Buy Now and use code: CSF19ASRA for a 30% discount

In India, the practice of jugaad—finding workarounds or everyday, usually non-technical hacks to solve problems—emerged out of subaltern strategies of negotiating poverty, discrimination, and violence. Yet it is now celebrated in management literature as ‘disruptive innovation’. In this book Rai considers how these time-efficiencies always exceed their role in neoliberal and authoritarian postcolonial economies and are put into motion by subaltern practitioners themselves.

On Sat 27 Apr from 14.00-16.00 Rai will introduce this important work to guests followed by a Q and A session with Furtherfield Co-Founding Director, Marc Garrett – with plenty for time for discussion.

This event is hosted at Furtherfield Commons in Finsbury Park* and has been supported by the Borderlines Research Group in Creative Economies and Postcolonial Intersectionality at Queen Mary, University of London.

“This original and innovative work will enable a new and perhaps paradigm-shattering interpretation of the coimplication of digital assemblages, temporality, and affect. Drawing on a rich ethnographic archive, Amit S. Rai is deeply sensitive to how gender, class, and caste are implicated in emergent techno-perceptual assemblages. His invaluable book is also an effective antidote to the Eurocentricity of digital media studies.” — Purnima Mankekar, author of Unsettling India: Affect, Temporality, Transnationality

“Jugaad Time is an important intervention into cartographies of postdigital media cultures. By drawing on the specificity of South Asian cultures, it enriches our understanding of the heterogeneity of these processes. The postcolonial study of media technologies is a vibrant and crucial field of inquiry; Amit S. Rai’s outstanding work is an essential contribution to global approaches to new media scholarship.” — Tiziana Terranova, author of Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age

The event form parts of Furtherfield’s 2019 programme Time Portals.

Octavia E Butler had a vision of time as circular, giving meaning to acts of courage and persistence. In the face of social and environmental injustice, setbacks are guaranteed, no gains are made or held without struggle, but societal woes will pass and our time will come and again. In this sense, history offers solace, inspiration, and perhaps even a prediction of what to prepare for.

The Time Portals exhibition, held at Furtherfield Gallery (and across our online spaces), celebrates the 150th anniversary of the creation of Finsbury Park. As one of London’s first ‘People’s Parks’, designed to give everyone and anyone a space for free movement and thought, we regard it as the perfect location from which to create a mass investigation of radical pasts and futures, circling back to the start as we move forwards.

Each artwork in the exhibition therefore invites audience participation – either in it’s creation or in the development of a parallel ‘people’s’ work – turning every idea into a portal to countless more thoughts and visions of the past and future of urban green spaces and beyond.

*Please not this is a separate building to our Gallery and is at the Finsbury Park station entrance to the Park.

Valuing people is a core property of wealth creation, wealth creation can be positively bound into communities. We can’t afford not to be involved in digital creativity because it explores areas of social space that are entwined with intrinsic cultural and economic value.

The point of entry has become ubiquitous, we are everywhere, they are everywhere – I am over there and here too. Marshall McLuhan, the Canadian media theorist gave us ‘emotional extension in electronic space’ [1]before we came up with the clumsy and often misunderstood paradigm of ‘post-digital’ – a way to describe a circularity and return to being human that accepts the intersubjectivity and convergence we feel with other people and technology.

It is this corporeal and algorithmic unification and association that Furtherfield grasps; sometimes like harsh high summer nettles on uncovered hands, gathered as ingredients for a convivial soup. Not afraid to be stung or to make the soup, even though after 22 years of foraging you are not now the only voice or flag raised at the intersections of art, technology and social change. The mission is always different and always the same. This then is my provocation to you.

The case for digital creativity has grown. Why is that? Because there is deep unrest and even malevolence in electronic spaces and at their corporeal nodes. “The creative adult is the child who has survived,” says Ursula K. Le Guin.

As creative people engaged in the field we are with agency and in turn create agency; we gladly pick up refurbished laptops, remixed maps and fragmented tweets. Our fieldwork means we are in the river, standing watching by the shore, and holding up a mirror in the lobby of the hotel. We facilitate others, not just ourselves, we do it with others. Artistic people are children and not confined or restrained by common sense orders from the immaterial elite – some are pointed, focused and ready to enter the field, others are yet to claim their agency, and even more have yet to experience due North and due South. We can provide the co-ordinates, the beginning of the map and the line of sight. Artists in the future will become agents of change and observers of truth in a familiar return to base. And so we are not given to the idea, in the field, of carrying out instrumental command and we caution ourselves against suggesting this to others.

In a hotel in Sweden we listened as the French Philosopher, Bernard Stiegler brought attention to our attention. In clipped and someway jarred English, he opened up the vast chasm and problem of attention as the fundamental commodity of our age (emotionally extended, post-digital etc). His references to ‘techne’ willfully conjured up derivations from Greek – craftsmanship, craft and art. We are crafting the digital to draw attention to ourselves and our products. We are becoming products, through a process of digital reification. Lukács describes reification ‘as a relation between people that has taken on the character of a thing’[2]. So, while humans and machines merge evermore, we understand that the end-point of creative processes is not to make attention-seeking people become products and things, it is to diversify our subjectivities and illuminate the way forward for all.

The agency of artists has been a key factor in the development of the Furtherfield’s mission in its first two decades. This agency broadly disseminates to artists networks, activism, societal change, environmentalism, localism, global affairs and more recently emerging technologies such as blockchains. Within an unfolding world political landscape, these areas of interest show greater convergence and potential as moments of reflection become more important in the reified world of products. Our role is to be that reflective space for 360 degree scanning and to hold digital time up in the chain.

Our future mission grounds us on our locus in order to do this, while maintaining our global reach. We are passionate and committed to multiple points of entry, bringing in consenting and diverging voices. The ‘commons’ to us is a real thing, worth our energy and stewardship the point at which people do touch each other and listen.

We know that technology will not save us and furthermore we propose that this is not the right question. In working in partnership with academics, businesses and other institutions we are always asking ourselves where progressive change can come from, in a series of open dialectical spaces. Finsbury Park offers us a node in which to conduct business and make new wealth – cultural, social and economic capital. The predication of wealth creation on technology alone is too simplistic when a multitude of tools are needed. Our approach to the idea of the ‘commons’ is to use old and new tools and ways of getting things done together..

As McLuhan says: “Once we have surrendered our senses and nervous systems to the private manipulation of those who would try to benefit from taking a lease on our eyes and ears and nerves, we don’t really have any rights left. Leasing our eyes and ears and nerves to commercial interests is like handing over the common speech to a private corporation, or like giving the earth’s atmosphere to a company as a monopoly.” (from Understanding Media, 1964.)

We are not isolated from the huge pressures of the global economy, when advancements outstrip the ethics and the algorithms that come to define new normative patterns and processes. The role of digital creativity and artists is now fully emerging as one that reconnects them and us back into the critical space that Goya, Galas and others occupied. So, we can hold up time and re-enter it at a different point. Yes, Furtherfield offers time travel!

The disruptive power of technology is evident in its ability to unhinge and even eliminate existing businesses, local centres and distribution methods. This is not new, just as McLuhan defined electronic extension in the 1960s, Clayton Christensen defined ‘Disruptive Innovation’ in his book The Innovator’s Dilemma in 1997. However, digitally disruptive business models such as Uber are now mainstreamed and fast-tracked into our everyday experiences. With the advance in real time data and algorithms these disruptions can have a dramatic effect in social and economic terms. We are faced with a shift in the language from the progressive and anti-establishment power of Punk and music culture; into the realms of digitally distributed start-ups, iterative technologies and remix culture.

It is time to invent another future, lest we will become the disrupted and not the disruptors.

Image credit: Museum of Contemporary Commodities by Paula Crutchlow at Furtherfield 2016

Hi Shaina! Tell us about the genesis of CAMP? How are you part of it? Why are you called CAMP?

CAMP came together as a group in 2007, initially consisting of me, Shaina Anand (filmmaker and artist), Sanjay Bhangar (software programmer) and Ashok Sukumaran (architect and artist) in Mumbai, India. The intersection of our skills and different backgrounds created a vital spark in which to experiment with technology and ask deep questions about form and ways of making radical political work. We are called CAMP as we are not an artist’s collective (though we began as a collaboration with KHOJ which was an artist’s collective in Delhi, which you headed operations for) but we call ourselves a studio. In this process, we try to move beyond binaries of art vs non-art, commodity market vs free-culture and to build media for the future. Personally, it gives me the platform to eschew conservative approaches to documentary filmmaking with “the colonial male gaze.”

How did you decide to create new-media and be part of CAMP coming from a strong documentary tradition?

Oh, for that I would like to describe the response my younger self (1992-2004) had to making traditional documentaries. Travelling around India with my mentor, filming a documentary about life in villages for the anniversary of Indian independence, I described how they’d turn up in jeeps, find the subjects, and ask important questions for the nation. I became increasingly disillusioned by what I saw as the repeated orchestration of finding a subject, interviewing, zooming in, asking questions until the subject ends up crying. So, once while analyzing the relationship between filmmaker and subject I echoed the question hovering over so many discussions, “who speaks for the subject and from where?”

That’s when I decided that I had two choices, to either move into fiction which was perhaps less problematic, or to “stay with the trouble”, to let the problems drive the work into becoming something more in line with my politics. I also wanted to “trouble” the triangular relationship of author, subject and technology, so that it favored the subject more.

Very interesting! You mentioned Haraway’s “staying with the trouble”. Were you influenced by her work? Say more! I relate to that experience, having switched from working in Bollywood to doing social documentaries and now learning new-media art. So, what role do you think technology plays in fostering that relationship between the subject and the author and more importantly, how does it “favor” the subject?

Well, yeah. I feel influenced by her as a woman media-maker where I draw from her reflections on race, technology and gender. In CAMP’s work at various biennials, I have often felt that every part of the process of documentary-making had been deftly unpacked and put back together again to reflect vital contemporary political concerns within the actual structure of the work or even its distribution, not just its content. By that, I felt we succeeded in using technology to foster that relationship.

I find it fascinating that technology is not a toy or gimmick in your work but rather gives to access to places and people which traditional approaches to documentary wouldn’t. In this context, could you throw some light on the use of CCTVs in your work esp. at a time when they were increasingly being used as a tool for surveillance?

In our work Al jaar qabla al daar (The Neighbour before the house- 2009), we used CCTV cameras and set them up to film the houses where eight Palestinian families had been forcibly evicted and are linked to remote controls in new homes or refugee places where the families now live. We were then able to zoom and tilt the cameras to spy up washing or as they went about their business. The complexities of the power relations between the observer and observed are dazzlingly deft and agile, giving energy to the otherwise hopeless situation of displaced Palestinians in Jerusalem. We only hear their voices as they trace the lines of personal memory in their old neighborhoods or stalk the new inhabitants of their former homes with the remotely operated CCTV placed on nearby rooftops. We see soldiers training, Orthodox Jews going to prayer, a boy skateboarding, roofs, water tanks, a veranda built by their own families. Their bodies exert a ghostly presence on the very image we see onscreen as a small boy exhorts his mother to “zoom, zoom”– to spy on one of the new inhabitants leaving the house. But nonetheless through the active manipulation of this technology we had “captured” a settler.

Do you think technology facilitates a democratic or rather liberal exchange for the subject? Let’s say immersive technologies like virtual and augmented realities, which I’m interested in, blur the point of view of the author and the subject. What do you think?

The act of wrangling the technology to record the voices of the camera operators while simultaneously filming does create a power shift. For example, in our work, the Palestinian families may be physically invisible in the places they once lived, but their voices and ability to control how we see with even the crudest of cameras, exerts its own pressure. It acknowledges and celebrates the democratization of the camera and makes us question the veracity of all the other images we have seen about Palestine. We hear details about the neighborhoods, how the evictions happened through impossible laws or enforcements as the displaced families observe how the new families don’t clean the stairs or water the lemon tree.

Yes, I liked the use of the footage as a timeline for viewers to edit which led you to form Pad. Ma (Public Access Digital Media Archive) which I was a part of too, at some point. Interestingly, here at UCSC, I met and heard Bernard Stiegler who had long ago worked with annotating found-footage with his students thereby that puts CAMP in that discourse. Say something about that.

Well, for me, the most radical and exciting approaches to documentary were in the 60s in India. Since then, what has changed? Nothing here. CAMP’s work provides a sense of new possibilities as it steals back technology and puts it into that utopian discourse of Stiegler and others to shift our perspective closer to the subjects. By “troubling” the traditional methods of creation and dissemination it empowers both the viewer and the viewed with a fresh perspective.

Some of your work is about migrant population, home and displacement which strikes a chord with my interest in human-rights and immigration. Tell us about this work and its approach.

A privileged perspective into the worldview of another is contained in our work, From Gulf to Gulf invited by the Sharjah Biennial a few years ago.Yet again it is a document of a much richer process that began as an artwork/ community provocation/ friendship built over four years between CAMP and a group of sailors from the Gulf of Kutch in India. Initially CAMP produced radio programs culling material from sailors’ songs, conversations, phone calls etc. and later that evolved into a new-media piece that showed this totally different space in a radically fresh way. It is composed of footage of their journeys and extended selfie- films shot by the sailors on their long voyages, often accompanied by songs which they Bluetooth to each other.

Fascinating! Lastly, I’m keen to hear about what CAMP wants to do with technology next?

At any given time, CAMPwants to challenge the triangular relationship of author, subject and technology, thereby splintering the privileged gaze and our standard mode of perception. That’s our motivation behind whatever we have or will do.

Thank you Shaina for speaking as an artist from CAMP. It was great to talk to you and have worked with you all!

On January 17th 2017 outgoing American President Barack Obama commuted the 35 year sentence of whistleblower Chelsea Manning. She was to be released on May 17th 2017. The Disruption Network Lab (DNL) Berlin has in the past addressed various forms of disruption techniques. In celebration of Manning’s release, the DNL, which is under the curation of Tatiana Bazzichelli, decided to devote their latest event, Prisoners of Dissent, Locked Up for Exposing Crimes to the voices of dissent of our time.

DNL’s new event-venue is a historic Berlin theater called the Volksbühne (“People’s Theater”) that stands on the Rosa-Luxemburg square. The square’s namesake was a famous anti-war activist and communist revolutionary. Rosa Luxemburg was murdered for her political activism by right-wing paramilitaries in 1919. Thus, the new location draws an historic parallel between dissidents and the often violent ways they are silenced.

While attendees waited for John Kiriakou to present his new book, “Doing Time Like a Spy: How the CIA Taught Me to Survive and Thrive in Prison“, the wood-heavy 1920s-style saloon of the Volksbühne was completely filled with people, leaving not a single chair free. Kiriakou served in the CIA as an analyst and officer for 14.5 years and is now a whistleblower of their practices. He was operating in the Middle East with a focus on counter-terrorism and human rights. In 2007 he brought to light that the CIA was using waterboarding as torture and was subsequently alleged to have disclosed the identities of undercover CIA agents. For this, he was charged with violating the 1917 Espionage Act under U.S. Law and had to spend two years in a low-security prison in Pennsylvania.

In 2014, while Kiriakou still served his sentence, his pixelated lego-portrait was among the 176 political prisoners of Ai Weiwei’s artwork “Trace” that was part of his Alcatraz show in California.

Kiriakou is a man in his early fifties with a likeable charisma. But as one would think of a spy, there are many more dimensions to his character, and he is only hinting at these while reading from his book. Recounting how he made use of his CIA training in daily prison life – living between Mexican drug kingpins, Neo-Nazis and Italian mafia members, he concedes that he can also be a man with nasty manners – if he has to. (Kiriakou points out that the CIA hires individuals with sociopathic tendencies). The audience listens closely while he describes his prison encounters with an enthusiastic storytelling voice. In one anecdote that reminds me of high-school politics he describes the Italian mafia members he made friends with. They made sure that another inmate who pulled Kiriakou’s name through the dirt would be “taken care of”. There is a lightness and sense of humor to Kiriakou’s character. His stories, often punctuated by laughs from the audience, are witty and fascinating. One easily gets lost in listening to them, nearly forgetting the seriousness of the situation he had to bear.

Kiriakou, who had six passports with six different backgrounds and survived two assassination attempts, also mentions the psychological stress and pressure whistleblowers struggle with. As he states that all whistleblowers have their own moments of desperation, I’m reminded of the two suicide attempts Chelsea Manning undertook and the harsh reality of injustice whistleblowers have to experience under their governments.

According to Kiriakou, his motivation came from a patriotic disposition which compelled him to act when the government violated constitutional rights. Snowden states a similar reason, although it is rather interesting that Kiriakou more or less accidentally became a whistleblower, which differentiates him from many others who made a conscious choice of disclosing information in the first place.

The book is definitely worth a read (the copies he brought were sold out by the end of the event) as it gives a unique and very personal insightful view into a CIA officer’s life post-whistleblowing.

In the Q&A session that follows the book presentation, Kiriakou is asked whether in hindsight he would have done anything different. In response he gives two pieces of advice to future whistleblowers: First, get an attorney before you go public with information. Second, don’t trust anyone. Well, somehow what one would expect from a spy?

The second part of the event consisted of a panel with four guests, that was moderated by Annegret Falter from the Whistleblower Netzwerk e.V.. To introduce Chelsea Manning’s case, a video from the Chelsea Manning Initiative Berlin was shown, which documented their activity from 2011 until now. As a prelude to the panel Annegret Falter read Manning’s public statement, which was released on May 9th by her legal team. She quoted Manning’s words:

“[…] Freedom used to be something that I dreamed of but never allowed myself to fully imagine. Now, freedom is something that I will again experience with friends and loved ones after nearly seven years of bars and cement, of periods of solitary confinement, and of my health care and autonomy restricted, including through routinely forced haircuts. […]”

The short statement implies the outstandingly harsh conditions Manning, being a transgender woman in an all-male prison, had to live under the past seven years. The exceptionally severe sentence for exposing crimes was commuted by Obama after an outpouring of public support over Manning’s mistreatment in prison and with the prospect of a Trump presidency, many feared for Manning’s life.

Manning was charged under the Espionage Act, which was introduced in 1917 shortly after the U.S. entered the First World War. Many critics see it as a legal relic – an outdated federal law, originally applied to individuals interfering with the U.S. war effort. It is now abused to persecute whistleblowers, among them Daniel Ellsberg, John Kiriakou, and Edward Snowden. Not only is this law incompatible with human rights and civil liberties, but legal scholars argue that it is written so vaguely that a fair trial is impossible in addition to it being unconstitutional

One of the guests on the panel was the British-born Annie Machon. The former MI5 intelligence officer (The UK’s Secret Service) left the organization in 1996 after the Security Service was involved with a branch of Al-Qaida in a plot against Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. The assassination failed and several civilians lost their lives. Consequently she resigned and teamed up with her then-partner David Shayler – an MI5 officer himself – to blow the whistle on the crimes and incompetence of the intelligence community. He was later accused under the 1989 Official Secrets Act, and the three-year exile and two-year legal battle against her former partner publicly became known as the Shayler Affair. Machon wrote a book about the affair, speaking out about both their motivations and the legal injustices the pair endured.

Machon had extensive experience on a professional and personal level, making her an expert on issues like the war on terror, whistleblowing, and the U.K. legislation. Criticizing the U.S. Espionage Act of 1917, Machon pointed out that it was the U.K. that gave the world a notion of such laws with their 1911 Official Secrets Act. While the 1911 law was originally used for spies betraying the country, it was adapted in 1989 to specifically target whistleblowers. New legislations on surveillance, secrecy, and whistleblowing pushed state power even further forward while continuing on a downward spiral. Machon expressed concern that the world would follow the U.K.’s example once again. Clearly she was advocating for a necessity of legal protection for whistleblowers, instead holding criminals to account, not jeopardizing the liberty of the brave individuals who feel compelled to speak out.

On the subject of the psychological issues whistleblowers suffer with, which Kiriakou addressed earlier, she added that the stress also had an effect on Shayler. With a worried voice she said that he now believes himself to be the reincarnation of Jesus Christ.

Another guest on the panel was the Danish-born human rights activist Magnus Ag, who works for Freemuse, a global organization advocating freedom of artistic expression. Underlining the importance the arts play as a powerful medium of dissent, he quotes Picasso: “Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth.”

Various cases worldwide remind us of artists experiencing oppression, censorship or imprisonment for their work. From the feminist Russian punk-rock band Pussy Riot, facing a two-year sentence for protesting Putin, to Ai Weiwei who disappeared for 81 days, detained in a secret prison by communist-led China. Under the hashtag #ArtIsNotACrime, Magnus Ag and Freemuse draw attention to lesser known cases. According to Freemuse’s report, China is among the worst offenders for violating artistic freedom. He introduced the case of five Tibetan musicians who were imprisoned by the Chinese government for simply singing songs that refer to the Dalai Lama and praising Tibetan culture. For charges like “seditiously splitting the state“, as of 2017, all five remain in prison.

Magnus Ag then introduced another guest of the panel, Silvanos Mudzvova who unfortunately was not able to come in person. Mudzvova is an activist, performance artist and a man of outstanding courage. In a video portrait he was shown criticizing the corrupt government of his home country Zimbabwe via the means of art. Dominated by Mugabe since 1980, Zimbabwe suffers an immense financial crisis, besides the recent scandal of $15 billion USD that had been raised from diamond sales and gone missing. Protesting and addressing these issues, Mudzvova staged a public performance in front of the parliament. For his art, he was abducted, tortured, and almost lost his life. Unfortunately, the country is affected by heavy censorship that targets activist, artists, and journalists. As Mudzvova says, he uses art as a catalyst in order to achieve change in the world.

One may ask what makes art so powerful that governments fear it, which brings me back to Picasso’s quote. Art can spark a thought, question the status quo, and subtly shed light on the obscure. Art therefore makes us not only realize a truth, but it can start a revolution – something regimes fear. Hence organizations such as Freemuse take an important role in providing a platform to protagonists of dissidence, bringing those cases into the conscious realm or even guiding them into safety.

I found myself deeply appreciative the presence of Mudzvova’s work on the panel as it provided an artistic and non-white perspective on enduring violent oppression from a dictatorship, thus adding to the wide spectrum of activism.

The tone of the event urgently suggested the necessity for a global paradigm shift on the perception whistleblowers: from a prosecuted traitor to a celebrated truth-teller. Such a shift would have to be underpinned by legislative means. The suggested solution was to rewrite laws so political dissent can be protected instead of prosecuted. Looking at the legal definition of a whistleblower, it is a person that sheds light on evidence of fraud, abuse or illegality in the public interest. Why would exposing crimes be followed by imprisonment?

One can hope that Chelsea Manning’s release sets an example to nourish new thoughts and laws for future whistleblowers to be better protected. Whistleblowers have always been important players in the modern political landscape within the democratic model. They refuse to conform to the hegemony, have moral principles, and an awareness of the power of information. As such they enable change for the better and for the more transparent which a fortiori reinforces the fundamental values of democracy: civil liberties, freedom of expression, participation, and peacemaking.

Without the courage of whistleblowers and activists who often put themselves in great danger, our world would look very different. This teaches us that one should practice dissent, be it as a whistleblower of injustices, in the field of arts, or in any form of disruption. In the words of Hannah Arendt, who Annegret Falter quoted in her closing of the panel: “Nobody has the right to obey”.

________

Photocredits: Thomas Schmidt

The next Disruption Network Lab event is planned for November, so make sure you follow DNL on their website on and on twitter

Support John Kiriakou‘s legal defence by buying his book here

Consider donating to the Courage Foundation supporting whistleblowers

Find out more about the Chelsea Manning Initiative Berlin and the Chelsea Manning Welcome Home Fund

Find out more about the work of the Whistleblower Netzwerk e.V.

Follow the speakers on twitter:

@JohnKiriakou

@AnnieMachon

@AgMagnus

@SilvanosVhitori

Review on PRISONERS OF DISSENT: Locked Up for Exposing Crimes, Berlin 2017. By Berit Gwendolyn Gilma

Featured image: Pandora’s Dropbox by Matt Bower

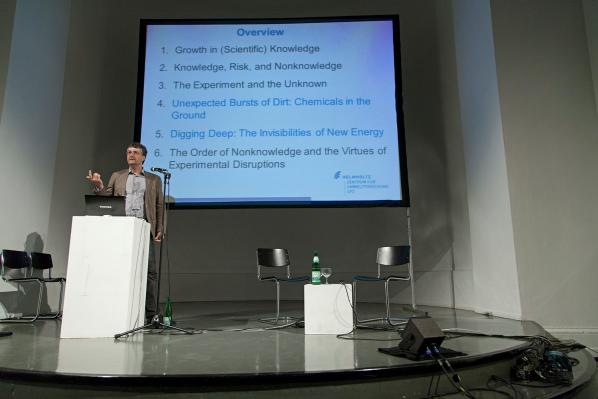

The Disruption Network Lab (DNL) has been presenting in Berlin some of the finest platforms for the discussion of art, hacktivism and disruption, presenting academic debates on not-so-conventional forms of thought. In their event IGNORANCE: The Power of Non-Knowledge, the second in the series Art and Evidence, various scientists and researchers discussed ignorance, not merely as a subaltern issue but as a central tool in knowledge production.

In previous events, DNL debated how ignorance is deployed as a mechanism of truth and power negotiation, mainly through the omission of the known by the means of secrecy, obfuscation and military classification. There are many forms of understanding ignorance, and this program intended to elucidate the potentialities and pitfalls within the concept. According to DNL, the first step towards approaching ignorance is to recognise it and become aware of it. As co-curator of DNL Daniela Silvestrin said (despite the paradox) that it is necessary to render the “unknown unknown into a known unknown.” The field of ignorance studies investigates the spread of ignorance, what kind of forms it takes depending on the context, how science “converts” it into probabilistic calculations of risk, and even how it can be used to push certain political, economical or religious agendas.

In the opening keynote, Matthias Gross, a sociologist and science studies scholar who has written extensively on ignorance studies, co-editing with Linsey McGoey the “Handbook of Ignorance Studies,” starts by stating that “new knowledge always creates new ignorance” and that throughout history humans have been in constant relation – acceptance, denial, resignation – with the unknown. Gross has covered how ignorance operates in different scientific milieus, namely, how risk is widely used in natural sciences as an attempt to project an idea of the future, as demonstrated in weather forecasting, but also how not knowing operates in everyday life; through secrets, the spread of false knowledge, feigning ignorance, or even through actively not wanting to know.

Gross presented a compelling body of research, exposing numerous examples in which ignorance serves the purpose as a tool to acknowledge what we don’t know in science (important in fields such as Epidemiology) or how positions of power use ignorance to manipulate public opinion within our social structures. However, the debate felt somehow stranded in an optimistic loop, where ignorance was seen mostly as a catalyst to search for further knowledge. Yet, I believe, while duelling with the binary knowledge vs ignorance, one should never forget to tackle the universalistic shape that ‘knowledge’ tends to adopt. In the end, the discussion felt insufficient, failing to examine knowledge/ ignorance from a non-hegemonic perspective when it would have been interesting to borrow criticism from postcolonial or feminist thought.

The first panel, moderated by Teresa Dillon, was deemed to shake the consensus in the room by joining the moralistic perspectives in science, the forbidden and undesired, the paranormal and the apocryphal together. Sociologist Joanna Kempner presented astonishing research focused on ‘negative knowledge,’ described as taboo, dangerous or threatening to the status quo. In an attempt to demystify the neutrality of knowledge production in sciences, Kempner interviewed various scientists to discover forbidden areas in their fields. The outcome of this research revealed that due to a fear of loss of funding and/ or sullying their reputation, scientists restrain themselves from researching illegitimate topics. For example, in Psychology one is expected not to study extra-sensory/ paranormal senses as these studies are usually associated to parasciences, a term that is in itself revealing of the hierarchies of knowledge. Kempner also exemplified how knowledge production is pressured by political interests and recalled the research-bans during the G.W.Bush government that cut funds to research related to sex and drugs under the assumption that remaining ignorant about any possible positive aspects (of recreational drug consumption) guarantees the maintenance of conservative moral values.

On the maintenance of moral values, the philosopher Jan Wieland presented an interesting experiment: “What would you do if you wouldn’t know? And what would you do if you’d know?” Giving the example of a social experiment by Fashion Revolution, a movement that calls for “greater transparency in the fashion industry”, Wieland examined consumers’ choices as they acknowledged the conditions in which clothing is actually produced. The project invokes a sentimental story with an excerpt from the daily life of a young girl living in Dhaka, Bangladesh, who works in a garment factory. Coming to terms with the girl’s story, the reactions differed — from not buying and empathically connecting with her situation to total indifference and still buying. Wieland attempts to analytically evaluate their intentions, good or bad, and how ignorance affects choices, stating that some of us might willfully remain ignorant (willful ignorance) as a way to better cope with our habits of consumption. However, I find it difficult to extrapolate these findings to a moralistic and individualistic criticism of people’s consumerist choices, since we know there is a structure that keeps consumers far from well-informed. A good example of how economy capitalises on ignorance, we know that the international division of labour is intentionally built to alienate the consumers from the “dirty” phases of production.

Jamie Allen, artist and researcher, also analyses at the economy of non-knowledge that is in the genesis of apocryphal technologies. “Do pedestrian’s crossroads’ buttons actually work?” We have all thought about this, yet has it stopped us from pressing the buttons? As long as we do not know whether a certain technology actually works, it “works”. Such an economy is boosted by acknowledging that some things remain as common ignorance. If we are not sure whether a lie detector works or not, then it can be used to incriminate — amidst ignorance, it shall produce the truth.

Informative and somewhat frightening, “Merchants of Doubt”, directed by Robert Kenner (2014), reveals how bendable ‘truth’ is in the interests of big corporations. The documentary investigates how the tobacco industry spread false information among firefighters, leading the world to believe that the domestic fires caused by cigarettes were the fault of the furniture rather than the cigarettes. This is where it goes from uncannily funny to scary. While interviewing scientists, whistleblowers and activists, the film unveils the dreadful story of corporate campaigns designed to unleash confusion and scientific scepticism among the masses, putting the life and security of millions at stake. This scepticism is not passive, thus it turns into a cynical endeavour. As corporations claim that there is no consensus surrounding issues such as global warming, conferences and books are forged to sustain their statement, while scientists who defend the existence of greenhouse gases are accused of ceding to their political biases in order to get funding for their research. What about facts? They seem to become irrelevant in the face of expensive lies.

Watch Merchants of Doubt’s trailer here.

Karen Douglas, a social psychologist, presented an empirical study of conspiracy theories whilst trying to trace a particular psychological profile of those more prone to elaborate and believe in them. Douglas used widely known conspiracy theories as examples, such as the infamous car crash that killed Princess Diana (which became a true “Schrödinger’s cat” case, instigated by the media-produced hyperreality in which Diana was both alive and dead — along with Elvis Presley) and the theory that 9/11 was orchestrated by the United States government to instigate and justify the “war on terror”. Douglas believes we are naturally hardwired to believe in conspiracy theories and sees them as a way to cope with things we are unable to answer. A socio-analytical view on conspiracy theories also seems to fail the complexity of forces that make us consider why certain theories are conspiracies and other perspectives are just theories. The issue with Douglas’ approach lies within its socio-psychological analysis, which tries to find a pathological pattern in people who believe in conspiracy theories, such as describing these people as being intentionally biased, or stating that those who tend to perceive patterns in things or believe in more than one conspiracy theory all show the “symptoms” of a conspiracy theorist. Yet, as pointed out by a member of the audience, this approach seems to lack a sensibility to the entire concept of “conspiracy theory” as a political tool to dismiss and undermine other narratives, such as narratives from an undesired other (e.g. how Russia’s government agenda is seen by the USA). Nevertheless, it is interesting to understand how these bodies of “disbelief”, should you wish to call them conspiracy theories or not, have a huge impact on our lives and inevitably our deaths (e.g. global warming, vaccination). As with apocryphal technologies, certain forms of unknown seem to crystallise as forms of knowledge – we know that we do not know and that is the way it is.

The closing panel, moderated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, has overseen our entanglement on social media and its algorithms, promising to be oracles of truth while their complex structures grow beyond our understanding. Ippolita, a group of activists and writers, warned how social media promotes emotional pornography, where our feelings are exploited by click baits in exchange for our personal data. By establishing clear metrics of interaction, like the number of likes and comments, social media creates an addictive game of forged interactivity, while we are scrutinised by biometric evaluation resultant from the same data we produce. Also analysing the manipulation of data and its weight in political agendas, Hannah Parkison, a journalist focused on digital culture, analysed Trump’s run for presidency propaganda in digital media. By using mostly social networks, such as Facebook and Twitter, Trump has kept control of his narrative without entering into risky interviews broadcast on TV. This is an effective way to get away with lies, regardless of the constant warnings from fact checkers – according to Politict 78% of what Trump said on the run for the election is not factually true. These lies spread across the internet, rendering their own truth.

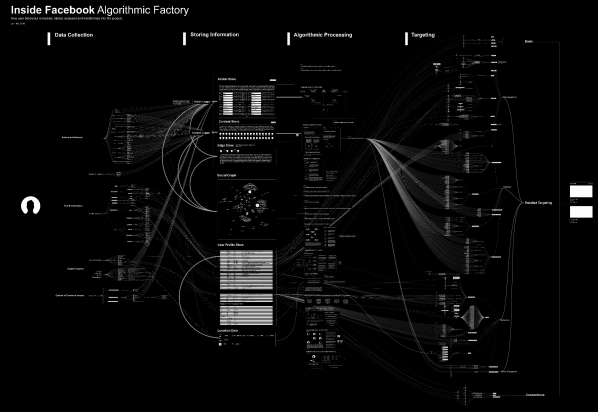

Vladan Joler, chair of New Media Department at the University of Novi Sad, presented his project in which he tries to map the tentacular structure of the Facebook algorithm, an expansive database incorporating individuals’ personal information that implies the fabrication of assumptions about potential consumers’ habits, wants and needs. Facebook was thus framed as an immaterial factory of information, the functioning of its assembly line still unknown, constantly mutating and growing. A speculative visual image of Facebook’s processes was rendered as Vladan tried to map something unknown; this mapping has similarities to the work of early cartographers. And much like early anthropological stances, the nodes of information produced have the potential to define thoughts and discussions about what we are and how we are supposed to behave. As Vladan ironically concluded, these are the tools used by the cybernet dominators – the digital monarchies that will accentuate asymmetries.

Ideas such as ‘knowledge’ find resistance and defiance from other epistemes that fall out from the western-centric productions of knowledge, such as the Amerindian ‘perspectivism’ defended by Viveiros de Castro or even the Alien phenomenologies (see Ian Bogost) that instigate the thought of non-anthropocentric ontologies. Bearing those in mind, I found that talking about the ‘dark’ side of knowledge is an invitation to dismantle and boycott its mechanisms of production, sustained in frail ideas of “truth”, “reality”, or “science”. In addition to the initial concept of ignorance, the conference provided a fertile ground for questioning the multiple ways in which humans deal with intangible phenomena, try to bypass obscurity and profit from that same obscurity. It provided insight on the relevance of knowledge to map and create reality, while bodies of power render webs of mystification of the tangible – corporations forging lies, politics of manipulation, cultural colonisation – reproducing ad nauseam epistemic violence.

The third edition of the Art and Evidence series from Disruption Network Lab, which took place on the 25th and 26th of November, wrapped up with the event TRUTH-TELLERS: The Impact of Speaking Out. TRUTH-TELLERS asks a question that could not be more crucial at the moment: “Can we trust the sources and can the sources trust us?” We have recently experienced a presidential battle between Clinton and Trump in which one of the most divisive topics were the thousands of emails sent to and from Hillary Clinton’s private email server while she was Secretary of State. A battle from which Trump left victorious despite having failed almost every fact-checking test. While Assange is forbidden to use the Internet for fear of him interfering with the presidential run in the USA, Chelsea Manning remains convicted, sentenced to 35 years of imprisonment due to her 2013 accusations of violating the Espionage Act. DNL gathered hacktivists, privacy advocates, investigative journalists, artists and researchers to “reflect on the consequences of leaking and whistleblowing from a political, cultural and technological perspective”. Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding, this could have been the very last DNL event. Let’s hope not, as these are vital, particularly in times of political despair.

Features Image: “Dead Copyright” installation view, 2015

Antonio Roberts is a digital artist based in Birmingham. In 2011 he has completed his Masters level studies in Digital Arts in Performance at Birmingham City University. His artwork focuses on the errors and glitches generated by digital technology. An underlying theme of his work is open source software and collaborative practices. His video work has been screened in Chicago, Illinois, at GLI.TC/H, Notacon in Cleaveland, Ohio, and Newcastle Borough Museum and Art Gallery, amongst other places.

In October 2015 he opened his first solo exhibition, “Permission Taken“, at Birmingham Open Media and in these weeks is taking part to “Jerwood Encounters: Common Property” (15th January – 21st February 2016, Jerwood Visual Arts), a group show curated by Hannah Pierce focused on the limits of Copyright when it’s about visual arts, with two projects: the installation “Transformative Use” and a collection of four works, “I Disappear”, “Blurred Lines”, “My Sweet Lord” and “Ice Ice Baby”.

Filippo Lorenzin: You’ve been always interested in how corporate and industrial logics affect daily life and art. How did you get interested in these questions?

Antonio Roberts: It’s a by-product of my interest in open source software and free culture, something which I’ve been interested in from as early as 2002 but only started taking seriously around 2007. One of the main motivators of this was my reaction to Adobe Photoshop and its influence on creative practices. My experience of studying Multimedia Graphics – and I’m sure the same can be said for Graphic Design, Illustration and any creative practice – was that it seemed more like an exercise in how to use Adobe products, not how to be creative with tools. It felt like Adobe software had gone from being one of the many tools for creating art to the art in itself. This corporate sponsorship of course has many implications for how we create and disseminate art. It poses restrictions and dictates who and who cannot create art.

FL: Copyright issues are one of the main focuses of your research and this fascinates me because of your age. You (as me, by the way) have experienced probably the most troublesome period for Copyright systems, with the wide spread of p2p networking and remixing approaches to cultural industry products. What do you think?

AR: I’m inclined to agree. I’ve had access to the internet since I was around 14 years old and in that time I’ve seen the internet and culture as a whole change drastically. For me the rise and fall of Napster, spearheaded by Metallica’s very public outcry against it, signalled the beginning of the end of the free internet that I had only known for not even a year.

Around that time Digital Rights Management (DRM) became a hot topic. The entertainment industry saw it (and suing everyone) as the only way to protect their property and so kept bundling DRM with their products, which often at times resulted in a broken experience for the user. One example that springs to mind was the attempt to make CDs unreadable by computers (and so prevent ripping), by adding in corrupted data at the beginning of CD. Whilst it did temporarily stop people to using it on computers – you could simply use a marker pen to circumvent it – it also prevented some CD players from using the CD and in general was obtrusive. This cat and mouse game is still going on to the point where simply attempting to bypass DRM to watch/listen to something that you have purchased, can be an illegal act.

As mentioned before, It wasn’t until around 2007 that I began to reconsider how Copyright affected my work. By this time I saw that there was more weight being pushed behind open source software, free culture and things like the Creative Commons licences, and so I started to get involved myself. The first stage was ditching all proprietary software (which I did in 2009) and then licensing my work under Creative Commons licences.

FL: “Jerwood Encounters: Common Property”, curated by Hannah Pierce, is a group show that seeks to investigate the new borders of Copyright, especially in regard of art. How would you define the state of these questions in UK?

AR: I think Copyright as a whole is in a terrible state. As Cory Doctorow suggests in the exhibition programme (which is in itself an excerpt from his book “Information Doesn’t want to be Free”) Copyright as we know it isn’t written for artists or any individual. Its verbose terms and complexities cannot be understood and are probably not even read by most of us. They are written for other lawyers. If, in order to go about our creative business, we are expected to read and understand the terms and conditions and law – it is estimated that it would take 76 days to read all of the Ts and Cs of websites we use – what time do we have to be creative?

FL: What’s your point of view, from your position as an artist?

AR: I think Copyright is a mess because it tries to dictate how we should be creative. Creativity is free-flowing. Copyright, and its cousins patents and trademarks, justify their existence by saying that these restrictions encourage innovative new ideas but what they do is just stop us.

FL: “Dead Copyright” reminds me some reflections by Walter Benjamin on the shock of the city, about how advertising assaults our senses 24/7 with louder and louder messages – until it reaches a state of entropy. At this stage the message isn’t actually more important than the media itself, quoting Marshall McLuhan, and all the brands create a single, colourful ambient. How much this reality has been voluntarily planned by corporations, in your own opinion?

AR: I think it’s all completely planned. The more pervasive the advertising becomes the more we accept it as part of our every day life and culture. On the other side this does mean that they have to try ever more invasive methods to get our attention. Think about the uproar over the Coca Cola van at Christmas, or Cadbury’s at Easter. They have usurped the original holidays and are more important.

FL: The reduction of brands to colorful simple shapes created something that visually reminds some of op art works, a movement that experimented with visual perceptions and that has been an important inspiration for fashion and design. I was just wondering what you think of this similarity: is there any real connection between your work and those works?

AR: Yes, certainly and this comes through with my use of glitch art techniques. In glitch art we’re often trying to find signal in the noise, and I find that many successful glitch art works (however you define successful) have some resemblance to the original yet are transformed and destroyed in way.

FL: With “Transformative Use” you use shapes that recall not just brands, but a wider imagery. It’s as if you’re focusing on other targets: can I ask you how did you get interested in this new research?

AR: I recalled all that I had learnt during my residency at University of Birmingham and during the CopyrightX course. From this I paid particular focus to the Sonny Bono act from 1998. This effectively extended the Copyright terms so that it won’t be until 2023 until works from 1923 begin to enter the Public Domain. This act is sometimes called the Mickey Mouse Protection Act, which led me to use them as a focus point for the work. Mickey Mouse should, by now, be in the Public Domain but they’ve fought to stop this in order to “protect” their brand.

People in favour of long or perpetual Copyright terms usually point to it allowing artists to reap the benefits of creating work. In truth, however, only a very small percentage of works made will be profitable in the future. To put it another way, how many books published today will see reprints? I don’t have any official statistics, but I know it would be a small percentage. So, extended Copyright terms only really benefit the small percentage of artists or publishers, whilst harming everyone else.

FL: What does it mean to deal with corporate imagery within such a chaotic and in a somewhat charming ambience? I mean, what remains a logo or a character when it gets lost within this borderless blob? Are the corporations losing their borders too, maybe?

AR: Yes.

FL: As discussed before, “Transformative Use” has been inspired by two previous projects: do you think that in future you’ll make a work that will update for the fourth time these reflections of yours?

AR: Most certainly yes. “Permission Taken” will be having an iteration at the University of Birmingham in March 2016 and will feature new and existing work. Aside from this I will continue to work with found materials but with a more explicit intention to provoke discussion around Copyright.

Featured image: The facade of Kunstquartier Bethanien. Image by Nadine Nelken.

After a full year of events focusing on several topics, from drones to surveillance, cyberfeminism to hacktivism, or even the famous Technoviking and a hot debate on the politics of the Porntubes, the Disruption Network Lab wraps up 2015 with its event STUNTS, focusing on political stunts, interventions, pranks and viralities. It was a year of great success for the DNL and proof of that was a full house, in the middle of a cold Berlin winter, full of people eager to take part of this last gathering on art research, hacktivism and disruption.

Just at the entrance, in the castle-like facade of Kunstquartier Bethanien, the Free Chelsea Manning Initiative projected a video including phrases of support, denouncing the system that violently charges against all the whistleblowers who bravely stand against state-crime. Chelsea Manning, sentenced in August 2013 to 35-years of imprisonment, turned 28 years old on the 17th December. The initiative took the occasion to celebrate her anniversary but also to remind us of her cause and of how vulnerable whistleblowers are under the purview of “justice”.

Peter Sunde, one of the founders of Peter Bay, has recently given an interview stating “I have given up” when asked about the current state of free and open internet. The pessimistic tone that might loom among hacktivism has its reasons. With a growing and raging state surveillance, invigorated politics of fear veiled as anti-terrorism propaganda, or the alienating neoliberal order, the seemingly scarce possibilities to fight back can be easily overtaken by a sense of hopelessness. Yet, the proposal of STUNTS claims the possibility of new futures; suggesting that new artistic militancies and political subversions of neoliberal networked digital technologies, hoping to provide a glimpse of another world. What can be done? There’s still a lot to be done.

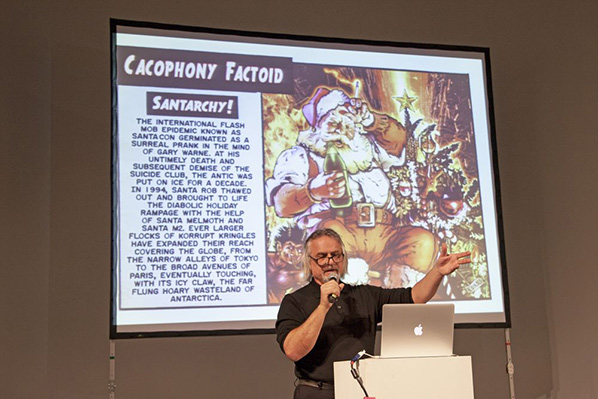

The opening keynote was reserved to John Law, original member of the Suicide Club and Cacophony Society, and one of the initiators of the Burning Man Festival, who gave an inspiring speech condensing 40 years of disruptive movements in the city of San Francisco. Law highlighted how important it was to live in San Francisco, a well-known refuge for many weirdos, hippies and punks, and how the city served as fertile ground for the foundation of many movements of disruption, such as the Suicide Club or the Cacophony Society.

The Suicide Club, born from a course at the Free School Movement (also known as Communiversity) in the late 70s, was one of the pioneers with its events of urban exploration, street theatre and pranks. For several years, its members engendered actions of occupation and appropriation of public spaces, aiming to subvert the order of these spaces and highjack the authorities. Later on, some of its members founded the Cacophony Society which followed the same footsteps, creating social experiments and stunts, which according to Law didn’t necessarily mention being political but instead playful acts of liberation from the norm. Yet, in an age of overwhelming neoliberal labour exploitation, we can wonder if having fun among the working class isn’t already a political act. As Law said, “the events were illegal but not immoral” reminding everyone that in ethics and politics of disruption, right and wrong should never be defined by law. It seems that disruption is intrinsically political in the sense it questions the ruling order while also being an emancipatory act of dissidence.

PANEL: STUNTS & DUMPS – THE MAKING OF A VIRAL CAUSE

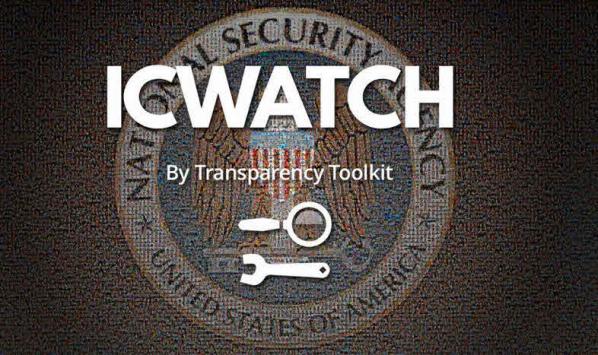

The panel, moderated by Ruth Catlow, one of the founders of Furtherfield, included a group of four hacktivists and disruptors, two of whom claimed to have once been Luther Blissett, an open-pseudonym used by several artists and activists as an hoax who has taken credit and responsibility over several stunts and pranks over the past 20 years. Following the thread of adopting an emancipatory praxis in the demand for privacy, M.C.McGrath presents the Transparency Toolkit. Motivated to refuse of data collection and the brute quantification that intelligence and corporations enforce as an interpretative lens for evaluating people’s lives, with this toolkit McGrath intends to facilitate the access to a database that allows journalists and civilians to surveil the surveyors. Providing easy access to personal data of the intelligence community, he gives intelligence a taste of its own poison. In response to the predictive justice portrayed by nowadays algorithmic supremacy, the Transparency Toolkit disturbs the power asymmetry while possibly enabling for even some form of critical mob justice.

Andrea Natella, creative director of guerrigliamarketing.it and KOOK Artgency, seeks for justice by creating elaborate hoaxes that corrupt corporate advertisement. Hoaxes such as the fake air company Ryanfair which claimed to “welcome aboard refugees” under the Geneva Convention, enabling refugees to fly without a visa. The ingenious mockery resulted in a flamed response from the ‘real’ company debunking the advertisement while at the same time it has received a great attention from the media, resulting in a broader public discussion on the refugee situation. Once again, Natella presents us with the power of disruption by taking advantage of tools used by the prevailing order.

The undergraduate in Computer Sciences Mustafa Al-Bassam has gained notoriety for being a part of LulzSec, a computer hacking group responsible a number of high profile attacks, resulting in being legally banned from the Internet for two years. From an early age Mustafa focused his time in the creation of tools to unmask the tenacious mechanisms of domination. From ironically proving the negative correlation between tests scores and the amount of assigned homework to denouncing violations of online privacy and security perpetrated by state agencies such as the FBI, Mustafa has been a main character in the defence of human rights in the post-digital era.

To close the panel, Jean Peters, co-founder of the Peng! collective, shifts the perspective of the debate. What if instead of blaming or attacking members of intelligence we could provide them the tools to liberate them from their own institutions? Recognising that within the intelligence community resides a great number of whistleblowers, Intelexit, which started as a hoax, is now an initiative that helps people leave the secret service and build a new life. Aimed specially at members of agencies such as CGHQ or NSA, Intelexit offers safe and encrypted channels of communication through which intelligence members can get access to legal and moral support. Without the intention of dismissing responsibility of these members, claiming some banality of evil, by emancipating intelligence members Intelexit conceives another possibility to disrupt the system from within.

CELEBRATING AT SPEKTRUM

With an incredible array of playfully disruptive tools and practices, the ending tone of the panel is of hope and optimism. Maybe this is the kind of optimism that inspired Chuck Palahniuk into writing the Fight Club, clearly influenced by the Cacophony Society of which he was a member. Optimistic disruption seems to pave way to new worlds of possibilities, into a new future envisioned with the help of DNL.

To close STUNTS in an even more optimistic way, the celebration of a year of DNL was at SPEKTRUM, another outstanding initiative in Berlin and another example of success. After less than a year of activity, SPEKTRUM, an open space that aims to link art and science, has already gathered a solid reputation in the field along with a trustee community of followers and participants. While we cross fingers for another year of funding for DNL, SPEKTRUM will continue to offer a rich program of concerts, performances, installations and debates.

Last Review – PORNTUBES: Reveals All @Disruption Network Lab, Berlin. By Pedro Marum, 2015

http://furtherfield.org/features/porntubes-reveals-all-disruption-network-lab-berlin

Featured image: Nishant Shah, Roy Klabin, Francesco Warbear Macarone Palmieri, PG Macioti and Liad Kantorowicz

Finally I had the pleasure to attend to a session of the Disruption Network Lab. Physically, let’s say. Even though this was the first time I’ve managed to be in Berlin for one of its events, I’ve been a compulsory virtual follower, watching the videos of their fully recorded sessions. This is a hint for anyone who would like to watch all the previous keynotes and talks.

With its first edition in April, Disruption Network Lab is an ongoing platform of events and research on art, hacktivism and disruption, held at Studio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien, in partnership with Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, in Berlin. On 31st of October it has held its 5th session, PORNTUBES: Sharing the Explicit. Aiming to discuss the role of porntubes in the sex and porn industry it gathered porn practitioners, entrepreneurs, sex work activists and researchers, to engage in a debate on the intertwining of porn with the Internet.

Pornography has always been a pioneer in using new technologies for its distribution and promotion. Internet, by allowing anonymous access to porn from the comfort of everyone’s home it seemed to be the ultimate tool for the porn industry’s expansion, to say the least. As pointed by Roy Klabin during the talk, 38,5% of the time we spend on the Internet is spent watching porn. As in many other spheres, it also seemed to be the beginning of a new era of labour liberation with an apparent decentralisation from the big porn production houses. This has allowed the blossoming of new small and independent companies with their own place in the market. But if cyberspace once seemed to offer a possibility to escape the tentacular control and exploitation exercised by the corporative monopolies, it is now known that the rebellion of the cybernetic innovators – creators of porntubes and new online sex tools – seems to be purely a coup d’etat.

The opening keynote was by Carmen Rivera, a Mistress and Fetish-SM-performer, with a long history in the porn industry business, with an experience of the migration of porn from cinema to VHS and later to the Internet and then onto the porntubes. In conversation with Gaia Novati, a net activist and indie porn researcher, Carmen tells us her personal and professional story and immediately gives a better understanding on how porntubes – such as Redtube, X-Hamster or Youporn – have an ambiguous influence in the porn industry. Once perceived as a democratic tool allowing small porn producers to expand their radius of audience-reach, Rivera explains how much of a perverse tool of exploitation it has become and one that small producers have become too dependent on.

The fast pace of the Internet creates a lot of pressure to satisfy the hunger of porn consumers. As has become virtually infinite “fast-porn” is closely aligned with the capitalist paradigm of production, putting a bigger focus on quantity rather than quality. As the Internet leaves no space for durability — one day you’re in, the next day you’re out — careers become frail, the work of these companies are highly precarious and the concept of the “porn-star” is a short lived mirage.

Rivera also highlights how online piracy has become virtually unavoidable resulting in gigantic losses to the porn industry. As producers see their films ending up on porntubes free of access, lawsuits don’t come as a viable solution but as financial black holes for any small or even medium companies. Even though the future doesn’t seem bright, Rivera doesn’t quit. Her battle cry: we need to create a bigger awareness of the pestilent system that controls the online porn industry. New tools of disruption need to be found to fight against these new power asymmetries established through the domination of cybernetic capital.

After the keynote, the discussion shifted to examining new tools of online sex work such as the project PiggyBankGirls, self-proclaimed as the first erotic crowdfunding for girls. Unfortunately, Sascha Schoonen, CEO of the project, wasn’t able to attend. Instead a short promo video was presented introducing the project, giving some tongue-in-cheek examples on how girls could profit from this crowdsourcing tool.

Women upload videos pitching their ideas or projects – financing a shelter for stray animals, the payment of tuition fees, a trip to Japan, – and then share online porn performances in exchange for support from “occasional sugar daddies”. Although one wonders if this isn’t just a euphemism – a sanitised version, let’s say – of already existing tools used by women who need money, regardless of them making public how they intend to spend money Nevertheless, it is true that the actual exploitative system needs to be dismantled, workers should be getting a bigger share for their labour and PiggyBankGirls poses as one more tool to do so, however this project also left many unanswered questions. Who are actually the women who can profit out of it? PiggyBankGirls promo tries to make this form of sex labour sound “cute”, easy and accessible. However, is just another tool for established porn actresses to diversify their means of income?

The panel, moderated by Francesco Warbear Macarone Palmieri, socio-antrophologist and geographer of sexualities, included abstracts showing a wide array of perspectives on the issue of porntubes and online sex work. The researcher Nishant Shah opened the panel with a wonderful talk ranging from porn consumerism to porn politics and how porn is influencing our digital identities. In a porn-consuming society, from establishing clear distinctions between “love” and “porn”, respectively meaningful and perverse, desirable and visceral desire, porn seems to be contingent on the morals of the spectator – as it only exists through the spectator it has also become a tool of puritan regulation. From Facebook teams of censorship and sanitisation of the virtual space to websites such as isitporn.com it is possible to understand that the concept of porn becomes itself a regulator of our sexual expressions, defining the line that separates decency from indecency. Paving the way to the pathologization of porn practices but yet dictating the meaning of authentic sexual performances, as the only visceral forms of sexual performances available, Shah pointed out how pornography, as a cultural and digital artefact, works in the regulation of our societies and in the production of our identities. Giving the example of Amanda Todd, who committed suicide after suffering from bullying for exposing her sexual body online, Shah shows how new forms of “porn” take place in the digital, from doxxing to unintended porn being perceived as such, enabling new forms of violence – let’s say porn-shaming.

Also focusing on porn consumerism, Roy Klabin, investigative documentarist/filmmaker, goes back to the discussion initiated with Carmen Rivera on porntubes VS porn producers and how producers make money. According to Roy, MindGeek, the company that owns most of the porntubes – from Youporn to Redtube – has been one of the main entities responsible of the destruction of the porn industry. By creating piracy websites holding gigantic libraries of free access to porn and making revenue out of the advertisement, resulting in huge losses for the porn companies which at the same time had become dependent on the tubes to advertise their work. Roy makes an appeal to porn producers to diversify their strategies: from webcams to virtual reality, the porn industry needs to be one step ahead of the contemporary systems of digital exploitation.

PG Macioti, a researcher and sex workers rights advocate and activist, together with Liad Kantorowicz, performer and sex workers’ activist, presented an overview on how the Internet has reshaped sex work – from sustainability to work conditions – listing some of the outcomes, pros and cons, of the extension of sex work to the virtual spaces. Online sex work, namely erotic webcam work, has enabled a proliferation of sex work by offering safe, independent and anonymous services. On the other hand with the insertion of sex work on the capitalist mode of production, just like in many other forms of digital labour it has rendered a bigger alienation to the workers – who work mainly alone and, also due to stigma, don’t share any contact with fellow colleagues – resulting in a more and more precarious labour, with sex workers being paid by minute, having to pay for their own means of production and usually paying a big share of their income to the middleman webcam services host agency.

Overall, the Internet has enabled a multiplication of narratives on sex work but the power asymmetries between the online corporations and workers results in a growing exploitation and precariousness. The transversal message to all participants seems to urge for disruptive tools for online sex work, tools of self-empowerment and emancipation within the digital paradigm. Quoting the Xenofeminism manifesto by Laboria Cubonics, “the real emancipatory potential of technology remains unrealised” and the Disruption Network Lab might be the much needed spark for this revolution.

The PORNTUBES event couldn’t have had a better ending with a party held in the legendary KitKatClubnacht, a sex & techno club that is open since 1994, famous for both its music selection and its sexually uninhibited parties. It seems an exciting idea, to say the least, to bring all together researchers, porn entrepreneurs and activists to this incredible venue after an intense afternoon discussing the porntubes.

Concluding the series of conference events of Disruption Network Labs during 2015, the next event will be STUNTS: Distributed, Playful and Disrupted, taking place on the 12th of December, at the Studio 1 of Kunstquartier Bethanien, and the direct link is: http://www.disruptionlab.org/stunts/. This time the discussion will focus on political stunts as an imaginative and artistic practice, combining hacking and disruption in order to generate criticism of the status quo. As the immense dragnet of state-surveillance extends it becomes imperative to understand which are the available tools of obfuscation, how it is (still) possible to hack the system and which tools of political resistance can be deployed Disruption Network Lab wraps the year with a tempting offer, inviting artists, hackers, mythmakers, hoaxers, critical thinkers and disrupters to present practices of mixing the codes, creating disturbance, subliminal interventions, giving raise to paradoxes, fakes and pranks.

Angela Washko is an artist, writer and facilitator devoted to creating new forums of discussions in spaces most hostile towards feminism. She is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Carnegie Mellon University. Since 2012, Washko has also been facilitating The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft, her most known project: it’s a series of actions taken within the virtual space of World of Warcraft (“WoW”), an online video game set in a fantasy universe in which people play as orcs, knights and wizards. Her research is focused on the social relations between the gamers, with great attention towards on how these relate with feminism and women, who are becoming more and more numerous between the players of this game. Washko investigates also how design elements of the game influence the relationships of the people who inhabit it; it’s a social study on a community expanding more and more widely, and acts within a limited set of rules designed by video game producers.

Filippo Lorenzin: I’ve read in some your previous interviews that you started playing WoW in 2006, so we can say you’re a veteran gamer. In the same interviews you pointed out many important elements linking to some of my own research. First of all, the fact you didn’t hesitate to make a parallel between IRL public spaces and online public spaces makes me think you’re part of a generation (as me) that doesn’t care of this division. You create situations and opportunities to let people discuss: it’s as if you meant online gaming as a social activity, rather than a set of rules designed by programmers in which people interact as NPCs (“Non-Player Characters”). What do you think?

Angela Washko: I wouldn’t say that I don’t make a distinction between online and offline space… rather, that these spaces are so integrated and much less separate than the outdated “it’s online/digital therefore it’s not real” model. Online gaming is a very general term and they each have a specific way of operating with contexts that have particular ways of allowing players to communicate to each other. Some of those games are designed to institute high degrees of collaboration in order to get to the most difficult content. World of Warcraft falls into this category. This coercive collaboration breeds a social/chat structure which makes the game as much of a social space as a play space.

My work in WoW is about analyzing the user’s social culture created within the otherwise fantasy oriented landscape and talking to players about the way that it’s developed. So of course there are thousands of things I could have focused on within WoW (and in The World of Warcraft Psychogeographical Association I focus more on exploring the landscape free from quest suggestion/utility and drift about exploring), but for The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft I was driven to work the way I did due to the treatment of women by the community within the space once players establish their self-identified gender behind the screen. At least on the servers I was playing on.

FL: Your use of WoW mechanics in order to raise questions about sexuality and identity makes me think of situationist approaches. As they wanted to create new urbanism refecting the grounded needs and identities of the people, and your actions seem to lead to the creation of a new gaming system, based on players/people who aware of the characteristics of the game and their results in the definition of their identities. Am I wrong?

AW: I guess in WoW I was wondering why the politics of everyday life outside the screen had to govern the rules of this otherwise epic and otherwise not-human-like landscape. I wondered why women were excluded or treated as though they were inherently unskilled (naturally/biologically non-gamers) and at the same time were rewarded for being willing to be abstractly sexualized in guild hierarchies and elsewhere. After being asked to “get back in the kitchen and make [insert player name here] a sandwich” enough times, I stopped playing for a bit. And then I returned, determined to figure out why this was an ubiquitous approach to talking to women in the game space. So I wanted it to be in a place where we could openly discuss and potentially become more considerate about communal language to the point that it could become a much more inclusive space for everyone, and maybe a more diverse social space than we all curate for ourselves in our everyday (physical space) life. Why did our identities outside the screen still have to govern how we are treated as orcs and trolls and whatnot? This game still holds onto a lot of the qualities of the avatar-hidden web 1.0 persona…

FL: Debord wrote that “the construction of situations begins on the other side of the modern collapse of the idea of the theatre. It is easy to see to what extent the very principle of the theatre – non-intervention – is attached to the alienation of the old world. Inversely, we see how the most valid of revolutionary cultural explorations have sought to break the spectator’s psychological identification with the hero, so as to incite this spectator into activity by provoking his capacities to revolutionize his own life. The situation is thus made to be lived by its constructors.”.

As you can see, it looks like he’s describing your work and I’m really curious to know your opinion.