NeMe and curator Marc Garrett, Co-Founding and Co-Artistic Director of Furtherfield, have the pleasure to invite you to Children of Prometheus at NeMe Arts Centre, Limassol. The exhibition investigates the landscape of a rapidly transforming world and how some of these shifts inform and affect our immediate environment.

The complex nature of the ancient Greek myth of Prometheus has inspired philosophers, authors and artists throughout many centuries and will continue to do so because of the powerful contradictions which it embodies which reflects the ongoing dualities present in both the human mind and physical existence. Acknowledging that the Promethean spirit lives on in the ambitions of science and technology, which in many cases defies the limits imposed upon humanity by nature, the post-modern Prometheus belongs to an organised world focused on the technology of the internet. This rapidly expanding domain, with its presumed ethos of democracy belies the technologies of data mining, fake data, targeted personalised advertising, etc used by global conglomerates to engineer/manipulate people’s perception via media into a state of hyper-real urgency by dislocating the individual from physical realities.

Yet despite the plethora of work in the field, there has not been any sustained attempt to think through the larger philosophical, sociological, economical, political and cultural implications of new technologies. A crucial methodology for this exhibition is to view these themes through the eyes of the artists. Children of Prometheus generates a visual discussion around this persistent narrative that is still very enmeshed into our contemporary context.

This exhibition was originally produced in partnership with LABoral, in Gijon, and is an extension of the Monsters of the Machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century, 18 Nov 2016 – 21 May 2017.

AOS (Art is Open Source) was born in Italy, in 2004 as an interdisciplinary research laboratory focused on merging artistic and scientific practices to gain better understandings about the mutation of human beings and their societies with the advent of ubiquitous technologies. AOS was created by Salvatore Iaconesi (engineer, hacker, artist, designer, TED Fellow, Eisenhower Fellow, Yale World Fellow, Prof. in Interaction Design at ISIA Design University in Florence), joined by Oriana Persico (social scientist, artist) and now includes more than 200 artists and researchers from across the world.

Alexia Achilleos is a Finnish-Cypriot artist with a background in fine art, archaeology and cultural studies. Her work is concerned with cultural, political and social issues which impact identity, specifically linked with cultural heritage & tourism, colonialism and national identity politics. She explores interactions, hybridisation and power struggles – especially how a cultural object’s function can change according to geography, history and politics, and how it can be suited to the needs and interests of the adopting culture.

Egor Chemokhonenko lives and works in Cyprus. He is a programmer and open source enthusiast, and keen to mix technologies with the arts. Egor has previously collaborated as a developer with fashion and arts projects such as Lumpen Agency and Cosmoscow Contemporary Art Fair. Machine self-portraits is his second programming for an artwork using artificial intelligence.

Anna Dumitriu is a British artist whose work fuses craft, sculpture and bioscience to explore our relationship to the microbial world, technology and biomedicine. She has an international exhibition profile, having exhibited at venues including The Picasso Museum in Barcelona, The Science Gallery in Dublin, The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) Taipei, and The V & A Museum in London. She is artist in residence on the Modernising Medical Microbiology Project at the University of Oxford, a visiting research fellow: artist in residence in the Department of Computer Science at The University of Hertfordshire, and an honorary research fellow in the Wellcome Trust Brighton and Sussex Centre for Global Health at Brighton and Sussex Medical School.

Mary Flanagan is a writer and artist whose practice(s) extend into science, design, psychology, and futures studies. Her encompassing work in theory and criticism, with a wide range of essays and books on digital culture, is in constant dialogue with her use of digital and material platforms to create dynamic, constantly evolving systems that reflect cultural questions and trigger reflection. She is the author of the book Critical Play: Radical Game Design, the poetry collection Ghost Sentence, co-author of Values at Play in Digital Games and Similitudini. Simboli. Simulacri, and co-editor of the collections Reload: Rethinking Women in Cyberculture and Re:Skin. Her essays and articles have appeared in Salon, USA Today, The San Francisco Chronicle, and The Huffington Post.

Carla Gannis is an artist who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. She received a BFA in painting from The University of North Carolina at Greensboro and an MFA in painting from Boston University. In the late 1990s she began incorporating net and digital technologies into her work. Gannis is the recipient of several awards, including a 2005 New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Grant in Computer Arts, an Emerge 7 Fellowship from the Aljira Art Center, and a Chashama AREA Visual Arts Studio Award in New York, NY. She has exhibited in solo and group exhibitions both nationally and internationally. She is currently Assistant Chair of Digital Arts at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.

Marinos Koutsomichalis is a media artist, scholar and creative technologist. He was born in Athens, GR (1981) and has since lived and worked in various cities around the world. His practice is hybrid, nomadic, and ethnographic, involving field-work, creative coding, critical theory, making, lecturing, live performance, workshopping, artist/research residencies, ‘Doing-It-With-Others’, and hands-on experimentation with materials and technologies of all sorts. His artistic corpus is prolific, yet persistently revolving around the same few themes: material inquiry/exploration; self-erasure; the quest for post-selfhood. He has hitherto publicly presented his work, pursued projects, led workshops, and held talks worldwide more than 250 times and in all sorts of milieux: from leading museums, acclaimed biennales, and concert halls, to churches, industrial sites, and underground venues. He has held teaching and research positions in various academic institutions, has published a book and numerous academic/scientific articles, and is currently a Lecturer in Multimedia Design for Arts at the Cyprus University of Technology (Limassol) where he co-directs the Media Arts and Design Research Lab.

Kypros Kyprianou is an artist based in Bristol. He investigates scientific, political and cultural constructs using materials drawn from official archives, reverse-engineered objects, scenarios from film and hearsay. His practice is often collaborative, culminating in performance, video, publications and site-specific intervention.

Gretta Louw was born in South Africa in 1981 but grew up in Australia. She received her BA in 2001 from the University of Western Australia and Honours in Psychology in 2002, subsequently living in Japan and New Zealand before moving to Germany in 2007. Her work has been exhibited widely, including in public institutions such as the Kunstmuseum Solothurn (CH), Münchner Stadtmuseum (DE), National Portrait Gallery (AUS), UNSW Galleries (AUS), LABoral (ESP), and Galeri Nasional Indonesia (IDN). She was awarded the Heinrich Vetter Preis by the City of Mannheim in 2014 and the Bahnwärter Stipendium by the City of Esslingen am Rhein in 2017, as well as studio scholarships in Munich and Mannheim. In 2017, Louw was an artist in residence at MozFest in London at the invitation of the Tate and the V&A museums in collaboration with the Mozilla Foundation. Louw has also curated thematic exhibitions at museums including the Villa Merkel (DE), Furtherfield Gallery (UK), and Paul W. Zuccaire Gallery (US) and contributed essays to numerous catalogues and publications.

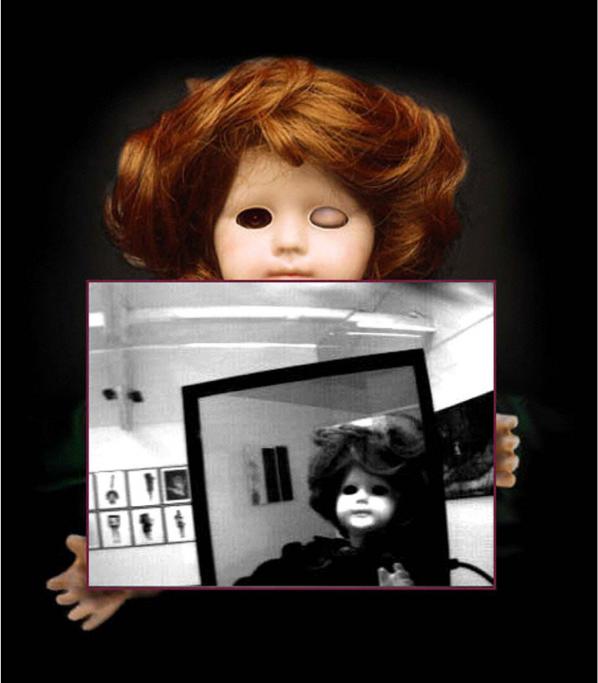

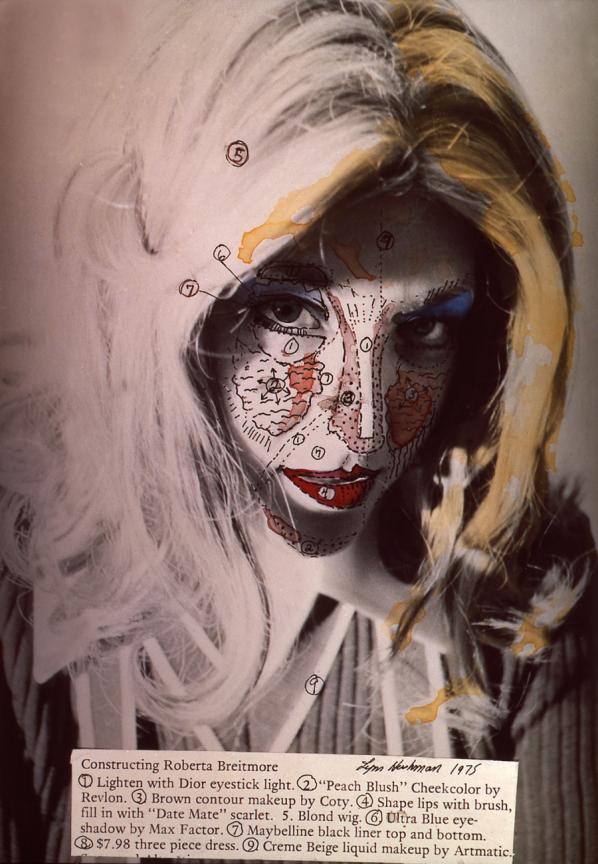

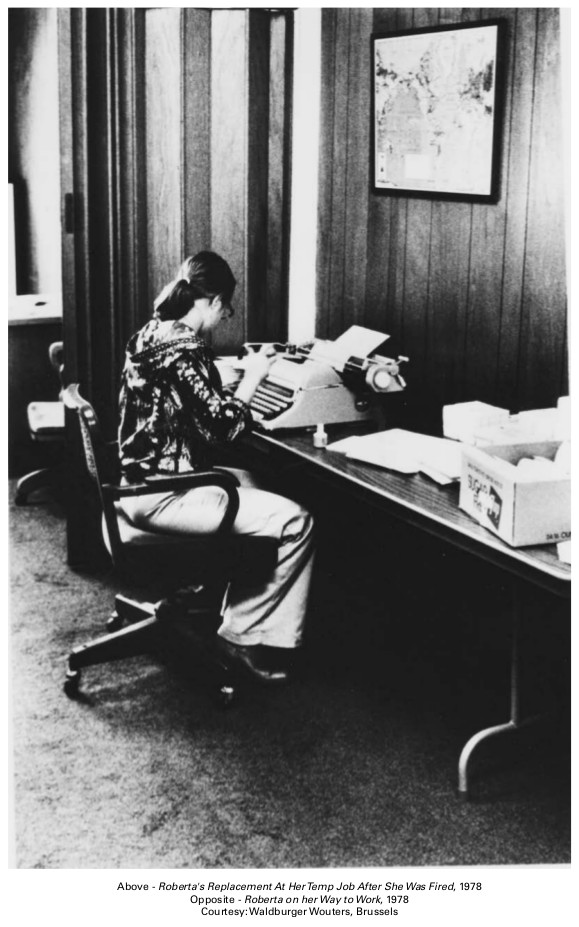

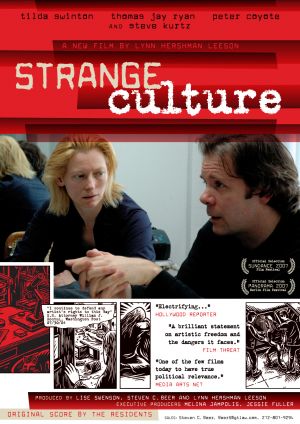

Lynn Hershman Leeson is an artist and filmmaker whose work has been internationally acclaimed over the last five decades. Cited as one of the most influential media artists, Hershman Leeson is widely recognised for her innovative work investigating issues that are now acknowledged as key to the workings of society: the relationship between humans and technology, identity, surveillance, and the use of media as a tool of empowerment against censorship and political repression. Over the last fifty years she has made pioneering contributions to the fields of photography, video, film, performance, installation and interactive as well as net-based media art. ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, Germany, mounted the first comprehensive retrospective of her work titled Civic Radar. A substantial publication, which Holland Cotter named in The New York Times “one of the indispensable art books of 2016.” Lynn Hershman Leeson is a recipient of a Siggraph Lifetime Achievement Award, Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica, and a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship. In 2017 she received a USA Artist Fellowship, the San Francisco Film Society’s “Persistence of Vision” Award and the College Art Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

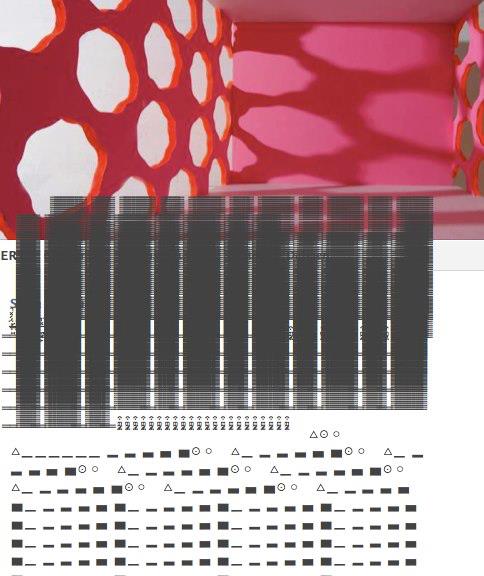

Joana Moll is a Barcelona / Berlin based artist and researcher. Her work critically explores the way post-capitalist narratives affect the alphabetization of machines, humans and ecosystems. Her main research topics include Internet materiality, surveillance, social profiling and interfaces. She has lectured, performed and exhibited her work in different museums, art centers, universities, festivals and publications around the world. Furthermore, she is the co-founder of the Critical Interface Politics Research Group at HANGAR [Barcelona] and co-founder of The Institute for the Advancement of Popular Automatisms. She is currently a visiting lecturer at Universität Potsdam and Escola Superior d’Art de Vic [Barcelona].

Cédric Parizot is a Researcher at the CNRS. He is an anthropologist of politics and currently works at the Institut d’Etudes et de Recherche sur le Monde Arabe et Musulman (IREMAM, Aix en Provence). His research focuses on mobility and borders in the Israeli – Palestinian space. He has recently published with Stephanie Latte Abdallah A l’ombre du mur: Israéliens et Palestiniens entre séparation et occupation, Arles, Actes sud, 2011. He coordinates a transdisciplinary research programme involving social scientists, scientists, artists and professionals in order to elaborate a multidisciplinary approach on the mutations of 21st century Borders in Europe and the Mediterranean at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Marseille, France.

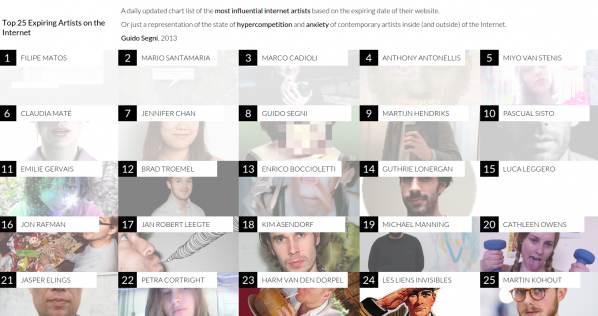

Guido Segni, aka Clemente Pestelli, lives and works somewhere at the intersections between art, pop internet culture and data hallucination. With a background in Hacktivism, Net Art and Video Art, his work is characterized by minimal gestures on technology which combine conceptual approaches with a traditional hacker attitude in making things odd, useless and dysfunctional. Co-founder of Les Liens Invisibles, he exhibited in galleries, museums (MAXXI Rome, New School of New York, KUMU Art Museum of Talinn) and art & media-art international festivals (International Venice Biennale, Piemonte SHARE Festival, Transmediale). Currently he teaches at the Accademia di Belle Arti of Carrara, directs the imaginary REFRAMED lab and he is part of the editorial committee for the project Atypo.

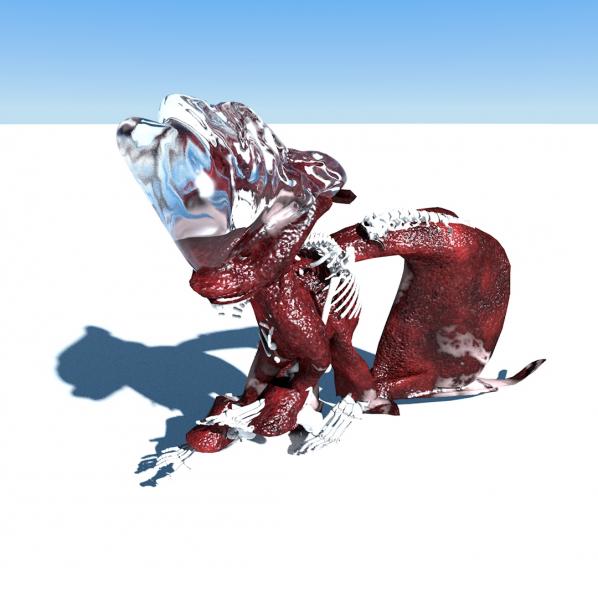

Alan Sondheim is an independent writer/theorist/artist. He co-founded the Cybermind and Wrytingemail lists. He is editor of Being on Line and author of .echo, Disorders of the Real and The Wayward. He is also published widely online and his video/sound work is internationally exhibited. Sondheim is the developer of the concept of code work, wherein computer code itself becomes a medium for artistic expression. He explores notions of the ‘abject’ in the masculine and feminine online, and more recently has dealt with the machinic using the language of computer code to articulate novel forms of identity in cyberspace. His work crosses over between philosophical explorations and sound poetry and more recently he has returned to the language of music using the tonalities of a wide range of ethnic instruments. His current areas of exploration include: the aesthetics of virtual environments and installations; mapping techniques using motion capture and 3D laser scanners; Buddhist philosophy and its relation to avatars and online environments; and experimental choreography.

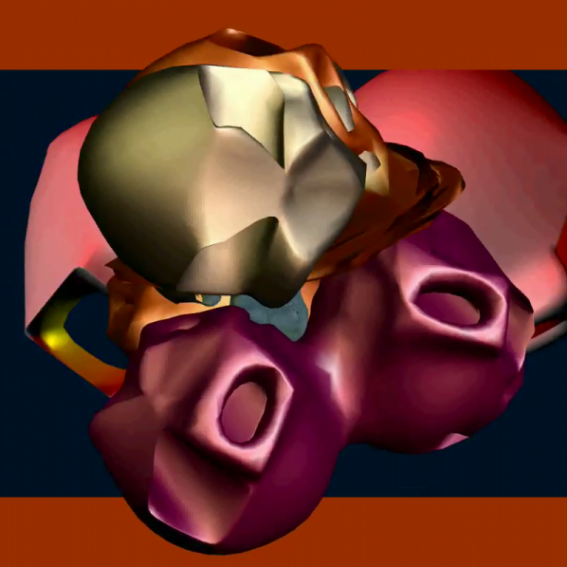

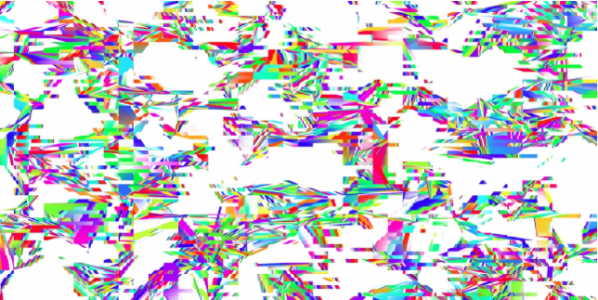

Featured Image:

Detail from ‘The Garden of Emoji Delights Triptych’ (2014) by Carla Gannis

3 October 2019 – 5 January 2020, Daily. Free Entry

The roar of an airplane is a familiar sound for many parts of west London, home to one of the busiest airports in the world and the subject of a new exhibition, Air Matters at Watermans Arts Centre in Brentford, just a few miles away from Heathrow.

Echoing the experience of hearing an aircraft in action, sound itself plays an integral part in the show and leads with The Substitute (2019) by Hermione Spriggs and Laura Cooper. Through overhead speakers outside the main entrance, visitors are greeted by an authoritative voice musing on the fate of local flocks in an airspace strictly controlled by humans and their contraptions, intermittently reciting names of affected birds like a tribute, and ultimately urging listeners to “work with nature” which sets a critical tone.

The audio installation is reminiscent of public announcements at airports, a strategy that continues into the foyer with Frequency (2019) by Louise K Wilson. It features intimate anecdotes of air travel through resonance devices on a skylight roof where planes might fly by at any moment. Speaking softly akin to ASMR, one person wonders about the destinations of travellers, while another recalls vivid memories of flights that seem traumatic, bouncing back and forth between excitement and anxiety.

The theme reaches its crescendo inside the gallery, with a mixture of ambient sounds reverberating across the space from Ascending Composition I (For Planes) (2019) by Kate Carr, an atmospheric concoction of incidental noises recorded around Heathrow including birds, markets, and trains on tracks. With pocket-sized media players attached to deconstructed speakers on strings of fabric, the installation documents an intervention that already took place when the work itself flew up on balloons blasting whispers from the ground, a small but meaningful gesture challenging the sonic waves of jumbo jets that dominate the surrounding sky and soundscape.

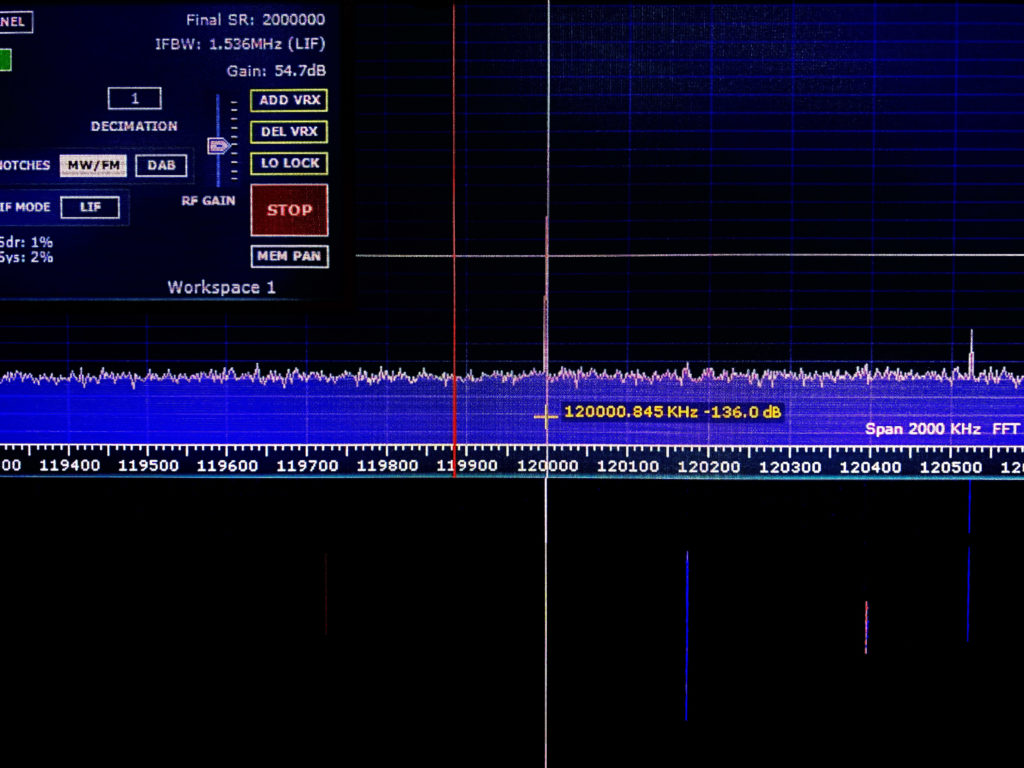

This act of defiance flows into Skyport (2019) by Magz Hall, a mixed media installation with a set of frequency scanners emitting an unsettling static. The title refers to a pirate radio station based along a Heathrow flightpath in the 1970s, illustrated with archival images and texts from an attempt to reclaim airwaves colonised by traffic control and engine noise. The work emulates this spirit with an LCD screen broadcasting airport channels as visual wavelengths, the contents of which are protected as classified information in UK law, consequently questioning ownership, access, and authority over radio frequencies.

The symphony of sounds become unavoidable throughout, and there is a possibility that it might grow vexing for some, perhaps more so for the people that work here who may not have a choice but to hear it again and again. Yet, as irksome as that might be, it is a crucial part of what makes this show effective. The audible pieces collectively transform the spaces into simulations of airport lounges and peripheral towns, simultaneously mimicking and counteracting oppressive noises from airplanes and terminals that have become inevitable in contemporary life, irrespective of its value and/or harm.

Beyond aural tendencies, the exhibition reaches further by considering scale and movement. The sheer volume of Capsule (2019) by Nick Ferguson is an imposing presence in the gallery with a wooden sculpture modelled after the wheel bay of a Boeing 777, floating a few inches off the ground and hovering over visitors. Shown alongside printed images of microscopic substances found in a real plane, it orchestrates a juxtaposition between the enormity of a flying machine and the imperceptible residue it accumulates, revealing traces from the many places it has been including sand, spores, and bacteria.

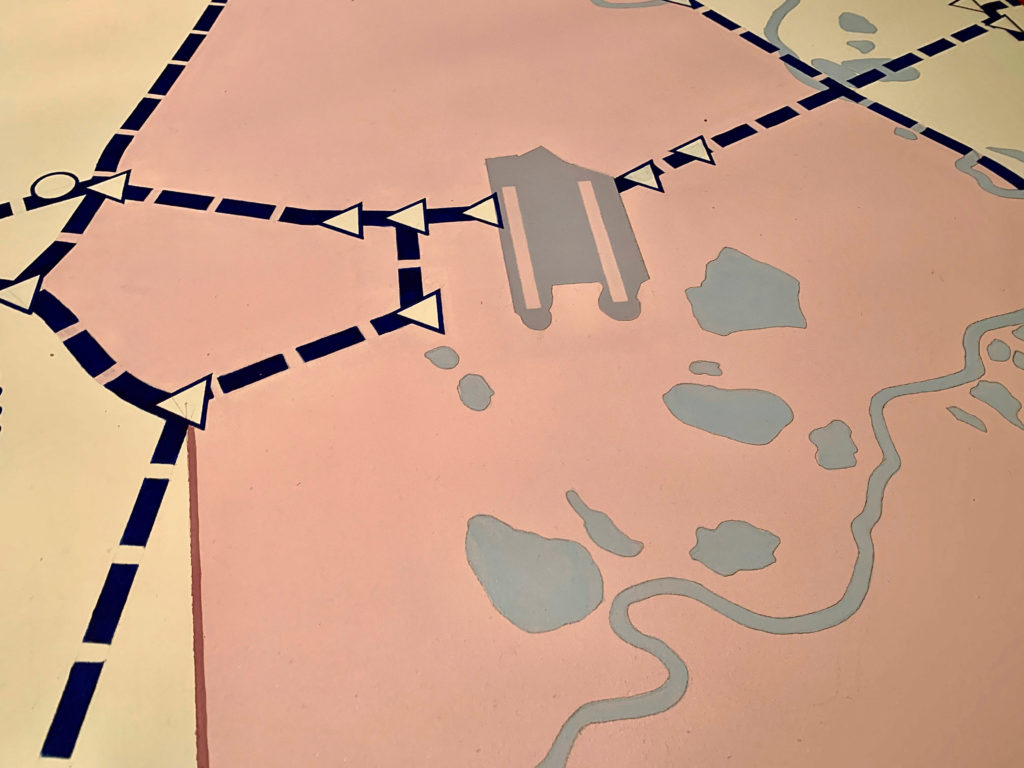

A map nearby, Heathrow (Volumetric Airspace Structures) (2019) by Matthew Flintham, takes the viewer back to west London with a bird’s eye view of the airport complex. Presented on a table that might be used for urban planning, military operation, or board games, it illustrates the topography of the area highlighting a vast infrastructure beneath large sections of controlled airspace, seemingly encroaching on everything else which becomes almost invisible or insignificant.

Navigating the show functions as an exercise of remembrance in many ways, bringing to mind a number of issues that have been at the forefront of public discourse in recent years: from the role of aviation on climate change, to its impact on local communities and ecosystems around airports. And it comes, as if on cue, at a period of heightened environmental concern, propelled most prominently by the Extinction Rebellion movement and climate activist Greta Thunberg, ringing the alarm on the perils of flying.

The controversial Heathrow Airport Expansion also comes through in this context, caught between government plans for future economic growth, and the ongoing resistance from neighbouring residents with campaigns like Stop Heathrow Expansion, No Third Runway Coalition, and Heathrow Association for the Control of Aircraft Noise.

It conjures up conflicting perspectives that unpack a classic dilemma for a society in flux. On one hand, the flight industry is evidently harmful because of its pollution to the planet and the unfair toll on local hosts. Yet, on the other, it is part of a system that facilitates international trade, freedom of movement, and cultural exchanges, each one increasingly more accessible to broader people beyond a privileged few who will always have it. And while it has serious problems that must be addressed, some of which are rightly pointed out here, a world without it entirely is at risk of descent into tribalism and isolationism.

With so much at stake at this particular time and place, the exhibition feels important for its worthwhile attempt in raising these pertinent questions through art, successfully using Heathrow as a case study for matters that undoubtedly have wider implications.

Like the rumble of a plane and many works in this show, the politics of flying will become inescapable as air travel is projected to almost double in size by 2036, despite recent backlash from flight shaming, the rise of staycation, and a spotlight on frequent flyers. The solutions to its unintended consequences are not as straightforward as it might seem, and will likely require a nuanced approach combining systemic changes, paradigm shifts, technological developments, and personal adjustments, all of which cannot come soon enough.

Air Matters: Learning From Heathrow is at Watermans Arts Centre until 5 January 2020. Curated by Nicholas Ferguson in collaboration with Klio Krajewska. Supported by Arts Council England, Forma, London Borough of Hounslow, Kingston School of Art, and Richmond University.

Featured main image: Kate Carr. Image 11. NF. Ascending Composition 1 (For planes). Mixed media, 2019. Included in Air Matters: Learning from Heathrow. 3 October – 5 January 2019.

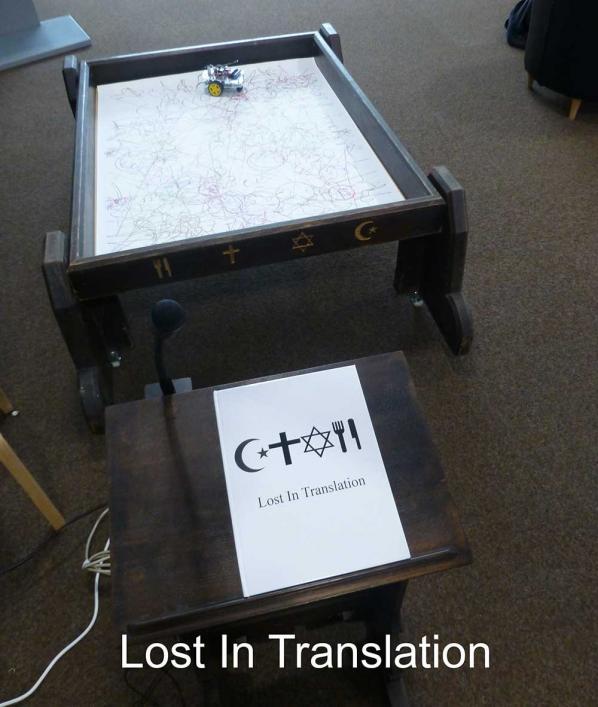

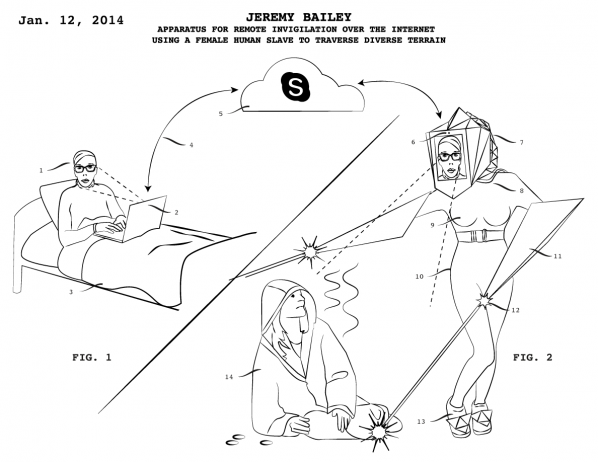

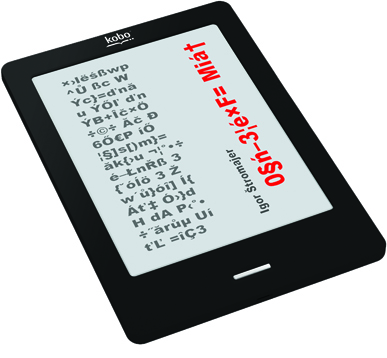

Disobedient Electronics: Protest is a limited edition publishing project that highlights confrontational work from industrial designers, electronic artists, hackers and makers from 10 countries that disobey conventions. Topics include the wage gap between women and men, the objectification of women’s bodies, gender stereotypes, wearable electronics as a form of protest, robotic forms of protest, counter-government-surveillance and privacy tools, and devices designed to improve an understanding of climate change.

I was one of the lucky few to receive a hard copy of this fine little zine, a handmade limited edition of 300, put together by Canadian artist & researcher Garnet Hertz. It features 24 contributions of critical art & design, many of which taking a strong stand on feminism and surveillance /privacy issues, indispensable in current debate. Hertz initiated this publication in response to post-truth politics, in itself a notion shrugged off by populist drivel – “Politicians have always lied.” – Ptp- strategies involve the removal of scientific context from popular claims in order to comfort the masses in turbulent times of change. Such trends are noticeable in culture and thus in the DIY- movement too. After a disappointing visit at a maker’s fair, which essentially promoted the aesthetic design of blinking LEDs and the 3D-printing of decorative junk in an overall atmosphere of relentless marketing, the manifesto of Disobedient Electronics caught my attention, reflecting my impressions accordingly.

Decline of culture becomes visible as ‘popular’ themes such as sustainability or integration policies are readily adopted but actually serve as mere buzzwords to increase the marketability of events and products. Since it became profitable to sell electronic boards and a variety of accessory components, the prosumer (Ratto, 2012) is bound to available materials and building instructions and not encouraged to experiment or imagine alternatives to already available commercial design. Therefore many important layers of technology get ignored or regarded as not worth exploring due to the fetishisation of the final result. Although focus should be on action oriented making, tactile objects /installations are important when linguistics fail. We have already incorporated digital structures in every social aspect of our lives and it is difficult to observe let alone express them.

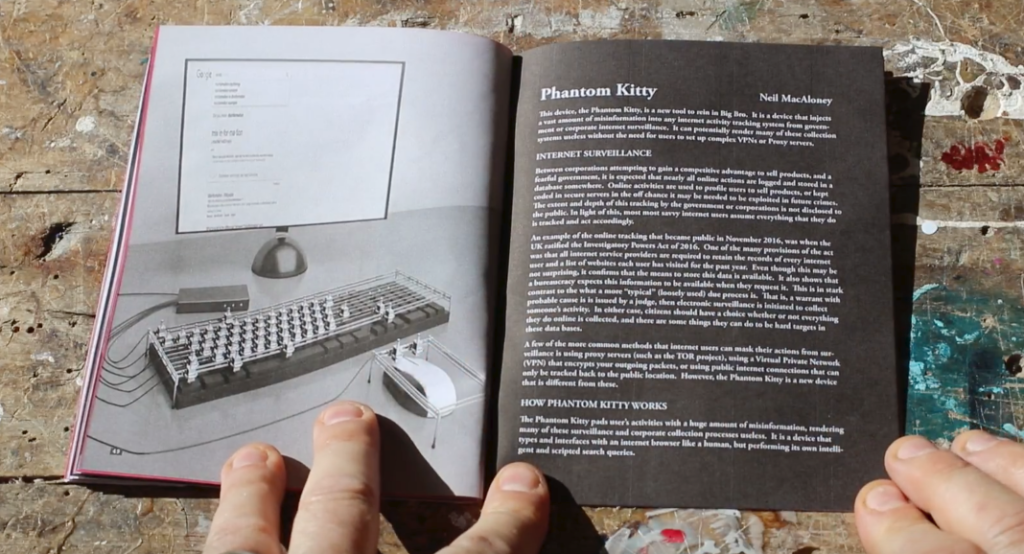

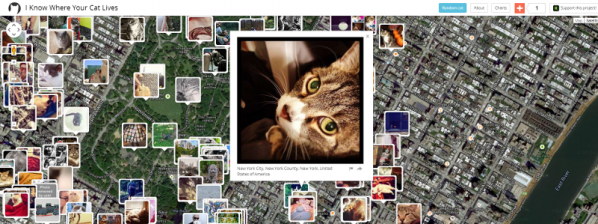

The book treasures the craft of DIY technology development, notably in the surveillance /privacy sector, and highlights the pressing need for knowledge in light of the technological advantage of those in power. Backlash provides us with an educational protest kit, including devices for off grid communication and bugging defence. These are functional but not necessarily designed for situations of conflict, rather for inciting a relevant debate among the general public. Phantom Kitty (work in progress) defies spying by authorities without a warrant and the enforced quantification of humans based on evaluations of online activity. It produces arbitrary noise when the user goes offline to obfuscate browsing habits and it is possible to integrate machine learning algorithms at a later stage, which could mimic or create identity patterns. Phantom Kitty features a stunning mechanical rack for keyboard and mouse operation, fed by a program executing search queries and the access of webpages. The project draws on the eeriness of neither knowing to what extent gathered data is exploited, nor against which parameters and targets it is set.

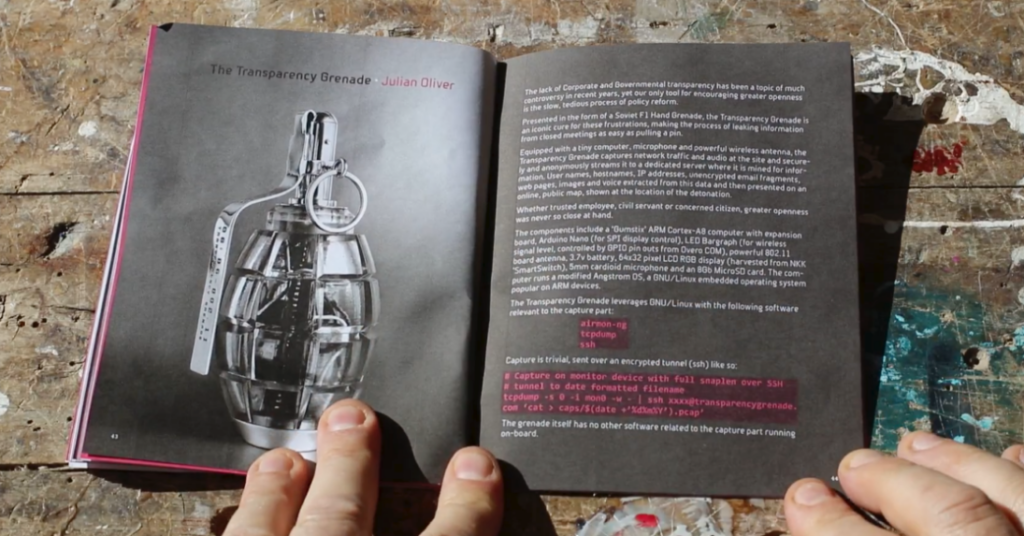

Completely left in the dark about the full scope of exercised control and entailing consequences The transparency grenade by Julian Oliver reminds us that citizens have a right to openness too. The promise of “making the process of leaking information from closed meetings as easy as pulling a pin” is tempting, and in contrast to the opaqueness of corporate and governmental policies, the artwork, other than claiming transparency, is representing it, in its aesthetics, open source software and in the thorough documentation of its engineering process.

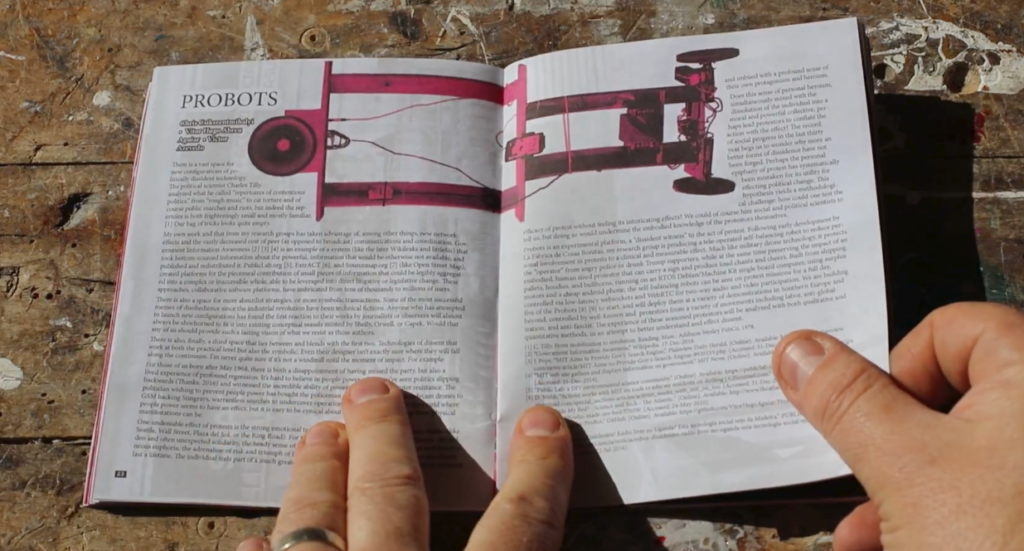

The well written accompanying text of one of my favourite projects PROBOTS describes effective works as “technologies of dissent that work at both the practical level but also the symbolic”, by all means valid for those involved making this book, albeit associating with a manifold of disciplines. The tele-operated protest robot certainly meet those demands and can be sent out by the precarious worker as an answer to the efficiency of contemporary policing, simultaneously a metaphor for the limited potential in the act of present-day corporeal protest. The silencing of political resistance happens far beyond the streets and PROBOTS makes an extraordinary research tool for investigating the organisational power of technology, which prevents social progress already from the outset.

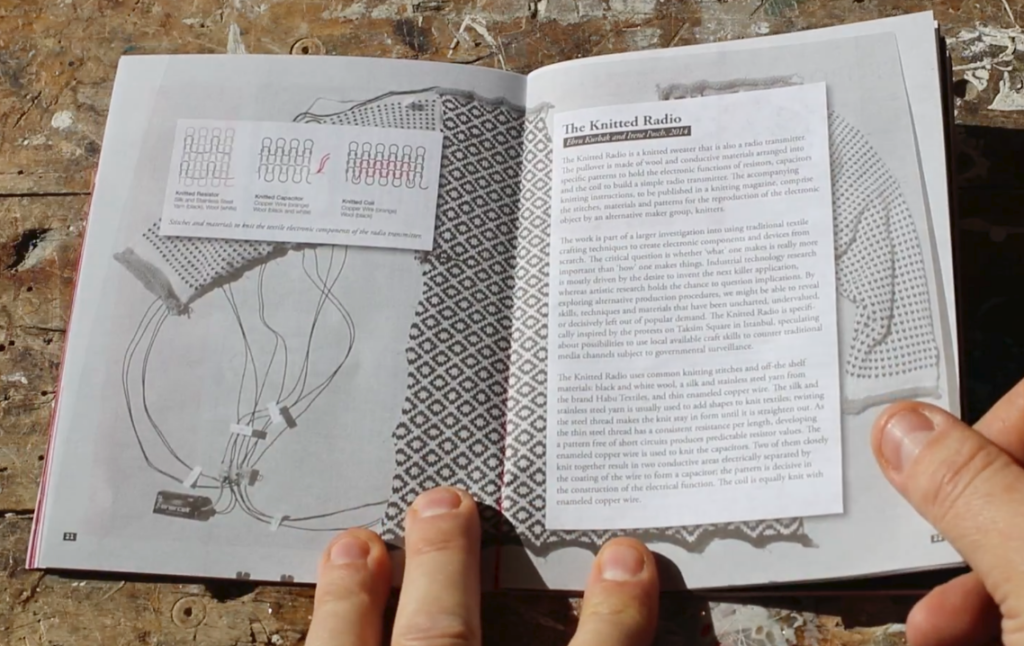

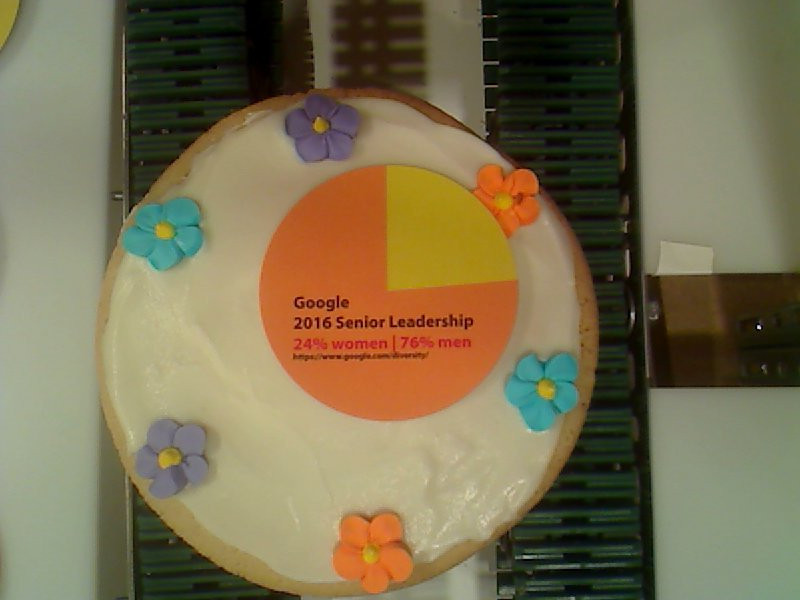

I’ve only recently discovered that e-textiles is not the same as smart clothing. It is a discipline, focusing on the act of making rather than the actual result, albeit in this case impressive too. The makers of The Knitted Radio approached the craft of knitting and electronics without economic reasoning, a factor which primarily informs the engineering process in industrial design. The liberation from conventional standards brought about alternative forms and methods, that is a sweater that also functions as a FM radio transmitter and the skill to knit electronic components /devices such as resistors, capacitors and coil with conductive yarn, an off-the-shelf material. The knitting instructions for the sweater are available online, it can provide a free of cost, independent communications infrastructure. The concept was inspired by the protests on Taksim Square, Istanbul, Turkey, and associated violations of freedom of speech. A Piece of the Pie Chart: Feminist Robotics by Annina Rüst illuminates gender inequity in form of a production line, which decorates edible pies with pie charts, depicting gender ratios in tech affiliated corporate or public organisations.

Women are generally underrepresented in tech related workplaces and users of the gallery installation can browse and choose between various data sets on gender in technology, e.g. computer science graduation rates, before an ensemble of household applications and semi-pro robotics sorts the cake. The mere visualisation of data was not radical enough, so the finished pie can be shipped to the institution of which data (and gender inequity) originates, and where it can be consumed accordingly. Women have to be content with the smaller piece of the cake, also symbolic for economic inequality and the missed out experience of working in tech. Rüst was not satisfied with the claim that women are just not interested in tech, and further qualitative research in feminist technology showed that women are rather put off by its hostile macho culture and that technological pedagogy simply failed to inspire girls.

Tweeted image of a finished pie. Source: https://twitter.com/PieChartRobot

The PROTEST issue lives up to its title and emphasizes on projects, which propose hands-on political action and intervention with society, not in terms of providing solutions but to spark much needed discussion and inspire disruptive technology. Disobedient Electronics follows the publishing project Critical Making, which comprised 11 issues, so there is hopefully some more to come.

Hi Shaina! Tell us about the genesis of CAMP? How are you part of it? Why are you called CAMP?

CAMP came together as a group in 2007, initially consisting of me, Shaina Anand (filmmaker and artist), Sanjay Bhangar (software programmer) and Ashok Sukumaran (architect and artist) in Mumbai, India. The intersection of our skills and different backgrounds created a vital spark in which to experiment with technology and ask deep questions about form and ways of making radical political work. We are called CAMP as we are not an artist’s collective (though we began as a collaboration with KHOJ which was an artist’s collective in Delhi, which you headed operations for) but we call ourselves a studio. In this process, we try to move beyond binaries of art vs non-art, commodity market vs free-culture and to build media for the future. Personally, it gives me the platform to eschew conservative approaches to documentary filmmaking with “the colonial male gaze.”

How did you decide to create new-media and be part of CAMP coming from a strong documentary tradition?

Oh, for that I would like to describe the response my younger self (1992-2004) had to making traditional documentaries. Travelling around India with my mentor, filming a documentary about life in villages for the anniversary of Indian independence, I described how they’d turn up in jeeps, find the subjects, and ask important questions for the nation. I became increasingly disillusioned by what I saw as the repeated orchestration of finding a subject, interviewing, zooming in, asking questions until the subject ends up crying. So, once while analyzing the relationship between filmmaker and subject I echoed the question hovering over so many discussions, “who speaks for the subject and from where?”

That’s when I decided that I had two choices, to either move into fiction which was perhaps less problematic, or to “stay with the trouble”, to let the problems drive the work into becoming something more in line with my politics. I also wanted to “trouble” the triangular relationship of author, subject and technology, so that it favored the subject more.

Very interesting! You mentioned Haraway’s “staying with the trouble”. Were you influenced by her work? Say more! I relate to that experience, having switched from working in Bollywood to doing social documentaries and now learning new-media art. So, what role do you think technology plays in fostering that relationship between the subject and the author and more importantly, how does it “favor” the subject?

Well, yeah. I feel influenced by her as a woman media-maker where I draw from her reflections on race, technology and gender. In CAMP’s work at various biennials, I have often felt that every part of the process of documentary-making had been deftly unpacked and put back together again to reflect vital contemporary political concerns within the actual structure of the work or even its distribution, not just its content. By that, I felt we succeeded in using technology to foster that relationship.

I find it fascinating that technology is not a toy or gimmick in your work but rather gives to access to places and people which traditional approaches to documentary wouldn’t. In this context, could you throw some light on the use of CCTVs in your work esp. at a time when they were increasingly being used as a tool for surveillance?

In our work Al jaar qabla al daar (The Neighbour before the house- 2009), we used CCTV cameras and set them up to film the houses where eight Palestinian families had been forcibly evicted and are linked to remote controls in new homes or refugee places where the families now live. We were then able to zoom and tilt the cameras to spy up washing or as they went about their business. The complexities of the power relations between the observer and observed are dazzlingly deft and agile, giving energy to the otherwise hopeless situation of displaced Palestinians in Jerusalem. We only hear their voices as they trace the lines of personal memory in their old neighborhoods or stalk the new inhabitants of their former homes with the remotely operated CCTV placed on nearby rooftops. We see soldiers training, Orthodox Jews going to prayer, a boy skateboarding, roofs, water tanks, a veranda built by their own families. Their bodies exert a ghostly presence on the very image we see onscreen as a small boy exhorts his mother to “zoom, zoom”– to spy on one of the new inhabitants leaving the house. But nonetheless through the active manipulation of this technology we had “captured” a settler.

Do you think technology facilitates a democratic or rather liberal exchange for the subject? Let’s say immersive technologies like virtual and augmented realities, which I’m interested in, blur the point of view of the author and the subject. What do you think?

The act of wrangling the technology to record the voices of the camera operators while simultaneously filming does create a power shift. For example, in our work, the Palestinian families may be physically invisible in the places they once lived, but their voices and ability to control how we see with even the crudest of cameras, exerts its own pressure. It acknowledges and celebrates the democratization of the camera and makes us question the veracity of all the other images we have seen about Palestine. We hear details about the neighborhoods, how the evictions happened through impossible laws or enforcements as the displaced families observe how the new families don’t clean the stairs or water the lemon tree.

Yes, I liked the use of the footage as a timeline for viewers to edit which led you to form Pad. Ma (Public Access Digital Media Archive) which I was a part of too, at some point. Interestingly, here at UCSC, I met and heard Bernard Stiegler who had long ago worked with annotating found-footage with his students thereby that puts CAMP in that discourse. Say something about that.

Well, for me, the most radical and exciting approaches to documentary were in the 60s in India. Since then, what has changed? Nothing here. CAMP’s work provides a sense of new possibilities as it steals back technology and puts it into that utopian discourse of Stiegler and others to shift our perspective closer to the subjects. By “troubling” the traditional methods of creation and dissemination it empowers both the viewer and the viewed with a fresh perspective.

Some of your work is about migrant population, home and displacement which strikes a chord with my interest in human-rights and immigration. Tell us about this work and its approach.

A privileged perspective into the worldview of another is contained in our work, From Gulf to Gulf invited by the Sharjah Biennial a few years ago.Yet again it is a document of a much richer process that began as an artwork/ community provocation/ friendship built over four years between CAMP and a group of sailors from the Gulf of Kutch in India. Initially CAMP produced radio programs culling material from sailors’ songs, conversations, phone calls etc. and later that evolved into a new-media piece that showed this totally different space in a radically fresh way. It is composed of footage of their journeys and extended selfie- films shot by the sailors on their long voyages, often accompanied by songs which they Bluetooth to each other.

Fascinating! Lastly, I’m keen to hear about what CAMP wants to do with technology next?

At any given time, CAMPwants to challenge the triangular relationship of author, subject and technology, thereby splintering the privileged gaze and our standard mode of perception. That’s our motivation behind whatever we have or will do.

Thank you Shaina for speaking as an artist from CAMP. It was great to talk to you and have worked with you all!

Alan Sondheim has been ploughing a very singular furrow through art, music, writing, philosophy and much else since the late sixties. On the occasion of his participation in the Children of Prometheus exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery we present here an interview conducted by the artist and writer Michael Szpakowski in which Sondheim gives a broad overview of his artistic formation, practice and philosophy.

Michael Szpakowski: I first came across your work through the Webartery mailing list in 2001. I remember being knocked out by your productivity, a productivity that seemed to be allied to an incredible intellectual curiosity and restlessness, resulting in in words, images, movies, music – I remember once you started making little programs in some variant of Visual Basic… All of these posted day in, day out, come rain or shine, to the list… And, obviously I preferred some to others and for anyone to follow every piece of work you made would mean doing little else with their lives, but the quality, the variety, of what you made was ( and remains) staggering.

I found this compulsion to make work both admirable and invigorating and I’ve followed your work ever since. I think I even once compared you to Picasso on DVblog because I couldn’t think of anyone working in art for the net (and every such description is problematic, I’ll ask something more specific later) who seemed to come anywhere near to that fecundity allied to quality too…

I think of this interview as a general introduction to your work for someone who maybe has only happened across it for the first time in the exhibition at Furtherfield so I’d like to ask, first of all, for you to give us a sketch of your intellectual and artistic formation and the milieu(x) in which you have worked (I mean right from the beginning – tell us what makes you, you!):

Alan Sondheim: Of course this is difficult to answer; I began with writing and around the age of 19, started making music as well, but I was always restless. The compulsion has personal roots, but also a desire to move into an environment, habitus, and explore its limitations and promises; in all of this, I’m concerned with the interplay of the somatic and consciousness on one hand, and abstraction, the inertness of the real, mathesis (the mathematization, structuring of the world) on the other. So there’s this dialog at the limits. My first production was a book of experimental writing, An,ode ; around the same time I made three recordings, two for ESP-Disk; this was around the late 60s. Clark Coolidge, the poet, was very important to me early on; I met him at Brown; he introduced me to Vito Acconci and shortly after, early 70s, I moved to NY, eventually SoHo in its heyday. I’ve never been a traditional artist/writer/musician/etc. but move among these areas; I’m concerned with what for me are fundamental issues of philosophy, body, and the world. I want to explore at the limits of what I’m capable of doing. How is consciousness in relation to the world? How is the world?

I’m driven to create daily; while teaching at UCLA, I made a sound film (16mm for the most part) a week for 37 weeks; they ranged from a minute to an hour in length and were forms of deconstructed narrative. Now online, I try to make a work daily in whatever medium, including virtual worlds of all sorts; I continue to try to push limits – what I call ‘edgespace,’ – the space where gamespaces/worlds begin to break down, and what then? (By ‘gamespace,’ I mean, literally the space of a game, where rules hold – for example chess or football. The rules may be consensual or enforced, etc.) This is deeply involved with the politics and somatics of these spaces of course, and on the political spectrum, I’m leftist and deeply pessimistic; I don’t see internet or social media as salvation of any sort, but as fundamentally neutral, extraordinarily adaptable to any number of usages. I’ve written on the differences at the finest levels between the analog and digital, areas like that usually taken for granted; what emerges is a kind of granularity situated within an obdurate real world whose biosphere is faltering deeply.

M: Although you are included in an exhibition in a physical space here the vast majority of your output has been presented on the net, usually in the context of one or more mailing lists. Could you say a bit about this. Was this a conscious choice or pragmatism or somehow both? Is there anything you particularly prize about the rhythm of work and presentation that comes with this kind of platform and has the eclipse of many of the old mailing lists with the rise of social media caused problems for you – have you tried to adapt to/utilise these newer modes?

A: It’s pragmatism combined with a desire to explore; edgespace teeters uneasily and tends towards what I call blankspace, where the imaginary exists – for example, the ‘heere bee dragonnes’ in unknown areas of early maps (I haven’t actually seen the expression, but it serves here). I present my work on Facebook and G+; I also used YouTube for a long time until I was banned from it.

M: Banned from it?

A: A long story that would take this too far afield…

I work well in presentation/talk/performance mode online and off. I believe in the depth of email lists of course. I do think my avatar work is really well suited to gallery spaces; I’ve had up to seven projections going at the same time. I’ve also performed live in virtual worlds or mixed-reality situations which are projected/presenced directly, and for a long time Azure Carter, my partner, and I worked with the dancer/performer/choreographer Foofwa d’Imobilite; the physicality of the work was amazing. And another aspect of what I do – what grounds me – is playing musical instruments, mostly difficult (for me) non-western ones; the instruments require tending and close attention. I tend to play fast. Most of them are strings, bowed or plucked; the music is improvisation. Recently I’ve been focusing on the sarangi, for example. And I’ve had something like 17 tapes, lps, and cds issued; the most recent is LIMIT, which was done in collaboration with Azure and Luke Damrosch, who did Supercollider programming based on concepts I’ve had about time reversal in real time – an impossibility in gamespace, but the edgespace is fascinating. The music products excite me; they’re out there in a way that my other work isn’t.

M: I remember when I first discovered internet art or whatever we want to call it (and there have been numerous quasi theological arguments about this) that there was an intense debate about whether the internet was a conduit or a medium – so many artist-scripters/programmer tended to rather look down on those who simply took advantage of the network’s distribution and dialogical properties (although I have to say that my view is that it was in this massive extension of connectivity that the real force of the thing resided – I remember being told in 2001 that moving image was not internet idiomatic which is amusing given the rise of YouTube &c.) Your work, certainly of the last 17 years or so, strikes me as being intimately tied up with the network and with the unfolding possibilities of new media but not necessarily in the sense that you work with the network itself to make objects, works and more in the second sense of the conduit…

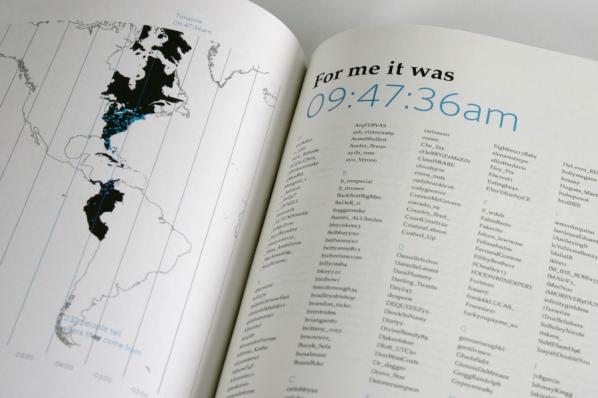

A: It depends; for example one of the projects I initiated through the trAce online writing community in 1999-2000 – over the hinge of the millennium in other words – was asking a world-wide group of artists, IT folk, etc., to map traceroute paths and times from the night of 12/31 to the afternoon of 1/1; the internet was supposed to run into difficulties – over timing etc. – and I wanted to create a picture of what was happening world-wide. A second project somewhat later was using the linux-based multi-conferencing Access Grid system to send sounds/images/&c. from one computer to another in the Virtual Environments Lab at West Virginia University – but these images would travel through notes, much like the old bang!paths, around the entire world. So, for example, Azure would turn her head in what seemed like a typical feedback situation – the camera aimed at a screen, she’s in front of it, the result’s projected on the screen, &c. – but each layer of the feedback had independently circled the globe (through Queensland to be specific), creating time lags that also showed the ‘health’ of the circuit, much like traceroute itself. It was exciting to watch the results, which were videoed, put up online with texts &c.

Part of the difficulty I have is being deeply unaffiliated; I need others to give me access to technology. For example, I’ve used motion capture in three different places, thanks to Frances van Scoy and Sandy Baldwin at WVU; Patrick Lichty at Columbia College, Chicago; and Mark Skwarek at NYU. I also did some augmented reality with Mark, and with Will Pappenheimer. To paraphrase, I’m dependent on the kindness of others; I have no lab or academic community to work among in Providence; what I do is on my own. John Cayley gave me access to the Cave at Brown; Eyebeam in NY (I had a residency there) gave me space and equipment to work with, and in both places I was able to create mixed reality (virtual world/real bodies) pieces – those also bounced through the network…

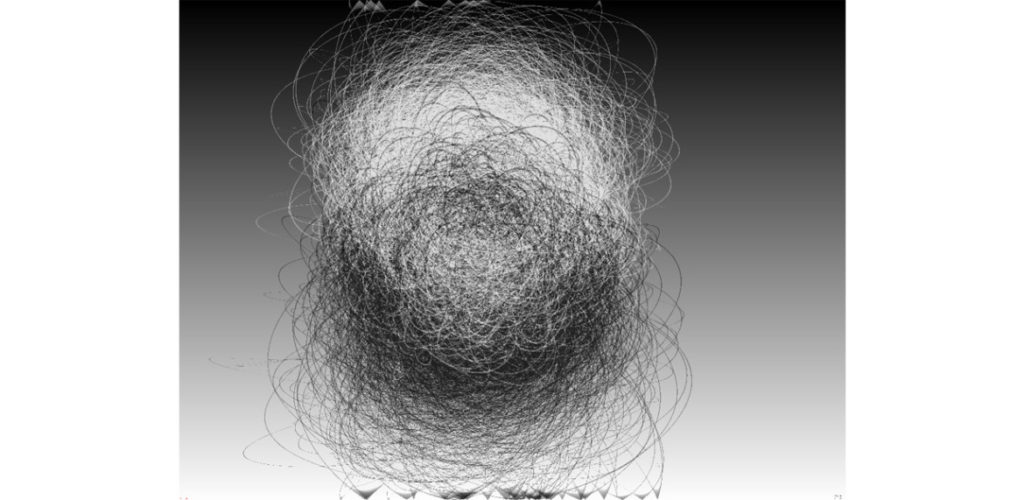

M: Could you talk, then, a bit about the motion capture/avatar work that seems to have been central to what you are doing over the last ten years or so. I also don’t think I’m mistaken in detecting a very decided move back to music making of late (I know this has always been there but it feels foregrounded again)

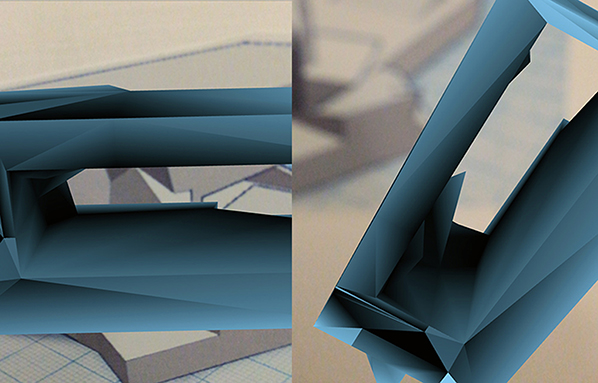

A: The mocap work has been ‘deep’ for me; it involves distorting the entire process, in other words distorting the somatic world we live in. There are numerous ways to do this; the most sophisticated was through Gary Manes at WVU, who literally rewrote the mocap software for the unit they had. I wanted to create ‘behavioral filters’ that would operate similarly to, say, Photoshop filters; in other words, a performer’s movement would be encoded in a mocap file – but the encoding itself during the movement itself, would be mathematically altered. Everything was done at the command line (which I’m comfortable with). The results were/are fantastic. A second way to alter mocap is by physically altering the mapping – placing the head node for example on a foot. But I worked more complexly, distributing, for example, the nodes for a single performer among four performers who had to act together, creating a ‘hive creature.’ All of this is more complicated than it might sound, but the results took me somewhere entirely new, new images of what it means to inhabit or be a body, what it means to be an organism, identified as an organism. This is fundamental. I’m interested in the ‘alien’ which isn’t such of course, which is blankspace. (The alien is always defined within edgespaces and projections; we project into the unknown and return with a name and our fears and desires.)

Most of what I do, for me all of what I do, is grounded in philosophy – ranging from phenomenology to current philosophy of mathematics to my own writing. So these explorations are also artefactual; I think philosophy is far too grounded in writing as gamespace; writing for me, when it’s touched by the abject, the tawdry, the sleazy, the inconceivable, opens itself up.

As far as music goes, I touched on it above in regard to LIMIT. One thing that concerns me is speed, playing as fast as possible, so that the body and mind move on de/rails that are at my limits; I think of this as shape-riding and the results and internal time dilations involved keep me alive…

M: You are genre/practice/technique promiscuous and you have a high level of skill in all –you could equally (and have been) styled Alan Sondheim ‘writer’ , Alan Sondheim ‘musician’, Alan Sondheim ‘maker of moving image work’ (with a marvellous sub-category ‘Alan Sondheim ‘maker of dance related video works’, for a while). Is one of these, in your heart of hearts, central, and, whether this is so or not, how do you place yourself in respect to the various traditions around these areas of work. How do you fit into the art world, into literature or the experimental film tradition? How do you relate to net art/networked art/new media &c.?

A: I don’t seem to fit into the artworld, net art, poetry world, music world &c. – it’s difficult for me to get my work around as a result. Nothing is central but a desire to see how systems form, coagulate, degenerate, collapse, become abject, &c. in relation to consciousness: How are we in the world? On a concrete level, finance enters into the picture; what can I do given a kind of lack of community around me? How can I push myself?

I’m not sure what ‘net art’ is, but certainly the Access Grid pieces &c. are of that, although not of Web-based protocols. There are so many ports out there to use! I do think of myself as a new media artist or someone burrowing into post-media. I’ve always had a few people who believe in what I do, who have helped or worked with me, and I’m really grateful for that. But in terms of institutions, I feel like an outsider artist and am treated like one. It came to a head for me years ago one day when I was living in Soho; I had a call from Vito who said he had realized that whatever I am, I’m not an artist; the same day Laurie Anderson spoke to me and said she realized that whatever I am, I am an artist. So my identity has been far more fluid than I’ve been comfortable with, and it’s affected my career. (There was that tape Kathy Acker and I made 1974, and I read an interview a few years ago, forget the source, with Edit Deak who said the tape wasn’t art at all; in the meantime, it continues to be shown at various venues.)

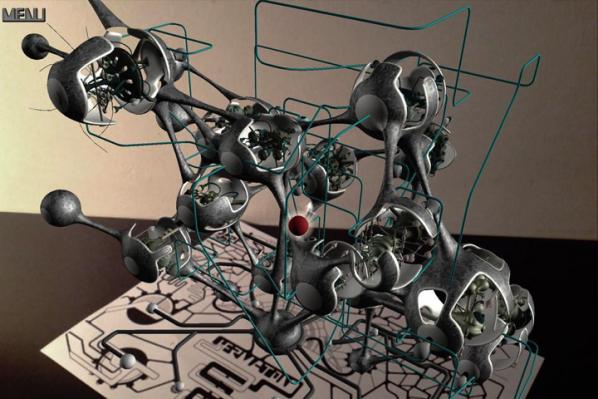

M: Finally, could you say a little about the work in this particular show?

A: The work in the show is a group of 3d-printed avatars distorted through the mocap process described above. For me they connect, deeply, with charred bodies, with anguish, with genocide and scorched earth. They appear also in number recent videos created in various virtual worlds, moving/performing etc. The anguish, so close to death and unutterable pain, is there. I’ve talked about the kinds of brutal killings occurring now worldwide, from Finsbury Park to the United States, the rise, not only of racisms, but violent nationalisms, in the U.S. certainly encouraged by the present regime. I’m sick of it. We all have nightmares. I want to understand this, this grounding in the blooded earth that shakes our very ability to speak, to think, to act.

And yet of course we must resist.

The work in the show is also critical, then, of technophilia, technological answers to the world, utopian dreaming. The top one percent benefit most from the results. I see utopian thinking as dangerous here. Our so-called president has his finger on 4000-5000 nuclear warheads. That’s the reality for me, and why I don’t sleep at night.

Michael Szpakowski: 聽琴圖 (listening to [Alan Sondheim playing] the qin), after Zhao Ji

// gravure, urushi lacquer & pigment on found wood // 30.5X7.5″

The productive alliance between instruments of computing techne and artistic endeavour is certainly not new. This turbulent relationship is generally charted across an accelerating process outwards, gathering traction from a sparse emergence in the 1960s.[1] Along the way, the union of art and technology has absorbed a variety of nomenclatures and classifiers: the observer encounters a peppering of computer art, new media, Net.art, uttered by voices careening between disparagement, foretelling bleak dystopian dreams, or overflowing with whimsical idealism. Once reserved for specialist applications in engineering and scientific fields, computing hardware has infiltrated the personal domain.Today’s technology can no longer be fully addressed through purely permutational or systematic artworks, exemplified in 60’s era Conceptualism. The ubiquity of devices in daily life is now both representative and instrumental to our changing cultural interface. Technologies of computing, networks and virtuality provide extension to our faculties of sense, allowing us phenomenal agency in communication and representation. As such, their widespread use demands new artistic perspectives more relentlessly than ever.

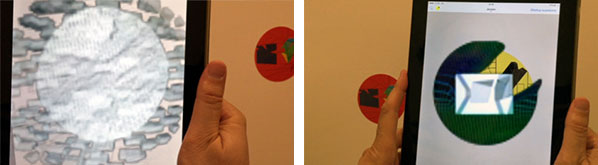

I, and no doubt many other academic observers, watched the Pokemon Go augmented reality (AR) game erupt into a veritable social phenomenon this year. The rapid global uptake and infiltration of AR in gaming stands in contrast to new media arts, still subject to a dragging refractory period of acceptance and canonization. Perhaps this is emblematic of a conservative art world that persistently recalls an ebullient history of computer art practices. In this lineage, many a nascent techno-artistic breach has been accused of deliberate obfuscation, of cloaked agendas under foreign (‘non-art’) orchestrations.[2] The seductive perceptual forms elicited through augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR) and immersive reality (IR) devices can be construed as mere spectacle, vulnerable to this type of critique. “Google Daydream” and “HoloLens” chime with a poetic futurism; cynics might instead see ready-to-wear seraphs veiling the juggernauts of Silicon Valley. However, the current groundswell in altered reality discourse may signal a divergence from such skepticism. One recent exemplar is Weird Reality, an altered reality conference that aimed “…to showcase independent and emerging voices, creative approaches, diverse and oftentimes marginalized perspectives, and imaginative and critical positions…. that depart from typical tech fantasies and other normative, corporate media.”[3] This is representative of the expanding, international trend towards artistic absorption of new media and technologies. It is a turn that emphasizes the potential for cultural impact, experimental daring, and even conjures the spectre of the avant-garde: radical transformation.

One of my PhD supervisors wisely admitted “…to stand out, the human artist must be more creative, diversified and willing to take aesthetic and intellectual risks. They can and must know the field they are creating in practically and philosophically, and confidence in their position and contribution to it is essential.”[4] Through this earnest lens, artistic production can serve as a conduit for ideas ranging from the speculative to the revelatory. In these divinations, we might trace a path through the sprawl of new media discourses, and find ourselves somewhere unexpectedly revitalizing. I hope to mark out some of this territory from a position of mediation. I want to invite art and art theory into an arena of uninhibited collusion, using critical writing to facilitate the exchange between digital media theorists and artistic practitioners in the most open sense. Furtherfield.org offers an allied platform for the aims of the Theory, Meet Artist [5] project, articulated here in an interview dialogue.

Originally published in The Fibreculture Journal, Edwina Bartlem’s 2005 article Reshaping Spectatorship: Immersive and Distributed Aesthetics proposes that immersive artwork practices have transformative potential. Across a range of modalities, these works can influence perceptions of ourselves and our extended digital presence in a variety of scenarios and configurations. Whilst participating in such practices, we are prompted to consider IR encounters as form of mediation around our human embodiment, subjective identities and cultural interactions. Bartlem touches on ideas of prosthesis and sensorial augmentation within these immersive experiences. Creation of a synthetic environment is posited as an opportunity for deepened self-reflexivity and awareness.[6] In parallel, a spectrum of narratives around the technologically adapted ‘post-human’ emerge. Their tone and reception hinges upon the artist’s individual performance in roles such as programmer, director, composer or overseer to such works.

Rachel Feery is an Australian artist interested in the intersection of visual art, soundscapes, video projection, experiential installations and technology. Her artistic practice explores alternate realms, the meditative headspace, ethereal imagery and immersive environments. For this interview, Bartlem’s paper is positioned alongside and in dialogue with Feery’s work, Clearing the Cloud.

Clearing the Cloud is described by the artist as “… a multi-sensory work inviting pairs to cloak-up, complete a circuit, and experience simultaneous mapped projections visible through a hooded veil. The artwork aesthetic draws from esoteric sciences and holistic health practices. The environment is intimate, quiet much like a room where one would go to receive therapeutic treatment.

Two participants at a time are invited to cloak up, remove their shoes, and step onto sensors on the ground to generate a circuit of light and sound. Starting with a ‘personalised scan’ followed by a projection of light and sound, all visible and audible within the suit itself, the individuals can either interact with each other or be still and silent. The robe, constructed of a semi-translucent, lightweight fabric with a soft skin-like texture acts as a supplementary skin. One’s field of vision is slightly inhibited by a lightweight mesh that both creates a screen-vision as well as the ability to see through it.”

Jess Williams: I first came into contact with your practice during your talk for Media Lab Melbourne in September this year. You chronicled your process, influences, past works and brought us to Clearing the Cloud. I was struck by the experiential intimacy of the project, and the immersive qualities that you deployed though staging it. In her paper, Bartlem suggests that participants in immersive practices cannot be immersed without being affected by the environment on perceptual, sensory, psychological and emotional levels. What kind of sensorium did you want to create for Clearing the Cloud, and did you contemplate the possibility of this type of affective influence on your participants?

Rachel Feery: In one sense, the project came about while I was thinking about art as therapy, and thinking about technology that has the potential to create a meditative space. The site of the exhibition, Neon Parlour, was previously a centre for healing and meditation. I wanted to create an intimate room that would reflect the building’s history. Speaking of the sensorium, I was drawing from esoteric sciences, looking at auras, and Reiki practices whereby chakras are ‘cleared’. This is all reflected in the visual and environmental elements of the work, but ritual aspect is key. It’s important for participants to enter the artwork through the process of putting the garment on. The ritual is something you have to experience with someone else, and there’s a synchronicity between the people who participate. If either person takes their feet off the sensors, the ‘therapy’ is reset. It becomes apparent that there’s a level of commitment to it, that there’s a trust involved. If one person backs out, the interaction stops and resets.Clearing the Cloud ultimately asks participants to commit and experience the work together. Some participants responded that they felt lighter, and that time had passed out of sync with the seven minutes that had passed in reality. I thought this was an interesting reaction when nowadays, our attention spans are said to be dwindling. I feel there’s something significant in a lot of those esoteric sciences.

JW: Bartlem maintains that immersive art offers more than pure escapism into a constructed simulacra. These types of artworks can also elicit a type of self-awareness or meditation on perception and one’s own agency in the prescribed environment. I’ve noticed a strong tendency to consider transcendence, or the superhuman, in many futurist discourses around technologies that interface with the human body. This spans augmented reality, virtual environments and may well capture less conspicuous (yet ubiquitous) examples, such as fitness metrics or geolocation of the self through GPS. How do you position narratives of extending or ‘hacking’ embodiment within your own work?

RF: There’s an aspect of being both physically present and also outside of yourself whilst engaged in Clearing the Cloud. As a participant, you find yourself looking through a meshed veil that’s being projected on, and if you adjust your focus, you can see coloured projections on the other participant. This dual, simultaneous vision got me thinking about the ways that newer technologies such as AR and VR can affect what we see and the way that we see. Essentially, those applications allow you to see an environment with a filter over it. You have the sense during the ‘clearing therapy’ of an outer body experience, which is something that certain types of meditation aspire to. Escapism can imply you’re ignoring what’s happening in the outside world and going inside yourself, or elsewhere. But technology is blurring these boundaries, becoming increasingly intertwined in everyday activities, both personal and shared. You’re not really escaping if there’s an application present to assist with something, provide new information, or an augmented experience. In that sense, I would agree that it’s not pure escapism. You’re in two places at once. I would say that the word escapism has darker implications, such as detachment and avoidance of reality over a virtual space. Meditation, however, is affiliated with deeper understanding of oneself, and acceptance and appreciation of both worlds. As technology gets more advanced, I think it will have the ability to do both.

I like the idea that two people willingly participate in this scan and projection without question. I feel it relates to this influx of new technology applications that are free and that everyone’s willing to try. On the darker side, I wonder about the consequences of giving away information- effectively, parts of yourself- to participate in the unknown. I also like the idea that Clearing the Cloud is presented as a holistic therapy, a gesture of removing the build-up of accumulated information, or as protection from the data mining we’re exposed to through technological interfacing. We’re made vulnerable to hacking, but in a sense it’s not really hacking anymore, it’s just collecting what we’ve been giving. There’s such a rush to use new applications and technologies but everything is untested. Essentially people become trial subjects through their willing self-disclosure.

JW: You mentioned David Cronenberg’s 1999 film eXistenZ as a formative influence in your creative development. Underpinning the science fiction and horror themes, a specific abject revulsion is reserved in this film for prosthetic extension and modification to the human body. Could the veils (with their accompanying perceptual experiences) used in Clearing the Cloud be viewed as a form of sensory prosthesis?

RF: I would say I was more interested in the idea of accessorising tech, rather than prosthetics. I am drawn to the way that Cronenberg’s characters leave their physical body and enter another state, but again, this is quite geared towards escapism. Using the veils arose through researching a mix of religious and medical robes, futuristic fashion and science-fiction inspired fashion. They all seemed to be white. There’s also a relationship with the cloak to other forms of wearable technology. I’m interested in this – in Google Glass, VR headsets, and related items – as both a current fashion trend and also as a subtle way that technology encroaches on our day to day lives, present as we move through and see our worlds. While I perceive the cloak itself is not so much of a prosthesis, there are certain physical qualities of the material that feel both organic and synthetic. They’re made of a foggy, PVC translucent plastic: when worn, this fabric feels like a skin. The backwards-oriented hood also functions as a way to obscure the face, and presents a form of anonymity that is ultimately within the concept of ‘being cleared’ and ‘regaining yourself.’ There are other associations too: of a uniform, of being part of a community that has been cleared, or erased.

JW: Typically, when audiences are presented with new media or computer mediated artworks, they have limited access to the operational interior of the encounter. Whilst it can be argued that more traditional media or installation works also don’t completely disclose their construction or authorship, new media practices seem subject to increased scrutiny and distrust around how- and to what end- they operate. In her paper, Bartlem proposes that instead of masking the presence of technology and interface, immersive artworks tend to overtly emphasize the synthetic artifice of the experience. In regards to revealing the hierarchies of control implicit in executing works like Clearing the Cloud, how much do you wish the audience to have a certain ‘privilege of access’? For example, do you consider it necessary to directly reference programming script, hardware circuitry, or technologies of surveillance?

RF: The actual technology used in the exhibition was not necessarily about aesthetics. Hardware and devices, such as projectors and Raspberry Pis, were not elements that I wanted audience attention drawn to. Moreover, I think if you give spectators interior access, it can take away the simplicity of the art experience. The most that I would give away would be the materials visible or listed in the artwork. I actually tried my best to mask the technology, hiding cords and mounting the projectors up high to make it feel innocuous and to minimise its physical presence. Once people can identify familiar tech, there is an immediate undermining of mystical impact. For this artwork, I worked with artist and technologist Pierre Proske to write a code that triggers the projection once the sensor pads are activated. The hardware elements are present, but they’re definitely not the focus. Rather, it’s the experience itself, the meditative space created that participants are made most aware of. I think that’s why auras, and energy healing, are so fascinating: they rely on people’s ability to embrace and believe in the healing process, which in turn requires any distractions or doubts to be removed- or at least obscured. Obsfucation was deliberately built into the back-to-front hoods used in Clearing the Cloud. Restriction of the visual frame of reference was intended to encourage immersion in the experience.

JW: As we’ve discussed, the eponymous gesture of “clearing the cloud” reads as recuperative, meditative, and somewhat subversive towards strategic or commercial use of new technologies. This is a position that Bartlem suspects is endemic within artistic instrumentalisation of these types of media. Do you feel a sense of alignment with a more radical manifesto in new media practice?

RF: A lot of my ideas draw from or relate to concepts that have been proposed in science-fiction films… science-fiction is radical. Sci-fi extrapolates the current social, political or technological trends, or explores alternate models. Clearing the Cloud also proposes a need for something that hasn’t quite been quantified, a therapy to restore and protect from encounters with technology. Clouds traditionally connote lightness, and formlessness, but today they weigh heavily on us in a digital data context. We carry more and more information, and give more and more of ourselves. We’re now clouded by our metadata trails, and it’s radical to think that a therapy can address this, and return us to a state of clarity, in a literal and metaphysical sense.

JW: After your talk, I asked you a question around whether Clearing the Cloud‘s artistic narrative could function beyond a ‘closed-circuit’ proposition. Whilst Bartlem scopes immersive and telepresent practices in her paper, she doesn’t directly address works that hybridise the two concepts. She frames telepresent artworks as those that link participants from distant locations, precipitating notions of networks and a multi-user participation within art. How would a multiplicity of network relations impact on a scenario like that you have staged in Clearing the Cloud?

RF: An excellent question, and very relevant to the nature of the work. The participant’s experience centres on a propositional ‘defrag’ of their personal hard-drives, regaining clarity, allowing independent thought free from the prison of past browsing histories and metadata maps. Those in a networked community also benefit from this speculative process: the more persons ‘cleared’, the stronger the authentic connections would be. If you were to be ‘cleared’, and your online history erased, the persons closest to you would also need to be erased in order to completely eliminate any trace of you. It’s like a chain reaction. Although only two people might be scanned at a time, for a complete ‘clearing’ you would need the eventual interfacing of everyone you’ve ever come into contact with. Ideas around utopias were intrinsic to the development of Clearing the Cloud. In one view of the work, those people who have been ‘cleared’ became part of a separate, even sanctified community. This meditation was idealistic, borne of the desire to find a way to protect our identities and those of our networks when they are potentially threatened or compromised by interactions with technology.

Clearing the Cloud was originally exhibited in 2016 as part of This Place, That Place, No Place curated by Irina Asriian (Chukcha in Exile) at Neon Parlour, Melbourne, Australia.

Feature image: Still from Dreams Rewired: original source Das Auge der Welt (Germany 1935); dir: C. Hartmann

Dreams Rewired / Mobilisierung der Träume – Trailer from Amour Fou on Vimeo.

The 2015 film Dreams Rewired, recently shown at the Watermans Digital Weekender in London on 12-13 November, will be screened again at Watermans on 3 December. Directed by Manu Luksch, Martin Reinhardt and Thomas Tode, the film has the tagline ‘Every age thinks it’s the modern age’. It looks back to the early 20th Century, to the development and implementation (first locally, then globally) of the telephone, the radio and television.

The makers of Dreams Rewired unearthed and arranged early film recordings and brought them into the 21st century context. This was done via a playful narrative written by Manu Luksch and Mukul Patel and read by Tilda Swinton. The tagline was well chosen; almost everything Swinton says would have been relevant at almost any point within the last century. Time periods, machineries and political movements are connected in clever and unexpected ways, meaning that Dreams Rewired, a durational video whose narrative follows a recognisable storytelling structure, makes numerous links between times, places and people, which branch off from the safety of its linear structure.

Dreams Rewired is something of a treasure trove, not only for the glimpses its found-footage building-blocks gives into a past era but also because of the inter-generational, inter-national, inter-thematic connections it makes. Frequently while watching the film I felt the urge to burrow into an investigation of one of the clips, stories or introduced contexts. To emulate this ‘tip of the iceberg’ effect, this review will pull words directly from the film, linking quotations to some of the themes which appear and reappear throughout.

“A new electric intimacy”

With new media come new practices of communication. One of the recurring themes described in Dreams Rewired is the coupling of intimacy and invasion of privacy introduced to society along with a new communication method. Just as a new invention is prototyped, its social implementation causes new prototypical behaviours – new ways of caring, new ways of injuring, new comings-together, new separations. Uncertainty is inherent to experimentation.

“The waves travel at the speed of light, defining what simultaneous means. Information can travel no faster.”

When something is newly possible it also newly achievable – new precedents are set and new avenues opened for exploration. There is a flurry of activity, a rapid diversification. For those looking to gain or retain power over others, this is a problem; diversity requires more effort to manage. Initial flurries of activity are curtailed by the introduction of rules, the setting of precedents.

This limitation sets new targets to meet, new challenges to overcome. The cycle starts again as those in power look for ways to consolidate it while those without look to gain what they can. This is a simplistic, but not inaccurate, description of the machinery of the capitalist world.

This cycle of diversification and restriction is always coupled with the establishment and transcendence of thresholds. Experimentation with a new technology reveals some of its limits. (Side note – of course, what is understood as a limit is defined by wider cultural contexts.) “Information can travel no faster” is a provocation to speed up.

“Geography is history”

New advances cause conceptual shifts. Early telephony and television shrunk the gap in time between a thought or plan and its activation. Understandings of time and geography changed, and it became possible to move into new spaces and in new ways at socially impressive speeds. New powers, in short, were available to those who knew how to access them, to those who understood the preceding context well.

“A model of the new human is put into circulation”

A network grows, its complexity and partner processes intensifying. The machinery of daily life is altered, and daily life is a testing ground. Social interactions change as the new set of behaviours required to work the new machinery collide with existing social norms and rituals. New jobs and new workplace structures appear and people previously without responsibility or power find themselves in contact with it (though they may not understand the possibilities at first). People are no longer the same beings as before. Cycles of experimentation and consolidation reach into the body.

“Someone will have to lift us up. But who will lift them up?”

The flurry of excitement surrounding a new invention is based on the idea that ‘our’ lives will be improved, that ‘we’ will be able to do, see, have more. There is a problem here. The words ‘we’ and ‘us’ are too abstract – they bracket whoever the speaker wants them to bracket and recapitulate the prejudices they have. Anyone who is not included as part of the ‘we’ simply does not exist. This is convenient for the ‘us’ – while ‘we’ rush excitedly towards a future in which we have more and better, what ‘they’ do is of little concern. The ‘us’ does not care – or even think much – about the ‘them’. The ‘us’ cannot understand why the ‘them’ has not joined the ‘us’. After all, the ‘us’ is at a new threshold – who would not want to reach the other side?

“Personal profiles, passwords, biometrics..fully documented. Every trace filed. Bigger data, better analytics. Opt out, and we lose our place in the world. So…we share the keys to our desire, our habits, to ourselves.”

To be part of the ‘us’ and the ‘we’ requires effort. To ‘opt in’ requires sacrifice. At the same time, ‘opting in’ is the easiest thing in the world when ‘opting out’ means facing a void. Advice on how to do well, how to achieve, how to be healthy is easy to come by, but there is little guidance for those who find themselves, or wish themselves, outside the mainframe. Losing one’s place in the world means losing access to that mainframe and the stability that comes with a highly legible structure. Today the legible structure is far-reaching and well established, to the extent that opting out is dealt with violently. The new models of human coming into circulation have trouble recognising the old. There is a mutual rejection.

“Government regulation stifles amateur culture – military and commercial interests occupy most of the spectrum … transmission becomes a privilege, not a right”

As I wrote earlier, the ‘us’ and ‘them’ structure is too simple. It would be more accurate to think of people as communicating on multiple frequencies. The machinery of society is complicated to say the least, and made more so by the mainframe, which amplifies transmissions at some frequencies while restricting others. In the early 20th Century, multiple obscure radio channels were repressed, responsibility placed with public backlash following rumours that amateur radio was responsible for the sinking of the Titanic. Side questions: where did the rumours come from? What were they based on? How was the public response measured?

“For the first time he hears himself as others do. A voice absolutely familiar but estranged…But her power also grows: by controlling his voice she controls her time”

There is a strange relationship between the controller and the controlled. For every CEO there is a team whose own agenda seeps into the workings of the company. Dislocated power and fragmented or unplaceable identity are some of the symptoms of a complex system undergoing change. When a system is so complex as to involve multiple timescales, spaces, materials and structures, it is impossible to predict the future.

—

Dreams Rewired is part of the Technology is Not Neutral Symposium

3 December 2016

Watermans, London

https://www.watermans.org.uk/events/technology-is-not-neutral-symposium/

Featured Image: Ubermorgen, “Vote-Auction”, 2000. Installation view from the exhibition “Whistleblower & Vigilantes”

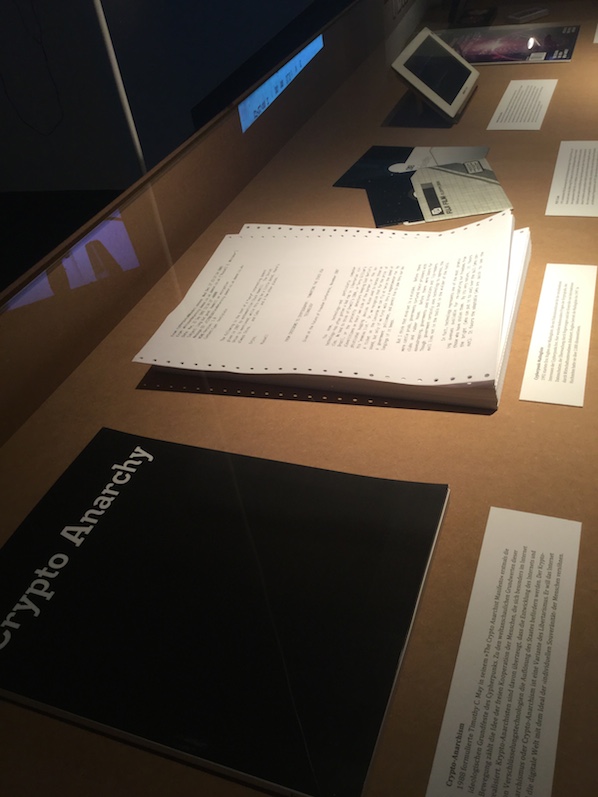

It has been a long time since an exhibition shocked and confused me. In fact, I cannot even remember when it last happened. Yet the exhibition Whistleblowers & Vigilanters has managed to do just that. Curators Inke Arns and Jens Kabisch of the Dortmund art institution Hartware Medienkunst Verein (HMKV) have put up a show in which complete nut cases are presented side by side with political activists, artists and whistleblowers a la Edward Snowden. This makes the exhibition ask for quite some flexibility from the audience. Visitors have to work hard in order to understand the connection made here between, for example, racist conspiracy theories expressed through YouTube videos and the ordeal of a whistleblower like Chelsea Manning.

The very short introduction text to the exhibition guide is part of the puzzle we are presented with. The basic premises of the exhibition are explained in what I think is not the best possible manner, because it leaves out any mentioning or analysis of the huge political differences among the people and works presented. At the same time the use of words like higher law and self-legitimization easily creates a feeling of unease about each practitioner or type of activism in the show:

“The exhibition asks what links hacktivists, whistleblowers and (Internet) vigilantes. What is the legal understanding of these different actors? Do they share certain conceptions? Who speaks and acts for whom and in the capacity of which (higher) law? Among other issues the exhibition will examine the differing legal conceptions and strategies of self-legitimisation put forth by activists, whistleblowers, hackers, online activists and artists to justify their actions.”