Recently I was approached to conceive and run an outreach project to accompany a solo show of work by Eduardo Kac at Furtherfield Gallery in North London’s Finsbury Park.

Among the works on show was one of Kac’s Lagoogleglyphs, large scale stylised representations of rabbits (something of a signature obsession for him) painted in some sort of sportsground emulsion directly onto a section of the park and allegedly of a scale which make it harvestable by the satellites Google rents for its various mapping activities.

Being completely frank, I have to say I entertained a degree of scepticism about Kac’s work—some of it falling within, in my view, one or both of two entertainment based metaphors—the ‘one-liner’ and the ‘theme park’—neither particularly positive elements of my critical lexicon.

Be that as it may, some of the work, particularly the less grandiose pieces (that delicate bunny flag flapping above the gallery!) were touched enough with real poetry to make me want to take up the challenge.

I say ‘challenge’ advisedly for I’m only ever interested in doing anything which in some sense challenges me and I also felt that my ambivalence about Kac would result in anything I ended up making containing a return element of ‘challenge’ or, perhaps more gently put, practical critique.

The word challenge also described the sense I had of wanting to counterpose collaboration, the collective, the everyday, to the artist with a capital ‘A’; of going some way to claiming art as a way of seeing and feeling and thinking together for All ( also with a capital ‘A’).

Reaching back in memory I pondered two remix/homage projects from the noughties which somehow straddled, in a pleasantly clunky fashion, practices both cutting edge digital (at least in their original moment) and time honoured too.

Apposite and practical stimuli for my 2018 purposes, they suggested elegant pathways to both honour previous work and to gently…um… stress-test it.

Both evinced rich humour, a warmth and a concomitant refusal to take themselves too seriously, qualities lacking in much contemporary art and both had a kind of performative klutziness I found entirely engaging.

Both were made in the first years of this millennium when digital and particularly online art was a wild west with a few fragile homesteads scattered here and there and not the orderly space it is today colonised almost entirely by the mainstream art world or commerce or both.

I recalled first a project by Nathaniel Stern where he hired South African billboard sign writers to paint physical representations of various, mostly art related, web pages.

The second was artist duo MTAA’s remix of Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance project, an endurance piece where Hsieh had forced himself to punch a timeclock on the hour, every hour for a whole year.

Reversing the premise MTAA’s Whid and River posted a database of video clips of themselves sleeping, eating, inhabiting the space and left it to the online viewer to watch these being digitally assembled (by Flash—remember that?) into a simulacrum of the original over the assumedly continuous period of a year.

Armed, fortified, prepared thus, I set to work—but I still needed a concrete plan and methodology.

Being a keen runner and the project taking place in a London Park in which I had run a 10k not long before (and now having endurance floating near the top of my mind) I felt some kind of park related physical activity would be an element and this would be a way of coming closer to those who loved the park but for whom the art gallery might not be their first association.

But still I lacked the concrete rabbit themed activity which would offer genuine practical, meaningful and autonomous artistic engagement and creation to participants.

I did not want to control what those participants would do but give them a clearly defined (clearly defined enough that all inputs from three separate days of activity could be brought together into a final unified work) and interesting task within which they would need to deploy creativity, focus and skill.

The fad for exercise related GPS devices had previously passed me by but one day whilst running with my daughter, who uses her phone and GPS enabled software to document her running in data and map form, I had a small epiphany—here there (might) be rabbits.

Rabbits, giant GPS rabbits, first planned and sketched by participating teams in marker pen over a satellite image of the park—ears, eyes, paws, body, fluffy tails emergent within its various paths and trails and features and obstructions.

And then, using these maps, we would carefully and attentively walk-out each monster rabbit trapping and freezing it as a succession of data, a series of co-ordinates in the memory of the GPS watch I would wear, finally to be reconstitututed as a continuous line drawing in turn fed back into a fresh satellite view of the park.

But that succession of co-ordinates, actuated by the actual movements of the human body (like a giant pencil lead or nib or brush) will resolve itself into something ancient—line, preconceived and then drawn out by human beings.

Being, together, both the very oldest form of mark making and something blink-of-an-eye recent too (well, as recent as the noughties efflorescence of so-called locative media which I shamelessly pillaged here.)

Inaccuracy in some measure a feature of both ancient and modern—the error margin of even GPS and GLONASS together, two sets of four satellites working in concert; the mix of will and skill and the fallibility and triumph too of flesh and bone and sinew which is part of what thrills and moves us in the arts.

This is what I had in mind.

Repeatedly outlining then co-performing an activity which I learned to summarise simply and precisely, almost automatically, one might have thought boredom or a dozy, parroted, routine might threaten.

And how anxious I was each time as to whether and in what way each new team would engage with—buy into—adopt as theirs, as ours—the task.

But how striking the variation both in the simple, basic act of depicting in continuous line each new rabbit-of-the-imagination and the forty minutes lively sociability surrounding that initial sketching and subsequent walking-out.

Balancing the competing claims of making something serious, something with some kind of weight, some satisfying end product, whilst making space for others’ fun and dreams and and will and whimsy is neither easy nor is it trivial.

In the end people seemed to have a good time, they seemed at ease, went at it with a will and—it seems to me—something rich and affecting emerged.

Thanks to all at Furtherfield and thanks—no, not thanks, but credit—to my fellow artists: Alessandra, Anna, Candy, Chris, Elliot, Evgenia, Franc, George, Grace, Henry, Jade, Lenon, Léonie, Lucian, Luka, Martin, Matthew, Maya, Negev, Niyah, Pryle, Rémi, Rosalie, Sara, Shiri, Stefan, Thea and Tyler.

A recent report on digital attitudes shows that while 50% of people in the UK say that the Internet has a positive impact on their lives, only 12% believe it has a positive impact on society.[1] Mark Zuckerberg’s recent failure to give a straight answer to questions about misuse of Facebook’s user data, illustrates a major problem.

Much has been made of the democratising effect of social media platforms. However, while more of us are encouraged to “have our say”, we have less influence over the important decisions that most affect our lives, our localities, and the ways in which our societies are organised. The owners of digital platforms from Facebook to Uber, answer to shareholders in private, rather than to citizens in public. It should therefore not surprise us when they manipulate, monetize and exploit users’ interactions, attitudes and behaviours for their own commercial and political interests.

This problem of privately owned social space is not one that can be resolved by consumer and state regulation alone. It is a wider societal issue that further reinforces to us at Furtherfield, the immense value of park spaces in which neighbours come together each day, renegotiating in public, the spirit of the place through a diverse mingling of purposes.

Over the last six years more than 50,000 people have encountered over 75 digital artworks that Furtherfield has brought to the park, working with international artists who reveal the invisible forces at play in machine and digital infrastructures. This summer Furtherfield extends its programmes beyond the Gallery and Commons venues into public green space of the park as we announce the first exhibitions, workshops and labs as part of Platforming Finsbury Park.

We are inviting park users to collaborate with us to transform the park into a public platform for cultural adventures, social inventions and reflections; to work with artists, hackers and academics from all backgrounds to rethink the social impact of technology and its flows on public spaces; and to bring local needs to the forefront in the context of planetary-scale techno-social advancements.

Currently showing at Furtherfield Gallery in the heart of Finsbury Park is the exhibition Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens: the Art of Eduardo Kac which is free and open to the public every day through May. The exhibition includes Lagoogleglyph, the third in a series of images as part of a global, networked artwork that takes the form of a pixelated bunny painted (in this instance) onto a field in the park, to be enjoyed by people on the ground and seen from Google Earth. In his essay Andrew Prescott, curator of the exhibition and Professor of Digital Humanities at Glasgow University revisits historic antagonisms between culture and technology prompted by reflections on the invention and imagination at play in Kac’s digital poetry.

Meanwhile families are joining artist Michael Szpakowski to use the very same satellite infrastructure to create GPS bunny drawings in his workshop series Let’s Fill the Park With Rabbits!

We hope that Platforming Finsbury Park will also start to flip some assumptions about who and what both art and technology are for. Over 180 languages are spoken in Finsbury Park. We want to make space for conversations and experiments with people from different backgrounds. Alongside the exhibition Andrew Prescott is also leading a series of public workshops on the theme of Digital Transformations promoting dialogue between and across diverse cultures.

In late May, we host Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival, a 3 day lab for artists, scientists and technologists dedicated to “the worker in an age of data and neurotechnologies”. From these will flow art commissions and collaborations towards our next exhibition in July.

Here you can read an interview with designer Ling Tan about the SUPERPOWER wearable technology workshops at Furtherfield Commons last summer in Finsbury Park. Ling tells us about how a group of young women from All Change Arts worked with her to devise activities and to learn about creating and interpreting data to themselves shape attitudes and behaviours. Dani Admis, curator of Playbour, continues this work later in the summer, exploring with local young women how they might effect change on their own terms, using the conceptual power tools of neuroscience.

Finally a provocation to Furtherfield from Simon Poulter, artist, technologist and producer of NetPark, the digital art park at Metal in Southend, who is working in partnership with us. He celebrates our commitment to the commons “as a real thing, worth our energy and stewardship, the point at which people do touch each other and listen.” He also issues a call to action…“It is time to invent another future, lest we will become the disrupted and not the disruptors.”

As Manuel Castells famously put it ‘The flows of power generate the power of flows, whose material reality imposes itself as a natural phenomenon that cannot be controlled or predicted… People live in places, power rules through flows’. [2] And in network society these flows often have the power to wash clean away communities’ ties, extracting value and flowing it to the private interests of absent and distant persons and bodies.

So our future mission grounds us in Finsbury Park, while maintaining our global reach. We are passionate and committed to multiple points of entry, bringing in consenting and diverging voices, to channel and circulate flows locally to generate the power to enact this public place together with verve.

Much of our cultural history of the past two hundred years has been defined by anxieties about the growth of a technological and commercial society. In the nineteenth century, Samuel Taylor Coleridge bewailed ‘the philosophy of mechanism which, in everything that is most worthy of the human intellect, strikes Death’, while Matthew Arnold declared that ‘Faith in machinery is our besetting danger’. For such commentators, culture represented a means of staving off the threat of an industrial society ruled by money and commercialism.

It is easy to fall into a false binary of opposition between art and technology. When pioneering artists and scholars first demonstrated the potential for using computers in arts and humanities research in the period after the Second World War, their work often provoked antipathy because of this anxiety to maintain a distance between art and the machine. In my inaugural lecture at King’s College London in 2012, An Electric Current of the Imagination, I argued that artistic practice offers a particularly effective means of fostering a creative and critical relationship between art and technology. I declared that ‘Such a new conjunction of scientist, curator, humanist, and artist is what the digital humanities must strive to achieve. It is the only way of ensuring that we do not lose our souls in a world of data’.

Since 2012, I have held an AHRC fellowship as Theme Leader Fellow for its strategic theme of ‘Digital Transformations’. One important outcome of this theme has been further exploration of the way in which artistic practice offers innovative perspective on our relationship with technology. Artistic experiments with a range of text technologies from the typewriter to the computer provide exciting insights into the materiality of the text and the way in which text interacts with our senses as readers and writers.

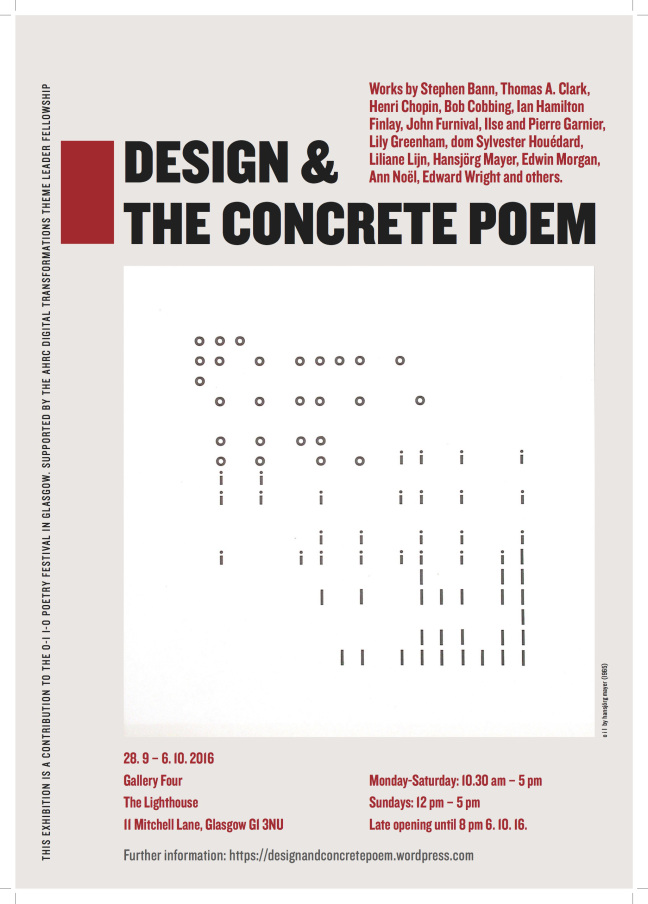

One event held under the auspices of my fellowship which seemed to me to encapsulate these possibilities was an exhibition, Design and the Concrete Poem, curated by Bronac Ferran at the Lighthouse Gallery in Glasgow from 28 September – 6 October 2016. This exhibition introduced me to the work of many artists whose exploration of the materiality of text and poetry I found compelling.

Design and the Concrete Poem introduced me to such reinventions of the text as dom Sylvester Houédard’s experimentation with typewriters or Liliane Lijn’s use of letraset on metal drums to create Poem Machines. The way in which Lijn’s exploration of Dickensian engineering workshops in London in the late 1960s inspired her Material Alphabet (1970), and her fascination with industrial processes and images, epitomises the way in which artistic practice can generate creative conjunctions with technology. Pierre and Ilse Garnier’s poem cut on a Gestetner duplicating stencil, shown for the first time in the Glasgow exhibition, offered both a novel view of textual materiality and an elegy for an obsolete technology.

One artist whose work I have found consistently helpful in thinking about the interaction between technology, communication and our human condition is the Chicago-based Eduardo Kac (b. 1961), and I am delighted to have helped arrange at Furtherfield his first UK show, Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens.

Poetry is challenging. A poem questions our certainties, makes us see the world from different angles and, by encouraging us to pause and reflect, subverts that mechanistic goal-oriented outlook which so horrified Coleridge and Arnold but nevertheless dominates the modern world. Technology can give words and letters new shapes and resonances and, in so doing, subvert a consumer-oriented view of technology.

There can be no more imposing expression of technological achievement than the International Space Station. One of the most fascinating aspects of the video of Eduardo Kac’s space poem Inner Telescope, performed in 2016 by the French astronaut Thomas Pesquet, shown in the Furtherfield exhibition, are the interior shots of the cramped space station, jam-packed with wires, containers and panels from innumerable scientific experiments. The confined space station contrasts with the expansive views of the earth visible through the space station windows. This contrast itself seems like a commentary on the puny character of human technological ambitions.

Kac proposed the idea of space poetry in 2007. He pointed out that weightlessness would affect the temporal and physical logic of a poem, while the readers’ sensory engagement with the act of reading would also be different under zero gravity. Inner Telescope vividly illustrates how a simple performance such as cutting paper may be different in zero gravity, while the movement of the paper (cut into a form representing the word ‘Moi’) seems to epitomise the fragility of textual communication. In the rigidly scheduled life of the space station, Inner Telescope uses poetry to pause and reflect on the complex interrelationship of humanity, technology and the wider universe.

One major thread of Kac’s art has been the relentless interrogation of technology to create radical and original poetic visions. Kac experimented with the potential of the typewriter to allow different juxtapositions and textual shapes in his Typewritings of 1981-2 and from these experiments sprang his first digital poem, Não! (No!) , in 1982-4. Não! was presented on an electronic signboard with an LED display with fragmentary text blocks, encouraging the reader to guess at the links between them.

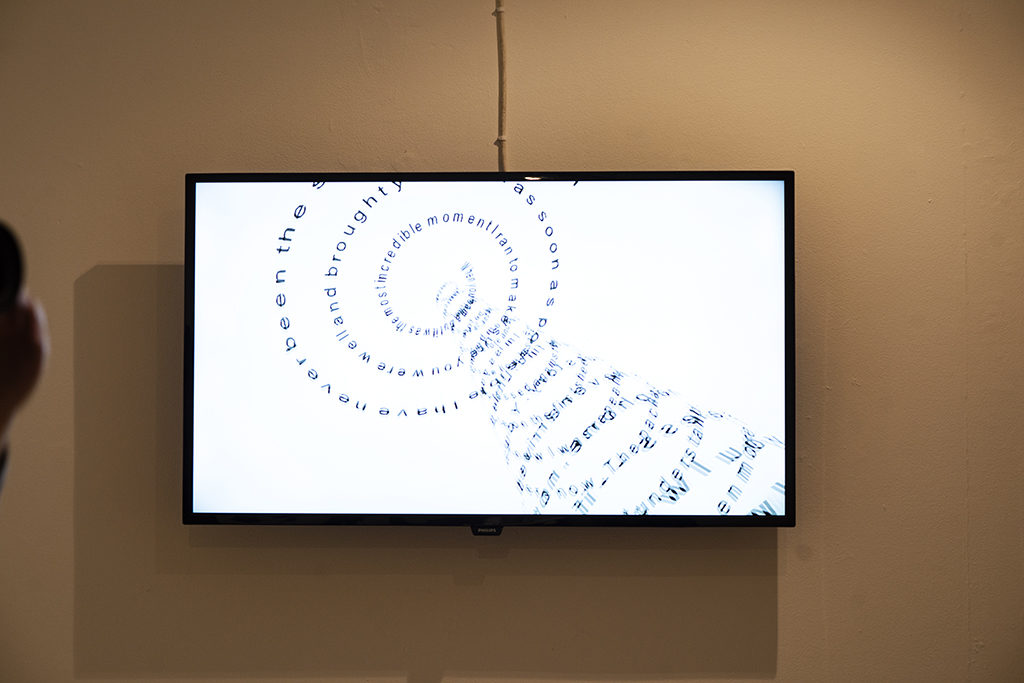

The digital poems shown in the Furtherfield exhibition illustrate how Kac makes use of digital technologies to redefine the relationship between the reader and text and to reveal new poetic elements in short words and phrases. In Accident (1994), a digital loop introduces shifts and uncertainties into a text, recalling the nervous hesitation when two lovers meet, but also causing the reader’s perception of the text to change as the piece progresses.

Another remarkable pioneering digital poem on display at Furtherfield, Letter (1996), uses virtual reality markup language to create a three-dimensional spiral of text which the reader can spin, invert, twist and explore from every conceivable angle. The text appears to be a single letter, but turns out to be two letters, one from the artist to his dead grandmother and another to his newly born daughter.

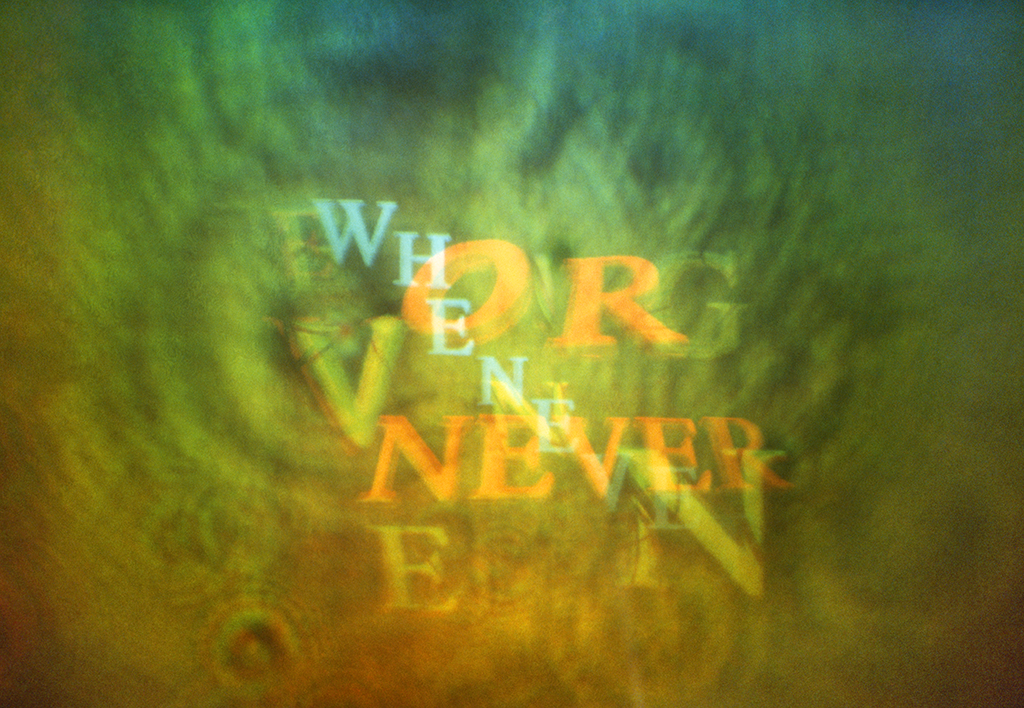

Text and language are perhaps the two technologies which most profoundly shape our lives. By altering our perception and engagement with text, Kac raises questions about the way in which we communicate and understand each other. In his beautiful holopoems, one of which is on display in the Furtherfield exhibition, Kac creates texts which shift and change depending on the angle at which they are viewed. Text technologies frequently give the impression of immutability, but Kac’s holopoems remind us how unstable and deceptive texts may be.

The full range of Kac’s technological exploration is impossible to encompass in a single exhibition, but some sense of it is evident from his website (www.ekac.org). Particularly fascinating is the way in which Kac has explored the poetic possibilities of technologies which are now redundant. Although the platform on which the work was realised is now obsolete, the work nevertheless anticipates contemporary digital cultures. Thus, Kac used the French videotext network Minitel to show the possibilities of network art. He demonstrated the potential of large-scale collaborative works by various pieces using fax. Kac was already experimenting with the potential of telepresence, robotics and wearables in the 1990s.

At each point in these explorations, Kac urges us to engage with these technologies creatively, to use them to create fresh visions, and not simply to accept them as consumers. As a historian, I have long felt that humanities scholars too often passively accept the technological resources and tools made available to them by commercial companies and others. One of the reasons why I believe passionately that humanities scholars should engage more closely with artistic practice is that such a dialogue will foster a more creative and critical approach to the use of digital methods by humanities scholars. The artists whose work I have encountered in the course of my AHRC Fellowship, such as Fabio Lattanzi Antinori, Michael Takeo Magruder, and Katriona Beales as well as pioneers such as Nam June Paik all convey the message that we need to engage creatively with technology. Technology is a threat if we view it passively as an inhuman external force; if we rather seek, like Kac and these other artists, to interrogate, extend and reimagine technology in a creative way we can hope to take greater ownership of it.

This is most spectacularly illustrated in Kac’s bio-art. It is now becoming evident that new biotechnologies will within a short period of time profoundly alter human existence and personality. Kac’s bio-art (following in a tradition which includes the creation of germ pictures by Sir Alexander Fleming) again encourages us to engage creatively with these emerging technologies.

DNA is text and DNA can be poetry of the most profound sort. In a series of works called Genesis (2001), a synthetic gene was created by Kac by translating a sentence from the biblical book of Genesis into Morse Code, and converting the Morse Code into DNA base pairs according to a conversion principle developed by the artist. The sentence chosen was Genesis 1:26: ‘Let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth’.

Visitors to the gallery showing Genesis could trigger mutations in the bacteria’s DNA by switching an ultra-violet light on and off. This in turn mutated the text when it was converted back in morse code and then into English. The artist comments that ‘the ability to change the sentence is a symbolic gesture: it means that we do not accept its meaning in the form we inherited it, and that new meanings emerge as we seek to change it’.

Kac’s most well-known work is GFP Bunny (2000) in which an albino rabbit called Alba was bred in a laboratory with a gene causing the rabbit to glow fluorescent green under a blue light. Kac’s image of Alba has become very well-known and was perhaps one of the first iconic art images of the twenty-first century. We will be exploring the cultural phenomenon of Alba in another exhibition at the Horse Hospital called ‘…and the Bunny goes Pop’, opening on 2 June 2018.

The distinctive image of Alba, shown on The Alba Flag (2001) hanging outside Furtherfield during the exhibition, is also a highly poetic image, conveying many messages about identity, the nature of life and belonging, and the increasing intersection of these with technology. Kac’s memories of Alba prompted him to create a wordless language system incorporating rabbit imagery which he called lagoglyphs (from the ancient Greek words ‘lagos’ for hare and ‘glyphe’ for carving).

Kac has now begun a series of Lagoogleglyphs, large lagoglyphs designed to be visible from the satellites which provide the imagery for Google Earth. Lagoogleglyph I (2009) was installed at Oi Futuro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Lagoogleglyph II (2015) at Es Baluard Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Palma de Mallorca, Spain. Lagoogleglyph III has been installed in Finsbury Park.

The Lagoogleglyphs encapsulate what is to me the central message of Kac’s work. Google is a vast all-encompassing technology giant which encourages us to consume its services while it makes money from data about us. The way in which Google Earth acts as a panopticon for the world, presenting an idealised sunny view of the planet’s surface, symbolises the hierarchical downward nature of much modern technology.

How can we seek to make our presence felt with the world of mass corporate technology? Painting a huge image in Finsbury Park is an inspired way of intervening in the artificial deracinated corporate view of the human world presented in Google Earth.

When the Arts and Humanities Research Council established its strategic theme of ‘Digital Transformations’ in 2011, the terminology echoed that used in many corporate contexts, and was redolent of improved business processes and data management. Eduardo Kac’s work reminds us that real digital transformations are achieved through creative interrogation of technology and through reimagining how we engage with that technology. Poems turn out to be true drivers of digital transformation.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

DOWNLOAD GALLERY HANDOUT

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

In his first solo show in the UK, pioneering media artist Eduardo Kac puts poetry into space in entirely new ways and prompts us to ask “How do words work? What happens if we look at them upside down or inside out? What kind of poem could be made by an astronaut in outer space? What has poetry got to do with green bunnies?”

Kac explores how digital and other technologies provide poets with new possibilities of sound, light and movement. Even space flight offers the poet opportunities. Kac moves the poem off the page and into action. He explores the poetic possibilities of technologies ranging from digital videos and holograms to DNA manipulation and space flight, liberating poetry from the constraints of the printed page.

You can experience poems by Kac in the three rooms of Furtherfield Gallery as well as outside in the park. Follow the rabbit-shaped drawings on the paths in the park to see Poetry for Animals, Machines and Aliens in Furtherfield Gallery and installed in the field nearby.

Kac’s most famous work is GFP Bunny (2000), in which a rabbit called Alba was created in a laboratory with a gene causing her to glow fluorescent green under blue light. The artist made The Alba Flag (2001), on the outside of the Gallery next to the entrance, to celebrate Alba. Kac’s work with Alba prompted him to create a wordless language called lagoglyphs that give new expression to the bunny.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is Kac’s Lagoogleglyph, a work made for viewing from space. Covering a field in Finsbury Park it is optimised by Kac for viewing through satellite imagery and visible in Google Earth. The Lagoogleglyph is part of a series which forms a globally distributed artwork visible only from space. Earlier Lagoogleglyphs were installed at Oi Futuro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (in 2009) and Es Baluard Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Palma de Mallorca, Spain (in 2015).

Also featured in the exhibition:

In Adhuc (1991), holography alters our behaviour as readers. You cannot read the poem left to right. You must dance a little in front of it. As you do this, letters and words shift, drift away and colours change.

Inner Telescope (2017), performed by the French astronaut Thomas Pesquet in the International Space Station, is poetry for zero gravity. The form has neither top nor bottom, front or back, left or right. Sometimes it looks like the French word MOI (me). At other times, it looks like a human figure with the umbilical cord cut. It is the first poem to be made in outer space.

Let’s Fill this Park with Rabbits!

Free family Workshops

Sat 7 April, Sun 22 April & Mon 7 May, 11am – 4.30pm

Furtherfield Gallery

Families and groups of all ages are invited to join artist Michael Szpakowski to design their own giant rabbits and draw them on Finsbury Park by walking your own rabbit route using GPS software. Just turn up on the day to book a place for your group – workshop places will be offered on a first-come first-served basis on each day. Groups and families can also just turn up on each day to join in with the fun and walk some bunny routes in the park.

FREE

Arts and Humanities Research Council Digital Transformations Workshops

Inspired by and building on the Kac exhibition, these workshops will draw together themes and issues which have emerged from the AHRC thematic research programmes including Translating Cultures, Science in Culture, Care for the Future and Connected Communities.

More info

Digital Transformations and Community Engagement

18 April 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

How can we promote collaboration between communities and academic researchers? Do digital methods help create community engagement?

FREE | booking essential

Reconnecting Artistic Practice and Humanities Research

25 April 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

Can a renewed dialogue between humanities scholars and artistic practice provide innovative perspectives to confront current social and cultural challenges?

FREE | booking essential

Language and Diversity

8 May 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

Exploring the role of language and translation in promoting understanding and communication within, between, and across diverse cultures.

FREE | booking essential

Science in Culture

23 May 2018, 10.30am – 4pm

Furtherfield Commons

How can art engage with science and technology? And how can art explore the role of science in culture?

FREE | booking essential

Further Eduardo Kac exhibitions are being held in London during 2018 as part of the AHRC Digital Transformations theme. During June, the Horse Hospital, Colonnade, Bloomsbury, London WC1N 1JD, will host an exhibition called … and the Bunny Goes Pop!

This exhibition forms part of research undertaken by the Digital Transformations strategic theme of the Arts and Humanities Research Council. It has been curated by Professor Andrew Prescott of the University of Glasgow with assistance from Furtherfield team and Bronac Ferran, with advice and support from the artist.

Eduardo Kac has been a pioneer in exploring the use of new technologies to create innovative poetic experiences. Experimenting with a range of technologies since the 1980s including fax, photocopiers, LED screens, the French videotext service Minitel, holography, conductive ink, and a variety of digital and network technologies. Kac’s distinctive body of work has been featured in exhibitions in New York, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, Madrid, Shanghai, Tokyo and many other venues. He has received the Golden Nica Award, the most prestigious award in the field of media arts and the highest prize awarded by Ars Electronica. This is his first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom.

Andrew Prescott, Professor of Digital Humanities at the University of Glasgow and Theme Leader Fellow for the ‘Digital Transformations’ strategic theme of the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Furtherfield is an internationally renowned arts organisation specialising in labs, exhibitions and debate for increased, diverse participation with emerging technologies. At Furtherfield Gallery and Furtherfield Lab in London’s Finsbury Park, we engage more people with digital creativity, reaching across barriers through unique collaborations with international networks of artists, researchers and partners. Through art Furtherfield seeks new imaginative responses as digital culture changes the world and the way we live.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion

Finsbury Park, London, N4 2NQ

Visiting Information