Exhibition at HTTP Gallery by Doron Golan and Michael Szpakowski – Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent…

DORON & MICHAEL

BY EDWARD PICOT

The art of Doron Golan and Michael Szpakowski is in many ways a product of the digital revolution. Without that revolution it could not have existed in its present form, but from within that revolution, as artists and curators, they have contributed both to the development of a new kind of experimental film-making, and to the establishment of the online community which has allowed it to flourish.

The advance of digital technology has affected most branches of the arts, but perhaps none more profoundly than film. The word “film” itself has rapidly become a misnomer, with computer files replacing celluloid as the medium of capture and storage. As a result, the old-fashioned distinction between “film” and “video” – which goes back to a division between technologies for the cinema and television – has become less and less hard-edged. It is still rare for programmes originally made for television to be shown at the cinema, but certainly not vice versa, and increasingly movies and videos of all kinds are being watched on people’s computers.

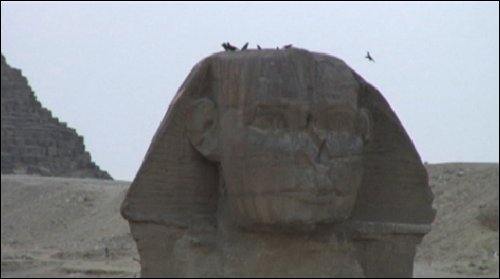

Doron Golan, Sphinx11, 2007, Digital Video

Another effect of digitisation has been that filmmaking has become much more “doable” for ordinary people. A few years ago it came as a pleasant surprise to discover that your digital camera could be used to shoot movies a few seconds long. Nowadays you can capture extensive footage with your mobile phone, and having done so you can process it, edit it and add sound in increasingly sophisticated ways, using relatively cheap software on your PC. In other words, provided you are prepared to invest some time and effort, you can make movies without specialist equipment or facilities, for a fairly minimal outlay.

The third element of this revolution has been the use of the Web as a means for making independent work available to a global audience. With the growth of broadband the amount of time it took to download a short video was dramatically reduced, and streaming technologies came into their own. The public’s appetite for watching numerous short videos rather than longer, more linear pieces had already been demonstrated back in the 1980s by MTV. The Web soon proved that such short videos didn’t have to be welded onto pop tunes, or finished to a slick commercial standard, to find an appreciative audience. It also brought about a rapid transformation from a “push” culture to “push-and-pull”, where the public are creators as much as consumers of the work that appears online.

Michael Szpakowski, The Way Home, 2007, QuickTime Movie

The criticism most frequently aimed at this “push-and-pull” culture is that it produces far more porn and derivative dross than anything else. It’s a difficult accusation to deny, but it is also true that the explosion of home-made digital art has stimulated an enormous amount of artistic experimentation, and amongst the dross it has thrown up innovative work of genuine artistic merit. Furthermore, although it would be an exaggeration to say that the Web encourages cream to rise to the top, it does permit people to find work in which they are interested without becoming bogged down amongst the also-rans. One of the most fascinating things about the Web, in fact, is the way in which it seems to organise itself, synapse-like, into a proliferation of minor networks and circuits, allowing particular kinds of material to find their niche audiences, sometimes without the wider public being aware of their existence at all, but always with the potential for crossover.

Doron Golan and Michael Szpakowski have been actively involved in this process for some years now, both through their curatorial activities and their own artistic practice. On the curatorial side, Golan set up the DVblog website (http://dvblog.org/) in 2005, with the aim of promoting QuickTime video as an artform, with particular emphasis on artistic experimentation. (“Whilst we don’t turn up our noses at the trivial, popular & amusing,” says the website, “we also try to bring you the best in new & challenging work.”) Szpakowski became one the co-curators shortly after the site launched, and since 2007 has been its primary editor.

Doron Golan, Burning Promenade, 2008, Digital Video

On the artistic side, Golan (whose work can be seen at http://the9th.com/) says “In ’98 I started using Apple’s QuickTime architecture as my main working tool”. Like everyone posting films on the Web at that time, his work shows a keen awareness of the constraints imposed by narrow bandwidth. The earliest pieces on his site combine multiple small QuickTime windows, positioned via HTML, into ingenious abstract and near-abstract compositions. Szpakowski entered the arena slightly later, beginning to publish new media work such as An Enemy of the People (a Shockwave piece) online in 2002. By 2003 he had already started making QuickTime movies (subsequently collected online as “Scenes of Provincial Life,” http://www.somedancersandmusicians.com/vlog/ScenesOfProvincialLife.cgi): these quickly became “a major focus” of his work and have continued at the rate of at least two or three per month ever since.

Apart from their devotion to QuickTime and their association with DV Blog, Golan and Szpakowski share a number of other characteristics, which seem to suggest that they belong to the same “school” of experimental filmmaking. Both of them have dabbled in code and computer-generated imagery – abstract films, where what we see on-screen is created by programming rather than recorded from the outside world; but without eschewing such techniques altogether they have both tended to move towards a more overtly representational style as their work has developed. Both have sometimes used archive footage, and in doing so have displayed one of the signature motifs of digital art, a tendency to remix and “mash up” material originally produced by other hands. Both have used techniques of slowing footage down, speeding it up or running it backwards to encourage their viewers to look at familiar things afresh, or to invest everyday scenes with magical, surreal qualities.

Both have also shown considerable interest in the Lumiere Manifesto (see http://videoblogging.info/), which, following in the style of the Lumiere brothers who were among the pioneers of cinema, demands simplicity of technique from the film-maker: a fixed point of view with no panning, no zooming, no editing and no “effects”. Neither Golan nor Szpakowski is inclined to stick to the tenets of this manifesto rigidly, but their shared liking for the minimalism of the Lumiere does imply certain other qualities: an eye for a good subject; an inclination to let that subject “speak for itself”; a sense of composition; an interest in the small details of apparently-uneventful scenes; and a willingness to strip away the conventions of commercial video and film practice, to get back to the basics of film-making.

Having said all this, there are also noteworthy differences between the two. Golan’s work, in places, has a theatricality which extends to the use of actors and scripts. There are points at which his films resemble something by Samuel Beckett, in their unsentimental mingling of the absurd and the melancholic, their hilarity and their focus on the discomforts of human flesh. Elsewhere, he shows a genius for capturing “real-life” individuals, both their quirks and their dignity, sometimes conveying a great sense of complexity in an astonishingly short space of time. This same sense of balanced complexity comes across from his handling of political themes, which is an important aspect of his work. His films often confront us with politically explosive material, and by avoiding cliché and focussing on unexpected details they invariably challenge our preconceptions and leave us feeling both bewildered and liberated.

Michael Szpakowski, House and Garden, 2008, Animated GIFS and JavaScript

In some ways one of the fundamental aims of Szpakowski’s work is very similar: to make us look twice at the things we thought we already knew. In his case, however, there is a personal, everyday quality to his output, which makes it feel more autobiographical, less public. We are often in his house or his back garden, walking the streets of his hometown, or riding with him on a bus or a train, sometimes meeting his friends or his relatives. There are fewer character-studies, but there is more of a sense of social milieu. One obvious point of comparison with Golan is that Szpakowski’s films are often accompanied by music he has composed himself, sometimes comical and bustling, sometimes urgent and driving, and sometimes wistful and nostalgic. The subject matter is everyday, but charged with symbolism, magic, and often a really poignant sense of time. Fallen blossom floats back into the tree from which it fell. Anonymous strangers are glimpsed walking along pavements, or looking out of windows. Old black and white photographs mingle with illustrations from a child’s picture book.

Michael’s videos are far more numerous than Doron’s, and partly because of this his work has a more spontaneous, intuitive feel, and perhaps less sense of structure and intellectual rigour. In terms of painting, if Golan reminds us of a great formalist such as Seurat, then Szpakowski reminds us of an impressionist such as Sisley – or, in his more dreamlike moments, a post-impressionist like Chagall. And the references to painters are not inappropriate, because both men have amply demonstrated, over a period of years, how in the right hands the short film can be an artistic medium every bit as expressive and full of formal possibilities as canvas and pigment.

Information:

Edward Picot is an artist and writer based in Kent, UK. He holds a PhD in English Literature and has a particular interest in hyperliterature, having founded the Hyperliterature Exchange in 2003.

He frequently publishes art criticism and creative writing online. http://edwardpicot.co.uk

Published on the occasion of the exhibition – Whereof one cannot speak; thereof one must be silent: Doron Golan and Michael Szpakowski,

HTTP Gallery, London, 16 January till 28,

February 2009.

HTTP Gallery in Haringey, North London, is Furtherfield.org’s dedicated space for media art. Furtherfield.org provides platforms for creating, viewing, discussing and learning about experimental practices in art and technology. Furtherfield.org and HTTP Gallery are supported by Arts Council England, London.