Those were the words I noticed when interviewing Augmented World Expo organizer Ori Inbar several days before AWE2015, the trade show of Augmented and Virtual Reality. “We’re not in beta anymore…” Inbar said, “We now have companies implementing enterprise-scale Augmented Reality solutions, and with coming products like the Meta One and Microsoft HoloLens, the consumer market is being lined up as well.” With the addition of the UploadVR summit to AWE2015 the event was a blitz of ideas, technologies and new hardware.

AWE/Upload is a trade and industry event that also includes coverage of the arts and related cultural effects, although it is smaller when compared to the industrial aspect of the show. In this way it is similar to SIGGRAPH and this is much of my rationale for covering this, and also SIGGRAPH later this year? Doing so is as simple as McLuhan’s axiom of “The Medium is the Message” or, better yet, examining how developers and industry shape the technologies and cultural frameworks from which the artforms using these techniques emerge. The issue is that in examining emerging technologies we can not only get an idea of near-future design fictions but also the emerging culture embedded within it.

To put things in perspective, Augmented Reality art is not new, as groups like Manifest.AR have already nearly come and gone and my own group in Second Life, Second Front, is in its ninth year. Even though media artists are frequently early technology adopters, what appears to be happening at the larger scale is a critical mass that signals the acceptance of these new technologies by a larger audience. But with all emerging technologies there is drama driven by those industries’ growing pains. For AR & VR the last two years have certainly been tumultuous.

Last year’s acquisition of Oculus Rift by Facebook sent ripples through the technology community. Fortunately, unlike my upcoming example, the buyout did not eliminate the Rift from the landscape; instead it gained venture capital allowing for licensing of the technology for products like the Sony Gear VR. Also the current design fictions being distributed by Microsoft for its Hololens give tantalizing glimpses of a future “Internet of No Things” full of virtual televisions and even ghostly laptops. This was suggested in a workshop by company Meta and the short film “Sight”, in which things like televisions, clocks, and objective art might soon be the function of the visor.

However disruptive events also happen in the evolution of technologies and their cultures. The news was that scant weeks before the conference a leading Augmented Reality Platform, Metaio, was purchased by Apple. Unlike the transparency and expansion experienced by Oculus the Mataio site merely said that no new products were being sold and cloud support would cease by December 15th. In my conversation with conference organizer Ori Inbar we agreed that this was not unexpected as Apple has been acquiring AR technologies, which has been related in rumors of “the crazy thing Apple’s been working on…”; But what was surprising was the almost immediate blackout, part of the subject of my concurrent article “Beware of the Stacks”. For entrepreneurs and cultural producers alike there is a message: Be careful of the tools you use, or your artwork (or company) could suddenly falter in days beyond your control. Imagine a painting suddenly disintegrating because a company bought out the technology of linseed oil. Although this is a poor metaphor, technological artists are dependent on technology and one can see digital media arts’ conservative reliance on Jurassic technologies like Animated GIFs for its long-term viability, but to go further I risk digression.

Another remarkable phenomenon this year was the near-assumption of the handheld as a experience device, and their use seemed almost invisible this year. What was evident was a proliferation of largely untethered headsets, ranging from the Phone-holding Google Cardboard to the Snapdragon-powered (and hot) ODG Android headset, boasting 30-degree field of view and the elimination of visible pixels. In the middle is the tethered, powerful Meta One headset with robust hand gesture recognition. Add in the conspicuously absent Microsoft Hololens and the popular design fictions of object and face recognition are emerging.

That is unless you are a brave early adopter, developer, or enterprise client. The fact that there was an entire Enterprise track and Daqri’s release of an AR-equipped construction/logistics helmet made it clear that the consumer market, much more prevalent last year, has clearly been placed in the long-term. For now, consumer/artistic AR is largely confined to the handheld device, as experienced through Will Pappenheimer’s “Proxy” at the Whitney Museum of American Art or Crayola’s “4D coloring books” in which certain colors serve as AR markers. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as an audience is likely to have a device that can run your app through which they can experience the art. As an aside, this is the reason why I chose to use handhelds for my tapestry work – imagine trying to experience a 21’ tapestry with a desktop using a 6’ cord! At this point, clarity and function, both partially dependent on computer power, have created a continuum from strapping your iPhone to your forehead like a jury-rigged Oculus for under $50, to potentially using a messenger bag with the Meta at $512, to the expensive ($2750), hot, but elegant ODG glasses you might try on if you visit the International Space Station.

While discussing the general shape of technology gives a context for its content and application, a media tool is often only as good as its app. Without meaning to show favoritism, Mark Skwarek’s NYU Lab team has been going outstanding work from a visualization of upcoming architectural developments to a surprising proof of concept for a landmine detection system, which I thought was amazing. Equally innovative was the VA-ST structured light headset for the visually impaired, which has several modes for different modes of contrast. These alternate methods not only was surprising in terms of application and possible creative uses but also changed my perception of AR as possessing photorealistic, stereoscopic overlays.

Other novel applications included National Geographic’s AR jigsaw puzzle sets, of which I saw the one outlining the history of Dynastic Egypt. I felt that if I were a kid, building the puzzle and then exploring it with AR would seem magical. There are other entertainment and experimentation platforms coming online like Skwarek, et al’s “PlayAR” AR environmental gaming system. But one platform I want to hold accountable for still being in late beta is the” LyteShot” AR laser tag system, which got an Auggie Award this year. My pleasure in the system is that the “gun” per se is Arduino-based, meaning that it could be a maker’s heaven. It uses the excellent mid-priced Epson headset, but at this time it is used primarily for status updates although there is a difference between AR and a heads-up display. So, from this perspective, it means that there are some great platforms getting into the market that are highly entertaining and innovative, but there are a few bugs to work out.

For the past thousand words or so I have been talking about the industry and applications of AR, but for me, my “soul”, if you will, set on fire during the “idea” panels and keynotes. For example, on the first day, Steve Mann, Ryan Janzen and the group at Meta had a workshop to teach attendees how to make “Veillometers” (or pixel-stick like devices to map out the infrared fields of view of surveillance cameras. Mann, famous for creating the Wearable Computing Lab at MIT and being Senior Researcher at Meta, still seemed five years ahead of the pack, which was refreshing. Another inspirational talk was given by one of the progenitors of the field, and inaugural Auggie Award for Lifetime Achievement, Tom Furness. His reflection on the history of extended reality, and his time in the US Air Force developing heads-up AR was fascinating. But what was most inspirational is that now that he is working on humane uses for augmentation systems such as warping the viewfield to assist people with Macular Degeneration. This, in my opinion, is the real potential of these technologies. In fact this array of keynotes was incredible, with Mann, Furness, the iconic HITLab’s Mark Billinghurst, and science fiction writer David Brin, (who comes off near-Libertarian) gave vast food for thought.

Every year, the Augmented World Expo gives out the “Auggie” awards for achievements in technology, art, and innovation in AR. I think it should be noted that the Auggie is probably the world’s most unique trophy, consisting of a bust that is half naked skull and half fleshed head with a Borg-like lens with baleful eye wired into that head. The Auggie is another aspect of AWE that signals that the world of Reality media is still a bit Wild West.

There are several categories from Enterprise Application to Game/Toy (LyteShot having won this year), and many of them are largely of interest strictly to developers. For example, the fact that Qualcomm’s Vuforia development environment won three years in a row gives hint to its stability in the market, and Lowe’s HoloRoom is a wonderfully strange mix between Star Trek and Home Improvement. The headset winner was CastAR, a projective/reflective technology where polarized projectors were in the headset instead of cameras, which worked amazingly well. The other winners were gratifyingly humane applications such as Child MRI Evaluation and Next for Nigeria (Best Campaign). The prizes impressed on me that the community, or part of it, “got it” in terms of the potential of AR to help the human condition, which is perhaps a “superpower” that the conference framed itself under.

Being that I am writing this for an art community it would be of interest to know where the art was in all of this. The Auggies have an Art category, as well as a gala between the end of the trade show events and the Auggie Awards. The pleasant part about AWE’s nominations for the best in AR art is that those works have integrity. Manifest.AR regular Sander Veerhof was nominated for his “Autocue”, where people with two mobile devices in a car can become the characters of famous driving dialogues (“Blues Brothers”, “Pulp Fiction”, “Harold and Kumar”). Octagon’s “History of London” is reminiscent of the National Geographic puzzles, except with far greater depth. Anita Yustisia’s beautiful “Circle of Life” paintings that were reactive to markers were on display in the auditorium but, besides a Twitter cloud and a Kinect-driven installation, the art was swamped by the size of the auditorium.

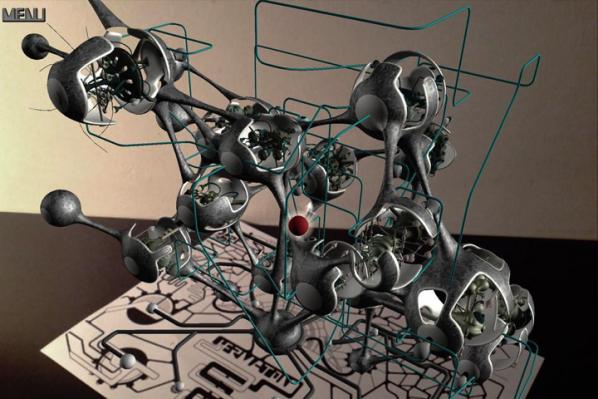

The winner of the art Auggie, Heavy & Re+Public’s’ “Consumption Cycle”, (which this writer saw at South by Southwest Interactive) was a baroquely detailed building sized mural of machinery and virtual television sets. I feel a bit of ambivalence about this work, as Heavy’s work tends to rely on spectacle. Of the lot I felt it did deserve the Auggie, purely for its execution and the effective use of spectacle. But with the emerging abilities of menuing, gesture recognition, and so on, I felt that last year’s winner, Darf Designs’ “Hermaton”, employed the potentials for AR as installation in a way that was more specific to the medium.

Yes, but it was in a much smaller area than the AR displays. There were standout technologies, like the Chinese Kickstarter-funded FOVE eye-tracking VR visor, a sensor to deliver directional sound, and Ricoh’s cute 360 degree immersive video camera. The Best in Show Auggie actually went to a VR installation, Mindride’s “Airflow”, where you are literally in a flying sling with an Oculus Rift headset. Although a little cumbersome, it was as close to the flying game in the AR design fiction short, “Sight”. So, in a way, the ideas of near-future design and beta revision culture are still driving technology as surely as the PADD on Star Trek presaged the iPad.

This year’s AWE/UploadVR event showed that reality technology is emerging strongly at the enterprise level and it’s merely a matter of time before it hits consumer culture, but it’s my contention that we’re 2-4 years out unless there’s a game changer like the Oculus for AR or if the Meta or ODG get a killer app, which is entirely possible. So, as the festival’s tagline suggests, are we ready for Superpowers for the People? It seems like we’re almost there but, like Tony Stark in the beginning, we’re still learning to operate the Iron Man suit, sort of banging around the lab.

Dual

Nottingham Playhouse

5 September – 30 October

After a glorious false start in the 1990s, the previously over-hyped technologies of virtual reality have been quietly reclaimed in a more sustainable and democratic way through Free Software and Open Source hardware. The show “Dual” at Nottingham Playhouse showcases art that mostly uses these new technologies. A theatre is the perfect setting for the reality play of virtual reality. Curatorial collective The Cutting Room (Clare Harris and Jennifer Ross) have organized the funding, production, and presentation of artworks that mix the virtual and the real in creative ways.

Michael Takeo Magruder’s “Deconstructed Metaverse” (with Drew Baker and Erik Fleming), 2012, is installed on the upper landing of the theatre. The windows on the landing have been glazed with images of warmly coloured softly undulating colours. On closer inspection they are pixellated and have endless lines of computer code superimposed over them in small white type. The code is XML representing a virtual world, and that virtual world can be seen and interacted with on monitors in front of the windows. They display a ceiling-less ultra-modern rotunda with windows glazed in images of the views that could originally be seen through the real windows that are now glazed with images of the site-specific virtual world.

The first, smaller, monitor sits on a plinth alongside the circuit board that runs the virtual world using OpenSim under GNU/Linux from a single USB memory stick. You can use a keypad to explore the world, your presence there represented by a generic default human avatar that walks and flies around the island. Or you can visit the virtual world over the Internet. In either case, a large screen further along shows a rotating view of the island, its architecture and inhabitant(s).

Magruder has worked with virtual environments since the VRML era, and “Deconstructed Metaverse” continues some recurring themes while bringing them to a new level. There are multiple layers of reality and presence to this work that the viewer can find themselves looking into and out from, relating to other onlookers as part of the audience or part of a performance in the virtual world themselves.

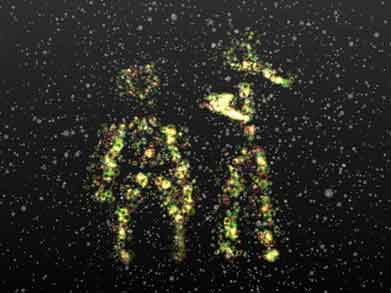

Brendan Oliver’s “Particulation” uses a Microsoft Kinect to capture the poses and motion of pairs of patrons walking through the Playhouse’s ground floor bar. A laser-scanning motion tracker and the software to process its input would have been unobtainable for most artists a decade ago. Oliver makes good use of hardware that was liberated against the wishes of its manufacturers and of software frameworks that are shared more freely.

Oliver uses them to capture and evoke the movements of two people who may not realise that they are the inspiration for the visual art on the wall. They are translated into a particle system of bubbling circles of light projected just far enough away from the sensor that monitors them that the connection between captured movement and animated image is not immediately obvious from all angles. Particulation has the feeling of joyous discovery and exploration that the best interactive multimedia art can bring to a space.

Below ground, “Mirror On The Screen” by Charlotte Gould and Paul Sermon uses similar technology to Deconstructed Metaverse to create a pocket universe of symbolic scenery and objects from children’s stories. In order see the screen presenting the virtual world and use the keypad to move your avatar around it you must stand in front of a printed backdrop where you are watched by a webcam. The resulting video stream is fed into the virtual world and superimposed onto cracks in its reality.

In addition to seeking the highest place in the forest, the edges of the world, and all the objects and characters within it, you find yourself hunting your own reflection. The tables are turned as the avatar you are watching starts watching you, and your purpose becomes seeking out further reflections. The setting of the theatre puts the viewer in a frame of mind open to the drama of the virtual world and its looping back on reality. Far from jolting you out of the experience, suddenly being faced with your own image in the virtual world draws you in further.

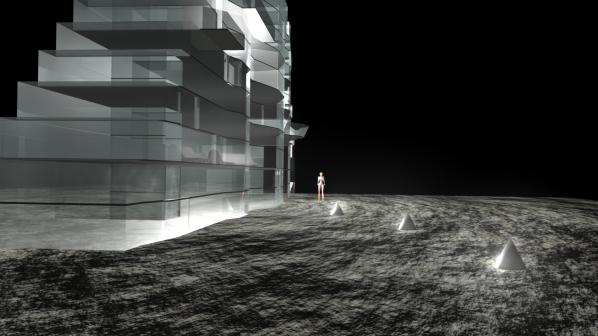

Finally, Kim Stewart’s “Sigma 6” is a 3D computer animated film set in a dystopian high modernist moonbase-like environment of harsh architecture and harsher treatment. The virtual world-like quality of the animation, and the avatar-like quality of its persecuted protagonist have their reality punctured in a way that continues the theme of mixed realities in a way that turns towards body horror.

These common themes of blurring virtual environments with real bodies and places allow the works to complement and distinguish themselves from each other artistically and technically. The Cutting Room are to be applauded for assembling such a thematically tight and technologically competent show that both serves and is served so well by the context of the institution that it is staged in.

http://www.nottinghamplayhouse.co.uk/about-us/the-cutting-room/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.