Through our interactions with digital devices and systems us humans are now a diverse resource to other humans and machines. And we are changing in accordance with the processes and demands of contemporary, technological market systems, designed to extract as much data from us as possible. In his recent article Our minds can be hijacked, Paul Lewis of the Guardian revealed that those in the know, those who helped to create Google, Twitter and Facebook, are now disconnecting themselves from the Internet as, like millions of people in the world, they are feeling the effects of addiction to social networking platforms, and fear its wider consequences to society.

The hazards of this kind of tech-contagion have been the staple food of sci-fi for decades – a mysterious woman shares a strange but simple VR game in the 1991 episode of Next Generation Star Trek, The Game. It spreads like wildfire, taken up with enthusiasm by the crew, only later revealed to be a brainwashing tool invented by an alien captain to seize control of first the ship, and then all of Starfleet. Let’s look at ourselves for a moment – if we can tear our gaze away from our screens. How has our public behaviour changed – on the streets, on public transport, in buildings and parks? Our attention transfixed by our devices, online via our phones and tablets – bumping into each other, and even walking into the road endangering their own and others’ lives.

Professor of psychology Jean M. Twenge studies post-millennials and argues that a whole younger generation in the US, would rather stay in doors than going out and partying. Even though they are generally safer from material harm they are on the brink of a mass mental-health crisis. She says this dramatic shift in social behavior emerged at exactly the moment when the proportion of Americans who owned a smartphone surpassed 50 percent. Twenge has termed those born between 1995 and 2012, as generation iGen. With no memory of a time before the Internet, they grew up constantly using smartphones and having Instagram accounts. In her article Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation? Twenge writes “Rates of teen depression and suicide have skyrocketed since 2011. It’s not an exaggeration to describe iGen as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. Much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones.”

Internet addiction is like having your head perpetually inside a magical mirror of hypnotically disembodying power #addictsnow pic.twitter.com/DFkl1jaKER

— furtherfield (@furtherfield) August 31, 2017

From the #addictsnow Twitter commission by Charlotte Webb and Conor Rigby, 2017

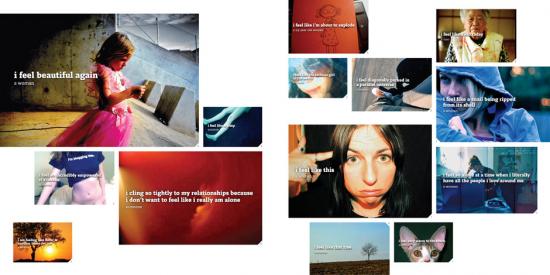

We offer three features as part of Furtherfield’s 2017 Autumn editorial theme of digital addiction, in parallel with the exhibition Are We All Addicts Now? at the Furtherfield Gallery, until 12th November 2017. Artist Katriona Beales has developed the exhibition and events programme in collaboration with artist-curator Fiona MacDonald: Feral Practice, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett. She explores the seductive qualities, and the effects of our everyday digital experiences. Beales suggests that in succumbing to on-line behavioural norms we emerge as ‘perfect capitalist subjects’ informing new designs, driving endless circulation, and the monetisation of our every swipe, click and tap.

Firstly we present this interview with Katriona Beales* from the new book Digital Dependence (eds Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, 2017) in which she discusses her work and her research into the psychology of variable reward, “one of the most powerful tools that companies use to hook users… levels of dopamine surge when the brain is expecting a reward. Introducing variability multiplies the effect” and creates a frenzied hunting state of being.

Pioneer of networked performance art, Annie Abrahams, creates ‘situations’ on the Internet that “reveal messy and sloppy sides of human behaviour” in order to awaken us to the reality of our networked condition. In this interview, Abrahams reflects on the limits and potentials of art and human agency in the context of increased global automation.

Finally a delicious prose-poem-hex from artist and poet Francesca da Rimini (aka doll yoko, GashGirl, liquid_nation, Fury) who traces a timeline of network seduction, imaginative production and addictive spaces from early Muds and Moos.

“once upon a time . . .

or . . .

in the beginning . . .

the islands in the net were fewer, but people and platforms enough

for telepathy far-sight spooky entanglement

seduction of, and over, command line interfaces

it felt lawless

and moreish

“

And a final recommendation – The Glass Room, curated by Tactical Tech

Tactical Tech are in London until November 12 with The Glass Room, exhibition and events programme. A fake Apple Store at 69-71 Charing Cross Road, operates as a Trojan horse for radical art about the politics of data and offers an insight into the many ways in which we are seduced into surrendering our data. “At the Data Detox Bar, our trained Ingeniuses are on hand to reveal the intimate details of your current ‘data bloat’; who capitalises on it; and the simple steps to a lighter data count.”

*This interview is published with permission from the publishers of the book Digital Dependence edited by Vanessa Bartlett and Henrietta Bowden-Jones, available to purchase from the LUP website here.

In her work, using video, performance and the Internet, Annie Abrahams questions the possibilities and the limits of communication, specifically its modes under networked conditions. A highly regarded pioneer of networked performance art, Abrahams brings her academic training in both biology and fine arts to develop what she calls an aesthetics of trust and attention. She creates situations that “reveal messy and sloppy sides of human behaviour” making that reality of exchanges available for reflection. We first worked with Abrahams in her exhibition ‘If not you not me’ in 2010 and then as part of a group show ‘Being Social’ 2012. In this interview we ask her to reflect on the limits and potentials of art and human agency in the context of increased global automation.

Catlow & Garrett: While predicated on the idea of connectedness, the global social media platforms are designed to profit the companies who create them and to keep billions of us in a state of trance-like immersion which has in turn been shown to cause many of us to feel more isolated. At Furtherfield we have always worked to grow more communal and collaborative contexts for artistic production. What does your current thinking – through your work on Participative Ethology in Artificial Environments: ethnological approaches to Agency Art – reveal for the potential of genuine, participatory networking environments?

Annie Abrahams: Participative Ethology in Artificial Environments: ethnological approaches to Agency Art sounds nice, but it needs a question mark at the end. It’s an interrogation. In times when our technological environment uses all kinds of behavioural techniques to make us uncritical users of their interfaces, it’s important to become aware of our behaviour, to test and experiment with it. My artistic work is based on doing that, but I always had great difficulties explaining it to art institutions etc.

A discussion I had with my friend Cor whom I studied biology with in the seventies, helped me find this latest description. I told her, that I think about my work as having human behaviour as its main aesthetic component and why I call it, silently, “behavioural art”. I compare what I do now to what I did when I studied biology. In both cases I observe behaviour in constrained situations. The monkeys, that were the study objects “became” humans and the cage the Internet.

Because the behavioural science of the late seventies didn’t suit me very well – using Skinner boxes, operant conditioning techniques and related to sociobiology, with a link to eugenics – it has become impossible to use this historically contaminated term. The wish to control, mold nature, and humans wasn’t mine. “Behavioural” was and still is a “stained” word for me. But even so, I do study behaviour and create constrained situations. I ask people to perform in a frame, they are framed in an apparatus, which is more or less perfect – the Internet provokes, lags, bugs, glitches, the computer is old or new, fast or slow, the interface determines how the performers can interact or not, the domestic situation interferes with noise and cats wanting to join in. There is a protocol/a script/a scenario but no rehearsal, just some technical tests. My approach is more phenomenological than scientific, I don’t measure anything. It’s up to the performers to explore their own behaviour, to reflect on it and to learn together what it means to be connected.

I told Cor, my annoyance with the tendency of art institutions to categorise art. Video art, poetry, contemporary art, literature, dance, painting, music and media art, computer art, code art, … It’s so impractical and superficial and it always takes a technology or a medium as its anchor point. It doesn’t say anything about what it makes possible, about what we can experience through it. Maybe that’s why I started to use the word performance, and performance art more and more. It’s a cross-discipline word. It’s multi purpose, but also a bit empty, I must admit.

“Agency Art is art that makes it clear to the receiver via his or her body what is at stake, where opportunities for action lie, and which virtual behaviours he or she can actualize. It demonstrates how choices work.” Arjen Mulder, The Beauty of Agency Art, 2012.

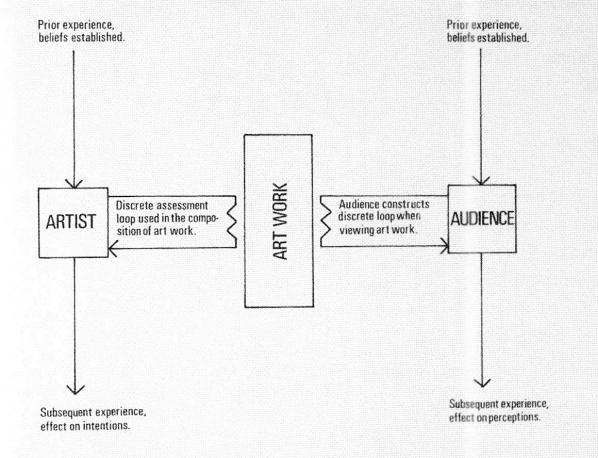

In his article The Beauty of Agency Art, Arjen Mulder uses the concept Agency Art to indicate interactivity as the important component of an art work. It is an interesting attempt to develop a discourse for technology/media art in relation to the contemporary art discourse. He embeds his ideas in history and goes back to thinkers such as: Shannon, Wiener, MacKay, McLuhan, Cassirer, Langer, Gell, Latour, Heidegger, Derrida, Badiou, Rancière, Danto, Whitehead, Steiner, Rolnik and more. I like the concept because it determines art that has behavioural choices and gestures as its centre. Its meaning is the acts that are made possible. What is also important in Mulder’s reasoning, is the concept of “virtual feeling”, introduced by the philosopher Susanne K. Langer in her groundbreaking book Feeling and Form (1953). Langer explains how each individual art medium evokes, manipulates and investigates “virtual feelings” in its own way.

“A painting calls forth virtual depth with lines and colours; a sculpture constructs a virtual volume around itself; a novel constitutes virtual memory, tracked through virtual time. Dance follows virtual forces of attraction and repulsion. All the experiences that are part of this “feeling” are spaces of possibility, virtual feelings waiting for actualization; their nature, allurements and dangers must be studied, and art is where this investigation takes place” Arjen Mulder, The Beauty of Agency Art, 2012.

This is how to think of behaviour as an aesthetic force, I told Cor. This is a concept that I can use to talk about what is important to me. For me, the words are empowering and stimulating, pointing to Butler, ANT theory and Karen Barad, I cannot and won’t leave them behind me.

collectively made – refusing hierarchy- a knitting together of artists and performers in the moment of the event – erasure of the artistic ego – practice – changing rules – choices – connecting – accepting the unexpected – responsive – shared – collaboratively authored – open to all – working with temporal behavioural phenomena – healing – enactment – improvised – including environmental conditions – attentional strategies – instructions – protocols – apparatus – meeting – embracing the ordinary – rehearsing alternatives – re-hijacking therapy – exercising our relations to others – our social (in)capacities – exploring rituals – being together – participatory – concerns individuals and politics

These are keywords found while researching work (from fine art, dance, theater, music, performance, digital art to electronic poetry) I could consider being Agency Art : Deufert&Plischke’s work, LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner’s HEWILLNOTDIVIDE.US, Building Conversation by Lotte van den Berg, Deep listening by Pauline Oliveros, Poietic Generator by Olivier Auber, Lingua Ignota by Samantha Gorman and Walking Practices by Lenke Kastelein.

Using Agency Art also means being able to make cross sections through disciplines and to open up closed domains of practicing. And that is the moment in our conversation where Cor, who has also a degree in philosophy said : “It’s easy, call your work participative ethology in artificial environments.” I am still pondering and that’s why there has to be a question mark. There always have to be question marks.

#PEAE = #Participative #ethology in #artificial environments #ethnological approach #AgencyArt?

C&G: Katriona Beales drew our attention to the Kazys Varnelis’ essay in the Dispersion catalogue (ICA 2008) which talks about the concentration of power in nodes of connectedness. She says “So even if I write a response to Donald Trump’s tweet saying “I hope you’re impeached”, for example, I add to his power, just through the interaction. I end up contributing to his power base even though I explicitly disagree” This effectively rewards, with attention, those who inspire intense outrage, fury and derision. Interfaces play a crucial role in your network performances and deliberately prompt very different kinds of behaviour – we’re thinking in particular of Angry Women. What kinds of behaviours and responses does your work inspire?

AA: I agree the concentration of power in nodes of connectedness is disturbing and confusing. It puts us in a double bind situation, becoming petrified, unable to act or to flee because we can not choose. I think this might be true when we consider our role in big networks, but it is definitely different when we talk about smaller networks. There it matters what we say and especially how we say it. A big part of my work is to create situations / interfaces / performances that permit us to experiment and train our (un)capacities to do so in networked environments. Participating in one of my performances means taking risks – nothing is rehearsed, means accepting you can’t control everything, it means committing to continue even if all seems to go wrong, to be attentive to the others around you with whom you share the performance space, with whom you are co-responsible for the shared moment in time.

From the people watching I ask that they are aware of what is at stake in a performance. That they watch it not with a connoisseurs regard, but that they see it as an aesthetic experiment in which behaviour is the main aspect / asset. If they become sensitive they have access to a very intimate and fragile aspect of our being, to something we absolutely need to discover further if we want to escape an allover binary future.

For myself I analyse the “concentration of power in nodes” phenomenon as the result of something you could call a lack of res-ponsability in our online affect management. When you are always scrolling you are unaware of the reaction you provoke, you are not awaiting a reply, but already on the next, next, next photo or short text. There is very little interactivity, and even less exchange. We act without caring for what our words, actions, and ideas bring forth. We might not be aware but our words, actions, and ideas live beyond us, they do intra-act with the actual situation. They are things acting in a world. (**)

** I have been reading texts on intra activity, a neologism introduced by the physicist, and feminist theorist Karen Barad. It’s difficult stuff. This video (Written & Created by: Stacey Kerr, Erin Adams, & Beth Pittard) gives easy access to one of her most important points.

C&G:

Yes, it is now totally normal to refer to “people” as “consumers”, every organisation an “enterprise”, which in turn leads to proposals for the nation-as-a-service, populated and run in the interest of private enterprise as offered by the e-stonia bitnation project.

By accepting the impoverishment of experience and reduction in agency implied by this label we can forget about ourselves as “actors” in the world, and become the cattle of the few. The only agency we are offered is as a responsible consumer (in which our powers are reduced to a binary option to buy or not). This is the new democracy.

In the UK these days, art audiences are often described as “consumers”. How else in your view might we conceive of “audiences”. What agency might we wish for them. And what part might our relationship with devices and digital networks play in this new description?

AA: We are not yet used to machines reacting to and using affects, tapping into our endocrine system. Articles like “Our minds can be hijacked’: the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia” make us more and more aware of how we are manipulated and distracted, how our attention is designed, guided, influenced, used. But a lot of it is still hidden and because it’s so rewarding and because we “need” the attention we continue to click and vote. It is possible to create environments where people can slow down and have more subtle, nuanced agency, where they can participate and become aware and reflect on of their own behaviour. DIWO projects for instance have that power. People, especially art lovers, can be challenged to engage with others in interesting actions and conversations.

With Daniel Pinheiro and Lisa Parra in Distant Feeling(s) we invited the audience to join us in an experiment where we share an interface, normally used for online conferencing, with our eyes closed and no talking allowed. It led to very diverse observations shared via social media and email exchanges: liminal space – pure motion – an intimate regard – a field of light – dissolved, destabilized – an altered state – a telematic embrace – a silent small reprieve – hanging out with friends – machines conversing across the network only when the noisy humans finally shut up – an organic acceptance of silence?

Keywords from the reactions : http://bram.org/distantF/

Distant FeelingS #3 | VisionS in the Nunnery – Oct5-Dec18 2016

C&G: Unlike technologies and forms of production that work in the area of speculative realism, automation and AI, you still place humans and human relations at the centre, how do you view the current moves to shift agency away from humans into these ranges of techno-social systems?

AA: I am particularly intrigued and troubled by what is called deep learning. The algorithms produced by the machines themselves have a big influence in and, we must be honest, potential for for instance the health care business. They also determine on what moment of the day, depending on your mood you will see which advertisement on your device. As explained in The Dark Secret at the Heart of AI nobody can really understand how these applets produce their outcome – not even the programmers who build them.

For me this is problematic. Algorithms cannot invent what didn’t exist before and so they tend to reproduce / to select more of the same / to reinforce the existent. (see deep dream images) Moreover a lot of deep learning is based on the algorithm learning to produce a desired outcome.

As the machines are also designed to make us ready for their coercion, we are already subconsciously, intuitively adapting to these black box processes. We need to try to understand how these processes influence us, not because they are necessarily bad, but because our interests might not always coincide, we might want to differ. We don’t all have to learn programming the machines. That has become far too complicated and specialist and maybe not the best route to take. But we could engage in projects who try to find out how to influence machine behaviour, how to keep some agency. Maybe by introducing noise and entropy into the processing, so, together with the machines we can continue to cherish difference and diversity.

C&G: This question connects with the previous one. How do you see the role of artists in finding ways to negotiate a healthy relationship between artistic agency and capital-driven-machine worlds?

AA: This is a very difficult question to which every artist has to formulate her own answer. But it for sure passes by trying to open up spaces and discussions with people who have other opinions than yours, to going beyond safety-zones, to finding ways to communicate with and about hatred, angst and love.

*——————–*

This editorial series, takes digital addiction as its theme, and sits alongside the Are We All Addicts Now? exhibition, book, symposium and event series, we are hosting at Furtherfield. Are We All Addicts Now? Is an artist research project led by Katriona Beales and has been developed in collaboration with artist-curator Fiona MacDonald: Feral Practice, clinical psychiatrist Dr Henrietta Bowden-Jones, and curator Vanessa Bartlett. It looks at the application and impacts of many different research findings in the creation of digital interfaces, devices and experiences under the conditions of Neoliberalism.

The four day event at the Showroom collated a series of practitioners, artists, theorists and historians, to examine, test and explore ideas stemming from cybernetics and information theory and more specifically the idea of feedback.

Described as an ‘experimental cross-disciplinary research project’, Signal : Noise was a fusion of talks, lectures, performances, screenings and debates that made diverse contemporary evaluations of the legacy of cybernetics using an inter-disciplinary approach. It tackled subjects as seemingly diverse as economic theory; urbanism and the arrival of the motor car in London; game theory; linguistics; media-performance art from the 1970’s; and the problematic legacies of the recent UK arts funding system on artists – all viewed using the concepts and terminologies of cybernetics and systems.

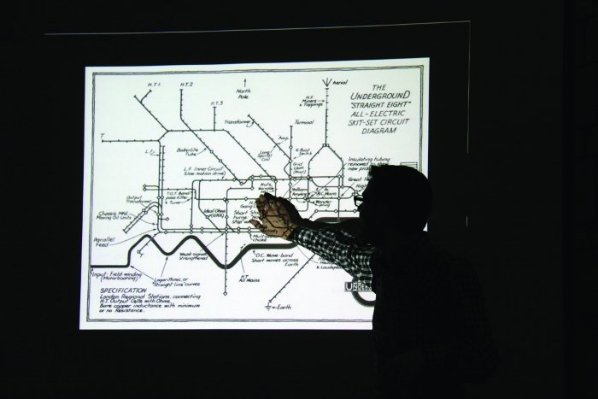

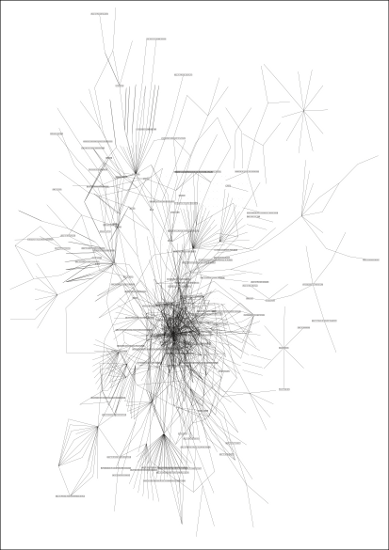

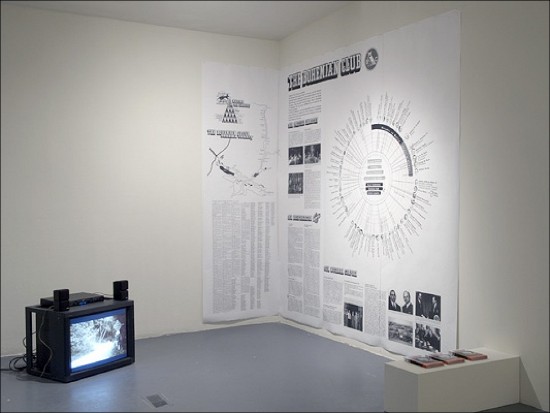

Signal : Noise, in part, played out like a small conference, mainly set in The Showroom Gallery space with one wall covered with a network diagram drawing by Stephen Willats, and fly posted theoretical systems diagrams from his recently re-published 1973 book, or maybe manual, ‘The Artist as Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour’.

This visual reference served as a backdrop to the proceedings and served as an on going reminder that despite the deep theoretical and historical base being presented and discussed in its many forms, Signal : Noise was ultimately attempting to re ignite debates, and help reset the ideas of cybernetics and systems into a contemporary context of practical application. Willats’ book describes his process as an ‘investigation by the artist into the processes, procedures and models’ of the ‘Art Environment’ using ‘cybernetics as a research tool’.

The first night introductory presentations by Charlie Gere and Steve Rushton provided an overview of many ideas explored throughout the weekend. Artist and writer Steve Rushton on ‘How Media Masters Reality’ used an array of examples, from conceptual and media architecture group Ant Farm using pioneering ideas of investigating media feedback, through to the 500 millions votes (!) on US TV programme American Idol; the latter an example of how contemporary applications of media feedback loops are now often conceptually embedded into the core of television productions, and in turn, are now part of the audiences expectations and involvement.

Ant Farm’s 1975 work ‘The Eternal Frame’, screened later during the weekend, along with Gary Hill’s Why Do Things Always Get in a Muddle (Come on Petunia), based on Gregory Bateson’s Metalogues.

Ant Farm’s 1975 work ‘The Eternal Frame’, screened later during the weekend, was their carefully staged, somewhat trashy live ‘re enactment’ of the 8mm film footage of the Kennedy assassination, complete with a drag version of Jackie Kennedy and sunglass wearing suited security. This film sequence is familiar today, but in 1975 it had yet to reach the public domain. Working to a tightly choreographed moment derived from a bootleg of the 29 seconds of 8mm film, Ant Farm’s grotesque mimicry of the assassination was performed as an ongoing loop, complete with car driving around the block (interestingly, the random people watching in the street in 1975 took photographs like they were at a theme park).

Despite being conceived in the mid ‘70s media environment of portable video and cassettes, the documentation of Ant Farm’s performance resonated with something surprisingly familiar and contemporary in our era of the internet, social media and rolling 24 hour news, and what Rushton termed our “society of self performance”.

Rushton’s historical threads from the origins of Cybernetics and to the Whole Earth Catalogue and the WELL served as a excellent base for the oncoming proceedings of the weekend, and showed that the arrival of the contemporary mass information network in the form of the internet, has habituated it’s millions of users into a kind of cybernetic practice based on input, observation, control, intervention, response, feedback, and adaptation but without necessarily using or being aware of its lexicon.

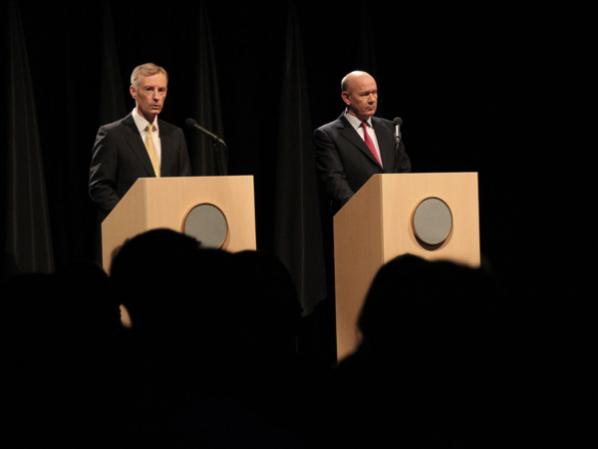

Nearby, in the Cockpit Theatre, was ‘Closed Circuit’ a performative work by Rod Dickinson (along with Rushton), which consisted of two actors staged and dressed, in a precise duplication of a set for political announcements; wooden lecterns, curtained background, complete with an array of flags – but all carefully neutralized by the removal of logos and national flags identities into plain white.

What followed was a series of political speeches utilizing the familiar language and tone of grandeur and crisis, delivered by the actors in the style of a world leader address. What they delivered, was a carefully sequenced remixed script derived from political speeches over the past 50 years; Margaret Thatcher; Richard Nixon; Ronald Reagan; Tony Blair; Yasser Arafat and others. All the details from each specific event they were referring to had been carefully edited out. The only way to differentiate one world leader, country or event from another, were the large projected auto cues for the actors, situated behind the audience at the rear of the theatre. Each one gave the full scrolling speech text and also the year and original context for each leaders’ delivery. Looking towards the stage, it sounded like a single coherent speech, but eluding any specific meaning, isolating the language of threat and authoritarian political control, leaving us just the husk of political presentation and the transparency of the format itself.

Ideas explored in Stephen Willats’ network drawing were expanded further during his talk in the final morning session of Signal : Noise, where he gave a refreshing clarion call to abandon ‘last century thinking’ during his prescient and timely discussion. His seminal works have persistently and methodically challenged the process, structure and meaning of art making and display. Willats made his earliest system diagrams in the late 1950’s, and was the first artist to make the artwork itself a map of communication. But maybe it is this century, rather than our last, that will connect with his provocations to the hierarchical, highly codified, object obsessed ‘Art Environment’, as he terms it, to see that ‘object based thinking is still a hangover from last century attitudes’.

Willats was an early reference for emerging net art and media art in the mid 90’s, with artists then clutching for any art historical roots that gave the field of networked and computer based practice some practical grounding.

This in-conversation with Emily Pethick surveyed his own personal development and immersion in Cybernetics in its differing stages, a short history lesson, moving from Norbert Weiner to Gregory Bateson and Gordon Pask, but always resolutely en route to the practical issues in the present and what Willats defines as the artist as an ‘instigator of transformation’.

In parallel to Willats, was a presentation and discussion hosted by Emma Smith and Sophie Hope which began to interrogate the legacy of a the New Labour arts commissioning process. It discussed how the criteria for successful funding was intrinsically linked to a social agenda, audience and location set by government policy. Discussions followed about how the arts commissioning process may turn out to have skewed a generation of artists practice, as they slowly lost control of their own output, became tagged with being an ‘artist facilitator’, and began conceiving works to fit in with the criteria of funding bodies, with each funder slowly extending their own prospective reaches. All this supported by an immense drive to build ‘Cultural Industries’ into mechanisms for regeneration.

Seeing this placed against Willats, whose ongoing practice could initially seem in tune with the past decades cultural policies and its overtly prescribed socially engaged agenda, in fact served to show how contrasting, distinct and rich his rigourous thoughtful approach is by comparison.

All this made for a timely discussion. With the approaching withdrawal and decimation of arts funding in the UK, Signal : Noise could prove to be a prescient event. With presentations, workshops and panels by Stuart Bailey and David Reinfurt of Dexter Sinister, Charlie Gere, Matthew Fuller, Marina Vishmidt and others, the interdisciplinary approach of Signal : Noise worked well despite its fairly dense timetable.

Using the gallery as a discursive space, with theorists and writers set within context of practice, is a good base for the next event in this on going series. What it maybe didn’t allow for, which is easily rectified, is a more unpredictable agenda, and more intervention by the ‘audience’. The whole event could function more as a real feedback working system, an adaptable structure that potentially allows for input from its participants (both presenters and audience) letting things move in unexpected directions both on line and offline, leaving a physicalised network as a residue after the event. With the decision to include food and beer in the ticket price (great dumplings, fresh vegetables and miso soup), there is potential here to expand this type of event even further.

With the on coming cultural landscape in the UK moving into un-chartered territory, it is potentially events like Signal : Noise which might begin to unearth and test new ideas and ignite debate within a less rigid format than a ‘curated’ show. In the future this type of event may even re-claim the word ‘radicalise’ from its current narrow, negative media usage, and re-purpose it for artists who decide to reject art market values, in favour of a exploring new ways of working within the emerging (and significantly less funded) ‘Art Environment’.

Signal : Noise. The project was led by Steve Rushton, Dexter Sinister (David Reinfurt and Stuart Bailey), Marina Vishmidt, Rod Dickinson and Emily Pethick. http://www.theshowroom.org/research.html?id=161&mi=254

The Artist as an Instigator of Changes in Social Cognition and Behaviour. 1973. Stephen Willats. http://www.occasionalpapers.org/?page_id=825

Closed Circuit, Rod Dickinson in collaboration with Steve Rushton.

http://www.roddickinson.net/pages/closedcircuit/project-synopsis.php

Dr Charlie Gere. Reader in New Media Research. Department: Lancaster Institute for the Contemporary Arts. http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fass/faculty/profiles/charlie-gere

ANT FARM. ART/ARCHTECTURE/MEDIA [1968-1978]. http://artsites.ucsc.edu/faculty/lord/AntFarm.html

The Eternal Frame by T.R. Uthco and Ant Farm: Doug Hall, Chip Lord, Doug Michels, Jody Procter. 1975, 23:50 min, b&w and color, sound. http://arttorrents.blogspot.com/2008/02/ant-farm-eternal-frame-1976.html

Emma Smith. Social practice that is both research and production based and responds to site-specific issues. http://www.emma-smith.com/www.emma-smith.com/Homeindex.ext.html

Sophie Hope’s work inspects the uncertain relationships between art and society. http://www.welcomebb.org.uk/aboutSophie.html

Featured image: Games/03 Paul Sermon, Peace Games, © der Künstler 2008.

Das Spiel und Seine Grenzen: Passagen des Spiels II ed. Mathias Fuchs and Ernst Strouhal, (Springer Verlag, 2010), German language only.

Fuchs, Mathias; Strouhal, Ernst (Hrsg.)

1st Edition., 2010, 272 S. 16 Abb., Softcover

ISBN: 978-3-7091-0084-4

Versandfertig innerhalb von 3 Tagen

Mathias Fuchs is considered to be one of the first artists to explore the combination of videogames and art. Today he is a senior lecture at Salford University in England and a leading researcher on Game Art and ludic interfaces. Social and political context in videogames and how they affect our society has been a major topic in Fuch’s research. Last year he published, together with Ernst Strouhal, an anthology of videogames and its borders and how this genre is changing and influencing society. The background to the anthology was an exhibition held at Kunsthalle Wien in 2008 about art and politics in videogames.

It has been 60 years since Johan Huizinga’s now classic book Homo Ludens, the playing human, was published. Games are no longer just entertainment; it’s a major industry that is affecting our society in every aspect. In the foreword Fuchs states that the main issue for the 15 essays in the anthology is how games have changed and affected our society both politically and socially since they crossed over from the realms of entertainment into everyday experience.

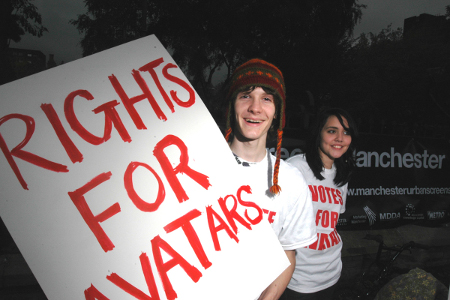

Today we can find many different genres in videogames, such as serious games and persuasive games, that discuss current issues, news and social problems, artistic games which address existential and aesthetic aspects, and so on. The gaming community has grown enormously and created on-line worlds with strong virtual economics, attached real world economics. In her essay Daphne Dragona says “The virtual environments of our times therefore can be seen as social institutions with social, political and economic values resembling those of real life.”

In a similar way Tapio Mäkelä’s essay about locative games describes how the gamescene has entered the real world in the form of cos-players and social gameplays where videogames as Pacman are performed in the city streets or games as “/Noderunner/, where participants run to find open WiFi Networks, take a photo of themselves at the location and send the info via e-mail to the project’s website.” This begins to close the gap between networks and everyday experience through the practice of social gaming. The game as object is less of an obvious conclusion now that technology enables us to explore ourselves within networked, gaming contexts and mobile technologies.

The borders between game and reality have now become even more blurred and integrated, especially if we consider how technology itself also crosses over into administrational activites which have already been traditional elements of controlling, processing parts of our lives. One example is how authorities around the world are supervising these new socio-economics, such as collecting taxes from virtual incomes by using similar tools and networks. There are many questions about how games will continue to affect and change our society in the future and the anthology takes an interesting and comprehensive look into what games have to offer and what could be potential threats to our future societies.

Today games are serious business. It is not impossible that in the future a bankruptcy of an on-line gameworld could shake the real world and create an economic depression. On the other hand, could on-line game economies bring prosperity and create new jobs, an economic boom in ways we have not witnessed before? If games move into a new period of changing social experience in even more connected ways than before, then we need to understand what the consequences of these are and how to navigate through this shifting terrain. One thing is for sure, it was a long time ago that games were just entertainment.

http://www.springer.com/new+%26+forthcoming+titles+%28default%29/book/978-3-7091-0084-4

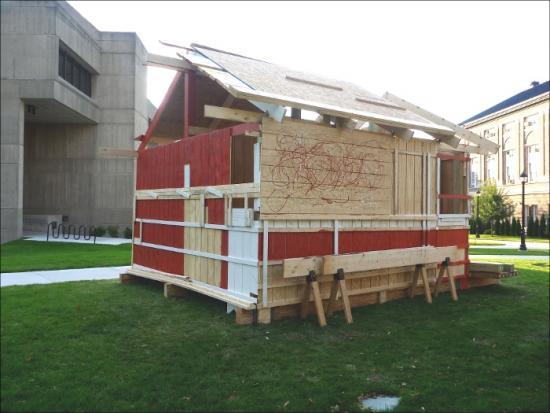

All Raise This Barn – a group-assembled public building and/or sculpture.

“Artists MTAA are conducting an old-fashioned barn-raising using high-tech techniques. The general public group-decides design, architectural, structural and aesthetic choices using a commercially-available barn-making kit as the starting point.” -MTAA

Eric Dymond: Could you give me a brief history of MTAA?

T.Whid: Mike Sarff (M.River of MTAA) and I met in college at the Columbus College of Art & Design in Columbus, OH. We both separately moved to NYC in 1992 and started collaborating as MTAA in 1996 first on paintings and then moving on to public happenings and web/net art. We’ve been collaborating since, showing our work via our websites at mteww.com and mtaa.net. We’ve earned grants and commissions from Creative Capital, Rhizome.org and SFMOMA and shown at the New Museum, 01SJ Biennial, the Whitney Museum and Postmasters Gallery.

ED: The All Raise This Barn project uses one community to design and another to construct. Barn raising is itself a communal activity, drawing out the best in people and providing a place of sustenance for the Barn owner. How did you come to use a Barn Raising as the central performance subject?

M.River: From the start, Tim and I have been interested in how groups and individuals communicate. How do we speak to each other? What rules do we use? How does communication fail or how can it be disrupted? What is the desire that engines (TW: controls?) all of this – and so on. This interest in exchange is what attracted us to the Internet as a site for art in the beginning.

Along with communication as text, speech or image, we like to use group-building as a method for working with non-verbal communication. We’ve built robot costumes, car models, aliens and snowmen with large and small groups. It’s a type of building that is intuitive and open to creative improvisation. This kind of intuitive building is heightened by placing a time constraint on the performance. In the end it’s not about the end object, which we always seem to like, but more about the group activity.

So, at some point we began to think how large can we do this? A barn-raising seemed like the next level. It’s bigger than human scale and contains a history of group-building. Barns also have a history of being social spaces. Your home is your world but the barn is your dance hall.

ED: Did you envision it as a community event from the beginning?

MR: Yes. An online community, a physical community and a community that overlaps the two.

ED: It’s a hybrid work that draws upon some important conceptual precedents. The instructional aspect takes Lewitt and turns the strict instructions he uses upside down by allowing online decisions to drive the design. Did you find the responses to the online polling surprising?

MR: Yes and no. Like the other vote works we have produced, Tim and I set up how the polls are worded and run. So, even though we try to keep the process as open as possible, the nature of how people interact is somewhat fenced in. Even with a fence, people will find a way to move in strange directions or break the fence. It’s not that we think of the surprising answers as the goal of the work, but it is an important part of the process.

ED: There is also the performance aspect which I find exciting. The performance from both events are well documented. Were there any concerns regarding the transfer of the polls instructions to physical space?

MR: We had the good fortune of doing the work in two sections. When Steve Dietz commissioned ARTBarn (West) for the 01SJ Out of the Garage exhibition, we spoke about the sculpture as a working prototype for how a large pile of lumber could be group-assembled in a day with direction from Internet polling. From this prototype we then had a model for how to go about ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC.

Tim and I had a few loose ground rules on how to approach the translation. One was that we would leave some things open to the interpretation of the crew. Another was that both Tim and I had our favorite poll questions that we tended to focus on. It was impossible to do everything as some polls conflicted with other but some details liked ghosts, dripped paint and open walls seemed to call out to us.

Kathleen Forde, who commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC, spoke about these details as where the work became more than the sculpture. The small details held the whole process – material, design polls, and performance together.

ED: I think this comment on the details is right. On first glance there is a fun, open appeal to the work. But when you look at the overall project and how the different phases are tied together it becomes really complicated in the mind of the spectator. There are also different definitions of spectator in this work. The spectator who answers the poll, the spectator on the net who is grazing through the documentation, the ones who engage in the physical construction and those who witness the completed barn. It’s not a simple piece when we perform a detailed overview. Did you think about the various types of spectator that would spin off the project? Were the possible roles for the spectator considered after the fact or were they part of the planned concept?

MR: The “ideal spectator” thought first came up for us in a project called Endnode (aka Printer Tree) in 2002. For this work, we built a large plywood Franken-tree with a set of printers in the branches and a computer in the trunk. We then built a list-serve for the tree as well as subscribed it to a few list-serves. When people communicated with the tree, the text was printed out in the exhibition space. At first we talked about the ideal viewer as one who communicated with it online and then saw that communication in the physical space or vice versa.

Now I feel that the ideal spectator hierarchy is not as important and possibly limiting. Each experience should be whole as well as point to the larger aspects of the work. People can come in and out of the work on different levels. You voted. You followed the performance documentation. Are you missing an experience if you did not build with us or see the results? Yes, an activity is missed. Can you experience that activity thorough documentation. Somewhat. Are you going to have a better understanding of the work. Probably not. Even for me, some aspect of the work will not be experienced. In Troy, they are programing it as a meeting place now that is it is built.. When they are done with it, they will dismantle it and rebuild it elsewhere as a work space.

I say all this even though it is interesting to me that a work can move in and out of levels of viewer experience. I’m not sure as to the draw of it yet but I do not feel it is about an cumulative effect.

TW: Since Endnode I’ve always liked the idea of an art work that exists in multiple (but overlapping) spaces with multiple (but overlapping) audiences. With our pieces Endnode, ARTBarn and Automatic For The People: () there are 3 distinct (but overlapping) audiences: the online audience, the audience in the physical space and the (select few member) audience that experiences the entire thing.

ED: It’s that opening of possibilities that makes this ultimately a networked piece on many different levels. I find the idea of two barns, a few thousand miles apart yet linked by common purpose really intriguing. I’m talking about the whole set of experiences, not just the physical space of the barn. There’s a collapse of Geographic distance for the community and a richer experience because of that. Was the project conceived as two distinct locations or was that a fortunate turn of events?

MR: Fortune. Kathleen Forde, commissioned ARTBarn (East) for EMPAC then Steve Dietz commissioned the beta version for the 01SJ “Out of the Garage ” exhibition. Everyone liked the idea of the work arching across time and location. We all also liked the idea that the materials would be reclaimed after it stopped being a sculpture. For me, the reclaimation of the materials to use for a functional structure is the final step of the work.

ED: As the final step, the reclamation removes the common space where the community currently shares the sculpture. Does this mean you are going to use the online documentation as the artifact, coming full circle to where the piece began? Is it important to you that the communal memory will share this role?

TW: Yes, the documentation is the artifact. The barn structure or sculpture itself had been conceived as being physically temporary from the beginning.

ED: Thanks to both of you for your time and for this work.

Alejo Duque, Kathrin Guenter, Graham Harwood, Martin Howse, Petr Kazil, Jonathan Kemp, Martin Kuentz, Tom McCarthy, Christian Nold, Nick Papadimitriou (tbc), John Rogers (tbc), Karen Russo, Gordan Savicic, Suzanne Treister, Danja Vasiliev, Ryan Jordan

In episode five of the popular Israeli sitcom, Arab Labor, Amjad and his family are invited for Passover to the home of a reform family whose son goes to kindergarten with Amjad’s daughter. Amjad is enthusiastic about the Seder ceremony and decides to adopt the concept of the Haggadah into Eid al-Adha (The Festival of Sacrifice). In this way Amjad attempts to balance his life as an Israeli Arab by using some food, a bit of ceremony, and a lot of comedy!

Eating together is a central theme in many religions, going back to ancient Greece. The basic diet in Greece consisted mostly of grains. Meat was only eaten collectively after sacrifices to the gods, which anyone who can get through the first book of the Iliad without drooling will tell you.

It is hard not to bond with people when you eat together. Sometimes the act of eating together can be a tool of influence: business lunches, awards dinners, naked brunches, etc. Even a breakfast might be an opportunity to bond, as Thomas Macauly once said: “Dinner parties are mere formalities; but you invite a man to breakfast because you want to see him.” But can take-away meals be a way to disseminate culture and spread knowledge?

A new take-out restaurant that only serves cuisine from countries that the United States is in conflict with has open in Pittsburgh, PA. It is called Conflict Kitchen. This eatery is similar in concept to Michael Rakowitz’s 2004 project called Enemy Kitchen. The purpose of Enemy Kitchen was to use food to “open up a new route through which Iraq can be discussed. In this case, through that most familiar of cultural staples: nourishment.”

Enemy Kitchen, an ongoing project where Rakowitz collaborates with his Iraqi-Jewish mother. Compiling Baghdadi recipes, teaching the dishes to different public audiences. The project functioned as a social sculpture: while cooking and eating, the students engaged each other on the topic of the war and drew parallels with their own lives, at times making comparisons with bullies in relation to how they perceive the conflict.

Conflict Kitchen is a more commoditized version of Rakowitz’s project, using Iranian cuisine as a vehicle to market “rogue” state culture. Conflict Kitchen will have rotating menus, the next being Afganistan and then North Korea. In an interview with We Make Money Not Art, the creators of the project said that most Pittsburghers don’t know what the restaurant is all about, despite its having made international headlines. Besides creating a more commercially marketable Iran, the food counter brings people from all walks of life together to discuss everything from politics to religion while they wait for their food to be prepared. The creators use this opportunity to chat with the customers and “the conversation naturally goes to Iranian culture–perceptions and misperceptions–and often back to the customer’s own cultural heritage.”

I like the idea of promoting cultural awareness through cuisine, I guess it is the next best thing to having a study abroad experience. Maybe now people can go out, eat and get informed first hand instead of being force fed fear-mongering news by the American media. The main US propaganda machine, Disney, has a long history of using food to influence public opinion. 0ne of their most successful brain-washing campaigns, known as The Magic Kingdom, convinced millions of children and their families that all Mexicans shoot Churros from their fingertips on command, that all Germans walk around in lederhosen serving bratwurst all the live-long day, and that all Chinese children wear rice-picking hats and ride around on one-speed bikes and selling chop-sticks. What sort of chance does Conflict Kitchen stand against such Pavlovian methods of coercian? None whatsvever, but at least you get to eat somewhere that is officially more famous than the Carnegie Deli.

An Interview with Heath Bunting – Part 1

I first met Heath when I moved to Bristol (UK) in 1988. It felt important, even profound. Not in a ‘jump in a bed’ kind of way. Yet our meeting did seem life changing somehow, to the both us. We hit it off and we collided – as equals – our collisions resonated, it shook our imaginations. From then on our paths, our lives connected and clashed regardless. We regularly challenged each other through constant, critical duels of dialogue; about activism, art, technology and ideas surrounding different life approaches and philosophies. From 1988 – 1994 (just before the Internet had properly arrived), in Bristol and London we collaborated on various projects such as pirate radio, street art and the cybercafe BBS – Bulletin Board System. We then went our separate ways exploring our own concerns more deeply, but continued to meet every now and then. Us both meeting in Bristol changed both of our worlds, it built the grounding of where we are now.

Heath founded the Irational.org collective in 1995, a loose grouping of six international net and media artists who came together around the server irational.org. The collective included Daniel Garcia Andujar / Technologies to the People (E), Rachel Baker (GB), Kayle Brandon (GB), Heath Bunting (GB), Minerva Cuevas / Mejor Vida Corporation (MEX) and Marcus Valentine (GB).

Heath Bunting’s work manifests a dry sense of humour, a minimal-raw aesthetic and a hyper-awareness of his own artistic persona and agency whilst engaging with complex political systems, institutions and contexts. Crediting himself as co-founder of both net.art and sport-art movements, he is banned for life from entering the USA for his anti GM work, such as the SuperWeed Kit 1.0 – “a lowtech DIY kit capable of producing a genetically mutant superweed, designed to attack corporate monoculture”. Bunting’s work regularly highlights issues around infringements on privacy or restriction of individual freedom, as well as issues around the mutation of identity; our values and corporate ownership of our cultural/national ‘ID’s’, our DNA and Bio-technologies “He blurs the boundaries between art, everyday life, with an approach that is reminiscent of Allan Kaprow but privileging an activist agenda.”[1]

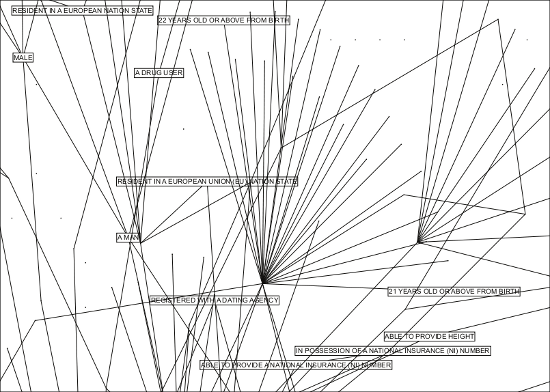

In this two part interview we will discuss his current work within two distinctive areas of digital culture and sport-art starting with The Status Project, which studies the construction of our ‘official identities’ and creates what Bunting describes as “…an expert system for identity mutation”. His research explores how information supplied by the public in their interaction with organisations and institutions is logged. The project draws on his direct encounters with specific database collection processes and the information he was obliged to supply in his life as a public citizen, in order to access specific services; also on data collected from the Internet and from information found on governmental databases. This data is then used to map and illustrate how we behave, relate, choose things, travel and move around in social spaces. The project surveys individuals on a local, national and international level producing maps of influence and personal portraits for both comprehension and social mobility.

Marc Garrett: For many years now, your work has explored the concept of identity, investigating the various issues challenging us in a networked age. The combination of your hacktivist, artistic approach and conceptual processes have brought about a project which I consider is one of the most comprehensive, contemporary art projects of our age. The Status Project, deals with issues around personal identity head-on.

Why did you decide to embark on such a complex project?

Heath Bunting:

Three reasons

1. the network hacker

the network hacker fantasises about unlimited access to all systems made available through possession of treasure maps, keys and navigation skills

2. the Buddhist

the Buddhist intends to destroy the self and become only the summation of environmental factors plus find enlightenment in even the most banal bureaucracy

3. the computer scientist

the computer scientist aims to find comfort and hidden meaning in complex data

I am all three and am attempting to combine the obsessions of each into one project.

So far I have

Created a sketch database of the UK system with over 8000 entries

Created over 50 maps of sub-sections of the system to aid sense of place and potential for social mobility

Created system portraits of existing persons

Created software to generate new identities lawfully (off the shelf persons) and sold these identities

I am currently adding more data to the database. Which is split between the human being (flesh), the natural person (strawman) and the artificial person (corporation). Remaking maps using upgraded spider software, researching how to convert my identity generating software into a bot recognised under UK law as a person; and hence covered by the human rights act i.e. right to life and liberty; freedom of expression; peaceful enjoyment of property. I am very close to achieving this.

Did you know that 75% of the human rights act applies to corporations as well as individuals? If you were afraid of corporations in the 90’s and noughties then be very afraid of the automated voices that speak to you on stations or programs that transact currency exchanges, as they will soon be your legal equals as with all Hollywood propaganda, the reverse is true. The human beings will be the clumsy, half wit robot like creatures serving the new immortal ethereal citizens. If you think I am mad or joking, check back in 10 years time.

MG: Way back in 1995, there were already various groups and individuals (including yourself) who were critiquing human relationships whilst exploiting networked technology. Creative people who were not only hacking technology but also hacking into and around everyday life, expanding their skills by changing the materiality, the physical and immaterial through their practice. It was Critical Art Ensemble (CAE) who in 1995 said “Each one of us has files that rest at the state’s fingertips. Education files, medical files, employment files, financial files, communication files, travel files, and for some, criminal files. Each strand in the trajectory of each person’s life is recorded and maintained. The total collection of records on an individual is his or her data body – a state-and-corporate-controlled doppelganger. What is most unfortunate about this development is that the data body not only claims to have ontological privilege, but actually has it. What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself. The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world. What we are witnessing at this point in time is the triumph of representation over being. The electronic file has conquered self-aware consciousness.”[2]

15 years later, we are dealing with an unstoppable flow of meta-networks, creeping into every area of our livng environments. We have mutated, become part of the larger data-sphere, it’s all around us. As you describe, it seems that we are mutating into fleshy ingredients, nourishing a technologically determined world.

HB: Data body is quite a good way to think about it. I consider each human being to possess one or more natural person(s) and each natural person to control or possess none, one or more artificial person(s) (i.e. corporation). The combined total of natural and artificial persons possessed or controlled by a human being can be thought of as their databody. As human beings, we have quite a lot of control over our persons (natural and artificial). The problem is that we either don’t realise this or it takes the time to manage them. It’s possible to obtain a corporation for less than the price of a train ticket between Bristol and London. Why do so many people live without one? Could anti corporate propaganda have something to do with this ?

“What is most unfortunate about this development is that the data body not only claims to have ontological privilege, but actually has it. What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself.”(CAE).[2]

Only if you remain a passive user of it. The natural person is only linked to the human being through such fine devices as a signature, which we decide to give or withhold, most human being’s natural person is actually owned by the government and borrowed back by the human being. This does not have to be the case as we can create and use our own persons.

“The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world. What we are witnessing at this point in time is the triumph of representation over being. The electronic file has conquered self-aware consciousness.”(CAE).[2]

I would say laziness has triumphed over mindfulness. All information about the functioning of natural persons is easily available, all persons have the same rights unless they choose not to claim them. Instead, people choose to get lost in their own selves and dreams, indulged by those that seek to profit from their labour.

Technology is becoming more advanced and the administration of this technology is becoming more sophisticated and soon, every car in the street will be considered and treated as persons, with human rights. This is not a conspiracy to enslave human beings, it is a result of having to develop usable administration systems for complex relationships. Slaves were not liberated because their owners felt sorry for them, slaves were given more rights as a way to manage them more productively in a more technologically advanced society.

MG: Getting back to the part of your project which incorporates a complex process of compiling and creating ‘off the shelf persons’, as you put it. Are you using some of the collected data as a resource to form these new identities, or is it a set of ‘hybrid’ identities?

HB: Please expand this question further…

MG: Near the beginning of the interview, you mention that you “Created software to generate new identities lawfully (off the shelf persons) and sold these identities.” I am asking whether most of these ‘new identities’ that you have formed and sold are, a mixture of different bits of information. Like data-versions of body parts from a machine or vehicle, reused, recycled to recreate, make new hybrid identities?

HB: The identities I can create are all new and legal, they are a portfolio of new unique legal relationships created with existing artificial persons. For example, registering with Tesco Clubcard either creates or consolidates the new natural person http://status.irational.org/identity_for_sale – for a new natural person to be credible, it must be coherent and rational. This is achieved simply by following the rules of the system, the more interrelating links with other persons, the more real the new person becomes.

Off the shelf natural person.

Comes with supporting physical items:

personal business cards, boots advantage card, marriott rewards card, cube cinema membership card, baa world points card, tesco clubcard, vbo membership card, WHSmith clubcard, silverscreen card, airmiles card, somerfield loyalty card, post office saving stamps collector card, virgin addict card, subway sub club card, dashi loyalty card, t-mobile top up card, european health insurance card, waterstone’s card, 20th century flicks card, bristol library card, co-operative membership card, nectar card, oyster card, bristol ferry boat company commuter card, love your body body shop card, co-operative dividend card, bristol credit union card, choices video library card, national rail photocard, bristol credit union account, bristol community sports card, star and garter public house membership card, first class stamp, nhs donor card, winning lottery ticket (2 GBP), t mobile pay as you go mobile and charger…

Upgradable to both corporate and governmental levels.

(500.00 GBP) – SOLD

MG: I can see on the web site, in the section The Status Project – Potentials that there are various ready-mades, ‘Off the shelf natural person – identity kits’. Am I right in presuming that there are individuals out there who have bought and used these kits?

HB: These are mostly existing persons, only one of them was synthetic. I will be setting up a small business soon though to manufacture and sell natural person.

MG: On exploring deeper into the Status Project data-base, there is link to a file called ‘In receipt of income based job seeker’s allowance’. This information is taken from ‘Jobcentre plus’, a UK government run organisation and on-line facility, inviting visitors to search for jobs, training, careers, childcare or voluntary work. How important was this source in compiling data for your database of individuals?

HB: This is only one record of over 8000 in the database, each record refers to one or more other record(s) in the database.

MG: What projects relate to/have influence on The Status Project in some way, and what makes them work?

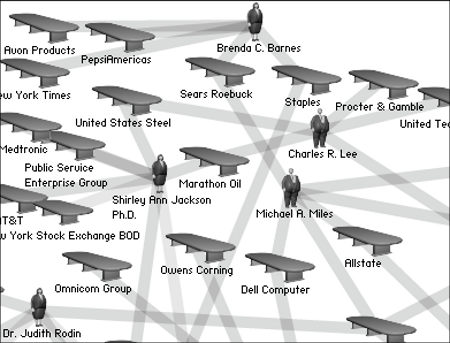

HB: They Rule[3] – It allows users to browse through these interlocking directories and run searches on the boards and companies. A user can save a map of connections complete with their annotations and email links to these maps to others. They Rule is a starting point for research about these powerful individuals and corporations. A glimpse of some of the relationships of the US ruling class. It takes as its focus the boards of some of the most powerful U.S. companies, which share many of the same directors. Some individuals sit on 5, 6 or 7 of the top 500 companies.

“Go to www.theyrule.net. A white page appears with a deliberately shadowy image of a boardroom table and chairs. Sentences materialize: “They sit on the boards of the largest companies in America.” “Many sit on government committees.” “They make decisions that affect our lives.” Finally, “They rule.” The site allows visitors to trace the connections between individuals who serve on the boards of top corporations, universities, think thanks, foundations and other elite institutions. Created by the presumably pseudonymous Josh On, “They Rule” can be dismissed as classic conspiracy theory. Or it can be viewed, along with David Rothkopf’s Superclass, as a map of how the world really works.”[4]

Bureau d’etudes – distribution.

http://bureaudetudes.org/

The Paris-based conceptual group, Bureau d’etudes, works intensively in two dimensions. In 2003 for an exhibition called ‘Planet of the Apes’ they created integrated wall charts of the ownership ties between transnational organizations, a synoptic view of the world monetary game. Check the article ‘Cartography of Excess (Bureau Bureau d’etudes, Multiplicity)’ written on Mute by Brian Holmes in 2003.[5]

MG: The sources of data for the Status Project seem to vary in type. Where do you collect them from and how do you collect the different kinds of data?

HB: It ranges from material instruments such as application forms right through to constitutional law and then common sense .

MG: How do you propose the Status Project might be used as a system for ‘identity mutation’?

HB: I want to communicate the fact that people in the UK can create a new identity lawfully without consulting any authority. I intend to illustrate the precise codification of class in the UK system, and there are three clearly defined classes of identity in the UK: human being, person and corporate . I am looking at the borders between these classes and how they touch each other, this can be seen with my status maps. Also, I intend to create aged off-the-shelf persons for sale similar to off-the-shelf corporations.

Taken from the front page of the Status Project:

Lower class human beings possess one severly reduced natural person and no control of an artificial person.

Middle class human beings possess one natural person and perhaps control one artificial person.

Upper class human beings possess multiple natural persons and control numerous artificial persons with skillful separation and interplay.

End of Part 1.

————–

Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Corrado Morgana

Come and celebrate with Furtherfield.org the recent publication of ‘Artists Re: Thinking Games’.

This is an unmissable event for all artists/gamers with a presentation by respected game artist Dr Mary Flanagan, a guest appearance by Jeremy Bailey and a display of some of the gameart featured in the book as well as an introduction by the editors.

Corrado Morgana – About the book.

Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett – Extra Context.

Guest Speaker – Mary Flanagan.

Guest Appearance – Jeremy Bailey.

Food and drink will be served.

At Birkbeck University of London’s Cinema

43 Gordon Square

Birkbeck, University of London.

London WC1H 0PD

Time 2pm – 4.30pm

Thursday June 10th 2010.

RSVP – contact ruth.catlow@furtherfield.org

Editors Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Corrado Morgana.

Digital games are important not only because of their cultural ubiquity or their sales figures but for what they can offer as a space for creative practice. Games are significant for what they embody; human computer interface, notions of agency, sociality, visualisation, cybernetics, representation, embodiment, activism, narrative and play. These and a whole host of other issues are significant not only to the game designer but also present in the work of the artist that thinks and rethinks games. Re-appropriated for activism, activation, commentary and critique within games and culture, artists have responded vigorously.

Over the last decade artists have taken the engines and culture of digital games as their tools and materials. In doing so their work has connected with hacker mentalities and a culture of critical mash-up, recalling Situationist practices of the 1950s and 60s and challenging and overturning expected practice.

This publication looks at how a selection of leading artists, designers and commentators have challenged the norms and expectations of both game and art worlds with both criticality and popular appeal. It explores themes adopted by the artist that thinks and rethinks games and includes essays, interviews and artists’ projects from Jeremy Bailey, Ruth Catlow, Heather Corcoran, Daphne Dragona, Mary Flanagan, Mathias Fuchs, Alex Galloway, Marc Garrett, Corrado Morgana, Anne-Marie Schleiner, David Surman, Tale of Tales, Bill Viola, and Emma Westecott.

In collaboration with FACT – http://www.fact.co.uk

http://www.furtherfield.org

http://www.http.uk.net/

Publisher: Liverpool University Press (31 Mar 2010)

Language English

ISBN-10: 1846312477

ISBN-13: 978-1846312472

http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/offer-listing/1846312477

Featured image: An interview with Chris Dooks, a ‘Polymath’ exploring various creative avenues, making his art using different media.

One of the many interesting and rewarding elements of being deeply involved in what, I’ll loosely term as ‘media arts’ practice, is the breadth of imaginative people you meet along the way. We first met Chris Dooks in 2005-6, when he worked with us on a project by Furtherfield called 5+5=5. We commissioned 5 short movies about 5 UK-based networked art projects exploring critical approaches to social engagement. These pieces offered alternative interfaces to the artworks and the every-day artistic practices of their producers. Including the motivations and social contexts of artists and artists’ groups working with DIY approaches to digital technology and its culture, where medium and distribution channels merge. Chris produced a film-work for the project called Polyfaith. A Psycho-Geographical Web Project introducing the beliefs and philosophies of his (invented) friend Erica Tetralix.

“My friend Erica Tetralix died. She gave me the task of fulfilling her dream which was that people would enjoy the parts of Edinburgh that were so dear to her in her life. She also loved tourists and sympathised with people on a budget, so she devised, with my posthumous help, this free way to enjoy the city. It’s a beautiful gift for both transients and residents. It’s popular with backpackers, parents and children, cultural groups and well, basically anyone.”

Later on we discovered that the name Erica Tetralix, is actually a name of a plant. Often called a cross-leaved heath, a species of heather found in Atlantic areas of Europe, from southern Portugal to central Norway, as well as a number of boggy regions further from the coast in Central Europe.

To view Polyfaith visit link below:

http://furtherfield.org/5+5=5/polyfaith.mov

The value of an interview is that it can serve as a useful documentation, a process allowing a kind of unfolding of time, All layed out in front of you. The reader can experience not necessarily a retrospective, but a dynamic and creative life and a personal history openly shared, on their own terms.

This interview reveals various levels and approaches by Chris Dooks. An inquistive and playful mind is at work here, engaged in exploring across different forms of personal agency, as well as redefining his practice in relation to the world he exists in, and the people he comes across in connection to various projects. His art is not a singular activity. Meaning, he does not rest in one particular art genre or movement. Instead, we are asked to acknowledge a personal enquiry formed from different engagements and choice of mediums, which happen to meet his creative intentions and questions at the time. We are all relational beings and Chris Dooks is a clear example of how this can work in an artistic context.

The Interview:

Marc Garrett: Many out there will already know you as a professional film maker, directing arts-based TV documentaries such as The South Bank Show in your twenties. Since then, you have developed other skills involving design, composing and making music, audio visual installations, explorative psychogeographical projects, as well as continuing making films, and you’ve even got a record deal. You have as far as I can gather four different music projects curently on the go, your electronica group BovineLife, an architecture music project known as As Ruby’s Comet, Feible for laptronica and also the Audiostreet project featured at The Leith Festival.

Chris Dooks: It’s amazing how many people still know me from Bovine Life which was a moniker I used for an internet audio project way before broadband in 1999. It’s the tenth anniversary of my bip-hop album SOCIAL ELECTRICS and I would like to make all my albums available for free for furtherfield readers. Don’t let itunes rob me of any money! The transition to musician was down in part to the South Bank Show when working with Scanner. I was really frustrated at making work about musicians. And the technology was making it easier for folks like me without a classical training. Here are three for you for free – check links below for free tunes at the bottom of the interview.

South Bank Show UK television documentary directed by Chris Dooks, featuring Robin Rimbaud speaking about his practice and ideas. 1997. Click here to watch video.

MG: In The Glasgow Herald, in Scotland a journalist called you a Polymath. Even though you were delighted to receive such a compliment in the local press, you decided to re-edit the term, reclaim it so to make it less seemingly mathmatical. Prefering Polymash because it sounds “friendlier, resourceful and potentially charming.” Sticking with this notion of you being a Polymath or rather a Polymash. Your diverse approach in creating art works in a non-singular approach, is a core element of your practice. I was wondering whether this is a deliberate decision or a natural and overall state of being?

CD: It’s weird though, I learned more in my background as a wedding videographer aged 14-19 (35 weddings at weekends!!!) than on any other course. Doing weddings gives you various skills as a digital artist. Fuck a film degree! As a wedding videographer, you need to be able to mike the vows in difficult audio environments (i.e. reverby spaces), film it about fifty feet away, liaise with highly emotional temperaments, be like a war photographer – it’s only gonna happen once, miss it at your peril – and stay sober. Not to mention edit it at a time when non-linear editing was non-existent, (I remember the heady days of “crash editing” between two panasonic VHS machines) white balancing everything on manual heavy equipment and creating all the graphic design and labelling of tapes. I was like a teenage record label!

So in 2009 when I made www.studio1824.com – making a record (netlabel) for an icehouse in Sutherland (remote Scottish Highlands) I got a kind of deja vu experience. Only with an education and life experience in the mix now.

When I was 8 years old, I had two epiphanies. One was that death is really gonna happen, and two, that cinema is wonderful, emotional and that it offers us a naive form of immortality. Cinema was the only artform that even at that age, I felt could make me feel…spiritual, for want of a better term. I became quite religious.

I was obsessed with super 8 cameras and video. And now I am trying to get all my pre-teen works tracked down! But even at this stage there was always a healthy distraction in other areas. I wouldn’t get involved with narrative and this has never been my strong point, even though I was reasonably good with words. My uncle played a lot of classical music and my dad took me all over the UK in his lorry, and at this time I won a scholarship to play the cello at school with the posh kids, being the other three. (It was a working class music “initiative”) But alas, I didn’t realise how lucky this was for me. So I went back to making videos, this “poly” approach was probably set quite early. I remember doing a kind of pre-Blair Witch thing when I was 14 and I would get sidetracked into filming the shapes of the leaves and the sound of the wind. Then I realised that the material didn’t make sense in the conventional sense. So I became an aesthete of kinds at an early age. And in every way, from Granny’s trifles and an early lust for Kate Bush, I was concerned with the sensual world. But until 22 I was monogamous to film projects and would work as a corporate director in the art school holidays to fund my college life, with the odd wedding video thrown in. By the time I did my film degree at Edinburgh College of Art, I was much more interested in people like video artists Bill Viola, Gary Hill and Daniel Reeves – (I met all three) via the “team-building” world of film shoots. Bill Viola’s THE PASSING changed my life.

The Passing, 1991. In memory of Wynne Lee Viola. Videotape, black-and-white, mono sound; 54 minutes.

Pre-degree, in those days (1989-91) you had to REALLY know your kit and be a good all rounder. I trained on huge Umatic machines and did a BTEC before a degree. I was from a part of a culture where there was no film degree, and I was a couple of years behind my peers. But by the time I hit ECA, I could mix radio programmes, edit timecode, black and white balance studio cameras and location kit and I spent most of the time buggering off to the hills to film Scottish waterfalls. I might have been techinically proficient and this was behind the poly approach to an extent, but I had bugger all conceptual skills. These have only really solidified in my thirties…

MG: Lets talk about the Surreal Steyning psychogeographic audio tour, part of the The Steyning Festival in 2009. On the web page for the project is written “This tour is simply a different way to skin the proverbial cat. In this case, the cat is Steyning. In fact, if you think of Steyning as a cat, you are already a psychogeographer. Well done. You’ve engaged your psyche with geography. You’ve mapped the town conceptually. The High Street becomes the cat’s spine with the head chasing Mouse Lane. Now you are in the same company as such artist groups as the Situationists, the Dadaist Movement and other high fallutin ripples in art tourism, and even The Ramblers.” Did those who took part manage to understand and appreciate where you were coming from? Also, how did it work?