Sam Renseiw and Philip Sanderson’s Lumière & Son project is a near perfect and altogether exhilarating sequence of moving image lyric poetry (though lyric here does not exclude humour or the grotesque) and a demonstration of how seriality and fragment – an unfolding over time, the diaristic – has quietly become one of the fundamental modes brought stage centre by the network (so much more than the rather dull ‘interactive’ which has so quickly become the standby of the monetised digital). Impossible to watch one of these pieces without the desire to watch just one more.

The set (which lives online but has been shown offline in whole and part) and its component pieces, moreover, are studies in various interesting things: the liberating effects of constraint and collaboration and what those both demand and imply; also of randomness, or perhaps better, the loose, the dashed off, differing degrees of accuracy in such collaboration (also the apparently dashed off, the apparently loose [also the apparently synchronised or ordered]).

To start with, a little history. In 2007 two young members of the digerati, Andreas Haugstrup Pedersen and Brittany Shoot, invented a form and threw down a gauntlet. The form, in fairness, was not exactly new – over 100 years old, actually – but its re-contextualisation within the digital realm and more particularly on the network was, without exaggeration, a stroke of genius[1]. It involved taking precisely the constraints affecting the films of the cinema pioneers, the Lumière brothers, and applying these to contemporary online video work. Films or videos of exactly one minute, fixed camera, no sound, no zoom, no edits. Such videos dubbed, naturally, ‘Lumières’. There was clear recent precedent in the constraints of the Dogme movement of Von Trier and others but the project also drew on the various little-bit-art-little-bit-geek, young, playful cultures which abutted and intersected the more formal area which we called, for a while, ‘net-art’, and which thrived on a sparky and often competitive and showy overcoming of the early net’s limitations of file size and bandwidth – projects like 5k.org, 10secondfilm.com spring to mind.

Additionally, because the start of modernism still does not really seem all that far away, early film was a natural reference point for many wrangling the early internet as art tool and channel both.

We responded viscerally to the sheer, almost willed-into-being, expressivity of the ad hoc devices and solutions of early film and this fitted snugly with the bodges we ourselves were employing. It gave us confidence, too, that our ducking and diving too could be expressive but also it confirmed a certain tendency to lo-fi-ness there in the zeitgeist. (I speculate – a lo-fi-ness which helped to define and declare art – useless, beautiful and human – as against the slickness of corporate design, communication and advertising… This has persisted remarkably – note the thriving on-going cult of the animated gif)

That was the form. The challenge – make some. Embrace that 100+ year old limitation and do something engaging with it. Push the form as far as it will go.

Pedersen and Shoot set up a web site where all contributions would be aggregated and indexed (in retrospect, somewhat unfortunately, by links rather than copies held on their server – much work of historical significance has already vanished. Shoot and Pedersen themselves have moved on and the site has a Marie Celeste feel). In addition to the site itself, there was a Lumière manifesto which, personally, I found a little narrowly focussed. Shoot and Pedersen seemed to invoke a near ethical dimension to the return to first principles and in their own moving image practice confined themselves to work (much of it very good) entirely within this discipline. It was clear from the huge response of other artists and film-makers though that the form clearly answered a diverse set of pressing needs. For some it was a cleansing activity, for some a sketchbook, for others a spur to invention and for others still, a challenge in the sense of “How can I observe the spirit of the rules whilst actually driving a coach and horses through them?”

Although the Lumière made next to no impression on the ‘official’ world of art video (one speculates – cynically, perhaps – too democratic and available to anyone with a cheap camera, too ontologically opposed to the expensive grandeur of high concept, too hands-dirty in a world where artists aspire to hire videographers and editors to realise their art; in short, too lacking in the conspicuous consumption that validates much contemporary work), it was enthusiastically taken up by a mixed bag of videobloggers and artists excited by the idea of video specifically made for the net.

An immediate adopter and one of the most enthusiastic and prolific makers of Lumières was the Danish architect, educator and thinker, Thomas Wiesner, who operates in online video as Sam Renseiw and maintains a quirky and engaging site called Spacetwo: Patalab. Renseiw (as he prefers to be known in a video context) is a maker of numerous very singular small video works, which evince his keen interest in space and movement within spaces. (He teaches not only architecture but also a course for dancers involving approaches to conceptualising movement in space). I’m not sure Renseiw completely understands how original his work is. It is characterised by a joy in careful, quizzical looking (and a spontaneity in finding or being gifted subjects for such looking, assisted enormously by the continual development of more portable and discreet video cameras). It is, in terms of the formal art world deeply unfashionable. Personal and diaristic, it eschews the grand concept and extravagant and expensive execution and is all the better for this.

Renseiw has a profound sensitivity to space and to how people and objects move along variously restricted and open trajectories but he is mindful too of what the ‘actors’ in these found scenarios, set out to do and in fact achieve as human beings. The gap between aim and reality provides fertile ground for Renseiw’s dry and humane sense of humour, which is never far distant.

Significantly his prolific Lumière making (337 at the time of writing) sits side by side with longer (though still lapidary) works with music, editing and the other things the Lumière eschews.

Renseiw’s Lumières are characterised by a number of quite distinctive things. Something that unites them all is a quite extraordinarily heightened sensitivity to both colour and composition, which formal feature hits us forcefully in the moments even before we begin to decode any content or action. Formally striking too is the way in which a number of the pieces are composed so to as to allow for action in the near, middle and far distance, sometimes in different sectors of the frame, sometimes simultaneously in a kind of layered visual counterpoint and sometimes spread out temporally. My imputed intentionality here is somewhat problematic, though Renseiw confirmed to me that he shoots much more material than he uses and that he will select a particular minutes worth of material from longer sequences so on two counts there is a rudimentary (though nominally forbidden) editing process occurring. A quick comparison with Lumières by other film-makers will however confirm that Rensiew’s singular vision distinguishes each of his pieces from the off.

Other signatures are extremely low, oblique or occluded camera positions, into the fields of which parts of human bodies mysteriously intrude. This sounds clinical. Curiously it is the opposite. Redeeming it is a genial humour which allows the part to stand for the whole – we perforce imagine the entire human being whilst smiling at the V-effekt with which we are presented – for example a pas de deux for a pair of woman’s black leather boots (on the ends of beyond-the- frame legs) and the four paws of a black dog – randomness, clumsiness, near misses, narrow escapes and – we just know because we are human – purposeful activity. Human life, in short.

Another defining stamp is a musician’s sensitivity to rhythm and tempo – rhythm as manifested both as near metronomic regularity – someone’s gait, traffic flow, a hammer, for example, with either disruptions – slowings down, speedings up, pauses, stutterings – to that regular pattern, or polyrhythms created by other simultaneous independent near regularities and variations therefrom.

There are three loose categories into which Renseiw’s Lumière work could be said to fall (of course they’re by no means entirely mutually exclusive) – we’ll call them the loop-able, the documentary and the performative. The loop-ables are kin to the still photograph, are often of natural phenomena or repetitive but irregular human engendered activity where one could imagine the minute’s imaging infinitely, hypnotically extended – the flashing light patterns in Belisha Code for example. The documentary tag applies where the topic itself might be assumed to have some independent interest, for example the workers transporting away in a sling Copenhagen’s Little Mermaid for a trip to Shanghai’s 2010 expo in Speaking Voice or Michelle Obama’s motorcade in Rite of Passage. In what I’ve called the performative, richest of all in my view, an amazing amount of stuff happens. And everyday stuff happening and rendered vital by keen eye, framing and selection rather than something we might have known to look out for, is key. The differently distanced layers referred to earlier partition the frame physically or the piece temporally and unexpected things happen against and within them. We participate in these dynamically as viewers – we view this strange jigsaw world and complete it mentally; sketch a world beyond which is not simply our lived world but that world somehow leavened with Renseiw’s odd and warm sensibility.

I’ve written pretty glowingly about these Lumières – constrained, silent but surprisingly un-austere and you could well think that to add sound, music or both and several layers of these to boot might be over-egging it all somewhat. So one would think, but I have complimentary things yet to say about skill, tact, panache, flair and sensitivity and they are heading the way of Philip Sanderson, Renseiw’s musical/sound collaborator in the extended Lumière and Son project.

Renseiw’s Lumières are, I hope I’ve established, rich, dense, multi-layered but remarkably uncluttered works. A number of these pieces approach as closely as possibly the condition of music whilst remaining wholly without sound. It might seem superfluous or an act of hubris to add sound to them, the consequence of which could be to render leaden, stiff and fixed what is light, playful, complex and turns on a sixpence.

With the exception of a couple of near misses Philip Sanderson’s sound and music additions triumphantly avoid this trap and indeed deepen those rich and quicksilver qualities.

It’s important to note that what Sanderson contributes is all found or appropriated material – it’s possible he’s added original material in, I don’t know, but it’s not a significant chunk if he has – he certainly reworks much of it intensively, usually in the form of a mix of several layers of sound, some musical, some textual. (And we should note that Sanderson’s wit and deftness is literary as well as musical).

The deployment of sound gains enormously from Sanderson’s huge and eclectic range of knowledge, reference and enthusiasms. There’s a cooking metaphor in here – mixing the ingredients, finding just the right, perhaps almost imperceptibly present flavourings, knowing the qualities of things and how to combine them well…

Elsewhere I have asserted that the key feature of the most successful short form video work is a combination of intense poetic compression with a huge range of suggestion. I called this opening-out – a universe from a speck of dust. An ability to evoke the range of connectedness of many disparate things by well-chosen images, sounds, texts, whatever can pertain to moving image. Certainly Renseiw’s work has this in spades. Sanderson’s sound opens-out the movies still further. It adds, almost literally, an extra dimension, as if enabling new angles of view. It provides paths, bridges, vistas, tunnels, maps, balloons, telescopes, and sonar.

The guiding methodological principle seems to be a species of metonymy and one moreover which suggests an, in practice entirely non-existent, explanatory or illustrative dimension. The flashing beacons in Belisha Code are accompanied by a recording of a numbers station where one’s immediate impulse is to construct entirely absent meaning in the correspondence of the binary on-off of the four beacons and the German numbers from zero to nine heard on the soundtrack. Let’s be clear that this is not a criticism – a rigorous correspondence would be leaden – closed-in – but what we do have is a rich package of suggestion and affect. The correspondence that does exist is formal and temporal, between the flashes of the beacons and the articulation of the words and where the same sort of rickety polyrhythms that we’ve observed within the original Lumières themselves ensue.

Although comparison of some of Sanderson’s sources with their use in the pieces evidences, on occasion, some quite detailed cutting, mending and buffing-up there is an inescapable sense in his deployment of sound of the somewhat aristocratic tradition of the modestly dashed off. It’s partly his clearly extensive knowledge of his sources and his evident skill with a huge variety of genres but it’s also to do with a certain ambiguity in how the sounds are placed – not four square upon, but athwart the images, the sound often only fading or vanishing well after we’re into Renseiw’s end titles. Sometimes the sound is clearly not cut to shape in the way one might at first expect – an introduction, for example proper only to the original sound itself and not to any clear visual motivation might be left standing. The imperfections, noise, oddities and glitches contained within each block of appropriated sound intensify this sense of informality as does the slightly culinary air referred to previously. On the other hand, often enough to matter, the sound directly lines up in a spine tingling way with a particular action. It’s a master class in expressive ambiguity.

Renseiw – physical poetry, the occlusion, constraint. The careful choice of footage (variety and kind of motion within a narrowish range). Humanism: we don’t see faces, we don’t hear voices, we are amused but we recognise ourselves, youth and age &c.

Sanderson: The music found but could have been composed. The artfulness of placing it just thus. We will never know whether the way it ends with the action, the running off, taking place just after the repose of the final minor chord was deliberated or found. For me this placement implies a universe beyond the letterbox. It has a commonality with the treatment of time in many photographs and paintings – this is an instant, a fragment, but there was a before and an after.

Note that there are four beacons. The sound (a numbers station, one can almost track the archaeology of impulse!) draws on the numbers 0-9, in German. It’s worth noting there is no obvious mathematical mapping between the pattern of the beacons and the numbers but the character in sound of the numbers is close to that of the beacons in light. Suggestion, metonymy.

This forces our attention very strongly on that area of the screen, with the concomitant effect that when we force our attention away it is as if our eyes have been suddenly opened. There is a world out there.

There is a hint of the transcendent in the title – how is this realized? Unless we know Denmark it takes a few moments to realize we are on a train rather than a boat or plane – we are clued into this by the close objects we clearly pass at speed and the reflection of passengers and seating in the windows. One speculates that the sound track is comprised of two elements – one the rhythmic and metallic pulse which somehow rhymes with the passing object (a kind of pseudo-diegesis) and the second an (Open University?) lecture on relativity.

Here, not exactly metonymy but something more fragile, delicate chains of suggestion and subtle resonance. No argument (to see an argument in any of this would be to commit a category error) but a complex and suggestive …um…thing. One should also note that this piece (in both its silent and extended versions) is extremely beautiful.

Let’s talk about the sensibility and taste of the makers. Renseiw offers something simple, a kind of tour de force – we perceive it as such although given the fixed camera constraint any virtuosity belongs to the seagull.

A banal seasoning of music would involve simply the seven note modal motif which hails, I’m almost certain, from American popular song of the 70s big country type – Wichita Linesman, you know the sort of thing. (I checked with Sanderson –it’s Bobby Goldsboro’s Summer The First Time) By itself it would be too perfect, too parallel to the floating bird (it seems to give way to a crashing wave sound in its looped form; interestingly the Goldsboro video I found on YouTube begins with a shot of gliding seagulls). With too much parallelism nothing extra arises but Sanderson spices the mixture by the addition of dialogue from what sounds like an American film of the forties or early fifties. It disrupts the idyll but only so as to make us more aware of it. There is a kind of musical V-effekt here (which could have been so badly handled and so isn’t). This is its ‘meaning’ – these things! Here, now!

There is something of the dance about this. The music beautifully picks up both the nervous, sudden gestures of the cook but also suggests the process of cooking itself. The music has a funk component. One might say that it cooks.

Visually – the low angle, the fragmented view of the body, the person here and not here. The focus on that person which permits and invites its opposite, in particular the framing of the sky and trees. The rhyme between the black-booted two legs of the woman and the black four legs of the dog. Their pas de deux. The music here subordinate, properly so. Ambient sounds, on the one hand, with odd vocal snatches on top. The strangeness doesn’t demand our attention because we are so focused on the visual.

Until the last moments we simply hear a fitting (slightly arch) accompaniment to the skating – we surmise that it is intended to pastiche the kind of accompaniments used in professional skating. At the last moment we realize this is exactly what it is, as the commentator’s voice breaks through. There is also a ‘skate’, ‘friction’ or ‘traveling’ noise which exactly underpins the final move we see, just before the humour of the juxtaposed text, which continues after the movie has gone to black, strikes us: “Delightful, skating of the highest quality” delivered in classic plummy BBC tones…

A hugely rich piece: visually there are a number of layers – the far left street background where distant people and vehicles process. The game of Petanque: – the actual participants (although glimpsed corporeally only twice: fleetingly at the very end and as one set of typical Renseiw-y legs) and the balls themselves (and the metonymic link between these and the planets). Thirdly, the large shadows. (And the apparent size of each of these layers allows for very clear visual interaction). Sound – the ‘light’, jokey, playful music. The University Challenge soundtrack, here unusually clearly cut up – questions – astronomy; replies – painters. A risk for Sanderson, but one that works.

A little detective work indicates the level of detailed truffling about by Sanderson – part of the sound, the text, is grabbed from a YouTube video about French patisseries in London and cut up considerably – in particularly yielding the repeated incantation “cream cakes, tarts, macarons” the latter word in a considerably overheated French accent following the sloaney first three, to deeply comic effect. Comic maybe but, repeated, as in a dream; this mood is reinforced by a rather beautiful waltz time solo piano loop of the opening line of The Associates’ Party Fears Too. Here’s another piece where the visuals, here also dreamy and wistful, set in a looking glass Copenhagen (and the disjuncture between the London-location heavy narrative and the visuals is simply ignored, taken for granted, part of the deal), support quite a complex sound assemblage. Utterly haunting and quite difficult to say exactly why.

If one didn’t know it wasn’t one would surely assume this was carefully planned, and our knowledge it was not adds to our pleasure in it. Visually the rhyme between the woman and the near foreground statue is perfect – at one point she seems to mirror it exactly. Maybe she knows the area well and there is some unconscious mental echoing…we’ll never know. The other sharp visual pleasure is the smallness of the area of focussed distant activity, which again feels like a sort of directorial chutzpah, except, except…

Sanderson’s contribution is razor-sharp – the pseudo dialogue hits the mark precisely but doesn’t outstay it’s welcome – or at least there’s other stuff going on to detain us, not least the way the model’s preliminary warm-up shimmy becomes a perfect piece of minimal dance when set against the music.

Right of Passage/Speaking Voice

I wonder if when the content has it’s own ‘documentary’ interest, when the filming becomes a case of “Look at this remarkable thing not because of its intrinsic interest but because it happened”, the final result is somehow less engaging?

Again a dance related piece – the regular beat of the calling of the numbers one to eight sets up an aural grid against with which the implicit rhythms of the movement in, out and across frame interact in a sophisticated but subtle polyrhythm. Part two of the sound, with actual step instructions, ups the tension and the effect (especially the late entering ‘spinning’ man). Note how often in these pieces the sound fades out slightly later than the visuals, over Renseiw’s titles, thus emphasising its separate existence in an independent channel or dimension.

Beautiful found synthesis. Funny. Funny and truthful and touching.

The moving image is packed with incident at both different spatial levels and at different points in the piece. The Portsmouth Sinfonia version of Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy underpins like a grid, as with Square Dance but in a more complex way, the visual rhythms of the film. Enough coincidence of rhythm to feel planned, enough ‘pull outwards’ to feel open… Again humour… Why does the Portsmouth Sinfonia track, in particular, work so well – atmosphere? the conjuring of a sort of raggedy clockwork ? – can we imagine in its place a more conventional rendering of the Tchaikovsky? Yes, but…

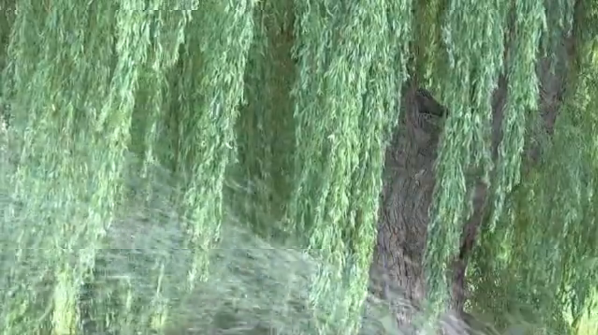

Prime example of Sanderson mind set – metonymy, suggestion – the trees are hair, the water appears exactly on cue (worked? Hmm – the audio appears to be cut to make the word ‘rinsing’ and the water jet coincide)

A one liner, but, given its place in the sequence, none the worse for it.

Brass band/Dancers.

*The pieces loosely divide into ones where either sound or vision predominate and some where they have equal roles.

* Not only does dance appear a couple of times explicitly as a subject but the spirit of dance pervades the project.

*The question of the success of individual pieces and of the sequence – a piece that seems less effective in isolation can well form an effective point of relaxation or reflection in the sequence as a whole…

*There are three pieces which, if one ‘re-removed’ the sound, would not strictly be Lumières – Check Out Art Fairs (speeded up), A Beauty Overblown (slowed down) & Sucked In (reversed). Sanderson performed the first two operations for reasons he felt the sound he used demanded. (To which one can only say: yes, this is right, a constraint is there for the sake of art, not art to be constrained.) Sucked In remains a mystery.

*The titles matter (note the re-titling of the composite works). They provide yet another dimension and illumination too.

*The prevailing tone is light, warm and playful. The darker side of life is largely absent, at least explicitly (though there are trails we could pick up to find it). Humour is everywhere. Only a philistine or fool would judge the work as a consequence to be less ambitious, significant or universal.