As curator of the exhibition Monsters of the machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century, I thought it necessary to interview the artists in the exhibition, while it is shown in the magnificent gallery space at Laboral, in Spain, until August 31st 2017. I wanted to get more of an idea of how they see their work in the show relates to the core themes. Mary Shelley’s book Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, has been interpreted in numerous ways since was written in 1816, and then published anonymously in London in 1818.

Eugenio Tisselli is a Mexican artist and programmer. He is a PhD candidate at Z-Node, the Zurich Node of the Planetary Collegium. Previously, he worked as an associate researcher at the Sony Computer Science Lab in Paris and was also a teacher and co-director of the Masters in Digital Arts program at the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona. In his role as director of the ojoVoz project, he has carried out extended workshops with small-scale farming communities in different parts of the world. The ojoVoz project may be accessed at http://ojovoz.net. His personal projects may be accessed at http://motorhueso.net

Marc Garrett: Can you explain how and why the Sauti ya wakulima, “The voice of the farmers” project came about?

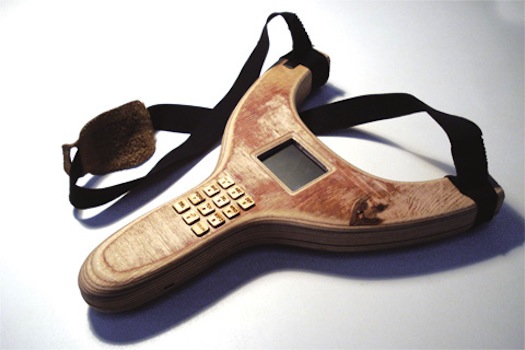

Eugenio Tisselli: In 2010, I came to realize that the way we feed ourselves is actually one of the main drivers of the accelerated destruction of societies and ecosystems that is currently underway. I felt like I had been living in La-La-Land before the veil was ripped off. My life changed radically. At that time, I was collaborating in the megafone.net project which had worked since 2004 with several groups of people at risk of social exclusion in different parts of the world. By offering an unfiltered communications platform, consisting of mobile and web applications, the megafone project tried to help these groups to make their voices widely heard. But, in 2011, I left the project with the purpose of offering its tools and methodologies to farming communities who wished to seek recognition and explore different forms of communication.

The first opportunity took shape in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, where a group of farmers expressed their interest in trying out these tools. I came in contact with this group through a scientific project that studied the direct and indirect effects of climate change on agriculture. The original goal of ‘Sauti ya wakulima’ was that the farmers would use smartphones and a web application to create a collaborative, audiovisual knowledge base of weather-related events, such as droughts, floods or crop diseases. However, the farmers eventually discovered that they could reshape this goal, and started to use the phones to interview other farmers with the purpose of creating a network of mutual exchange of knowledge about agricultural practices and techniques.

Episodes of fruitful learning have happened since then: one farmer learned the proper way to grow maize thanks to a picture taken by one of his colleagues. Another one learned a clever way to build chicken sheds during a trip to an agricultural fair. He took pictures of the sheds and when he came back to his community, he formed a cooperative for chicken production together with three of his colleagues. I could go on, but the project is still active after six years and that is probably the best thing that can be said of ‘Sauti ya wakulima’. It is alive because farmers find it useful, and it’s inspiring to learn from them that the mutual exchange of knowledge can become a key to a more resilient and interesting life. To me, the agricultures depicted in the photos posted by the Tanzanian farmers are not echoes of ‘the past’, but pathways to the future.

MG: What particular themes in the exhibition do you feel relate to the “The voice of the farmers” installation?

ET: I imagine ‘The monster in the machine’ not as a horrible, threatening ghoul, but as a weird and tricky creature made of language. The ‘body’ of this creature is made up of what we would call ‘principles’, ‘values’ and even ‘ideologies’. And it silently lurks inside the technological artifacts we use every day. The smartphone, for instance, epitomizes the ideal 21st century citizen: a self-sufficient, competitive and efficient individual. And, indeed, the monster that lives inside our smartphones is made of those values: its presence is inscribed in the device’s circuits and from there it casts its spell. What I mean is that technologies are not neutral. They are not empty: they are haunted by whispering ghosts.

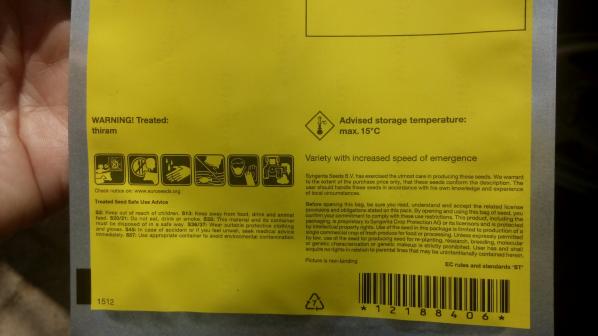

If you look at technologies used in agriculture, you will also find a multitude of monsters that softly dictate from the insides of things. Perhaps not by coincidence, genetically modified (GM) seeds speak the same things as mobile phones, only with different words. They tell farmers: “stop sharing seeds with your community, it’s a waste. Become an entrepreneur, there are shitloads of money to be made! Buy me! I’ll make you rich!” The sad thing is that these words are a trap: farmers ultimately become entangled in monetized loops that are beyond their control. Desperation sets in and, in absurdly horrible cases, such as GM cotton farmers in India, suicide becomes the only exit. But there are, indeed, other exits.

It is possible to rewrite the values and ideologies inscribed in technologies, in order to make them speak words that will do less harm. This is one of the key components of Sauti ya wakulima. From the very beginning of the project, the farmers agreed to redefine the smartphones as communal tools for collaborative documentation. They still share them and, when it is someone’s turn to use one, that person knows that she will not be taking pictures and recording sounds with a personal device, but with one that belongs to the group. These dynamics of sharing can create or strengthen reciprocal bonds. Renalda Msaki, a farmer who participates in Sauti ya wakulima, once said that the project had brought the group closer together. When I reflect upon her words, I can see how the monster in the machine can be transformed into a gentler creature that, nevertheless, remains weird and tricky.

MG: What role do you think the artist has when dealing with questions such as Monsters of the Machine exhibition?

ET: I think the artist can take up an incredibly vast range of roles when dealing with machines. But, whatever one does, one shouldn’t be naive about technology. Happily, the times when media artists created huge and complex pieces filled with little technological wonders just because it was exciting to celebrate their ‘magic’ is (almost) over. I used to say that (most) media art was the smiling face of techno-capitalism. Now I would add that, while technology was generally understood as a mediator between us and the world, it has now become a vector that uses humans to create its own mediations with the world. The roles have shifted, and things have taken a perverse turn. There’s a growing chorus of techno-objects that insistently asks us, humans, to drill the Arctic, build pipelines, burn coal, destroy forests and dig up more minerals. And we obey: we must feed the monster. Artists who approach technologies as materials to play with need to be aware of these power relations. We must acknowledge that technologies of all sorts have become overpowering actors that like to command.

Tisselli warns us that we need to be more aware of our responsibilties when implementing technologies into the environment. An important factor of the exhibition was to bring about a vision where the art was not just one type of art. This means different engagements in how we see and work with technology, are reflected as part of its context. Also, technology is not only a human skill, ’21st century scientific studies indicate that other primates and certain dolphin communities have developed simple tools and passed their knowledge to other generations.'[2]

As I write this conclusion, ‘Trump is poised to sign an executive order that will dramatically reduce the role that climate change has in governmental decision-making. The order could impact everything from energy policy to appliance standards.'[3] We live in a time where US policies are written via Twitter, and the rich are typically risking ours and the world’s future for their own ends. Tisselli and the farmers, remind us that, we need to be connecting with the land once more. We need to reclaim the soil before it is lost forever.

Mary Shelley’s distrust of the patriarch in the form of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, is as relevant now as it was 200 years ago. ‘Her portrayal of Dr. Frankenstein as an egocentric obsessive who will stop at nothing until he completes his mission in bringing his creature to life; represents man’s blind quest in pushing on until the precarious end, at whatever cost.'[4] Tisselli echoes this with his own critique towards artists working in technology. If we are to rethink what innovation can be now, what would that look like if we were to update it in a way that included indigenous voices, other levels of equality, and practices beyond what now seems like tired, machismo, and over obsessive, tech-enchantment?

The ‘Monsters of the machine: Frankenstein in the 21st Century’ exhibition is on at at Laboral, in Spain until August 31st 2017. http://www.laboralcentrodearte.org/en/exposiciones/monsters-of-the-machine

Those involved in the Sauti ya wakulima / The voice of the farmers project.

The farmers: Abdallah Jumanne, Mwinyimvua Mohamedi, Fatuma Ngomero, Rehema Maganga, Haeshi Shabani, Renada Msaki, Hamisi Rajabu, Ali Isha Salum, Imani Mlooka, Sina

Rafael.

Group coordinator / extension officer: Mr. Hamza S. Suleyman

Scientific advisors: Dr. Angelika Hilbeck (ETHZ), Dr. Flora Ismail (UDSM)

Programming: Eugenio Tisselli, Lluís Gómez

Translation: Cecilia Leweri

Graphic design: Joana Moll, Eugenio Tisselli

Project by: Eugenio Tisselli, Angelika Hilbeck, Juanita Schläpfer-Miller

Sponsored by The North-South Center, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology – Zürich

With the support of The Department of Botany, University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM)

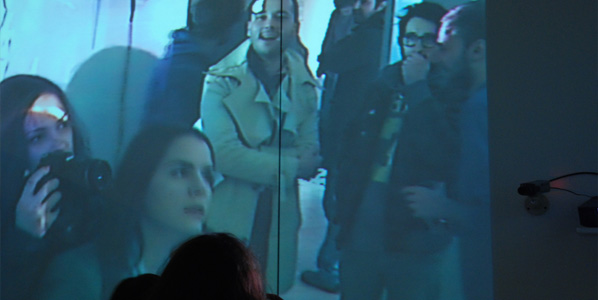

The Delfina Foundation selected Jean-Paul Kelly to undertake a residency in winter 2015. During his residency, Kelly regularly attended the City of London Magistrate’s court in Central London as a visitor. For eight weeks, he observed the routine events and procedures that took place in the courtroom. The UK’s Criminal Justice Act prohibits any form of documentation within the courtroom, whether it be a sketch or a recording, and only allows illustrators to take notes, most likely in the quick and loose form of stenography.

The absence and overall restriction of documentation within a courtroom (and beyond) leads to the fairly obvious skewing of narrative events. Kelly, who works with found photographs, videos and sounds originating from documentaries, photojournalism and online media streams, realised that the particular restriction was advantageous to the concept and the production of his new work, That Ends That Matter. For him, lack of evidence or documentation of a specific event elucidates a direct relationship between physical materiality and subjective perception of each individual.

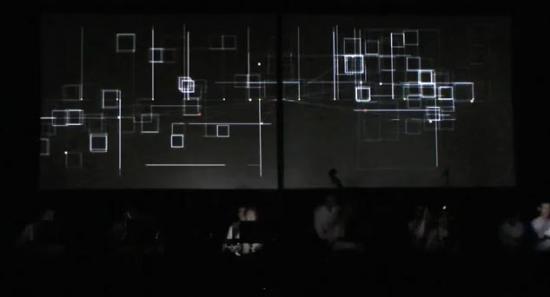

Such situations, in which evidence is lacking, fabricate image representations based on a very unreliable form of intangible reflection and recollection as both shared and personal memories. In our day and age, information is as effortlessly accessible as the Evening Standard on the Underground. However, within the courtroom, a place of supposed honesty and acknowledged transparency, the lack of documentation is paradoxical and challenges the sovereignty of such proceedings. That Ends That Matter is an eight-minute, three-channel video acting as a subjective reproduction of the events Kelly witnessed at court. One video re-enacts the court proceedings, another shows a constant photographic image stream as a retelling of the events and the remaining video acts as a visual soundtrack animation made out of geometric shapes.

Initially walking underground into Delfina’s bunker exhibition space, the viewer is confronted by the loud noise coming from the visual animation. To the left of the space, two screens are paired together – the image stream with the animation – and to the right of the space, the re-enactment stands alone. Encountering three screens, viewers may feel bewildered as to how to view the work, however, after a bit of floating, it becomes quite apparent that viewing order doesn’t really matter as each visitor finds their own. Some focus solely on the paired screens, others on the lone screen, and some sit against the wall and view the two screens (image stream and re-enactment) of the two spaces from the side together.

The re-enactment screen video begins, and a soothing female voice sets the tone for the three-channel video:

‘Excuse me, are you appearing before us today? No? Alright, so you’re here as an observer then? Okay, thank you. Welcome… Now we’re going to switch on some noise so we can discuss the matters properly.’

White noise immediately becomes a means of blocking transparent communication, in turn emphasizing the notion of skewing memory and representation of factual information. The re-enactment is played around a table, whereby the actors appear to be waiting around, lingering and passing the time. Although the scene is filled with white noise, none of the participants are talking to each other and there is a particularly eerie focus on an old man who keeps caressing the table with his finger – he soon looks up at us. The environment itself is immersive; the longer the viewer stays with them and observes, the more explicitly the viewer’s presence is felt by the actors. Presence is noticed and through direct and uncomfortable staring at the viewer, it is implied that the viewer’s observation is not wanted. The viewer is thus inclined to move to the left space and look at the other two screens.

Kelly uses a series of motifs and shapes interacting with the tactility of the artist’s finger or palm in order to establish image representation. When the visual animation screen shows a circle and emits noise, the image-stream presents a finger hiding a specific aspect of the photograph. When it is a square or a rectangle, it is usually a palm that hides a part of the photograph. Tactility in an immovable image stream represents an abstraction towards the idea of transparency. The artist’s hands touch, caress, hide, rub, caress and thus at times become overtly sexual when corresponded with homoerotic images – the hole becomes a motif frequently expended. The motifs of tactility cover people’s faces, acts of violence found in protests, and various scenes of despair. Here, tactility not only acts as a way of forming a temporal moment of surrealism, but also as a method by which one can learn how to connect to the images one sees, much like children touching things for the first time. The white noise itself, from being disturbing becomes soothing and harmonious with all three screens.

Smoke acts as another motif in images the viewer is shown. In a photograph where protesters are suffocated by teargas, the solution to the pain is pouring milk over your face, another act of blindness. Smoke becomes recurrent, and in the final frames of both the image-stream screen and the re-enactment screen, smoke presents itself with vigour. Smoke appears in the court of the re-enactment screen, and simultaneously, the sound stops altogether as the figures disappear in the haze.

That Ends That Matter’s representational strategy is based solely on memory and subjectivity as its response, much like the creation of human memories. To a certain degree, Kelly’s work embodies apophenia, a way of drawing connections and conclusions from sources that have no direct correlation other than their lasting perceptions – a spontaneous connection. It’s about communicating signs and non-objective matter, behaving in a way that strives to avoid both nostalgia and emotionlessness in order to question indexical notions of ethics in matters of transparency. Kelly may be asking, is abstraction fairer?

All images by Tim Bowditch, courtesy of Delfina Foundation.

“…the futility in this case is underscored by the silly project of bringing forth by mechanical means what nature in any case provides in abundance”1

Visitors to Annette Barbier’s Casualties at Chicago Artists Coalition are confronted by an abundance of dead birds—splayed photographs of birds that nature did not provide any instinct for dealing with gigantic, human-made structures of glass and concrete. Inside these structures are people who have no time to question whether they have any instinct for the same. Barbier’s installation is the intersection of these two sets of animals. Past the short foyer of dead birds, visitors are stopped by a large curtain of feathers without apparent opening. The curtain is lit from behind, flickering. It would be easy to stop here, assuming this giant barrier is the end of the exhibit. In order to progress into the installation, visitors must violate the haptic taboo of the gallery, split the curtain and move forward. Beyond the curtain, the small gallery space is spare. The focus of the installation is an arrangement of kinetic sculptures, sitting on a felt blanket on the ground. Each piece is a rotating wheel of bird feathers, held up by a piece of small gauge PVC pipe. Wires run down the pipe into a single control card. The materials are all apparent but the effect transforms them into minimal bird analogs. With three people in the room, it is easy to see that the feathers rotate faster when approached. With a crowd in the space, the effect is more chaotic and it becomes impossible to discern any relationship between proximity and movement.

Interactivity inevitably removes focus from anything but the interaction, if it is noticed at all. We saw multiple people investigate the piece, focused only on the electronics, trying to figure out how to “make it go.” In Barbier’s use, this is perhaps an intentional distraction, underscoring the disturbing relationship between humans and undomesticated animals in urban environments. The bird analogs spin pointlessly, pathetically, in relation to our nearness and stand in place of a connection to the natural world. With little time for contemplation and a schedule full of assessment, budget cuts, reorganization and perpetual training, the students, staff and faculty of the University of Illinois (where the majority of Barbier’s photos were taken) only encounter birds as they rain down from their impact against the Brutalist architecture.

The “silly project” described in the Danto quote at the beginning of this review describes Paul Klee’s painting Twittering Machine. Mechanical birds perch above a void, feet wrapped permanently around the wire that controls them. They are joyful and terrifying, tongues of exclamation marks and sharp barbs. One wears a spring while another resembles a fly fishing lure. They are unstable, with questionable guy-wires holding them upright. Their perch is a wave on which they will bobble up and down, and perhaps fall, but only if the handle is turned. Barbier’s birds, like Klee’s machine, are a mere mechanical replacements for living beings, precariously perched and only moving within a severely confined environment.

“In my writing I got so interested in fakes that I finally came up with the concept of fake fakes. For example, in Disneyland there are fake birds worked by electric motors which emit caws and shrieks as you pass by them. Suppose some night all of us sneaked into the park with real birds and substituted them for the artificial ones. Imagine the horror the Disneyland officials would feel when they discovered the cruel hoax. Real birds!”2

Where Danto saw an abundance of nature, Philip K. Dick, quoted above, sees the replacement of wildlife with structured wildlife encounters. The artificial birds flutter and respond to our presence but only represent birds as humans imagine them. Barbier’s fake, electric pinwheel birds reduce the illusion to a mockery. The foyer of the installation shows the results of human architecture, inside we are confronted with the futility of seeking a technological solution.

“We are the first generations born into a new and unprecedented age — the age of ecocide. To name it thus is not to presume the outcome, but simply to describe a process which is underway. The ground, the sea, the air, the elemental backdrops to our existence — all these our economics has taken for granted, to be used as a bottomless tip, endlessly able to dilute and disperse the tailings of our extraction, production, consumption.”3

Casualties is not a call to action but a dirge, room silent but for the mechanical sound of small motors. Unfortunately, the human-centered reduction that Barbier’s sculptures outline, a false dichotomy in which we can only “save” or “destroy” nature, is undermined by an associated event. In a catalog insert, we are invited to a workshop on Preventing Bird Strikes. In this two hour workshop, we can learn to “create [our] own DIY devices to help birds avoid collisions with reflective glass surfaces.” The disjunction of human and natural is a much deeper issue and Barbier’s installation poetically makes visible a small intersection in civilization that is incredibly complex, and broken.

_

Images and video courtesy of Annette Barbier

Featured image: still from Fatima Al Qadiri / Sophia Al Maria HOW CAN I RESIST U

E-Vapor-8 is a very cool group show which looks and feels about as much like a club as you would want it to. It features a series of haunted works opening onto the “death of rave” — and what that death means, when it happened, and if it is still happening, are the most interesting questions provoked by a visit.

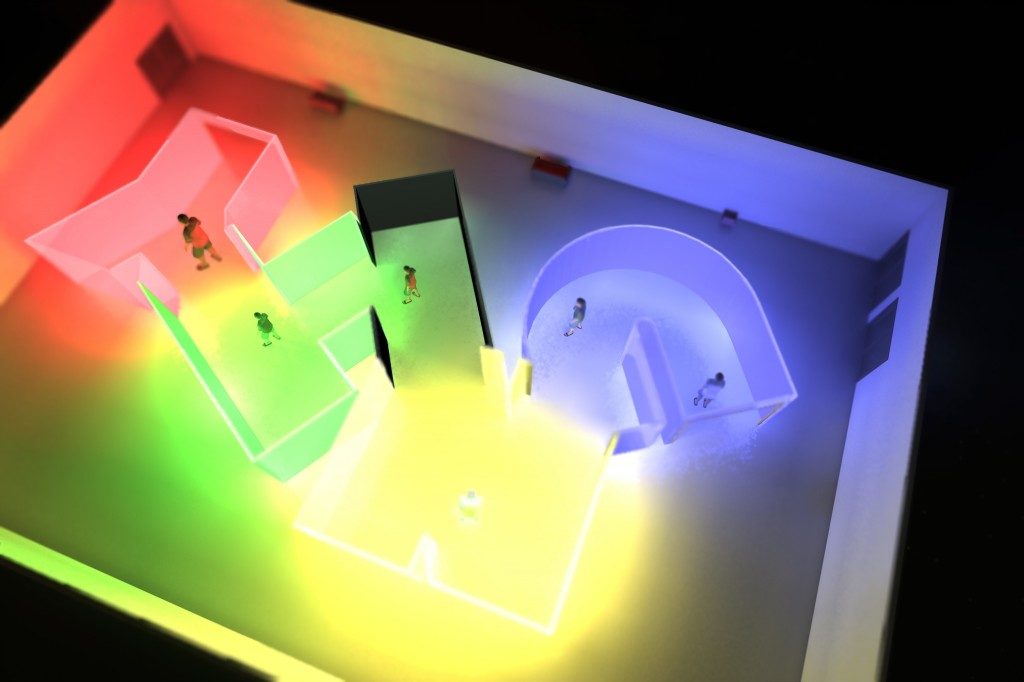

Works by Fatima Al Qadiri, Daniel Swan, Petra Cortright, Rhys Coren become the characters and rooms of a labrinthine underground culture which takes emotion, history, sexuality and race as its headliners and resident evil. It is a small exhibition, considering this scope, and perhaps not the show which the curators would lead us to believe.

The notion of cultural ‘Afterlife’ enters the fray as surely and convincingly as a sweaty-metallic-render 3D blade drifting though green wireframe. Afterlife is a ziegist topic – Transmediale’s Afterglow theme explored an afterward of an already exploded digital scene; Mark Fisher’s term ‘Hauntology’ connected Derridian theory to underround music/artists like Al Qadiri and Maria Minerva; and the recent New Death exhibition at FACT featured works such as Jon Rafman’s installation, depicting an indecent internet-accelerated-libido as a kind of end-of-the-world-is-now scenario. In these works and perspectives the realm of the afterlife is shown to be a nuanced one from which to view the epochal changes culture has undergone, and this is why a show like E-Vapour-8 feels so timely.

The name of the exhibition is taken from a 1992 rave track, but it also makes me think of the recent rash of e-cigarette shops…

and, more portentiously musical genre coinage I know from reading Adam Harper’s contemporary music commentary: vapourwave –

“At the end of the world there will only be liquid advertisement and gaseous desire. Sublimated from our bodies, our untethered senses will endlessly ride escalators through pristine artificial environments, more and less than human, drugged-up and drugged down, catalysed, consuming and consumed by a relentlessly rich economy of sensory information, valued by the pixel.” Adam Harper in DUMMY

Several of the best works here are available to view online, and benefit greatly from the throb and thurst of this gallery setting. Watching Daniel Swan’s Plane Drift V on a hi-def monitor, I appreciated the use of lo-fi pixilation as part of the affective ether of the work, as the utopian 3D crumbles into a flat and luscious digital irony. The video ends its loop on a frieze of a 3D plaque stating ‘Return’, evoking the role of the loop in dance culture, and the mode of reinvention in evidence throughout the show.

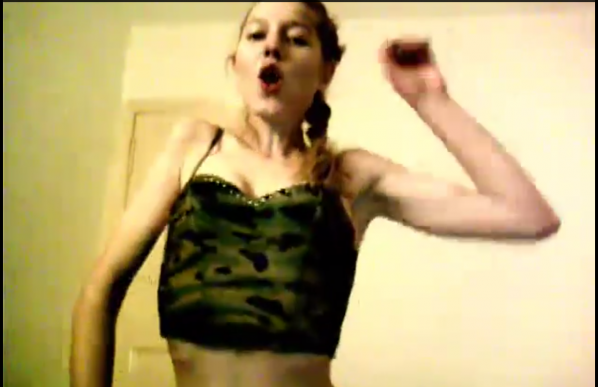

Fatima Al Qadiri’s tune How Can I Resist U with a new video by Sophia Al-Maria dominates the main gallery space with its unsettling deep bass underflows, and audaciously cool bringing together of urban architecture with international dance cultures. In the other room, Petra Cortright’s voyeuristic film Lara Practice shows a young girl trying out her ecstatic dance moves presumably to rewatch later – a tragic pantomiming of ‘happy hardcore’.

Other works play on the aesthetics of given rave cultures. Travis Smalley’s Wave Trancendence splays the multi-coloured trippy aesthetic of early hardcore flyers as a sickly overlush chill-out visual.

Adham Faramawy’s Lifeproof iPhone Cover revisits the metallic Photoshop filter and puts it in motion, his work simultaneously harking back to late-90s era Drum n’ Bass, while having the look and feel of a vapourwave.jpg – except instead of vapour-wave’s marble, the plinths and stands for Faramawy’s work ooze black foam, like an ashtray left in the alley behind your mum and dad’s for thirty years.

This incongruous collection of perspectives, along with the jostling beats across the whole show provoke a kind of nervy excitement. Installations in the show also play and elide bliss and paranoia. Harry Burden inverse-casts a crumpled car wing and paints it in a pearlised blue and green like a strange beetle.

Alexandra Gorczynski’s liquid dream-like video peers up queasily from under a glittery canvas bedcover, and Maria Olsen’s gold tapes in a heap on the floor; each item together and the same, but the artifacts themselves – the music, the person – alone in their capsule.

Only Rhys Coren’s playful video-loop doodles set across three screens to a chirpy four-four house beat seem unequivocally ‘happy’ – but we notice that even here, the screens face away from each other, and the animations jiggle on their own buzz.

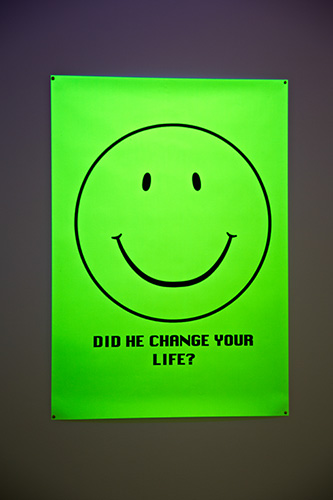

Sitting off in the corridor like a rushed-out raver afterwards, the trouble with this show sinks in. In her short introductory essay, curator Francesca Gavin acknowledges that many of the young artists she features are not old enough to have experienced the first ‘white glove’ rave referenced in the title of the show, but neglects to acknowledge the life of rave and dance culture which these ‘subsequent’ generations find ourselves mourning. To an extent, the use of Acid House here has more to do with marketability than criticality – but to jump right from early 90s rave to the work of an artist like Harry Burden, Adham Faramawy or Fatima Al Qadiri, and to locate the older Jeremy Deller’s smiley-face poster artwork at the ‘fulcrum’ of this show, is to willfully ignore the racial and social complex of the Drum’n’Bass, Techno and Trance which followed (as documented most memorably by Simon Reynolds in his Hardcore Continuum series for The Wire).

Gavin’s insistance that the exhibition ‘examines the utopian ideas surrounding rave before its failure’, seems to ignore what the artists in the show might consider the actual moment of rave’s failure. This central oversight leads to others. The choice of JG Ballard’s Crash as key-text, while obliquely relevant as an aesthetic touchstone of dystopia, doesn’t really reflect on the ‘realness’ of the scene artworks such as Gorczynski’s reference – it would be nice to have a chance to review the impact of a novel like Irvine Welsh’s Maribou Stalk Nightmares on this generation, or reflect on how current novelists such as Tao Lin use prose style to echo the afterlife of re-illusioned rave and drug culture.

The best works in E-Vapour-8 exist as echoes a UK club culture with more ambiguous relations to capitalism and politics than the radical and resistant Acid House rave. The void left by the hedonistic lifestyle is a simulacrum in a work like Faramawy’s, for the void left in our lives by the death of the hope of capitalism, and our continued afterlife within it – like a club we’re forced to keep revisiting even though it’s too expensive the DJs are shit and people keep getting shot.

The deep cuts in Sophia Al Maria’s and Fatima Al Qadiri’s How Can I Resist U are reconstituted and assimilated into an elegy – to the ‘bootyshake’ and bass, but also to social distribution and emptying out of utopian modernist architectures, using the lo-fi and hi-rise as distinctly modern hallucinations, and touching clearly on Sheffield’s own rave heritage in buildings such as the Park Hill flats.

Seen in the light of her generational ‘shortfall’ (being too young to have been seen Altern8 in the Hacienda, but old enough to have got down to Ed Rush at The End) Petra Cortright’s subtle and lyrical cutting and smeering of an original video and its soundtrack in Lara Practice, reminds me of the millenial dancefloor vibe – how out of place those moves were, how re-territorialised they immediately became.

“I start to wonder if she, like me, got sucked in by Ardkore’s explosive euphoria, its manic, fiery-eyed glee, and then got carried along by the music’s logical evolution to wind up at another place altogether, dystopian rather than utopian.” Simon Reynolds ‘”Slipping Into Darkness” The Wire #148

As examples of the thematic depth offered in this show, the Al-Qadiri/Al-Maria and Cortright videos capture the implosion of a naïve energy. By focusing on the female body in the throes of bass, they present distinct and equally valid breakages taking place between anticipation and experience – and the emergence into a darker real and global hyper-real. The artists’ contemporaries in the music scene (including vapourwave artists such as Vektroid and Oneohtrix Point Never) deserve some credit for informing a culture which can act in this way.

It would seem that a gallery of this stature, and a curator with the contemporary culture credentials of Francesca Gavin – visual arts editor at Dazed – would be more keen to link visual art with actual dance culture, rather than a fully assimilated cultural caricature like happy hardcore… but then, the exhibition itself is an opportunity for us to do just that.

I recommend a visit – the show is on until August 17th. Those who were in a circa-1998 nightclub will recognize the nervy and unsettling sensation of the corridor or cloakroom queue, the combination of E-high with screw-face attitude. A steady, percolating dark bass among the hallucinatory imagery and tongue-in-cheek synth refrains. Those who weren’t will undoubtedly find their own touchstones in these independently deeply poignant and distinctly contemporary works.

Play with the Rubik Cube simulator online! Drag the pieces with your mouse to unjumble the puzzle.

Featured image: A live portrait of Tim Berners-Lee (an early warning system). Thomson and Craighead. March 2012.

Flat Earth was published to accompany two solo exhibitions. The first, Not even the sky at MEWO Kunsthalle, Memmingen, Germany from 26 October 2013 – 6 January 2014 and the second Maps DNA and Spam at Dundee Contemporary Arts, Scotland from 18 January – 16 March 2014. The book contains a foreword by Axel Lapp, essays by Dundee Fellow Sarah Cook and DCA Director Clive Gillman as well as an interview with the artists by Steve Rushton.

On the whole, the mainstream art world has failed to ‘convincingly’ adapt to (new) media art and similar contemporary art practices using networks and technology. Thomson & Craighead have overcome this impasse and this is one of a few reasons why they’re so interesting to look at as contemporary artists. The book, Flat Earth does not propose to cover all of their art and this review does not propose to cover all that it is featured in it. The review features Flat Earth Trilogy, The End, October and TRIGGER HAPPY (not in the book).

“Their work provides us with a new perception, through

a completely unexpected multi-focal perspective. They reveal

the wide ramifications of systems of information exchange and

provide us with an insight into the resulting infrastructure of

our own thinking.” [1] (Alex Lapp 2013)

TRIGGER HAPPY: Shooting The Messenger.

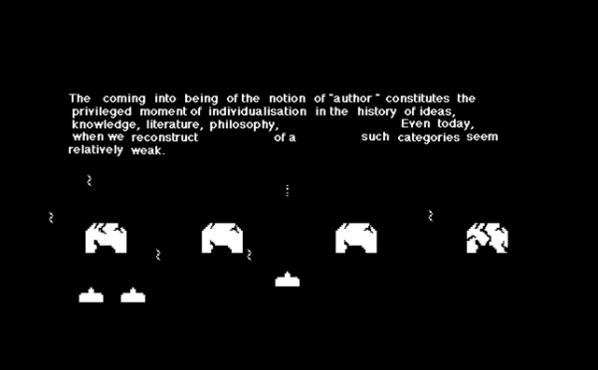

Although TRIGGER HAPPY (1998), is not featured in the publication it provides a useful introduction to some of the ideas and conceptual approaches present in Thomson & Craighead’s later artworks. I first experienced the work online, but it’s also a gallery installation that takes the form of an early shoot-em-up arcade game, Space Invaders. This work reflects the sly and cheeky side of Thomson & Craighead and tells us how humorous they can be in their art. TRIGGER HAPPY is philosophical and playful. It asks the player to shoot down the text of Michel Foucault’s essay What Is an Author? published in 1969. [2]

Foucault said the depiction of knowledge is a production and truth is produced, and it is always a reconstructed falsification. In a way TRIGGER HAPPY gives us a chance to shoot at Foucault, who in this respect is the annoying messenger. At gut-level, this art object recognises that on the whole we prefer to shoot at things or play games, than to deal with the complex and pressing questions of our time. Even if the gamer does manage to destroy Foucault’s text, this action prompts an existential enactment of doubt and induces a more vulnerable state of interpassivity. This relates to the illusion of agency when playing games, using corporate online platforms like Facebook and other experiences involving interaction with media, and it can also be extended to life situations. Slavoj Žižek proposes that interpassivity is the opposite of interaction and says “that with interactivity a false activity occurs: ‘you think you are active, while your true position, as it is embodied in the fetish, is passive’. Žižek refers to the Marxist notion of commodity-fetishism to imply that social relations are increasingly reduced to objects (Žižek, 1998).” [3]

We can almost hear the catchphrases “it’s only a movie” or “it’s only a game” as we are compelled to shoot at rather than attend to the messages that may serve to enlighten us and free us from our societal conditioning.

Flat Earth Trilogy: A networked society’s gaze at its mediated self.

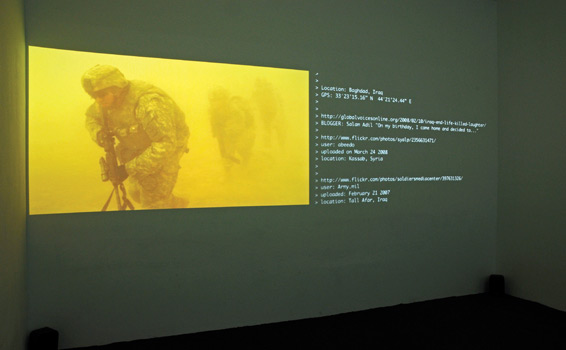

The Flat Earth Trilogy is a series of documentary artworks each made entirely from information found on the World Wide Web; with fragments collected from people’s blogs, This covers a six-year period beginning with Flat Earth (2007) A short film about War (2009/2010) and then ends with Belief (2012).

Commenting on A Short Film About War, on their website, Thomson & Craighead write “In ten minutes this two screen gallery installation takes viewers around the world to a variety of war zones as seen through the collective eyes of the online photo sharing community Flickr, and as witnessed by a variety of existing military and civilian bloggers.” [4]

In the book Flat Earth Steve Rushton discusses with Thomson & Craighead why he feels A short film about War works for him best. He says, “It seems to make a claim on truth – which is the traditional claim of the documentary in particular and photography in general – whilst at the same time it shows us that truth is constructed.” [5] (Rushton 2013)

These works challenge our notion of what a documentary is, what and who the author is, and leaves us with the question, what does this mean for the wider society? This brings us back to Foucault’s ideas on the production of truth and its falsification. Tom Snow writes “In the essayistic act of image compilation then, the piecing together of filmic clips and stills distorts the dividing line between fiction and fact, and reimagines the enigmatic relations between photographic mediums and the condition of representation.” [6] (Snow 2009)

Flat Earth, A short film about War, and Belief all relate to topics concerning human values, conflicts, militarism and everyday societal struggles. “Machines,” wrote Gilles Deleuze in his examination of Foucault’s thought, “are always social before being technical. Or, rather, there is a human technology before which exists before a material technology.” [7] (Berger 2014) And so the technologies we produce are another materialization of the continuing human story.

Millions of people, en-masse, are uploading their personal data (different indications of their states of being) to a collective assemblage. Alex Galloway says that in order to get a better understanding of what networks are we must put aside the idea that networks are a metaphor. He proposes networks as part of a materialized and materializing media. He views this as an important step toward understanding the “power relationships in control societies.” [8] (Galloway 2004)

“It is a set of technical procedures for defining, managing, modulating, and distributing information throughout a flexible yet robust delivery infrastructure.” And “More than that, this infrastructure and set of procedures grows out of U.S. government and military interests in developing high-technology communications capabilities (from ARPA to DARPA to dot-coms).” [9] (Ibid 2004) Galloway’s distinction helps us to re-evaluate what he sees as distracting tropes and uncritical interpretations of the Internet, the World Wide Web and Web 2.0.

Thomson & Craighead provide parallel insights through their artwork into the protocols and technical procedures governing the functions of networks. However, human existence and human experience has a relationship with these networks and, out of millions of interactions, evolves not metaphors but fragmented symbolisms and stories. These are telling us about a networked society’s gaze at its mediated self. And this is where art can play a special role in critiquing, communicating and sharing the nuances of this emerging multitude.

The Flat Earth Trilogy presents us with a complexity where everything is flattened out. It maps out a human psyche from an anthropological perspective. And this leaves society to deal with issues concerning the human condition entwined within a machinic evolution.

This evolution has no physical body even if real lives and bodies are its source material “each mode is displaced by machinic evolution, mixing flows and the shifting codes and overcodes of power, the base forms continue onward, written directly into the heart of the system.” [10] (Berger 2014)

To further understand this work in relation to the machinic evolution, the networked gaze, and human interaction, I feel there is some value in considering hyperreality “…a condition in which what is real and what is fiction are seamlessly blended together so that there is no clear distinction between where one ends and the other begins.” [11] Hyperreality is a post-modern term used by Jean Baudrillard, Albert Borgmann, Daniel J. Boorstin, Neil Postman, and Umberto Eco. However, if we add a contemporary flavour to what hyperreality looks like now in a networked society we come up with hyper-mediality. “What we refer to as reality very often is just mediality, and also because that’s how human nature often prefers to observe reality, you know, via some media.” [12] (Ubermogen 2013)

We can see an example of this condition in an artwork by artists’ Franco and Eva Mattes, with their performance video No Fun (2010) [13] where they staged a suicide in the popular webcam-based chat room Chatroulette.

“Notably, only one out of several thousand people called the police. Moving beyond the aspects of shock and provocation, this touches on a basic question: What does “reality” mean in the digital age?” [14] (Eva & Franco Mattes)

The Flat Earth Trilogy throws up many questions and you’d be forgiven for thinking we need another book to fully examine the ramifications of these artworks. Instead let me to refer you to other related texts by Tom Snow, Edwin Coomasaru, Jo Chard, and Alan Ingram by clicking here http://www.inmg.org.uk/archive/thomson-craighead/catalogue/

Shifting Sands.

Clive Gillman in his essay in Flat Earth says “if artists are to find a way to assert a commentary or expression through these emerging forms of contemporary media, they will have to do this by reconciling the resistance of these new media objects to be ordered into a form that may represent a recognisable notion of artistic intent. And it is into this challenge that Thomson & Craighead pitch themselves.” [15] (Gillman 2013)

It is not the audiences who have difficulties with emerging forms of contemporary media it is the mainstream art world, and this is most of its magazines, galleries and museums. From our own experience of showing art and technology at Furtherfield Gallery, audiences tend to be adventurous and open-minded regarding their experiences with technology and societal issues. And yet the art world has had difficulties making a place for this work.

Sarah Cook and Christiane Paul, both curators well versed in the field of media art, have tirelessly offered us convincing arguments why this is. Christiane Paul says, “Many curators and other practitioners in new media seek to “teleport” the art out of its ghetto and introduce it to a larger public.” [16]

Sarah Cook says “artists who are really working with technology are still redefining art. So they’ll always be “in emergence” [..] They always will try to change the boundaries of what we think Art is and challenge the institutions that show it.” [17] This is true with Thomson & Craighead’s installation and networked artwork. It is plugged directly into a larger, expansive, worldly discourse, in contrast to traditional modes of artistic and news presentation which are highly restrictive and contained within their mediated monocultures.

Gillman proposes that Thomson & Craighead are pitching themselves to create art which is a recognisable notion of artistic intent, and other artists should do this also. I am assuming this is so the work is recognisable as ‘art’ to the mainstream artworld and its traditional remits. This is a strange ask if you are an artist who is truly exploring further than what is typically expected by mainstream art culture. I would argue that artistic context and its values are not fixed and that’s the point. If artists become too self conscious in trying to make their art look like an art that “fits”, it then looses its imaginative edge and critical reasoning.

It’s a difficult balancing act if the artist is examining deep or necessary questions whilst the current art world is lagging behind in so many ways. Julian Stallabrass sees this lagging behind as a political issue. In his book Contemporary Art: A very Short Introduction, he critiques the blocking of emergent, and critically engaged artistic expression as part of a ‘New World Order’ where we are constrained by a compliant culture controlled by the rampant demands of a corporate elite, who only consider art in terms of economics, markets and brands. And these restrictive and dominating frameworks are dedicated to the neoliberal promotion of privatisation and growing inequalities.

In his article ‘Reasons to Hate Thomson & Craighead’ he says “At this point, the art professional sees a world crumbling, visions of empty galleries, unique works owned by everyone, a stuttering and then failing of artspeak amid a mass proliferation of ‘work’ and comment, the autonomy of art ruptured, artists and dealers redundant, in short an economy broken and the sacred polluted with the profane. Naturally, representatives of the old order, more or less sharply aware of dark clouds gathering at their horizons, have good reason to hate Thomson & Craighead.” [18] (Stallabrass 2005)

Thomson & Craighead’s work connects with people and they know this because they use content and themes people are thinking about in their everyday lives. This is what makes the series of documentary artworks so powerful. It assembles what is going on in the world in ways that traditional documentary and news channels are not. And this is their real challenge, because if they continue to reflect human culture as it happens with works like October – a documentary artwork about the early rise and fall of the Occupy movement – they will be highlighting messages from a world of people in need of something different than what is currently in place, whether this is deliberate or not. This art has a strange irony, it not only asks us what a documentary is, but it also asks what is news?

The End.

The End is a site-specific artwork first shown at the Highland Institute of Contemporary Art in 2010, Scotland. It is situated in one of the gallery rooms at H.I.C.A that has a large, wall-sized window looking out onto the countryside in the Highlands. It is an intervention into the space where the words ‘The End’ are fixed onto the glass in a style and scale one might associate with the end credits of a movie.

The combination of the outside natural environment, the galley building with its large glass window, and the added text, are assembled together to build a whole artwork. If any these components were taken out of the assemblage it wouldn’t work. This tells us how well crafted Thomson and Craighead’s work is and how much attention is paid to detail.

When looking at The End, one cannot help feeling a little out of sync. It is like a monument or an obituary for a lost world or lost time when we were all standing on solid ground and felt we knew what was real and not real. The End brings into play the rhythms of a larger natural environment and works as a bridge between two worlds or the illusion of it. It reminds us we are no longer experiencing the world face on or directly, but the world is re-introduced to us mainly through screens, televisions, mobile phones and our computers. It also invites us to imagine as we look out on the beauty of the natural world that we are viewing the end of our own role in the story of humanity.

The Situationist, Guy Debord said that people’s alienation was once about having things and claiming better working conditions, but then it moved onto being about a state of appearing. Meaning, it is not producing things, or even owning things that drives society but rather how things appear and how they make us appear. The glass acts as a filter and an interface, a place of safety distant from the touch of the wild. Its physicality, metaphors and symbolism offers a poetic moment for us to consider how perceptions about ourselves and ideas concerning real-life have changed, and what this means.

On the DCA website as part of its commentary about the book, it says Flat Earth presents Thomson & Craighead as pioneers in the field of new media for nearly twenty years. Sarah Cook and Christiane Paul also deserve credit as pioneers for recognising, supporting and dedicating their lives to creating the contexts in contemporary art culture for Thomson & Craighead’s work and other artists’ works. Also, Cook has edited a fine publication. Flat Earth is well designed and the whole book is meticulously well put together with quality images throughout. The mix of inteviews and essays with Thomson & Craighead give the reader a well balanced overview of their the art and their ideas, it is unpretentious and explores their focus as creative and thinking individuals artistically, conceptually and critically. We need many more of these types of books to support this dynamic and ever-changing field.

Thomson & Craighead dig deep into the algorithmic phenomena of our networked society; its conditions and protocols (architecture of the Internet) and the non-ending terror of the spectacle as a mediated life. When reading the Flat Earth publication, you get a clear impression of their conceptual rigour. They know their place and role as artists in society and this is well presented in the book. Their collaborative journey has remained faithful to the World Wide Web, and the Internet as a focal point and a content provider for their art practice.

It would be simplistic to assume they are embracing technology as a celebration of its progress. Their critical scope examines big issues and this is evident in Flat Earth. They belong to a generation of artists who are experimenting with real time data, networks, web cams, movies, images, sound and text; as part of an anthropological venture that studies humanity’s relationship with technology, alongside the inane and profound nature(s) of the human and non-human condition. We exist at a point where ubiquitous computing now redefines our point of presence, shifting our perceptions in reference to cultural tags and repeated experiences of mediation. They successfully critique these changes. Not only to other artists, curators and galleries, but to all who are being transformed by technology and this is what makes them essential and contemporary.

Thomson & Craighead are not just making and showing art they are also presenting questions. These are not invented questions they are already out there. But, just like some need an interpreter to translate different dialogues they are assembling for us the dialogues of an emergent multitude.

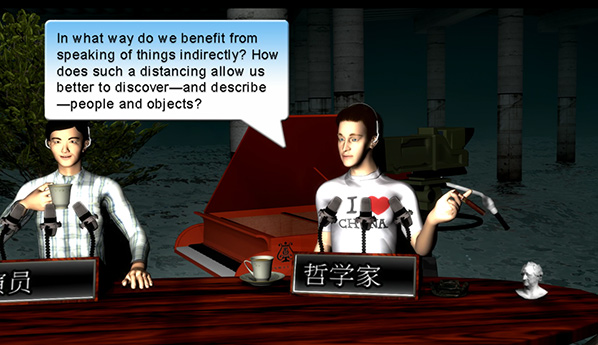

Eva Kekou met Tobias Rosenberger at the international e-MobiLArt workshop which took place in Athens, Vienna and Rovaniemi, in turn these led to a number of exhibitions and successful collaborations between artists and theorists. She now invites him to discuss his work, issues of surveillance and how a young European artist views the situation in China and what he expects from his interaction with the Chinese art scene.

Tobias Rosenberger (b. 1980) is a German media artist who works at the crossroads of media art, visual arts, and performance. He has produced art works in Yemen, Spain, Mexico, India, and Ukraine etc. Since 2011 he has been based in China, where he teaches at the College of New Media Art, Shanghai Institute of Visual Art.

“Nowadays, anyone who wants to combat lies and ignorance and to write the truth must overcome at least five difficulties. He must have the courage to write the truth when it is suppressed everywhere; the wisdom to recognize it, although it is concealed everywhere; the skill to use it as a weapon; the judgment to choose those in whose hands it will be effective; and the cunning to spread the truth among such people.” (Bertolt Brecht)

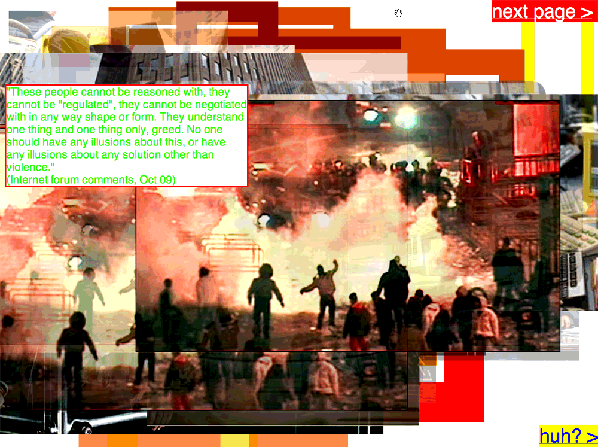

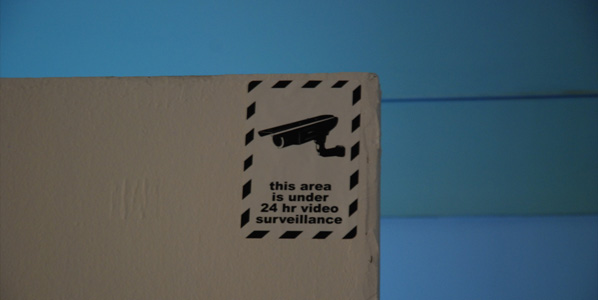

Eva Kekou: I would like to start this interview with this quote which seems to be significant for your work and in particular the recent one – the secret race film and discussion at Goethe Institut Washington. As you well state in your event invite: “It was pure coincidence that for a few days in the summer of 2013, two unrelated events simultaneously dominated the major headlines in the German press: the monitoring and spying scandal of 2013, triggered by Edward Snowden’s leaks of National Security Agency top-secret classified documents, and the official acknowledgement of the prevalence of doping in competitive sports, best symbolized by Lance Armstrong’s televised confession.” What is the significance of surveillance in a globalized social and political context and where is the place of art within it? There are obvious reasons you decided to launch this in Washington through Goethe but I would like you to comment on this.

Tobias Rosenberger: Surveillance and espionage are as old as civilization. Power was always constructed, maintained, and expanded through monitoring, categorising, repressing, and excluding people. We all know that the digital apparatus opens a new world of possibilities to organize, quantify and control life and society in a before unknown scale, speed and efficiency. While I agree that we need early warning models to anticipate and fight cruelty and injustice whenever possible, I don’t believe that we can draw a sharp border between an evil surveillance that fuels unfair and inhuman systems and a necessary one that pretends to save dignity and a lawful order. The challenges of our time can no longer be met by elitism and secretiveness, but require the joint efforts from the middle of society. An independent art that rejects the simple desire for (self-)confirmation does not only open a non-biased discursive space for critical reflection, but it also has the potential to demask and break the mechanisms of power, as long as it takes its audience seriously. But to be able to do so, art also has to find its audience.

EK: It occurs to me that place and space play a very important role in your work and inspiration. How do these relate with each other with pieces of your work in a globalized and mobile network underlined by politics?

TR: I have a very pragmatic approach to what I am trying to do: Not following a specific agenda and always staying as curious and open as possible. This requires both a certain naivety and an observing attitude. I never start an artistic process with a specific idea or question, but i get attracted by places and spaces that i try to discover without too much of my personal baggage. But since space and place are never abstract but segmented by politics both on macro and micro layers, the resulting works often deal with political questions.

EK: How did you become interested in China and what do you find fascinating or difficult working there? Is it interesting for you as a European?

TR: I have a very special relationship to China. With my Chinese wife I decided three years ago to move there and to found a family. I was always fascinated by China as a cultural space, with a tradition of art and philosophy at least as long as in Europe. I also really like the food and the people there. As a foreigner I experience it as very fruitful to see things from a specific distance, both if I try to understand the culture, but also especially if I look back from there to where I come from. It is very interesting to observe the relation between art and politics, how the government here really appreciates art and how it is also afraid of it.

How artists, critics and curators fight for free space, a career, or both. In Shanghai you have both the global economy and the local life at your house-door. The country faces a lot of problems, and very often one can get the impression that things are not happening at all just because there is a small possibility that something unexpected could happen. So many people behave very pro-actively in a way that they won’t run into any problems themselves. But this maxim “to have everything running smooth” you certainly don’t only encounter in China.

EK: Referring to some of your recent works (installation and performance): Choose any you like… How do you reach out to audiences and what is the main aim in your own work?

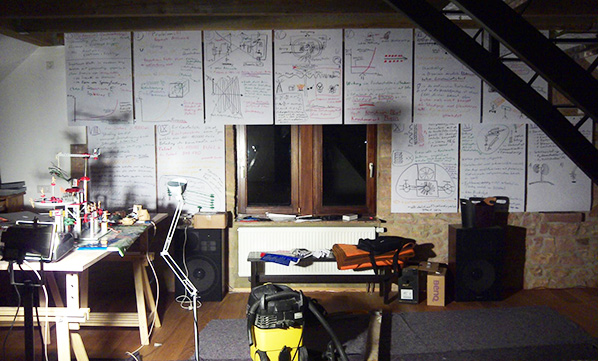

TR: “The First Twenty Years” is an installation that was shown in two different versions at the end of 2012 in Kiev and Dnipropetrovsk. I developed the basic idea for that work in 2011, when I was invited to spend some time in a small Ukrainian village near Kiev at a private artist residency programme. During that time the nation celebrated the 20th anniversary of its independence. There was a strange, partly paralyzed mood. But I also witnessed very controversial discussions with artists, curators and critics, and a new generation that seemed not anymore willing to accept living in a nation that was more and more perceived as a prison. So when I was approached during that time to do a work based on my experiences in the Ukraine, I decided to base it on Xavier de Maistres “Journey around my room” and Schuberts Music, which was inspired by a poem by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart.

I didn’t intent to comment directly on the situation there, but rather was trying to understand for myself what was happening. For me, art is not about expression but about the creation of a space where everybody is invited to take a bit of distance so to be able discover something from different perspectives and to think in his/her own way.

Surveillance Cameras dancing to Schubert, on Vimeo

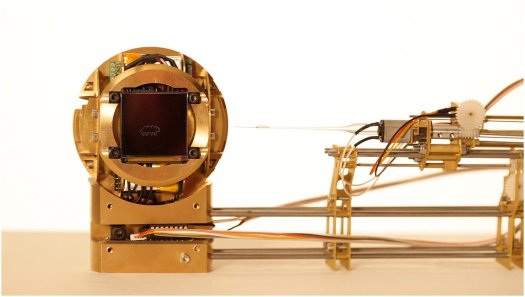

EK: Can you give us a bit more information about a project that you have described alsewhere in the following way: “Right now working on a light sculpture for permanent setup in a former WWII Top secret military site, where some crazy NS-Germany scientist wanted to invent an x-ray wonder-weapon to shoot planes and soldiers, this involves an always transforming multichannel-sound installation, motorized miniatures (arduino-controlled), 2 projectors and led-objects. I will make an extra independent video of this work, filmed with multiple moving surveillance cams.”?

TR: I was approached by a cultural initiative that runs today a small history museum in a former research bunker, which was secretly constructed in 1942 / 1943 underneath a camouflage building. I came across a letter in which a certain Professor, Dr. Ernst Schiebold, proposed “An additional weapon to fight and eliminate the crews of hostile airplanes and ground troops in the defensive via x-ray and electron radiation”.

A weird ten pages male war fantasy about a new kind of tubular x-ray canon, written in a crude mixture of physical pseudo-science, soft patriotic enthusiasm and German pedantism. Schiebold really got his bunker built to start with his research. Everything was kept top secret, but stopped 18 months later without results. I decided to bring Schiebold’s proposal back into the space which only existed because of it: As a pure proposal, enhanced and communicated with new media technology.

A lot of the tools that we are using as new media artists exist mainly through military development. So my intention was also to give something back. The audience will listen to single sentences that are randomly taken out of Schiebold’s letter and re-arranged into a constantly transforming synthetic sound atmosphere, which is synchronized with light beams crossing a motorized miniature military model. The toy miniatures cast shadows of moving soldiers and airplanes onto the walls. LED lights are flashing out of a tubular manhole, which was originally constructed to be used with a Betatron. All the technology that I use is quite low-budget and geeky. Last week I started to install the parts on site, and I have to admit that it is also a very weird experience for me to spend nights working alone in a former military research bunker, climbing down in a manhole and setting up the mockup of a “super-weapon” people researched in the darkest years of German history. Sure I will also try to document it properly.

EK: Do you think art can be global and political, if not, what are the main restrictions we are all subjected to? How can art and artists make a difference in this respect?

TR: I think that art is per se political, since it deals with and also influences our perception of reality. And while all our lives are clearly connected in a global economy of good and information-exchange, art does also always operate on a global scale. As an artist I believe that it is worth to be curious and to investigate the (media) apparatuses and dispositifs that surround us, to take them apart and re-design them. What are they good for, what effects do they cause? While the world is getting closer, the world is never the same – people have different histories, problems, possibilities and hopes. As Europeans we take many things for granted, that other people see differently – or vice versa. I think artists can always make a difference, as long as they stay independent and continue to tackle serious questions, but don’t take themselves too seriously while doing so. We should laugh more together.

EK: What are your future aims and plans?

TR: I am looking forward to the new semester in Shanghai, where I will mentor the graduate works of eight students. I will also collaborate with Chinese artist Mujin (Lixin Bao) – a fellow teacher at the Shanghai Institute of Visual Art – on a series of works exploring the notion of the “Chinese Dream” and its perception both nationally and globally. I guess this dialogue will become quite interesting.

THE CRYSTAL WORLD

The White Building, London

3 August – 30 August 2012

The Space’s White Building cultural centre is within walking distance of the 2012 Olympic stadium in post-industrial, post-regeneration London. As I walked down the steps that lead to it I saw a diesel locomotive pulling a train of cargo containers across an old railway bridge over the canal nearby. Millions of these rational forms will be in transit around the world at any given moment, arranged in two or three dimensions like crystalised capital on trains and docks and ships.

The logistics of their production and distribution are determined by computing machinery using algorithms that operate with inhuman speed and complexity. This same economic logic warps the architecture of the area around The White Building, with old factories and warehouses retro-fitted as office space and as gallery space.

Inside the White Building’s project space the computational enabling technology of the global economy is the subject of a show by Martin Howse, Ryan Jordan and Jonathan Kemp. It takes the title of J. G. Ballard’s novel “The Crystal World” as its starting point. In Ballard’s novel a virus progressively turns all life – vegetable, animal and human – into crystal forms frozen in time. It is a Cold War allegory of the catastrophic imposition of rigid order.

For Howse, Jordan and Kemp these imaginary crystals become the very real minerals refined in the production of the computing machinery used to structure our contemporary world. Inside every digital computer are wires, circuit boards, integrated circuits and other components. They are made from iron, copper, phosphorous, boron, tantalum and other rare earth elements. The central processing unit of a computer keeps time using a quartz crystal. The products of deep geological time are suddenly unearthed and set to pulsating millions of times a second.

Computers are crystal engines. They are mineral fetishes that we use to manipulate powerful unseen forces that we believe we have mastered, like crystal healers working with a patient’s energy grid. But they are so invisibly familiar to us as our smartphones and laptops and their use in logistics and media is so pervasive that it takes an effort for us to perceive their operation or their implications.

It takes almost two tonnes of raw materials to make a desktop PC. Unlike “Tantalum Memorial” (2008), by Harwood, Wright and Yokokoji, “The Crystal World” focuses on these raw materials geologically and temporally rather than geopolitically. But computing waste is toxic and valuable. The former makes disposing of old computers a growing problem, the latter makes recycling old computers a growing business. The minerals that computers contain can be recycled where they are valuable enough, or left to leach into the water supply in e-waste dumps where they are not.

Or in the case of “The Crystal World” an open laboratory and the resultant art installation can re-extract them from their components and printed circuit boards using acid, water, electricity and heat in order to re-crystalise them and return them to geological time. The gleaming silent boxes that organize and mediate our lives are returned if not to the earth from whence they came then at least to their raw materials.

Tables edge the White Building project space, covered with the equipment and results of five days of workshops (and one with books, including Ballard’s, giving any spectators unsure of what is happening a conceptual framework to proceed from). Table after table of crystals, circuit boards, jars, electical equipment, and wires are overwhelming in the details of their appearance and implication. These traces of human activity and inquiry frame the flow of water and electricity in the center of the space, convincing the viewer of the creative intent of its production and drawing them in to its logical universe.

The centre piece of the show is a favela chic water feature that drips acid-loaded water through calcinous rock fragments, over e-waste, into two cut plastic-drum tanks. Next to it an array of smaller plastic containers contain circtuit boards having their copper leeched from them by acid, fungus growing on the by-prodcucts of the project, and other watery deconstructions of computing machinery. It looks dangerous and uncertain, deconstructing both the physicality and the meaning of computers. Seeing the innards of an IBM ThinkPad computer becoming encrusted with calcium like a digital stalagtite, or CPUs branching feathery crystals, returns computing machinery to its raw mineral state. FLOPS give way to eons once more. Neither is a human timescale, yet we must live between them at the moment.

The most fantastical artifact along the walls of the project space is the “Earth Computer”. It’s a battery-like construct of recycled copper and zinc in a tray of silver nitrate attached to lightning conductor-style copper strips. Sitting in earth on a plastic sheet and surrounded by the left-over materials of its creation for the duration of the show, it will be buried nearby afterward. Such a device can function effectively, but not literally. It is more likely to spring to life in the mind of the viewer than if it is struck by lightning. It is effective art, psychic engineering rather than technological cargo culting.

Acid, water and electricity mixed together with e-waste look and feel dangerous. The recycled ad-hoc materials and equipment containing and channeling them reinforce this feel and leaven it with an aura of creative investigation. The form of the show is timeless, the workshop of the alchemist, outsider scientist, or mad inventor. Its content is very contemporary, from Ballard’s rising cultural stock and the social and environmental costs of e-waste to Long Now deep time and posthuman philosophy. Art symbolically resolves the gaps between ideology and reality, and computing is so pervasive and key to society that most people don’t even regard it as ideological never mind conceptualise its failings as such.

The water and abandoned human artefacts of some of the installations is more “Drowned World” than “Crystal World”, and the broken machinery is more “Crash”. Ballard’s catastrophes provide a modern mythology that is a more useful resource for art than its literary roots might suggest. It achieves the defamiliarising and critical impact of hauntological art without requiring its supernaturalism or nostalgia. There is a Ballardian attitude at play here.

I found “The Crystal World” mind-blowing. It relates the tools of our human existence to non-human substances and timescales, providing the kind of corrective to anthropocentric vanity that object-oriented philosophy aspires to. It achieves this profound insight and presents it in an accessible way precisely because of the modesty of its materials and aesthetics, and because of the resonances of the cultural materials chosen as its starting point.

http://spacestudios.org.uk/whats-on/events/the-crystal-world-open-laboratory-exhibition-

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

Part of Furtherfield Open Spots programme.

Seeking to investigate new modes of audience experience, {crowdsourced} Noir / Love Beyond Recognition is a process-based artwork encompassing a sculptural installation and an interactive stream across the World Wide Web. Both parts of the project are based on the notion of “crowdsourcing” and the use of public domain archives for works of art. The physical installation will be exhibited at Konstepidemin Gallery, Gothenburg (SE), with live interactive streams at Furtherfield Gallery, London.

Visitors will be able to search for keywords from a database of short clips selected from the online public domain Film Noir Archive and hear them play through sourced short clips dialogues containing those words, while a live video stream connecting the two venues in London and Gothenburg will show the sculptural installation intercut by those dialogues and related video footage. A compelling cinematic experience is created. Visitors at Konstepidemin Gallery will be also able to see the live stream and hear the dialogues selected by the London-based audiences.

{crowdsourced} Noir / Love Beyond Recognition is a process-based artwork encompassing a sculptural installation and an interactive stream across the World Wide Web. The origin of both parts of the project is based upon the notion of ‘crowdsourcing’. The principle being that more heads are better than one. By canvassing a large crowd of people for ideas, skills, or participation, the quality of content and idea generation will be superior. In this instance, crowdsourcing will be applied through the use of clipsourcing tools which have been developed to aid in project-related tasks that can only be achieved through human interaction/intervention. This way, the crowd will help the artist achieve these tasks whilst adding a democratic element to the final outcome of the project.

During Spring and Summer 2012, an interested public was invited to both participate and contribute to the project’s creative process in two distinct ways: in Sweden as models, whereby a cast was taken of a chosen body part (the body parts were later assembled to full figure sculptures) and in the UK by taking part in a workshop at Furtherfield Gallery to help source short clips from the online public domain Film Noir Archive through our online tool.

The digital part of Posch’s project was developed in collaboration with UK artist and new media developer Mike Blackman.

Josefina Posch

Josefina Posch is a Swedish artist that has worked and exhibited extensively abroad, including at the 52nd Venice Biennale, Fondazione Pistoletto’s Cittadellarte, Sculpturespace NY and a residency at Duolun Museum of Modern Art Shanghai. During her 3 month residency at Art Space, Portsmouth, in Autumn 2010, she began her collaboration with artist and new media developer Mike Blackman in the development of her digital concepts.

The project is supported by Gothenburg City Arts Council, Arts Council England/British Council and IASPIS – The Swedish Arts Grants Committee’s International Programme for Visual Artists.

www.crowdsourcednoir.org

www.josefinaposch.com

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England.

Contact: info@furtherfield.org

DOWNLOAD FULL PRESS RELEASE HERE

See images from the opening of Invisible Forces on Flickr.

Scroll down for the video of the exhibition.

An exhibition about why contemporary life is so difficult for so many

Invisible Forces features the work of artist-visionaries: Kimathi Donkor, Laura Oldfield Ford, IOCOSE, Dave Miller, Edward Picot, and YoHa with additional game events, talks and workshops with Class Wargames, The Hexists, Olga P Massanet and Thomas Cade Aston.

Our social, economic and cultural institutions are being dismantled. Control over the provision of social care, urban and rural development, and education is being ceded to the market facilitated by unseen technological and bureaucratic systems.

Undeterred, the artists in this exhibition meet the challenges that ensue with clear eyes, spontaneity, experimentation and a sense of adventure. This selection of installations, digital video, net art, painting and drawings deal with conspiracy, money, politics and hidden signals.

As part of Invisible Airs, YoHa (Graham Harwood & Matsuko Yokokoji) attempted to read 20,000 comma separated lines of Bristol City Council’s apparently open-data. After which they understood that power reveals itself through multiple layers of boredom. They constructed four pneumatic contraptions which reveal the relations contained within the fields and the people affected. A video made by Alistair Oldham documents their art project Invisible Airs, Database, Expenditure & Power. Invisible Airs was commissioned by The University of the West of England’s Digital Cultures Research Centre (DCRC) in collaboration with the Bristol City Council’s B Open data project.

This is shown alongside Data Entry, a video that investigates how databases operate on us and through us by looking at the work of midwives and women in labour. “Databases move through us, allowing new forms of power to emerge… [they] order, compare, sort and create new views of the information they contain. New perspectives amplify, speed-up and restructure particular forms of power as they supersede others.”

Edward Picot is an artist and writer who also works as an administrator in the UK health service. His seriously funny soap-gone-wrong, Dr Hairy In…, chronicles the trials, tribulations and cogitations of an ordinary (but slightly hirsute) general practitioner – with hilarious results!* Dr Hairy’s struggles with NHS bureaucracy are brought to life in a series of satirical video shorts, featuring puppetry performances given by a child’s doll and screened in a doctor’s waiting room, as an installation. “It was like watching Team America set in the NHS” says Ian Hislop (broadcaster, editor of Private Eye and NHS patient).

Kimathi Donkor‘s Toussaint Louverture at Bedourete is a history painting made with oils on canvas that depicts an icon of anti-slavery struggles who, in his lifetime, was smeared as a reprehensible war lord. Created to mark 200 years since the independence of Haiti, the image shows the leader of the Haitian 1791-1804 revolution in a pose reminiscent of the Jacques Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps, surrounded by inspired revolutionaries in a battle that led to the creation of Haiti as the first slave free nation in history. In a short film by Ilze Black, Dr Richard Barbrook and Fabian Tompsett of Class Wargames interview Donkor about the work.

Laura Oldfield Ford‘s recent drawings are the result of walks (or ‘Drifts) through deserted urban spaces in the part of East London being prepared for the 2012 Games. They depict layers of failed utopias of the past and present and imagined futures. Known for her poetic and politically tuned ink drawings produced in print and online in her zine Savage Messiah, Oldfield Ford documents her psychogeographic explorations, in text and image, of the city as a site of social conflict, melancholy and political resistance.

Net artist Dave Miller presents two agitprop posters and a pamphlet of images reproduced from his interactive, multi-layered, online narrative bankers_bonuses. Miller worked with software he created himself to combine hand drawn illustrations with images gathered from Internet searches, and provocative (sometimes preposterous) statements made by powerful people about the ethical questions arising from the economic crisis.

Italian artist group IOCOSE has created A Crowded Apocalypse, a net art project that exploits crowd sourcing tools in order to simulate a global conspiracy. The “crowd” assembles its own conspiracy and then protests against its protagonists and effects. A Crowded Apocalypse is commissioned by AND Festival and Furtherfield.

As we scan our cultures for maps, role-models, possible ways of living in today’s world, we often encounter images of society that are created by its hidden, controlling forces. By naming, revealing, tracking, playing, making, subverting and transforming tools, circumstances and figures that give rise to current crises we enlarge the debate and extend our freedoms. And the artists in this exhibition offer examples of just some of the ways in which this might be done.

* Important note. Dr Hairy In… is NOT a critique of socialised medicine and so we include a disclaimer: “The creators of this piece would like to point out that they all work in the National Health Service and are completely devoted to it.”

Free public play, games, making and discussion run alongside the exhibition.

Led by Dave Miller, The Hexists, Class Wargames, Olga P Massanet and Thomas Cade Aston. See HERE for details.

Rachel Baker (The Hexists)

Rachel Baker is a network artist who collaborated on the influential irational.org. Her art practice explores techniques used in contemporary marketing to gather and distribute data for the purposes of manipulation and propaganda. Networks of all kinds are “sites” for Baker’s public and private distributed art practice, including radio combined with Internet (Net.radio), mobile phones and SMS messaging, and rail networks.

Kayle Brandon (The Hexists)

Kayle Brandon is a inter-disciplinary Artist/researcher, whose work is sited within the public, social realm. She predominantly works in collaborative and collective fields; a working method which informs much of her ethos around the making of art. Her main areas of interest are in the relationships between the natural and urban worlds and Human/Non-human relations. She investigates this field via physical intelligence, provocative intervention, observation, self-guided exploration and collective experiences.

Class Wargames

Class Wargames is an avant-garde movement of artists, activists, and theoreticians engaged in the production of works of ludic subversion in the bureaucratic society of controlled consumption.

The members of Class Wargames are Dr. Richard Barbrook, author and senior lecturer in the Department of Politics & IR at the University of Westminster; Rod Dickinson, artist and lecturer at University of the West of England; Alex Veness, artist and co-founder of Class Wargames;Ilze Black, media artist and producer; Fabian Tompsett, initiator of London Psychogeographical Association and author; Mark Copplestone, author and figure designer; Lucy Blake, Software developer; Stefan Lutschinger, lecturer, artist and researcher; and Elena Vorontsova, World Radio Network and journalist.

Kimathi Donkor

Kimathi Donkor lives and works in London. He attained his B.A. at Goldsmiths and an M.A. at Camberwell College of Art, both in Fine Art. In 2011 he received the Derek Hill Award painting scholarship for the British School at Rome; and, in 2010, his paintings were exhibited in the 29th São Paulo Biennial, Brazil.

IOCOSE

IOCOSE has been working in Italy and Europe since 2006. It organises actions in order to subvert ideologies, practices and processes of identification and production of meanings. It uses pranks and hoaxes as tactical means, as joyful and sound tools. IOCOSE thinks about the streets, Internet and word of mouth as a battlefield. Tactics such as mimesis and trickery are used to lead and delude the audience into a semantic pitfall.

Dave Miller