Join us in Edinburgh at the first DAOWO ‘Blockchain & Art Knowledge Sharing Summit’ of 2019

DAOWO (Distributed Autonomous Organisations With Others) Summit UK facilitates cross-sector engagement with leading researchers and key artworld actors to discuss the current state of play and opportunities available for working with blockchain technologies in the arts. Whilst bitcoin continues to be the overarching manifestation of blockchain technology in the public eye, artists and designers have been using the technology to explore new representations of social and cultural economies, and to redesign the art world as we see it today.

This summit will focus on potential impacts, technical affordances and opportunities for developing new blockchain technologies for fairer, more dynamic and connected cultural ecologies and economies.

Programme

Although the term ‘blockchain’ has trickled downstream into the public domain, the principles behind the technology remain mysterious to many. Embodied within physical assemblages or social interventions that mine, hash and seal the evidence of human practices, creatives have provided important ‘coordinates’ in the form of artworks that help us to unpick the implications of the technology and the extent to which it re-configures power structures.

Hosted by Prof Chris Speed and Mark Daniels with panellists:

Pip Thornton – The Value of Words in an Age of Linguistic Capitalism

Bettina Nissen & Ailie Rutherford – Designing feminist cryptocurrency for Govanhill

Evan Morgan – GeoPact

Jonathan Rankin – OxChain, Pizza Block

Larissa Pschetz – Karma Kettles

Contributors include:

Ruth Catlow, Furtherfield and DECAL

Mark Daniels, New Media Scotland

Clive Gillman, Creative Scotland

Marianne Magnin, Arteïa

Prof Chris Speed, Design Informatics, University of Edinburgh

Ben Vickers, Serpentine Galleries

Through two UK summits, the DAOWO programme is forging a transnational network of arts and blockchain cooperation between cross-sector stakeholders, ensuring new ecologies for the arts can emerge and thrive.

DAOWO Summit UK is a DECAL initiative – co-produced by Furtherfield and Serpentine Galleries in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut London. This event is realised in partnership with the Department of Design Informatics at the University of Edinburgh and New Media Scotland.

OxChain is a major EPSRC research project which explores how Blockchain technologies can be used to reshape value in the context of international development and the work of Oxfam, involving the Universities of Edinburgh, Northumbria and Lancaster.

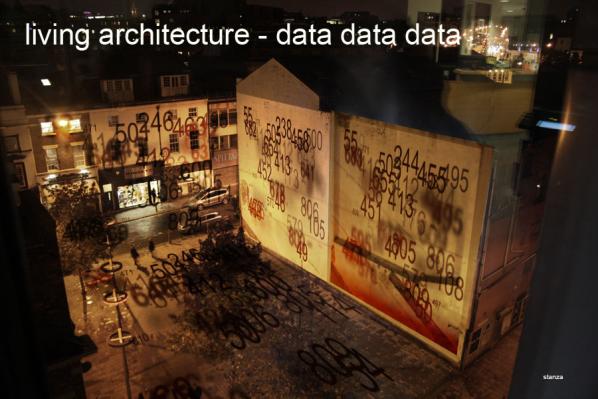

Stanza is an internationally recognised artist who has been exhibiting worldwide since 1984. He has won so many prizes you’d have trouble fitting them all on one mantlepiece. He has exhibited over fifty exhibitions globally and is an expert in arts technology, CCTV, online networks, touch screens, environmental sensors, and interaction. His artworks examine artistic and technical perspectives, within the contexts of architecture, data spaces and online environments.

Recurring themes throughout his career include the urban landscape, surveillance culture, privacy and alienation in the city. Stanza is interested in the patterns we leave behind, and real time networked events, that are usually re-imagined and sourced for information. He uses multiple new technologies so to create distances between real time, multi point perspectives that emphasis a new visual space. The purpose of this is to communicate feelings and emotions that we encounter daily which impact on our lives and which are outside our control.

Much of his work has centered on the idea of the city as a display system and various projects have been made using live data, the use of live data in architectural space, and how it can be made into meaningful representations. See Publicity, Robotica, Sensity, as well as a whole series of work manipulating real time CCTV data to making artworks with them: See, Velocity, Authenticity, Urban Generation. These works reform the data, work with the idea of bringing data from outside into the inside, and then present it back out again in open ended systems where the public is often engaged in or directly embedded in the artwork. Interactive and visually appealing, his style also maintains the substantive power through multi-facetted content.

Marc Garrett: Could you tell us who has inspired you the most in your work and why?

Stanza: I don’t really get inspiration from the “who” question, I prefer the “what” and “why” questions. As a professional artist I look at loads of art so to understand what art is and can be, and it’s always an ever changing and fluid response. I also spend a lot of time ignoring stuff and material; (focused ignoring) because it has become harder and harder to see though the fog; the noise of it all. Maybe it’s better to think of a working model for inspiration, Andy Warhol had one. Just make the work. That’s what I do. I am not a part time artist in academia or an artist with another job, I’ve done this for the last thirty years, inspired by and in response to the world around me.

This dogmatic commitment to my work comes from my believes that the system you have to trust and invest in yourself. Inspiration, quite literally is everything all around you all at once, all at the same time, moment by moment. This is what inspires my work and it influences the creation of real time information flows, and works in parallel realities. It allows me to stand back at a distance and work with complex data sets while at the same time making meaning from them. Forming data into a shape, because this confluence might inspire a repositioning of thought and values while at the same time unlocking a hidden meaning to enable the viewer to feel and experience something new or to do something creative with the results.

MG: How have they influenced your own practice and could you share with us some examples?

S: There’s a saying be careful what you wish for. If one reverses this then it could be wish for what you want and need. Influence is problematic because it’s both negative and positive. The idea of influence seems causal, but my own practise isn’t based on influence but in research into certain themes. This enables me to get into both sides of particular questions or debate, so to frame the work I make. Works like these have been inspired by this focus…

The Singing Trees, focus in the invisible things and the environment http://stanza.co.uk/tree/index.html

MG: How different is your work from your influences and what are the reasons for this?

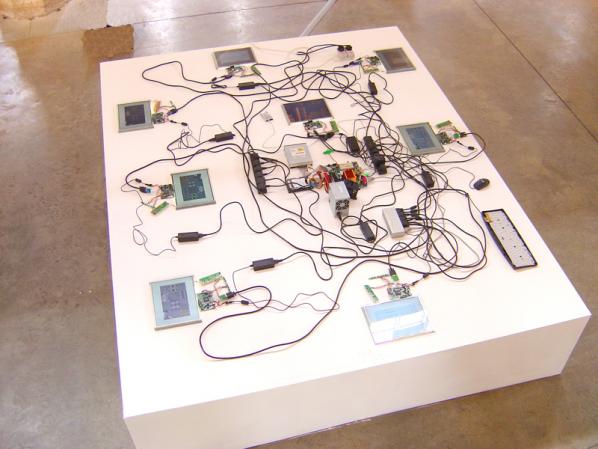

S: I have been researching smart cites, urbanisn, and have collected ‘big data’ since 2004. I have been building my own wireless sensor network. This eventually manifested itself in an artwork called Capacities in 2010 which then influenced all the others in the series until it now has this form.

Capacities: Life In The Emergent City, captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork

http://stanza.co.uk/capacities/index.html

Which led to…

The Nemesis Machine- From Metropolis to Megalopolis to Ecumenopolis.

“A Mini, Mechanical Metropolis Runs On Real-Time Urban Data. The artwork captures the changes over time in the environment (city) and represents the changing life and complexity of space as an emergent artwork. The artwork explores new ways of thinking about life, emergence and interaction within public space. The project uses environmental monitoring technologies and security based technologies, to question audiences’ experiences of real time events and create visualizations of life as it unfolds. The installation goes beyond simple single user interaction to monitor and survey in real time the whole city and entirely represent the complexities of the real time city as a shifting morphing complex system.

The data and their interactions – that is, the events occurring in the environment that surrounds and envelops the installation – are translated into the force that brings the electronic city to life by causing movement and change – that is, new events and actions – to occur. In this way the city performs itself in real time through its physical avatar or electronic double: The city performs itself through an-other city. Cause and effect become apparent in a discreet, intuitive manner, when certain events that occur in the real city cause certain other events to occur in its completely different, but seamlessly incorporated, double. The avatar city is not only controlled by the real city in terms of its function and operation, but also utterly dependent upon it for its existence.”

MG: Is there something you’d like to change in the art world, or in fields of art, technology and social change; if so, what would it be?

S: It’s the museum I would like to change or engage with. It seems that anything and everything will end up in the museum. We have become the museum. We are the sum of our collections catalogs and archives. Since the current trend is for public engagement we will see a mix of these new technologies aiding and abetting this and various dialogues.

Therefore these questions need to be raised more vocally. How do visitors interact with each other and artworks? How do visitors behave in public space and what patterns or communities do they form. Can these outputs reshape our experience of public space and the art?

So, new immersive technologies could be used to investigate how visitors interact with art works, with each other and what impact their experiences have in forming new user interactions within public space. This space could be made more social and lead to new real time artworks based on visitor interaction and new visualizations of the gallery space based on gathered data.

Artists used to occupy specific issues but now there aren’t many topics artists haven’t engaged in or reached out to. The issues that will resonate will be the ones closest to the issue of the day…. and, they will be economics, the environment and migration. Because of this I would like to less focus on public engagement spectacle or entertainment and more on the quality and public engagement rooted in intellectual rigour.

Technology affords new ways of working with audiences and curators as participants in artworks. The concept of the exhibition as an active site for experimentation and collaboration between curators, artists and audiences prefigures a general cultural movement towards the centrality of experience and away from the reification of the object.

However, how audience activities and movements can be used as the subject of new artwork as well as modify engagement with existing collections is a cultural and technological challenge.

SeePublic Domain: You Are My Property, My Data, My Art, My Love.

The Public Domain Series involves using live CCTV systems that are already installed then using these cameras to enhance gallery space and the audiences experience of the gallery. http://stanza.co.uk/public_domain_outside/index.html

Visitors to a Gallery – referential self, embedded. Stanza uses a live CCTV system inside an art gallery to create a responsive mediated architecture. Anyone in any of the galleries and all spaces in the building can appear inside the artwork at any time.

http://stanza.co.uk/cctv_web/index.html

The social challenge within urban space is one I like to play with. In The Binary Graffiti Club, is a project I set up to try and work in this area. The Binary Graffiti Club are invited members of the public at each location for each event; they are given the hoodie to keep as thanks for their participation and contribution. The Binary Graffiti Club set off across the city and create artworks.

http://stanza.co.uk/binary_club/index.html

“Youths dressed in black hoodies swarmed the historic city streets of Lincoln during Frequency Festival 2013, their backs emblazoned with bold white digits, the zeros and ones. Their ominous presence was marked with a series of binary code graff-tags on official buildings throughout the city; messages of insurrection for a digital cult now active among us or analogue reminders of the digital soup of signals we wade through on a daily basis? There’s an engaging playfulness and an aesthetic pleasure to Stanza’s work that pays rewards on deeper investigation. His urban interventions remind us of the invisible occupation of the cyberspace around us and encourages us to ask whose hand manipulates these systems of control.” Barry Hale, Festival Co-Director of Frequency Festival 2013: Stanza: Timescapes/Binary Graffiti Club.

MG: Describe a real-life situation that inspired you and then describe a current idea or art work that has inspired you?

The invention of the toothpaste tube caused a revolution in painting.

The greatest discovery of the age was that the world is full of atoms.

Doing many small things instead one on big thing.

We seam to victimise out children we give them ASBO’S and anti social behaviour orders. For a while I wanted one. They actually give you a certificate like rockers, mods punks etc. The hoodie is a symbol of youth culture as well as being anti social. My new artwork the Reader and the idea of reading books and being anti-social led to this project.

The Reader is a large six foot sculpture of the artist Stanza wearing a hoodie reading a book. The artwork is a metaphor for the engagement of reading in the digital age. The sculpture acts as a focal point for community and public engagement and has taken over one year to make and design; it has been commissioned to act as a focal point for the identity of the library. The reader reads all the books published since 1953 inside a data body sculpture. http://stanza.co.uk/TheReader_web/

MG: What’s the best piece of advice you can give to anyone thinking of starting up in the fields of art, technology and or social change?

S: Make work, make more work, and remember nothing lasts forever except true love.

Re: Art, Study it

Re: Technology. Learn it

Re: Social change . Be part of it.

MG: Finally, could you recommend any reading materials or exhibitions past or present that you think would be great for the readers to view, and if so why?

Yes the Books…

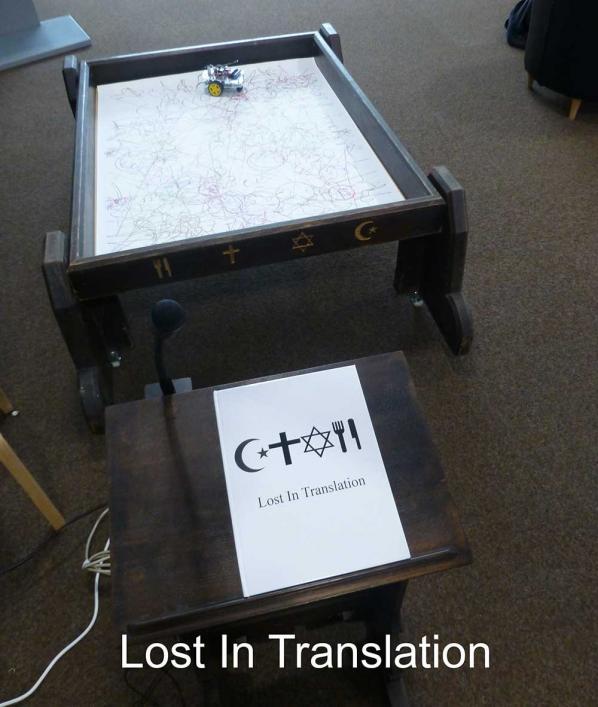

The Bible The Quran And The Torah.

Because…they are the most influential books ever written and have guided the lives of billions so it’s a good idea to have had a read… at least “view” them.

See…

Lost in Translation. This custom made robot responds to a series of texts and makes drawings unique to each reader. The work questions not only the meaning and interpretation of text but just who controls our understanding of the outputs and indeed what is Lost In Translation. This is a very playful user friendly work and actively engages the audience not only to think about the text but the meaning of how automation and networked technology is changing the control of understanding. http://stanza.co.uk/lost_in_translation/

Thank you…

Drake Music launches a making day to inspire the creation of more accessible musical instruments.

On Sunday 21 April Drake Music will run a hackday to create and share new instruments that break down disabling barriers to music making. Run in partnership with Furtherfield and Music Hackspace, makers will have the opportunity to work towards one of two prizes for the most innovative work.

Hacking To Make Music Accessible Day is part of Drake Music’s new R&D programme, which aims to:

As of January 2013, there are only 6 widely available solutions for accessible music making. In contrast an orchestra is made up of at least 19 instrument types; rock and pop frequently use 4 or more types; and the instruments used in world, electronic, jazz and folk music add up to a rich and diverse pallet of choice for most aspiring musicians. This disparity needs to be bridged, in particular with the development of more expressive musical instruments for those facing barriers to music making.

Hacking To Make Music Accessible is developed with and supported by Music Hackspace and Furtherfield. This event is also a precursor to a series of projects and initiatives which will be hosted at the WeShare Lab later this year.

“I have been bowled over by the enthusiasm and seriousness of the hacking community when faced with the question of how we can create and develop new tools to make music making accessible. This event is the first of many, and allows us to collaborate with the widest range of talent in creating the most innovative tools for a sector that desperately needs them. “ – Gawain Hewitt

For further information please contact Gawain Hewitt, Drake Music Associate Musician and Associate National Manager – Research and Development.

Drake Music breaks down disabling barriers to music through innovative approaches to making, learning and teaching music. Now in its 25th year, Drake Music continues to play a pioneering role in the development and imaginative use of Assistive Music Technology (AMT) to make music accessible. Drake Music is the only organisation in England specialising in the use of AMT to break down (physical/societal) barriers to participation.

Our focus is on nurturing creativity through exploring music and technology in imaginative ways. We put quality music making at the heart of everything we do, connecting disabled and non-disabled people locally, nationally and internationally. Drake Music is an Arts Council NPO.

The London Music Hackspace originated as a subgroup of the London Hackspace as a place to share thoughts, knowledge, technologies, processes and aesthetics on music and audio. We foster innovation by gathering skilled professionals and facilitating exchanges between disciplines, from software development to music installations and production. The Music Hackspace organises weekly events, including presentations and talks by artists and musicians, workshops, performances and unexpected collaborations. Music Hackspace are member of London Hackspace.

Drake Music and Furtherfield have come together to create WeShare, a new initiative building on the combined creative assets, specialisms and strengths of both our organisations. In a series of projects in the first phase of WeShare, supported by an organisational development grant from Arts Council England, we tested and piloted new ways of working and collaborating through projects such as Pecha Kucha Beta and Deconstructing Pecha Kucha. This year will see the launch of the WeShare Lab, which will support and host events similar to Hacking to Make Music Accessible.

WeShare has emerged from three years of successful partnership-working between Drake Music and Furtherfield who share a critical and creative engagement with art, music and technology with a focus on participation and collaboration. It aims to amplify the existing quality, reach and value of our organisations’ work, finding new ways to share knowledge, ideas, resources and opportunities; creating new ways of producing and sustaining socially engaged art and culture.

Furtherfield Gallery

McKenzie Pavilion, Finsbury Park

London N4 2NQ

T: +44 (0)20 8802 2827

E: info@furtherfield.org

Furtherfield Gallery is supported by Haringey Council and Arts Council England

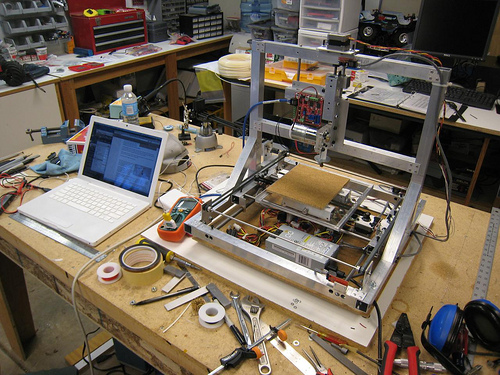

Featured image: London Hackspace http://wiki.london.hackspace.org.uk/view/London_Hackspace

…the machine is always social before it is technical.

(Gilles Deleuze)

Though the term ‘lab’ conjures the image of a fairly sanitised environment optimised for scientific experiments and populated by people in white coats, media labs – centres for creative experimentation – are quite different. At their most basic, they are spaces – mostly physical but sometimes also virtual – for sharing technological resources like computers, software and even perhaps highly expensive 3D printers; offering training; and supporting the types of collaborative research that do not easily reside elsewhere. In the early-to-mid-1990s, partly propelled by the exciting possibilities of the internet and associated web browser technologies, groups began to coalesce, bent on developing access to the inherent potential of collective creativity. With the exuberant new dot.com businesses fuelling a ‘creative economy’, the Californian ‘cybercafé’ (surf the internet and slurp the coffee) was emulated in urban centres around the UK and in some cases artists were heavily involved. They saw the internet’s myriad ways of changing the way we make, think about and share art – not to mention its capacity for social empowerment – and wanted to harness these qualities quickly and effectively. With many practitioners coming from the spaces, practices and communities forged by the independent film and video movement, the phenomenon of the UK media lab was born. However, despite the importance of these spaces as the hybrid homes of the then emergent and now embedded creative activities that characterise today’s rich field of digital and media practices, their history and contribution to current lab environments has been little discussed outside a niche arena.

Early Media Labs

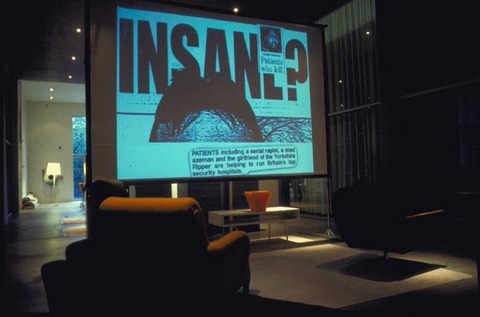

Two of the earliest UK media labs were Artec and Backspace (aka Bakspc), both based in London. Artec, which was established in 1990, was initially funded by Islington Council and ESF (the European Social Fund), but soon won additional support from Arts Council England. Conceived by Frank Boyd and Derek Richards, its focus from the outset was to deploy technology for social empowerment and, early on, it provided valuable professional training to the long-term unemployed. In this sense, it did not operate from within an arts context proper, but combined art and technology in the name of social integration. Creative projects were led by Graham Harwood, whose own artistic practice and his collective Mongrel were formed through associations at Artec.

Harwood and Mongrel’s practice is known widely for scrutinising social, political and cultural divisions through a framework of technology. A notable piece from this period was Rehearsal of Memory (1995), which took the collective experiences of staff and patients at Ashworth high security mental hospital, near Liverpool, and presented them as a unified and anonymous computer-based group portrait. Now available as a CD-ROM, the work strongly undermines the assumptions we make about mental health, blurring the line between those branded ‘normal’ or not. It is an excellent example of the way artists and media labs habitually combine creative activities with technology to give people a renewed agency. Around 1995, Peter Ride was brought on board to curate a stream of activity called Channel, which lead to further powerful artworks including Ubiquity (1997) by David Bickerstaff and Susan Collins’ In Conversation (1997).

Without regular public funding, Backspace started out as an independent self-organised cybercafé. Initiated by James Stevens as a ‘soft space’ adjunct to his commercial web design business, Obsolete, it had a physical studio and lounge on Clink Street. People could drop in and use the web access and computer terminals in exchange for a nominal membership fee and commitment to maintain the space. What is notable about the Backspace model is how it attempted to foster a co-operatively managed resource. It exemplified a preoccupation amongst internet culture devotees with autonomy and new forms of governance, and struggled with all the contradictions of such ideals alongside the fact of its commercial parent entity. Obsolete shared its (at that time) capacious bandwidth. This gave people web hosting and streaming capabilities that would otherwise have been prohibitively expensive; allowed for the hosting of many artistic projects produced within the space itself; and facilitated many early streaming experiments with link-ups between other European media labs including as E-lab in Riga, Lativa and Ljudmila in Llubljana, Slovenia. Early attendees and co-facilitators of Backspace now list some central figures of the Digital and New Media art fields including: Matt Fuller, Simon Pope, Armin Medosch, Heath Bunting, Ruth Catlow, Pete Gomes, Manu Luksch and Thomson and Craighead – even Turner Prize winner Mark Lecky was a regular for a while.

Globally distributed discussion networks provided a discursive layer for these media labs, with early mailing lists such as Nettime, Rhizome and Syndicate forging international connections around technology, art and politics. Likewise, Mute (at first a newspaper, then a glossy magazine, now a web journal) provided regular critical commentary on burgeoning digital culture.

Foundationally different, Artec and Backspace were united by a belief in the importance of access to tools and training within a social context. In slightly differing ways, they put creative experimentation and social concerns at the centre of the agenda via technology. This was to become an important organisational strategy for this sector. Though both spaces have since closed, Stevens continues to build social and technological infrastructure as Deckspace, at Borough Hall, Greenwich. Without a physical space, Frank Boyd has evolved his media lab system into an industry-orientated programme called Crossover, which assembles creative professionals to workshop cross-platform ‘experiences’ from a variety of creative arenas including film TV and the computer games industry. Crossover is one of many peripatetic media lab models that privilege collaborative creative processes, although it is more goal-orientated than most as participants often pitch to a panel of industry commissioners.

Process over Product

With less of an eye on industry and an abiding interest in the creative process itself, PVA MediaLab was formed in 1997 by artists Simon Poulter and Julie Penfold. In its first incarnation, it took up residence at Dartington College of the Arts, with funding from South West Arts. While there, artists were offered a well-equipped space in which to experiment with technology and develop ideas. In fact it is this developmental freedom that forms another core operational component of the media lab. Rather than asking artists to arrive with pre-formulated projects, or expecting them to see a piece through from start to finish, media labs have consistently placed value on self-determined exploration. PVA helps artists to manufacture methodologies rather than final artworks, fully designed products or content packages. They have also led the way in assisting other media labs to produce a similar system, through their Labculture programme. Highly itinerant, the Labculture model adjusts itself to host organisations, like Vivid, in Birmingham, so they can learn how to set and achieve goals while building the sorts of lasting partnerships that will sustain future activity.

This shared or Open Source way of working integral to media lab culture is also exemplified by GYOML (Grow Your Own Media Lab). A collaborative project between media labs Folly, Access Space and the Polytechnic, GYOML was designed to help generate more media lab initiatives. It has included: ‘GYOML in a Kitchen’, a sound recording and editing workshop by Steve Symons (Lancaster); ‘GYOML in a Van’, which staged an introductory workshop in media-lab culture for community group leaders (Lancaster); a game-centred ‘GYOML for teenagers’ (Rochdale); and ‘GYOML at the Canteen’, catering to film-makers and professional artists with an interest in open source (Barrow-in-Furness). Legacies of this project include the Digital Artists Handbook, an impressive guide to Open Source tools and techniques and ‘Grow Your Own Media Lab (the graphic novel)’, a set of inspiring case studies. Folly continue to work very much in this manner, forming essential infrastructural relationships as and where needed and guiding others through the adoption of free software.

Another example of this attention to operation and openess comes from GIST Lab, in Sheffield, which energises community-based projects through a space that hosts meetings and workshops. Even without a dedicated tech suite, their knowledge-exchange is a short-cut to all manner of original cross-over work, and they have supported yet another project that literally and metaphorically recreates aspects of the media lab model. 3D printing (or rapid prototyping) is increasingly popular in producing anything from car parts to jewellery, by layering materials like plastic into finished three-dimensional objects. RepRap, however, is able to print the spare parts it needs to be built while it is still itself under construction. Just like media labs, this self-replicating 3D Printer is all about sharing access to a successful system.

If media labs are not driven by material production, neither are they all about technology. Arising from the work of the art group, Redundant Technology Initiative, Access Space in Sheffield established its media lab through the use of free and recycled technology and learning. Given our cultural predisposition for wanting the latest, fastest equipment and our reprehensible dumping of perfectly serviceable technology, abundant hardware is sourced from all manner of locations. The latest Free and Open Source software is installed on the hardware where expensive proprietary software once lay and the media lab space, complete with this equipment, is opened to the public five days a week. The one proviso placed on this access – continuing the recycling theme – is that once a media lab participant has learnt how to do something, they should pass this knowledge on. As evidence of the success of this system Access Space boasts impressive outreach capacity: more than a thousand regular visitors, of which only about thirty-five percent are university educated, and over half are unemployed, and they habitually work with people experiencing disabilities, learning disorders, poor health, homelessness or other measures of exclusion.

One of the projects that clearly shows what they do is Zero Dollar Laptop, a collaboration with the Furtherfield organisation and community. Through a series of workshops, homeless participants are given the ability to use and maintain a free laptop complete with free software in self-led creative projects. It is this model of learning through self-directed creativity that arises again and again in media labs because it provides demonstrable results in helping people acquire and retain the skills they need. Without ‘bells and whistles’ new technology, Access Space emphasise the importance of ideas over technology and demystify all manner of computer-based skills. SPACE Studio’s MediaLab is also an excellent example of a lab working at a range of levels to offer beneficial specialised training. They teach software packages at a professional level to film makers, artists and a range of media industry workers, as well as offering film-making and media training for NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training) teenagers in the local area. There are also a number of DIY Technology workshops including those regularly hosted by MzTEK who have expanded their operation as a result of their connections with SPACE. MzTEK are all about encouraging women to build technical skills and enter the new media sector. Growing from a small group to wide and supportive network they answer underdeveloped areas of knowledge. In addition to this, SPACE’s PERMACULTURES residency series has, to date, hosted eight residencies supporting over eleven artists, helping them explore technology and go on to show in a range of spaces.

The media lab also plugs an important gap in the art gallery and museum network. Digital and New Media arts are distinctive for collapsing boundaries between the place of production and exhibition. As a result, few existing art spaces have been in a position to fully represent it. Media labs, as well as community websites like Furtherfield and Rhizome, international festivals including ISEA and Transmediale and curatorial resources like CRUMB (the Curatorial Resource for Upstart Media Bliss) have imaginatively responded to this situation. Media labs in particular have been very successful in fostering relationships between artists and galleries. They have helped to translate not only the ideas expressed by this type of art – which can require much additional contextualisation – but also their physical installation in spaces not designed for this new breed of work.

For example, Folly recently collaborated on an experiment in the exhibition and acquisition of New Media art with the Harris Museum and Art Gallery. Entitled Current, the project saw expert panels first select works to be exhibited at the gallery (in Spring 2011) and then choose one to enter the permanent collection. Not only did this give the gallery the chance to add a timely contemporary work to their collection but it formed a useful public case study showing other institutions how they might engage with emergent art forms in various new media.

Media labs greatly contribute to the collaborative working methods the creative sector now thrives upon. Cross or interdisciplinary partnerships involve people from very different industries or working cultures combining and even reinventing the way they work in order to unearth all manner of new practices and products. Many universities, having born witness to a boom in research which straddles different academic subjects and industry sectors (due in some part to government funding imperatives around ‘knowledge transfer’), have established their own media labs. A relatively early example of this was i-DAT (the Institute of Digital Art and Technology) at the School of Computing, Communication and Electronics at the University of Plymouth. A large project with many interrelated strands is their op-sys (operating systems) network of research into architectural, biological, social and economic data and how it can be made publicly available and useful. The University of Nottingham has the Mixed Reality Lab, which was established in 1999 with £1.2 million in funding from the JREI (Joint Research and Equipment Initiative) programme as well as ongoing grants and investments. Run by Steve Benford, it hosts around eighteen PhD students providing resources for researchers and post-graduates working in areas that intersect its host department, the School of Computer Science, and associated training facility, the Horizon Doctoral Training Centre. It maintains a number of diverse projects, some of which have won prestigious awards and award nominations including Can You See Me Now, a collaboration with Blast Theory. The CoDE (Cultures of the Digital Economy) Institute at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge has a digital performance laboratory that focuses on sound-based work. Culture Lab is Newcastle University’s bespoke unit of media-lab-style flexibility, where artists work experimentally and across disciplines, and Sandbox, a similar resource, is located at the University of Central Lancashire. Another approach for universities is to partner with existing media labs. Pervasive Media Studio, a Bristol-located media lab, was set up by Watershed, a cross-artform production organisation, HP Labs and the South West Regional Development Agency. They have a partnership which runs for three years with the University of West England’s Digital Cultures Research Centre and work in a number of different ways including offering Graduate and New Talent residencies for those just starting out in their careers. The Pervasive Media Studio has helped to establish events like Igfest, the Interesting Games festival, held annually in Bristol, as well as development platforms such as Theatre Sandbox, which helps theatre makers introduce technology to their practice. They also support artists, including: AntiVJ, Duncan Speakman and Luke Jerram.

As we have seen, some labs have been nomadic or temporary while others have evolved into new incarnations. A media lab might be part of an array of dependencies with institutional responsibilities i.e. Folly, Isis Arts, Lighthouse, Pavilion, Pervasive Media Lab, PVA, Vivid and more, all of which regularly produce an abundance of quality experimentation in Digital art and culture. While new incarnations of the media lab may respond to three distinct but related phenomena: the rapidly evolving technology sector; the transient networks of geeks and digital experimenters; the need for sustainable models for innovation in industry. MadLab, in Manchester, provides space and facilitates meetings and workshops for ‘geeks, artists, designers, illustrators, hackers, tinkerers, innovators and idle dreamers’. Their ‘drop in’ events, commonly known as ‘Hacklabs’ (for example *Hack to the Future* during the Edinburgh International Science Festival), give people instant hands-on experience with all sorts of code and kit. Although hacking is still seen as a specialist and somewhat murky activity, the term is being increasingly decoupled from its conventional criminal associations and made accessible to mainstream arts territory. In January 2011 the Royal Opera House facilitated a ‘Culture Hack Day’, bringing cultural organisations such as the Crafts Council and UK Film Council together with software developers and creative technologists to usefully open up and share data. Other HackLabs may have less of an arts focus, but do have impressive resources built using the open membership model (pioneered by the likes of Backspace). The London Hackspace boasts a laser cutter, digital oscilloscope and kiln, all donated or collectively purchased.

Scattered through many of our city centres are office/studio-based working spaces which cater to the creative industries by offering flexible working environments and abundant networking and training opportunities. The Hub, in London’s Islington and Kings Cross areas (with up to thirty further Hubs in cities across the globe), gives fee-paying members access to facilities and a way of working orientated towards connecting people from across the network in cost-effective innovation. These spaces are indicative of the emphasis placed on the creative economy as the big hope for economic renewal driven by small entrepreneurs grabbing and shaping the opportunities in technology, entertainment and design.

Inspirational before Institutional

Looking briefly at some of the ways media labs have operated since the 1990s shows them as uniquely fertile spaces for all manner of shared expertise and creative innovation. They have made a fundamental contribution to Open Source culture. Working as openly and collaboratively as possible, participants have found ways of sharing process and product, while an interdisciplinary nature has revealed a plethora of creative possibilities. Fulfilling a difficult remit by offering a home for many of the emergent artistic practices currently transforming artistic activity, they have led us away from ‘art for art’s sake’ and towards work which has demonstrable meaning and lasting social and economic benefit. Large institutions might be extremely well-versed in mounting financially advantageous blockbuster exhibitions, but the beauty of media labs derives from their ability to develop and disseminate the socially-transformative systems that have already and will continue to shape the future of the arts.

A big thank you to everyone who contributed to this research despite their incredibly busy schedules and a special shout to: Simon Poulter for pulling over his car, Clive Gillman for kindly kicking things off, Sarah Cook for an innovative approach to note sharing and Peter Ride for not taking a lunch break.

You can find Charlotte’s original article on Collaboration and Freedom – The World of Free and Open Source Art http://p2pfoundation.net/World_of_Free_and_Open_Source_Art

As part of the Furtherfield collection commissioned by Arts Council England for Thinking Digital. 2011