The Hologram is a mythoreal viral four-person health monitoring and diagnostic system practiced by people from couches all over the world. Three non-expert participants create a three-dimensional or “holographic” map of a fourth participant’s physical, psychological and social health, and each becomes, the focus of three other people’s care in an expanding network.

The premise is simple:

The Hologram was incubated at Furtherfield as part of CreaTures, Cassie Thornton during her artist residency in 2020, just as the Covid pandemic was taking hold. Artistic Direction, workshop design and facilitation by Cassie Thornton. Workshop design and facilitation by Lita Wallis.

Workshop 1 Is this the end or the beginning? (a course for collective health) Asking for help as a New World – Spring 2020

Workshop 2 We must begin again: Asking for help as a new world – Autumn 2020, supported by CreaTures

Hologram LARP Live Action Role-Play We were made for this // 2050 Fugitive Planning – 2021, supported by CreaTures.

The Hologram was incubated at Furtherfield in 2020 and is now practiced in many different languages by thousands of people around the world. Find out how to get involved here.

The CreaTures project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870759. The content presented represents the views of the authors, and the European Commission has no liability in respect of the content.

Registration is now open for the Peer to Peer: UK/HK Online Festival, an online platform for cultural exchange between the UK and Hong Kong’s Visual Arts sectors as they interrogate topical themes of our time including art & activism, art in the digital realm and the climate emergency.

The festival has announced its programme of public events and panel talks, alongside an online exhibition of digital artwork including existing artworks and 5 brand new commissions from artists based in the UK and Hong Kong.

The Peer to Peer: UK/HK Online Festival will take place entirely online between 11-14 November 2020 on peertopeerexchange.org. The festival is free and open to all.

Originally envisaged as a physical exchange between UK and Hong Kong visual arts networks, the project has responded to the Covid-19 pandemic to become an online space where meaningful exchange can happen and partnerships and relationships can be forged.

Curated by independent curator Ying Kwok, the festival has announced its public events programme. These will be a series of engaging public debates with artists, curators and visual arts leaders from across Hong Kong and the UK.

Arts Council England’s Director International, Nick McDowell, will open the event on Wed 11 November alongside Ying Kwok and festival organisers Lindsay Taylor (University of Salford Art Collection), Sarah Fisher (Open Eye Gallery) and Zoe Dunbar (Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art).

“This is such a heartening example of international exchange and partnership evolving despite the global pandemic. Artists may not be able to travel but – as this project shows – they can connect and innovate in the digital space.” Nick McDowell, Director International, Arts Council England.

The panel events will include:

“The themes that will be explored in the festival have grown from mutual interests from partners in Hong and the UK as we respond to timely global events and issues. It reflects how we have co-curated the festival with all partners in an experimental approach for international collaboration. We see this festival as a springboard for meaningful exchange between Hong Kong and the UK in the future.” Ying Kwok, Festival Director

Accompanying the public events will be an entirely online exhibition of digital artworks from artists based in the UK and Hong Kong.

It will include five brand new commissions, nominated and selected by UK and Hong Kong partner organisations taking part in Peer to Peer: UK/HK. They include UK based artists Antonio Roberts – nominated by Furtherfield, Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley and Hetain Patel, and Hong Kong based artists Lee Kai Chung and Sharon Lee Cheuk Wun.

The commissions will be accompanied by over 15 existing digital artworks from nominated artists, to be announced.

As part of the exchange between UK and Hong Kong, artists based in each country have also been nominated for a series of online residencies hosted on the social media accounts of partner organisations in the corresponding country. The artists will respond to different themes set by the host organisation.

The residency exchange began last weekend with Hong Kong International Photo Festival nominating Raul Hernandez, a Spanish born artist living in Hong Kong, to take over Open Eye Gallery’s Instagram channel for four consecutive weekends as part of his Room Available project exploring being a foreigner in a new environment.

Hong Kong’s HART gallery have also nominated Hong Kong artist Wu Jiaru who will be taking over Furtherfield’s Instagram channel from 19 – 29 October, as an extension of their work currently displayed in HART’s exhibition Household Gods.

Further residencies will be announced on the Peer to Peer: UK/HK Residencies page.

Full programme below:

Wednesday 11 November 2020

Opening session: Welcome and introductions

11.30am UKT / 7.30pm HKT

Outline of programme and launch of online commissions

Speakers: Nick McDowell (Director International, Arts Council England), Ying Kwok (Peer to Peer: UK/HK Festival Director), Sarah Fisher (Director, Open Eye Gallery), Lindsay Taylor (Curator, University of Salford Art Collection), Zoe Dunbar (Director, Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art)

Panel One: Local/international artist exchange in time of global pandemic

12pm UKT / 8pm HKT

The values of becoming artist-led as a radical and necessary approach to responding to a changing international world.

Chair: Wing Sie Chan (a-n The Artists Information Company, UK)

Panel: Angel Leung (Videotage, HK), Dorcas Leung ( HART, HK), Jamie Wylde (Videoclub, UK)

Panel Two: Working with communities

1:15pm UKT / 9:15pm HKT

How do visual arts organisations in the UK and Hong Kong connect with communities in a rapidly changing political and social world.

Chair: James Green (Newlyn Art Gallery and The Exchange, UK)

Panel: Charlotte Frost (Furtherfield, UK), Liz Wewiora (Open Eye Gallery, UK), Bruce Li (Centre for Heritage Arts & Textile, HK), Ivy Lin (Oil Street Art Space, HK)

Thursday 12 November 2020

Panel Three: Isn’t all art activism?

12pm UKT / 8pm HKT

Activision: The philosophy and principle of activism in art. Isn’t all art activism?

Chair: Skinder Hundal (New Art Exchange, UK)

Panel: Chantal Wong (Eaton Workshop, HK), Yang Yeung (1983, HK), Helen Wewiora (Castlefield Gallery, UK)

Panel Four: Placemaking: utopian vision v social experiment

1:15pm UKT / 9:15pm HKT

Challenges and barriers in face of art programming for placemaking and community building in Hong Kong and the UK.

Chair: Jeannie Wu, (HART, UK)

Panel: Fiona Venables (Milton Keynes Arts Centre, UK), Bess Chan (Hong Kong International Photo Festival, HK), Maddi Nicholson, (Artist/Art Gene, UK)

Friday 13 November 2020

Panel Five: Climate: The Defining Emergency of Our Times

12pm UKT / 8pm HKT

How can we join forces to engage and empower the public, or influence policy, towards a greener recovery?

Chair: Sarah Fisher (Open Eye Gallery, UK)

Panel: Patrick Fung (Clean Air Network, HK), Colette Bailey (Metal, UK), Richard Fitton (Energy House, University of Salford, UK),

Panel Six: Archives/collections

1:15 pm UKT / 9:15pm HKT

A discussion of the profound changes recently affecting archives and collections; what they contain, who they represent and how they are accessed.

Chair: Paul Hermann (Redeye, the Photography Network / The Photographic Collections Network, UK)

Panel: John Tain (Asia Art Archive, HK), Joseph Chen (Videotage, HK), Stephanie Fletcher (University of Salford Art Collection, UK), Melanie Keen (Wellcome Collection, UK)

Saturday 14 November 2020

Panel Seven: Exploring the realm of “online”

11am UKT / 7pm HKT

An online exhibition or an exhibition online? Creating and curating online art as an artistic practice – not a solution.

Chair: Vennes Cheng (Academic and Curator, HK)

Panel: Jacob Bolton (Peer to Peer: UK/HK), Peter Bonnell (Derby Quad, UK), Antonio Roberts (Artist, UK)

Closing Remarks

12:15pm UKT / 8.15pm HKT

Chairs: Lindsay Taylor (University of Salford Art Collection) and Ying Kwok (Festival Director)

All partners and panelists invited to share their highlights of the Festival

Ends

1pm UKT / 9pm HKT

UK partners

a-n – The Artists Information Company, Castlefield Gallery, Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art (CFCCA), Firstsite, Furtherfield, Milton Keynes Arts Centre, New Art Exchange Nottingham, Newlyn Art Gallery / The Exchange, Nottingham Contemporary, Open Eye Gallery, QUAD Derby, Red Eye Photography Network, University of Salford Art Collection, and Wellcome Collection.

Hong Kong partners

1983, 1a space, Blindspot Gallery, Centre for Heritage Arts and Textile (CHAT), Eaton Workshop, HART, Hong Kong International Photo Festival, Hong Kong Visual Arts Centre, Jockey Club Creative Arts Centre, K11 Art Foundation, Oil Street Art Space, Videotage and WMA.

Furtherfield has worked with decentralised arts and technology practices since 1996 inspired by free and open source cultures, and before the great centralisation of the web.

Visit DECAL website

10 years ago, blockchain technologies blew apart the idea of money and value as resources to be determined from the centre. This came with a promise, yet to be realised, to empower self-organised collectives of people through more distributed forms of governance and infrastructure. Now the distributed web movement is focusing on peer-to-peer connectivity and coordination with the aim of freeing us from the great commercial behemoths of the web.

There is an awkward relationship between the felt value of the arts to the majority and the financial value of arts to a minority. The arts garner great wealth, while it is harder than ever to sustain arts practice in even the world’s richest cities.

In 2015 we launched the Art Data Money programme of labs, exhibitions and debates to explore how blockchain technologies and new uses of data might enable a new commons for the arts in the age of networks. This was followed by a range of critical art and blockchain research programming:

Building on this and our award winning DAOWO lab and summit series, we have developed DECAL – our Decentralised Arts Lab and research hub.

Working with leading visionary artists and thinkers, DECAL opens up new channels between artworld stakeholders, blockchain and web3.0 businesses. Through the lab we will mobilise research and development by leading artists, using blockchain and web 3.0 technologies to experiment in transnational cooperative infrastructures, decentralised artforms and practices, and improved systems literacy for arts and technology spaces. Our goal is to develop fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

For more see our Art and Blockchain resource page.

I arrived at the Transmediale festival late Friday afternoon, which was hosted as usual at Das Haus der Kulturen der Welt (The House of World Cultures) in Berlin. The area where the building is sited was destroyed during World War II, and then at the height of the Cold War, it was given as a present from the US government to the City of Berlin. As a venue for international encounters, the Congress Hall was designed as a symbol of ‘freedom’, and because of its special architectural shape the Berliners were quick to call the building “pregnant oyster” [1] The exterior was also the set for the science fiction action film Æon Flux in 2005. Both past references link well with this festival’s use of the building. I remember during my last visit, in 2010, standing outside the back of the building watching an Icebreaker cracking apart the thick ice in the river. The sound of the heavy ice in collision with the sturdy boat was loud and crisp. This sound has stayed with me so that whenever I hear a sound that is similar I’m immediately transported back to that point in time. Unfortunately, this time round there was no snow, instead the weather was wet, warm and slighty stormy.

Last year’s festival explored the marketing of big data in the age of social control. This year, the chosen format was entitled conversationpiece, with the aim of enabling a series of dialogues and participatory setups to talk about the most burning topics in post-digital culture today. To give it grounding and historical context the theme was pinned to the “backdrop of different processes of social transformation, 17th and 18th century European painters perfected the group portrait painting known as the “Conversation Piece” in which the everyday life of the aristocracy was depicted in ideal scenes of common activity.” In recent years the festival has scafolded its panels, workshops and keynotes to grand, central themes to guide its peers and visitors, along with a large-scale curated exhibition. If we view the four interconnected thematic streams- Anxious to Act, Anxious to Make, Anxious to Share and Anxious to Secure – we might guess that the festival curators are also anxious to save all the resources (and celebrations) for next year, which is after all, Transmediale’s 30th birthday.

So, I was curious to see how my brief time here would unfold…

This review is focused on the hybrid event Off-the-Cloud-Zone. It featured presentations, talks and workshops, starting at 11 am, going on until 8pm. Hardcore indeed. It demanded total dedication, which unfortunately I was not able to give. However, I did offer my attention to the rest of the proceedings from lunch time until the end. It was moderated by Panayotis Antoniadis, Daphne Dragona, James Stevens and included a variety of speakers such as: Roel Roscam Abbing, Ileana Apostol, Dennis de Bel, Federico Bonelli, James Bridle, Adam Burns, Lori Emerson, Sarah T Gold, Sarah Grant, Denis Rojo aka Jaromil, George Klissiaris, Evan Light, Ilias Marmaras, Monic Meisel, Jürgen Neumann, Radovan Misovic aka Rad0, Natacha Roussel, Andreas Unteidig, Danja Vasiliev, Christoph Wachter & Mathias Jud, and Stewart Ziff.

The Off-the-Cloud-Zone day event was a continuation of last year’s offline networks unite! panel and workshops. Which also originated from discussions on a mailing list called ‘off.networks’ with researchers, activists and artists working together around the idea of an offline network operating outside of the Internet. The talks concentrated on how over recent years there has been a growing scene of artists, hackers, and network practitioners, finding new ways to ask questions through their practices that offer alternatives in community networks, ad-hoc connectivity, and autonomous systems of sensing and data collecting.

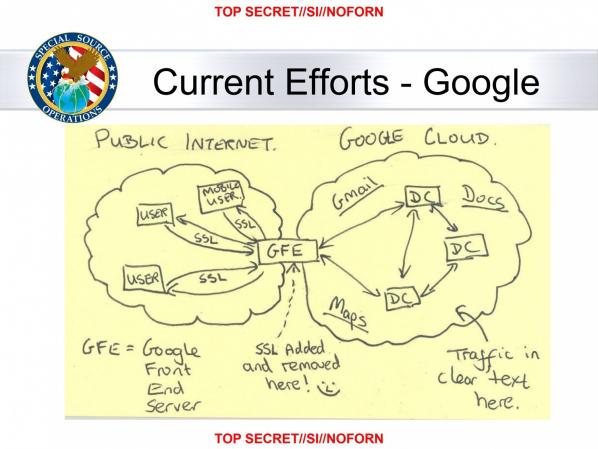

Disillusionment with the Internet has spread widely since 2013, when Edward Snowden the US whistleblower leaked information on numerous global surveillance programs. Many of these programs are run by the NSA and Five Eyes with the cooperation of telecommunication companies and European governments raising big questions about privacy and exploitation of our online (interaction) data. This concern is not only in relation to spying corporations, dodgy regimes and black hat hackers, but also our governments. “The idea of privacy has been flipped on its head. People don’t have to disclose their own information voluntarily anymore; it’s being taken from them regardless of their wishes.” [2] (Nowak 2015)

“The NSA’s principal tool to exploit the data links is a project called MUSCULAR, operated jointly with the agency’s British counterpart, the Government Communications Headquarters . From undisclosed interception points, the NSA and the GCHQ are copying entire data flows across fiber-optic cables that carry information among the data centers of the Silicon Valley giants.” [3] (Gellman and Soltani, 2013)

The above slide is from an NSA presentation on “Google Cloud Exploitation” from its MUSCULAR program. The sketch shows where the “Public Internet” meets the internal “Google Cloud” where user data resides. [4]

A legitimate concern for anyone wishing to read the contents of the leaked Snowden files, is that they will be spied upon as they do so. Evan Light has been working on finding a way around this problem, and at the Off-the-Cloud-Zone day event he presented his project Snowden Archive-in-a-Box. A stand-alone wifi network and web server that permits you to research all files leaked by Edward Snowden and subsequently published by the media. The purpose of the portable archive is to provide end-users with a secure off-line method to use its database without the threat of surveillance. Light says, usually the wifi network is open, but users do have the option to make their own wifi passwords and also choose their encryption standard.

Snowden Archive-in-a-Box is based on the PirateBox, originally created by David Darts who made his in order to distribute teaching materials to students without the hassle of email. It is based on a RaspberryPi 2 mini-computer and the Raspbian operating system. All the software is open-source and its most basic setup can run on one RaspberryPi. In his talk Light said that a more elaborate version would use high-quality battery packs and this adds power for autonomy, along with the wifi sniffer that is running on a secondary RaspberryPi and a flat-screen for playing back IP traffic. If you’re interested in building your own private, pirate Archive-in-a-Box, visit Light’s web site for instructions on how to.

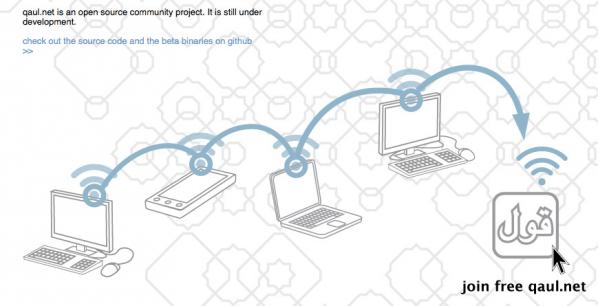

Christoph Wachter’s and Mathias Jud’s work, directly engages with refugees and asylum seeker’s social situations, policies, and the migrant crisis. They’ve worked together on participatory community projects since 2000 and have received many awards. For instance, take a look at their digital communications tool qaul.net which is designed to counteract communication blackouts. It has been used successfully in Egypt, Burma, and Tibet, and works as an alternative to already existing government and corporate controlled communication pathways. But, it also offers vital help when large power outages occur, especially in areas in the world suffering from natural disasters. The term qaul is Arabic and means ‘opinion, say, talk or word’. Qaul is pronounced like the English word ‘call’.

It creates a redundant, open communication code where wireless-enabled computers and mobile devices can directly initiate a fresh, unrestricted and spontaneous network. This includes the enabling of Chat, twitter functions and movie streaming, independent of Internet and cellular networks. It is also accessible to a growing Open Source Community who can modify it freely.

Wachter and Jud also discussed another project of theirs called “Can You Hear Me?”, a WLAN / WiFi mesh network with can antennas installed on the roofs of the Academy of Arts and the Swiss Embassy in Berlin, which was located in close proximity to NSA’s Secret Spy Hub. These makeshift antennas made of tin cans were obvious and visible for all to see. The Academy of Arts joined the project building a large antenna on the rooftop, situated exactly between the listening posts of the NSA and the GCHQ to enable people to directly address surveillance staff listening in. While installing the work they were observed in detail by a helicopter encircling overhead with a camera registering each and every move they made, and on the roof of the US Embassy, security officers patrolled.

“The antennas created an open and free Wi-Fi communication network in which anyone who wanted to would be able to participate using any Wi-Fi-enabled device without any hindrance, and be able to send messages to those listening on the frequencies that were being intercepted. Text messages, voice chat, file sharing — anything could be sent anonymously. And people did communicate. Over 15,000 messages were sent.” [5] (Jud 2015)

A the end of their presentation, they said that they will be implementing the same system at hotspots deployed in Greece by the end of the month. And I believe them. What I find refreshing with these two, is their can do attitude whilst dealing with political forces bigger than themselves. It also gives a positive message that anyone can get involved in these projects.

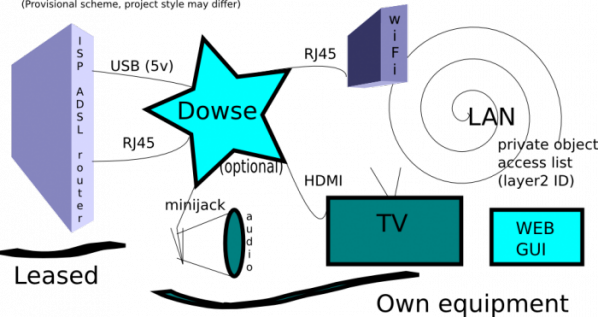

And then, it was the turn of the well known team at Dyne.org to discuss a project of theirs called Dowse, which is ‘The Privacy Hub for the Internet of Things’. They said (taking turns, there was about 5 of them) that the purpose of Dowse is to perceive and affect all devices in the local, networked sphere. As we push on into the age of the Internet of Things, in our homes everything will be linked up.

“Those bathroom scales and home thermostats already talk to our smartphones and in some cases think for themselves.” [6] (Nowak 2015)

As these ubiquitous computers communicate to each other even more, control over these multiple connections will be essential. We will need to know how to interact beyond the GUI interfaces and think about who has access to our private, common and public information. A whole load of extra information will be available without our consent.

Dowse was conceived in 2014 as a proof of concept white paper by Denis Rojo aka Jaromil. Early contributors to the white paper and its drafting process includes: Hellekin O. Wolf, Anatole Shaw, Juergen Neumann, Patrick R McDonald, Federico Bonelli, Julian Oliver, Henk Buursen, Tom Demeyer, Mieke van Heesewijk, Floris Kleemans and Rob van Kranenburg. I downloaded the white paper and is definitely worth reading.

The Dowse project aims to abide to the principles stated in the Critical Engineers Manifesto, (2011). Near the very end of the talk they announced to the audience an open call for artists and techies everywhere to get involved and jump into the project to see what it can do. This is a good idea. If there is no community to make or break platforms, hardware and software, then there is a limited dialogue around the possibilties of what a facility realistically might achieve. Not just that, they want artists to make art out of it. I know there are some pretty clever tech-minded geeks out there, who will in no doubt take on the challenge. However, once those who are not so literate in the medium are able to exploit the project, it will surely fly. It’s going to be interesting, because if you look at the 3rd point in the Critical Engineers Manifesto, it says “The Critical Engineer deconstructs and incites suspicion of rich user experiences.” I’m thinking, that this number 3 element needs to treated with caution. If they really wish to open it up to a diverse user base, to engage with its potentialities, creatively and practically; thus, allow new forms of social emancipation to evolve as ‘freedom with others’. There needs to be an active intent to avoid a glass ceiling based on technical know-how. It’s a promising project and I intend to explore it myself and see what it can do and will invite other people within Furtherfield’s own online, networks to join in and play, break, and create.

Our final entry is the Sarantaporo Project which is situated in the North of Greece. A village in the mountains just west of Mount Olympus in Central Greece close to Thessaloniki, Macedonia and Larisa. The country has been in recession for over 6 years now, and many communities have had to create alternative ways of working with each other in order to survive the crisis. Over this troubling period, new forms of grass-roots coexistence, solidarity and innovation have evolved. The Sarantaporo Project is an impressive example of how people can come together and experiment in imaginative ways and exploit physical and digital networks.

Even before the economic crisis the region was already hit by poverty, and with the added pressures of imposed Austerity measures, life got even tougher. All the young were leaving and then migrating to the cities or abroad. Before the project in Sarantaporo, there was no Internet nor digitally connected networks for local people to use. This situation contributed to the digital divide and made it difficult to work in a contemporary society, when so many others in the world have been using technology to support their civic, academic and business for so many years already.

“In Greece, where unemployment reaches 30% in all ages and genders, and among the youth overpasses 50%, immediate solution for the “social issue” is more than urgent.’ [7] (Marmaras).

“Besides maintaining the network in a DIWO (Do It With Others) manner, and creating an atmosphere of cooperation among far-flung communities that were previously strangers, the Sarantaporo network is incorporating different groups of people into the community, like Farmer’s Cooperatives and techies. It is also creating an intergenerational space for learning.” [9] (Bezdommy 2016)

To resolve this issue a group of friends decided to deal with this problem by setting up a community D.I.Y wireless network to provide free internet access to 15 villages in the municipality of Elassona. “Sarantaporo.gr is an open source wireless mesh networking system that relies greatly on voluntary work both for its development and maintenance. Some volunteers are involved in the project by simply installing an antenna on their roof. Others, more actively engaged with the project, are responsible for sustaining the network by hosting meetings and answering technical questions.” [8] (Kalessi 2014) The audience was presented with snippets from a film made by the filmmaking collective Personal Cinema, about the project. It was made so the story of Sarantaporo’s DIY wireless network gets a wider reach, and that others are also inspired to do similar projects themselves.

These projects are dedicated to creating socially grounded and engaged alternatives to the proprietorial, networked frameworks that currently dominate our communication behaviours. These proprietorial systems, whether they are digital or physical are untrustworthy, and control us in ways that reflect their top-down demands but not our common needs. This reflects a wider conversation about who owns our social contexts, our conversations, our fields of practice, the structures we use, the land, the cables, our history, and so on.

Looking at the state of the planet right now you’d be forgiven for betting on a future not far from the director Neill Blomkamp’s vision in the sci-fi movie Elysium where, in the year 2159, humanity is sharply divided between two classes of people: the ultra-rich whom live aboard a luxurious space station called Elysium, and the rest who live a hardscrabble existence in Earth’s ruins. However, in the Off-the-Cloud-Zone talks we encountered an ecology of strategies to protect our own indegenous cultures from the crush of neo-liberalism, we felt part of a grounded movement discovering new conversations and new methodologies that may provide some protection against future colonisation. Perhaps there is a chance, we can build and rebuild stronger relations with each other, beyond: privilege, nation, status, gender, class, race, religion, and career.

The festival this year was less structured and more nuanced than usual. It gave conversation a greater role and a deeper social context, and opened up the process for the many to connect with the ideas being explored. The whole affair seemed to be slowed down and less caught up in the hyper-macho trappings of accelerationism. It seemed less neurotic and spending less effort to impress. I’m sure, next year, on it’s 30th anniversary, all will be sharp and amazing. However, I liked this less glossy, more messy version of Transmediale and I hope it manages to impress the wrong people again, and again.

Public Screening and Discussion at Furtherfield

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Visiting Information

THE EVENT HAS LIMITED AVAILABILITY.

PLEASE RSVP TO BOOK YOUR PLACE TO ALESSANDRA

Cornelia Sollfrank will present her latest film Giving What You Don’t Have. It features interviews with individuals Kenneth Goldsmith, Marcell Mars, Sean Dockray, Dmitry Kleiner, discussing with Sollfrank their projects and ideas on peer-to-peer production and distribution as art practice. It includes the projects ubu.com or aaaaarg.org, which combine social, technical and aesthetic innovation; they promote open access to information and knowledge and make creative contributions to the advancement and the reinvention of the idea of the commons.

The post-screening discussion will be led by Cornelia Sollfrank, Joss Hands & Rachel Baker.

On the basis of the interviews of Giving What You Don’t Have, we would like to discuss some of the issues they represent such as new forms of collaborative production, the shift of production from artefacts to the provision of open tools and infrastructures, the development of formats for self-organisation in education and knowledge transfer, (the potential and the limits of) open content licensing as well as the creation of independent ways of distributing cultural goods. An implicit part of Giving What You Don’t Have is a suggested reconceptualization of art under networked conditions.

Cornelia Sollfrank is a postmedia conceptual artist and interdisciplinary researcher and writer. She studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and fine art at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg (1987-1994). Since 1998 she has taught at various universities and written on issues in the nexus between media, art and politics. In 2011 Sollfrank completed her practice-led interdisciplinary research at Dundee University (UK) and published her PhD thesis with the title Performing the Paradoxes of Intellectual Property. In addition to her work in the artistic and academic fields, Sollfrank gathered experience in the private sector by working as product manager for Philips Media for two years (1995-1996).

Joss Hands‘ research engages the relationship between media, culture and politics. His recent work has explored the role of digital media in direct action, protest and activism, culminating in his book @ is For Activism: Dissent Resistance and Rebellion in a Digital Culture, published by Pluto Press in 2011. His previous research has explored the role of new media in formal democracy and governance as well as its cultural, economic and social impact. He has published in a number of journals such as Information, Communication and Society, Philosophy and Social Criticism and First Monday as well as writing commentary for publications such as Open Democracy, IPPR Journal, The New Left Project, and others.

Rachel Baker is a network artist who collaborated on the influential irational.org. Her art practice explores techniques used in contemporary marketing to gather and distribute data for the purposes of manipulation and propaganda. Networks of all kinds are “sites” for Baker’s public and private distributed art practice, including radio combined with Internet (Net.radio), mobile phones and SMS messaging, and rail networks. She has presented and exhibited work internationally at various new media and electronic art festivals.

Giving What You Don’t Have is an artistic research project commissioned by the Post-Media Lab, Leuphana University.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

Post Digital Print

The Mutation of Publishing Since 1894

Alessandro Ludovico, 2012

Onamatopee 77

The sticky fingerprints on the black-and-pink 1970s photomechanical typography-style lettered cover of “Post Digital Print” speak volumes about the nature of physical print after the event of digital typography. It is this sense, of print in a state of technical and historical play after the full event of the digital rather than its end or irrelevance, that Alessandro Ludovico is considering history of print publishing here. But why 1894?

Ludovico dates the first announcement of “the death of print” to that year. More than a century later independent bookshops, large bookshop chains, newspapers and magazines are having to compete with Internet-based publishing or be wiped out. It’s not clear whether physical print publishing believes it can survive this encounter with the digital. Ludovico explains how it can and why it is important that it should.

There are three main threads to “Post Digital Print”. The first is a wide-ranging technical history of print, including technologies that were imagined or proposed but never became widespread. The second is a history of radical political and avant-garde historical use, misuse and critique of those technologies. And the third is an analysis of the social and technological networks that distributed the products of the first two. These threads tie together finally in a consideration of the current situation and future prospects of physical print publishing.

The mainstream history of printing goes from movable type through hot metal to photomechanical and finally PostScript-based publishing. This is how books and newspapers have reached millions of people. But not every print production technology has lasted or gained mass adoption. I was surprised to read that Ezra Pound once wrote a poem specifically for Bob Brown’s “Readies” (an imagined 1930s motorized-paper-strip book replacement), and in the first half of the twentieth century newspapers were transmitted by telegraph, telephone and radio ready to be listened to or remotely printed.

The technical failings of dead media become aesthetic affordances in their afterlives. Letterpress embosses the paper it is printed on, lithography suffers misregistration and other artifacts, and newsprint smears and creases. These are now the very qualities people seek from those media. This is different from mere nostalgia, in that it is used to create a contemporary aesthetic, but what of the “Readies” and other book replacements that never were? They are the subconscious or the dreams of print technology, forgotten futures that help to understand the paths that were taken.

Not every print technology was designed to print millions of copies. Spirit duplicators, photocopiers and print-on-demand publishing all allowed democratic access to print for smaller print runs of projects with less mass appeal. Ludovico tracks this thread of print history from mid-twentieth-century science fiction fanzines through the alternative press to the contemporary fanzine scene.

Artists and political groups pushed the technology and aesthetics of each new print technology with pamphlets, unlicensed newspapers, the alternative press, fanzines, and books and journals. Ludovico uses avant-garde and culture jamming artistic publications, from the Dadaists and Futurists to the Yes Men and Decapitator to demonstrate how artists have pushed the form and content of print publications.

Once you have printed a publication you must distribute it. For publications outside of mainstream or official culture, this is a task that has varied in difficulty from inconvenient to deadly. British newspapers had to be licensed (and thereby censored) by the state in the early nineteenth century. Alternative political views were printed in unlicensed newspapers printed by sympathetic printers. These newspapers outsold the official press, and were subject to repression by the state, leading to funds being set up to support the families of arrested printers.

In the Soviet union, Samizdat copies of books were produced with stolen or smuggled paper and borrowed presses. Less dramatically but still outside the mainstream or official culture, the alternative press and fanzine scenes have survived through mail-order print and online catalogues and through conventions. And the Fluxus scene distributed its print products through an international network of distributors.

The “gesture” of publishing, as Ludovico calls it, is an editorial one and without this editorial control the Internet of blogs and social media presents a problem of filtering rather than access. Writing from the web can be taken into print cheaply through print-on-demand, led by the example of James Bridle’s “My Life In Tweets”, 2009. Where an artist led, business followed and there are now many services that will print your social media as books for you.

(What of eBooks? Ludovico considers their technology and its history in depth, but is not hopeful for them. They simulate print ever more closely, confirming Ludovico’s argument that print is the better interface. They have an environmental impact that makes books look more appealing, and suffer all the problems of censorship and technological obsolescence that print now does not.)

In the final chapter (“The Network”) the author enters the story that he is telling. Since the early 1990s Ludovico has produced the magazine “Neural” (I’m a subscriber and I cannot recommend it highly enough), and has been involved in other art projects, events and interventions that have placed him in the thick of the action of the changes in publishing and textual media that have occurred over this period. Rather than affect a false objectivity, Ludovico lets you know where he is coming from and shares the particularities of his broad experience. This lends his conclusions a context and authority that mere theory might lack.

The history and experience that Ludovico lays out leads to the present crisis of print and answers it with the terms that he has established. How can we continue to print physical books? With the kinds of networks that have always propagated and paid for art and for the alternative press. Why should we continue to make them? Because they are better interfaces, archives, and art objects than purely digital objects.

Post-digital print is print with its production and in some ways its very meaning transformed. Print must adopt digital-inspired models of production and distribution to survive. As Ludovico argues it must adopt the digital strategy of the network, in a free and open way. If it does not, we lose a vital part of our collective cultural voice and memory.

“Paper is flesh, screen is metal. … Flesh and metal will thus merge as in a cyberpunk film, hopefully spawning useful new models for carrying and spreading unprecedented amounts of information and culture.” (Post-Digital Print, p117)

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

(Thank you to Freek Lomme of Onomatopee for providing the book interior images.)

Someone said to me ‘To you football is a matter of life or death!’

and I said ‘Listen, it’s more important than that’.

Bill Shankly

Drawing is one of the two oldest purely cultural – in the sense of playful, not directly concerned with keeping body and soul together like cooking or hunting or shelter – activities that comes down to us today directly in the form of artefacts from between 25 – 35 thousand years ago [1] (the other is music [2]). There is no known human culture that has not made representational and other marks with something, on something, for both fun and survival. Furthermore, as Patrick Maynard demonstrates in his steely eyed and magisterial Drawing Distinctions [3], it can be shown to be the practice which more than any other underpins not only all of present day visual culture (including photography, which, following Maynard [4], we read as a species of drawing) but also the technical developments of our advanced industrial age. With satisfying circularity, drawing, a fundamental tool for engineers and architects, scaffolds the level of production which (by guaranteeing surplus product) is the prerequisite for the very existence of our substantial caste of artists and designers, those useless and indispensable dreamers.

Arguably, then, in a perfect world its study might be counted, with literacy and numeracy, as a genuinely key skill to be studied by all. Certainly, perhaps a more realistic demand, it should be a practice both underpinning and overarching any systematic education in art and design. What concrete shape might this take within the Babel of practices which current art education encompasses?

A couple of years ago the two of us, both from a background in digital art/moving image, started teaching on two consecutive courses – a Foundation degree in Digital Art and Design and its top-up, a BA (Hons) degree in Art and Design Practice. Much of the formal documentation of the courses specified the use of particular kinds of software and allegedly real-world reasons for deploying them (many involving the demands of “industry”). From the start we were antagonistic to this approach. We wanted to “artify” the course – introduce as much experimental, speculative, exploratory, pleasurable and downright pointless (in the way that the best art is both pointless and hugely important) activity as possible. We didn’t abandon the idea of teaching design, but we did decide that the core course programme would henceforth be art/design agnostic – it would deal with ways of making and thinking about images (as well as sound, performance, interactions or concepts) that could be used with profit by students moving in either or both or other directions. It would not be training; work would be driven by the imagination and shaped by the ambitions of students. Teachers would introduce new technical processes, but these would be embedded in thematically organised investigations of historic and contemporary precedents. Help with technique or software might be part of what teachers did, but this would be part of an organic investigation/development by student and teacher together. If a teacher knew something they would help; if they didn’t, they might know where to look; if neither knew, they might search together; if the student knew, they could teach other students and the teacher too. In short we identified a peer-learning process as the only sensible approach sufficient for developing the necessary skills, knowledge and flair in a rapidly-developing field.

Moreover we wanted a course that integrated the digital with every other sort of visual (and conceptual, performative and sonic) practice. We were both impatient with the idea that work made using digital tools, or work created within and distributed across a network, was somehow qualitatively different from all that had preceded it (a not uncommon view often allied to a species of digital mysticism). Indeed we realised we both sensed, and gradually came to articulate clearly, that there was a continuum – a chain – from the cave painter to the contemporary artist. Not to say that social and historical concreteness plays no explicatory role, but that there is some still human centre to mark making (and to allied practices – singing, the telling of tales, etc.) which has persisted and will persist and is part of the territory of being human. ’A chain’ is no loose metaphor, but a precise account of the reality. Inspiration and technique pass continuously from generation to generation. And this is cumulative – making much of the past of art available to its future. In a sense the terrain of art accretes, expands, as time passes. Even what is lost to famine or war, proscription, taste and changes in technology leaves traces, the possibility of reconstruction and re-use (and, often most creatively, misuse). This is what we wanted to instil in our students.

Our drawing sessions link to and are inspired by earlier instances of art powered pedagogy that place cross-form conversation at the heart of learning together. Joseph Beuys made drawings throughout his artistic life – often enigmatic constellations of media, concepts, entities, political figurations and material properties. However of particular relevance here are his extended works, Office of the Organization for Direct Democracy by Popular Vote for 100 days at documenta 5, 1972 and Honey Pump in the Workplace for documenta 6 in 1977, in which he demonstrates his expanded notion of art that is exactly congruous with his philosophy of teaching – ‘to reactivate the “life values” through a creative interchange on the basis of equality between teachers and learners.’ [5] Both pieces required the involvement of many people in processes outside of the realms of ordinary action (such as the maintenance of the plastic pipes of the honey pump as it circulated 2 tonnes of honey through the building) in order that they might connect with unfamiliar concepts and experiences. The artworks integrated many different categories of work (some, but not all, associated with art making) including performance and the practice of various disciplines (of dialogue, rhetoric, democratic processes of exchange and decision making). And yet, in an interview with Achille Bonito Oliva, Beuys makes it clear that he has no interest leading audiences towards an “activism devoid of content” [6]. The liberation of humankind through art (Beuys proposes that everyone is an artist and society is to be sculpted by everyone) depends on a more deliberate engagement of individual energies.

Drawing was particularly important to both of us. It was something Ruth had always done from an early age. Collections of drawings made by her between the ages of six and thirteen depict public street scenes of everyday social groupings and activities (a group of kids running with a dog, two mothers with two prams, businessmen waiting for a bus). The figures are too small to carry facial expressions. Nevertheless their interactions, mood, social status and relationships are expressed by their outfits, gaits, their gestures and their proximity to each other and other elements of the scene. Ruth now looks back on these as evidence of an early growing fascination with sociality. Through school she learned that ‘drawing well’ meant producing an image as much like a photograph as one might render. Praise and grades were awarded accordingly. Later, at art school, drawing became a liberating process of discovery. She generated abstract marks, as traces of energies within the body, rather than to create a deliberate composition within a pictorial plane. In this way she produced surfaces such as might be produced by soot covered animals (think monkey, gazelle, seal, tiger, crow) thrown together into a white room. This surface would then serve as a mirror (or crystal ball) from which entities, gestures and forms of light and shadow emerged to be drawn out in further explorations of aspects of her unconscious.

Drawing was something that Michael aspired to. Because he had come to moving image work – to “being an artist” – by a strange route through theatre, maths and music, he had both a fascination with and a terror of drawing. He had been the kid in the class who couldn’t draw, and yet had loved the feeling, the deep engagement with both the act and with what it awoke inside him –his mind’s eye – that it brought. In his moving image work he had attempted to confront this. The inverted commas that came with a certain species of conceptualism were a great help because he could frame himself performatively, comically almost, as an uncertain but oh-so-willing draftsperson, one with no eye or dexterity, a technical schlemiel.

In his secret heart, though, he knew he wanted to do this thing without (or at least largely without) irony.

Arising out of this obsession, in the early years of the new millennium, Michael had launched a little provocation where he challenged digital artists, as they were then still called, to create self-portraits, on the sole condition that this be done using non-digital means, and subsequently to photograph them for display in an online archive. Those who didn’t baulk at the task produced a touching and intriguing panorama, of pen and paint and pencil but also of bathroom tile, egg tempera and iron filings… [7]

As part of a discussion about this Michael had opined on some listserv or other that the barriers between artistic practices were porous and that the true measure of anyone aspiring to be an artist (musician, film maker, poet) was that, if lost in a deep forest or desert isle, with only a rock to make some marks on and another rock to make those marks with, the putative artist would eventually produce something of interest, depth and value.

Early on we introduced chunks of drawing as an occasional workshop – Ruth introduces, and then builds on familiar art school, Bauhaus type exercises that attempt to separate process from outcome-anxiety, allowing students to engage with an inner dialogue about their looking and representation un-disrupted by fears of inadequacy. These include:

drawing without looking at the paper; from memory; without removing pencil from paper; drawing with the “wrong” hand; drawing in five minutes or five seconds; drawing only negative space; having the pencil trace the movement of the eyeball as the drawer observes an object, etc.

Michael felt the centrality of drawing calling him but these sessions still felt like a slightly naughty holiday, an activity that did not necessarily link to his background and formation as an artist. The teacher, like the student, was still exploring.

The big epiphany came with the introduction of a weekly drawing session for all three years of the course. It happened and happens every Monday of term, without fail, and everyone in the room takes part, staff included. As many days as possible where more than one member of staff is present in the room, to make for debate, thus modelling civilised disagreement and forcing students, ultimately, to make up their own minds; there are usually two members of staff and occasionally more present. Each drawing session is led by a student who brings in an object, procedure or puzzle for the rest of us to address.

What happened is that we were rapidly out-Bauhaused by our students. Byzantine sets of instructions for tasks that we as teachers would have rejected out of hand as overly complex, impractical or confusing were carefully explained by students and then carried out by all of us in utter silence.

Half an hour elapses, we place our sets of images on the floor and we process around them all, discussing them. The important thing is that everyone has drawn. Everyone is both vulnerable and admirable. Teachers are not privileged. For students, it is understood that although the process carries course credit, what is being marked eventually is a series of drawings – some “good”, some “bad”, most neither – and that technique – whatever that is – is not the focus. There must be room for play in creative education; hence, for this part of the course, taking part in all of the sessions is enough to secure a pass.

With respect to collective feedback, our experience has been that perceptive kindness predominates. We search for the wonderful things, speculating on why they are wonderful, maybe asking questions of the person who has made this thing, trying to elicit that week’s secret or lesson. The drawings are a pleasure to behold. We have no intention of reproducing any of them here, though many would bear reproduction – we do not want to betray the egalitarian, labouring-together ethos of the thing by selecting outside the sessions and group. We are not sentimentalists – it is precisely because we understand the necessary element of brutality involved in the fair administration of an assessed course that we want to create oases, visions of how things could be other. It is the collective production of shared work that matters – it is not, let us emphasise though, a privileging of “process over production”. The production matters – desperately so. [8]

Over the weeks, our drawings are diverse in category, style, media and technique including: illustrations of the set task, abstractions, naïve figurations, diagrams, signs; some are performances of processes made in pencil, pen, paper, wood, charcoal, paint, collage, arrangements of plastic objects, paper-constructions; they reveal our choices and learning. Some students advance arguments in their drawings either with each other or with their own earlier work. As new tasks are set we each decide in the moment whether we understand the activity we are to involve ourselves with is mundane, ritualistic (perhaps even sacred), mad or wise, pointless or significant – our conclusions shape our drawings. In this way collective drawing has become central to the ethos of our courses as an integrative practice for negotiating a shared studio culture and shaping our learning together, our movement towards collegiality. Doing the drawing means the week has a start to it – we affirm ourselves as folk with a common interest, different but equal. The sessions have helped to provide a social glue, too, across the three years of the course.

There are areas where we as teachers know more than the students; both of us have track records of work in the art world, but the drawing sessions level us all – they enable a mutually supportive but acute look at progress on a common task. Since the drawing started we have also incorporated its lessons to other disciplines; staff and students share their photography work in a more horizontal way than the demands of the course would normally allow. We use new forms of social media, and have Flickr accounts in which all participants are contacts.[9] We comment on and “favourite” each other’s works as equals and collaborators.

Both drawing and photography in these contexts devolve to something similar – filling a blank space by mark making, with valuable, experiential knowledge accrued: repeating processes many times over to find out what constitutes skill and when (often, it turns out, much more often than is often acknowledged) to accept the gifts brought by chance; discovering that the art happens in a social space between the maker, the wider world and the viewer; understanding the work of others because we do it side by side; and, finally, coming to grips with the question of personal style and the diversity of ways of doing things well and meaningfully.

Each week reveals both artistic phylogeny and ontogeny – we solve the problem here and now, as if for the first time ever and this illuminates the historical chain, the intertwining of theory and practice, our mutual dependence, all of us artists and all of us nourished by art too.

—-

Originally written for Drawing Knowledge (2012). Tracey, The Journal of Drawing and Visualisation Research, Loughborough University.

Revised and republished Miller, A & Strong, J. (eds). (2012) Research-Led and Research-Informed Teaching. CREST Publishing.

This is a collection of artworks, texts and resources about freedom and openness in the arts, in the age of the Internet. Freedom to collaborate – to use, modify and redistribute ideas, artworks, experiences, media and tools. Openness to the ideas and contributions of others, and new ways of organising and making decisions together. This collection is intended to inspire, inform and enable people to apply peer-to-peer principles for making things and getting organised together. We hope that all art lovers, makers, thinkers, organisers and strategists will find something for them from this set of imaginative, communitarian and dynamic contemporary practices.

Commissioned and hosted by Arts Council England 2011

Michel Bauwens is one of the foremost thinkers on the peer-to-peer phenomenon. Belgian-born and currently resident in Chiang-Mai, Thailand, he is founder of the Foundation for P2P Alternatives.

It’s a commonplace now that the peer-to-peer movement opens up new ways of creating relating to others. But you’ve explored the implications of P2P in depth, in particular its social and political dimensions. If I understand right, for you the phenomenon represents a new condition of capitalism, and I’m interested in how that new condition impacts on the development of culture – in art and also architecture and urban form.

As a bit of a background, I’d like to look at what you’ve identified as the simultaneous “immanence” and “transcendence” of P2P: it’s interdependent with capital, but also opposed to it through the basic notion of the Commons. Could you elaborate on this?

With immanence, I mean that peer production is currently co-existing within capitalism and is used and beneficial to capital. Contemporary capitalism could not exist without the input of free social cooperation, and creates a surplus of value that capital can monetize and use in its accumulation processes. This is very similar to coloni, early serfdom, being used by the slave-based Roman Empire and elite, and capitalism used by feudal forces to strengthen their own system.

BUT, equally important is that peer production also has within itself elements that are anti-, non- and post-capitalist. Peer production is based on the abundance logic of digital reproduction, and what is abundant lies outside the market mechanism. It is based on free contributions that lie outside of the labour-capital relationship. It creates a commons that is outside commodification and is based on sharing practices that contradict the neoliberal and neoclassical view of human anthropology. Peer production creates use value directly, which can only be partially monetized in its periphery, contradicting the basic mechanism of capitalism, which is production for exchange value.

So, just as serfdom and capitalism before it, it is a new hyperproductive modality of value creation that has the potential of breaking through the limits of capitalism, and can be the seed form of a new civilisational order.

In fact, it is my thesis that it is precisely because it is necessary for the survival of capitalism, that this new modality will be strengthened, giving it the opportunity to move from emergence to parity level, and eventually lead to a phase transition. So, the Commons can be part of a capitalist world order, but it can also be the core of a new political economy, to which market processes are subsumed.

And how do you see this condition – the relationship to capital – coming to a head?

I have a certain idea about the timing of the potential transition. Today, we are clearly at the point of emergence, but also coinciding with a systemic crisis of capitalism and the end of a Kondratieff wave.

There are two possible scenarios in my mind. The first is that capital successfully integrates the main innovations of peer production on its own terms, and makes it the basis of a new wave of growth, say of a green capitalist wave. This would require a successful transition away from neoliberalism, the existence of a strong social movement which can push a new social contract, and an enlightened leadership which can reconfigure capitalism on this new basis. This is what I call the high road. However, given the serious ecological and resource crises, this can at the most last 2-3 decades. At this stage, we will have both a new crisis of capitalism, but also a much stronger social structure oriented around peer production, which will have reached what I call parity level, and can hence be the basis of a potential phase transition.

The other scenario is that the systemic crisis points such as peak oil, resource depletion and climate change are simply too overwhelming, and we get stagnation and regression of the global system. In this scenario, peer-to-peer becomes the method of choice of sustainable local communities and regions, and we have a very long period of transition, akin to the transition at the end of the Roman Empire until the consolidation of feudalism during the first European revolution of 975. This is what I call the low road to peer to peer, because it is much more painful and combines both progress towards p2p modalities but also an accelerating collapse of existing social logics.

That’s a less optimistic scenario… what form of conflict would this involve?

The leading conflict is no longer just between capital and labour over the social surplus, but also between the relatively autonomous peer producing communities and the capital-driven entrepreneurial coalitions that monetize the commons. This has a micro-dimension, but also a macro-dimension in the political struggles between the state, the private sector and civil society.

I see different steps of political maturation of this new sphere of peer power. First, attempts to create networks of sympathetic politicians and policy-makers; then, new types of social and political movements that take up the Commons as their central political issue, and aim for reforms that favour the autonomy of civil society; finally, a transformation of the state towards what I call a Partner State which coincides with a fundamental re-orientation of the political economy and civilization. You will notice that this pretty much coincides with the presumed phases of emergence, parity and phase transition.

Most likely, acute conflict may arise around resource depletion and the protection of these resources through commons-related mechanisms. Survival issues will dictate the fight for the protection of existing commons and the creation of new ones.

You often cite Marx, who of course also wrote at a time of conflict and social change provoked by technological and economic development. Does this tension you’re describing fit in his notion of contradictory forces conflicting – thesis, antithesis, synthesis – in other words, is this a historical materialist process?

I don’t quite use the same language, because I use Marx along with many other sources. I never use Marx exclusively or ideologically, but as part of a panoply of thinkers that can enlighten our understanding. My method is not dialectical but integrative, i.e. I strive to integrate both individual-collective aspects and objective-subjective aspects, and to avoid any reductionist and deterministic interpretations. Though I grant much importance to technological affordances, I do not adhere to technological determinism, and I don’t find that I pay much attention to historical materialism, since I see a feedback loop between culture, human intentionality, and the material basis. Technology has to be imagined before it can be invented.

My optimism is grounded in the hyperproductivity of the new modes of value creation, and on the hope that social movements will emerge to defend and expand them. If that fails to happen, then the current unsustainable infinite growth system will wreak great havoc on the biosphere and humanity.

As you say classical or Marxist economics don’t really suffice to describe the current situation. Is one aspect of this problem that the classical distinction between use and exchange doesn’t fit with a situation in which many of the “uses” are ludic, and have an exchange system built into them? I’m thinking of on-line gaming specifically. But it has always been difficult to place art in this simple use/exchange polarity. Do you see any revisions to that polarity today?

I’m not sure the ludic aspect is crucial, as use value is agnostic to the specific kind of use, just as peer production is agnostic as to the motivation of the contributors. However, our exponential ability to create use value without intervention of the commodity form, with only a linear expansion of the monetization of peer platforms, does create a double crisis of value. On the one hand, capital is valuing the surplus of social value through financial mechanisms, and is not restituting that value to labour, just as proprietary platforms do not pay their value producers; on the other hand, peer producers are producing more and more that can’t be monetized. So we have financial crisis on the one hand, a crisis of accumulation and a crisis of precarity on the other side. This means that the current form of financial capitalism, because of the broken feedback loop between value creation and realization, is no longer an appropriate format.

Regarding your ‘integrative method’, this is a much more sophisticated take on economics that places it in relationship to other, cultural, dimensions of human life. And the imagination is central to it. Given that, do you see any special role for art in this transition?

Art is a precursor of the new form of capitalism, which you could say is based on the generalization of the ‘art form of production’. Artists have always been precarious, and have largely fallen outside of commodification, relying on other forms of funding, but peer production is a very similar form of creation that is now escaping art and becoming the general modality of value creation.

My take is that commodified art has become too narcissistic and self-referential and divorced from social life. I see a new form of participatory art emerging, in which artists engage with communities and their concerns, and explore issues with their added aesthetic concerns. Artists are ideal trans-disciplinary practitioners, who are, just as peer producers, largely concerned with their ‘object’, rather than predisposed to disciplinary limits. As more and more of us have to become ‘generally creative’, artists also have a crucial role as possible mentors in this process. I was recently invited to attend the Article Biennale in Stavanger, Norway, as well as the artist-led herbologies-foraging network in Finland and the Baltics, and this participatory emergence was very much in evidence, it was heartening to see.

We might see as opposed to that sort of grassroots participatory engagement, the entities you refer to as the “netarchies.” Their power lies in the ownership of the platform they exploit for harvesting user-originating information and activities. How hegemonic is this ownership? At what point does it become impossible to create a “counter-Google”?

The hegemony is relative, and is stronger in the sharing economy, where individuals do not connect through collectives and have weak links to each other. The hegemony is much weaker in the true commons-oriented modalities of production, where communities have access to their own collaborative platforms and for-benefit associations maintaining them.

The key terrain of conflict is around the relative autonomy of the community and commons vis a vis for-profit companies. I am in favour of a preferential choice towards entrepreneurial formats which integrate the value system of the commons, rather than profit-maximisation. I’m very inspired by what David de Ugarte calls phyles, i.e. the creation of businesses by the community, in order to make the commons and their attachment to it viable and sustainable over the long run. So, I hope to see a move from the current flock of community-oriented businesses, towards business-enhanced communities. We need corporate entities that are sustainable from the inside out, not just by external regulation from the state, but from their own internal statutes and linkages to commons-oriented value systems.

Counter-googles are always possible, as platforms are always co-dependent on the user communities. If they violate the social contract in a too extreme way, users can either choose different platforms, or find a commons-oriented group that develops an independent alternative, which in turn maintains the pressure on the corporate platforms. I expect Google to be smart enough to avoid this scenario though.

As you’ve said elsewhere, many of these issues are about a new form of governance. Do you see any of this as particularly urban in character — I mean, about organization at the smaller scale, regionally focused, as opposed to at the level of the nation state. Does propinquity matter at all to this — the importance of living together? This seems to relate to a — not a contradiction or tension exactly, but a complication of the P2P notion — that relationships are dispersed, yet a number of the parallels you draw with historical models (for example the Commons) connect with social situations in which people lived very close together. A fairly strong notion in urbanistic thinking is that propinquity is a good thing. In the past that was part of many artistic relationships also: cities as milieux of artistic production/creativity, artists’ colonies; working cheek by jowl with other creative people and breathing the same air. Is this notion in any sense undermined by dispersed networks?

I think we are seeing the endgame of neoliberal material globalization based on cheap energy, and hence a necessary relocalization of production, but at the same time, we have new possibilities for online affinity-based socialization which is coupled with resulting physical interactions and community building. We have a number of trends which weaken the older forms of socialization. The imagined community of the nation-state is weakening both because of the globalized market; the new possibilities for relocalization that the internet offers, which includes a new lease of life to mostly reactionary and more primary ethnic, regional and religious identities; but also because of this important third factor, i.e. socialization through transnational affinity based networks.

What I see are more local value-creation communities, but who are globally linked. And out of that, may come new forms of business organization, which are substantially more community-oriented. I see no contradiction between global open design collaboration, and local production, both will occur simultaneously, so the relocalized reterritorialisation will be accompanied by global tribes organized in ‘phyles.’ I think the various commons based on shared knowledge, code and design, will be part of these new global knowledge networks, but closely linked to relocalized implementations.

One interesting question is what forms of urbanism come out of p2p thinking. The movement is in the process of thinking this through, in fact a definition of p2p urbanism was just published by the “Peer-to-peer Urbanism Task Force” (http://p2pfoundation.net/Peer-to-Peer_Urbanism).

This promotes, in general terms, bottom-up rather than centrally planned cities; small-scale development that involves local inhabitants and crafts; and a merging of technology with practical experience. All resonant in various ways with p2p approaches. But this statement also provokes a few questions: It calls for an urbanism based on science and function; in fact it explicitly promotes a biological paradigm for design. At the risk of over-categorizing, isn’t this a modernist understanding of design — or if not, how is it different? This document also refers to specific schools of urban design: Christopher Alexander, and also New Urbanism. On the side of socio-economics though, New Urbanism has been criticized (for example in David Harvey’s Spaces of Hope); some see it as nostalgic and in the end directed at a narrow segment of the population. Christopher Alexander’s work on urban form has also been criticized as, being based on consensus, restrictive in its own ways. In fact, might not p2p principals call for creation of spaces that allow dissent and even shearing-off from the mainstream? Might there be a contradiction built into trying to accommodate the desires for consensus and for freedom? Contradiction can be a source of vitality, certainly in art; but it can raise some tensions when you get to built form and a shared public realm.

I cannot speak for the bio- or p2p urbanism movement, which is itself a pluralistic movement, but here’s what I know about this ‘friendly’ movement. I would call p2p urbanism not a modernist but a transmodernist movement. It is a critique of both modernist and postmodern approaches in architecture and urbanism; takes critical stock of the relative successes and failings of the New Urbanist school; and then takes a trans-historical approach, i.e. it critically re-integrates the premodern, which it no longer blankly rejects as modernists would do. I don’t think that makes it a nostalgic movement, but rather it simply recognizes that thousands of years of human culture do have something to teach us, and that even as we ‘progressed’, we also lost valuable knowledge. Finally, I think there is a natural affinity between the prematerial and post-material forms of civilization. The accusation of elitism is I think also unwarranted, given what I know of the work of bio-urbanists amongst slumdwelling communities. However, I take your critique of consensus very seriously, without knowing how they answer that. You are right, that is a big danger to guard for, and one needs to strive for a correct balance between agreed-upon frameworks, that are community and consensus-driven, and the need for individual creativity and dissent. Nevertheless, compared to the modernist prescriptions of functional urbanism, I don’t think that danger should be exaggerated.

Following on this track, I’d like to pose another question that relates to living together. The P2P concept depends on the difficulty of controlling the activity of peers on a network: i.e. it’s impossible to lock down the internet. Doesn’t this degree of freedom also eliminate those social controls that might be considered “healthy” – for example, controls over criminal activity. David Harvey (to bring him in again), in his paper “Social Justice, Postmodernism and the City”, lists social controls among several elements of postmodern social justice. When the grand narratives have been replaced by small narratives, there remains a need to limit some freedoms. How does p2p thinking deal with this?

I think we can summarize the evolution of social control in three great historical movements. In premodern times, people lived mostly in holistic local communities, where everyone could see one another, and social control was very strong. At the same time, vis a vis more far-away institutions, such as for example the monarchy, or the feudal lord, or say in more impersonal communities such as large cities, compliance was often a function of fear of punishment. With modernity, we have a loss of the social control through the local community, but a heightened sense of self through guilt, combined with the fine-grained social control obtained through mass institutions, described for example by Michel Foucault. The civility obtained through the socialization of the imagined community that was the nation state, and the educational and media at its disposal, also contributed to social control and training for civil behaviour.

My feeling about peer-to-peer networks is that they bring a new form of very real socialization through value affinity, and hence, a new form of denser social control in those specific online communities which also usually have face-to-face socialities associated with them. But this depends on whether the community has a real value affinity and a common project, in which case I think social control is ‘high’, because of the contributory meritocracy that determines social standing. On the contrary, in the looser form of sharing communities, say YouTube comments for example, we get the type of social behaviour that comes from anonymity and not really being seen.

So the key challenge is to create real communities and real socialization. Peer to peer infrastructures are often holoptical, i.e. there is a rather complete record of behaviour and contributions over time, and hence, a record of one’s personality and behaviour. This gives a bonus to ‘good ethical behaviour’ and attaches a higher price to ‘evil’. On the other hand, in the looser communities, subject to more indiscriminate swarming dynamics, negative social behaviour is more likely to occur.

A key difference between contemporary commons and those of the past is that the new ones are immaterial and global. The model for P2P exchange seems to be of autonomous agents relating and forming new communities not based on membership in an originary cultural group. Given a global distribution, how do local, cultural factors play into the model of globalized distributed networks? How does P2P accommodate cultural specificity, especially specificity with deep historical roots; and how does that accommodate the development of new culture, art?

In my view, the digital commons reconfigure both the local and the global. I think we can see at least three levels, i.e. a local level, where local commons are created to sustain local communities, see for example the flowering of neighbourhood sharing systems; then there are global discourse communities, but they are constrained by language; so rather than national divisions, which still exist but erode somewhat as a limitation for discourse exchange, there is a new para-global level around shared language. At each level though, cultural difference has to be negotiated and taking into account. If there is no specific effort at diversity and inclusion, then affinity-based communities reproduce existing hierarchies. For example, the free software world is still dominated by white males. Without specific efforts to make a dominant culture, which has exclusionary effects, adaptive to inclusion, deeper participation is effectively discouraged. Of course, as the dominant culture may not be sufficiently sensitive, it is still incumbent on minoritarian cultures to make their voice and annoyances heard. Obviously, each culture will have to go through an effort to make their culture ‘available’ through the networks, but I think the specific role of artists, now operating more collectively and collaboratively than before, is to experiment with new aesthetic languages, so that non-conceptual truths can be communicated.

The innovation I see as most important though is in terms of the globa-local, i.e. a relocalization of production, but within the context of global open design and knowledge communities, probably based on language. I also see a distinct possibility for a new form of global organization, i.e. the phyle I mentioned earlier, as fictionalized in Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age and operationalized by lasindias.net. These are transnational value communities that created enterprises to sustain their livelihoods.

I see the key challenge, not just to develop ‘relationality’ between individuals, as social networks are doing very well, but to develop new types of community, such as the phyle, which are not just loose networks, but answer the key question of sustainability and solidarity.