Featured image: Healing Station. mixed media, interactive installation, size variable. Christy Matson and Jon Brumit, 2009.

The New Materiality: Digital Dialogues at the Boundaries of Contemporary Craft.

March 10–June 12, 2011

Decorative Arts Gallery

http://www.mam.org/exhibitions/details/new-materiality.php

For the first half of the 20th century, curator Fo Wilson reminds us, the practice of craft was heralded as a “remedy” to how human values were changed by the Industrial Age. Here the hand-made was given privileged status over the machine-made, and thus craft forms gifted new value through the artisan. In the latter part of the last century, as the world moved from apprenticeship and artisanship to a more intellectual and theoretical-based framework for valuing contemporary art, so too have craft practices and discourses been challenged. This rethinking of craft has accelerated in the last several years, with books like Glenn Adamson’s Thinking Through Craft and Howard Risatti’s A New Theory of Craft (both 2007), both arguing for conceptual rigor and provocative possibilities within craft as a discipline.

The New Materiality: Digital Dialogues at the Boundaries of Contemporary Craft, an exhibition that began at the Fuller Craft Museum and is currently up at the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM) until June 12, follows on and extends current trends in contemporary craft. It engages not only with craft’s reinvigoration as a creative practice and discourse, but with how these have been shaped by, and also transformed, new technologies, new designs, new materials and new ideas. Wilson’s exhibition and events make discussions around Art or Craft, Art or Design, Digital or Hand-made, and Conceptual or not seem, in a word, quaint; she engages with a broad set of materialized ideas that divide and relate across the artistry of craft, the ephemera of technology, and the theoretical frames of post-conceptual art.

The exhibition can perhaps best be summarized through the work of the four exhibiting artists/artist teams that spoke at the “Dialogues on Innovation” panel at the Milwaukee Art Museum on April 16th. Collaborative artists Donald Fortescue and Lawrence LaBianca, for example, spoke to Milwaukee activist and printmaker Nicholas Lampert about their piece, Sounding. This work consists of a huge, custom built cabriole-legged table, which was initially filled with beach rocks and sunk to the bottom of the ocean. There it lay, for two months, with a hydrophone to record the ambient sounds of the sea, including the overwhelming swish of waves, the low hum of slow-moving current, and the activity of sea life – the most prominent being the continuous clicks of what must be shrimp in its vicinity. When the artists’ creation reemerged, it brought the bottom of the ocean with it: all the messiness and stink and poetry of the sea – barnacles, rusty parts, plant life, fish scents, mystery and more. It is exhibited with an over sized hornlike funnel, a huge phonograph tied together with zip ties, to amplify the recorded sound.

Sounding, avowedly inspired by Captain Ahab’s hunt for an un-killable whale, acts as a kind of parallel to the ongoing hunt for singular disciplinary focus in craft. The piece dives into the sea, hits “rock bottom,” and looks as if it barely survived; and on its return, we see that Sounding is far from a singular entity. Yes, it is trashed and torn, but it’s also imbued with literal life, entwined with technical innovation, and rich with stories of its journeys. Like the theories and practices behind the current craft movements, it came back more beautiful, more visceral, more sensory, and more technological than it ever was: a new materiality.

You can listen to or download Sounding file here:

http://www.furtherfield.org/audio/Soundings-1.mp3

My discussion with artist Christy Matson revealed an exploratory practice that shifts between digital and hand-made, generative and interactive, and always with an eye towards the implications of each. Soundw(e)ave, her piece on show, is a self-referential textile, where the actual sounds of computerized Jacquard looms were used to create woven compositions. Her noisy sound waves were turned into three patterned pieces of fabric, made by hand-operated, computer-assisted and fully automated (Jacquard) looms, respectively – each weave growing progressively denser with the more advanced technologies used in their production. The piece, says Matson, was a huge turning point in her practice; it pointed her towards a kind of digital craftsmanship, where she was better able to place value on the ideas, materials and skillfulness needed to be an artisan across contemporary digital, craft and art domains.

Soundw(e)ave, generative weaves, triptych (each 34″ x 54″). Christy Matson, 2004.

For example, Matson then began weaving copper wire directly into her fabrics, and, using the magnetic waves our interactions generate and alter, engendered new aural compositions. In other words, her sonic sculpture turns cloth into a Theremin, where movement and hand-waving at the gallery are transformed into the kinds of musical gestures often associated with science-fiction films of the seventies. While Matson’s earlier, sound-generated works were generative and performative on some level, here she moves into real-time interaction, invoking our embodied relations to textiles, craft, technology and language, all in one fell swoop.

healing station, a collaboration with Jon Brumit and quite possibly the most complex of Matson’s installations thus far, sees piezo sensors placed inside of swaths of fabric to pick up the ambient sounds of the room – including gallery-goers, passersby, street sounds, and the minute vibrations in the fabric itself. This lovely noise is then fed back into the space with bass shakers: speakers optimized for sending waves into solid media rather than air. Viewers can literally feel the low hum of presence, absence and movement as the textile, bodies and room speak at and to one another in a perpetual feedback loop of embodied music. The small crowd at the MAM laughed along with Matson when she relayed a story in which her wired-up piece, and its feedback, caused a small fire at one of its showings – quite a performance, indeed.

Tim Tate artfully explained to Milwaukee staple Tom Bamberger that nowadays “craft” is a starting point rather than an end point. I’m paraphrasing here, but he treats craft as an approach, a space of understanding materials, what they’re good at, perhaps their “habits,” and most certainly their implications. Here, narrative, function and the conceptual are always already implicated across technique – whether new or old – and value is derived from a contextual corpus.

Tate’s work is itself a beautifully resolved hodgepodge of hand-blown glass, hi-tech LCD screens, and visceral videos of typewriters and books, all literally tied together with plastic (zip ties again – don’t knock it ‘til you try it!) around a printed circuit board. In Virtual Novelist, for example, miniature monitors display the aforementioned “dead media” tools from behind artefactual casings of glass. Atop are beguiling sculptural homages to each of the gone-but-not-forgotten analog recording devices of yesteryear.

Bamberger is a smart artist with a quick wit, and Tate is similarly not one to spar with unless you have a good grasp of the discourses at hand. In this lively thirty-minute discussion, the two managed to disarm the Art vs Craft debate as both unproductive and long-since over, and open up possibilities for “ornamental aesthetics” in time-based media. Here the implication was that, following Tate’s lead, video objects and installations could place more emphasis on the object and installation – rather than the video – and use each as an equal material that informs and plays off of the other; the video and screen need not be the central focus.

Sonya Clark then told us how she views her practice as a fiber artist as similar to how author Toni Morrison views her own writing practices. In one of her essays (found in several publications, including a collection entitled What Moves at the Margin), the latter tells a story of the Mississippi River, which was laboriously straightened for travel and transport by boat. Every so often, the river floods; but, Morrison goes on, it’s not really flooding. It is remembering. The water is trying to get to where it belongs, to re-member, to embody again. Morrison says writers do the same with their texts; and Clark claims that she remembers through her materials. Originally trained as a fiber artist and now working across found objects, digital art and more, Clark’s practice sees her reclaiming forgotten histories, and giving them greater potency through her processes and media.

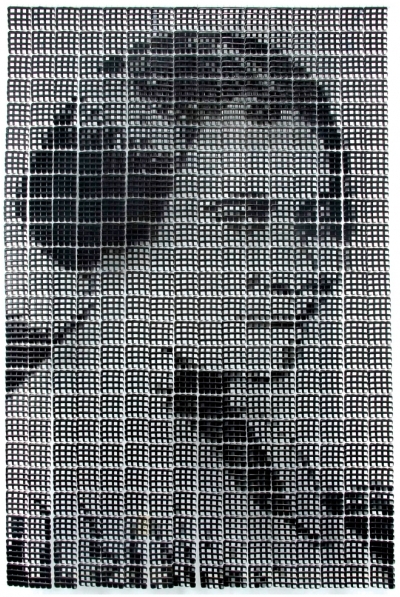

Clark discussed this approach with longtime friend and former colleague, UW-Madison Professor Henry J. Drewal – one of the foremost thinkers surrounding African Art. Clark’s brilliant work on the exhibition, a portrait of Madam CJ Walker, is constructed entirely out of small, acrylic and thin toothed, black hair combs. She overlays the combs and removes some of their teeth to make a huge, grayscale, and literally bit-mapped image.

Madam Walker, the first ever female millionaire in America (and African American to boot), made her fortune selling beauty products to black women hoping to straighten their hair – as was the fashion of the time. And so Clark utilizes her combs, with their own memory, narrative and political weight, to construct a lo-resolution digital image. This exceptional work manages to explicitly straddle issues of race, gender, class, memory and materiality on its very tactile surface, and implicitly engage with the contemporary conceptual frames of digital art and data, in its transcoding of the image from one form to another, and craft, in the final material and hand-made form it takes.

Clark finished with the generous idea that, at present, all art work is collaborative in that it fits into broad social and cultural contexts, builds on extant technologies, and is produced, received, and engaged with outside of the individual’s studio. And Drewal concluded by declaring that technology has always been at center of the arts in the form of new techniques. When something comes into the world, he went on, whether technical or formal or as an image, artists take it someplace else. They “turn common objects… into uncommon things, stretching our imagination and the world” along with them.

These are just a handful of the works in The New Materiality, by four of the artists represented in our discussions – not even all the works they contributed, much less those of the other artists, which include Brian Boldon, Shaun Bullens, Lia Cook, E.G. Crichton, Maaike Evers, Wendy Maruyama, Cat Mazza, Nathalie Miebach, Mike Simonian, Susan Working, and Mark Zirpel.

It is a show that, in its entirety, succeeds in stretching our imagination, through its expansion of craft, art and digital forms, and what they individually and collectively mean today.

Nathaniel Stern (USA / South Africa) is an experimental installation and video artist, net.artist, printmaker and writer. He has produced and collaborated on projects ranging from interactive and immersive environments, mixed reality art and multimedia physical theatre performances, to digital and traditional printmaking, concrete sculpture and slam poetry http://nathanielstern.com.

‘Made Real’, an exhibition by Scott Kildall and Nathaniel Stern, the founders of Wikipedia Art. Can be seen at Furtherfield’s Gallery from 27th May 2011 http://www.furtherfield.org/exhibition/made-real