From September 2008 – June 2010, Ellie Harrison undertook a Leverhulme Scholarship on the Master of Fine Art programme at Glasgow School of Art. The thesis published below forms one of the major outcomes of her research during this period. This is part one of four.

The thesis published below forms one of the major outcomes of her research during this period and builds on two earlier essays How Can We Continue Making Art? – which questions whether there is a place for art in a world which is fast approaching environmental catastrophe, and Altermoderism: The Age of Stupid – which uses Nicolas Bourriaud’s Altermodern exhibition at Tate Britain in 2009 as a paradigm for exploring the art world institution’s lack of acknowledgement and action over climate change.

Trajectories: How to Reconcile the Careerist Mentality with Our Impending Doom addresses the ethical implications of continuing to choose the career of artist in the twenty-first century. It is a manifesto of sorts, written from the personal perspective of a young UK-based artist looking to identify worthwhile reasons for continuing down this ‘self-interested’ path, given that the future we are likely to face as a result of climate change, is so different from how we dreamt our careers might pan out whilst growing up under Thatcher and New Labour. It explores how we should aim to evolve our roles as artists, in light of this, and what form a new ‘reconciled practice’ might take.

The graph below shows the projected average global temperature increase over the forthcoming century if we remain on our current trajectory of economic growth and population increase (peaking at 9 billion in 2050), but also incorporate new efficient technologies, a convergent world income and a balanced emphasis on energy sources. This is known as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s ‘scenario A1B’ (IPCC 2001).

The graph is extracted from the official AVOID response to the United Nations Climate Change Summit in Copenhagen in December 2009 published on 26 March 2010. AVOID is a United Kingdom governmental research programme led by the Met Office with the aim of averting dangerous climate change (AVOID 2010).

Looking back, 1979 now emerges as a pivotal year in the recent history of our species. On 6 October this year the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, increased interest rates by 20 points (Fisher 2009, p.33). This act, which on paper appears of little significance, opened the gates to a whole new breed of free-market capitalism which, as a result of reduced regulation, would spread its way all over the globe. It signified the switch between Fordism and post-Fordism as the predominant economic system of production; from the ‘disciplinary societies’ of late modernism characterised by Foucault, to the ‘control societies’ which constitute our present reality (Deleuze 1990). It was the beginning of a carefully choreographed and intricately planned neoliberal project, which would serve the “restoration or reconstitution of naked class power” (Harvey 2007, p.119) to an economic elite; radically transforming the way in which all our lives would operate in its wake. Our attitudes towards work, politics, society; our relationships to one another, even the internal structuring of our own minds, would never be the same again.

It is no coincidence that it was on 4 May 1979 that Margaret Thatcher came to power in the United Kingdom; she was, of course, instrumental in overseeing this ‘revolution’. What is coincidental however is that it was also in 1979, on 11 March to be precise, that my own life began its trajectory. The rapidly changing society into which I was born would not only prove fundamental in shaping the artist I would become, but it would also prove key in determining the ‘mentality’ with which I would come to visualise my future: to plan my career.

‘Thatcher’s children’ as my generation are known, were indoctrinated to believe that the world owed us a living (Blackburn 2009). “Success”, she said, was “a mixture of having a flair for the thing that you are doing; knowing that it is not enough, that you have got to have hard work and a certain sense of purpose”. It was simply a question of making the right career choice. If we aimed for the top, we had just as much chance of getting there as anyone else. All we had to do was look out for number one. The secret, she taught us, was to have a strategy – to “plan your work for today and every day, then work your plan” (M. Thatcher n.d.); to think about what we wanted our lives to be like in the future and then to work flat-out towards that ‘goal’.

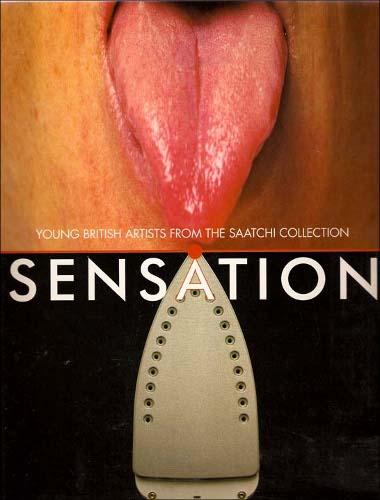

In hindsight, it now seems inevitable that my life took the course it did. Entering art school for the first time in 1997 – the year the seminal Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts took place – we could see ‘success’ being played out before our very eyes. A group of Young British Artists (YBAs), just one generation older, were now ‘living the dream’. As 18-year-old students, we were now able to visualise the paths we wanted our own lives to take and to see exactly where we aimed to find our fortune. Like most of my art school peers, I was from an “above average social background” – raised in suburbia by a middle class family of teachers. And, as Hans Abbing notes, this added “social capital” gave me the “flair, self-assurance, and… sense of audacity” (Abbing 2002, p.95) which now seemed so essential to commodify and sell myself – to keep going, regardless of failure and rejection, with eyes firmly fixed on the prize.

My career trajectory led me blinkered along a familiar path – a BA (Hons) degree in Fine Art from Nottingham Trent University; a Postgraduate Diploma in Fine Art from Goldsmiths College (where nearly all my YBA role models had been before me). It was as though every incremental step took me ever closer towards my ‘goal’: towards ‘success’. Finally, I won a scholarship to study on the Master of Fine Art (MFA) programme at The Glasgow School of Art; yet another prestigious art school to add to my expanding curriculum vitae. What I hadn’t banked on, however, was that on the very same day I was heading north up the M1 to Glasgow to begin this new stage in my life, the global economic order was fast collapsing around us into its own new distinct epoch, taking with it the belief systems which had been carefully constructed around it over the past 29 years.

On 15 September 2008 the investment bank Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. filed for the biggest bankruptcy in US history with more than $600 billion of debt (Mamudi 2008). Over the course of the next year a slew of bailouts took place all over the world to prevent other banks going under. The neoliberal project had, “in every sense, been discredited” (Fisher 2009, p.78). The ideology on which, knowingly or not, my own life’s trajectory had been modelled was now on the ‘scrapheap’. And, as Mark Fisher suggests, a bleak, empty and relentless state known as ‘capitalist realism’ – in which nobody could believe, but equally nobody could stop – crept in from every corner to fill the void.

Society, it seemed, had reached a hiatus; a ground zero amid a sea of “ideological rubble” (Fisher 2009, p.78). Lots of suggestions emerged about what had gone wrong, lots of questions about where we should go next. From the privilege of my funded MFA place, I was able to enter into my own period of self-reflection about the path I had so blindly been following. Was the vision I upheld of my life in the future essentially a delusion, based on a now defunct model of ‘success’ from the past? Was I suffering from the “self-deceit” (Abbing 2002, p.114) Hans Abbing diagnoses to be prevalent in young artists, coupled with the complete “disavowal” (Fisher 2009, p.13) of the negative side-effects of my complicity in the system of capital? With a sudden and overwhelming urgency it felt essential that I question how I could begin to reconcile my career choice and the entrepreneurial methodology (Abbing 2002, p.96) with which I was pursuing it, with the harsh realities that both science, and now science fiction, are predicting the future actually holds in store…

Films such as The Road (Hillcoat 2009) offer us a very different picture of the forthcoming century. In this barely hospitable, yet eerily recognisable version of our present world there is no Turner Prize, no Frieze magazine to be reviewed in; no canon to become part of. In fact, there is no scope for the non-essential; no room for aesthetics; no space for art at all. Whereas it now appears clear that the trajectory I had planned for my life since art school is constituted by fantasy, the trajectory which befalls the lives of the protagonists of this particular post-apocalyptic vision is in part based on what the current overwhelming scientific evidence points towards.

The United Nations Climate Change Summit which took place in Copenhagen in December 2009 offered what many scientists and campaigners referred to as our ‘last chance’ of averting global catastrophe within the coming century. Prior to the talks the 10:10 Campaign’s ‘call to arms’ statement outlined what sort of trans-governmental worldwide commitment it would be necessary to achieve:

“The best deal currently on the table is that from the EU, which calls for a 30% reduction [in greenhouse gas emissions] by 2020 (compared to 1990 levels). If this deal were to be accepted (which is a very big if, given that Japan argues for 8%, Australia for 5% and America for between 0%-6%) and if the emission cuts were then carried out (which is an even bigger if), this would give us about a 50/50 chance of not hitting the dreaded two degrees. Two degrees is where we trigger runaway climate change [emphasis added]: two leads to three, three to four, four to five, five to six… by which time it’s about over for life on Earth.” (Armstrong 2009b)

Given that Copenhagen was by all accounts a complete failure and that, in fact, not even the least significant of the ‘deals’ presented was agreed upon and signed off, the balance now appears to be swaying decisively towards the latter of these two potential trajectories. We find ourselves “trapped inside a runaway narrative, headed for the worst kind of encounter with reality” (Kingsnorth & Hine 2009, p.11). Unless it is fully acknowledged and hastily acted upon in consensus across the globe, climate change “threatens to render all human projects irrelevant” (Kingsnorth & Hine 2009, p.6). It appears that it is not just the future of our careers we should be worried about but now, more likely, the fundamental ability of our species to survive on the planet.

The concern of this essay is to uncover exactly how we could have arrived at a situation where these two distinct visions of our future can so wildly diverge – to explore the factors which have allowed our careerism to persist, in light of advice to the contrary. The aim is to illuminate the significance of this ‘now or never’ moment in the history of our species as an opportunity for radical change, and to develop a ‘plan of action’ and a ‘new moral code’ which may help us, as artists, determine what role we can and should play in the reality of the twenty-first century.

To read Part 2 of this article visit this link: http://www.furtherfield.org/articles/trajectories-how-reconcile-careerist-mentality-our-impending-doom-part-24

——-

References:

Armstrong, F., 2009b. What is 10:10? 10:10 Campaign website. Available at: www.1010uk.org/1010/what_is_1010/arms [Accessed April 10, 2010].

Abbing, H., 2002. Why Are Artists Poor?: The Exceptional Economy of the Arts, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

AVOID, 2010. Will the Copenhagen Accord avoid more than 2°C of global warming? AVOID website. Available at: ensembles-eu.metoffice.com/avoid [Accessed May 3, 2010].

Blackburn, S., 2009. Do we need a new morality for the 21st century? The Guardian Culture Podcast. Available at: www.guardian.co.uk/culture/audio/2009/nov/02/cambridge-festival-of-ideas.

Deleuze, G., 1990. Society of Control. L’Autre Journal, (1). Available at: www.nadir.org/nadir/archiv/netzkritik/societyofcontrol.html.

Fisher, M., 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Ropley, Hampshire: 0 Books.

Harvey, D., 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hillcoat, J., 2009. The Road, Dimension Films.

IPCC, 2001. Special Report on Emissions Scenarios. GRID-Arendal website. Available at: www.grida.no/publications/other/ipcc%5Fsr/?src=/climate/ipcc/emission [Accessed May 3, 2010].

Kingsnorth, P. & Hine, D., 2009. Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto. Available at: www.dark-mountain.net/about-2/the-manifesto.

Mamudi, S., 2008. Lehman folds with record $613 billion debt. MarketWatch website. Available at: www.marketwatch.com/story/lehman-folds-with-record-613-billion-debt?siteid=rss [Accessed April 25, 2010].

Thatcher, M., Margaret Thatcher Quotes. About.com website. Available at: womenshistory.about.com/od/quotes/a/m_thatcher.htm [Accessed May 2, 2010].