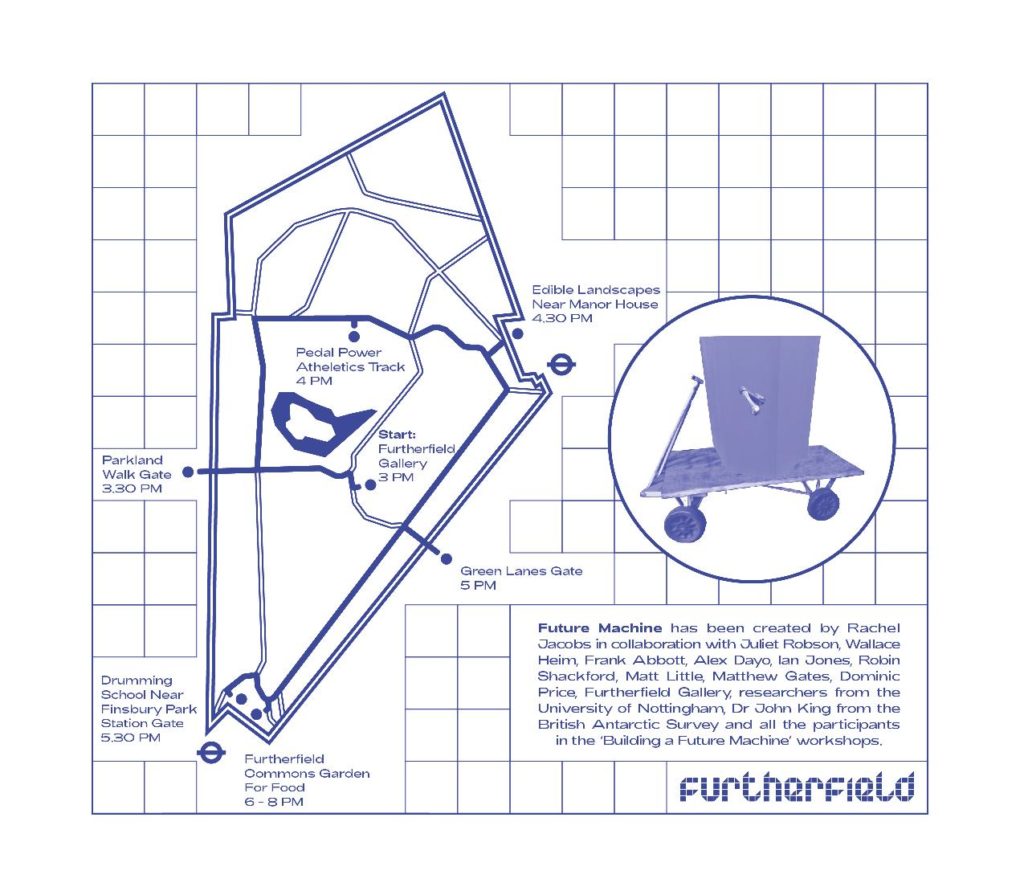

The Future Machine, part of Furtherfield’s Citizen Sci-Fi programme, has been built with local groups as a witness to people and places, changing over time. It gathers evidence and stories of these turbulent times, as the Earth changes, and we journey to an uncertain future.

You are invited to join the Future Machine on it’s first procession around Finsbury Park on Sat 12 Oct. We begin at Furtherfield Gallery at 3.00pm. Then the Future Machine will be welcomed at various stops on the way by local groups who promise to care for the future, it ends its journey at 6pm with a party to welcome the Autumn in at Furtherfield Commons Garden.

Please join the procession at Furtherfield Gallery at 3pm, or at any of the stops and dress up in your best or wildest Autumn clothes.

Future Machine Procession Stops:

Future Machine has been created by Rachel Jacobs in collaboration with Juliet Robson, Wallace Heim, Frank Abbott, Alex Dayo, Ian Jones, Robin Shackford, Matt Little, Matthew Gates, Dominic Price, Furtherfield Gallery, researchers from the University of Nottingham, Dr John King from the British Antarctic Survey and all the participants in the ‘Building a Future Machine’ workshops.

After touring to other places across England, the Future Machine will return to Finsbury Park in October in 2020 and 2021, as the future comes.

Featured image: credit to Rachel Jacobs

Future Fictions for Finsbury Park is part of our Citizen Sci-Fi initiative. It brings together sci-fi writers in residence with local residents and set of scientific experts to explore written visions of a Finsbury Park of the future.

For our 2019/2020 year of FF4FP we worked with sci-fi writers Mud Howard and Stephen Oram to create two new short stories about the park, based on deep research conducted with community members and experts. Via a set of workshops organised by Producer, Ruth Fenton, participants were invited to explore both near and far future ideas based on the current knowledge we have of climate change and technological developments, to imagine how we might like to see Finsbury Park evolve.

At our Future Fair on 10th August 2019, both Mud and Stephen gave live readings of their stories, which will be published on the Furtherfield website this Autumn.

Mud Howard (they/them)

A gender non-conforming poet, performer and activist from the states. mud creates work that explores the intimacy and isolation between queer and trans bodies. mud is a Pushcart Prize nominee. they are currently working on their first full-length novel: a queer and trans memoir full of lies and magic. they were the first annual youth writing fellow for Transfaith in the summer of 2017. their poem “clearing” was selected by Eduardo C. Corral for Sundress Publication’s the Best of the Net 2017. mud is a graduate of the low-res MFA Poetry Program at the IPRC in Portland, OR and holds a Masters in Creative Writing from the University of Westminster. you can find their work in THEM, The Lifted Brow, Foglifter, and Cleaver Magazine. they spend a lot of time scheming both how to survive and not perpetuate toxic masculinity. they love to lip sync, show up to the dance party early and paint their mustache turquoise and gold.

Stephen Oram

Who writes thought provoking stories that mix science fiction with social comment, mainly in a recognisable near-future. He is one of the writers for SciFutures and, as 2016 Author in Residence at Virtual Futures – described by the Guardian as “the Glastonbury of cyberculture” – he was one of the masterminds behind the new Near-Future Fiction series and continues to be a lead curator. Oram is a member of the Clockhouse London Writers and a member of the Alliance of Independent Authors. He has two published novels: Fluence and Quantum Confessions, and a collection of sci-fi shorts, Eating Robots and Other Stories. As the Author in Residence for Virtual Futures Salons he wrote stories on the new and exciting worlds of neurostimulation, bionic prosthetics and bio-art. These Salons bring together artists, philosophers, cultural theorists, technologists and fiction writers to consider the future of humanity and technology. Recently, his focus has been on collaborating with experts to understand the work that’s going on in neuroscience, artificial intelligence and deep machine learning. From this Oram writes short pieces of near-future science fiction as thought experiments and use them as a starting point for discussion between himself, scientists and the public. Oram is always interested in creating and contributing to debate about potential futures.

The Future Experts comprised of local residents of Finsbury Park, who brought invaluable knowledge of the area, and professional experts from a variety of scientific and design based backgrounds, who brought expertise in future thinking in many areas including health, transport, technology and architecture.

Ling Tan

Ling Tan is a designer, maker and coder interested in how people interact with the built environment and wearable technology. Trained as an architect, she enjoys building physical machines and prototypes ranging from urban scale to wearable scale to explore different modes of interaction between people and their surrounding spaces. Her work falls somewhere within the genre of the built environment, wearable technology, Internet of Things(IoT) and citizen participation. It involves working with various communities in different cities and uses wearable technology as tools to express their relationship with the city, touching on demographic, race, gender and the subjective experience of the city through people.

Paul Dobraszczyk

I am a researcher and writer based in Manchester, UK, and a teaching fellow at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. I’m currently researching anarchism and architecture as well as completing a co-edited book Manchester: Something Rich and Strange (Manchester University Press, forthcoming in 2020). I’m the author of Future Cities: Architecture and the imagination (Reaktion, 2019); The Dead City: Urban Ruins and the Spectacle of Decay (IB Tauris, 2017); London’s Sewers (Shire, 2014); Iron, Ornament and Architecture in Victorian Britain (Ashgate, 2014); and Into the Belly of the Beast: Exploring London’s Victorian Sewers (Spire, 2009). I also co-edited Global Undergrounds: Exploring Cities Within (Reaktion, 2016); and Function & Fantasy: Iron Architecture in Long Nineteenth Century (Routledge, 2016). I am also a visual artist and photographer and built the website http://www.stonesofmanchester.com. I blog at https://ragpickinghistory.co.uk/.

Dr Rasmus Birk

I am a social scientist, currently working as a Visiting Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Global Health & Social Medicine, King’s College London. My research here explores the relationship between city life and mental health, specifically how living in the city leads, for some people, to the development of mental health problems. I am currently researching the experiences of young people with common mental health problems (such as depression, anxiety, or stress) in South East London.

Dr Kate Pangbourne

University Academic Fellow at the Institute for Transport Studies (University of Leeds). She has an MA (Hons) in Philosophy with English Literature, an MSc in Sustainable Rural Development and a PhD in Geography – Environmental (Transport Governance). Her research is oriented towards shifting our transport system and individual choices towards greater environmental sustainability, social inclusion and meaningful prosperity. She is particularly interested in the implications of rapid technological change in the transport sector. Current work includes improving the persuasiveness of travel behaviour messages (ADAPT, funded by EPSRC), enhancing the rail passenger experience (SMaRTE, funded by the EU through Shift2Rail) and the societal challenges posed by self-driving vehicles and new concepts such as Mobility as a Service. Proof of humanity: has children, grows vegetables, sews and knits, sings, plays the piano, and used to play jazz sax (badly). Weird info: is a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Cordwainers and of the City of London (but lives in Scotland).

https://environment.leeds.ac.uk/transport/staff/971/dr-kate-pangbourne

Dr Christine Aicardi

Originally trained in applied mathematics, computer sciences and project management, with a MEng from the Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées in France. She worked for many years in the Information and Communication Technologies industry, where she held a variety of positions (analyst/programmer, junior consultant, sales engineer, major account manager). She returned to higher education and came to Science and Technology Studies in 2003 as a mature student. After her MSc at the London Centre for the History of Science, Medicine and Technology, she was funded by the ESRC through her doctoral studies, and in 2010, she completed her PhD in Science and Technology Studies at UCL, in the area of Artificial Life. She is currently a Senior Research Fellow for the Human Brain Project Foresight Laboratory. The Lab aims to evaluate the potential social and ethical implications of the knowledge and technologies produced by the Human Brain Project for European citizens, society, industry, and economy. Prior to this, she was Wellcome Library Research Fellow, working on a sociological history project focused on the later career of Francis Crick, British molecular biologist and geneticist, who in the 1970s moved to Southern California and became a neuroscientist.

Featured image: Rusty Russ Twisted Tree ReTwisted via photopin (license)

Artist Rachel Jacobs is working in partnership with Furtherfield to build a Future Machine in Finsbury Park and you are invited to help build it.

Location:

Furtherfield Commons

269-271 Seven Sisters Road

Finsbury Park

N4 2DE

Sign up to take part in four workshops that will involve thinking about the future (in response to environmental change) and helping to design and build the Future Machine, towards an unveiling at Furtherfield Gallery this Autumn and tour of England in 2019/2020.

The workshops are designed to bring together people with ALL views on environmental change – denier, worrier, eco-warrior, confused, conspiracy theorist, lover of trees – everyone is welcome! The workshops will involve talking, thinking, making things with all kinds of arts and craft materials, as well as using interactive technology and scientific sensors. You are welcome to sign up to one or all of the workshops, you don’t need to attend them all to take part.

Furtherfield Commons is a wheelchair accessible venue. Please email the artist at: promises@thepredictionmachine.org if you want to discuss any accessibility requirements.

Workshop times/dates:

Book now!

Refreshments will be provided

The Future Machine sits on a hand cart ready for the journey, travels the country and plugs into a greater whole of many parts. It stands as a witness to the places, people, stories and events of these turbulent times, as the Earth changes, and we take a journey into an uncertain future.

The Future Machine is a new artwork, a large interactive machine, built to help us to respond to environmental change as the future unfolds. The machine will record people’s visions of the future, make predictions, facilitate new rituals and helps us to make decisions about the future we want, not one we fear.

The artwork will be created in collaboration with a team of engineers, programmers, climate scientists from the British Antarctic Survey, researchers from the University of Nottingham, and participants in a series of artist-led workshops, scheduled to take place in London and Nottingham in 2019.

The Future Machine will be built by YOU over the coming months and unveiled in an Autumn ritual – details to follow

The Future Machine is part of Furtherfield’s 2019 programme: Time Portals.

The word speculation is defined as ‘the forming of a theory or conjecture without firm evidence’. The act of speculating was predominantly popularised with the rise of the stock market, however, recent environmental destruction and technological advancements have prompted a rich pool of speculation about the future of our planet, our species and our connection to other facets of life. Tomorrows: Urban Fictions for Possible Futures is such an exhibition, compromised of imaginative narratives speculating the future of our cities – how they will look, how they will function and the degree by which these cities will form new types of citizens directly operating within the network of that future city. In the context of the exhibition’s content, fiction is transformed into mighty medium, utilised to share the ideas of thirty-two individual and group projects. These projects envision and share their anticipation for the future as a means of addressing socio-economic, environmental and other issues we face today with a goal to reassess of our presence on the planet.

Tomorrows was curated by Daphne Dragona and Panos Dragonas, and organised by the Onassis Cultural Centre in Athens – a city experiencing continual fluctuations since the end of World War II. The location itself, Diplarios School (a place of former learning and listening), stresses the aspect of sharing and the telling of important narratives determining the shaping of the future. The exhibition begins with a didactic, yet absolutely accessible approach to understanding the notion of developing a future city. As a starting point, the exhibition borrows and advances the ideas of Doxiadis’ speculative plans of an Ecumenopolis from 1959-1974. More particularly, we must take into consideration the term ‘ekistics’ which was coined by Doxiadis in 1942 as derived from the ancient Greek noun οίκιστής, meaning a person who installs settlers in a place or creates a settlement.

In order to create the cities of the future, we need to systematically develop a science of human settlements. This science, termed Ekistics, will take into consideration the principles man takes into account when building his settlements, as well as the evolution of human settlements through history in terms of size and quality. – Doxiadis

Doxiadis was a visionary and the decision to reinstate his work within the framework of the exhibition was incredibly rewarding for visiting audiences. He anticipated that cities were to become more than global in order to accommodate an ever changing human and non-human environment – as one huge network perhaps out of the control of human capacities. Ecumenopolis is installed on large hanging panels in the first room of Tomorrows and acts as a reference point to the five themes developed: Post-Natural Environments, Shells & Co-Habitats, Networks & Infrastructures, Algorithmic Society and Beyond Anthropos. These themes resonate to the acceleration of our urban development hybridising the natural with the artificial, future network infrastructures of our habitats becoming dependent on inhuman mediation, the possibility of an omnipresent and undemocratic structure within the city through the interdependence of economy, ecology and technology, possible forms of organisation to encourage modes of co-existence within the city, and technological singularity as challenging human sovereignty within our future cities. Doxiadis work gives way to the participants who are primarily artists, architects and designers, to explore these imminent futures of our present planet’s landscape.

Coastal Domains is an on-going research project exploring the future landscaping of coastal territories in the Northeastern Mediterranea facilitated by Demetra Katsota along with 4th and 5th year students at the Department of Architecture, University of Patras. The installation Coastal Domains was made up of sixteen books, acting as case studies, secured on the wall and a ladder to reach them, encouraging brave visitors to climb and read them – a curatorial decision simultaneously inspiring participation and learning as it is explicitly reminiscent of old archival libraries. The 7th book in the series of sixteen engaged with the coast land of Kanoni and its Sea Lane on the island of Corfu, the research undertaken by Stella Andronikou and Iasonas Giannopoulos. As with each book in the series, the research was made up historically archived material, such as cartographical maps from different centuries and topographical material including the arrangement of roads and different fauna on the island thus unveiling issues of coastal development, the implications of an upsurge of tourism in the 1970s and possible environmental issues. Coastal Domains speculates and designs possible structures for the reinforcement of sustainability, devising various strategies that can protect the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea.

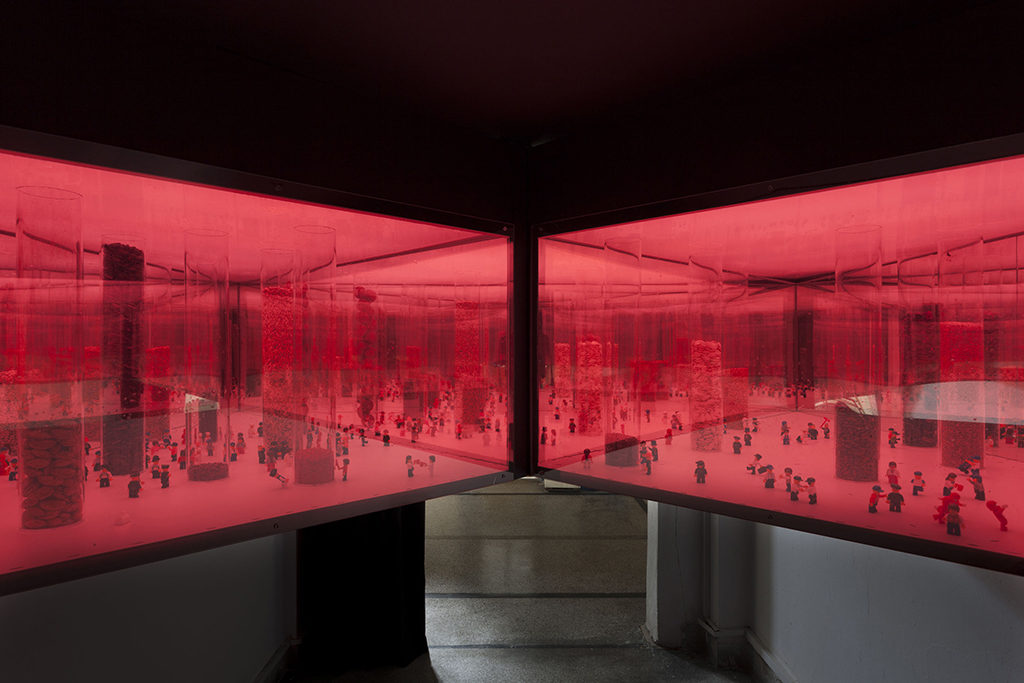

Tomorrows is particularly involved in engaging its locality of the Mediterranean, treating it as a microcosm for observing the implications of the future’s development. Silo(e)scapes by Zenovia Toloudi envisages a hybrid of a seed bank and museum for Mediterranea plant species as a tool inspiring a sharing economy. The installation of Silo(e)scapes required the audience to cradle themselves into the centre of the structure in order to experience the transparent silos-displays of the community LEGO labourers sharing their local seeds at the seedbanks. The audience suddenly find themselves in a possible future reality, all encompassing of agrarian sounds and 360 views of kaleidoscopic mirrors that trick perception of your depth of field. Almost theatrical, Silo(e)scapes is immersive and constructs a space where the audience is directly in conflict with the imminent shortage of supplies due to harmful environmental issues and increasing urban development. The audience becomes entirely physically encased in Silo(e)scapes, as a result inciting the plausibility of this future reality.

A Cave for an Unknown Traveler by Aristide Antonas introduces another form of habitable landscape for the possible future. The installation is structured like a ‘fake archaic cave’ that is buries inside it a structure as luxurious as a modern hotel room, invisible to the eye from the outside. The installed structure of the cave is complimented by a large sketchbook denoting the various features of the Cave for an Unknown Traveler. Antonas’ work brings to mind the concept of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. The infrastructure and services within Antonas’ cave can be taken in context of the prisoner’s in Plato’s cave perceiving shadows as objects when in fact they are a mere representation of their physical form grasped by our mind. In this context, Antonas’ invisible cave begins to resemble an imagined safe haven for a traveling passer-by.

The highlight of Tomorrows is undoubtedly Liam Young’s commissioned work Tomorrow’s Storeys – a two-channel video installation isolated in a dark room with modular seating. The title of the work acts with a double meaning as in storeys of a building and the stories being told through them. The content, or stories, narrated in Tomorrow’s Storeys were first conceived in a workshop in mid-March as part of the programming to the run-up of the exhibition opening in mid-May. The workshop of visual artists, authors, photographers, directors and architects produced an abundance of local stories in the future city of Athens, particularly a future Athenian apartment block. In Tomorrows Storeys all apartments blocks have the ability to reorganise themselves automatically – modular entities like seating in the installation. The videos convey intricately detailed shots of the façade of these apartments as well as its contents recalling film shot by aerial drones and ads for IKEA products. The audience act as omnipresent eavesdroppers drifting from storey to storey into the conversations and local happenings in these apartment blocks. These apartment blocks of the future have found a way to reorganise themselves where Athenians are not given a minimum basic income but instead a minimum basic floor area – the occupants do not own an apartment but a specific volume of space which does not have a fixed location. Amongst these stories of shifting permanence and impermanence one stood out: that of an old grandmother dying and the family arguing about who takes over her volume of space as one character cries quite humorously “Can’t you wait until the funeral?!”. Tomorrows Storeys are part of a city where bots constantly reorganise your living in a form of urban computation according to best fit the needs of its citizens. In this way, a living space becomes a temporality, alluding the audience to question if their home is real if it always available for smooth transition to another space.

Within urban infrastructures are the human entities contained within them, as Young’s work emphasises, however some of these are becoming increasingly inhuman as the theme of ‘Beyond Anthropos’ suggests. The notion of inhuman or machinic entities being able to replicate human form and intelligence is common and highly popularised since the 1980s as films such as Bladerunner introduced global audiences to ‘replicas’. Today, AI is becoming so intelligent that it urges inventors such as SpaceX and Tesla CEO/founder Elon Musk to warn for correct precautions to be taken when engaging with AI, in fact comparing it to ‘summoning the demon’ and naming it ‘our biggest existential threat’ in the 2014 AeroAstro 1914-2014 Centennial Symposium by MIT. The work of !Mediengruppe Bitnik, coming only a couple of years after Musk’s interview, exemplify the relationship between human and machine. Ashley Madison Angels at Work in Athens is a research project initiated after the data of the Canadian online dating service was leaked in 2015. The leak revealed that Ashley Madison had created 75,000 female chatbots that catered to 32 million mostly male users, engaging them in costly internet intimacy. In Athens, there were 165 fembots for around 22,910 registered users. The installation was comprised of seven of these 165 fembots active in Athens, and were installed in a room dimmed by a fluorescent pink light with screens on tripods similar to average human height and alluding to a physical form. The fembots, programmed to be of different ages, utter pick-up lines they are allocated from a predetermined list to the 22,910 registered users who could not distinguish that they were talking to a machine and not a real person.

Tomorrows does not wish to present us a future as a prediction or as a form of critique of these technological, environmental and urban developments. Rather, it presents the future as an on-going participatory project, as a tool that can be utilised to examine who we are and where we are at in present tense, as well as where we could be potentially going. These urban fictions of our possible futures, are a speculative activity with the capability of making us more aware of the changes that have taken place whilst simultaneously illustrating the changes that are afoot. Tomorrows was a show that took place over six months ago, but its value to the discourse of the future will remain timeless for decades to come.

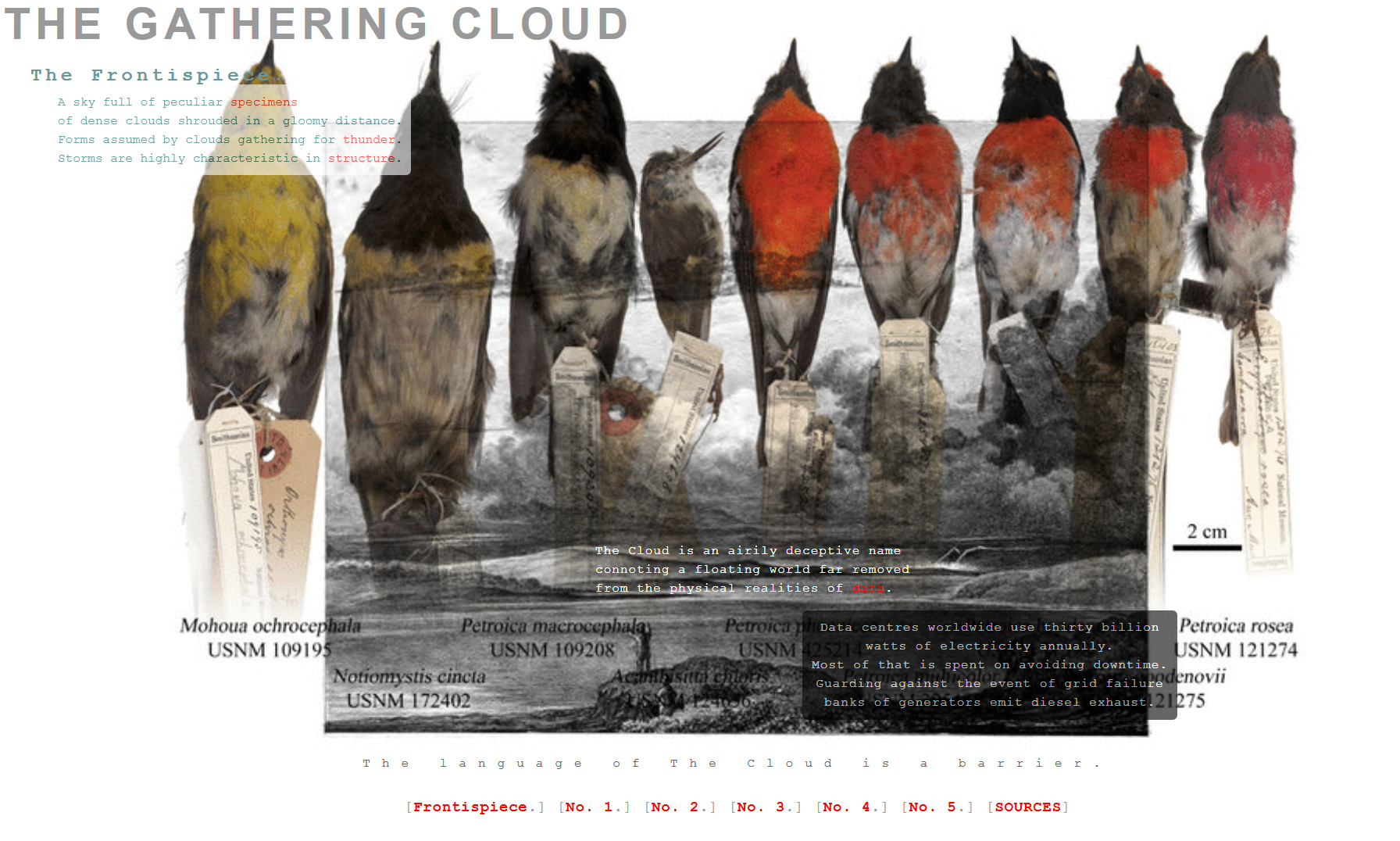

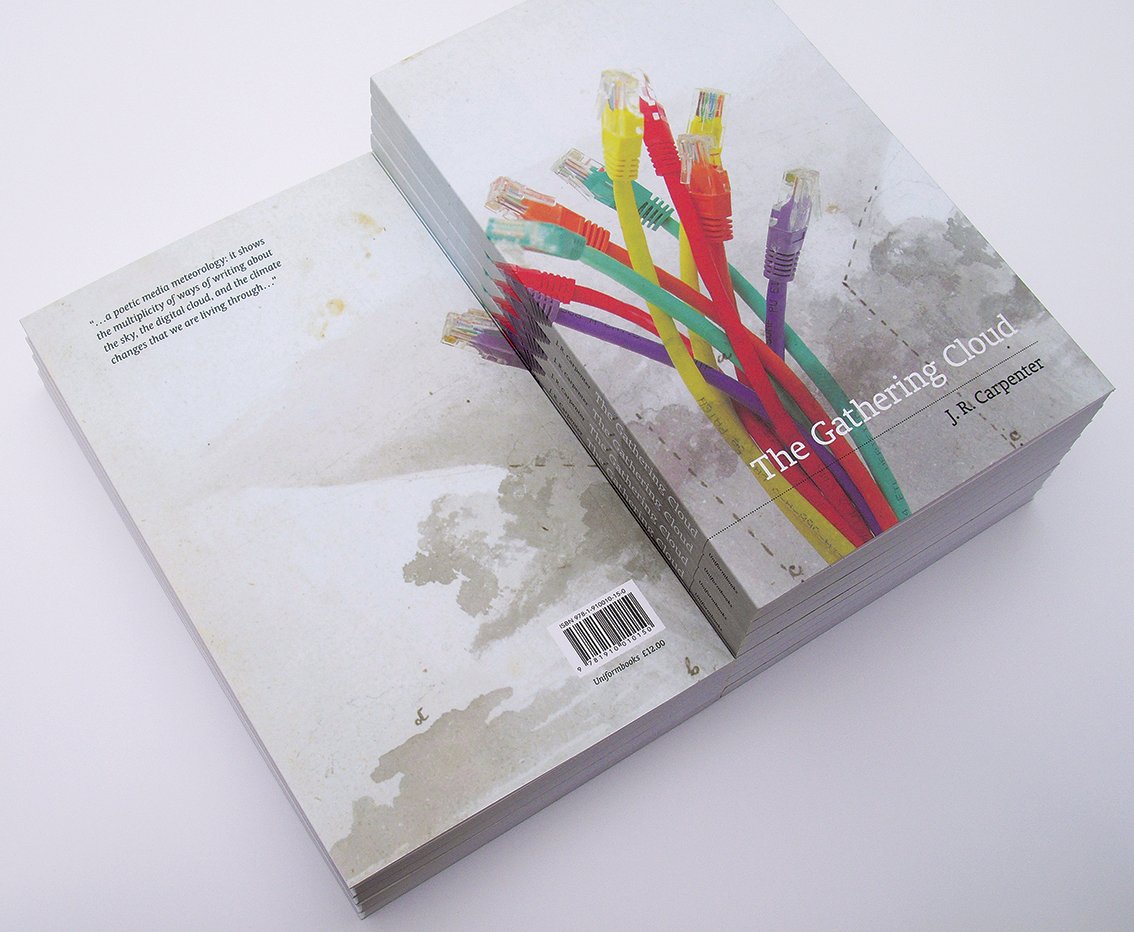

The Gathering Cloud makes slow reading. Let’s start with the title. It trips off the tongue, doesn’t it? Rolls around in the mind like a marble you’ve had since childhood. But there’s something unfamiliar about it, too. ‘The gathering cloud’ evokes a threat – the gathering crowd, perhaps; words haunted by expectation; a riot just about to begin. The gathering cloud sounds material and immaterial at the same time. It could signal rain, or warmth, or happiness for shepherds and fishermen, if only you knew how to read it. Could the ancients interpret celestial data? Can Google analysts do it now?

Every sentence in JR Carpenter’s literary artwork, The Gathering Cloud, is as resonant and expansive as its title. The work is so full of meaning, in fact, that it pushes beyond its own borders. Both a piece of digital literature commissioned by Neon Digital Arts Festival, and a book published by Uniform Press, The Gathering Cloud hovers, as an aesthetic experience, in between (it also exists as a printed A3 zine, distributed in more informal ways).

Its theme is climate change. Or, more precisely, the material effects of technologies euphemistically named ‘cloud computing’ on the health of the planet. Or the systems of knowledge that reveal and obscure our relationships to our world. Or the impossible responsibility of human actions that have a global impact. Or, in Carpenter’s characteristically succinct language in the afterword (‘Modifications on The Gathering Cloud’):

The Gathering Cloud aims to address the environmental impact of so-called ‘cloud’ computing and storage through the overtly oblique strategy of calling attention to the materiality of the clouds in the sky.

Online, The Gathering Cloud appears as a palimpsest of moving images, interacting as a series of animated gifs. To read this work is to move with it. Fragments of text respond to the hover of your mouse. Symbols march across the screen and align in multiple combinations. The experience, in other words, is just like using the internet. There is more here than you will ever be able to discover, and yet the format entices you to keep looking. The world of the browser is both (seemingly) infinite, and controlled by your gaze.

The first images you see are cloudscapes taken from Luke Howard’s Essay on the Modifications of Clouds (1803). Howard was the first person to devise a popular and scientific naming system for the clouds in the sky. His process was based on natural history classifications, Latin naming principles and the fact that clouds are subject to endless change. His project was such a success that we still use his cloud nomenclature today. But, as Carpenter points out, ‘The language of The Cloud is a barrier.’ Here, she is talking of the language of cloud computing, and how its association with the mutable territory of the sky fails to communicate its dirty, real-world effects. But the language of the clouds is also, always, a reference to Howard’s system and its structuring aim: a grand attempt to explain the (previously) unexplainable, to box in the search for knowledge, to capture what is not still there.

The illustrations that accompanied Howard’s published text were minutely detailed etchings based on his own watercolours. In the book, Carpenter describes the journey of the images as technological as well as scientific artefacts, ‘Translated into cross hatching,’ she writes,

Howard’s studies

lost subtlety, but gained fixity, moving

them toward the diagrammatic scientific.

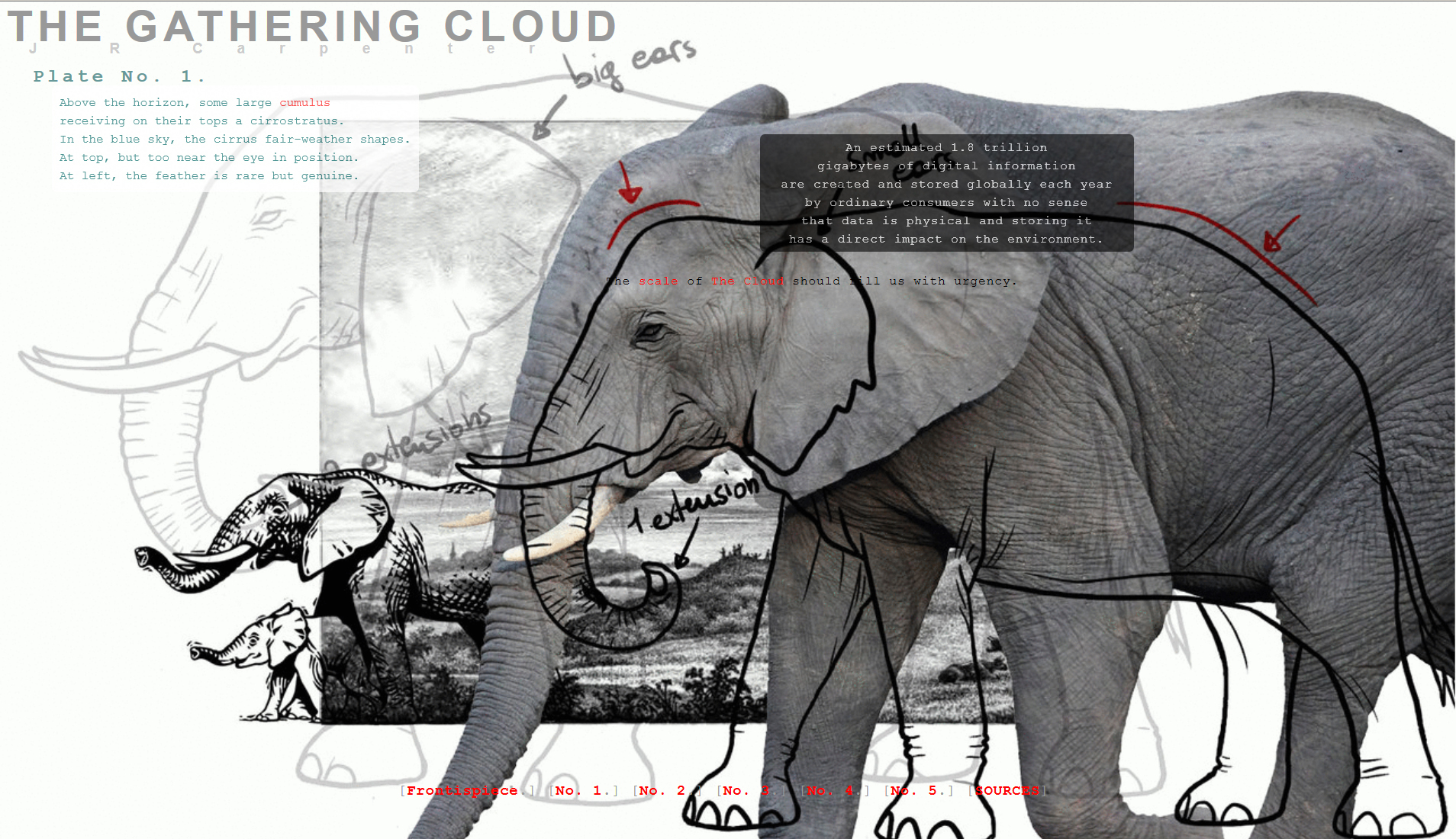

Carpenter uses these pictures, then, to draw attention to how we understand the world as well as what we (try to) understand. Onscreen, she overlays them with photographs and illustrations of animals – elephants, birds, beetles – which echo metaphors evoked in fragments of her poetic text (‘A cloud the weight of one hundred elephants’, for example, ‘How many more birds/ have been captured and tagged and stored in The Cloud?’). Like the etchings, these animal images bear the time-stamp of specific systems of thought. Some are scientific and precise, for example, and belong, stylistically, to a process of classification: illustration as pedagogic tool.

In a final conceptual twist, each of these interwoven, visual elements has been ‘materially appropriated’ (Carpenter writes), ‘from publicly accessible cloud storage services.’ These, then, are pictures of weather clouds, and of the ways we think about weather clouds, and of the technological border patrols that control the ways we think. These are images preserved in the hardware of server farms, which means they are also images of the billow of fossil fuels, the gasp of countless lives and minerals, ground into the earth over geological time, as unimaginable in scale as the size of the data stores themselves, or the climate change precipitated by the energy they need.

Tech giants Apple, Amazon and Microsoft

power their twenty-first century clouds with

dirty nineteenth-century coal energy.

And here is the context for Carpenter’s words: lines of hendecasyllabic (eleven-syllable) verse arising inside, on top of or behind the images, borrowing and interpreting found texts from Howard’s nomenclature and contemporary media studies. All of this, finally, is the context for you: the reader/user, dragging your finger across your mouse pad as you enact the dynamic complexity The Gathering Cloud represents:

To miniscule cumulus water droplets

air is an upwelling thermal below them

is as dense as honey is to a pebble

five thousandths of a millimetre across.

As a work of digital literature, then The Gathering Cloud is an extraordinary marriage of concept and content. By which I mean literally extra-ordinary: representing and exceeding the ordinary functions of its source images and texts. While the work is hosted online, however, its rhizomatic affect has less to do with technology than with attention. In an interview in 2010 Carpenter said, ‘I imagine my target audience being people sitting at desks pretending to do other things. Like work, for example. Or writing. Because they are already pretending, their minds are wide open. [1]’ The Gathering Cloud is a lucid dream space for people not entirely in charge of their dreams.

*

The most obvious difference between the printed and online versions of The Gathering Cloud is that the book feels primarily textual. Featuring an extended prologue, the book showcases Carpenter’s writing on spacious pages, interspersed with occasional black and white ‘plates’ taken from the digital piece. Simply framed in this way, the power and precision of her words come to the fore. The hendecasyllable format produces a bare, pared down kind of language that sounds natural and restrained, like a conversation with someone who has much more to say. Describing the ancient Roman philosopher Lucretius’ theory of clouds, for example, Carpenter writes:

Nothing can be created out of nothing.

The whole earth exhales a vaporous steam.

Meaning hangs like a lifetime between these lines. The gap between ‘nothing’ and the exhalations of the earth is as big and as small as a breath being held.

Like the skeleton of a bird’s wing, each line in Carpenter’s perfectly crafted, fragile text takes the body of the work in a new direction. And yet, the most thrilling element of the book is not textual, but visual.

In print, some of the words appear greyed out. Twenty-first century readers recognise this allusion, immediately, as a hyperlink; but of course, there is nothing to click on a printed page. A book is an emblem of past decisions in a way that online experiences pretend not to be. These un-links, then, are uncanny. They promise potential, in the same moment as they fatally disappoint. They wave to the future but they are, literally, pulped emulsions of the past. They call to a space beyond the page, ripe with forbidden fruit, humming with endless desire: more knowledge, more dreaming, more distraction.

An estimated 1.8 trillion

gigabytes of digital information

are created and stored globally each year

by ordinary consumers with no sense

that data is physical and storing it

has a direct impact on the environment.

These un-links represent everything you want and everything you can’t have. They are the spaces for you to dream in and the alarm that stops you dreaming. They are the endless potential of the internet, and the finite resource that will shut it down. In other words, just as the online version of The Gathering Cloud performs the limits and aspirations of older systems of thought – the acid hatch of etchings, the earnest naivety of visual or linguistic classification – so the printed work performs the futile urgency of lives lived online. In each case, the performer on centre stage is the reader/viewer, forced to confront her own ambitions and her impotence as she navigates through mutable worlds.

This, in a nutshell, is our relationship with climate change: it is about us, but bigger than we can comprehend; we are compelled to act, but crave direction; we want to dream, but we are afraid to lose. Crucially, Carpenter asks us to inhabit this relationship, not the climate itself: her work is emotional, not didactic. Instead of explaining climate change, Carpenter explores the extent to which it can possibly be imagined. Then, gently but firmly, she pushes the borders of our thoughts, and gets us to imagine some more.

‘Like a muzzled creature’, Carpenter writes, ‘the cloud strains to be/more than it is.’ The same could be said for her work, of course, and for the people who move through it. In a perfect echo of the systems of weather and data that are its subject, different iterations of the The Gathering Cloud (whether real or imagined) are held, within the reader, as memory, as action, and as technology of thought. The Gathering Cloud could signal rain, or warmth, or happiness for idle browsers,if only you could trace your finger along each acid scratched line. Could the ancients sculpt the hubris of the searching gaze? Can the Google server farms do it now?

By Mary Paterson

Review of The Gathering Cloud, JR Carpenter

http://luckysoap.com/thegatheringcloud/

Uniform Books, 2017

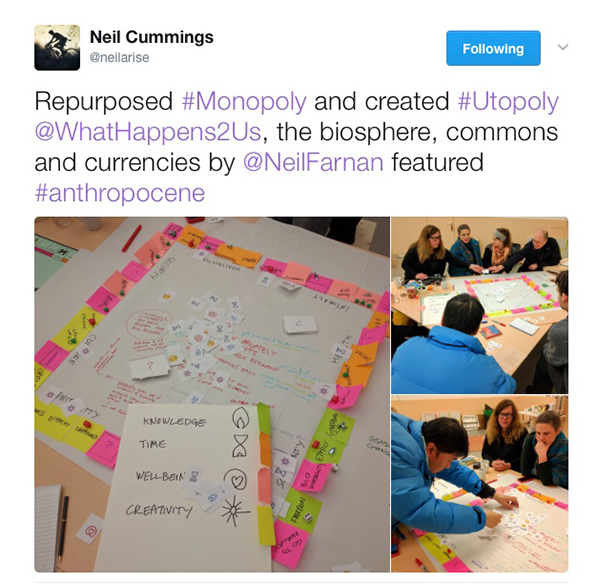

When Charlotte Webb asked me to write a piece about the future of work for Furtherfield, I immediately thought about Utopoly. Even though this game doesn’t directly discuss how we will be employed or occupied in the future, it creates a rare space where people can re-imagine a different society in which values, forms of exchange and social relations are reconsidered and reconfigured.

To better understand the ethos behind Utopoly, I interviewed Neil Farnan, who is currently undertaking a PhD at University of the Arts London with the research title ‘Art, Utopia and Economics’. He became an Utopoly advocate, introducing many ideas and concepts featured in its current iteration. Neil’s interest in designing a utopian version of Monopoly was initially shaped by his previous studies in User Interface Design, where he developed an interest in Scandinavian design practice and Future Workshops.

Francesca Baglietto: What is Utopoly? More specifically, how does it relate to and differ from Elizabeth Magie’s original version of Monopoly?

Neil Farnan: Utopoly is both a tool for utopian practice and a fun game. It draws on Robert Jungk’s Future Workshop methodology to re-engage people’s imagination and ideas for a better society and incorporates the results into a ‘hack’ of Monopoly.

Elizabeth Magie’s original game (1904) was intended to show how landlords accumulate wealth and impoverish society. Players could choose either a winner takes all scenario or one where wealth was distributed evenly via a land tax. Magie also hoped that children’s sense of fairness meant they would choose the latter and apply these ideas in adulthood. But the Monopoly we have today normalises and celebrates competitive land grabbing and rentier behaviour and Magie was airbrushed out of history and replaced with a more acceptable mythology of the American Dream.

Whilst Magie’s game informed players about the current situation, Utopoly gives people the opportunity to imagine and incorporate values and attributes they would want in a more utopian world. Players are able to determine the properties, the chance and community cards and even rules of the game. The rules being determined by the players means the game is a work-in-progress, however some features that work well can get adopted and carried through to the next iteration.

FB: As you just said, Utopoly doesn’t have a definitive form and rules but changes with each interaction. So, while the future of Utopoly is still in progress, what I would like to know is who started the project and how has this evolved so far?

NF: Critical Practice, a research cluster at Chelsea College of Arts, played a central role. We were concurrently developing both Utopoly and an event #TransActing – A Market of Values, and the current version of Utopoly is a synergy of aspects of these two projects. The first ‘hack’ of Monopoly occurred at Utopographies, co-organised by Critical Practice (28th – 29th March 2014), where the elements of the game were redesigned to incorporate utopian values. Inspired, we decided to continue developing the ideas and a second ‘hack’ took place (December 2014). Some of the ideas and values that emerged from this iteration fed into and were represented in the design of the currencies used for #TransActing. A further opportunity presented itself for another ‘hack’ within the research event ‘What Happens to Us’ at Wimbledon College of Art. This iteration was hosted by Neil Cummings and I was invited to include the currencies developed for #TransActing. It was here that Utopoly as a ‘method’ began to emerge, a method for collectively producing possible futures. I have since convened a number of iterations using a large laminated board to facilitate design adaptations and ease of play.

Additionally, researchers from the international ValueModels project (modelling evaluative communities utilising blockchain technology) recently visited Chelsea – we played Utopoly and they loved the method. They have since been inspired to use Utopoly in their research, and I’m excited to receive their feedback on how their version develops.

FB: Utopoly is experimenting with possible new monetary ecosystems in which multiple currencies and values might be exchanged. How might these currencies work and what are they inspired by?

NF: The currencies developed for #TransActing generated the concept of an ecosystem of value exchange and these are used in Utopoly. I have since come across the work of economist Bernard Lietaer, who highlights the problems of mono-currency economies and advocates for a monetary ecosystem using multiple currencies. With their origins in subjugation and taxation, mono-currencies are tools for value extraction. They also contribute to cycles of boom and bust, resulting in the withdrawal of money from the economy and the prevention of economic activity. Historical evidence suggests that economies operating multiple currencies are more resilient – they work in a counter cyclical manner compensating for this withdrawal and allow the economy to keep working.

The irony of Monopoly is that the winner is ultimately left in control of a non-functioning economy. A more preferable state would be to have a healthy flow of values in balance where people are able to exchange their contributions in a mutually beneficial way. A feature of Utopoly is that players no longer seek to own all the property but work together for the common good. The currencies are used to bring privately held properties back into the commons. The economist Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel prize for debunking the myth of the “tragedy of the commons” (Ostrom, 2015) demonstrating the benefits and effective use of common resources. Utopoly also allows economies of gifting and sharing.

I am currently working on ways of modelling innovations such as the blockchain and associated digital currencies.

FB: How would you interpret “work” in this utopian economy? For example, do you think the relation between paid work and unpaid work and/or people’s dependence on employment might be shaped in an ecosystem in which assets/values are brought into the commons to generate value/wealth for all?

Whilst not directly about work, Utopoly reflects the future nature of wealth and values in a Utopian economy. It touches on the current abstract separation of paid work from non-paid work and people’s employment dependency.

In Magie’s original game the players collect wages as they pass ‘Go’. They then buy properties and accumulate wealth extracted from other players. On one corner of Magie’s game is the Georgist statement “Labor Upon Mother Earth Produces Wages”, reminding us that land ownership should not provide unearned income.

As an economy develops people become less self-sufficient and more dependent on employment to meet their needs and a mono-currency makes the separation of paid and unpaid work even starker. The social contract that existed from 1950-70s where employers had a responsibility to their employees is disappearing. Outsourcing, short term and zero-hours contracts make the future of paid work increasingly precarious, and we also face further threats from automation and artificial intelligence.

Economist Mariana Mazzucato (2011) documents the substantial contribution of public investment to the success of today’s businesses. These businesses stand not so much ‘on the shoulders of giants’ but on the shoulders of a multitude of diverse contributions from society at large. A new social contract is needed to take this into account.

Fintech companies make much of the term ‘disintermediation’, but we also need a new form of ‘intermediation’ where contributions are reconnected and recognised. An ecosystem of currencies which register currently unpaid valuable activities together with a basic income could meet this need. This approach is suggested in Utopoly where people collaborate to contribute values and are valued for their contributions. The properties are brought into the commons to generate value and wealth for all.

FB: Playing seems to provide a very rare space in which, by operating in an interstice between reality and fantasy (what the psychoanalyst Winnicott called a transitional space), it is still possible for the players to imagine alternatives to our current economic system. Would you agree that the main political purpose of Utopoly is to provide such a space in order to reopen the capacity to be imaginative about economic and societal organisations?

NF: This is the utopian aspect of Utopoly, using people’s imagination as a means of prefiguring the future. We endure in a society where the mainstream orthodoxy would like us to accept that ‘there is no alternative’. One of the last great taboos is money and the associated economic system. If you consider our mono-currency as a societal tool imposed from the top down, it shapes and informs how we behave and the values we are expected to live by. In a way, it is like DNA; if we can change the DNA of our economy we could create new exchanges, values and social relations. We have become so used to this abstract construct that it is the water we swim in and the box we need to think out of. In order for people to start thinking that another world is possible we need to open up a space for imagination to play out. Art, games and play are some of the few remaining arenas available to engage in speculation about the future. Utopoly fulfils many research functions including acting as a tool for inquiry and reflexion, and a means of modelling future possibilities. It is rare for people to have the opportunity to criticise the existing state of society and work out how to reshape it. By allowing people the space to consider different approaches we can start to encourage better societal norms of exchange and interaction and construct new social contracts.

Economic theory states that technological change comes in waves: one innovation rapidly triggers another, launching the disruptions from which new industries, workplaces and jobs are born. Steam power set in motion the industrial revolution, and likewise since the 1990s a torrent of digital and software developments have transformed industries and our working lives. But the revolutionary very quickly becomes humdrum, and once-radical and efficient innovations like the telephone, email, smartphones and Skype, become part of everyday, even mundane experience. Despite all the time-saving devices we have successfully integrated into our lives, there is a collective anxiety about the current wave of technological change and what more the future holds. Mainstream dystopian visions of our relationship with technology abound, but are we in fact engaged in a group act of cognitive dissonance: using our smartphones to read and worry about robots taking over our jobs, whilst wishing for a shorter work week and more time for creative pursuits?

The British Academy recently brought together a panel of experts in robotics, economics, retail and sociology to talk about how technology is reshaping our working lives. This review summarises some of their thoughts on the situation now, and what developments lie ahead. Watch the full debate here.

Helen Dickinson OBE reported on the British Retail Consortium’s project, Retail 2020, a practical example of how technology is changing consumer behavior and affecting firms in her industry. The UK’s retail sector has on the one hand embraced technology and created a success story. The UK has the highest ecommerce spend per head in the developed world, with c15% of transactions taking place online, and at 3.0m employees it is also the largest private sector employer in the UK. However, beneath this, internet price comparison ushered in fierce price competition. Retailers are using technology to improve manufacturing and logistic efficiencies to control costs and offset shrinking profit margins. Physical stores are closing as sales migrate online. The BRC predicts a net 900,000 jobs will be lost by 2025. Nor will the expected impact be even: deprived regions are more reliant on retail employers and so will be more affected by job losses. Likewise, the most vulnerable, with less education or skills and looking for work in their local area, will be the hardest hit.

Prof Judy Wajcman resisted the urge to overly rejoice or despair at technological developments. For her, this revolution is not so different to the waves which have come before. It is impossible to predict what new needs, wants, skills and jobs will be created by technological advances. Undoubtedly some jobs will be eliminated, others changed, and some created. However, we can certainly think beyond the immediate like-for-like: a washing machine saves labour, but it has also changed our cultural sense of what it means to be clean. Critically, we should stop thinking of technology as any kind of neutral, inevitable, unstoppable force. All technology is manmade and political, reflecting the values, biases and cultures of those creating it. As Wajcman said, ‘if we can put a man on the moon, why are women still doing so much washing?’ In other words, female subjugation to domestic labour could have been eliminated by technology, but persistent cultural norms have prevented this from happening.

Dr Sabine Hauert is a self-professed technological optimist. For her technology has the potential to make us safer and empower us, for example by reducing road accidents, or allowing those who cannot currently drive to do so. Hauert sees a future not where robots completely replace humans, but where collaborative robots work alongside them to help with specific tasks. The crucial issue for dealing with this future lies in communication and education about new technologies, since the general public, mainly informed by news and cultural media, is ill-served by a steady drip of negative stories about our future with robots.

The short film Humans Need not Apply is one such alarming production, chiming with Dr Daniel Susskind’s altogether more gloomy view of the longer term effects of technological advances on the workforce. To date, manufacturing jobs have been those most affected by automation, but traditionally white collar jobs also contain many repetitive tasks and activities (just ask the employee drumming their fingers on the photocopier). Computing advances mean that many more of these are now in scope for automation, such as the Japanese insurer replacing some underwriters with artificial intelligence. For Susskind, it is not certain that workers will continue to benefit from increased efficiencies as technology advances. A human uses a satnav provided s/he is still needed to drive, but the same satnav could just as easily interface with a self-driving car, eliminating the need for any kind of human-machine interaction. Calling to mind the wholesale changes to UK heavy industry in the 1980s, any redeployment of labour will present huge challenges, and what work eventually remains may not be enough to keep large populations in well paid, stable employment.

Can humans benefit from robots in the workplace?The panel agreed that technological change will continue apace with wide reaching ramifications for our workplaces and our wider societies, but that it is our human qualities that will give us an advantage over machines. Perhaps this is the most pressing notion: we urgently need to recalculate the value we place on tasks within society. Work where social skills, communciation, empathy, and personal interaction are prioritised (like teaching or nursing) may develop a value above that which is rewarded today.

If we smell such change coming, it is no wonder we are anxious. The panellists differed on the ability of our society to absorb and adapt to coming technological change, and the distribution of any net benefit or loss. So, is the only option to accept the inevitable and brace for the tsunami to hit? Well, no. We need to realise that ‘technology’ is not one vast, distant wave on the horizon, but a series of smaller ripples already lapping higher around our ankles. Returning to Wajcman’s point, all technologies are created by people. If innovation has a cultural dimension, it can be influenced, so we must take heart and believe in our ability to effect change.

The further we can work to democratise and widen the pool of creative engineers, developers, artists, designers and critical thinkers contributing to the development of technologies, the broader the spectrum of resulting applications and consequent benefits to society as a whole. We can be conscious in our choices as consumers as we adopt new products and services into our lives, and challenge the new social norms emerging around work and life as technology allows us to blur the boundaries between them. And finally, we need to consider who profits, and who doesn’t, from new business models. We should lobby government to be deliberate in designing policy that looks to these future developments, and their likely unequal impacts across regions, industries and populations, to ensure that existing social inequalities are not entrenched or magnified. Hopefully the creative community can help steer this wave in the right direction, painting a vivid picture of our possible futures, to persuade the powerful to act in the interests of the greater good.

Helen Dickinson OBE, Chief Executive, British Retail Consortium

Dr Sabine Hauert, Lecturer in Robotics, University of Bristol

Dr Daniel Susskind, Fellow in Economics, University of Oxford and co-author of The future of the professions: How technology will transform the work of human experts (OUP, 2015)

Professor Judy Wajcman FBA, Anthony Giddens Professor of Sociology, LSE and author Pressed for time: The acceleration of life in digital capitalism (Chicago, 2015)

Timandra Harkness, Journalist and author, Big Data: Does size matter? (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2016)

Katharine Dwyer is an artist who considers the modern corporate workplace in her practice.

Do you believe everything you said today? How can you trust what you feel? What is it about today’s truth that makes it so difficult to believe?

The journalistic affectation for pre-fixing all manner of phenomena with the term ‘post-’ has become commonplace over the last few decades. Post-capitalism, post-growth, post-normal, post-internet, post-work and post-truth are all concepts crystalizing around a pervasive sense of uncertainty, instability and social unrest. While I have the honour of guest editing the Furtherfield website for the next few months, I am hoping to bring together a number of writers, artists and thinkers who will, in various ways, explore two of the ‘post-s’ I find most urgent and compelling: post-truth and post-work.

Consolidated by Brexit and the US presidential campaign, and designated as word of the year 2016 by the Oxford Dictionary, ‘post-truth’ is now a term deeply engrained in the social and political imaginary. Since ‘post’ can signify the internalization of phenomena (the internet is inside us all), one might even say we are post-post-truth, living with it as a general condition of our reality. The post-truth condition privileges narrative over facts, appealing to people’s beliefs, ideologies, prejudices and assumptions, rather than presenting them with ‘evidence’. This is, of course, nothing new – facts have never been anything without subjective processes of interpretation, contextualization, manipulation and propaganda. As Simon Jenkins points out, ‘Of all golden-age fallacies, none is dafter than that there was a time when politicians purveyed unvarnished truth’ – lies are, he suggests, the ‘raw material’ of political narrative.

Social media holds the potential to both exacerbate and alleviate the chaos of post-truth reality. On the one hand the echo-chambers created by partisan social media feeds limit and blinker us; on the other, social media is a weapon being deployed by armies of citizen journalists and organizations committed to fact-checking and exposing political lies and obfuscation. To feel uncomfortable about the confusion and psychological strain arising from the post-truth condition is surely a reasonable human response. As Professor Dan Kahan suggests:

‘we should be anxious that in a certain kind of environment, where facts become invested with significance that turns them almost into badges of membership in and loyalty to groups, that we’re not going to be making sense of the information in a way that we can trust. We’re going to be unconsciously fitting what we see to the stake we have in maintaining our standing in the group, and I don’t think that’s what anyone wants to do with their reason’

What Kahan points to here is, I think, an opportunity to reflect carefully on the stake we have in maintaining our sense of identity and belonging through the ‘facts’ we choose to believe. Despite the discomfort we may feel, might there be a way to take advantage of this cultural moment? Perhaps recognizing our own doubts about credibility can become a fruitful catalyst for adjusting our sense of responsibility to engage with a range of news sources, listen to opposing points of view, and critically evaluate the information we are presented with. In fact, Kahan prescribes 10 minutes of doubt every morning to deal with the anxiety that arises from a feeling that you can’t trust your own feelings.

Can we have a good life without work, or is work part of what it means to live a decent life? What would you do if you didn’t have to work?

One of the most significant societal shifts taking place due to the advancement of technology is the transformation of what it means to work, and to be a worker. The nine to five is dead (or soon will be), and work is being radically transformed as a new global workforce comes online, technological innovations advance at super high speed, and new business models emerge. Automation is now a firm feature of mainstream discourse, and depictions of robots replacing jobs are everywhere in the global media imaginary.

The Bank of England’s chief economist recently projected that 15 million UK jobs will be lost to automation in the next 2 decades, which is equivalent to approximately 80 million US jobs. 47% of white collar jobs are predicted to be lost to automation by 2035, according to a 2016 report by Citi GPS and the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford. It is not just routine tasks that will be replaced – asset management, analytics, patient care, law, construction and financial trading can all be done (and is being done) by robots. Mining giant Rio Tinto already uses 45 240-ton driverless trucks to move iron ore in two Australian mines, saying it is cheaper and safer than using human drivers.

At the same time as these developments are evolving at break neck speed, we are living in an increasingly unequal world, where the gap between the rich and poor is getting bigger. According to a recent Oxfam report, 62 identifiable individuals own same wealth as poorest 50% of the world’s population – that’s 3.6 billion people. And 1% of the world’s population own more than the rest of us combined. Capital grows faster than labour, so if you’re already rich, your money earns more than your labour ever could, which reinforces existing wealth inequality. Furthermore, extreme inequality involves people thinking greedily about finite resources, and not seeing personal greed as having wider consequences. If people see that the 1% own more than the rest, there’s danger their response is to play same game and look to join that 1% (or 5%/10%)

Not everyone is equally equipped to deal with the changes ahead, but since artists, designers and critical thinkers are amongst the best-resourced to do so, I see it as our responsibility to consider how we can help others deal with what lies ahead. As with confronting post-truth reality, acknowledging a post-work future can be seen as an opportunity to forge a better path forward for ourselves and others. We might take a cue from what we know about post-truth, and try to create narratives (backed up by collectively verified facts) that persuade the world to proceed towards an equitable world of work where solidarity and cooperation can thrive.

The articles gathered over the next two months as part of my guest editorship of Furtherfield might be understood as moments of corrective doubt. They are an opportunity to speculate about issues of truth and labour, and to proceed as artists should – by imagining alternative realities and evolving conceptual, aesthetic and practical ways to inhabit them. You can expect revelations about the labour conditions of those who work for contemporary artists from Ronald Flanagan, reflections on robots in the workplace from Katharine Dwyer, and an interview about the repopulation of Monopoly with cryptocurrencies from Francesca Baglietto. Filippo Lorenzin will consider Dada as a response to the post-truth condition, Carleigh Morgan will consider what makes good curatorial practice in this contemporary moment, reorienting current discussions away from free speech absolutism vs censorship to questions of judgement and responsibility. Alex McLean will use the metaphor of weaving to consider the role of craft in a post-work society. How might coding be understood as a form of textile liberated from its militaristic origins?

Happy doubting to all.