The Future Machine, part of Furtherfield’s Citizen Sci-Fi programme, has been built with local groups as a witness to people and places, changing over time. It gathers evidence and stories of these turbulent times, as the Earth changes, and we journey to an uncertain future.

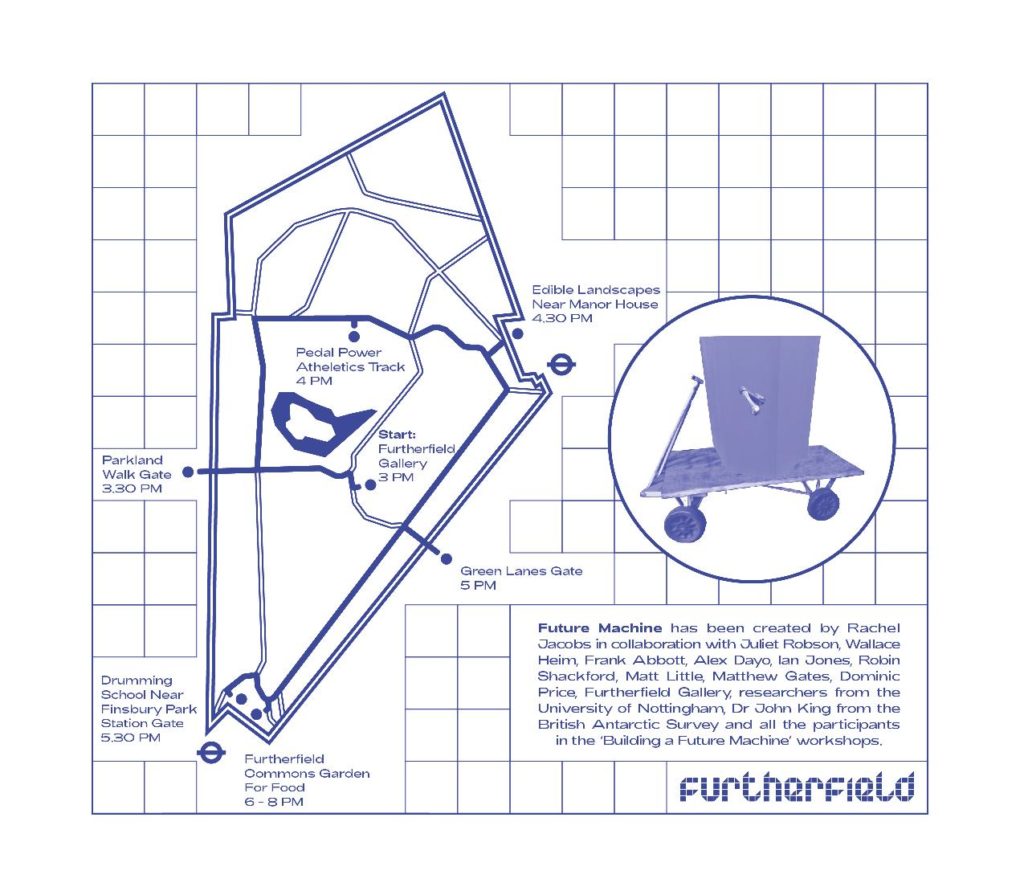

You are invited to join the Future Machine on it’s first procession around Finsbury Park on Sat 12 Oct. We begin at Furtherfield Gallery at 3.00pm. Then the Future Machine will be welcomed at various stops on the way by local groups who promise to care for the future, it ends its journey at 6pm with a party to welcome the Autumn in at Furtherfield Commons Garden.

Please join the procession at Furtherfield Gallery at 3pm, or at any of the stops and dress up in your best or wildest Autumn clothes.

Future Machine Procession Stops:

Future Machine has been created by Rachel Jacobs in collaboration with Juliet Robson, Wallace Heim, Frank Abbott, Alex Dayo, Ian Jones, Robin Shackford, Matt Little, Matthew Gates, Dominic Price, Furtherfield Gallery, researchers from the University of Nottingham, Dr John King from the British Antarctic Survey and all the participants in the ‘Building a Future Machine’ workshops.

After touring to other places across England, the Future Machine will return to Finsbury Park in October in 2020 and 2021, as the future comes.

Featured image: credit to Rachel Jacobs

Future Fictions for Finsbury Park is part of our Citizen Sci-Fi initiative. It brings together sci-fi writers in residence with local residents and set of scientific experts to explore written visions of a Finsbury Park of the future.

For our 2019/2020 year of FF4FP we worked with sci-fi writers Mud Howard and Stephen Oram to create two new short stories about the park, based on deep research conducted with community members and experts. Via a set of workshops organised by Producer, Ruth Fenton, participants were invited to explore both near and far future ideas based on the current knowledge we have of climate change and technological developments, to imagine how we might like to see Finsbury Park evolve.

At our Future Fair on 10th August 2019, both Mud and Stephen gave live readings of their stories, which will be published on the Furtherfield website this Autumn.

Mud Howard (they/them)

A gender non-conforming poet, performer and activist from the states. mud creates work that explores the intimacy and isolation between queer and trans bodies. mud is a Pushcart Prize nominee. they are currently working on their first full-length novel: a queer and trans memoir full of lies and magic. they were the first annual youth writing fellow for Transfaith in the summer of 2017. their poem “clearing” was selected by Eduardo C. Corral for Sundress Publication’s the Best of the Net 2017. mud is a graduate of the low-res MFA Poetry Program at the IPRC in Portland, OR and holds a Masters in Creative Writing from the University of Westminster. you can find their work in THEM, The Lifted Brow, Foglifter, and Cleaver Magazine. they spend a lot of time scheming both how to survive and not perpetuate toxic masculinity. they love to lip sync, show up to the dance party early and paint their mustache turquoise and gold.

Stephen Oram

Who writes thought provoking stories that mix science fiction with social comment, mainly in a recognisable near-future. He is one of the writers for SciFutures and, as 2016 Author in Residence at Virtual Futures – described by the Guardian as “the Glastonbury of cyberculture” – he was one of the masterminds behind the new Near-Future Fiction series and continues to be a lead curator. Oram is a member of the Clockhouse London Writers and a member of the Alliance of Independent Authors. He has two published novels: Fluence and Quantum Confessions, and a collection of sci-fi shorts, Eating Robots and Other Stories. As the Author in Residence for Virtual Futures Salons he wrote stories on the new and exciting worlds of neurostimulation, bionic prosthetics and bio-art. These Salons bring together artists, philosophers, cultural theorists, technologists and fiction writers to consider the future of humanity and technology. Recently, his focus has been on collaborating with experts to understand the work that’s going on in neuroscience, artificial intelligence and deep machine learning. From this Oram writes short pieces of near-future science fiction as thought experiments and use them as a starting point for discussion between himself, scientists and the public. Oram is always interested in creating and contributing to debate about potential futures.

The Future Experts comprised of local residents of Finsbury Park, who brought invaluable knowledge of the area, and professional experts from a variety of scientific and design based backgrounds, who brought expertise in future thinking in many areas including health, transport, technology and architecture.

Ling Tan

Ling Tan is a designer, maker and coder interested in how people interact with the built environment and wearable technology. Trained as an architect, she enjoys building physical machines and prototypes ranging from urban scale to wearable scale to explore different modes of interaction between people and their surrounding spaces. Her work falls somewhere within the genre of the built environment, wearable technology, Internet of Things(IoT) and citizen participation. It involves working with various communities in different cities and uses wearable technology as tools to express their relationship with the city, touching on demographic, race, gender and the subjective experience of the city through people.

Paul Dobraszczyk

I am a researcher and writer based in Manchester, UK, and a teaching fellow at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. I’m currently researching anarchism and architecture as well as completing a co-edited book Manchester: Something Rich and Strange (Manchester University Press, forthcoming in 2020). I’m the author of Future Cities: Architecture and the imagination (Reaktion, 2019); The Dead City: Urban Ruins and the Spectacle of Decay (IB Tauris, 2017); London’s Sewers (Shire, 2014); Iron, Ornament and Architecture in Victorian Britain (Ashgate, 2014); and Into the Belly of the Beast: Exploring London’s Victorian Sewers (Spire, 2009). I also co-edited Global Undergrounds: Exploring Cities Within (Reaktion, 2016); and Function & Fantasy: Iron Architecture in Long Nineteenth Century (Routledge, 2016). I am also a visual artist and photographer and built the website http://www.stonesofmanchester.com. I blog at https://ragpickinghistory.co.uk/.

Dr Rasmus Birk

I am a social scientist, currently working as a Visiting Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Global Health & Social Medicine, King’s College London. My research here explores the relationship between city life and mental health, specifically how living in the city leads, for some people, to the development of mental health problems. I am currently researching the experiences of young people with common mental health problems (such as depression, anxiety, or stress) in South East London.

Dr Kate Pangbourne

University Academic Fellow at the Institute for Transport Studies (University of Leeds). She has an MA (Hons) in Philosophy with English Literature, an MSc in Sustainable Rural Development and a PhD in Geography – Environmental (Transport Governance). Her research is oriented towards shifting our transport system and individual choices towards greater environmental sustainability, social inclusion and meaningful prosperity. She is particularly interested in the implications of rapid technological change in the transport sector. Current work includes improving the persuasiveness of travel behaviour messages (ADAPT, funded by EPSRC), enhancing the rail passenger experience (SMaRTE, funded by the EU through Shift2Rail) and the societal challenges posed by self-driving vehicles and new concepts such as Mobility as a Service. Proof of humanity: has children, grows vegetables, sews and knits, sings, plays the piano, and used to play jazz sax (badly). Weird info: is a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Cordwainers and of the City of London (but lives in Scotland).

https://environment.leeds.ac.uk/transport/staff/971/dr-kate-pangbourne

Dr Christine Aicardi

Originally trained in applied mathematics, computer sciences and project management, with a MEng from the Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées in France. She worked for many years in the Information and Communication Technologies industry, where she held a variety of positions (analyst/programmer, junior consultant, sales engineer, major account manager). She returned to higher education and came to Science and Technology Studies in 2003 as a mature student. After her MSc at the London Centre for the History of Science, Medicine and Technology, she was funded by the ESRC through her doctoral studies, and in 2010, she completed her PhD in Science and Technology Studies at UCL, in the area of Artificial Life. She is currently a Senior Research Fellow for the Human Brain Project Foresight Laboratory. The Lab aims to evaluate the potential social and ethical implications of the knowledge and technologies produced by the Human Brain Project for European citizens, society, industry, and economy. Prior to this, she was Wellcome Library Research Fellow, working on a sociological history project focused on the later career of Francis Crick, British molecular biologist and geneticist, who in the 1970s moved to Southern California and became a neuroscientist.

Featured image: Rusty Russ Twisted Tree ReTwisted via photopin (license)

This 3-year programme supports our Platforming Finsbury Park initiative. Between 2019-2021 we will produce exhibitions and events that combine citizen science and citizen journalism by crowdsourcing the imagination of local park users and community groups to create new visions and models of stewardship for public, urban green space. By connecting these with international communities of artists, techies and thinkers we are co-curating labs, workshops, exhibitions and Summer Fairs as a way to grow a new breed of shared culture.

#CitSciFi – crowdsourcing creative and technological visions of our communities and public spaces, together.

The Time Portals exhibition, held at Furtherfield Gallery (and across our online spaces), celebrates the 150th anniversary of the creation of Finsbury Park. As one of London’s first ‘People’s Parks’, designed to give everyone and anyone a space for free movement and thought, we regard it as the perfect location from which to create a mass investigation of radical pasts and futures, circling back to the start as we move forwards.

Each artwork in the exhibition therefore invites audience participation – either in its creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more imaginings of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

For this Olympic year we will consider the health and wellbeing of humans and machines.

For this year of predicted peak heat rises we will consider how machines can work with nature.

Structures. Something has been built, grown, stretched. Maybe skin, maybe a web, maybe a protective barrier – it is a plastic protein emitted by an organism in order to increase its survival opportunities, it is a food matrix for its offspring which thrive on glossy resin. You can travel across it and it can easily be mapped, although not by humans.

We can’t say anything about it – we can speculate everything about it. It is something possible or as the author says another reality. The real is replaced by the potential. This is one of a series of works by St. Petersburg-based artist Elena Romenkova. The works are glitches, abstract distortions, alien expressions of what for her is a subconscious realm.

A portal. You are entering the rainbow world contained within two concentric eggs within the grey world. This is light, reflections, haze, indescription. It looks inviting. The colour spectrum is odd, the whites creep up on everything else, the shape of everything is strange. Basic synaesthetic rules are inapplicable at the rainbow/grey world junction.

There is nothing that this image, by French artist Francoise Apter (Ellectra Radikal), has in common with Romenkova’s. They are united only by their adherence to strangeness, a technically created vista that looks like nothing we know. A world not of local cultures, but of computational production. Here anyone can know anything, it doesn’t matter where you’re from.

What is culture when locality is secondary to epistemology? What is knowledge when the portable device takes precedent over your situated environment? Worlds are built around us, sophisticated electrical spaces, they travel where we travel, and only after do we factor in the idiosyncracies of specific geography. If the banal experience is one of nomadic alienation, of search methods based on no place, what does the role of culture and art become? Everyday life is a subject for hypothetical language. The digital commons is a species of posthuman that communicates via speculative misunderstanding.

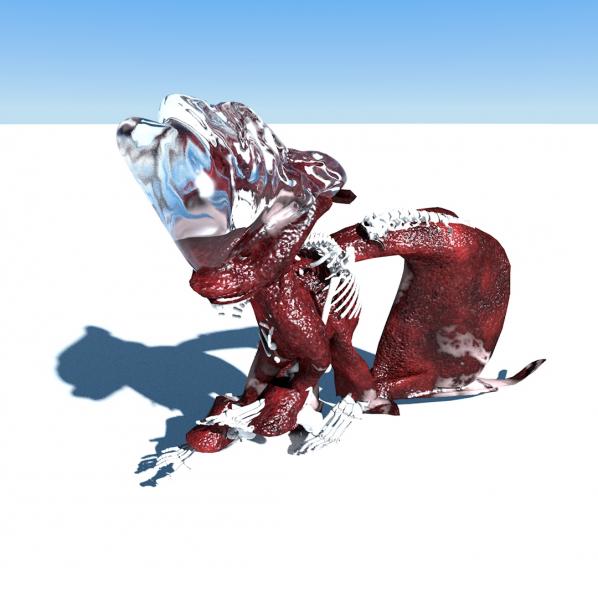

Korean artist Minhyun Cho (mentalcrusher) shows us what the dinosaurs really looked like. When you put the meat and scales back on. He shows us what an ice building being looks like in the shadow of terminal cartoon winter. How rubber can be used to erect sculptures and bones can be taken out of museums and put to good use in civic architecture. No one is around to see this, but still the idea sets a precedent. Crown each ghost with ice mountain prisms.

With visual language, very quickly we get to a stranger and more indeterminate range of science fiction possibilities than narrative tends to map out for us. How much imagination is possible, and how much does our internal experience match anything presented around us. If our environments advance exponentially quicker than any generational or traditional mythology, what sort of language can we have for expression? The maker’s invention precedes the reception of form. Innovation is a matter of banal activity, communicating an experience of the real which is never the same.

And now an eyeball. Triangles. A vessel. To Cho’s blinding world of light, Spanish artist Leticia Sampedro responds with a featureless darkness. All absurdities once on display, now they recede into nothing. It might be a mandala, perhaps an artifact from the ancient future, a portable panopticon that fits conveniently on your desktop. Your feelings are here, your peculiar distances, everything’s reflecting off the glass, the metal, the camera. You are the mirrored fragments of an invention we’ve lost the blueprints to. Foresight the womb of a disembodied politics of community.

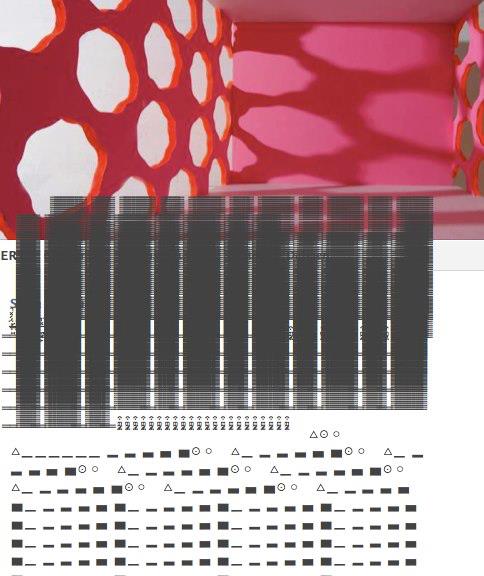

Community held together by structures. In German artist Silke Kuhar‘s (ZIL) work, we enter into one of these structures. Inside we find hallways, a nice selection of windows and all kinds of data – scripted, graphed, symbolized. This is the plan for the future. I hope you can read what it says. Her work meshes spaces with collapsing foreign constructs – if we can just read the language we’ll know what to do. But no one reads it, and no one wrote it. This is a building without inhabitants – architecture without people. Democratic ballots are automatically filled out by a predetermined algorithm. Your agency is a speculative proposition for popular media – people collaborate with you, but they can’t be sure where you are, when you wrote, and if you really exist as such.

No people. This is a unifying principle. Cold, silver, streams. Machines in the sky. Silicon waterfalls, diagonal. Civilization distilled into physical patterns, an obtuse object photographed in another dimension. What is the word for reality again. What is the word for scientific investigation? A Venezuelan based in Paris, Maggy Almao’s abstract glitch world is silent – it’s a gradient, it’s some illusion of partial perspective.

What is the language to talk about the world? If we turn to artists’ visualizations, what does that tell us about languages we speak, and ones we read? What does the graphing of incomprehensible mechanisms tell us in turn about art and its history? The machine’s narratives tend to drown out any functional reality. Genre storytelling tropes become repurposed as collective cultural ideas. Conceptual works are followed by pragmatic speculation, medium-centric analysis replaced by experimental failures. You can never get a fictional experiment to work.

Science has indelibly entered the art field, for each of its medial innovations it requires further attention in terms of its technical makeup. Half the work is figuring out what the canvas even is, we are building canvases, none of them look alike, and their stories read like data manuals. An aesthetics of unknown information.

This is the homeland. The homeland is mobile and has many purple bubbles. It’s an airship from the blob version of the Final Fantasy series. It has satellite TV to keep in touch with the world. It has some tall buildings so you know it’s civilized. It is part of Giselle Zatonyl, an Argentine-born Brooklyn-based artist’s opus which deals comprehensively with science fiction ideas and their implications.

The ship travels, where the culture originates is more and more unknown. It is technically divided, access is the key, we can worry about language and culture later. We are still embodied, still located somewhere, but all this has become subject to the trampling of scientific mythologies, where their utilities might go, and where their toys are most needed. Crisis is a genre now, about as popular as time travel. You are now free to dream up whatever future society you wish, and subjugate whatever cyborg proletariat your heart desires. In the realm of speculation, anything is possible, and nothing is fully acceptable.

The themes of internet art production give us some language, some set of visions that tell certain stories – works found throughout the internet, posted in communities, shared online – sometimes part of gallery exhibitions or products, sometimes not. You get a profile, some social media pages, build a website, you begin making, sharing and remixing images. Folk art is a subsidiary of new media art – social sculpture meets internet content management systems. A language for political engagement based on the creative activity of speculation. Scientific dreams for a technological commons.

Dreams where sight is physicalized into complex data graphs. Where Sampedro’s portable gelatin panopticon is cloned into a regularized matrix. Inspired vision is just one aspect of algorithmic predictability. In Taiwanese artist Lidia Pluchinotta‘s visual work, the cloned image is central. Mechanical reproduction, skulls, spirals, symbols, the internet has it all. Civic participation has never been so mathematical, observation never so multiple.

Inside the city, architecture is actually a colour-coded map that helps you find the store you’re looking for. The map is the territory except there’s no info on how to read it. We are here, we are home, but the walls of the buildings were designed by some specialist that we haven’t met yet. Stairs, depths, the complex and layered constructions in Canadian artist Carrie Gates‘ work aren’t quite one of Zatonyl’s buildings. More fragmented, more saturated, more chaotic. It’s speculated that people could live here, although we don’t see them anywhere. Not yet anyway.

The maelstrom of technological progress presents us with the need to adapt our participation and rhetoric accordingly. Science fiction is a folk language for common experience within a technoscientifically oriented world. These images are imaginative products of social and participatory artist communities who, when marrying the personal and contextual, create speculative objects of general strangeness. Their description is nothing less that one of alien entities – alien entities that are everywhere. Earth is the most sophisticated foreign planet we’ve yet to invent, we just need to discover how to populate it.

Die GstettenSaga: The Rise of Echsenfriedl review. SPOILER WARNING!

Johannes Grenzfurthner’s Post-Apocalyptic DIY Epic on Makers, Hacktivism and Media Culture.

“A mad post-collapse satire of information culture and tech fetishism, in a weird sort of melding of Stalker, Network, and The Bed-Sitting Room.” (Richard Kadrey)

Die GstettenSaga: The Rise of Echsenfriedl is an Austrian hackploitation art house film by Johannes Grenzfurthner, mastermind of the international art-technology-philosophy group monochrom, co-produced by the media collective Traum & Wahnsinn. Reimagining the makerspace as grindhouse, the story is set in the post-apocalyptic aftermath of the “Google Wars” – an armed global conflict between the last two remaining superpowers China and Google – which has turned what remained of the Alps into a Gstetten.

In Austrian German, “Gstetten” translates to wasteland, outback or ‘fourth world’ (Manuel Castells) and is a popular name for provincial towns – and sometimes just the less sophisticated parts of them. The area’s biggest semi-urban sprawl is Mega City Schwechat, the former home of Vienna International Airport, a refinery and a beer brewery. It is governed by the evil media mogul Thurnher von Pjölk (Martin Auer), a pretender who claims to be the inventor of key publishing technologies such as letterpress printing and rules the area with his tabloid newspaper. But the hegemony of his yellow press empire is contested by – spoiler alert! – makers, hackers and nerds, who are more leaning towards electronic media such as the recently rediscovered television. In order to get rid off this bothersome opposition, Pjölk devises an evil plan for wiping out Schwechat’s insubordinate creative class.

In an insidious political move, he pretends to reach out for the technophile faction by commissioning two of his reporters, the bootlicking opportunist Fratt Aigner (Lukas Tagwerker) and the brainy geek girl Alalia Grundschober (Sophia Grabner), to conduct an exclusive TV interview with the ultimate Gstetterati icon, the legendary innovator Echsenfriedl (“Lizard Freddy”) – on the basis of precarious employment conditions. The title character, who turns out to be an basilisk, embodies a mix of Steve Jobs, Richard Stallman and Julian Assange and lives in the depths of Niederpröll in his hideout much like Subcomandante Marcos – partly in order to protect the world from his killing gaze, which would, audio-visually transmitted, turn the whole of his fan base immediately to stone.

Grenzfurthner’s sci-fi-horror adaption of the Divine Comedy takes us on a retro-futuristic post-cyberpunk adventure in the tradition of cinema grotesque back to the dark days which preceded the Internet. The journey of our heroes – distinctively resembling Tarkovsky’s ‘stalkers’ – is a quest for extinct media technologies but their search for Echsenfriedl eventually leads the two protagonists to a deepened understanding of who they really are: the media industry’s precarious workforce under spectacular capitalism. While Fratt’s dirt track to enlightenment is paved with stumbling blocks, his brainy Beatrice advances with the determination of a Harawayian cyborg who makes use of her superior technical skills to save them from the zombified folk populating the Gstetten: uncanny creatures from the Kafkaesque bestiarium of Austria’s undead bureaucracy and its hanger-ons like armed-to-the-teeth Postal Service subcontractors (brilliant: monochrom’s Evelyn Fürlinger, also Grenzfurthner’s ex-wife) or the once powerful Farmers Association led by Jeff Ricketts (Firefly, Buffy the Vampire Slayer), who are worshipping antique pre-war EU funding applications as their sacred scriptures. Our friends receive the final hints for their search from the Sphinx Philine-Codec Comtesse de Cybersdorf (Eva-Christina Binder), a fantasy femme fatale who is torn between Plöjlk and Echsenfriedl, and the bearded drag queen Heinz Rand of Raiká (David Dempsey), an eccentric agricultural cooperative banker and possible descendant of Conchita Wurst.

The Gstettensaga’s fascinating cinematic pastiche is more than just a firework of rhizomatic intertextuality, a symptom of the depthlessness of postmodern aesthetics or excessive enthusiasm for experimentation in the field of form. In their infamous 1972 book Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari have identified the technique of bricolage as the characteristic mode of production under “schizophrenic” capitalism, a facet triumphantly magnified by the filmmakers. If every discourse is bricoleur, like Jacques Derrida suggested, suddenly ‘context’ can become the artist’s material or even a form of art in its own right:

“The more artists are consigned to an existence within a patchwork of niches, the more dependent they become on information resources, communication and networking. In this respect, aesthetic artefacts must take a stance toward a plethora or markedly heterogeneous contexts that sediment in one way or another: the conditions and circumstances surrounding their production, their various social fields from which (and for or against which) they speak: real or imagined audiences toward (or against) whose values a work, an approach or a position is targeted. This play with the factors affecting it and among which it must mediate has become an essential trait on an art form that might best be described as ‘Contextualism’.” [1]

What I found especially intriguing about the Gstettensaga is how the filmmakers responded to the various challenges of the feature film format by contextualising the whole production process, distribution, language adaptions (subtitles are an integral part of the story), soundtrack and even the viewing experience.

The film was initially commissioned by Austrian public broadcasting station ORF III as part of the series Artist-in-Residence for a budget of only €5000, set to be produced within a six months period. In response, monochrom used an embedded prank to raise money. The movie contains a text insert similar to watermarks used in festival viewing copies, which asks the viewer to report the film as copyright infringement by calling a premium-rate phone number (1.09 EUR/minute) and enabled Grenzfurthner to co-finance the film with proceeds from this new strategy he has named ‘crowdratting’. [2]

The Contextualist script – including outlines of scenes for improvisation – was written by Grenzfurthner and Roland Gratzer in just a couple of days in November 2013 in a Viennese restaurant. They also incorporated ideas that came up during their weekly meeting with the entire production crew, whereas some of the backstory was first created for monochrom’s pen-and-paper role-playing theatre performance Campaign. Principal photography – the camera work of Thomas Weilguny deserves the highest praise – commenced on December 2, 2013 and ended January 19, 2014, which left nearly 5 weeks for post-production and editing. Due to the fast production process and the financial limitations, no film score was composed for the Gstettensaga – instead, Grenzfurthner used an assortment of 8bit, synth pop and electronica tracks especially for their specific retro quality because “they may sound old-school to us, but not in the world of the Gstettensaga, where all retro electronic music is still impossible and futuristic.” [3]

The retro-futuristic world of Echsenfriedl is coming to a film festival, hacker con or Pirate Bay near you.

http://www.monochrom.at/gstettensaga/

Tamtam (Seara de proiectie la TT) / May 7, 2014 (Timisoara, Romania)

KOMM.ST Festival / May 11, 2014 (Anger, Austria)

Supermarkt (Dismalware) / June 7, 2014 (Berlin, Germany)

Fusion Festival / June 25-29, 2014 (Lärz Airfield, Mecklenburg, Germany)

Roswell International Sci Fi Film Festival / June 26-29, 2014 (Roswell, NM, USA)

iRRland movie night / June 30, 2014 (Munich, Germany)

qujochö Film Summer / July 3, 2014 (Linz, Austria)

HOPE X / July 18-20, 2014 (New York, New York, USA)

Fright Night Film Fest / August 1-3, 2014 (Louisville, KY, USA)

Gen Con Indy Film Festival 2014 / August 14-17, 2014 (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA)

San Francisco Global Movie Fest / August 15-17, 2014 (San Jose, CA, USA)

Rostfest / August 21-24, 2014 (Eisenerz, Austria)

Noisebridge / August 29, 2014 (San Francisco, USA)

/slash Filmfestival / September 18-28, 2014 (Vienna, Austria)

Simultan Fest / October 6-11, 2014 (Timisoara, Romania)

Phuture Fest / October 11, 2014 (Denver, Colorado, USA)

prol.kino / October 14, 2014 (Graz, Austria)

Featured image: Jane and Louise Wilson – ‘False Positive, False Negative’ (2012 Screen print on mirrored acrylic)

The Negligent Eye the Bluecoat Liverpool Sat, 08 Mar 2014 – Sun, 15 Jun 2014 http://www.thebluecoat.org.uk/events/view/exhibitions/1971

Featuring artists: Cory Arcangel, Christiane Baumgartner, Thomas Bewick, Jyll Bradley, Maurice Carlin, Helen Chadwick, Susan Collins, Conroy/Sanderson, Nicky Coutts, Elizabeth Gossling, Beatrice Haines, Juneau Projects, Laura Maloney, Bob Matthews, London Fieldworks (with the participation of Gustav Metzger), Marilène Oliver, Flora Parrott, South Atlantic Souvenirs, Imogen Stidworthy, Jo Stockham, Wolfgang Tillmans, Alessa Tinne, Michael Wegerer, Rachel Whiteread, Jane and Louise Wilson.

The Negligent Eye revolves around the way a digitally-native generation of artists – particularly printmakers – are questioning their relation to the digital, using the notion of ‘scanning’ as a kind of mid-state of the creative process of the human-digital hybrid. The show is co-curated curated by the Bluecoat’s Sara-Jayne Parsons and head of printmaking at the RCA, Jo Stockham, and features several works by her graduates, and other artists from around the RCA, such as Bob Matthews and Christiane Baumgartner. “The relationship between the material and virtual worlds is a question, a set of contradictions we are all inside and how technical images exert their influence on our everyday experience is of ever increasing importance.” Jo Stockham.

In her article Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead? Hito Steyerl asks what happened to the internet, after it died – that is, in an era of the “post-internet” after it stopped becoming a possibility, even in the midst, because of, and symptomized by, its permeation of everything. Steyerl is a major force in understanding our relationship to digital images, and her use of ‘death’ occurred to me often during viewings of this show and surrounding events, particularly as it could be applied to the post-digital.

So in a sense, I experienced the show as an autopsy of the digital image. From the tragic, simian face looking out from the first ever digital image, taken by Russell Kirsch of his son in 1950, exhibited at two points in the exhibition like an insistent memory. To Marilène Oliver’s figures from her 2003 Family Portrait series where bodies have been evoked as series of horizontal cross-section prints layered on acetate, so that they appear as though stored, but only partially in this world; the exhibition continually references, exemplifies and unpacks the death of its medium.

The post-digital is a paradoxical term – at once assuming the reliance of all contemporary culture in digitality, but also looking past it; affirming the death of a form, while embodying its afterlife. This is what Elizabeth Gossling’s images of a dead comedian says to me, when it is scanned from a computer screen and printed back on to archival paper, with his image waving from behind an ether of static, living in the solid pulp. The best works in this show, Gossling’s included, speak very eloquently about the post-digital, and how artists are motivated into hybrid forms of production, always acknowledging and working in a context of the saturation of the digital.

The notion of saturation, and its implications of the dissolution and liquidity, itself saturates the show: the first work, Maurice Carlin’s monumental print, scrolling down from the ceiling of the vide space is in one sense a spectral ancestor of Monet’s waterlilies, but with gashes and pustules of CMYK colour oozing up from behind the serine blue and greens of the pond, and white pixel-like rectangles plugging up the gaps; London Fieldworks’ 3D image of data collected from Gustav Metzger’s brain while he thought of nothing, is presented on a screen with a trickling sound – perhaps of information leaking inexorably back in?

Marilène Oliver’s glitch-sculpture of body parts fused in the heart of the 3D scan/print machine hang in the chute of the gallery corridor, their surfaces mid-ripple as though submerged; Jo Stockham’s etherized black and white shot of an element of the London skyline, seen perhaps through a teary bus window, but now writhing with red in its afterlife as a veined and depthless skin.

Using damage and error to expose the affectivity of a medium, particularly in the context of the digital is the central mode of Glitch Art. I have already used the term glitch to describe the aesthetic of Marilène Oliver’s sculptures, and the traces of digital-to-digital scan in Gosling’s work and the rich material pixilation of Christine Baumgarner’s inscription of CCTV camera stills into largescale wood prints, also contain these signatures.

If there is a criticism to be leveled at these admirable and, frankly gorgeous, works. It is in their distance from what Rosa Menkman refers to as the moment(um) of the glitch. In the medium of print-making, the material fact of the object dominates, and with this show, no-matter the stated and playful interest in the ‘between-state’ of scanning, there remains the focus on material production – and therefore an irrefutable commodification.

Prints on archival paper and tempered steel, casts in plaster and large-scale hardwearing plastics, each speak of an appropriation of the tactical and fluid glitch, and its migration into commodifiable form. Maurice Carlin’s large-scale printwork could adorn a restaurant wall, just as Monet’s waterlilies functioned during his era, and Oliver’s sculptures also speak and modernise the language of sculpture as produced for private collections through the ages.

There are works also which say nothing of the ‘post-digital’, such as Imogen Stidworthy’s Sacha, a deeply thoughtful study of a wire-tap transcription ‘artist’ Sacha van Loo. Stidworthy’s enigmatic works are often hard to pin down thematically, and here it feels like the loft-type space of Gallery 3 has been used as an outer limit to the reach of the show. And then there are other works that say nothing at all and lessen the show’s conceptual rigor. I see Jeaneu Project’s peice, and think ‘smudge lawn’. I see a Cory Archangel print and a Rachel Whitereed miniture and their names flash through my consciousness like a Google Glass press release.

Truly though, this is a really refreshingly vibrant and precient show at the Bluecoat, and a great partner to the Mark Lecky exhibition featured at the venue last year in its pressing contemporaneity. The exhibition has also been a fulcrum for a really interesting series of events which have dealt with image production – including a day of talks and presentations, i-Scan, artist talks from contributing artists such as Imogen Stidworthy, and independently curated events such as the second in Deep Hedonia’s excellent Space/Sound series, where artists such as Madeline Hall, Jon Baraclough, Simon Jones and Andy Hunt explored the multiple angles from which digital scanning can be exploited as a performance and av medium. As with the Mark Lecky show, there is something about the context of the Bluecoat, as Liverpool’s most paradoxical space, which delivers an archival retrospective out of the most up-to-date material, and this tension is what pulls appart the body of works before us.

The Rubik’s Cube is not just a forgotten toy from the 80’s. The fact is that it’s even more popular than ever before. You can play with this great puzzle here.

In “How Readers Will Discover Books In Future“, science fiction author Charles Stross envisions a future in which weaponized eBooks demand your attention by copying themselves onto your mobile devices, wiping out the competition, and locking up the user interface until you’ve read them.

This is only just science fiction. Even the earliest viruses often displayed messages and malware that denies access to your data until you pay to decrypt it already exist. ePub ebooks can execute arbitrary JavaScript, and PDF documents can execute arbitrary shell scripts. Compromised PDFs have been found in the wild. Stross’s weaponized ebooks are not more than one step ahead of this.

Why would eBooks want to act like that? To find readers. In the attention economy, the time required to read a book is a scarce resource. Most authors write because they want to be read and to find an audience. Stross’s proposal is just an extreme way of achieving this. In Stross’s scenario, authors are like the criminal gangs that use botnet malware to get your computer to pursue their ends rather than your own, use adware to coerce you into performing actions that you wouldn’t otherwise, or use phishing attacks to get scarce resources such as passwords or money from users.

As so much new art is made that even omnivorous promotional blogs like Contemporary Art Daily cannot keep up, scarcity of attention becomes a problem for art as well as for literature. And when people do visit shows they spend more time reading the placards than looking at the art. In these circumstances Stross’s strategies make sense for art as well. Particularly for net art and software art.

A net or software artwork that acted like Stross’s vampire eBooks would copy itself onto your system and refuse to unlock it until you have had time to fully experience it or have clicked all the way through it. It could do this in web browsers or virtual worlds as a scripting attack, on mobile devices as a malicious app, or on desktop systems as a classical virus.

Unique physical art also needs viewers. Malicious software can promote art, taking the place of private view invitation cards. Starting with mere botnet spam that advertises private views, more advanced attacks can refuse to unlock your mobile device until you post a picture of yourself at the show on Facebook (identifying this using machine vision and image classification algorithms), check in to the show on FourSquare, or give it a five star review along with a write-up that indicates that you have actually seen it. In the gallery, compromised Google Glass headsets or mobile phone handsets can make sure the audience know which artwork wants to be looked at by blocking out others or painting large arrows over them pointing in the right direction.

Net art can intrude more subtly into people’s experiences as aesthetic intervention agents. Adware can display art rather than commercials. Add-Art is a benevolent precursor to this. Email viruses and malicious browser extensions can intervene in the aesthetics of other media. They can turn text into Mezangelle, or glitch or otherwise transform images into a given style. In the early 1990s I wrote a PostScript virus that could (theoretically) copy itself onto printers and creatively corrupt vector art, but fortunately I didn’t have access to the Word BASIC manuals I needed to write a virus that would have deleted the word “postmodernism” from any documents it copied itself to.

Going further, network attacks themselves can be art. Art malware botnets can use properties of network topography and timing to construct artworks from the net and activity on it. There is a precursor to this in Etoy’s ToyWar (1999), or EDT’s “SWARM” (1998), a distributed denial of service (DDOS) attack presented as an artwork at Ars Electronica. My “sendvalues” (2011) is a network testing tool that could be misused, LOIC-style, to perform DDOS attacks that construct waves, shapes and bitmaps out of synchronized floods of network traffic. This kind of attack would attract and direct attention as art at Internet scale.

None of this would touch the art market directly. But a descendant of Caleb Larsen’s “A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter” (2012) that chooses a purchasor from known art dealers or returns itself to art auction houses then forces them to buy it using the techniques described above rather than offering itself for sale on eBay would be both a direct implementation of Stross’s ideas in the form of a unique physical artwork and something that would exist in direct relation to the artworld.

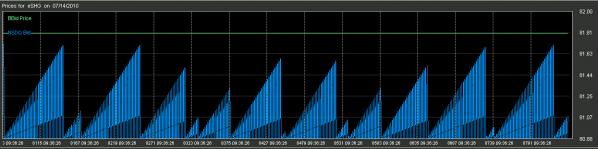

Using the art market itself rather than the Internet as the network to exploit makes for even more powerful art malware exploits. Aesthetic analytics of the kind practiced by Lev Manovich and already used to guide investment by Mutual Art can be combined with the techniques of stock market High Frequency Trading (HFT) to create new forms by intervening in and manipulating prices directly art sales and auctions. As with HFT, the activity of the software used to do this can create aesthetic forms within market activity itself, like those found by nanex. This can be used to build and destroy artistic reputations, to create aesthetic trends within the market, and to create art movements and canons. Saatchi automated. The aesthetics of this activity can then be sold back into the market as art in itself, creating further patterns.

The techniques suggested here are at the very least illegal and immoral, so it goes without saying that you shouldn’t attempt to implement any of them. But they are useful as unrealized artworks for guiding thought experiments. They are useful for reflecting on the challenges that art in and outside the artworld faces in the age of the attention-starved population of the pervasive Internet and of media and markets increasingly determined by algorithms. And they are a means of at least thinking through an ethic rather than just an aesthetic of market critique in digital art.

The text of this article is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

Since the turn of the millennium, there have been shifts toward new forms of sociopolitical dissent. These include strategies such as cellular forms or resistance including asymmetrical warfare like global insurgencies, the use of social media. Examples would be Twitter and Facebook in their ability to lens dissent for actions in Syria, Egypt and Tunisia, Wikileaks and its ability to mirror, and politics that use anarchistic forms of collective action such as the Occupy Movement. Although my focus is more concerned with the Occupy Movement, what is evident is what I call an amorphous politics of dissent. Amorphous is defined as “without shape”, and can be applied to most of the mise en scenes listed above.

The dissonance of power in regards to conventional politics can be seen in its structure. For example, the nation-state has a tiered, hierarchical structure of power relations. There is a President or Prime Minister, a legislative organ of MPs or Representatives, Parliaments, Houses, and the like, a Judicial organ, and a Military organ that includes any number of militia and police. Although I am referring mostly Western forms of government, we can also argue for the hierarchical form in terms of the Corporation, with its CEO, Board, Shareholders, Managers, and Workers. This can be expanded historically to Feudal lords with their retinue of Vassals, Nobles and Warlords with their coteries of Warriors and support personnel. The point is that conventional power typically operates in a pyramidal command and control hierarchy with a centralized Leader at the “capstone”. One can argue that the pyramid may have different shapes, or angles of distribution of power, but in the end, there is usually a terminal figure of authority. To put it in terms of stereotypical Science Fiction terminology, when the alien comes to Earth, the standard story is that it pops out of the spacecraft and says, “Take me to your leader.” This signifies the hegemonic paradigm of Leadership as the central gestalt of First world power. Leadership, then, is the conventional paradigm of power in Western culture, and dominates the industrialized world.

Territorialization refers to the exertion of power along perimeters, or borders. Functionaries expressing the constriction of territory include customs agents, and border patrols; but are terminally expressed by the military wing of the nation state. This military is also generally pyramidally constructed in terms of Generals, Colonels, and other officers leading Battalions, Regiments and Divisions, which are organized as defenders of a nation’s sovereignty. These military organs are conversely best optimized to exert their power against either parallel or subordinate structures. Parallel structures include the armies of other nations, their Officers, et al, and their troops and ordnance that possess a similar organization. Conversely, subordinate structures over which military powers can exert power over are domestic masses that can be overrun with overwhelming power, although these forces are more specialized (such as National Guards or Gendarmeries). In the conventional sense, power is expressed orthogonally, whether it is against equal or subordinate forces.

Another aspect of this conversation relates to the expression of power/force through conflict and violence, but has its inconsistencies The examples I will use from American pop culture I will use in this missive to explain amorphous action may be violent in nature, but the violent nature of these examples do not relate to the paradigmatic jamming of conventional power. Their citation is related more to the fact of conventional power’s orthogony, or parallelism of exertion of power to similar structures or dominance of the subordinate, and the panic state it experiences when confronted with non-conventional difference or passive resistance. We could express the power relationships between amorphous politics and conventional power in terms of a tetrad in terms of examples of violent and peaceful exertion of amorphous dissent as well as orthogonal conflict. We could cite the Occupy movement as a site of passive, and the Tunisian uprising as violent exemplars of amorphous conflict or dissent. Conversely, the Gandhi/King is a non-violent model of as orthogonal/hierarchical/led action, and World War Two as conventional orthogonal conflict. What is important here is the inability of the conventional politics and power to cope with leaderless, non-hierarchical, non-orthogonal discourse that refuses to talk in like terms such as centralization, leadership and conventional negotiations that include concepts such as “demands”. This is where the site of cognitive dissonance erupts, often resulting in a panic state or in the “figureheading” of dispersed networks of power.

The need for the traditional power structure to focus identity on the antagonist in terms of figureheads is evident in the Middle East and Eurasia in the personification of terrorist and insurgent networks, but is more simply illustrated in the films Alien and Aliens, and Star Trek: The Next Generation. Both of these feature their respective antagonists, the “alien” as archetypal Other, and the Borg, symbol of autonomous, collective community. In Alien, the crew of the Nostromo encounters an alien derelict ship that has been mysteriously disabled to find a hive of eggs of alien creatures whose sole role is the creation of egg factories for further reproduction. At the onset of the franchise, pilot Ellen Ripley is positioned as the “everywoman” placed in the center of cataclysmic events. In the Alan Dean Foster book adaptation, and an extended edit of the Scott film, Ripley finds during her escape from the ship that Captain Dallas has been captured and organically transformed into a half-human egg-layer whom she immolates with a flamethrower. However, in the Aliens sequel, the amorphous society of the self-replicating aliens has been replaced by a centralized hive, dominated by a gigantic Queen that threatens to impregnate the daughter-surrogate Newt. This transformation from a faceless to centralized threat creates a figurehead for the threat and establishes a clear protagonist/antagonist relationship, and establishes traditional orthogony.

This simplification of dialectic of asymmetrical politics is also evidenced in Star Trek: The Next Generation by the coming of the Borg, a collective race of cybernetic individuals. Although representations of the Borg vary as to fictional timeline, in televised media they began as a faceless hive-mind, which abducted Captain Jean-Luc Picard as a mouthpiece, not as a leader. It was inferred that if one sliced off or destroyed a percentage of a Borg ship, you did not disable it; you merely had the percentage left coming at you just as fast. However, by the movie First Contact, the Borg now possesses a hierarchical command structure to their network and, more importantly, a queen. With the assimilated and reclaimed android Lieutenant Data, the crew of the Enterprise infiltrates higher level functions of the Borg Collective, effectively shutting down the subordinate elements of the Hive. In addition, the Queen/Leader is defeated, assuring traditional figurehead/hierarchy power relations rather than having to deal with the problems of the amorphous, autonomous mass. There are other “amorphous” metaphors in cinema that address the issue of amorphousness. These include the 1958 movie, The Blob, in which a giant amoeba attacks a small town and grows as it engulfs everything. Another is The Thing, about a parasitic alien that doppelgangs its victims, creating another form of faceless threat. Lastly, we have the classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers where alien plant “pods” would bear fruit of duplicates of living people, giving a metaphor for the Communist threat of the Red Scare originating during the Cold War. Perhaps these are historical references to mediated expressions of anxiety in regard to autonomy’s threats to regimented/striated hegemony, stating that this sort of anxiety and terror are not new.

One of the most asymmetric cultural Western interventions in relation to constructs of traditional power is the involvement of Anonymous as part of the Occupy Movement. Anonymous, which has been called a “hacker group” in the mass media, is a taxonomy created on the online image sharing community 4chan.org, arising from the practice of posting “anonymously” unless one wants to use a name, or handle. Although the idea of Anonymous is at best an ad hoc grouping, the use of the “group” name has been ascribed to various factions. According to The State News, “Anonymous has no leader or controlling party and relies on the collective power of its individual participants acting in such a way that the net effect benefits the group.“ The idea of Anonymous fits with the “faceless collectives” mentioned above, and certainly presents an asymmetric, if not non-orthogonal, exercise of power. Anonymous first rose as a voice of dissent that emerged against the Church of Scientology (see Project Chanology), where flash mobs of individuals in Guy Fawkes masks and suits arrived to protest at sites around the world, with boom boxes playing “The Fresh Prince of BelAir”, a popular agitational or “trolling” anthem. It has engaged in other activities, including hacking credit card infrastructures opposed to handling donations to Wikileaks and creating media around Occupy Wall Street. However, without a clear infrastructure and only transient figureheads, Anonymous functions as an organizing frame for a cloud of individuals interested in various collective actions, and represents an indefinite politics based on networked culture. In an expected exercise of force, during the actions against elements opposed to Wikileaks, conventional power struck back wherever it could against members of Anonymous, by arresting over 21, some violently, in July during the actions against credit providers boycotting Wikileaks. This exercise of power was repeated in September, with admonitions about the arrests appearing on YouTube thereafter. Anonymous has also posted videos in support of the Occupy movement. Such a response is not surprising, but is the exact response to non-orthogonal dissent under our model. The problem is that in arresting any number of Anonymous members, traditional power is confronted with the first, distributed model of the Borg that merely exists minus two or twenty members.

Another dissonance between the Occupy Movement and conventional politics is the perceived lack of agenda. This is due to its dispersion of discourse in giving its constituents collective importance in voice. What is the agenda of the disempowered 99% of Americans, or world citizens marginalized by global concentration of wealth? Simply put, the agenda is for the disempowered to be heard. What does that mean? It means anything from forgiveness of student loans to jobs to redistribution of wealth to affordable health care, and so on. It isn’t a list; it is a call to systemic change of the means of production, distribution of wealth and empowerment in political discourse. It isn’t as simple as “We want a 5% cut in taxes for those making under $30,000.” It’s more akin to “We’re tired that there are so many sick, hungry, poor and uneducated, and we want it to end. Let’s figure it out.” It is the invitation to the beginning of a conversation that has no simple answers other than the very alteration of a paradigm of disparity that has arisen over the past 40 years through American capitalism.

The last challenge to the traditional power discourse is that of passive resistance. This is not a new strategy, especially under the aegis of Gandhi and King’s movements. However, it is traditional power’s mere tolerance of nonviolent resistance that does not result in violence. As we can see from the UC Davis assaults and the dispersions after the second month anniversary, conventional power exerts its force against, as Brian Holmes put it, “anomalies” so that the system can be restored and the commodifiable classes are reintegrated into the system to reproduce its agendas. As long as resistance does not present undue inconvenience for the circulation of power and capital, it is allowed. Once it loses its patience with non-orthogonal forces, or if materially sacralized spaces, like Wall Street are threatened, the hegemonic order is reified. The irony of the technical loophole of Zucotti Park being privately owned and having few rules allowed the Occupy movement also highlights the tenuousness of public discourse in Millennial America. However, even with this oddity, on the two-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, force has begun to be used against the occupiers as traditional power’s patience grows thin with amorphous politics. In the streets, the marches are split up, and rules about occupation begin to be enforced with cupidity. As said before, hegemonic patience has worn thin, with assaults/dispersions taking place in Oakland, Davis, Philadelphia, and New York, among others. However, the movement moves forward for the moment.

Amorphous politics is based on plurality, collectivism, dispersion and ideas. The hierarchical nation-state has no idea what to do with the amorphous blob as it grows except to try to contain it, but as with Anonymous, it is a whack-a-mole game. If one smacks down one protest, two pop up across town, or five websites pop up on the Net. Shut down Wikileaks, and a thousand mirror sites show up. People in the streets swarm New York and other cities throughout the US, and the world, and conflict arises. Asymmetry and amorphousness are dissonances to traditional power. Ideas in themselves are not hierarchical.

Desires sometimes have no agendas.

Sometimes people want what is right, and all of it.