Buy Now and use code: CSF19ASRA for a 30% discount

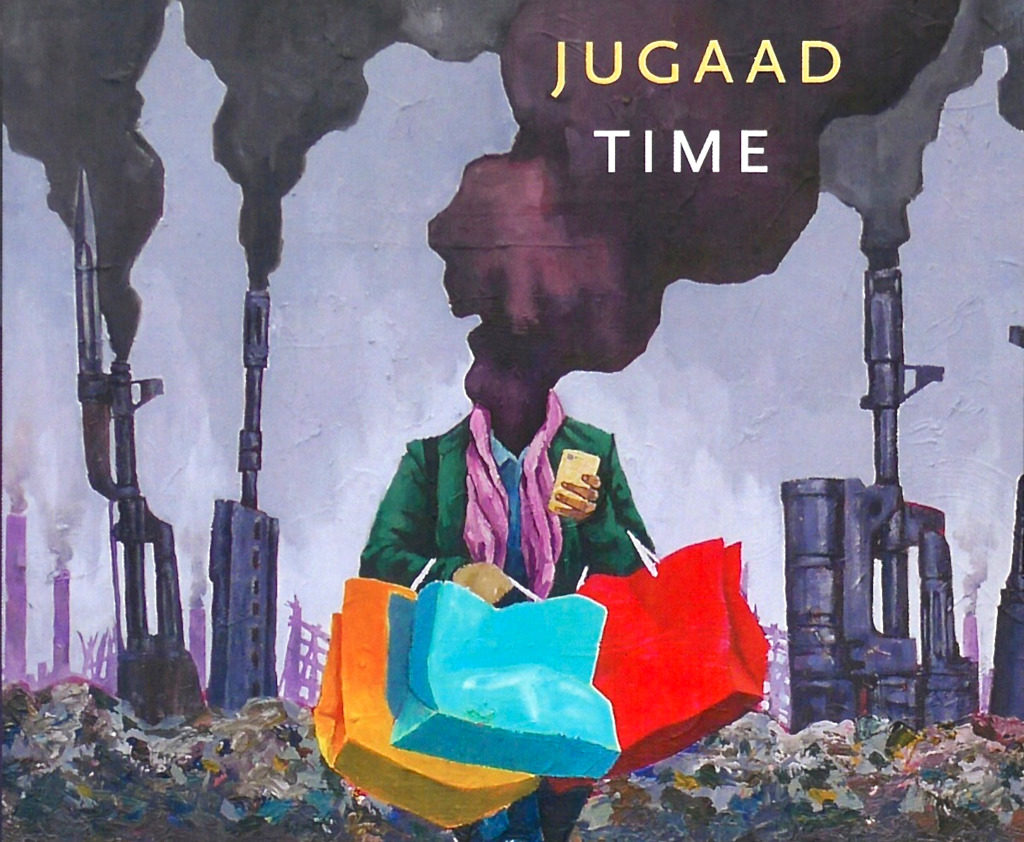

In India, the practice of jugaad—finding workarounds or everyday, usually non-technical hacks to solve problems—emerged out of subaltern strategies of negotiating poverty, discrimination, and violence. Yet it is now celebrated in management literature as ‘disruptive innovation’. In this book Rai considers how these time-efficiencies always exceed their role in neoliberal and authoritarian postcolonial economies and are put into motion by subaltern practitioners themselves.

On Sat 27 Apr from 14.00-16.00 Rai will introduce this important work to guests followed by a Q and A session with Furtherfield Co-Founding Director, Marc Garrett – with plenty for time for discussion.

This event is hosted at Furtherfield Commons in Finsbury Park* and has been supported by the Borderlines Research Group in Creative Economies and Postcolonial Intersectionality at Queen Mary, University of London.

“This original and innovative work will enable a new and perhaps paradigm-shattering interpretation of the coimplication of digital assemblages, temporality, and affect. Drawing on a rich ethnographic archive, Amit S. Rai is deeply sensitive to how gender, class, and caste are implicated in emergent techno-perceptual assemblages. His invaluable book is also an effective antidote to the Eurocentricity of digital media studies.” — Purnima Mankekar, author of Unsettling India: Affect, Temporality, Transnationality

“Jugaad Time is an important intervention into cartographies of postdigital media cultures. By drawing on the specificity of South Asian cultures, it enriches our understanding of the heterogeneity of these processes. The postcolonial study of media technologies is a vibrant and crucial field of inquiry; Amit S. Rai’s outstanding work is an essential contribution to global approaches to new media scholarship.” — Tiziana Terranova, author of Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age

The event form parts of Furtherfield’s 2019 programme Time Portals.

Octavia E Butler had a vision of time as circular, giving meaning to acts of courage and persistence. In the face of social and environmental injustice, setbacks are guaranteed, no gains are made or held without struggle, but societal woes will pass and our time will come and again. In this sense, history offers solace, inspiration, and perhaps even a prediction of what to prepare for.

The Time Portals exhibition, held at Furtherfield Gallery (and across our online spaces), celebrates the 150th anniversary of the creation of Finsbury Park. As one of London’s first ‘People’s Parks’, designed to give everyone and anyone a space for free movement and thought, we regard it as the perfect location from which to create a mass investigation of radical pasts and futures, circling back to the start as we move forwards.

Each artwork in the exhibition therefore invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

*Please not this is a separate building to our Gallery and is at the Finsbury Park station entrance to the Park.

In 2019 we celebrate the 150th anniversary of Finsbury Park, and we time travel through its past and future with the launch of our Citizen Sci-fi programme and methodology. Dominant sci-fi franchises of our time, from Black Mirror to Westworld, have captured popular attention by showing us their apocalyptic visions of futures made desperate by systems of dominance and despair.

What is African-American author, Octavia E. Butler’s prescription for despair? Sci-fi and persistence. Sci-fi as a tool for getting us off the beaten-track and onto more fertile ground, and persistent striving for more just societies.The 2015 book Octavia’s Brood honoured her work, with an anthology of sci-fi writings from US social justice movements and this inspired us to try a new artistic response to the histories and possible futures of Finsbury Park.

Furtherfield’s Citizen Sci-Fi methodology combines citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

Each artwork in the forthcoming exhibition invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

So where do we start? Last year we invited artists, academics and technologists to join us in forming a rebel alliance to fight for our futures across territories of political, cultural and environmental injustice. This year both our editorial and our exhibition programme are inspired by this alliance and the discoveries we are making together.

To kick off this year’s Time Portals programme at Furtherfield, in April we will host the launch and discussion around Jugaad Time, Amit Rai’s forthcoming book. This reflects on the postcolonial politics of what in India is called ‘jugaad’, or ‘work around’ and its disruption of the neoliberal capture of this subaltern practice as ‘frugal innovation’. Paul March-Russell’s essay Sci-Fi and Social Justice: An Overview delves into the radical roots and implications of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818). This is a topic close to our hearts given our own recent exhibitions Monsters of the Machine and Children of Prometheus, inspired by the same book. Meanwhile we’ve been hosting workshops with local residents exploring our visions for Finsbury Park 150 years into the future. To get a flavour of these activities Matt Watkins’ has produced an account of his experience of the Futurescapes workshop at Furtherfield Commons in December 2018.

In May we will open the Time Portals exhibition which features several new commissions. These include Circle of Blackness by Elsa James. Through local historical research James will devise a composite character to embody the story of a black woman from the locality 150 years ago and 150 years in the future. James will perform a monologue that will be recorded and produced by hybrid reality technologist Carl Smith and broadcast as a hologram inside the Furtherfield Gallery throughout the summer. While Futures Machine by Rachel Jacobs is an Interactive machine designed and built through public workshops to respond to environmental change – recording the past and making predictions for the future while inspiring new rituals for our troubled times. Once built, the machine occupies Furtherfield Gallery, inviting visitors to play with it.

Time Portals opens on May 9th (2019) with other time traveling works by Thomson and Craighead, Anna Dumitriu and Alex May, Antonio Roberts and Studio Hyte. Visitors will be invited to participate in an act of radical imagination, responding with images, texts and actions that engage circular time, long time, linear time and lateral time in space towards a collective vision of Finsbury Park in 2169.

From April onwards, a world of activities, workshops with local families and their enriching noises, reviews, interviews and an array of experiences will unfold. Together we dismiss the dystopian nightmares and invite communities to join us in one of London’s first “People’s Parks” to revisit and recreate the future on our own terms together.

Marc Garrett will be interviewing Elsa James, about her artwork Circle of Blackness, and Amit Rai about his book Jugaad Time. Both will soon be featured on the Furtherfield web site.

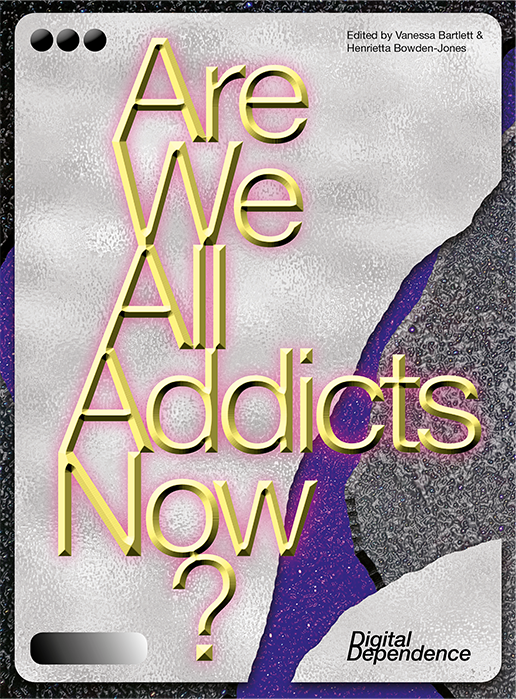

The interview is taken from the recently published book Are We All Addicts Now? Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, Liverpool University Press, 2017, and published with permission from the publisher. Available from the LUP website here – the interview is published in parallel with the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? at the Furtherfield Gallery, London 16 September – 12 November 2017.

Ruth Catlow: In your exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? That opens at Furtherfield, Autumn 2017. You will be presenting a number of works and installations made in response to your research into online addictions. What prompted your interest in this matter?

Katriona Beales: I have insomnia on and off — like a lot of precarious workers. And to deal with being awake for long-stretches at night I go online, parse hundreds of hyperlinks, images, videos. It’s like an out of body experience: I detach, temporarily, from anxieties, pressure, claustrophobia via total preoccupation. Reflecting on these experiences caused me to question whether there was something inherently ‘addictive’ about the conditions of the digital. My research has developed to look at the burgeoning field of neuromarketing and how much online content is ‘designed for addiction’ (to borrow the title of Natasha Dow Schüll’s scorching analysis of machine gambling in Las Vegas). [

note]Natasha Dow Schüll, Addiction By Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).[/note] 1] Gamification strategies and various psychological techniques such as variable reward (originally employed in the casino) are now utilised to mass effect on social media platforms, search engines, email accounts, and news sites.

RC: Can you give us an example of digital content, an interface or a device that you personally experience as addictive?

KB: I find the infinite scroll function on sites like Instagram and Twitter very compulsive. It removes the natural breaks that are built into technologies like the book, with chapters starting and ending. Then again, I used to be a compulsive reader and now I am a compulsive scroller… But I keep circling back round to think about the specific qualities of the conditions of the digital. The infinite, hyperlinked and networked nature of online content means scrolling, scrolling, scrolling never needs to end. There is also a correlation between these repetitive physical actions and meditative type states.

RC: Yes, this connects with theories of flow employed in game design. The idea is to design activities that produce the fulfilling feelings of focus, and to minimise a questioning of the context or frame of play. And there is very little critical discussion in mainstream culture about the gamification of everything, which replaces individual agency with a kind of soft coercion. It’s problematic because the less we notice how our attention and experiences are being harnessed by external forces (commercial or state based), the harder it is to connect and collaborate with others outside the given frames.

KB: Totally. I like your phrase ‘soft coercion’ because I think that sums up nicely what I’ve found troubling. Take this quote from Nir Eyal: “Variable schedules of reward are one of the most powerful tools that companies use to hook users… levels of dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward. Introducing variability multiplies the effect, creating a frenzied hunting state… When Barbra lands on Pinterest, not only does she see the image she intended to find, but she’s also served a multitude of other glittering objects… Before she knows it, she’s spent 45 minutes scrolling.” [2]

RC: We initially had reservations about applying the concept of addiction to internet usage, partly because the addiction label is usually used to attach blame to individuals. However, after conversation it became clear that you are exploring a political question. Why is the concept of addiction important to you?

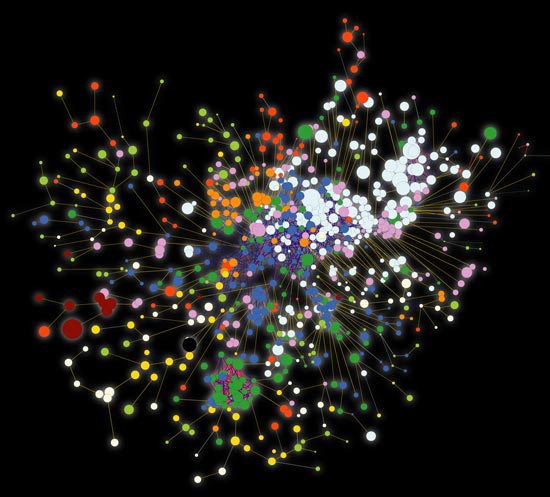

KB: Too much discussion about addiction is focused on the responsibility of people to help themselves. The fact that many can’t is often seen as a kind of moral failure. There’s also the disputed status of internet addiction in itself as documented by Mark D. Griffiths and his colleagues in their contribution to this book. We can’t pretend that there aren’t lots of people out there experiencing unhealthy and compulsive relationships to their technologies. But what kind of language is most appropriate to define this? What I am interested in is the phenomenon of what could be understood as addictive behaviours (including my own) being normalised in relation to digital devices. Kazys Varnelis [3] describes network culture as demanding connectedness, with power concentrated in nodes of hyper-connectivity. The more views, the more likes, the more power is accrued. Addictive behaviour is both normalised and valorised in late capitalism as it is associated with the public performance of productivity. Whilst these actions appear to be the choice of individuals, how much is due to the influence of mechanisms and systems of control? Ultimately, I am interested in the idea of the addict as a perfect capitalist subject. However, can we/I be both active-users and critical participants? I am concerned about how many of these platforms function as closed systems in which we contribute (without remuneration) our creative and emotional labour and yet can’t shape the conditions in which it is displayed, performed and monetised.

RC: You have collaborated with scientists as well as other artists and curators. How has this worked and what have these collaborations produced?

KB: The space of art offers an opportunity to tap into diverse fields of research, as a kind of (un)informed amateur. I find a Rancièrian strategy of ‘deliberate ignorance’ liberating. As an artist, I find myself in a position where I can turn my lack ofspecialist knowledge in fields like neuroscience into a kind of asset. I’m not answerable to a canon so can make unorthodox connections. In 2012, I started a conversation with clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones. Henrietta is fascinating as she started the first NHS clinic for problem online gambling and is now one of the leading experts in the field of online behavioural addictions. My collaboration with Henrietta has flourished, I think, because there is a recognition that there is a mutual benefit from the conversation but not an ownership or entitlement to each other’s outcomes.

RC: How does your work deal with the relation between physical and virtual presence?

KB: I am a tactile person, the sort who goes into a shop and strokes things with their face. I am fascinated by how digital devices act as portals into virtual worlds but often their own physicality isn’t dwelt on. Yet these devices connect us in a very tangible way to a globalised workforce and unethical labour practices. My iPhone has parts in it that were constructed by hand in an environment that resembles the Victorian workhouse more than the shiny aesthetics of the Apple store. These deeply dystopian factories create objects that seem so sleek, so smooth, so modern, as if they’ve arrived whole from outer-space. But they were created by workers who do compulsory over-time, sleep in triple bunk beds in small dorm rooms and aren’t even allowed to kill themselves. (I’m specifically referencing the suicide prevention netting that Foxconn put up around their buildings after a spate of mass suicides.)1 I’m emphasising physicality to connect my body lying in my bed to the body of someone bent over a production line; it is far too easy to dismiss the impact of our insatiable appetite for electronic goods.

RC: Your exhibition at Furtherfield is to be sited in the heart of a public park. How are you thinking about the relationship of digital devices to the natural environment?

KB: I continue using my smartphone when I step inside the park gates, in a continuum of ongoing augmented experiences where my physical environments are overlaid with digital content. The park acts as a fulcrum for changing understandings of leisure as labour, labour as leisure, and is the perfect site for encouraging reflection on this relationship. As part of this, Fiona MacDonald, who has been working with me on Are We All Addicts Now? as both a curator and an artist, is developing a mycorrhizal meditation piece, looking at network culture from an organic non-human perspective.

RC: I’d like to end with a description of some of the artworks and installations you are making, the materials you are using, and, in the context of the un-ideal strategies used by designers of mobile interfaces, what condition do you aspire to cultivate in visitors to your exhibition?

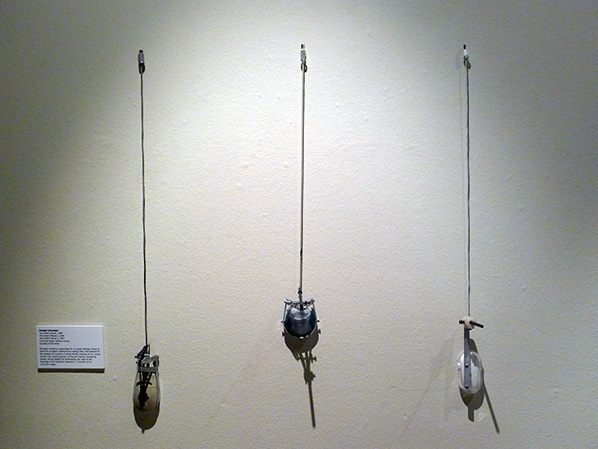

KB: I’m making a sunken plunge pool of a networked nest-bed, with glowing screens on which moths flutter embedded in glass orbs. Bed hangings embroidered with dichroic screens stripped from smartphones shimmer overhead, iridescent in the reflected light. I’m trying to communicate how seductive I find the screen in that dark, warm space – in those moments when I am more intimate with my device than my partner. There will be some participatory sculptures referencing pachinko and prayer beads, rhythmic movement, trance-like repetition, lulled into endless hypermobility in the closed systems of ‘communicative capitalism’. [5] I’m also working on some moving image works in which makeup is used as a tool to undermine eye tracking software, which I am hoping will incorporate some specialist hardware generating a live-feed of eye-tracking data from audience members. A series of table-top glass sculptures and embedded screens will explore interfaces that are ‘designed for addiction’ and the way notifications, for instance, are neuromarketing strategies seeking to ‘awaken stress — the mother of all emotions.’ [6] I’d like the audience to share in my disquiet, and hopefully leave encouraged to engage more critically with shaping their online worlds.

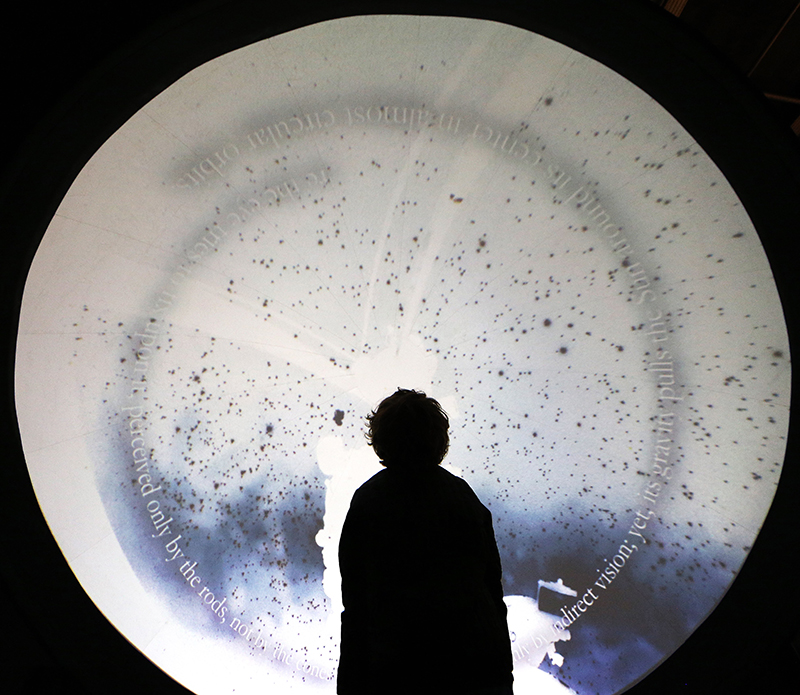

The New Observatory opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.

The exhibition, curated by Hannah Redler Hawes and Sam Skinner, in collaboration with The Open Data Institute, transforms the FACT galleries into a playground of micro-observatories, fusing art with data science in an attempt to expand the reach of both. Reflecting on the democratisation of tools which allow new ways of sensing and analysing, The New Observatory asks visitors to reconsider raw, taciturn ‘data’ through a variety of vibrant, surprising, and often ingenious artistic affects and interactions. What does it mean for us to become observers of ourselves? What role does the imagination have to play in the construction of a reality accessed via data infrastructures, algorithms, numbers, and mobile sensors? And how can the model of the observatory help us better understand how the non-human world already measures and aggregates information about itself?

In its simplest form an observatory is merely an enduring location from which to view terrestrial or celestial phenomena. Stone circles, such as Stonehenge in the UK, were simple, but powerful, measuring tools, aligned to mark the arc of the sun, the moon or certain star systems as they careered across ancient skies. Today we observe the world with less monumental, but far more powerful, sensing tools. And the site of the observatory, once rooted to specific locations on an ever spinning Earth, has become as mobile and malleable as the clouds which once impeded our ancestors’ view of the summer solstice. The New Observatory considers how ubiquitous, and increasingly invisible, technologies of observation have impacted the scale at which we sense, measure, and predict.

The Citizen Sense research group, led by Jennifer Gabrys, presents Dustbox as part of the show. A project started in 2016 to give residents of Deptford, South London, the chance to measure air pollution in their neighbourhoods. Residents borrowed the Dustboxes from their local library, a series of beautiful, black ceramic sensor boxes shaped like air pollutant particles blown to macro scales. By visiting citizensense.net participants could watch their personal data aggregated and streamed with others to create a real-time data map of local air particulates. The collapse of the micro and the macro lends the project a surrealist quality. As thousands of data points coalesce to produce a shared vision of the invisible pollutants all around us, the pleasing dimples, spikes and impressions of each ceramic Dustbox give that infinitesimal world a cartoonish charisma. Encased in a glass display cabinet as part of the show, my desire to stroke and caress each Dustbox was strong. Like the protagonist in Richard Matheson’s 1956 novel The Shrinking Man, once the scale of the microscopic world was given a form my human body could empathise with, I wanted nothing more than to descend into that space, becoming a pollutant myself caught on Deptford winds.

Moving from the microscopic to the scale of living systems, Julie Freeman’s 2015/2016 project, A Selfless Society, transforms the patterns of a naked mole-rat colony into an abstract minimalist animation projected into the gallery. Naked mole-rats are one of only two species of ‘eusocial’ mammals, living in shared underground burrows that distantly echo the patterns of other ‘superorganism’ colonies such as ants or bees. To be eusocial is to live and work for a single Queen, whose sole responsibility it is to breed and give birth on behalf of the colony. For A Selfless Society, Freeman attached Radio Frequency ID (RFID) chips to each non-breeding mole-rat, allowing their interactions to be logged as the colony went about its slippery subterranean business. The result is a meditation on the ‘missing’ data point: the Queen, whose entire existence is bolstered and maintained by the altruistic behaviours of her wrinkly, buck-teethed family. The work is accompanied by a series of naked mole-rat profile shots, in which the eyes of each creature have been redacted with a thick black line. Freeman’s playful anonymising gesture gives each mole-rat its due, reminding us that behind every model we impel on our data there exist countless, untold subjects bound to the bodies that compel the larger story to life.

Natasha Caruana’s works in the exhibition centre on the human phenomena of love, as understood through social datasets related to marriage and divorce. For her work Divorce Index Caruana translated data on a series of societal ‘pressures’ that are correlated with failed marriages – access to healthcare, gambling, unemployment – into a choreographed dance routine. To watch a video of the dance, enacted by Caruana and her husband, viewers must walk or stare through another work, Curtain of Broken Dreams, an interlinked collection of 1,560 pawned or discarded wedding rings. Both the works come out of a larger project the artist undertook in the lead-up to the 1st year anniversary of her own marriage. Having discovered that divorce rates were highest in the coastal towns of the UK, Caruana toured the country staying in a series of AirBnB house shares with men who had recently gone through a divorce. Her journey was plotted on dry statistical data related to one of the most significant and personal of human experiences, a neat juxtaposition that lends the work a surreal humour, without sentimentalising the experiences of either Caruana or the divorced men she came into contact with.

The New Observatory features many screens, across which data visualisations bloom, or cameras look upwards, outwards or inwards. As part of the Libre Space Foundation artist Kei Kreutler installed an open networked satellite station on the roof of FACT, allowing visitors to the gallery a live view of the thousands of satellites that career across the heavens. For his Inverted Night Sky project, artist Jeronimo Voss presents a concave domed projection space, within which the workings of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy teeter and glide. But perhaps the most striking, and prominent use of screens, is James Coupe’s work A Machine for Living. A four-storey wooden watchtower, dotted on all sides with widescreen displays wired into the topmost tower section, within which a bank of computer servers computes the goings on displayed to visitors. The installation is a monument to members of the public who work for Mechanical Turk, a crowdsourcing system run by corporate giant Amazon that connects an invisible workforce of online, human minions to individuals and businesses who can employ them to carry out their bidding. A Machine for Living is the result of James Coupe’s playful subversion of the system, in which he asked mTurk workers to observe and reflect on elements of their own daily lives. On the screens winding up the structure we watch mTurk workers narrating their dance moves as they jiggle on the sofa, we see workers stretching and labelling their yoga positions, or running through the meticulous steps that make up the algorithm of their dinner routine. The screens switch between users so regularly, and the tasks they carry out as so diverse and often surreal, that the installation acts as a miniature exhibition within an exhibition. A series of digital peepholes into the lives of a previously invisible workforce, their labour drafted into the manufacture of an observatory of observations, an artwork homage to the voyeurism that perpetuates so much of 21st century ‘online’ culture.

The New Observatory is a rich and varied exhibition that calls on its visitors to reflect on, and interact more creatively with, the data that increasingly underpins and permeates our lives. The exhibition opened at FACT, Liverpool on Thursday 22nd of June and runs until October 1st.

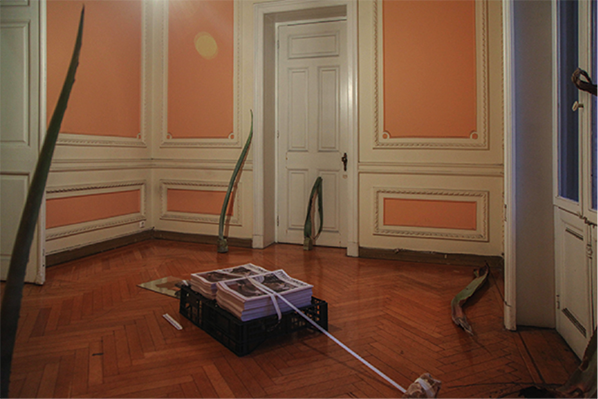

Walking off the Akadimias district and onto the steps leading up towards the entrance of building number 23, I am greeted by a large hall with high red ceilings. The hall is covered with lavish white and black dot marble, and there is a large staircase acting as a guide to the top floors of the manor-like building. This was the home for the Diplomatic Centre of the Third Reich, designed in 1923 by Vassillis Tsagris, and used until 2011 by the Foreign Press Correspondent Union after the Second World War. Since then it has stood derelict and dusty, but for one week, in parallel to the opening of documenta 14, it played temporary host to the artist-in-residence programme of Palais de Tokyo, alongside with Foundation Fluxum/Flux Laboratory, bearing the name Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Six visual artists in residence at Pavillon Neuflize OBC and eight contemporary Greek choreographers envision and fabricate a hybrid space whereby an experimental notion of a community is executed as a situation rather than as a subject. The visual artists and performers involved congregated together in Athens and on site for a two-week workshop in March in order to produce the works. The title, Prec(ar)ious Collectives, is a linguistic amalgamation of the adjectives ‘precarious’ and ‘precious’, implying the state of the collective that performs together.

The opening façade echoes with the humming and reverberated sound of Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos‘ Dusk and Dawn Look Just The Same (Riot Tourism), guiding us towards its installation room. The video installation stands above a mountain of blue powder in a room sectioned off with construction tape. The short sequence of about a minute and a half displays a group of hooded figures, dressed identically. As the soundtrack’s volume begins to escalate, the group progresses from walking to running on the uncannily void and ghostly streets of Athens. A city always bustling with noise is now at its most quiet and pubescent state of the day – dawn. The hooded figures run together and – even though it is in a disordered manner – command your attention and pensiveness until they all reach Omonia Square. The work demonstrates a resistance to a status quo which may be aligned with the political engagement within the city. This is not, however, done in an expected reactionary manner, but instead in a way that promotes uprising through the creation of a meditative state. One cannot help but watch Lemos’ work a couple of times more before leaving it behind and only then noticing the thundering beneath their feet.

This historic building has a basement and is the temporary home of Taloi Havini‘s performative work. The large-scale installation occupying four rooms consists of PVC vinyls, seemingly discarded or hung from the low ceiling. These PVC vinyls are lit by dispersed and differently coloured strings of light, some are red, others are purple and others are cream. The performance is underway and its performers dress themselves with the PVC vinyl and the lights and jolt their bodies vigorously to the rhythm of the thundering – sometimes in sync, sometimes not. The dark basement is transformed into a cavern of rhythmic delight alluding to a ritual where its power lies in the gathering of people.

As one inspects the garments of Wataru Tominaga and those who wear them, this synthesis of the PVC, the space and the performers as a gathering appears to be a motif. Tominaga created the garments during a preliminary workshop, with great care and appreciation of how he and others were to utilise them during Prec(ar)ious Collectives. Originally presented on mannequins before being worn and performed, the garments boast vivid colours and patterns, some of them containing animalistic features such as feathers or fur. Those who wear Tominaga’s work perform in such a way as to invent a new form of communication between themselves and their observers. They move and conjoin like animals, sometimes hiding underneath the fabric and at times evoking the traditional Japanese ‘snake dance’. The performance, being in a transitional space between the ground floor and the first floor, naturally spreads itself upstairs whereby the performers not only continue to wear the garments in obscure ways, but additionally interact with Yu Ji‘s agave plants and other objects.

Yu Ji‘s work, Lycabettus Tongue, Oliv Oliv and This is Good For You! Are formed by the use of displaced agave plants, half-fragmented found mirrors and lights. The agave plants interlock with various architectural patterns of the building such as stair banisters, whilst the mirrors and round-ball lights are positioned in ways offering various points of view for observation and appreciation of space. The work revitalizes the architecture of the building denoting its historical vitality and the synergy of the encompassing works into a haunting existence rather than an abandoned one. Here, haunting is used not for means of negative connotations but instead as a form of aloof yet introspective sensation, exasperated further with Lola Gonzàlez‘s video installation in the next room.

Lola Gonzàlez‘s Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw begins with its protagonists split into groups and observing the city of Athens from various points at the top of the hills. The groups begins to move, run and hop together towards a direction down the hill, whilst a chorus of droning voices begin to chant and harmonise. As the groups get closer and closer to the city, Gonzalez transforms the image into a complete inversion, like one you may find in negative photography. The chanting becomes louder as the three groups get closer and closer to their meeting point within the city – the exact space where the video is being showed. They are finally shown entering the building and making their way up the stairs to the room where they vocalize in unison until they fade away from our view. Now my hands are bleeding and my knees are raw alludes to an atmosphere in which the power of gathering together evokes a community whose intention is situated between an uncertain balance of peril and strength. It is the same kind of uncertainty that one finds when exploring the top floor of the building only to discover Thomas Teurlai‘s room of machines and looped functions.

On the top floor, there are still the remnants of neglect, rooms empty of anything but the garbage that piled up over the building’s six years of desertion. Thomas Teurlai‘s Score for bodies and machines consists of a room installation of two printers used by the performers to scan different parts of their bodies. These scans are then plastered on the wall whilst the fluorescent lights constantly trickle on and off. The two performers are attempting to archive as much of the movement involved in their choreography as possible. The looped function of copying and the crackle of its repetitive working-noises do not clash with the choreography but instead drive its energy.

Indeed, it may be the encounter between the building, the communal working spirit of the performers and the result of this effort that defines this rejuvenating energy as a fruitful rebirth of the building’s utility.

To find out more, read Chloe Stavrou’s recent interview with Fabien Danesi of Prec(ar)ious Collectives.

CS: Tell us a little bit about how the collaboration between Palais de Tokyo’s residency Pavilion Neuflize OBC and Fluxum/Flux Laboratory came about. Did this directly contribute to the hybrid of visual/dance performance art or was it the artists’ call?

FD: During two years, the Pavillon Neuflize OBC has worked with the National Opera of Paris for projects at the crossroads between contemporary art and choreography. We wanted to develop this perspective which is a kind of tradition in the history of the Pavilion (created in 2001), if we remember that our institution has a long interest for transdisciplinarity. So the hybridization between visual art and performance wasn’t the artists’ call. On the contrary, we asked them to step aside for collaborating with choreographers. It was really experimental for them.

CS: Neither Palais de Tokyo or Fluxum/Flux Laboratory are situated in Greece. What was the reason for its inception to take place in Athens? Was it because of the traffic Athens would see due to documenta 14 or was it a suggestion by Andonis Foniadakis, the choreographic director?

FD: Since its creation, Fluxum/Flux Laboratory has developed many dance projects in Greece. And it’s due to its founder, Cynthia Odier, that Ange Leccia and myself met Andonis Foniadakis. We started the dialog with Andonis right at the moment of his nomination as the Ballet Director of the Greek National Opera, o Athens appeared quickly as the perfect place for our collaboration. We decided just afterwards to take advantage of the presence of documenta 14 in the city.

CS: The result is quite impressive – specifically since, and correct me if I’m wrong – the work produced was created in only two weeks in March. How did you find the process of working and creating collaboratively in addition to being in an unfamiliar city?

FD: The residents came to Athens for the first time in November 2016. During the first week, we had met the choreographers and dancers but also people who are engaged in the artistic life of the city. We tried to understand and use the pulse of this specific urban energy. We visited some sites for the exhibition and began to question the relevance of our own presence here. The conversations with the choreographers permitted us to create a strong link with Athens and not feel like tourists. We came back for a three-week workshop in March, just before the opening of our show. Between these two stays, we discussed a lot and had decided to start from our situation with the desire to move away from an artificial subject. The notion of the collective seemed a good way of taking charge of what we tried to do – especially because the Pavilion tries every year to create a specific group that gives a specific form to its structure.

CS: Prec(ar)ious Collectives feels like it could be quite nomadic as it is in an unfamiliar environment; however nomadic does not mean it feels odd or out of place – in fact it felt quite the opposite. As a curator, how did you approach Athens and stay conscious of the context(s) surrounding it?

FD: The fact that we didn’t exhibit in a white cube or an artistic space helped us. When we decided to occupy this abandoned building on Akadimias Street, I was sure that we would be related strongly to the city and its history. The context wasn’t outside of the walls – it was here, with us. Of course, we were all conscious that we needed to stay in relation to what was happening in the city. That’s why nobody arrived with their work completed and done. The materials and the main elements of the creations were an artistic answer to this particular context.

CS: I am very curious about the building. I understand it used to be the Diplomatic Centre for the Third Reich during the Second World War. How did you become aware of its existence, and did your decision to curate Prec(ar)ious Collectives have anything to do with the building’s history? If not, what was the reason for selecting this building?

FD: In January 2017, the director of the Pavilion Ange Leccia was in Athens to present some of his work. He visited the exhibition organized by Locus Athens in this space and it impressed him quite a bit. We wanted to work in an abandoned site for underlining the economical and cultural situation in Greece. And Akadimias Street 23 seemed perfect. We didn’t choose it for its history, even if these multiple layers added some density to our proposal. For sure, the different atmospheres of the rooms immediately gave us the possibility to create dialogs between the works while preserving the integrity of each. So, it was a question of ambience in the sense of the architectural conditions aiding the experience of the audience.

CS: I found that a continuous theme within the exhibition was not only the creation of a utopic community, but also an ambience that generates a state of limbo – of transition. Was this a reference to the state of Athens or to the state of artistic production or work?

FD: The notion of limbo is stimulating. And it insists on our «spectral approach». It means that we have tried to give life to this abandoned building. And some installations can be described as floating. In Manolis Daskalakis-Lemos and Lola Gonzalez’s videos, for example, there is the idea of apparition. And even with Taloi Havini’s huge ephemeral camp, we can feel a sort of «in-between» space, archaic and futurist, protective and dangerous. Maybe it was a re-transcription of our impressions about Athens, so appealing and full of energy, but at the same time, so undermined by the political situation.

CS: As a final note, what is the next step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives after its brief residency in Athens? Are there any plans to simulate the experience, albeit differently, again in another context or place?

FD: There won’t be another step for Prec(ar)ious Collectives as a group exhibition. It was really the result of a one-month workshop. But it happens for the best that some encounters initiated in the Pavilion can be developed after the time of the residency.

CS: And any future projects that you will be a part of?

FD: On my side, I will develop a curatorial project next year in Los Angeles in the frame of FLAX residency. Titled The Dialectic of the Stars, I will organize several evenings in different institutions which will permit artists? to drift in the city from one site to another for catching some contradictory parts of the L.A. atmosphere. The idea is to mix French artists and Los Angeles-based artists and to trace a political and poetical constellation.

To find out more read Chloe Stavrou’s recent review: Community Situation: Prec(ar)ious Collectives and documenta 14

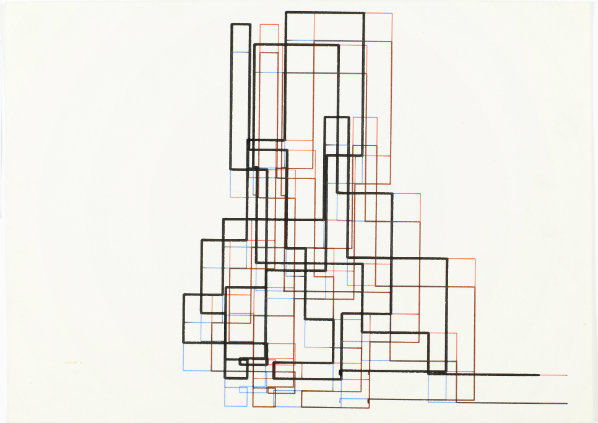

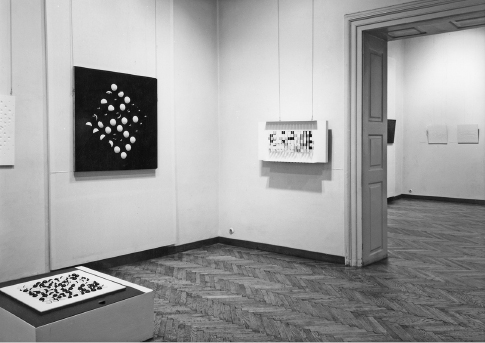

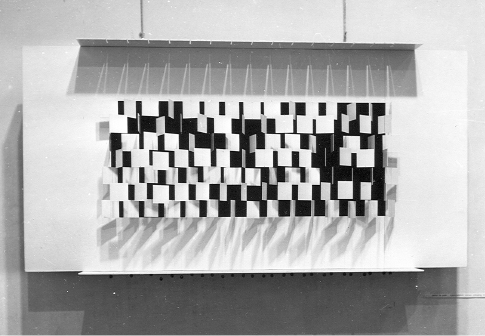

The book New Tendencies – Art at the Threshold of the Information Revolution (1961-1978) by Armin Medosch presents thorough research into the international New Tendencies movement that was active in the 60s and in the 70s. In his book, Medosch gave contextualisation of the New Tendencies movement and framed it in the political, social and cultural context of its time. The New Tendencies movement arose in a culmination of high modernism in the 60s, with its centre in Zagreb, Croatia, in former Yugoslavia. This country was itself a modernistic project of the 20th century. However, semi-peripheral in industrial development, the climate of modernism in Yugoslavia influenced art and culture and thus prepared conditions for the country to become a knot in a network of artistic centres of European Fordism like Milan, Munich, Düsseldorf and Paris. One of the first who restored the memory of New Tendencies was Croatian artist and curator Darko Fritz with his research Amnesia International, which transferred the memory of NT to the newer generations of Media Art practitioners.

The New Tendencies movement had momentum in the 60s, while in the 70s, it shared conceptual art’s crisis of faith in late modernism. In the 80s, New Tendencies was almost forgotten. Medosch writes that New Tendencies’ “politics of form” was strongly influenced by its disavowal of the artist as a producer of commodities for the art market”. For the first exhibition in Zagreb, artists consciously used inexpensive new materials and new media from mass production, such as punch cards, plastic ribbons, cardboard, and plywood. In the third New Tendencies exhibition in Zagreb in 1965, organizers wanted to create a new synthesis between the art they applied art through the creation of Multiples, as reproducible art, but this idea was not received well. They wanted to democratize art and were against the scarcity principle that was deeply embedded in the art system. Although ideas around the demystification of art were not new, there was a novelty in “the specific way New Tendencies tried to achieve this — through the formula of art as visual research.” Art was redefined as visual research, and mass production and abundance were not considered negative. Ideas of interactivity, the democratization of art and the participation of the public in New Tendencies exhibitions were sometimes seen as seductive, especially when, in the late sixties, political movements and counter-culture started to influence the art world and became much more explicit in demands for political and social change.

The book New Tendencies – Art at the Threshold of the Information Revolution (1961-1978) is valuable material for a non-western centric approach to the history of art (it is worth noting that the histories of computer and digital art are not exempt from western-centric historicization). Still today, there are many examples of ignorance of what was happening outside North America and Western Europe, despite more and more stories, research and documentation about post-WW2 art. Medosch is not looking for the “Other”, trying to fill the geo-holes in the history of arts, or fixing “colonial guilt”, but he is using New Tendencies as a case study of an art movement that connects the early history of art & media with social issues. As secondary, it came out that the centre of this movement was Zagreb and former Yugoslavia. However, non-intentionally, Medosch uncovers the story of the soft power of that time in Yugoslavia – an uncovering which proves thought-provoking as a counter to western-centrism.

As Medosch outlines, the Croatian artist and curator Darko Fritz was the first to suggest reading New Tendencies as a network – or rather a network of networks that included group Zero from Germany, the groups N and T from Italy, Equipo 57 from Spain, and Paris-based Group de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV), to name just a few. Also, in Zagreb, New Tendencies had direct precursors such as EXAT 51 or GORGONA, whose members had close ties with the movement.

The formation of groups and networking in New Tendencies includes two processes. The first is standard practice in art history: young artists gather to strengthen their position in art and the social system. The second also showed renewed trust in common destiny and solidarity, corrupted by collective totalitarian experiences and disappeared during and after WW2. New Tendencies artists are of a generation that renovated belief in social progress, common interest and direct democracy. Therefore some groups like GRAV, Equipo 57, and N experimented with collective authorship, a model that, for the market, is not easy to deal with. This group ethos was present in artistic practice and in curatorial and organizational practices. The curatorial boards of New Tendencies exhibitions and events engaged in joint decision-making, often actively communicating with artists about the content they produced. For example, the small details involved in artists filing “application forms” about themselves and describing their works was a self-managed bureaucratic procedure which developed into more complex research and decision-making.

New Tendencies artists embraced Fordist technological innovation; rather than opposing technological acceleration, as most other artists at that time were thinking of a future technological society beyond alienation and oppression. Similar to their “artistic relatives” Situationists, some NT artists used playful elements envisioning post-Fordist conditions where repetitive work was viewed as oppressive. In his book, Medosch analysed the similarities and differences between these two groups that shared much common ground.

In his book, Medosch emphasized the connection between social analysis and developed a critique of New Tendencies groups and new readings of Marx, particularly those of Operaismo in Italy and Praxis in Yugoslavia. A central element of these new readings was “Marx’s critique of commodity fetishism applied to artwork and its ideological function in the capitalist world.” Medosch intends to minimize the current tendency to re-inscribe movements that developed a half-century ago in favour of investigating theoretical frameworks and political conditions of that time.

In August 1968, in Zagreb, a symposium Computers and Visual Research was organized at the same time as the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition in London. The exhibition in Zagreb, called t-4 (Tendencies – 4) in 1969, followed the symposium and Cybernetic Serendipity, which was the inaugural moment of international computer art. The symposium Computers and Visual Research marked the line between the first phase of New Tendencies’ analogue “programmed artworks” (as Umberto Eco defines it in the exhibition catalogue) and the second phase in which NT embraced art that used computers.

Although Medosch’s idea was not to emphasize Yugoslavian context beyond the extent needed for general contextualization of the movement, the fact that Zagreb had the logistical, infrastructural and intellectual capacity to be the centre of the movement for almost 2 decades showed certain “properties” of Yugoslavia of that time. For the book’s readers in former Yugoslavian countries, the book brings certain discomfort since, after the Yugoslav wars in the nineties, there is a general tendency to forget the heritage of the Yugoslav modernist project. Also, the “eagerness” of activity in Zagreb could be because, after the breakup of Yugoslavia’s ties with Stalin in 1948, Zagreb wanted to restore connections with the cultural context of what historian Eric Hobsbawm called the “main mountain range or crest of European economic and cultural dynamism”, an area that encompasses Paris, the Rhine valley, north Italy, south Germany and Switzerland.

In a way similar to New Tendencies in the ’60s and ’70s, Media Art (a generic term that covers new media art, net.art, net cultures, and digital art at the end 90’s and beginning of 2000) experienced a “specific” relationship with the mainstream art system. The first thing that connects both New Tendencies and later Media Art is a reluctance to be incorporated into the contemporary art system. This uneasiness has fuelled recent debates ranging from considering that Media Art is part of the contemporary art system to opinions that Media Art is a completely different category. This relationship has similarities with that of the New Tendencies movement concerning the contemporary art system half a century ago. The other is something that is unfolding in front of our eyes, a kind of new Amnesia International 2.0, slowly covering memories of media art and culture of the 90s and early 2000.

Armin Medosch’s book makes a structural connection between early media art and culture and the media art of the 90s and early 2000s. Concepts of sharing, critique of the commodification of art objects, the de-elitization and democratization of art, demystification of art, and the embracing of discussion of pluralistic techno-political impacts of technology; these are common denominators that connect art at the threshold of the Information Revolution with the art of late Informationalism in the late 20th and early 21st Century.

Body Drift: Butler, Hayles, Haraway (Posthumanities)

Author Arthur Kroker. University of Minnesota Press (22 Oct. 2012).

Body Drift by Arthur Kroker, takes the work of three leading women thinkers as its main focus. It therefore would feel strange, before venturing on to the review, not to mention Marilouise Kroker, his wife and collaborator who he credits with shaping the critical direction of his thought “on bodies and power.” [1] Together Marilouise and Arthur Kroker have created an abundance of work in the fields of technology and contemporary culture. They both edit the peer publishing electronic journal CTheory founded in 1996. They co-authored the influential Hacking the Future (1996), and Marilouise Kroker has co-edited and introduced numerous anthologies including Digital Delirium (1997), Body Invaders (1987), and Last Sex (1993) and Critical Digital Studies: A Reader. Marilouise Kroker is Senior Research Scholar at the University of Victoria. A recent bio written about them says “Arthur and Marilouise Kroker are the hipsters of Canadian media theory.” [2]

Arthur Kroker is Canada Research Chair in Technology, Culture and Theory, Professor of Political Science, and the Director of the Pacific Centre for Technology and Culture (PACTAC) at the University of Victoria. His recent publications include The Will to Technology and the Culture of Nihilism: Heidegger, Nietzsche, and Marx (University of Toronto Press) and Born Again Ideology: Religion, Technology and Terrorism. Dr. Kroker’s current research focuses on the new area of critical digital studies and the politics of the body in contemporary techno-culture. http://web.uvic.ca/~akroker/

This review is written three years after the publication of the book but it feels even more relevant now than ever for reasons that will, I hope become plain…

Body Drift focuses on three major feminist theorists, Judith Butler, Katherine Hayles and Donna Haraway. They have had a deep influence on my own work and of course on media art culture through the years. They have profoundly altered our views on technology, feminism, queer theory, postmodernism, marxism, hacking, hacktivism, cybernetics, the Internet, network culture, politics and posthumaniism. Re-examining their critical perspectives and creative processes – assemblages, remixing and cyborgs- Kroker terms the emerging technological spectre body drift. He examines the connections between what he sees as Judith Butler’s postmodernism, Katherine Hayles’s posthumanism, and Donna Haraway’s companionism.

Through the spectrum of Body Drift he attempts to find a clearer understanding of the contemporary material body and its societal complexities. He views two opposing forces at work in body drift. One is, the continual disappearance of human things and values, alongside excluded ethnicities and outlawed sexualities. He connects this with an entrapment by social crisis in which actual democratic aspiration is dwindling. In parallel to this mass loss of our freedoms other factors are at work. He sees it as overall, and an eventual series and states of resistances. These are evolutionary forms of hybridity and as such are key paths for what he argues is the function of our posthuman condition. [3]

There are numerous techno-visions expounding how technology will change our lives and futures. What for me, separates a classic posthumanist and a critically aware posthumanist is that the latter is not only aware of the necessity of grass roots culture and inclusion of female voices, but is also critical of domination over others as key when engaging in the processes of innovation. Thus moving beyond existing frameworks that perpetuate patriarchal language, methods of centralization and colonial habits.

In his book You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto, Jaron Lanier described Ray Kurzweil’s excitement about The Singularity as apocalyptic. Lanier says “The coming Singularity is a popular belief in the society of technologists. Singularity books are as common in a computer science department as Rapture images are in an evangelical bookstore.” [4] Kurzweil’s digestible techno-bites fit well alongside big business and with Peter Diamandis a wealthy entrepreneur. Dr. Peter H. Diamandis and Dr. Ray Kurzweil co-founded the Singularity University. In To Save Everything, Click Here: Technology, Solutionism, and the Urge to Fix Problems that Don’t Exist, Evgeny Morozov writes that Diamandis “promises us a world of abundance that will essentially require no sacrifice from anyone – and since no one’s interests will be hurt, politics itself will be unnecessary.” [5]

In The Joy of Revolution Ken Knabb wrote, “Marx considered it presumptuous to attempt to predict how people would live in a liberated society. “It will be up to those people to decide if, when and what they want to do about it, and what means to employ.”” [6] Kroker says, “In my estimation, while Marx, Nietzsche and Heidegger may have provided premonitory signs of the charred landscape of the technological blast, it is the specific contribution of Butler, Hayles and Haraway to provide a deeply compelling account of the fate of the body in contemporary society.” [7] This includes how we evolve our Internet freedoms, surveillance, and cyber attacks in a post-Snowden world. While we’re, either reshaping or being reshaped through the constant production of new technologies and political re-invention, it is crucial that there exists regular critique reflecting on these influences and changes on people, animals, society, the planet, and the universe. Thankfully, Butler, Hayles and Haraway disrupt the normalization and dangerously hegemonic acceptance of ‘the male overlord and his machine’ over the rest of us.

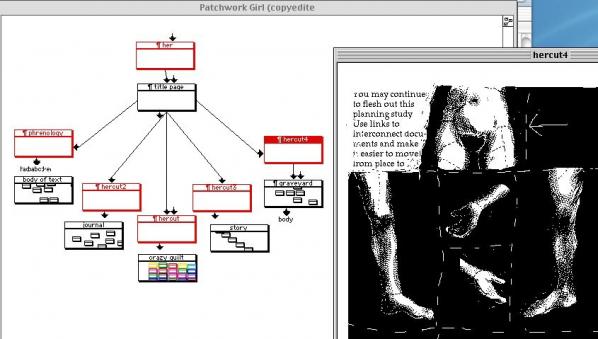

How our bodies and the idea of our bodies relate to this complex world is Kroker’s primary interest. In the introduction Kroker says that we no longer inhabit a body in any meaningful sense of the term but rather occupy a multiplicity of bodies – imaginary, sexualized, disciplined, gendered, laboring technologically augmented bodies. [8] Hayles has not only bridged the gap between science and literature, but also media art. In 2000, Hayles wrote an insightful piece on Patchwork Girl, an artwork made by Shelley Jackson in 1995, a hypertext fiction and remix of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. When discussing Jackson’s piece Hayles said, “As the unified subject is thus broken apart and reassembled as a multiplicity, the work also highlights the technologies that make the textual body itself a multiplicity.” [9]

Kroker says, “”Like Heidegger before her, Hayles refuses to privilege either interpretation to the exclusion of its opposite, preferring a form of thought similar to “pendurance,” that moment when, in the folded twists of complexity theory, “one comes over the other, one arrives in the other.”” [10] In an interview with Josephine Bosma on the Nettime email list, in Nov 1998, Hayles said “There may be other ways to think about the subject that don’t find themselves first and foremost on this notion of ownership. New technologies open up possibilities for rethinking other ways to begin to construct the subject.” [11] Krokers sees Hayles as providing us with the digital alphabet to explore the complexity and connections of technopoesis. “To read Hayles is, in fact, to begin to experience the fractures, bifurcations, and liminality that stretches across the skin of posthuman culture.” [12]

Donna Haraway in her introduction to A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century, in 1985 she said, “Though both are bound in the spiral dance. I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess.” This unsettled many feminists at the time. Haraway was not interested in reclaiming what she saw as a lost ideal based on matriarchal values. Instead, she wanted women to re-invent and create their own versions of what a female could be or not be, by playfully exploiting the cyborg myth and concept in the here and now. [13] This reconstruction of the woman, Kroker says, poses particular twists and knots, and contradictions. He emphasises that we’re not discussing a traditional form of feminism but a hybrid vision of feminism. [14]

“Not waiting passively for the capricious experience of biotechnology to produce spliced bodies, Haraway has made of her own mind a biopolitics on creative hyperdrive. Deeply immersed in the (bio)scientific disciplines, always distancing herself from seductions of technological representationality by feminist difference, continuously provoking boundary breakdowns in her own thought by refusing to assent to an anthropomorphic species-heirarchy, Haraway is a theorist of the splice.” [15] Kroker (2012)

Kroker moves on from Haraway’s concepts on the cyborg to her later inter-species theory. He tries to untangle the complexity of her personal, political and theoretical relations in respect to where her critical strength is best engaged. He’s drawn to what he sees as ““Haraway’s profound conceptualization of “companion species.”” Haraway challenges the established role and hierarchical control by us humans over animals, plants, objects, and humans. [16] In her publication The Companion Manifesto: Dogs, People, And Significant Otherness, Haraway says, “I believe that all ethical relating, within or between species, is knit from the silk-strong thread of ongoing alertness to otherness-in-relation.” [17]

Haraway’s text in The Companion Manifesto conveys a shocking sense of freedom as if written by someone who longer gives a damn about her academic reputation. Perhaps, what I mean here is that the thinking reaches further than academia and builds alliances with others who may not have read her other works. In the chapter A Category of One’s own, Haraway says, “Anyone who has done historical research knows that the undocumented often have more to say about how the world is put together than do the well pedigreed.” [18] As with her concept for Situated knowledges her intention is to connect beyond officially accepted canons and norms, and established hegemonies. In his chapter HYBRIDITIES Kroker says “Haraway’s writings reveal the apocalypse that is possibly the end condition of hundreds of years of (Western) scientific experimentalism.” [19] This does not mean the West is doomed. However, Haraway has always been on the side of otherness, whether for humans or nonhuman entities. In her eyes our futures or the world as it actually is may not necessarily be as reliant on technology as we like to think.

“Perhaps most importantly, we must recognise that ethics requires us to risk ourselves precisely at moments of unknowingness, when what forms us diverges from what lies before us, when our willingness to become undone in relation to others constitutes our chance of becoming human.” [20] Judith Butler.

Of this quote from Butler’s Giving an Account of Oneself, 2005 [21], which opens the second chapter in Body Drift, Kroker says, “Could there be any text more appropriate to both understanding and perhaps, if the winds of fate are favorable, transforming contemporary politics than Judith Butler’s eloquent study of moral philosophy..?” [21] In Giving an Account of Oneself, Butler presents us with an outline for a different type of ethical practice and proposes that, before you even ask what ought I to do? Ask yourself the question who is this ‘I’? Butler, proposes that it is “a matter of necessity” that every person should “become a social theorist.” [22] Indeed, in the City Lights interview with Peter Maravelis, Kroker says Butler is speaking in terms of people breaking their silence, such as “the repetition chorus of OCCUPY during the Wall Street insurrection”. [23] And then he says, “In many ways, all of Butler’s thought is “standing as witness.” [24] Butler stands witness to what we now know in the 21st century as a violent regime of heterosexual masculinity spreading its domination over history, technology and life itself.

Butler, Hayles and Haraway are major players in feminist and queer academia and media art culture. They have all been active in breaking away from the traditional behaviours that have kept us caught within loops in various ways. Their fluid and progressive approaches to feminism are not only of value to women alone but it can also help others think beyond restrictive behaviours. Kroker’s book manages to reflect the fluidity of networked and contemporary aspects of body drift well, especially from a critically aware, posthumanist perspective. However, no matter how you slice it, it’s about personal and collective freedoms, how we can somehow reclaim our states of being, and how we can own our subjectivities and our psyches in whatever forms these may take. As artists, as humans and or as posthumans – we need Butler, Hayles and Haraway to guide us through this ever-changing, twisting, everyday, posthuman terrain.

Featured image: A is for Art, B is for Bullshit: A history of conceptual art for badasses, book by Guido Segni 2015

“Outside of the Internet there’s no glory” Miltos Manetas”

Guido Segni, is an Italian artist whose activity began in the fields of hacktivism and Net Art in the 90s. As part of his practice he questions the nature of identity that resides on the Web (acting under many fake identities, like Dedalus, Clemente Pestelli, Guy McMusker, Angela Merelli, Anna Adamolo, Guy The Bore, Umberto Stanca,Silvie Inb, Fosco Loiti Celant, Guru Miri Goro, Leslie Bleus, Luther Blissett) and the value of digital activity with projects like 15 Minutes, anonymous, and The middle finger response.

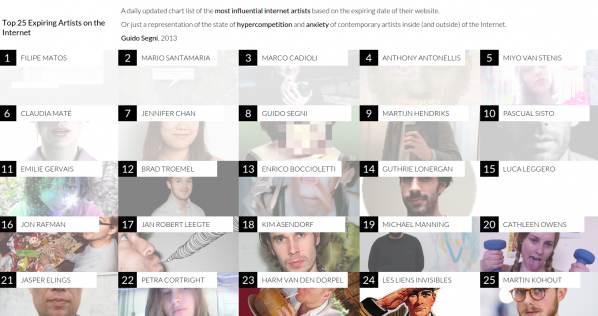

The Internet and lists are two things that have always been together, especially now many of us use social networking platorms such as Twitter and Facebook. We can’t track how and when the first “Top 25/10/5” appeared on the Web, but it’s for sure one of the most frequent ways to gain a lot of attention from Internet users, and it can make you feel as if you’re trapped in a never ending, online fast-food loop. However, when I found out that Guido Segni had created his own version of a top 25 list I was naturally intrigued, so I decided to ask him what it was all about.

Filippo Lorenzin: How and when did you start working on Top 25 Expiring Artists?

Guido Segni: It all started in 2013 after a discussion with Luca Leggero, an artist friend of mine who was working on a piece about the ephemerality of internet art pieces, and it stimulated in me many thoughts on the subject. In the beginning I just wanted to create a sort of memento mori, a list of all artists’ expiring websites. It was only a few months later I introduced the idea of it as a competition, transforming the work into an ironic top artists ranking list, based on the expiration date of their websites.

FL: Could you tell us how it works and how are artists ranked on the list?

GS: It works as many of the other ranking lists you can find on the web. The difference stands on the criteria. While many lists circulating on the web (Top 10 young artist to follow, Top 5 internet artist, etc) are often based on unintelligible criteria, in TEIA (Top Expiring Internet Artists) the criteria are as clear as useless and absurd: the whole list is in fact ordered by the expiration date of the artist website. The nearer is the website expiration date, the better ranking the artist website will obtain. It’s a democratic but very competitive race where everyone can reach the first position even if just for a day. Top 25 Expiring Artists is automagically updated every day – you can only see the top 25 but actually the project counts more than 50 artists. To be included in this list an artist just needs to make an email submission sending the URL of his/her/its website.

FL: This work has many interesting points to talk about, but I would start with lists-related questions. Does ranking artists on the basis of their aim to be not forgotten mean to highlight a typical behavior of all online users or does it specifically relate to web-based artists?

GS: Actually, the piece is mainly focused on web-based artists. Working with digital based technologies, I’ve always had to face the problem of ephemerality: every year I need to renew the subscription to the hosting service of the many website I own, I periodically have to upgrade the technical environment of my works and often I also need to recode them from scratch in order to keep them all working. That’s why I decided to transform this everyday battle with technology into an ironical and nonsense race for artists, aiming to survive to time.

FL: In the list there are only artists mostly interested in digital issues and I know most of them by person. I have even worked with some of them in previous years and this makes me quite comfortable, like if it was more a sort of reunion with old friends, rather than a competitive race. Is this part of the project or would you like it to be more harsh?

GS: Remember the list is a top 25 Internet artists, so it was natural for me when I started the project to choose the first group of artists mainly involved in digital issues. That said, apart from that memento mori feeling which I’ve discussed before, I was also interested in creating a believable and ironical representation “of the state of hypercompetition and anxiety of contemporary artists inside (and outside) of the Internet.” Probably it’s because I’m a nostalgic of the early days of the Internet – the period of the net utopia – but what I see today is more and more a rising feeling of egotism and selfishness. So what I tried to do is just to stress this contraposition between the brotherhood – what you call the reunion with old friends – and the competition, a perpetual struggle between peers for not being forgot.

FL: This project is ironic. You can say this just by seeing how you mimick aesthetic and text styles of online services like Klout or Google Rank. It seems to me that this is a recurring feature in your works – like in The Middle Finger Response. Is it true?

GS: It maybe depends on the fact that I’m from that particular area in Italy (Tuscany) where you can’t either take yourself too seriously. Or maybe it depends on the fact that irony itself is an important feature you can find over all the formats on the Internet. But I agree with you that willing or not the use of irony is a recurrent and strong component of my works.

FL: I’m interested in how people (me too, yes) sign to online services that promise them to rank their online lives on the base of their influence capacity. It’s like watching a mirror made on quantification premises, built by the same system that push you to post more and more about yourself and your incredibly unique existence. In which way this project is related to this phenomenon?

GS: The main intent of the project is to ridicule lists of any sort. But said that, I think the reason why lists – as a cultural form – are so popular is that they have the power to simplify the representation of complex phenomena of reality. So the various “Top artists to discover”, “Top 10 rock bands” or the “Most influential person in the world” are just examples of a fictious narration which give the apparent comprehension of the real. And this is particulary true in an over-polluted space like the Internet.

FL: In the brief conversation we had previously on Twitter, you said to me that you would like to make other versions of this project. Can you tell me something about this?

GS: I have many ideas about these new versions but unfortunately I’m a very slow man and I still don’t know how and when they will be released.

FL: You worked on the branding of people also with 15 Minutes, anonymous. Could you tell us if and how there is a connection between that work and Top 25 Expiring Artists?

GS: To be honest, at that time I hadn’t in mind these connections. From a certain point of view I think they are very different form each other, but it’s true that they both implicitly move around the concepts of fame and anonymity in opposite directions. While in Top 25 Expiring Artists the expire date is an ironic way to reach a sort of fame – even if only for a day – in the case of 15 Minutes, anonymous I focused on the algorithmic aspect of transforming a very large number of pictures of pop symbols into anonymous and abstract pictures.

FL: Again, the anonymity and the individual are two of the main questions in your research. This happens also with Proof of existence of a cloud worker, and I recall me Middle Finger Response. What do you think?

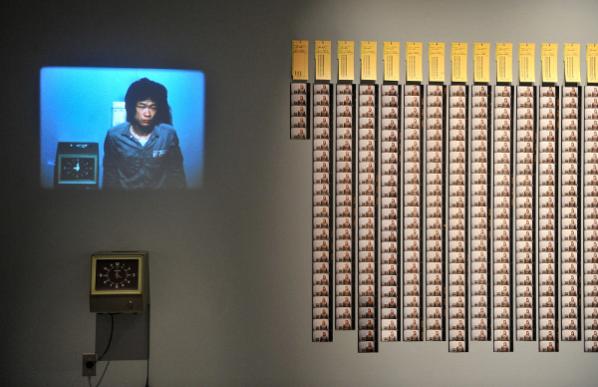

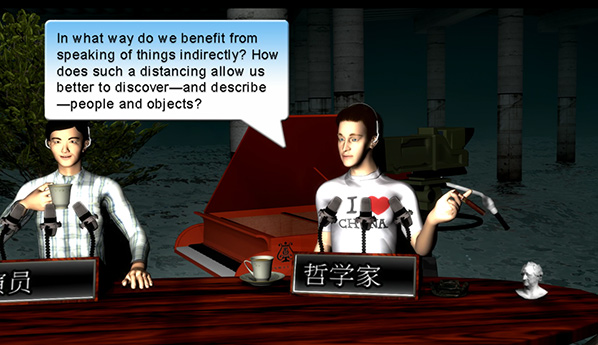

GS: Between 2013 and 2014 I made several experiments with crowdsourcing and, yes, Proofs of existence of a cloud worker and Middle Finger Response have many points in common apart from that they are projects based on Amazon Mechanical Turk platform. Basically they both document and display what crowdsourcing is from the point of view of the workers dispersed through the new digital frontiers of leisure and labour. I think you got the point when you talked about anonymity and individual. As all the efforts of crowdsourcing platforms are to hide and anonymize the crowd, what I tried to do is to give them back a face and a voice. In The Middle Finger Response I focused on the spontaneous pose and gesture captured by the webcam, while in Proofs of existence of a cloud worker I used a more abstract and apparently nonsense approach as I asked them to re-enact a clip found on YouTube which shows a person claiming “Pics or it didn’t happen”.

FL: What will you be doing in the future?

GS: As I’ve already said I’m a very slow guy and I’ve been working on this particular project for almost 2 years. But I think we’re almost there and in a few months I’m going to release it. It’s a project about failures, datacenters, space/time travels and desertification of communications. Stay tuned 😉

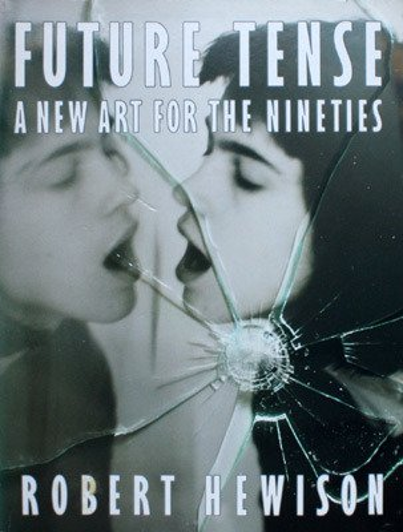

This article revisits Robert Hewison’s book, Future Tense: A New Art For The Nineties, [1] published in 1990. The book focused on contemporary attitudes to art, architecture and design that manifested in what had come to be called the postmodern era. Earlier avant-gardes of collectives and groups such as Dada, Situationism, Fluxus and the Lettrists had incorporated new technologies and challenged the material values embraced by museums and traditional hierarchies in modern art and capitalist society. Hewison set out to discover the ways in which artists of the 80s contributed to a “critical culture” for the 90s. [2]

In the 70s in the UK, art had a role to play in changing society, transforming relations to controlling production and critiquing the role of the establishment. Hewison’s mission was to observe contemporary culture happening in the late 80s in Britain with an emphasis on the future. Even though there had been a massive evolution in culture; within and across the fields of music, art and theory, it was also a new dawn for capitalism as it morphed into what we now know as neoliberalism. By revisiting Hewison’s book I hope to elucidate what the cultural shifts and differences in our art culture then and now are, and invite you the reader to reflect on what they mean to those of us engaging with and practicing across the fields of art, technology and social change today.

The way Hewison deals with postmodernism and its rapport with art and society is complex. He appears to regard much of the established art promoted in the late 80s, such as works by Jeff Koons, as banal marketing schemes, appealing to the interests of a privileged art-buying elite. He is more positive about grass roots communities re-appropriating and remixing art culture for others to claim on their terms. Michael Archer in his review of Present Tense in Marxism Today (1990) observed that not only was Hewison critical of modernism but also of postmodernism, which did little more than signal modernism’s ending. [3]

![[4] (Hewison 1990)](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/hewison1.jpg)

Lyotard argues that the grand narratives of 20th century modernism did not produce the benefits expected; rather, they have led to overt or covert systems of oppression. From this perspective the French Revolution and classic Marxism are seen only as forms of overarching and oppressive, ideology. Frederic Jameson offers another perspective on the ideas and social contexts around postmodernism. In his book Postmodernism: Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Jameson says “It is safest to grasp the concept of postmodernism as an attempt to think the present historically in an age that has forgotten to think historically in the first place.” [5]

Future Tense’s cover image on the front of the book still feels contemporary. It shows a young woman about to kiss her mirror image while in front of a cracked glass, window. It alludes to a sense of culture – felt then as we still feel it now: as a disjointed picture of the world where modes of thinking and representation show us fragmentations, discontinuities and inter-textuality, and ‘bits-as-bits’ rather than unified objects. If the image were created now with a smashed up computer or mobile phone screen or an interface, its message would not be so different. We tend to beam our faces at our computer screens and then the screens beam right back at us, reflecting at us like data-mirrors, showing back not only a distorted image of ourselves but also a distorted multiverse.

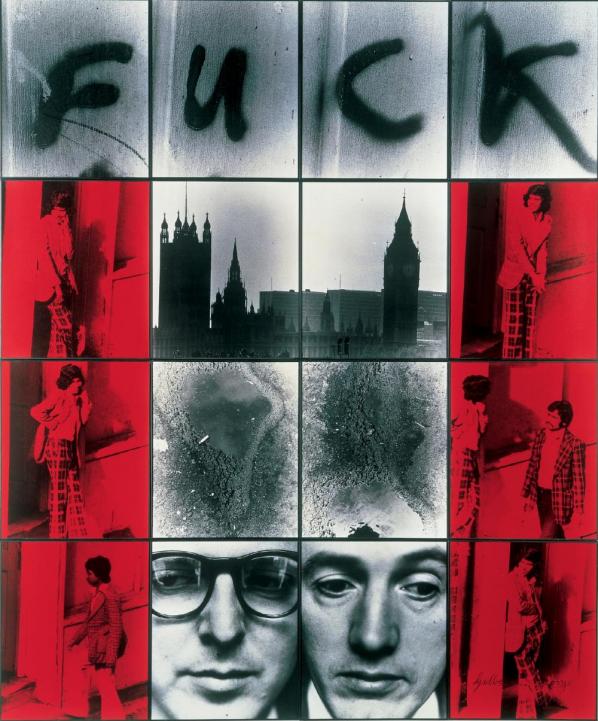

There has always been an irony at play with Gilbert & George. They usually expound a kind of punk aesthetic as an edgy chic; your lowest, basic, bigoted and unreconstructed inner ape giggles at their poo jokes. Yet while they subvert the idea of the ‘high’ of ‘high art’ by breaking life-style taboos they never bite the ‘high’ hand that feeds them. They know that shock is a dead cert currency just as the gutter press understands that sex and outrage sells, and that ethics and criticality get in the way of free market play. They sit well with the younger establishment in the arts, especially Damien Hirst and his peer YBAs, and similar Saatchi and Saatchi marketing investments.

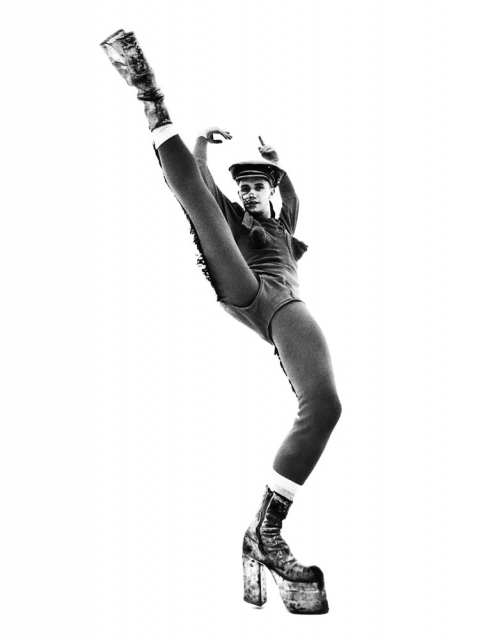

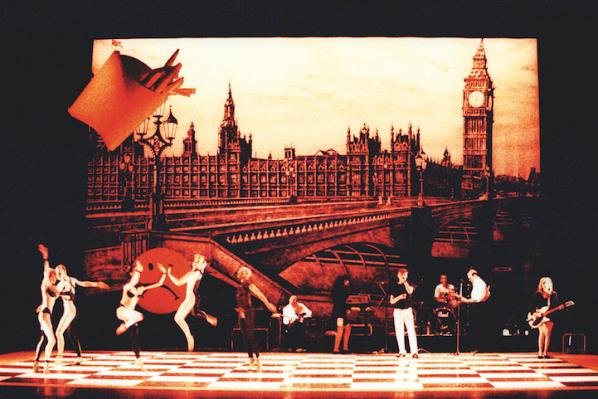

Hewison discusses Saatchi and Saatchi’s gallery space, and how the work presented in the space achieves an apparent purity, which detaches it from life, and that it has that autonomy within its own sphere which much twentieth-century art has sought to achieve. But in doing so it has separated itself from that other impulse, to use art as a means of revisualising, and so changing the world. [6] (Hewison 1990) This is still a big problem with art across the board even now. Most art agencies, orgs and galleries, are still separated from people’s everyday life experience. In contrast Michael Clark and his dance company was and still is a breath of fresh air. Even though he was classically trained, Clark tore “up the conventions of ballet, mixing sound and image in a rapid collage of creation, quotation and reference that plunders popular culture with calculated offence.” [7]

Cross cultural and interdisciplinary collaborations have been another marker of radical transformation in the postmodern era. Clark’s collaboration with the punk band The Fall in 1988 is a case in point where two different fields meet and create a brilliant outcome.

“I’ve always had a very strong relationship to music, to punk and pop – David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Sex Pistols, especially The Fall. The Fall’s song “New Puritan” was kind of a clarion call to me, not just because its rhythm is so ramshackle. When you listen to it, you wonder, “How the fuck do the musicians stay together?” Apart from that, the song encouraged me to say, “Wow, I’ll do it just like Mark E. Smith!” You know, “New Puritan” was against the idea of a big company, and I didn’t want to be employed by anyone. I didn’t want to sign a contract. I wanted to make my own work. I wanted independence, my own company. Mark E. Smith was definitely an example for that.” [8] (Clark 2014)

Many women artists during the 80s and 90s were using their bodies and identity as part of their art practice. Perhaps, one of the most treasured in the UK and greatly missed is Helen Chadwick who died on the 15th March 1996.

“Long before the current artistic obsession with the human body as a means for exploring identity, Chadwick had declared that “my apparatus is a body x [multiplied by] sensory systems with which to correlate experience”” [9] (Buck 1996)

Yet, her work resonates beyond her time period and still lives on through individuals inspired by her imaginative works to this day. Hewison dedicates five pages to Chadwick, and when discussing her installation Of Mutability, he says her work possessed a particular autonomy and, “Chadwick has found that the piece is most quickly appreciated by bisexuals who apprehend more easily the polymorphous nature desire.” [10] (Hewison 1990)

Hewison refers to the media baron Cardinal Borgia Gint in Derek Jarman’s film Jubilee, the baron in the film says “You wanna know my story, babe, it’s easy. This is the generation of who forgot how to lead their lives. They were so busy watching my endless movie. It’s power, Babe. Power. I don’t create it, I own it. I sucked and sucked and sucked. The Media became their only reality, and I owned the world of flickering shadows – BBC, TUC, ATV, ABC, ITV, CIA, CBA, NFT, MGM, C of E. You name it – I bought them all, and rearranged the alphabet.” [11]