thrived, because of the networks of solidarity and mutual aid I participated in. As the city gentrified beyond the imagination, I was forced to leave. I didn’t want to let those networks die. So, at first, the people who were involved were like me– people really trying to have a stake in a place that didn’t know how to value people over real estate and capital

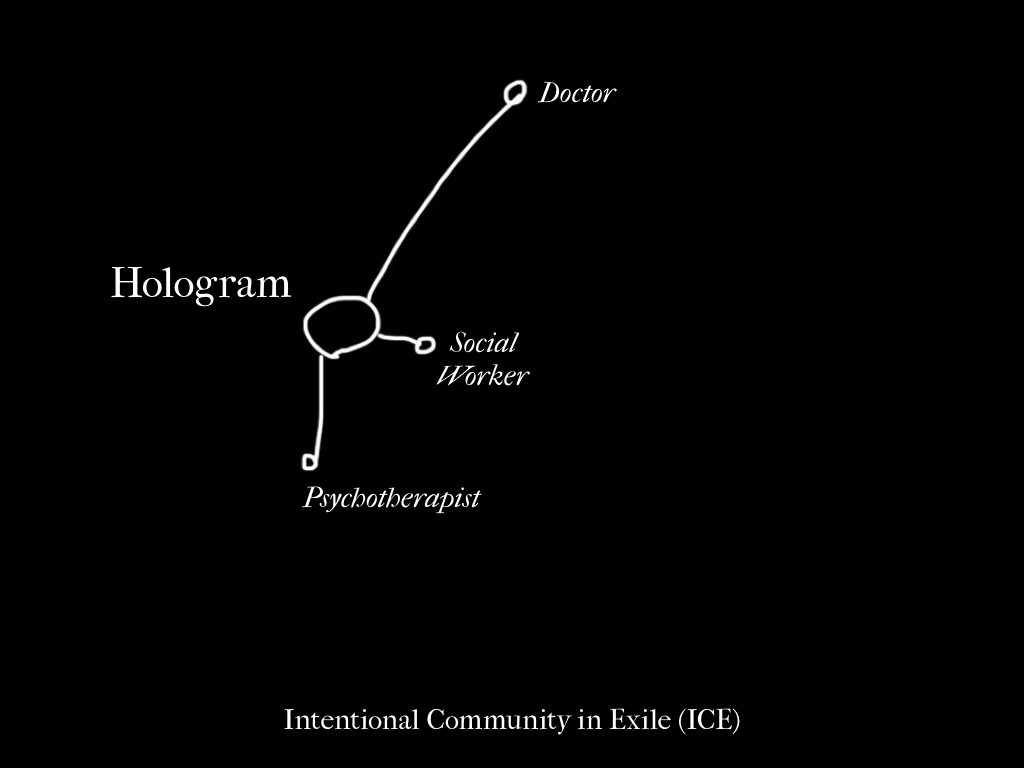

The hologram project developed when, as I was leaving the city, I had invited a group of precariously employed, transient activists and artists to get together in the Bay Area for a week of working together. We aimed to figure out ways to share responsibility for our mutual economic and social needs. This project was called the “Intentional Community in Exile (ICE)” [the ICE pun was always there, now an ever more intense reference in the public eye] and it grew out of an opportunity offered by Heavy Breathing to choreograph an event at The Berkeley Art Museum. They allowed me to go above and beyond my budget to invite a group of 8 women together from across the US to choreograph methods of mutual aid: sharing resources, discussing common problems and developing methods for cooperating to co-develop an economic and social infrastructure that would allow us to thrive together, interdependently. What would it mean for our work as activists and artists to feel that we had roots within an intentional community, even if we didn’t have the experience of property that makes most people feel at home?

Facebook event: “In departing from the idea of a long term home, family, property, or ownership, ICE models a mutual aid society to sustain creative and political practices within a hostile economic system. This project is about finding ways to exit economic precarity by building human relationships instead of accumulating capital– or to make exile warm. After a one week convergence of a small group of collaborators, ICE presents a discussion and performance of life practices as well as frameworks for material and immaterial mutual support.”

The Hologram was one of many ideas that developed as part of this project. One of the group members, Tara Spalty, founder of Slowpoke Acupuncture, (and one of the two acupuncturists you will see at SF protests or homeless encampments) and I fell into this idea when combining our knowledge about the solidarity clinics in Greece, our growing indebtedness and lack of medical records, and the community acupuncture movement. Then the group brainstormed about what the process would be like to produce a viral network of peer support.

MG: What inspired you to do this project? (particularly interested in the Greek influences here and what this means to you)

CT: My practice of looking at debt became boring to me by 2015 as it became more and more clear that individual financial debt was a signal of a larger problem that was not being addressed. The hyper individualism produced by indebtedness allows us to look away from a much bigger deeper story of our collective debts, financial and otherwise. We don’t know what to do with these much bigger debts, which include sovereign debts, municipal debts, debts to our ancestors and grandchildren, debts to the planet, debts to those wronged by colonialism and racism and more. We find it so much easier to ignore them.

When visiting austerity-wracked Greece after living in Oakland, I noticed that Oakland appeared to have far more homeless people on the street. It made me realize that, while we label some places “in crisis,” the same crisis exists elsewhere, ultimately created and manipulated by the same financial oligarchs. The hedge funds that profit off of the bankruptcy in Puerto Rico are flipping houses in Oakland and profiting off of the debt of Greece. We’re all a part of the same global economic systems. The “crisis” in Greece is also the crisis Oakland and the crisis in London. For this reason, I have been interested in what we can all learn from activists, organizers and others in crisis zones, who see the conditions without illusions.

This led me to an interest in the the Greek Solidarity Clinic movement, which since “the crisis” there has mobilized nurses, doctors, dentists, other health professionals and the public at large to offer autonomous access to basic health care. I went to go visit some of these clinics with Tori Abernathy, radical health researcher. Another project using this social technology is called the Accountability Model, by the anonymous collective Power Makes Us Sick. These solidarity clinics are run by participant assembly and are very much tied in to radical struggles against austerity. But they have also been a platform for rethinking what health and care might mean, and how they fit together. The most inspiring example for me was in at a solidarity clinic in Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece. The “Group for a Different Medicine” emerged with the idea that they didn’t want to just give away free medicine, but to rethink the way that medicine happens beyond conventional models, including specifically things like gender dynamics, unfair treatment based on race and nationality and patient-doctor hierarchies. This group opened a workers’ clinic inside of an occupied factory called vio.me as place offer an experimental “healed” version of free medicine.

When new patients came to the clinic for their initial visit they would meet for 90 minutes with a team: a medical doctor, a psychotherapist and a social worker. They’d ask questions like: Who is your mother? What do you eat? Where do you work? Can you afford your rent? Where are the financial hardships in your family?

The team would get a very broad and complex picture of this person, and building on the initial interview they’d work with that person to make a one-year plan for how they could be supported to access and take care of the things they need to be healthy. I imagine a conversation: “Your job is making you really anxious. What can we do to help you with that? You need surgery. We’ll sneak you in. You are lonely. Would you like to be in a social movement?” It was about making a plan that was truly holistic and based around the relationship between health, community and struggles to transform society and the economy from the bottom-up . And when I heard about it, I was like: obviously!

So the Hologram project is an attempt by me and my collaborators in the US and abroad to take inspiration from this model and create a kind of viral network of non-experts who organize into these trio/triage teams to help care for one another in a complex way. The name comes from a conversation I had with Frosso, one of the members of the Group for a Different Medicine, who explained that they wanted to move away from seeing a person as just a “patient”, a body or a number and instead see them as a complex, three dimensional social being, to create a kind of hologram of them.

MG: Could you explain how the viral holographic care system works?

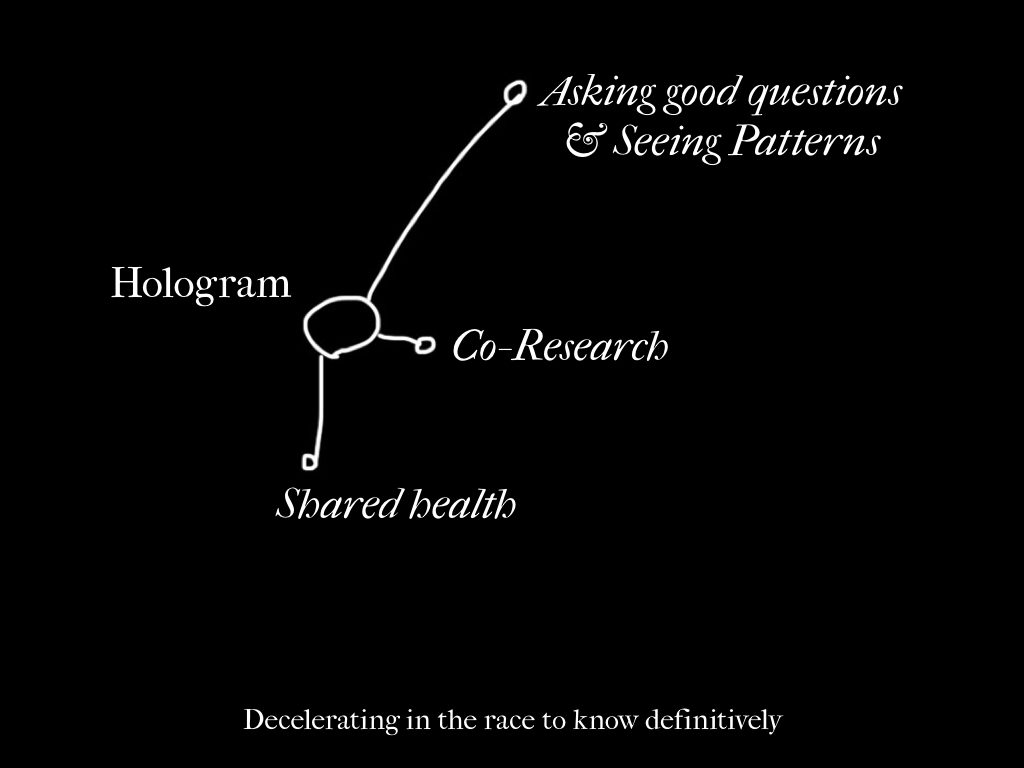

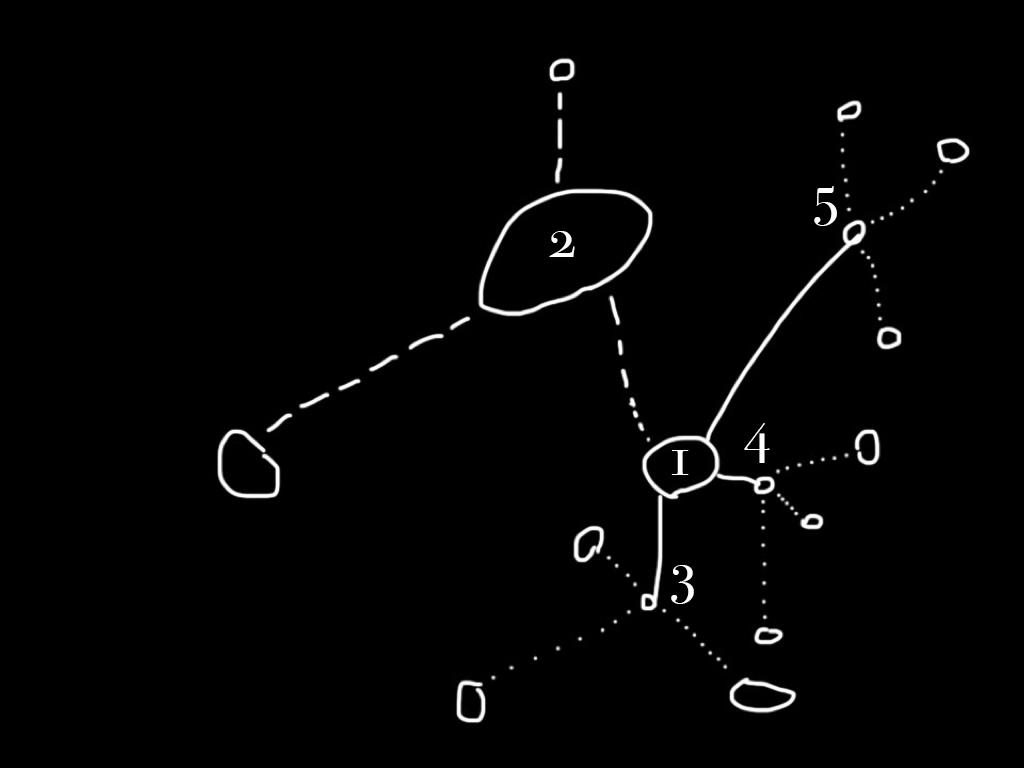

CT: Based on the shape above, we can see that we have three people attending to one person, and each person represents a different quality of concern. In this new model, these three people are not experts or authorities, but people willing to lend attention and to do co-research, to be a scribe, or a living record for the person in the center, the Hologram. We call these three attendees ‘patience’. Our aim is to translate the Workers’ Clinic project to a peer to peer project where the Hologram receives attention, curiosity and long term commitment from the patience looking after her, who are not professionals. Another project using this social technology is called the Accountability Model, by the anonymous collective Power Makes Us Sick.

So the beginning of the process, like that of the Workers’ Clinic, is to perform an initial intake where the three patience ask the Hologram questions which are provided in an online form, about the basic things that help or hurt her social, physical and emotional/mental health. When this (rather extended) process is complete, the Hologram will meet as a group every season to do a general check in. The goal of this process is to build a social and a physical holistic health record, as well as to continue to grow the patience understanding of the Hologram’s integrated patterns.

Ultimately, over time we hope to build trust and a sense of interdependence, so that if the Hologram meets a situation where she has to make a big health decision (health always in an expansive sense) about a medical procedure, a job, a move, she will have three people who can support her to see her lived patterns, to help her ask the right questions, and to support peer research so that the Hologram is not making big decisions unsupported.

But, in order for the Hologram to receive this care without charge and guilt free, she needs to know that her patience are taken care of as she is. I think this is one part of the project that acknowledges and makes a practice built from the work of feminists and social reproductive theorists – you can’t build something new using the labor of people without acknowledging the work of keeping those people alive; reproducing the energy and care we need to overturn capitalism needs a lot of support. Getting support from someone feels so different if you know they are being, well taken care of. This is also how we begin to unbuild the hierarchical and authoritarian structures we have become accustomed to – with empty hands and empty pockets.

And then, the last important structural aspect of the Hologram project is the real kicker, and touches on the mystery of what it means to be human outside of Clientelist Capitalism – that the real ‘healing’ (if we even want to say it!) comes when the person who is at the center of care, turns outward to care for someone else. This, the secret sauce, the goal and the desired byproduct of every holographic meeting– to allow people to feel that they are not broken, and that their healing is bound up in the health and liberation of others.

The viral structure, is built into this system and there is a reversal of the standard way of seeing the doctor and patient relationship. In this structure it is essential that we see the work of the Hologram as the work of a teacher or explicator, delivering a case that will ultimately allow the patience to learn things they didn’t previously know. This is the most important, (though totally devalued by money) potent and immediately applicable, form of learning we can do, and it is what the medical system has made into a commodity, at the same time as it is seen as ‘women’s work’ or completely useless.

MG: Could you take us through the processes of engagement. For instance, you say a group of four people meet and select one person who will become a Hologram, and that this means they and their health will become ‘dimensional’ to the group. Could you elaborate how this happens and why it’s important for those involved?

CT: We are about to experiment, this fall, with what it means for these groups to form in different ways. We will start with four test cases, where an invited, self-selected person will become a Hologram. She will be supported to select three Patience in a way that suits her, based on an interview and survey. The selection of Patience is a part of the process that we have not had a chance to refine. It is not simple for any individual to understand what support looks like for them, or who they want support from, if they’ve never really had it.

The experiments we will work through this fall will attempt to understand what changes in the experience of the whole Hologram when the Hologram is supported by Patience who are trusted friends and family, acquaintances or highly recommended strangers. An ‘objective’ perspective from an outside participant also adds a layer of formality to the project, because, instead of a casual gathering of friends, an unfamiliar person signals to the other members of the hologram to be on time, and make the meetings more structured than a regular friend to friend chat.

The onboarding process for the Hologram and the Patience includes a set of conversations and a training ritual, which are still quite bumpy. The two roles every participant is involved in, requires a different set of skills, and so they both involve a special kind of “training” that one can do in a group or independently. This “training” is a structured personal ritual that allows participants to witness and adapt their own communication habits so that they feel prepared to participate and set up trust, curiosity and solidarity for the group in the opening intake conversations.

At the completion of the intake process, the Hologram (1) transitions to become a Patience. At this time, the Hologram (1) begins a short training to transition to the other role, and she is supported by her Patience to do this work. At the conclusion of the Hologram’s (1) transition to Patience, and the completion of the new Hologram’s (2) intake process, the original Hologram’s (1) Patience become Holograms (3,4,5).

MG: The Hologram project was first trialed as part of an exhibition called Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time at the Elizabeth Foundation Project Space in New York City, March 31-May 13, 2017. What have you learnt in more recent undertakings of The Hologram project?

CT: Since the original trial one year ago, which lasted for 3 months, the research has shifted to looking at building skills and answering acute questions that will accumulate to support and build the larger project. Starting in the Spring of 2017, I began to offer the Hologram project as a workshop, where participants could test the communication model that is implicit in the Hologram format. The method for offering it is, as a performance artist and rogue architect, creating a situation in a space where people go through a difficult psycho social physical experience together. In the reflective conversations that follow, I ask the groups to use the personal pronoun ‘we’ for the entire duration of the conversation. The idea is that one person’s experience can be shared by the group, and even as temporary Patience we can take a leap and share their experience with them for a duration of time, allowing a Hologram to feel as if their experience is “our” experience. And this feeling that one is not alone in an experience, if carried into other parts of life, has the potential to break a lot of the assumptions and habits that we have inherited from living and adapting to a debt driven hellscape.

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

Gannis is informed by art history, technology, theory, cinema, video games, and speculative fiction, expressing her ideas through many mediums, including digital painting, animation, 3D printing, drawing, video projection, interactive installation, performance, and net art. However, Gannis’s core fascinations, with the nature(s) and politics of identity, were established during her childhood in North Carolina. She draws inspiration from her Appalachian grandparents singing dark mountain ballads about human frailty, her future-minded father working in computing, and a politicized Southern Belle of a mother wearing elaborate costumes, performing her prismatic female identity.

“I am fascinated by contemporary modes of digital communication, the power (and sometimes the perversity) of popular iconography, and the situation of identity in the blurring contexts of technological virtuality and biological reality. Humor and absurdity are important elements in building my nonlinear narratives, and layers upon layers of history are embedded in even my most future focused works.” Gannis.

We begin…1. Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

The complete list of people who have inspired me is inordinately long. I’m sharing with you here clusters of some of the “most most” inspiring.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Maya Deren, Lady Ada Lovelace, Mary Wollstencraft – I saw Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Conceiving Ada in the late 90s. It was my first introduction to her work, and

I have been blown away by her prescience ever since. Deren, Lovelace, and Wollstencraft, like Leeson, have all been groundbreaking in their creative, scientific and intellectual contributions to humankind.

Yael Kanarek, Marge Piercy, Octavia Butler, Sadie Plant, Jonathan Lethem, Harry Crews and Flannery O’Connor – Artist Yael Kanarek’s “World of Awe” was one of the first net art pieces, through its poetry and world building, to inspire me to transition from painting into a new media arts practice. Piercy and Butler are two favorite authors, and they have both written novels where women travel into the past and to the future to reconcile their identities, to come to terms with their present selves — themes that constantly recur throughout my work. Plant opened up broad vistas to me as a woman and feminist working with technology, and the melange of genres Lethem mashes up in his fictional works: sci fi, noir, autobiography, and fantasy, appeals to my own hybrid sensibilities. Crews and O’Connor testify to the absurdity of the human condition, and being a native of the “American South,” their gothic sensibilities resonate with me deeply.

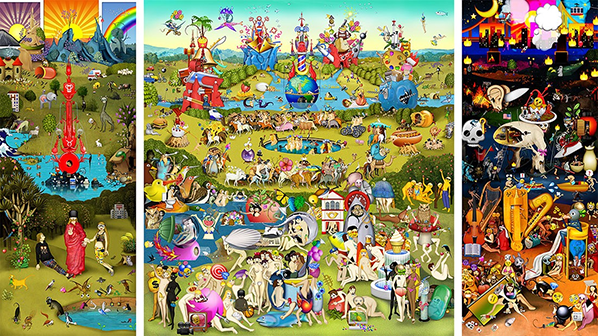

Philip Guston, Suzanne Valadon, Artemisia Gentileschi, Louise Bourgeois, Hieronymus Bosch and Giotto di Bondone – I studied painting at a school where Guston had taught (many years before I arrived there), and coincidentally we share the same birthday. I have always felt a very strong connection to his work, particularly to his late work, where he resisted the art establishment and made pictures that he felt truly represented his time. Valadon, an autodidact, likewise bucked the conventions of 19th century “lady painting” focusing on the female nude throughout her oeuvre. Gentilsechi in the 17th Century established herself as an artist who painted historical and mythological paintings, rendering women with more agency and strength than her male contemporaries. Bourgeois’s work, the rawness of her drawings particularly, were quite significant to me as a young artist. Twice I got to attend her Sunday Salons in New York, sharing my work with her. She was a tough critic by the way. Bosch and Giotto have long been favorites, the enigmatic quality of Bosch’s vision, and the amalgam of Medieval and Renaissance perspectives colliding in Giotto’s paintings.

Charlie White, Laurie Simmons, Gregory Crewdson, Renee Cox & Cindy Sherman – I think of these photographers as important conceptual forerunners of a Post-Photography movement that seems to be reaching its apogee now. They were each essential to me as I searched for a new aesthetic language, after throwing away my oil paints and canvases.

And today there are so many younger artists who I have deep respect for, Gretta Louw, Angela Washko, RAFiA Santana, Jeremy Bailey, Lorna Mills, Andrea Crespo, Clement Valla, Faith Holland, Jacolby Satterwhite, Morehshin Allahyari and Alfredo Salazar-Caro (to name only a few). They all have significant presences online, and I encourage readers to “google them” for glimpses into the contemporary visions that are shaping and predicting our future.”

2. How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

In my teens and 20s I copied much of the work of my sheroes and heroes. There is little I can share with you of that work now, as I’d copy then delete back then. To be more accurate, since it was physical work, I’d copy and destroy. I destroyed more work than I saved until I found a way to absorb and remix through the filter of my own identity.

Today I identify as a visual storyteller who cuts and pastes from the threads of googleable art history, speculative fiction and networked communication in efforts to aggregate some kind of meaningful narrative. Appropriation feels like an authentic artistic response to mediated culture, registering at a different conceptual frequency than simple mimicry. I mean making a painting like Giotto or Bosch doesn’t make sense in the 21st century, well, unless you “emojify” it (wink). Here is one recent work where my quotation is obvious, “The Garden of Emoji Delights.” In the other works below, a collection of influences are embedded, but perhaps less perceptible on first glance.

3. How is your work different from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

It is essential that my work be different semiotically from the historical influences I mentioned above, if I am to actually understand the nature and power of their work — how each of them were incredibly perceptive and responsive to “their time.” They produced authentic images or texts (or code) that were assembled from aspects of their cultural milieu. Their expressions were comprehensible to their contemporaries, even if at times only a few of their peers engaged. Communication is key to every human enterprise. Nonetheless the infinite (and often futureminded) perspectives of these historical figures still reverberate in our contemporary collective consciousness and influence us to “perceive differently” in our own time.

To be different from influences who are of my own time also involves comprehending why they have an impact on me. They avoid any kind of creative and intellectual status quo. Being unique seems improbable in the internet age, but there are still innumerable ways that we can creatively parse our relationships to the past, present and future, both in concert and contrast to one another.

4. Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

There are many art worlds. In the more mainstream, celebrity-dominated, auctioneer enabled art world, whose market I rarely follow, but when I do, I find it to be bloated by One Percenters consumed by commodities trading, I would advocate for, if I had the power to do so, more economic temperance, less aura fetishization, and yeah, VR headsets that provide clothes for hackneyed metaphors.

It’s demoralizing that I cannot foresee, at least in the short term, a world without radical income inequality. Our world continues to be populated by a majority of “have nots” who are dominated by a tiny dominion of “haves.” It seems in every financial, social, educational, and entertainment sector, including the visual arts, capital obstructs as much as it supports creativity. Still I believe that the “other art worlds” can and will affect, actually currently are affecting change (incremental as it may seem), through social advocacy programs that embrace and foster diversity; through economic and technological models that celebrity the ubiquity instead of the scarcity of contemporary digital art; through independent artists who define their success in terms of cultural, instead of, or in addition to market value.

Positive changes are happening. Compare our cultural landscape to even two decades ago, and we see a much more diverse population represented in the arts. A new generation of artists and technologists are hopeful about their capacity to shape a better future, while being mindful of what’s a stake if they do not.

That said, and to finally answer your question directly, I’d like to see a change — a major turn in the tides of fascism, racism, xenophobia, and misogyny that are flooding countries around the world — so that the various art worlds, the ones that frustrate me, and the ones that inspire me, can survive.

5. Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

Sitting with and drawing digital portraits of my 99 year old Grandma Pansy Mae in January of 2015 inspired me to begin “The Selfie Drawings” project. Being in the presence of someone who has witnessed so much radical social and cultural change, over the course of almost a century, motivated me to interpret, and then stage a series of reinterpretations of myself/selves, within the context of a post-digital age. Pansy Mae was a woman born before women had the right to vote in the United States, a woman with only an 8th grade education who raised my mother, and myself to never let our gender or our class (personally) deter us from pursuing our ambitions. Grandma is now 101 years old, and I wished her Happy Birthday in binary code this past December 31st.

“Nasty Woman” is a current meme that has really struck a chord with me. I have worn a “Nasty Woman” necklace everyday, since November 7th, (the day I picked it up from the studio of artist Yael Kanarek). Embracing the nomenclature that was meant to denigrate a woman has instead empowered and galvanized a collective of women as they face, and resist, the alarming possibilities of increased subjugation under Trump’s leadership.

I recently participated in the NASTY WOMEN exhibition in New York city, (which raised over $42,000 for Planned Parenthood), because I am such a woman, a nasty woman, a bitch, a Jezebel — a complex and empathetic human being who believes change and equality can only occur when we speak up, when we eschew “politeness” in the face of serious threats to our autonomy and personhood.

6. What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

I’ve got a few bits of advice. First, as an artist, work; as a technologist, feel; and as an advocate for social change, empathize. Then toss up your FEW cards (feel, empathize and work) and apply them to other aspects of your life as well.

Secondly I suggest losing, if you possess, the sense of what you think you’re entitled to because you are more special and deserving than others. This doesn’t mean you deny the gifts you possess. Nor does it mean you eschew your ambitions or balk at your successes. Brand yourself, or your cause, by all means, if that informs your practice or generates support for your work. But the “I’m a genius, so I have the right to be licentious, egotistical and completely selfserving at the sacrifice of others” trope may (temporarily) get a man into the White House, but generally is tiresome, if not loathsome, to progressive art professionals.

7. Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

What I’ve been reading lately: Object Oriented Feminism edited by Katherine Behar; Artemisia Gentileschi, The Language of Painting by Jesse Locker; Lynn Hershman Leeson Civic Radar edited by Peter Weibel; Hope in the Dark | Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities by Rebecca Solnit; The Year of the Flood by Margaret Atwood

I recommend these books as a resistance to sophomoric twitter threads usurping all of your attention.

Pipilloti Rist : Pixel Forest New Museum, http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/pipilotti-rist-pixel-fores

It is okay for art to wash over you, so that you can revel, even relax, in its beauty…for a while.

____________________________________________________________________

Monster of the Machine : Laboral

curated by Marc Garrett http://www.laboralcentrodearte.org/en/exposiciones/monsters-of-the-machine

A timely and provocative exhibition (thrilled to have work included).

__________________________________________________________________

Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art 1905-2016

http://whitney.org/Exhibitions/Dreamlands

A landmark show for moving image works!

__________________________________________________________________

Women’s March On Washington (Saturday, January 21st!) https://www.womensmarch.com/

…or one of the other 386 protests taking place on the same day around the world!

https://www.womensmarch.com/sisters

#notmypresident

Choose Your Muse Interview: Jeremy Bailey | By Marc Garrett – 26/06/2015

http://furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-jeremy-bailey

Choose Your Muse Interview: Annie Abrahams | By Marc Garrett – 10/09/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-annie-abrahams

Choose Your Muse Interview: Lynn Hershman Leeson | By Marc Garrett – 13/07/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-lynn-hershman-leeson

Choose Your Muse Interview: Stanza | By Marc Garrett – 03/11/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-stanza

Choose Your Muse Interview: Igor Štromajer | By Marc Garrett – 09/06/2015 http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-igor-%C5%A1tromajer

Choose Your Muse Interview: Mike Stubbs, Director of Fact in Liverpool, UK | By Marc Garrett – 20/05/2015

http://www.furtherfield.org/features/interviews/choose-your-muse-interview-mike-stubbs-director-fact

Featured image: Nishant Shah, Roy Klabin, Francesco Warbear Macarone Palmieri, PG Macioti and Liad Kantorowicz

Finally I had the pleasure to attend to a session of the Disruption Network Lab. Physically, let’s say. Even though this was the first time I’ve managed to be in Berlin for one of its events, I’ve been a compulsory virtual follower, watching the videos of their fully recorded sessions. This is a hint for anyone who would like to watch all the previous keynotes and talks.

With its first edition in April, Disruption Network Lab is an ongoing platform of events and research on art, hacktivism and disruption, held at Studio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien, in partnership with Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, in Berlin. On 31st of October it has held its 5th session, PORNTUBES: Sharing the Explicit. Aiming to discuss the role of porntubes in the sex and porn industry it gathered porn practitioners, entrepreneurs, sex work activists and researchers, to engage in a debate on the intertwining of porn with the Internet.

Pornography has always been a pioneer in using new technologies for its distribution and promotion. Internet, by allowing anonymous access to porn from the comfort of everyone’s home it seemed to be the ultimate tool for the porn industry’s expansion, to say the least. As pointed by Roy Klabin during the talk, 38,5% of the time we spend on the Internet is spent watching porn. As in many other spheres, it also seemed to be the beginning of a new era of labour liberation with an apparent decentralisation from the big porn production houses. This has allowed the blossoming of new small and independent companies with their own place in the market. But if cyberspace once seemed to offer a possibility to escape the tentacular control and exploitation exercised by the corporative monopolies, it is now known that the rebellion of the cybernetic innovators – creators of porntubes and new online sex tools – seems to be purely a coup d’etat.

The opening keynote was by Carmen Rivera, a Mistress and Fetish-SM-performer, with a long history in the porn industry business, with an experience of the migration of porn from cinema to VHS and later to the Internet and then onto the porntubes. In conversation with Gaia Novati, a net activist and indie porn researcher, Carmen tells us her personal and professional story and immediately gives a better understanding on how porntubes – such as Redtube, X-Hamster or Youporn – have an ambiguous influence in the porn industry. Once perceived as a democratic tool allowing small porn producers to expand their radius of audience-reach, Rivera explains how much of a perverse tool of exploitation it has become and one that small producers have become too dependent on.

The fast pace of the Internet creates a lot of pressure to satisfy the hunger of porn consumers. As has become virtually infinite “fast-porn” is closely aligned with the capitalist paradigm of production, putting a bigger focus on quantity rather than quality. As the Internet leaves no space for durability — one day you’re in, the next day you’re out — careers become frail, the work of these companies are highly precarious and the concept of the “porn-star” is a short lived mirage.

Rivera also highlights how online piracy has become virtually unavoidable resulting in gigantic losses to the porn industry. As producers see their films ending up on porntubes free of access, lawsuits don’t come as a viable solution but as financial black holes for any small or even medium companies. Even though the future doesn’t seem bright, Rivera doesn’t quit. Her battle cry: we need to create a bigger awareness of the pestilent system that controls the online porn industry. New tools of disruption need to be found to fight against these new power asymmetries established through the domination of cybernetic capital.

After the keynote, the discussion shifted to examining new tools of online sex work such as the project PiggyBankGirls, self-proclaimed as the first erotic crowdfunding for girls. Unfortunately, Sascha Schoonen, CEO of the project, wasn’t able to attend. Instead a short promo video was presented introducing the project, giving some tongue-in-cheek examples on how girls could profit from this crowdsourcing tool.

Women upload videos pitching their ideas or projects – financing a shelter for stray animals, the payment of tuition fees, a trip to Japan, – and then share online porn performances in exchange for support from “occasional sugar daddies”. Although one wonders if this isn’t just a euphemism – a sanitised version, let’s say – of already existing tools used by women who need money, regardless of them making public how they intend to spend money Nevertheless, it is true that the actual exploitative system needs to be dismantled, workers should be getting a bigger share for their labour and PiggyBankGirls poses as one more tool to do so, however this project also left many unanswered questions. Who are actually the women who can profit out of it? PiggyBankGirls promo tries to make this form of sex labour sound “cute”, easy and accessible. However, is just another tool for established porn actresses to diversify their means of income?

The panel, moderated by Francesco Warbear Macarone Palmieri, socio-antrophologist and geographer of sexualities, included abstracts showing a wide array of perspectives on the issue of porntubes and online sex work. The researcher Nishant Shah opened the panel with a wonderful talk ranging from porn consumerism to porn politics and how porn is influencing our digital identities. In a porn-consuming society, from establishing clear distinctions between “love” and “porn”, respectively meaningful and perverse, desirable and visceral desire, porn seems to be contingent on the morals of the spectator – as it only exists through the spectator it has also become a tool of puritan regulation. From Facebook teams of censorship and sanitisation of the virtual space to websites such as isitporn.com it is possible to understand that the concept of porn becomes itself a regulator of our sexual expressions, defining the line that separates decency from indecency. Paving the way to the pathologization of porn practices but yet dictating the meaning of authentic sexual performances, as the only visceral forms of sexual performances available, Shah pointed out how pornography, as a cultural and digital artefact, works in the regulation of our societies and in the production of our identities. Giving the example of Amanda Todd, who committed suicide after suffering from bullying for exposing her sexual body online, Shah shows how new forms of “porn” take place in the digital, from doxxing to unintended porn being perceived as such, enabling new forms of violence – let’s say porn-shaming.

Also focusing on porn consumerism, Roy Klabin, investigative documentarist/filmmaker, goes back to the discussion initiated with Carmen Rivera on porntubes VS porn producers and how producers make money. According to Roy, MindGeek, the company that owns most of the porntubes – from Youporn to Redtube – has been one of the main entities responsible of the destruction of the porn industry. By creating piracy websites holding gigantic libraries of free access to porn and making revenue out of the advertisement, resulting in huge losses for the porn companies which at the same time had become dependent on the tubes to advertise their work. Roy makes an appeal to porn producers to diversify their strategies: from webcams to virtual reality, the porn industry needs to be one step ahead of the contemporary systems of digital exploitation.

PG Macioti, a researcher and sex workers rights advocate and activist, together with Liad Kantorowicz, performer and sex workers’ activist, presented an overview on how the Internet has reshaped sex work – from sustainability to work conditions – listing some of the outcomes, pros and cons, of the extension of sex work to the virtual spaces. Online sex work, namely erotic webcam work, has enabled a proliferation of sex work by offering safe, independent and anonymous services. On the other hand with the insertion of sex work on the capitalist mode of production, just like in many other forms of digital labour it has rendered a bigger alienation to the workers – who work mainly alone and, also due to stigma, don’t share any contact with fellow colleagues – resulting in a more and more precarious labour, with sex workers being paid by minute, having to pay for their own means of production and usually paying a big share of their income to the middleman webcam services host agency.

Overall, the Internet has enabled a multiplication of narratives on sex work but the power asymmetries between the online corporations and workers results in a growing exploitation and precariousness. The transversal message to all participants seems to urge for disruptive tools for online sex work, tools of self-empowerment and emancipation within the digital paradigm. Quoting the Xenofeminism manifesto by Laboria Cubonics, “the real emancipatory potential of technology remains unrealised” and the Disruption Network Lab might be the much needed spark for this revolution.

The PORNTUBES event couldn’t have had a better ending with a party held in the legendary KitKatClubnacht, a sex & techno club that is open since 1994, famous for both its music selection and its sexually uninhibited parties. It seems an exciting idea, to say the least, to bring all together researchers, porn entrepreneurs and activists to this incredible venue after an intense afternoon discussing the porntubes.

Concluding the series of conference events of Disruption Network Labs during 2015, the next event will be STUNTS: Distributed, Playful and Disrupted, taking place on the 12th of December, at the Studio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien, and the direct link is: http://www.disruptionlab.org/stunts/. This time the discussion will focus on political stunts as an imaginative and artistic practice, combining hacking and disruption in order to generate criticism of the status quo. As the immense dragnet of state-surveillance extends it becomes imperative to understand which are the available tools of obfuscation, how it is (still) possible to hack the system and which tools of political resistance can be deployed Disruption Network Lab wraps the year with a tempting offer, inviting artists, hackers, mythmakers, hoaxers, critical thinkers and disrupters to present practices of mixing the codes, creating disturbance, subliminal interventions, giving raise to paradoxes, fakes and pranks.

Body Drift: Butler, Hayles, Haraway (Posthumanities)

Author Arthur Kroker. University of Minnesota Press (22 Oct. 2012).

Body Drift by Arthur Kroker, takes the work of three leading women thinkers as its main focus. It therefore would feel strange, before venturing on to the review, not to mention Marilouise Kroker, his wife and collaborator who he credits with shaping the critical direction of his thought “on bodies and power.” [1] Together Marilouise and Arthur Kroker have created an abundance of work in the fields of technology and contemporary culture. They both edit the peer publishing electronic journal CTheory founded in 1996. They co-authored the influential Hacking the Future (1996), and Marilouise Kroker has co-edited and introduced numerous anthologies including Digital Delirium (1997), Body Invaders (1987), and Last Sex (1993) and Critical Digital Studies: A Reader. Marilouise Kroker is Senior Research Scholar at the University of Victoria. A recent bio written about them says “Arthur and Marilouise Kroker are the hipsters of Canadian media theory.” [2]

Arthur Kroker is Canada Research Chair in Technology, Culture and Theory, Professor of Political Science, and the Director of the Pacific Centre for Technology and Culture (PACTAC) at the University of Victoria. His recent publications include The Will to Technology and the Culture of Nihilism: Heidegger, Nietzsche, and Marx (University of Toronto Press) and Born Again Ideology: Religion, Technology and Terrorism. Dr. Kroker’s current research focuses on the new area of critical digital studies and the politics of the body in contemporary techno-culture. http://web.uvic.ca/~akroker/

This review is written three years after the publication of the book but it feels even more relevant now than ever for reasons that will, I hope become plain…

Body Drift focuses on three major feminist theorists, Judith Butler, Katherine Hayles and Donna Haraway. They have had a deep influence on my own work and of course on media art culture through the years. They have profoundly altered our views on technology, feminism, queer theory, postmodernism, marxism, hacking, hacktivism, cybernetics, the Internet, network culture, politics and posthumaniism. Re-examining their critical perspectives and creative processes – assemblages, remixing and cyborgs- Kroker terms the emerging technological spectre body drift. He examines the connections between what he sees as Judith Butler’s postmodernism, Katherine Hayles’s posthumanism, and Donna Haraway’s companionism.

Through the spectrum of Body Drift he attempts to find a clearer understanding of the contemporary material body and its societal complexities. He views two opposing forces at work in body drift. One is, the continual disappearance of human things and values, alongside excluded ethnicities and outlawed sexualities. He connects this with an entrapment by social crisis in which actual democratic aspiration is dwindling. In parallel to this mass loss of our freedoms other factors are at work. He sees it as overall, and an eventual series and states of resistances. These are evolutionary forms of hybridity and as such are key paths for what he argues is the function of our posthuman condition. [3]

There are numerous techno-visions expounding how technology will change our lives and futures. What for me, separates a classic posthumanist and a critically aware posthumanist is that the latter is not only aware of the necessity of grass roots culture and inclusion of female voices, but is also critical of domination over others as key when engaging in the processes of innovation. Thus moving beyond existing frameworks that perpetuate patriarchal language, methods of centralization and colonial habits.

In his book You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto, Jaron Lanier described Ray Kurzweil’s excitement about The Singularity as apocalyptic. Lanier says “The coming Singularity is a popular belief in the society of technologists. Singularity books are as common in a computer science department as Rapture images are in an evangelical bookstore.” [4] Kurzweil’s digestible techno-bites fit well alongside big business and with Peter Diamandis a wealthy entrepreneur. Dr. Peter H. Diamandis and Dr. Ray Kurzweil co-founded the Singularity University. In To Save Everything, Click Here: Technology, Solutionism, and the Urge to Fix Problems that Don’t Exist, Evgeny Morozov writes that Diamandis “promises us a world of abundance that will essentially require no sacrifice from anyone – and since no one’s interests will be hurt, politics itself will be unnecessary.” [5]

In The Joy of Revolution Ken Knabb wrote, “Marx considered it presumptuous to attempt to predict how people would live in a liberated society. “It will be up to those people to decide if, when and what they want to do about it, and what means to employ.”” [6] Kroker says, “In my estimation, while Marx, Nietzsche and Heidegger may have provided premonitory signs of the charred landscape of the technological blast, it is the specific contribution of Butler, Hayles and Haraway to provide a deeply compelling account of the fate of the body in contemporary society.” [7] This includes how we evolve our Internet freedoms, surveillance, and cyber attacks in a post-Snowden world. While we’re, either reshaping or being reshaped through the constant production of new technologies and political re-invention, it is crucial that there exists regular critique reflecting on these influences and changes on people, animals, society, the planet, and the universe. Thankfully, Butler, Hayles and Haraway disrupt the normalization and dangerously hegemonic acceptance of ‘the male overlord and his machine’ over the rest of us.

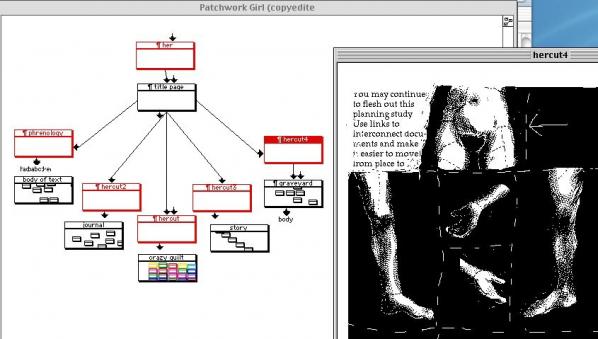

How our bodies and the idea of our bodies relate to this complex world is Kroker’s primary interest. In the introduction Kroker says that we no longer inhabit a body in any meaningful sense of the term but rather occupy a multiplicity of bodies – imaginary, sexualized, disciplined, gendered, laboring technologically augmented bodies. [8] Hayles has not only bridged the gap between science and literature, but also media art. In 2000, Hayles wrote an insightful piece on Patchwork Girl, an artwork made by Shelley Jackson in 1995, a hypertext fiction and remix of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. When discussing Jackson’s piece Hayles said, “As the unified subject is thus broken apart and reassembled as a multiplicity, the work also highlights the technologies that make the textual body itself a multiplicity.” [9]

Kroker says, “”Like Heidegger before her, Hayles refuses to privilege either interpretation to the exclusion of its opposite, preferring a form of thought similar to “pendurance,” that moment when, in the folded twists of complexity theory, “one comes over the other, one arrives in the other.”” [10] In an interview with Josephine Bosma on the Nettime email list, in Nov 1998, Hayles said “There may be other ways to think about the subject that don’t find themselves first and foremost on this notion of ownership. New technologies open up possibilities for rethinking other ways to begin to construct the subject.” [11] Krokers sees Hayles as providing us with the digital alphabet to explore the complexity and connections of technopoesis. “To read Hayles is, in fact, to begin to experience the fractures, bifurcations, and liminality that stretches across the skin of posthuman culture.” [12]

Donna Haraway in her introduction to A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century, in 1985 she said, “Though both are bound in the spiral dance. I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess.” This unsettled many feminists at the time. Haraway was not interested in reclaiming what she saw as a lost ideal based on matriarchal values. Instead, she wanted women to re-invent and create their own versions of what a female could be or not be, by playfully exploiting the cyborg myth and concept in the here and now. [13] This reconstruction of the woman, Kroker says, poses particular twists and knots, and contradictions. He emphasises that we’re not discussing a traditional form of feminism but a hybrid vision of feminism. [14]

“Not waiting passively for the capricious experience of biotechnology to produce spliced bodies, Haraway has made of her own mind a biopolitics on creative hyperdrive. Deeply immersed in the (bio)scientific disciplines, always distancing herself from seductions of technological representationality by feminist difference, continuously provoking boundary breakdowns in her own thought by refusing to assent to an anthropomorphic species-heirarchy, Haraway is a theorist of the splice.” [15] Kroker (2012)

Kroker moves on from Haraway’s concepts on the cyborg to her later inter-species theory. He tries to untangle the complexity of her personal, political and theoretical relations in respect to where her critical strength is best engaged. He’s drawn to what he sees as ““Haraway’s profound conceptualization of “companion species.”” Haraway challenges the established role and hierarchical control by us humans over animals, plants, objects, and humans. [16] In her publication The Companion Manifesto: Dogs, People, And Significant Otherness, Haraway says, “I believe that all ethical relating, within or between species, is knit from the silk-strong thread of ongoing alertness to otherness-in-relation.” [17]

Haraway’s text in The Companion Manifesto conveys a shocking sense of freedom as if written by someone who longer gives a damn about her academic reputation. Perhaps, what I mean here is that the thinking reaches further than academia and builds alliances with others who may not have read her other works. In the chapter A Category of One’s own, Haraway says, “Anyone who has done historical research knows that the undocumented often have more to say about how the world is put together than do the well pedigreed.” [18] As with her concept for Situated knowledges her intention is to connect beyond officially accepted canons and norms, and established hegemonies. In his chapter HYBRIDITIES Kroker says “Haraway’s writings reveal the apocalypse that is possibly the end condition of hundreds of years of (Western) scientific experimentalism.” [19] This does not mean the West is doomed. However, Haraway has always been on the side of otherness, whether for humans or nonhuman entities. In her eyes our futures or the world as it actually is may not necessarily be as reliant on technology as we like to think.

“Perhaps most importantly, we must recognise that ethics requires us to risk ourselves precisely at moments of unknowingness, when what forms us diverges from what lies before us, when our willingness to become undone in relation to others constitutes our chance of becoming human.” [20] Judith Butler.

Of this quote from Butler’s Giving an Account of Oneself, 2005 [21], which opens the second chapter in Body Drift, Kroker says, “Could there be any text more appropriate to both understanding and perhaps, if the winds of fate are favorable, transforming contemporary politics than Judith Butler’s eloquent study of moral philosophy..?” [21] In Giving an Account of Oneself, Butler presents us with an outline for a different type of ethical practice and proposes that, before you even ask what ought I to do? Ask yourself the question who is this ‘I’? Butler, proposes that it is “a matter of necessity” that every person should “become a social theorist.” [22] Indeed, in the City Lights interview with Peter Maravelis, Kroker says Butler is speaking in terms of people breaking their silence, such as “the repetition chorus of OCCUPY during the Wall Street insurrection”. [23] And then he says, “In many ways, all of Butler’s thought is “standing as witness.” [24] Butler stands witness to what we now know in the 21st century as a violent regime of heterosexual masculinity spreading its domination over history, technology and life itself.

Butler, Hayles and Haraway are major players in feminist and queer academia and media art culture. They have all been active in breaking away from the traditional behaviours that have kept us caught within loops in various ways. Their fluid and progressive approaches to feminism are not only of value to women alone but it can also help others think beyond restrictive behaviours. Kroker’s book manages to reflect the fluidity of networked and contemporary aspects of body drift well, especially from a critically aware, posthumanist perspective. However, no matter how you slice it, it’s about personal and collective freedoms, how we can somehow reclaim our states of being, and how we can own our subjectivities and our psyches in whatever forms these may take. As artists, as humans and or as posthumans – we need Butler, Hayles and Haraway to guide us through this ever-changing, twisting, everyday, posthuman terrain.

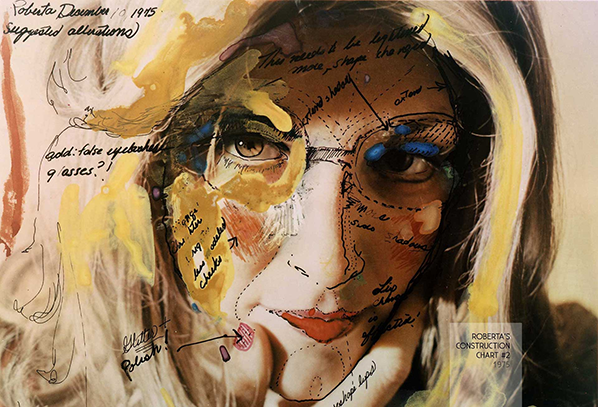

Featured image: External Transformations: Roberta’s Construction Chart, No. 1,from the series Roberta Breitmore, 1974–78

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

Lynn Hershman Leeson artist and filmmaker, who over the last three decades, has been internationally acclaimed for her pioneering use of new technologies and her investigations of issues that are now recognized as key to the working of our society: identity in a time of consumerism, privacy in a era of surveillance, interfacing of humans and machines, and the relationship between real and virtual worlds. Her work was featured in “A Bigger Splash: Painting After Performance” at the Tate Modern London in 2012 and a retrospective and catalogue are being planned for 2015 at the Zentrum fur Kunst Und Medientechnologie, Germany. Modern Art Oxford is hosting a major solo exhibition of her work Origins of a Species, Part 2, and it’s open until 9 August 2015.

Lynn Hershman Leeson released the ground-breaking documentary !Women Art Revolution in 2011. It has been screened at major museums internationally and named by the Museum of Modern Art as one of the three best documentaries of the year.

The image above is from !Women Art Revolution, which introduces the Guerilla Girls who draw attention to injustice and under-representation across artistic platforms and institutions. Several members discuss their origin story and modus operandi, including “the penis countdown. !Women Art Revolution won the first prize in 2012 at the festival in Montreal on Films on Art.

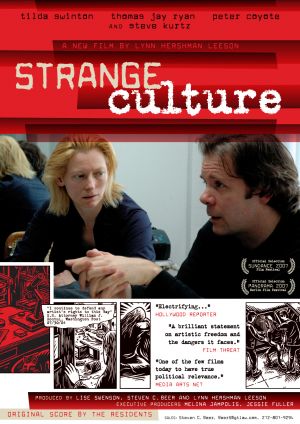

She also wrote, directed, produced and edited the feature films Strange Culture, Conceiving Ada, and Teknolust. All featured Tilda Swinton and were showcased at the Sundance Film Festival, Toronto International Film Festival and Berlin International Film Festival before being distributed internationally. After her retrospective, at CIVIC RADAR in December 2014, a bumper catalogue consiosting of 450 pages will be published in Oct 2015. Featuring writing by Peter Weibel, Laura Poitras, Tilda Swinton, Kristine Stiles, B Ruby Rich, Hou Hanru, Andreas Beitin, Peggy Phelan, Pamela Lee, Jeffrey Schnapp, kyle Stephan and Ingeborg Reichle. Civic Radar is now at Diechterhallen Falkenberg till November 19, 2015.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Lynn Hershman Leeson: What has inspired me are people who work with courage to do original work that has a political and authentic ethic. These include, to name a few only, it seems a bit strange because naming them isolates these artists from the context of their contributions. But I have been inspired by Lee Miller, Mayakovsky, Tinguely, early Automata and so many more like Thomas Edison, Jules Etienne Marrey, even Cezanne. Early on I educated myself by copying works to get a sense of how particular artists formulated their language – the way Rembrandt used light, Leonardo’s draftsmanship and parallels he found between technology and science, Gauguin’s color reversals, Brecht, Breton and Duchamp’s ironic and iconic archetypal identities, Tadeauz Kantor, and Grotowsky’s extension of the frame.

Also younger artists (nearly everyone is) like Rafael Lezano Hemmer, particularly the work he is doing now in using facial recognition to locate kidnapped victims, Amy Siegal’s Providence, Janet Biggs, Annika Yi, Nonny de la Pena, Tania Bruguera, Ricardo Dominguez, and many many more.

![Lee Miller photographed women in fire masks in wartime London in 1944. [Source: Telegraph/Lee Miller Archives]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/lee_miller_fire_masks_1944.jpg)

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?