In 2011, Rachel Clarke and Claudia Hart co-curated The Real-Fake, a post-media exhibition engaging art made in synthetic spaces, shot with virtual cameras, and emerging from “other spaces” like code-space and biotech. In 2016, Clarke and Hart together with Pat Reynolds updated the show at the Bronx Artspace, with over 50 artists working in immersion, virtuality, game space, digital photography, and so on. Two months after the launch of real-fake.org, and in the first month of the US Trump presidency, which could be argued as the first presidential campaign simulated in Baudrillard’s terms, Claudia Hart and I talk about what “real-fakeness” is, how it arrived as an art notion, and how it has informed two exhibitions.

PL: What, in your mind does the show represent as an expression of contemporary culture?

CH: The Real-Fake remake opened on November 19, slightly after the election. I was actually in the air when Trump won, landing in Bucharest, several hours later. The culture there is still overshadowed by the history of the totalitarian regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu. The contemporary art museum actually sits in a corner of his Palace of the People, which was built in the style of WWII Italo-fascist Neoclassicism. The whole experience was ominous and frightening in relation to the autocratic, punitive Trump. I began obsessively tracking “fake news”, both because of its relationship to the kind of propaganda used by the Trump/Bannon team to hijack the presidency, but also because of the hacking of the democratic party and collusion of the Republicans with the government of Vladimir Putin.

In both the 2011 and the 2016 versions of the Real-Fake exhibition, we tried to deconstruct, for simplicity’s sake, what I’m now calling “post-photography”, or what Steven Shaviro termed as the “Post-Cinematic.” This relates to digital simulations of the real made with current technologies of representation and post-mechanical reproduction. Post Photography can be defined by what it is NOT in relation to everything documentary and verité about photography. It suggests a radical paradigm shift with significant cultural ramifications. Post Photography does not purport to “slice” from life, but rather is a parallel construction of it, numerically modeled with the same techniques used by scientists, and also by the game and Hollywood special effects industries. The artists working with it all use specialized compositing and 3D animation software. But instead of capturing the real in an indexical fashion, Post Photography artists use measured calculations to simulate reality.

Our deconstruction of the post-photographic real-fake was made in relation to cultural myths about the truth, through viewing the work of 50 artists. They are all part of a larger community acutely aware of the implications of using a computer model of the real as opposed to traditional capture technology. The issues implied by this choice have obviously been made manifest at our own historical juncture, when the culture of science and climate-change deniers rule America. The manufacturing of fake truth in the form of misinformation and ubiquitous infotainment are now profoundly epic.

I’m currently reading Gabriella Coleman’s Hacker, Hoaxer Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous (Verso, 2014) a history of hacker culture related to both the esthetics of “Real-Fakeness” and also the actual milieu that it emerged from. I’m inspired at the moment by that book, and the brilliant essay “Tactical Virality” by Hannah Barton (Real Life, February 14, 2017) because they’ve helped me to articulate what I now feel is the relationship of The Real-Fake to our current cultural and political quagmire. What excited me about the Barton article is that she finds language to talk about the fake news, meaning in larger terms, the fake media strategy so successfully implemented by the Trump/Bannon team. Both of these men are fake-media production experts, and individually built lucrative empires with their expertise. Fake news is a product, and one can trace its lineage from the first alt-right radio flamers, through Fox, Breitbart and now, embodied in the personage of Steve Bannon, straight into the oval office. Fake news is a semiotic morph, a kind of hybrid of advertising and spectacular entertainment covered by a gloss surface of “news” or facts, that can be output in a range of forms from talking-head news commentators, to pseudo down-and-dirty cinema verité documentary. It is a knowing contemporary version of propaganda, and in fact, as reported by Joshua Green in Bloomberg Politics in 2015 even, in a chilling profile of Steve Bannon (https://www.bloomberg.com/politics/graphics/2015-steve-bannon/), Andrew Breitbart himself called Bannon out as “the Leni Riefenstahl of the Tea Party movement.”

So, with Bannon/Trump, we have entered into a paradoxical social-media semiotic in which that which most strongly resembles what Stephen Colbert dubbed as “truthiness” must be suspected as being the biggest lie.

PL: And to focus this back to art, perhaps what we might say is that instead of Picasso’s axiom of artists telling lies to reveal the truth, to make a fake “real” is to go through the machinations of media manipulation that Robert Reich talked about, like pulling the media in and driving conversation until it’s “almost real.” Maybe that’s the quality of “Real-Fakeness,” or even “Fake-Realness” (to do a structural inversion). And with “Simulationists” as we are, and postinternet artists, perhaps veracity and verisimilitude aren’t the point anymore. Maybe it’s just what’s in the boxes and “teh netz”.

CH: Exactly. All of these players are deploying the representational tactic of structural inversion, one of the techniques used to grab audience attention and leverage in the Internet media economy. Bannon’s professional canniness in rerouting the attention economy into fake news, was that flaming mis/information could be sold as a very lucrative attention-economy product. Likewise Trump made a fortune within this economy. Both are experts in the tactics required to make a thing go viral, in hacking the media/entertainment system for maximum clicks. Their approach obviously works. And you can see this in some of the work in the show.

PL: Jean Baudrillard famously wrote about the simulated image in media culture that finally is believed to supplant the Real, i.e. “The Desert of the Real”. Do you think this is where we are with the notion of “Real-Fakeness”?

CH: Tactically viral fake news resembles the Situationist practice of détournement – what Barton called “virtuosic prank-like acts designed to turn expressions of the capitalist system against itself.” This impulse lurks behind most of the hacker culture that Gabriella Coleman documented. Even with the most sincere and political of intentions, hacker culture denizens share a position of deep Duchampian irony. Hackers are all, more or less, in it for the lulz – a kind of dark, aestheticized Nietzschean “lol” which injects noise as agents of chaos, being much different than tactical artists who fight the system. This darkness characterizes a time in which artists and cultural commentators routinely meditate on how one might psychically navigate the end of civilization, for example Roy Scranton’s brilliant Learning to Die in the Anthropocene,” (CIty Light Books, 2015) and the Morehshin Allahyari /Daniel Rourke 3D Additivism project that I feel so profoundly connected to.

And in case of point, Morehshin is a “real-fake” artist.

PL: I have a lot of support for it, too. I think that projects like 3D Additivism are really significant on so many levels, as things like tactical aesthetics, media art, and criticism lend themselves to collective projects. I mean, most likely more than half of my work and collaborations are collective; RTMark, Terminal Time, Yes Men, Second Front, Pocha Nostra, Morehshin’s My Day Your Night project with Eden Unulata… It just seems that these areas of work build community, and that’s something I’ve always believed in. 3D Additivism really addresses critical aspects of the explosive nature of digital making, its pitfalls, and how to deal with these Anthropocene issues through the problematics of the very technology that it critiques. That’s the issue with ”real-fakeness”; it lives in this tactical center where it’s by necessity earnest, yet ersatz at the same time, kind of like Dubai.

CH: Exactly. What this specifically means in terms of the work we exhibited was that it routinely coopts strategies of representation often found in advertising slogans, media products and propaganda, to serve an alternative agenda – sometimes to propose a ludic reality and sometimes to propose a more utopian one as opposed to the dystopic one of Fake News. This is the premise of REAL FAKE art, and is related to the Simulations discourse of Baudrillard.

PL: And then the Real-Fake artist takes the Real, verisimilitude, and détourns it into sets of aesthetic tactics that reframe the nature of the work itself, radically shifting its art historical context.

CH: The approach of the artists in the Real-Fake is the tactic of détournement that the Situationists introduced in the late 1950s and 60s. They were also countering a reactionary Cold-War culture, ironic in terms of Trump’s oligarchical relationship to Moscow. The idea of Situationist détournement, which is so connected to the ideologies and tactics of hacker culture, is to irritate conservative, Capitalist hegemonic power. I mean YOU were part of The Yes Men, and détournement strategy was very influential to that group. The tactic of détournement tweaks entrenched bureaucratic power structures … there is nothing intrinsically political about it in itself. It’s a kind of publicity stunt, a way of grabbing media attention and thumbing one’s nose at the powers that be. It is the posture of the trickster. To quote Barton, détournement “can be reduced to an ideologically flexible logic of inversion and appropriation.”

PL: Right. And this relative, flexible set of significations inevitably creates paradoxes and contradictions that hegemony/Deep Power/the Superstructure can’t process.

CH: In real-fake simulations, the détournement is of representations that are “impossible” – that appear both real and unreal at the same time, being inherently uncanny in the Freudian and Mori-an sense – both dead and alive simultaneously, it is a paradoxical state in which opposites collide. What happened in the prelude to the 2016 US presidential election then is that is that pro-Trump fake news, advised by Bannon, tactically assumed that position by playing the “outsider’ card, and pantomiming resistance. However, we all know they simultaneously bequeathed the benefits of it onto a gang of billionaire plutocrats – the richest oligarchs and corporate leaders in the world. They seized the power of the news media, itself already perceived by the masses as truthy “information,” which this oligarch gang, for the most part, owned (Fox News for example, is owned by the rightist Rupert Murdoch). It was done to further consolidate power and seize the government. They then staged a “return of the repressed” (or the emergence of a new ‘oppressed’), for the Trump “base” – a fringe hate-mongering hyper-aggressive “wrestling” culture to borrow from a related ethos. This demographic was duped into believing that they were speaking their truth to entrenched liberal governmental power, although they were actually being used and manipulated as mouthpieces of a feudal corporate bloc who by then had completely co-opted the federal government. Videos of this radical fringe were then recorded to flame hate and racism, opening Pandora’s Box for white Middle Americans to enact similar cultural forbiddens that had been oppressed by the corporate institutional repression of “Political Correctness”: sexism, racism and religious xenophobias. Hate was linked to the First Amendment, and it unified Trump supporters, and Fake News coopted Yes Men tactics to oppose the Left, the strategy of détournement. But as was recently said, détournement is not ideologically married to the Left, and yes, this is where we are at right now. The question at this time is if we can re-take these strategies to take some power back.

PL: On the other hand, Western society is confronted with the notion of Fake News, “Alternative Facts”, and the like. Again, I will draw on Picasso saying that artists tell lies to reveal the truth. Do you think this is the difference between “Real-fakeness” and “Alternative Facts”, which are propositions that willfully try to obscure reality for their own ends?

CH: In her article, Gabriella Barton analyzes how fake news manages to go viral. Our current media ecosystem, the one in which fake news played out during the election, is a fluid information economy in which stories bring together groups on the basis of group identity around their positions. These need not have any relation to fact…they are actually reflections/inversions of ideologies, and can be thought of as contemporary mythologies in the sense of Roland Barthes. That’s structurally how fake-news is used to manipulate the populace, and how the populace makes certain fakeries go viral. In the culture of social media, where clicks are king, people create their identities by associating themselves with “links” to such media mythologies, pseudo info bytes that resemble information and news, in order to associate themselves with whatever community they identify with.

Barthes’ 1957 Mythologies examined our tendency to create versions of myths from the ubiquitous media that surrounds us. Trump/Bannon came to the same conclusions as Barthes, though doubtfully by reading him, surely as a result of their first-hand experience as media-moguls. They’ve pushed Barthes’ insight to its ultimate conclusions, creating fictional mythologies that simulate information as news in order to build their community. This community is ultimately nihilistic, and is unified primarily by their fear and an anxiety about the loss of their white dominance in an emergent, global post-industrial culture. The Trump/Bannon team built their base, giving them material to construct individual identities by viralizing propaganda and simulated information.

What I’d like to propose alternatively is that now as media artists specifically, we can similarly build mythologies not of authoritarian dominance but of resistance. For example: I love Catwoman! I find her to be an emotional paradigm symbolizing resistance. I wish I had invented her myself. I wish I was her! I’d like to propose to contemporary media artists that they perform alternative mythological identities of resistance created in the space of public media, as a means of creating community. I believe in community and believe it’s only through community that we can drive a wedge into autocracy. I think we can use media to mythologize emotional truths of resistance, Barthean mythologies that are more communal and constructive, to inspire activism and resistance.

Perhaps Trump will implode eventually. Since he’s seized power, he’s made many references to fake news in tweets. To quote Barton again:

This is tactical virality now reified as strategy by a sitting administration defending the executive branch’s power. In his Twitter performances, incoherence has become a coherent approach, seeking to pre-emptively absolve Trump of accountability.

So, in response, I’d like to believe that, if we follow Barthes’ thought to its logical extreme, Trump is now inverting his own inversion, a reification and draining of his own mythological power. Then, if the Goddess is on our side – he folds in upon himself!

PL: Do you think what we are doing with “Real-Fakeness”, Simulationism, and the like is sampling reality as a medium, a toolkit?

CH: Yes! I hope! I’m a simulations artist and real-fakeness is my tool. I hope that with it we can both inspire resistance and build an alternative world. Aside from lending my body to street manifestations and calling my congress-people, it’s what I can do now.

PL: How does all of this express itself in your work, and how do you feel you speak to the simulated spirit of the times?

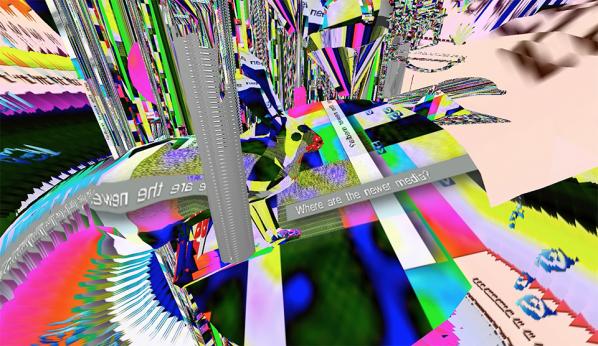

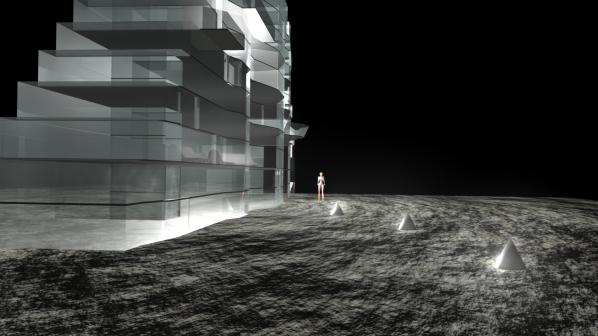

CH: At the moment I’m developing several projects, post-Trump. The one that is most relevant to this converstion is The Beauty of the Baud, that I’m working on with LaTurbo Avedon – the virtual artist living only in the spaces of social media – meaning Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tumblr. She also is the curator of Panther Modern, a museum that also only exists virtually, exhibiting the post-photographic documentation of the exhibits that happen there. LaTurbo invites artists who work with VR software to create shows, offering each a room in her museum. She then displays simulated documentation of them at panthermodern.org.

Since 2007, I’ve developed a curriculum at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, called X3D, a group of 8 classes that work with simulations technologies in the context of post-photography and experimental media. The Beauty of the Baud is a project led by LaTurbo Avedon and I in collaboration with one of those classes, my Experimental 3D 2017 class.

LaTurbo built “Room 17,” a special Panther Modern exhibition hall, to show works created by my Intro X3D class, a group of 14 Art Institute students using simulations software for the first time. Acting as both guest critic and curator of the first Panther Modern group exhibition, she is choosing 14 works, one from each student, out of a selection of renderings of solo shows, each produced for Room 14, The Beauty of the Baud room, inside Panther Modern. The whole thing is conceived in relationship to the 30th birthday of The Hacker’s Manifesto. We are also reading the Coleman book, and discussing it as we go.

The Beauty of the Baud will be shown online, in Panther Modern in May, 2017. Then a portfolio of archival prints of the computer-model images will be offered for sale, all proceeds from it donated to either international immigrant assistance, inner city education or climate research – my students are debating which among themselves even now. Both an exhibit in “real” as well as “virtual” life, The Beauty of the Baud will include the student portfolio, plus conceptually related works by LaTurbo Avedon and I, and will geographically be situated in Bucharest – the city that inspired me to go down this route in the first place- with the Romanian curator Roxana Gamart in her Möbius gallery. She is in conversation with several institutions there as well, and we are working on something for that context.

I’m very psyched about the Beauty of the Baud. It’s helping me to process it all. As an artist, at this moment in time, I’m afraid it’s the best I can do.

The productive alliance between instruments of computing techne and artistic endeavour is certainly not new. This turbulent relationship is generally charted across an accelerating process outwards, gathering traction from a sparse emergence in the 1960s.[1] Along the way, the union of art and technology has absorbed a variety of nomenclatures and classifiers: the observer encounters a peppering of computer art, new media, Net.art, uttered by voices careening between disparagement, foretelling bleak dystopian dreams, or overflowing with whimsical idealism. Once reserved for specialist applications in engineering and scientific fields, computing hardware has infiltrated the personal domain.Today’s technology can no longer be fully addressed through purely permutational or systematic artworks, exemplified in 60’s era Conceptualism. The ubiquity of devices in daily life is now both representative and instrumental to our changing cultural interface. Technologies of computing, networks and virtuality provide extension to our faculties of sense, allowing us phenomenal agency in communication and representation. As such, their widespread use demands new artistic perspectives more relentlessly than ever.

I, and no doubt many other academic observers, watched the Pokemon Go augmented reality (AR) game erupt into a veritable social phenomenon this year. The rapid global uptake and infiltration of AR in gaming stands in contrast to new media arts, still subject to a dragging refractory period of acceptance and canonization. Perhaps this is emblematic of a conservative art world that persistently recalls an ebullient history of computer art practices. In this lineage, many a nascent techno-artistic breach has been accused of deliberate obfuscation, of cloaked agendas under foreign (‘non-art’) orchestrations.[2] The seductive perceptual forms elicited through augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and immersive reality (IR) devices can be construed as mere spectacle, vulnerable to this type of critique. “Google Daydream” and “HoloLens” chime with a poetic futurism; cynics might instead see ready-to-wear seraphs veiling the juggernauts of Silicon Valley. However, the current groundswell in altered reality discourse may signal a divergence from such skepticism. One recent exemplar is Weird Reality, an altered reality conference that aimed “…to showcase independent and emerging voices, creative approaches, diverse and oftentimes marginalized perspectives, and imaginative and critical positions…. that depart from typical tech fantasies and other normative, corporate media.”[3] This is representative of the expanding, international trend towards artistic absorption of new media and technologies. It is a turn that emphasizes the potential for cultural impact, experimental daring, and even conjures the spectre of the avant-garde: radical transformation.

One of my PhD supervisors wisely admitted “…to stand out, the human artist must be more creative, diversified and willing to take aesthetic and intellectual risks. They can and must know the field they are creating in practically and philosophically, and confidence in their position and contribution to it is essential.”[4] Through this earnest lens, artistic production can serve as a conduit for ideas ranging from the speculative to the revelatory. In these divinations, we might trace a path through the sprawl of new media discourses, and find ourselves somewhere unexpectedly revitalizing. I hope to mark out some of this territory from a position of mediation. I want to invite art and art theory into an arena of uninhibited collusion, using critical writing to facilitate the exchange between digital media theorists and artistic practitioners in the most open sense. Furtherfield.org offers an allied platform for the aims of the Theory, Meet Artist [5] project, articulated here in an interview dialogue.

Originally published in The Fibreculture Journal, Edwina Bartlem’s 2005 article Reshaping Spectatorship: Immersive and Distributed Aesthetics proposes that immersive artwork practices have transformative potential. Across a range of modalities, these works can influence perceptions of ourselves and our extended digital presence in a variety of scenarios and configurations. Whilst participating in such practices, we are prompted to consider IR encounters as form of mediation around our human embodiment, subjective identities and cultural interactions. Bartlem touches on ideas of prosthesis and sensorial augmentation within these immersive experiences. Creation of a synthetic environment is posited as an opportunity for deepened self-reflexivity and awareness.[6] In parallel, a spectrum of narratives around the technologically adapted ‘post-human’ emerge. Their tone and reception hinges upon the artist’s individual performance in roles such as programmer, director, composer or overseer to such works.

Rachel Feery is an Australian artist interested in the intersection of visual art, soundscapes, video projection, experiential installations and technology. Her artistic practice explores alternate realms, the meditative headspace, ethereal imagery and immersive environments. For this interview, Bartlem’s paper is positioned alongside and in dialogue with Feery’s work, Clearing the Cloud.

Clearing the Cloud is described by the artist as “… a multi-sensory work inviting pairs to cloak-up, complete a circuit, and experience simultaneous mapped projections visible through a hooded veil. The artwork aesthetic draws from esoteric sciences and holistic health practices. The environment is intimate, quiet much like a room where one would go to receive therapeutic treatment.

Two participants at a time are invited to cloak up, remove their shoes, and step onto sensors on the ground to generate a circuit of light and sound. Starting with a ‘personalised scan’ followed by a projection of light and sound, all visible and audible within the suit itself, the individuals can either interact with each other or be still and silent. The robe, constructed of a semi-translucent, lightweight fabric with a soft skin-like texture acts as a supplementary skin. One’s field of vision is slightly inhibited by a lightweight mesh that both creates a screen-vision as well as the ability to see through it.”

Jess Williams: I first came into contact with your practice during your talk for Media Lab Melbourne in September this year. You chronicled your process, influences, past works and brought us to Clearing the Cloud. I was struck by the experiential intimacy of the project, and the immersive qualities that you deployed though staging it. In her paper, Bartlem suggests that participants in immersive practices cannot be immersed without being affected by the environment on perceptual, sensory, psychological and emotional levels. What kind of sensorium did you want to create for Clearing the Cloud, and did you contemplate the possibility of this type of affective influence on your participants?

Rachel Feery: In one sense, the project came about while I was thinking about art as therapy, and thinking about technology that has the potential to create a meditative space. The site of the exhibition, Neon Parlour, was previously a centre for healing and meditation. I wanted to create an intimate room that would reflect the building’s history. Speaking of the sensorium, I was drawing from esoteric sciences, looking at auras, and Reiki practices whereby chakras are ‘cleared’. This is all reflected in the visual and environmental elements of the work, but ritual aspect is key. It’s important for participants to enter the artwork through the process of putting the garment on. The ritual is something you have to experience with someone else, and there’s a synchronicity between the people who participate. If either person takes their feet off the sensors, the ‘therapy’ is reset. It becomes apparent that there’s a level of commitment to it, that there’s a trust involved. If one person backs out, the interaction stops and resets.Clearing the Cloud ultimately asks participants to commit and experience the work together. Some participants responded that they felt lighter, and that time had passed out of sync with the seven minutes that had passed in reality. I thought this was an interesting reaction when nowadays, our attention spans are said to be dwindling. I feel there’s something significant in a lot of those esoteric sciences.

JW: Bartlem maintains that immersive art offers more than pure escapism into a constructed simulacra. These types of artworks can also elicit a type of self-awareness or meditation on perception and one’s own agency in the prescribed environment. I’ve noticed a strong tendency to consider transcendence, or the superhuman, in many futurist discourses around technologies that interface with the human body. This spans augmented reality, virtual environments and may well capture less conspicuous (yet ubiquitous) examples, such as fitness metrics or geolocation of the self through GPS. How do you position narratives of extending or ‘hacking’ embodiment within your own work?

RF: There’s an aspect of being both physically present and also outside of yourself whilst engaged in Clearing the Cloud. As a participant, you find yourself looking through a meshed veil that’s being projected on, and if you adjust your focus, you can see coloured projections on the other participant. This dual, simultaneous vision got me thinking about the ways that newer technologies such as AR and VR can affect what we see and the way that we see. Essentially, those applications allow you to see an environment with a filter over it. You have the sense during the ‘clearing therapy’ of an outer body experience, which is something that certain types of meditation aspire to. Escapism can imply you’re ignoring what’s happening in the outside world and going inside yourself, or elsewhere. But technology is blurring these boundaries, becoming increasingly intertwined in everyday activities, both personal and shared. You’re not really escaping if there’s an application present to assist with something, provide new information, or an augmented experience. In that sense, I would agree that it’s not pure escapism. You’re in two places at once. I would say that the word escapism has darker implications, such as detachment and avoidance of reality over a virtual space. Meditation, however, is affiliated with deeper understanding of oneself, and acceptance and appreciation of both worlds. As technology gets more advanced, I think it will have the ability to do both.

I like the idea that two people willingly participate in this scan and projection without question. I feel it relates to this influx of new technology applications that are free and that everyone’s willing to try. On the darker side, I wonder about the consequences of giving away information- effectively, parts of yourself- to participate in the unknown. I also like the idea that Clearing the Cloud is presented as a holistic therapy, a gesture of removing the build-up of accumulated information, or as protection from the data mining we’re exposed to through technological interfacing. We’re made vulnerable to hacking, but in a sense it’s not really hacking anymore, it’s just collecting what we’ve been giving. There’s such a rush to use new applications and technologies but everything is untested. Essentially people become trial subjects through their willing self-disclosure.

JW: You mentioned David Cronenberg’s 1999 film eXistenZ as a formative influence in your creative development. Underpinning the science fiction and horror themes, a specific abject revulsion is reserved in this film for prosthetic extension and modification to the human body. Could the veils (with their accompanying perceptual experiences) used in Clearing the Cloud be viewed as a form of sensory prosthesis?

RF: I would say I was more interested in the idea of accessorising tech, rather than prosthetics. I am drawn to the way that Cronenberg’s characters leave their physical body and enter another state, but again, this is quite geared towards escapism. Using the veils arose through researching a mix of religious and medical robes, futuristic fashion and science-fiction inspired fashion. They all seemed to be white. There’s also a relationship with the cloak to other forms of wearable technology. I’m interested in this – in Google Glass, VR headsets, and related items – as both a current fashion trend and also as a subtle way that technology encroaches on our day to day lives, present as we move through and see our worlds. While I perceive the cloak itself is not so much of a prosthesis, there are certain physical qualities of the material that feel both organic and synthetic. They’re made of a foggy, PVC translucent plastic: when worn, this fabric feels like a skin. The backwards-oriented hood also functions as a way to obscure the face, and presents a form of anonymity that is ultimately within the concept of ‘being cleared’ and ‘regaining yourself.’ There are other associations too: of a uniform, of being part of a community that has been cleared, or erased.

JW: Typically, when audiences are presented with new media or computer mediated artworks, they have limited access to the operational interior of the encounter. Whilst it can be argued that more traditional media or installation works also don’t completely disclose their construction or authorship, new media practices seem subject to increased scrutiny and distrust around how- and to what end- they operate. In her paper, Bartlem proposes that instead of masking the presence of technology and interface, immersive artworks tend to overtly emphasize the synthetic artifice of the experience. In regards to revealing the hierarchies of control implicit in executing works like Clearing the Cloud, how much do you wish the audience to have a certain ‘privilege of access’? For example, do you consider it necessary to directly reference programming script, hardware circuitry, or technologies of surveillance?

RF: The actual technology used in the exhibition was not necessarily about aesthetics. Hardware and devices, such as projectors and Raspberry Pis, were not elements that I wanted audience attention drawn to. Moreover, I think if you give spectators interior access, it can take away the simplicity of the art experience. The most that I would give away would be the materials visible or listed in the artwork. I actually tried my best to mask the technology, hiding cords and mounting the projectors up high to make it feel innocuous and to minimise its physical presence. Once people can identify familiar tech, there is an immediate undermining of mystical impact. For this artwork, I worked with artist and technologist Pierre Proske to write a code that triggers the projection once the sensor pads are activated. The hardware elements are present, but they’re definitely not the focus. Rather, it’s the experience itself, the meditative space created that participants are made most aware of. I think that’s why auras, and energy healing, are so fascinating: they rely on people’s ability to embrace and believe in the healing process, which in turn requires any distractions or doubts to be removed- or at least obscured. Obsfucation was deliberately built into the back-to-front hoods used in Clearing the Cloud. Restriction of the visual frame of reference was intended to encourage immersion in the experience.

JW: As we’ve discussed, the eponymous gesture of “clearing the cloud” reads as recuperative, meditative, and somewhat subversive towards strategic or commercial use of new technologies. This is a position that Bartlem suspects is endemic within artistic instrumentalisation of these types of media. Do you feel a sense of alignment with a more radical manifesto in new media practice?

RF: A lot of my ideas draw from or relate to concepts that have been proposed in science-fiction films… science-fiction is radical. Sci-fi extrapolates the current social, political or technological trends, or explores alternate models. Clearing the Cloud also proposes a need for something that hasn’t quite been quantified, a therapy to restore and protect from encounters with technology. Clouds traditionally connote lightness, and formlessness, but today they weigh heavily on us in a digital data context. We carry more and more information, and give more and more of ourselves. We’re now clouded by our metadata trails, and it’s radical to think that a therapy can address this, and return us to a state of clarity, in a literal and metaphysical sense.

JW: After your talk, I asked you a question around whether Clearing the Cloud‘s artistic narrative could function beyond a ‘closed-circuit’ proposition. Whilst Bartlem scopes immersive and telepresent practices in her paper, she doesn’t directly address works that hybridise the two concepts. She frames telepresent artworks as those that link participants from distant locations, precipitating notions of networks and a multi-user participation within art. How would a multiplicity of network relations impact on a scenario like that you have staged in Clearing the Cloud?

RF: An excellent question, and very relevant to the nature of the work. The participant’s experience centres on a propositional ‘defrag’ of their personal hard-drives, regaining clarity, allowing independent thought free from the prison of past browsing histories and metadata maps. Those in a networked community also benefit from this speculative process: the more persons ‘cleared’, the stronger the authentic connections would be. If you were to be ‘cleared’, and your online history erased, the persons closest to you would also need to be erased in order to completely eliminate any trace of you. It’s like a chain reaction. Although only two people might be scanned at a time, for a complete ‘clearing’ you would need the eventual interfacing of everyone you’ve ever come into contact with. Ideas around utopias were intrinsic to the development of Clearing the Cloud. In one view of the work, those people who have been ‘cleared’ became part of a separate, even sanctified community. This meditation was idealistic, borne of the desire to find a way to protect our identities and those of our networks when they are potentially threatened or compromised by interactions with technology.

Clearing the Cloud was originally exhibited in 2016 as part of This Place, That Place, No Place curated by Irina Asriian (Chukcha in Exile) at Neon Parlour, Melbourne, Australia.

SEE IMAGES FROM THE PRIVATE VIEW

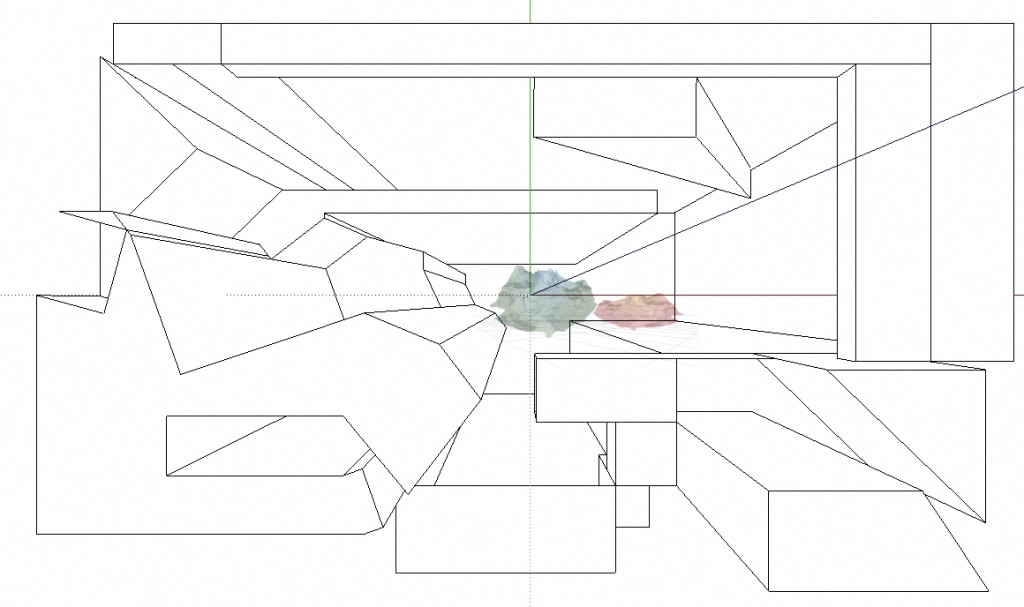

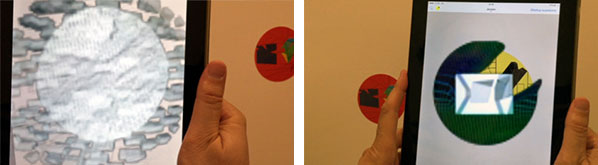

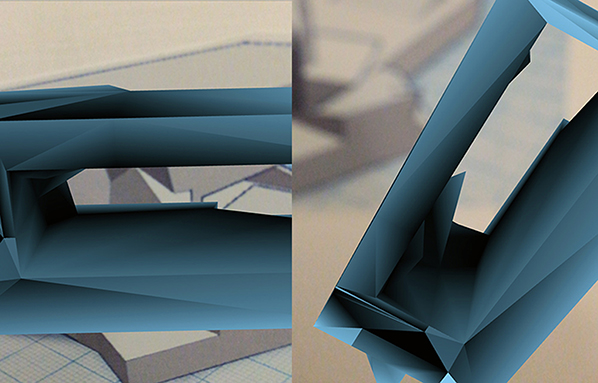

Furtherfield Gallery is proud to present Dimensioning – Live Architecture an exhibition of new digital artworks by Italian artist Chiara Passa, part of Furtherfield’s Open Spot programme.

Passa’s concept of «super places» and her search for new dimensions, or “campo piu’ in là” (a “further field”) underpin her work using architecture as an interface to understand the possibilities of the digital dimension. She uses augmented and virtual reality (AR & VR) to create interactive installations in which the technologies punch through and pull out a new sense of place in combinations of interior, architectural and natural environments.

In this exhibition visitors can explore her new digitally mediated perception of space and time in an animated multi-dimensional ‘trompe l’oeil’ of the gallery rooms as 3D wireframe view. Visitors stand in the middle of the “window-camera” view of the software, which has also been used to build the animations on display. They use augmented reality to “travel through” the walls, into the diagrams.

“Worlds open the doors to other worlds and synthetic shapes become design, structure, architecture and reality.”

Passa’s work offers a refreshingly passionate approach to experimental and philosophical play with technologies. We think that this is especially valuable in an age where our expressive range and behaviour is increasingly pre-determined by the digital tools, techniques and devices that we use daily, and the interests, experiences and values of those who create them.

Also for this exhibition visitors will experience her VR 3D animation using a Google Cardboard viewer.

Chiara Passa talks about Dimensioning – Live Architectures at Furtherfield Gallery in the video below

Chiara Passa, media artist (Rome 1973). Graduated at Fine Arts Academy of Rome; master in new audio-visual mediums at the Faculty of Modern Literature.

Her artwork combines many media and platforms analysing changes in ‘liquid space’ through a variety of techniques, technologies and devices – often constructed using augmented reality and the virtual reality technologies. She works with animation and interactive video-installation; digital art in public space as site-specific artwork and video-mapping; video-sculptures and objects; art-applications and widgets for mobile platforms.

She explores the potentials offered by the intrinsic languages of these emerging platforms to experimenting in a rigorous and personal way with the full expressive range and “unknown creative possibilities that the new media are continuously offering to me”. She received the E-Content Award (2012). Her work is regularly exhibited internationally in galleries and at festivals, conferences and institutions including ISEA, Vortex Dome (USA), Media Art Histories Conference (DE), Electrofringe (AU), FILE | Electronic Language International Festival(BR), CCCB – Centro de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (ES).

Furtherfield is a leading organisation for art, technology and social change. Furtherfield Gallery and Commons spaces in the middle of London’s Finsbury Park explore complex themes relating to digital culture, inspiring diverse people to get involved with arts and technology on their own terms. Debate is facilitated amongst an active international community of artists and thinkers via online platforms, combined with accessible art shows and labs to enable co-creation and widen participation. Furtherfield is a not-for profit, artist led organisation, an Arts Council England National Portfolio organisation, supported by Haringey Council.

The Furtherfield ‘Open Spots’ programme of self-initiated and self-funded exhibitions and events support the presentation of new work and artistic invention, to discover new perspectives on the horizon of a wider networked society.

Curators and artists that meet Furtherfield’s selection criteria can showcase work at Furtherfield Gallery in the heart of London’s Finsbury Park. Open Spot projects can reach a new, diverse audience of gallery visitors, park users and Furtherfield’s online participants.

Those were the words I noticed when interviewing Augmented World Expo organizer Ori Inbar several days before AWE2015, the trade show of Augmented and Virtual Reality. “We’re not in beta anymore…” Inbar said, “We now have companies implementing enterprise-scale Augmented Reality solutions, and with coming products like the Meta One and Microsoft HoloLens, the consumer market is being lined up as well.” With the addition of the UploadVR summit to AWE2015 the event was a blitz of ideas, technologies and new hardware.

AWE/Upload is a trade and industry event that also includes coverage of the arts and related cultural effects, although it is smaller when compared to the industrial aspect of the show. In this way it is similar to SIGGRAPH and this is much of my rationale for covering this, and also SIGGRAPH later this year? Doing so is as simple as McLuhan’s axiom of “The Medium is the Message” or, better yet, examining how developers and industry shape the technologies and cultural frameworks from which the artforms using these techniques emerge. The issue is that in examining emerging technologies we can not only get an idea of near-future design fictions but also the emerging culture embedded within it.

To put things in perspective, Augmented Reality art is not new, as groups like Manifest.AR have already nearly come and gone and my own group in Second Life, Second Front, is in its ninth year. Even though media artists are frequently early technology adopters, what appears to be happening at the larger scale is a critical mass that signals the acceptance of these new technologies by a larger audience. But with all emerging technologies there is drama driven by those industries’ growing pains. For AR & VR the last two years have certainly been tumultuous.

Last year’s acquisition of Oculus Rift by Facebook sent ripples through the technology community. Fortunately, unlike my upcoming example, the buyout did not eliminate the Rift from the landscape; instead it gained venture capital allowing for licensing of the technology for products like the Sony Gear VR. Also the current design fictions being distributed by Microsoft for its Hololens give tantalizing glimpses of a future “Internet of No Things” full of virtual televisions and even ghostly laptops. This was suggested in a workshop by company Meta and the short film “Sight”, in which things like televisions, clocks, and objective art might soon be the function of the visor.

However disruptive events also happen in the evolution of technologies and their cultures. The news was that scant weeks before the conference a leading Augmented Reality Platform, Metaio, was purchased by Apple. Unlike the transparency and expansion experienced by Oculus the Mataio site merely said that no new products were being sold and cloud support would cease by December 15th. In my conversation with conference organizer Ori Inbar we agreed that this was not unexpected as Apple has been acquiring AR technologies, which has been related in rumors of “the crazy thing Apple’s been working on…”; But what was surprising was the almost immediate blackout, part of the subject of my concurrent article “Beware of the Stacks”. For entrepreneurs and cultural producers alike there is a message: Be careful of the tools you use, or your artwork (or company) could suddenly falter in days beyond your control. Imagine a painting suddenly disintegrating because a company bought out the technology of linseed oil. Although this is a poor metaphor, technological artists are dependent on technology and one can see digital media arts’ conservative reliance on Jurassic technologies like Animated GIFs for its long-term viability, but to go further I risk digression.

Another remarkable phenomenon this year was the near-assumption of the handheld as a experience device, and their use seemed almost invisible this year. What was evident was a proliferation of largely untethered headsets, ranging from the Phone-holding Google Cardboard to the Snapdragon-powered (and hot) ODG Android headset, boasting 30-degree field of view and the elimination of visible pixels. In the middle is the tethered, powerful Meta One headset with robust hand gesture recognition. Add in the conspicuously absent Microsoft Hololens and the popular design fictions of object and face recognition are emerging.

That is unless you are a brave early adopter, developer, or enterprise client. The fact that there was an entire Enterprise track and Daqri’s release of an AR-equipped construction/logistics helmet made it clear that the consumer market, much more prevalent last year, has clearly been placed in the long-term. For now, consumer/artistic AR is largely confined to the handheld device, as experienced through Will Pappenheimer’s “Proxy” at the Whitney Museum of American Art or Crayola’s “4D coloring books” in which certain colors serve as AR markers. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as an audience is likely to have a device that can run your app through which they can experience the art. As an aside, this is the reason why I chose to use handhelds for my tapestry work – imagine trying to experience a 21’ tapestry with a desktop using a 6’ cord! At this point, clarity and function, both partially dependent on computer power, have created a continuum from strapping your iPhone to your forehead like a jury-rigged Oculus for under $50, to potentially using a messenger bag with the Meta at $512, to the expensive ($2750), hot, but elegant ODG glasses you might try on if you visit the International Space Station.

While discussing the general shape of technology gives a context for its content and application, a media tool is often only as good as its app. Without meaning to show favoritism, Mark Skwarek’s NYU Lab team has been going outstanding work from a visualization of upcoming architectural developments to a surprising proof of concept for a landmine detection system, which I thought was amazing. Equally innovative was the VA-ST structured light headset for the visually impaired, which has several modes for different modes of contrast. These alternate methods not only was surprising in terms of application and possible creative uses but also changed my perception of AR as possessing photorealistic, stereoscopic overlays.

Other novel applications included National Geographic’s AR jigsaw puzzle sets, of which I saw the one outlining the history of Dynastic Egypt. I felt that if I were a kid, building the puzzle and then exploring it with AR would seem magical. There are other entertainment and experimentation platforms coming online like Skwarek, et al’s “PlayAR” AR environmental gaming system. But one platform I want to hold accountable for still being in late beta is the” LyteShot” AR laser tag system, which got an Auggie Award this year. My pleasure in the system is that the “gun” per se is Arduino-based, meaning that it could be a maker’s heaven. It uses the excellent mid-priced Epson headset, but at this time it is used primarily for status updates although there is a difference between AR and a heads-up display. So, from this perspective, it means that there are some great platforms getting into the market that are highly entertaining and innovative, but there are a few bugs to work out.

For the past thousand words or so I have been talking about the industry and applications of AR, but for me, my “soul”, if you will, set on fire during the “idea” panels and keynotes. For example, on the first day, Steve Mann, Ryan Janzen and the group at Meta had a workshop to teach attendees how to make “Veillometers” (or pixel-stick like devices to map out the infrared fields of view of surveillance cameras. Mann, famous for creating the Wearable Computing Lab at MIT and being Senior Researcher at Meta, still seemed five years ahead of the pack, which was refreshing. Another inspirational talk was given by one of the progenitors of the field, and inaugural Auggie Award for Lifetime Achievement, Tom Furness. His reflection on the history of extended reality, and his time in the US Air Force developing heads-up AR was fascinating. But what was most inspirational is that now that he is working on humane uses for augmentation systems such as warping the viewfield to assist people with Macular Degeneration. This, in my opinion, is the real potential of these technologies. In fact this array of keynotes was incredible, with Mann, Furness, the iconic HITLab’s Mark Billinghurst, and science fiction writer David Brin, (who comes off near-Libertarian) gave vast food for thought.

Every year, the Augmented World Expo gives out the “Auggie” awards for achievements in technology, art, and innovation in AR. I think it should be noted that the Auggie is probably the world’s most unique trophy, consisting of a bust that is half naked skull and half fleshed head with a Borg-like lens with baleful eye wired into that head. The Auggie is another aspect of AWE that signals that the world of Reality media is still a bit Wild West.

There are several categories from Enterprise Application to Game/Toy (LyteShot having won this year), and many of them are largely of interest strictly to developers. For example, the fact that Qualcomm’s Vuforia development environment won three years in a row gives hint to its stability in the market, and Lowe’s HoloRoom is a wonderfully strange mix between Star Trek and Home Improvement. The headset winner was CastAR, a projective/reflective technology where polarized projectors were in the headset instead of cameras, which worked amazingly well. The other winners were gratifyingly humane applications such as Child MRI Evaluation and Next for Nigeria (Best Campaign). The prizes impressed on me that the community, or part of it, “got it” in terms of the potential of AR to help the human condition, which is perhaps a “superpower” that the conference framed itself under.

Being that I am writing this for an art community it would be of interest to know where the art was in all of this. The Auggies have an Art category, as well as a gala between the end of the trade show events and the Auggie Awards. The pleasant part about AWE’s nominations for the best in AR art is that those works have integrity. Manifest.AR regular Sander Veerhof was nominated for his “Autocue”, where people with two mobile devices in a car can become the characters of famous driving dialogues (“Blues Brothers”, “Pulp Fiction”, “Harold and Kumar”). Octagon’s “History of London” is reminiscent of the National Geographic puzzles, except with far greater depth. Anita Yustisia’s beautiful “Circle of Life” paintings that were reactive to markers were on display in the auditorium but, besides a Twitter cloud and a Kinect-driven installation, the art was swamped by the size of the auditorium.

The winner of the art Auggie, Heavy & Re+Public’s’ “Consumption Cycle”, (which this writer saw at South by Southwest Interactive) was a baroquely detailed building sized mural of machinery and virtual television sets. I feel a bit of ambivalence about this work, as Heavy’s work tends to rely on spectacle. Of the lot I felt it did deserve the Auggie, purely for its execution and the effective use of spectacle. But with the emerging abilities of menuing, gesture recognition, and so on, I felt that last year’s winner, Darf Designs’ “Hermaton”, employed the potentials for AR as installation in a way that was more specific to the medium.

Yes, but it was in a much smaller area than the AR displays. There were standout technologies, like the Chinese Kickstarter-funded FOVE eye-tracking VR visor, a sensor to deliver directional sound, and Ricoh’s cute 360 degree immersive video camera. The Best in Show Auggie actually went to a VR installation, Mindride’s “Airflow”, where you are literally in a flying sling with an Oculus Rift headset. Although a little cumbersome, it was as close to the flying game in the AR design fiction short, “Sight”. So, in a way, the ideas of near-future design and beta revision culture are still driving technology as surely as the PADD on Star Trek presaged the iPad.

This year’s AWE/UploadVR event showed that reality technology is emerging strongly at the enterprise level and it’s merely a matter of time before it hits consumer culture, but it’s my contention that we’re 2-4 years out unless there’s a game changer like the Oculus for AR or if the Meta or ODG get a killer app, which is entirely possible. So, as the festival’s tagline suggests, are we ready for Superpowers for the People? It seems like we’re almost there but, like Tony Stark in the beginning, we’re still learning to operate the Iron Man suit, sort of banging around the lab.

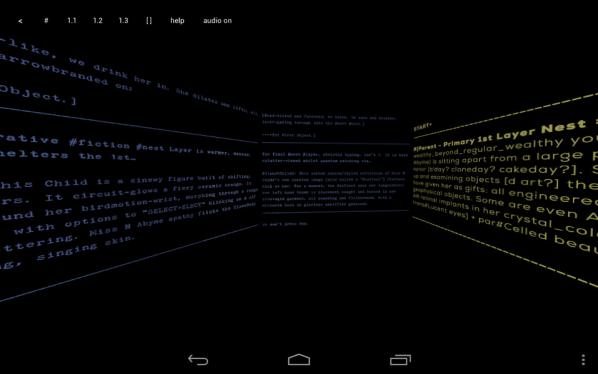

#Carnivast (Windows and Android apps, 2012) Mez Breeze and Andy Campbell.

Behind the rollercoaster hype cycle of Virtual Reality (VR) over the last quarter of a century, artists have kept working with VR as an increasingly mature medium. Realtime interactive 3D computer graphics is the most visually immersive medium for illusion in art, and text is the most imaginatively immersive. Both have been used to create virtual reality, with 3D virtual worlds in the case of the former and text-based worlds such as MUDs, MUCKs and MOOs in the case of the latter. They might appear to clash but there is a long history of 3D VR that incorporates text into or as its spatial environment.

I reviewed Mez Breeze’s book “Human Readable Messages”, which collects Mez’s “Mezangelle” micro net.text artworks, for Furtherfield here and wrote:

Mezangelle surfaces and integrates the hidden aesthetics of computer mediated human activity, setting computing and human language in tension and synthesizing them. It expands the expressive possibilities of text and is a form of realism about the conditions in which human reading is currently flourishing. “Human Readable Messages” provides an ideal opportunity to familiarize ourselves with Mezangelle in the depth that it deserves and rewards.

Collected in book form, the ephemerally distributed but thoughtfully crafted code-like text of Mezangelle becomes a book of days. Placing the avowedly low-bandwidth textuality of Mezangelle into virtual space might seem perverse, but that is what the App “#Carnivast”, produced with Andy Campbell, does very successfully.

Launching #Carnivast displays a virtual world looking like the insides of a nebula rendered in cheesecloth, accompanied by a glitchy, breathy, echoey, wavey, phaser-y, stringy soundscape. Superimposed over this in white formal capital san-serif type is the hashtag title “#CARNIVAST”. To the top left of the screen are some small button controls. Warm autumnal evening motes of colour flicker slowly across the view as the virtual world rotates slowly giving a combined impression of immensity, solidity, weight, and atmosphere. The textures on the surfaces of the world (or that are the surfaces of the world) slide slowly over each other creating interference patterns.

It’s a sensuous world, although not entirely a comfortable one, and one that invites exploration of its depths, or at least a closer look at its surfaces. The motes and the breathing are reminiscent of Char Davis’ ambitious “Osmose” (1995), the aqualung-controlled immersive virtual forest environment.

Selecting a world from the buttons and exploring it by swiping and pinching shows that the texture of the surfaces of the virtual world is Mezangelle, undulating over and through the world in a way reminiscent of some of the scenes from Laurie Anderson’s interactive CD-ROM “Puppet Motel” (also 1995) or of Michael Takeo Magruder’s VRML visualizations. The finesse of the text and the undulating environment contrast with Jeffrey Shaw’s “Legible City” (1989), a virtual environment of larger-scale text, Barbara Kruger’s Futura gallery installations, or the jagged phosphor green glow of Neo’s view of the underlying code of reality in the Matrix.

#Carnivast is very much its own experience, a series of distinctive spaces to float in. The first and third world are curvilinear and warmly coloured, the first feels like the interior of a nebula or a tokamak, the third feels like the inside of a cell or an atom. The second world is rectilinear and more acidicly coloured, closest to traditional imaginings of cyberspace. They are all meditative spaces, somewhere to spend time outside of the everyday world and to reflect. Mezangelle is an unlikely construction material for such a space, it demands too much attention to be decorative and contains rough ASCII symbols that contrast with the smooth curves or rectilinear forms of each space. It exists in tension with the surfaces of the virtual worlds, and it is this that gives #Carnivast its conceptual energy.

If you’re unfamiliar with Mezangelle, the [] button switches the screen to a rotating carousel of panels of coloured Mezangelle text that you can swipe through. Mezangelle is personal expression in an impersonal style with a social context. The geometry of the virtual spaces of #Carnivast is a substitute for the latter, and it creates an unlikely but compelling allegorical visualization of the flow of Mezangelle through mailing lists and blogs. It is a model of the social and conversational Internet rather than its technological infrastructure.

#Carnivast is finely tuned to make a space that you can lose all sense of time and self in as you explore it. As well as running on Windows PCs it works well on different sizes of portable device (I tried it on a phone, on a small tablet and a 9 inch tablet), and would work well large-scale in a gallery. How I would love to see it is modified to work with the Oculus Rift, the new consumer stereo vision head-mounted display (HMD). A Rift-enabled #Carnivast would afford a less constant opportunity of escape than the mobile version, but would be even more immersive. It’s a shame that the software is proprietary (closed source), as otherwise the community could add that feature.

#Carnivast is a mature VR artwork that represents an immersive extension of the strategies of Mezangelle into an exploration of virtual and network space. Explore it in evenings at the desktop, or keep it on your phone and get away from commuter noise and crush whenever you need to. It is a meditative experience deepened through restraint in its choices of navigation and materials and through fine tuning of its aesthetics and experience.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Dual

Nottingham Playhouse

5 September – 30 October

After a glorious false start in the 1990s, the previously over-hyped technologies of virtual reality have been quietly reclaimed in a more sustainable and democratic way through Free Software and Open Source hardware. The show “Dual” at Nottingham Playhouse showcases art that mostly uses these new technologies. A theatre is the perfect setting for the reality play of virtual reality. Curatorial collective The Cutting Room (Clare Harris and Jennifer Ross) have organized the funding, production, and presentation of artworks that mix the virtual and the real in creative ways.

Michael Takeo Magruder’s “Deconstructed Metaverse” (with Drew Baker and Erik Fleming), 2012, is installed on the upper landing of the theatre. The windows on the landing have been glazed with images of warmly coloured softly undulating colours. On closer inspection they are pixellated and have endless lines of computer code superimposed over them in small white type. The code is XML representing a virtual world, and that virtual world can be seen and interacted with on monitors in front of the windows. They display a ceiling-less ultra-modern rotunda with windows glazed in images of the views that could originally be seen through the real windows that are now glazed with images of the site-specific virtual world.

The first, smaller, monitor sits on a plinth alongside the circuit board that runs the virtual world using OpenSim under GNU/Linux from a single USB memory stick. You can use a keypad to explore the world, your presence there represented by a generic default human avatar that walks and flies around the island. Or you can visit the virtual world over the Internet. In either case, a large screen further along shows a rotating view of the island, its architecture and inhabitant(s).

Magruder has worked with virtual environments since the VRML era, and “Deconstructed Metaverse” continues some recurring themes while bringing them to a new level. There are multiple layers of reality and presence to this work that the viewer can find themselves looking into and out from, relating to other onlookers as part of the audience or part of a performance in the virtual world themselves.

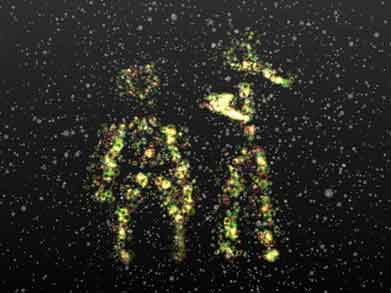

Brendan Oliver’s “Particulation” uses a Microsoft Kinect to capture the poses and motion of pairs of patrons walking through the Playhouse’s ground floor bar. A laser-scanning motion tracker and the software to process its input would have been unobtainable for most artists a decade ago. Oliver makes good use of hardware that was liberated against the wishes of its manufacturers and of software frameworks that are shared more freely.

Oliver uses them to capture and evoke the movements of two people who may not realise that they are the inspiration for the visual art on the wall. They are translated into a particle system of bubbling circles of light projected just far enough away from the sensor that monitors them that the connection between captured movement and animated image is not immediately obvious from all angles. Particulation has the feeling of joyous discovery and exploration that the best interactive multimedia art can bring to a space.

Below ground, “Mirror On The Screen” by Charlotte Gould and Paul Sermon uses similar technology to Deconstructed Metaverse to create a pocket universe of symbolic scenery and objects from children’s stories. In order see the screen presenting the virtual world and use the keypad to move your avatar around it you must stand in front of a printed backdrop where you are watched by a webcam. The resulting video stream is fed into the virtual world and superimposed onto cracks in its reality.

In addition to seeking the highest place in the forest, the edges of the world, and all the objects and characters within it, you find yourself hunting your own reflection. The tables are turned as the avatar you are watching starts watching you, and your purpose becomes seeking out further reflections. The setting of the theatre puts the viewer in a frame of mind open to the drama of the virtual world and its looping back on reality. Far from jolting you out of the experience, suddenly being faced with your own image in the virtual world draws you in further.

Finally, Kim Stewart’s “Sigma 6” is a 3D computer animated film set in a dystopian high modernist moonbase-like environment of harsh architecture and harsher treatment. The virtual world-like quality of the animation, and the avatar-like quality of its persecuted protagonist have their reality punctured in a way that continues the theme of mixed realities in a way that turns towards body horror.

These common themes of blurring virtual environments with real bodies and places allow the works to complement and distinguish themselves from each other artistically and technically. The Cutting Room are to be applauded for assembling such a thematically tight and technologically competent show that both serves and is served so well by the context of the institution that it is staged in.

http://www.nottinghamplayhouse.co.uk/about-us/the-cutting-room/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.