‘Seeds From Elsewhere’ (2016 – ongoing) is a project by They Are Here that has begun to re-animate a dilapidated play area in Finsbury Park, bringing together young asylum seekers and refugees, family, friends and other professionals. Each participant is supported to grow flowers, plants or edible produce from their respective homeland. We are also in the process of designing a greenhouse and pizza clay oven, extending the parameters of our collective activity. Throughout the process we literally and metaphorically ask ‘What can grow here that’s not from here?’ Beyond this more tangible gardening activity, the project seeks to create a space that embraces, maintains and produces a diverse set of social relationships between people with different residency status. It is supported by Furthefield an organisation exploring the intersection of networked culture and contemporary art.

It was July 2016, less than a month after the results of the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, when our project commenced. Although the impetus to begin was not a conscious response to the referendum outcome – the timing is not insignificant. Our initial steps were in a toxic political atmosphere at the height of an intensified and indiscriminate rhetoric against migrants.

Artists were faced with new variations of old questions that resurface in turbulent times. . . What is our role in protest? Do we have a particular responsibility as artworkers to engage with a given political landscape? What are the capabilities and limitations of art in local / national / international governmental politics? Such questions often reveal an expectation of certain aesthetics, rather than attitudes. It is in the multiple ways that a work is circulated and produced its politics should be sought. . . How is the work funded? How is it credited? Which voices are included in its development, or excluded? How is the work talked and written about by the various partners supporting its production?

In these seemingly small details, a larger political statement is embodied rather than solely visually evoked. At the same time, we reject a ‘one-or-the-other’ stance. Establishing and administering a small community garden should not negate working with others on larger-scale efforts at the scale of local government or beyond. Bridges should be made between all scales of activity. The same fluid hierarchies and embrace of hybridity we cultivate with Seeds From Elsewhere, we encourage at ever larger scales – generating continuities between the ethos of how we are working on the garden and how national and global resources are considered and decisions made.

‘Participation is not always progressive or empowering’, ‘Realise your own privilege’, ‘Critically interrogate your intention’, ‘Process not product’, ‘Presentation vs representation – Know the difference!’, ‘Do not expect us to be grateful’, ‘Art is not neutral’, ‘It is not a safe-space just because you say it is,’ ‘Do your research’, ‘ Do not reduce us to an issue’. These notes are from Rise (Refugees, Survivors and Ex-detainees – the first refugee and asylum seeker organisation in Australia to be run and governed by refugees, asylum seekers and ex-detainees) . . . 10 Things You Need to Consider If You are an artist not of the Refugee and Asylum Seeker Community Looking to work with our Community authored by Tania Canas, RISE Arts Director.

In a polarised mediascape, where tabloid headlines shout loudest, the reduction of a diverse group of people to an ‘issue’, has been one of the most problematic aspects of public debate. Recognising that Seeds From Elsewhere is a slowly gestating project affords time for us to slowly get to know the participants individually – who to date hail from Albania, Sudan, Congo, Ethiopia, Romania, Afghanistan & Nepal. Rather than seek to ‘represent them’, we are co-workers on a set of shared goals.

Importantly, this work functions as a hybrid activity, with multiple points of access and identification. For the young refugees the garden can offer a respite from various kinds of bureaucratic limbo, it can also simply be a place to chill in a tolerant environment. In the longer term, there maybe be the potential for employment opportunities in the garden. At the same time, the work functions within the tradition of many conceptually driven socially-engaged artworks, notably Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982) by Agnes Denes, Edible Estates (2005 – ongoing) by Fritz Haeg and Parkwerk (2014) by Jeanne van Heeswijk.

The project has also become a gateway to consider the language of rhetoric against migrants, as well as that of sympathetic media too, focusing on the recurrence of botanical language as metaphor (soil, roots etc). Essays by US-based anthropologists Dr. Lisa Malkki and Dr. Stefan Helmreich have been particularly insightful. The latter quotes biologist Banu Subramniam, noting that these criteria ‘resonate unfortunately with xenophobic anti-immigration language in the United States and Europe’:

“The parallels in the rhetoric surrounding foreign plants and those of foreign peoples are striking … The first parallel is that aliens are ‘other’ … Second is the idea that aliens / exotic plants are everywhere, taking over everything … The third parallel is the suggestion that they are growing in strength and number … The fourth parallel is that aliens are difficult to destroy and will persist because they can withstand extreme situations … The fifth parallel is that aliens are ‘aggressive predators and pests and are prolific in nature, reproducing rapidly’ … Finally, like human immigrants, the greatest focus is on their economic costs because it is believed that they consume resources and return nothing.” [1]

Becoming attuned to language is a vital part of a larger and never-ending exercise in developing cultural and individual self-awareness as to how we speak, itself inseparable from how we think.

Our fortnightly group meetings in the garden are rich in debate and banter. Working on a garden is an unceasing process. Like the growth of plants themselves, it cannot be rushed without compromise. This notion of maintenance is akin to a healthy democracy. Rather than an invitation to vote every four years, democracy must be attended to daily; it is comprised of multiple systems collectively supporting each other. Beyond physical access to a voting booth, there is the need for both protection and scrutiny of the media, investment into an education system that encourages voters to make informed choices, the space for satirists, philosophers and artists to critique power and the continual checking of our own presumptions and privileges.

Harun Morrison + Helen Walker

They Are Here

February 2017

contact@theyarehere.net

At first glance networks and the practice of drawing would seem to be worlds apart. However, the diagram, originally a hand-drawn symbolic form, has long been employed by science as a means of visualising and explaining concepts. Perhaps the most important of these concepts is that of relationships visualised as circles and lines that represent nodes and links or effectively what is related. As such networks, that is groupings of relationships, have come to be visualised through the use of the same styles and iconography employed in diagrams. For artists to reclaim the diagram as a part of their own practice and thereby adopt the practice of visualising networks developed within science sees the practice of creating diagrams in a sense come full circle. Artists have time and time again drawn diagrams and networks that explore relationships. For example: Josef Beuys famously used blackboard diagrams as part of his teaching performances concerning art and politics; Stephen Willats has since the 1960s developed drawn diagrammatic works that explore his socially formed practice; Mark Lombardi drew societies’ networks of power relations throughout the 1990s; Torgeir Husevaag has since the late 1990s drawn diagrams of a number of networks within which he participated while Emma McNally draws diagrammatic networks “bringing different spaces into relation [such as] the virtual world, the networked world and the supposedly real world” (Hayward, 2014).

The work of Suzanne Treister resides within this category of artist’s drawing, and in this instance also painting, networks. With a background in painting Treister works across video, the internet, interactive technologies, photography, drawing and watercolour painting (Treister, n.d.). Her work employs “eccentric narratives and unconventional bodies of research to reveal structures that bind power, identity and knowledge” (ibid) within contemporary contexts. As a result of this process of revealing structures, essentially the relationships within the subject matter she addresses and the resulting networks they form, her practice has since the 1990s been closely allied with art that employs or explores technology. She has been repeatedly included in exhibitions and publications that link her work with networks, cybernetics, new media and most recently Post-Internet Art (Flanagan and Booth, 2002; Pickering, 2012; Larsen, 2014; Warde-Aldam, 2014).

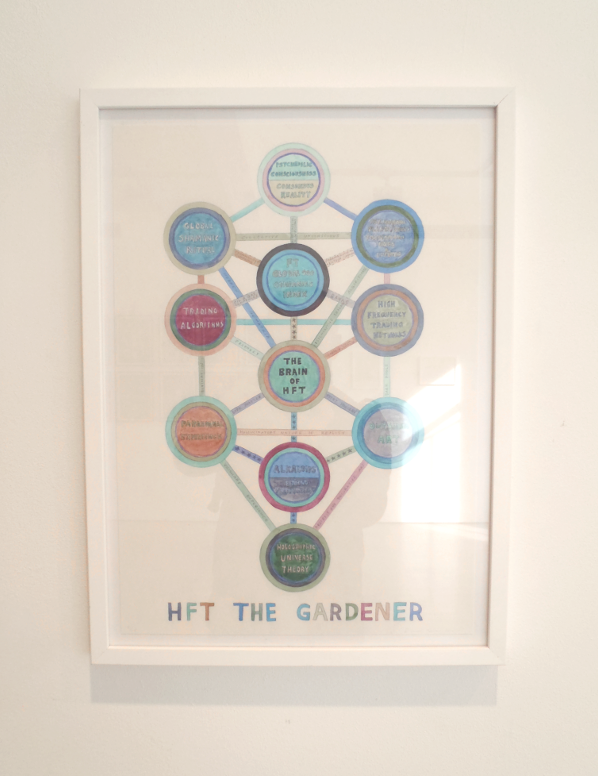

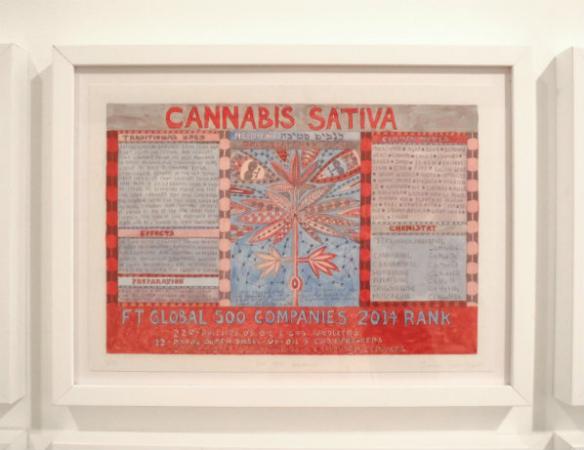

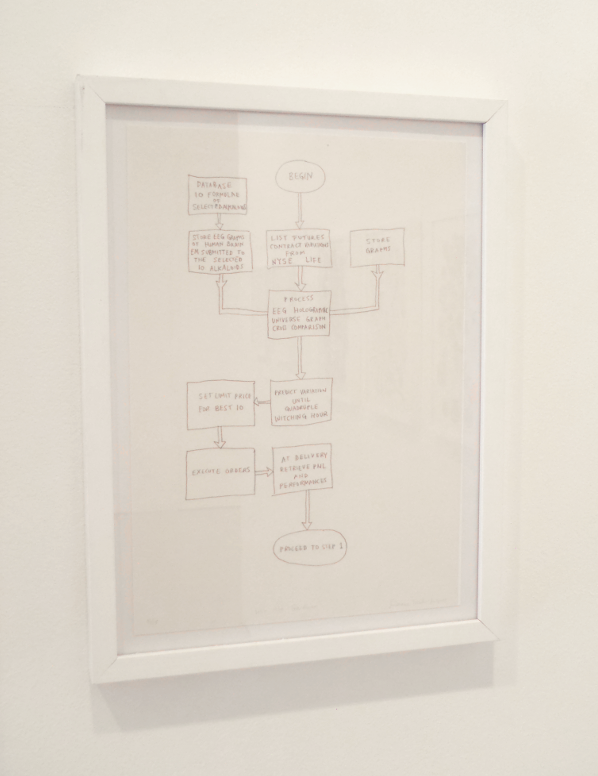

HFT the Gardener (2014-15), a recent solo exhibition by Treister at Annely Juda Fine Art in London, is a body of artworks consisting of drawings, paintings, photographs and digital prints supposedly created by a fictional character and a documentary video about the same character. The character, Hillel Fischer Traumberg, is an algorithmic high-frequency trader (HFT) within the London Stock Exchange. After an optically induced semi-hallucinogenic state, Traumberg experiments with psychoactive drugs in order to recreate and further the experience (Treister, 2015). Along the way Traumberg becomes fascinated with botany, experiments with the molecular formulae of drugs as trading algorithms, makes links between the numerological equivalents of plants’ botanical names and the FT Global 500 index, visually documenting all of his research and ultimately becoming an ‘outsider’ artist (ibid). In the process Traumberg transitions from an insider of one network, a trader within the stock exchange, to that of an outsider in another, the contemporary art world.

This juxtaposition of opposites is repeated throughout the exhibition. For example, the drawings and paintings of HFT the Gardener employ illustrations of networks containing nodes and links. These illustrate a number of different sets of relationships that are established by the artist. These include: that of the central character to his concepts, research and environment; the locations where drugs were taken; states of consciousness; the components of an algorithm; different companies within a sector and different aspects of the universe including life and art. Additionally a variety of diagrammatic forms are co-opted in the creation of the drawings and paintings including the Judaic Kabbalah Tree of Life, radial diagrams, flowcharts similar to those used in software design and reference is made to a number of other abstracted forms including star charts, snow crystals, fractals and paisley design. Through both form and subject matter the illustrations of networks and the diagrams gather together combinations of opposites. There is of course the use of what can be considered traditional media to illustrate new media forms, however among others there are also the opposites of painting and software, science and art, corporate and counter-culture, belief and fact, fiction and reality.

To coincide with the creation of the artwork a book of the same name has been published. In the foreword Erik Davis states that there is an “initial shock of Treister’s juxtaposition of esoterica and the financial sector” (2016). The same could be said of the numerous other juxtapositions that occur within HFT the Gardener. However, are Treister’s, or is it Traumberg’s, combinations really contrasts that shock? Treister does more than simply juxtapose opposites. The artist effectively synthesises them into a whole that is indicative of our networked era where individuals routinely select, cut, paste and combine combinations ad-hoc to suit a moment or context. HFT the Gardener is an artwork that could only be created in this era of networks and as such it cannot be considered shocking or out of context with the eclectic recombinatory society that surrounds it.

Not only are drawn diagrams and networks employed extensively throughout the exhibition in a number of ways but a network-like structure is also employed to arrange the artworks within the space of the gallery. Initially on entering the gallery space it seems as if artworks are arranged in no particular order. However it gradually becomes clear that this arrangement is purposefully obliging the visitor to enter into and move through the space as if it were a network; that is entering at any point and navigated in any order. While some series of artworks within HFT the Gardener, such as the Botanical prints, maintain an order to illustrate the ranking of companies employed in their creation, the majority of artworks are experienced out of the order they have been created and the documentary video about Traumberg, presumably from Treister’s perspective, is encountered at the midpoint of the exhibition. As such the artworks are presented as if they are interconnected nodes in a network.

As a result of the diagrams, illustrations of networks, juxtaposed combinations of subject matter and a network-like structure in arranging the artworks within the exhibition Treister successfully manages to make one last combination of opposites, that of non-linearity of experience and linearity of narrative. In doing so the visitor experiences the juxtapositions, combinations and resulting networks formed by Traumberg’s hallucinatory non-linear associations and yet manages to steadily interpret the detailed narrative carefully constructed by the artist. It is in this last combination where the strength of Treister’s exhibition lies as it not only reflects society at large but also suggests that art is and perhaps always has been, a non-linear networked experience that is only now coming into its own.

An exhibition catalogue of HFT The Gardener is available through ISSUU (https://issuu.com/annelyjuda/docs/treister_cat) and a fully illustrated book of the same name is available from Black Dog Publishing, London.

HFT The Gardener will continue to tour throughout 2017 at the following venues. Please see the artist’s website for exhibition updates.

22/10/2016 – 05/03/2017

Selected works from HFT The Gardener exhibited in The World Without Us

Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV),

Dortmund, Germany.

07/01/2017 – 18/02/2017

HFT The Gardener diagrams exhibited in Underlying system is not known

Western Exhibitions, Chicago, USA.

03/02/2017 – 05/03/2017

Selected works from HFT The Gardener exhibited in Alien Ecologies

Transmediale 2017

Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany.