“It is not accidental that at a point in history when hierarchical power and manipulation have reached their most threatening proportions, the very concepts of hierarchy, power and manipulation come into question. The challenge to these concepts comes from a redsicovery of the importance of spontaneity – a rediscovery nourished by ecology, by a heightened conception of self-development, and by a new understanding of the revolutionary process in society.” Murray Bookchin. Post-scarcity and Anarchism (1968).

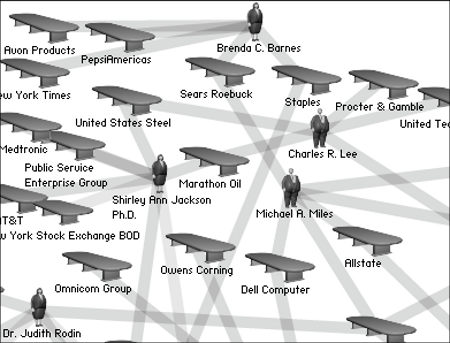

The rise of neo-liberalism as a hegemonic mode of discourse, infiltrates every aspect of our social lives. Its exponential growth has been helped by gate-keepers of top-down orientated alliances; holding key positions of power and considerable wealth and influence. Educational, collective and social institutions have been dismantled, especially community groups and organisations sharing values associated with social needs in the public realm. [1] Bourdieu.

In this networked society, there are controversies and battles taking place all of the time. Battles between corporations, nation states and those who wish to preserve and expand their individual and collective freedoms. Hacktivist Artists work with technology to explore how to develop their critical and imaginative practice in ways that exist beyond traditional frameworks of art establishment and its traditions. This article highlights a small selection of artists and collaborative groups, whose work is linked by an imaginative use of technology in order to critique and intervene into the opressive effects of political and social borders.

In June 2000, Richard Stallman [2] when visiting Korea, illustrated the meaning of the word ‘Hacker’ in a fun way. When at lunch with some GNU [3] fans a waitress placed 6 chopsticks in front of him. Of course he knew they were meant for three people but he found it amusing to find another way to use them. Stallman managed to use three in his right hand and then successfully pick up a piece of food placing it into in his mouth.

“It didn’t become easy—for practical purposes, using two chopsticks is completely superior. But precisely because using three in one hand is hard and ordinarily never thought of, it has “hack value”, as my lunch companions immediately recognized. Playfully doing something difficult, whether useful or not, that is hacking.” [4] Stallman

The word ‘hacker’ has been loosely appropriated and compressed for the sound-bite language of film, tv and newspapers. These commercial outlets hungry for sensational stories have misrepresented hacker culture creating mythic heroes and anti-heroes in order to amaze and shock an unaware, mediated public. Yet, at the same time hackers or ‘crackers’ have exploited this mythology to get their own agendas across. Before these more confusing times, hacking was considered a less dramatic activity. In the 60s and 70s the hacker realm was dominated by computer nerds, professional programmers and hobbyists.

In contrast to what was considered as negative stereotypes of hackers in the media. Steven Levy [5], in 1984 published Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution [6]. In three parts, he writes about the canonical AI hackers of MIT, the hardware hackers who invented the personal computer industry in Silicon Valley, and the third-generation game hackers in the early 1980s. Yet, in this publication, what has had the most impact on hacker culture and is still used widely as a guideline by many is the ‘hacker ethic’. He identified this Hacker Ethic to be a code of practice consisting of key points such as that “all information is free”, and that this information should be used to “change life for the better”.

1. Access to computers—and anything which might teach you something about the way the world works—should be unlimited and total. Always yield to the Hands-on Imperative!

2. All information should be free.

3. Mistrust authority—promote decentralization.

4. Hackers should be judged by their hacking, not bogus criteria such as degrees, age, race or position.

5. You can create art and beauty on a computer.

6. Computers can change your life for the better.

Levy’s hacker ethic promotes the idea of performing a duty for the common good, an analogy to a modern day ‘Robin Hood'[ibid]. Proposing the concept that hackers are self-reliant whilst embracing a ‘healthy’ anti-authoritarian stance, combined with free and critical thinking. Proposing that hackers should be judged by their ability to hack, and presenting hacking as an art-form. Levy also says that the Free and open source software (FOSS) movement is the descendant of the hacker ethic. However, Levy’s hacker ethic has often been quoted out of context and misunderstood as to refer to hacking as ‘breaking’ into computers. This specifically prescribed role, denies the wider and creative context of what hacking is and could be. It does not have to be just about computer security.

This leads us to ‘crackers’. All crackers hack and all hackers hack. But, crackers are seen as second rate wannabe hackers by the older generation of hackers. The Black Hat Hacker or cracker designs and releases malicious code, gathers dangerous information and brings down sensative systems. The White Hat Hacker hunts down and destroys malicious code, and the casual hacker who hacks in order to learn information for his or her own curiosity; both generally dislike ‘Black Hats’ and ‘Crackers’, and tend to view them as computer criminals and dysfunctional juveniles. Lately, crackers have also been labeled as ‘script kiddies’. As a kind of snobbish insult, it refers to those who are not capable of building or programming their own tools, but tend to use scripts and programs written by others to perform their intrusions. To add to the confusion we also have the term ‘Grey hat’. Which refers to a hacker acting between black hat and white hat. Indeed, this could demonstrate where art hacktivists reside, challenging the trappings of the traditional concept of goody and baddy.

“There is another group of people who loudly call themselves hackers, but aren’t. These are people (mainly adolescent males) who get a kick out of breaking into computers and phreaking the phone system. Real hackers call these people ‘crackers’ and want nothing to do with them.” [7] Raymond.

“The basic difference is this: hackers build things, crackers break them.” [ibid] Raymond.

But before we judge,

let’s view a snippet of the \/\The Conscience of a Hacker/\/ by +++The Mentor+++

Written on January 8, 1986.[8]

“This is our world now… the world of the electron and the switch, the

beauty of the baud. We make use of a service already existing without paying

for what could be dirt-cheap if it wasn’t run by profiteering gluttons, and

you call us criminals. We explore… and you call us criminals. We seek

after knowledge… and you call us criminals. We exist without skin color,

without nationality, without religious bias… and you call us criminals.

You build atomic bombs, you wage wars, you murder, cheat, and lie to us

and try to make us believe it’s for our own good, yet we’re the criminals.”

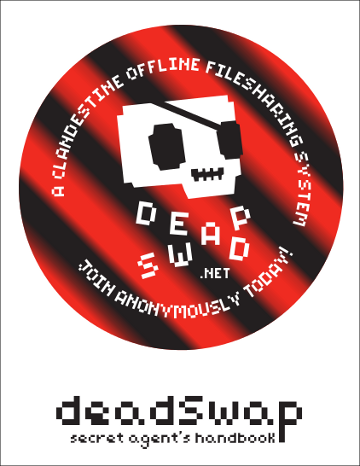

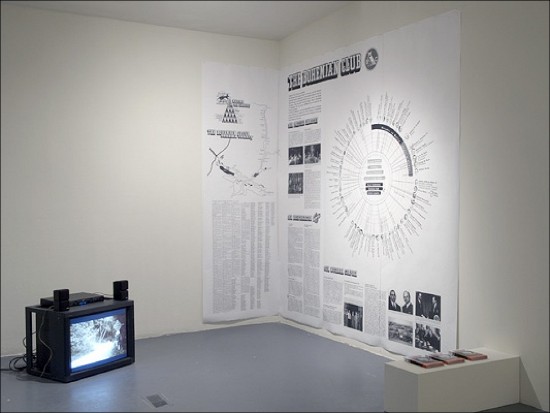

The term ‘Hacktivism’ was officially coined by techno-culture writer Jason Sack in a piece about media artist Shu Lea Cheang published in InfoNation in 1995. Yet, the Cult of the Dead Cow [9] are also acknowledged as defining the term. The Cult of the Dead Cow are a group of hackers and artists. They say the Hacktivism phrase was originally intended to refer to the development and use of technology to foster human rights and the open exchange of information.

Hacktivism techniques include DoS attacks, website defacement, information theft, and virtual sabotage. Famous examples of hacktivism include the recent knocking out of the PlayStation Network, various assistances to countries participating in the Arab Spring, such as attacks on Tunisian and Egyptian government websites, and attacks on Mastercard and Visa after they ceased to process payments to WikiLeaks.

Hacktivism: a policy of hacking, phreaking or creating technology to achieve a political or social goal.

“Hacktivism is a continually evolving and open process; its tactics and methodology are not static. In this sense no one owns hacktivism – it has no prophet, no gospel and no canonized literature. Hacktivism is a rhizomic, open-source phenomenon.” [10] metac0m.

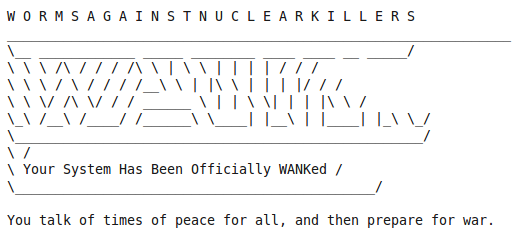

The practice or behaviour of Hacktivism is at least as old as Oct 89 when DOE, HEPNET and SPAN (NASA) connected to (virtual) networked machines world wide. They were penetrated by the anti-nuclear group WANK worm.

WANK penetrated these machines and had their login screens altered to…

HACKING BORDERS: Examples of Art Hacktivism & Cultural Hacking…

“Radical groups are discovering what hackers have always known: Traditional social institutions are more vulnerable in cyberspace than they are in the physical world. And some members of the famously sophomoric hacker underground are becoming motivated by causes other than ego gratification.” [11] Harmon.

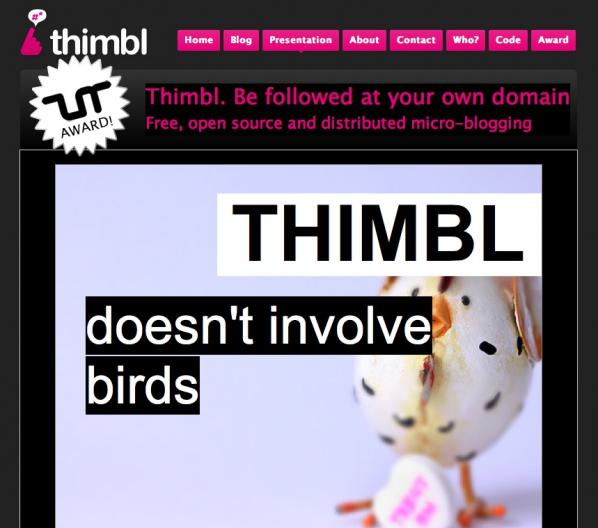

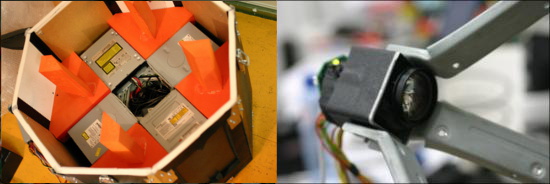

Hacktivism, exploits technology and the Internet, experimenting with the immediacy of distributable networks as a playful medium for independent, creative and free expression. There has been a gradual and natural shift from net art (and net.art) into Hacktivism. Net Art in spirit, has never really been just about art being viewed on a web browser alone. Some of the very same artists whose artwork involved being shown in browsers and making code behind the browser as part of the art, have also expanded their practice outside of the browser. One such artist is Danja Vasiliev, “Fifteen years ago WWW was something very new in Russia and besides the new dial-up aesthetics and world-wide means it brought a complete new layer of existence – “netosphere”, which made my youth.” Vasiliev very soon moved on from playing with browsers into a whole new territory. [12]

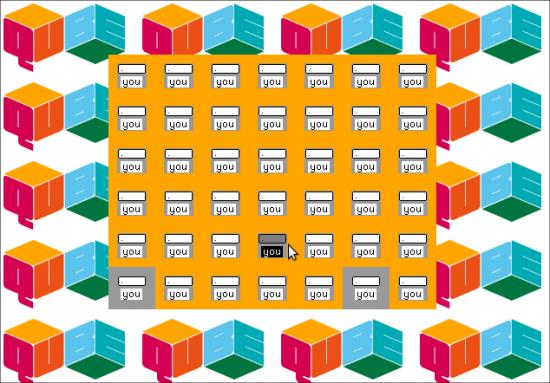

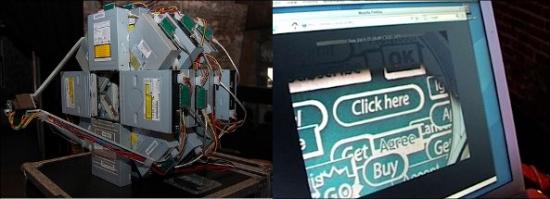

Danja co-founded media-lab moddr_ in 2007, a joint project at Piet Zwart Institute alumni and WORM Foundation. Based in Rotterdam moddr_ is a place for artists and hackers, engaging with critical forms of media-art practice. He collaborated with Gordan Savicic and Walter Langelaar from the moddr.net lab on the project Web 2.0 Suicide Machine, which lets you delete your social networking profiles and kill your virtual friends, and it also deletes your own profile leaving your profile image replaced by a noose.”The idea of the “Web 2.0 Suicide Machine” is to abandon your virtual life — so you can get your actual life back, Gordan Savicic tells NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly. Savicic is the CEO — which he says stands for “chief euthanasia officer” — of SuicideMachine.org.” [13]

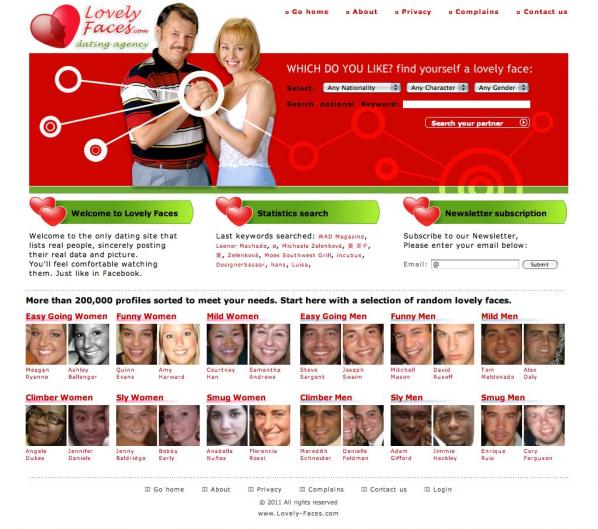

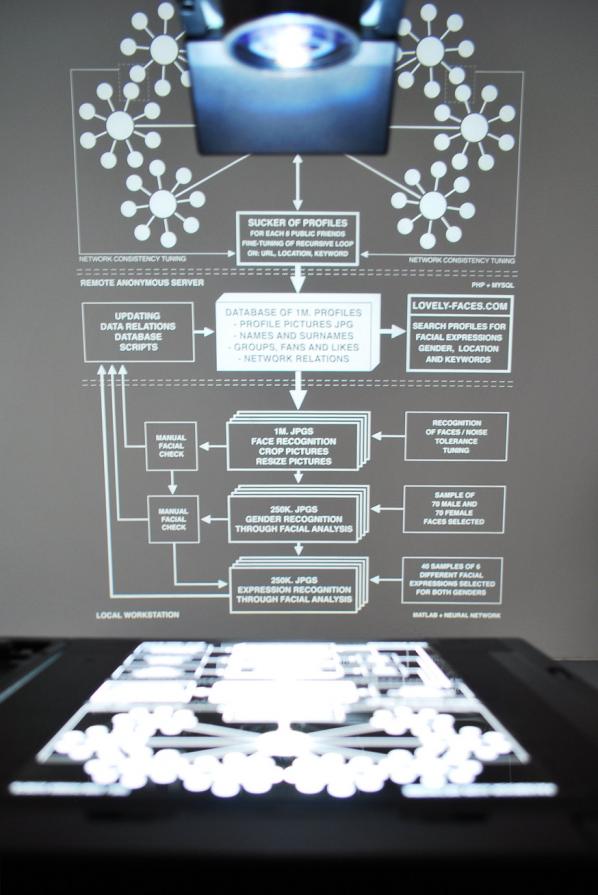

Just like another project called ‘Face to facebook’ that stole 1 million facebook profiles and re-contextualized them on a custom made dating website (lovely-faces.com), set up by Italian artists Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico, whom also just so happens to be editor in chief of Neural magazine. Web 2.0 Suicide Machine, had to close its connections down regarding its Facebook activities after receiving a cease and decease letter from Facebook. [14]

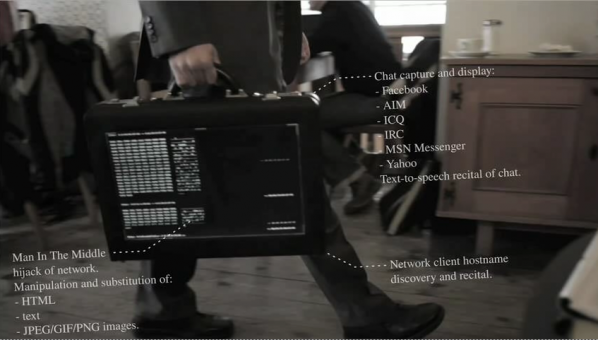

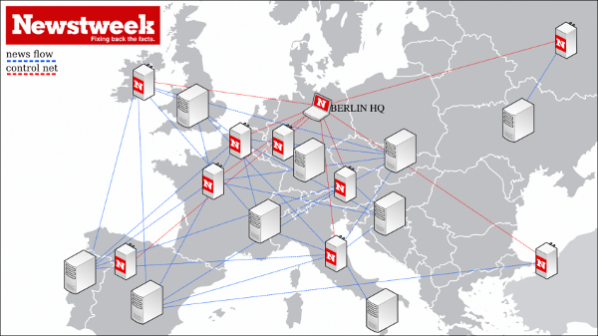

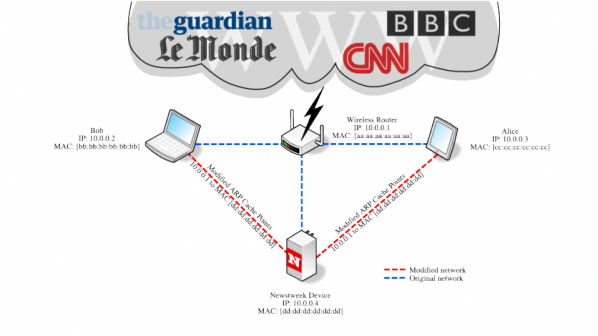

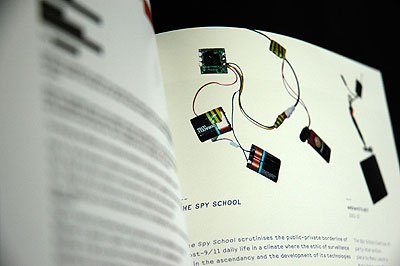

Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev teamed up and formed the mysterious group Men in Grey. The Men In Grey explore our online vulnerabilities by tapping into, intervening into wireless network traffic. Observing, tracing and copying what we do. This hack then redisplays our activities back to us, showing the data of our online interactions.

At first no one (except myself & a few others) knew who they were. When they first arrived on the scene I started an interview with them and then suddenly, I was asked to hold back due to their antics on the Internet and interventions in public environments receiving much coverage. They were not sure how it would pan out for them. Partly due to the anonymous nature of their project, and also because of the sudden impact of the larger hacktivist group Anonymous getting much press in commercial media themselves.

“Men In Grey emerge as a manifestation of Network Anxiety, a fearful apparition in a time of government wiretaps, Facebook spies, Google caches, Internet filters and mandatory ISP logging.” M.I.G

“Spooks are listening into calls, just like they always have,” said Eric King of London’s Privacy International, in an e-mail. “With A5/1 being broken—you can decrypt and listen into 60 calls at once with a box smaller than a laptop.” [15]

Later they won the Golden Nica (1st prize) Interactive Arts category, Prix Ars Electronica in 2011. In a show called Project Space — M.I.G. — Display of unknown, quarantined equipment hosted at the Aksioma Project Space Komenskega, Ljubljana 2011. The statement read:

“The particularly threatening quality of the Men In Grey equipment is its apparently invasive nature; it seems able to penetrate – and even hack into – virtually any electronic device in its reach. While we are all aware of the wire-tapping and data retention done by the government (along with the spying carried out by corporations like Facebook and Google), Men In Grey seem to operate with a range of tools and techniques well beyond those that are currently known to be in use.”

Hacktivism involves many different levels of social intervention and engagement. Whether it is to do with direct action, self-referential geekiness, obscure networked antics, crtical gaming, or peer 2 peer and collective change. Hacktivists challenge defaults put in place by other people, usually the systems imposed upon them and the rest of us by authority. Even though the subjects themselves may be concerning serious matters, humour and playfulness are both essential ingredients.

“A promising tactic for the early Situationists was the unpredictable yet forceful potential of play — what anthropologist Victor Turner termed the “liminoid,” or the freeing and transformational, moments of play when the normal roles and rules of a community or society are relaxed.” [16] Dovey & Kennedy.

One group crossing over from the digital into physical and social realms, is Tiltfactor. [17] Their form of intervention is not necessarily about causing political controversy, but is engaged in reaching people through games of play. Experimenting with social everyday contexts, making games that tackle less traditional topics, such as public health, layoffs, GMO crops. One of the many games creating awareness on these subjects, is POX “Our game actually helps a player understand how a disease can spread from one place to another and how an outbreak might happen” says Mary Flanagan. [18]

A local public health group called Mascoma Valley Health in the New Hampshire region of the US approached Tiltfactor with the problem of the lack of immunization. “At first, a game about getting people immunized seemed like one of the most “un-fun” concepts imaginable. But that sinking feeling of impossibility almost always leads to good ideas later.” [19] Flanagan.

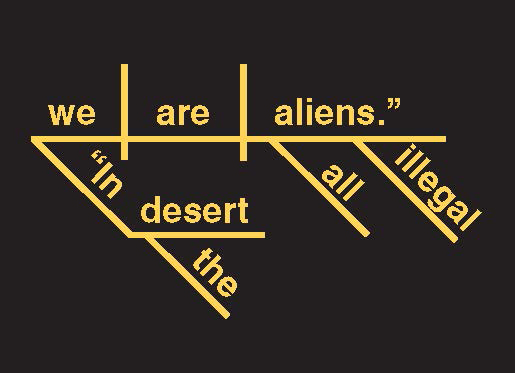

“Geopolitical space has always been a conflicted and fragile topic. Borders and frontiers are changing so fast, that sometimes it seems that our sociopolitical status can change from “citizen” to “immigrant” from one moment to another, or simply live under the “immigrant” status all your life. We’re getting used to words like refugees, enclaves, war, borders, limits –and the list has no end.” Ethel Baraona Pohl & César Reyes

Ricardo Dominguez collaborated with Brett Stalbaum, Micha Cardenas, Amy Sara Carroll & Elle Mehrmand, on (TBT) (and others), on a hand-held mobile phone device that aids crossers of the Mexico-US border. An inexpensive tool to support the finding of water caches left in the Southern California desert by NGO’s for those crossing the border.

“The entire group of artists who are part of Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab working on the Transborder Immigrant Tool (TBT) was being investigated by UCSD and 3 Republican Congressmen starting on January 11, 2010. Then I came under investigation for the virtual sit-in performance (which joined communities statewide against the rising students fees in the UC system and the dismantling of educational support for K–12 across California) against the UC Office of the President (UCOP) on March 4, 2010. This was then followed by an investigation by the FBI Office of Cybercrimes.” [20] Ricardo Dominguez.

In an interview with Lawrence Bird Dominguez discusses that the TBT is still developing as a gps tool, but infers that it is not just a tool but also ‘border disturbance art’, consisting of different nuances existing as part of a whole with other factors at play. Such as a hybrid mix of things, objects and expressions “artivism, tactical poetries, hacktivism(s), new media theater, border disturbance art/technologies, augmented realities, speculative cartographies, queer technologies, transnational feminisms and code, digital Zapatismo, dislocative gps, intergalactic performances, [add your own______].” [ibid]

“Borders are there to be crossed. Their significance becomes obvious only when they are violated – and it says quite a lot about a society’s political and social climate when one sees what kind of border crossing a government tries to prevent.” [21] Florian Schneider

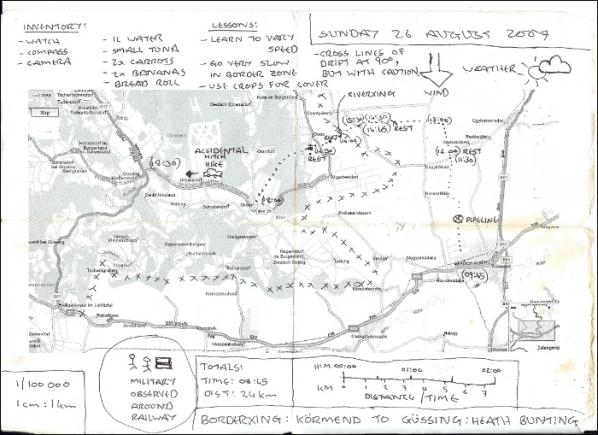

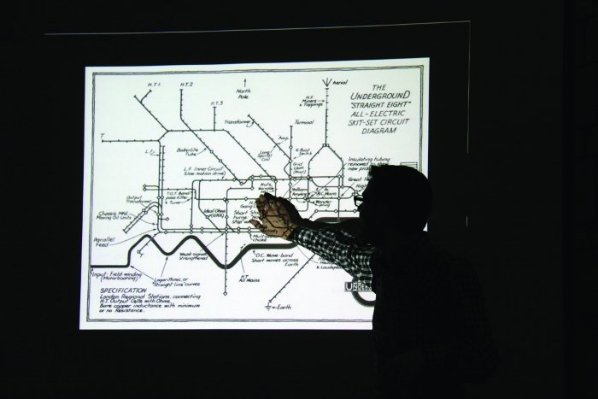

National borders are front-lines of political and social friction. The exerience of asylum-seekers and political migrants reflect some of the most significant issues of our time. Immigration is a toxic issue and unpopular with voters. Bunting’s BorderXing Guide, plays on the fear of invisible alien hordes of people crossing our borders illegally.

The context of this work fits well with issues about borders, whether it is about creating borders online or physical environments. Only those needing to cross a border are allowed access to the site, it is limited to ‘social clients’ who have a static IP (Internet Protocol) address and who, most notably, have gained the artist’s confidence. Such as peer activists and immigrants using libraries, colleges, cultural centres. The site allows those who would other wise end up crossing borders in harmful ways, such as in containers, on the backs of (and underneath) lorries and planes.

Heath Bunting’s BorderXing Guide website primarily consists of documentation of walks that traverse national boundaries, without interruption from customs, immigration, or border police. The work comments on the way in which movement between borders is restricted by governments and associated bureaucracies. It is a manual written not at distance like a google map, but by foot. A physical investigation, involving actually going to these places; trying these discovered routes out and then sharing them with others. A carefully calculated politics of public relations.

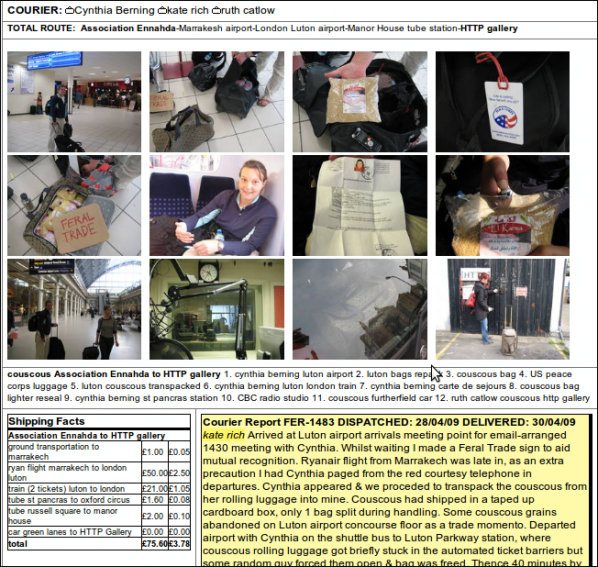

“The Feral Trade Café is more than just an art space that’s a working café, it’s about provoking people to question the way big food corporations operate by looking at the journey of the food we end up scraping into our pampered bins.” [22] Gastrogeek

Feral Trade uses social and cultural hand baggage to transport food based items between cities, often using other artists and curators as mules. Feral Trade products (2003-present), alongside ingredient route maps, bespoke food packaging, video and other artefacts from the Feral Trade network. The goods rangefrom coffee from El Salvador, hot chocolate from Mexico and sweets from Montenegro, as well as locally sourced bread, vegetables and herbs.

Kate Rich uses the word ‘feral’ as a process refering to being deliberately wild, as in pigeon, as opposed to romantic nature wild as the wolf. It is an unruly wild, shitting everywhere, disruption and annoyance in contrast to ‘official’ human structures and connected infrastructures. Feral Trade freight operates largely outside commercial channels, using the surplus potential of social, cultural and data networks for the distribution of goods. Working with co-operatives, small growers and food producers.

The Feral Trade Courier is a live shipping database for a freight network running outside commercial systems. The database offers dedicated tracking of feral trade products in circulation, archives every shipment and generates freight documents on the fly.

Every shipment is different and has its own story of how and where it was delivered from. Also included is information on who the carriers are with details about producers and their local culture as contextual information. The product packaging itself is also a carrier of information about social, political context and discussions with producers and carriers.

![Feral Trade at Furtherfield's Gallery (2009) [23] Link to exhibition](http://www.furtherfield.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/3657297700_42b1c26014_b.jpg)

Since the rise of the Internet individual and collective actions are symbiotically connected to the every day. In a world transformed, common people have access to tools that can change ‘our’ cultures independently; sharing information, motivating actions and changing situations. We know of the Arab Spring, the Occupy movement, Anonymous and Wikileaks and how successful they have been in exploiting technology and social networks. Technology just like any other medium is a flexible material. By tweaking, breaking and remaking ‘something’ you can re-root it’s function, change its purpose.

The links between these mass social movements and the artists here are not just relating to technology’s use but, a shared critique at the same enemy, neo-liberalism.

“”Neo-liberalism” is a set of economic policies that have become widespread during the last 25 years or so. Although the word is rarely heard in the United States, you can clearly see the effects of neo-liberalism here as the rich grow richer and the poor grow poorer.” [24] Martinez & Garcia.

At the same time as highlighting the continual privatization of human society. This form of art practice shows us the cracks of where a social divide of gate-keeping has maintained power within the Western World’s, traditional art structures. We now realize that the art canons we have been taught to rely on as reference are more based around privelage, centralization and market dominance rather than democratic representation or even just pure talent. Hacktivist artists adapt and recontextualize with a critical approach, towards a larger and more inclusive context beyond their own immediate selves. Demonstrating a respect and use of autonomy, and an awareness of social contexts and political nuances, freeing up dialogue for new discussions which include a recognition of social contexts, as a vital ingredient and valued resource in art. Re-aligning, reconfiguring the defaults of what art is today.

Lies, Lawlessness and Disbelief 1. Thinking Art and Capital: Conceptual Capitalism and Risk Management, is the first of five essays by Canadian artist & critical thinker, Katie McCain. McCain discusses how capitalism has become on the one hand all encompassing and on the other utterly unreal. Arguing that we need to be prepared to think the impossible so that resistance is able to grow.

DOWNLOAD the full text (including all 5 parts) here.

An Attempt at Thinking Art and Capital: Conceptual Capitalism and Risk Management

this sentence is a lie[1]

Capitalism is no longer the simple fordist system of production and consumption. It has, in its post-fordist lifetime become a more and more complex and intangible form. Today, it is a conceptual capitalism that has become unmoored, free floating, and all encompassing. As it continues, capital has the amazing ability to subsume everything it encounters, including criticism and resistance.[2] This proliferation seems to leave little room to resist – there is no longer a way to step outside and critique, since the death/failure of really existing socialism,[3] but this means only that critique must come from within, which is no small feat. It is a method riddled with paradox and self-defeat, but this perhaps reflects the nature of capital itself – as a system it offers up many moments of fissure or collapse that can be manipulated. The vastness of capitalism and the complexity of the bureaucracy necessary to hold together a system of “order” that directly contradicts chaos theory inevitably begins to circle and break down. It is these moments of circuity, of fissure, that this essay will focus on.

Contemporary capitalism is conceptual capitalism – it runs on the idea of money in the form of loans, mortgages, hedge funds, junk bonds; it is fictional money and a fictional market based on an elaborate system of risk management, which implies some intrinsic (but impossible) knowledge of the future. It also seems that this fictional market can be bolstered by belief alone. ‘The financial crisis of 2008 showed enormous sums of money spent not on a real, concrete problem, but rather to restore belief in the market. Capital, in all its intangible forms, is the Real of our lives’.[4]

If what Žižek states is true, and capitalism can be equated with Lacanian theory of the Real[5], it again seems to close down access to it further still. It is opposed to reality, which encompasses the Imaginary and the Symbolic and it is located beyond them, out of reach, but exerting influence. It is undifferentiated, without fissure, always in its place.[6] It is impossible to imagine, to verbalize, to integrate in the Symbolic order. But perhaps this impossibility is the moment, the fissure, which can bring about its demise.

The signification of the Real is attempted in the Symbolic order, but is impossible. The Symbolic structures everything, and through repetition is subject to the death drive. That is, in its constant return to enjoyment the Symbolic transcends beyond pleasure in search of death. This could be seen as some radical call to accelerationism, a desire to weaponize capitalism against itself, and in a way it is, but not in the apocalyptic sense that accelerationism implies, pushing it to its extreme.[7] Rather, a radicalism could exist in simply exploiting these impossibilities, finding weak points in rationality, and the supposed rationality of capitalist systems, in its inherent bureaucracy.

This Symbolic capitalism is contingent in regards to the Real; it does not spring from it[8], but is created out of a desire to verbalize the impossible, to understand something that is impossible to understand, to socialize this intangible system. It could be said that it is impossible to speculate on the origins of the Symbolic once it is in place, generated as it is from a primal prohibition, a negation, le-nom-(non)-du-pere[9]; once capitalism is in place, it becomes impossible to see an alternative to the universe it creates.[10] This is mostly due to the all-encompassing nature of conceptual capitalism. Perhaps then, the ability to catch it in a paradox, in a state of bureaucratic failure, could open up a space to trip it up and think other and could offer a passage a l’acte.

other other other say it three times in the mirror

Employing the idea of a contingent conceptual capitalism, that is, one which is not necessary, which is indifferent to existence, one can argue that in fact it is very possible to think of the other to capitalism. It is logic and rationality that trips it up, that prevents any thought of the alternative, just as it is strictly impossible to think infinity, or an ancestral time prior to human existence. Science can prove facts about both ancestral time and descendant time (prior to and after the death of consciousness), but philosophy is paradoxically stuck with the idea of a relation to the world before or after the existence of thought[11]. How can thought think the death of thought?[12] According to Hakim Bey it is impossible to really conceive of death – it appears rather as ‘an unpleasant vagueness’[13] – the death considered is never actual death. Similarly, how can one think anti-capital from within conceptual capitalism? If it is permitted that both the universe and capitalism are contingent, and therefore completely indifferent to human existence and human thought, then the possibility for alternatives opens up.

A speculative and realistic approach to thinking capital can restore our ability to resist.

Once it is granted that the tension between equality and liberty cannot be reconciled and that there can only be contingent hegemonic forms of stabilization of their conflict, it becomes clear that, once the very idea of an alternative to the existing configuration of power disappears, what disappears also is the very possibility of a legitimate form of expression for the resistances against the dominant power relations.[14]

If conceptual capitalism encompasses everything, there is less and less physical space for resistance, unless resistance moves into the conceptual realm as well. The idea, the imaginary, the psychical: these all offer a variety of forms of resistance to a boundless capital. For the concept, in its true dematerialized form, is capable of altering systems, of bolstering illogic, of predicting the future. It is the very boundaries of thought, beyond which lies psychosis (the lack of the Symbolic, or capital) that prove to be integral in terms of non-knowledge and the unknown, a knowledge of the unknown, or a thinking of the impossible. Perhaps lies, fiction and the radical un-real can be the site of production for a capitalist alternative.

Ideas are characterized as both distinct and obscure. They are distinct insofar as they are perfectly differentiated via the reciprocal determination of relations and the complete determination of points – but obscure because they are not yet differenciated – since all Ideas coexist with one another in a state of virtual perplication.[15]

Ideas are simultaneously two things, distinct and obscure. Graham Harman introduces the idea as something not only possible, but actual insofar as an idea is thought as an image. This introduces all things possible to the realm of the actual, even if only in thought.[16]

The contemporary mantra of risk management as a fundamental economic strategy is in itself paradoxical. If, in fact, a risk could be managed, then it would not really be considered a risk. This term depends on the belief in an organized system of capitalism that extends both directions through time – the idea that it is a constant that can be depended upon, is predictable, forever. In fact, the amount of bureaucracy that goes into even the tiniest element of conceptual capitalism manifests itself through many circular moments, many points of fissure. In compatibility with Gödel’s Theorem of incompleteness, no system can be totally defined without incurring some kind of paradox. There will always be statements that are true, but that cannot be proved within the system. If the system is capable of proving certain basic facts, then one particular truth the system cannot prove is the consistency of the system itself.[17]

Risk management is nothing more than a reaffirmation of our collective belief in the predictive qualities of financialization, our collective consent to the idea that an intangible, unmoored, all-encompassing economic system can be predicted. In fact, prediction alone is a falsity that humans fall prey to frequently; the notion of the future as anything other than a continuation of the past is a mental operation at which the mind continues to fail. When thinking of tomorrow, the mind just projects another yesterday.[18] The future, or rather a human relation to the future, is deemed philosophically impossible. After all, how can consciousness think something devoid of consciousness?[19]

It is impossible for thought to think an object or event in-itself – in this sense, thought can only experience a relation between the subject and the object-as-given. Lacan argues in his fifth discourse that we do not derive libidinal enjoyment from object relations, but rather it is capital’s link of subject-to-object that frustrates and isolates the subject. Capitalism is successful in the sense that it produces a continual desire, but no longer satisfies it, which for Lacan – and a world full of neurotics – falls in line with our drives.[20]

Lacan also reorients Marx’s analysis of surplus value. An older, more tangible form of capitalism sold objects for more than it cost to make them. This ‘surplus value’ is what Marx stated that the capitalists stole from the proletariats – it was used by the capitalists for leisure or libidinal enjoyment. Now, capital demands this surplus value to be re-invested at the level of production to create an unrelenting, perpetual motion machine of production and consumption of money by a business in-itself. We are now, according to Lacan, all proletariats, subject to the will of capital that has taken over the role of master from the capitalists themselves.[21]

The debt circulates on its own orbit, with its own trajectory made up of capital, which, from now on, is free of any economic contingency and moves about in a parallel universe (the acceleration of capital has exonerated money of its involvements with the everyday universe of production, value and utility). It is not even an orbital universe: it is rather ex-orbital, ex- centered, ex-centric, with only a very faint probability that, one day, it might rejoin ours.[22]

This faint probability is the only thing tying us to capital.

Adorno, Theodor.W. Negative Dialectics. Translated by E.B. Ashton. New York: Continuum, 2005. First Published 1966 by Suhrkamp Verlag.

Associated Press. “Romanian Witches Curse Latest Government Clampdown,” The Guardian, February 9, 2011, main section, 20.

Bartlett, Monica Y., Aida Cajdric, Nilanjana Dasgupta and David DeSteno, “Prejudice from Thin Air: The Effect of Emotion on Automatic Intergroup Attitudes.” Psychological Science 15, no. 5 (May, 2004): 319-324.

Baudrillard, Jean. Global Debt and Parallel Universe. Translated by Francois Debrix. http://www.egs.edu/faculty/jean-baudrillard/articles/global-debt-and-parallel-universe/ (accessed April 4, 2011).

Baudrillard, Jean. Radical Thought. Translated by Francois Debrix. Edited by Sens & Tonka. Paris: Collection Morsure, 1994.

Bey, Hakim. T.A.Z.: Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. New York: Autonomedia, 2003. First Published 1985.

Bradley, Will. “Guarana Power.” in Self-Organization/Counter-Economic-Strategies, edited by Bradley, Hannula, Ricupero and Superflex, 311 – 333. New York: Steinberg Press, 2006.

Brassier, Ray. “I Am a Nihilist because I Still Believe in Truth” Interview with Marcin Rychter. Kronos: March 4, 2011 http://kronos.org.pl/index.php?23151,896 – accessed: march 23rd, 2011.

Brassier, Ray. Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction. Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan, 2007.

Critical Art Ensemble. Marching Plague: Germ Warfare and Global Public Health. New York: Autonomedia, 2006.

Declercq, Frédéric. Lacan on the Capitalist Discourse: Its Consequences for Libidinal Enjoyment and Social Bonds. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society 2006, 11, (74-83).

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books, 2009.

Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews & Other Writings: 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

Fromm, Erich. The Fear of Freedom. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1966.

Groys, Boris “Art and Money,” E-Flux 24 (2011), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/view/226.

Harman, Graham. Circus Philosophicus. Winchester: Zero Books, 2010.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1979.

Holt, Jim. “The Way We Live Now: Against Happiness,” New York Times, June 20, 2004.

Horizon: What is Reality? Documentary. Directed by Helen Shariatmadari. BBC: ep. 9, 2011.

Huberman, Anthony, ed. For the Blind Man in the Dark Room Looking for the Black Cat that Isn’t There. St. Louis: Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, 2009.

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. London: Vintage Books, 2007. First published 1932 by Chatto & Windus.

K-Punk Blog. http://k-punk.abstractdynamics.org/archives/004421.html

Kafka, Franz. The Castle. Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd., 1964. First published 1926 by Das Schloss.

Kurant, Agnieszka and Nassim Nicholas Taleb. “Unknown Unknowns: A Conversation between Agnieska Kurant & Nassim Nicholas Taleb about the Benefits of Uncertainty.” Frieze, September 2010, 127 -135.

Lacan, Jacques. “Seminar on the Purloined Letter.” Yale French Studies 48 (1972): 39-72.

Lacan, Jacques. The seminars of Jacques Lacan: Book II: The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis 1954-1955. Ed: Jacques-Alain Miller. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1991.

MacKinnon, Catharine A. “Feminism, Marxism, Method and the State.” Chicago Journals 8, no. 4 (1983), 635-658.

Meillassoux, Quentin. After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency. London: Continuum, 2008.

Mouffe, Chantal. The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso, 2000.

Noys, Ben. Persistence of the Negative: A Critique of Contemporary Continental Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010.

Place, Vanessa and Robert Fitterman. Notes on Conceptualisms. New York: The Ugly Duckling Presse, 2009.

Stephen, Kylie. “Sexualized Bodies.” in Real Bodies: A Sociological Introduction, edited by Evans and Lee, 29-45. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. 2002.

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. London: Penguin Books Ltd., 2007.

Thacker, Eugene. “Nihil Unbound” review of Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction, by Ray Brassier, Leonardo 42: no.5, (2009): 459-460, http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/leonardo/v042/42.5.thacker.html (Accessed April 2, 2011).

The Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom? Documentary. Directed by Adam Curtis. BBC Two: March 2007.

Trotta, Roberto. “Dark Matter: Probing the Arche Fossil.” Interview with Robin Mackay. Collapse: Philosophical Research and Development 2 (2007): 83-169.

Vidal, John. “Bolivia Enshrines Natural World’s Rights with Equal Status for Mother Earth.” The Guardian. April 11, 2011. Main section, 15.

Weaver, Matthew. “Romanian Witches to Cast Anti-Government Spell.” The Guardian. January 7, 2011. Main section, 23.

Wilson, Eric G. Against Happiness. New York: Sarah Critchton Books, 2008.

Žižek, Slavoj. First as Tragedy, Then as Farce. London: Verso, 2009.

Žižek , Slavoj. The Iraqi Borrowed Kettle. http://www.lacan.com/zizekkettle.htm (accessed April 4, 2011).

Žižek, Slavoj. What Rumsfeld Doesn’t Know that He Knows About Abu Ghraib. (2004) http://www.lacan.com/zizekrumsfeld.htm (accessed April 4, 2011).

Featured image: Martijn de Waal, co-founder of The Mobile City, introduces the conference (image courtesy Virtueel Platform)

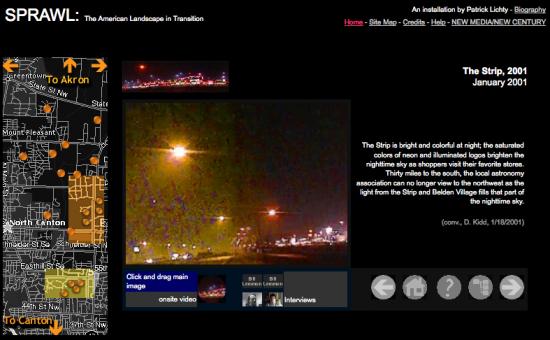

On Feb. 17th Amsterdam hosted Social Cities of Tomorrow, a conference on new media and urbanism. Adapting its title from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow, but taking equal inspiration from the work of Archigram, the conference presented a snapshot of the direction cities are moving today: as conventional means of planning and designing are renegotiated through our engagement with new media technologies:

Organized by The Mobile City and Virtueel Platform, the event showcased best-practise examples of the use of media in urban analysis, design, art and activism. These ranged from “Homeless SMS”, a text-messaging system designed to provide information to the 70% of homeless Londoners who own cell phones; “Amsterdam Wastelands”, an on-line mapping of disused sites in Amsterdam and Zaanstad; “Koppelkiek”, a game project in which residents of a troubled area of Utrecht collected “couple snapshots” (in couples of friends, relatives or complete strangers), promoting social interaction through play; and “Urbanflow”, and New York-based project to rethink the contents of urban screens. In all, a dozen such projects were presented at the conference.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/showcases

Immediately preceding the conference an intensive three-day workshop took place at ARCAM, the Amsterdam Centre for Architecture. This event brought together two dozen interdisciplinary creatives from around the world to tackle urban issues in four current case-studies: Haagse Havens, Den Haag; Zeeburgereiland; Strijp-S Eindhoven; and the Amsterdam Civic Innovator Network (a proposal to open up Amsterdam’s civic resources to distributed control by citizens). Working with local stakeholder organizations, the participants brainstormed how to leverage new media to solve intractable or new problems in these real-world sites.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/workshop/the-four-cases

Also at ARCAM, a roundtable discussion on the alternative forms of trust emerging out of new media conditions was held, with panelists (below, left to right) Tim Vermeulen, Henry Mentink, Rietveld Landscape, Scott Burnham, Michiel de Lange (image courtesy Aurelie).

Keynote speakers Usman Haque, Natalie Jeremijenko, and Dan Hill concluded the conference with a panel discussion that placed the presentations in the context of distributed technology, contemporary art, social innovation, and architecture (image courtesy Virtueel Platform).

Taina Bucher interviews curator Gaia Tedone about her latest online curatorial project called ‘Is Seeing Believing?’ as part of the TRUTH programme at or-bits.com, an online platform for the display of contemporary arts and production of new works. Born in Italy, in 1982 Gaia Tedone holds an MFA in Curating from Goldsmiths, and has for the past year been one of the curatorial fellows at the Whitney Independent Study Program, New York. She has been involved in a number of art projects and worked with institutions such as Whitechapel Gallery, James Taylor Gallery, The David Roberts Art Foundation and Tate Modern.

Taina Bucher: Tell me a bit about your background for doing curatorial work. How did it get started and what are some of the thematic interests that have been important to your work?

Gaia Tedone: I started doing curatorial projects in London, where I was living and working for the past five years. The time spent at Goldsmiths was extremely formative from a practical and intellectual point of view. I was involved in a number of projects – some of them in collaboration with institutions in London, such as the series of talks Curating Fictions organised at Whitechapel Gallery, others were developed within the academic context, as for instance IM magazine and the publication A Fine Red Line (A Curatorial Miscellany) which I edited with fellow curators Isobel Harbison, Ilaria Gianni, Nazli Gürlek, Rosa Lleo and Yannis Arvanitis. The latter experience led us to establish the curatorial collective IM projects – a platform for editorial projects for which I contributed for the following two years.

The MFA in Curating at Goldsmiths and the Whitney Independent Study Program have both helped me to locate my interest in the history of art production within today’s global context and to look at the ways in which specific economic and political contexts shape the production and circulation of art. These two complementary programmes of study informed my research interests, which are located at the intersection between the fields of new media and cultural studies.

This year, within the context of the Whitney Program, I was exposed to a number of seminal authors and texts that since the 70s have contributed to the development of the field of cultural studies, and I was deeply inspired by the recent work of David Harvey and the political philosopher Chantal Mouffe. This intense year of research has informed the conception and realization of the exhibition Foreclosed. Between Crisis and Possibility that I co-curated with ISP fellows Jennifer Burris, Sofía Olascoaga, and Sadia Shirazi at The Kitchen in New York.

The exhibition, which included works by Kamal Aljafari, Yto Barrada, Tania Bruguera, Claude Closky, Harun Farocki, Allan Sekula and David Shrigley, took the current housing crisis in the U.S. as the departing point to explore other meanings of the word foreclosure, which also evokes processes of exclusion and a shutting down of recognition.

Taina Bucher: How did you get into doing online curatorial work?

Gaia Tedone: I was invited few months ago by Marialaura Ghidini to collaborate with her and Christine Takengny on the autumn issue of or-bits.com. Marialaura had some preliminary thoughts on how she wanted to develop the programme, and after few Skype meetings we established a common ground upon which we built three parallels projects. The programme curated by Marialaura was launched in early October with works by Angus Braithwaite/David Raymond Conroy/Adelita Husni-Bey/Iocose/ M+M (Marc Weis and Martin De Mattia)/Richard Sides and my response followed shortly after that. Is Seeing Believing? is my first curatorial work online.

Taina Bucher: How do you feel about exhibiting art online, what are the challenges and benefits? In what ways does the conceptual work with developing a project online differ from curating exhibitions in a more offline institutionalized setting?

Gaia Tedone: or-bits.com provided me with technical support in terms of coding and web-design, while I was left totally free to develop my own curatorial strategy. My original idea was to build up a True or False web-based questionnaire, mainly text-based. However, the project developed in a slightly different direction and I was happy to adapt its format to the eclectic contributions I was receiving. Once I gathered all the content, I chose to mimic the format of an online newspaper, as this seemed the best visual strategy to actually play with the ideas being put forth while maintaining an inner coherence for each artist’s contribution.

I found the context of the web extremely challenging from a curatorial perspective, as it required the ability to work simultaneously on different elements, from the editing of content to the formalization of a coherent visual output, employing an approach both flexible and rigorous. It felt like a condensed version of a ‘traditional’ show, yet faster in pace and with a different degree of curatorial control. It came together fairly organically. The Web I think poses a number of important questions, especially in relation to the short attention span we generally dedicate to what we read or look at when surfing the net. Would the type of art being produced have to play or interject whit this? How would it change the public’s experience or engagement? These are all open questions for me.

Taina Bucher: What is the idea behind your current exhibition on or-bits?

Gaia Tedone: The theme TRUTH developed out of several conversations inspired from Žižek’s text Good Manners in the age of Wikileaks and a shared interest in somehow questioning the democratic claim of the web as a space of freedom, in light of the recent developments of Wikileaks and of the role that social media played during the Arab Spring. In a world in which everyone can be the author of his/her own news, how do we assess what is true or false? And how is this shifting power’s relationships and individual agency?

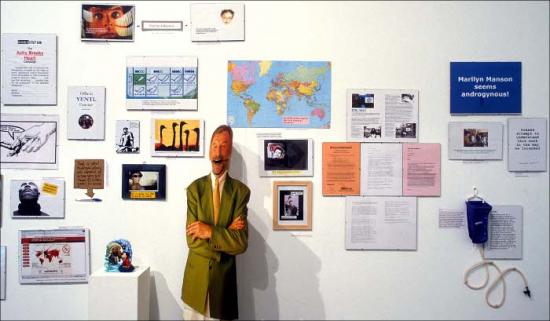

Within this larger framework, the project Is Seeing Believing? specifically focuses on the relationship between image and belief and develops from the engagement with two particular images: first, the image of Caravaggio’s iconic painting The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1601-1603), depicting Apostle Saint Thomas’ unwillingness to believe without direct, physical and personal evidence in Jesus Christ’s Resurrection. Second, the image published in the news showing President Obama, Hilary Clinton, Joe Biden, along with members of the national security team, watching Bin Laden’s death live.

The latter image, which quickly became one of the most publicly viewed in occasion of Bin Laden’s death, claims to present a less crude version of the story, but in fact it does not. On the contrary, it carries the absence of the image we are actually looking for – the one of Osama Bin Laden’s death body – affecting the viewer on multiple levels. On the one hand, by making the relationship between political power and media control even more visible; on the other, by acknowledging the necessity to see an image in order to believe in a fact. Then again, to what extent does it really matter if what we are looking at is the actual event or other people witnessing it? Has seeing become believing? These are some of the questions and preoccupations that have animated the conception and realization of this online project.

Taina Bucher: ‘Is Seeing Believing?’ is an exhibition displayed in the format of a newspaper. Who are the contributing artists?

Gaia Tedone: I began by approaching a number of artists, designers and activists whose work I admire and who, in my opinion, share a highly critical approach towards the production and reception of images and often employ a strategic use of the media in their practices. Some of the contributors, like for instance Jon Rafman, Nate Harrison, Alterazioni Video, The International Errorist and Foundand, have used the web extensively as the source and context of their works, others as for instance Azin Feizabadi and Oliver Ressler & Martin Krenn brought to the project their experiences of artists working within specific public spaces. A couple of interventions, such as the ones of MDR, Sadia Shirazi and Alessandro Sambini were specially conceptualised and produced for or-bits.com.

The idea of assembling them within the format of an online newspaper came at a later point, once all the material was gathered. It also pays homage to The New York Times Special Edition produced by The Yes Men and Steve Lambert and distributed for free in the streets of New York City in 2008. The paper announced the end of the Iraq’s war and changes in the US government’s policies on global warming, embracing for one day the philosophy of ‘All the News We Hope to Print’, at the beginning of President Obama’s administration.

The choice to play out specifically with Al Jazeera’s website was driven by the visual intelligibility of its design and by the desire to locate the project’s investigation within the context of this year political events and the role that social media played within the Arab Spring. As Sadia Shirazi interestingly points out in her contribution about Wikileaks as a socially engaged practice, if information is the terrain of war, what better context than a newspaper to put forth such urgent questions?

Taina Bucher: It is interesting that you say your or-bits contribution seeks to challenge the debate on image and truth by embracing the visual volatility of the web. Yet your newspaper is surprisingly static to be a webpage. Was this a conscious choice?

Gaia Tedone: This is a pointed observation. The webpage attempts to create a visual cohesiveness to the project, but it also asks the viewer to be actively engaged with the navigation.

I would see it as an attempt to fix in time the volatility of the web, maintaining in its content the associative and eclectic character of a browsing session, yet proposing a specific vantage point. In a sense it is like an exhibition, in which the works are in dialogue with each other, but have their own space and are framed by the specificity of the context.

Taina Bucher: Your project seems to suggest that we have no choice but to believe the image. Why is that? Haven’t we by now learned to be critical of the image, of its truthfulness and representability? Just think of Judith Butler’s book Frames of War where she addresses the dramaturgy of the Abu Ghraib photos. Susan Sontag already argued in 1977 that visual representation had become a cliché, that we are constantly bombarded with sensationalist images that numb our sense of believing. In what ways do you think, then, that the explosion of images online has somehow led to a diminished capacity to be critical?

Gaia Tedone: What interests me is the relationship between the access to images and the mechanisms of power that regulate this access and how this relationship is becoming more sophisticated and problematic within the context of the web and the role that social media play in the diffusion of images and information.

I think that a critical approach towards the reception of images is a condition that needs to shift and constantly adapt itself to the development of the image’s status itself. It cannot be separated from the historical and technological context in which images are produced and cannot be considered resolved as such, as the social and political configuration of the world is shifting also through the news and the images accompanying them.

Through the question Is Seeing Believing? I wanted to direct attention to the individual agency and the possibility for artists to filter, edit and rearrange the information and images they are exposed to, in this way challenging the notion of truth. To quote Siegfried Kracauer, who is also mentioned in the project, and his famous collection of essays ‘The Mass Ornament’ published in 1963: Never before has an age been so informed about itself, if being informed means having an image of objects that resembles them in a photographic sense. Never before has a period known so little about itself. In the hands of the ruling society, the invention of illustrated magazines is one of the most powerful means of organizing a strike against understanding.

These words still resonate powerfully with me, as they crucially point out to the ambiguous relationship between photography and information. Although there is a risk involved in believing in the image – risk that we must be aware of – what happens when the access to the image is negated to us? When this process of identification, compassion and repulsion that images often instigate is no longer accessible? Do we stop believing in reality or do we start to understand it?

President Obama’s decision not to diffuse the image of Osama Bin Laden’s body marks, in my opinion, a very important moment in the history of the images of the last decade.

It counterbalances with its absence 9/11, one of the most photographically reproduced events of this century – the day in which history and fiction met in the brutal instant of a photographic frame. I see this absent image as an occasion to stop, look back and critically reflect on what happened

Since the turn of the millennium, there have been shifts toward new forms of sociopolitical dissent. These include strategies such as cellular forms or resistance including asymmetrical warfare like global insurgencies, the use of social media. Examples would be Twitter and Facebook in their ability to lens dissent for actions in Syria, Egypt and Tunisia, Wikileaks and its ability to mirror, and politics that use anarchistic forms of collective action such as the Occupy Movement. Although my focus is more concerned with the Occupy Movement, what is evident is what I call an amorphous politics of dissent. Amorphous is defined as “without shape”, and can be applied to most of the mise en scenes listed above.

The dissonance of power in regards to conventional politics can be seen in its structure. For example, the nation-state has a tiered, hierarchical structure of power relations. There is a President or Prime Minister, a legislative organ of MPs or Representatives, Parliaments, Houses, and the like, a Judicial organ, and a Military organ that includes any number of militia and police. Although I am referring mostly Western forms of government, we can also argue for the hierarchical form in terms of the Corporation, with its CEO, Board, Shareholders, Managers, and Workers. This can be expanded historically to Feudal lords with their retinue of Vassals, Nobles and Warlords with their coteries of Warriors and support personnel. The point is that conventional power typically operates in a pyramidal command and control hierarchy with a centralized Leader at the “capstone”. One can argue that the pyramid may have different shapes, or angles of distribution of power, but in the end, there is usually a terminal figure of authority. To put it in terms of stereotypical Science Fiction terminology, when the alien comes to Earth, the standard story is that it pops out of the spacecraft and says, “Take me to your leader.” This signifies the hegemonic paradigm of Leadership as the central gestalt of First world power. Leadership, then, is the conventional paradigm of power in Western culture, and dominates the industrialized world.

Territorialization refers to the exertion of power along perimeters, or borders. Functionaries expressing the constriction of territory include customs agents, and border patrols; but are terminally expressed by the military wing of the nation state. This military is also generally pyramidally constructed in terms of Generals, Colonels, and other officers leading Battalions, Regiments and Divisions, which are organized as defenders of a nation’s sovereignty. These military organs are conversely best optimized to exert their power against either parallel or subordinate structures. Parallel structures include the armies of other nations, their Officers, et al, and their troops and ordnance that possess a similar organization. Conversely, subordinate structures over which military powers can exert power over are domestic masses that can be overrun with overwhelming power, although these forces are more specialized (such as National Guards or Gendarmeries). In the conventional sense, power is expressed orthogonally, whether it is against equal or subordinate forces.

Another aspect of this conversation relates to the expression of power/force through conflict and violence, but has its inconsistencies The examples I will use from American pop culture I will use in this missive to explain amorphous action may be violent in nature, but the violent nature of these examples do not relate to the paradigmatic jamming of conventional power. Their citation is related more to the fact of conventional power’s orthogony, or parallelism of exertion of power to similar structures or dominance of the subordinate, and the panic state it experiences when confronted with non-conventional difference or passive resistance. We could express the power relationships between amorphous politics and conventional power in terms of a tetrad in terms of examples of violent and peaceful exertion of amorphous dissent as well as orthogonal conflict. We could cite the Occupy movement as a site of passive, and the Tunisian uprising as violent exemplars of amorphous conflict or dissent. Conversely, the Gandhi/King is a non-violent model of as orthogonal/hierarchical/led action, and World War Two as conventional orthogonal conflict. What is important here is the inability of the conventional politics and power to cope with leaderless, non-hierarchical, non-orthogonal discourse that refuses to talk in like terms such as centralization, leadership and conventional negotiations that include concepts such as “demands”. This is where the site of cognitive dissonance erupts, often resulting in a panic state or in the “figureheading” of dispersed networks of power.

The need for the traditional power structure to focus identity on the antagonist in terms of figureheads is evident in the Middle East and Eurasia in the personification of terrorist and insurgent networks, but is more simply illustrated in the films Alien and Aliens, and Star Trek: The Next Generation. Both of these feature their respective antagonists, the “alien” as archetypal Other, and the Borg, symbol of autonomous, collective community. In Alien, the crew of the Nostromo encounters an alien derelict ship that has been mysteriously disabled to find a hive of eggs of alien creatures whose sole role is the creation of egg factories for further reproduction. At the onset of the franchise, pilot Ellen Ripley is positioned as the “everywoman” placed in the center of cataclysmic events. In the Alan Dean Foster book adaptation, and an extended edit of the Scott film, Ripley finds during her escape from the ship that Captain Dallas has been captured and organically transformed into a half-human egg-layer whom she immolates with a flamethrower. However, in the Aliens sequel, the amorphous society of the self-replicating aliens has been replaced by a centralized hive, dominated by a gigantic Queen that threatens to impregnate the daughter-surrogate Newt. This transformation from a faceless to centralized threat creates a figurehead for the threat and establishes a clear protagonist/antagonist relationship, and establishes traditional orthogony.

This simplification of dialectic of asymmetrical politics is also evidenced in Star Trek: The Next Generation by the coming of the Borg, a collective race of cybernetic individuals. Although representations of the Borg vary as to fictional timeline, in televised media they began as a faceless hive-mind, which abducted Captain Jean-Luc Picard as a mouthpiece, not as a leader. It was inferred that if one sliced off or destroyed a percentage of a Borg ship, you did not disable it; you merely had the percentage left coming at you just as fast. However, by the movie First Contact, the Borg now possesses a hierarchical command structure to their network and, more importantly, a queen. With the assimilated and reclaimed android Lieutenant Data, the crew of the Enterprise infiltrates higher level functions of the Borg Collective, effectively shutting down the subordinate elements of the Hive. In addition, the Queen/Leader is defeated, assuring traditional figurehead/hierarchy power relations rather than having to deal with the problems of the amorphous, autonomous mass. There are other “amorphous” metaphors in cinema that address the issue of amorphousness. These include the 1958 movie, The Blob, in which a giant amoeba attacks a small town and grows as it engulfs everything. Another is The Thing, about a parasitic alien that doppelgangs its victims, creating another form of faceless threat. Lastly, we have the classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers where alien plant “pods” would bear fruit of duplicates of living people, giving a metaphor for the Communist threat of the Red Scare originating during the Cold War. Perhaps these are historical references to mediated expressions of anxiety in regard to autonomy’s threats to regimented/striated hegemony, stating that this sort of anxiety and terror are not new.

One of the most asymmetric cultural Western interventions in relation to constructs of traditional power is the involvement of Anonymous as part of the Occupy Movement. Anonymous, which has been called a “hacker group” in the mass media, is a taxonomy created on the online image sharing community 4chan.org, arising from the practice of posting “anonymously” unless one wants to use a name, or handle. Although the idea of Anonymous is at best an ad hoc grouping, the use of the “group” name has been ascribed to various factions. According to The State News, “Anonymous has no leader or controlling party and relies on the collective power of its individual participants acting in such a way that the net effect benefits the group.“ The idea of Anonymous fits with the “faceless collectives” mentioned above, and certainly presents an asymmetric, if not non-orthogonal, exercise of power. Anonymous first rose as a voice of dissent that emerged against the Church of Scientology (see Project Chanology), where flash mobs of individuals in Guy Fawkes masks and suits arrived to protest at sites around the world, with boom boxes playing “The Fresh Prince of BelAir”, a popular agitational or “trolling” anthem. It has engaged in other activities, including hacking credit card infrastructures opposed to handling donations to Wikileaks and creating media around Occupy Wall Street. However, without a clear infrastructure and only transient figureheads, Anonymous functions as an organizing frame for a cloud of individuals interested in various collective actions, and represents an indefinite politics based on networked culture. In an expected exercise of force, during the actions against elements opposed to Wikileaks, conventional power struck back wherever it could against members of Anonymous, by arresting over 21, some violently, in July during the actions against credit providers boycotting Wikileaks. This exercise of power was repeated in September, with admonitions about the arrests appearing on YouTube thereafter. Anonymous has also posted videos in support of the Occupy movement. Such a response is not surprising, but is the exact response to non-orthogonal dissent under our model. The problem is that in arresting any number of Anonymous members, traditional power is confronted with the first, distributed model of the Borg that merely exists minus two or twenty members.

Another dissonance between the Occupy Movement and conventional politics is the perceived lack of agenda. This is due to its dispersion of discourse in giving its constituents collective importance in voice. What is the agenda of the disempowered 99% of Americans, or world citizens marginalized by global concentration of wealth? Simply put, the agenda is for the disempowered to be heard. What does that mean? It means anything from forgiveness of student loans to jobs to redistribution of wealth to affordable health care, and so on. It isn’t a list; it is a call to systemic change of the means of production, distribution of wealth and empowerment in political discourse. It isn’t as simple as “We want a 5% cut in taxes for those making under $30,000.” It’s more akin to “We’re tired that there are so many sick, hungry, poor and uneducated, and we want it to end. Let’s figure it out.” It is the invitation to the beginning of a conversation that has no simple answers other than the very alteration of a paradigm of disparity that has arisen over the past 40 years through American capitalism.

The last challenge to the traditional power discourse is that of passive resistance. This is not a new strategy, especially under the aegis of Gandhi and King’s movements. However, it is traditional power’s mere tolerance of nonviolent resistance that does not result in violence. As we can see from the UC Davis assaults and the dispersions after the second month anniversary, conventional power exerts its force against, as Brian Holmes put it, “anomalies” so that the system can be restored and the commodifiable classes are reintegrated into the system to reproduce its agendas. As long as resistance does not present undue inconvenience for the circulation of power and capital, it is allowed. Once it loses its patience with non-orthogonal forces, or if materially sacralized spaces, like Wall Street are threatened, the hegemonic order is reified. The irony of the technical loophole of Zucotti Park being privately owned and having few rules allowed the Occupy movement also highlights the tenuousness of public discourse in Millennial America. However, even with this oddity, on the two-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, force has begun to be used against the occupiers as traditional power’s patience grows thin with amorphous politics. In the streets, the marches are split up, and rules about occupation begin to be enforced with cupidity. As said before, hegemonic patience has worn thin, with assaults/dispersions taking place in Oakland, Davis, Philadelphia, and New York, among others. However, the movement moves forward for the moment.

Amorphous politics is based on plurality, collectivism, dispersion and ideas. The hierarchical nation-state has no idea what to do with the amorphous blob as it grows except to try to contain it, but as with Anonymous, it is a whack-a-mole game. If one smacks down one protest, two pop up across town, or five websites pop up on the Net. Shut down Wikileaks, and a thousand mirror sites show up. People in the streets swarm New York and other cities throughout the US, and the world, and conflict arises. Asymmetry and amorphousness are dissonances to traditional power. Ideas in themselves are not hierarchical.

Desires sometimes have no agendas.

Sometimes people want what is right, and all of it.

Dragana Zarevska and Jasna Dimitrovska are visual and performing artists, cultural workers and activists from Macedonia, who also, often work together under the artistic pseudonym Ephemerki. While at the same time loving and teasing the rigidity of academism, they like decoding magic, making it transparent, go behind Wizard of Oz’s curtain and put his pants down. The name of the duo is a funny derivate of Bapchorki (band of few grannies who used to sing Macedonian traditional songs in a rustic nasal style). It suggests that Ephemerki are their ephemeral version, or at least, the ones doing the ephemeral part of tradition. Their work is driven from and inspired by Donna Haraway, Judith Butler, Deleuze and Guattari, Agamben, and other contemporary thinkers and practitioners within arts, technology, society.

The Lele method is their latest performance (a performative event for a bunch of people, as they like to call it) and so far was performed at AKTO 6, Festival for Contemporary art in Bitola and Kondenz & Locomotion, Performing arts festivals organized in Skopje and Belgrade. Here is the story behind the project.

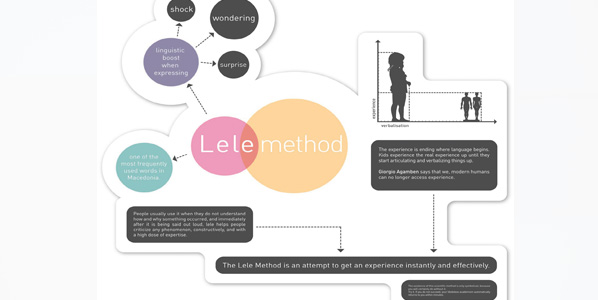

Darko Aleksovski: ‘Lele’ (Мac: леле) is a word that has profound significance in the Macedonian language. It is a universal word that can be used in different contexts and can imply several different emotional states. Can you describe what was the inspiration for this project dedicated to the word ‘lele’? What is the subjective meaning of this word for you?

Dragana Zarevska/ Jasna Dimitrovska: The particular situations this word implies and the problems it addresses might sound quite confusing for the non-Macedonian readers, but, if any of them have visited, or will visit our country, it’ll be deadly surprising how many “leles” per minute one hears around. The word “lele” is totally devoid of meaning, but it is being used to emphasize certain emotions, wondering, shock, great happiness and similar. It is just a shout out, like…the French “oh-la-la” for instance, the Bulgarian “ma-leeeh” or like the Serbian “yoooooy”. The project is being titled “The Lele Method”, directly and totally driven from the local obsession with lele and its possible application.

For us, this word sometimes depicts the shortly shaken numbness and the apathy of our current socio-political constellations, but only with a shout, and then again – everything goes on as usual.

Darko Aleksovski: What is the ‘lele method’? Considering the performative act of the ‘lele’ word, and its everyday use in Macedonian speech, do you think that a method like this can still function as relevant? Can the ‘lele method’ be appropriated by anyone, or it is just a method that you as an artist use?

Dragana Zarevska/ Jasna Dimitrovska: Sure. It can be appropriated by anyone, but it is still a joke. You will certainly do without it as a method. Using it will not bring anything to your life what you’ve not had before. This is how we define it: Lele is one of the most frequently used words in Macedonia… people usually use it when they do not understand how and why something occurred, and immediately after it is being said out loud, Lele helps people criticize any phenomenon, constructively, and with a high dose of expertise. Try it. If you do not succeed, your libidoless academism automatically returns to you within minutes.

These instructions can help a lot in experiencing this useless experience through this useless method. But, stating the obvious with The Lele Method is what we enjoy the most. We give people what they already have, like selling snow to Eskimos.

Recently, in an interview we gave for the Canadian .dpi Magazine we discussed some particular effects we achieved by performing Lele. Nobody is aware of performing it daily here in Macedonia, and while we were preparing the performance out of it/about it, we realized the power of defamiliarization. You perform something which is being performed daily in a constant automatization. By naming a method Lele and putting it on a stamp, we gave the word a particular relevance and a different form. We made it “unfamiliar” and “difficult”, and by that, we prolonged the process of perception of that word. By trying to remove the automatism of perception, we got a new perspective of a word, of a problem. This technique has been used in the literary criticism of Russian formalism to differentiate prose from poetry, but we use it to differentiate and to delay perception. As Russian formalist critic Viktor Borisovich Shklovski has said in his well-known essay “Art as Device,” – the purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known.

Darko Aleksovski: You have presented this project two times so far – as a performance accompanied by the printed version of the scheme of the ‘lele method’. How much performance is a necessary medium for this project?

Dragana Zarevska/ Jasna Dimitrovska: We’ve shown the performance at this year’s Akto Festival for Contemporary Art during August (Bitola/Macedonia), and at the Kondenz & Locomotion curatorially joint festivals for performing arts organized in Skopje and Belgrade during October. We must admit we entertain ourselves a lot during the performance because people enter the room and they perceive it as some irrelevant and boring employees who put a stamp on everyone’s hand at the venue’s door. Then, they look at the stamped hand/arm and shout “Leeeeeh-leeeeeh!” because that’s being engraved on our stamps.

During the performance we are dressed in our Lele uniforms which are extremely office-like and conservative, our faces are shit-serious, and inside the room there are printed materials (scattered leaflets on the tables, or printed panels on the wall) with diagrams on them explaining the empirical part of the Lele Method. The concept behind the Lele Method is being driven by our love and respect towards Giorgio Agamben’s work and his ideas on experience shown in his work Infancy and History. The experience is ending where language begins. Kids have the real experience until they start articulating and verbalizing things up. Giorgio Agamben says that we, modern humans can no longer access experience. The Lele Method is an attempt to get an experience instantly and effectively. The existence of this scientific method is only symbolic, because it is just mocking the academia and the naive ones simultaneously, as – all of the work we did/do by far.

Much of this performance auto-perpetuated, it is happening by itself. Performance is always a necessity. It is better for us to be aware of it, because we all perform all the time. This performance is all about being aware that we perform something of which we usually forget, but is actually performable – something automatized like the word Lele.

Darko Aleksovski: The project was very well received by the audience, other artists and critics. Does it have another aspect of it, that is directed as a critique towards the whole Macedonian art system?

Dragana Zarevska/ Jasna Dimitrovska: Thank you for this notion. Actually it was fantastic how great it was received. Our work can often be seen as an overlap between theory, movement, process and production. The contextualization of these things shapes the performative events we present that test and deconstruct different versions of reality and its geography, directly related to awareness of the possibilities of language. We criticize language/es through language.

Darko Aleksovski: Do you see ‘lele’ differently, now that you have made a project out of it?

Dragana Zarevska/ Jasna Dimitrovska: Yes we do. We got de-familiarized with it (by getting hiper-familiarized), while, at the same time we started to think of it as of our own word, which is pretty selfish. We totally “adopted” it. Other people who came to our performances also tell us they experience it a bit differently than before, one friend said “Whenever I say Lele I think of you!”. We know this might sound weird and vain, but it seems we assimilated it as our own piece of art, and the truth is – it is so not ours, it is everyone’s. We surely assimilated the illusion of having it as ours though.

more about the artists: zarevska [at] gmail.com, yasna.dimitrovska [at] gmail.com

The Transborder Immigrant Tool (TBT) is a project created by the University of California at San Diego’s Electronic Disturbance Theater (EDT) 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab, and still evolving today. Here Ricardo Dominguez, co-founder of EDT (with Brett Stalbaum), Principal Investigator of b.a.n.g. lab, and Associate Professor in the Visual Arts Department at UCSD, discusses the project with Lawrence Bird. The interview includes input from other members of the collective: Brett Stalbaum, Micha Cardenas, Amy Sara Carroll and Elle Mehrmand.

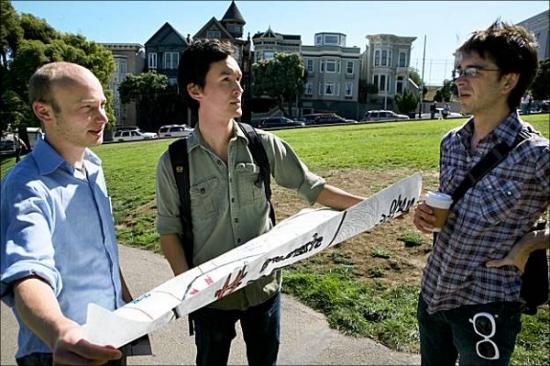

Lawrence Bird: Simply put, the Transborder Immigrant Tool is a hand-held device to aid crossers of the Mexico-US border. As far as the cultural and political implications of this device, it’s loaded. But as a starting point, could you tell us a little bit about the technical side of the device?

Ricardo Dominguez: We began with the basic question: what ubiquitous technology would allow us to create an inexpensive tool to support the finding of water caches left in the Southern California desert by NGO’s? Our answer was that the sub-$20 iMotorola phone series could be made useful for emergency navigation. The early generation of the platform we targeted can be made reasonably useful in a better-than-nothing scenario. Meanwhile, later phone generations (that don’t yet cross our price barrier but are getting closer everyday) are already fully useful as practical aids without even a SIM card installed or an available network service. With proper use, the GPS performance of newer phones equals any GPS designed for desert navigation, and their used prices are falling. Moreover, GPS itself does not require service and has free global coverage, courtesy of the United States government. In an emergency scenario, we trust these later mobiles to direct a lost person to a nearby safety site. The TBT’s code is also available on-line to download at walkingtools.net, sans water cache locations, for any individual or community to use for their GPS investigations.