Featured Image: Stock photography from Google Image search “happy creative tech startup”

Neoliberal Lulz: Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion, and Jennifer Lyn Morone.

Showed at the Carroll/Fletcher Gallery 12 February – 2 April 2016.

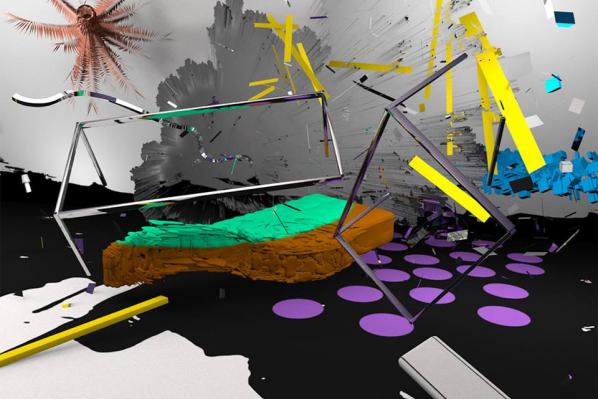

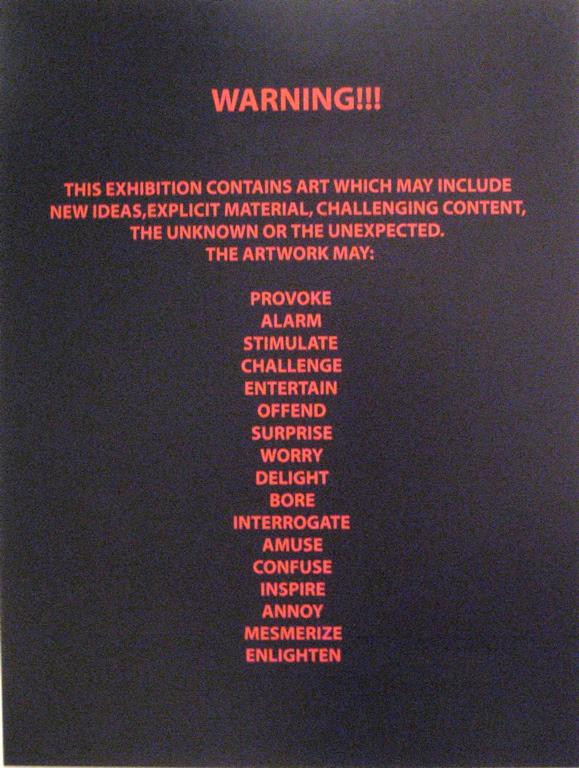

Neoliberal Lulz asserts to have born witness, arm-in-arm with rest of us, to an unprecedented shift in the volatility and increasing speculative power of financial markets and the dissolution of value indexing to physical commodities. This relationship has been made particularly palpable in the realization that investment banks and corporations hold a tremendous sway (perhaps even tremendous to an unknowable degree) over our lives. The four artist/groups brought together make work as a way of trying to bring this dynamic into knowing.

Neoliberal Lulz is not so much about this relationship, or the realization of this relationship, between market forces and lived experience. It’s more accurate to say that the exhibition and the artworks contained within it rather serve as a populist blueprint for how individuals can talk to the market. If political economies speak in the limited language of supply and demand, then how can we make ourselves heard?

New media is a particularly good way of addressing this question because of the way hardware and software must constantly negotiate the terms of inter-communication. The success of media is dependent on this trafficking in translations, between file formats, online and IRL, technical apparatuses, outdated and current softwares. So when artists like Constant Dullaart, Femke Herregraven, Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion, and Jennifer Lyn Morone make themselves “corporate,” mimicking the neoliberal virus, this move feels right at home with the kinds of techno-alchemist work being displayed.

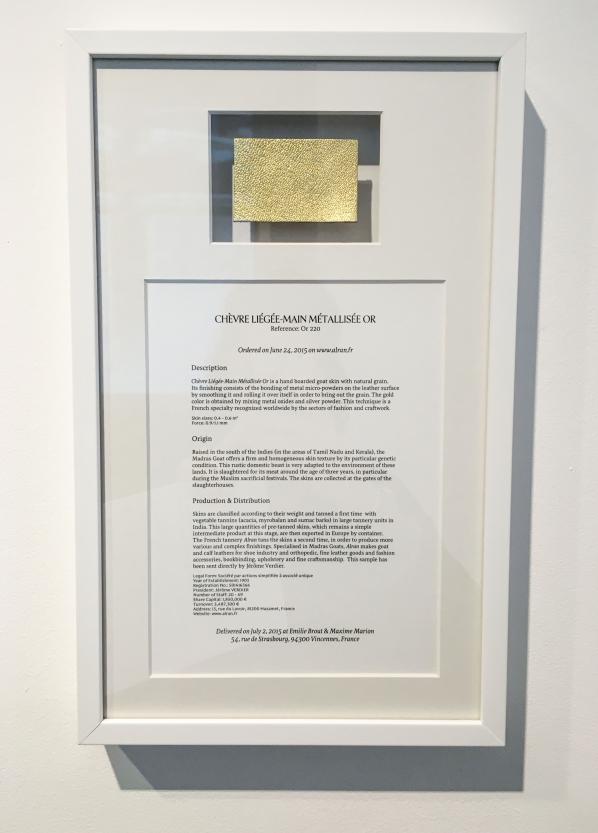

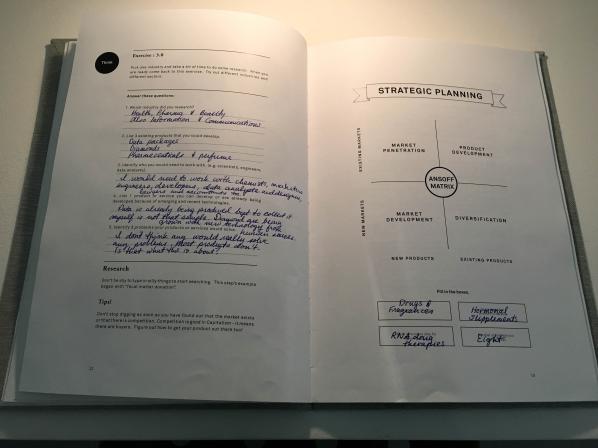

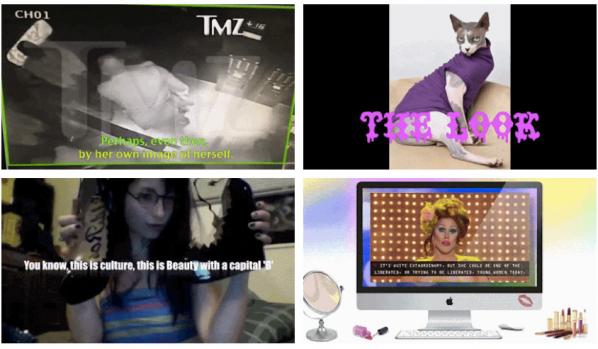

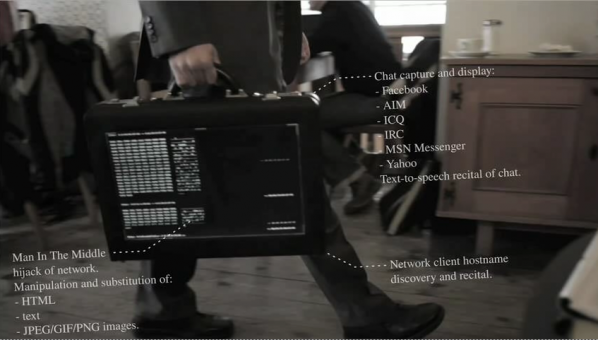

Femke Herregraven makes the mystifying lifespan of high frequency trading material, which feels a lot like spinning straw into gold (or perhaps the other way around). Her works rehearse this slippery, ambivalent relationship between value and objects, indexes and standards. In this way Herregraven’s works ground the exhibition in a similar way as does Constant Dullaart’s Most likely involved in sales of intrusive privacy breaching software and hardware solutions to oppressive governments during so called Arab Spring: by memorliaizing in cold, clunky materiality the “immaterial” processes that are active under the banner of neoliberalism everyday. Three of the four artists on display have incorporated—Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc, Untitled SAS (that’s Émilie Brought & Maxime Marion), and DullTech™ (Constant Dullaart). Between these companies the process of how to become a company is cracked open, revealing how sophomorically simple and complicated the process is, how much paper detritus and nondescript stuff is secreted as byproduct. Constant Dullaart here adds a lesson on the aesthetics of startups with an entire room dedicated to the oddly-familiar B-roll shots of airplanes cut with inspirational platitudes. Jennifer Lyn Morone adopts the the aesthetics of a kind of good life marketing that is gender-targeted, and operates by corroding away what’s already there (mental health, well-being) to make its own market gap.

But I tell you this: the best part of the exhibition isn’t on display. Ask the front desk about buying shares of either Untitled SAS or Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. This is the heart of the exhibition, and it’s either lamentably sidelined or a brilliantly premeditated that just inquiring about the purchase can reveal so many gaps and uncertainties.

When I visited the exhibition, gallery attendants very kindly filled me in on the bold point details of buying shares, to the best of their ability. They explained that Unititled SAS shares sold for €30.00, with a €25.00 admin fee that went straight to Émilie and Maxime. It is not split with the gallery, as often the the sales of an art object are. Was the gallery entitled to any part of the sale of shares of Untitled SAS? Sort of: fifty-percent went to the French government, twenty-five percent went to Émilie and Maxime, and half of the remaining twenty-five percent went to the gallery. Did a new contract have to be drawn up to negotiate the profit negotiations between the gallery and artists who had incorporated some capacity? No, the normal consignment contracts were used (they did not share what the terms of these contracts are; I did not inquire).

What about shares of Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc.— how much did they cost? This was a decidedly trickier question, with nationality and class-based restrictions and allowances. The general gist was that since Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. is registered in the U.S.A., that American citizens are subject to tax; English citizens are not. For English citizens there are also different price points and clauses for lower-income prospective investors. This does not apply to U.S. citizens, who are required to prove salary requirements before purchase can be approved.

Had anyone bought any shares yet, for either company? No.

Eventually, the attendants printed me a Jennifer Lyn Morone™ Inc. Instructions for Prospective Investors document: four-pages single-sided, unceremoniously stapled together. For those unfamiliar with this kind of legalese, it’s a bizarre artifact from another planet. Everyone should ask for a copy.

The title Neoliberal Lulz might tip its hat to the tradition of online trolls and their persistent, agnostic vitriol, but the exhibition itself feels like it sets out some very real stakes. This is a good thing, because an exhibition interrogating the asymmetrical relations of production and profit taking place at a prominent art gallery in Fitrovia (a borough in itself that is paradigmatic of these inequities) could have really been smug, smarmy, shit. The hypocrisy of an exhibition that singularly railed against the unmitigated growth of big business while standing amongst its spoils would be too much. But Neoliberal Lulz is not this: it is far more nuanced in its message, far more unclear on its value judgments. As an art exhibition Neoliberal Lulz did well to espouse the artist-as-researcher model. It helps make sure that the exhibition has legs outside of the exhibition space. The fact that most of these artworks have a life outside of the domain of art, circulating within the very thing they’re critiquing, legitimates their output. The other thing that Neoliberal Lulz does well is not to dwell on the narrative of the disenfranchised. I don’t say this because it’s not important but rather because it just simply wouldn’t read.

Neoliberal Lulz feels like a prompt that comes at a timely moment, slotting in to conversations like this, this, and this. It criticizes at the same time as it offers options, which seems like a rare combination these days. “What is to become of the future for young artists?”–the people wail, lamenting that much of the young, creative elite inevitably ends up siphoned off into the tech startup culture. Neoliberal Lulz seems to say this doesn’t have to be a bad thing, and I’m inclined to agree. All’s not lost when artists adopt an if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em ethos, particularly when they do so with a critical bent. Deeply sardonic and ruthlessly interrogative, Neoliberal Lulz is a successful venture into addressing the malleability of contemporary political economies to more progressive ends.

Carroll/Fletcher Gallery

56-57 Eastcastle St.

London W1W 8EQ

The Wrong Biennial, organized by David Quiles Guilló, is possibly the largest internet-based exhibition to date. With a flexible roster of 90 curators and 1100+ artists, this estimation of the exhibition may just be correct. However, as with any project of such a size, The Wrong may serve to be, as well as an overwhelming survey of contemporary media art, it could also be a mirror of individual critics and curators’ desires. But what it also represents for me is a grand bazaar of the current state of media art, and what I would like to discuss, along with a couple of the ‘pavilions’, which are the meta-effects of the exhibition.

But when I talk about The Wrong being a mirror for the hopes and desires of the curators and critics is that the reviews to date are as broad as the exhibition, and sometimes shaped to that critic’s interests or familiar territory. One critic recuses himself as more of a brick and mortar type, looks at a couple pavilions, and then addresses Lorna Mills’ post-internet satire of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing as a possible move to currently familiar territory.Conversely, the business magazine Fast Company, asks if The Wrong will finally allow digital art to sell. A virtual worlds blog hails the FrancoGrid SecondLife-like pavilion as yet another chance for “the art world to finally see the brilliant work happening inside virtual worlds”.

On Facebook, a thread with post-internet & glitch artists muse as to whether the non-institutional nature of The Wrong might constitute some dilution of the work in galleries. The views of The Wrong seem to be, in light of its sheer scope, more a reflection of what the critic finds familiar than tackling the overall project.

These are cursory cross-sections of the discussions happening online. From one review to the next, as important as the art and the artists, is the fact that Guilló has undeniably blown open a gigantic conversation about the nature of electronic art.The Wrong Biennial, regardless of its composition, structure, etc., has proven and a disruptive moment in this moment of hyperprofessionalized media art practice, and has created an online/offline archipelago larger than any festival, such as Ars Electronica, ISEA or Transmediale. And it’s free. But with the size and open nature of such an event in light of professional pressures from student loans to art fairs one asks, what good is being exceptional when you open the gates for undifferentiated curatorial practice? But conversely, art critic Jerry Saltz mentioned that the work he saw after the last art crash in the late 2000’s was more and better after the flattening effect of the crash. Could the rhizomatic effect of the bazaaring of net art created by the sheer scope of The Wrong have created one of the greatest analogies for the current explosion of media art today by giving a lot of it to the online public and creating an agora for discussion as well?

While the effects of The Wrong I am explaining may seem like the title of the Performa ’09 biennial in saying, “Everywhere, All at Once”, Guilló took a flexible, but very rigorous approach to constructing the exhibition. In the beginning, Guillósought funding for the project on Indiegogo, and set up bienniale and curator group pages on Facebook, as well as an extensive exhibition catalogue website. These set a framework for the numerous on/offline “pavilions”, all linked through the biennial online sites. And, periodically, there are docented online “tours” of the Biennial every week or so that attempt to make sense of the content onslaught that The Wrong presents. In a way, this biennial uses the aesthetics of the Long Tail to situate itself somewhere between “snack culture” (Wired, 2007) and recursive self-curation/the “curated life” in its structure to mirror the current cultural sociological terrain. In other words, what is as impressive regarding The Wrong is its structure as much as its content.

In allowing myself to peer into the abyssal mirror of content implicit in The Wrong and see my own reflection in it, I see a project I did in 1998. I curated a show called Through the Looking Glass for the Beachwood Center for the Arts in Cleveland, a 3000+ sq. foot space. More or less, there were a number of kindly locals who were curious about digital art. For this show, I got 80+ physical artists and 40 or more online artists to show the breadth of the current scene from every continent (there was even an Antarctican photo installation…) Artists included Michael Rees, Scott Draves, Helene Black, RTMark, and many more. The show included a physical space as well as the show website (http://voyd.com/ttlg/) which also included a number of other artists. The exhibition was promoted/discussed on sites like The Thing and Rhizome, and was documented in Christiane Paul’s New Media in the White Cube and Beyond, (UC Press, 2008), somewhat mirroring Guilló’s discursive hydra. The importance was that it got a regional and international dialogue going about the state of media art at the time, much like The Wrong, but only at a fraction of the latter’s scale.

Guilló’s project transcended the museum, as in conversation online he was enroute to one of the museums he has spoken on the subject, including sites Europe, North America (SAIC) and others. In this regard, the reach of the project, while theoretically only possible as something like Ars Electronica’s Net.Condition or the Walker’s Art Entertainment Network in the late 90’s, has engaged the many social media layers from Facebook, Twitter, as well as net.distribution and reached a much wider audience. In this way, I feel Guilló has sidestepped the institution to make an exhibition that reflects the cultural terrain and social practices of its milieu – the Internet. In some ways, I feel that The Wrong could be the first true net.biennial.

With nearly a hundred “pavilions” to view, writing on any one cannot address the scope and structure of The Wrong. Perhaps I am less enthralled with ones that deal with individual artists, moreso with thematic pavilions, and more with the open call ones, as they create a generative basis for expansion of the biennial itself, creating more diversity within it.

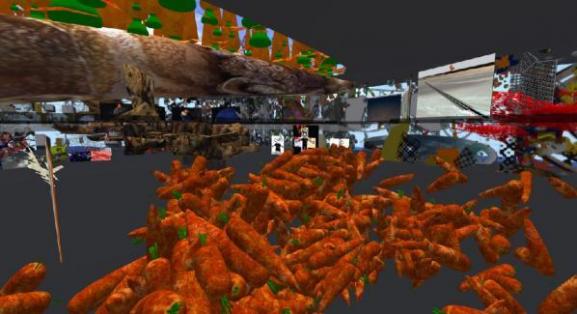

One of the open calls that I liked well enough to volunteer for was Brazilian Gabriel Menotti’s Approximately 800 cm³ of PLA, which was an open, print-til-we-run-out, Fluxus-reminiscent, “give us a file and we’ll print it exhibition”. The resultant models were put on display at Baile, in Vitoria, Brazil, and included pieces from veteran Chicago 3D print artists Tom Burtonwood and Taylor Hokanson. Another pavilion of interest (again using the mirror metaphor, as I have been known to do work in virtual worlds) is that of the Wronggrid Pavilion in FrancoGrid, a Francophonic OpenSim (read: open source Second Life) that hosted a 6-month residency with sixteen artists. The WrongGrid Pavilion has generated a great deal of content, especially from Jeannot GrandLapin (Frère Reinert?) as the big avatar rabbit GrandLapin, and another Chicagoan, Paul Hertz. The WrongGrid virtual vernissage was one of the more memorable events in The Wrong as it gave one of the few opportunities for people to meet in the virtual across continents and share in the work in real time. But these are only two of nearly 90 sites that constitute this massive undertaking.

David Quiles Guilló has created a juggernaut – significant enough to get the #3 nod from Hyperallergic for top shows in 2015. From its size and scope, it represents a breadth of artists and themes that shows a fantastic cross-section of the current electronic media art ecosystem. In addition, The Wrong engages avant practices of open curation, nested participation, and relational organization while challenging the necessity of institutions and art fairs. While The Wrong may be as hard as Benjamin’s Arcades Project to get through, most sites give rich experiences, and some give empty links. What is important about The Wrong Bienniale is that it appears to be one of the few projects that is a true net.biennial in terms that it is about the net, how its links with the physical, and how it refers to projects like the Fluxus-inspired Eternal Network that explore how we create through social and technological networks. The Wrong Bienniale is a disruptive site of cultural engagement in a social milieu complaining of malaise and cynicism. It’s time to consider what media art is; how our communities interact; how we operate as a community; and what it means to be a media artist in a mediated culture.

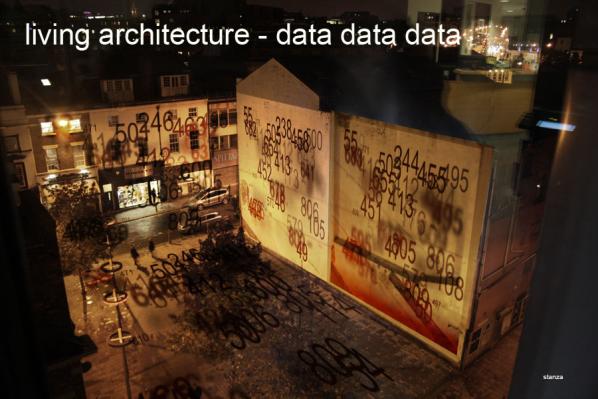

Stanza is an internationally recognised artist who has been exhibiting worldwide since 1984. He has won so many prizes you’d have trouble fitting them all on one mantlepiece. He has exhibited over fifty exhibitions globally and is an expert in arts technology, CCTV, online networks, touch screens, environmental sensors, and interaction. His artworks examine artistic and technical perspectives, within the contexts of architecture, data spaces and online environments.

Recurring themes throughout his career include the urban landscape, surveillance culture, privacy and alienation in the city. Stanza is interested in the patterns we leave behind, and real time networked events, that are usually re-imagined and sourced for information. He uses multiple new technologies so to create distances between real time, multi point perspectives that emphasis a new visual space. The purpose of this is to communicate feelings and emotions that we encounter daily which impact on our lives and which are outside our control.

Much of his work has centered on the idea of the city as a display system and various projects have been made using live data, the use of live data in architectural space, and how it can be made into meaningful representations. See Publicity, Robotica, Sensity, as well as a whole series of work manipulating real time CCTV data to making artworks with them: See, Velocity, Authenticity, Urban Generation. These works reform the data, work with the idea of bringing data from outside into the inside, and then present it back out again in open ended systems where the public is often engaged in or directly embedded in the artwork. Interactive and visually appealing, his style also maintains the substantive power through multi-facetted content.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Stanza: I don’t really get inspiration from the “who” question, I prefer the “what” and “why” questions. As a professional artist I look at loads of art so to understand what art is and can be, and it’s always an ever changing and fluid response. I also spend a lot of time ignoring stuff and material; (focused ignoring) because it has become harder and harder to see though the fog; the noise of it all. Maybe it’s better to think of a working model for inspiration, Andy Warhol had one. Just make the work. That’s what I do. I am not a part time artist in academia or an artist with another job, I’ve done this for the last thirty years, inspired by and in response to the world around me.

This dogmatic commitment to my work comes from my believes that the system you have to trust and invest in yourself. Inspiration, quite literally is everything all around you all at once, all at the same time, moment by moment. This is what inspires my work and it influences the creation of real time information flows, and works in parallel realities. It allows me to stand back at a distance and work with complex data sets while at the same time making meaning from them. Forming data into a shape, because this confluence might inspire a repositioning of thought and values while at the same time unlocking a hidden meaning to enable the viewer to feel and experience something new or to do something creative with the results.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

S: There’s a saying be careful what you wish for. If one reverses this then it could be wish for what you want and need. Influence is problematic because it’s both negative and positive. The idea of influence seems causal, but my own practise isn’t based on influence but in research into certain themes. This enables me to get into both sides of particular questions or debate, so to frame the work I make. Works like these have been inspired by this focus…

The Singing Trees, focus in the invisible things and the environment http://stanza.co.uk/tree/index.html

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

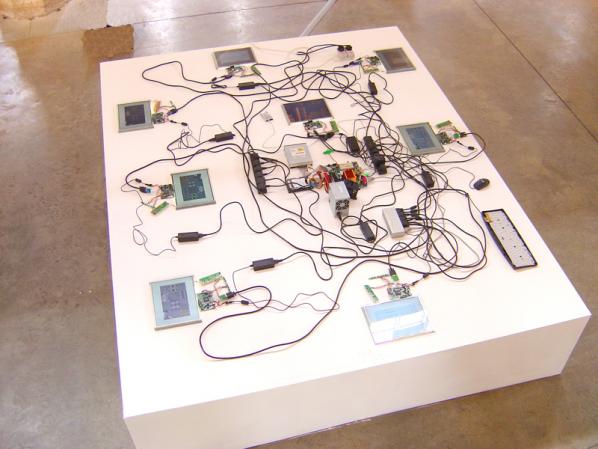

S: I have been researching smart cites, urbanisn, and have collected ‘big data’ since 2004. I have been building my own wireless sensor network. This eventually manifested itself in an artwork called Capacities in 2010 which then influenced all the others in the series until it now has this form.

Capacities: Life In The Emergent City, captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork

http://stanza.co.uk/capacities/index.html

Which led to…

The Nemesis Machine- From Metropolis to Megalopolis to Ecumenopolis.

“A Mini, Mechanical Metropolis Runs On Real-Time Urban Data. The artwork captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork. The artwork explores new ways of thinking about life, emergence and interaction within public space. The project uses environmental monitoring technologies and security based technologies, to question audiences’ experiences of real time events and create visualizations of life as it unfolds. The installation goes beyond simple single user interaction to monitor and survey in real time the whole city and entirely represent the complexities of the real time city as a shifting morphing complex system.

The data and their interactions – that is, the events occurring in the environment that surrounds and envelops the installation – are translated into the force that brings the electronic city to life by causing movement and change – that is, new events and actions – to occur. In this way the city performs itself in real time through its physical avatar or electronic double: The city performs itself through an-other city. Cause and effect become apparent in a discreet, intuitive manner, when certain events that occur in the real city cause certain other events to occur in its completely different, but seamlessly incorporated, double. The avatar city is not only controlled by the real city in terms of its function and operation, but also utterly dependent upon it for its existence.”

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

S: It’s the museum I would like to change or engage with. It seems that anything and everything will end up in the museum. We have become the museum. We are the sum of our collections catalogs and archives. Since the current trend is for public engagement we will see a mix of these new technologies aiding and abetting this and various dialogues.

Therefore these questions need to be raised more vocally. How do visitors interact with each other and artworks? How do visitors behave in public space and what patterns or communities do they form. Can these outputs reshape our experience of public space and the art?

So, new immersive technologies could be used to investigate how visitors interact with art works, with each other and what impact their experiences have in forming new user interactions within public space. This space could be made more social and lead to new real time artworks based on visitor interaction and new visualizations of the gallery space based on gathered data.

Artists used to occupy specific issues but now there aren’t many topics artists haven’t engaged in or reached out to. The issues that will resonate will be the ones closest to the issue of the day…. and, they will be economics, the environment and migration. Because of this I would like to less focus on public engagement spectacle or entertainment and more on the quality and public engagement rooted in intellectual rigour.

Technology affords new ways of working with audiences and curators as participants in artworks. The concept of the exhibition as an active site for experimentation and collaboration between curators, artists and audiences prefigures a general cultural movement towards the centrality of experience and away from the reification of the object.

However, how audience activities and movements can be used as the subject of new artwork as well as modify engagement with existing collections is a cultural and technological challenge.

SeePublic Domain: You Are My Property, My Data, My Art, My Love.

The Public Domain Series involves using live CCTV systems that are already installed then using these cameras to enhance gallery space and the audiences experience of the gallery. http://stanza.co.uk/public_domain_outside/index.html

Visitors to a Gallery – referential self, embedded. Stanza uses a live CCTV system inside an art gallery to create a responsive mediated architecture. Anyone in any of the galleries and all spaces in the building can appear inside the artwork at any time.

http://stanza.co.uk/cctv_web/index.html

The social challenge within urban space is one I like to play with. In The Binary Graffiti Club, is a project I set up to try and work in this area. The Binary Graffiti Club are invited members of the public at each location for each event; they are given the hoodie to keep as thanks for their participation and contribution. The Binary Graffiti Club set off across the city and create artworks.

http://stanza.co.uk/binary_club/index.html

“Youths dressed in black hoodies swarmed the historic city streets of Lincoln during Frequency Festival 2013, their backs emblazoned with bold white digits, the zeros and ones. Their ominous presence was marked with a series of binary code graff-tags on official buildings throughout the city; messages of insurrection for a digital cult now active among us or analogue reminders of the digital soup of signals we wade through on a daily basis? There’s an engaging playfulness and an aesthetic pleasure to Stanza’s work that pays rewards on deeper investigation. His urban interventions remind us of the invisible occupation of the cyberspace around us and encourages us to ask whose hand manipulates these systems of control.” Barry Hale, Festival Co-Director of Frequency Festival 2013: Stanza: Timescapes/Binary Graffiti Club.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

The invention of the toothpaste tube caused a revolution in painting.

The greatest discovery of the age was that the world is full of atoms.

Doing many small things instead one on big thing.

We seam to victimise out children we give them ASBO’S and anti social behaviour orders. For a while I wanted one. They actually give you a certificate like rockers, mods punks etc. The hoodie is a symbol of youth culture as well as being anti social. My new artwork the Reader and the idea of reading books and being anti-social led to this project.

The Reader is a large six foot sculpture of the artist Stanza wearing a hoodie reading a book. The artwork is a metaphor for the engagement of reading in the digital age. The sculpture acts as a focal point for community and public engagement and has taken over one year to make and design; it has been commissioned to act as a focal point for the identity of the library. The reader reads all the books published since 1953 inside a data body sculpture. http://stanza.co.uk/TheReader_web/

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and or social change?

S: Make work, make more work, and remember nothing lasts forever except true love.

Re: Art, Study it

Re: Technology. Learn it

Re: Social change . Be part of it.

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

Yes the Books…

The Bible The Quran And The Torah.

Because…they are the most influential books ever written and have guided the lives of billions so it’s a good idea to have had a read… at least “view” them.

See…

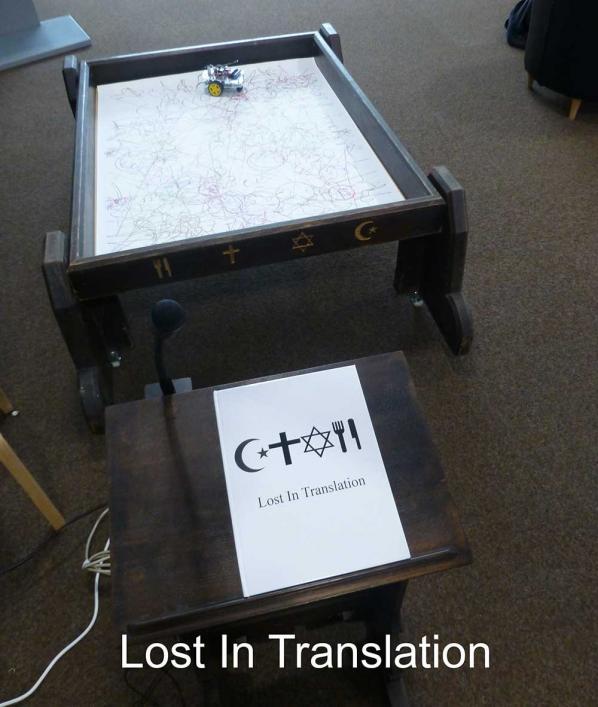

Lost in Translation. This custom made robot responds to a series of texts and makes drawings unique to each reader. The work questions not only the meaning and interpretation of text but just who controls our understanding of the outputs and indeed what is Lost In Translation. This is a very playful user friendly work and actively engages the audience not only to think about the text but the meaning of how automation and networked technology is changing the control of understanding. http://stanza.co.uk/lost_in_translation/

Thank you…

Featured image: Leo Selvaggio’s Urme Surveillance.

“(I loved the FUSE opening at the Vancouver Gallery)

You couldn’t tell the ISEA work from the art!”

– paraphrased from a tweet noted by Paul Catanese

That which disrupts is fated to make its own niche, called a foothold.

I’m late, with few excuses other than adjusting to my new role at American University Sharjah and needing to really process this event, as it presented challenges, old and new. The reflection is particularly useful in that the scope of Kate Armstrong, Malcolm Levy, et al’s vision this year in Vancouver was so grand that it is near impossible to write a fully inclusive perspective on the festival. Therefore, I will limit myself to some specific ruminations, cover highlights, and draw an epistemic vector moving forward.

What ‘clicked’ for me through the aforementioned tweet was that not only has technological art been accepted by a mainstream vis-à-vis the FUSE exhibition, denoting an aesthetic sophistication, but also an alignment with an more mainstream art-historical sensibility. Perhaps this comes from awareness of artists like the Postinternets, of which Levy is considered; have for the conventional art world while exploring technological forms. This has not always been the case, but perhaps artists like Levy, Olson, Gannis and others have answered the gauntlet thrown by Claire Bishop in the 50th Anniversary issue of Artforum, where Bishop called for the disavowl of digital art, and by association, electronic art. This results in a disruption piercing the perceived ‘wall’ between technological arts and art history/the ‘art world’. As I mentioned, because of the size, I will limit myself to highlights consisting of notable exhibitions, keynotes, and selected works of art.

Vancouver is a city steeped in media art history. As Sara Diamond laid out so well in her keynote, Vancouver media arts encompassed feminism, alteriority, and telematics. Part of my familiarity with that history includes the activities at artist-run spaces like Western Front and Open Space, with artist like Hank Bull, Robert Adrian, Bill Bartlett, Robin Oppenheim and others trailblazing networked art through teletype, slow scan television, and satellite performance. ISEA showed that this tradition is alive and well in the Canadian West. One other remarkable Canadian (perhaps one could say American-Canadian) keynote was Brian Massumi’s talk on Affect. Brian mentioned that despite the fact that he has written extensively about topics including affect, he felt that he had not addressed the topic directly to the point that he was satisfied. Massumi integrated ideas echoing from Parables for the Virtual to today in his signature propositional style, and it is my hope that I will see this in print.

The first major site to visit was the Quoting the Quotidian opening exhibition at Wil Aballe Art Projects (WAAP). The concept was the celebration of the everyday, the found, and the appropriated. Of course, a quick go-to would be Marisa Olson’s Time Capsule series of gold-painted media artifacts. Of the artists, the most lingering was Nicolas Sassoon’s moire GIF work, of which I was somewhat familiar. The ongoing point of interest I have with the GIF in the gallery is that its venerable age has elevated the format to near-filmic status. The gallery was small, which was surprising for an opening event, and was attended by most of the ISEA board, including Peter Anders, Win Van der Plas, and Paul Catanese…

Also early in the festival, I attended AM/CB’s Hakanai installation/performance. Hakanai is a cubic projection mapping work that responds to the dancer in using conceits of draped grids, Ikeda-like geometric glitches. While the performance itself was amazing at a technical and aesthetic level, I felt that the piece itself was constrained by its technical conceits, as I never felt that there was a transcendent moment in which I felt like the techne ‘disappeared’ despite the magic that was happening. For all the situations proffered, wind, rain, etc. I never stopped thinking of how they did that, regardless of how virtuosic the work was.

Probably the most impressive feat pulled off by the ISEA organizing group was the FUSE exhibition. This for me was likely the most impressive event, held at the prestigious Vancouver Gallery. The gala was well attended, and I was very surprised to be the subject of Facebook paparazzi of which I had no acquaintance (red carpet, indeed…). The event spanned the second floor rotunda onto the penthouse-like third floor. One of the key aspects of the show was Armstrong and Levy’s concept of dealing with electronic art and materialism, and emergent canonical forms like Glitch, with representatives of the form being works by Philip Galanter and Jon Cates. Levy’s idea for tying the exhibition to emerging media art histories clearly refers to the rich art historical space in Vancouver, as echoed by the opening gala at VIVO and trips to the legendary Western Front artist-run space. Admitting a personal bias, it was good to see Scott Kildall’s EquityBot ultra-slick documentary (corporate?) display describing his experiments using bots to execute automatic trading on the stock market based on affective reactions in the Twitterverse. Also surprising was Paula Gaetano Adi and Gustavo Crembil’s TZ’IJK, a blind, deaf, and speechless robot made from mud.

At the Vancouver Gallery, there were a number of great works, foremost amongst them were Erin Manning and Nathaniel Stern’s The Smell of Red and Judith Doyle’s Crow Panel. Red was an intense installation that expanded on the ideas of embodied knowledge of the Senselab group at Concordia University, in which there was a sandy beach enervated with cinnamon. Rising above in areas were vortex chambers designed by his working group at UW Milwaukee that simulated dust devils over the cinnamon landscape. In the center, there were edibles that you had to enter into the installation, and I would up smelling like cinnamon for two days. Doyle’s piece, Crow Panel was a playful take on the Kinect point cloud genre in which apparitions of people, birds and the forest floor are mixed with live depth images of a rough doppelganger of data interacted with us as we entered the structured light field. However it was not so directly representative as other pieces using the technology, and it remained lyrical and fun.

After the Vancouver Gallery exhibition, I decided to forego the Mutek event and venture out to the LoCoMoTo happening, entitled Oscillations, held in Charleson Park. It consisted of several performance/sound/projection pieces in natural settings by Merlyn Chipman, Jeremy Inkel, Wynne Palmer, Rob Scharein, Laura Lee Coles, and many others that integrate themselves into natural settings. Of note was Send and Receive, by Mirae Rosner and prOphecy sun, an idiosyncratic performance in which they worked with huge siver inflatable forms, reminding me of giant silver tailed lamas of Indian folklore against the Vancouver skyline, creating a surreal mise en scene.

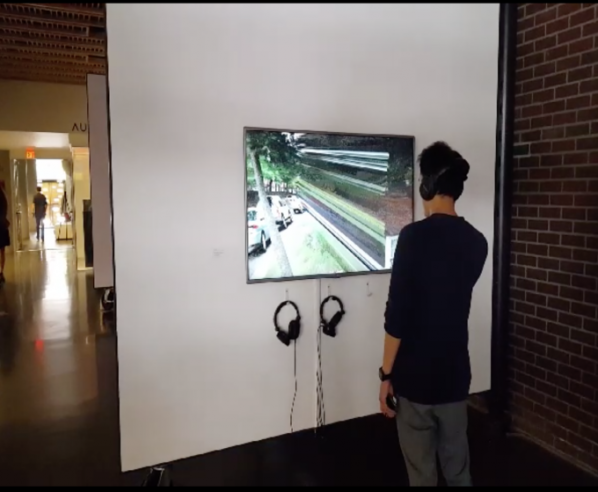

Back on the SFU campus, my favorite piece in the festival was Polak and Van Bekkum’s piece, The Mailman’s Bag. This impressive piece is constructed from several directions; a GPS-enabled sound recorder is placed in a mailman’s bag, giving the bag the capacity of hearing. The GPS data is then used to drive a Google Street View animation that extrudes into pseudo-3D neighborhoods with the sound of the bag in the background. The neighborhoods morph and undulate as the eye moves through the space, creating an effect somewhere between a cheery Inception, Dark City, or Scanner Darkly. The Baudrillardian hyperreal becomes evident here, and becomes disturbing in its distortion of the mediated real overlaid upon surveilling data politics.

The main question that I have been pondering in writing this review is based on the beginning quote – what happens when what has been considered genre art becomes transparent? This has been a conversation that has been happening since the inclusion of New Media in numerous major exhibitions since the 1990’s. Although we can go back at least to Dada to argue that technologically-enabled work has been making incursions into the art-historical dialogue, into the 21st Century, there has been a debate about New Media, Post-Media, and postinternet art and its relation to the Contemporary. My polemic about the transparency of the ISEA work in the museum relates to where works comply with artworld hegemony, whether by accident or by strategic targeting. It’s a serious question where postinternet works like Olson’s, which refer to media, are ‘electronic’ in nature…

But then, where does this leave works that utilize traditional media but employ electronic processes or production methods leave us? In short, to imply that a work shown at a venue like ISEA should be “media” art brings us to the old conundrum of work that is not as legible to larger audiences. On the other hand, purism/formalism has often led to ghettoization in electronic arts, so this is an ongoing discussion. For now, it appears that there are many hybrid discourses that are legible as art in contemporary venues.

ISEA 2015 is likely one of the grander editions of this festival that I have attended in recent years. Congratulations to the Vancouver team for an excellent job, and the participating organizations for supporting such a grand vision. It is no small feat that the team has integrated the festival into so many of the city’s extant cultural spaces, and in a way that is seamless with the sites involved. Next year, ISEA comes to Hong Kong, and it will be interesting how the team there fares.

Featured image: Jon Satrom (left) and jonCates at Intuit, Sept. 20, 2012 (right). image: Shawne Michaelain Holloway

Post-Static: Realtime Performances by jonCates and Jon Satrom @ Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art (Chicago). September 20, 2012. Programmed by Christy LeMaster

“Alchemy; the science of understanding the structure of matter, breaking it down, then reconstructing it as something else. It can even make gold from lead. But Alchemy is a science, so it must follow the natural laws: To create, something of equal value must be lost. This is the principle of Equivalent Exchange. But on that night, I learned the value of some things can’t be measured on a simple scale.”[1]

In 1966, Bell Laboratories scientists and engineers collaborated with artists to construct several performance-based installations under the title 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering. Works included Variations VII by John Cage and performance engineer Cecil Coker, in which a sound system pulled sounds from radio, telephone lines, microphones and musical instruments, and Carriage Discreteness by Yvonne Rainer and performance engineer Per Biorn, a dance event controlled by walkie-talkie and TEEM (theatre electronic environment modular system). Critic Lucy Lippard was wrote that the event was filled with technical problems and that the artists involved allowed the technology to take precedence over the art. She pointed out that no theatre people took part in the event and suggested that while this event did not offer a specific design for a new approach to theatre, it revealed the possibility that new approaches to theatre might be born from the combination of art and technology:

A new theater might well begin as a non-verbal phenomenon and work back towards words from a different angle. Departing from Samuel Beckett’s highly verbal, single-image emphasis, it could move into an area of perceptual experience alone, its tools a more primitive use of sight and non-linguistic sound. Such a theater would not necessarily be the amorphous carnival of psychedelic fame but could be as rigorously controlled as any other.[2]

She also observed that it was often impossible to understand the relationship between the technology and the events it triggered without reading the program, mentioning one such missed connection in Open Score, by Robert Rauschenberg and performance engineer Jim McGee. In this piece, tennis rackets were wired such that each impact of the ball on a racket turned off one light in the performance hall. Lippard wrote that this connection was not noticeable and thus the conceptual framework of the piece was lost to the audience.

To artists working at the intersection of art and technology more than forty years after this event, it is disturbing to note that the same issues Lippard pointed out —the subjugation of concept to technology, the failure of the technology itself and the lack of a radical approach to the intersection— are still all too present in many works taking place in the worlds of new media art [3]

. None of these were issues for jonCates or Jon Satrom as each presented a performance intersecting with the exhibition “Ex-Static: George Kagan’s Radios” at Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago, IL. Their performances serve as examples of new media employed as a tactic in support of art rather than “new media art” as a condition represented by infatuation with expensive devices. Instead of yet another demo of “cool” tech, the audience experienced a rigorously controlled blast of chaos.

The lights go down completely and we are illuminated by a large amorphous video projection behind a table stacked with equipment. The video is black and white as is the video monitor facing us from the table. jonCates moves between the back and front of the table, with purpose. While the equipment stack is familiar, multiple mixers and cases, this is no DJ set. Much closer is the image of a few men in long sleeves and ties tending to tables full of equipment for John Cage’s “Variations VII”. With several nondescript devices on and adjusted, the air around us has become alive with a noisy drone that, by this date and to this audience, is very familiar (parallels extend back to sonic attacks from Peter Christopherson and Chris Carter with Throbbing Gristle) but now the sound is comforting, an aural field that is neither alien nor distracting.

A droning, machine sound, or the droning machine sound, has become a ridiculously common element of a contemporary “experimental” sound and video work. It is thus all the more surprising to be instantly drawn into jonCates’ audio, to take pleasure in it and to lose track of time completely. We are watching him control the mixer and occasionally speak into the microphone that is set in front of a conspicuous security camera. Again, jonCates uses the most expected situation —the camera faces upward toward the video projection screen, creating a counter-clockwise tilting feedback loop. And again, we are not distracted by this, it is familiar yet beautifully framed and we are drawn in. We have been invited to a field constructed by a tactician expertly employing simple situations.

The raw quality of both the droning audio and the feedback loop combine with jonCates’ humble appearance to remove the expectation of a spectacle and we return to the real situation with questions: who is this man and what is he going to do? He keeps speaking into the microphone, his eyes look desperate, and, despite seeing him perform a similar (although much less engaging) performance at the 2011 Gli.tc/h festival, we are surprised as we realize, as it is nearly two-thirds complete, what he is doing: giving a lecture.

jonCates has been speaking for some time but only a few echoed fragments are reaching out beyond the drone. It has been an incantation without purpose, a repetition of the meaningless words one says when one is presenting something to an audience. Finally, jonCates drops the distortion and the volume on the droning sound and his voice becomes clearer. It is obvious that some communication is going to happen and everyone shifts slightly as we strain to remember how to listen to a voice. Are we here to see another performance or hear something important?. The voice is not strong and it has no authority. It is perfectly ordinary, slightly academic with a hint of vulnerability. It’s the voice of a mad scientist who has begun to understand that his experiments may be his undoing. At this point the piece could collapse and jonCates has not propped himself up with his technology. Instead, he’s used it to lead us to key moments and obliterating everything else. Still, he seems not so much frightened as curious to see where this will end, if what he needs to say can be given a short lifespan in this space. This is where performance lives —in the unfolding present. And jonCates says:

“…and I thought [?] … I thought [?] about how I should remix something in realtime for you that I should reflect upon the past, I should reflect upon [?] …patterns so I thought that I should probably do this as a remix and render it in realtime for you but then I found … from 1997…and it was sitting right next to the first tape … it was sitting right next to the first tape, had the same title as the first one, that also said “Flow” and right next to it had another a label that said “Remix” and I thought ‘I already made that piece’ [sampled voice droning: ‘oceanic waves upon waves upon waves upon waves’] and that’s almost too good to be true so I put the tape called ‘remix’ into the VCR, not this VCR. I had to buy a new VCR that VCR broke and … called ‘remix’ .. rendered in realtime for you … and I watched it, and almost [? ] [?] decide … I had already … [sampled voice droning: ‘we can stay in the spell of the laser lights’] … and I’ve been thinking about these things … [sampled voice droning: ‘we are all together … in the time space continuum of … of … of …’ and the drone continues.]”[4]

“The peculiarity of the time bounce, as he mulled it over, was that the resumption of the earlier state of being not only set physical objects back to their former positions, it actually wiped out the events of the lost hour. Like daylight saving indeed! With the lost hour unhappened, even memories of the time were obliterated…They might be reliving a given moment for the fifth time, the fiftieth, the five millionth, and never notice it!”[5]

“A representation is the occasion when something is re-presented, when something from the past is shown again —something that once was, now is. For representation it is not an imitation or description of a past event, a representation denies time. It abolishes that difference between yesterday and today. It takes yesterday’s action and makes it live again in every one of its aspects —including it’s immediacy. In other words, a representation is what it claims to be —a making present.”[6]

“For every organ-machine, an energy-machine: all the time, flows and interruptions. Judge Schreber has sunbeams in his ass. A solar anus. And rest assured that it works: Judge Schreber feels something, produces something, and is capable of explaining the process theoretically. Something is produced: the effects of a machine, not mere metaphors.”[8]

They are called radio buttons because on old car radios you pushed one button and the other popped out. The performances of jonCates and Jon Satrom were developed as an intersection with the exhibition Ex-Static: George Kagan’s Radios at Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, on display until January 5, 2013, curated by Erik Peterson and Jeremiah Hulsebos-Spofford.

“In the wee, wee hours your mind get hazy / Radio relay towers lead me to my baby / The radio’s jammed up with talk show stations / Its just talk, talk, talk, talk, till you lose your patience”[9]

jonCates makes Dirty New Media Art, Noise Musics and Computer Glitchcraft. His experimental New Media Art projects are presented internationally in exhibitions and events from Berlin to Beijing, Cairo to Chicago, Madrid to Mexico City and widely available online. His writings on Media Art Histories also appear online and in print publications, as in recent books from Gestalten, The Penn State University Press and Unsorted Books. He is the Chair of the Film, Video, New Media & Animation department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago:

http://systemsapproach.net/

Jon Satrom undermines interfaces, problematizes presets, and bends data. He spends his days fixing things and making things work. He spends his evenings breaking things and searching for the unique blips inherent to the systems he explores and exploits. By over-clocking everyday digital tools, Satrom kludges abandonware, funware, necroware, and artware into extended-dirty-glitchy-systems for performance, execution, and collaboration. His time-based works have been enjoyed on screens of all sizes; his Prepared Desktop has been performed in many localizations. Satrom organizes, develops, and performs with I ♥ PRESETS, poxparty, GLI.TC/H, in addition to other initiatives with talented dirty new-media comrades.

http://jonsatrom.com/

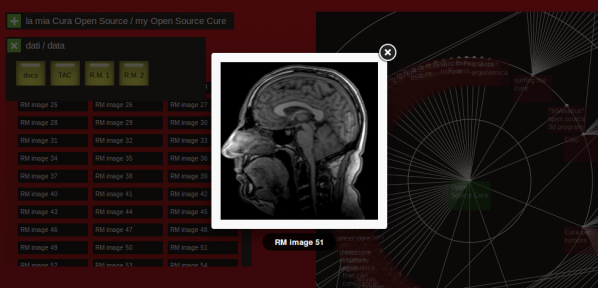

In September 2012, Italian tactical media artist Salvatore Iaconesi got the diagnosis. He had a glioma (glial cell brain cancer) of approximately 2×3 cm on the surface of his right hemisphere. Upon asking to see all the data relating to his condition, he found that all of the documents, MRI scans, and so on were in obscure not readily used formats. This meant that if one wanted to view the data, you needed specific or corporate software.

What he did then was remarkable. Iaconesi then hacked the formats of the documents and converted them into open-source ones that anyone could read could read with FLOSS (Free Libre Open Source) software. He then created the site, La Cura, where he presented his records as an “open source cure”. People around the world could access his records and then add their recommendations and findings about his condition, cancer, and so on. I begin this interview with Salvatore on September 15, 2012, and the La Cura website already has a rapidly expanding database of information at http://www.artisopensource.net/cure/.

Patrick Lichty: Salvatore, thank you for having this conversation. I remember that it was only a year and a half ago when we were shop-giving copies of the REFF tactical media book from your project, Fake Press in Rome. So, it was a shock when I learned of the glioma the day you launched the site. Could you talk a little about what is on the La Cura site?

Salvatore Iaconesi: Hi Patrick! Yes I do remember, too. And that is also a great explanation on what can be found at La Cura site: it is like one of our “fakes”, except that it is not a fake.

La Cura is about an alternative reality which I want to materialize on this planet, now. In this alternative reality, when someone has a serious disease, life does not end. One can be social, creative, and friendly. Work, art, design, fun and entertainment are possible for diseased people in this alternative reality, just as it is possible to reach out to find cures in any philosophy, time, strategy, culture or way one wishes. And consider that even technologies in this alternative reality are designed to enable and facilitate all this, actively promoting the freedom and autonomy of people.But, sadly, life is not like this alternative reality.

I wanted it to be my alternative reality, so I just did everything it took to bring that reality into the world. It’s like when you make an Augmented Reality application: you do a series of things to “materialize” some other things into ordinary reality. And then you have them, right there. So, La Cura is my personal Augmented Reality, in which, if I want to, I have all the tools and information I need to find a “cure” for my disease in one of multiple ways and strategies, which are medical, cultural, technological, emotional, artistic, political etc.

To achieve this, I have had to go through a series of obstacles:

The first is connected to language and information, as the first thing you notice at the hospital is that they are not really talking to you. Medical language is difficult and complex, and they rarely take action to make things more understandable to you. One of the testimonies I received in La Cura was that of a lady who has found herself in front of a doctor shouting at her: “You really think that I will explain to you why your thyroid has to be removed? It has to be removed! That’s it!”

This is really not “open”, in any sense. And, in more than one way, it is an explicit evidence of the approach which medicine has towards patients: they cease to be “humans” and become sets of parameters on a medical record subject to certain protocols and standards. When you are in the hospital, it’s often as if you’re not there. The only thing that matters is your data: blood pressure, heartbeat, magnetic resonance etc.

And the way in which information reflects this if handled in this context. Data formats may be, technically “open”, meaning that they are described somewhere but they’re really an explicit reflection that when you’re sick you “step out of society”. That data is usable and accessible only to “professionals” and to those people who have tools and skills to handle them.

I, as someone with considerable expertise with computers, have had some difficulties in opening them. Imagine someone else with less skill! Most people would not have been able to benefit from all the types of “cure” which I am currently accessing from a variety of sources and modalities. They would not have access to a “cure” that doesn’t end at a list of medicines and dosages, but spreads out into society.

To do that, I have had to hack into the information and convert it into really “open” data, using multiple formats that could be used by many kinds of people to do multiple things. In the format that the data was originally in, even if it was “technically open”, that data would have been seen only by “professional doctors” and, instead of being a “human being”, I would only have been a “patient”, or worse yet, a “case”.

PL: What do you want people to do with the information?

SI: Whatever they wish! Obviously! What is important in this case is that we must agree on what the “information” is… What I am publishing is my autonomous will to disclose my state of disease, including all data and medical information. I have my own purposes for this, but it does not necessarily mean that this purpose must/should be shared by others.

My personal purpose for this disclosure is to autonomously shape my own human condition. I have a disease but I am not a “diseased person”. I am a person. And, as such, I wish to create my personal “cure”, which has to do with my life, not with my disease. For what people know, I might even consider cancer as not being a “disease” at all! I might, for example, consider it an expression of the “cure”, such as if I adhered to Hamer’s theories. Which I don’t, or, at least, not in the sense that “I believe” in Hamer’s theories; I take them into consideration, but I don’t believe in them, just as I don’t believe in chemotherapy, in Aloe Vera, in Caisse Formula, in surgery, in shamanism, in healers, oncology or in any of these things. I take all of them into serious consideration, just as I seriously consider certain philosophies that say that we are made of energy, energy creates matter, and cancer is “matter” and so on. Therefore, cancer must be created by energy in some form. And so it could possibly be that I created cancer myself in a way or another.

So in this sense, I think it is very important to be able to easily look at the images of my cancer and to say “hello” to them. It is important to turn them upside down, to edit them with GIMP, to make mosaics out of them, to speak to them, asking “hello?” What are you doing in there? Did I do something to cause you? Can I change something to make you/myself feel better?”

Both scientific and traditional evidence shows that art, positive emotions, laughter, reduced stress, and a good social life have great practical benefits to the human body, I want to seriously consider that part of my cure could be formed by receiving an image of my brain with a smiley face drawn across it over the tumor, or a picture of a friend of mine, or a video of a projection mapping done with Processing in which the images of my cancer cover a whole facade of a building.

And since I don’t want to believe, but I want to take all of these things into serious consideration, I cannot focus only on the “medical” approach (and the related information, and its formats). I need to access all of my information in multiple ways, and I wish that everyone could do the same (as, from my point of view, it’s part of my Cure). And, even if “technically open”, the format in which my medical records have been disclosed is not enough, because it is “open for professionals” and so the only thing I could do with it would be “show it to professionals”, missing out on all the other wonderful parts of the “cure” which are available in the world.

This for me, is an interesting starting point to think about what things such as “OpenData” could mean. This is far beyond the idea that some government can some data according to ways in which some “professionals” could grab it and, do something like make a visualization or an App out of them. Who knows? In this sense, instead, we would not be talking about “technology”, we would be talking about “humanity”.

In the end, this is exactly what I’d like people to do with the “information”. I want the world to take the fact that I decided to disclose the fact that I have a disease and that I want to actively search for a cure for from all of these perspectives. In the meantime, I want to reconsider what it means to be “diseased” in current times and what new conceptions of the word “cure”, “medicine” associated with my condition could mean.

PL: What has happened since you launched the La Cura site?

SI: Lots of things. People are contributing and participating in multiple ways. There are testimonies, art, poetry, suggestions, videos, performances. Many doctors have called in to propose their methodologies and technologies. I have had very interesting and profound discussions with people who are prepared to deal with very complex things every day of their lives. I’ve communicated with doctors who are perfectly open to the possibility of such a paradigm change for the word “cure”. Artists, designers, activists, are giving me wonderful parts of “cure”. Many “patients”, “ex-patients”, “relatives” and “friends” of “diseased people” are sharing their experiences, are opening discussions, are sharing the information I found on possible medical cures. And so many people want to talk to someone in new and different ways, becoming again, simply, humans. Journalists from all kinds of media have started to ask for interviews, texts and videos. We stopped that after a while, as we don’t wish to turn this into merely a “spectacle”. We only keep on working on this with journalists which we know we can trust and which we know will not transform what we say to produce their news.

PL: For your information, I had an MRI in 2009 here in the States, due to my doctors’ concerns of something similar (nothing was found), but when I asked for the data, I got a CD full of JPEG images. Were you surprised when you found out your records were in particular formats?

SI: They were not really in a proprietary format. Let’s call them “exotic formats for professionals”. And yes, I would have expected something which I could have shared easily (such as your JPEG images, and maybe some meta-data in some easy to use format such as XML, or even a spreadsheet). But this was a sort of paradox: an “open” format which is really hard to open and to use for something else other than putting the CD in an envelope and (snail)mailing to the next doctor.

PL: What do you think the line is between privacy and data oppression? Would that be when the patient is denied access to their rights to access the information and distribute it as they wish?

SI: We should all know this by now. Privacy is not a problem unless the “system” is made by lousy people. We have tools to protect ourselves and to promote ourselves, and these tools are dangerous only when who runs them is a lousy person. Privacy protection arises through education (understanding what is privacy and when/where/how/why would I want to protect it) and through the acquisition of decent ethics from the people and organizations which run the entire infrastructure through which all our digital data goes through. And obviously, and most importantly, our ethics is created by helping each other out in a P2P way, teaching each other what we know, what we discover and how we decided to handle it when we found out.

There is no single line between privacy and data oppression. Not one which everyone would agree on. We have the tools for each one of us to tune this line to our own wishes, according to what we want to do, what are our desires, what are our objectives etc. We “just” need more places (physical, digital, virtual, institutional, occasional…) in which to discuss and share our points of view, as every time this happens, many things are learned on all sides.

PL: Do you consider your site a form of radical tactical media intervention?

SI: I can now say “I have a radical tactical media intervention in my head”. Cancer is the new Black. The Cancer is the Message. And we could go on. I don’t know. I guess I could call it that. I also guess I could call it a performance. I guess I could call it life. I guess I could call it hacking or whatever. I will just call it La Cura.

PL: What has been the most inspirational information, art, or otherwise that has resulted from the launching of the La Cura site?

SI: The most enlightening thing that happened is the experience of talking about the same exact thing using dozens of different languages. I have spoken with neurosurgeons, shamans, nutritionists, pranotherapists, doctors, activists, macrobiotics, hippies, cyberpunks, punks, friends, relatives. Most of the time, I received incredibly good advice. When you look at that advice from different points of view, you start to understand that you are really talking about the same thing, but in different languages.

For example, two of the most important things which you deal with when you talk about cancer are the idea of creating alkaline environments in your body (because cancer cells cannot stand them) and the facts that anti-oxidants are a great tool in support of any type of therapy (because of the molecular reactions which are at the base of cancer).

Well, speaking of just these two, it occurred to me that multiple theories deal exactly with these two concepts. I have had an esoteric master describe my cancer as an invisible living being, and he suggested to drive it away using sulfur and Rosa Rubiginosa oil, in ways which turn them into two incredible anti-oxidants and creators of alkaline environments as well as powerful stimulants of the immune system. I have also spoken with nutritionists and macrobiotics communities and learned about their instructions on choosing food, cooking and eating, many of which are directed exactly to that: anti-oxidants and creating alkaline environments, but through food.

And when an oncologist explained us his therapy, that’s exactly what it was about: powerful anti-oxidants and alkaline environments. And on, and on and on. Aloe Vera, Caisse formula, fungus theory, chemiotherapy, Di Bella method, potassium ascorbate, ketogenic diets, etc: all highlight cancer cells in some way; create an environment around them which is as alkaline as possible; anti-oxidate them; activate the immune system as powerfully as possible so that the highlighted weakened, cancer cells can be more easily “convinced” at mutating back to a decent form or to commit suicide with the help of the immune system. Realizing this is an enlightening experience: it spans across thousands of years and also helps you make some choices (things stand out when they speak about different things!).

Everything else that is going on in La Cura is wonderful, but having realized this fact is just incredible and fascinating. You start imagining about all the other things we discuss about in our daily lives using multiple languages (energy, politics, emotions…) and start to wonder what would happen if you turned on this shared, P2P modality in those cases as well.

PL: How do you hope that others will benefit from the conversation that you are starting through La Cura?

SI: I don’t “hope” anything. I did this because I felt I needed to. When one talks about “revolution” dialogues start arriving at the point when one says, “Let’s burn everything down!” “Let’s destroy everything!” and so on.

We know we can’t do it. We can’t “destroy everything”. It’s not possible. What we can do is to create a reality as if everything already happened – as if the “revolution” already happened, as if the world had been burned down already, and rebuilt, just the way you like it. We can live life like this. It is a bit more than “seeing things”. But you do Augmented Reality, Patrick. You know what I mean. It’s a bit more than “writing”, it’s about creating worlds.

PL: As of this interview, what is the prognosis of your condition?

SI: Depends on what perspective you look at it from. From the medical point of view I have a low-grade glioma at intensity which is still undecided, between 1 and 2 (we will have to wait an histologic exam to know for sure). From the human point of view: I am fine! I have no apparent symptoms. I just need to be careful because if I find myself in stressful situations I could react by having an epileptic shock. So it is not advised that I drive or things like that. It’s the perfect excuse! 🙂

PL: Don’t you think it’s funny that the abbreviation for your name is “si”?

SI: Sì! Obviously 🙂

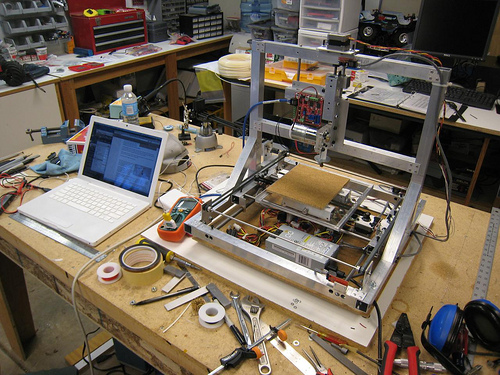

Featured image: London Hackspace http://wiki.london.hackspace.org.uk/view/London_Hackspace

…the machine is always social before it is technical.

(Gilles Deleuze)

Though the term ‘lab’ conjures the image of a fairly sanitised environment optimised for scientific experiments and populated by people in white coats, media labs – centres for creative experimentation – are quite different. At their most basic, they are spaces – mostly physical but sometimes also virtual – for sharing technological resources like computers, software and even perhaps highly expensive 3D printers; offering training; and supporting the types of collaborative research that do not easily reside elsewhere. In the early-to-mid-1990s, partly propelled by the exciting possibilities of the internet and associated web browser technologies, groups began to coalesce, bent on developing access to the inherent potential of collective creativity. With the exuberant new dot.com businesses fuelling a ‘creative economy’, the Californian ‘cybercafé’ (surf the internet and slurp the coffee) was emulated in urban centres around the UK and in some cases artists were heavily involved. They saw the internet’s myriad ways of changing the way we make, think about and share art – not to mention its capacity for social empowerment – and wanted to harness these qualities quickly and effectively. With many practitioners coming from the spaces, practices and communities forged by the independent film and video movement, the phenomenon of the UK media lab was born. However, despite the importance of these spaces as the hybrid homes of the then emergent and now embedded creative activities that characterise today’s rich field of digital and media practices, their history and contribution to current lab environments has been little discussed outside a niche arena.

Early Media Labs

Two of the earliest UK media labs were Artec and Backspace (aka Bakspc), both based in London. Artec, which was established in 1990, was initially funded by Islington Council and ESF (the European Social Fund), but soon won additional support from Arts Council England. Conceived by Frank Boyd and Derek Richards, its focus from the outset was to deploy technology for social empowerment and, early on, it provided valuable professional training to the long-term unemployed. In this sense, it did not operate from within an arts context proper, but combined art and technology in the name of social integration. Creative projects were led by Graham Harwood, whose own artistic practice and his collective Mongrel were formed through associations at Artec.

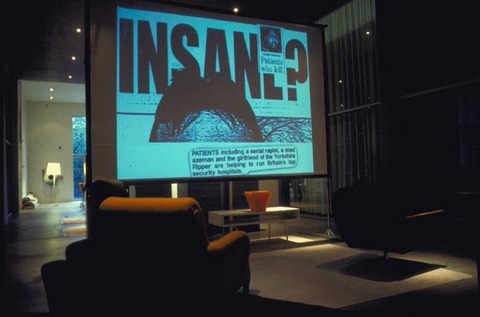

Harwood and Mongrel’s practice is known widely for scrutinising social, political and cultural divisions through a framework of technology. A notable piece from this period was Rehearsal of Memory (1995), which took the collective experiences of staff and patients at Ashworth high security mental hospital, near Liverpool, and presented them as a unified and anonymous computer-based group portrait. Now available as a CD-ROM, the work strongly undermines the assumptions we make about mental health, blurring the line between those branded ‘normal’ or not. It is an excellent example of the way artists and media labs habitually combine creative activities with technology to give people a renewed agency. Around 1995, Peter Ride was brought on board to curate a stream of activity called Channel, which lead to further powerful artworks including Ubiquity (1997) by David Bickerstaff and Susan Collins’ In Conversation (1997).

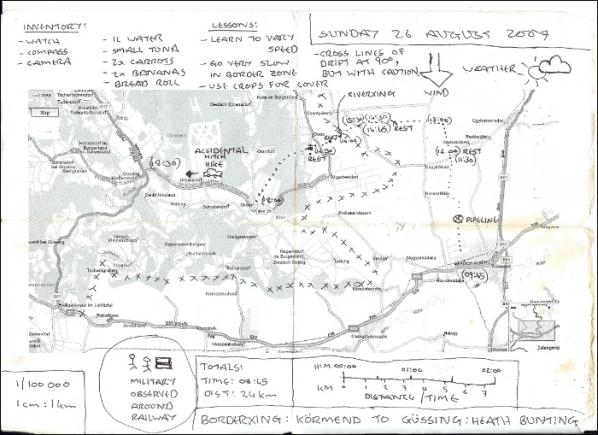

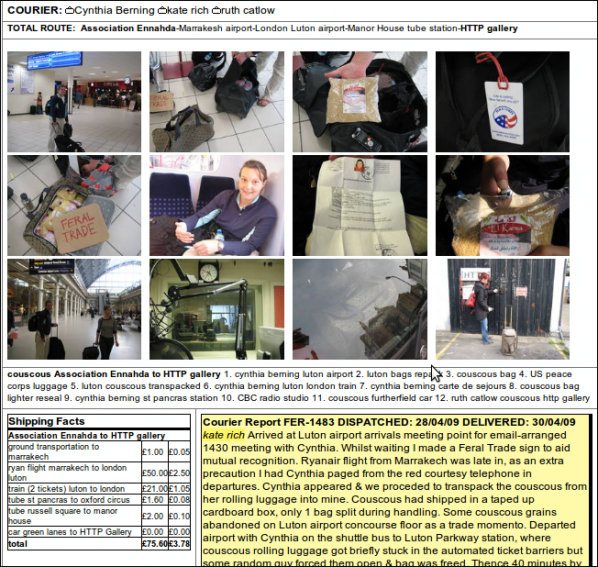

Without regular public funding, Backspace started out as an independent self-organised cybercafé. Initiated by James Stevens as a ‘soft space’ adjunct to his commercial web design business, Obsolete, it had a physical studio and lounge on Clink Street. People could drop in and use the web access and computer terminals in exchange for a nominal membership fee and commitment to maintain the space. What is notable about the Backspace model is how it attempted to foster a co-operatively managed resource. It exemplified a preoccupation amongst internet culture devotees with autonomy and new forms of governance, and struggled with all the contradictions of such ideals alongside the fact of its commercial parent entity. Obsolete shared its (at that time) capacious bandwidth. This gave people web hosting and streaming capabilities that would otherwise have been prohibitively expensive; allowed for the hosting of many artistic projects produced within the space itself; and facilitated many early streaming experiments with link-ups between other European media labs including as E-lab in Riga, Lativa and Ljudmila in Llubljana, Slovenia. Early attendees and co-facilitators of Backspace now list some central figures of the Digital and New Media art fields including: Matt Fuller, Simon Pope, Armin Medosch, Heath Bunting, Ruth Catlow, Pete Gomes, Manu Luksch and Thomson and Craighead – even Turner Prize winner Mark Lecky was a regular for a while.

Globally distributed discussion networks provided a discursive layer for these media labs, with early mailing lists such as Nettime, Rhizome and Syndicate forging international connections around technology, art and politics. Likewise, Mute (at first a newspaper, then a glossy magazine, now a web journal) provided regular critical commentary on burgeoning digital culture.

Foundationally different, Artec and Backspace were united by a belief in the importance of access to tools and training within a social context. In slightly differing ways, they put creative experimentation and social concerns at the centre of the agenda via technology. This was to become an important organisational strategy for this sector. Though both spaces have since closed, Stevens continues to build social and technological infrastructure as Deckspace, at Borough Hall, Greenwich. Without a physical space, Frank Boyd has evolved his media lab system into an industry-orientated programme called Crossover, which assembles creative professionals to workshop cross-platform ‘experiences’ from a variety of creative arenas including film TV and the computer games industry. Crossover is one of many peripatetic media lab models that privilege collaborative creative processes, although it is more goal-orientated than most as participants often pitch to a panel of industry commissioners.

Process over Product

With less of an eye on industry and an abiding interest in the creative process itself, PVA MediaLab was formed in 1997 by artists Simon Poulter and Julie Penfold. In its first incarnation, it took up residence at Dartington College of the Arts, with funding from South West Arts. While there, artists were offered a well-equipped space in which to experiment with technology and develop ideas. In fact it is this developmental freedom that forms another core operational component of the media lab. Rather than asking artists to arrive with pre-formulated projects, or expecting them to see a piece through from start to finish, media labs have consistently placed value on self-determined exploration. PVA helps artists to manufacture methodologies rather than final artworks, fully designed products or content packages. They have also led the way in assisting other media labs to produce a similar system, through their Labculture programme. Highly itinerant, the Labculture model adjusts itself to host organisations, like Vivid, in Birmingham, so they can learn how to set and achieve goals while building the sorts of lasting partnerships that will sustain future activity.

This shared or Open Source way of working integral to media lab culture is also exemplified by GYOML (Grow Your Own Media Lab). A collaborative project between media labs Folly, Access Space and the Polytechnic, GYOML was designed to help generate more media lab initiatives. It has included: ‘GYOML in a Kitchen’, a sound recording and editing workshop by Steve Symons (Lancaster); ‘GYOML in a Van’, which staged an introductory workshop in media-lab culture for community group leaders (Lancaster); a game-centred ‘GYOML for teenagers’ (Rochdale); and ‘GYOML at the Canteen’, catering to film-makers and professional artists with an interest in open source (Barrow-in-Furness). Legacies of this project include the Digital Artists Handbook, an impressive guide to Open Source tools and techniques and ‘Grow Your Own Media Lab (the graphic novel)’, a set of inspiring case studies. Folly continue to work very much in this manner, forming essential infrastructural relationships as and where needed and guiding others through the adoption of free software.

Another example of this attention to operation and openess comes from GIST Lab, in Sheffield, which energises community-based projects through a space that hosts meetings and workshops. Even without a dedicated tech suite, their knowledge-exchange is a short-cut to all manner of original cross-over work, and they have supported yet another project that literally and metaphorically recreates aspects of the media lab model. 3D printing (or rapid prototyping) is increasingly popular in producing anything from car parts to jewellery, by layering materials like plastic into finished three-dimensional objects. RepRap, however, is able to print the spare parts it needs to be built while it is still itself under construction. Just like media labs, this self-replicating 3D Printer is all about sharing access to a successful system.

If media labs are not driven by material production, neither are they all about technology. Arising from the work of the art group, Redundant Technology Initiative, Access Space in Sheffield established its media lab through the use of free and recycled technology and learning. Given our cultural predisposition for wanting the latest, fastest equipment and our reprehensible dumping of perfectly serviceable technology, abundant hardware is sourced from all manner of locations. The latest Free and Open Source software is installed on the hardware where expensive proprietary software once lay and the media lab space, complete with this equipment, is opened to the public five days a week. The one proviso placed on this access – continuing the recycling theme – is that once a media lab participant has learnt how to do something, they should pass this knowledge on. As evidence of the success of this system Access Space boasts impressive outreach capacity: more than a thousand regular visitors, of which only about thirty-five percent are university educated, and over half are unemployed, and they habitually work with people experiencing disabilities, learning disorders, poor health, homelessness or other measures of exclusion.

One of the projects that clearly shows what they do is Zero Dollar Laptop, a collaboration with the Furtherfield organisation and community. Through a series of workshops, homeless participants are given the ability to use and maintain a free laptop complete with free software in self-led creative projects. It is this model of learning through self-directed creativity that arises again and again in media labs because it provides demonstrable results in helping people acquire and retain the skills they need. Without ‘bells and whistles’ new technology, Access Space emphasise the importance of ideas over technology and demystify all manner of computer-based skills. SPACE Studio’s MediaLab is also an excellent example of a lab working at a range of levels to offer beneficial specialised training. They teach software packages at a professional level to film makers, artists and a range of media industry workers, as well as offering film-making and media training for NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) teenagers in the local area. There are also a number of DIY Technology workshops including those regularly hosted by MzTEK who have expanded their operation as a result of their connections with SPACE. MzTEK are all about encouraging women to build technical skills and enter the new media sector. Growing from a small group to wide and supportive network they answer underdeveloped areas of knowledge. In addition to this, SPACE’s PERMACULTURES residency series has, to date, hosted eight residencies supporting over eleven artists, helping them explore technology and go on to show in a range of spaces.