Alan Sondheim has been ploughing a very singular furrow through art, music, writing, philosophy and much else since the late sixties. On the occasion of his participation in the Children of Prometheus exhibition at Furtherfield Gallery we present here an interview conducted by the artist and writer Michael Szpakowski in which Sondheim gives a broad overview of his artistic formation, practice and philosophy.

Michael Szpakowski: I first came across your work through the Webartery mailing list in 2001. I remember being knocked out by your productivity, a productivity that seemed to be allied to an incredible intellectual curiosity and restlessness, resulting in in words, images, movies, music – I remember once you started making little programs in some variant of Visual Basic… All of these posted day in, day out, come rain or shine, to the list… And, obviously I preferred some to others and for anyone to follow every piece of work you made would mean doing little else with their lives, but the quality, the variety, of what you made was ( and remains) staggering.

I found this compulsion to make work both admirable and invigorating and I’ve followed your work ever since. I think I even once compared you to Picasso on DVblog because I couldn’t think of anyone working in art for the net (and every such description is problematic, I’ll ask something more specific later) who seemed to come anywhere near to that fecundity allied to quality too…

I think of this interview as a general introduction to your work for someone who maybe has only happened across it for the first time in the exhibition at Furtherfield so I’d like to ask, first of all, for you to give us a sketch of your intellectual and artistic formation and the milieu(x) in which you have worked (I mean right from the beginning – tell us what makes you, you!):

Alan Sondheim: Of course this is difficult to answer; I began with writing and around the age of 19, started making music as well, but I was always restless. The compulsion has personal roots, but also a desire to move into an environment, habitus, and explore its limitations and promises; in all of this, I’m concerned with the interplay of the somatic and consciousness on one hand, and abstraction, the inertness of the real, mathesis (the mathematization, structuring of the world) on the other. So there’s this dialog at the limits. My first production was a book of experimental writing, An,ode ; around the same time I made three recordings, two for ESP-Disk; this was around the late 60s. Clark Coolidge, the poet, was very important to me early on; I met him at Brown; he introduced me to Vito Acconci and shortly after, early 70s, I moved to NY, eventually SoHo in its heyday. I’ve never been a traditional artist/writer/musician/etc. but move among these areas; I’m concerned with what for me are fundamental issues of philosophy, body, and the world. I want to explore at the limits of what I’m capable of doing. How is consciousness in relation to the world? How is the world?

I’m driven to create daily; while teaching at UCLA, I made a sound film (16mm for the most part) a week for 37 weeks; they ranged from a minute to an hour in length and were forms of deconstructed narrative. Now online, I try to make a work daily in whatever medium, including virtual worlds of all sorts; I continue to try to push limits – what I call ‘edgespace,’ – the space where gamespaces/worlds begin to break down, and what then? (By ‘gamespace,’ I mean, literally the space of a game, where rules hold – for example chess or football. The rules may be consensual or enforced, etc.) This is deeply involved with the politics and somatics of these spaces of course, and on the political spectrum, I’m leftist and deeply pessimistic; I don’t see internet or social media as salvation of any sort, but as fundamentally neutral, extraordinarily adaptable to any number of usages. I’ve written on the differences at the finest levels between the analog and digital, areas like that usually taken for granted; what emerges is a kind of granularity situated within an obdurate real world whose biosphere is faltering deeply.

M: Although you are included in an exhibition in a physical space here the vast majority of your output has been presented on the net, usually in the context of one or more mailing lists. Could you say a bit about this. Was this a conscious choice or pragmatism or somehow both? Is there anything you particularly prize about the rhythm of work and presentation that comes with this kind of platform and has the eclipse of many of the old mailing lists with the rise of social media caused problems for you – have you tried to adapt to/utilise these newer modes?

A: It’s pragmatism combined with a desire to explore; edgespace teeters uneasily and tends towards what I call blankspace, where the imaginary exists – for example, the ‘heere bee dragonnes’ in unknown areas of early maps (I haven’t actually seen the expression, but it serves here). I present my work on Facebook and G+; I also used YouTube for a long time until I was banned from it.

M: Banned from it?

A: A long story that would take this too far afield…

I work well in presentation/talk/performance mode online and off. I believe in the depth of email lists of course. I do think my avatar work is really well suited to gallery spaces; I’ve had up to seven projections going at the same time. I’ve also performed live in virtual worlds or mixed-reality situations which are projected/presenced directly, and for a long time Azure Carter, my partner, and I worked with the dancer/performer/choreographer Foofwa d’Imobilite; the physicality of the work was amazing. And another aspect of what I do – what grounds me – is playing musical instruments, mostly difficult (for me) non-western ones; the instruments require tending and close attention. I tend to play fast. Most of them are strings, bowed or plucked; the music is improvisation. Recently I’ve been focusing on the sarangi, for example. And I’ve had something like 17 tapes, lps, and cds issued; the most recent is LIMIT, which was done in collaboration with Azure and Luke Damrosch, who did Supercollider programming based on concepts I’ve had about time reversal in real time – an impossibility in gamespace, but the edgespace is fascinating. The music products excite me; they’re out there in a way that my other work isn’t.

M: I remember when I first discovered internet art or whatever we want to call it (and there have been numerous quasi theological arguments about this) that there was an intense debate about whether the internet was a conduit or a medium – so many artist-scripters/programmer tended to rather look down on those who simply took advantage of the network’s distribution and dialogical properties (although I have to say that my view is that it was in this massive extension of connectivity that the real force of the thing resided – I remember being told in 2001 that moving image was not internet idiomatic which is amusing given the rise of YouTube &c.) Your work, certainly of the last 17 years or so, strikes me as being intimately tied up with the network and with the unfolding possibilities of new media but not necessarily in the sense that you work with the network itself to make objects, works and more in the second sense of the conduit…

A: It depends; for example one of the projects I initiated through the trAce online writing community in 1999-2000 – over the hinge of the millennium in other words – was asking a world-wide group of artists, IT folk, etc., to map traceroute paths and times from the night of 12/31 to the afternoon of 1/1; the internet was supposed to run into difficulties – over timing etc. – and I wanted to create a picture of what was happening world-wide. A second project somewhat later was using the linux-based multi-conferencing Access Grid system to send sounds/images/&c. from one computer to another in the Virtual Environments Lab at West Virginia University – but these images would travel through notes, much like the old bang!paths, around the entire world. So, for example, Azure would turn her head in what seemed like a typical feedback situation – the camera aimed at a screen, she’s in front of it, the result’s projected on the screen, &c. – but each layer of the feedback had independently circled the globe (through Queensland to be specific), creating time lags that also showed the ‘health’ of the circuit, much like traceroute itself. It was exciting to watch the results, which were videoed, put up online with texts &c.

Part of the difficulty I have is being deeply unaffiliated; I need others to give me access to technology. For example, I’ve used motion capture in three different places, thanks to Frances van Scoy and Sandy Baldwin at WVU; Patrick Lichty at Columbia College, Chicago; and Mark Skwarek at NYU. I also did some augmented reality with Mark, and with Will Pappenheimer. To paraphrase, I’m dependent on the kindness of others; I have no lab or academic community to work among in Providence; what I do is on my own. John Cayley gave me access to the Cave at Brown; Eyebeam in NY (I had a residency there) gave me space and equipment to work with, and in both places I was able to create mixed reality (virtual world/real bodies) pieces – those also bounced through the network…

M: Could you talk, then, a bit about the motion capture/avatar work that seems to have been central to what you are doing over the last ten years or so. I also don’t think I’m mistaken in detecting a very decided move back to music making of late (I know this has always been there but it feels foregrounded again)

A: The mocap work has been ‘deep’ for me; it involves distorting the entire process, in other words distorting the somatic world we live in. There are numerous ways to do this; the most sophisticated was through Gary Manes at WVU, who literally rewrote the mocap software for the unit they had. I wanted to create ‘behavioral filters’ that would operate similarly to, say, Photoshop filters; in other words, a performer’s movement would be encoded in a mocap file – but the encoding itself during the movement itself, would be mathematically altered. Everything was done at the command line (which I’m comfortable with). The results were/are fantastic. A second way to alter mocap is by physically altering the mapping – placing the head node for example on a foot. But I worked more complexly, distributing, for example, the nodes for a single performer among four performers who had to act together, creating a ‘hive creature.’ All of this is more complicated than it might sound, but the results took me somewhere entirely new, new images of what it means to inhabit or be a body, what it means to be an organism, identified as an organism. This is fundamental. I’m interested in the ‘alien’ which isn’t such of course, which is blankspace. (The alien is always defined within edgespaces and projections; we project into the unknown and return with a name and our fears and desires.)

Most of what I do, for me all of what I do, is grounded in philosophy – ranging from phenomenology to current philosophy of mathematics to my own writing. So these explorations are also artefactual; I think philosophy is far too grounded in writing as gamespace; writing for me, when it’s touched by the abject, the tawdry, the sleazy, the inconceivable, opens itself up.

As far as music goes, I touched on it above in regard to LIMIT. One thing that concerns me is speed, playing as fast as possible, so that the body and mind move on de/rails that are at my limits; I think of this as shape-riding and the results and internal time dilations involved keep me alive…

M: You are genre/practice/technique promiscuous and you have a high level of skill in all –you could equally (and have been) styled Alan Sondheim ‘writer’ , Alan Sondheim ‘musician’, Alan Sondheim ‘maker of moving image work’ (with a marvellous sub-category ‘Alan Sondheim ‘maker of dance related video works’, for a while). Is one of these, in your heart of hearts, central, and, whether this is so or not, how do you place yourself in respect to the various traditions around these areas of work. How do you fit into the art world, into literature or the experimental film tradition? How do you relate to net art/networked art/new media &c.?

A: I don’t seem to fit into the artworld, net art, poetry world, music world &c. – it’s difficult for me to get my work around as a result. Nothing is central but a desire to see how systems form, coagulate, degenerate, collapse, become abject, &c. in relation to consciousness: How are we in the world? On a concrete level, finance enters into the picture; what can I do given a kind of lack of community around me? How can I push myself?

I’m not sure what ‘net art’ is, but certainly the Access Grid pieces &c. are of that, although not of Web-based protocols. There are so many ports out there to use! I do think of myself as a new media artist or someone burrowing into post-media. I’ve always had a few people who believe in what I do, who have helped or worked with me, and I’m really grateful for that. But in terms of institutions, I feel like an outsider artist and am treated like one. It came to a head for me years ago one day when I was living in Soho; I had a call from Vito who said he had realized that whatever I am, I’m not an artist; the same day Laurie Anderson spoke to me and said she realized that whatever I am, I am an artist. So my identity has been far more fluid than I’ve been comfortable with, and it’s affected my career. (There was that tape Kathy Acker and I made 1974, and I read an interview a few years ago, forget the source, with Edit Deak who said the tape wasn’t art at all; in the meantime, it continues to be shown at various venues.)

M: Finally, could you say a little about the work in this particular show?

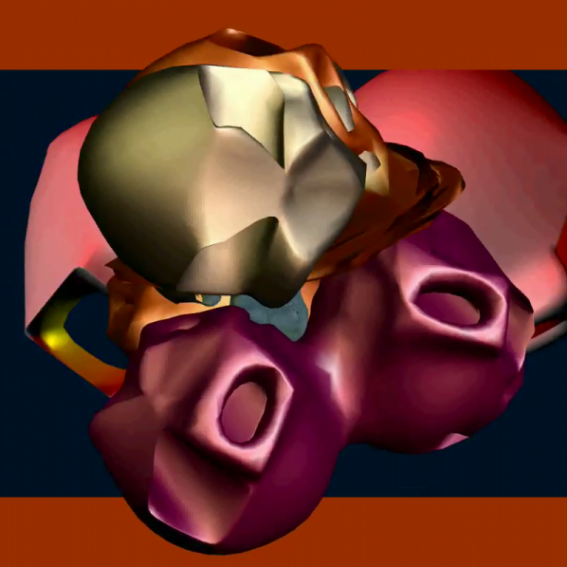

A: The work in the show is a group of 3d-printed avatars distorted through the mocap process described above. For me they connect, deeply, with charred bodies, with anguish, with genocide and scorched earth. They appear also in number recent videos created in various virtual worlds, moving/performing etc. The anguish, so close to death and unutterable pain, is there. I’ve talked about the kinds of brutal killings occurring now worldwide, from Finsbury Park to the United States, the rise, not only of racisms, but violent nationalisms, in the U.S. certainly encouraged by the present regime. I’m sick of it. We all have nightmares. I want to understand this, this grounding in the blooded earth that shakes our very ability to speak, to think, to act.

And yet of course we must resist.

The work in the show is also critical, then, of technophilia, technological answers to the world, utopian dreaming. The top one percent benefit most from the results. I see utopian thinking as dangerous here. Our so-called president has his finger on 4000-5000 nuclear warheads. That’s the reality for me, and why I don’t sleep at night.

Michael Szpakowski: 聽琴圖 (listening to [Alan Sondheim playing] the qin), after Zhao Ji

// gravure, urushi lacquer & pigment on found wood // 30.5X7.5″

In the 1990s the idea of the virtual idol singer escaped from Macross Plus’s Sharon Apple and William Gibson’s Rei Toei into the cultural imagination. Blank slates for market forces and projected desires, virtual idol singers differ from Brit School drones only in that there is no meat between the pixels and the data.

Hatsune Miku is a proprietary speech synthesis program with an accompanying character whose singing the software notionally renders. Miku the software is a “Vocaloid” synthesizer using technology developed by Yamaha and the sampled voice of voice actor Saki Fujita. Released in 2007, with additional Japanese voices in 2010 and an English version in 2013, the software topped the charts in Japan on release and has led to spin off games and 3D modelling software. It’s claimed the software has been used to produce over 100,000 songs.

Hatsune Miku the character is a cosplayer’s dream, a sixteen year old (with a birthday rather than a birthdate) Anime young-girl with impossibly long aqua hair (there are male Vocaloids as well). She’s had a chart-topping album, “Exit Tunes Presents Vocalogenesis feat. Hatsune Miku” (2010), and started performing “live” on stage in 2009 with Peppers Ghost-style technology. She’s available as (or represented as) figurines, plushes, keychains, t-shirts, and all the other promotional materials produced for successful Anime characters, pop stars, or both. Her likeness can be licensed automatically for non-commercial use. This makes her fan-friendly, although not Free Culture, and means that fan depictions and derivations of her are widespread. The majority of “her” songs are by fans rather than commercial producers.

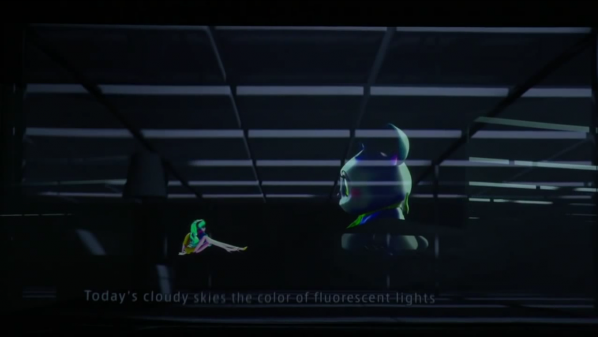

She is now appearing in “The End” (2013), a posthuman Opera (with clothes by a designer from artist-suing fashion company Louis Vuitton) where she takes the stage as a projection among screen-based scenery without a live orchestra or vocalists. Which means that someone programmed the software to produce synthesized vocals and someone else negotiated the rights to use the likeness of the characted commercially dressed in a particular designer’s virtual clothing. “She is now appearing” is easier to say, but like Rei Toei this is an anthropomorphised representation of the underlying data.

It’s getting rave reviews, and the music is competent, enjoyable and affecting: strings, electronica and Supercollider-sounding glitches and line noise under breathily cute synthesized vocals. The visuals are CGI with liberally applied glitch aesthetics, mostly featuring Hatsune Miku and a cute chinchilla-ish animal sitting in or falling through space. The plot is a meditation on what mortality and therefore being human can possibly mean to a virtual character. To quote the soundtrack CD booklet notes:

Miku, who has had a presentiment of her fate, talks with animal characters and degraded copies of herself to ask the age-old questions ‘what are endings?’ and ‘what is death?’.

The phantom in this particular opera is composer Keiichiro Shibuya, who appears onstage largely hidden by two smaller projection screens. As the man behind the curtain it’s tempting to read him as the male agent responsible for the opera’s female subject’s troubles. His presence onstage also threatens to make him the human subject of what is intended to be a repudiation of opera’s European anthropocentrism. But without such an anchor the performance would seem less live and perhaps become cinema rather than opera. It seems that a posthuman opera needs a human to be post.

Music production is uniquely suited to the creation of virtual characters through tools, brands and fandoms. Hatsune Miku functions as a guest vocalist, a role combining artistic talent and social presence with a well understood standing in the economics of pop. In art, Harold Cohen‘s sophistiated art-generating program AARON was licensed as a screensaver anyone could run to create art on their Windows desktop computers, but despite its human name and human-like performance, AARON is never anthopomorphised or given an image or personality by Cohen. Could a virtual artist combining software and character similar to Hatsune Miku function in the artworld or in the folk and low art of the net and the street?

The license for Hatsune Miku the character is frustratingly close to a Free Culture license. Could a free-as-in-freedom Hatsune Miku or similar character succeed? Fandom exists as an ironisation of commercial culture, appropriating mass culture in a bottom-up repurposing and personalisation of top-down forms. Without the mass culture presence of the original work, fandom has no object. Perhaps then without the alienation that fandom addresses, shared artistic forms would not resemble fandom per se.

There are precedents for this. Collaborative personalities abound in art, such as Luther or Karen Blisset. And in politics there is Anonymous. There are also existing Free Culture character like Jenny Everywhere, or even the more informally shared Jerry Cornelius. So it is possible to imagine a Free Software Hatsune Miku, but it’s less easy to imagine what need this would meet.

Unlike the idol signers of literature and television, there’s no pretence that Hatsune Miku is an artificial intelligence. But she is an artifical cultural presence, created by her audience’s use of her technical and aesthetic affordances. Like the robots in Charles Stross’s “Saturn’s Children” (2008), Miku’s notional personhood (such as it is) is defined legally. As a trademark and various rights in the software rather than as a corporation in Saturn’s Children, but legally nonetheless. Heath Bunting’s “Identity Bureau” shows how natural and legal personhood interact and can be manufactured. It’s tempting to try to apply Bunting’s techniques to software characters. If Hatsune Miku had legal personhood, would we still need a human composer onstage?

“The End” was written by that human composer, but software exists that can generate music and lyrics and to evaluate their chances of being a top 40 hit. Combining these systems with software made legal persons would close the loop and create a posthuman cultural ecosystem that would be statistically better than the human one, which I touched on here. It’s not just our jobs that the robots would have taken then. Given the place of music in the human experience they would have taken our souls.

Or the soullessness of Fordist (or Vectorialist) pop. Such a posthuman music system would exclude the human yearning and alienation that fan producer communities answer. It would be an answer without a question. Hatsune Miku is in the last analysis a totem, the products incorporating her are fetishes of the hopeful potential that pop sells back to us.

Despite “The End”, Hatsuke Miku has no expiry date and cannot jump a shuttle offworld. It’s not like she’s going to marry a fellow pop star or come tumbling out of networked 3D printers. But human beings are becoming less and less suitable subjects for the demands of cultural and economic life. In facing our mortality for us Hatsune Miku may have become more human than human.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 Licence.

“a symbol of indeterminate meaning, floating/rotating into the empty white WAG room with no viewers” Bill Miller

Widget Art Gallery. July 17th – August 17th 2013.

Chiara Passa’s Widget Art Gallery (WAG) has been serving art online since 2009. Named for the ability to install the contents of its web pages as a Mac OS X “dashboard widget” or iOS icon, it presents virtual art objects against a standard backdrop or in a standard virtual environment that looks like a white-painted townhouse room repurposed as a small gallery space in an exclusive part of town.

The instructions for using the WAG are Apple hardware-centric, and as I don’t have an Apple device I had to cheat and view it on my GNU/Linux desktop. Digital art’s medium specificity consists in part of its reliance on the facilities of particular hardware and operating systems. This can be exclusive, not everyone owns Apple hardware, but it can also be realistic, Apple’s hardware currently defines computing in the popular imagination.

The image of the gallery in the widget, like the image of a leather desk organizer or a wire mesh microphone in an mobile app, or the very idea of “the desktop” in a desktop GUI, it is a skeuomorph. It is a non-functioning symbolic form that cues the viewer in to the affordances that the experience of the software offers. Like the white cube of a real art gallery, it frames the experience of looking at the artwork and emphasises its seriousness, value, and singularity.

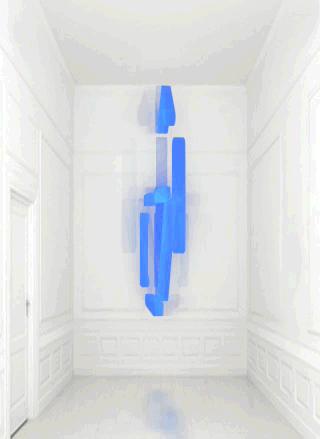

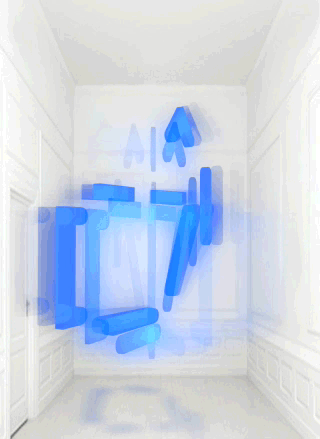

From July to August 2013 the work inhabiting this virtual space is Bill Miller’s “A Symbol“. The titular icon is a composition of soft light blue graphic elements that look like ASCII art that are not aligned to a teletype grid. Or like a misaligned LED matrix. It evokes the art of early military computer games, or the more complex emoticons, or maybe a lamp or a teapot. It rotates, blurs, flickers and stops, glitching and returning.

Widget Art Gallery installations are presented as animated GIFs, but they are different from the usual hilarious recuperations of Compuserve’s low-bandwidth image format in their lack of all-overness and of mass media appropriation. Animated GIFs are often glitched, but with “A Symbol” it is the object depicted in the animated image that is glitching, not the image itself.

The rotating symbol used to be a staple of broadcast television identities. The flickering or glitching symbol signifies signal hacking, technical difficulties, or coming into or out of being by teleportation or rezzing. Popular culture reactions to technology emphasize its flaws and failures to make its smooth surfaces tractable to the imagination. But this symbol remains opaque and self-assured, always returning to its original state.

The symbol’s reflection on the floor pushes it into and anchors it in the imaginary space of the gallery. Like drop shadows in graphic design or the handling of shadows and highlights in paintings it is a visual spatial strategy to make its subject seem more real and in the same space as the viewer. The rhythm and pauses in its rotation, especially the pauses, make it seem intentional and sculptural, they give it a solidity in time as well as space.

The accessibility and framing of the Widget Art Gallery mean that “A Symbol” can travel with and be accessed by its audience over time in a variety of settings, making it even more a reflection of their lives. “A Symbol” is retro digital but with a contemporary electroluminescent aesthetic glow like a Tron Legacy costume or an Android startup screen, militaristic but emotive, hard-edged but glitching, opaque yet evocative. It is a sign of the times.

Dual

Nottingham Playhouse

5 September – 30 October

After a glorious false start in the 1990s, the previously over-hyped technologies of virtual reality have been quietly reclaimed in a more sustainable and democratic way through Free Software and Open Source hardware. The show “Dual” at Nottingham Playhouse showcases art that mostly uses these new technologies. A theatre is the perfect setting for the reality play of virtual reality. Curatorial collective The Cutting Room (Clare Harris and Jennifer Ross) have organized the funding, production, and presentation of artworks that mix the virtual and the real in creative ways.

Michael Takeo Magruder’s “Deconstructed Metaverse” (with Drew Baker and Erik Fleming), 2012, is installed on the upper landing of the theatre. The windows on the landing have been glazed with images of warmly coloured softly undulating colours. On closer inspection they are pixellated and have endless lines of computer code superimposed over them in small white type. The code is XML representing a virtual world, and that virtual world can be seen and interacted with on monitors in front of the windows. They display a ceiling-less ultra-modern rotunda with windows glazed in images of the views that could originally be seen through the real windows that are now glazed with images of the site-specific virtual world.

The first, smaller, monitor sits on a plinth alongside the circuit board that runs the virtual world using OpenSim under GNU/Linux from a single USB memory stick. You can use a keypad to explore the world, your presence there represented by a generic default human avatar that walks and flies around the island. Or you can visit the virtual world over the Internet. In either case, a large screen further along shows a rotating view of the island, its architecture and inhabitant(s).

Magruder has worked with virtual environments since the VRML era, and “Deconstructed Metaverse” continues some recurring themes while bringing them to a new level. There are multiple layers of reality and presence to this work that the viewer can find themselves looking into and out from, relating to other onlookers as part of the audience or part of a performance in the virtual world themselves.

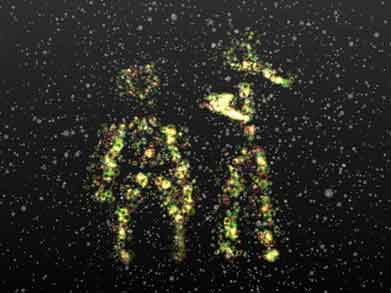

Brendan Oliver’s “Particulation” uses a Microsoft Kinect to capture the poses and motion of pairs of patrons walking through the Playhouse’s ground floor bar. A laser-scanning motion tracker and the software to process its input would have been unobtainable for most artists a decade ago. Oliver makes good use of hardware that was liberated against the wishes of its manufacturers and of software frameworks that are shared more freely.

Oliver uses them to capture and evoke the movements of two people who may not realise that they are the inspiration for the visual art on the wall. They are translated into a particle system of bubbling circles of light projected just far enough away from the sensor that monitors them that the connection between captured movement and animated image is not immediately obvious from all angles. Particulation has the feeling of joyous discovery and exploration that the best interactive multimedia art can bring to a space.

Below ground, “Mirror On The Screen” by Charlotte Gould and Paul Sermon uses similar technology to Deconstructed Metaverse to create a pocket universe of symbolic scenery and objects from children’s stories. In order see the screen presenting the virtual world and use the keypad to move your avatar around it you must stand in front of a printed backdrop where you are watched by a webcam. The resulting video stream is fed into the virtual world and superimposed onto cracks in its reality.

In addition to seeking the highest place in the forest, the edges of the world, and all the objects and characters within it, you find yourself hunting your own reflection. The tables are turned as the avatar you are watching starts watching you, and your purpose becomes seeking out further reflections. The setting of the theatre puts the viewer in a frame of mind open to the drama of the virtual world and its looping back on reality. Far from jolting you out of the experience, suddenly being faced with your own image in the virtual world draws you in further.

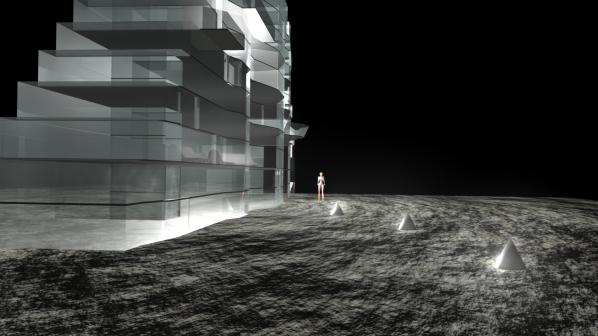

Finally, Kim Stewart’s “Sigma 6” is a 3D computer animated film set in a dystopian high modernist moonbase-like environment of harsh architecture and harsher treatment. The virtual world-like quality of the animation, and the avatar-like quality of its persecuted protagonist have their reality punctured in a way that continues the theme of mixed realities in a way that turns towards body horror.

These common themes of blurring virtual environments with real bodies and places allow the works to complement and distinguish themselves from each other artistically and technically. The Cutting Room are to be applauded for assembling such a thematically tight and technologically competent show that both serves and is served so well by the context of the institution that it is staged in.

http://www.nottinghamplayhouse.co.uk/about-us/the-cutting-room/

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.