‘Seeds From Elsewhere’ (2016 – ongoing) is a project by They Are Here that has begun to re-animate a dilapidated play area in Finsbury Park, bringing together young asylum seekers and refugees, family, friends and other professionals. Each participant is supported to grow flowers, plants or edible produce from their respective homeland. We are also in the process of designing a greenhouse and pizza clay oven, extending the parameters of our collective activity. Throughout the process we literally and metaphorically ask ‘What can grow here that’s not from here?’ Beyond this more tangible gardening activity, the project seeks to create a space that embraces, maintains and produces a diverse set of social relationships between people with different residency status. It is supported by Furthefield an organisation exploring the intersection of networked culture and contemporary art.

It was July 2016, less than a month after the results of the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, when our project commenced. Although the impetus to begin was not a conscious response to the referendum outcome – the timing is not insignificant. Our initial steps were in a toxic political atmosphere at the height of an intensified and indiscriminate rhetoric against migrants.

Artists were faced with new variations of old questions that resurface in turbulent times. . . What is our role in protest? Do we have a particular responsibility as artworkers to engage with a given political landscape? What are the capabilities and limitations of art in local / national / international governmental politics? Such questions often reveal an expectation of certain aesthetics, rather than attitudes. It is in the multiple ways that a work is circulated and produced its politics should be sought. . . How is the work funded? How is it credited? Which voices are included in its development, or excluded? How is the work talked and written about by the various partners supporting its production?

In these seemingly small details, a larger political statement is embodied rather than solely visually evoked. At the same time, we reject a ‘one-or-the-other’ stance. Establishing and administering a small community garden should not negate working with others on larger-scale efforts at the scale of local government or beyond. Bridges should be made between all scales of activity. The same fluid hierarchies and embrace of hybridity we cultivate with Seeds From Elsewhere, we encourage at ever larger scales – generating continuities between the ethos of how we are working on the garden and how national and global resources are considered and decisions made.

‘Participation is not always progressive or empowering’, ‘Realise your own privilege’, ‘Critically interrogate your intention’, ‘Process not product’, ‘Presentation vs representation – Know the difference!’, ‘Do not expect us to be grateful’, ‘Art is not neutral’, ‘It is not a safe-space just because you say it is,’ ‘Do your research’, ‘ Do not reduce us to an issue’. These notes are from Rise (Refugees, Survivors and Ex-detainees – the first refugee and asylum seeker organisation in Australia to be run and governed by refugees, asylum seekers and ex-detainees) . . . 10 Things You Need to Consider If You are an artist not of the Refugee and Asylum Seeker Community Looking to work with our Community authored by Tania Canas, RISE Arts Director.

In a polarised mediascape, where tabloid headlines shout loudest, the reduction of a diverse group of people to an ‘issue’, has been one of the most problematic aspects of public debate. Recognising that Seeds From Elsewhere is a slowly gestating project affords time for us to slowly get to know the participants individually – who to date hail from Albania, Sudan, Congo, Ethiopia, Romania, Afghanistan & Nepal. Rather than seek to ‘represent them’, we are co-workers on a set of shared goals.

Importantly, this work functions as a hybrid activity, with multiple points of access and identification. For the young refugees the garden can offer a respite from various kinds of bureaucratic limbo, it can also simply be a place to chill in a tolerant environment. In the longer term, there maybe be the potential for employment opportunities in the garden. At the same time, the work functions within the tradition of many conceptually driven socially-engaged artworks, notably Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982) by Agnes Denes, Edible Estates (2005 – ongoing) by Fritz Haeg and Parkwerk (2014) by Jeanne van Heeswijk.

The project has also become a gateway to consider the language of rhetoric against migrants, as well as that of sympathetic media too, focusing on the recurrence of botanical language as metaphor (soil, roots etc). Essays by US-based anthropologists Dr. Lisa Malkki and Dr. Stefan Helmreich have been particularly insightful. The latter quotes biologist Banu Subramniam, noting that these criteria ‘resonate unfortunately with xenophobic anti-immigration language in the United States and Europe’:

“The parallels in the rhetoric surrounding foreign plants and those of foreign peoples are striking … The first parallel is that aliens are ‘other’ … Second is the idea that aliens / exotic plants are everywhere, taking over everything … The third parallel is the suggestion that they are growing in strength and number … The fourth parallel is that aliens are difficult to destroy and will persist because they can withstand extreme situations … The fifth parallel is that aliens are ‘aggressive predators and pests and are prolific in nature, reproducing rapidly’ … Finally, like human immigrants, the greatest focus is on their economic costs because it is believed that they consume resources and return nothing.” [1]

Becoming attuned to language is a vital part of a larger and never-ending exercise in developing cultural and individual self-awareness as to how we speak, itself inseparable from how we think.

Our fortnightly group meetings in the garden are rich in debate and banter. Working on a garden is an unceasing process. Like the growth of plants themselves, it cannot be rushed without compromise. This notion of maintenance is akin to a healthy democracy. Rather than an invitation to vote every four years, democracy must be attended to daily; it is comprised of multiple systems collectively supporting each other. Beyond physical access to a voting booth, there is the need for both protection and scrutiny of the media, investment into an education system that encourages voters to make informed choices, the space for satirists, philosophers and artists to critique power and the continual checking of our own presumptions and privileges.

Harun Morrison + Helen Walker

They Are Here

February 2017

contact@theyarehere.net

“Your work is so Dada, its just weird…” Even though the sentence was uttered playfully and with no foul intentions, it hit me. It sounded dismissive; in my ears, my friend just admitted disinterest. Calling something “weird” suggests withdrawal. The adjective forecloses a sense of urgency and classifies the work as a shallow event: the work is funny and quirky, slightly odd and soon becomes background noise, ’nuff said. I tried to ignore the one word review, but I will never forget when it was said, or where we were standing. I wish I had responded: “I think we already know too much to make art that is weird.” But unfortunately, I kept quiet.

In his book Noise, Water, Meat (1999), Douglas Kahn writes: “We already know too much for noise to exist.” A good 15 years after Kahn’s writing, we have entered a time dominated by the noise of crises. Hackers, disease, trade stock crashes and brutalist oligarchs make sure there is not a quiet day to be had. Even our geological time is the subject to dispute. But while insecurity dictates, no-one would dare to refer to this time as the heyday of noise. We know there is more at stake than just noise.

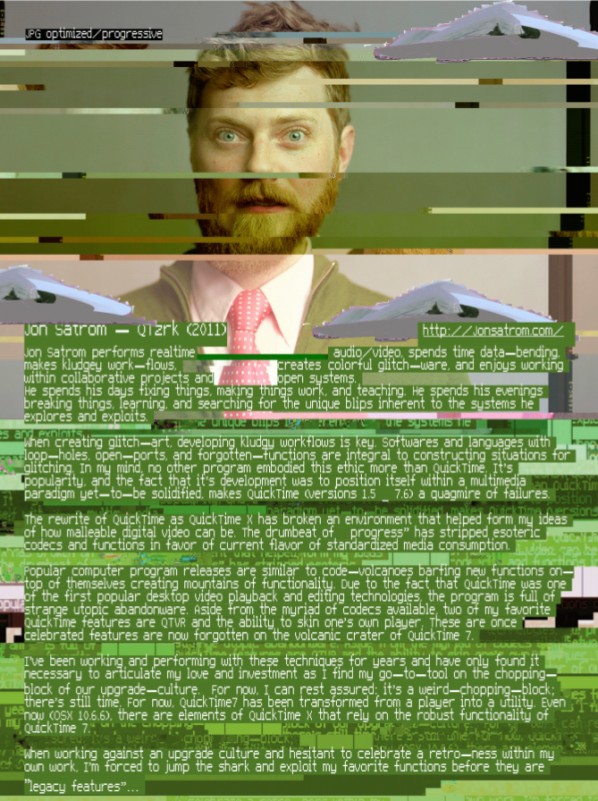

This state is reflected in critical art movements: a current generation of radical digital artists is not interested in work that is uninformed by urgency, nor can they afford to create work that is just #weird, or noisy. The work of these artists has departed from the weird and exists in an exchange that is, rather, strange. it invites the viewer to approach with inquisitiveness – it invokes a state of mind: to wonder. Consequently, these works break with tradition and create space for alternative forms, language, organisation and discourse. It is not straightforward: it is the art of creative problem creation(Jon Satrom during GLI.TC/H).

In 2016 it is easy to look at the weird aesthetics of Dada; its eclectic output is no longer unique. The techniques behind these gibberish concoctions have had a hundred years to become cultivated, even familiar. Radical art and punk alike have adopted the techniques of collage and chance and applied them as styles that are no longer inherently progressive or new. As a filter subsumed by time and fashion, Dada-esque forms of art have been morphed into weird commodities that invoke a feel of stale familiarity.

But when I take a closer look at an original Dadaist work, I enter the mind of a stranger. There is structure that looks like language, but it is not my language. It slips in and out of recognition and maybe, if I would have the chance to dialogue or question, it could become more familiar. Maybe I could even understand it. Spending more time with a piece makes it possible to break it down, to recognize its particulates and particularities, but the whole still balances a threshold of meaning and nonsense. I will never fully understand a work of Dada. The work stays a stranger, a riddle from another time, a question without an answer. The historical circumstances that drove the Dadaists to create the work, with a sentiment or mindset that bordered on madness, seems impossible to translate from one period to the next. The urgency that the Dadaists felt, while driven by their historical circumstances, is no longer accessible to me. The meaningful context of these works is left behind in another time. Which makes me question: why are so many works of contemporary digital artists still described—even dismissed—as Dada-esque? Is it even possible to be like Dada in 2016?

The answer to this question is at least twofold: it is not just the artist, but also the audience who can be responsible for claiming that an artwork is a #weird, Dada-esque anachronism. Digital art can turn Dada-esque by invoking Dadaist techniques such as collage during its production. But the work can also turn Dada-esque during its reception, when the viewer decides to describe the work as “weird like Dada.” Consequently, whether or not today a work can be weird like Dada is maybe not that interesting; the answer finally lies within the eye of the beholder. It is maybe a more interesting question to ask what makes the work of art strange? How can contemporary art invoke a mindset of wonder and the power of the critical question in a time in which noise rules and is understood to be too complex to analyse or break down?

The Dadaists invoked this power by using some kind of ellipsis (…): a tactic of strange that involves the withholding of the rules of that tactic. They employed a logic to their art that they did not share with their audience; a logic that has later been described as the logic of the madmen. Today, in a time where our daily reality has changed and our systems have grown more complex, the ellipses of mad logic (dysfunctionality) are commonplace. Weird collage is no longer strange; it is easily understood as a familiar aesthetic technique. Radical Art needs a provocative element, an element of strange that lures the viewer in and makes them think critically; that makes them question again. The art of wonder can no longer lie solely in ellipsis and the ellipsis can no longer be THE art.

This is particularly important for digital art. During the past decades, digital art has matured beyond the Dadaesque mission to create new techniques for quaint collage. Digital artists have slowly established a tradition that inquisitively opens up the more and more hermetically closed—or black boxed—technologies. Groups and movements like Critical Art Ensemble (1987), Tactical Media (1996), Glitch Art (since ±2001, and later a subgenre that is sometimes referred to as Tactical Glitch Art) and #Additivism (2015) (to name just a few) work in a reactionary, critical fashion against the status quo, engaging with the protocols that facilitate and control the fields of, for instance, infrastructure, standardization, or digital economies. The research of these artists takes place within a liminal space, where it pivots between the thresholds of digital language, such as code and algorithms, the frameworks to which data and computation adhere and the languages spoken by humans. Sometimes they use tactics that are similar to the Dadaist ellipsis. As a result, their output can border on Asemic. This practice comes close to the strangeness that was an inherent component of an original power of Dadaist art.

But an artist who still insists on explaining why a work is weirdly styled like Dada is missing out on the strange mindset that formed the inherently progressive element of Dada. Of course a work of art can be strange by other means than the tactics and techniques used in Dada. Dada is not the father of all progressive work. And not all digital art needs to be strange. But strange is a powerful affect from which to depart in a time that is desperate to ask new critical questions to counter the noise.

Thanks to Amy J. Elias and Jonathan P. Eburne

NotesImages in this article are part of the exhibition Filtering Failure curated by Julian van Aalderen and Rosa Menkman in 2011.

Catalogue of exhibition here:

http://www.slideshare.net/r00s/filtering-failure-exhibition-catalogue