DIWO (Do-It-With-Others): Origin, Art & Social Context, is an update on Furtherfield’s artistic and cultural practice of DIWO. In light of the emergence of DIWO in other fields of creative practices, and its ever growing popularity. We reconnect to the original reasons of why Furtherfield introduced and shared the concept of DIWO to the world in the first place.

We revisit early historical influences from 60s and 70s Mail Art, Fluxus, Situationism, Activism and D.I.Y culture; early adventures/projects with pirate radio, a mass networked email art, and (snail mail) mail art’, street art project by Furtherfield back in 1999; to what DIWO is now today, part of a more extensive, and networked grass roots movement around the world.

It also draws upon links to P2P (peer to peer) culture, the free and open source movement. Each of these cultural activities are seen as equal, peer relations, and re-hacks an intuitive space away from traditional hegemonies and their established hierarchies.

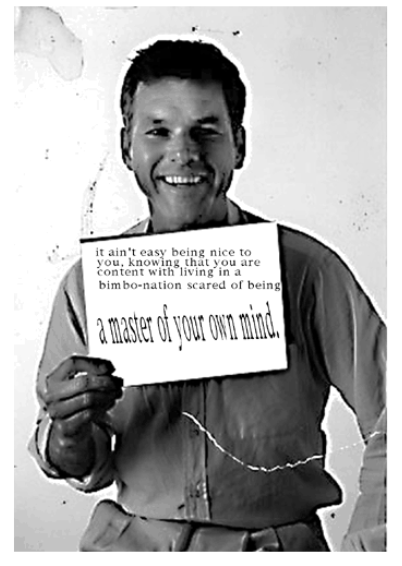

It re-emphasize it’s core motives, as a critique against mainstream media and the traditional art establishment’s control over our art history and contemporary art imaginations. It challenges the non-critical nature of artists’ complicit desire in conforming to celebrity status and fitting into stereotypical behaviours informed by hegemony, and cultural dominance. Furthefield’s intention for DIWO has always been a about individual and collective emancipation, and this story is about what this means now…

Before we jump into Furtherfield’s first DIWO project it’s worth mentioning an earlier historical reference to Bristol city (UK) and pirate radio. I, and a dedicated group of individuals were interested in finding alternative avenues for community and collective expression. We set up various pirate radio stations in Bristol, the longest running was ‘Electro Magnetic Installation (EMI)’ pirate radio station, which ran for over 18 months, broadcasting to greater Bristol every weekend ending in 1991. We changed our location for each broadcast and disseminated disinformation to confuse the authorities. We used a home built 20 Watt stereo FM transmitter and antenna. All submitted material was provided on audio tape for broadcast, the quality or quantity was not edited and everyone interested had their sound art, cut up mixes, music and words heard by many. We had to close down after a while due to surveillance stress. We did re-emerge with other pirate radio broadcasts briefly, under various different names. An even earlier one, which we took over for a while was called ‘savage but tender’ in 1989.

Bristol in the late 80s and early 90s was a dynamic and exciting place to be. Especially if one was creative and also interested in alternative ways of thinking and living. Independent culture was thriving. It was back in the 70s when Bristol’s radical spirit of creative and political autonomy was first forged. Post punk bands such as the Pop Group, Rip Rig & Panic, spread their own influential ethos of being creative and activist as a way of life. Advocating everyday people could be different, be independent thinkers and question the validity of the established norm. This flexible blueprint of being socially conscious in an imaginative way influenced a huge mixture of genres for years to come. Breaking down the borders between the audience and the musicians playing was a legacy handed on down from punk. This includes building your own record label, setting up your own pirate radio station, self publishing and other ventures.

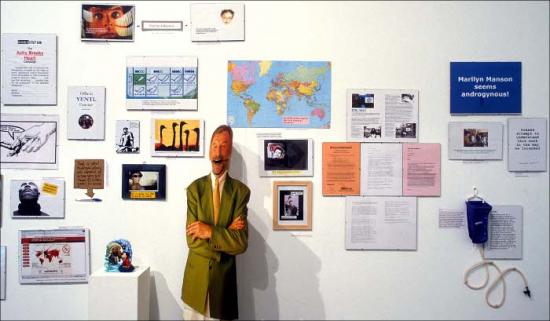

Furtherfield’s first collective (yet unofficial) DIWO experience was at the Watermans Art Centre, London in 1999. We were asked to present a project which reflected the free and liberated spirit of our networked on-line community and its creative culture. The name of the project was called “Pasteups@Watermans Art Centre”, not DIWO. It had all the features of DIWO, such as using email as art, and the traditional postal services (snail mail) as part of its distribtion process. From all over the world people were invited to send images and texts which were then enlarged into a mass of photocopied posters.

On Sunday 10th October 1999 all the hoardings and wall spaces in the streets around the Watermans Art Centre were blitzed with Pasteups. There was no selection of what should be taken out or left in, everything was shown. They were put up by the Furtherfield crew and who ever wished to help out. Some of those whom took part were also local to the area. The people working in the centre reacted as if they were being over taken from a dark external force, and the passing public were expressing a mixture of emotions – enjoyment, surprise, interest, confusion, distaste and annoyance. It challenged the ideal of art having to be a rigid divide and rule of amateur vs professional, using the Internet and the physicalness of the Watermans Art Centre’s building, inside and outside. The streets were used as a shared canvas to fill our collective, imaginative expressions at that time.

“”… the role of the artist today has to be to push back at existing infrastructures, claim agency and share the tools with others to reclaim, shape and hack these contexts in which culture is created.” [1] (Catlow 2010)

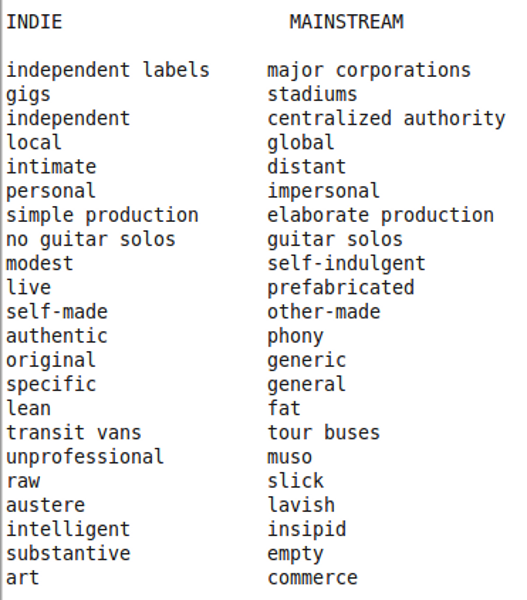

In her study ‘Empire of Dirt: The Aesthetics and Rituals of British Indie Music (Music Culture)’, Dr. Wendy Fonarow [2] investigated the UK’s indie music scene and its culture from the early 1990s to present. Below Fonarow presents the differences between mainstream and independent music culture. Contrasts are mapped out in Lévi-Straussian fashion:

“Indie itself in relation to the mainstream as an opositional force combating the dominant hegemony of modern urban life. Any band that is seen as “chipping away at the facade of of corporate pop homogeny” (Melody Maker, April 1995) is a positive addition to the indie fellowship.”[3] (Fonarow 2006)

There are similar terms above as there is with critical practices in Media Art culture, Free and Open Source culture, activism and hacktivism, and with concepts behind DIWO. Words such as self-made, independent, raw and substantive offer strong relational ties to what we feel ourselves is essential for a thriving, discerning and critically aware process, of an unfettered state of discovering, and how to do things without conforming to top-down protocols, individually or collaboratively.

“To be an artist is to contend with the present, and there are not many other careers that afford the freedom to radically examine life and society. To put it bluntly, if artists are studying and writing more about politics, culture, and education, it’s probably a reflection of the unprecedented dysfunctionality of the societies in which they live.” [4] (Deck 2005)

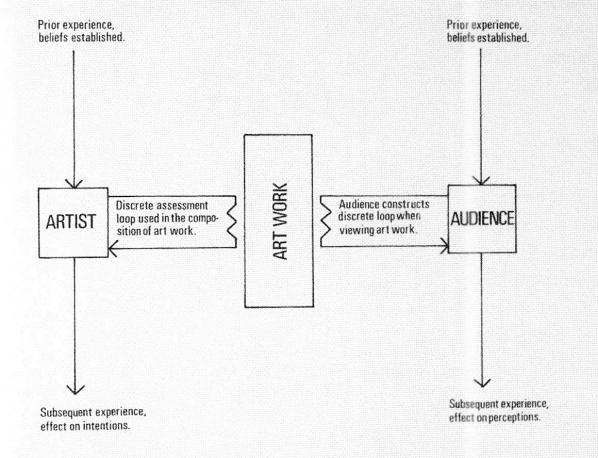

When considering an art context, critical thinking on the social nuances, social and relational variants introduce possibilities for a deeper understanding of the meaning of a work and its place in the wolrd. Not only in respect of the quality of an artwork in its own right, but it also introduces consideration concerning value. Value comes out of dialogue whilst the work is put into motion, as the process occurs as well as when it reaches its final stage of being seen – it’s birth is always messy, but this process gives us the rich nutriants, the substance.

By recognising resonances that lurk between art and culture and our own connections with these elements; as we make things with others different core values come into play. This is where knowledge of how an artwork and its meaning communicates beyond the artwork itself; to and with others, linking up to the ever changing rhythms dominating society. All this, also depends on the context of how and where a work is seen. An artwork and where it is seen declares the artists’ relationship with other structures, infrastructures and networks, whether this be physical or based on-line. This informs us about the artists’ personal concepts, attitudes and social values. These attributes become part of the work; its story and part of its essence and its reasons for existing in the first place.

Whoever controls our art – controls our connection, relationship and imaginative experience and discourse around it. The frameworks and conditions where art is accessed, seen and discussed is significantly linked to representation and ownership. Socially and culturally, this process of abiding by specific rules and protocols defines who and what is worth consideration and acceptance. For art to be accepted within these ‘traditional’ frameworks a dialogue reflecting its status around a particular type of function kicks into place, it must adhere to certain requirements. Whether it is technological or using traditional art making skills the art itself must in some way conform to specific protocols before it can be allowed into the outer regions of ‘officially’ condoned culture. This process adds merit to the creative venture itself and feeds a systemic demand based around innovation in a competitive marketplace. If an iindividual or an collective does not abide by these dominating rules then they will not be seen in these frameworks. DIWO allows one to venture with many, in playful scenarios of mutual experience and interdependence, freeing up the trappings of ‘officially’ defined protocols and frameworks, governing our behaviours. This does not mean that there are no rules, it merely means that we have a more relationally informed understanding of how to work with others. Structures and aims are decided in different terms mutually.

DIWO is playful re-interpretation and fruition of some of the principles and reasons that Furtherfield was originally founded, back in 96-97. We had experienced as artists in the 80s and well into the 90s, a UK art culture mainly dominated by the marketing strategies of Saatchi and Saatchi. The same company was responsible for the successful promotion of the Conservative Party (and conservative culture) that had led to the election win of the Thatcher government in 1979. We felt that it was time to make a stance against these neoliberalist heavies controlling the art scene and our every day culture. Our aim was to move away from the typically established, sociallly engineered aspects of art culture where false credence was given to a few individuals over many others, based on their personalities alongside their depoliticized artworks.

“Furtherfield’s roots extend back through the resurgence of the national art market in the 1980s, to the angry reactions against Thatcher and Major’s Britain, to the incandescence of France in May 1968, and back again to earlier intercontinental dialogues connecting artists, musicians, writers, and audiences co-creating “intermedial” experiences.” [5] (Da Rimini 2010)

Our move away from this was to create pro-active alternatives, with social hacks, bypassing the marketing myth of the ‘genius’ as a product via the usually distracting diversions, and top-down imposed spectacles based on privilege and hegemony. Recently an article written by John A. Walker on the artdesigncafé web site, disucussed how art culture is still haunted by the power of Charles Saatchi.

“Arguably, as an art collector Charles Saatchi has become a brand in his own right—when he buys art works they and the artists who created them are immediately branded.” [6] (Walker 2010)

BritArt’s dominance of the late 80s and 90s UK art world dis-empowered the majority of British artists, and Smothered other artistic discourse by fuelling a competitive and divisive attitude for a shrinking public platform for the representation of their own work. Stewart Home proposes that the YBA movement’s evolving presence in art culture fits within the discourse of totalitarian art.

“The cult of the personality is, of course, a central element in all totalitarian art. While both fascism and democracy are variants on the capitalist mode of economic organisation, the former adopts the political orator as its exalted embodiment of the ‘great man,’ while the latter opts for the artist. This distinction is crucial if one is to understand how the yBa is situated within the evolving discourse of totalitarian art.” [7] (Home 1996)

By questioning the myths that dominate our actions we then become more empowered and confident to collaborate with others. We can only rediscover these inner creative kernals by critiquing the infrastructures dominating our behaviours. Many artists have and do conform to mainstream art world rules. This closes down space for a wider dialogue and experience for art practice to expand its possible horizons, beyond a handed down, hermetically sealed set of distant processes. When experimenting with alternative approaches of imaginative engagement a different set of values arrive. Through this we unearth things about ourselves which were already there but were trapped before by the mechanisms and mannerisms of mainstream culture and its dominant values.

DIWO (Do It With Others) is inspired by DIY culture and cultural (or social) hacking. Extending the DIY ethos with a fluid mix of early net art, Fluxus antics, Situationism and tactical media manoeuvres (motivated by curiosity, activism and precision) towards a more collaborative approach. Peers connect, communicate and collaborate, creating controversies, structures and a shared grass roots culture, through both digital online networks and physical environments. Stringly influenced by Mail Art projects of the 60s, 70s and 80s demonstrated by Fluxus artists’ with a common disregard for the distinctions of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art and a disdain for what they saw as the elitist gate-keeping of the ‘high’ art world.

The term DIWO OR D.I.W.O, “Do It With Others” was first used on Furtherfield’s collaborative project ‘Rosalind’ (http://www.furtherfield.org/get-involved/lexicon). An upstart new media art lexicon, born in 2004. DIWO was officially termed here in 2006 (http://www.furtherfield.org/lexicon/diwo)

“It is in the use of the postal system, of artists’ stamps and of the rubber stamp that Nouveaux Realisme made the first gestures toward correspondence art and toward mail art.” [8] (Friedman 1995)

Mail Art is a useful way to bypass curatorial restrictions for an imaginative exchange on your own terms. With DIWO projects we’ve used both email and snail mail. Later, we will return to the subject of email art and how it has been used for collective distribution and collaborative art acitivies; but also, how it can act as a remixing tool and an art piece in its own right on-line and in a physical, exhibiting environment.

“[…] many Fluxus works were designed specifically for use in the post and so the true birth of correspondence art can arguably be attributed to Fluxus artists.” [9] (Blah Mail Art Library)

Many consider George Maciunas was to Fluxus, what Guy Debord was to Situationism. Maciunas set up the first Fluxus Festival in Weisbaden in Germany, 1962. In 1963, he wrote the Fluxus Manifesto in 1963 as a fight against traditional and Establishment art movements. In a conversation with Yoko Ono in 1961, they discussed the term and meaning of Fluxus. Showing Ono the word from a large dictionary he pointed to ‘flushing’.

“”Like toilet flushing!”, he said laughing, thinking it was a good name for the movement. “This is the name”, he said. I just shrugged my shoulders in my mind.” [10] (Ono 2008)

“The purpose of mail art, an activity shared by many artists throughout the world, is to establish an aesthetical communication between artists and common people in every corner of the globe, to divulge their work outside the structures of the art market and outside the traditional venues and institutions: a free communication in which words and signs, texts and colours act like instruments for a direct and immediate interaction.” [11] (Parmesani 1977)

Maciunas’s intentions and ideas are strongly based on creative autonomy. DIWO in the 21st Century explores its own position of (social) grounded reasoning and creative chaos. In contrast to the usual, standardized and bureaucratic implimentations by an increasingly banal, neoliberal elite controlling our art, education, media and economies.

“[…] art has become too narcissistic and self-referential and divorced from social life. I see a new form of participatory art emerging, in which artists engage with communities and their concerns, and explore issues with their added aesthetic concerns” [12] (Bauwens 2010)

“Marshall McLuhan once suggested that ‘art was a distant early warning system that can always tell the old culture what is beginning to happen to it'” [13] (Gere 2002) The infrastructural tendencies that occur when ‘the many’ practice DIWO; informs us we are in a constant process which redefines the role of the individual, and our notions of centralized power and behaviour. This process also presents us with critical questions around the value of art as scarcity. In moving away from our emotional attachment with the socially engineered dependencies based on consumer led forms of scarcity and desire, we then change the defaults. If we change the defaults we change the rules, no longer besieged by top-down defaults and open to more intuitive and relational contexts.

DIWO proposes in its fluid and sensual action of immediacy; situations where anyone can play and initiate collaborative and autonomous art. It is a radical creativity, asking questions through process and peer engagement, loosening infrastructural ties and frameworks as it occurs.

DIWO is a contemporary way of collaborating and exploiting the advantages of living in the Internet age. By drawing on past experiences with pirate radio, historical inspirations from Punk, with its productive move towards independent and grass roots music culture, as well as learning from Fluxus and the Situationists, and peer 2 peer methodologies; we transform our selves into being closer to a more inclusive commons. We transform our relationship with art and with others into a situation of shared legacy and emancipation.

“The network is designed to withstand almost any degree of destruction to individual components without loss of end-to-end communications. Since each computer could be connected to one or more other computers, Baran assumed that any link of the network could fail at any time, and the network therefore had no central control or administration (see the lower scheme).” [14] (Dalakov 2011)

Even though the web and DIWO possess different qualities they are both forms of commons. They both belong to the same digital complexity, and involve us connecting with each other. They are both open systems for human and technological engagement. DIWO rests naturally within these frameworks much like other digital art works or platforms and related behaviours, but possess key differences. If we consider the functions and structures of Facebook, Google, MySpace, itunes and now Delicious, they are all centralized meta-platforms, appropriating as much users as possible to repeatedly return to the same place.

“We see social media further accelerating the McLifestyle, while at the same time presenting itself as a channel to relieve the tension piling up in our comfort prisons.” [15] (Lovink 2012)

These meta-platfroms are closed systems. Not, necessarily closed as in meaning ‘you cannot come in’, but closed to others if you consider their motives and ‘acted out’ values, exploiting human interaction and their uploaded material, and openly ‘given’ data-information. These centralized meta-platforms close choices down through rules of ownership of personal data, as well as introducing more traditional standards of hierarchy, and limits one’s view and potential experience of the Internet.

Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron saw this curious dichotomy way back in 1995. On one hand we had the dynamic energy of sixties libertarian idealism and then on the other, a powerful hyper-capitalist drive, Barbrook and Cameron termed this contradiction as ‘The Californian Ideology’. “Across the world, the Californian Ideology has been embraced as an optimistic and emancipatory form of technological determinism. Yet, this utopian fantasy of the West Coast depends upon its blindness towards – and dependence on – the social and racial polarisation of the society from which it was born. Despite its radical rhetoric, the Californian Ideology is ultimately pessimistic about real social change.” [16] (Barbrook and Cameron 1995)

Instead of submitting to an imperious process of allowing bland interaction own our behaviours; we propose an engagement where we can be more conscious and in control by exploiting further the real potential of the networks before us.

“We are not going to demand anything. We are not going to ask for anything. We are going to take. We are going to occupy.”[17] (RTS 1997)

Just like Reclaim the Streets which was an anti-car direct action movement seizing roads to prevent cars from being able to access them. Filling up public areas with thousands of bikes and using street parties as part of the political protest. We can loosen the gaze and spectacle of these propriety, meta-platforms and their dominance of our actions with others on the Internet. DIWO, is a way of thinking and acting differently, not an absolutist ‘technologically determined’ factor, but a thing of many things, and leans more towards a kind of social activism going as far back as The Diggers:

“The Diggers [or ‘True Levellers’] were led by William Everard who had served in the New Model Army. As the name implies, the diggers aimed to use the earth to reclaim the freedom that they felt had been lost partly through the Norman Conquest; by seizing the land and owning it ‘in common’ they would challenge what they considered to be the slavery of property. They were opposed to the use of force and believed that they could create a classless society simply through seizing land and holding it in the ‘common good’.” [18] (Fox)

Three elements pull DIWO together as a functioning whole, which can mutute according to a theme, situation or project. These three contemporary forms of (potential) commons mainly include; the ecological – the social – and the networks we use. By appropriating these three ‘possible’ processes of being with others; combined, they introduce and enhance potential for an autonomous and artistic process to thrive, further than the limitations of any single or centralized point of presence. It brings about small societal change, as long as we are conscious of the social nuances needed for a genuine and critically engaged, mutual collaboration.

“Online creation communities could be seen as a sign of reinforcement of the role of civil society and make the space of the public debate more participative. In this regard, the Internet has been seen as a medium capable of fostering new public spheres since it disseminates alternative information and creates alternativ (semi) public spaces for discussion.” [19] (Morell 2009)

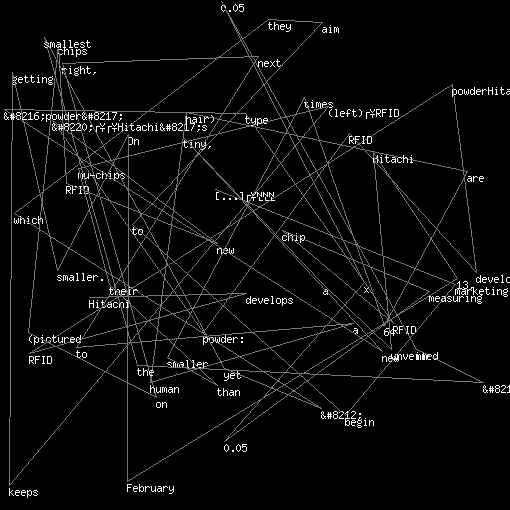

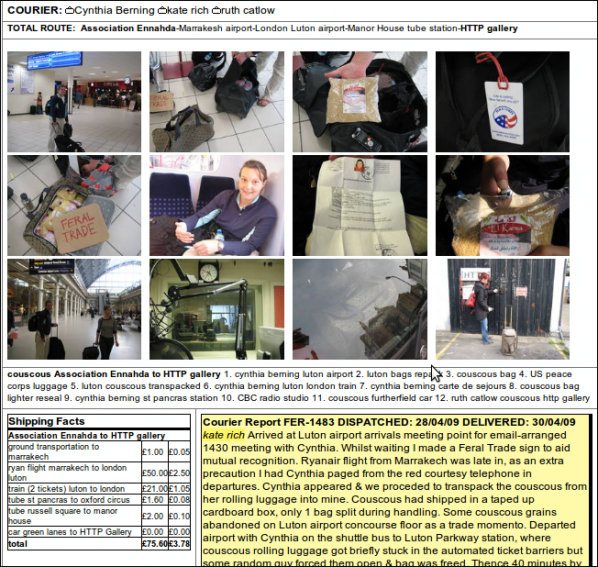

In accordance with Mail Art tradition, DIWO began with an open-call to the Netbehaviour email list on 1st February 2007. The exhibition was at our older venue the HTTP Gallery, opening at the beginning of March. Every post to the list until 1st April was considered an artwork – or part of a larger collective artwork for the DIWO project. Participants worked across time zones, geographical and cultural distances with digital images, audio, text, code and software; they worked to create streams of art-data, art-surveillance, instructions and proposals, and in relay to produce threads and mash-ups.

One example of a work which exploited the data-steams of continual flow while over a hundred individuals participated and collaborated in DIWO in 2007, was X-ARN.org (Gregoire Cliquet, Laurent Neyssensas and Yann le Guennec). By using the dynamic exchange of the Netbehaviour email list as reliable exchange of regualr content, the net art group were able to perform their particular and unique processes of interaction, or intervention. It had no specific title, it was literally documenting the list’s networkked behaviour, and there were many of these networked visualizations made. They experimented with the net-specific aspects of DIWO’s mass artistic activity, forming digital mappings of this collected data or data-streams in ‘real-time’, as it all happened.

![[ARN / DIWO-Betatests 2007]](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/attachment3.png)

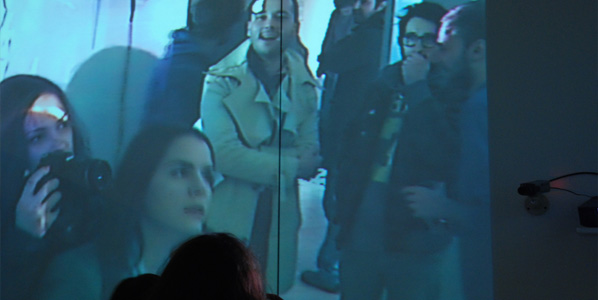

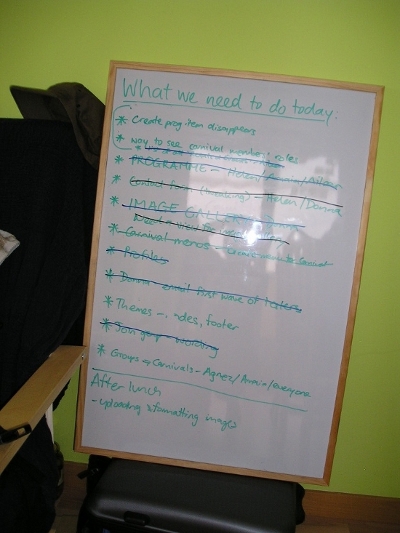

Some also participated in the experimental networked curation of the exhibition, facilitated by web cams, public IRC and VOIP technology. This co-curation event, or Curate With Others (CWO), as it was retroactively named, took place a week before the gallery opening. All subscribers to the NetBehaviour list were invited to contribute to the curation of the exhibition either by viewing the gallery floor plan and posting suggestions to the list or by taking part in the event; attending the gallery or joining the online meeting. Information about how to join the online event was posted to the list. During this event the spirit and philosophy of DIWO E-mail-Art were discussed, the deluge of diverse contributions by about a 100 people were reviewed, plinths, monitors and a drawing machine.

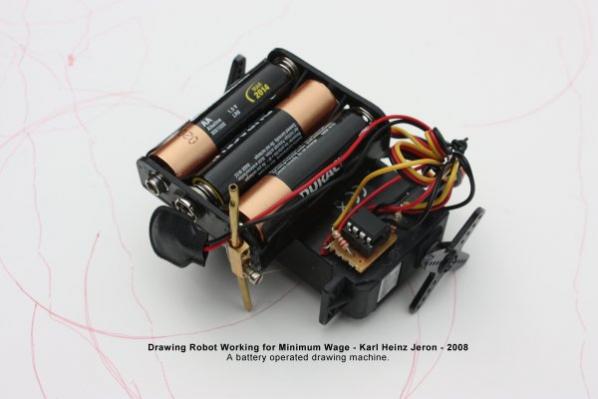

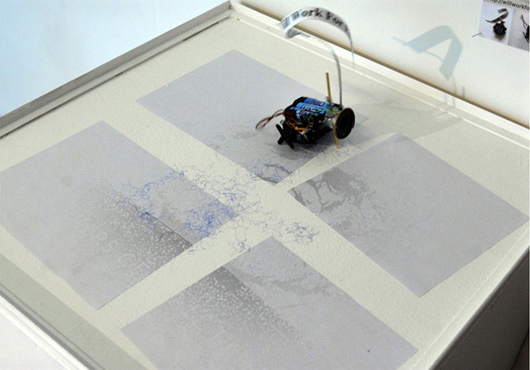

“The ‘Will Work For Food’ happening deals with the desire to find a new definition for labour and the act of working.” [20] (Jeron 2007)

Karl Heinz Jeron’s drawing machine was a vehicle equipped with a ballpen run by rechargable batteries, and when turned on created random drawings. Jeron’s machine was not switched on, unless he received gifts in the post such as chocolates or any other form of economic support. After (thankfully) receiving various contributions in the post the image supplied by Jeron of Karl Marx would gradually be scribbled over.

This section of the Article is an edited version of a collaborative text by Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett. Originally published on Vague Terrain in 2008. [21]

Present in the flesh were the Furtherfield.org crew and James Morris (regular, esteemed DIWO contributor).

Frederik Lesage manned the Public IRC and, as ‘DIWOchatbod’, who documented the conversation in the gallery for the benefit of those online co-curators who had trouble logging into Skype. Through the afternoon the online event was visited by eight people. The CWO event determined the format of the DIWO exhibition and the Furtherfield.org crew was charged with installing it. So, about approxximately 15 individuals on the day co-curated the setting up of the exhibition. Afterwards we informed everyone on the Netbeahviour list for any last minute details and suggestions and then continued with everything.

(Floorplan of Do It With Others (DIWO) at HTTP-Gallery, London. 2007)

The centerpiece of the exhibition was an e-mailbox containing all submissions; sorted and categorised for visitors to explore and redistribute by clicking ‘Forward Mail’. Streams and Themes displayed images, texts, sounds, code, and movies, primarily by single contributors (human and machine) as well as collections of themed posts or particular kinds of activity). Threads contained series of dialogic emails whose senders were remixing images, movies and code, most often in action and response). Other categories included Proposals and Instructions and Approaches to E-Mail Art.

(DIWO curated emailbox displaying image 3 tampered, posted by Chris Fraser 28/02/07)

Many of the themed folders and subfolders had their corollaries in the physical space of the gallery in the form of wiggly overlapping streams of printed images, pinned to the walls. Threads were represented by scrolls; one post after another in chronological order. A TV ran a video compilation, a sound compilation was played over four speakers, and two installation works were devised especially for the space. Karl Heinz Jeron’s ‘Will Work for Food’ and a print/projection mashup by Thomson and Craighead and Michael Szpakowski.

(Visitor to DIWO E-Mail Art at HTTP Gallery explores the DIWO email box. 2007. Image by Pau Ross)

All categories were liberally interspersed with off-topic discussion, tangents and conversational splurges so one challenge for co-curators was to reveal the currents of meaning, and emerging themes within the torrents of different kinds of data, process and behaviour. Another challenge was find a way to convey the insider’s – that is the sender’s and the recipient’s- experience of the work. These works then were made with a collective recipient in mind; subscribers to the Netbehaviour mailing list. This is a diverse group of people, artists, musicians, poets, thinkers, programmers (ranging from new-comers to old-hands) with varying familiarity with and interest in different aspects of netiquette and the rules of exchange and collaboration. This is reflected in the range of approaches, interactions and content produced. Before DIWO, extensive press releases were posted to different email lists, and online art platforms to join the Netbehaviour list to collaborate on the project.

(Lem Pollocked. By Lem Urtastik 16/2/07 / Created using Jackson Pollock artware by Miletos Manetas)

As with our previous experience of collective media arts ventures such as the first round of NODE.London Season of Media Arts (2006) [21] “we saw that lots of people invested with most enthusiasm in unstructured discourse; meandering and complex. This gave all participants a partial but meaningful view of the diverse contexts in which we worked, allowing us to make decisions about what our contribution could be. These many-to-many deep processes are never efficient but still invaluable to us in a culture where the pressures are always to be newer, faster, better-oiled, less philosophical, less human (ie less messy and complicated), more productive in the service of strategic overview.” (Garrett and Catlow) [ibid]

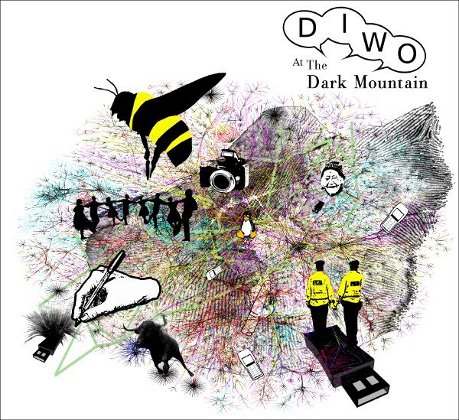

The next DIWO took place in 2009. It was called ‘Do It With Others (DIWO) at the Dark Mountain’. It was a collaboration between the then, newly formed ‘The Dark Mountain Project’, [22] Furtherfield and those participating in DIWO. A Dark Mountain manifesto grew out of a conversation between Paul Kingsnorth and Douglad Hine. It was an invitation to a new cultural response to the converging crises of climate change, resource scarcity and economic instability.

Paul Kingsnorth, in a letter to George Monbiot in the Guardian Newspaper which was also (openly) published by Monbiot said “As for saving the planet – what are we really trying to save, as we scrabble around planting turbines on mountains and shouting at ministers, is not the planet but our attachment to the western material culture, which we cannot imagine living without.” [23] The Dark Mountain Project wrote their Manifesto ‘UNCIVILISATION: the dark mountain manifesto’ “Old gods are rearing their heads, and old answers: revolution, war, ethnic strife. Politics as we have known it totters, like the machine it was built to sustain. In its place could easily arise something more elemental, with a dark heart.” [24] (DMP 2009)

The Dark Mountain Project has been viewed by many as apocalyptic, yet it also has grown in popularity these last few years. When discussing the project Hine says “Rather than treating these as distinct problems in need of technical solutions, we argued that they should be treated as symptoms of a deeper social and cultural crisis, a failure of the stories we have been telling ourselves for generations.” The Dark Mountain Project text was “addressed to other writers, and there is still a vein of Dark Mountain which is about finding new ways of writing, adequate to the times we are living through.” [25] (Hine 2009)

Kingsnorth and Hine both come from a literary background. Asking people to get involved in the project was a big ask.

DIWO E-Mail Art contributors in 2007 included: //indira, [–lo_y-], aabrahams, Alan Sondheim, Alexandra Reill, Allan Revich, Ana Valdes, Andre SC, Andrej Tisma, Ant Scott, arc.xolotl ARN, Aurlea, biodollsmouse, Bjorn Eriksson, Bjorn Magnhildoen, Blackmail, bob catchpole, bobig, brian@netart.org.uy, Camille Baker, Chris Fraser, Christphe Bruno, Clive McCarthy, cont3xt.net, Corrado Morgana, Daniel C. Boyer, dave miller, Denisa Kera, Dion Laurent, Eric Dymond, Edward Picot, Frederick Lesage, Geert Dekkers, Giles Askham, Giselle Beiguelman, Gregorios Pharmakis, Hans Bernhard, Helen Varley Jamieson, Hight, James Morris, janedapain, Jon Thomson, Jonathon Keats, Kanarinka, Kate Southworth, Lance W, Lauren A Wright, lem urtastic, Lewis LaCook, Lisa, Lizzie Hughes, Lorna Collins, Lucille C, Marc Garrett, Marc Cooley, Maria Chatzichristodoulou, mez breeze, Michael Szpakowski, Msdm, Neil Jenkins, patrick lichty, Paul Trevor, Regina Pinto, Riccardo Mantelli, Richard Osborne, rich white, Rosangela Aparecide da conceicao, Ruth Catlow, Sachiko Hayashi, Severn, Sim Gishel, Spread, Susana Mendes Silva, Taylor Nuttall, The Subversive Artist, Turbulence, Wolfgang, xavier cahen, zea.

There’s a splendid exhibition currently on at Manchester’s Cornerhouse. Entitled Subversion, it presents a selection of artworks, a good number of which are moving image pieces, from various artists who are united by a strong connection to the Arabic speaking world. We’re already in loaded territory, for all sorts of obvious reasons. Those reasons could give rise to a long discussion which I’m not going to approach directly here, instead simply quoting a programmatic statement from Glaswegian Egyptian-Turkish writer Omar Kholeif, the show’s curator:

‘Like many of the artists I was looking at, I felt that collectively curators and writers associated with the politically unstable Arab world were being asked to step up and perform to an identity that the world wanted us to play. With Subversion my aim was to do just the opposite. I worked with artists who referenced this very language but who wanted to dissent, poke fun, critique and re-define themselves as artists of the imagination, and not of any specific social or political condition.’

And, in case you’re wondering, he succeeds richly in this aim and, I think, more.

If you can get to Manchester with at least a couple of hours to spare before 5th June your life will be enriched thereby.

I’ve already written a short piece on the show, with a couple of video clips, on DVblog and I’ll be writing a longer review, including consideration of some of the thornier question alluded to above, for MIRAJ 4, out in June 2013.

What I’d like to do here is to look in some detail at one particular piece from the show, a short video by Khaled Hafez. I don’t mean to suggest that it is somehow best in show although I do love it – the show is too diverse for that kind of simple-mindedness. I do think a careful examination of it will yield support for Kholeif’s position. What we have here is a complex work of art, which bears repeated viewing, which doesn’t bend or break but thrives under that hard scrutiny and which, although inevitably stamped with the experiences, background, the moment in time, the physical location of its creator – what isn’t! – is universal (Problematic term! Of course we can’t know what 100 years will make of it but we can assert its current universality and adduce evidence that it is a work which promises to be of some long-term interest too.)

Hafez is probably better known as a painter of striking mash-ups of ancient Egyptian gods, comic book heroes, bodybuilders and models set against richly textured, feverishly beautiful and largely non-perspectival landscapes of the imagination. His paintings are characterised not only by this content (and of course what we lose in a run down of content is the aftermath of the act of painting, facture’s narrative, the play of line, geometry and colour. I’ve seen none of his pieces ‘in the paint’ but I’d bet money they’re good enough to eat.)

Furthermore, series, numbers, line-ups, multiples and queues of those Gods, comic book figures, bodybuilders and hybrids thereof seem to be important to him (and I don’t think I’m wrong in perceiving an echo of hieroglyphs and their implied grid and of pre-Arabic Egyptian art too).

There’s a strong sense of directionality and of motion arising from these lines and groupings and even if one knew none of the background it wouldn’t be surprising to learn of Hafez’s deep interest in moving image.

OK – to the piece itself. Let’s stay zoomed-out for a while and point out first that it was made in 2009, two years prior to the revolution which brought down Hosni Mubarak, exemplifying the ‘storm petrel’ effect whereby artists, who can often be infuriatingly ditzy as politicos, nonetheless, in virtue of their trade – their looking, their seeing, their empathy, empathy often of a strangely disinterested variety except for the can-I-make-art-from-it question, which question perhaps even makes their antennae the sharper, their sensitivity to society’s emotional weather, their readiness to make apparently random or intuitive connections – can be uncannily prescient about impending social change. Artists often ‘get it’ before the key actors begin to have the confidence to move.

So, you need to know that the piece contains so much reference to social conflict that, at first sight, to the outsider at least, it could have been made in the last year.

We start in darkness. Titles: “Anubis productions presents”. A number of soundtracks sewn together in a kind of faux short wave radio polyphony which resolves to a solo piano playing something doomily romantic which I don’t recognise (on subsequent listening it appears to be of a piece with the up-tempo stuff that follows, so I assume it’s especially composed). Over this we hear an extract from the resignation speech given by General Gamal Abdel Nasser in the immediate aftermath of the defeat in the six day war against Israel in June 1967. (He resigned for a day, coming back to office surfing a wave of popular support and grief and then ruling until his death in 1970).

I presume that to quote Nasser is a potent gesture in Egypt. I assume, despite any criticisms anyone might make of him he carries a ‘father of the nation’ type weight and that an allegorical comparison between him and Mubarak would come naturally – here is a flawed but somehow heroic figure, indubitably at the least a genuine anti-imperialist – offering his resignation, but, now, in stark contrast, his pale epigone, his inheritor as dictator but not as hero, clings grimly on by force and brutality and mired in sleaze.

The audio continues and we see more titles:

“The A77A Project (On Presidents and Superheroes)”

Hmm – presidents. In the plural.

Also: you don’t strictly need to know this, but it was gleefully explained to me by the artist that A77A is Egyptian blogger ‘slang’ in that it represents Arabic characters difficult to transliterate directly to Roman for the Arabic word for ‘Fuck’. Of which more soon.

The next thing we see is a detail of the lower centre of a painting by Hafez from the previous year, “Outside Temples”. We focus in on three figures seen in profile. They are almost identical except that whereas the two outer ones have the jackal heads of Anubis the central one wears… a Batman mask. They stand in profile, in body builder pose, right arms raised above and in front of the head forming a sinuous S curve to mirroring left arms behind the lower back.

We zoom into these figures as music changes to a metronomically regular disco drum and cymbal rhythm and the two rightmost figures ‘detach’ themselves from their background and walk forward out of frame to the right.

This detaching happens five times – series in time as well as space.

Three sets only of the figures then parade past us with the arms that had been set in the raised arm pose pumping up and down (crudely animated by pivoting at the shoulder, a similar device setting the legs in motion) in what I surmise is an offensive gesture. It is certainly charged with a raw and vulgar vigour. At this point the figures march against a plain white field – slowing the piece down reveals stray blocks of pixels generated in the animation process. This lack of polish, the retention of rougher edges, feels like a Brechtian distancing. It certainly helped to sharpen my attention as well as endowing the piece with a kind of elephantine grace.

We move to a landscape, I’m guessing a poorer or outlying area of Cairo, with a building site before us. Two of the figures continue their rightwards motion across the frame. They loom large against the background and even allowing for distance, dwarf the human figures behind them. Interestingly the background imagery appears to have been shot from a vehicle moving across the frame to the left, which further cranks up the energy level.

We cut to a 3D software generated mannequin walking in the same direction in a similar landscape. The two painted figures catch up and merge with it – by the somewhat clunky use of a split screen – giving birth to a single Anubis headed mannequin who is our protagonist for the rest of the piece.

The figure continues into a landscape dominated by a still of the Sphinx of Giza, ( Abū al Hūl, in Arabic, translating into English as The Terrifying One) which, in a move straight from Terry Gilliam, picks up the next words of the Nasser speech, ‘mouthing’ with a detached and hinged lower jaw . In the background, the ‘sky’ – in fact simply the background where the image has been cut out in Photoshop – cycles through various colours from a fierce red through multiple greys to black. As you might have surmised realism is not the key term here… except…except …there is a kind of higher realism going on… A pastiche of the stuttering effect so overused in popular music in the early days of sampling is applied to the ends of words in the speech – and here, in Nasser’s Arabic translated as ‘I decided to step down’, the bloggers’ A77A appears, repeated and repeated, a splendidly childish and satisfying equivalent to shouting ‘Fuck! Fuck! Fuck! Fuck! Fuck! Fuck! Fuck! Fuck!’

From now to the end every background image is a still and our Anubis – visitor from another realm, mostly an observer, bemused God in a world gone insane, who intervenes only once and then as a kind of trickster, stepping backwards to change a banner in English reading “Presidential Elections” to “Presidential Erections” ( and then the Arabic banner too – Hafez told me that, strangely, a small change will accomplish precsely the same transformation in both languages) but who pauses politely to allow a photographer to snap five women with cheesy shutter noise and all – processes inexorably rightwards through a number of frames of varying character: some, surreal collage: a man on a bike with a wheelbarrow on his head; some whose strangeness arises from a sophisticated deployment of the warped perspective arising from the lo-fi animation technique – another man-on-bike whose movement at an apparent 70 degrees ‘through’ the frame emphatically underlines the constructed nature of what we are watching followed by a subtle but delicious section where the background image is smaller than full frame size and Anubis steps decorously up into and then down out of it; some, more serious – confrontations between demonstrators and riot police, with the arm-pivot device once again deployed to enable a middle aged women make our putative vulgar gesture repeatedly to the cops.

Anubis finally vanishes into what I take to be a polling booth.

This is such a rich work. It is both enormously local and particular and at the same time hugely general. It is full of ‘content’ but at the same time driven by smart, knowing and dextrously deployed formal devices, which reside not in the background but near to the surface and greatly add to the pleasures of the piece, which presents weighty and serious matters, but does so with great geniality, a geniality and humanity I for one wish to firmly identify with the awakening oppressed as they genially, but definitively and unsentimentally, sweep aside and settle accounts with their former oppressors.

—–

This review is a collaboration between Furtherfield and DVBlog.

Watch the film on the DVBlog website

Sign up: ale[at]furtherfield.org

To accompany Invisible Forces, Furtherfield invites all gallery visitors to take part in a programme of public play, games, making and discussion led by alert and energetic artists, techies, makers and thinkers: Class Wargames, The Hexists, Dave Miller, Olga P Massanet and Thomas Aston.

Saturday 23 June 2012 – 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames and Kimathi Donkor

Saturday 30 June 2012 – 1-5pm

Summer Board Games and Picnic with Class Wargames

Wednesday 04 July 2012 – 9-11am

3 Keys – The River Oracle – The Hexists

as part of Moving Forest by AKA The Castle

Wednesday 11 July 2012 – 11-5pm

Technologies of Attunement – Olga P Massanet and Thomas Cade Aston

Saturday 21 July 2012 – 2-5pm

Dave Miller’s Finsbury Park Radiation Walk

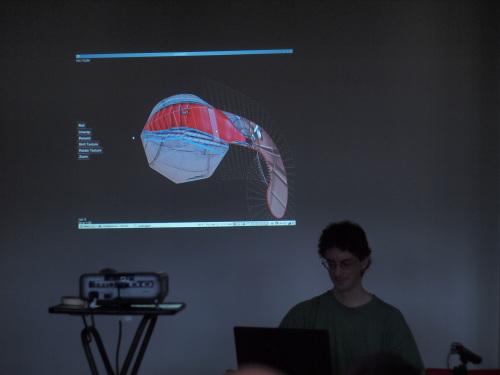

Featured image: Artist Suguru Goto discusses his work.

London 2012: there is of course one event which springs to mind when we think about this city and the year we’re in, but there is also another significant event happening in London right now, one which is very important for the digital and media arts world. It is the year that Watermans Arts Centre is holding the International Festival of Digital Art 2012.

As well as showcasing an array of digital art by internationally renowned artists, the programme also offers the opportunity for members of the public to get involved in discussions around themes that the Festival touches on through the seminar series accompanying the shows. These are in collaboration with Goldsmiths, University of London. Nearly three months in, the Festival has launched two exciting shows,Cymatics by Suguru Goto and UNITY by One-Room Shack Collective.

The first show, Cymatics, is a kinetic sound and sculpture installation that expresses Goto’s vision of nature. To enter it, the audience step through a door into a boxed, dark room within which they are presented with a touch screen interface, a shallow metal tank holding water and a screen showing a video feed of the water in the tank. The piece invites the audience to move the water in the tank by manipulating sound waves via an interactive screen. The result of the interaction is a stunning variety of geometric shapes, demonstrating the distortion that sound waves can have on a substance. This occurrence reveals the bridge between technology and nature, which fits into Goto’s re-occurring theme within his work of the relationship between man and machine.

The seminar which coincided with the show, Interactivity and Audience Engagement, was chaired by Régine Debatty and featured on the panel Tine Bech, Graeme Crowley and Tom Keene, all who which explore audience engagement in different ways within their work. Tine Bech is a visual artist and researcher whose installations invite audiences to engage in playful interactions, from chasing a motion reactive spotlight in Catch Me Nowto sound triggering shoes in Mememe. Tom Keene is an artist technologist whose focus intersects participation, communication and technology. His work is multidisciplinary, investigating the way we communicate, mediated by technology. His practice is diverse, from exploring the potential relationships between networked everyday objects in Aristotles Office to inviting a community to comment on their local issues through signs in Sign X Here. Graeme Crowley is a designer and artist who has created installations for prominent public areas, including The Wall of Light, commissioned by Arrowcroft Plc for the centre of Coventry and Spiral/Bloom commissioned for a hospital in Rochford by the NHS.

I found the juxtaposition of these three practitioners very interesting as each of them explore the interaction between audience and technology in varying ways. Bech’s work is very tactile and sculptural, almost making people forget the technology behind it. She likes to look at technology as something we can mould and which can be used to explore the wider issues which art can bring up, rather than just focussing on the tech itself and how ‘shiny’ (to use her own term) it is. In contrast to this, within Keene’s practice technology feels very prominent, visually as well as conceptually. Crowley’s focus is different again as it mostly operates within the commercial sphere. It therefore is produced for greater public consumption and needs to withstand being a permanent exhibit, becoming part of the architecture it is planted on rather than something which is temporary. The talks given by each panel member and discussions which accompanied them were all diverse and brought up interesting points around the idea of audience engagement and interactivity. Members of the audience entered into these discussions with ease, creating an open dialogue which itself was participatory and engaging.

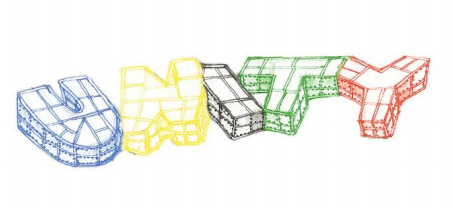

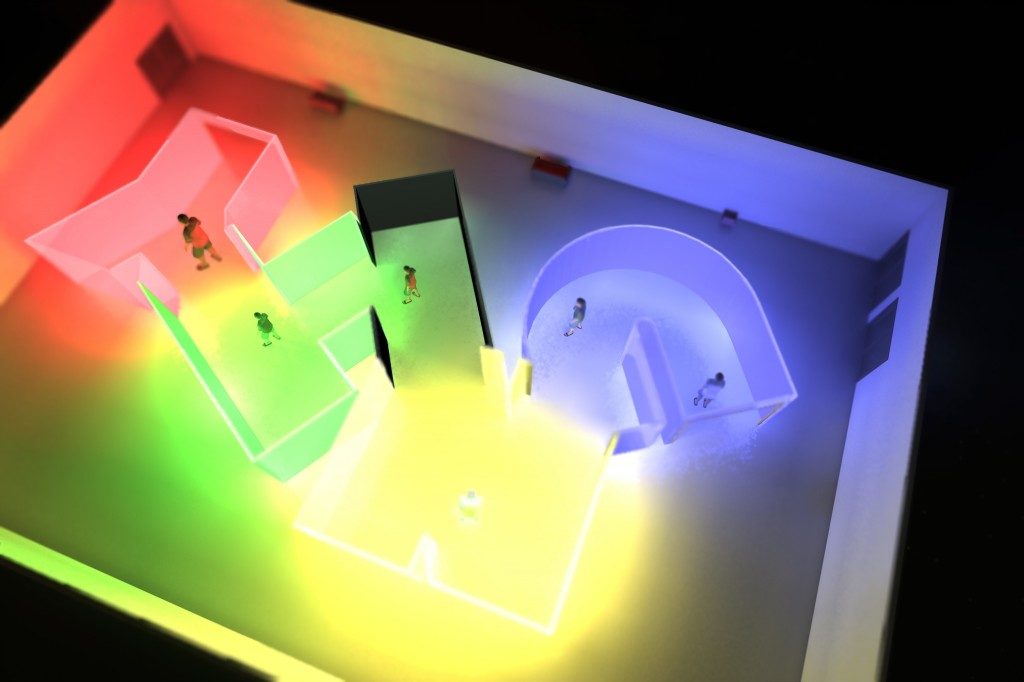

UNITY, by One Room Shack is the current exhibit as part of the International Festival of Digital Art 2012, bringing a piece of work to the gallery which aims to embody the Olympic spirit, visually as well as conceptually.

Design for Unity

The installation takes the form of a transparent maze, angular in its structure and illuminated with different coloured LED lights in each section. Each illuminated section of the structure forms a different letter, all together spelling the word ‘unity’. As the audience navigate their way through the installation, their movement is picked up by motion sensors, triggering the LEDs at each point to turn on. These each represent a particular colour of the Olympic rings.

The ideologies of the Olympic Games linked with an immersive space explores the value of ‘being together’, something which the African humanist philosophy Ubuntu also speaks about.

UNITY is effective in exploring the theoretical concepts embedded within it through a playful and simple interactive structure. As an individual you step from section to section with the different groups of LEDs individually illuminating you as you go through the work. When a group of people interact with the piece at the same time however, the piece lights up as a whole, echoing the values of being together that UNITY invites us to explore. It is through enabling this experience, that the work celebrates and explores human connections.

I do find it interesting how the piece has such a strong stance towards the more idealistic ideologies of the Olympics, especially when taking into account the anti Olympics sentiment present in London. The event does bring people together, but unfortunately as we’ve seen in East London and also at previous Olympic locations across the globe, they also have the ability to put local communities at risk through rising rents and eviction [1]. UNITY looks at ‘…understanding the implication of UNITY on humanism in a neo-liberal world where hyper-capitalism and love of excess trump compassion and selflessness.’ [2] but in reality, the Olympics have unfortunately become something which arguably embody these traits. This said, I do think that UNITY is an incredibly beautiful piece in its visual execution and that its interaction compliments the theoretical idea which it is looking to address.

I look forward to the remainder of the International Festival of Digital Art 2012 and the eclectic ideas within media and digital art which the programme explores. I interviewed Irini Papadimitriou, Head of New Media Arts Development at Watermans, about the Festival:

Emilie Giles: First of all, can you tell us what the premise is behind the International Festival of Digital Art 2012?

Irini Papadimitriou: The idea behind the Festival started from a decision to develop a series of shows that could form a discussion rather than being one-off exhibitions and help engage more people in the programme. In the last year we have been focusing more in participatory and/or interactive installations so I thought it’d be interesting to dedicate this project and discussions in exploring more ideas behind media artworks that invite audience engagement as a way of understanding our work in the past year.

Since this was going to take place in 2012 we felt it would be necessary to open this up to international artists so this is how the open call for submissions came up last year. We received so many great proposals it’s been very hard to reach the final selection, but at the same time the opportunity of having a year-long festival meant we could involve as many people as possible and hear many voices not only through the exhibitions (this is just one part of the Festival) but also with other parallel events such as the discussions, presentations of work in progress by younger artists and students, the publication, a Dorkboat (coming up in June with Alan Turing celebrations), as well as collaborations with other organisations or artists’ networks and online.

EG: Touching on your last answer, the Festival has a clear aim then to engage people in discussion rather than just being viewers of a show. Do you think that within media and digital art there is a particular need for this approach?

IP: I think that hearing people’s thoughts and responses and enabling discussion is important for all exhibitions and art events but specifically for the Festival (since the aim is to question & explore audience participation). It was very relevant to hear ideas and views from other artists, technologists, practitioners etc but also audiences, rather than just the participating artists.

Also, and this is my view, I think as media and digital art use technologies that many of us are not particularly familiar with or if we use technologies it will be most probably as consumers, it’s important to talk about and discuss the process (as well as impact of technologies) both for the artists as well as for audiences.

EG: The themes chosen for the programme are diverse and each relevant to media and digital art in their own way. What are the reasons for each focus and why?

IP: The themes explored in the Festival result mainly from the selected proposals and discussions with the artists. There were so many things to talk about so having these themes was a way to start from somewhere and help understand better the installations shown throughout the year. The seminars that we are organising are an opportunity for the artists to talk about their work and share their ideas with both audiences but also with other artists invited to take part in the panels. It is also a way of discussing these themes and presenting other work that raises similar issues. The seminars are shaped around the themes such as perception and magic in digital art, sound and gesture, geographies, virtual spaces as artistic mediums and of course participation and interaction. We are currently working on a publication with Leonardo Electronic Almanac which will be coming out in the next couple of months and will include essays from artists, academics and students as well as interviews with the artists behind the selected proposals. Again the catalogue has the Festival themes as a starting point but we tried to combine different content and ways of communicating these.

EG: How do the pieces featured in the exhibition question audience engagement, participation and accessibility ?

IP: The artists presenting work are exploring participation and audience engagement in different ways and I think we will have also interesting outcomes from the seminars and the publication which will allow us to explore these ideas further.

In the current installation, UNITY, One Room Shack collective are using the playful structure of a maze (in the form of the word UNITY with each letter lighting up in the colours of the Olympic rings) inviting people to walk inside to reflect and draw upon the complex nature of human reality and ‘difficult’ aspects of human existence.

Michele Barker and Anna Munster who will be showing HokusPokus later on are interested in exploring how we perceive actively in relation to our environment, how we see, what we see and how this makes us ‘interact’. HokusPokus inspired from neuroscience examines illusionistic and performative aspects of magic to explore human perception, movement and senses. The tricks shown in HokusPokus have not been digitally manipulated; they will unfold temporally and spatially, amplifying and intensifying aspects of close-up magic such as the flourish and sleight of hand.

The Festival will close with an installation by American artist Joseph Farbrook, Strata-Caster, which was created in Second Life mirroring the physical world, exploring positions of power, ownership, identity and drawing parallels between virtual and physical worlds. An interesting and important part of the installation is the use of a wheelchair by visitors to enter and navigate Strata-Caster.

EG: How have the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games inspired the Watermans International Festival of Digital Art?

IP: As we are trying to explore what participation is we thought it would be an interesting link (rather than inspiration) between the Festival and the Games/Cultural Olympiad since they are meant to symbolise, promote and inspire values like creativity, collaboration, participation, engagement etc. The Festival isn’t about the Olympics and participating artists didn’t have to propose work that linked to the Games, but we did receive many proposals that reflected on the Games, what they represent and the meaning of participation, so some of these proposals are being shown as part of the Festival, such as One Room Shack’s UNITY and Gail Pearce’s Going with the Flow.

How can designers and programmers work more harmoniously? How can the tools being created better meet the needs of users? There is a need for designers to have a greater role in the production of the tools that they use, aside from just reporting bugs, requesting features or designing logos for open source projects. This is where the Libre Graphics Research Unit comes in. The Libre Graphics Research Unit (LGRU) is a traveling lab where new ideas for creative tools are developed. The unit has grand aims, looking to bring aspects of open source software development to artistic practices. The programme, sponsored by many organisations in Europe, is split into four interconnected threads:

The first meeting, Networked Graphics, took place in Rotterdam from 7-10 December, 2011 and was Hosted by WORM. This second meeting, Co-Position, for which I was present, took place at venues across Brussels from 22-25 February 2012. Co-Position is described by LGRU as:

[…] an attempt to re-imagine lay-out from scratch. We will analyse the history of lay-out (from moveable type to compositing engines) in order to better understand how relations between workflow, material and media have been coded into our tools. We will look at emerging software for doing lay-out differently, but most importantly we want to sketch ideas for tools that combine elements of canvas editing, dynamic lay-out, networked lay-out, web-to-print and Print on Demand.

The meeting saw the coming together of many international artists, theorists and developers for four days of work around this subject. As some of the sessions of the meeting took place simultaneously I’m unable to give a full synopsis of the event. Instead, what is presented below are some of the key issues raised at the meeting.

The subject of copyright cannot be avoided when discussing digital art and collaborative practices. There is a definite need to foster a safe and welcoming environment for artists and designers to produce, share and remix their work. Licensing of artwork under Copyleft licences – such as Creative Commons – helps to create this environment.

In his presentation, entitled “Libre Workflows – A Tragedy In 3 Acts”, Aymeric Mansoux was quick to point out that Creative Commons licences do not cover the source of the artwork. To put it into context, a JPG is covered by a Creative Commons licence but is the XCF/PSD file? Mansoux also considered what is actually a finished piece of artwork? In a remix culture is an artwork ever finished? Mansoux refers to this quote from Michael Szpakowski for further elaboration:

I’ve found it helpful to think of any artwork, be it literary, visual art or music as a kind of fuzzy four dimensional manifold. So the “complete” artwork is the sum of all its instances in time, and all epiphenomena. The entire artwork, seen this way, is a real and precisely enumerable sum, a concrete, not imaginary, set, which could be knowable in its entirety by something long lived and far seeing enough.

From their home town of Porto, Portugal, Ana Carvalho and Ricardo Lafuente produce Libre Graphics Magazine with ginger coons who is based in Toronto, Canada. For the production of the magazine they use Git, with their repository being hosted on Gitorious. As a tool for sharing files between collaborators Git is very useful. However, they explained that they feel they are not making effective use of all that Git has to offer. Part of this comes from the complexity of using Git. There are more than 140 commands in Git, each with their own unique function. These are usually entered via the command-line, but there are a number of programs with a Graphical User Interface (GUI) available. Programs with a GUI are usually favoured over command-line programs as they remove some of the complexity. Carvalho and Lafuente have found, however, that many of of these GUI programs simply replace commands with buttons, which doesn’t remove any of the complexity in using Git. What is needed is an easy to use specialised tool for the production of art.

In this work session, presented by Ana Carvalho and Eric Schrijver, the work group imagined how to adapt existing version control tools to meet the needs of artists and designers. The session began by taking a look at how people currently implement version control. A common practice is to manually make backups, renaming files to differentiate between stages. This can be an effective way of making different versions, but it doesn’t address other issues such as making comparisons or merging changes. The ineffectiveness of these manual methods is soon very apparent. The work group was introduced to the Open Source Publishing (OSP) Visual Repository viewer, which begins to respond to some problems with current version control systems by providing thumbnails of files in a repository.

Using this as a basis we began to look at other functions that the OSP Visual Repository viewer should have, such as the ability to compare graphical files in different ways and to revert back to previous versions or merge versions. Although there was no time to produce working code we did seek to address the complex task of merging and comparing not only the ouput file but also the working files (svg/xcf/psd).

Every good work of software starts by scratching a developer’s personal itch.

This quote from The Cathedral and the Bazaar by Eric Steve Raymond could not be more accurate in describing the motivations behind the development of Laidout, developed by Tom Lechner, a comic artist from Portland, Oregon. Perhaps one of the most impressive software demonstrations of LGRU, Laidout is a program for laying out artwork on pages with any number of folds, which don’t even have to be rectangular.

In an attempt to devise new tags that can be added to the SVG specification, Michael Murtaugh and Stephanie Villayphiou presented a work session that looked at the different ways language is interpreted by both humans and computers. To address this the work group took part in a task that saw them act as an interpreter of commands. With nothing more than a list of tags used in SVG files the work group would attempt to construct shapes.

The results varied from person to person and highlighted an important question: How can computers interpret ambiguity

Using the Richard A Bolt “Put that there” demonstration, Murtaugh showed how human-computer interaction is still based around using very clear, unambiguous commands that can be easily interpreted by computers. In SVG only the most basic of shapes – rectangles, circles and lines – are represented. But, as the work group participants asked, could there be tags to represent more complex shapes, such as a horse?

On the final day of the meeting I took part in a roundtable discussion, chaired by Angela Plohman and featuring myself, Stephanie Vilayphiou, Camille Bissuel and Ana Carvalho. The discussion first went over all that we had achieved over the four days at the meeting, and then the discussion focused on how and why we share our artwork. Expanding on the earlier quote from Szpakowski, how can we make sharing all of our artwork – including the early stages and inspirations behind it – an easier and integrated part of making artwork? In addition to sharing our final, “finished” artworks do we want to also share our processes and ideas behind the artwork? More importantly, can software easily aid this?

Other topics debated in the discussion revolved around opening up our artwork and processes to others. By opening up the development process of our artwork do we do so to invite collaborators and contributions or just observers? The Blender Open projects, for example, are highly regarded as an example of the work that can be made using open source software. The files used to make these projects are are released upon completion of the project, but the development process remains closed to the team of artists and developers. Would opening up this process to contributors add any value or could having too many ideas dilute the original vision of the project.

Although no conclusions around these topics were made, it was nonetheless important for everyone at the meeting to think critically about their practice

A concern of mine is that research is not always acted up on and exciting possibilities exist only as theory. However, I feel that the approach of Libre Graphics Research Unit, which combines research and practice, will ensure that the work undertaken at the meetings is implemented. It is actively working with developers and users to try and create solutions.

At the Co-Poistion meeting not one final product was made, but the initial vision for the future of layout was formed.

The next meeting, Piksels and Lines, takes place in Bergen, Norway and is organised by Piksel.

“It is not accidental that at a point in history when hierarchical power and manipulation have reached their most threatening proportions, the very concepts of hierarchy, power and manipulation come into question. The challenge to these concepts comes from a redsicovery of the importance of spontaneity – a rediscovery nourished by ecology, by a heightened conception of self-development, and by a new understanding of the revolutionary process in society.” Murray Bookchin. Post-scarcity and Anarchism (1968).

The rise of neo-liberalism as a hegemonic mode of discourse, infiltrates every aspect of our social lives. Its exponential growth has been helped by gate-keepers of top-down orientated alliances; holding key positions of power and considerable wealth and influence. Educational, collective and social institutions have been dismantled, especially community groups and organisations sharing values associated with social needs in the public realm. [1] Bourdieu.

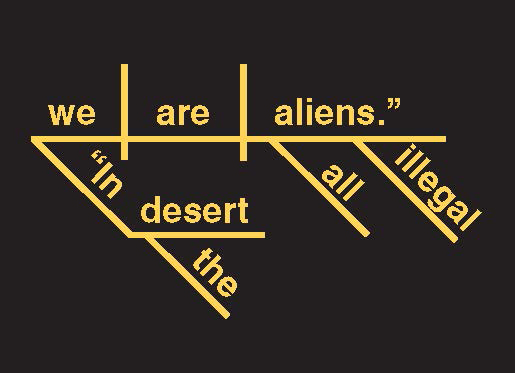

In this networked society, there are controversies and battles taking place all of the time. Battles between corporations, nation states and those who wish to preserve and expand their individual and collective freedoms. Hacktivist Artists work with technology to explore how to develop their critical and imaginative practice in ways that exist beyond traditional frameworks of art establishment and its traditions. This article highlights a small selection of artists and collaborative groups, whose work is linked by an imaginative use of technology in order to critique and intervene into the opressive effects of political and social borders.

In June 2000, Richard Stallman [2] when visiting Korea, illustrated the meaning of the word ‘Hacker’ in a fun way. When at lunch with some GNU [3] fans a waitress placed 6 chopsticks in front of him. Of course he knew they were meant for three people but he found it amusing to find another way to use them. Stallman managed to use three in his right hand and then successfully pick up a piece of food placing it into in his mouth.

“It didn’t become easy—for practical purposes, using two chopsticks is completely superior. But precisely because using three in one hand is hard and ordinarily never thought of, it has “hack value”, as my lunch companions immediately recognized. Playfully doing something difficult, whether useful or not, that is hacking.” [4] Stallman

The word ‘hacker’ has been loosely appropriated and compressed for the sound-bite language of film, tv and newspapers. These commercial outlets hungry for sensational stories have misrepresented hacker culture creating mythic heroes and anti-heroes in order to amaze and shock an unaware, mediated public. Yet, at the same time hackers or ‘crackers’ have exploited this mythology to get their own agendas across. Before these more confusing times, hacking was considered a less dramatic activity. In the 60s and 70s the hacker realm was dominated by computer nerds, professional programmers and hobbyists.

In contrast to what was considered as negative stereotypes of hackers in the media. Steven Levy [5], in 1984 published Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution [6]. In three parts, he writes about the canonical AI hackers of MIT, the hardware hackers who invented the personal computer industry in Silicon Valley, and the third-generation game hackers in the early 1980s. Yet, in this publication, what has had the most impact on hacker culture and is still used widely as a guideline by many is the ‘hacker ethic’. He identified this Hacker Ethic to be a code of practice consisting of key points such as that “all information is free”, and that this information should be used to “change life for the better”.

1. Access to computers—and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total. Always yield to the Hands-on Imperative!

2. All information should be free.

3. Mistrust authority—promote decentralization.

4. Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race or position.

5. You can create art and beauty on a computer.

6. Computers can change your life for the better.

Levy’s hacker ethic promotes the idea of performing a duty for the common good, an analogy to a modern day ‘Robin Hood'[ibid]. Proposing the concept that hackers are self-reliant whilst embracing a ‘healthy’ anti-authoritarian stance, combined with free and critical thinking. Proposing that hackers should be judged by their ability to hack, and presenting hacking as an art-form. Levy also says that the Free and open source software (FOSS) movement is the descendant of the hacker ethic. However, Levy’s hacker ethic has often been quoted out of context and misunderstood as to refer to hacking as ‘breaking’ into computers. This specifically prescribed role, denies the wider and creative context of what hacking is and could be. It does not have to be just about computer security.

This leads us to ‘crackers’. All crackers hack and all hackers hack. But, crackers are seen as second rate wannabe hackers by the older generation of hackers. The Black Hat Hacker or cracker designs and releases malicious code, gathers dangerous information and brings down sensative systems. The White Hat Hacker hunts down and destroys malicious code, and the casual hacker who hacks in order to learn information for his or her own curiosity; both generally dislike ‘Black Hats’ and ‘Crackers’, and tend to view them as computer criminals and dysfunctional juveniles. Lately, crackers have also been labeled as ‘script kiddies’. As a kind of snobbish insult, it refers to those who are not capable of building or programming their own tools, but tend to use scripts and programs written by others to perform their intrusions. To add to the confusion we also have the term ‘Grey hat’. Which refers to a hacker acting between black hat and white hat. Indeed, this could demonstrate where art hacktivists reside, challenging the trappings of the traditional concept of goody and baddy.

“There is another group of people who loudly call themselves hackers, but aren’t. These are people (mainly adolescent males) who get a kick out of breaking into computers and phreaking the phone system. Real hackers call these people ‘crackers’ and want nothing to do with them.” [7] Raymond.

“The basic difference is this: hackers build things, crackers break them.” [ibid] Raymond.

But before we judge,

let’s view a snippet of the \/\The Conscience of a Hacker/\/ by +++The Mentor+++

Written on January 8, 1986.[8]

“This is our world now… the world of the electron and the switch, the

beauty of the baud. We make use of a service already existing without paying

for what could be dirt-cheap if it wasn’t run by profiteering gluttons, and

you call us criminals. We explore… and you call us criminals. We seek

after knowledge… and you call us criminals. We exist without skin color,

without nationality, without religious bias… and you call us criminals.

You build atomic bombs, you wage wars, you murder, cheat, and lie to us

and try to make us believe it’s for our own good, yet we’re the criminals.”

The term ‘Hacktivism’ was officially coined by techno-culture writer Jason Sack in a piece about media artist Shu Lea Cheang published in InfoNation in 1995. Yet, the Cult of the Dead Cow [9] are also acknowledged as defining the term. The Cult of the Dead Cow are a group of hackers and artists. They say the Hacktivism phrase was originally intended to refer to the development and use of technology to foster human rights and the open exchange of information.

Hacktivism techniques include DoS attacks, website defacement, information theft, and virtual sabotage. Famous examples of hacktivism include the recent knocking out of the PlayStation Network, various assistances to countries participating in the Arab Spring, such as attacks on Tunisian and Egyptian government websites, and attacks on Mastercard and Visa after they ceased to process payments to WikiLeaks.

Hacktivism: a policy of hacking, phreaking or creating technology to achieve a political or social goal.

“Hacktivism is a continually evolving and open process; its tactics and methodology are not static. In this sense no one owns hacktivism – it has no prophet, no gospel and no canonized literature. Hacktivism is a rhizomic, open-source phenomenon.” [10] metac0m.

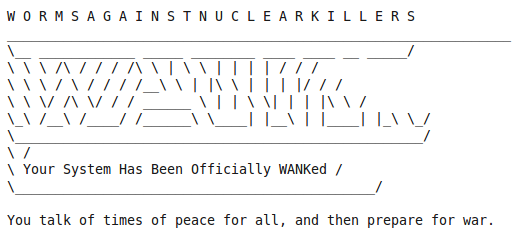

The practice or behaviour of Hacktivism is at least as old as Oct 89 when DOE, HEPNET and SPAN (NASA) connected to (virtual) networked machines world wide. They were penetrated by the anti-nuclear group WANK worm.

WANK penetrated these machines and had their login screens altered to…

HACKING BORDERS: Examples of Art Hacktivism & Cultural Hacking…

“Radical groups are discovering what hackers have always known: Traditional social institutions are more vulnerable in cyberspace than they are in the physical world. And some members of the famously sophomoric hacker underground are becoming motivated by causes other than ego gratification.” [11] Harmon.

Hacktivism, exploits technology and the Internet, experimenting with the immediacy of distributable networks as a playful medium for independent, creative and free expression. There has been a gradual and natural shift from net art (and net.art) into Hacktivism. Net Art in spirit, has never really been just about art being viewed on a web browser alone. Some of the very same artists whose artwork involved being shown in browsers and making code behind the browser as part of the art, have also expanded their practice outside of the browser. One such artist is Danja Vasiliev, “Fifteen years ago WWW was something very new in Russia and besides the new dial-up aesthetics and world-wide means it brought a complete new layer of existence – “netosphere”, which made my youth.” Vasiliev very soon moved on from playing with browsers into a whole new territory. [12]

Danja co-founded media-lab moddr_ in 2007, a joint project at Piet Zwart Institute alumni and WORM Foundation. Based in Rotterdam moddr_ is a place for artists and hackers, engaging with critical forms of media-art practice. He collaborated with Gordan Savicic and Walter Langelaar from the moddr.net lab on the project Web 2.0 Suicide Machine, which lets you delete your social networking profiles and kill your virtual friends, and it also deletes your own profile leaving your profile image replaced by a noose.”The idea of the “Web 2.0 Suicide Machine” is to abandon your virtual life — so you can get your actual life back, Gordan Savicic tells NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly. Savicic is the CEO — which he says stands for “chief euthanasia officer” — of SuicideMachine.org.” [13]

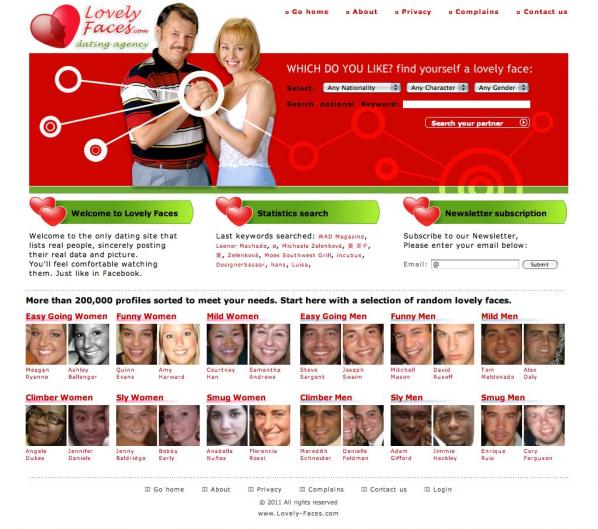

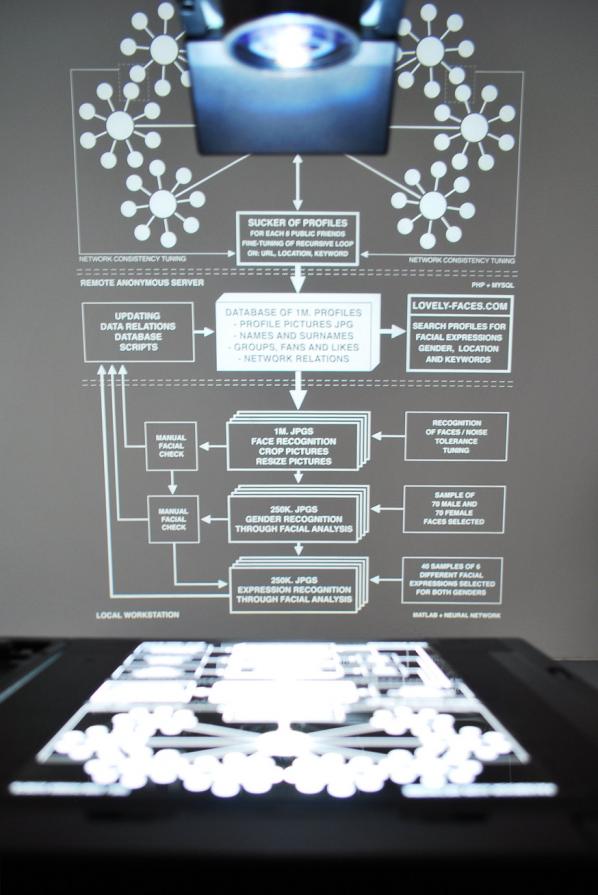

Just like another project called ‘Face to facebook’ that stole 1 million facebook profiles and re-contextualized them on a custom made dating website (lovely-faces.com), set up by Italian artists Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico, whom also just so happens to be editor in chief of Neural magazine. Web 2.0 Suicide Machine, had to close its connections down regarding its Facebook activities after receiving a cease and decease letter from Facebook. [14]

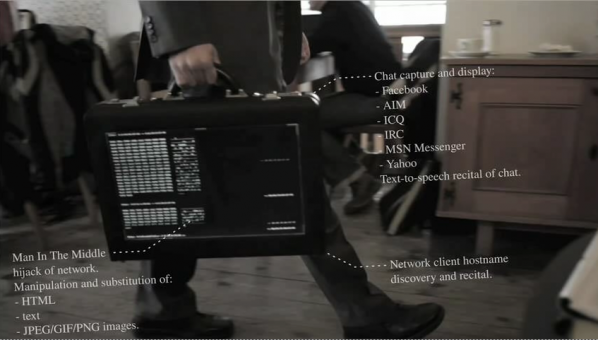

Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev teamed up and formed the mysterious group Men in Grey. The Men In Grey explore our online vulnerabilities by tapping into, intervening into wireless network traffic. Observing, tracing and copying what we do. This hack then redisplays our activities back to us, showing the data of our online interactions.

At first no one (except myself & a few others) knew who they were. When they first arrived on the scene I started an interview with them and then suddenly, I was asked to hold back due to their antics on the Internet and interventions in public environments receiving much coverage. They were not sure how it would pan out for them. Partly due to the anonymous nature of their project, and also because of the sudden impact of the larger hacktivist group Anonymous getting much press in commercial media themselves.

“Men In Grey emerge as a manifestation of Network Anxiety, a fearful apparition in a time of government wiretaps, Facebook spies, Google caches, Internet filters and mandatory ISP logging.” M.I.G