Referring to Ernst Jünger’s proto-fascist concept of the ‘front experience,’ Dani Ploeger’s fronterlebnis takes us to a frontline where digital consumer culture and traditional warfare meet. Combining filmed footage of a journey to the frontline in the Donbass War, Ukraine, alongside vintage military paraphernalia, Ploeger puts the artist in the field with the ‘real’ soldier. These soldiers are men from the far-right Ukraine Volunteer Corps, affiliated with the Right Sector, and remind Ploeger of ‘the weird and wonderful mix of action heroes in Sylvester Stallone’s Expendables series, albeit without the body builder physiques and less carefully manicured.’ Here, Ploeger not only conceives an exhibition which examines the relationship between the cleanliness of modern day technology and the grittiness of traditional warfare, but also highlights wider issues around society’s continued masculinised and fetishised relationship to conducting, and, as some of these pieces show, documenting war. With Ploeger’s ‘weird and wonderful’ group made up exclusively of men, featuring masculine nom de guerres such as Bear and Carpenter, fronterlebnis is an exhibition in which masculinity is in the crosshairs as much as anything else.

The four-piece exhibition is part of Ploeger’s current exploration into the militarisation of public spaces across Western Europe in connection with our increasingly fetishised relationship with consumer technologies, and how these apparently disparate elements converge in various conflicts, ranging from the Donbass War to public security in cities like Brussels and Paris. The soldier’s body has arguably shifted in its role since the latter part of the 20th century, with the advent of sophisticated warfare technologies moving the human body away from the process of killing, at least in popular imaginations of conflict. With this development, the methods of war appear to have shifted, but it is in fronterlebnis that we are able to see how in the Donbass War in Ukraine, traditional warfare not only remains but has now become intertwined with advanced techno-consumer culture.

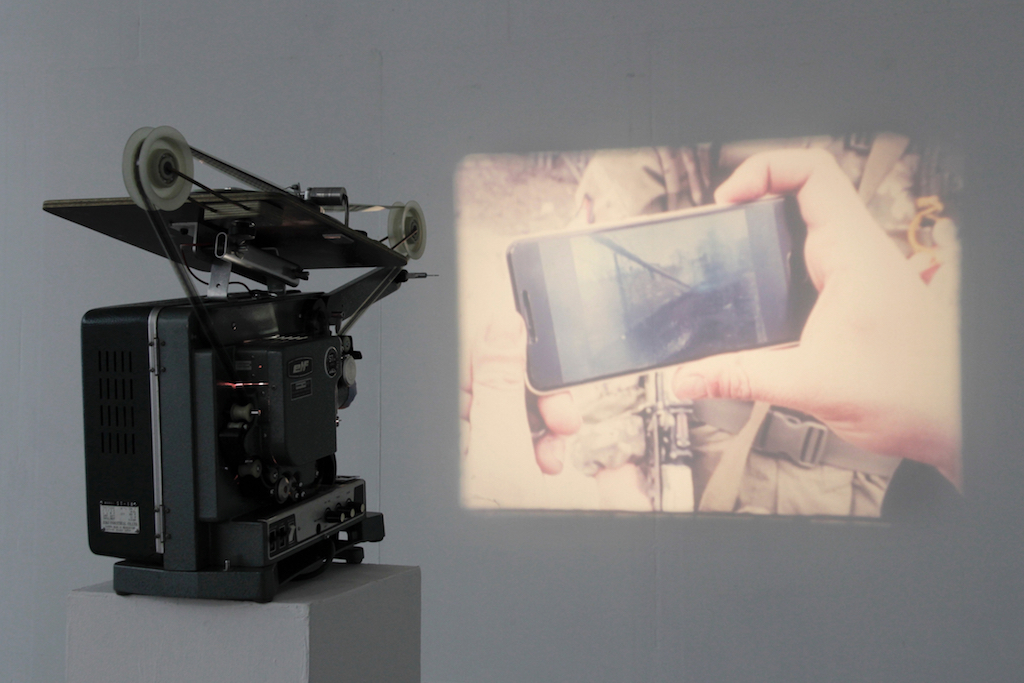

This juxtaposition of the old and new is present in the first piece you encounter as you enter the gallery. In Patrol (2017), Ploeger captured a firefight on his smartphone. The footage has been transferred to 16mm film and is being projected onto the wall of the gallery in a continuous loop. In the film, we see three soldiers – Bear, Carpenter and Steinar – escort Ploeger around the frontline on the edge of the destroyed seaside village, Shyrokyne. These men, in an assortment of vintage and contemporary battle array, many carrying the iconic Kalashnikov rifle, are seen sharing footage of their exploits on the frontline with each other, which they have captured on their smartphones and GoPros. Steinar, the youngest and, as Ploeger told me, the most fashion conscious in his choice of military gear, is filmed by Ploeger watching footage of the moment where he and Carpenter blow up an unexploded mortar shell. In this piece, the 16mm film echoes the era of the weapons that the men are carrying. The manner in which this film is projected reveals the peculiarity of watching a modern day firefight where many of the weapons and uniforms are from the Soviet era, but the men are astute in their engagement of consumer technology in order to document their experiences of the conflict. In Patrol, the Kalashnikov and the smartphone appear to have made an unlikely pairing.

The other work in the show features such seemingly unlikely pairings of traditional paraphernalia of warfare coupled with different pieces of consumer technology. In artefact (2017), the wooden handguard of a Kalashnikov assault rifle is exhibited like an archaeological artefact. Presented on a white plinth, encased in Perspex glass, you can see that the wood of the handguard has been worn with the indents of many hands, signalling its intense use. This carefully exhibited object is just one half of this piece though. The other half consists of digital video animation in which a high-resolution 3D scan of the handguard is inserted onto a digital model of an AK-47. Presented on a large television screen, the digital model, set against a standard blue sky backdrop reminiscent of game development engines, highlights how many of us only come into contact with these types of weapons in a digitised form; whether that be in video games or through action movies. Ploeger’s engagement with firearms here reminds me of some of his past work that seems to suggest an interest in these weapons in relation to masculinity and phallic imagery. Dead Ken /Less Pink (2016), a short video installation in which Ploeger fires a small revolver at a Ken doll, speaks to the seemingly indelible relationship between firearms and masculinity. When seen in relation to this video installation, artefact signals an enduring fascination in our shared social psyche with these weapons, but also speaks to how these weapons continue to be consumed and represented in relation to masculine identities.

In worse than the quick hours of open battle, was this everlasting preparedness (2017), we can see a more tangible engagement with the co-existence of war artefacts and digital technology. Held in the front pocket of a Soviet army backpack from the Afghanistan War period is a damaged tablet computer which displays a bouncing screensaver, featuring a piece of text from Ernst Jünger’s proto-fascist novel Storm of Steel (1920). Jünger describes his experiences of fighting on the frontline during the First World War and the title of this piece is a translation of the text we see displayed on the tablet. Here, the mediatised depictions of war that are so pervasive in popular culture are delineated from the lived experience of Jünger, who discusses this perennial notion of prepared waiting that is a common, though rarely shown, aspect of war. Here, the worn backpack which has been roughly patched and repaired, presumably by the hands of the man to which it used to belong (men’s hands are for holding guns rather than sewing needles this bag appears to suggest), holds the similarly worn and damaged tablet. These damaged items speak to Ploeger’s past work with electronic waste, which explored our society’s proclivity for abandoning technologies when they become outdated or damaged. In this exhibition, however, Ploeger brings together the old and new, using pieces of (almost) electronic waste alongside other material artefacts to further explore the relationship between the material and digital.

The largest piece of the exhibition, frontline (2016-17), deploys this new and ‘clean’ technology in order to take us to the frontline. The work consists of a big wooden enclosure of about 5 by 5 meters which can be entered through a small opening on its side. The entirely white inside of the space is brightly lit by a large grid of office LED lighting that hangs above it. This enclosed space speaks to the ways in which Westernised notions of conducting war are now considered clean and sterile as a result of the technology that they use. Before entering the space, you are asked to place foot coverings over your shoes, as if you would be entering a sterile space, a futile gesture it would seem as the same coverings are used again and again. This action, however, also references the cultural shift in how Western nations like to represent high-tech warfare as a clean affair.

When you enter the enclosure a sensor is triggered and a soundscape of intense gunfire and explosions suddenly surrounds you. It is only until the you place the VR headset on to your eyes that this soundtrack, fit for an action movie, ceases. Roused by the noise, you are then met with a starkly contrasted image to what was suggested through the preceding gunfire soundscape. Rather than an action scene which complements the sounds previously heard, you enter an uneventful immersive video of soldiers smoking and sitting on the frontline. Using an intricate combination of partial video loops, the men appear to be on a never ending smoking break. frontline, subverts our spectacular expectations of warfare and VR technology by creating a VR experience that – after using sound to further heighten our expectations – foregrounds the mundanity of waiting for something to happen that makes up most of everyday life in an area of conflict.

In frontline, as in all of the pieces that are exhibited as part of fronterlebnis, Ploeger subverts our expectations by combining and repurposing technology to make us question our relationship with our technological devices and how we perceive and engage with them in everyday life. In addition to its examination of digital culture, fronterlebnis also seems to suggest that warfare remains a man’s game. We encounter men who are still prone to having their boy’s toys, but it would seem that in this case they are a GoPro in one hand, and a Kalashnikov in the other. Ploeger’s documentation of these conflicts, made with his own personal technological devices, arguably envelopes him in similar mechanisms of fetishization as the soldiers he was with. Neither soldier nor artist seem able to extract themselves from the seductive realm of audiovisual gadgets and self-mediatization in an era of omnipresent digital consumer culture that even reaches as far as the trenches of a dirty ground war.