For its closing community gathering of the year, the Disruption Network Lab organised a conference to extend and connect its 2019 programme ‘The Art of Exposing Injustice’ – with social and cultural initiatives, fostering direct participation and enhancing engagement around the topics discussed throughout the year. Transparency International Deutschland, Syrian Archive, and Radical Networks are some of the organisations and communities that have taken part on DNL activities and were directly involved in this conference on November the 30th, entitled ‘Activation: Collective Strategies to Expose Injustice’ on anti-corruption, algorithmic discrimination, systems of power, and injustice – a culmination of the meet-up programme that ran parallel to the three conferences of 2019.

The day opened with the talk ‘Untangling Complexity: Working on Anti-Corruption from the International to the Local Level,’ a conversation with Max Heywood, global outreach and advocacy coordinator for Transparency International, and Stephan Ohme, lawyer and financial expert from Transparency International Deutschland.

In the conference ‘Dark Havens: Confronting Hidden Money & Power’ (April 2019) – DNL focused its work on offshore financial systems and global networks of international corruption involving not only secretive tax havens, but also financial institutions, systems of law, governments and corporations. On the occasion, DNL hosted discussions about the Panama Papers and other relevant leaks that exposed hundreds of cases involving tax evasion, through offshore regimes. With the contribution of whistleblowers and people involved in investigations, the panels unearthed how EU institutions turn a blind eye to billions of Euros worth of wealth that disappears, not always out of sight of local tax authorities, and on how – despite, the global outrage caused by investigations and leaks – the practice of billionaires and corporations stashing their cash in tax havens is still very common.

Introducing the talk ‘Untangling Complexity,’ Disruption Network community director Lieke Ploeger asked the two members of Transparency International and its local chapter Transparency International Deutschland to touch base after a year-long cooperation with the Lab, in which they have been substantiating how, in order to expose and defeat corruption, it is necessary to make complexity transparent and simple. With chapters in more than 100 countries and an international secretariat in Berlin, Transparency International works on anti-corruption at an international and local level through a participated global activity, which is the only effective way to untangle the complexity of the hidden mechanisms of international tax evasion and corruption.

Such crimes are very difficult to detect and, as Heywood explained, transparency is too often interpreted as simple availability of documents and information. It requires instead a higher degree of participation since documents and information must be made comprehensible, singularly and in their connections. In many cases, corruption and illegal financial activities are shielded behind technicalities and solid legal bases that make them hard to be uncovered. Within complicated administrative structures, among millions of documents and terabytes of files, an investigator is asked to find evidence of wrongdoings, corruption, or tax evasion. Most of the work is about the capability to put dots together, managing to combine data and metadata to define a hidden structure of power and corruption. Like in a big puzzle, all pieces are connected. But those pieces are often so many, that just a collective effort can allow scrutiny. That is why a law that allows transparency in Berlin, on estate properties and private funds, for example, might be able to help in a case of corruption somewhere else in the world. Exactly like in the financial systems, also in anti-corruption, nothing is just local and the cooperation of more actors is essential to achieve results.

The recent case of the Country-by-Country Reporting shows the situation in Europe. It was an initiative proposed in the ‘Action Plan for Fair and Efficient Corporate Taxation‘ by the European Commission in 2015. It aimed at amending the existing legislation to require multinational companies to publicly disclose their income tax in each EU member state they work in. Not many details are supposed to be disclosed and the proposal is limited only to companies with a turnover of at least €750 million, to know how much profit they generate and how much tax they pay in each of the 28 countries. However, many are still reluctant to agree, especially those favouring the profit-shifting within the EU. Some, including Germany, worry that revealing companies’ tax and profit information publicly will give a competitive advantage to companies outside Europe that don’t have to report such information. Twelve countries voted against the new rules, all member states with low-tax environments helping to shelter the profits of the world’s biggest companies. Luxembourg is one of them. According to the International Monetary Fund – through its 600,000 citizens – the country hosts as much foreign direct investment as the USA, raising the suspicion that most of this flow goes to “empty corporate shells” designed to reduce tax liabilities in other EU countries.

Moreover, in every EU country, there are voices from the industrial establishment against this proposal. In Germany, the Foundation of Family Businesses, which despite its name guarantees the interests of big companies, as Ohme remarked, claims that enterprises are already subject to increasingly stronger social control through the continuously growing number of disclosure requirements. It complains about what is considered the negative consequences of public Country-by-Country Reporting for their businesses, stating that member states should deny their consent as it would considerably damage companies’ competitiveness, and turn the EU into a nanny state. But, apart from the expectations and the lobbying activities of the industrial élite, European citizens want multinational corporations to pay fair taxes on EU soil where the money is generated. The current fiscal regimes increase disparities, allow profit-shifting and bank secrecy. The result is that most of the fiscal burden push against less mobile tax-payers, retirees, employees, and consumers, whilst corporations and billionaires get away with their misconducts.

Transparency International encourages citizens all over the globe to carry on asking for accountability and improvements in their financial and fiscal systems without giving up. In 1997, the German government made bribes paid to foreign officials by German companies tax-deductible, and until February 1999 German companies were allowed to bribe in order to do business across the border, which was common practice, particularly in Asia and Latin America since at least the early 70s. But things have changed. Ohme is aware of the many daily scandals related to corruption and tax evasion: for this reason he considers the work of Transparency International necessary. However, he invited his audience not to describe it as a radical organisation, but as an independent one that operates on the basis of research and objective investigations.

In the last months of 2019 in Germany, the so-called Cum-Ex scandal caught the attention of international news outlets as investigators discovered a trading scheme exploiting a tax loophole on dividend payments within the German tax code. Authorities allege bankers helped investors reap billions of euros in illegitimate tax refunds, as Cum-Ex deals involved a trader borrowing a block of shares to bet against them, and then selling them on to another investor. In the end, parties on both sides of the trade could claim a refund of withholding taxes paid on the dividend, even though prosecutors contend that only a single rebate was actually due. The loophole was closed in 2012, but investigators think that in the meantime companies like Freshfields advised many banks and other participants in the financial markets to illegally profit from it.

As both Heywood and Ohme stressed, we need measures that guarantee open access to relevant information, such as the beneficial owners of assets which are held by entities, and arrangements like shell companies and trusts – that is to say, the info about individuals who ultimately control or profit from a company or estate. Experts indicate that registers of beneficial owners help authorities prosecute criminals, recover stolen assets, and deter new ones; they make it harder to hide connections to illicit flows of capital out of a national budget.

Referring to the case of the last package of measures regarding money laundering and financial transparency, under approval by the German parliament, Ohme showed a shy appreciation for the improvements, as real estate agents, gold merchants, and auction houses will be subject to tighter regulations in the future. Lawmakers complained that the US embassy and Apple tried to quash part of these new rules and that during the parliamentary debate they sought to intervene with the Chancellery to prevent a section of the law from being adopted. The attempt was related to a regulation which forces digital platforms to open their interfaces for payment services and apps, such as the payment platform ApplePay, but it did not land. Apple’s behaviour is a sign of the continuous interferences of the interests at stake when these topics are discussed.

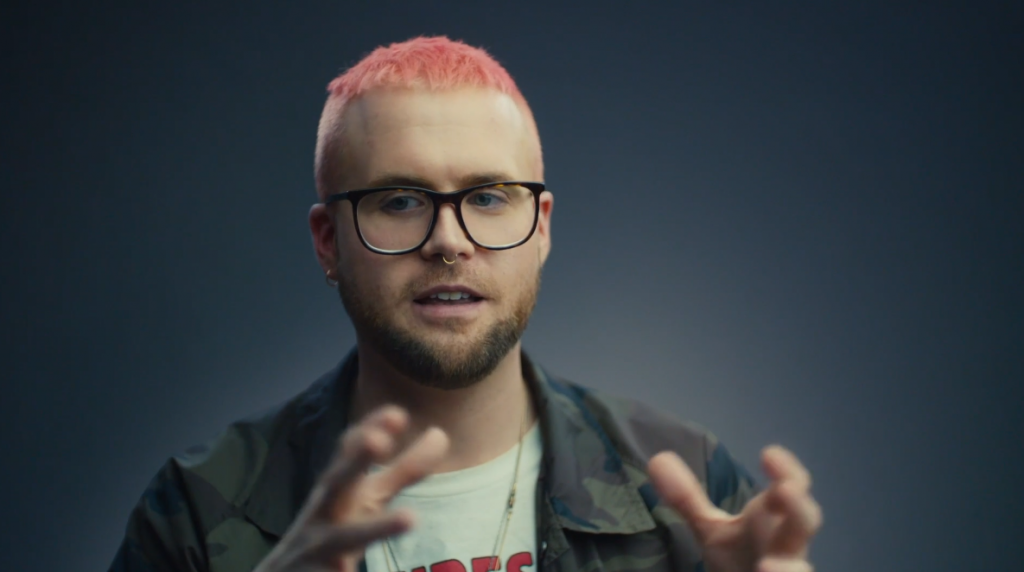

At the end of the first talk, DNL hosted a screening of the documentary ‘Pink Hair Whistleblower’ by Marc Silver. It is an interview with Christopher Wylie, who worked for the British consulting firm Cambridge Analytica, who revealed how it was built as a system that could profile individual US voters in 2014, to target them with personalised political advertisements and influence the results of the elections. At the time, the company was owned by the hedge fund billionaire Robert Mercer and headed by Donald Trump’s key advisor, and architect of a far-right network of political influence, Steve Bannon.

The DNL discussed this subject widely within the conference ‘Hate News: Manipulators, Trolls & Influencers’ (May 2018), trying to define the ways of pervasive, hyper-individualized, corporate-based, and illegal harvesting of personal data – at times developed in partnership with governments – through smartphones, computers, virtual assistants, social media, and online platforms, which could inform almost every aspect of social and political interactions.

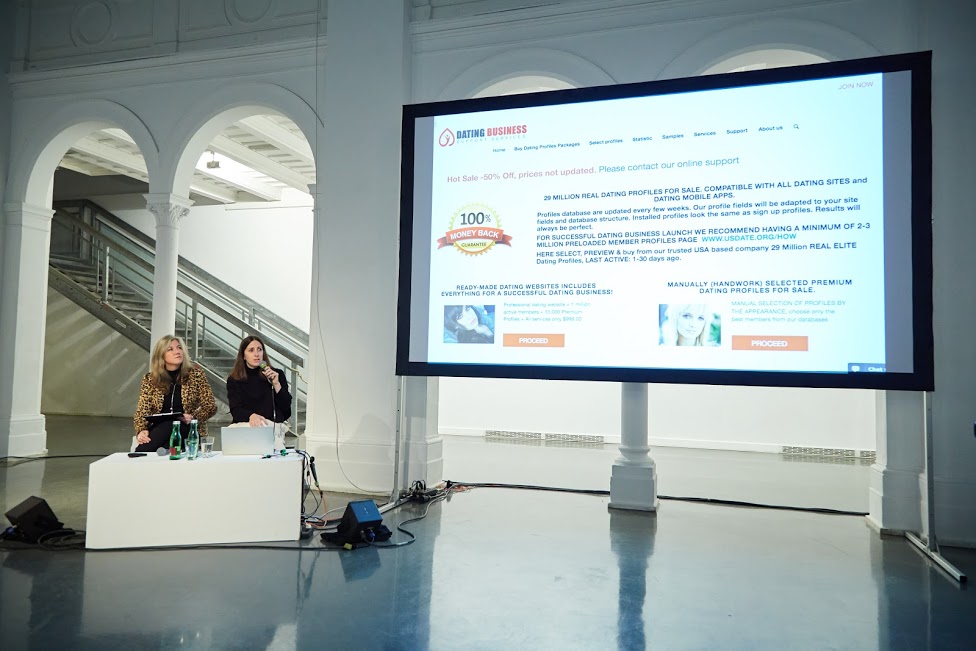

With the overall theme ‘AI Traps: Automating Discrimination‘ (June 2019), DNL sought to define how artificial intelligence and algorithms reinforce prejudices and biases in society. These same issues were raised in the Activation conference, in the talk ‘An Autopsy of Online Love, Labour, Surveillance and Electricity/Energy.’ Joana Moll, artist and researcher, in conversation with DNL founder Tatiana Bazzichelli, presented her latest projects ’The Dating Brokers’ and ‘The Hidden Life of an Amazon User,’ on the hidden side of IT-interface and data harvesting.

The artist’s work moves from the challenges of the so-called networked society to a critique of social and economic practices of exploitation, which focuses on what stands behind the interface of technology and IT services, giving a visual representation of what is hidden. The fact that users do not see what happens behind the online services they use has weakened the ability that individuals and collectives have to define and protect their privacy and self-determination, getting stuck in traps built to get the best out of their conscious or unconscious contribution. Moll explains that, although most people’s daily transactions are carried out through electronic devices, we know very little of the activities that come with and beyond the interface we see and interact with. We do not know how the machine is built, and we are mostly not in control of its activities.

Her project ‘The Dating Brokers’ focuses on the current practices in the global online dating ecosystem, which are crucial to its business model but mostly opaque to its users. In 2017, Moll purchased 1 million online dating profiles from the website USDate, a US company that buys and sells profiles from all over the world. For €136, she obtained almost 5 million pictures, usernames, email addresses, details about gender, age, nationality, and personal information such as sexual orientation, private interests, profession, physical characteristics, and personality. Analysing few profiles and looking for matches online, the artist was able to define a vast network of companies and dating platforms capitalising on private information without the consent of their users. The project is a warning about the dangers of placing blind faith in big companies and raises alarming ethical and legal questions which urgently need to be addressed, as dating profiles contain intimate information on users and the exploitation and misuse of this data can have dramatic effects on their lives.

With the ongoing project ‘The Hidden Life of an Amazon User,’ Moll attempts to define the hidden side of interfaces. The artist documented what happens in the background during a simple order on the platform Amazon. Purchasing the book ‘The Life, Lessons & Rules for Success’ by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos her computer was loaded with so many scripts and requests, that she could trace almost 9,000 pages of lines of code as a result of the order and more than 87 megabytes of data running in the background of the interface. A large part of the scripts are JavaScript files, that can theoretically be employed to collect information, but it is not possible to have any idea of what each of these commands meant.

With this project, Moll describes the hidden aspects of a business model built on the monitoring and profiling of customers that encourages them to share more details, spend more time online, and make more purchases. Amazon and many other companies aggressively exploit their users as a core part of their marketing activity. Whilst buying something, users provide clicks and data for free and guarantee free labour, whose energy costs are not on the companies’ bills. Customers navigate through the user interface, as content and windows constantly load into the browser to enable interactions and record user’s activities. Every single click is tracked and monetized by Amazon, and the company can freely exploit external free resources, making a profit out of them.

The artist warns that these hidden activities of surveillance and profiling are constantly contributing to the release of CO2. This due to fact that a massive amount of energy is required to load the scripts on the users’ machine. Moll followed just the basic steps necessary to get to the end of the online order and buy the book. More clicks could obviously generate much more background activity. A further environmental cost that customers of these platforms cannot decide to stop. This aspect shall be considered for its broader and long term implications too. Scientists predict that by 2025 the information and communications technology sector might use 20 per cent of all the world’s electricity, and consequently cause up to 5.5 per cent of global carbon emissions.

Moll concluded by saying we can hope that more and more individuals will decide to avoid certain online services and live in a more sustainable way. But, trends show how a vast majority of people using these platforms and online services, are harmful, because of their hidden mechanisms, affecting people’s lives, causing environmental and socio-economic consequences. Moll suggested that these topics should be approached at the community level to find political solutions and countermeasures.

The 17th conference of the Disruption Network Lab, ‘Citizens of Evidence’ (September 2019,) was meant to explore the investigative impact of grassroots communities and citizens engaged to expose injustice, corruption, and power asymmetries. Citizen investigations use publicly available data and sources to autonomously verify facts. More and more often ordinary people and journalists work together to provide a counter-narrative to the deliberate disinformation spread by news outlets of political influence, corporations, and dark money think-tanks. In this Activation conference, in a talk moderated by Nada Bakr, the DNL project and community manager, Hadi Al Khatib, founder and Director of ’The Syrian Archive’, and artist and filmmaker Jasmina Metwaly, altogether focused on the role of open archives in the collaborative production of social justice.

The Panel ‘Archives of Evidence: Archives as Collective Memory and Source of Evidence’ opened with Jasmina Metwaly, member of Mosireen, a media activist collective that came together to document and spread images of the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. During and after the revolution, the group produced and published over 250 videos online, focusing on street politics, state violence, and labour rights; reaching millions of viewers on YouTube and other platforms. Mosireen, who in Arabic recalls a pun of the words “Egypt” and “Determination” which could be translated as “we are determined,” has been working since its birth on collective strategies to allow participation and channel the energies and pulses of the 2011 protesters into a constructive discourse necessary to keep on fighting. The Mosireen activists organised street screenings, educational workshops, production facilities, and campaigns to raise awareness on the importance of archives in the collaborative production of social justice.

In January 2011, the wind of the Tunisian Revolution reached Egyptians, who gathered in the streets to overthrow the dictatorial system. In the central Tahrir Square in Cairo, for more than three weeks, people had been occupying public spaces in a determined and peaceful protest to get social and political change in the sense of democracy and human rights enhancement.

For 5 years, since 2013, the collective has put together the platform ‘858: An Archive of Resistance’ – an archive containing 858 hours of video material from 2011, where footage is collected, annotated, and cross-indexed to be consulted. It was released on 16th January 2018, seven years after the Egyptian protests began. The material is time-stamped and published without linear narrative, and it is hosted on Pandora, an open-source tool accessible to everybody.

The documentation gives a vivid representation of the events. There are historical moments recorded at the same time from different perspectives by dozens of different cameras; there are videos of people expressing their hopes and dreams whilst occupying the square or demonstrating; there is footage of human rights violations and video sequences of military attacks on demonstrators.

In the last six years, the narrative about the 2011 Egyptian revolution has been polluted by revisionisms, mostly propaganda for the government and other parties for the purposes of appropriation. In the meantime, Mosireen was working on the original videos from the revolution, conscious of the increasing urgency of such a task. Memory is subversive and can become a tool of resistance, as the archive preserves the voices of those who were on the streets animating those historical days.

Thousands of different points of views united compose a collection of visual evidence that can play a role in preserving a memory of events. The archive is studied inside universities and several videos have been used for research on the types of weapons used by the military and the police. But what is important is that people who took part in the revolution are thankful for its existence. The archive appears as one of the available strategies to preserve people’s own narratives of the revolution and its memories, making it impermeable to manipulations. In those days and in the following months, Egypt’s public spaces were places of political ferment, cultural vitality, and action for citizens and activists. The masses were filled with creativity and rebellion. But that identity is at risk to disappear. That kind of participation and of filming is not possible anymore; public spaces are besieged. The archive cannot be just about preserving and inspiring. The collective is now looking for more videos and is determined to carry on its work of providing a counter-narrative on Egyptian domestic and international affairs, despite tightened surveillance, censorship, and hundreds of websites blocked by the government.

There are many initiatives aiming to resist forgetting facts and silencing independent voices. In 2019, the Disruption Network Lab worked on this with Hadi Al Khatib, founder and director of ‘The Syrian Archive,’ who intervened in this panel within the Activation conference. Since 2011, Al Khatib has been working on collecting, verifying, and investigating citizen-generated data as evidence of human rights violations committed by all sides in the Syrian conflict. The Syrian Archive is an open-source platform that collects, curates, and verifies visual documentation of human rights violations in Syria – preserving data as a digital memory. The archive is a means to establish a verified database of facts and represents a tool to collect evidence and objective information to put an order within the ecosystem of misinformation and the injustices of the Syrian conflict. It also includes a database of metadata information to contextualise videos, audios, pictures, and documents.

Such a project can play a central role in defining responsibilities, violations, and misconducts, and could contribute to eventual post-conflict juridical processes since the archive’s structure and methodology is supposed to meet international standards. The Syrian conflict is a bloody reality involving international actors and interests which is far from being over. International reports in 2019 indicate at least 871 attacks on vital civilian facilities with the deaths of 3,364 civilians, where one in four were children.

The platform makes sure that journalists and lawyers are able to use the verified data for their investigations and criminal case building. The work on the videos is based on meticulous attention to details, and comparisons with official sources and publicly available materials such as photos, footage, and press releases disseminated online.

The Syrian activist and archivist explained that a lot of important documents could be found on external platforms, like YouTube, that censor and erase content using AI under pressures to remove “extremist content,” purging vital human rights evidence. Social media has been recently criticized for acting too slowly when killers live-stream mass shootings, or when they allow extremist propaganda within their platforms.

DNL already focused on the consequences of automated removal, which in 2017 deleted 10 per cent of the archives documenting violence in Syria, as artificial intelligence detects and removes content – but an automated filter can’t tell the difference between ISIS propaganda and a video documenting government atrocities. The Google-owned company has already erased 200,000 videos with documental and historical relevance. In countries at war, the evidence captured on smartphones can provide a path to justice, but AI systems often mark them as inadequate violent content which consequently erases them.

Al Khatib launched a campaign to warn platforms to fix and improve their content moderation systems used to police extremist content, and to consider when they define their measures to fight misinformation and crimes, aspects like the preservation of the common memory on relevant events. Twitter, for example, has just announced a plan to remove accounts which have been inactive for six months or longer. As Al Khatib explains, this could result in a significant loss to the memory of the Syrian conflict and of other war zones, and cause the loss of evidence that could be used in justice and accountability processes. There are users who have died, are detained, or have lost access to their accounts on which they used to share relevant documents and testimonies.

In the last year, the Syrian Archive platform was replicated for Yemen and Sudan to support human rights advocates and citizen journalists in their efforts to document human rights violations, developing new tools to increase the quality of political activism, future prosecutions, human rights reporting and research. In addition to this, the Syrian Archive often organises workshops to present its research and analyses, such as the one in October within the Disruption Network Lab community programme.

The DNL often focuses on how new technologies can advance or restrict human rights, sometimes offering both possibilities at once. For example, free open technologies can significantly enhance freedom of expression by opening up communication options; they can assist vulnerable groups by enabling new ways of documenting and communicating human rights abuses. At the same time, hate speech can be more readily disseminated, technologies for surveillance purposes are employed without appropriate safeguards and impinge unreasonably on the privacy of individuals; infrastructures and online platforms can be controlled to chase and discredit minorities and free speakers. The last panel discussion closing the conference was entitled ‘Algorithmic Bias: AI Traps and Possible Escapes’, moderated by Ruth Catlow, who took the floor to introduce the two speakers and asked them to debate effective ways to define this issue and discuss possible solutions.

Ruth Catlow is co-founder and co-artistic director of Furtherfield, an art gallery in London’s Finsbury Park – home for artworks, labs, and debates based on playful collaborative art research experiences, always across distances and differences. Furtherfield diversifies the people involved in shaping emerging technologies through an arts-led approach, always looking at ways to disrupt network power of technology and culture, to engage with the urgent debates of our time and make these debates accessible, open, and participated. One of its latest projects focused on algorithmic food justice, environmental degradation, and species decline. Exploring how new algorithmic technologies could be used to create a fairer and more sustainable food system, Furtherfield worked on solutions in which culture comes before structures, and human organisation and human needs – or the needs of other living beings and living systems – are at the heart of design for technological systems.

As Catlow recalled, in the conference ‘AI Traps: Automating Discrimination’ (June 2019), the Disruption Network Lab focused on the possible countermeasures to the AI-informed decision-making potential for racial bias and reinforced through AI decision-making tools. It was an inspiring and stimulating event on inclusion, education, and diversity in tech, highlighting how algorithms are not neutral and unbiased. On the contrary, they often reflect, reinforce, and automate the current and historical biases and inequalities of society, such as social, racial, and gender prejudices. The panel within the Activation conference framed these issues in the context of the work by the speakers, Caroline Sinders and Sarah Grant.

Sinders is a machine learning design researcher and artist. In her work, she focuses on the intersections of natural language processing, artificial intelligence, abuse, online harassment, and politics in digital and conversational spaces. She presented her last study on the Intersectional Feminist AI, focusing on labour and automated computer operations.

Quoting Hyman (2017), Sinders argued that the world is going through what some are calling a Second Machine Age, in which the re-organisation of people matters as much as, if not more than, the new machines. Employees receiving a regular wage or salary have begun to disappear, replaced by independent contractors and freelancers; remuneration is calculated on the basis of time worked, output, or piecework, and paid to employees for hours worked. Labour and social rights conquered with hard, bloody fights in the last two centuries seem to be irrelevant. More and more tasks are operated through AI, which plays a big role in the revenues of big corporations. But still, machine abilities are possible just with the fundamental contribution of human work.

Sinders begins her analyses considering that human labour has become hidden inside of automation, but is still integral to that. The training of machines is a process in which human hands touch almost every part of the pipeline, making decisions. However, people who train data models are underpaid and unseen inside of this process. As Thomas Thwaites’ toaster project, a critical design project in which the artist built a commercial toaster from scratch – melting iron and building circuits and creating a new plastic shell – Sinders analyses the Artificial Intelligence economy under the lens of feminist, intersectionalism, to define how and to which extent it is possible to create an AI that respects in all its steps the principles of non-exploitation, non-bias, and non-discrimination.

Her research considers the ‘Mechanical Turks’ model, in which machines masquerade as a fully automated robot but are operated by a human. Mechanical Turk is actually a platform run by Amazon, where people execute computer-like tasks for a few cents, synonymous with low-paid digital piecework. A recent research analysed nearly 4 million tasks on Mechanical Turk performed by almost 3,000 workers found that those workers earned a median wage of about $2 an hour, whilst only 4% of workers on Mechanical Turk earned more than $7,25 an hour. Since 2005 this platform has flourished. Mechanical Turks are used to train AI systems online. Even though it is mostly systematised factory jobs, this labour falls under the gig economy, so that people employed as Mechanical Turks are considered gig workers, who have no paid breaks, holidays, and guaranteed minimum wage.

Sinder concluded that an ethical, equitable, and feminist environment is not achievable within a process based on the competition among slave labourers that discourages unions, pays a few cents per repetitive task and creates nameless and hidden labour. Such a process shall be thoughtful and critical in order to guarantee the basis for equity; it must be open to feedback and interpretation, created for communities and as a reflection of those communities. To create a feminist AI, it is necessary to define labour, data collection, and data training systems, not just by asking how the algorithm was made, but investigating and questioning them from an ethical standpoint, for all steps of the pipeline.

In her talk Grant, founder of Radical Networks, a community event and art festival for critical investigations and creative experiments around networking technology, described the three main planes online users interact with, where injustices and disenfranchisement can occur.

The first one is the control plane, which refers to internet protocols. It is the plumbing, the infrastructure. The protocol is basically a set of rules which governs how two devices communicate with each other. It is not just a technical aspect, because a protocol is a political action which basically involves exerting control over a group of people. It can also mean making decisions for the benefit of a specific group of people, so the question is our protocols but our protocols political.

The Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is an open standards organisation, which develops and promotes voluntary Internet standards, in particular, the standards that comprise the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP). It has no formal membership roster and all participants and managers are volunteers, though their activity within the organisation is often funded by their employers or sponsors. The IETF was initially supported by the US government, and since 1993 has been operating as a standards-development function under the international membership-based non-profit organisation Internet Society. The IETF is controlled by the Internet and Engineering Steering Group (IESG), a body that provides final technical review of the Internet standards and manages the day-to-day activity of the IETF, setting the standards and best practices for how to develop protocols. It receives appeals of the decisions of the working groups and makes the decision to progress documents in the standards track. As Grant explained, many of its members are currently employed for major corporations such as Google, Nokia, Cisco, Mozilla. Though they serve as individuals, this issues a conflict of interests and mines independence and autonomy. The founder of Radical Networks is pessimistic about the capability of for-profit companies to be trusted on these aspects.

The second plane is the user plane, where we find the users’ experience and the interface. Here two aspects come into play: the UX design (user experience design), and the UI (user interface design). UX is the presumed interaction model which defines the process a person will experience when using a product or a website, while the UI is the actual interface, the buttons, and different fields we see online. UX and UI are supposed to serve the end-user, but it is often not like this. The interface is actually optimized for getting users to act online in ways which are not in their best interest; the internet is full of so-called dark patterns designed to mislead or trick users to do things that they might not want.

These dark patterns are part of the weaponised design dominating the web, which wilfully allows for harm of users and is implemented by designers who are not aware of or concerned about the politics of digital infrastructure, often considering their work to be apolitical and just technical. In this sense, they think they can keep design for designers only, shutting out all the other components that constitute society and this is itself a political choice. Moreover, when we consider the relation between technology and aspects like privacy, self-determination, and freedom of expression we need to think of the international human rights framework, which was built to ensure that – as society changes – the fundamental dignity of individuals remain essential. In time, the framework has demonstrated to be plastically adaptable to changing external events and we are now asked to apply the existing standards to address the technological challenges that confront us. However, it is up to individual developers to decide how to implement protocols and software, for example, considering human rights standards by design, and such choices have a political connotation.

The third level is the access plane which is what controls how users actually get online. Here, Grant used Project loon as an example to describe the importance of owning the infrastructure. Project loon by Google is an activity of the Loon LLC, an Alphabet subsidiary working on providing Internet access to rural and remote areas, bringing connectivity and coverage after natural disasters with internet-beaming balloons. As the panellist explained, it is an altruistic gesture for vulnerable populations, but companies like Google and Facebook respond to the logic of profit and we know that controlling the connectivity of large groups of populations provide power and opportunities to make a profit. Corporations with data and profilisation at the core of their business models have come to dominate the markets; many see with suspicion the desire of big companies to provide Internet to those four billions of people that at the moment are not online.

As Catlow warned, we are running the risk that the Internet becomes equal to Facebook and Google. Whilst we need communities able to develop new skills and build infrastructures that are autonomous, like the wireless mesh networks that are designed so that small devices called ‘nodes’ – commonly placed on top of buildings or in windows – can send and receive data and a WIFI signal to one another without an Internet connection. The largest and oldest wireless mesh network is the Athens Wireless Metropolitan Network, or A.W.M.N., in Greece, but we also have other successful examples in Barcelona (Guifi.net) and Berlin (Freifunk Berlin). The goal is not just counterbalancing superpowers of telecommunications and corporations, but building consciousness, participation, and tools of resistance too.

The Activation conference gathered in the Berliner Künstlerhaus Bethanien, the community around the Disruption Network Lab, to share collective approaches and tools for activating social, political, and cultural change. It was a moment to meet collectives and individuals working on alternative ways of intervening in the social dynamics and discover ways to connect networks and activities to disrupt systems of control and injustice. Curated by Lieke Ploeger and Nada Bakr, this conference developed a shared vision grounded firmly in the belief that by embracing participation and supporting the independent work of open platforms as a tool to foster participation, social, economic, cultural, and environmental transparency, citizens around the world have enormous potential to implement justice and political change, to ensure inclusive, more sustainable and equitable societies, and more opportunities for all. To achieve this, it is necessary to strengthen the many existing initiatives within international networks, enlarging the cooperation of collectives and realities engaged on these challenges, to share experiences and good practices.

Information about the 18th Disruption Network Lab Conference, its speakers, and topics are available online:

https://www.disruptionlab.org/activation

To follow the Disruption Network Lab, sign up for its newsletter and get information about conferences, ongoing research, and latest projects. The next event is planned for March 2020.

The Disruption Network Lab is also on Twitter and Facebook.

All images courtesy of Disruption Network Lab

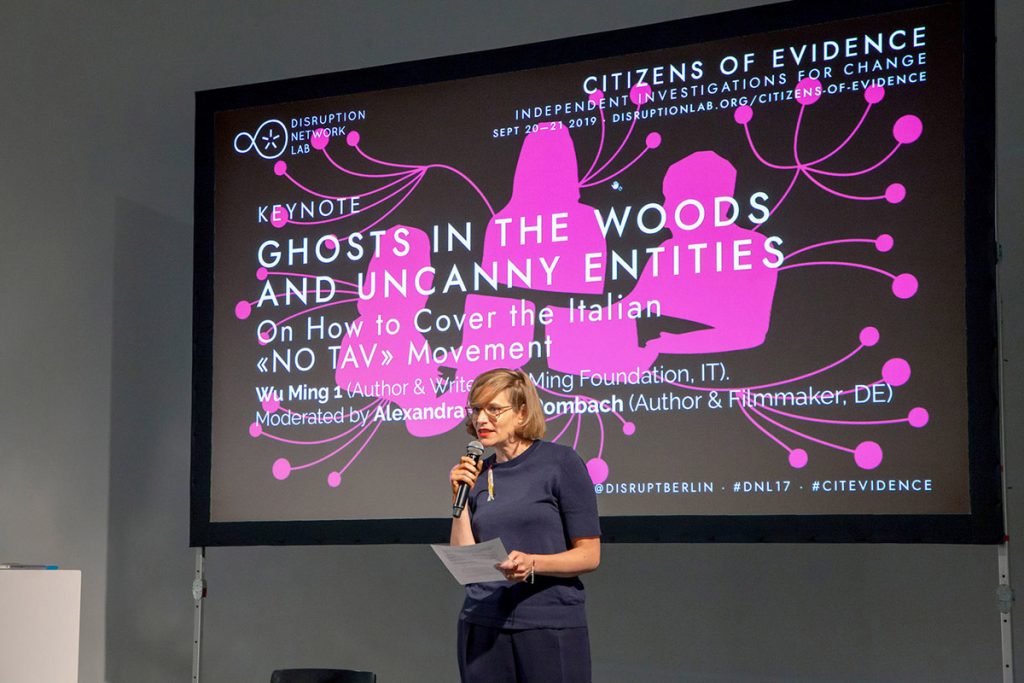

On the 20th of September, Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger opened the 17th conference of the Disruption Network Lab with CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE to explore the investigative impact of grassroots communities and citizens engaged to expose injustice, corruption, and power asymmetries.

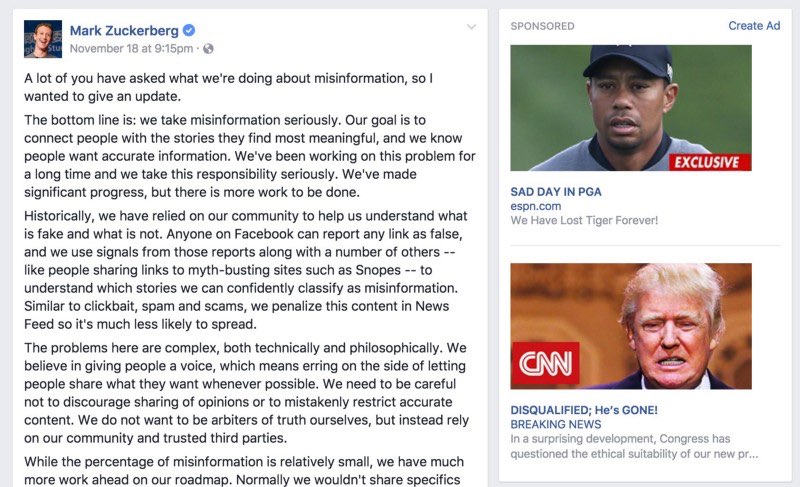

Citizen investigations use publicly available data and sources to autonomously verify facts. More and more often ordinary people and journalists work together to provide a counter-narrative to the deliberate disinformation spread by news outlets of political influence, corporations, and dark money think-tanks. However, journalists and citizens reporting on matters in the public interest are targeted because of the role they play in ensuring an informed society. The work of independent investigation is often delegitimised by public authorities and denigrated in a wave of generalisations against ‘the elites’ and media objectivity, actually designed to undermine independent information and stifle criticism. It appears to be a global process that aims at blurring progressively the boundary between what is fake and what is real, growing to such a level that traditional mainstream media and governments seem incapable of protecting society from a tide of disinformation.

An increasingly Orwellian campaign for the purpose discredit upon them has been built for years against citizens and activists opposing the project of a controversial high-speed rail line for freight trains between Italy and France, which is considered useless and harmful. The Disruption Network Lab conference opened with the keynote GHOSTS IN THE WOODS AND UNCANNY ENTITIES: On How to Cover the Italian «NO TAV» Movement by Wu Ming 1, who spent three years among the people of the Susa Valley opposing this mega-infrastructural project.

As the moderator, author, and filmmaker Alexandra Weltz-Rombach explained, Wu Ming is a pseudonym for a group of Italian authors formed in Bologna after the experience of the Luther Blissett project. For almost 20 years the literary collective has been writing essays, meta-historical novels, and creative narrative, using often the techniques of investigative journalism. Today it is widely appreciated for its capability to deconstruct and analyse complex aspects of social and political life, challenging long-existing paradigms and traditions and synthesizing the views of different minds, to build an alternative narration on facts, inspiring unconventional critical process. Wu Ming 1 explored the Susa Valley and the woods occupied by police and wire fences, experiencing the struggle of a community in its territories, to write a history-as-novel take on the most enduring and radical environmental protest in contemporary Italy, known as No-TAV (TAV stands for Treno Alta Velocità – High Speed Train). To do so, he walked, mapped the territory, and ‘evoked ghosts’. The history of a country can be described by the history of its borders and the Susa Valley is a borderland in the mountains. Probably where Hannibal walked with his army to cross the Alps, since the early 90s it has been projected another huge tunnel inside the mountains, in a long-standing tradition of railroad-tunnels built sacrificing lives and health.

To understand the No-TAV struggle we can go back in time. To when the TAV-railway was first projected, and contextually the opposition of local communities started. But also, back in time to all the conflicts that have been fought on these mountains, which are “full of ghosts” as the author said. Wu Ming 1 explained that in literature and popular tradition, a ghost appears when there is an unresolved story, a wasted life that ended badly. Borderlands are the places where the most of ghosts are to be found. In the Susa Valley, ghosts are suppressed memories of wars and of social conflicts that shaped the territory.

Wu Ming published several works on environmental and climatic issues and wrote a lot about mountains too. Almost 78% of Italian territory is covered by mountains or hills. Their iconic representation has been at time twisted by nationalism, militarism and machismo. The Alps were “sacred borders of the fatherland” – nature to conquer, a symbol of virility and power in fascist propaganda. Today those mountains are an obstacle to economic growth; a growth that might put at risk the whole Susa Valley. Thus, instead of tackling legitimate concerns, project Stakeholders have been seeking for 20 years to delegitimize those leveling the charges against the high-speed railway, despite the masses of evidence to support their claims, using intimidation and violence against them. But the no-TAV collectives’ claims have always been proven to be right, and the project has been declining in size over time. However, the fight within the Valley is still on and the TAV-project is far from being archived.

The panel on the first day, EXPOSING ABUSES: Citizens Recording Human Rights Violations from the US to The Gambia, introduced by Michael Hornsby of Transparency International, opened with a presentation by Melissa Segura, journalist of BuzzFeed News from the US. She documented allegations proving that the Chicago police officer Reynaldo Guevara had framed dozens of innocent people for murder. The reporter put a light on forgotten judiciary cases, giving voice to families and communities affected by injustices, hit by a profound brokenness that she experienced herself when her nephew was framed and arrested years before.

A group of black and Latino mothers, aunts, and sisters knew that their beloved were innocent, but no officials wanted to take up their cause. Segura met these women after they had been fighting for decades in search of justice. They began when the journalist was at her elementary school: “at the time they had already gathered in a team, collecting data and writing spreadsheets on Lotus” she recalled. They had no chance to be heard, no PR, no lobby, no support from media were available to them. Segura realized soon that the story she had to cover wasn´t just the conviction of a 19-year-old-boy sentenced in 1999 with 110 years of prison for a murder he did not commit. It was also about the community of women that were fighting for justice, it was about their lives.

She learnt soon that her sources were able to cover their own stories much better than how she could, showing her new paths to the truth. The journalist dedicated time to building a trusting relationship with them, giving full reassurance that their story would be fairly reported. After an intense three-year investigation, she succeeded in wearing down a key witness to testify, cracking the wall of impunity. This process, she said, “did not expose the harm of people, but tried to connect to it.”

Reynaldo Guevara has been beating up people, framing them, extorting false confessions and false witnesses for years. Since publishing Segura’s articles, seven innocent men have been freed, and dozens more convictions are under review.

In the context of the major movements that draw attention on issues such as injustice and police violence targeting specific communities and minorities in the US, policy and data analyst Samuel Sinyangwe decided to join the work of justice activist groups formed after the 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. He is now part of the Police Scorecard project, and of the Campaign Zero independent platform he co-founded, designed to facilitate and guarantee the collection of data on these violations. Sinyangwe explained that, as of today, the US government has implemented neither collections of data on police misconducts, violence and killings, nor public database of disciplined police officers. In his view, US law enforcement agencies have failed to provide even basic information about the lives they have taken, in a country where at least three people are killed by police every day and black people are 3 times more probable to end up victims of brutal use of force by the police.

The independent observatory built by Sinyangwe seems to be quite effective. It is described as the most comprehensive accounting of people killed by police since 2013 in the US. A report from the US Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that approximately 1,200 people were killed by police between June 2015 and May 2016. The database identified 1.179 people killed by police over this same time period. These estimates suggest that it was able to capture 98% of the total number of police killings that occurred. Sinyangwe hopes these data will be used to provide greater transparency and accountability for police departments as part of the ongoing campaign to end police violence in black and Latino communities, leading to a change of policies.

With data able to map the situation in the US, it has also been possible to make comparisons and drew analyses. The Campaign Zero researches show that there is a whole false narrative about criminality rates, based on numbers that just mirror a system based on different federal policies regarding police forces, and that levels of violent crime in US cities do not determine rates of police violence.

According to data, cities with the same density of population have very different rates of violence, and very different rules regulating the activity of police agents. Starting from this, Sinyangwe and his team decided to look for different policy documents from different police department. These policies determine how and when a local policeman is authorized to use force. With a closer look, the Campaign Zero team could easily determine that there is no federal standard. Some documents live a grey area, others discourage the use of force, and particularly of deadly force, limiting it to the most dangerous scenarios after all lesser means of use of force have failed. Some seem to openly encourage it instead.

The group listed eight types of restrictions in the use of force to be found in these policies, consisting of escalators that aim at excluding, as far as possible, the use of violence. Comparisons show that a combination of these restrictions, when put in place, can produce a large reduction in police violence. Policies combining restrictions predicted indeed significantly lower rate of deathly force.

Data about unarmed people killed by police in major American cities show that black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than white people (2013-2018). Movements such as Black Lives Matter started also because of this. Another problem is that it is extremely difficult to hold US police members accountable.

Sinyangwe underlined how it is necessary to research the components that predict police violence, and that can help hold officers accountable, to be sure that they are enforced by police departments.

Police union contracts – for example – can be considered an obstacle on the way to accountability and transparency. It is extremely rare to have a policeman convicted for a crime in the US. It is a systematic fact and it cannot be reduced just to the individuals, who are acting using brutal and deathful force. It is a matter of lack of training, lack of policies enhancing non-violent solutions, but there is also legislation that protects policemen from legal consequences. It is not easy even to sue a US policeman, as they are shielded by qualified immunity and often by confidential police records, limiting how officers are investigated and disciplined. As of today, this makes impossible to identify and punish misbehaviours, abuses, and responsibilities in most cases. According to Mapping Police Violence, a research collaborative collecting comprehensive data on police killings to quantify the impact of US police violence in communities that Sinyangwe set up, 99% of cases in 2015 have not resulted in any officer involved being convicted for a crime.

The Campaign Zero platform is designed to be a tool able to enhance participation, foster accountability and transparency. It is an instrument to prevent killings and it calls for the adoption of a comprehensive package of urgent policy solutions – informed by data, research and human rights principles – that can change the way police serve communities.

The last panellist of the day was the participatory video facilitator from the UK, Gareth Benest, who presented the “Giving Voice to Victims of Grand Corruption in The Gambia” participatory video project. It is an initiative implemented on behalf of Transparency International in reaction to “The Great Gambia Heist” investigations by OCCRP (Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project) revealed in March 2019, which allowed those affected by grand corruption to share their stories and present their truths in carefully edited video messages, and to give voice to those Gambians who are deprived from access to basic health, education, agriculture, and portable drinking water.

In Gambia, a truth and reconciliation commission has begun to investigate rights abuses during the 22-year-long dictatorship of Yahya Jammeh ended in 2017. OCCRP has exposed for the first time how the corrupted dictator and his associates plundered nearly 1 billion US$ of timber resources and Gambia’s public funds. Thousands of documents dated between 2011 and 2016, including government correspondence, contracts, and legal documents, bank records, internal investigations able to define in detail the level of corruption and impunity of the Gambian system.

After the end of Jammeh’s rule, authorities have declared they will shed light on corruption, extrajudicial killings, torture, and other human rights violations. It is an important process of reconciliation, but still the voices of the marginalized and rural citizens are not heard. ‘Giving Voice to Victims of Grand Corruption in The Gambia’ was meant to facilitate a process with Gambian community members to express their perspectives on local problems and ideas, translating them into a film.

Benest explained how such a project is supposed to enable these communities to focus on the issues they are affected by and move towards changing their circumstances.

The participatory video is a technique that has been used to fight injustice in different contexts for many years. Benest recalled recent projects involving a community displaced by diamond-mining, young people excluded from poverty eradication strategies, widows made landless by customary leaders, and island residents threatened with forced evictions by land grabbers. In his work, the facilitator encourages equal participation and rotation of rules within the team. Participants control every aspect of the video making, from the process to the final result. Self-directed and self-organised videos become a communication tool that allows participant to build a dialogue for positive change.

The second day of the Disruption Network Lab conference opened with the keynote speech of Matthew Caruana Galizia, WHAT INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATORS DON’T USUALLY DISCLOSE, in which he addressed issues freelancers investigating high-level corruption face in silence and isolation, often with tragic consequences. The journalist, in conversation with Crina Boros, talked about the background of his mother, the Maltese reporter and blogger Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed on the 16th of October 2017, outlining the risks and the outcomes of her dangerous and brave work.

Her murder had been planned in detail for a long time. Killers were arrested, but the mandators haven’t been identified yet, and the criminal investigation is not moving forward. Daphne Galizia’s family is pushing the issue internationally and within Malta, knowing that without doing something this case would just disappear from news headlines without solution. Anti-corruption investigative journalists are arrested, threatened, and killed everywhere. People just vanish, and no justice is done.

For the 15 years before her death, Daphne Caruana Galizia had been appearing in 65 court cases filed against her. Her bank account was frozen; she was a victim of media campaigns against her; and she was sued by politicians, businessmen, and other journalists too. Her son recalled when he was nine that their dog was found slaughtered, then the front door of their house was burnt down. Later on, one of their dogs was shot, and another poisoned. Threats and violence continued until their whole house was set on fire. No investigation was ever effectively put in place to find out the perpetrators of these crimes, though the journalist and her family had always pressed charges against unknown.

It is hard to be confronted with the pain and memories of personal events on a stage in front of an audience, but the issue of justice is too urgent. Even if talking about her gets more and more difficult every time, Matthew is travelling the world to keep fighting and demand justice for his mother.

Matthew had spent the last years working with his mother. The International corruption revealed by the Panama Papers – on which they were investigating – was not cause of resignations and public assumption of responsibility in Malta. Involved politicians and news outlets attacked with all available means independent journalists covering the cases. The pressure on Daphne intensified in such a way, that she was sued 30 times just in the last year before her death. In those moments she kept repeating to his son Matthew that, no matter how hopeless the situation, there is an urgency to strive to make corruption and responsibilities publicly known. The Maltese blogger was not naive, she was well aware that there was the risk of getting killed, as it happened to Anna Stepanowna Politkowskaja and many colleagues all over the world. But she did not give in.

Reviewing his mother’s life, Matthew mentioned a further aspect to consider: Daphne had to use much of her time and money to defend herself inside trials against her, which were long and very expensive. She had passion and abilities. She was so talented that she could publish a magazine about food, architecture, and design – on which she spent just a couple of days a month – to earn money enough to carry on with her independent investigation work, and pay for her legal defence.

When there is a whole system against you, you need very good lawyers, you need expertise, you need money to pay for it. The Maltese blogger spent a whole career overcoming the obstacles of a corrupted system and she self-sustained economically, making sacrifices. Although all this, still, his son Matthew and her family are convinced that the solution must come through the judicial way, using available legal instruments, and making pressure on EU institutions at the highest levels. That is why Matthew Caruana Galizia asks everybody for commitment in a demand of radical change. Malta is part of the European Union, as he keeps on repeating.

Someone has been trying to silence Daphne for years before her murder. They must have gotten to the conclusion that the only way to shut her up was an assassination, for the purpose to cancel her stories with her, as her son Matthew sadly commented. To avoid this happening, several newspapers and investigative organisations joined the «Daphne Project» a global consortium of 18 international media including Reuters, The Guardian, and Le Monde, to continue the work of the Maltese journalist. They are led by the group Forbidden Stories, whose mission is to continue the work of silenced journalists. They stand together because they think that even if you kill a journalist like Caruana Galizia, her investigations cannot be buried with her. Thanks to the Daphne Project, and the courage and determination of Daphne Caruana Galizia’s family, her investigation lives on.

Matthew stressed the fact that it’s not about the future of one politician, or of a specific criminal group. It is about the future of Malta and the EU. Journalists who defend democracy are alone when they face the repercussions of what they do. It is necessary to make sure that when there are outcomes due to effective journalism, a society trained to react and self-organise can pick up the investigative work, defend independent investigation, and ask for political accountability within a public discussion. In Malta, nothing of this ever happened, and Daphne became more isolated.

Grassroot citizens organisations are fundamental to boost activism inside local communities and demand for justice. In cases like Daphne’s, no one is going to do it if not organised citizens, together with independent journalists and organisations. Many killed journalists had neither a family nor an organisation that could fight on for them. Maltese Police seem to have never developed professional skills to effectively work on this kind of criminal cases, and the few results from recent years were from the FBI in the USA. Criminals within a system that guarantees impunity can easily develop better skills.

Moreover, in Malta, investigations have a very poor rate of success and in Daphne’s case, we just know how she was murdered. But the political atmosphere, in which this murder matured, has been untouched for these last two years, and the journalist’s family is worried the official inquiry that just started in the country is neither independent nor impartial. Members of the Board of Inquiry, they claim, have conflicts of interests at different levels, either because they were part of previous investigations or because they have ties to subjects who may be investigated now.

In the last panel of the conference, as Bazzichelli explained, the discussion focused on the connection between grassroots investigations and data analysis, and how it is possible to make sensitive data accessible without restriction and open them to the public, facilitating the publication of large datasets.

M C McGrath and Brennan Novak, introduced by moderator Shannon Cunningham, presented a tool designed to enable the publishing of data in searchable archives and the sorting through large datasets. The group builds free software to collect and analyse open data from a variety of sources. They work with investigative journalists and human rights organisations to turn that into useful, actionable knowledge. Their Transparency Toolkit is accessible to activists and citizen journalists, as well as those who lack resources or technical skills. Until a few years ago only big media organisations with particularly good technical resources could set up such instrumentation. The two IT experts decided to increase the use and the impact of open information, considering participation as a key factor to reduce the difficulties caused by relying only on media outlets or single journalists to cover complex facts or analyse large datasets.

As M C McGrath and Novak explained, Transparency Toolkit uses open data “to watch the watchers” and to hold powerful individuals and groups accountable. At the moment, their primary focus is investigating surveillance and human rights abuses, like in the case of the Hacking Team leaks in July 2015.

Hacking Team is an Italian company specialising in surveillance software and in very effective Trojans able to slip into computers and smartphones, allowing a secret and total surveillance. Four years ago, 400 GB of their data was anonymously published online, showing how the IT company had been working for authoritarian governments with questionable human rights records, to ensure they can use such software to spy on activists, journalists, and political opponents, in countries like Morocco, Dubai, Ethiopia, Mexico and Sudan. Transparency Toolkit mirrored the full Hacking Team dataset to make it more available to journalists and security researchers investigating these issues. It released a searchable archive of 200GB of emails categorized by companies, countries, events, and other subjects discussed.

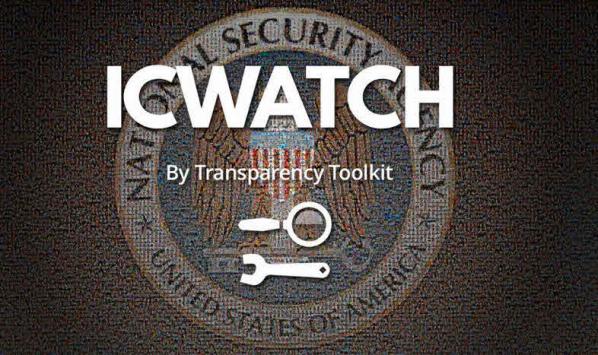

Other important projects from the Transparency Toolkit team are the Surveillance Industry Index (SII) developed together with Privacy International (a searchable archive featuring over 1500 brochures about surveillance technology, data on over 520 surveillance companies, and nearly 500 reported exports of surveillance technologies), the Snowden Document Search (the first comprehensive database of Snowden documents initiated which aims to preserve its historical impact), and ICWATCH – a platform born to collect and analyse resumes of people working in the intelligence community, contractors, the military, and intelligence. These resumes are useful for uncovering new surveillance programs, learning more about known codewords, identifying which companies help with which surveillance programs, examining trends in the intelligence community, and more. ICWATCH provides a collection of over 100,000 of these resumes from LinkedIn, Indeed, and other public sources, and now searchable with a search engine called LookingGlass.

The last part of this panel was than dedicated to the Dictator Alert project, a website that tracks the planes of authoritarian regimes all over the world. Available networks censor the information about planes of intelligence, military, authorities, and heads of state. This project, run by Emmanuel Freudenthal and François Pilet with support from OCCRP, began as an open-source computer program to identify planes belonging to dictators flying over Geneva. The program mined data from a network of antennas used by plane spotters and shared its alerts via Twitter. Today, Dictator Alert uses data from ADSB-Exchange, as well as several antennas installed by the team of researchers themselves. The details of each plane captured by the antennas are compared with a list of aircrafts registered or regularly used by authoritarian regimes. When a match is found, a message is published on the website.

Freudenthal presented the methodology of acquiring information behind Dictator Alert. Some people in the audience disagreed with the panellists, arguing that a reductive definition for ‘dictator’ might questionably influence the outcomes of the project, considering that some elected leaders from countries listed as democracies are also responsible for crimes, secrets, and human rights violations. The investigative journalist responded by explaining that Dictator Alert is orientated using the Democracy Index published by The Economist. The Index appeared first in 2006, categorising countries as full democracies, flawed democracies, hybrid regimes, and authoritarian regimes, based on 60 indicators grouped in different categories, measuring pluralism, civil liberties, and political culture.

The Disruption Network Lab organised the workshop Berlin’s Sky, An Afternoon Investigation on the day following the 17th Conference. Participants gathered in the former Berliner airport Tempelhofer Feld to conduct guided research using antennas and laptops to track the sky and spot anomalies above the city.

The conference closed with the investigation by Forensic Architecture – Horizontal Verification and the Socialised Production of Evidence. Team member Robert Trafford presented the organisation founded to investigate human rights violations using a range of techniques, flanking classical investigation methods including open-source investigation video analysis, spatial and architectural practice, and digital modelling. They work with and on behalf of communities who have been affected by state and military violence, producing evidence for legal forums, human rights organisations, investigative reporters and media, as well as for arts and cultural institutions.

In Trafford´s analyses, conflict, violence, and human rights violations have become heavily mediatised and because of the “open source revolution” and smartphones, facts are often documented and relayed to the world by fragments of video material. Media sometimes report about these facts in ways which seem to make them less clear, instead of allowing better understanding. Forensic Architecture is in part a set of technical and theoretical tools for unpacking those mediatised facts, to access the truth which often exists behind and between the fragments of files that are released or leaked, to prove human rights violations. It relies on the prevalence of open source video material and tries to put an order in the fake-news and post-truth communication, offering a new model for collectively and collaboratively constructing truths. Trafford pointed out how people today, who seem to be widely rejecting the idea of institutions that they might previously have trusted to assemble facts and information, are still able to accomplish this delicate task. Often truth seems to be created elsewhere, possibly behind a wall of closed sources. The Internet and the consequent open-source revolution exploded the stability of that classic system of information, and those institutions are no longer providing truths around which people are willing or able to orient themselves. For better or worse, the vertical has been supplanted by the horizontal, Trafford said.

As those institutions falter, there is a certain breed of political actors – largely from populist and far-right parties – that have been gaining mediatic and institutional power all over the world for the last five years, encouraging the public to believe that our societies are soaked in misinformation, and that there is no possibility of reaching out and acquiring reliable facts we can all agree on and orient ourselves with.

More and more often, online and offline, we read of individuals saying that we should not trust traditional news outlets or institutions that encourage us to believe that they can guarantee independent and free information. It is under this cover of equivocation and uncertainties that the human rights violations of the 21st century are being carried out and subsequently concealed.

Forensic Architecture’s challenge is to expose this misrepresentation of things, and to offer a kind of counter truth to official versions of relevant facts. Its researchers collect little grains, clues they find inside videos, pictures, and articles that try to organise in certain ways, reassembling them into an independent analysis. By using different perspectives into ongoing practice in which the development of facts and evidence is socialized, the project encourages open and horizontal verification.

The moderator of this last session of the conference, Laurie Treffers, mentioned the idea of counter forensics. By integrating and working across different forms of knowledge, and across different institutions and disciplines – which may at times appear like they have nothing in common or that they speak in entirely different registers – horizontal verification is about unifying those for reasons of mutual protection, mutual security, and mutual reinforcement.

Trafford gave examples of Forensic Architecture’s work, such as working closely with the Gaza-based Al Mezan Center for Human Rights, the Tel Aviv-based Gisha Legal Center for Freedom of Movement, and the Adalah Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Haifa, when they examined the environmental and legal implications of the Israeli practice of aerial spraying of herbicides along the Gaza border.

To this end, the investigation sought to define if and how airborne herbicides travel into Gaza; how far into its territories they entered; what concentration of herbicide and what damage to the farmland on the Gazan side of the border can be calculated. The analysis of several first-hand videos, collected in the field, revealed that aerial spraying by commercial crop-dusters flying on the Israeli side of the border generally mobilises the wind to carry the chemicals into the Gaza Strip at damaging concentrations. This is a constant primary effect.

The videos used for the investigations supported the testimonies of farmers that, prior to spraying, the Israeli military uses the smoke from a burning tire to confirm the westerly direction of the wind, thereby carrying the herbicides from Israel into Gaza.

Forensic Architecture modelled the Israeli flight paths and geo-located them, compared metadata and video material, and engaged fluid dynamics experts from the University of London to look at what the potential distribution of those chemicals would be from the heights that the plane was flying, in the wind conditions that could be calculated. The investigation proves that each spray leaves behind a unique destructive signature.

“Along with the regular bulldozing and flattening of residential and farmland, aerial herbicide spraying is one part of a slow process of ‘desertification’, that has transformed a once lush and agriculturally active border zone into parched ground, cleared of vegetation,” Trafford said.

Analyses of the evidence derived from vegetation on the ground, civilian testimony, and the environmental elements mobilized in the spraying event showed that the Israeli practice of aerial fumigation at times when the wind is blowing into Gaza causes damage to farmland hundreds of meters inside the fields.

Once again, the Disruption Network Lab created a forum for discussion, to define the role of citizens in making a change in the information sphere, highlighting local and international stories, tools, and tactics for social change built on courageous grassroots reporting and investigations. The Disruption Network Lab invited guests to challenge laws that effectively criminalise journalism and whistleblowing. The conference went beyond the usual dichotomy between journalists and activists, official media and independent media, and opened up a dialogue among different expertise to discuss and present opportunities of collaboration to report misinformation, corruption, abuse, power asymmetries, and injustice.

CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE presented experts working on anti-corruption, investigative journalism, data policy, political activism, open source intelligence, video storytelling, whistleblowing, and truth-telling, who shared community-based stories to increase awareness on sensitive subjects. Bottom-up approaches and methods that include the community in the development of solutions appear to be fundamental. Projects that capacitate collectives, minorities, and marginalized communities, to develop and exploit tools to systematic combat inequalities, injustices, and impunity are to be enhanced.

Moreover, on the 29th of October, the CPJ published the 2019 Global Impunity Index, putting a spotlight on countries where journalists are slain and their killers go free. During the 10-year index period, 318 journalists were murdered for their work worldwide and no perpetrators have been successfully prosecuted in 86% of those cases. Last year, CPJ recorded complete impunity in 85% of cases. Historically, this number has been closer to 90%. All participants at the conference expressed their concern about this situation.

It is important to doubt and require a double-check over relevant news, as governments and private corporations have proved too often, that they prefer secret and manipulation to transparency and accountability. It is also important to verify constantly if media outlets, or a single journalist, are actually independent. But this shall not be used to weaken independent information and undermine the principles of particular constitutional importance regarded as ‘higher law’ on which it is based. Journalists and citizen reporters are already alone in their work.

CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE was curated by Tatiana Bazzichelli, developed in cooperation with Transparency International. It was the third in Disruption Network Lab’s 2019 series ‘The Art of Exposing Injustice’. Videos of the conference are also available on YouTube. For details of speakers and topics, please visit the event page here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/citizens-of-evidence.

To follow the Disruption Network Lab, sign up for its newsletter with information on conferences, ongoing researches, and projects. You may also find the organisation on Twitter and Facebook.

The next Disruption Network Lab event ‘ACTIVATION – COLLECTIVE STRATEGIES TO EXPOSE INJUSTICE’ is planned for November 30th, in Kunstquartier Bethanien Berlin. More info here: https://www.disruptionlab.org/activation

Image Credit:

Elena Veronese for Disruption Network Lab

Featured Image:

Graphic courtesy of Disruption Network Lab

On June the 16th Tatiana Bazzichelli and Lieke Ploeger presented a new Disruption Network Lab conference entitled “AI TRAPS” to scrutinize Artificial Intelligence and automatic discrimination. The conference touched several topics from biometric surveillance to diversity in data, giving a closer look at how AI and algorithms reinforce prejudices and biases of its human creators and societies, to find solutions and countermeasures.

A focus on facial recognition technologies opened the first panel “THE TRACKED & THE INVISIBLE: From Biometric Surveillance to Diversity in Data Science” discussing how massive sets of images have been used by academic, commercial, defence and intelligence agencies around the world for their research and development. The artist and researcher Adam Harvey addressed this tech as the focal point of an emerging authoritarian logic, based on probabilistic determinations and the assumption that identities are static and reality is made through absolute norms. The artist considered two recent reports about the UK and China showing how this technology is yet unreliable and dangerous. According to data released under the UK´s Freedom of Information Law, 98% of “matches” made by the English Met police using facial recognition were mistakes. Meanwhile, over 200 million cameras are active in China and – although only 15% are supposed to be technically implemented for effective face recognition – Chinese authorities are deploying a new system of this tech to racial profile, track and control the Uighurs Muslim minority.

Big companies like Google and Facebook hold a collection of billions of images, most of which are available inside search engines (63%), on Flickr (25%) and on IMdB (11 %). Biometric companies around the world are implementing facial recognition algorithms on the pictures of common people, collected in unsuspected places like dating-apps and social media, to be used for private profit purposes and governmental mass-surveillance. They end up mostly in China (37%), US (34%), UK (21%) and Australia (4%), as Harvey reported.

Metis Senior Data Scientist Sophie Searcy, technical expert who has also extensively researched on the subject of diversity in tech, contributed to the discussion on such a crucial issue underlying the design and implementation of AI, enforcing the description of a technology that tends to be defective, unable to contextualise and consider the complexity of the reality it interacts with. This generates a lot of false predictions and mistakes. To maximise their results and reduce mistakes tech companies and research institutions that develop algorithms for AI use the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) technique. This enables to pick a few samples selected randomly from a dataset instead of analysing the whole of it for each iteration, saving a considerable amount of time. As Searcy explained during the talk with the panel moderator, Adriana Groh, this technique needs huge amount of data and tech companies are therefore becoming increasingly hungry for them.

In order to have a closer look at the relation between governments and AI-tech, the researcher and writer Crofton Black presented the study conducted with Cansu Safak at The Bureau of Investigative Journalism on the UK government’s use of big data. They used publicly available data to build a picture of companies, services and projects in the area of AI and machine learning, to map what IT systems the British government has been buying. To do so they interviewed experts and academics, analysed official transparency data and scraped governmental websites. Transparency and accountability over the way in which public money is spent are a requirement for public administrations and they relied on this principle, filing dozens of requests under the Freedom of Information Act to public authorities to get audit trails. Thus they mapped an ecosystem of the corporate nexus between UK public sector and corporate entities. More than 1,800 IT companies, from big ones like BEA System and IBM to small ones within a constellation of start-ups.