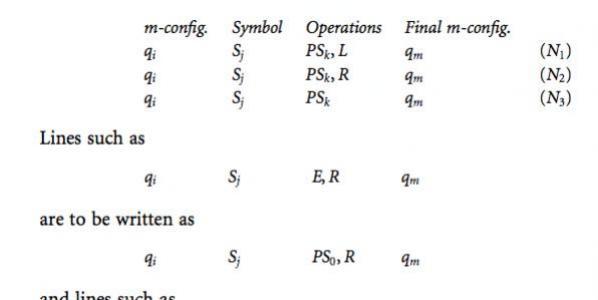

Feature image: Still from Dreams Rewired: original source Das Auge der Welt (Germany 1935); dir: C. Hartmann

Dreams Rewired / Mobilisierung der Träume – Trailer from Amour Fou on Vimeo.

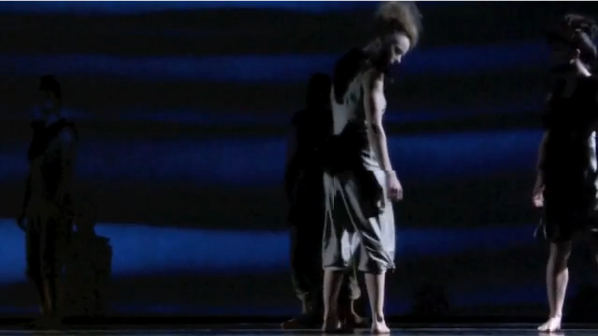

The 2015 film Dreams Rewired, recently shown at the Watermans Digital Weekender in London on 12-13 November, will be screened again at Watermans on 3 December. Directed by Manu Luksch, Martin Reinhardt and Thomas Tode, the film has the tagline ‘Every age thinks it’s the modern age’. It looks back to the early 20th Century, to the development and implementation (first locally, then globally) of the telephone, the radio and television.

The makers of Dreams Rewired unearthed and arranged early film recordings and brought them into the 21st century context. This was done via a playful narrative written by Manu Luksch and Mukul Patel and read by Tilda Swinton. The tagline was well chosen; almost everything Swinton says would have been relevant at almost any point within the last century. Time periods, machineries and political movements are connected in clever and unexpected ways, meaning that Dreams Rewired, a durational video whose narrative follows a recognisable storytelling structure, makes numerous links between times, places and people, which branch off from the safety of its linear structure.

Dreams Rewired is something of a treasure trove, not only for the glimpses its found-footage building-blocks gives into a past era but also because of the inter-generational, inter-national, inter-thematic connections it makes. Frequently while watching the film I felt the urge to burrow into an investigation of one of the clips, stories or introduced contexts. To emulate this ‘tip of the iceberg’ effect, this review will pull words directly from the film, linking quotations to some of the themes which appear and reappear throughout.

“A new electric intimacy”

With new media come new practices of communication. One of the recurring themes described in Dreams Rewired is the coupling of intimacy and invasion of privacy introduced to society along with a new communication method. Just as a new invention is prototyped, its social implementation causes new prototypical behaviours – new ways of caring, new ways of injuring, new comings-together, new separations. Uncertainty is inherent to experimentation.

“The waves travel at the speed of light, defining what simultaneous means. Information can travel no faster.”

When something is newly possible it also newly achievable – new precedents are set and new avenues opened for exploration. There is a flurry of activity, a rapid diversification. For those looking to gain or retain power over others, this is a problem; diversity requires more effort to manage. Initial flurries of activity are curtailed by the introduction of rules, the setting of precedents.

This limitation sets new targets to meet, new challenges to overcome. The cycle starts again as those in power look for ways to consolidate it while those without look to gain what they can. This is a simplistic, but not inaccurate, description of the machinery of the capitalist world.

This cycle of diversification and restriction is always coupled with the establishment and transcendence of thresholds. Experimentation with a new technology reveals some of its limits. (Side note – of course, what is understood as a limit is defined by wider cultural contexts.) “Information can travel no faster” is a provocation to speed up.

“Geography is history”

New advances cause conceptual shifts. Early telephony and television shrunk the gap in time between a thought or plan and its activation. Understandings of time and geography changed, and it became possible to move into new spaces and in new ways at socially impressive speeds. New powers, in short, were available to those who knew how to access them, to those who understood the preceding context well.

“A model of the new human is put into circulation”

A network grows, its complexity and partner processes intensifying. The machinery of daily life is altered, and daily life is a testing ground. Social interactions change as the new set of behaviours required to work the new machinery collide with existing social norms and rituals. New jobs and new workplace structures appear and people previously without responsibility or power find themselves in contact with it (though they may not understand the possibilities at first). People are no longer the same beings as before. Cycles of experimentation and consolidation reach into the body.

“Someone will have to lift us up. But who will lift them up?”

The flurry of excitement surrounding a new invention is based on the idea that ‘our’ lives will be improved, that ‘we’ will be able to do, see, have more. There is a problem here. The words ‘we’ and ‘us’ are too abstract – they bracket whoever the speaker wants them to bracket and recapitulate the prejudices they have. Anyone who is not included as part of the ‘we’ simply does not exist. This is convenient for the ‘us’ – while ‘we’ rush excitedly towards a future in which we have more and better, what ‘they’ do is of little concern. The ‘us’ does not care – or even think much – about the ‘them’. The ‘us’ cannot understand why the ‘them’ has not joined the ‘us’. After all, the ‘us’ is at a new threshold – who would not want to reach the other side?

“Personal profiles, passwords, biometrics..fully documented. Every trace filed. Bigger data, better analytics. Opt out, and we lose our place in the world. So…we share the keys to our desire, our habits, to ourselves.”

To be part of the ‘us’ and the ‘we’ requires effort. To ‘opt in’ requires sacrifice. At the same time, ‘opting in’ is the easiest thing in the world when ‘opting out’ means facing a void. Advice on how to do well, how to achieve, how to be healthy is easy to come by, but there is little guidance for those who find themselves, or wish themselves, outside the mainframe. Losing one’s place in the world means losing access to that mainframe and the stability that comes with a highly legible structure. Today the legible structure is far-reaching and well established, to the extent that opting out is dealt with violently. The new models of human coming into circulation have trouble recognising the old. There is a mutual rejection.

“Government regulation stifles amateur culture – military and commercial interests occupy most of the spectrum … transmission becomes a privilege, not a right”

As I wrote earlier, the ‘us’ and ‘them’ structure is too simple. It would be more accurate to think of people as communicating on multiple frequencies. The machinery of society is complicated to say the least, and made more so by the mainframe, which amplifies transmissions at some frequencies while restricting others. In the early 20th Century, multiple obscure radio channels were repressed, responsibility placed with public backlash following rumours that amateur radio was responsible for the sinking of the Titanic. Side questions: where did the rumours come from? What were they based on? How was the public response measured?

“For the first time he hears himself as others do. A voice absolutely familiar but estranged…But her power also grows: by controlling his voice she controls her time”

There is a strange relationship between the controller and the controlled. For every CEO there is a team whose own agenda seeps into the workings of the company. Dislocated power and fragmented or unplaceable identity are some of the symptoms of a complex system undergoing change. When a system is so complex as to involve multiple timescales, spaces, materials and structures, it is impossible to predict the future.

—

Dreams Rewired is part of the Technology is Not Neutral Symposium

3 December 2016

Watermans, London

https://www.watermans.org.uk/events/technology-is-not-neutral-symposium/

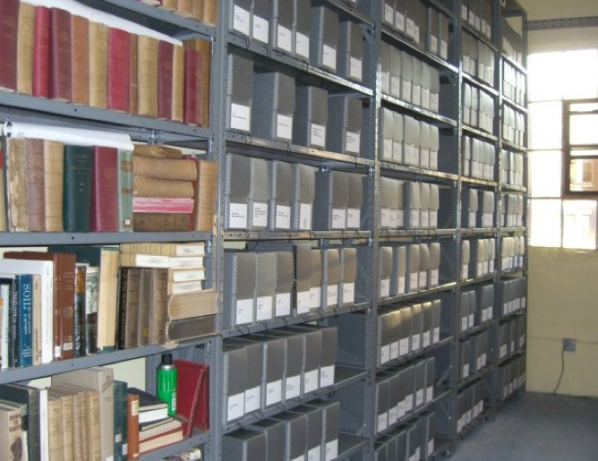

Megan Prelinger is an historian/archivist (originally from Oregon) who in 2004 co-founded a bibliophile’s utopia: the Prelinger Library. Tucked away in the SOMA district of San Francisco–and now highly regarded by researchers from around the world–the library has quietly become a California landmark. The myriads of materials contained there (books and ephemera “geospatially” arranged by Megan and her partner Rick) are made available to the public at least once a week for in-situ use (and one needn’t have academic credentials to enter).

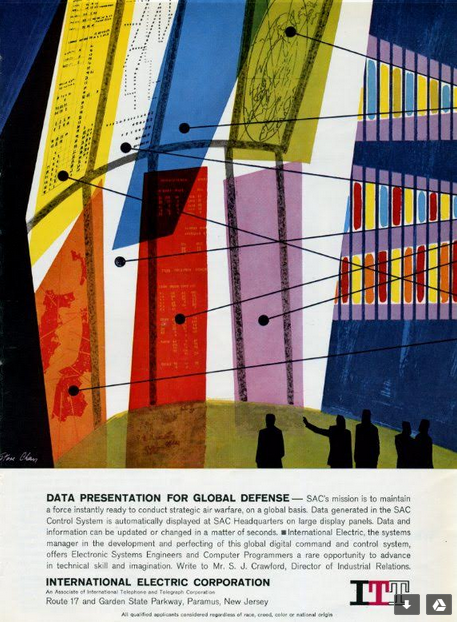

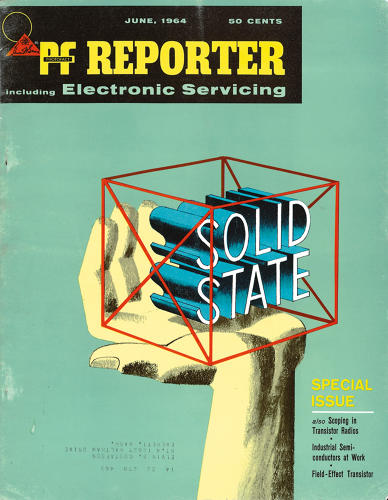

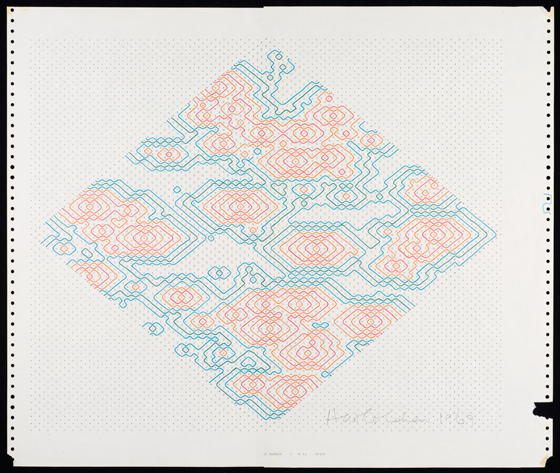

In addition to being a world-renowned sharer (and repairer!) of books though, Megan Prelinger has also authored several. Inside the Machine–her latest work–is a book that traces a visual history of all manner of electronics from roughly the interwar era to the early space age. But it derives its narrative, she says, from exactly and only one source: “the intersection of commerce and graphic art.” As with her previous book (which presents commercial artists’ depictions of early space travel and rocket tech), Inside The Machine is a story told largely through the illustrations that one finds scattered throughout archival tech ephemera–of the sort that line many a shelf at the Prelinger Library. Prelinger’s visually rich book deftly guides the reader through countless innovations that preceded today’s computers, all with an eye towards celebrating the power and reach of the human imagination.

[The following interview was conducted via email.]

Montgomery Cantsin: You say that the Prelinger Library and its community constitute the “rhythmic pulse” which sustains your work as a writer of nonfiction. I wonder if you can say a bit more about that, and how that maybe differs from the situation of many nonfiction writers–that of being ensconced in a bureaucratic university setting. Also, how much of the material in your newest book was discovered there on your own shelves in San Francisco?

Megan Prelinger: During the research and writing of Inside the Machine, between 2011 and 2014, I was simultaneously engaged in a number of projects. You ask about how my situation differs from that of an academic historian: The academic model did not fully “take” in my mind when I was younger. It was introduced to me as one option among many, and I elected take the option of being an independent and self-supporting contributor to the human knowledge project. Throughout the duration of the library project, and my life for that matter, I have therefore always engaged in a number of different types of work more or less simultaneously; types of work that fall in different places on the spectrum between “day job” and freelance artist or knowledge-producer.

My work-week during those Inside the Machine years, as before and since, was a cycle of different forms of research, engagement, and production. The common anchor point around which every week “turns” is the public day in the library that happens every Wednesday. On those public days I set aside my own work and face outward, engaging our library visitors and facilitating their work. The Wednesday community is intellectually sustaining, as hundreds of people every year who are engaged in a universe of different kinds of research-based projects stop by and spend time. Our library is a social library, with discussion being one aspect of the access model. As with visitors, the collaborative relationships I’ve had with our volunteers and artists-in-residence such as yourself have put that library environment at the center of my social, intellectual and creative life since we opened it

To answer the question about how much of the material of the book was discovered on our own shelves: The short answer is “most of it.” There are 184 images in Inside the Machine, I believe, and about 6 of them were sourced from other collections. It was the serendipitous discovery of these overlooked images that drove the research process that became both Another Science Fiction (2010), and Inside the Machine (2015).

MC: I know that your interest in space travel developed in part due to your love of Star Trek as a youth. Is your interest in electronics something that grew out of that? At what point in your career did you realize you were passionate enough about electronics to write a book? …Have you ever tinkered with the insides of machines?

MP: My love of space exploration has many antecedents and you’re correct that Star Trek: TOS is one of them. I was born in 1967 as Season Two was beginning, just in time to be exposed fairly uncritically to a regular stream of images on television that suggested that space exploration was an emerging and “normal” part of everyday life. I remember watching Apollo astronauts explore the Moon on TV, and as a small child formed the unexamined assumption that Star Trek and the Apollo program were in a fact-and-fiction relationship to one another that was analogous to the relationship between the Little House on the Prairie books (fictionalized history) and the real histories of European colonization of North America (fact).

At the same time my dad was away in Vietnam serving in the U.S. Army construction brigades, while my mom was in college studying to be an archaeologist. Mom exposed me to Native American history, and Dad exposed me to the challenges of reintegrating into society as a damaged war veteran. Dad then became an architect. Those two parental models oriented me to the ground-based world that I lived in. I grew up sharply aware of divisions in society because of these two models, and had a sense of myself as an actor in a distinctly ground-based society. I studied anthropology and became a writer in order to develop tools to understand and affect the course of society and history.

The area of my psychogeography that was shaped by visions of space exploration were filled in by science fiction, which formed a bridge between ground-based and space-based spheres. In my thirties I discovered the left-behind literature of the mid-century space industry, and discovered that those handy tools of cultural analysis and writing would enable me to make an original contribution to the cultural history of space exploration. I was gobsmacked by this discovery. It was an unexpected point of integration between realms of my intellectual life and psychogeography that had previously been united only in the lifelong practice of reading and appreciating science fiction.

Coincidentally, in the course of taking that degree in anthropology I was required in college to take a year of science as a distribution requirement. This was actually a wish come true, since part of me had wanted to be a math major from the beginning but I lacked the background to do college-level math. That year-long general science course for non-science majors was possibly my favorite class in college. One third of the years’ curriculum was devoted to exploring electronics, understanding how circuits worked, learning to read circuit diagrams, and ultimately building a simple working radio out of found materials.

When my research on the cultural history of space exploration led me to try to understand space electronics, that history was invaluable. My passion to understand electronics grew directly out of a desire to understand why space exploration technologies matured when they did, apart from geopolitics and funding streams. When I realized that space exploration in the 1950s was reliant on the simultaneous development of very large-scale computers (mainframes) and very small-scale computers (the miniaturization made possible by the transistor), I then felt an overwhelming impulse to share what I had learned with other people. Inside the Machine ended up with a space electronics chapter in the 8th position (out of 9 chapters), but space electronics was the starting point in my research and the rest of the book mushroomed out from it.

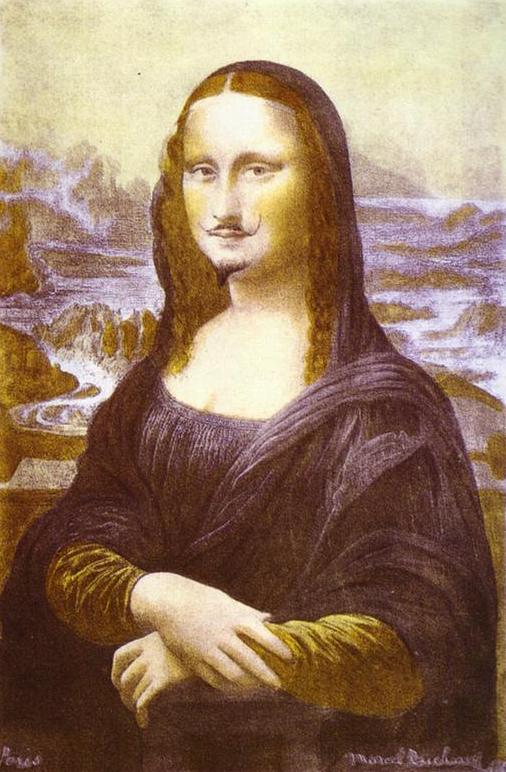

MC: The artists whose work is featured in your book (often anonymous at the time) were given the job of depicting a reality that exists, as you say, “behind reality.” You point to the inherent surrealism of such a task–can you expand on that? …You also note that in 1935, when the electric signals in the human brain were first detected, the study of the electricity, etc, was considered to be “a new assault on the mystery of life…”

MP: The study of the relationship between electricity and the human body is still pretty new. In fact, one reason that I wrote the book is that the future of the practical integration between electronics and the body could be immense enough that its recent history would be overshadowed. That history is already not commonly understood, even as people are increasingly symbiotic with their devices. I wrote the book to serve as a prehistory to counter any historical amnesia that may be induced by possible futures.

The scientific verification, in 1935, that life is reliant on a flow of electricity through the body, proved and extended an idea that Mary Shelley was working with in Frankenstein. Tracing the historical literature it’s interesting to watch the dialogue between electricity and the body migrate out of subcultures and into mainstream hard science over the past 200 years. I’m referring to subcultures like science fiction and also 19th-century experimental para-medical techniques, such as dosing people with electrical current to improve their health. That relationship was subjected to the changing standards of rigor around medical and scientific investigations over the 20th century. Today, work on electronic circuits that could have biomedical applications and that could actually be ingested and dissolved within the body is at the forefront of such research. Assuming that such circuits are developed and proven useful, I wouldn’t be surprised if they came to be a dominant biomedical technology.

When I say “behind reality” I’m referring most literally to the invisibility of the electron stream. While electricity can be made visible as illumination, the flow of electrons through electronic devices, on the other hand, is invisible. Hence, “Inside the Machine.” For a time the components that channeled the flow of electrons, such as vacuum tubes and switches, were visible on the inside of radio cabinets. Some 1930s radio cabinet designs deliberately revealed the circuit board in a gesture to demystify the flow of electrons and glamorize the components. That short window of visibility, however, quickly retreated in the face of ever more complex circuits and ever more “built” environments that housed them. The cultural signification around electronics came to be centered on the integral devices: radio, TV, and eventually computers and everything that flows from them. I felt that there was a cultural history of the components that combine to form electronic devices that needed to be told, and that it was the graphic artists and illustrators working for industry who had made that cultural history–a history that it became my job to expose and interpret for a contemporary audience.

At a more philosophical level, the flow of electrons multiplied our senses. By forming invisible channels through which sounds and images were carried and replicated, electronics created a hierarchy of sense perceptions that had immediate cultural and political significations. How else to characterize that phenomenon besides surreal? Coincidentally the fine art movement known as Surrealism emerged in the 1920s and radios very shortly thereafter, coming to market in the late 20s and exploding in popularity during the 1930s. Think of it this way: multiple electromechanical eyes, faces, ears, and mouths populating homes, offices, and streets, in the form of a proliferation of new gadgets. The world filling with sense receptor multipliers everywhere you look. A mountaintop may be media in the sense that it opens up a perspective impossible to gain any other (unassisted) way, but a climb up a mountain is a unique event offering a unique perspective. Electronic media, in contrast, are most profound in their most ordinary distinguishing feature, which is their simultaneous multiplicity.

MC: You bring up Lewis Mumford in the book, saying that he regarded the craftperson’s bench as a sort of “bridge between art and applied skill.” To what degree has Mumford’s work influenced your thinking?

MP: I discovered the work of Lewis Mumford back in high school and appreciated his broad-spectrum thinking on a range of ground-based systems, like cities and highways. (The first book of his that I read was The Highway and the City.) Back in high school it was a novelty to me that subjects like freeways and cities were written about as subjects in their own right. They hadn’t been previously represented in any spectrum of “subjects” that I had been exposed to. I also liked about Mumford that he incorporated ecological thinking into his philosophies of the built environment, and that his environmental politics predated, and therefore did not fit into, contemporary modes of approaching those subjects.

When it came to writing Inside the Machine, I drew on Mumford, who had once been a radio engineer, as a historian of technology (or “technics” in his parlance). His work to elaborate the relationship between fine art and applied art expressed by the craft bench was a needed historical context for discussing the relationship between craft and art.

MC: The constant need for an “enlargement of the military field of perception” has been hugely responsible for innovations in moving-image technology (I am quoting here from Paul Virilio’s book War and Cinema–which I found on your shelves). I wonder how things might have developed differently if such had not been the case? (In other words, if R&D had been guided by the Teslas and the Martenots of the world instead of by Westinghouse, the Pentagon, etc.).

MP: Well… the need for an enlargement of the military field of perception may have been responsible for innovations in moving-image technology, but it must exceed that in the extent to which it influenced space technology! The original satellite programs around the world, both USSR and US, were funded and dedicated to that purpose.

To get back directly, though, to the question you pose: It’s one that opens the door to many interesting possible alternate realities. That’s one reason I became so deeply focused on the work that fine and applied artists did to paint the future of new technologies. If I can make a blanket characterization of those artists as a group: I don’t think they were motivated to pick up a pencil or brush by a desire to enlarge the military field of perception! Instead they were creating all kinds of hybrid visions of the future, including pastoral and surrealist elements that addressed the multiplication of the senses in very humane terms.

There are perhaps more examples of the possibilities you suggest than you might think. For example: the influence of Hugo Gernsback, for whom the science fiction Hugo award is named. Gernsback was an active futurist who promoted science fiction and speculative futures through the mass publication of a wide range of pulp fiction magazines. At the same time he was a serious radio and TV pioneer who founded a radio station, experimented with early television broadcasting, and published “straight” news and craft magazine for radio professionals and amateurs alike, such as Radio-Electronics and Science and Mechanics to name just two. His “straight” news and craft magazines typically had a futurist-oriented editorial edge; one that was uninterested in mapping problems or limits or real-world geopolitics onto the emergence of new technologies. I don’t doubt that Gernsback’s influence was a shaping force on the emergence of electronic technology in ways that may not be fully understood for years. I don’t mean to dwell on Gernsback — he’s been widely written about in histories and biographies and I have never felt the call to add much to his hagiography. But I’m mentioning him here to directly respond to your query of “What if (R&D had been guided by the Teslas and the Martenots of the world)”. One more note: Tesla’s name was not attached to his invention in the way that Edison’s was, but he did invent AC (alternating current). Given that most people in the industrialized world use AC every day, I would argue that Tesla did guide the research and development of some of the essential infrastructure of everyday life.

MC: Toward the end of the book you wonder whether computers will someday be “grown” instead of built. Sounds cool! Brings to my mind certain left-field figures such as Bern Porter. …Porter chose to drop out of professional science (to pursue DIY “sci-art” and many other things) after having worked on the Manhattan Project. I thought of him while looking at your book, since he is also said to have helped develop the cathode ray tube. …I am curious, what you may have learned about humanity’s future by delving into all these inventions of the past?

MP: In crafting that conclusion I was putting together a few different pieces of real evidence and combining them in a hypothetical exercise. I didn’t think it was that crazy. Consider the following verifiable phenomena: The biomedical circuits that can be ingested and dissolved in the human body; the capacity of mycelia networks–underground networks of fungal bodies—to effectively redistribute nutrients between different plants in the soil; the published theory that life itself may have emerged from primordial clay (not “soup”); the wisdom of permaculture.

I’ve read widely about all these phenomena, and other related phenomena. When I try to visualize an answer to the problem of toxic chemicals and heavy metals bound up in electronic devices, it seems reasonable to me that a hundred years from now, or maybe even only twenty years from now, people will have figured out how to extract computational functions from some combination of these kinds of existing features of the natural world. Or will have developed some intelligent permaculture that can perform media functions at the same time as producing food.

Or, never mind organic phenomena, what if all the essential elements of sand, stone, glass, (plastic) and metal that form electronic machines could be formulated and constructed to smartly dematerialize when they were no longer needed? What if you could drop a laptop into special bin that would use magnets and clean biochemical processes to disassemble all those building blocks, and distill them into measured piles and vials of raw materials for new machines?

Maybe I’ve read too much science fiction… but I’d prefer to believe that I’ve just read too much history to feel that the possibilities for the future are in any way fixed or limited. In human history–in natural history too, for that matter–epochal shifts happen sometimes “overnight” (at least in geological or historical senses), usually from the emergence of a new phenomenon that results from combined antecedents that were hidden below the surface until abruptly transformed and brought to daylight. There’s no reason to think that the dirty century of the 20th/21st centuries couldn’t experience an abrupt paradigm shift in favor of a very different kind of model.

Choose Your Muse is a series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

Annie Abrahams was born in the Netherlands to a farming family in a rural village in the Netherlands. In 1978 she received a doctorate in biology and her observations on monkeys inspired her curiosity about human interactions. After leaving an academic post she trained as an artist and moved to France in 1987, where she became interested in using computers to construct and document her painting installations. She has been experimenting with networked performance and making art for the Internet since the mid 1990s. Her works have been exhibited and performed internationally at institutions such as the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, New Langton Arts in San Francisco, Centre Pompidou in France, Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki and many other venues.

Through the years we have got to know Annie Abrahams via various online, networked artistic collaborations. In 2010, she had a her first one woman show If not you not me in the UK at Furtherfield’s earlier gallery space, the HTTP Gallery. Since then, she has shown at another mixed show at Furtherfield’s current space in Finsbury Park, London. This exhibition, Being Social included other artsists such as Karen Blissett, Ele Carpenter, Emilie Giles, moddr_ , Liz Sterry, and Thomson and Craighead.

She is known worldwide for her net art and collective writing experiments and is internationally regarded as a pioneer of networked performance art. She creates situations that reveal messy and sloppy sides of human behaviour; capturing real-time moments to illucidate a reality and opening it up, making it available for thought. In an interview with Bomb Magazine in 2014 Abrahams said “My first online performance was my first HTML page. Even then I considered the Internet to be a public space, and everything that I did in that public space asked for a reaction.” [1]

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Annie Abrahams: Life itself, the people I meet. Until now my basic needs in life have hardly been threatened and so the only real problems I encountered were relational problems. Who are you? Why are you different from me? What does it mean to respect you? Is opposing you necessary? And if so, how can I do that?

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

AA: My practice was always based on the difficulty of having to live in a world where I don’t understand anything. Every person I meet opens up another view on this impossibility. Sometimes I write short posts about my encounters. Lately I did one on Shirley Clarke and one on Ed Atkins’ No-one is more “Work” than me. aabrahams.wordpress.com

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

AA: My work is made from these influences. In the beginning I thought this was not ok, because I was educated with the idea that you have to be “unique” and make unique artworks. But now I am proud of my sensibility for what others say and do and the way I work with that.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

AA: Last summer I made a book called from estanger to e-stranger. Ruth Catlow described it as “all-at-once instruction manual, poetry and a series of vignettes of contemporary encounters in language-less places”. There you can find ideas and art works that inspire me, but in general I am not driven by inspiration, my acts are driven by irritation, my art by incomprehension. Art works sooth, make things bearable and sometimes incite to look beyond habits. Btw I am still continuing my research on how language shapes culture, society and me. http://e-stranger.tumblr.com/

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

AA: Stay close to your own concerns, to things you can have a concrete influence on, observe the results of your actions, pay attention, adapt, and always smile to your neighbour in the morning.

MG: Could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for readers to view, and if so why?

AA: For years now every now and then I’ve come back to Darren O’Donnell’s book “Social Acupuncture” and always again I say to myself, “yes, you can think and act art and politics together. Please have a look at the Mammalian Diving Reflex group’s (he is their artistic director) methods. http://mammalian.ca/method/

Body Drift: Butler, Hayles, Haraway (Posthumanities)

Author Arthur Kroker. University of Minnesota Press (22 Oct. 2012).

Body Drift by Arthur Kroker, takes the work of three leading women thinkers as its main focus. It therefore would feel strange, before venturing on to the review, not to mention Marilouise Kroker, his wife and collaborator who he credits with shaping the critical direction of his thought “on bodies and power.” [1] Together Marilouise and Arthur Kroker have created an abundance of work in the fields of technology and contemporary culture. They both edit the peer publishing electronic journal CTheory founded in 1996. They co-authored the influential Hacking the Future (1996), and Marilouise Kroker has co-edited and introduced numerous anthologies including Digital Delirium (1997), Body Invaders (1987), and Last Sex (1993) and Critical Digital Studies: A Reader. Marilouise Kroker is Senior Research Scholar at the University of Victoria. A recent bio written about them says “Arthur and Marilouise Kroker are the hipsters of Canadian media theory.” [2]

Arthur Kroker is Canada Research Chair in Technology, Culture and Theory, Professor of Political Science, and the Director of the Pacific Centre for Technology and Culture (PACTAC) at the University of Victoria. His recent publications include The Will to Technology and the Culture of Nihilism: Heidegger, Nietzsche, and Marx (University of Toronto Press) and Born Again Ideology: Religion, Technology and Terrorism. Dr. Kroker’s current research focuses on the new area of critical digital studies and the politics of the body in contemporary techno-culture. http://web.uvic.ca/~akroker/

This review is written three years after the publication of the book but it feels even more relevant now than ever for reasons that will, I hope become plain…

Body Drift focuses on three major feminist theorists, Judith Butler, Katherine Hayles and Donna Haraway. They have had a deep influence on my own work and of course on media art culture through the years. They have profoundly altered our views on technology, feminism, queer theory, postmodernism, marxism, hacking, hacktivism, cybernetics, the Internet, network culture, politics and posthumaniism. Re-examining their critical perspectives and creative processes – assemblages, remixing and cyborgs- Kroker terms the emerging technological spectre body drift. He examines the connections between what he sees as Judith Butler’s postmodernism, Katherine Hayles’s posthumanism, and Donna Haraway’s companionism.

Through the spectrum of Body Drift he attempts to find a clearer understanding of the contemporary material body and its societal complexities. He views two opposing forces at work in body drift. One is, the continual disappearance of human things and values, alongside excluded ethnicities and outlawed sexualities. He connects this with an entrapment by social crisis in which actual democratic aspiration is dwindling. In parallel to this mass loss of our freedoms other factors are at work. He sees it as overall, and an eventual series and states of resistances. These are evolutionary forms of hybridity and as such are key paths for what he argues is the function of our posthuman condition. [3]

There are numerous techno-visions expounding how technology will change our lives and futures. What for me, separates a classic posthumanist and a critically aware posthumanist is that the latter is not only aware of the necessity of grass roots culture and inclusion of female voices, but is also critical of domination over others as key when engaging in the processes of innovation. Thus moving beyond existing frameworks that perpetuate patriarchal language, methods of centralization and colonial habits.

In his book You Are Not A Gadget: A Manifesto, Jaron Lanier described Ray Kurzweil’s excitement about The Singularity as apocalyptic. Lanier says “The coming Singularity is a popular belief in the society of technologists. Singularity books are as common in a computer science department as Rapture images are in an evangelical bookstore.” [4] Kurzweil’s digestible techno-bites fit well alongside big business and with Peter Diamandis a wealthy entrepreneur. Dr. Peter H. Diamandis and Dr. Ray Kurzweil co-founded the Singularity University. In To Save Everything, Click Here: Technology, Solutionism, and the Urge to Fix Problems that Don’t Exist, Evgeny Morozov writes that Diamandis “promises us a world of abundance that will essentially require no sacrifice from anyone – and since no one’s interests will be hurt, politics itself will be unnecessary.” [5]

In The Joy of Revolution Ken Knabb wrote, “Marx considered it presumptuous to attempt to predict how people would live in a liberated society. “It will be up to those people to decide if, when and what they want to do about it, and what means to employ.”” [6] Kroker says, “In my estimation, while Marx, Nietzsche and Heidegger may have provided premonitory signs of the charred landscape of the technological blast, it is the specific contribution of Butler, Hayles and Haraway to provide a deeply compelling account of the fate of the body in contemporary society.” [7] This includes how we evolve our Internet freedoms, surveillance, and cyber attacks in a post-Snowden world. While we’re, either reshaping or being reshaped through the constant production of new technologies and political re-invention, it is crucial that there exists regular critique reflecting on these influences and changes on people, animals, society, the planet, and the universe. Thankfully, Butler, Hayles and Haraway disrupt the normalization and dangerously hegemonic acceptance of ‘the male overlord and his machine’ over the rest of us.

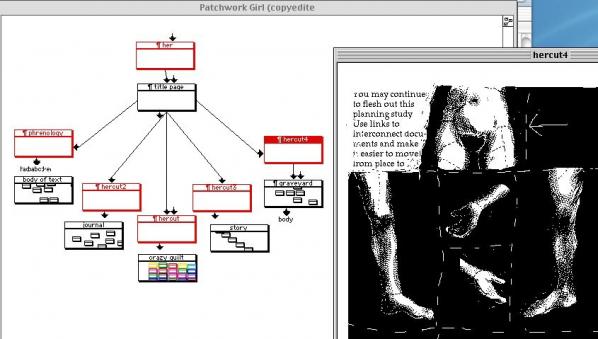

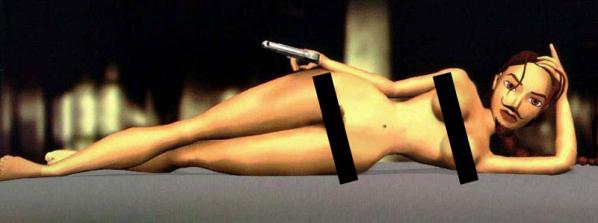

How our bodies and the idea of our bodies relate to this complex world is Kroker’s primary interest. In the introduction Kroker says that we no longer inhabit a body in any meaningful sense of the term but rather occupy a multiplicity of bodies – imaginary, sexualized, disciplined, gendered, laboring technologically augmented bodies. [8] Hayles has not only bridged the gap between science and literature, but also media art. In 2000, Hayles wrote an insightful piece on Patchwork Girl, an artwork made by Shelley Jackson in 1995, a hypertext fiction and remix of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. When discussing Jackson’s piece Hayles said, “As the unified subject is thus broken apart and reassembled as a multiplicity, the work also highlights the technologies that make the textual body itself a multiplicity.” [9]

Kroker says, “”Like Heidegger before her, Hayles refuses to privilege either interpretation to the exclusion of its opposite, preferring a form of thought similar to “pendurance,” that moment when, in the folded twists of complexity theory, “one comes over the other, one arrives in the other.”” [10] In an interview with Josephine Bosma on the Nettime email list, in Nov 1998, Hayles said “There may be other ways to think about the subject that don’t find themselves first and foremost on this notion of ownership. New technologies open up possibilities for rethinking other ways to begin to construct the subject.” [11] Krokers sees Hayles as providing us with the digital alphabet to explore the complexity and connections of technopoesis. “To read Hayles is, in fact, to begin to experience the fractures, bifurcations, and liminality that stretches across the skin of posthuman culture.” [12]

Donna Haraway in her introduction to A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century, in 1985 she said, “Though both are bound in the spiral dance. I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess.” This unsettled many feminists at the time. Haraway was not interested in reclaiming what she saw as a lost ideal based on matriarchal values. Instead, she wanted women to re-invent and create their own versions of what a female could be or not be, by playfully exploiting the cyborg myth and concept in the here and now. [13] This reconstruction of the woman, Kroker says, poses particular twists and knots, and contradictions. He emphasises that we’re not discussing a traditional form of feminism but a hybrid vision of feminism. [14]

“Not waiting passively for the capricious experience of biotechnology to produce spliced bodies, Haraway has made of her own mind a biopolitics on creative hyperdrive. Deeply immersed in the (bio)scientific disciplines, always distancing herself from seductions of technological representationality by feminist difference, continuously provoking boundary breakdowns in her own thought by refusing to assent to an anthropomorphic species-heirarchy, Haraway is a theorist of the splice.” [15] Kroker (2012)

Kroker moves on from Haraway’s concepts on the cyborg to her later inter-species theory. He tries to untangle the complexity of her personal, political and theoretical relations in respect to where her critical strength is best engaged. He’s drawn to what he sees as ““Haraway’s profound conceptualization of “companion species.”” Haraway challenges the established role and hierarchical control by us humans over animals, plants, objects, and humans. [16] In her publication The Companion Manifesto: Dogs, People, And Significant Otherness, Haraway says, “I believe that all ethical relating, within or between species, is knit from the silk-strong thread of ongoing alertness to otherness-in-relation.” [17]

Haraway’s text in The Companion Manifesto conveys a shocking sense of freedom as if written by someone who longer gives a damn about her academic reputation. Perhaps, what I mean here is that the thinking reaches further than academia and builds alliances with others who may not have read her other works. In the chapter A Category of One’s own, Haraway says, “Anyone who has done historical research knows that the undocumented often have more to say about how the world is put together than do the well pedigreed.” [18] As with her concept for Situated knowledges her intention is to connect beyond officially accepted canons and norms, and established hegemonies. In his chapter HYBRIDITIES Kroker says “Haraway’s writings reveal the apocalypse that is possibly the end condition of hundreds of years of (Western) scientific experimentalism.” [19] This does not mean the West is doomed. However, Haraway has always been on the side of otherness, whether for humans or nonhuman entities. In her eyes our futures or the world as it actually is may not necessarily be as reliant on technology as we like to think.

“Perhaps most importantly, we must recognise that ethics requires us to risk ourselves precisely at moments of unknowingness, when what forms us diverges from what lies before us, when our willingness to become undone in relation to others constitutes our chance of becoming human.” [20] Judith Butler.

Of this quote from Butler’s Giving an Account of Oneself, 2005 [21], which opens the second chapter in Body Drift, Kroker says, “Could there be any text more appropriate to both understanding and perhaps, if the winds of fate are favorable, transforming contemporary politics than Judith Butler’s eloquent study of moral philosophy..?” [21] In Giving an Account of Oneself, Butler presents us with an outline for a different type of ethical practice and proposes that, before you even ask what ought I to do? Ask yourself the question who is this ‘I’? Butler, proposes that it is “a matter of necessity” that every person should “become a social theorist.” [22] Indeed, in the City Lights interview with Peter Maravelis, Kroker says Butler is speaking in terms of people breaking their silence, such as “the repetition chorus of OCCUPY during the Wall Street insurrection”. [23] And then he says, “In many ways, all of Butler’s thought is “standing as witness.” [24] Butler stands witness to what we now know in the 21st century as a violent regime of heterosexual masculinity spreading its domination over history, technology and life itself.

Butler, Hayles and Haraway are major players in feminist and queer academia and media art culture. They have all been active in breaking away from the traditional behaviours that have kept us caught within loops in various ways. Their fluid and progressive approaches to feminism are not only of value to women alone but it can also help others think beyond restrictive behaviours. Kroker’s book manages to reflect the fluidity of networked and contemporary aspects of body drift well, especially from a critically aware, posthumanist perspective. However, no matter how you slice it, it’s about personal and collective freedoms, how we can somehow reclaim our states of being, and how we can own our subjectivities and our psyches in whatever forms these may take. As artists, as humans and or as posthumans – we need Butler, Hayles and Haraway to guide us through this ever-changing, twisting, everyday, posthuman terrain.

Choose Your Muse is a new series of interviews where Marc Garrett asks emerging and established artists, curators, techies, hacktivists, activists and theorists; practising across the fields of art, technology and social change, how and what has inspired them, personally, artistically and culturally.

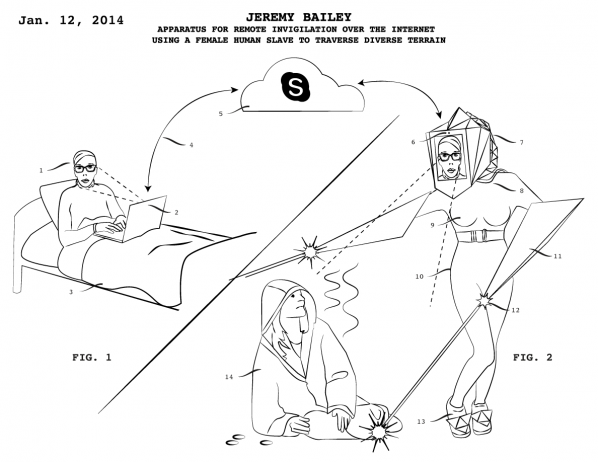

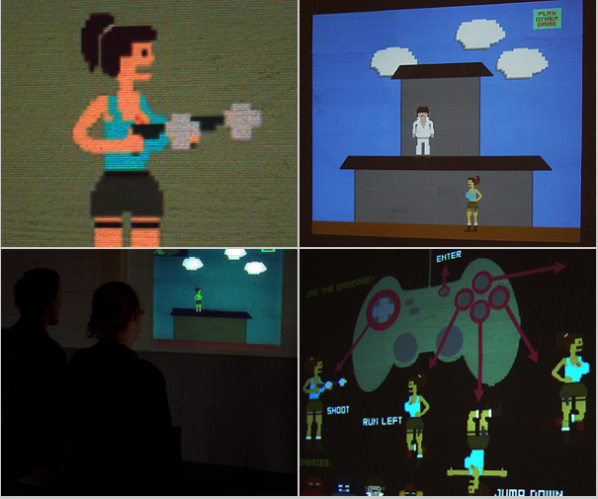

Jeremy Bailey is a Toronto based Famous New Media Artist. Recent projects include performances for Rhizome’s Seven on Seven in New York, The Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and Tate Liverpool. Recent exhibitions include solo exhibitions at Transmediale in Berlin, and group exhibitions at Mediamatic in Amsterdam, Museums Quartier in Vienna and Balice Hertling in Paris. Recent commissions include projects for FACT in Liverpool, Turner Contemporary in Margate UK, and The New Museum in New York.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

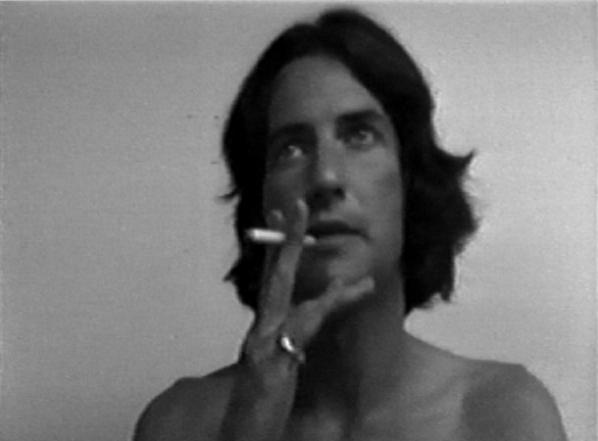

Jeremy Bailey: Many have inspired my work but likely the most inspiring has been Canadian video performance artist Colin Campbell. He introduced me to video art and video art history as a young university student in Toronto. He made work that was funny, that lampooned the art world and somehow also made art more relevant to my young eyes. Looking back much of what I aspire to do today is directly reflective of what Colin exposed me to so early on.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

JB: Absolutely, in my own work I’m often self deprecatingly self reflective of the absurd circumstances and pathos of a new media artist eking out a career against all odds.

One of my all time favourite videos by Colin Campbell is Sackville I’m Yours, in it he plays a small town art celebrity named “Art Star” who conducts a hilariously pathetic mock interview of himself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKEzRWgih78

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

JB: My video performance work differs from Colin’s because it was created as video for the Internet where his work was created in the 70s, 80s and 90s, a time where all video ended up on a TV monitor. This is an important distinction, because a lot of early video art was positioned in dialogue with the history of television. The personal narrative, the idea of a non celebrity on TV, that was a new idea. In contrast the Internet was designed from the very beginning to be accessible platform for self expression and distribution. Growing up with the Internet I can remember always feeling like anyone could be famous. No matter how niche or weird you were there was always an audience on the internet. Before I was an artist I was actually known online as a skin designer. Skins were these custom interfaces you could add to your software, usually music software, to make it your own. You can still see my skin designs from that era here http://sblcommunications.com/jbd/

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

JB: Yes, I’d like art to reflect positive social change instead of reflecting negative market demands. Artists have this tremendous ability and power to communicate and many are wasting that talent pandering to the decorating desires of the rich and powerful. I understand that everyone needs to make a living, but we also have a responsibility as artists to help make the world a better place. I also don’t see why these two things need to be in conflict.

Above image from The You Museum. It was “conceived of in Istanbul during a memorable residency at The Moving Museum that resulted in an exhibition you can read a review of here. The You Museum was inspired by Istanbul’s Gezi Park protests, and the ongoing debates and conflations of public and private entities and spaces in Turkey and abroad (notably by organizations such as the NSA)”

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

JB: Nearly all of my work is inspired by real life, I often reflect my actual circumstance in my work. My process usually involves searching for a problem and then satirically using technology to solve it poorly. In doing this I usually uncover other problems that run deeper than the initial surface issues. For example I was once invited to do a residency in an impoverished town in the Ukraine where I discovered an unpopular but bureaucratically permanent statue of Stalin in the town square. To help solve the problem of a permanent and unpopular statue I created software that allowed anyone to easily create their own wearable public sculpture that they could change anytime by screaming. This admitedly pathetic solution allowed me to navigate a number of other issues, everything from my family history to the role of art in relation to capital to the subjectivity of historical document. I’m always feeding off and reflecting the world around me. Reality is so much crazier and more interesting than anything I could invent.

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and social change?

JB: This one is obvious, but hard to follow. Don’t be afraid to fail. Failing will help you learn and grow to be a better artist tomorrow. No one ever remembers your failures as well as you do – especially when your new work is good.

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

JB: I’m reading a book today called To Save Everything Click Here by Evegeny Morozov about our culture’s obsession with technology as a go to solution for the world’s problems. Most of my work is about this very human hope that someone else has solved or will solve our problems, and many of us believe those people work in technology companies. That’s simply not true. In the book Morozov coins the term Solutionism to describe this mentality. Much of my own work could be called solutionist satire I guess, but the bottom line is we’re all capable of being a part of the solution, of making the world around us better. Ideology, good ideas, have done more to change our world for the better than any technology ever will.

J. R. Carpenter reviews A Geology of Media, the third, final part of the media ecology-trilogy. It started with Digital Contagions: A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses (2007) and continued with Insect Media (2010). It focuses beyond machines and technologies onto the chemistry and geological materials of media, from metals to dust.

Humans are a doubly young species — we haven’t been around for long, and we don’t live for long either. We retain a fleeting, animal sense of time. We think in terms of generations – a few before us, a few after. Beyond that… we can postulate, we can speculate, we can carbon date, but our intellectual understanding of the great age of the earth remains at odds with our sensory perception of the passage of days, seasons, and lifetimes.

The phrase ‘deep time’ was popularised by the American author John McPhee in the early 1980s. McPhee posits that we as a species may not yet have had time to evolve a conception of the abyssal eons before us: “Primordial inhibition may stand in the way. On the geologic time scale, a human lifetime is reduced to a brevity that is too inhibiting to think about. The mind blocks the information”1. Enter the creationists and climate change deniers, stage right. On 28 May 2015 the Washington Post reported that a self-professed creationist from Calgary found a 60,000-million-year-old fossil, which did nothing to dissuade him of his religious beliefs: “There’s no dates stamped on these things,” he told the local paper.2

In the late 15th-century, Leonardo Da Vinci observed fossils of shells and bones of fish embedded high in the Alps and privately mused in his notebooks that the theologians may have got their maths wrong. The notion that the earth was not mere thousands but rather many millions of years old was first put forward publicly by the Scottish physician turned natural scientist James Hutton in Theory of the Earth, a presentation made to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1785 and published ten years later in two massive volumes3. It is critical to note that among Hutton’s closest confidants during the formulation of this work were Joseph Black, the chemist widely regarded as the discoverer of carbon dioxide, and the engineer James Watt, whose improvements to the steam engine hastened the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. Geology emerged as a discipline on the eve of a period of such massive social, scientific, economic, political, and environmental change that it precipitated what many modern geologists, ecologists, and prominent media theorists are now categorising as a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. As Nathan Jones recently wrote for Furtherfield: “The Anthropocene… refers to a catastrophic situation resulting from the actions of a patriarchal Western society, and the effects of masculine dominance and aggression on a global scale.”4

In his latest book, A Geology of Media (2015)5, Finnish media theorist Jussi Parikka turns to geology as a heuristic and highly interdisciplinary mode of thinking and doing through which to address the complex continuum between biology and technology presented by the Anthropocene. Or the Anthrobscene, as Parikka blithely quips. In putting forward geology as a methodology, a conceptual trajectory, a creative intervention, and an interrogation of the non-human, Parikka argues for a more literal understanding of ‘deep time’ in geological, mineralogical, chemical, and ecological terms. Whilst acknowledging the usefulness of the concepts of anarachaeology and varientology put forward by Siefried Zielinski in Deep Time of the Media (2008)6, Parikka calls for an even deeper time of the media — deeper in time and in deeper into the earth.

In Theory of the Earth, Hutton referred to the earth as a machine. He argued: “To acquire a general or comprehensive view of this mechanism of the globe… it is necessary to distinguish three different bodies which compose the whole. These are, a solid body of earth, an aqueous body of sea, and an elastic fluid of air.”13 Of the machine-focused German media theorists, Parikka demands – what is being left out? “What other modes of materiality deserve our attention?”7 Parikka proposes the term ‘medianatures’ — a variation on Donna Haraway’s ‘naturecultures’8 — as a term through which to address the entangled spheres and sets of practices which constitute both media and nature. Further, Parikka reintroduces aspects of Marxist materialism to Friedrich Kittler’s media materialist agenda, relentlessly re-framing the production, consumption, and disposal of hardware in environmental, political, and economic contexts, and raising critical social questions of energy consumption, labour exploitation, pollution, illness, and waste.

Drawing upon Deleuze and Guattari’s formulation of a ‘geology of morals’9, Parikka writes: “Media history conflates with earth history; the geological materials of metals and chemicals get deterritorialized from their strata and reterritorialized in machines that define our technical media culture”10. Within this geologically inflected materialism, a history of media is also a history of the social and environmental impact of the mining, selling, and consuming of coal, oil, copper, and aluminium. A history of media is also a history of research, design, fabrication, and the discovery of chemical processes and properties such as the use of gutta-percha latex for use the insulation of transatlantic submarine cables, and the extraction of silicon for use in semiconductor devices. A history of the telephone is entwined with that of the copper mine. How can we possibly think of the iPhone as more sophisticated than the land line when we that know that beneath its sleek surface – polished by aluminium dust – the iPhone runs on rare earth minerals extracted by human bodies labouring in deplorable conditions in open-pit mines?

Jussi Parikka is a professor in technological culture and aesthetics and Winchester School of Art. Although his his definition of media remains rooted in the disciplinary discourses of media studies, media theory, media history, and media art, he advocates for and indeed actively engages in an interdisciplinary approach to media theory. He cites a number of excellent examples from contemporary media art, not as illustrations of his arguments but rather as guides to his thinking. He also draws upon a wide range of other references from visual art, science, literature, psychogeography, philosophy, and politics. This overtly interdisciplinary approach to media theory provides a number of intriguing openings for readers, scholars, and practitioners in adjacent fields to consider. For example, Parikka’s evocation of Robert Smithson’s formulation of ‘abstract geology’11 in relation to land art invites further explication of the connection between land art, sculpture, and the geology of sculptural media. For thousands of years sculptors have practised a geology of media, making and shaping clay, quarrying and carving stone, and smelting, melting, and casting metal. Further, Parikka’s discussion of the pictorial content of a number of paintings in the context of this book invites the consideration of the geology of paint as a medium, entwined with the elemental materiality of cadmium, titanium, cobalt, ochre, turpentine, graphite, and lead.

Media is a concept in crisis. As it travels across scientific, artistic, and humanistic disciplines it confuses and confounds boundaries between what media is and what media does in a wide range of contexts. This confusion signposts the need for new vocabularies. If geology has taught us anything, it’s that this too will take time. In endeavouring to explain how it happens that flames sometimes shoot out through the throat of Mount Etna, the Epicurian poet Lucretius (c. 100 – c. 55 BC) wrote: “You must remember that the universe is fathomless… If you look squarely at this fact and keep it clearly before your eyes, many things will cease to strike you as miraculous.”12 So too, Parikka prods us to think big, to get past our primordial inhibitions, to look beyond mass media consumerism to what I shall call a ‘massive media’ – a conception of media operating on a global and geological scale. A Geology of Media is a green book, overtly ecological. In his call for a further materialisation of media theory through a consideration of the media of earth, sea, and air Parikka has put forward an assemblage of material practices indispensable to any discussion of the mediatic relations of the Anthropocene.

Daniel Rourke: At Furtherfield on November 22nd 2014 you launched a Beta version of a networked project, 6PM Your Local Time, in collaboration with Fabio Paris, Abandon Normal Devices and Gummy Industries. #6PMYLT uses twitter hashtags as a nexus for distributed art happenings. Could you tell us more about the impetus behind the project?

Domenico Quaranta: In September 2012, the Link Art Center launched the Link Point in Brescia: a small project space where, for almost two years, we presented installation projects by local and international artists. The Link Point was, since the beginning, a “dual site”: a space where to invite our local audience, but also a set for photographic documentation meant to be distributed online to a global audience. Fabio Paris’ long experience with his commercial gallery – that used the same space for more than 10 years, persuaded us that this was what we had to offer to the artists invited. So, the space was reduced to a small cube, white from floor to ceiling, with neon lights and a big logo (a kind of analogue watermark) on the back door.

Thinking about this project, and the strong presence of the Link Point logo in all the documentation, we realized that the Link Point was actually not bound to that space: as an abstract, highly formalized space, it could actually be everywhere. Take a white cube and place the Link Point logo in it, and that’s the Link Point.

This realization brought us, on the one hand, to close the space in Brescia and to turn the Link Point into a nomad, erratic project, that can resurrect from time to time in other places; and, on the other hand, to conceive 6PM Your Local Time. The idea was simple: if exhibition spaces are all more or less similar; if online documentation has become so important to communicate art events to a wider audience, and if people started perceiving it as not different from primary experience, why not set up an exhibition that takes place in different locations, kept together only by documentation and by the use of the same logo? All the rest came right after, as a natural development from this starting point (and as an adaptation of this idea to reality).

Of course, this is a statement as well as a provocation: watching the documentation of the UK Beta Test you can easily realize that exhibition spaces are NOT more or less the same; that attending or participating in an event is different from watching pictures on a screen; that some artworks work well in pictures but many need to be experiences. We want to stress the value of networking and of giving prominence to your network rather than to your individual identity; but if the project would work as a reminder that reality is still different from media representation, it would be successful anyway.

Daniel Rourke: There is something of Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zones in your proposal. The idea that geographic, economic and/or political boundaries need no longer define the limits of social collective action. We can criticise Bey’s 1991 text now, because in retrospect the Internet and its constitutive protocols have themselves become a breeding ground for corporate and political concerns, even as technology has allowed ever more distributed methods of connectivity. You foreground network identity over individual identity in the 6PM YLT vision, yet the distinction between the individuals that create a network and the corporate hierarchies that make that networking possible are less clear. I am of course gesturing towards the use of Twitter as the principal platform of the project, a question that Ruth Catlow brought up at the launch. Do you still believe that TAZs are possible in our hyper-connected, hyper-corporate world?

Domenico Quaranta: In its first, raw conceptualization, 6PM YLT had to come with its own smartphone app, that had to be used both to participate in the project and to access the gallery. The decision to aggregate content published on different social platforms came from the realization that people already had the production and distribution tools required to participate in the action, and were already familiar with some gestures: take a photo, apply a filter, add an hashtag, etc. Of course, we could invite participants and audiences to use some specific, open source social network of our choice, but we prefer to tell them: just use the fucking platform of your choice. We want to facilitate and expand participation, not to reduce it; and we are not interested in adding another layer to the project. 6PM YLT is not a TAZ, it’s just a social game that wants to raise some awareness about the importance of documentation, the power of networks, the public availability of what we do with our phones. And it’s a parasitic tool that, as anything else happening online, implies an entire set of corporate frameworks in order to exist: social networks, browsers, operative systems, internet providers, server farms etc.

That said, yes, I think TAZs are still possible. The model of TAZ has been designed for an hyper-connected, hyper-corporate world; they are temporary and nomadic; they exist in interstices for a short time. But I agree that believing in them is mostly an act of faith.

Daniel Rourke: The beta-tested, final iteration of 6pm YLT will be launched in the summer of 2015. How will you be rolling out the project in the forthcoming months? How can people get involved?

Domenico Quaranta: 6PM Your Local Time has been conceived as an opportunity, for the organizing subject, to bring to visibility its network of relationships and to improve it. It’s not an exhibition with a topic, but a social network turned visible. To put it simply: our identity is defined not just by what we do, but also by the people we hang out with. After organizing 6PM Your Local Time Europe, the Link Art Center would like to take a step back and to offer the platform to other organizing subjects, to allow them to show off their network as well.

So, what we are doing now is preparing a long list of institutions, galleries and artists we made love with in the past or we’d like to make love with in the future, and inviting them to participate in the project. We won’t launch an open call, but we already made the event public saying that if anyone is interested to participate, they are allowed to submit a proposal. We won’t accept anybody, but we would be happy to get in touch with people we didn’t know.

After finalizing the list of participants, we will work on all the organizational stuff, basically informing them about the basic rules of the game, gathering information about the events, answering questions, etc.

On the other hand, we have of course to work on the presentation. While every participant presents an event of her choice, the organizer of a 6PM Your Local Time event has to present to its local audience the platform event, as an ongoing installation / performance. We are from Brescia, Italy, and that’s where we will make our presentation. We made an agreement with MusicalZOO, a local festival of art and electronic music, in order to co-produce the presentation and have access to their audience. This is what determined the date of the event in the first place. Since the festival takes place outdoor during the summer, we are working with them on designing a temporary office where we can coordinate the event, stay in touch with the participants, discuss with the audience, and a video installation in which the live stream of pics and videos will be displayed. Since we are expecting participants from Portugal to the Russian Federation, the event will start around 5 PM, and will follow the various opening events up to late night.

One potential reference for this kind of presentation may be those (amazing) telecommunication projects that took place in the Eighties: Robert Adrian’s The World in 24 Hours, organized at Ars Electronica in 1982; the Planetary Network set up in 1986 at the Venice Biennale; and even Nam June Paik’s satellite communication project Good Morning Mr Orwell (1984).

Daniel Rourke: Your exhibition Unoriginal Genius, featuring the work of 17 leading net and new media artists, was the last project to be hosted in the Carroll/Fletcher Project Space (closing November 22nd, 2014). Could you tell us more about the role you consider ‘genius’ plays in framing contemporary art practice?

Domenico Quaranta: The idea of genius still plays an important role in Western culture, and not just in the field of art. Whether we are talking about the Macintosh, Infinite Jest, a space trip or Nymphomaniac, we are always celebrating an individual genius, even if we perfectly know that there is a team and a concerted action behind each of these things. Every art world is grounded in the idea that there are gifted people who, provided specific conditions, can produce special things that are potentially relevant for anybody. This is not a problem in itself – what’s problematic are some corollaries to our traditional idea of genius – namely “originality” and “intellectual property”. The first claims that a good work of creation is new and doesn’t depend on previous work by others; the second claims that an original work belongs to the author.

In my opinion, creation never worked this way, and I’m totally unoriginal in saying this: hundreds of people, before and along to me, say that creating consists in taking chunks of available material and assembling them in ways that, in the best situation, allow us to take a small step forward from what came before. But in the meantime, entire legal systems have been built upon such bad beliefs; and what’s happening now is that, while on the one hand the digitalization of the means of production and dissemination allow us to look at this process with unprecedented clarity; on the other hand these regulations have evolved in such a way that they may eventually slow down or stop the regular evolution of culture, which is based on the exchange of ideas.

We – and creators in particular – have to fight against this situation. But Unoriginal Genius shouldn’t be read in such an activist way. It is just a small attempt to show how the process of creation works today, in the shared environment of a networked computer, and to bring this in front of a gallery audience.

Daniel Rourke: So much online material ‘created’ today is free-flowing and impossible to trace back to an original author, yet the tendency to attribute images, ideas or ‘works’ to an individual still persists – as it does in Unoriginal Genius. I wonder whether you consider some of the works in the show as more liberated from authorial constraints than others? That is, what are the works that appear to make themselves; floating and mutating regardless of particular human (artist) intentions?

Domenico Quaranta: Probably Museum of the Internet is the one that fits best to your description. Everybody can contribute anonymously to it by just dropping images on the webpage; the authors’ names are not available on the website, and there’s no link to their homepage. It’s so simple, so necessary and so pure that one may think that it always existed out there in some way or another. And in a way it did, because the history of the internet is full of projects that invite people to do more or less the same.

Daniel Rourke: 2014 was an exciting year for the recognition of digital art cultures, with the appointment of Dragan Espenschied as lead Digital Conservator at Rhizome, the second Paddles On! auction of digital works in London, with names like Hito Steyerl and Ryan Trecartin moving up ArtReview’s power list, and projects like Kenneth Goldsmith’s ‘Printing out the Internet’ highlighting the increasing ubiquity – and therefore arguable fragility – of web-based cultural aggregation. I wondered what you were looking forward to in 2015 – apart from 6PM YLT of course. Where would you like to see the digital/net/new media arts 12 months from now?

Domenico Quaranta: On the moon, of course!

Out of joke: I agree that 2014 has been a good year for the media arts community, as part of a general positive trend along the last few years. Other highlighs may include, in various order: the September 2013 issue of Artforum, on “Art and Media”, and the discussion sparked by Claire Bishop’s essay; Cory Arcangel discovering and restoring lost Andy Warhol’s digital files from floppy disks; Ben Fino-Radin becoming digital conservator at MoMA, New York; JODI winning the Prix Net Art; the Barbican doing a show on the Digital Revolution with Google. Memes like post internet, post digital and the New Aesthetic had negative side effects, but they helped establishing digital culture in the mainstream contemporary art discourse, and bringing to prominence some artists formerly known as net artists. In 2015, the New Museum Triennial will be curated by Lauren Cornell and Ryan Trecartin, and DIS has been announced to be curator of the 9th Berlin Biennial in 2016.

All this looks promising, but one thing that I learned from the past is to be careful with optimistic judgements. The XXI century started with a show called 010101. Art in Technological Times, organized by SFMoMA. The same year, net art entered the Venice Biennale, the Whitney organized Bitstreams and Data Dynamics, the Tate Art and Money Online. Later on, the internet was announced dead, and it took years for the media art community to get some prominence in the art discourse again. The situation now is very different, a lot has been done at all levels (art market, institutions, criticism), and the interest in digital culture and technologies is not (only) the result of the hype and of big money flushed by corporations unto museums. But still, where we really are? The first Paddles On! Auction belongs to history because it helped selling the first website ever on auction; the second one mainly sold digital and analogue paintings. Digital Revolution was welcomed by sentences like: “No one could fault the advances in technology on display, but the art that has emerged out of that technology? Well, on this showing, too much of it seems gimmicky, weak and overly concerned with spectacle rather than meaning, or making a comment on our culture.” (The Telegraph) The upcoming New Museum Triennial will include artists like Ed Atkins, Aleksandra Domanovic, Oliver Laric, K-HOLE, Steve Roggenbuck, but Lauren and Ryan did their best to avoid partisanship. There’s no criticism in this statement, actually I would have done exactly the same, and I’m sure it will be an amazing show that I can’t wait to see. Just, we don’t have to expect too much from this show in terms of “digital art recognition”. So, to put it short: I’m sure digital art and culture is slowly changing the arts, and that this revolution will be dramatic; but it won’t take place in 2015 🙂

AS FOUNDER/DIRECTOR OF THE MEDIA ARCHEOLOGY LAB IN COLORADO, LORI EMERSON HAS (since 2009) been surrounding herself with “dead” media technologies in order to help make sense of (and critique) today’s much-hyped alive ones. Being also a scholar and critic of contemporary poetics, she is keenly aware of how such devices are equipped to influence and constrain our writing/thinking.

Emerson’s work celebrates and calls for a “frictional media archeological analysis” aimed at the continual “unmooring” of the accepted conventions of reading and writing. Towards this end, she critiques consumer-oriented trends in computing–trends which unfortunately seek to “efface the interface” in the name of so-called user-friendliness. Montgomery Cantsin conducted the following interview by email upon the release of Lori’s new book, Reading Writing Interfaces (recently published by University of Minnesota Press).

Montgomery Cantsin: First, I want to point out that your new book is part of a series which was founded by Mark Poster, who passed away not too long ago. Can you talk about how your work fits into his “Electronic Mediations” series and what (if any) influence Poster has had on you?

Lori Emerson: Mark Poster has been an underlying, though subtle, influence on my work as I first read him in a graduate seminar I took on “cybercultures” in the mid- to late-90s with the Victorianist and early hypertext theorist Christopher Keep. That class and Poster’s work–his deeply political readings of digital media structures–stayed with me long afterwards. In fact, about seventeen years ago I gave a presentation on “Postmodern Virtualities” in that class and while I have no memory at all of what I said or even what I learned from reading his work back then, it’s remarkable that his opening sentence rings so true to the kind of work I now find myself doing–he writes that “a critical understanding of the new communications systems requires an evaluation of the type of subject it encourages, while a viable articulation of postmodernity must include an elaboration of its relation to new technologies of communication.” And so the point at which I realized I was, to my surprise, writing a political book that meshed together poetics and media studies was the point at which I realized that my work would likely fit in best (or, given its reputation in media studies, I wanted to make my work fit in) with the Electronic Mediations series, especially because of their books on tactical media, glitch and error, as well as the politics of archives and networks. It’s such a thrill and an honor to have my book included in that series.

MC: How did your Media Archeology Lab come about?

LE: I was fortunate enough to have the support of the past director of the Alliance for Technology, Learning, and Society when I was first hired here at the University of Colorado at Boulder in 2008. In 2009, the director, John Bennett, offered me a $20,000 startup grant to build a lab, any lab, that Atlas and English Department students could both use. I then began looking for a way to build a lab that wasn’t just another venue on campus to celebrate the perpetual new in computing and, since I was at the time fascinated with how the Canadian poet bpNichol wrote one of the first kinetic digital poems, “First Screening,” in 1983 using Basic on an Apple IIe, I decided to create a lab that had enough Apple IIe’s to teach bpNichol in a classroom full of 20 English majors. It didn’t take long before I moved on to acquiring Commodore 64’s and then to where we find ourselves now, with a collection of about a thousand pieces of still functioning hardware and software from the mid-1970s to the early 2000s. I also have to admit that the MAL wouldn’t be what it is now if we weren’t flying under the radar of the university for the first three years or so. The relative obscurity of the lab in those early years meant that we had little to no oversight, no one to report to, no metrics or outcomes to adhere to, and so on which meant we were free to be as wild as we wanted.