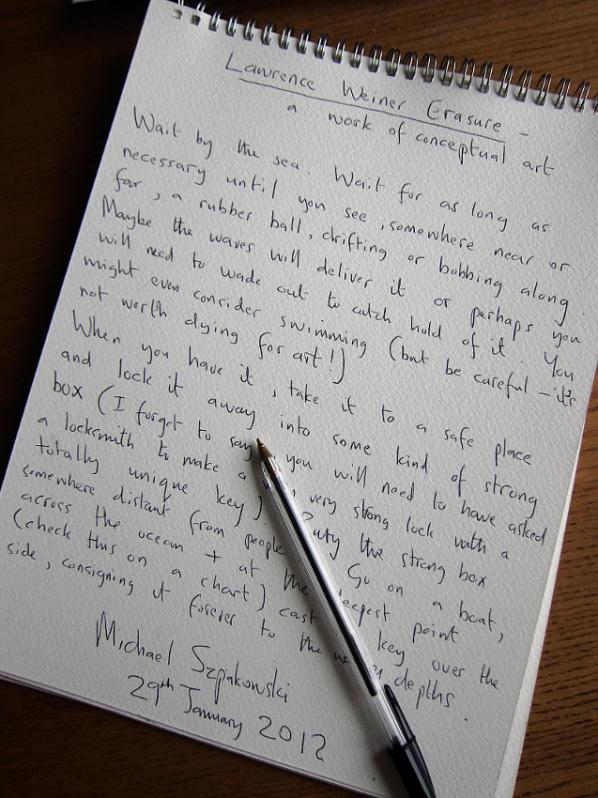

Michael Szpakowski’s “Lawrence Weiner Erasure“, 2012, presents itself as an erasure of Lawrence Weiner’s “A RUBBER BALL THROWN ON THE SEA“, 1969. It takes the form of a handwritten text on a drawing pad accompanied by the ballpoint pen used to write it and an edition of framed photographs of them.

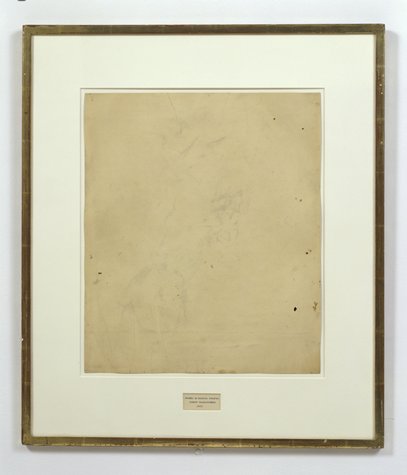

The best known act of erasure in twentieth century art is Robert Rauschenberg’s “Erased de Kooning Drawing“, 1953. The young Rauschenberg visited Willem de Kooning at the height of the latter’s fame and asked for a drawing to erase. de Kooning obliged, but ensured that Rauschenberg would have his work cut out by choosing a drawing that would be particularly difficult to erase. It took Rauschenberg a month to get the paper almost free of marks (its catalogue entry lists the medium as “traces of ink and crayon on paper”).

This was a clear act of iconoclasm and generational positioning by Rauschenberg but he was not reacting negatively to de Kooning’s work or fame. Rauschenberg had previously been erasing his own drawings but felt that this lacked creative tension. Using a de Kooning drawing gave both an aesthetic and an artworld weight to the act of erasure. Although fitting neatly into the historical era of Neo-Dada, its relational and performative content can also be read through the lens of the conceptual art of a decade later.

Conceptual art’s journey from institutional critique to critically important part of contemporary art institutions is a cautionary tale for artists with any kind of political or social aims. In the nineteen-sixties it must have seemed that an idea typed on office paper or published in a photocopied journal could never be sucked into the market for authentic artworks as defined by Greenberg’s ideas of painting and sculpture. When Art & Language were recently asked to authenticate what a dealer had been told were previously unknown prints of theirs from the sixties, they pointed out that they must be fakes as they were on “good paper”. But the very difficulty of acquiring and preserving early conceptual art, both for collecting by private collectors and for display by public art institutions, has made it increasingly appealing and valuable precisely because of its lack of physical quality.

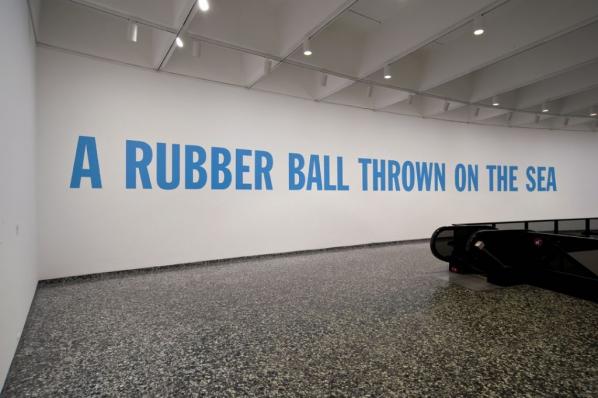

Many artists have followed their work through this transition, the artistic equivalent of an indie band turning to stadium rock as their audience grows. Lawrence Weiner started out in the 1960s making (or in fact not making) such works as “ONE STANDARD DYE MARKER THROWN INTO THE SEA”, 1968, and “A REMOVAL OF THE CORNER OF A RUG IN USE”, 1968. These started naturally as happenings-era proposals for performances and installations that were never made, instead becoming art in themselves. Over the years Weiner responded to the need to display these simple texts in increasingly grandiose public contexts with increasingly large typographic arrangements painted onto or cut into walls and floors. I appreciate Weiner’s work but it is easy to appreciate the criticism that it has progressed more in the scale of its presentation, than in its form or content.

Against this backdrop of institutional recuperation and inflation of the history of conceptual art, Michael Szpakowski has turned to Rauschenberg’s erasure and Weiner’s concepts. Rather than recreate the current large-scale installations of Weiner’s texts, he has gone back to conceptual art’s simple material and conceptual roots with a hand-written text. I initially read the tone of voice of that text as the artist’s own. In fact it is not (as he pointed out in a private email exchange). It is a conscious part of the aesthetics of the piece and the effect it must create in order to persuade the viewer to enter into the imagined actions that it describes.

Those actions serve to undo, or erase, the action described in Weiner’s original. They undo both the action and its formal properties. The experience described in Szpakowski’s text is of a different duration and character to that described in Weiner’s. The length of Szpakowski’s text contrasts with Weiner’s gnomics very clearly. It also relates to the thoroughness required to erase a vivid drawing or concept. And it is a product of the requirement to create the mental self-image in the audience of standing by the sea waiting, to really create that concept in someone’s mind. This requires a number of words longer than “stand by the sea and wait for a rubber ball to drift into view”.

Using handwriting rather than wall-sized cut vinyl letters reproduces the Johns/de Kooning power relationship in the form of an aesthetic relationship between the simple recording of an idea and Weiner’s increasingly grandiose and expensive typography. It evokes Weiner’s humble (but authentic…) beginnings and brings this into tension with the artworld monster he has become. This is a dialectical art, of aesthetic and conceptual tension and what they generate. Though it may seem to be more about the artworld than about geopolitics (as was the case in Art & Language’s Cold War-era “Portrait of Lenin In The Style Of Jackson Pollock”), the artworld and the careers within it are a reflection of broader socioeconomic changes.

Making an edition of photographs emphasizes the work as competent contemporary art given the increasing prevalence of editions in the art market. The contrast between the edition and the physical original draws in the economic and social relationships between the privileged individuals who pay for and experience the work itself and those of us who just see photographic records of it in galleries, books and magazines. The digital image is also Lawrence Weiner Erasure available on Flickr as a Creative Commons Attribution-Licenced download, making it Free Culture as well. This sits in further tension with the idea of an edition. And it is an important moral statement when making work by excercising one’s right to commentary on and reference or depiction of the work of previous artists, protecting the rights of future artists and critics to do so in turn.

Lawrence Weiner Erasure – a work of conceptual art

An erasure of Lawrence Weiner’s ‘A RUBBER BALL THROWN AT THE SEA’ 1969

Download/Print the photo: free, help yourself

Framed photos, limited edition of five (four currently available): £100 each

Drawing pad, with text and ballpoint pen: £750

Raushenberg and Weiner are two favourite artists of mine (although I can’t stand Rauschenberg’s comic strip panels). More to the point, they are well known within the artworld and their institutional histories are useful critical resources. “Lawrence Weiner Erasure” is an aesthetically and conceptually literate and effective mash-up of the form of Weiner’s art with the content of Rauschenberg’s that expresses an important critique of the history and experience of conceptual art.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.