Sam Renseiw and Philip Sanderson’s Lumière & Son project is a near perfect and altogether exhilarating sequence of moving image lyric poetry (though lyric here does not exclude humour or the grotesque) and a demonstration of how seriality and fragment – an unfolding over time, the diaristic – has quietly become one of the fundamental modes brought stage centre by the network (so much more than the rather dull ‘interactive’ which has so quickly become the standby of the monetised digital). Impossible to watch one of these pieces without the desire to watch just one more.

The set (which lives online but has been shown offline in whole and part) and its component pieces, moreover, are studies in various interesting things: the liberating effects of constraint and collaboration and what those both demand and imply; also of randomness, or perhaps better, the loose, the dashed off, differing degrees of accuracy in such collaboration (also the apparently dashed off, the apparently loose [also the apparently synchronised or ordered]).

To start with, a little history. In 2007 two young members of the digerati, Andreas Haugstrup Pedersen and Brittany Shoot, invented a form and threw down a gauntlet. The form, in fairness, was not exactly new – over 100 years old, actually – but its re-contextualisation within the digital realm and more particularly on the network was, without exaggeration, a stroke of genius[1]. It involved taking precisely the constraints affecting the films of the cinema pioneers, the Lumière brothers, and applying these to contemporary online video work. Films or videos of exactly one minute, fixed camera, no sound, no zoom, no edits. Such videos dubbed, naturally, ‘Lumières’. There was clear recent precedent in the constraints of the Dogme movement of Von Trier and others but the project also drew on the various little-bit-art-little-bit-geek, young, playful cultures which abutted and intersected the more formal area which we called, for a while, ‘net-art’, and which thrived on a sparky and often competitive and showy overcoming of the early net’s limitations of file size and bandwidth – projects like 5k.org, 10secondfilm.com spring to mind.

Additionally, because the start of modernism still does not really seem all that far away, early film was a natural reference point for many wrangling the early internet as art tool and channel both.

We responded viscerally to the sheer, almost willed-into-being, expressivity of the ad hoc devices and solutions of early film and this fitted snugly with the bodges we ourselves were employing. It gave us confidence, too, that our ducking and diving too could be expressive but also it confirmed a certain tendency to lo-fi-ness there in the zeitgeist. (I speculate – a lo-fi-ness which helped to define and declare art – useless, beautiful and human – as against the slickness of corporate design, communication and advertising… This has persisted remarkably – note the thriving on-going cult of the animated gif)

That was the form. The challenge – make some. Embrace that 100+ year old limitation and do something engaging with it. Push the form as far as it will go.

Pedersen and Shoot set up a web site where all contributions would be aggregated and indexed (in retrospect, somewhat unfortunately, by links rather than copies held on their server – much work of historical significance has already vanished. Shoot and Pedersen themselves have moved on and the site has a Marie Celeste feel). In addition to the site itself, there was a Lumière manifesto which, personally, I found a little narrowly focussed. Shoot and Pedersen seemed to invoke a near ethical dimension to the return to first principles and in their own moving image practice confined themselves to work (much of it very good) entirely within this discipline. It was clear from the huge response of other artists and film-makers though that the form clearly answered a diverse set of pressing needs. For some it was a cleansing activity, for some a sketchbook, for others a spur to invention and for others still, a challenge in the sense of “How can I observe the spirit of the rules whilst actually driving a coach and horses through them?”

Although the Lumière made next to no impression on the ‘official’ world of art video (one speculates – cynically, perhaps – too democratic and available to anyone with a cheap camera, too ontologically opposed to the expensive grandeur of high concept, too hands-dirty in a world where artists aspire to hire videographers and editors to realise their art; in short, too lacking in the conspicuous consumption that validates much contemporary work), it was enthusiastically taken up by a mixed bag of videobloggers and artists excited by the idea of video specifically made for the net.

An immediate adopter and one of the most enthusiastic and prolific makers of Lumières was the Danish architect, educator and thinker, Thomas Wiesner, who operates in online video as Sam Renseiw and maintains a quirky and engaging site called Spacetwo: Patalab. Renseiw (as he prefers to be known in a video context) is a maker of numerous very singular small video works, which evince his keen interest in space and movement within spaces. (He teaches not only architecture but also a course for dancers involving approaches to conceptualising movement in space). I’m not sure Renseiw completely understands how original his work is. It is characterised by a joy in careful, quizzical looking (and a spontaneity in finding or being gifted subjects for such looking, assisted enormously by the continual development of more portable and discreet video cameras). It is, in terms of the formal art world deeply unfashionable. Personal and diaristic, it eschews the grand concept and extravagant and expensive execution and is all the better for this.

Renseiw has a profound sensitivity to space and to how people and objects move along variously restricted and open trajectories but he is mindful too of what the ‘actors’ in these found scenarios, set out to do and in fact achieve as human beings. The gap between aim and reality provides fertile ground for Renseiw’s dry and humane sense of humour, which is never far distant.

Significantly his prolific Lumière making (337 at the time of writing) sits side by side with longer (though still lapidary) works with music, editing and the other things the Lumière eschews.

Renseiw’s Lumières are characterised by a number of quite distinctive things. Something that unites them all is a quite extraordinarily heightened sensitivity to both colour and composition, which formal feature hits us forcefully in the moments even before we begin to decode any content or action. Formally striking too is the way in which a number of the pieces are composed so to as to allow for action in the near, middle and far distance, sometimes in different sectors of the frame, sometimes simultaneously in a kind of layered visual counterpoint and sometimes spread out temporally. My imputed intentionality here is somewhat problematic, though Renseiw confirmed to me that he shoots much more material than he uses and that he will select a particular minutes worth of material from longer sequences so on two counts there is a rudimentary (though nominally forbidden) editing process occurring. A quick comparison with Lumières by other film-makers will however confirm that Rensiew’s singular vision distinguishes each of his pieces from the off.

Other signatures are extremely low, oblique or occluded camera positions, into the fields of which parts of human bodies mysteriously intrude. This sounds clinical. Curiously it is the opposite. Redeeming it is a genial humour which allows the part to stand for the whole – we perforce imagine the entire human being whilst smiling at the V-effekt with which we are presented – for example a pas de deux for a pair of woman’s black leather boots (on the ends of beyond-the- frame legs) and the four paws of a black dog – randomness, clumsiness, near misses, narrow escapes and – we just know because we are human – purposeful activity. Human life, in short.

Another defining stamp is a musician’s sensitivity to rhythm and tempo – rhythm as manifested both as near metronomic regularity – someone’s gait, traffic flow, a hammer, for example, with either disruptions – slowings down, speedings up, pauses, stutterings – to that regular pattern, or polyrhythms created by other simultaneous independent near regularities and variations therefrom.

There are three loose categories into which Renseiw’s Lumière work could be said to fall (of course they’re by no means entirely mutually exclusive) – we’ll call them the loop-able, the documentary and the performative. The loop-ables are kin to the still photograph, are often of natural phenomena or repetitive but irregular human engendered activity where one could imagine the minute’s imaging infinitely, hypnotically extended – the flashing light patterns in Belisha Code for example. The documentary tag applies where the topic itself might be assumed to have some independent interest, for example the workers transporting away in a sling Copenhagen’s Little Mermaid for a trip to Shanghai’s 2010 expo in Speaking Voice or Michelle Obama’s motorcade in Rite of Passage. In what I’ve called the performative, richest of all in my view, an amazing amount of stuff happens. And everyday stuff happening and rendered vital by keen eye, framing and selection rather than something we might have known to look out for, is key. The differently distanced layers referred to earlier partition the frame physically or the piece temporally and unexpected things happen against and within them. We participate in these dynamically as viewers – we view this strange jigsaw world and complete it mentally; sketch a world beyond which is not simply our lived world but that world somehow leavened with Renseiw’s odd and warm sensibility.

I’ve written pretty glowingly about these Lumières – constrained, silent but surprisingly un-austere and you could well think that to add sound, music or both and several layers of these to boot might be over-egging it all somewhat. So one would think, but I have complimentary things yet to say about skill, tact, panache, flair and sensitivity and they are heading the way of Philip Sanderson, Renseiw’s musical/sound collaborator in the extended Lumière and Son project.

Renseiw’s Lumières are, I hope I’ve established, rich, dense, multi-layered but remarkably uncluttered works. A number of these pieces approach as closely as possibly the condition of music whilst remaining wholly without sound. It might seem superfluous or an act of hubris to add sound to them, the consequence of which could be to render leaden, stiff and fixed what is light, playful, complex and turns on a sixpence.

With the exception of a couple of near misses Philip Sanderson’s sound and music additions triumphantly avoid this trap and indeed deepen those rich and quicksilver qualities.

It’s important to note that what Sanderson contributes is all found or appropriated material – it’s possible he’s added original material in, I don’t know, but it’s not a significant chunk if he has – he certainly reworks much of it intensively, usually in the form of a mix of several layers of sound, some musical, some textual. (And we should note that Sanderson’s wit and deftness is literary as well as musical).

The deployment of sound gains enormously from Sanderson’s huge and eclectic range of knowledge, reference and enthusiasms. There’s a cooking metaphor in here – mixing the ingredients, finding just the right, perhaps almost imperceptibly present flavourings, knowing the qualities of things and how to combine them well…

Elsewhere I have asserted that the key feature of the most successful short form video work is a combination of intense poetic compression with a huge range of suggestion. I called this opening-out – a universe from a speck of dust. An ability to evoke the range of connectedness of many disparate things by well-chosen images, sounds, texts, whatever can pertain to moving image. Certainly Renseiw’s work has this in spades. Sanderson’s sound opens-out the movies still further. It adds, almost literally, an extra dimension, as if enabling new angles of view. It provides paths, bridges, vistas, tunnels, maps, balloons, telescopes, and sonar.

The guiding methodological principle seems to be a species of metonymy and one moreover which suggests an, in practice entirely non-existent, explanatory or illustrative dimension. The flashing beacons in Belisha Code are accompanied by a recording of a numbers station where one’s immediate impulse is to construct entirely absent meaning in the correspondence of the binary on-off of the four beacons and the German numbers from zero to nine heard on the soundtrack. Let’s be clear that this is not a criticism – a rigorous correspondence would be leaden – closed-in – but what we do have is a rich package of suggestion and affect. The correspondence that does exist is formal and temporal, between the flashes of the beacons and the articulation of the words and where the same sort of rickety polyrhythms that we’ve observed within the original Lumières themselves ensue.

Although comparison of some of Sanderson’s sources with their use in the pieces evidences, on occasion, some quite detailed cutting, mending and buffing-up there is an inescapable sense in his deployment of sound of the somewhat aristocratic tradition of the modestly dashed off. It’s partly his clearly extensive knowledge of his sources and his evident skill with a huge variety of genres but it’s also to do with a certain ambiguity in how the sounds are placed – not four square upon, but athwart the images, the sound often only fading or vanishing well after we’re into Renseiw’s end titles. Sometimes the sound is clearly not cut to shape in the way one might at first expect – an introduction, for example proper only to the original sound itself and not to any clear visual motivation might be left standing. The imperfections, noise, oddities and glitches contained within each block of appropriated sound intensify this sense of informality as does the slightly culinary air referred to previously. On the other hand, often enough to matter, the sound directly lines up in a spine tingling way with a particular action. It’s a master class in expressive ambiguity.

Renseiw – physical poetry, the occlusion, constraint. The careful choice of footage (variety and kind of motion within a narrowish range). Humanism: we don’t see faces, we don’t hear voices, we are amused but we recognise ourselves, youth and age &c.

Sanderson: The music found but could have been composed. The artfulness of placing it just thus. We will never know whether the way it ends with the action, the running off, taking place just after the repose of the final minor chord was deliberated or found. For me this placement implies a universe beyond the letterbox. It has a commonality with the treatment of time in many photographs and paintings – this is an instant, a fragment, but there was a before and an after.

Note that there are four beacons. The sound (a numbers station, one can almost track the archaeology of impulse!) draws on the numbers 0-9, in German. It’s worth noting there is no obvious mathematical mapping between the pattern of the beacons and the numbers but the character in sound of the numbers is close to that of the beacons in light. Suggestion, metonymy.

This forces our attention very strongly on that area of the screen, with the concomitant effect that when we force our attention away it is as if our eyes have been suddenly opened. There is a world out there.

There is a hint of the transcendent in the title – how is this realized? Unless we know Denmark it takes a few moments to realize we are on a train rather than a boat or plane – we are clued into this by the close objects we clearly pass at speed and the reflection of passengers and seating in the windows. One speculates that the sound track is comprised of two elements – one the rhythmic and metallic pulse which somehow rhymes with the passing object (a kind of pseudo-diegesis) and the second an (Open University?) lecture on relativity.

Here, not exactly metonymy but something more fragile, delicate chains of suggestion and subtle resonance. No argument (to see an argument in any of this would be to commit a category error) but a complex and suggestive …um…thing. One should also note that this piece (in both its silent and extended versions) is extremely beautiful.

Let’s talk about the sensibility and taste of the makers. Renseiw offers something simple, a kind of tour de force – we perceive it as such although given the fixed camera constraint any virtuosity belongs to the seagull.

A banal seasoning of music would involve simply the seven note modal motif which hails, I’m almost certain, from American popular song of the 70s big country type – Wichita Linesman, you know the sort of thing. (I checked with Sanderson –it’s Bobby Goldsboro’s Summer The First Time) By itself it would be too perfect, too parallel to the floating bird (it seems to give way to a crashing wave sound in its looped form; interestingly the Goldsboro video I found on YouTube begins with a shot of gliding seagulls). With too much parallelism nothing extra arises but Sanderson spices the mixture by the addition of dialogue from what sounds like an American film of the forties or early fifties. It disrupts the idyll but only so as to make us more aware of it. There is a kind of musical V-effekt here (which could have been so badly handled and so isn’t). This is its ‘meaning’ – these things! Here, now!

There is something of the dance about this. The music beautifully picks up both the nervous, sudden gestures of the cook but also suggests the process of cooking itself. The music has a funk component. One might say that it cooks.

Visually – the low angle, the fragmented view of the body, the person here and not here. The focus on that person which permits and invites its opposite, in particular the framing of the sky and trees. The rhyme between the black-booted two legs of the woman and the black four legs of the dog. Their pas de deux. The music here subordinate, properly so. Ambient sounds, on the one hand, with odd vocal snatches on top. The strangeness doesn’t demand our attention because we are so focused on the visual.

Until the last moments we simply hear a fitting (slightly arch) accompaniment to the skating – we surmise that it is intended to pastiche the kind of accompaniments used in professional skating. At the last moment we realize this is exactly what it is, as the commentator’s voice breaks through. There is also a ‘skate’, ‘friction’ or ‘traveling’ noise which exactly underpins the final move we see, just before the humour of the juxtaposed text, which continues after the movie has gone to black, strikes us: “Delightful, skating of the highest quality” delivered in classic plummy BBC tones…

A hugely rich piece: visually there are a number of layers – the far left street background where distant people and vehicles process. The game of Petanque: – the actual participants (although glimpsed corporeally only twice: fleetingly at the very end and as one set of typical Renseiw-y legs) and the balls themselves (and the metonymic link between these and the planets). Thirdly, the large shadows. (And the apparent size of each of these layers allows for very clear visual interaction). Sound – the ‘light’, jokey, playful music. The University Challenge soundtrack, here unusually clearly cut up – questions – astronomy; replies – painters. A risk for Sanderson, but one that works.

A little detective work indicates the level of detailed truffling about by Sanderson – part of the sound, the text, is grabbed from a YouTube video about French patisseries in London and cut up considerably – in particularly yielding the repeated incantation “cream cakes, tarts, macarons” the latter word in a considerably overheated French accent following the sloaney first three, to deeply comic effect. Comic maybe but, repeated, as in a dream; this mood is reinforced by a rather beautiful waltz time solo piano loop of the opening line of The Associates’ Party Fears Too. Here’s another piece where the visuals, here also dreamy and wistful, set in a looking glass Copenhagen (and the disjuncture between the London-location heavy narrative and the visuals is simply ignored, taken for granted, part of the deal), support quite a complex sound assemblage. Utterly haunting and quite difficult to say exactly why.

If one didn’t know it wasn’t one would surely assume this was carefully planned, and our knowledge it was not adds to our pleasure in it. Visually the rhyme between the woman and the near foreground statue is perfect – at one point she seems to mirror it exactly. Maybe she knows the area well and there is some unconscious mental echoing…we’ll never know. The other sharp visual pleasure is the smallness of the area of focussed distant activity, which again feels like a sort of directorial chutzpah, except, except…

Sanderson’s contribution is razor-sharp – the pseudo dialogue hits the mark precisely but doesn’t outstay it’s welcome – or at least there’s other stuff going on to detain us, not least the way the model’s preliminary warm-up shimmy becomes a perfect piece of minimal dance when set against the music.

Right of Passage/Speaking Voice

I wonder if when the content has it’s own ‘documentary’ interest, when the filming becomes a case of “Look at this remarkable thing not because of its intrinsic interest but because it happened”, the final result is somehow less engaging?

Again a dance related piece – the regular beat of the calling of the numbers one to eight sets up an aural grid against with which the implicit rhythms of the movement in, out and across frame interact in a sophisticated but subtle polyrhythm. Part two of the sound, with actual step instructions, ups the tension and the effect (especially the late entering ‘spinning’ man). Note how often in these pieces the sound fades out slightly later than the visuals, over Renseiw’s titles, thus emphasising its separate existence in an independent channel or dimension.

Beautiful found synthesis. Funny. Funny and truthful and touching.

The moving image is packed with incident at both different spatial levels and at different points in the piece. The Portsmouth Sinfonia version of Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy underpins like a grid, as with Square Dance but in a more complex way, the visual rhythms of the film. Enough coincidence of rhythm to feel planned, enough ‘pull outwards’ to feel open… Again humour… Why does the Portsmouth Sinfonia track, in particular, work so well – atmosphere? the conjuring of a sort of raggedy clockwork ? – can we imagine in its place a more conventional rendering of the Tchaikovsky? Yes, but…

Prime example of Sanderson mind set – metonymy, suggestion – the trees are hair, the water appears exactly on cue (worked? Hmm – the audio appears to be cut to make the word ‘rinsing’ and the water jet coincide)

A one liner, but, given its place in the sequence, none the worse for it.

Brass band/Dancers.

*The pieces loosely divide into ones where either sound or vision predominate and some where they have equal roles.

* Not only does dance appear a couple of times explicitly as a subject but the spirit of dance pervades the project.

*The question of the success of individual pieces and of the sequence – a piece that seems less effective in isolation can well form an effective point of relaxation or reflection in the sequence as a whole…

*There are three pieces which, if one ‘re-removed’ the sound, would not strictly be Lumières – Check Out Art Fairs (speeded up), A Beauty Overblown (slowed down) & Sucked In (reversed). Sanderson performed the first two operations for reasons he felt the sound he used demanded. (To which one can only say: yes, this is right, a constraint is there for the sake of art, not art to be constrained.) Sucked In remains a mystery.

*The titles matter (note the re-titling of the composite works). They provide yet another dimension and illumination too.

*The prevailing tone is light, warm and playful. The darker side of life is largely absent, at least explicitly (though there are trails we could pick up to find it). Humour is everywhere. Only a philistine or fool would judge the work as a consequence to be less ambitious, significant or universal.

.re_potemkin is a crowdsourced re-make of the film “Battleship Potemkin”. It is a “.f.reeP_” project by .-_-., part of a series of projects that embrace the ideology and means of production of contemporary media and technoculture in order to make art.

From December 2006 to January 2007 .-_-. worked with 15 groups of students from Yildiz Technical University to reproduce Battleship Potemkin on a shot-by-shot basis. Not all shots were reproduced, there are empty black sections in the new film. The students and the setting of the university and its surrounds are very different from the locations and actors of Battleship Potemkin. The domesticity, institutional backdrops and modern street furniture would be very different from the 1920s Soviet backdrops of the original even if they weren’t in colour.

Soviet film-maker Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” (1925) is a classic of early 20th century cinema, a piece of obvious propaganda that both fulfils and transcends its instrumental purpose with its exceptional aesthetics. Its most famous images have become cultural icons and cliches. If you haven’t seen it then ironically enough it’s on YouTube so you can watch it there and go “oh, that’s where that came from…” before we continue. Or you can watch it in the side-by-side comparison with .re_potmkin on the project’s homepage.

The Soviet dream became (or always was) a nightmare, an ideology that sacrificed many millions of lives in order to maintain its fictions. Our contemporary liberal democratic society regards itself as unquestionably morally superior to communism for this and many other reasons. The (self-)defining difference between Soviet communism and liberal free-market capitalism is economic ideology. Free markets benefit individuals by reducing inefficiencies.

As free market capitalism has triumphed its means of production have evolved. Corporations emerged as a leading way of organizing labour, leading to utopian social projects in the West in the same era as Eisenstein was working in the East and later to a burgeoning middle class in the post-war era. But since then corporations have become increasingly unapologetic exploitative economic projects.

In order to cut costs and become more economically efficient, corporations can become virtual. They shed jobs to reduce payroll and other costs associated with actually employing people. They then source cheaper labour and production from outside, paying other companies to make the branded goods that the corporation sells. This is known as outsourcing.

A logical next step in corporate cost reduction is to source labour from individuals without paying for it at all. This is known as crowdsourcing. Although individuals who donate their labour to a corporation through crowdsourcing might not be compensated monetarily, they can still be compensated in other ways.

With crowdsourced intangible goods the best way of rewarding people who donate their labour to produce those goods is simply to give the resulting product to them under a licence that allows them to use it freely. Non-profit projects such as GNU and Wikipedia do this very successfully, but corporations are always tempted to try and privilege their “ownership” of other people’s work. Where crowdsourced labour is exploited without fair compensation this called sharecropping.

.re_potemkin is a non-profit project rather than a corporation, and as such it has adopted a GNU or Wikipedia-style copyleft licence. Or at least it claims to have. In a creative solution to the fact that there is more than one copyleft licence suitable for cultural works, .re_potemkin’s licence is a kind of meta-copyleft. Checking the licence page reveals that .re_potemkin’s licence is more a licence offer than a licence.

This avoids the politics of imposing a choice between competing copyleft licences on the producers and consumers of the work. The only problem with this approach is that adaptations of the project, works that build upon it, may end up unable to be combined and built on further because they have been placed under incompatible licences. This is unlikely to happen, but it can be very frustrating when it does.

.re_potemkin is crowdsourced equitably, then. And even in its technical form, .re_potemkin is a free and open resource. it is distributed not in a patent-encumbered, proprietary format such as Flash or MP4 but in the Free Software Ogg Vorbis format. Too few artistic projects follow the logic of their principles in this way, instead sacrificing principle to the at best temporary convenience of the proprietary YouTube or QuickTime distribution channels.

The politics of the production of an artwork are only of aesthetic (rather than art historical) interest if they intrude into the finished artwork. A crowdsourced artwork such as the Sheep Exchange is about crowdsourcing as well as being made by it. The aesthetic of that work (many differently styled drawings of sheep) raises the question of how and why it was produced and this feeds back into the aesthetic experience.

.re_potemkin does not follow the classic crowdsourcing model of an open call for volunteer labour on the internet. It was produced by many groups, but in a closed community. It functions more as an allegory of crowdsourcing than as a literal example of it, but this adds to the project artistically, creating a layer of depiction. The means of production are aestheticized in a way that presents them for the viewer’s consideration in way that can be understood and contemplated more easily than an amorphous internet project.

The “commons based peer production” of free software and free culture is not, to use Jaron Lanier’s phrase, “Digital Maoism”. But the comparison is a useful one even if it is not correct. Utopianism was exploited by the Soviets as it is exploited by the vectorialist media barons of Web 2.0 . re_potemkin gives us side-by-side examples of communism and crowdsourcing to consider this comparison for ourselves.

Within the work the similarities and differences between the original film and its recreation vary from the comical to the poignant. Students in a play park acting out shots of soldiers on a warship, hands placing spoons on a table cloth, crowds gathering around notice boards. This isn’t a parody, it’s an interrogation of meaning. And it is a strong example of why political, critical and artistic freedom is at stake in the ability of individuals and groups other than the chosen few of the old mass media to organize in order to refer to and reproduce (or recreate) existing media.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Seven years ago, or about two years before the invention of youtube, the editors of Tank Magazine saw the possibility of an internet platform dedicated to video art. Their response was tank.tv, an Internet site that is part moving image archive, part online gallery, and part cutting edge video art exhibition.

After a quick and painless registration, tank visitors can wander by artist through a catalogue of some of the best short films of recent time, including works by Ken Jacobs, Pipilotti Rist, Vito Acconci, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Guy Maddin, Jeremy Deller, and Saskia Olde Wolbers. This archive alone is enough to make tank.tv a cultural treasure. But about eight times a year, tank also puts up shows organized by theme, and here films by emerging artists like Claire Hope and David Blandy are featured alongside more established filmmakers and more recognizable names.

“The sole focus is on the work,” explains curator and creative director Laure Prouvost, who has been with the site since its beginning. Prouvost describes tank.tv as a completely open endeavor, one that supports experimentation by accepting submissions and curatorial proposals throughout the year: “We have worked to make tank.tv a collaborative platform over time and we’re still looking for ways to open our programme as much as possible.”

After running a series of solo shows in 2009, tank decided to finish the decade with the group show Open End. About twelve films were selected from the submissions tank.tv received throughout the year. Works by emerging artists received special attention. They include Just a Quiet Peaceful Dance by Dean Kissick, a rapid, flash cut montage that cascades in one smooth glide over its upbeat house track, and the dreamy, slightly disturbing 3D animation Your Uncertain Spirit by Jonathan Monaghan.

Each of these films were beautifully made and conceived, allowing a special kind of online engagement. In the lyrically photographed Momentary Seizures, Katja Aglert gives us an allegory of war and genocide through the life of a garden snail. Filmmaker Andrew Cross uses a single shot of the landscape as a meditation on time in his film Across. In Pulcera, Nicholas O’Brien uses a series of long takes to explore the relationship between image, gesture, and memory. Filmmaker Michael Fortune exploits the conventions of the reality television and the non-fiction form to make visible the relationship between custom, ritual, and community in We Invented Halloween.

Not quite essay, but something more like the spirit of anti-narrative informs other films in Open End. Among these is Jon Purnell’s CackULike, which documents men in white linen invading the mass transit system, and Steven Eastwood’s self-reflexive and ironic examination of filmmaking in Seminar in Film and Sound.

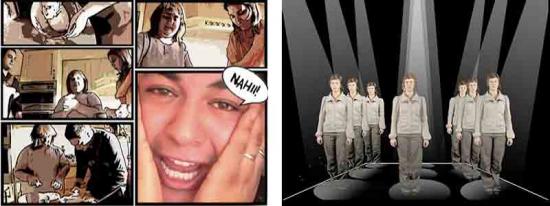

Screengrabs: CackULike by Jon Purnell (left) and Seminar in Film and Sound by Steven Eastwood (right)

By deconstructing the war film genre, Matthew Johnstone manages a few genuinely harrowing moments in Modern Warfare, a film which combines aerial photography of a bombing run with routine and no-so-routine audio tracks depicting military training sessions. In Inadvertent Prose, filmmaker Mark Shorey distills noir down to its single essential moment of threat and violence.

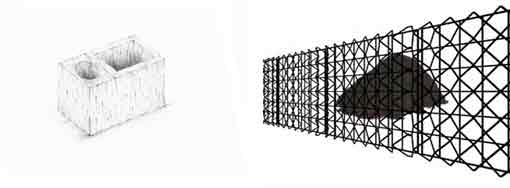

Animators are also represented. There’s the completely silly and kooky Conveyor-Iphone by Oliver Michaels, which just gets funnier and funnier as it runs its six minutes – really it is just wonderfully preposterous. Simon Woolham’s The Pile creates a mysterious and idiosyncratic relationship between an odd group of objects or states and their related sounds. In The Sausage Party #2, #D animator Michael van den Abeele pairs the evolution of a wire grid that slowly increases in complexity with the sound of a desolate, blowing wind.

About twenty thousand visitors from sixty countries will see Open End. This is obviously good news for the filmmakers who show work here and audience reach is one of the main benefits of their being online. But tank curator Laure Prouvost sees additional benefits in internet exhibition: “Websites such as ours or UBU or LUX offer direct and fast access to work that would otherwise be very hard to view. It’s a fantastic way to get an introduction to an artist’s work. For us curating online gives us a lot of freedom – we have low overhead costs and can react very quickly.”

While the Internet will never replace the cinema or the gallery, Prouvost does point out its use as an extension of those spaces. As the quality of delivery improves, Prouvost believes the web will be used more and more as an introductory space for serious video art. If you watch films, a copy of Fresh Moves, the first DVD compilation from tank.tv can be ordered through tank.tv’s website.

If you make films, Tank is also accepting submissions for The Whole World, an upcoming show by curator Ian White. Prouvost explains The Whole World as a show about the idea of lists: “Both a formal device and a political strategy, film and video that deploys a list as part of its structure often does so with political intent: to subvert hierarchies, to undermine rationalism or to reveal contradiction. In contemporary culture the pop chart’s Top 10 has been replaced by an ever-expanding craze for “Top 100s” of everything from Hollywood genres to celebrity gaffes. The Whole World attempts to wrestle back the initiative. As part of the show we continue to accept submissions of list-centric videos so that The Whole World continues to grow over time.”

Image: Wilfried Agricola de Cologne. All images courtesy Wilfried Agricola de Cologne

A person would think that, while watching the infrastructure of print journalism implode, or while noting the universal flight of viewers away from the television set, film makers would learn from the missteps of other mediums and make an early ally of internet distribution. But, for the most part, no, that is exactly what is not happening in film circles. Artists and film makers may put a trailer or a few movie stills up on a web page, but the film itself? Even in the age of broadband, it seems Netflix takes online distribution more seriously than curators. Fifty years after the invention of the internet, it’s still the case that screening a film online will certainly invite rejection from a festival circuit of jurists seeing premieres.

Since more than half the video I watch is now online video, my first question for artist Wilfried Agricola de Cologne was what he thought of these types of film festival policies. According to Agricola: “This is completely out of date. We live now in 2009, not in the media stone age of 1980. I think such a policy is principally wrong, since it is up to the artists/directors to choose and decide how they want to deal with their creative products.”

A media artist and film director himself, Agricola is also the founder and of the Cologne Online Film Festival, or CologneOFF, an online festival where I’ve lost more hours than I want to admit watching great art films from all over the world. Agricola describes CologneOFF as a new concept in art cinema – the networked festival – which includes a networked jury, networked contributions, networked screenings, and networked audiences. Now in its fifth year, CologneOFF takes place in the virtual and in the physical simultaneously, first, through the on-demand festival website, and second, through traditional screenings offered by cooperating partner festivals. In addition, each CologneOFF festival, from 2006 to the present, is permanently available for on-demand viewing online.

The ideas at work here are simple. If you like art cinema, you can watch some whenever and wherever you like. If you make art cinema, your avenues of distribution are becoming a bit more independent of external influences. If you are an absolute traditionalist, CologneOFF, and other festivals like it, show that programmers and filmmakers may not be able to avoid the Internet audience much longer and that barring online and interactive films from the festival circuit may not be the most forward thinking audience policy. After organizing over a hundred new media festivals, Acgricola questions the agenda of the anti-online curator: “Such a policy will not survive in the end or [it will survive] just as a fossil, since already now the best film and video artists use the Internet for their purposes, and some of them make currently big careers. Nobody honestly cares about some remaining totalitarian structures from the good old days.” Agricola notes that, as the CologneOFF continues, it creates its own rules, and follows those rules more and more.

Whatever your motives, the films are excellent, easily as engaging as the work you might see in a museum or traditional art cinema screening. Some have been shown in galleries. One example, Casey McKee’s cerebral chase film Corporate Warfare (2005), which pits two briefcase carrying, business-suited adversaries in a knock down drag out fight on the escalator to nowhere.

Since its beginnings, CologneOFF’s primary focus has been on films that examine memory and identity. As mentioned earlier, a visit to the festival website will give access to the festival’s earlier themes of identity, image and music, and art cartoons and animation. This year, under the title Taboo!, there was a special emphasis on the issue of prohibitions, the forbidden, and the transgressive.

Filmmakers Jaime Waelchi, Anna F.C. Smith, and Les Riches Douaniers responded with especially disturbing images. In Little Pleasures, Waelchi indulges herself in chewing gum to the point of drooling, choking, pain. Meanwhile, Smith uses Which Came First (2009) to present an ordinary kitchen chore as a scary and destabilizing sexual metaphor, drawing a link between taboo and the everyday household routine.

Image: Little Pleasures, Jaime Waelchi, USA (left) and Which Came First?, Anna F.C. Smith, United Kingdom (right)

There are notable works of machinima in this year’s program. If you can bear to watch, the film partnership Les Riches Douaniers remix Grand Theft Auto IV as a squishy critique of avatar indifference in the face of massive multiplayer game violence in their short film Motorized Ordeal (2009).

Watching movies as conceptually dense as these made me wonder when the online movie grew up and how it happened so fast. But when asked if this years entries were more complex than perhaps some of the straight plotted narrative entries of earlier years, director Agricola disagreed, reminding me that CologneOFF has always attracted challenging works. Often there is more worthwhile art cinema than even Agricola can present: “There were … too many excellent films submitted. Choosing Taboo! as a topic, we were hoping we would receive less submissions, but in the end we received 203 films and videos. This may … not sound [like] too much, but every work is reviewed several times before a selection is made and reviewing more than 200 films seriously represents a challenge for everybody, especially if so many good submissions come in.”

On another note, what is especially exciting is the maturing use of digital effects as an artistic medium in its own right. In Red Star (2009), Milica Rakic overwhelms history by creating a personal memoir of the past that blends archival photography, cut-up titles, and Serbian folk music. Part of the post-MTV generation, Nikesh Shukla assembled his film, The Great Identity Swindle (2008), as a video comic book that literally draws a picture of the taboos he faces as an adolescent Br-Asian. Thinking about the rules of personality led Sibylle Trickes to use video mutiples as an army of her many selves in her film cyclic islands – we and me (2009).

As digital tools move beyond the service of the seamless Hollywood effect to expressive mediums in their own right, what other cinematic forms might emerge from the digital film and the networked festival? Agricola says that technology is advancing so rapidly, he would need to be a fortune teller to predict the future of online cinema. However, he does point out that the Internet has already revolutionized the both viewer behavior and the distribution of art film: “Everybody can determine for himself where and when he wants to enter cultural contexts. I think, the physical live festival and the independent online availability complement each other, and make cultural experience for people, generally, much richer than it has been before ever. The development of cinema needs such different types of approaches, in order to be more attractive and future orientated. Restrictions are there to be overcome.”

Featured image: A group of Australian media artists known as Horse Bazaar produce Digital Fringe at the festival

Every year as part of the Melbourne Fringe Festival (September 23rd – October 11th), a group of Australian media artists known as Horse Bazaar produces Digital Fringe. This is a nonstop digital playlist of short form video, sound, and images, some of it made by artists, some of it not, uploaded to the Digital Fringe website from around the world. Once individual entries are catalogued, the work is assembled into feeds and DVDs, and then streamed or delivered to a network of public and private locations. As expected, the festival’s general stream is sent to museums and galleries but, in an effort to commandeer every available space, Horse Bazaar also sends Digital Fringe to bars, cafes, public squares, libraries, restaurants, and pretty much any other location that will allow them in. You can see the festival online, along with an interactive map of this year’s screen locations, at the Digital Fringe website, http://digitalfringe.com.au.

According to festival co-producer Simeon Moran, an estimated half-million people saw this year’s festival which was broadcast on about 250 screens. Most of these showings were in Australia, but there were also screenings in Africa, Europe, Asia, the US, and the UK. To project at locations where there is no existing equipment, on a street or in a public building, Horse Bazaar gathers donated screens from schools, community groups, and private supporters. To project across key buildings or monuments, Horse Bazaar calls in its mobile unit, also known as the MPU. Other than that, the festival can be, and is, about anything. There’s no jury. Submissions are not restricted to a theme. There’s just a global call for work followed by a global response.

As a result, one of the most enjoyable aspects of Digital Fringe is the range of sensibilities it manages to present. Emerging artists especially stand out. Among the more lyrical of this year’s entries is Waveform (2009), by the Amsterdam based French photographer Federico Campanale. Using video shot in Finland, Campanale lays an ambient track of digital pops and clicks against a perfect, languid, 360 degree pan of a line of trees reflected in a lake at dusk. The harsh, guttural rasp of the soundtrack set against the blue infinity of the horizon forms a direct commentary on environment and endurance, and on nature’s coexistence with the manmade.

There is the moody, existential narrative The Man in His Tower (2009) from Tone Gellein of Oslo. In this video, one of those tough guy movie characters walks down the street while suffering jump cuts and odd camera angles. He ends up swinging from lampposts in a cinematic expression of an existential state of mind. Other films may be less accomplished, but are equally philosophical. For example, filmmaker Joe Tusley sent in Spud & Amp in the Barra, Part 2 (2009), a no-frills documentary about a few minutes of fishing in the Apsley Straight, Bathurst Island, NT. Maybe it’s a personal reaction, but it’s hard not to think about the big picture as, on camera, Spud reels in a huge, silver barramundi, then slits its throat.

Digital Fringe also streams sound pieces, music videos, machinima, and performance films. There is a good amount of 3D modeling and animation. Colliderscope artist Zennor Alexander and musician Fiona Soe Paing submitted Thayn Tyha Hai (2009) from New Zealand. In this work, the sun and moon follow each other across a wispy, ethereal sky that lies somewhere between dreaming and waking. If you prefer something more scientific, there is the stop-motion simulation Every Second Equals Forty Million Years (2009) by animator Gregory Crocetti of Melbourne. In just under two minutes, Crocetti uses children’s blocks to build the Tree of Life from the beginning of time to just a little while ago.

There is software art such as Turkish programmer Tahir Un’s screensaver project Concepts and Images (2007). Ãœn chooses words ending with the suffix ‘ism’ as the query strings for an internet image search. After collecting images for 90 minutes, a software program fixes a random sampling of that data set into a collage.

Another interesting aspect of Digital Fringe is its continued support of open source computing and shared culture. Artists uploading work to the Fringe website keep all rights to their projects and are able to license their work in a number of different ways. These include the traditional ‘all rights reserved’ copyright, the Creative Commons ‘some rights reserved’ license, and the completely unrestricted category of ‘public domain’. Creative Commons says that about 75 percent of the festival’s participants choose the CC license, which secures rights of ownership while allowing for mash-ups and remixes. This shows that many emerging artists are willing to distribute under non-traditional copyright provided there are a still few small protections.

Ultimately, Digital Fringe, is a festival that intends to include everyone, play everywhere, and show it all from the dreamscape of the perfect virtual environment to the underlit reality of the amateur video guy. Aside from its inspiring generosity, we get a lot of interesting experiments, the unmediated juxtaposition of the professional and the amateur, and a kind of yearly almanac of what up and coming digital media makers seem to have on their minds.

—

Link: Digital Fringe Trailer.