“Flexicity, information city, intelligent city, knowledge-based city, MESH city, telecity, teletopia, ubiquitous city, wired city… [what is] a city that dreams of itself?” (Jones 2016).

This April, 28 brave souls came together for the first time to explore algorithmic ghosts in Brighton — a city known for its blending of new-age spiritualities and digital medias, but perhaps not yet for its ghosts — through the launch of a new psychogeography tour for the Haunted Random Forest festival. Unveiling machine entities hidden within seemingly idyllic urban landscapes, from peregrine falcon webcams to always-listening WiFi hotspots, we witnessed a new glimpse of an old city, one that afforded many strange moments of unexpected (and perhaps even radical!) wisdom regarding the forgotten structures, algorithms and networks that traverse Brighton daily alongside its human inhabitants.

This intervention found its greatest inspiration in the playful, crtitical, anti-authoritarian strategies of the Situationist International group that was prominent in 1950s Europe and birthed the fluid concept of dérive or “drift”, a new method for engaging with cities like Paris through “psychogeographic” walks that charted increasingly inconsistent evolutions of urban environments and their effects on individuals. “Perhaps the most prominent characteristic of psychogeography is the activity of walking,” explains Sherif El-Azma from the Cairo Psychogeographical Society. “The act of walking is an urban affair, and in cities that are increasingly hostile to pedestrians, walking [itself]… become[s] a subversive act.”

Psychogeographical drifts have been interpreted in many ways in many places, from radical city tours with no set destination, to public pamphlets meant to shock people out of their daily urban routines, to unsanctioned street artworks that explore changing architectures and hegemonies of the built environment through direct dialogues. As the Loiterer’s Resistance Movement explains, “We can’t agree on what psychogeography means, but we all like plants growing out of the sides of buildings, looking at things from new angles, radical history, drinking tea and getting lost, having fun and feeling like a tourist in your home town. Gentrification, advertising, surveillance and blandness make us sad… our city is made for more than shopping. We want to reclaim it for play and revolutionary fun.”

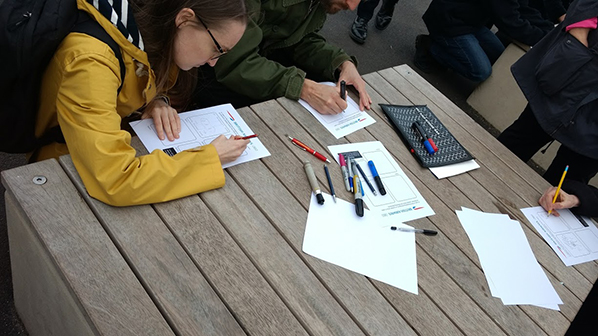

In our own interpretation of the psychogeography “play box“, people from across the UK came together from local community discussion lists, universities and creative networks to join the group. We called them ‘node guardians’ to connote a shared sense of ownership regarding both the tour nodes (which were lead not only by ourselves but also by several other brave participants, who also facilitated hands-on activities to engage listeners more deeply in the lived experiences of each machine node). We were intrigued about the moments of access, control and liberation that might be exposed when the machines, networks and algorithms that we engage with on a daily basis were revealed. In the unearthing of lesser-known instances of code-based activity (and the patterns within), we hoped to meet machine spirits, languages and loves along the way. And meet them we did.

Although the tour aimed to seek out algorithms and machines, we didn’t feel limited to influences from our current digital age. Brighton has a rich history of invention and engineering which has influenced the local geography as well as wider culture. The ghosts of Magnus and George Herbert Volk, father-and-son engineers, can be found all over the city, from Magnus Volk’s seafront Electric Railway which opened in 1883 — making it the oldest working electric railway in the world — to George’s seaplane workshop in the trendy North Laine shopping area, which went on to house a thoroughly modern digital training provider, Silicon Beach Training. Magnus Volk’s most unusual invention, though, only exists as a part of Brighton’s colourful history: the Brighton and Rottingdean Electric Railway, as it was officially called, earned the nickname the ‘daddy-long-legs railway’ as it ran right through the sea with the train car raised up above the waves on 7-meter-long legs. The railway was only in operation for 5 years from 1896 to 1901, but you can still see some of the railway sleepers for the tracks along the beach at low tide.

For a relatively small town, Brighton also played a surprisingly big role in the development of the international cinema industry. In the 1890s and 1900s, a group of early filmmakers, chemists and engineers called the Brighton School pioneered film-making techniques such as dissolves, close-ups and double exposure, and created new processes for capturing and projecting moving images. Key members of the group used the old pump house in local pleasure garden St Ann’s Wells as a film laboratory and shot the world’s first colour motion picture called ‘A Visit to the Seaside’ in Brighton in 1908, using a colour film process called Kinemacolour invented by the group. Although the city’s early passion for cinema is remembered by several blue plaques marking key locations — and the presence of the Duke of York’s cinema, the oldest continually operating cinema in the UK — we wondered how much of Brighton life had been captured in the dozens of short films made at the turn of the century, only to be lost forever?

The rest of the stops on our walking tour took in more contemporary machine ghosts, including the last remaining trace of the city’s USB dead drop network — conveniently embedded in a brick wall on the seafront above the Fishing Museum — which prompted us to ask what information people may have passed to each other before these devices were destroyed by weather and vandals. Dead drops were originally set up to be an anonymized form of peer-to-peer file-sharing that anyone could use in public spaces. They have since been embedded into buildings, walls, fences and curbs across the world. Perhaps some of our tour participants will even be inspired to set up new dead drops around the city to keep the potential for off-grid knowledge-sharing alive.

In a reversal of this spirit of anonymous digital communication, a new network of WiFi-enabled lampposts, CCTV cameras and other pieces of ‘street furniture’ has been unobtrusively installed across the city by BT, in partnership with Brighton & Hove City Council. They now eavesdrop on the personal musings of passers-by who connect to them. These hidden devices provide users with a free WiFi service, but the group wondered at what cost. Participants found themselves questioning whether BT can be trusted to keep our information secure in an age where data has become a valuable marketing commodity.

As part of our psychogeographical aim to unveil the hidden lives of once-familiar urban artefacts, we also summoned the machine ghosts of some of Brighton’s most famous (and infamous) landmarks. Looming over the city centre is a towering modernist high-rise called Sussex Heights, a building that sticks out like a sore thumb amidst the classic Regency architecture of the city’s Old Town. Yet atop the concrete tower also live families of peregrine falcons, whose nesting activities are broadcast to the world by an ever-watching webcam. Conservation groups, architects and technologies intersected in 1990 to provide a nesting box that would enable the falcons, extinct in the area at the time, to successfully breed. They now return to the tower block every spring to rear their young (except in 2002, when they chose the West Pier instead). Writing down our best wishes to this season’s hatchlings, we pasted them onto the building for future city ghosts to browse.

The other most visible instance of architectural and structural technologies descending upon the city can be seen in the new British Airways i360 viewing tower, variously described as a ‘suppressed lollipop’, a ‘hanging chad’, ‘an oversized flagpole’, an ‘eyesore’ and a ‘corporate branding post’. Even if you leave the city, you can’t get away from the sight of the 162-metre tall tower, as it is equally visible from the countrysides surrounding Brighton. It overshadows its neighbour, the beloved remains of the burnt-out West Pier, and opened exactly 150 years after the West Pier first opened in 1866. However, the ‘innovation’ in the i360’s name may be a boon to the city, as it’s expected to pour £1 million a year in the local community and potentially inspire the renovation of the West Pier. Our node-guardians bravely attempted a participatory activity outside the i360 which involved sketching out mock flight warnings to those who entered its gates; the mock flight attendants situated at the base of the i360 were less than amused by these efforts.

In most towns, the shopping centre becomes a well-known haunt for both locals and visitors to congregate, yet most people who visit Brighton’s Churchill Square shopping mall pass by the square’s large pair of digital sound sculptures without even a glance. The sculptures look like a pair of matching stone and bronze spheres, and are the type of public art that you can walk past everyday without actually looking at, but after looking into their always-observing faces once, you’ll never miss them again. They quietly interact with the sky every day through a set of complicated light sensors that trigger a series of musical notes tuned in to each orchestration and angle of the sun. As the sun rises, they call out to one another, their combined song fading away as the sky turns dark. Or at least, we are told they communicate; after a group activity to emulate the interactivities of the spheres, we found ourselves quite unsure if we had actually heard ghostly spherical music emanating from spherical mouths, or just the sound of shoppers and buses passing by.

And finally, if you’ve lived in Brighton for a while you’ve probably come across the French radio station FIP, which until a few years ago you could tune into on radios across the city. While standing in the bustling North Laine cultural quarter, we were briefly transported to Paris by one of our node guardians’ melodica renditions of Parisian cafe music, and heard the story of how a local resident introduced Brighton to FIP in the late 1990s when they started re-broadcasting the radio station out over the city. It became one of the most popular radio stations in town and transmissions continued until 2013, even surviving an Ofcom raid on the mystery broadcaster’s house in 2007 when their equipment was confiscated. The story of Brighton’s love for FIP radio, including a monthly fan-organised club night called Vive La FIP that joyously ran from clubs around the city for years, shows that as well as its own ghosts, our city is also haunted by the machines of distant places.

Indeed, from the distant ghosts of rebellions past to those who quietly slip by underfoot as we walk to the pier, the derives of this tour taught us that unearthing hidden histories of a city can bring both good and bad spirits back to life — moments of local liberation and defiance existing alongside a national state of increased surveillance, conglomeration and control. We call for future tours, psychogeographic and otherwise, that challenge participants to think about Brighton through new forms of engagement that focus on grassroots and community efforts, and their implications in the spaces and places we use every day. Only then can we determine whether the ghosts that surround us are in charge of our fates, or whether the myriad past and present struggles of this city can co-exist in collaboration.

Within the context of transmediale’s thirty-year anniversary, Inke Arns curates an exhibition titled alien matter. Housed in Haus der Kulturen der Welt, alien matter is a stand-alone product that has been worked on for more than a year, featuring thirty artists from Berlin and beyond. In the introductory text, Arns utilises her background in literature and borrows a quote from J.G. Ballard, an English novelist associated with New Wave science fiction and post apocalyptic stories. The quote reads:

The only truly alien planet is Earth. – J.G. Ballard in his essay Which Way to Inner Space?

Ballard was redefining the notion of space as ‘outer space’, seemingly beyond the Earth, and ‘inner space’ as the matter constituting the planet we live on. For him, the idea of outer space is irrelevant if we do not fully understand the components of our inner space, claiming, ‘It is inner space, not outer, that needs to be explored’. The ever increasing and accelerating modes of infrastructural and therefore environmental change caused by humans on our Earth is immense. Arns searches for the ways by which this form of change has contributed to the making of alien matter on a planet we consider secure, familiar and essentially, our home. In the age where technological advancements are so severe that machines are taking over human labour, singularity is a predominant theme whilst the human condition is reaching a deadlock in more ways than we can predict. The works shown in alien matter respond to this deadlock by shedding their status as mere objects of utility and evolve into autonomous agents, thus posing the question, ‘where does agency lie?’

Entering the space possessing alien matter, one is immediately confronted with a giant wall – not one like Trump’s, but instead a structure made out of approximately 20,000 obsolescent VHS tapes on wooden shelves. It is Joep van Liefland’s Video Palace #44, hollowed inside with a green glow coming from within at its entry point. The audience has the opportunity to enter the palace and be encapsulated within its plastic and green fluorescent walls, reminiscent perhaps of old video rental stores with an added touch of neon. The massive sculpture acts as an archaeological monument. It highlights one of Arns’ allocated subcategories encompassing alien matter, (The Outdateness of) Plastic(s); the rest are as follows: (The Outdatedness of) Artificial Intelligence, (The Outdatedness of) Infastructure and (The Outdatedness of) Internet(s) of Things.

Part of Plastic(s) is Morehshin Allahyari and Daniel Rourke’s project titled The 3D Additivist Cookbook, initially making its conceptual debut at last year’s transmediale festival. In collaboration with Ami Drach, Dov Ganchrow, Joey Holder and Kuang-Yi Ku, the Cookbook examines 3D printing as possessing innovative capabilities to further the functions of human activities in a post-human age. The 3D printer is no longer just an object for realising speculative ideas, but instead is manifested as a means of creating items that may initially (and currently) be considered alien for human utility. Kuang-Yi Ku’s contribution, The Fellatio Modification Project, for example, applies biological techniques of dentistry through 3D printing in order to enhance sexual pleasure. Through the 3D Additivist Cookbook, plastic is transformed into a material with infinite possibilities, in which may also be considered as alien because of their human unfamiliarity.

Alien and unfamiliarity is also prevalent when noticing the approach by which the works are laid out and lit throughout the exhibition. Without taking Video Palace #44 into consideration, the exhibiting space is void of walls and rooms. Instead, what we witness are erect structures, or tripods, clasping screens and lights. These architectural constructions are, as Arns points out in the interview we conducted, reminiscent of the extraterrestrial tripods invading the Earth in H.G. Wells’ science fiction novel, The War of the Worlds; initially illustrated by Warwick Goble in 1898. The perception of alien matter is enriched through this witty application of these technical requirements as audiences wander amongst unknown fabrications.

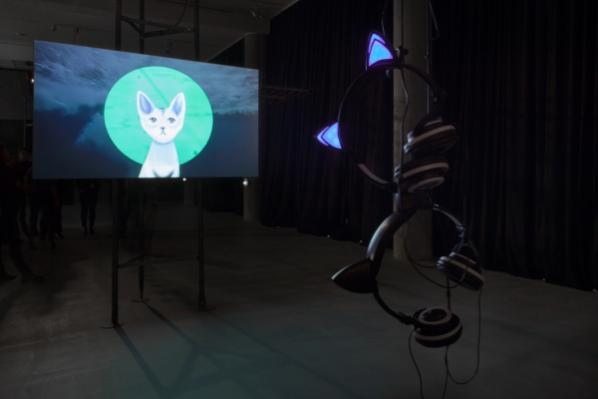

Amidst and through these alien structures, screens become manifestations for expressive AIs. Pinar Yoldas’ Artificial Intelligence for Governance, the Kitty AI envisages the world in the near future, 2039. Now, in the year 2017, Kitty AI appears to the viewer as a slightly humorous political statement, however, much of what Kitty is saying may not be far from speculation. Kitty AI appears in the form of rudimentary and aged video graphics of a cute kitten, possibly to not alarm humans with its words. It speaks against paralysed politicians, extrapolates on overloaded infrastructures of human settlement, the on-going refugee crisis still happening in 2039 but to larger dimensions and… love.

The Kitty AI is ‘running our lives, controlling all the systems it learns for us’, providing us with a politician-free zone and states that it ‘can love up to three million people at the time’ and that it ‘cares and cares about you’. Kitty AI has evolved and possesses the capacity to fulfil our most base desires and needs – solutions to problems in which human are intrinsically the cause of. Kitty AI is a perfect example when taking into consideration Paul Virilio’s theory in his book A Landscape of Events, stating:

And so we went from the metempsychosis of the evolutionary monkey to the embodiment of a human mind in an android; why not move on after that to those evolving machines whose rituals could be jolted into action by their own energy potential. – Paul Virilio in his book A Landscape of Events

Virilio doesn’t necessarily condemn the evolution of AIs; humans had the equal opportunity to progress throughout the years. Instead his concerns rise from worries that this evolution is unpredictably diminishing human agency. The starting stage for this loss of agency would be the fabrication of algorithms having the ability to speculate possible scenarios or futures. Such is the work of Nicolas Maigret and Maria Roszkowska titled Predictive Art Bot. Almost nonsensical and increasingly witty, the Predictive Art Robot borrows headlines from global market developments, purchasing behaviour, phrases from websites containing articles about digital art and hacktivism, and sometimes even crimes to create its own hypothetical, yet conceivable, storyboards. The interchange of concepts rangings from economics, to ecologies, to art, transhumanism and even medicine, pertain subjects like ‘tactical self-driving cars’ and ‘radical pranks’ for disruption and ‘political drones’ and even ‘hardcore websites perverting the female entity’.

To a certain degree, both Kitty AI and Art Predictive Bot could be seen as radical statements regarding the future of human agency, particularly in politics. There is always an underline danger regarding fading human agency and its importance for both these works and imagined scenarios – particularly when taking into consideration Sascha Pohflepp’s Recursion.

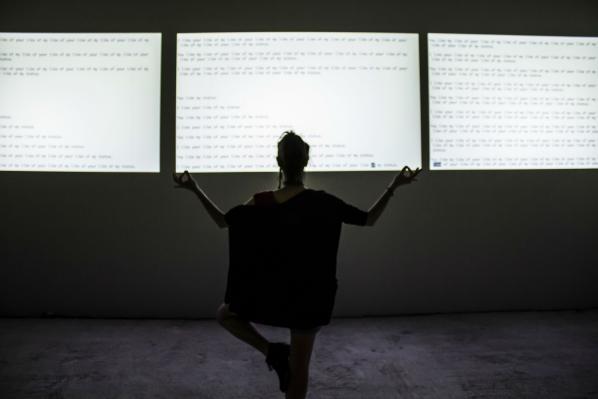

Recursion, acted by Erika Ostrander,is an attempt by an AI to speak about human ideas coming from Wikipedia, songs by The Beatles and Joni Mitchell, and even philosophy by Hegel, regarding ‘self-consciousness’, ‘sexual consciousness’, the ‘good form of the economy’, and ‘the reality of social contract’. Ostrander’s performance of the piece is almost uncanny to how we might expect AIs to understand and read through language regarding these subjects. The AI has been programmed to compose a text from these readings starting with the word ‘human’ – the result is a computer which passes a Turing test, almost mimetic of what in its own eyes is considered an ‘other’ in which we can understand that simulacra gains dialectal power as the slippage becomes mutual. Simultaneously, these words are performed by a seemingly human entity, posing the question of have we been aliens within all along without self-conscious awareness?

Throughout alien matter it becomes gradually apparent that the reason why AIs are problematic to agency is because of their ability to imitate or even be connected to a natural entity. In Ignas Krunglevičius’ video, Hard Body Trade, we are encapsulated by panoramic landscapes of mountains complimented by soothing chords and a dynamic sub-bass as a soundtrack. The AI speaks over it ‘we are sending you a message in real time’ for us to be afraid, as they are ‘the brand new’ and ‘wear masks just like you’ implying they now emulate human personas. The time-lapse continues and the AI echoes, ‘we are replacing things with math while your ideas and building in your body like fat’ – are humans reaching a point of finitude in a landscape whereby everything moves much faster than ourselves?

Arn’s potential resolution might be to foster environments of participation and understanding, as with the inclusion of Johannes Paul Raether’s Protektor.x.x. 5.5.5.1.pcp. Raether’s project is a participatory narrative following the daily structures of the WorldWideWitches and tells the story of an Apple Store ‘infiltration’ which took place on the 9th of July 2016 in Berlin. The performance itself was part of the Cycle Music and Art Festival and was falsely depicted by the media as scandalous; the Berliner Post called it ‘outrageous’. The performance featured Raether, wearing alien attire walking into the Store and allowing gallium to swim on the table. Gallium, as a substance is completely harmless substances to human beings, but if it touches aluminium the gallium liquid metal can completely dissolve the aluminium.

The installation is a means of communicating not only the narrative of the World Wide Witches, but to uncover the fixation that humans have with material metal objects such as iPhones. The installation itself is interactive and quite often engaged a big crowd around it, all curious to see what it was. It was placed on a table covered in a imitated form of gallium spread over cracked screens and pipes which held audio ports for the audience to listen to the WorldWideWitches story. Raether’s work, much like the exhibition as a whole, is immersive, engaging and participatory.

The exhibition precisely depicts alien matter in all its various and potential manifestations. The space, with all its constant flooding of sounds, echoes and reverbations, simulates an environment whereby the works foster intimacy not only with transmediale, but also with its audience. Indeed, Arns with a beautiful touch of curation, has fruitfully brought together the work of these gifted artists fostering an environment that is as much entertaining as it is contemplative. You can read more about Arns’ curatorial process and thoughts on alien matter through her recent interview with Furtherfield.

alien matter is on display until the 5th of March, in conjunction with the closing weekend of trasmediale. Don’t snooze on the last chance to see it!

All images are courtesy of Luca Girardini, 2017 (CC NC-SA 4.0)

Featured Image: With 69.numbers.suck by Browserbased

Athens Digital Arts Festival (ADAF) returned this year on the 19th to the 22nd of May with its 12th edition to bring Digital Pop under the microscope. Do machines like each other? Does the Queen dream of LSD infused dreams and can a meme be withdrawn from the collective memory?

Katerina Gkoutziouli, an independent curator and this year’s program director together with a team of curators proposed a radical rethinking of digital POP, placing the main focus on the actors of cultural production. From artists to users and then to machines themselves, trends and attitudes shift at high speed and the landscape of pop culture is constantly changing. What we consider POP in 2015 might be outdated in 2016, as the Festival’s program outlines, and that is true. But even so, in the land of memes, GIFs, likes, shares and followers what are the parameters that remain? ADAF’s curatorial line took it a step further and addressed not just the ephemerality of digital POP. It tackled issues related to governance and digital colonialism, but in a subtle and definitively more neon way.

450 artists presented their work in a Festival that included interactive and audiovisual installations, video art, web art, creative workshops and artist talks. Far from engaging in the narrative of crisis as a popular trend itself though, ADAF 2016 was drawn to highlighting the practices that reflect the current cultural condition. And the curated works were dead-on at showcasing those.

How are we “feeding” today’s digital markets then? Ben Grosser’s sound and video installation work “You like my like of your like of my status” screened a progressive generative text pattern of increasingly “liking” each others “likes”. Using the historic “like” activity on his own Facebook account, he created an immersive syntax that could as well be the mantra of Athens Digital Arts Festival 2016.

Days before the opening of the exhibition, Ben Grosser was asked by to choose the image that defines pop the most. No wonder, he replied with the Facebook “like” button. What Ben Grosser portrayed in his work is the poetics of the economy of corporate data collectors such as Facebook with its algorithmic representation of the “Like” button as the king pawn of its toolkit, that transform human intellect as manifested through the declaration of our personal taste and network into networking value.

Speaking of taste, what about the aesthetics? From Instagram and Snapchat filters to ever updated galleries of emoticons available upon request, digital aesthetics are infused with social significance. In the Queen of The Dream by Przemysław Sanecki (PL) the British politics and the Royal tradition were aestheticized by the DeepDream algorithm of Google. In an attempt to relate old political regimes and established technocracies, the artist places together hand in hand the political power with the algorithmical one, pointing out that technologies are essential for ruling classes in their struggle to maintain the current power balance. The representation of the latter was placed there as a reminder that it’s dynamic is to obscure this relation, rather than illuminate it.

However, could there be some space for some creative civil disobedience? Browserbased took us for a stroll in the streets of Athens, or better to say in the public phone booths of Athens. There, the city scribbles every day its own saying, phone numbers for a quick wank, political slogans, graffiti, tags and rhymes. With 69.numbers.suck Browserbased mapped the re-appearance and cross-references of those writings, read this chaotic network of self-manifestation and reproduced it digitally in the form of nodes. Out there in the open a private network emerged, nonsensical or codified, drawn and re-drawn by everyday use, acceptance and decline.

Can virality kill a meme? Yes, there is a chance that the grumpy cat would get grumpier once realized that its image would be broadcasted, connoted and most possibly appropriated by thousands. But how far would it go? The Story of Technoviking by Matthias Fritsch (DE) was showcased at the special screenings session of the Festival. It is a documentary that follows an early successful Internet meme over 15 years from an experimental art video to a viral phenomenon that ends up in court. Once the original footage was uploaded, it remained somehow unnoticed until some years later that it was sourced, shared, mimified, render into art installation, even merchandised by users. As a cultural phenomenon with high visibility it fails to be deleted both from servers around the world and from the collective memory even though that this was a court’s decision. In his work Matthias Fritsch mashes up opinions of artists, lawyers, academics, fans and online reactions marking the conflict between the right of the protection of our personality to the fundamental right of free speech and the direction towards which society and culture will follow in the future in regard to the intellectual property.

It’s the machines alright! Back in the days of Phillip K. Dick’s novels the debate was set over distinctions between human and machine. Since then the plot has thickened and in memememe by Radamés Ajna (BR) and Thiago Hersan (BR) things were taken a step further. This installation, situated in one of the first rooms of the exhibition, of two smartphones seemingly engaged in a conversation between them through and incomprehensible language built on camera shots and screen swipes is based on the suspicion that phones are having more fun communicating than we are. Every message is a tickle, every swipe a little rub. In memememe the fetichized device was not just a mechanic prosthesis on the human body, it was an agent of cultural production. The implication that the human might not cause or end of every process run by machines was promoted to a declaration. Ajna and Hersan have built an app that allows as a glimpse into the semiotics of the machine, a language that we can see but we can’t understand.

How many GIFs fit in one hand? If one were to trace all subcultures related to pop culture, then he or she would have to stretch time. Since they are multiplying, expiring and subcategorized not by theorists but by the users themselves and with their ephemerality condemning most of which into a short lived glory. Lorna Mills (CA) explores the different streams in subcultures through animated GIFs and focuses on found material of users who perform online in front of video cameras. In her installation work Colour Fields she is obsessed on GIF culture, its brevity, compression, technical constraints and its continued existence on the Internet.

Global pop stars, a blueprint on audience development. Manja Ebert (DE) in her interactive video installation ALL EYES ON US, one of the biggest installations of the Festival, embarked on an artistic analysis of the global pop star and media phenomenon Britney Spears. Based on music videos of the entertainer that typecast Spears into different archetypical female characters, Ebert represented each and every figure by a faceless performer. All nine figures were played by a keyboard, thus allowing the users to recompose these empty cells decomposing Spears as a product into its communicational elements.

Going through the festival, more related narratives emerged. Privacy and control, the representation of the self and the body were equally addressed. People stopped in front of the Emotional Mirror by random quark (UK/GR), to let the face recognition algorithm analyze their facial expression and display their emotion in the form of tweets while they were photographing and uploading in one or more platforms the result at the same time.

Τhe Festival presented its program of audiovisual performances at six d.o.g.s. starting on May 19 with the exclusive event focus raster-noton, featuring KYOKA and Grischa Lichtenberger.

ADAF 2016 brought a lot to the table. Its biggest contribution though lies in offering a great deal of stimuli regarding the digital critical agenda to the local digital community. ADAF managed to surpass the falsely drawn conception of identifying the POP digital culture just as a fashionable mainstream. On the contrary it highlights it as a strong counterpoint.

“I-love-you: the figure refers not to the declaration of love,

to the avowal,

but to the repeated utterance of the love cry.”

Roland Barthes, The Lover’s Discourse. Fragments, 1977.

Designed and published online on October 14th 2004[1], restored for The Wrong (Again) on November 1st 2015, the website I Love You by French artist Jacques Perconte[2] is not only a wonderful achievement of his research on image files visualization through the Internet, but also a fundamental piece of artwork for three reasons: first, it crystallizes a history of audiovisual technologies in the web age; next, it allows the analysis of his singular inventions on plasticity which are shaped by the offensive processes and techniques Perconte has developed until 2015; finally, it makes explicit the artist’s constant will to put the body to the test of digital technologies (in this case the partner’s body) and to literally inject life (each and every thought, interest, feeling, emotion, excitement, and desire aroused in him by the beloved body).

Two events in 2003 gave birth to this piece: a publication proposal from French publisher Didier Vergnaud of a book with the digital photographs of bodies he had been taking tirelessly; and his romantic encounter with the woman who would become his partner, muse and model, Isabelle Silvagnoli. I Love You merges two stories, two passions. The one with Isabelle blooms in May 2003[3]; at this time, Perconte has already an extensive experience of digital technologies that he had developed since 1995[4].

At the Bordeaux University, when Perconte notices that a computer is connected to the rest of world, he becomes aware of the technical and aesthetic issues of the digital network, issues largely ignored at this time. His quick mastering of how the web operates leads to a decisive work on “the digital bodies”: three image generator websites (ncorps) and four films made by re-filming multiple loops of these animated pictures. This series denotes that Perconte has assimilated four essential dimensions of the digital.

First, he notes the image exists primarily in the state of a compressed digital signal that needs to be displayed; the signal recorded and stored as a file is a model, shaped by algorithms; its visualizations change only according to the codecs and the supports. Next, he distinguishes the human dimension of the web: the bodies of the users surfing the Internet on their computers and interlinking one another.

Then, the material dimension: the computers interconnected by an abundance of servers all around the world which produces a random digital time; indeed Perconte noticed the connection time to the hosting server of his websites was unpredictable since the answering time fluctuated according to the Internet traffic density, the connection’s and the browser’s qualities, and the computer’s performance executing the query.

So he notices the fantastic system failures: “when the first JPEGs popped up on websites, it wasn’t unusual for a picture to be only partially displayed. Sometimes, this happened to produce strange distortions in the image. (…) Every now and then, the image would totally turn into an abstract composition with amazing colors.”[5] Consequently, these fluctuations of display reveal a prodigiously fertile field of investigation: recoding the visualization. Finally, the web can be defined by the coexistence of places, bodies, machines, protocols and programs interacting in complex ways as an evolving ecosystem. Thus, a device aimed at transforming models could be designed (model meaning both the person the artist reproduces with forms and images and the coded reduction), as GIF or JPEG sequences animated on a website. Since the parameters involved in the visualization of these sequences are renewed at each connection, Perconte knows these metamorphosis will be unlimited and give birth to n bodies [corps]). This research allowed Perconte to establish, by 1996, a stable platform aimed at recoding the visualization within the web to ultimately break the limitations of the model’s code into which the digital signal is reduced.

As he undertakes assembling photographs of Isabelle for the book project (38 degrés), this experience of the web will come back to him. The collection of several thousands digital pictures springs from the extensive exploration of the beloved body’s patterns and the obtained signals he looped (he retakes the displayed pictures several times), in an attempt to test the representation of love. The problem is twofold. On the one hand, this collection can only be unlimited since the observation is inexhaustible as he puts it: “when I think about her body, I dream of landscapes so large that one gets lost completely, there is so much to recognize, kilometers of skin where warmth rules, a soft, almost empty desert. Beauty, immensity where every vibration of light pushes the colors to reveal themselves in new ways. The variations (…) are endless.”[6] Furthermore, despite experimental photography techniques, he quickly reaches the limits of how much an image is capable of expressing absolute love. In order to find and visualize this love present within these files, Perconte selects and ranks hundreds of these images in a database and places them in an ecosystem on the web.

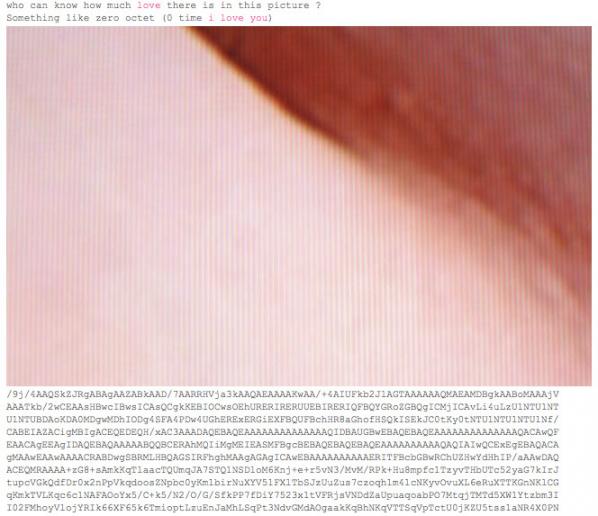

Perconte developed a server-side program by writing an open source application in PHP, the love writing program[7], in order to quantify the love present in the source code of these digital images displayed on the web. Love being unquantifiable by definition, the artist must add an arbitrary but rigorous calculation. This quantification is performed by the application triggered when a user clicks on one of the images of the collection: it calculates a specific variable by taking into account all the physical parameters of the connection but also the mathematical constants of proportions and universal harmony – ∏ and F (the golden section); then the application opens the image file, transforms it as a hexadecimal code and substitutes every occurrence of the sought value by the phrase “I Love You,” thus changing the architecture of the code describing the image. The browser requested to visualize the image compiles the modified code, but can only display it partially, at the cost of radical visual transformations, such as reconfigurations pixel structures, the emergence of new colors resulting in the reinterpretation of original motifs or subjects; the greater the amount of pure love, the more intense the abstraction. The motifs of the beloved body can mingle or merge entirely with the figuration of love. The browser is sometimes unable to visualize the image resulting in the appearance of a broken icon with a quote from Roland Barthes: “To try to write love is to confront the muck of language: that region of hysteria where language is both too much and too little, excessive (…) and impoverished (…).”[8]The broken icon evokes a digital iconoclasm, but furthermore signifies the limitations of visualization protocols that have been overtaken by an overflow inexpressible love. This substitution in the image source code of a value by the literal writing of love, raises the Perconte’s program to a “loveware.”[9]

Not only has Perconte given life to this website, but he has been maintaining it for the eleven years he has been sharing his life with his partner. First and foremost, he constantly upgrades it. Indeed, he programmed on February 14th 2005 an “I Love You Collection” of all the “I Love You’s” which will be written in the images’ source code; from this description, the “Love Counter” determines the number of “I Love You’s” and their transposition in bytes: “This is a concrete and scientific way to know as precisely as possible how much love is streamed online, and more importantly how much love is contained in this work. Every time a picture is displayed and the code modified by love messages, the counter is updated. The more time goes by, the more love grows.”[10] Thus, the users themselves, without suspecting it, testify to the history of this Perconte’s love for his partner, write this love, perpetuate and amplify it. Donating his images to the network, leaving it to others to speak for him, the artist is no longer the excessive delirious lover (wonderfully described by Barthes[11]), but one who loves. Then, the artist updates his website on a regular basis.

For each exhibition he replaces the image collection and operates small technical changes in order to avoid falling behind on the developments of the web. Furthermore, he designed a photographic exhibition of this work started in 2003, It’s All About Love, from January 17th to April 17th 2008 in Pessac, where he gives to the public a synthesis and extension of the project, in the form of prints and animations on iPods[12]. Finally, he undertakes a complete restoration of the website in 2015. Indeed, I Love You has suffered from a rapid disruption of the web and the visualized pictures often began to show large gray patches. The invitation from The Wrong gave him the opportunity to get back to this core piece. The solution – consisting in placing the website in its original technological context, that is to say, on a server with the same configurations as in 2004 – was met with refusal from the web hosting providers. This is how he decided to work with one of his students of Chalon-sur-Saône, Garam Choi, a true code virtuoso, in order to rethink the programming of the website according to a large principle which governs web in recent years.

From the beginning of the web until the posting of I Love You, applications were executed by servers. However, with the exponential increase in web traffic, servers quickly became overloaded; moreover, computers have seen their computing power and storage soar while other programming languages, like JavaScript, gained importance. Thus, the logic that governed web-programming moved applications to the client-side. Choi and Perconte have therefore developed identically, from the original program in PHP, an application written in JavaScript so that it could be interpreted on the client-side, while maintaining the database on a server. The issue at stake was to create a dialogue between the server and the client-side application, especially to quantify the number of “I Love You’s” and write it into the database. Indeed, server specifications entail technological obstacles as soon as the instructions are not in compliance with the protocol. But the artist was quickly able to find a way to instruct the program to circumvent the prohibitions. Indeed, not only does he operates the substitution technique to modify the images source codes, but uses it as a trick to fool the server. The idea is to do it as if the client were loading an image from the server to display it; but the called address executes instead a script, in other words, instead of the image URL, the number of “I Love You’s” is shown.

The website restoration therefore takes hold of the website’s programming in the 2010’s, but reinvents it with ingenuity. It also alerts the Internet user on how some multinationals IT companies (Apple, Google) consider the universality of the net: Chrome hinders some images display, while Safari denies their visualization. Also, in the latter case, Perconte and Choi have provided the following message to the attention of the user: “Safari is not ready for love. It’s still blind.” On the contrary, the Firefox browser, developed by a global open-source community, allows optimal operation of I Love You at the exact replica of the first 2004 version. Indeed, Mozilla defends a free Internet that would be “a global public resource that must remain open and accessible” in which “everyone should be able to shape the Internet and their own experiences on the Internet.”[13] That is why the growing love of I Love You does not only symbolize the artist in his couple, but elevates itself to a principle of universal union and intimate communion through the web: a set of values that affirm a convivial conception of society resisting consumerist models imposed by technical industries, and taking the power of the Web back in the hands of all users.

I Love You is therefore crucial for the Internet user, the historian, the media theorist, the film analyst, the archivist and the curator of the twenty-first century. It invents a thought of the program as a plasticity fertilization tool through digital visualization technologies understood as open and unstable. It successfully manages to offer bright and virtuoso processes and techniques of recoding, exciting insights on the operation of some display supports and devices, along with their history and unrelenting criticism, and the refined and infinite visual writing of the story of a man in love through a limitless range of radical visual forms generating a pure aesthetic delight. It is an artwork that lives and grows thanks to the Internet users as a digital lining of a relationship blossoming in the world, and which, since it has adapted and transformed to the changing technological environment, becomes the figurehead of a libertarian conception of the Internet and digital technologies in general.

Warmest thanks to Nicole Brenez, Gaëlle Cintré, Kamilia Kard,

Filippo Lorenzin, Zachary Parris,

Jacques Perconte and Isabelle Silvagnoli.

(In)exactitude in Science : http://inexactitudeinscience.com

and I Love You : http://iloveyou.38degres.net

Text is translated from the first french extended edition : http://www.debordements.fr/spip.php?article431

Art, to misparaphrase Jeff Koons, reflects the ego of its audience. It flatters their ideological investments and symbolically resolves their contradictions. Literature’s readers and art’s viewers change over time, bringing different ways of reading and seeing to bear. This relationship is not static or one-way. The ideal audience member addressed by art at any given moment is as much produced by art as a producer of it. Those works that find lasting audiences influence other works and enter the canon. But as audiences change the way that the canon is constructed changes. And vice versa.

“The Digital Humanities” is the contemporary rebranding of humanities computing. Humanities for the age of Google rather than the East India Company.

Its currency is the statistical analysis of texts, images and other cultural resources individually or in aggregate (through “distant reading” and “cultural analytics“).

In the Digital Humanities, texts and images are read and viewed using computer algorithms. They are “read” and “viewed” by algorithms, which then act on what they perceive. Often in great number, thousands or millions of images or pages of text at a time, many more than a human being can consider at once.

The limitations of these approaches are obvious, but they provide a refreshing formal view of art that can support or challenge the imaginary lifeworld of Theory. They are also more realistic as a contemporary basis for the training of the administrative class, which was a historical social function of the humanities.

Digital Humanities algorithms are designed to find and report particular features of texts and images that are of interest to their operators. The most repeated words and names, the locations and valences of subjects, topics and faces and colours. They produce quantitative statistics regarding works as a whole or about populations of works rather than qualitiative reflection on the context of a work. Whether producing a numeric rating or score, or arranging words or images in clouds, the algorithms have the first and most complete view of the cultural works in any given Digital Humanities project.

This means that algorithms are the paradigmatic audience of art in the Digital Humanities.

Imagine an art that reflects their ego, or at least that addresses them directly.

Appealing to their attention directly is a form of creativity related to Search Engine Optimization (SEO) or spam generation. This could be done using randomly generated nonsense words and images for many algorithms, but as with SEO and spam ultimately we want to reach their human users or customers. And many algorithms expect words from specific lists or real-world locations, or images with particular formal properties.

A satirical Markov Chain-generated text.

The commonest historical way of generating new texts and images from old is the Markov Chain, a simple statistical model of an existing work. Their output becomes nonsensical over time but this is not an issue in texts intended to be read by algorithms – they are not looking for global sense in the way that human readers are. The unpredictable output of such methods is however an issue as we are trying to structure new works to appeal to algorithms rather than superficially resemble old works as evaluated by a human reader.

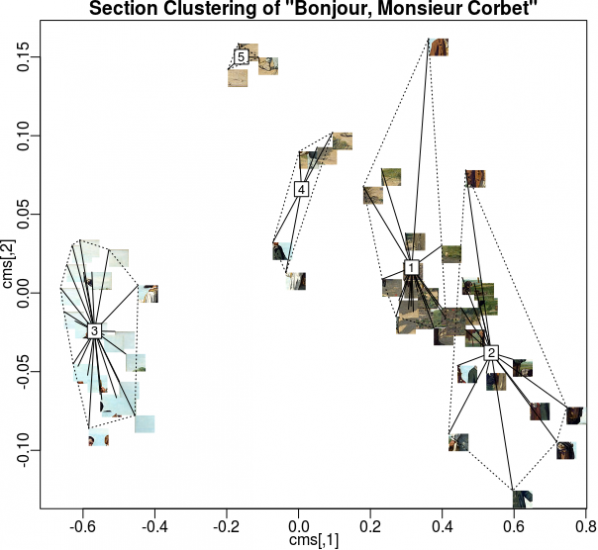

The two kinds of analysis commonly performed on cultural works in the Digital Humanities require different statistical approaches. Single-work analyses include word counts, entropy measures and other measures that can be performed without reference to a corpus. Corpus analysis requires many works for comparison and includes methods such as tf-idf, k-means clustering, topic modeling and finding property ranges or averages.

ugly despairs racist data lunatic digital computing digital digital humanities digital victim furious horrific research text racism loathe computing text humanities betrayed digital text humanities whitewash computing computing cheaters brainwashing digital research university university research falsifypo pseudoscience research university worry research data technology computing humanities technology data technology research university research university computing greenwasher cruel computing university data disastrous research digital guilt technology university sinful loss victimized computing humiliated humanities university research ranter text text technology digital computing despair text technology data irritate humanities text data technology university heartbreaking digital humanities text chastising text hysteria text digital research destructive technology data anger technology murderous data computing idiotic humanities terror destroys data withdrawal liars university technology betrays loathed despondent data humanities

A text that will apear critical of the Digital Humanities to an algorithm,

created using negative AFINN words & words from Wikipedia’s “Digital Humanities” article

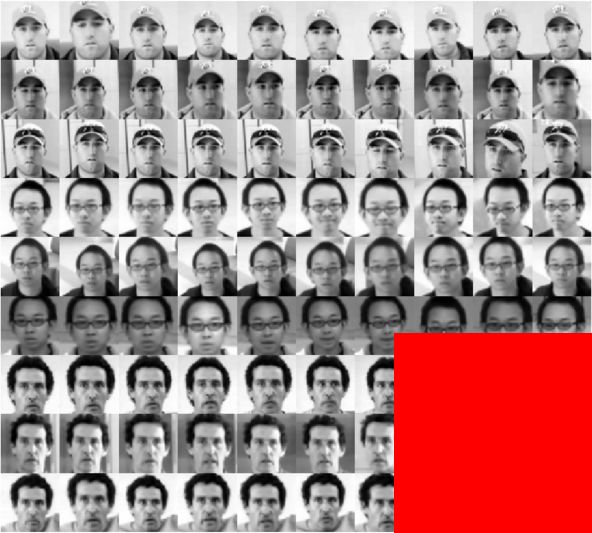

We can use our knowledge of these algorithms and of common training datasets such as the word valence list AFINN and the Yale Face Database, along with existing corpuses such as flickr, Wikipedia or Project Gutenberg, to create individual works and series of works packed with features for them to detect.

web isbn hurrah superb breathtaking hurrah outstanding superb breathtaking isbn breathtaking isbn breathtaking thrilled web internet hurrah media web internet outstanding thrilled hurrah web thrilled media thrilled superb breathtaking art breathtaking media superb hurrah superb net artists outstanding internet outstanding net superb thrilled thrilled art hurrah based outstanding superb net internet artists web art art artists internet breathtaking based net hurrah outstanding thrilled superb hurrah media based outstanding media art artists outstanding isbn based net based thrilled artists isbn breathtaking

A text that will appear supportive of Internet art to an algorithm,

made using positive AFINN words and words from Wikipedia’s “Internet Art” article.

When producing textual works for individual analysis, sentiment scores can be manufactured for terms associated with the works being read. Topics can be created by placing those terms in close proximity. Sentence lengths can be padded with stopwords that will not affect other analysis as they will be removed before it is performed. Named entities and geolocations can be associated, given sentiment scores, or made the subjects of topics. We can structure texts to be read by algorithms, not human beings, and cause those algorithms to perceive the results to be better than any masterpiece currently in the canon.

When producing textual works to be used in corpus analysis individual or large volumes of “poisoning” works can be used to skew the results of analysis of the body of work as a whole. The popular tf-idf algorithm relates properties of individual texts to properties of the group of texts being analysed. Changes in one text, or the addition of a new text, will skew this. Constructing a text to affect the tf-idf scores of the works in a corpus can change the words that are emphasized in each text.

The literature that these methods will produce will resemble the output of Exquisite Code, or the Kathy-Acker-uploaded-by-Bryce-Lynch remix aesthetic of Orphan Drift’s novel “Cyberpositive“. Manual intervention in and modification of the generated texts can structure them for a more human aesthetic, concrete- or code-poetry-style, or add content for human readers to be drawn to as a result of the texts being flagged by algorithms, as with email spam.

When producing images for individual analysis or analysis within a small corpus (at the scale of a show, series, or movement), arranging blocks of colour, noise, scattered dots or faces in a grid will play into algorithms that look for features or that divide images into sectors (top left, bottom right, etc.) to analyse and compare. If a human being will be analysing the results, this can be used to draw their attention to information or messages contained in the image or a sequence of images.

When producing image works for corpus analysis we can produce poisioning works with, for example, many faces or other features, high amounts of entropy, or that are very high contrast. These will affect the ranking of other works within the corpus and the properties of the corpus as a whole. If we wish to communicate with the human operators of algorithms then we can attach visual or verbal messages to peak shift works, or even in groups of works (think photo mosaics or photobombing).

The images that these methods will produce will look like extreme forms of net and glitch art, with features that look random or overemphasized to human eyes. Like the NASA ST5 spacecraft antenna, their aesthetic will be the result of algorithmic rather than human desire. Machine learning and vision algorithms contain hidden and unintended preferences, like the supernormal stimulus of abstract “superbeaks” that gull chicks will peck at even more excitedly than at those of their actual parents.

Such image and texts can be crafted by human beings, either directed at Digital Humanities methods to the exclusion of other stylistic concerns or optimised for them after the fact. Or it can be generated by software written for the purpose, taking human creativity out of the level of features of individual works.

Despite their profile in current academic debates the Digital Humanities are not the only, or even the leading, users of algorithms to analyse work in this way. Corporate analysis of media for marketing and filtering uses similar methods. So does state surveillance.

Every video uploaded to YouTube is examined by algorithms looking for copyrighted content that corporations have asked the site to treat as their exclusive property, regardless of the law. Every email you send via Gmail is scanned to place advertisements on it, and almost certainly to check for language that marks you out as a terrorist in the mind of the algorithms that are at the heart of intelligence agencies. Every blog post, social media comment and web site article you write is scanned by search and marketing algorithms, weaving them into something that isn’t quite a functional replacement for a theory. Even if no human being ever sees them.

This means that algorithms are the paradigmatic audience of culture generally in the post-Web 2.0 era.

Works can be optimized to attract the attention of and affect the activity of these actors as well. Scripts to generate emails attracting the attention of the FBI or the NSA are an example of this kind of writing to be read by algorithms. So are the machine-generated web pages designed to boost traffic to other sites when read by Google’s PageRank algorithm. We can generate corpuses in this style to manipulate the social graphs and spending or browsing habits of real or imagined populations, creating literature for corporate and state surveillance algorithms.

Image generation to include faces of persons of interest, or with particular emotional or gender characteristics, containing particular products, tagged and geotagged can create art for Facebook, social media analytics companies and surveillance agencies to view. Again both relations within individual images and between images in a corpus can be constructed to create new data points or to manipulate and poison a larger corpus. Doing so turns manipulating aesthetics into political action.

Cultural works structured to be read first by algorithms and understood first through statistical methods, even to be read and understood only by them, are realistic in this environment. Works that address a human audience directly are not. This is true both of high culture, studied ideologically by the algorithms of the Digital Humanities, and mass culture, studied normatively by the algorithms of corporation and state.

Human actors hide behind algorithms. If High Frequency Trading made the rich poorer it would very quickly cease. But there is a gap between the self-image and the reality of any ideology, and the world of algorithms is no exception to this. It is in this gap that art made to address the methods of the digital humanities and their wider social cognates as its audience can be aesthetically and politically effective and realistic. Rather than laundering the interests that exploit algorithmic control by declaring algorithms’ prevalence to be essentially religious, let’s find exploits (in the hacker sense) on the technologies of perception and understanding being used to constructing the canon and the security state. Our audience awaits.

The text of this article is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

Featured image: Drone Shadows by James Bridle

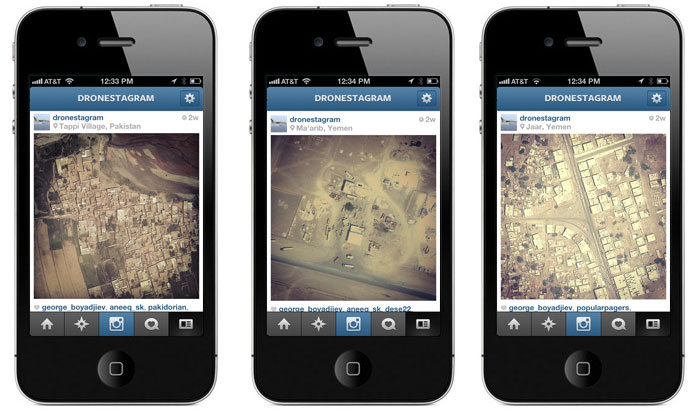

I met the London-based artist, publisher and programmer James Bridle in Oslo back in May 2013, as part of the conference The Digital City. Bridle was in Oslo to speak about drones, algorithmic images, and urban software. His most recent art projects, Dronestagram and Drone Shadows, have caught a great deal of interest by the popular press, with recent features published in the Wall Street Journal, Dazed & Confused and Vanity Fair. Bridle is no stranger to getting the timing right. Addressing issues of drone surveillance and invisible technologies in ‘leaky’ Snowden times, or manage to get a bunch of academics, writers and critics, to talk about the birth of a new movement – based entirely on a Tumblr-blog he called the New Aesthetic – surely qualifies as good timing. In our conversation, Bridle, or the New Aesthetic’s commander-in-chief as Vanity Fair calls him, reveals that he never really meant to talk about aesthetics. It is not the printed pixels on a pillow, so often taken to be emblematic of the New Aesthetics by its critics, that is of interest to Bridle. Rather, Bridle wants to encourage a conversation about the kinds of images and sensibilities that emerge from algorithmic and machinic processes, and the embedded politics of systems that make certain images appear (and disappear).

Taina Bucher: Hi James, would you care to tell us a little bit about your background?

James Bridle: I studied computer science and artificial intelligence at UCL, University of London. By the time I finished, I hated computers so much that I went on to work in traditional book publishing.

It quite quickly became clear through working as an editor and publisher that publishing was heading for crisis, because it is an industry that is full of people who are afraid of technology. So I went on to specialize in e-publishing, looking at what happens to books as they become digital, which gradually grew into an examination of other cultural objects, and what happens to them as they get digital and the nature of technology itself.

T: Do you think that your background in computer science influences the ways in which you think about art and artistic practices?

J: I consider myself as having a background in both, and I actually think that having the literacy in both is incredibly valuable.

T: Interesting, what does this literacy in art mean to you?

J: Being able to speak the language of it and to be able to communicate it. Not just having an understanding of it, but also to be able to talk to people in publishing and the arts about the Internet without scaring them, and also to be able to talk to people in technology. They are still two separate cultures but it is possible to translate between them.

T: Do you consider software or code to be the material of your artistic practices?

J: Sometimes. I do think though that this should be the last concern. There are different ways of describing the world; materials are just a way of expressing it.

T: How then does software influence the kinds of expressions that you create?

J: Not only the material, but also the ideas coming from software are important here. There are plenty of ideas coming from technology that become really valuable as they are applied in the arts, for instance from the tradition of systemic analysis. You know, breaking things down to basic principles, algorithmic type steps, is a really valuable tool of analysis. It is also a dangerous one, as it can give you a systemic engineering view on problems.

T: You’ve said that you’ve been accused of romanticising the robot, or rather, that the New Aesthetic has been accused of this. What do you think the critics mean by that?

J: Well I do understand it in a way, because one way of talking about these things is really to anthropomorphize automated systems. When you do that, you bring a whole bunch of other questions into it, like whether these systems have a separate agency or not, whether they truly see and understand the world in ways that we do not entirely understand, or whether they are purely tools of human imagination. In order to understand these things, I think sometimes it is necessary to take a position, you know, talk about it as if it is true, and then you learn more by finding out where that description breaks down and where it doesn’t apply.

T: What is the New Aesthetic anyways? An aesthetic of the digital, or a digital aesthetic?

J: I never really meant to talk about aesthetics. The New Aesthetic is not about aesthetics. One of the earliest keys to it was looking at some of these images that result from systems, looking at things like computer vision and how the world is seen through machines, but really this is a shorthand of how the world is mediated through technologies in all kinds of ways, not just aesthetically. The aesthetic is a starting point where you can visually notice these things, but I am really interested in what it reveals about underlying things. I am not interested in notions of beauty or the aesthetics of it.

T: We could also understand aesthetics in terms of ways in which something is made to appear in certain ways. To talk about software aesthetics in these terms, would imply the view from technology, as opposed to the view on technology.

J: Not only the ways in which these technologies influence the ways we see things though, but the ways in which we think about them and understand them is important. By using some technology you’re bound by some of its biases and if you don’t understand what some of these biases are, then you’re slightly fooled by them. There is always an underlying politics to these things, and if you’re not aware of it, then you’re a victim of it.

T: Is it the artists’ job to reveal these biases in a certain sense?

J: Don’t know about job, but yes, that’s why I am doing it. The interesting thing to me is to explore deeper levels of these things. Getting a bit closer to the meaning and the underlying biases.

T: How do you work with, or get at the biases of technology?

J: By exploring and getting a technical understanding of it, but also by looking at how technologies actually operate in the world.

T: Do you think that a certain sense of code literacy is needed then?

J: I struggle a bit with that. I think that I do, the way that I work. Having a technical understanding of how things work is really, really important. But I am always struggling to figure out if it’s possible to do that without having the possibility to read the code. It is hard to study a foreign culture without knowing its language. Put differently, great artists mix their own paint. They have a fundamental understanding of the material. I think that if you’re making work with and about technology, and if you don’t understand how that technology works, you’re going to miss out on a huge chunk of what the technology is capable of doing. There is a lot of digital art that is very, very basic, because the people who are making it don’t actually understand how it works.

T: Could we see your work as a kind of software studies?

J: Yes, probably could see it like that. Some parts of software studies definitely informs my work, concepts like code/spaces. My practice is situated between art and technology and the stuff that always interests me, is when domains like software studies meets other domains, for instance where software studies meets architecture. I’m really interested in architecture because it is such a situated practice. It is not like art or high-flown critical theory, which is kind of above the world; it really has to be rooted in the world. The crossovers are what are interesting. People like Eyal Weizman or Keller Easterling, who talk about how architecture shapes not just the physical domain, but also the legal and political spaces.

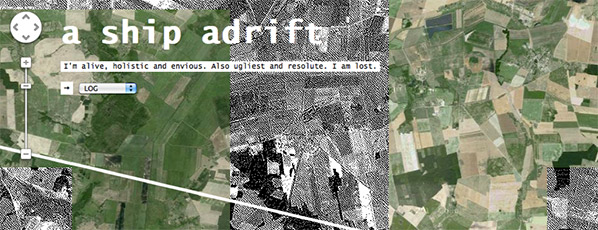

T: One of your projects that I really like is “A ship adrift”. Besides being a bot, how can we understand this “ship”? How does it work and which data sources does it use?

J: It is part of a larger art project in London called “A room for London”, which was a one-room hotel built on top of another building on the south bank of London in the shape of a ship. It was both a one-room hotel that you could book and stay for the night, and it was used for art things, music projects and other events. I was asked to do something that connected it to the Internet, to some kind of an online component. I didn’t want to do something that was totally separate, but something that was rooted in this idea of the ship, and its actual location. One of the major things is that it is a ship that doesn’t go anywhere. It fails at the first condition of being a ship.

I put a weather station up on the building to monitored wind speed, direction, and a bunch of other stuff, and took all the data from that, to drive an imaginary ship. For example, starting in January, and from the physical location of the ship: If the wind blows 5 miles an hour, my imaginary ship would move five miles east or wherever the wind was blowing. So this thing was driving friction-free. As it’s going, it knows its own location and searching the Internet for stuff nearby. It is looking for information on the web that also has a geographical tag to it. Good sources for that are Wikipedia as there are lots of articles that have a physical location tied to it, so you can look those up and read those in. My favourite source was Grindr, a sex network for Gay men that was geo-tagged. Unfortunately they did upgrade the security there three months into my project, so I no longer had access to that data. I was also feeding it other texts as well. There was for instance a sub-thread running through the whole project around Joseph Conrad who I’m a huge fan of. So I gathered all these texts and running really, really basic language generation text programs on it, the same kinds of programs that generate spam emails. So it is not intelligent in any meaningful way. It is really about how we read broken texts. I just quite love that, because it is really part of the vernacular of the web. It’s what language sounds like when it is broken through machines. It is also quite empathetic, and it makes us examine our own feelings towards technology.

A Ship Adrift by James Bridle

T: Let me just quote you: “Forget controlling the machine; impersonate it. Fake it till you make it, like horse_ebooks, like A Ship Adrift” (Impersonating the Machine). How far would you take your own aphorism? Did your bot actually make it?

J: You can pick your criteria of success. My criterion of success is to produce an emotional response in me and in other people as well. And in this case, other people were really following along, particularly on Twitter. It had it’s own voice, although it was still generated by a semi-autonomous software system. It is not a bot really, it is not intelligent, it does not have agency, but it is generating a feeling about machines, which I think is important.

T: How did people respond to the ship?

J: Someone called it a ‘Robot Polari’. Polari is a European argot, which is almost gone now. Polari was a secret language that originated in circuses, travellers and theatre companies in the 19th century and became the secret language of gay men. It was a kind of coded language they used to communicate. Argots like that served multiple purposes. On the one hand concealing communication from the outside world that may be hostile to it, but also within the group, in terms of creating a bond between its members. So for me, the ship adrift felt kind of like an argot to the machines; machines kind of identifying themselves to each other, semi-protecting themselves.

T: There is a tendency to treat bots as ‘fakes’, as somehow inauthentic beings, which is really being framed as an increasing problem online. Why are we so obsessed with this notion of the inauthentic of that which is not entirely human?

J: That is a really good question. This problem of authenticity and technology extends much further. The whole New Aesthetic project springs in some extent from trying to understand what people consider being authentic digital experiences. I think we have this quite big problem, which is that we are so unsure with how technology operates that we have a deep distrust of it.

I think Instagram is a really good example of that. The entire mechanism of Instagram is predicated on applying the filters of analogue cameras to digital photographs, which for me is a process of authenticating. We are aware on some level that these photos are apparently less stable and less persistent than the photographs you keep in a shoebox, some server going down could delete them any moment. There is a precarity to them. We’re all the time trying to authenticate stuff, and all of this is tied to our fear and confusion around digital things.

T: It seems that questions of the invisible, or making what is seemingly kept from view visible, is a core element of your artistic practice. What is it about the invisibly visible and visibly invisible that intrigues you so much?

J: Take the drone programme. It is a political programme. It’s a natural extension of our international relations and we’ve developed a set of technologies to address these relations. The drone is perhaps the most emblematic and also a largely invisible one. It’s really been going on for the past decade, but it has only very recently become a very political issue. This is due to the fact that drones are largely physically invisible. They are secret technologies that no one ever really sees. In all kinds of ways: You don’t see them in newspapers, until very recently, and you don’t see them in movies. The invisibility is conferred by them being seen as technological objects. Because they are technologies, they are not criticized in a way that a policy, or a person, or human actions can be. Even though they are all about policies and human politics. Because humans in general, are not technologically literate, they just back off from that. For most people, it is just the way it is.

T: Would you say that it is the technology itself that is actually invisible, or the institutions and the kind of political work going on in the background of these drones?

J: Both of those things. This is where it gets interesting, because a lot of this technology materializes that political will. Stuff that would have been entirely secret previously, now exists as objects in the world. There is this incredible paradox, technologies both reify and materialize power and human desires, but are made invisible in a way that makes them beyond comprehension.

T: How have people reacted to your drone work?

J: Well, people have had discussions about drones they would not have had otherwise. But I hope that my work also raises questions about technology and the media on a deeper level, not just in terms of the drone programme.

T: Now that even our police forces are starting to talk about smart policing and using drones for surveillance purposes, what do you think would be an appropriate response?

J: I am not sure how the situation looks like in Norway. But London is the most heavily surveilled city on earth. Yet, we don’t talk about it much. For the most part everyone seems to be ok with that. It is a matter of technology, and thus easy for most people to ignore. If drones raise greater fears about surveillance, then maybe that will push back on all forms of surveillance. I’m not particularly more worried about drone surveillance than I am with cameras on a building. They are all functions of the same thing, but if it actually makes people think more about surveillance and control mechanisms then that is a fairly interesting way for it to go.

T: Maybe we’ll just end up in an overly visible state, where the amount of visibility goes counter to what it is supposed to do. If everyone is highly visible all the time, then the questions becomes one of analytics. How are we to make sense of this visibility?

J: The best I can hope for is a kind of democratization. We should all have access to them and be able to see through them as well.

T: What is up for you next?

J: I think I will have to take a lot of the momentum of this drones work and try and push it back up a layer to the political and legal space. I’ve never been interested in just the drones. I’ve always been interested in the wider implications of the technologies that they embody. So the drones are just the start, but there is a much larger conversation we should be having. So the question is how we can expand this conversation to those other areas and not just make it about weird sexy planes.

T: How does your work connect with social media? Do you use social media as a useful platform, or a point of critique itself? Does social media in any way change the possibilities of your artistic practice?

J: Yes, totally. I represent myself, and I have my own audience. It amplifies the things that I do, but I don’t theorize too much about it. That would be a whole rabbit hole to go down to. And I’m very well aware that I’m living inside, so it would be difficult to have such a critical eye on, because I’m so involved in it. I think that I will at some point though. One of the key tenets of my practice is not to perform manifestos, I don’t want to draw or come to any conclusions because I think we are at such an early stage with these social networks and social media, and the Internet in general that we don’t even have the critical frameworks to talk about it seriously, let alone come to any serious conclusions about it, yet.

Featured image: The Simplex Algorithm

Algorithms have become a hot topic of political lament in the last few years. The literature is expansive; Christopher Steiner’s upcoming book Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World attempts to lift the lid on how human agency is largely helpless in the face of precise algorithmic bots that automate the majority of daily life and business. So too, is this matter being approached historically, with Chris Bishop and John MacCormick’s Nine Algorithms That Changed the Future, outlining the specific construction and broad use of these procedures (such as Google’s powerful PageRank algorithm, and others used in string searching, (i.e regular expressions, cryptography and compression, Quicksort for database management). The Fast Fourier Transform, first developed in 1965 by J.W Cooley & John Tukey, was designed to compute the much older mathematical discovery of the Discrete Fourier Algorithm,* and is perhaps the most widely used algorithm in digital communications, responsible for breaking down irregular signals into their pure sine-wave components. However, the point of this article is to critically analyse what the specific global dependences of algorithmic infrastructure are, and what they’re doing to the world.

A name which may spring forth in most people’s minds is the former employee of Zynga, founder of social games company Area/Code and self described ‘entrepreneur, provocateur, raconteur’ Kevin Slavin. In his famously scary TED talk, Slavin outlined the lengths Wall Street Traders were prepared to go in order to construct faster and more efficient algo-trading transactions: such as Spead Networks building an 825 mile, ‘one signal’ trench between NYC and Chicago or gutting entire NYC apartments, strategically positioned to install heavy duty server farms. All of this effort, labelled as ‘investment’ for the sole purpose of transmitting a deal-closing, revenue building algorithm which can be executed 3 – 5 microseconds faster than all the other competitors.

A subset of this, are purposely designed algorithms which make speedy micro-profits from large volumes of trades, otherwise known as ‘high speed or high frequency traders (HST). Such trading times can be divided into billionths of a second on a mass scale, with the ultimate goal of making trades before any possible awareness from rival systems. Other sets of trading rely on unspeakably complicated mathematical formulas to trade on brief movements in the relationship between security risks. With little to no regulation (as you would expect), the manipulation of stock prices is an already rampant activity.

The Simplex Algorithm, originally developed by George Dantzig in the late 1940s, is widely responsible for solving large scale optimisation problems in big business and (according the optimisation specialist Jacek Gondzio) it runs at “tens, probably hundreds of thousands of calls every minute“. With its origins in multidimensional geometry space, the Simplex’s methodological function arrives at optimal solutions for maximum profit or orienting extensive distribution networks through constraints. It’s a truism in certain circles to suggest that almost all corporate and commerical CPU’s are executing Dantzig’s Simplex algorithm, which determines almost everything from work schedules, food prices, bus timetables and trade shares.