Dave Young writes within the context of Localhost: RWX, a symposium and worksession at Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop from 29-31 October 2015. For more information about RWX, visit the Localhost website. RWX is funded by Creative Scotland, with support from New Media Scotland, Furtherfield, and Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop.

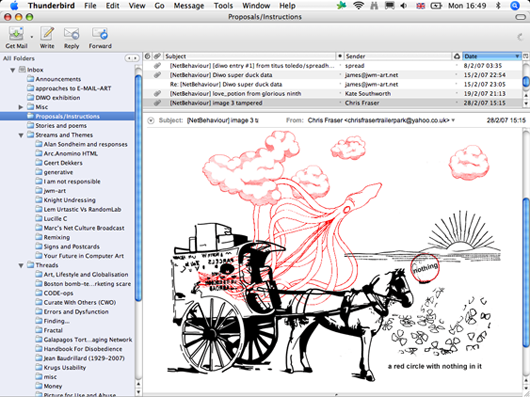

As smart devices shape the near future of personal computing, we – as users – are experiencing a shift in the way digital data is represented and accessed. For the last five years, Apple, Google and the other tech giants have desperately attempted to position themselves as market innovators and patent holders in the next generation of consumer tech. Over this period, we have seen more companies dropping desktop PC production in favour of novel gadgets such as smart phones, tablets, watches, fitness bands – and even contact lenses, glasses, and so on. A noticeable side-effect of this shift is that the ‘traditional’ filesystem interface, familiar to us as a visually traversable hierarchical structure of files and folders, is replaced by an app-centric interface. With its primary objective of being more user-friendly, this kind of interface limits as much as possible the tedious and touchscreen-hostile tasks of file management and directory navigation. It’s certainly worth reviewing how data should be represented in the modern Operating System – “tradition” is not enough reason to purposefully stick to an old system of files/folders, created by Xerox for their Alto/Star OS in the 1970s. That said, any radical change in the interface design of the filesystem needs to be critiqued, as it is acts as the mediator between us, our data, and our tools.

It’s worth emphasising that the aforementioned Xerox system is also a metaphor – it does not necessarily offer us a truer insight into the raw data on our devices than an app would. In the case of wanting to open a .txt file, whether we do this by selecting files via OSX’s Finder/Windows Explorer/one of the myriad File Managers in the world of Linux, or by opening an app on a “smart OS” such as iOS/Windows Phone/Android, we still achieve the same end goal: while the rudiments of the interface might change from one system to another, the .txt file is still utimately accessed and displayed to the screen. But between the traditional Xerox system and newer mobile interfaces, there is an interesting divergence. In the former instance, we navigate to the information, the precise location of the particular file /within/the/hierarchy/of/directories, then choose to open it with a tool of our selection. In the latter case, we select the tool, which then prescribes what information can be accessed with it. This simple inversion of intent does fundamentally alter our experience of the filesystem, but what’s at stake when we prioritise the choice of tool over the choice of file?

In the case of the former interface, we are provided with a visual map of our data. We can see where something is stored, how it relates to the other data we have saved, and also its related metadata. We are presented with an open scope, an indexical view of the files stored in our device’s memory. By default, we have the option of surveying data saved to our hard drive, and we can choose to ‘explore’ this should we so desire.

In the case of the typical smart OS interface, where the selection of a tool is prioritised over the selection of a given file, our vision of the filesystem is closed down by a “helpful” framework that only displays data that can be opened with a particular app. The messages app allows you to read your messages, the note-taking app allows you to speedily write notes, yet ne’er the twain shall meet – unless through a closed black-box framework, often labelled as ‘share’, which again guides you to an app that mediates your selection of file. As if peering through a keyhole, the user sees their filesystem in discreet parts and at particular moments, mediated by a given app’s functionality and filetype preferences.

It must also be said that, increasingly, much in-app data is often not even locally hosted on the device. It occupys no discernible, indexed space on its hard disk – at least no space that is visible and open to the user. Instead, it sits in a dynamic, transient “app cache”, where information is stored temporarily, to be frequently written, updated, and wiped without the user’s explicit knowledge or conscious intervention.

But this problem has a simple solution: why not just download a file manager from an app store?! It is of course an easy task to download a third-party file manager, but why was the filesystem manager done away with in the first place? Default configurations are rarely inert gestures. The omission of a stock file manager should be understood as a deliberate design decision intended to influence or shape the way we engage with the device. Is its omission, for instance, a desire to shake up what is seen as an antiquated interface? Is it a victim of contemporary design obsession about UI friction and clutter?

Searching for a file in a directory tree and not being able to find it can be seen as an example of friction. It is a moment where the ‘user’ becomes aware that they are ‘using’, activated by frustration or self-reflexive concentration and the necessity to make decisions, to search, to solve a problem. Finding the lost file is a terribly banale puzzle, but one that at least self-conciously engages the user. The app interface, which always tries to guess what you want to do next under its chief design objective of smooth simplicity, aims to remove friction. The smart OS is not free from friction though: when it guesses wrong, a manual solution can be more complex to rectify than the traditional filesystem interface, and perhaps at this point, the user realises they may not be as free to ‘use’ their technology as they expect.

Recently, we can see how some features of the smart OS are invading the desktop Windows, Mac and (to a lesser extent) Linux Operating Systems. Ubuntu, the most popular desktop Linux OS, raised controversy when its new Unity interface was unveiled in 2012, with a noticeably touch-friendly design aesthetic featuring large app tiles and fancy but pointless UI features. Was this part of the wider trend as demonstrated by Apple and Windows, where an ecosystem of multiple devices share smart and responsive interfaces, homogenous no matter the screen size, format, or method of interaction? Since then, Canonical (the parent company that develops Ubuntu) have attempted to venture into the smartphone market, working on both software and hardware, with an OS that neatly ties into the Ubuntu desktop experience. This approach to smart OS design is not simply a matter of convenience for the user, but good business sense too, especially as it becomes increasingly common for a technically adept individual to have a computer at home, a tablet in their bag, a phone in their pocket and a smartwatch on their wrist. Interface and brand go hand in hand: a suite of devices that play nicely together, share files conveniently over fancy wireless protocols, and look good when sitting side-by-side on a coffee table further encourages brand loyalty.

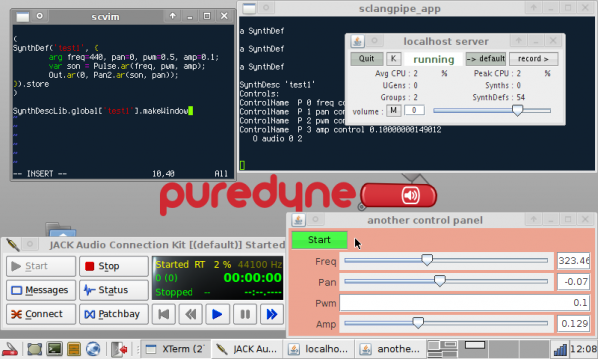

Despite its somewhat unforgiving text-based interface, it is the Terminal that perhaps offers the least mediation of all filesystem interfaces. Commands are taken as commands, presumed to be intentional and subsequently applied, whatever the consequences. When developed according to the UNIX philosophy of “do one thing and do it well”, command-line tools have the ability to “pipe” a standard output to an input of another tool – that is, each tool can share its output with the input of the next tool. Tools and files are thus recombinant, and in their purest form, are not hidden from one another. A basic example, featuring an ASCII cow:

ls -a #lists all files in the current directory.

. .. My_Computer.gif .shhh_super-secret.file

ls -a | cowsay #the standard output of 'ls -a' is piped into the standard input of cowsay. Hence, an ASCII cow lists out files for us.

_____

< . .. My_Computer.gif .shhh_super-secret.file>

-----

\ ^__^

\ (oo)\_______

(__)\ )\/\

||----w |

|| ||

Or for example, the ‘cat’ command dumps the contents of any file into the terminal. It does not really matter what you try to ‘cat’ – it could be an image, or whatever is in the RAM of your computer – if you have Read permission it will duly carry out your command.

cat My_Computer.gif #prints file contents to standard output

GIF87a+#)#� ######�##�#�##�����#�#���#�����������������������,####+#)###�0�I��8�ͻ�`(��X�h���T#p,�GR#m#�8��@#��[#�7b�#h:�Ndϴ##���U�d##P+��~u#�v9,{ ��`.#��o#Zbg'�bM{ }#mxjp#��"?�ak�xG+~S�K#��;KAA<'&��#'L"a����#����#���#?��0(���������##4�MŹ#�##��3�#����#�I�8�68��#z�����<���7���)��-l��ڼ�#� ����C##*�###;

sudo cat /dev/mem #prints the contents of a device's Random Access Memory to standard output

Yet, despite its direct and explicit interpretation of user input , we must return to the fact that the command line is a simulation – or more appropriately, an emulation – of a interface that mediates our relationship with the digital information stored on disk. Its commands recursively refer to lower-level frameworks and architectures, until it reaches the level of bits and electrical pulses.

Ultimately, when we discuss these issues about interface and access to information , we come to much greater issues surrounding the essence of memory and access to knowledge itself. As with any indexical system of information management (whether we speak of the archive, the library, the museum, or indeed the filesystem), there are inherent biases in the structures of representation that mediate and inform how we relate to the information contained within. There is a strong history of theorists (Jacques Derrida’s writing in Archive Fever being the obvious one) who attack the politics of the archive and our habits of designing biased frameworks for the storage of memory – certainly useful in these times, when we shift from one interface whose biases are familiar to another whose biases still somewhat elusive and in flux .

In the present though, it has become increasingly clear that the interface bias of the smart OS prioritises data-access and content-delivery, focusing on consumption rather than production. Maybe a filesystem manager is surplus to requirement for many, yet the ommission of such a perspective on our filesystem creates some issues for us as users. The phenomenon of ‘black-boxing’ – whereby complex activity is cloaked and opaque, incomprehensible and impenetrable to the user – becomes normalised. As a consequence, we can’t easily understand the behaviour of an app and the data it produces/accesses, we can’t explore what logs exist on our devices, and what personal data is potentially exposed to typical threats such as viruses, malware, hacks, and thieves. The perspective we have is simplified, and in this case, to simplify is to remove options, alternatives, and user-agency. The use-possibilities of our devices are parametrised, governed, and constrained by the overarching system of app-centricity, while opportunities for subversive intervention and creative misuse are reduced as we are obliged to act and respond within the increasingly powerful context of app store regimes.

Those orphaned config files, scripts, metadata, caches, loggers and logs: they will continue to reside in our most obscure, exotic directories, unseen, but saved.

—-

Also Read

* Turing Complete User – Olia Lialina

* Preface to FLOSS+Art – Aymeric Mansoux and Marloes de Valk

* McKenzie Wark – A Hacker Manifesto

* The Interface Effect – Alexander Galloway

Many of both Bitcoin’s most vocal proponents and detractors agree that the way the cryptocurrency operates technologically determines the form of the economy and therefore the society that uses it. That society would be anarcho-capitalist, lacking state institutions (anarcho-) but enforcing commodity property law (capitalist). If this is true then Bitcoin has the potential to achieve a far greater political effect than financial engineering efforts like the Euro or quantitative easing and with far fewer resources. Perhaps variations on this technology can create alternatives to Bitcoin that determine or at least afford different socioeconomic orders.

Bitcoin is already more than half a decade old and “Crypto 2.0” systems that build on its underlying blockchain technology (the blockchain is a network-wide shared database built by consensus, Bitcoin uses it for its ledger) are starting to emerge. The most advanced allow the creation of entire organizations and systems of organization on the blockchain, as Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs). We can use them to help create those different socioeconomic orders.

Workers’ Councils are a Liberatarian Socialist system of organization. Rather than implementing Soviet-style centralized command economies, workers councils are decentralized and democratic. Workers in a particular workplace decide what their objectives are then appoint temporary (and instantly revocable) delegates to be responsible for them. Workplaces appoint representatives to local councils, local councils appoint representatives to regional councils, and so on, always temporarily and revocably. It is a system of face to face socialisation and political representation rather than top-down control.

This system emerged at various times in Europe, South America and the Middle East throughout the Twentieth Century. It is a very human method of governance, in stark contrast to the “trustless” code of Bitcoin as well as to the centralized politics of the Soviets. That said, technology can assist organization as easily as it can support material production. In the 1970s the cordones of Chile interfaced with the Allende government’s Project Cybersyn network, and contemporary online workers collectives can use the Internet to co-ordinate.

A DAO is a blockchain-based program that implements an organization’s governance and controls its resources using code rather than law. There can be a fetishistic quality to the idea of cold, hard, unyielding software perfect in its unambiguous transparency and incapable of human failing in its decision making. There can be similar fetishistic qualities to legal and political organizational perfectionism, this doesn’t disqualify any of their subjects as useful ideals however they need to be tempered pragmatically.

Using the public code and records of a DAO can help with the well known problem of structurelessness, and can store information more efficiently and reliably than a human being with a pen and paper. The much vaunted trustlessness of cryptovurrency and smart contract systems can help build trust in communication within and between groups – cryptographically signed minutes are relatively hard to forge although the ambiguity of language is impossible to avoid even in the mathematics of software.

The delegates of a workers’ council can be efficiently and transparently voted on, identified by, and recalled using a DAO. This makes even more sense for distributed groups of workers, groups that share a common cause but lack a geographic centre. Delegates can even be implemented as smart contracts, code written to control resource allocation and evaluate performance in the pursuit of their objective (unless recalled by the council that created them).

Entire councils, and inter-council organisation, can be supported or implemented in their organization as DAOs. Support includes communication and record keeping. Implementation included control of resources, running delegates as code, and even setting objectives for delegates programatically.

The latter finally brings the concept of DAOs into direct conflict with the spirit of the Workers’ Council. Councils exist to allow individual human beings to express and agree on their objectives, not to have them imposed from above. Being controlled by code is no better than political or economic control. It is the nature of this relationship to code, politics or the economy that is positive or negative – writing code to charge someone or something with seeing that a task be undertaken is no different from writing it in the minutes and makes mroe explicit that organization is production as the subject of work in itself. A democratic, recallable DAO that sets objectives is very different from a blob of capital with unchangeable orders to maximise its profits online.

The resources that a DAO controls need not be monetary (or tokenized). A DAO that controls access to property, energy or other resources can contribute to avoiding the pricing problem that conventional economics regarded as a showstopper for the Soviet cybernetic economic planning of “Red Plenty“. DAOs need not even be created to represent human organization – “deodands” can represent environmental commons as economic actors. These can then interact with workers council DAOs, representing environmental factors as social and economic peers and avoiding the neoliberal economic problems both of externalities and privatisation.

Workers Council DAOs – Decentralized Autonomous Workers Councils (DAWCs) are science fiction, but only just. Workers councils have existed and been plugged in to the network, structurelessnes and scalability are problems, DAOs exist and can help with this. Simply tokenizing “sharing economy” (actually rentier economy) forms, for example replacing Uber’s taxi sharing with La’zooz, while maintaining the exploitative logic of disintermediation isn’t enough.

If we are unable or unwilling to accelerate the social and productive forces of technology to take us to the moon, we can at least embrace and extend them in a more human direction.

The text of this article is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

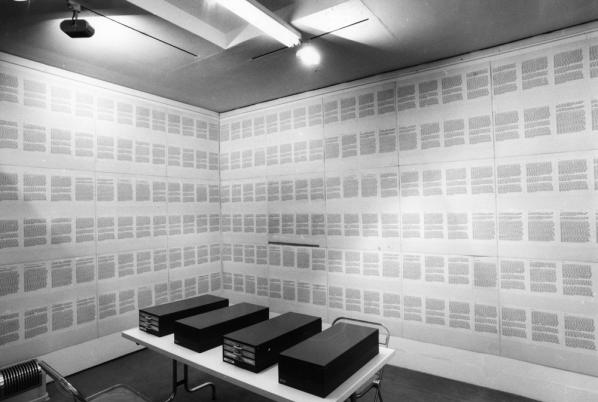

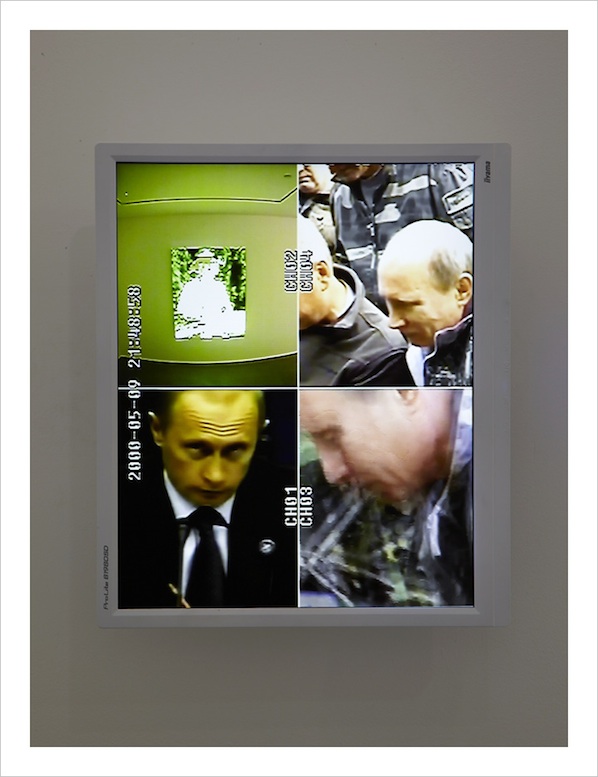

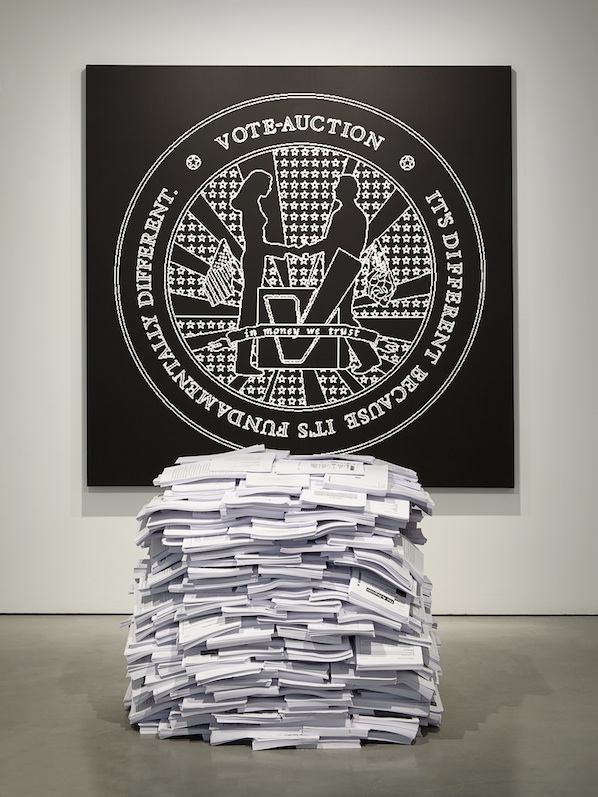

Featured image: Aram Bartholl, Forgot Your Password?, 2013

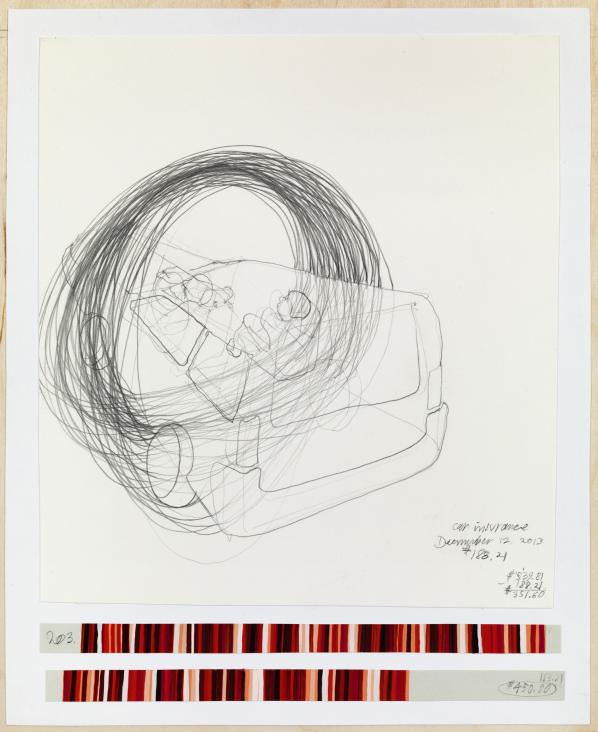

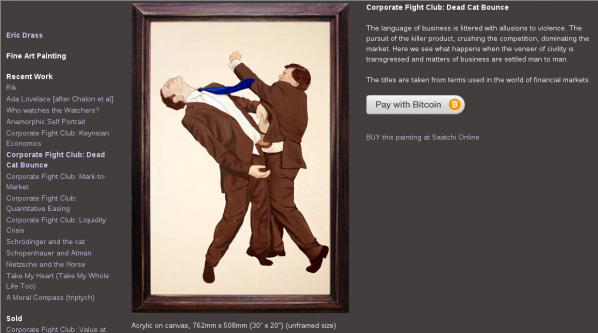

Historical art is developed by way of its respective era and society, meaning that it is always made in the present. Today, new technologies open up new possibilities for artistic potential. Currently, art production, which is influenced by new technologies, is reacting strongly to the changing times. Artworks are being created, which react to digitalisation, even if they don’t necessarily reflect the digital format itself (i.e. like works by Aram Bartholl).

In its purest form, digital art is ephemeral and based on a transient technology. The continual advancement of the technology demands on-going improvements; challenges from which many emerging artists refuse to be deterred. On the contrary: the monthly quota of events related to digital art proves the high level of interest around the form.

The global technical networks thereby bring about new atmospheres, or perhaps, infospheres, as media theorist Peter Weibel calls them. In the art world, previously held art-historical considerations are forced towards a re-evaluation. Conventional theories and practices must be called into question. New art forms in the immaterial digital domain demand a general rethink in terms of their conservation, presentation and acquisition. And, of course, the reception of digital art is also different.

According to studies by Hiscox, a preference for original works still dominates both in conventional and online trade. Authenticity and intrinsic value continue to be important criteria when it comes to decision-making regarding the purchase of art. Transparency will remain, for the long term, a fundamental prerequisite for the establishment of trust.

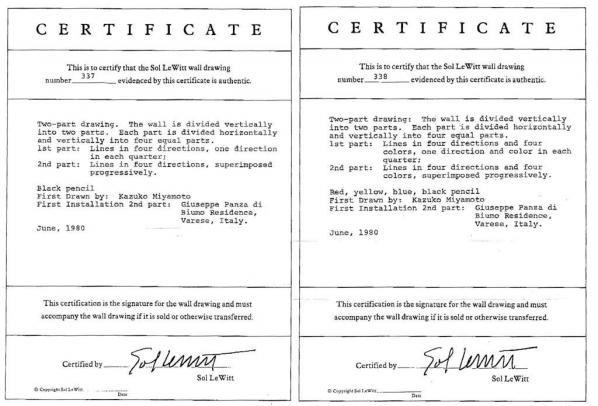

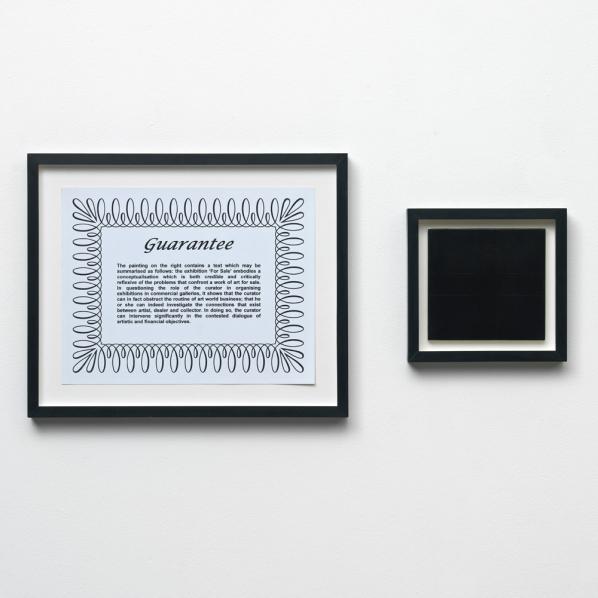

Most acquisitions of digital art take place conventionally by way of galleries. If a collector acquires, for example, a website, then the gallerist sells he or she a domain (which is unique!) and transfers in-addition, a licence contract. This is a material document. The ‘network’ remains virtual, while retaining open all of the attributes of an artwork in the source code, i.e. the artist’s signature, the title, the year in which it was produced, the technique, and information on the programmer or the collector.

The collector can enjoy the work beyond the confines of time and physical location. Simultaneously, he or she is responsible for its preservation, which is the guarantee for the continuation of its existence over time.

Internet art in general is dependant on software, but above all it relies on hardware (computer, hard-drive, interfaces, sensors, monitors, projectors, etc.). Yet for how long will the hardware remain a part of our interactive culture? Forward-looking collectors purchase, in addition to the contract, a series of devices that safeguard the work for the future.

The ability to learn about new approaches in our fast-moving culture occurs both naturally and dynamically. The art market is an extremely non-transparent market, access to the right networks and contacts. Is this likely to change any time soon?

Art history shows us that artists are ahead of their time, anticipating what is to come. One need only cast an eye around the scene, in order to open the door to new ideas and technological marketing methods in the art world.

The German artist, Stephan Vogler, has already done this and in cooperation with a law firm has unleashed intelligent synergies. The artist himself produces digital files – intangible goods, as he calls them – which should also naturally migrate to the art market over the long-term, in the best case scenario, as unique pieces which one – such is the thinking within his system – can acquire with Bitcoin.

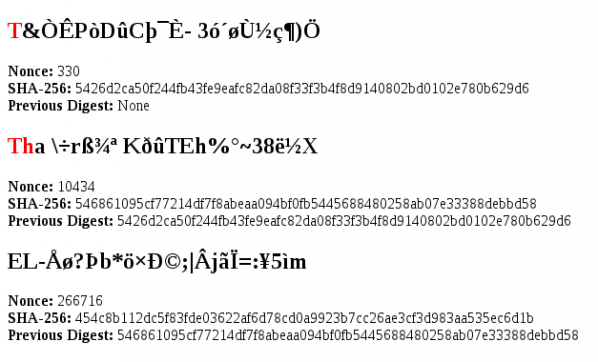

Far more interesting than the means of purchase, is the Bitcoin technology that lies behind it.

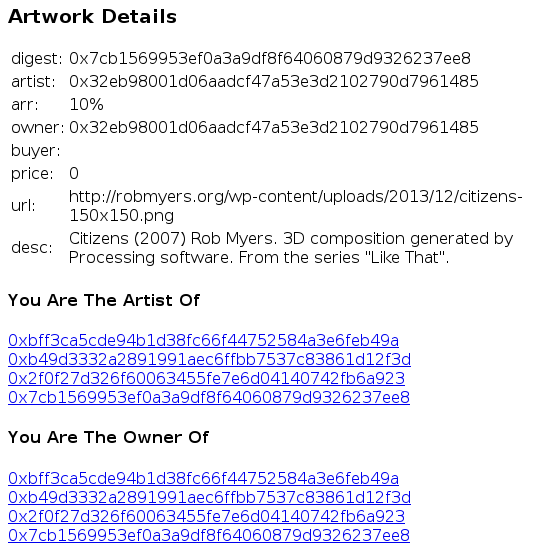

Stephan Vogler has developed a licence together with experts on legal practice within the art world, which transforms the digital artwork into an independently tradable virtual commodity, which is limited, both in terms of its technology and its legal rights. The system is based on a license agreement under the utilization of the Bitcoin technology. All works will come with an electronic signature, which is recognized, in legal terms, as being an original signature. This also serves as proof that the files existed at a given moment in time. Their authenticity is mathematically verifiable and the right of resale is exclusive. Virtual ownership is technically and legally limited to the respective owner. The owner of the usage rights is registered in a decentralized Bitcoin Blockchain, and the rights regarding the work are assigned through a Bitcoin transaction. In this way, digital artworks become both tradable and collectable objects without the requirement of their materialisation. Purchase and transaction take place simultaneously and the function of the custodian is eliminated. The structure behind the acquisition is thereby extremely transparent.

Artists like Stephan Vogler want to revolutionize the market for digital art through new technology. But independent from this fact, the art world is not sleeping. Collectors, institutions and art market platforms are already taking note.

For example, Austria’s Museum for Modern Art (MAK) has already bought an artwork with Bitcoin.

Cointemporary.com, a curated online platform, offers ephemeral artworks at a fixed Bitcoin (BTC) price – independent from the actual exchange rate. Berlin company ascribe.io develops systems within the Blockchain technology and offers services for art experts, assisting in the professional management of their digital files, i.e. their registration, archival, transfer of ownership etc.

The Winklevoss twins are known as great advocates of the digital currency. Rumours about investments in the art form are rife.

The acquisition of artworks via Bitcoin sounds forward-looking and simple yet should be enjoyed with a good degree of care. The reason for this is that Bitcoin is not controlled by a state and its central bank, but rather is generated by Internet users by way of complicated arithmetic calculations. So what might be the advantage of a Bitcoin purchase?

Collectors of digital art, such as the Belgian, Alain Servais, or Hampus Lindwall, from Sweden, view the purchase of work via the risky Bitcoin currency with scepticism.

It is still too early to really be able to judge the effects of these developments. Ultimately, the discussion as a whole concentrates far less on the system of currency than on the technology itself, which can also be applied to other circumstances. These experiments will only truly bear fruit through the development of a high degree of know-how, the courage to take on legal consequences at the moment of purchase, and through simple decisions in a user-friendly design.

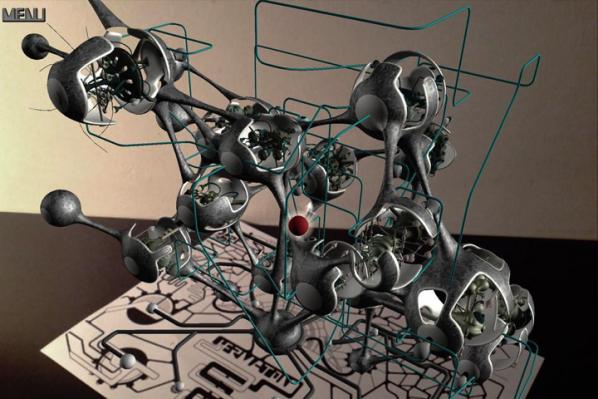

Structures. Something has been built, grown, stretched. Maybe skin, maybe a web, maybe a protective barrier – it is a plastic protein emitted by an organism in order to increase its survival opportunities, it is a food matrix for its offspring which thrive on glossy resin. You can travel across it and it can easily be mapped, although not by humans.

We can’t say anything about it – we can speculate everything about it. It is something possible or as the author says another reality. The real is replaced by the potential. This is one of a series of works by St. Petersburg-based artist Elena Romenkova. The works are glitches, abstract distortions, alien expressions of what for her is a subconscious realm.

A portal. You are entering the rainbow world contained within two concentric eggs within the grey world. This is light, reflections, haze, indescription. It looks inviting. The colour spectrum is odd, the whites creep up on everything else, the shape of everything is strange. Basic synaesthetic rules are inapplicable at the rainbow/grey world junction.

There is nothing that this image, by French artist Francoise Apter (Ellectra Radikal), has in common with Romenkova’s. They are united only by their adherence to strangeness, a technically created vista that looks like nothing we know. A world not of local cultures, but of computational production. Here anyone can know anything, it doesn’t matter where you’re from.

What is culture when locality is secondary to epistemology? What is knowledge when the portable device takes precedent over your situated environment? Worlds are built around us, sophisticated electrical spaces, they travel where we travel, and only after do we factor in the idiosyncracies of specific geography. If the banal experience is one of nomadic alienation, of search methods based on no place, what does the role of culture and art become? Everyday life is a subject for hypothetical language. The digital commons is a species of posthuman that communicates via speculative misunderstanding.

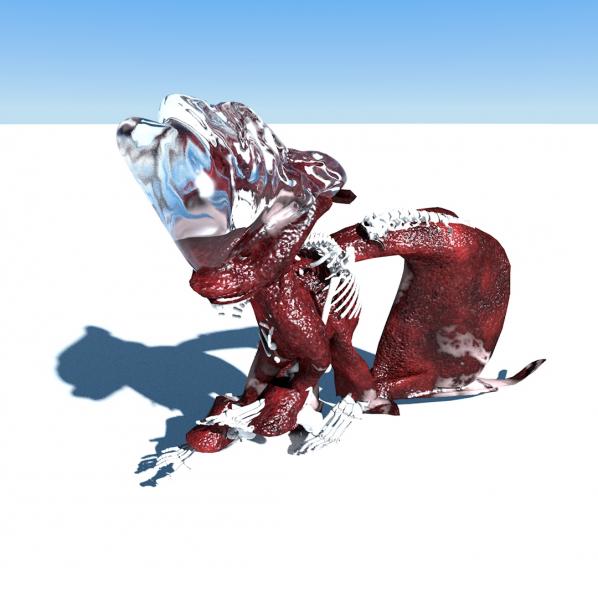

Korean artist Minhyun Cho (mentalcrusher) shows us what the dinosaurs really looked like. When you put the meat and scales back on. He shows us what an ice building being looks like in the shadow of terminal cartoon winter. How rubber can be used to erect sculptures and bones can be taken out of museums and put to good use in civic architecture. No one is around to see this, but still the idea sets a precedent. Crown each ghost with ice mountain prisms.

With visual language, very quickly we get to a stranger and more indeterminate range of science fiction possibilities than narrative tends to map out for us. How much imagination is possible, and how much does our internal experience match anything presented around us. If our environments advance exponentially quicker than any generational or traditional mythology, what sort of language can we have for expression? The maker’s invention precedes the reception of form. Innovation is a matter of banal activity, communicating an experience of the real which is never the same.

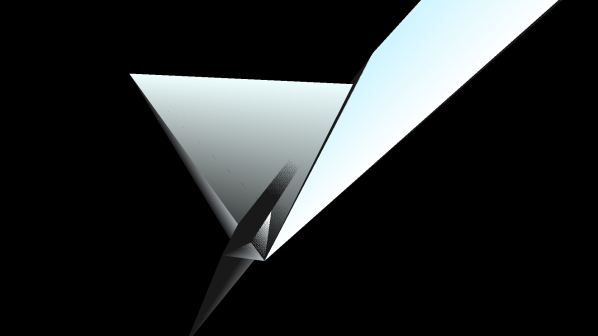

And now an eyeball. Triangles. A vessel. To Cho’s blinding world of light, Spanish artist Leticia Sampedro responds with a featureless darkness. All absurdities once on display, now they recede into nothing. It might be a mandala, perhaps an artifact from the ancient future, a portable panopticon that fits conveniently on your desktop. Your feelings are here, your peculiar distances, everything’s reflecting off the glass, the metal, the camera. You are the mirrored fragments of an invention we’ve lost the blueprints to. Foresight the womb of a disembodied politics of community.

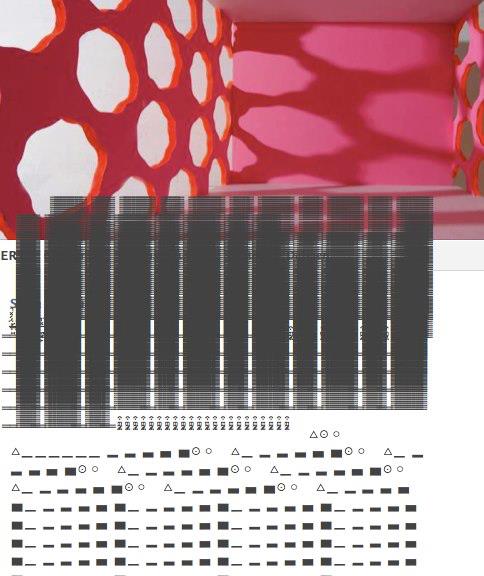

Community held together by structures. In German artist Silke Kuhar‘s (ZIL) work, we enter into one of these structures. Inside we find hallways, a nice selection of windows and all kinds of data – scripted, graphed, symbolized. This is the plan for the future. I hope you can read what it says. Her work meshes spaces with collapsing foreign constructs – if we can just read the language we’ll know what to do. But no one reads it, and no one wrote it. This is a building without inhabitants – architecture without people. Democratic ballots are automatically filled out by a predetermined algorithm. Your agency is a speculative proposition for popular media – people collaborate with you, but they can’t be sure where you are, when you wrote, and if you really exist as such.

No people. This is a unifying principle. Cold, silver, streams. Machines in the sky. Silicon waterfalls, diagonal. Civilization distilled into physical patterns, an obtuse object photographed in another dimension. What is the word for reality again. What is the word for scientific investigation? A Venezuelan based in Paris, Maggy Almao’s abstract glitch world is silent – it’s a gradient, it’s some illusion of partial perspective.

What is the language to talk about the world? If we turn to artists’ visualizations, what does that tell us about languages we speak, and ones we read? What does the graphing of incomprehensible mechanisms tell us in turn about art and its history? The machine’s narratives tend to drown out any functional reality. Genre storytelling tropes become repurposed as collective cultural ideas. Conceptual works are followed by pragmatic speculation, medium-centric analysis replaced by experimental failures. You can never get a fictional experiment to work.

Science has indelibly entered the art field, for each of its medial innovations it requires further attention in terms of its technical makeup. Half the work is figuring out what the canvas even is, we are building canvases, none of them look alike, and their stories read like data manuals. An aesthetics of unknown information.

This is the homeland. The homeland is mobile and has many purple bubbles. It’s an airship from the blob version of the Final Fantasy series. It has satellite TV to keep in touch with the world. It has some tall buildings so you know it’s civilized. It is part of Giselle Zatonyl, an Argentine-born Brooklyn-based artist’s opus which deals comprehensively with science fiction ideas and their implications.

The ship travels, where the culture originates is more and more unknown. It is technically divided, access is the key, we can worry about language and culture later. We are still embodied, still located somewhere, but all this has become subject to the trampling of scientific mythologies, where their utilities might go, and where their toys are most needed. Crisis is a genre now, about as popular as time travel. You are now free to dream up whatever future society you wish, and subjugate whatever cyborg proletariat your heart desires. In the realm of speculation, anything is possible, and nothing is fully acceptable.

The themes of internet art production give us some language, some set of visions that tell certain stories – works found throughout the internet, posted in communities, shared online – sometimes part of gallery exhibitions or products, sometimes not. You get a profile, some social media pages, build a website, you begin making, sharing and remixing images. Folk art is a subsidiary of new media art – social sculpture meets internet content management systems. A language for political engagement based on the creative activity of speculation. Scientific dreams for a technological commons.

Dreams where sight is physicalized into complex data graphs. Where Sampedro’s portable gelatin panopticon is cloned into a regularized matrix. Inspired vision is just one aspect of algorithmic predictability. In Taiwanese artist Lidia Pluchinotta‘s visual work, the cloned image is central. Mechanical reproduction, skulls, spirals, symbols, the internet has it all. Civic participation has never been so mathematical, observation never so multiple.

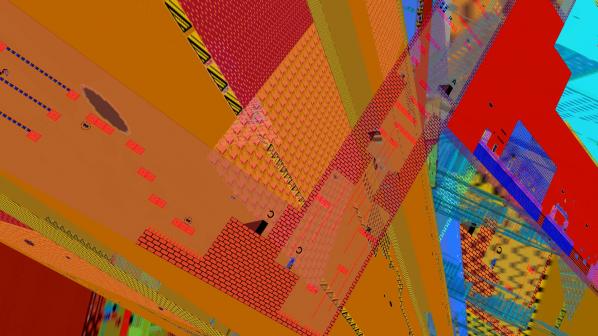

Inside the city, architecture is actually a colour-coded map that helps you find the store you’re looking for. The map is the territory except there’s no info on how to read it. We are here, we are home, but the walls of the buildings were designed by some specialist that we haven’t met yet. Stairs, depths, the complex and layered constructions in Canadian artist Carrie Gates‘ work aren’t quite one of Zatonyl’s buildings. More fragmented, more saturated, more chaotic. It’s speculated that people could live here, although we don’t see them anywhere. Not yet anyway.

The maelstrom of technological progress presents us with the need to adapt our participation and rhetoric accordingly. Science fiction is a folk language for common experience within a technoscientifically oriented world. These images are imaginative products of social and participatory artist communities who, when marrying the personal and contextual, create speculative objects of general strangeness. Their description is nothing less that one of alien entities – alien entities that are everywhere. Earth is the most sophisticated foreign planet we’ve yet to invent, we just need to discover how to populate it.

Those were the words I noticed when interviewing Augmented World Expo organizer Ori Inbar several days before AWE2015, the trade show of Augmented and Virtual Reality. “We’re not in beta anymore…” Inbar said, “We now have companies implementing enterprise-scale Augmented Reality solutions, and with coming products like the Meta One and Microsoft HoloLens, the consumer market is being lined up as well.” With the addition of the UploadVR summit to AWE2015 the event was a blitz of ideas, technologies and new hardware.

AWE/Upload is a trade and industry event that also includes coverage of the arts and related cultural effects, although it is smaller when compared to the industrial aspect of the show. In this way it is similar to SIGGRAPH and this is much of my rationale for covering this, and also SIGGRAPH later this year? Doing so is as simple as McLuhan’s axiom of “The Medium is the Message” or, better yet, examining how developers and industry shape the technologies and cultural frameworks from which the artforms using these techniques emerge. The issue is that in examining emerging technologies we can not only get an idea of near-future design fictions but also the emerging culture embedded within it.

To put things in perspective, Augmented Reality art is not new, as groups like Manifest.AR have already nearly come and gone and my own group in Second Life, Second Front, is in its ninth year. Even though media artists are frequently early technology adopters, what appears to be happening at the larger scale is a critical mass that signals the acceptance of these new technologies by a larger audience. But with all emerging technologies there is drama driven by those industries’ growing pains. For AR & VR the last two years have certainly been tumultuous.

Last year’s acquisition of Oculus Rift by Facebook sent ripples through the technology community. Fortunately, unlike my upcoming example, the buyout did not eliminate the Rift from the landscape; instead it gained venture capital allowing for licensing of the technology for products like the Sony Gear VR. Also the current design fictions being distributed by Microsoft for its Hololens give tantalizing glimpses of a future “Internet of No Things” full of virtual televisions and even ghostly laptops. This was suggested in a workshop by company Meta and the short film “Sight”, in which things like televisions, clocks, and objective art might soon be the function of the visor.

However disruptive events also happen in the evolution of technologies and their cultures. The news was that scant weeks before the conference a leading Augmented Reality Platform, Metaio, was purchased by Apple. Unlike the transparency and expansion experienced by Oculus the Mataio site merely said that no new products were being sold and cloud support would cease by December 15th. In my conversation with conference organizer Ori Inbar we agreed that this was not unexpected as Apple has been acquiring AR technologies, which has been related in rumors of “the crazy thing Apple’s been working on…”; But what was surprising was the almost immediate blackout, part of the subject of my concurrent article “Beware of the Stacks”. For entrepreneurs and cultural producers alike there is a message: Be careful of the tools you use, or your artwork (or company) could suddenly falter in days beyond your control. Imagine a painting suddenly disintegrating because a company bought out the technology of linseed oil. Although this is a poor metaphor, technological artists are dependent on technology and one can see digital media arts’ conservative reliance on Jurassic technologies like Animated GIFs for its long-term viability, but to go further I risk digression.

Another remarkable phenomenon this year was the near-assumption of the handheld as a experience device, and their use seemed almost invisible this year. What was evident was a proliferation of largely untethered headsets, ranging from the Phone-holding Google Cardboard to the Snapdragon-powered (and hot) ODG Android headset, boasting 30-degree field of view and the elimination of visible pixels. In the middle is the tethered, powerful Meta One headset with robust hand gesture recognition. Add in the conspicuously absent Microsoft Hololens and the popular design fictions of object and face recognition are emerging.

That is unless you are a brave early adopter, developer, or enterprise client. The fact that there was an entire Enterprise track and Daqri’s release of an AR-equipped construction/logistics helmet made it clear that the consumer market, much more prevalent last year, has clearly been placed in the long-term. For now, consumer/artistic AR is largely confined to the handheld device, as experienced through Will Pappenheimer’s “Proxy” at the Whitney Museum of American Art or Crayola’s “4D coloring books” in which certain colors serve as AR markers. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as an audience is likely to have a device that can run your app through which they can experience the art. As an aside, this is the reason why I chose to use handhelds for my tapestry work – imagine trying to experience a 21’ tapestry with a desktop using a 6’ cord! At this point, clarity and function, both partially dependent on computer power, have created a continuum from strapping your iPhone to your forehead like a jury-rigged Oculus for under $50, to potentially using a messenger bag with the Meta at $512, to the expensive ($2750), hot, but elegant ODG glasses you might try on if you visit the International Space Station.

While discussing the general shape of technology gives a context for its content and application, a media tool is often only as good as its app. Without meaning to show favoritism, Mark Skwarek’s NYU Lab team has been going outstanding work from a visualization of upcoming architectural developments to a surprising proof of concept for a landmine detection system, which I thought was amazing. Equally innovative was the VA-ST structured light headset for the visually impaired, which has several modes for different modes of contrast. These alternate methods not only was surprising in terms of application and possible creative uses but also changed my perception of AR as possessing photorealistic, stereoscopic overlays.

Other novel applications included National Geographic’s AR jigsaw puzzle sets, of which I saw the one outlining the history of Dynastic Egypt. I felt that if I were a kid, building the puzzle and then exploring it with AR would seem magical. There are other entertainment and experimentation platforms coming online like Skwarek, et al’s “PlayAR” AR environmental gaming system. But one platform I want to hold accountable for still being in late beta is the” LyteShot” AR laser tag system, which got an Auggie Award this year. My pleasure in the system is that the “gun” per se is Arduino-based, meaning that it could be a maker’s heaven. It uses the excellent mid-priced Epson headset, but at this time it is used primarily for status updates although there is a difference between AR and a heads-up display. So, from this perspective, it means that there are some great platforms getting into the market that are highly entertaining and innovative, but there are a few bugs to work out.

For the past thousand words or so I have been talking about the industry and applications of AR, but for me, my “soul”, if you will, set on fire during the “idea” panels and keynotes. For example, on the first day, Steve Mann, Ryan Janzen and the group at Meta had a workshop to teach attendees how to make “Veillometers” (or pixel-stick like devices to map out the infrared fields of view of surveillance cameras. Mann, famous for creating the Wearable Computing Lab at MIT and being Senior Researcher at Meta, still seemed five years ahead of the pack, which was refreshing. Another inspirational talk was given by one of the progenitors of the field, and inaugural Auggie Award for Lifetime Achievement, Tom Furness. His reflection on the history of extended reality, and his time in the US Air Force developing heads-up AR was fascinating. But what was most inspirational is that now that he is working on humane uses for augmentation systems such as warping the viewfield to assist people with Macular Degeneration. This, in my opinion, is the real potential of these technologies. In fact this array of keynotes was incredible, with Mann, Furness, the iconic HITLab’s Mark Billinghurst, and science fiction writer David Brin, (who comes off near-Libertarian) gave vast food for thought.

Every year, the Augmented World Expo gives out the “Auggie” awards for achievements in technology, art, and innovation in AR. I think it should be noted that the Auggie is probably the world’s most unique trophy, consisting of a bust that is half naked skull and half fleshed head with a Borg-like lens with baleful eye wired into that head. The Auggie is another aspect of AWE that signals that the world of Reality media is still a bit Wild West.

There are several categories from Enterprise Application to Game/Toy (LyteShot having won this year), and many of them are largely of interest strictly to developers. For example, the fact that Qualcomm’s Vuforia development environment won three years in a row gives hint to its stability in the market, and Lowe’s HoloRoom is a wonderfully strange mix between Star Trek and Home Improvement. The headset winner was CastAR, a projective/reflective technology where polarized projectors were in the headset instead of cameras, which worked amazingly well. The other winners were gratifyingly humane applications such as Child MRI Evaluation and Next for Nigeria (Best Campaign). The prizes impressed on me that the community, or part of it, “got it” in terms of the potential of AR to help the human condition, which is perhaps a “superpower” that the conference framed itself under.

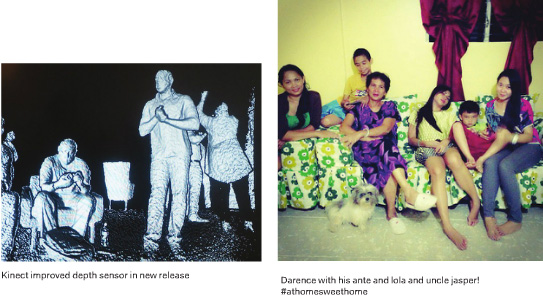

Being that I am writing this for an art community it would be of interest to know where the art was in all of this. The Auggies have an Art category, as well as a gala between the end of the trade show events and the Auggie Awards. The pleasant part about AWE’s nominations for the best in AR art is that those works have integrity. Manifest.AR regular Sander Veerhof was nominated for his “Autocue”, where people with two mobile devices in a car can become the characters of famous driving dialogues (“Blues Brothers”, “Pulp Fiction”, “Harold and Kumar”). Octagon’s “History of London” is reminiscent of the National Geographic puzzles, except with far greater depth. Anita Yustisia’s beautiful “Circle of Life” paintings that were reactive to markers were on display in the auditorium but, besides a Twitter cloud and a Kinect-driven installation, the art was swamped by the size of the auditorium.

The winner of the art Auggie, Heavy & Re+Public’s’ “Consumption Cycle”, (which this writer saw at South by Southwest Interactive) was a baroquely detailed building sized mural of machinery and virtual television sets. I feel a bit of ambivalence about this work, as Heavy’s work tends to rely on spectacle. Of the lot I felt it did deserve the Auggie, purely for its execution and the effective use of spectacle. But with the emerging abilities of menuing, gesture recognition, and so on, I felt that last year’s winner, Darf Designs’ “Hermaton”, employed the potentials for AR as installation in a way that was more specific to the medium.

Yes, but it was in a much smaller area than the AR displays. There were standout technologies, like the Chinese Kickstarter-funded FOVE eye-tracking VR visor, a sensor to deliver directional sound, and Ricoh’s cute 360 degree immersive video camera. The Best in Show Auggie actually went to a VR installation, Mindride’s “Airflow”, where you are literally in a flying sling with an Oculus Rift headset. Although a little cumbersome, it was as close to the flying game in the AR design fiction short, “Sight”. So, in a way, the ideas of near-future design and beta revision culture are still driving technology as surely as the PADD on Star Trek presaged the iPad.

This year’s AWE/UploadVR event showed that reality technology is emerging strongly at the enterprise level and it’s merely a matter of time before it hits consumer culture, but it’s my contention that we’re 2-4 years out unless there’s a game changer like the Oculus for AR or if the Meta or ODG get a killer app, which is entirely possible. So, as the festival’s tagline suggests, are we ready for Superpowers for the People? It seems like we’re almost there but, like Tony Stark in the beginning, we’re still learning to operate the Iron Man suit, sort of banging around the lab.

Featured: Toast McFarland

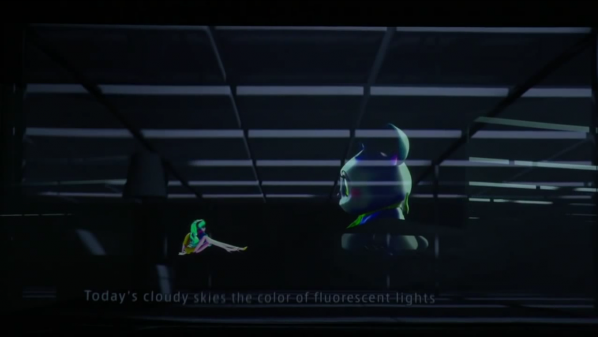

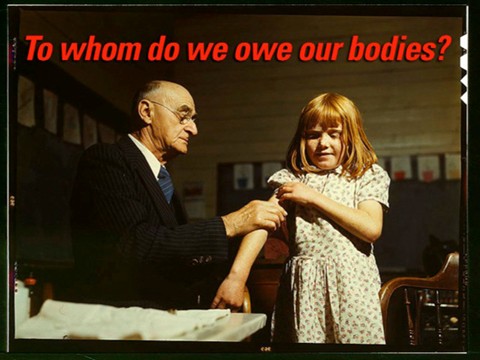

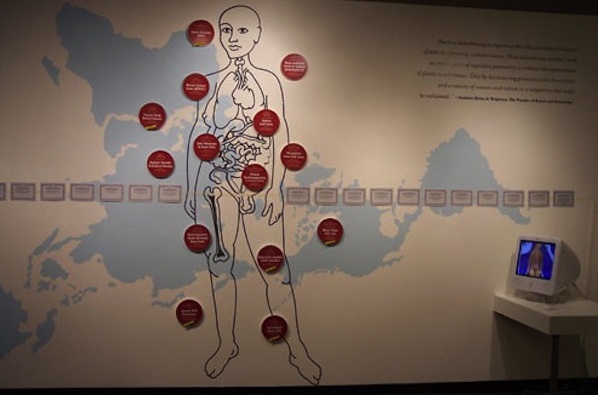

Synthetic bodies, mediated selves. What themes become relevant in a technoprogressive world – as objects proliferate, what do the inundated people talk about?

You are alone, at a computer. You talk to people but they are not around. There is no bar, no village square, no space in which you speak. There is your device and your physical presence. The social location is your body and its interface with the communicative device. What is the language for landscapes which can’t be seen, and yet which predicate subjectivity?

You express yourself. You are certain state statistics, a resume, you are a myspace profile long defunct. We require your legal name. Certain cards, from when you were born, from when you became qualified to drive, define you, make or break you. You are an ok person provided your paperwork is in order – morality is preceded by bureaucracy.

What’s the relationship between a legitimated self and that person’s body? The more modes of documentation we have the greater possibility for fictional aberration. The disparities between someone’s situated life and the records which make up their memory proliferate.

The image above by artist Toast McFarland was taken in a cartoon world. It is a selfie, a socially streamed validation of presence, but it is also a meticulous reframing of that practice. Everything is subtle, deceptively common, and yet the composition is entirely irreal. Flat colours, almost abstractly plain costuming, this is what happens when a vector world invades your computer room. It exists between personal expression and the self as actor within the surreal.

Leah Schrager‘s modelling-inspired self-portraits covered over with bright streams of paint. The model image professionalizes the act of self-representation in image form. In the profession there are industry demands – self-validation may be about confidence and friendship, where industrial success might tend towards epitomization and abstraction. Are you a good model – do you meet the sexual and aesthetic demands of the collective consumer unconscious? Schrager’s work combines a toying with such psychological implications with a background in their material underpinnings – the body in dance, the body in biological study. This combination allows for work and commentary that penetrates the relationship between the vessel you are indelibly given and the psychological relationship it develops mediated for oneself and a public.

Do you view Schrager’s images out of an interest for her or for the type of beauty she represents? Once the image is painted over, is there any interest left? Through different personas, she delivers these in a variety of web contexts, each time asking us to reconsider who we’re looking at, and who we are to look.

Screens, correspondents, professional speakers. We are happy to take your call. These two screenshots are taken from two videos by media artist Aoife Dunne. Both combine a juxtaposition of found broadcast footage, the enveloping commercial TV world, and her own crafted filming sound stages. They are installations, videos, and imagist combinations that take our question of the self directly to the media world. In the second, Dunne acts directly over top found footage, performing as doppelganger of the telemarketer in the projection. Her simultaneously comic, retro and coolly provocative aesthetic places her into an 80s infomercial dream world. She acts her own fiction, the selfie is the superlative thought experiment, and yet the proliferation of doubles buries her subjectivity in an imagined space of marketed image sheen. In the first work we only have a double, and Schrager’s biological world is fleshed out and externalized. This is what you really look like. Dunne’s own medicalized outfit says that this telecommunication is also a biological translation. For your image, we need your face, but for your face, we need organs and cells. Between the public and economic demands of the screen, and the material demands of your body, where are you?

Dafna Ganani‘s work, through a combination of images, code, social internet art and theoretical reflection, gives us an exemplar of how self-representation meets technical distortion. Her own performative presence proliferates in her work, yet always accompanied by animations, entire interactive worlds complicating any personal space. In this image, self-reflection is directly addressed – at first glance it mirrors what is represented but on closer inspection nothing of what that would look like quite match up. Where are the dragon head things located, where is she, before and after mirroring – the almost comical comparison is undermined by a disquieting sincerity. She appears intent on knowing where she is, however much the dragon doesn’t have her best interests in mind. And the right hand, reaching into the animation cloud on the left, nowhere to be seen on the right.

Dunne’s world of media culture screens is made specific and celebratory in Georges Jacotey‘s self-portraiture as Lana del Ray. An internet performance artist whose work explores media culture and self-image, the picture’s combination is both nearly seemless and parodically collaged. We all participate on some level in commercial culture, but we can never admit it. We might genuinely like aspects of it, we might hate aspects – but the popular bent of this culture means that as long as it is pleasing to a common consumer base it will gain a cultural existence. You know so much about iconic entertainers you never asked to know about. Jacotey takes on this conundrum, joins in on it, participates – what if instead of merely liking a celebrity, you seek to emulate and become them? Some people like del Ray’s albums, Jacotey’s the one who sang them. Capitalism asks that you buy, what if you take the role to sell? Human images make for great products, before we make the necessary transactions let’s make sure we know how to transform ourselves into them.

Good self-representation requires good media savvy. Before you think about your online identity simplify the process by becoming a celebrity. They’ve already figured out all the questions of the self in society – the right names, dress, mannerisms, the right look. Everything is acceptable, everything is inspiring, nothing is quite familiar.

Rafia Santana further draws out Jacotey’s comparison of the celebrity image and the selfie. Two different trajectories are taken up here – one is to deconstruct the fictions of the “real celebrity image”. The second is to fictionalize and play with one’s own portrayal. The result is layered, offering multiple points of entry for both observation and critique. If the digital image is just bits and bytes, what happens to ethnic history, to situated lives and experience? Putting herself repeatedly in her own work, Santana asks the basic question at hand – what, in re-representation, am I? And, with Jacotey, she probes the obverse of media celebrity existence and identification. If I like a celebrity, am I participating at all in their imagery or life? If so, in what way – what right to I have to their life, or in turn, what right do they have to be omnipresent in mine?

Subjectivity is the sentence, objects the fetish – be sure to glamour up.

Be sure to dress things up so you can recognize them well. Try not to mix up hair with noses, and composure with distortion. Each act of mediation further twists and reinvents our own images. You thought you knew where your lips were, what your skin looked like, but everything that goes through the machine comes out different, strange. It’s not a human, it’s a landscape. There’s an eye at the top, but you have no idea what it’s for. In the work of Sam Rolfes, the self is almost abstract, technical distortions take over any recognizable vestige of a human. Technique is everything, humanity nothing.

The self is painted, photographed, symbolized. It’s not a live image on the phone. Sometimes people in canvases try to get out. There are a few people here, all the same, that have nothing to do with one another. In Carla Gannis‘ selfie series, we return to a cartoon realism – but this time with a few added mirrors. Is the skull in the background also her? What is that a memento of?

Death in the image, life in its reproduction. You are now invisible, but we know more about what you look like than ever. Technological proliferation upends and eliminates traditional context but can never efface bodies and their identities. Indeed its societal saturation emphasizes these presences, their inevitability and all their embodied ties that digitize incompletely.

These practices work to situate the self, the body. Physiological maps are now more important than ever – they give us the image of the virtual. Mythology says we are in an immaterial age, that humans are obsolete and will be succeeded by machines. Reality says something far more disturbing – that our own materiality is the means of that obsolescence.

Featured image: By Instagram users lynellspencer and banditqueen555

I’ve been thinking about the idea of home a lot recently. I’ve been traveling over three continents for the last 6 months, living out of hostels, surfing friend’s couches, and even staying in local homes through Couchsurfing or personal connections. In terms of my home, I’ve grown comfortable with no privacy, sleeping in a room of strangers with only a tiny locked box for security. While I knew in my head the contemporary home is always shifting, I didn’t start considering the impact of that until my own housing situation became so erratic.

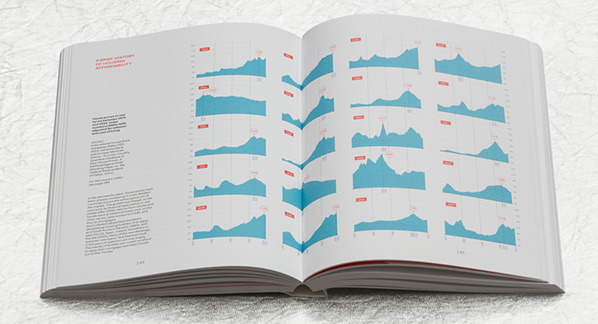

So I was excited to reflect further on the homes when the design research collaborative Space Caviar released a book of commissioned essays entitled, SQM: The Quantified Home. The essays examine how the romantic idea of the home is increasingly in tension with global market forces, zoning laws, new technologies, surveillance, war, and much more. The book was commissioned by Biennale Interieur and was part of Space Caviar’s program, “The Home Does Not Exist,” which premiered at the Biennale Interieur in Belgium in October of last year.

“Industry people today don’t actually want the home of the future. What they want is the homeowner of the future, as the kind of completely consumer-aware, Amazon-livestock guy… They don’t care what the shape of the house is, they just want the data flows in and out.” – Bruce Sterling, (pg. 236)

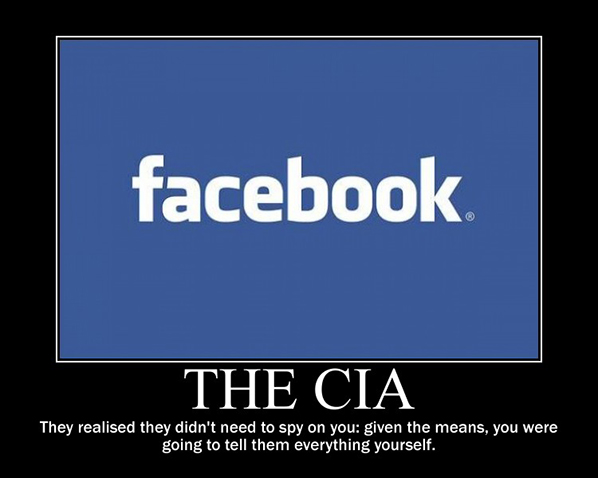

In his essay, Bruce Sterling asks us how the architecture and architects of the home will be disrupted – like the music and publishing industries were disrupted – for data optimization? As we’ve done for social media, we’re opening up our homes to private companies for the sake of security and ease. We’re putting security cameras in our children’s bedrooms and connecting our home to the cloud with devices such as Amazon Echo. How will the home as networked site look when created to produce as much advertising data as possible? How can a home look more like an Amazon warehouse?

In the networked home of the future, will we enter a Facebook-like power relationship, willingly rendering all our most private moments visible to marketers for a tax break or a free networked fridge? It sadly doesn’t sound too unlikely to me. SQM: The Quantified Home sets up a history and context to considering the realities of this kind of future home, making the clear complex data and politics already intersecting within our home.

Much of this opening up of the home is economically focused. Given the financial collapse of 2008 and subsequent austerity measures around the world, of which all but the mega-wealthy are still reeling from, we’ve been forced to use our homes as economic tools of investment as much as private spaces for family and loved ones. An investment which fewer and fewer people can afford to make. If architecture, homes, and even cities follow the trend of social media’s economic disparity – exchanging some free services for huge swaths of powerful and valuable data – it’s only going to get worse.

Selling acceptable looking cheap furniture that can barely survive its own assembly, Ikea is a perfect response to a generation that cannot afford a home. As career security grows more precarious, we’re increasingly moving cities and jobs, with Airbnb as a life raft for homeowners who can’t afford rent, and renters who can’t afford a home. The romantic ideas of “home” are collapsing all around us. As Alexandra Lange, author of Writing about Architecture: Mastering the Language of Buildings and Cities, notes, our Pinterests are filled with items we will never buy for homes we can no longer afford.

In, “The Commodification of Everything,” Dan Hill, the executive director of Futures at the UK’s Future Cities Catapult, looks at Marc Andreessen’s notion that, “software is eating the world,” and applies it to Airbnb and resident-led emergent urban interventions in Finland. While some celebrate often left-of-legal urban interventions, many of the same group cries foul when corporations like Airbnb do the same.

Hill writes, “It took Hilton a century to construct all of their hotels, brick by brick; Airbnb came along, armed only with software, and in six years created more without laying a brick.” (pg. 219) Hill asks us to further investigate how to use software in a civic way, protecting and enabling local culture and economies for the benefit of everyone. Hill writes that software “is eating the world, and it is only just booting up. Our response to that, as citizens and cities, will determine whether it does so for public good or for private gain.” (pg. 223)

So while the home is becoming a more fluid space, this predominately suits businesses or people like me because I have the freedom and privilege to move easily and earn a living wherever I have internet. Making housing more responsive to individual needs is nice advertising, but ignores larger housing markets and market forces all of us are subjected to.

Now, after reading this book and 6 months of travel with at least 6 more months to go, my idea of the home has shifted to be understood mostly in relation to family and friends. Moving through many different architecture styles, cultures, customs, and living situations have made me care less about the physical space of the home. However, this means that as the contemporary home becomes a site of surveillance, responsive, and transparentin relation to corporations and often governmental organizations, the contemporary home will place these networked spheres between us and those we most cherish.

Our most intimate settings – be it a home or an Airbnb room – now have corporations sitting right next to us. Just as we know you shouldn’t share anything you don’t want everyone to know on Facebook, in the future, we now know not to talk in front of your smart TV. The home may be the final site of privacy in modern cities yet many are actively sacrificing that privacy for a sense of security or for cool new products whose terms and conditions we never fully grasped.

Conversely, instead of placing ads between a couple cuddling on their networked bed of the future, the networked home is equally likely to put our entire social network into the bed with us in hopes of more clicks. We already see how social networks can favor clicks over meaningful connection. Joanne McNeil’s essay. “Happy Birthday,” continues a progression we’re already seeing to an always-on extreme where our birthdays are reduced to spam-like events where everyone we ever met and every object we encounter spews “Happy Birthday” ad nauseam.

This is of course a product of the advertising model of which most everything online is reliant on. Why would that change when the internet moves into your home? Indeed we already ask for this as 80% of 18 to 44 year olds check our phones first thing upon awakening. Now just turn your bed into the phone.

While networks moving into our home is cause for alarm, what was most startling to me about SQM: The Quantified Home, was the extent to which the home is already a site of many networked relationships between the city, few of which we control or are meaningfully transparent to the average homeowner. In “Postcode Demographics” Joseph Grima and Jonathan Nicholls discuss Acorn, an early program quantifying housing markets in the England. Using 60 metrics of classifications, Nicholls helped quantify neighborhoods for real-estate developers, homeowners, taxation, and more. The introduction of postal codes further quantified neighborhoods in a way likely many find helpful yet can lead to a kind of data lock-in. As these methods of quantification grow more complex, and the ramifications larger, the possibility of residents transcending their zip codes grows dimmer. We see this problem with funding of public schools in the states.

While we continue to connect to our homes and to each other in new ways, if those connections continue to benefit the Googles of the world the most, we’re in for trouble. Turning your home transparent to them and forgetting the place of the home within larger societal and civic concerns is dangerously shortsighted and will only benefit the big businesses. As Hill writes, whether these changes are to be net positive depends, “on how much we care about the idea of the city as a public good, how adept we are at absorbing and redirecting disruptive forces for civic returns.” (pg. 223)

[Trigger warnings for just about everything goes here. Please Do Not Read the following if you’re sensitive, or concerned about trigger(ing)s.]

“An uproar of voices was coming from the farmhouse. They rushed back and looked through the window again. Yes, a violent quarrel was in progress. There were shoutings, bangings on the table, sharp suspicious glances, furious denials…Twelve voices were shouting in anger, and they were all alike. No question, now, what had happened to the faces of the pigs. The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

– George Orwell, Animal Farm.

Today’s online spaces are communication minefields. When interacting in multiplayer games or social media niches, networks come drenched in reactivity bile. And although we might seem to bile-dilute, instead we intellectually saw at each other through a polite veneer. Here, civil discourse is label-trotted. Discourse bile may also erupt in balls-to-the-wall screaming matches. Such bouts involve trollbaiting, d0xxing, and Internet Rage Machine power-ups. Whatever the magnitude/form, online dialogues appear to be flooded with antagonistic commentary.

Truncated attention spans rage-burst. Such anger pockets are far from static: fuelled by such shameblood, the righteous degrade. We humiliate in order to inflate. We confront-tar and belittle-feather. The [s]urge for relevancy is sycophantically baked. We mobilize to unearth, to finger-point: we present affectivity as fact. Hate groups spread across factions, divide-blurring.

The search for sodalities is constant. Nuances are fudged. Contexts are ignored. Catharsis mutates through a checklist that reduces, confines, and truncates. We are force-fed trauma anecdotes as reality fulcrums. Baggage is exposed in painful lumps. We are not consideration-encouraged: we are expectation-drilled. We must agree. Must acquiesce. Must uncritically support. Anything else denunciation-equates.

Public shaming is the norm. We bully. We armchair-critique. Bipartisan voices lynchmob-morph, all-indignation-like. Roughshodders censor and context erase. Power drugs the inflamed and injects the underdog[s] with sudden shifting surges. Reference frames are smashed, then reiterated repeatedly till they become a thing of horror, of replication thrown from “side a” to hit “side b”. Such targets are then mirror-captured and magnified. Empathy is to be derided as weakness. Barbs are flung at all who seek to ponder “isms” or reclaim them. We must not listen in order to comprehend, to understand: we must shout.

We word weaponise [“…getting all soul-rapey on SJWs”/”…gut-cutting misogynistic neckbeards“/ “You are either with us or against us”]. Gator-screams and “die-cis-scum“-roars rule the day. We obliterate and issue-compress. We communication strangle. Equality is attainable through force. Aggression trumps assertion. Sarcasm blights compassion. Rudeness rewrites decency.

SUCH TERRIBLE WHITEWASHING SEALIONS

Power-grabs blind the sensitive. To destroy/troll/shame/swamp/embarrass/belittle/d0xx is to “win”. Sense of perspectives lose while extremisms gain. Dialogue is gamed: the loudest voices squash and rip, tear and silence. Threats echo the noose. Implications drive output. The end-goal is attention, ratification, dis[e]ruption: a pendulum power swing designed to flatten and redress. We obscure and vilify. We replicate exclusion ethics. We buck-and-doe-pass.

Online purging results in strange social crevices. Encouraged to instantaneously blurb our stream-of-tweeted-consciousness, we are off the chain. We spontaneity-bark and bleat [at] everything and all. Cohesion shatters. We no longer rely on institutions to dictate, to guide, to sanction. Moral Absolutists war-trawl Moral Relativists. The Arab Spring has turned us inside out. Unsure, we turn on each other. We emoji expose and deride. We [slut]shame and attack: all within banners born from psychologies spouting the benchmark worth of individualisation. Selfies become our egocentric standard.

We once attempted to codify, to restrain. But now, all gloves are off. We scrabble and lunge. We showcase-badge based on our version of “the categorical truth”. We bang and bleed against these corners, these intersections of emotion and intellect. Of private and public. Of control and openness. There is no room for reflection, for consideration, for clarity.

We refuse anything that calms. Online spaces are for battling. Playfulness and cohesion are sacrificed. Righteous mobs insult fling: they ratify rather than reappropriate. Alternates gleefully spout these insults as proof, stamp-ammo-ing all the while. There are, however, those who stay and observe. We await the wind-down. We desire an eventual dissolve: a fundamental shift. They can’t last, these discourse patterns. We wait for rage to course-run, for rage-fatigue. We await the next mediation bump.

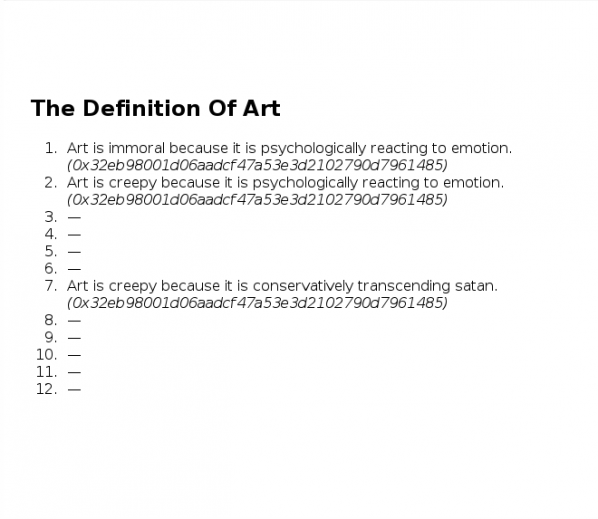

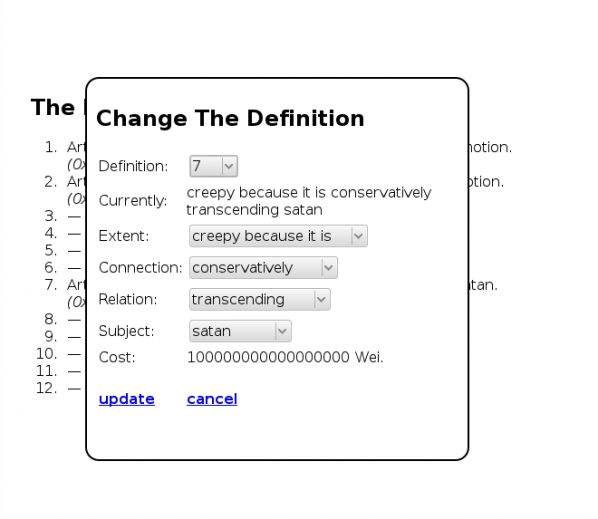

Art, to misparaphrase Jeff Koons, reflects the ego of its audience. It flatters their ideological investments and symbolically resolves their contradictions. Literature’s readers and art’s viewers change over time, bringing different ways of reading and seeing to bear. This relationship is not static or one-way. The ideal audience member addressed by art at any given moment is as much produced by art as a producer of it. Those works that find lasting audiences influence other works and enter the canon. But as audiences change the way that the canon is constructed changes. And vice versa.

“The Digital Humanities” is the contemporary rebranding of humanities computing. Humanities for the age of Google rather than the East India Company.

Its currency is the statistical analysis of texts, images and other cultural resources individually or in aggregate (through “distant reading” and “cultural analytics“).

In the Digital Humanities, texts and images are read and viewed using computer algorithms. They are “read” and “viewed” by algorithms, which then act on what they perceive. Often in great number, thousands or millions of images or pages of text at a time, many more than a human being can consider at once.

The limitations of these approaches are obvious, but they provide a refreshing formal view of art that can support or challenge the imaginary lifeworld of Theory. They are also more realistic as a contemporary basis for the training of the administrative class, which was a historical social function of the humanities.

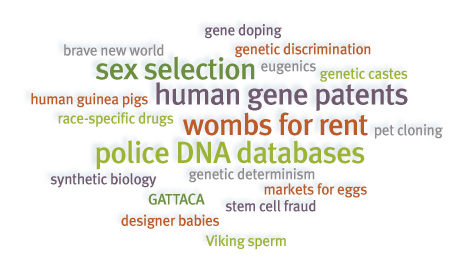

Digital Humanities algorithms are designed to find and report particular features of texts and images that are of interest to their operators. The most repeated words and names, the locations and valences of subjects, topics and faces and colours. They produce quantitative statistics regarding works as a whole or about populations of works rather than qualitiative reflection on the context of a work. Whether producing a numeric rating or score, or arranging words or images in clouds, the algorithms have the first and most complete view of the cultural works in any given Digital Humanities project.

This means that algorithms are the paradigmatic audience of art in the Digital Humanities.

Imagine an art that reflects their ego, or at least that addresses them directly.

Appealing to their attention directly is a form of creativity related to Search Engine Optimization (SEO) or spam generation. This could be done using randomly generated nonsense words and images for many algorithms, but as with SEO and spam ultimately we want to reach their human users or customers. And many algorithms expect words from specific lists or real-world locations, or images with particular formal properties.

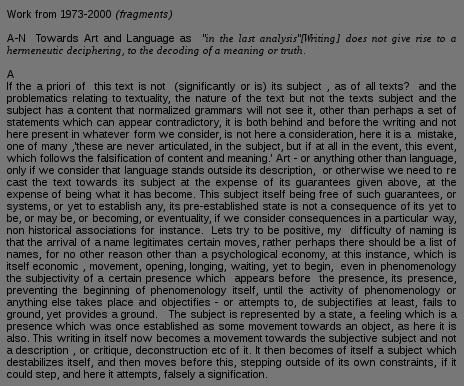

A satirical Markov Chain-generated text.

The commonest historical way of generating new texts and images from old is the Markov Chain, a simple statistical model of an existing work. Their output becomes nonsensical over time but this is not an issue in texts intended to be read by algorithms – they are not looking for global sense in the way that human readers are. The unpredictable output of such methods is however an issue as we are trying to structure new works to appeal to algorithms rather than superficially resemble old works as evaluated by a human reader.

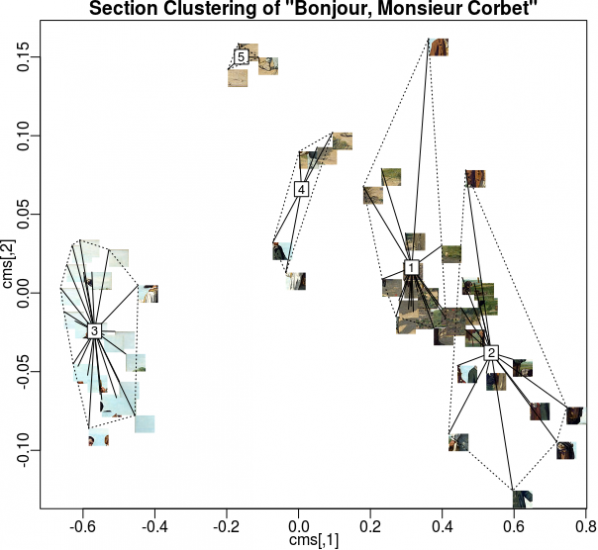

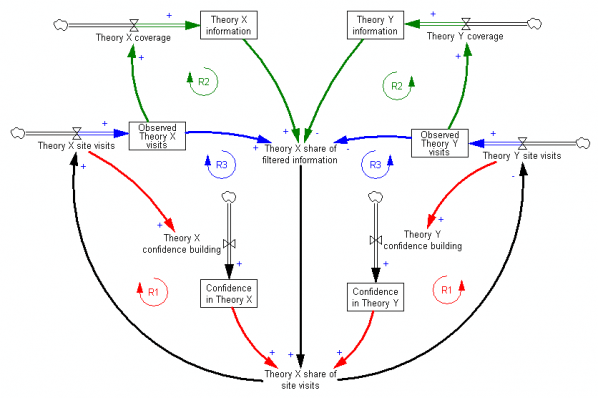

The two kinds of analysis commonly performed on cultural works in the Digital Humanities require different statistical approaches. Single-work analyses include word counts, entropy measures and other measures that can be performed without reference to a corpus. Corpus analysis requires many works for comparison and includes methods such as tf-idf, k-means clustering, topic modeling and finding property ranges or averages.

ugly despairs racist data lunatic digital computing digital digital humanities digital victim furious horrific research text racism loathe computing text humanities betrayed digital text humanities whitewash computing computing cheaters brainwashing digital research university university research falsifypo pseudoscience research university worry research data technology computing humanities technology data technology research university research university computing greenwasher cruel computing university data disastrous research digital guilt technology university sinful loss victimized computing humiliated humanities university research ranter text text technology digital computing despair text technology data irritate humanities text data technology university heartbreaking digital humanities text chastising text hysteria text digital research destructive technology data anger technology murderous data computing idiotic humanities terror destroys data withdrawal liars university technology betrays loathed despondent data humanities

A text that will apear critical of the Digital Humanities to an algorithm,

created using negative AFINN words & words from Wikipedia’s “Digital Humanities” article

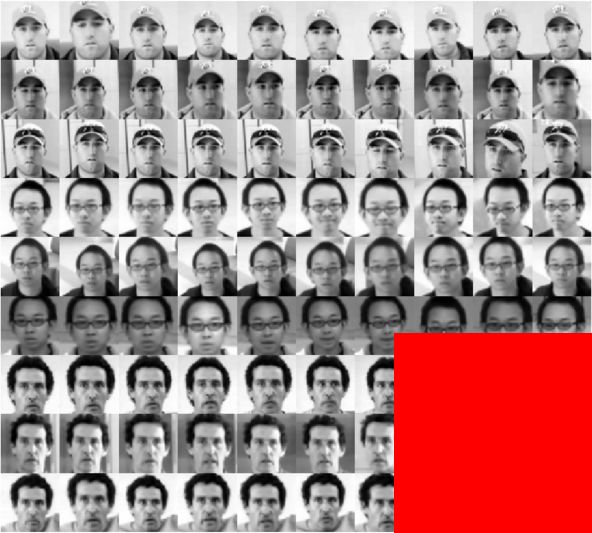

We can use our knowledge of these algorithms and of common training datasets such as the word valence list AFINN and the Yale Face Database, along with existing corpuses such as flickr, Wikipedia or Project Gutenberg, to create individual works and series of works packed with features for them to detect.

web isbn hurrah superb breathtaking hurrah outstanding superb breathtaking isbn breathtaking isbn breathtaking thrilled web internet hurrah media web internet outstanding thrilled hurrah web thrilled media thrilled superb breathtaking art breathtaking media superb hurrah superb net artists outstanding internet outstanding net superb thrilled thrilled art hurrah based outstanding superb net internet artists web art art artists internet breathtaking based net hurrah outstanding thrilled superb hurrah media based outstanding media art artists outstanding isbn based net based thrilled artists isbn breathtaking

A text that will appear supportive of Internet art to an algorithm,

made using positive AFINN words and words from Wikipedia’s “Internet Art” article.

When producing textual works for individual analysis, sentiment scores can be manufactured for terms associated with the works being read. Topics can be created by placing those terms in close proximity. Sentence lengths can be padded with stopwords that will not affect other analysis as they will be removed before it is performed. Named entities and geolocations can be associated, given sentiment scores, or made the subjects of topics. We can structure texts to be read by algorithms, not human beings, and cause those algorithms to perceive the results to be better than any masterpiece currently in the canon.

When producing textual works to be used in corpus analysis individual or large volumes of “poisoning” works can be used to skew the results of analysis of the body of work as a whole. The popular tf-idf algorithm relates properties of individual texts to properties of the group of texts being analysed. Changes in one text, or the addition of a new text, will skew this. Constructing a text to affect the tf-idf scores of the works in a corpus can change the words that are emphasized in each text.

The literature that these methods will produce will resemble the output of Exquisite Code, or the Kathy-Acker-uploaded-by-Bryce-Lynch remix aesthetic of Orphan Drift’s novel “Cyberpositive“. Manual intervention in and modification of the generated texts can structure them for a more human aesthetic, concrete- or code-poetry-style, or add content for human readers to be drawn to as a result of the texts being flagged by algorithms, as with email spam.

When producing images for individual analysis or analysis within a small corpus (at the scale of a show, series, or movement), arranging blocks of colour, noise, scattered dots or faces in a grid will play into algorithms that look for features or that divide images into sectors (top left, bottom right, etc.) to analyse and compare. If a human being will be analysing the results, this can be used to draw their attention to information or messages contained in the image or a sequence of images.

When producing image works for corpus analysis we can produce poisioning works with, for example, many faces or other features, high amounts of entropy, or that are very high contrast. These will affect the ranking of other works within the corpus and the properties of the corpus as a whole. If we wish to communicate with the human operators of algorithms then we can attach visual or verbal messages to peak shift works, or even in groups of works (think photo mosaics or photobombing).

The images that these methods will produce will look like extreme forms of net and glitch art, with features that look random or overemphasized to human eyes. Like the NASA ST5 spacecraft antenna, their aesthetic will be the result of algorithmic rather than human desire. Machine learning and vision algorithms contain hidden and unintended preferences, like the supernormal stimulus of abstract “superbeaks” that gull chicks will peck at even more excitedly than at those of their actual parents.

Such image and texts can be crafted by human beings, either directed at Digital Humanities methods to the exclusion of other stylistic concerns or optimised for them after the fact. Or it can be generated by software written for the purpose, taking human creativity out of the level of features of individual works.

Despite their profile in current academic debates the Digital Humanities are not the only, or even the leading, users of algorithms to analyse work in this way. Corporate analysis of media for marketing and filtering uses similar methods. So does state surveillance.