Someone said to me ‘To you football is a matter of life or death!’

and I said ‘Listen, it’s more important than that’.

Bill Shankly

Drawing is one of the two oldest purely cultural – in the sense of playful, not directly concerned with keeping body and soul together like cooking or hunting or shelter – activities that comes down to us today directly in the form of artefacts from between 25 – 35 thousand years ago [1] (the other is music [2]). There is no known human culture that has not made representational and other marks with something, on something, for both fun and survival. Furthermore, as Patrick Maynard demonstrates in his steely eyed and magisterial Drawing Distinctions [3], it can be shown to be the practice which more than any other underpins not only all of present day visual culture (including photography, which, following Maynard [4], we read as a species of drawing) but also the technical developments of our advanced industrial age. With satisfying circularity, drawing, a fundamental tool for engineers and architects, scaffolds the level of production which (by guaranteeing surplus product) is the prerequisite for the very existence of our substantial caste of artists and designers, those useless and indispensable dreamers.

Arguably, then, in a perfect world its study might be counted, with literacy and numeracy, as a genuinely key skill to be studied by all. Certainly, perhaps a more realistic demand, it should be a practice both underpinning and overarching any systematic education in art and design. What concrete shape might this take within the Babel of practices which current art education encompasses?

A couple of years ago the two of us, both from a background in digital art/moving image, started teaching on two consecutive courses – a Foundation degree in Digital Art and Design and its top-up, a BA (Hons) degree in Art and Design Practice. Much of the formal documentation of the courses specified the use of particular kinds of software and allegedly real-world reasons for deploying them (many involving the demands of “industry”). From the start we were antagonistic to this approach. We wanted to “artify” the course – introduce as much experimental, speculative, exploratory, pleasurable and downright pointless (in the way that the best art is both pointless and hugely important) activity as possible. We didn’t abandon the idea of teaching design, but we did decide that the core course programme would henceforth be art/design agnostic – it would deal with ways of making and thinking about images (as well as sound, performance, interactions or concepts) that could be used with profit by students moving in either or both or other directions. It would not be training; work would be driven by the imagination and shaped by the ambitions of students. Teachers would introduce new technical processes, but these would be embedded in thematically organised investigations of historic and contemporary precedents. Help with technique or software might be part of what teachers did, but this would be part of an organic investigation/development by student and teacher together. If a teacher knew something they would help; if they didn’t, they might know where to look; if neither knew, they might search together; if the student knew, they could teach other students and the teacher too. In short we identified a peer-learning process as the only sensible approach sufficient for developing the necessary skills, knowledge and flair in a rapidly-developing field.

Moreover we wanted a course that integrated the digital with every other sort of visual (and conceptual, performative and sonic) practice. We were both impatient with the idea that work made using digital tools, or work created within and distributed across a network, was somehow qualitatively different from all that had preceded it (a not uncommon view often allied to a species of digital mysticism). Indeed we realised we both sensed, and gradually came to articulate clearly, that there was a continuum – a chain – from the cave painter to the contemporary artist. Not to say that social and historical concreteness plays no explicatory role, but that there is some still human centre to mark making (and to allied practices – singing, the telling of tales, etc.) which has persisted and will persist and is part of the territory of being human. ’A chain’ is no loose metaphor, but a precise account of the reality. Inspiration and technique pass continuously from generation to generation. And this is cumulative – making much of the past of art available to its future. In a sense the terrain of art accretes, expands, as time passes. Even what is lost to famine or war, proscription, taste and changes in technology leaves traces, the possibility of reconstruction and re-use (and, often most creatively, misuse). This is what we wanted to instil in our students.

Our drawing sessions link to and are inspired by earlier instances of art powered pedagogy that place cross-form conversation at the heart of learning together. Joseph Beuys made drawings throughout his artistic life – often enigmatic constellations of media, concepts, entities, political figurations and material properties. However of particular relevance here are his extended works, Office of the Organization for Direct Democracy by Popular Vote for 100 days at documenta 5, 1972 and Honey Pump in the Workplace for documenta 6 in 1977, in which he demonstrates his expanded notion of art that is exactly congruous with his philosophy of teaching – ‘to reactivate the “life values” through a creative interchange on the basis of equality between teachers and learners.’ [5] Both pieces required the involvement of many people in processes outside of the realms of ordinary action (such as the maintenance of the plastic pipes of the honey pump as it circulated 2 tonnes of honey through the building) in order that they might connect with unfamiliar concepts and experiences. The artworks integrated many different categories of work (some, but not all, associated with art making) including performance and the practice of various disciplines (of dialogue, rhetoric, democratic processes of exchange and decision making). And yet, in an interview with Achille Bonito Oliva, Beuys makes it clear that he has no interest leading audiences towards an “activism devoid of content” [6]. The liberation of humankind through art (Beuys proposes that everyone is an artist and society is to be sculpted by everyone) depends on a more deliberate engagement of individual energies.

Drawing was particularly important to both of us. It was something Ruth had always done from an early age. Collections of drawings made by her between the ages of six and thirteen depict public street scenes of everyday social groupings and activities (a group of kids running with a dog, two mothers with two prams, businessmen waiting for a bus). The figures are too small to carry facial expressions. Nevertheless their interactions, mood, social status and relationships are expressed by their outfits, gaits, their gestures and their proximity to each other and other elements of the scene. Ruth now looks back on these as evidence of an early growing fascination with sociality. Through school she learned that ‘drawing well’ meant producing an image as much like a photograph as one might render. Praise and grades were awarded accordingly. Later, at art school, drawing became a liberating process of discovery. She generated abstract marks, as traces of energies within the body, rather than to create a deliberate composition within a pictorial plane. In this way she produced surfaces such as might be produced by soot covered animals (think monkey, gazelle, seal, tiger, crow) thrown together into a white room. This surface would then serve as a mirror (or crystal ball) from which entities, gestures and forms of light and shadow emerged to be drawn out in further explorations of aspects of her unconscious.

Drawing was something that Michael aspired to. Because he had come to moving image work – to “being an artist” – by a strange route through theatre, maths and music, he had both a fascination with and a terror of drawing. He had been the kid in the class who couldn’t draw, and yet had loved the feeling, the deep engagement with both the act and with what it awoke inside him –his mind’s eye – that it brought. In his moving image work he had attempted to confront this. The inverted commas that came with a certain species of conceptualism were a great help because he could frame himself performatively, comically almost, as an uncertain but oh-so-willing draftsperson, one with no eye or dexterity, a technical schlemiel.

In his secret heart, though, he knew he wanted to do this thing without (or at least largely without) irony.

Arising out of this obsession, in the early years of the new millennium, Michael had launched a little provocation where he challenged digital artists, as they were then still called, to create self-portraits, on the sole condition that this be done using non-digital means, and subsequently to photograph them for display in an online archive. Those who didn’t baulk at the task produced a touching and intriguing panorama, of pen and paint and pencil but also of bathroom tile, egg tempera and iron filings… [7]

As part of a discussion about this Michael had opined on some listserv or other that the barriers between artistic practices were porous and that the true measure of anyone aspiring to be an artist (musician, film maker, poet) was that, if lost in a deep forest or desert isle, with only a rock to make some marks on and another rock to make those marks with, the putative artist would eventually produce something of interest, depth and value.

Early on we introduced chunks of drawing as an occasional workshop – Ruth introduces, and then builds on familiar art school, Bauhaus type exercises that attempt to separate process from outcome-anxiety, allowing students to engage with an inner dialogue about their looking and representation un-disrupted by fears of inadequacy. These include:

drawing without looking at the paper; from memory; without removing pencil from paper; drawing with the “wrong” hand; drawing in five minutes or five seconds; drawing only negative space; having the pencil trace the movement of the eyeball as the drawer observes an object, etc.

Michael felt the centrality of drawing calling him but these sessions still felt like a slightly naughty holiday, an activity that did not necessarily link to his background and formation as an artist. The teacher, like the student, was still exploring.

The big epiphany came with the introduction of a weekly drawing session for all three years of the course. It happened and happens every Monday of term, without fail, and everyone in the room takes part, staff included. As many days as possible where more than one member of staff is present in the room, to make for debate, thus modelling civilised disagreement and forcing students, ultimately, to make up their own minds; there are usually two members of staff and occasionally more present. Each drawing session is led by a student who brings in an object, procedure or puzzle for the rest of us to address.

What happened is that we were rapidly out-Bauhaused by our students. Byzantine sets of instructions for tasks that we as teachers would have rejected out of hand as overly complex, impractical or confusing were carefully explained by students and then carried out by all of us in utter silence.

Half an hour elapses, we place our sets of images on the floor and we process around them all, discussing them. The important thing is that everyone has drawn. Everyone is both vulnerable and admirable. Teachers are not privileged. For students, it is understood that although the process carries course credit, what is being marked eventually is a series of drawings – some “good”, some “bad”, most neither – and that technique – whatever that is – is not the focus. There must be room for play in creative education; hence, for this part of the course, taking part in all of the sessions is enough to secure a pass.

With respect to collective feedback, our experience has been that perceptive kindness predominates. We search for the wonderful things, speculating on why they are wonderful, maybe asking questions of the person who has made this thing, trying to elicit that week’s secret or lesson. The drawings are a pleasure to behold. We have no intention of reproducing any of them here, though many would bear reproduction – we do not want to betray the egalitarian, labouring-together ethos of the thing by selecting outside the sessions and group. We are not sentimentalists – it is precisely because we understand the necessary element of brutality involved in the fair administration of an assessed course that we want to create oases, visions of how things could be other. It is the collective production of shared work that matters – it is not, let us emphasise though, a privileging of “process over production”. The production matters – desperately so. [8]

Over the weeks, our drawings are diverse in category, style, media and technique including: illustrations of the set task, abstractions, naïve figurations, diagrams, signs; some are performances of processes made in pencil, pen, paper, wood, charcoal, paint, collage, arrangements of plastic objects, paper-constructions; they reveal our choices and learning. Some students advance arguments in their drawings either with each other or with their own earlier work. As new tasks are set we each decide in the moment whether we understand the activity we are to involve ourselves with is mundane, ritualistic (perhaps even sacred), mad or wise, pointless or significant – our conclusions shape our drawings. In this way collective drawing has become central to the ethos of our courses as an integrative practice for negotiating a shared studio culture and shaping our learning together, our movement towards collegiality. Doing the drawing means the week has a start to it – we affirm ourselves as folk with a common interest, different but equal. The sessions have helped to provide a social glue, too, across the three years of the course.

There are areas where we as teachers know more than the students; both of us have track records of work in the art world, but the drawing sessions level us all – they enable a mutually supportive but acute look at progress on a common task. Since the drawing started we have also incorporated its lessons to other disciplines; staff and students share their photography work in a more horizontal way than the demands of the course would normally allow. We use new forms of social media, and have Flickr accounts in which all participants are contacts.[9] We comment on and “favourite” each other’s works as equals and collaborators.

Both drawing and photography in these contexts devolve to something similar – filling a blank space by mark making, with valuable, experiential knowledge accrued: repeating processes many times over to find out what constitutes skill and when (often, it turns out, much more often than is often acknowledged) to accept the gifts brought by chance; discovering that the art happens in a social space between the maker, the wider world and the viewer; understanding the work of others because we do it side by side; and, finally, coming to grips with the question of personal style and the diversity of ways of doing things well and meaningfully.

Each week reveals both artistic phylogeny and ontogeny – we solve the problem here and now, as if for the first time ever and this illuminates the historical chain, the intertwining of theory and practice, our mutual dependence, all of us artists and all of us nourished by art too.

—-

Originally written for Drawing Knowledge (2012). Tracey, The Journal of Drawing and Visualisation Research, Loughborough University.

Revised and republished Miller, A & Strong, J. (eds). (2012) Research-Led and Research-Informed Teaching. CREST Publishing.

The insights of American anarchist ecologist Murray Bookchin, into environmental crisis, hinge on a social conception of ecology that problematises the role of domination in culture. His ideas become increasingly relevant to those working with digital technologies in the post-industrial information age, as big business daily develops new tools and techniques to exploit our sociality across high-speed networks (digital and physical). According to Bookchin our fragile ecological state is bound up with a social pathology. Hierarchical systems and class relationships so thoroughly permeate contemporary human society that the idea of dominating the environment (in order to extract natural resources or to minimise disruption to our daily schedules of work and leisure) seems perfectly natural in spite of the catastrophic consequences for future life on earth (Bookchin 1991). Strategies for economic, technical and social innovation that fixate on establishing ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, deployed by fewer, more centralised agents have been shown conclusively to be both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (Jackson 2009). Humanity needs new strategies for social and material renewal and to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values.

In critical media art culture, where artistic and technical cultures intersect, alternative perspectives are emerging in the context of the collapsing natural environment and financial markets; alternatives to those produced (on the one hand) by established ‘high’ art-world markets and institutions and (on the other) the network of ubiquitous user owned devices and corporate social media. The dominating effects of centralised systems are disturbed by more distributed, collaborative forms of creativity. Artists play within and across contemporary networks (digital, social and physical) disrupting business as usual and embedded habits and attitudes of techno-consumerism. Contemporary cultural infrastructures (institutional and technical), their systems and protocols are taken as the materials and context for artistic and social production in the form of critical play, investigation and manipulation.

This essay presents We Won’t Fly for Art, a media art project initiated by artists Marc Garrett and I in April 2009 in which we used online social networks to activate the rhetoric of Gustav Metzger’s earlier protest work Reduce Art Flights (from 2007) in order to reduce art-world-generated carbon emissions... Download full text (pdf- 88Kb) >

Published in PAYING ATTENTION: Towards a Critique of the Attention Economy

Special Issue of CULTURE MACHINE VOL 13 2012 by Patrick Crogan and Samuel Kinsley.

Featured image: Ein Identity-Workshop mit dem britischen Künstler Heath Bunting. Vertiefung Mediale Künste, Sihlquai 131, 8005 Zürich. Dienstag,

Whether Bunting is climbing trees, skateboarding, canoeing or working with technology he approaches it all with the same critical attention. He hacks around systems, physical or digital. Right from when he built his first computer at the age of 14, his life has been an experimental research project. His practice consists of a dry sense of humour and an edgy, minimal-raw aesthetic, mixed with a hyper-awareness of his own artistic persona and agency in the world, whilst engaging with complex political systems, institutions and social contexts.

Even though the subjects he explores are likely to be the most topical or important issues of the day, it always includes playfulness and an element of the prankster in his work. His work regularly highlights issues around infringements on privacy or restriction of individual freedom, as well as contexts concerning the mutation of identity, our values and corporate ownership of our cultural/national ‘ID’s’, as well as our DNA and investigations into Bio-technologies. In an age where we are submersed in frameworks and protocols designed by a neo-liberal elite for a generic consumer class, Bunting’s work is well placed as observation and practical research into the ‘depths’ of legal and illegal territories in our contemporary, networked cultures.

“our identity is constructed as human beings that can possess one or more natural persons and control one or more artificial persons. The higher up in the class system the better the access to status variety.”(Bunting)

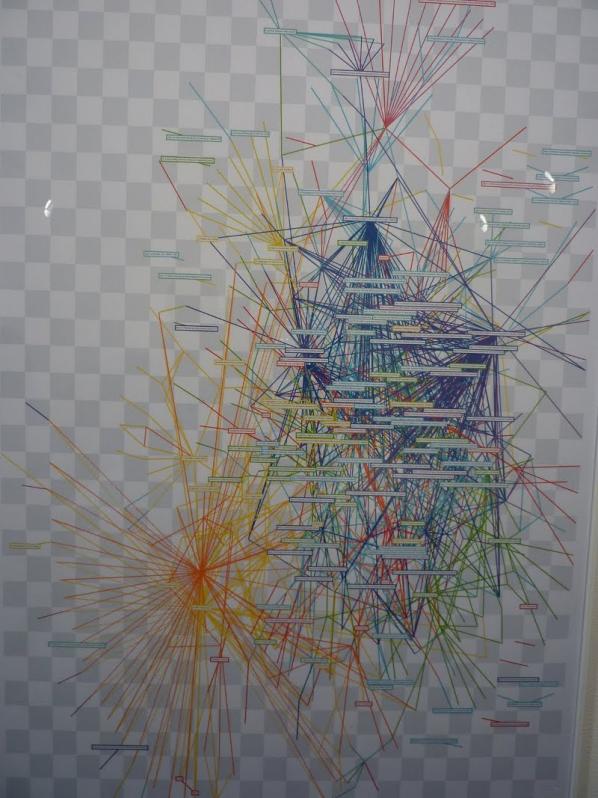

The Status Project, is a study of the construction of our ‘official identities’ and creates what Bunting describes as “…an expert system for identity mutation”. His research explores how information the public supplies in their interaction with organisations and institutions is logged. The project draws on his direct encounters with specific database collection processes and the information he was obliged to supply as a public citizen to access specific services; this includes data collected from the Internet and information found on governmental databases. This data is then used to map and illustrate how we behave, relate, choose things, travel and move around in social spaces. The project surveys individuals locally, nationally and internationally, producing maps of “influence and personal portraits for both comprehension and social mobility”.

The use of data in contemporary life has made individuals an accessible resource for commercial and political interests. We are a rich source of data-mining material. Data mining is a process that potentially commodifies our interactions. Its historical roots lie with the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and 20th Century statistical analysis. These two methods of formulating data have grown ever closer together, backed by corporations and government-initiated military funding. Social networks such as platforms like Facebook and Internet networked institutions such as Google and the US military are all obsessed with our behaviours online. A good example is the NSA’s recent rebirth in turning most of its surveillance apparatus to spy on the US and its citizens. They have built a supercomputer tracing through billions of people’s emails, phone calls, and online activities in other countries outside of the US. The UK government is currently going through the political process of trying to implement similar spying protocols and systems to watch what UK citizens are up to.[2]

“Google suffers from data obesity and is indifferent to calls for careful preservation. It would be naive to demand cultural awareness. The prime objective of this cynical enterprise is to monitor user behaviour in order to sell traffic data and profiles to interested third parties.” [3] (Lovink)

Bunting is a Hacktivist Artist, acting (playing) out the role of a spy collecting and observing data content. Hacktivist Artists work with technology to explore how to develop their critical and imaginative practice in ways beyond the frameworks of the art establishment and its traditions. The established art arena is gradually catching up with this kind of artwork. However, one could be forgiven for thinking that many art critics and galleries are still caught in the 20th Century.

Two other artists also working on people’s data are Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev. They have collaborated on exploring alternative identities as the mysterious group, Men in Grey.[4] They detect online users’ vulnerabilities by tapping into and intervening in wireless network traffic – observing, tracing and copying user online activities. It is then redisplayed online on their website for others to view or transferred onto a visual screen on the side of a briefcase as an intervention in cybercafes for all to view. Although, no one knows other than themselves if the data is hacked and then redisplayed on these briefcases, as proposed in their video featuring one of their interventions. One thing is for sure – they have touched upon issues concerning our fears about personal data being seen by other people who we’d prefer were not viewing it.

The Status Project also taps into questions concerning technology, hierarchy and power. We are entwined in a complex game where the sacrifice of our information is part of connecting with others across digital networks. This raises the issue of our ‘human’ status being aligned ‘to and as’ objects of measurement. Through travel ports, our vehicles, passports, ID cards, library cards, mobile phones, alongside information about our health. We have mutated into networked (information-carrying) beings. Bunting’s own position on this matter is that “Technology is becoming more advanced and the administration of this technology is becoming more sophisticated, and soon, every car in the street will be considered and treated as persons, with human rights. This is not a conspiracy to enslave human beings, and it is a result of having to develop usable administration systems for complex relationships. Slaves were not liberated because their owners felt sorry for them; slaves were given more rights as a way to manage them more productively in a more technologically advanced society.”[5]

In the UK, in 2006 a research document called ‘A Report on the Surveillance Society For the Information Commissioner’ was published. Produced by a group of academics called the Surveillance Studies Network. This report was presented to the 28th International Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners’ Conference in London, hosted by the Information Commissioner’s Office. The publication begins by saying “Conventionally, to speak of surveillance society is to invoke something sinister, smacking of dictators and totalitarianism […] the surveillance society is better thought of as the outcome of modern organizational practices, businesses, government and the military than as a covert conspiracy. Surveillance may be viewed as progress towards efficient administration, in Max Weber’s view, a benefit for the development of Western capitalism and the modern nation-state.”[6]

We are not only under surveillance by entities we do not trust, we are also tracing each other online. Recently, in a show called ‘Being Social'[7] at Furtherfield’s new gallery, artist Liz Sterry showed her installation piece, ‘Kay’s Blog’. Sterry had “collated not only one form of online social engagements but all she could find about a Canadian blogger called Kay. Using everything from photographs to things Kay has mentioned in videos, blogs and posts on social networks, Sterry has recreated Kay’s bedroom in the gallery.”[8] (Scott)

“”There were times when I felt quite creepy,” says Liz, 28, as she shows me lists of Kay’s Facebook friends and a Google Streetview of her apartment block while a playlist of her favourite songs plays in the background.”[9]

Yet, as this ever-creeping surveillance culture grows and attaches its all seeing eyes onto us all. Whether we are referring to domestic interactions, organizational or deliberate, this is not the main issue. Neo-liberalism has developed so much now, we are all part of the Netopticon. English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late Eighteenth Century designed the Panopticon. It allowed officers in institutions, particularly in prisons, to observe (-opticon) all (pan-) inmates without them knowing whether or not they are being watched. In the end it was not built, but the French philosopher Michel Foucault in his publication Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison,[10] in 1975 said that we are not only monitored in prisons, but in all hierarchical structures like the army, schools, hospitals and factories. This process has evolved through history to resemble Bentham’s Panopticon. The up-dated version of Panopticon, can now be thought of as the Netopticon – where individuals are complicit in feeding their own forms of collective co-surveillance, as well as being traced by corporations, governments and spammers.

“What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself. The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world. What we are witnessing at this point in time is the triumph of representation over being. The electronic file has conquered self-aware consciousness.” [11] (Critical Art Ensemble)

So far, for the project he has created a functioning, sketch database of the UK system with over 10,000 entries – made over 50 maps of sub-sections of the system to aid sense of place and potential for social mobility. Bunting says he is also researching how to convert his identity generating software into a bot recognised under UK law as a person “covered by the human rights act i.e. right to life and liberty; freedom of expression; peaceful enjoyment of property. I am very close to achieving this.”

This bring us to another part of the project what I call ‘Identity Kits’, and Bunting calls ‘Synthetic off-the-shelf (OTS) British natural person’.[12] These kits consist of various items, personal business cards, library cards, a national railcard, t-mobile top-up card, national lottery card and much more. They take a few months to compile each of them because they are actual items that everybody uses in their everyday lives, involving evidence of identity. There is also a charge for the package of 500.00 GBP, which is cheap for a new identity.

Bunting stresses that these UK identities are lawful and that there is no need for any official consulting or permission from an authority to use or make them. Through this he intends to illustrate a precise codification of class in the UK system. Currently, he defines three classes of identitiy: human being, person and corporate. What class of individual you are places you into categories of evaluation, this process allows others to judge your status, worth and value, within a hierarchy, which is clearly represented in the status maps.

This work touches on issues around our everyday status as a critique, but also as an investigative hack, and plays around with the quagmire of inequality currently in the UK. Inequality is built, constructed into the fabric our societies as an accepted default, through tradition, social or mechanistic, holding in place societal divisions. If there was a status project made in other countries reflecting their own status, worth and value of citizens there would be clear links defining where the connections and divisions lie, between each culture. In fact, another project worth mentioning here is ‘The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better’. [13] The authors Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have done their own ‘extensive’, detailed research in highlighting through many different graphs, mapping out inequality around ther globe.

“We know there is something wrong, and this book goes a long way towards explaining what and why.” [14] (Hanley)

Bunting’s work expresses a discipline conscious of agency, autonomy and enactments for self and collective empowerment. Hacking different routes around what at first is seen as too big to deal with, lessens its power and awe. Like Burbank in the ‘The Truman Show’, what we have been told is not real. Bunting knows this instinctively, and is on a quest to upturn each stone to see what lies beneath. But at the same time these facilities created to crack the social, and data orientated codes, are shared. He then leaves the paths he has discovered wide open for others pass through, as we all struggle to survive the ever creeping strangle-hold, of the Netopticon.

———————————————————————-

This article was written for and will be published as part of Heath Bunting’s presentation in Athens ‘Workshop How to Build a New Legal Identity’, May 5th 2012.

During the workshop, Heath Bunting will introduce us to techniques and strategies on how to form new identities. The distribution of the workshop How to Build a New Legal Identity across Europe aims at exploring the characteristics of identity in each country.

Artist’s Talk: May 4, 2012 @ 19.00

Workshop How to Build a New Legal Identity: May 5, 2012 @ 12.00

Frown Tails, 6 Paramythias str, Keramikos, Athens

Organised by: Katerina Gkoutziouli and Frown Tails

It’s a bizarre thing when you stumble upon the “new art movement” filtering through discursive chatter. Is it actually a movement, or is it simply a bunch of like-minded individuals telling me its a movement?

Behold The New Aesthetic then – a new art meme in visual culture whimsically constructed by James Bridle, which manifests itself in a Tumblr blog, a presentation for Web Directions South, Sydney and an original blog post. Recent attention to it has reached feverish proportions coming off the back of a SXSW panel in March and a generally positive endorsement by Bruce Sterling in Wired, plus some group responses on the creators project. More recently, the computational media scholar and philosopher Ian Bogost has posted his own thoughts for The Atlantic.

As a meme should do, “the New Aesthetic” has fulfilled its role – it has a lot of people talking about it. Like any meme which dices visual culture with some sort of research element, it has artists, writers, even media and aesthetic scholars measuring their own opinions on it in rank order without anyone knowing exactly where it’s going, what it really is or who exactly is doing it. In our noisy and crowded “I can’t believe I got 50+ retweets” over-networked epoch, this is quite an achievement even if you don’t take it that seriously.

But here’s the question: can the new aesthetic be more than a meme? More to the point, does it want to be? Is it capable of a direction? Can it be serious?

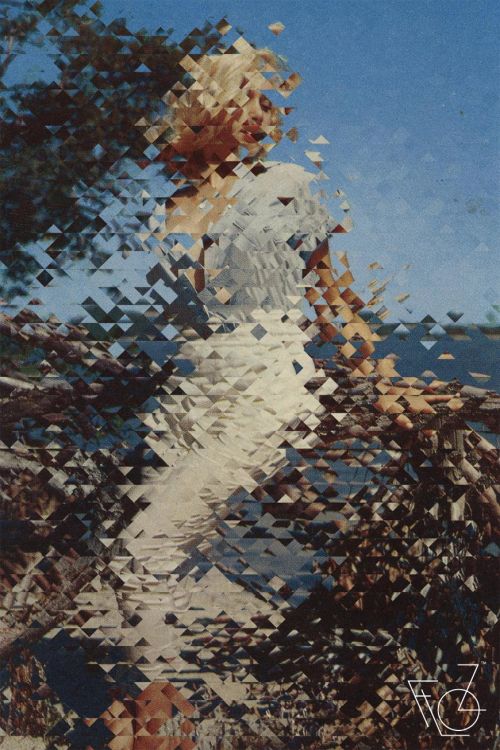

That said (and as Bridle avers) this isn’t really a prominent “movement” of ideas as such. Neither does it present material which it would deem ‘arty’. Instead, it’s an extremely broad and oblique orientation which seeks to document the subtle (and sometimes explicit) changes within our information saturated existence. It simply contextualises the contingent manifestations of computational activity, and how they are reversing and revising computational and human activities back in on themselves. Bridle’s tumblr simply presents the new aesthetic for what it is, much akin to perusing through pictures in a Facebook profile, a Reddit top ten list or clicking on Stumbleupon – simple snapshots of “stuff” which echo a blurring between the world of networks, machines and everything outside of it (with a particular emphasis on where it goes a bit wrong, hence a certain infatuation with glitchyness). Quoting Bridle’s Tumblr page;

“It is a series of artefacts of the heterogeneous network, which recognises differences, the gaps in our overlapping but distant realities.”

In another video presentation ‘We fell in love in a coded space‘ at Lift12, Bridle terms this ‘network realism’ – instances where the amalgamation of computational networked activity blurs with non-computational activity, to such an extent that it reduces any observer to nothing but a curious, passive node, gleefully whittling through instances of vaguely creative stuff. For Bridle, this occurs not just in industry but also architecture, finance, storage, fashion and now an attempt at aesthetic understanding. It’s an infatuation with the alterity of bots, algorithms, pixels and realised fictions. In this presentation however, Bridle is largely concerned with how one can respond or understand the ‘desires’ of bots, unaware that anthropomorphising the situation may not reap the rewards required. In this interpretation the new aesthetic is charged with the task of asking how we can think and orient ourselves computationally, whether it be designers, thinkers, writers, scholars or artists.

Sterling himself, mostly issues praise with a pinch of amusing impatience, as if the New Aesthetic movement should progress faster than it actually is doing, with more ideas and more focus. Kyle Chayka states that artists are already embracing it as a ‘contextual seedbed, rather than a label’. Jonathan Minard understands it as a new method of reflection concerning cultural tool-making, where the ‘dumb tools’ of machinic interface scream images back at us.

Digital Humanities scholar David Berry has blogged a similar view echoing that the new aesthetic is tapping into what he calls ‘Computationality’, a historical paradigm frame-making of sorts, which constructs specific meaning-making practices. Visualisation revolves around processes and patterns and so the list making exercise of Bridles’s Tumblr blog would seem apt in this regard, as it issues unparalleled amounts of pattern making not just as content, but as form. The archive is a jamboree of other pattern recognising events; security face recognition, retro 8bit encapsulation, satellite visuals and generally messing about with an Xbox 360 Kinect. James George mentions something similar but suggests that the new aesthetic should question the critical distance between artistic activity and technological use. It resembles a massive screen dump from a digital artist’s delicious account. Quoting Bridle again in an interview with The Design Observer Group;

“The New Aesthetic is not criticism, but an exploration; not a plea for change, rather a series of reference points to the change that is occurring. An attempt to understand not only the ways in which technology shapes the things we make, but the way we see and understand them.”

To most of the established readers here, it’s easy to criticise the “newness” of the New Aesthetic, in the same way the 90’s trope “New Media” has been quickly bundled away as if it never existed (Marius Watz makes this point). For those of you who have been studying such issues concerning hacking, play, enumeration, collecting, remixing, glitch-ing, (see Rosa Menkman in particular) in the broader realm of the computational arts, there really isn’t anything novel to gawk at: this is more of a rearrange or a rebadge. Indeed, internet discussion has been rife with such criticism, from the triteness of using Tumblr as the ‘official site’, to quick dismissals concerning the New Aesthetic’s distinct lack of any historically serious ‘substantial practice’ – not that it wanted it in the first place (Indeed it’s a pity that it has contingently replaced an identical term for a movement unrelated to Bridle’s own, coined by arts writer Michael Paraskos and realist artist Clive Head. Moreover, depending on how one looks at it, Paraskos and Head’s own movement has similar views espoused by Bridle’s version, including perhaps a direct opposition to conceptualism and foregrounding art as a material practice).

If Bridle were not so sincere about the whole affair, one would be mistaken that this was a too-cool-for-school strategy straight out of a Nathan Barley episode. But thats an easy misread. As Bogost states, Bridle is just curious about the weirdness of the network we all rely on and revel in. But there is a point where fascination with creativity turns into ADHD. The New Aesthetics tumblr site, already does just that, without any hint of standing still. “What’s going to come next? What can we do next? What are the limitations? What happens if I click that? What is that doing there?”

However both Bogost and Greg Borenstein issue a different view about the new aesthetic. They both discuss it in relation to a recent trend in philosophy called Object Oriented Ontology (OOO), a movement to which I am extremely sympathetic to. Bogost explains OOO succinctly enough;

“If ontology is the philosophical study of existence, then object-oriented ontology puts things at the center of being. We humans are elements, but not the sole elements of philosophical interest. OOO contends that nothing has special status, but that everything exists equally–plumbers, cotton, bonobos, DVD players, and sandstone, for example. OOO steers a path between scientific naturalism and social relativism, drawing attention to things at all scales and pondering their nature and relations with one another as much as ourselves.”

The link to OOO is fairly self-evident. If one of the most prominent aspects of the new aesthetic is an obsession with how a machine “sees” the world, OOO is a commitment to the seeing of things in widest possible sense. But while Borenstein generally aligns OOO to the new aesthetic with exuberant equivalence, Bogost’s view is one of general optimism, but not broad acceptance. For a start, the new aesthetics is based on a continual divide and repair between two opposing realms; the physical and the digital, each coming together and breaking apart endlessly, like throwing a box of magnets.

One of the main stipulations of being an OOO advocate is the realist eruption of what counts as a thing, and how that thing contingently relates to different types of entities. This is why Bogost decenters computation in the new aesthetic, and emphasises the multitude of things that escape the physical/digital divide. Their adventures are always-already strewn across the ontological landscape. One of the other main stipulations involves us lacking secure knowledge in fully understanding discrete units on their own terms – we can never experience their being in the same way we experience our being.

If one has read Bogost’s latest publication, Alien Phenomenology (and if you haven’t, I’d urge you to do so immediately), one would understand Bogost’s view that the new aesthetics misses out not just speculating on the hidden lives of objects other than computers and humans, but it also hovers on the inescapable problem of anthropomorphising machines and objects to within an inch of their lives. The alien aesthetics challenge is provocative.

“[T]his Alien Aesthetics would not try to satisfy our human drive for art and design, but to fashion design fictions that speculate about the aesthetic judgments of objects. If computers write manifestos, if Sun Chips make art for Doritos, if bamboo mocks the bad taste of other grasses–what do these things look like? Or for that matter, when toaster pastries convene conferences or write essays about aesthetics, what do they say, and how do they say it?”

There is an interesting discussion to be had in OOO about the usefulness of anthropomorphising the infinitesimal non-human relationships between the properties of things. Whilst others (including Bogost) see it as an inevitable factor of being one finite human entity amongst a crowd of other finite entities, I see it as a hinderance.

In particular, I’m interested in the way the new aesthetic never manages to access computation ‘just’ as it is. It only takes computation seriously when it functions as a qualitatively intelligent system, which meets or surpasses rational intelligence, or, it directly flips into “dumb tools” of (mis)communicative manipulation for the whims of human mental acts.

But I digress. Last year Bridle released a book called “Where the F**k Was I?”, which accurately sums up the mentality of the movement. The really interesting element of the new aesthetic is that it presents genuinely interesting stuff, but Bridle’s delivery strategy is set to ‘gushing disorientation’. At present, it’s the victim of the compulsive insular network it feeds off from. It presents little engagement with the works themselves instead favouring bombardment and distraction. Under these terms, aesthetics only leads to a banal drudgery, where everything melts together into a depthless disco. Any depth to the works themselves are forgotten.

Memes require instant satisfaction. Art requires depth.

“At the dawn of the new millennium, Net users are developing a much more efficient and enjoyable way of working together: cyber-communism.” Richard Barbrook.

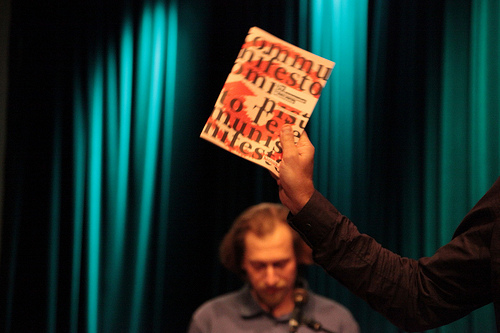

Dmytri Kleiner, author of The Telekommunist Manifesto, is a software developer who has been working on projects “that investigate the political economy of the Internet, and the ideal of workers’ self-organization of production as a form of class struggle.” Born in the USSR, Dmytri grew up in Toronto and now lives in Berlin. He is a founder of the Telekommunisten Collective, which provides Internet and telephone services, as well as undertakes artistic projects that explore the way communication technologies have social relations embedded within them, such as deadSwap (2009) and Thimbl (2010).

“Furtherfield recently received a hard copy of The Telekommunist Manifesto in the post. After reading the manifesto, it was obvious that it was pushing the debate further regarding networked, commons-based and collaborative endeavours. It is a call to action, challenging our social behaviours and how we work with property and the means of its production. Proposing alternative routes beyond the creative commons, and top-down forms of capitalism (networked and physical), with a Copyfarleft attitude and the Telekommunist’s own collective form of Venture Communism. Many digital art collectives are trying to find ways to maintain their ethical intentions in a world where so many are easily diverted by the powers that be, perhaps this conversation will offer some glimpse of how we can proceed with some sense of shared honour, in the maelstrom we call life…”

Marc Garrett: Why did you decide to create a hard copy of the Manifesto, and have it republished and distributed through the Institute of Networked Cultures, based in Amsterdam?

Dmytri Kleiner: Geert Lovink contacted me and offered to publish it, I accepted the offer. I find it quite convenient to read longer texts as physical copies.

MG: Who is the Manifesto written for?

DK: I consider my peers to be politically minded hackers and artists, especially artists whose work is engaged with technology and network cultures. Much of the themes and ideas in the Manifesto are derived from ongoing conversations in this community, and the Manifesto is a contribution to this dialogue.

MG: Since the Internet we have witnessed the rise of various networked communities who have explored individual and shared expressions. Many are linked, in opposition to the controlling mass systems put in place by corporations such as Facebook and MySpace. It is obvious that your shared venture critiques the hegemonies influencing our behaviours through the networked construct, via neoliberal appropriation, and its ever expansive surveillance strategies. In the Manifesto you say “In order to change society we must actively expand the scope of our commons, so that our independent communities of peers can be materially sustained and can resist the encroachments of capitalism.” What kind of alternatives do you see as ‘materially sustainable’?

DK: Currently none. Precisely because we only have immaterial wealth in common, and therefore the surplus value created as a result of the new platforms and relationships will always be captured by those who own scarce resources, either because they are physically scarce, or because they have been made scarce by laws such as those protecting patents and trademarks. To become sustainable, networked communities must possess a commons that includes the assets required for the material upkeep of themselves and their networks. Thus we must expand the scope of the commons to include such assets.

MG: The Manifesto re-opens the debate around the importance of class, and says “The condition of the working class in society is largely one of powerlessness and poverty; the condition of the working class on the Internet is no different.” Could you offer some examples of who this working class is using the Internet?

DK: I have a very classic notion of working class: Anyone whose livelihood depends on their continuing to work. Class is a relationship. Workers are a class who lack the independent means of production required for their own subsistence, and thus require wage, patronage or charity to survive.

MG: For personal and social reasons, I wish for the working class not to be simply presumed as marginalised or economically disadvantaged, but also engaged in situations of empowerment individually and collectively.

DK: Sure, the working class is a broad range of people. What they hold in common is a lack of significant ownership of productive assets. As a class, they are not able to accumulate surplus value. As you can see, there is little novelty in my notion of class.

MG: Engels reminded scholars of Marx after his death that, “All history must be studied afresh”[1]. Which working class individuals or groups do you see out there escaping from such classifications, in contemporary and networked culture?

DK: Individuals can always rise above their class. Many a dotCom founder have cashed-in with a multi-million-dollar “exit,” as have propertyless individuals in other fields. Broad class mobility has only gotten less likely. If you where born poor today you are less likely than ever to avoid dying poor, or avoid leaving your own children in poverty. That is the global condition.

I do not believe that class conditions can be escaped unless class is abolished. Even though it is possible to convince people that class conditions do not apply anymore by means of equivocation, and this is a common tactic of right wing political groups to degrade class consciousness. However, class conditions are a relationship. The power of classes varies over time, under differing historical conditions.

The condition of a class is the balance of its struggle against other classes. This balance is determined by its capacity for struggle. The commons is a component of our capacity, especially when it replaces assets we would otherwise have to pay Capitalist-owners for. If we can shift production from propriety productive assets to commons-based ones, we will also shift the balance of power among the classes, and thus will not escape, but rather change, our class conditions. But this shift is proportional to the economic value of the assets, thus this shift requires expanding the commons to include assets that have economic value, in other words, scarce assets that can capture rent.

MG: The Telekommunist Manifesto, proposes ‘Venture Communism’ as a new working model for peer production, saying that it “provides a structure for independent producers to share a common stock of productive assets, allowing forms of production formerly associated exclusively with the creation of immaterial value, such as free software, to be extended to the material sphere.” Apart from the obvious language of appropriation, from ‘Venture Capitalism’ to ‘Venture Communism’. How did this idea come about?

DK: The appropriation of the term is where it started.

The idea came about from the realization that everything we were doing in the free culture, free software & free networks communities was sustainable only when it served the interests of Capital, and thus didn’t have the emancipatory potential that myself and others saw in it. Capitalist financing meant that only capital could remain free, so free software was growing, but free culture was subject to a war on sharing and reuse, and free networks gave way to centralized platforms, censorship and surveillance. When I realized that this was due to the logic of profit capture, and precondition of Capital, I realized that an alternative was needed, a means of financing compatible with the emancipatory ideals that free communication held to me, a way of building communicative

infrastructure that was born and could remain free. I called this idea Venture Communism and set out to try to understand how it might work.

MG: An effective vehicle for the revolutionary workers’ struggle. There is also the proposition of a ‘Venture Commune’, as a firm. How would this work?

DK: The venture commune would work like a venture capital fund, financing commons-based ventures. The role of the commune is to allocate scarce property just like a network distributes immaterial property. It acquires funds by issuing securitized debt, like bonds, and acquires productive assets, making them available for rent to the enterprises it owns. The workers of the enterprises are themselves owners of the commune, and the collected rent is split evenly among them, this is in addition to whatever remuneration they receive for work with the enterprises.

This is just a sketch, and I don’t claim that the Venture Communist model is finished, or that even the ideas that I have about it now are final, it is an ongoing project and to the degree that it has any future, it will certainly evolve as it encounters reality, not to mention other people’s ideas and innovations.

The central point is that such a model is needed, the implementation details that I propose are… well, proposals.

MG: So, with the combination of free software, free code, Copyleft and Copyfarleft licenses, through peer production, does the collective or co-operative have ownership, like shares in a company?

DK: The model I currently support is that a commune owns many enterprises, each independent, so the commune would own 100% of the shares in each enterprise. The workers of the enterprises would themselves own the commune, so there would be shares in the commune, and each owner would have exactly one.

MG: In the Manifesto, there is a section titled ‘THE CREATIVE ANTI-COMMONS’, where the Creative Commons is discussed as an anti-commons, peddling a “capitalist logic of privatization under a deliberately misleading name.” To many, this is a controversy touching the very nature of many networked behaviours, whether they be liberal or radical minded. I am intrigued by the use of the word ‘privatization’. Many (including myself) assume it to mean a process whereby a non-profit organization is changed into a private venture, usually by governments, adding extra revenue to their own national budget through the dismantling of commonly used public services. Would you say that the Creative Commons, is acting in the same way but as an Internet based, networked corporation?

DK: As significant parts of the Manifesto is a remix of my previous texts, this phrase originally comes from the longer article “COPYRIGHT, COPYLEFT AND THE CREATIVE ANTI-COMMONS,” written by me and Joanne Richardson under the name “Ana Nimus”:

http://subsol.c3.hu/subsol_2/contributors0/nimustext.html

What we mean here is that the creative “commons” is privatized because the copyright is retained by the author, and only (in most cases) offered to the community under non-commercial terms. The original author has special rights while commons users have limited rights, specifically limited in such a way as to eliminate any possibility for them to make a living by employing this work. Thus these are not commons works, but rather private works. Only the original author has the right to employ the work commercially.

All previous conceptions of an intellectual or cultural commons, including anti-copyright and pre-copyright culture as well as the principles of free software movement where predicated on the concept of not allowing special rights for an original author, but rather insisting on the right for all to use and reuse in common. The non-commercial licenses represent a privatization of the idea of the commons and a reintroduction of the concept of a uniquely original artist with special private rights.

Further, as I consider all expressions to be extensions of previous perceptions, the “original” ideas that rights are being claimed on in this way are not original, but rather appropriated by the rights-claimed made by creative-commons licensers. More than just privatizing the concept and composition of the modern cultural commons, by asserting a unique author, the creative commons colonizes our common culture by asserting unique authorship over a growing body of works, actually expanding the scope of private culture rather than commons culture.

MG: So, this now brings us to Thimbl, a free, open source, distributed micro-blogging platform, which as you say is “similar to Twitter or identi.ca. However, Thimbl is a specialized web-based client for a User Information protocol called Finger. The Finger Protocol was orginally developed in the 1970s, and as such, is already supported by all existing server platforms.” Why create Thimbl? What kind of individuals and groups do you expect to use it, and how?

DK: First and foremost Thimbl is an artwork.

A central theme of Telekommunisten is that Capital will not fund free, distributed platforms, and instead funds centralized, privately owned platforms. Thimbl is in part a parody of supposedly innovative new technologies like twitter. By creating a twitter-like platform using Finger, Thimbl demonstrates that “status updates” where part of network culture back to the 1970s, and thus multimillion-dollar capital investment and massive central data centers are not required to enable such forms of communication, but rather are required to centrally control and profit from them.

MG: In a collaborative essay with Brian Wyrick, published on Mute Magazine ‘InfoEnclosure-2.0’, you both say “The mission of Web 2.0 is to destroy the P2P aspect of the Internet. To make you, your computer, and your Internet connection dependent on connecting to a centralised service that controls your ability to communicate. Web 2.0 is the ruin of free, peer-to-peer systems and the return of monolithic ‘online services’.”[2] Is Thimbl an example of the type of platform that will help to free-up things, in respect of domination by Web 2.0 corporations?

DK: Yes, Thimbl is not only a parody, it suggests a viable way forward, extending classic Internet platforms instead of engineering overly complex “full-stack” web applications. However, we also comment on why this road is not more commonly taken, because “The most significant challenge is not technical, it is political.” Our ability to sustain ourselves as developers requires us to serve our employers, who are more often than not funded by Capital and therefore are primarily interested in controlling user data and interaction, since delivering such control is a precondition of receiving capital in the first place.

If Thimbl is to become a viable platform, it will need to be adopted by a large community. Our small collective can only take the project so far. We are happy to advise any who are interested in how to join in. http://thimbl.tk is our own thimbl instance, it “knows” about most users I would imagine, since I personally follow all existing Thimbl users, as far as I know, thus you can see the state of the thimblsphere in the global timeline.

Even if the development of a platform like Thimbl is not terribly significant (with so much to accomplish so quickly), the value of a social platform is the of course derived from the size of it’s user base, thus organizations with more reach than Telekommunisten will need to adopt the platform and contribute to it for it to transcend being an artwork to being a platform.

Of course, as the website says “the idea of Thimbl is more important than Thimbl itself,” we would be equally happy if another free, open platform extending classic Internet protocols where to emerge, people have suggested employing smtp/nntp, xmmp or even http/WebDav instead of finger, and there are certain advantages and disadvantages to each approach. Our interest is the development of a free, open platform, however it works, and Thimbl is an artistic, technical and conceptual contribution to this undertaking.

MG: Another project is the Telekommunisten Facebook page, you have nearly 3000 fans on there. It highlights the complexity and contradictions many independents are faced with. It feels as though the Internet is now controlled by a series of main hubs; similar to a neighbourhood being dominated by massive superstores, whilst smaller independent shops and areas are pushed aside. With this in mind, how do you deal with these contradictions?

DK: I avoided using Facebook and similar for quite some time, sticking to email, usenet, and irc as I have since the 90s. When I co-authored InfoEnclosure 2.0, I was still not a user of these platforms. However it became more and more evident that not only where people adopting these platforms, but that they were developing a preference for receiving information on them, they would rather be contacted there than by way of email, for instance. Posting stuff of Facebook engaged them, while receiving email for many people has become a bother. The reasons for this are themselves interesting, and begin with the fact that millions where being spent by Capitalists to improve the usability of these platforms, while the classic Internet platforms were more or less left as they were in the 90s. Also, many people are using social media that never had been participants in the sorts of mailing lists, usenet groups, etc that I was accustomed to using to share information.

If I wanted to reach people and share information, I needed to do so on the technologies that others are using, which are not necessarily the ones I would prefer they use.

My criticism of Facebook and other sites is not they are not useful, it is rather that they are private, centralized, proprietary platforms. Also, simply abstaining from Facebook in the name of my own media purity is not something that I’m interested in, I don’t see capitalism as a consumer choice, I’m more interested in the condition of the masses, than my own consumer correctness. In the end it’s clear that criticizing platforms like Facebook today means using those platforms. Thus, I became a user and set up the Telekommunisten page. Unsurprisingly, it’s been quite successful for us, and reaches a lot more people than our other channels, such as our websites, mailing lists, etc. Hopefully it will also help us promote new decentralized channels as well, as they become viable.

MG: So, I downloaded deadSwap (http://deadSwap.net) which I intend to explore and use. On the site it says “The Internet is dead. In order to evade the flying monkeys of capitalist control, peer communication can only abandon the Internet for the dark alleys of covert operations. Peer-to-peer is now driven offline and can only survive in clandestine cells.” Could you explain the project? And are people using it as we speak?

DK: I have no idea if people are using it, I am currently not running a network.

Like thimbl, deadSwap is an artwork. Unlike thimbl, which has the seeds of a viable platform within it, deadSwap is pure parody.

It was developed for the 2009 Sousveillance Conference, The Art of Inverse Surveillance, at Aarhus University. deadSwap is a distopian urban game where participants play secret agents sharing information on usb memory sticks by hiding them in secret locations or otherwise covertly exchanging them, communicating through an anonymizing SMS gateway. It is a parody of the “hacker elite” reaction to Internet enclosure, the promotion of the idea that new covert technologies will defeat attempts to censor the Internet, and we can simply outsmart and outmaneuver those who own and control our communications systems with clandestine technologies. This approach often rejects any class analysis out-of-hand, firmly believing in the power of us hackers to overcome state and corporate repressions. Though very simple in principal, deadSwap is actually very hard to use, as the handbook says “The success of the network depends on the competence and diligence of the participants” and “Becoming a super-spy isn’t easy.”

MG: What other services/platforms/projects does the Telekommunisten collective offer the explorative and imaginative, social hacker to join and collaborate with?

DK: We provide hosting services which are used by individuals and small organizations, especially by artists, http://trick.ca, electronic newsletter hosting (http://www.freshsent.info) and a long distance calling service (http://www.dialstation.com). We can often be found on IRC in#telnik in freenode. Thimbl will probably be a major focus for us, and anybody that wants to join the project is more than welcome, we have a community board to co-ordinate this which can be found here: http://www.thimbl.net/community.html

For those that want to follow my personal updates but don’t want don’t use any social media, most of my updates also go here: http://dmytri.info

Thank you for a fascintaing conversation Dmytri,

Thank you Marc 🙂

=============================<snip>

Top Quote: THE::CYBER.COM/MUNIST::MANIFESTO by Richard Barbrook. http://www.imaginaryfutures.net/2007/04/18/by-richard-barbrook/

The Foundation for P2P Alternatives proposes to be a meeting place for those who can broadly agree with the following propositions, which are also argued in the essay or book in progress, P2P and Human Evolution. http://blog.p2pfoundation.net

In the essay ‘Imagine there is no copyright and no cultural conglomerates too…” by Joost Smiers and Marieke van Schijndel, they say “Once a work has appeared or been played, then we should have the right to change it, in other words to respond, to remix, and not only so many years after the event that the copyright has expired. The democratic debate, including on the cutting edge of artistic forms of expression, should take place here and now and not once it has lost it relevance.”

Issue no. 4 Joost Smiers & Marieke van Schijndel, Imagine there are is no copyright and no cultural conglomorates too… Better for artists, diversity and the economy / an essay. colophon: Authors: Joost Smiers and Marieke van Schijndel, Translation from Dutch: Rosalind Buck, Design: Katja van Stiphout. Printer: ‘Print on Demand’. Publisher: Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam 2009. ISBN: 978-90-78146-09-4.

http://networkcultures.org/wpmu/theoryondemand/titles/no04-imagine-there-are-is-no-copyright-and-no-cultural-conglomorates-too/