“2C E6 85 DC 0B A7 9F 2C 71 CD 47 52 E2 77 CC D2 96 DB 9B 67 51 F4 34 FD 20 A4 0C 86 5A 02 65 B7 D7 68 B6 FB E5 79 31 03 B6 48 76 26 63 1F 19 DC E0 2C C5 CD 74 A4 80 36 A5 56 83 EF 59 2A E8 31” (2017) by Lars Holdhus, hereafter referred to as 2CE6, was exhibited at the Øx exhibition of cryptographic art operating in the tradition of 1960s Conceptualism curated by Sam Hart as part of the 2017 Ethereal Summit in New York (one of my smart contract pieces appeared in the same show).

2CE6 is a framed, partially obscured print of hexadecimal digits representing a cryptographic private key. The key is one of 5000 created by Holdhus to authenticate individual artworks over the course of his future artistic career. Exposing it in this way depicts the anxieties of both the artworld and cryptoculture and allows the viewer to reflect on their interaction. To explain why will require us to situate both the artwork and its materials within the history of art and encryption.

The re-emergence of cryptography as a popular pursuit in the Nineteenth Century starts with a link between code and art. Cryptography and deciphering were popularized by the American author Edgar Allen Poe, who later created the cryptographic literary form of the detective story. In Poe’s early story “The Gold Bug”, an encrypted message leads to hidden pirate treasure. It is the story of an investigation, but before and without the framework of the investigating detective that would find its fullest expression in the figure of Sherlock Holmes (see Franco Moretti’s “Graphs, Maps, Trees”, Verso, 2005, for how this framework fell into place). The detective story came to be a form of deciphering of human secrets and their traces, as Mediaeval cryptography had stood in relation to deciphering the mysteries of God’s creation at a time when the occult, science and cryptography had yet to differentiate themselves. Poe is a similarly liminal figure to mediaeval cryptographers such as Johannes Trithemius in his combining of cryptography, investigation, and spiritualism in literature and in practice. Poe held codebreaking competitions in newspapers and challenged readers to send them unbreakable codes. His writings on cryptography were required reading in the American intelligence community up to the early Twentieth Century. Further reflecting the Mediaeval relationship between cryptography and the occult (encryption and occultation), Poe was a popular subject for spirit mediumship after his death and for some time his most popular work was posthumous.

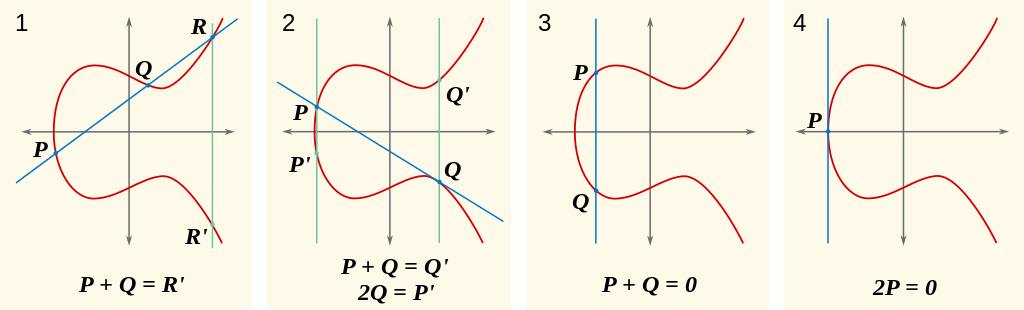

Contemporary cryptography starts not with the codebreaking conflicts of the Second World War (which for the most part just automated earlier systems) but with the discovery of Public Key Cryptography (PKC) at first secretly in the UK and then publicly in the USA in the 1970s. PKC allows messages to be encrypted using a separate key that cannot be used to decrypt it, which can therefore be made public. The secret key that is used to decrypt text that has been encryped by the public key is usually a large number (nowadays consisting of hundreds to thousands of bits) related to it by a “trapdoor function” that uses currently impossible-to-reverse mathematical operations like multiplying enormous prime numbers or multiplying points on complex curves. You are probably using PKC to read this website over the HITS protocol, it’s everywhere in contemporary communication and trade. Like the association of cryptography with the occult, this link between cryptography and trade goes back to the Renaissance.

The relationship between mathematics and cryptography stretches back even further, to earlier Arab herpetologists. This relationship was formalized by Claude Shannon in 1949, and operationalized by PKC. In previous eras, art had a similar relationship with mathematics as part of its self-image, for example in its geometries and colour theories, but Contemporary Art has a mathematics taboo. There is no reason why this should continue to be the case – public key cryptography can provide form, subject and content for art.

The points, lines and planes found in private and public keys and in the operations of encryption and decryption relate to mathematics and geometry in art. The mathematics of ratio and projection were common to Renaissance trade and to perspective. PKC has become contemporary trade math, although it has not yet led to an equivalent of perspective in art. While mathematics is a conceptual resource that strangely elicits disdain or hostility in the digital financialized era of contemporary art, Sol LeWitt showed that it can be used in a critical way. The textual and visual representations of these mathematical objects – long strings of hexadecimal or Base58 digits, QR codes and ASCII art – have both their own innate and contingent aesthetics.

These aesthetics can evoke the worlds of communication, commerce and espionage as they are determined in contemporary life by cryptography and its absences (backdoors, sidechannel attacks, quantum computing, etc.). Or the qualities and experiences of secrets, value, identity and trust (or, again, its absence) that they relate to. These are more concrete subjects than the instrumentalized Platonic realm of cryptographic mathematics, but they flow from them.

Taking a position on these or allowing the artwork’s participant to do so, presenting them for critical reflection or using them as indexes of broader social phenomena makes them content. Those phenomena include the economy, whether conventional finance or cryptocurrency, politics, whether secrecy or hacks of state actors and cypherpunk provocateurs, and the questions of identity, authenticity and permission that PKC and cryptographic hashing are applied to in networked media and culture.

The presence of cryptography or its imagery in a piece of art need not function as any of these – apart from anything else an artwork can always fail. It may end up as a mess or as kitsh. These are modes of usually unintentional and visible inauthenticity, in contrast to the intentional but hidden inauthenticity of fakes. The fake is a problem for the art market and for the artistic and scholarly reputations that provide its capital. Catalogues raisonnes are meant to tackle the problem of the fake but the risks of authenticity and value that they carry make them a site of market and scholarly anxiety. When assembled late in an artist’s career or after their death by a foundation, a work being included or excluded by mistake carries the risk of lawsuits and monetary damages. This can have a chilling effect on both scholarship and on markets.

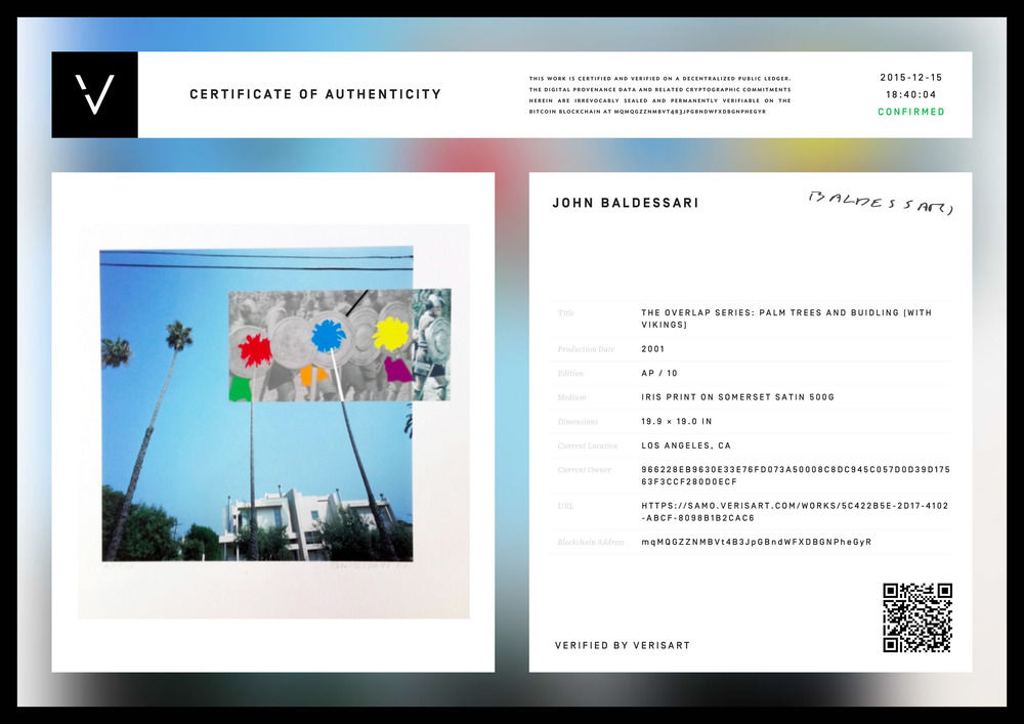

In theory, public key cryptography can help artists with this by being used to create a mathematically unforgeable “signature” code for each new artwork using the private key, which can be checked but not modified with the public key. This can take the form of a digital file, a radio frequency tag, or a QR code or print-out of the signature sealed from sight and attached to a physical work. As long as an assistant, gallerist or spouse doesn’t take a copy of the artist’s current private key and start making fakes, this is a secure way of constructing a catalogue of work that the artist has issued in their name. One of the stronger non-monetary uses of blockchains is to publicly record and timestamp such signatures. In particular this makes it impossible to claim that posthumously released works were released by the artist during their lifetime. This illustrates a way that the fake and its problems of identity authenticity and value relates to the double-spending problem that cryptocurrency solves.

Lars Holdhus is using non-blockchain PKC to authenticate and to limit the number of works they can produce. In 2CE6 the operational security of this strategy is deliberately broken. The first rule of PKC is never to give out your private key. Doing so allows anyone to read your messages (or steal your Bitcoins). The presentation of this act of exposure puts an anxious and fetishized strategy of authenticity and career/legacy construction at risk. It de-occults the information that would guarantee its authenticity (and thereby its value) in order to become or unfold as an artwork, constructing its cultural and economic value by an apparent act of destroying it and critiquing its materials in the process. Looking for a precedent for this leads to net.art and to Conceptualism (see “Conceptual Art, Cryptocurrency and Beyond“) but also to feminist art. The relationship between secrecy, artistic identity, authenticity and transparency has a precedent in the art of the Guerilla Girls. Their proposal to open a Gallery’s finances as the content of their show there likewise involves exposure of an occulted producer/resource of value and identity.

In 2CE6, Holdhus restores the historical link between the contents of art and of cryptography. The contemporary occult of the opacity of the art market, the security of value in trade, and their mathematics exist together cryptographically and artistically in it in a mutually problematizing, and therefore realistic, way. Cryptography functions here as artistic form, subject and content. When a public key is exposed, it is the end of its usefulness, it is dead. 2CE6 functions as a cryptographic memento mori, a post-Crypto Wars version of Holbein’s painting “The Ambassadors“.

Featured image: Zombie Academic haunts the Market of Values

Critical Practice, a group of artists, designers, curators and researchers based at Chelsea College of Art recently organised #TransActing: A Market of Values – a pop-up market made up of over 60 ‘stall holders’ invited to creatively explore and produce alternative economies of value.

During my visit, I first encountered a neo-liberal zombie academic, haunting the market with laments over the demise of an expensive art-education system, which extracts maximum value from students, whilst encouraging them to sell their creativity back to the market. At Becky Early and Bridget Harvey’s ‘Mending for Others’ stall, I was taught to darn, and repaired a hole-ridden Sonia Rykiel hat. Here, mending was framed as ‘giftivism’, a way to build or reinforce a social bond.

At Speakers’ Corner, I heard trade union United Voices of the World represented by Percy Yunganina, one of the #southerbys4. He gave a first-hand account of being banned from site by Sotheby’s auction house for having joined a protest over sick pay and an end to trade union victimisation.

Nick Bell and Fabiane Lee-Perella invited me into Early Lab’s economy of promises, inspired by their work with the Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust: in exchange for a cup of delicately flavoured water, I pledged to make a small intervention to help combat stigmatic preconceptions about mental health.

After these encounters, I #transacted with Critical Practice member Marsha Bradfield, to think about the implications of the Market of Values more deeply:

Charlotte Webb: In critiques of ‘free labour’ on the web, it is claimed that the affective labour of Internet users is exploited by the market. Did you see the Market of Values as a scenario in which the possibility for exploitation was circumvented?

Marsha Bradfield: The short answer is, no. This became acute as building the market ramped up in the days before the event. We became more and more aware how the project embodied our labour, with the vast majority of it being not only unpaid but also affective. We wondered together and apart: To what extent did saying ‘yes’ to the project, sticking with it and honouring our commitment to our peers and community, entail a form of self-exploitation—of us as individuals and as a group? I mean, #TransActing happened and was extraordinary because so many people cared so much—both about the project and each other. And this is, of course, a well-known secret in the worlds of art beyond the art market: their reproduction depends on the widespread exploitation of affective labour. But this isn’t sustainable in the long term. So it’s a valid critique, I think, that #TransActing didn’t exactly buck this trend. Even though we did manage to secure money from the Arts Council and CCW to pay many of those involved, this remuneration was a pittance for what they personally invested. Like others in Critical Practice, I loathe the thought of every transaction being monetised, and in a way this was exactly the conundrum that #TransActing sought to explore by shining a light on types of value that aren’t often valued, precisely because they’re non-financial and cannot easily be accounted for in pounds and pence.

CW: I was intrigued by the uses of the terms ‘value’ and ‘evaluation’ in CP’s description of the event. Are these terms interchangeable for you, or do they carry important nuances? I wondered whether there was something about the measurability of values at stake in the project?

MB: The project was initially called ‘The Market of Evaluation,’ which originated with our research on how value is produced and distributed. We considered, for instance, ‘the value of waste’ by walking around the Isle of Dogs with environmental lawyer Rosie Oliver. She helped us appreciate the social practices of evaluating, well, crap, and how they’re situated, localised and embedded in specific places, buildings, systems, institutions, cultures and histories. The more research we did on evaluation, the more opaque it seemed when generalised. The word has managerial connotations too. So assuming evaluation is, in broad strokes, the assessment of value and that valorisation is the attribution of value, we realised that ‘value’ was the turnkey for our interest. Or rather, it was ‘values’ that so intrigued us, with this plurality opening up space for multiple ones to exist. We also began to appreciate values as transacted through evaluation and valorisation and with this shift, the Market as an event for showcasing these processes gathered steam.

Rather than foregrounding any singular value or type of exploration, our model of distributed curating meant that each Critical Practice member worked with several projects. Each of these explored value in ways that we personally and collectively valued. With 64+ stalls in the market, no one exploration or practitioner dominated. I think we needed this critical mass to make #TransActing a valuable event but not everyone agrees.

Commodification is another way of thinking about the value of #TransActing. The anthropologist David Graeber helped me to crystallise a distinction between value in the singular and values in the plural. David talks about the commoditisation of labour by markets, comparing this with labour like housework and other kinds of care that aren’t commoditised. Of course, it’s money as the so-called universal equivalent that not only allows but entrenches this split. So there’s (singular) value, like that of money that depends on equivalence. And then there are (plural) values, like care, loyalty, generosity, faith, etc. that depend precisely on their refusal to be commensurate with each other.* And so coming back to your question about the measurability of value in #TransActing, Charlotte, I guess that’s the heart of the matter. How do we, on the one hand, take stock of that which must be measured for our work, health, etc. while at the same time more fully appreciate things that can never be measured, but give meaning and significance to our lives?

CW: Critical Practice created bespoke structures for the event, which inevitably created a kind of ‘aesthetic experience’. This brought Claire Bishop’s critique of participatory art to mind – how do you see the role of ‘aesthetics’ playing out in a socially engaged event like this?

MB: You’re right. Tricky questions gather around the aesthetics of social engagement as art practice, especially in the long shadow of the participatory paradigm in contemporary cultural production. Enter politics. As one of many collaborators involved in this project over several years, the ‘aesthetics’ of my engagement has ebbed and flowed over a myriad of micro decisions that together form a kind of slipstream of experience. This makes decision making a prism for organising my insider’s perspective: how I see, hear, and feel this process as it unfolds through sensations of togetherness and shared joy but also tension arising from disagreement.

Much of the decision making that led to #TransActing wasn’t visible on market day. But I’d like to think that ‘aesthetic markers’ maybe signaled it in some way. By these markers I mean indicators that point to the project’s process and all the considerations that it entails. Like the tip of an iceberg, the look and feel of the Market’s stalls, for instance, which were made largely from recycled materials, in collaboration with the stall holders and the art/architectural practice Public Works, pointed to the complex material, conceptual, technical and social processes involved in the Market’s making. I think markers like this help to explain why many who came to #TransActing acknowledged it was ‘a lot of work!’. At the same time the residue of this labour, which filled the atmosphere, gave the impression that doing it was fun.

Decision making was a big part of the participants’ experience too. So many different things were happening simultaneously at the stalls. You had to make moment-by-moment decisions about where to focus. Decision making leading to the market and what occurred on the day seem quite different, though. Much of the will and commitment to make this happen was based on long-term personal relationships. Many of us in Critical Practice are friends and have worked together for years. Exploring the aesthetics of decision making with reference to these tight ties and in contrast to the looser ones organising the experience of #Transacting as a one-day event strikes me as a revealing way to tap the complexity of socially engaged art as cultural production.

*For a concise discussion of theories of value in anthropology, see David Grabber, ‘It is value that brings universes together’ HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3, 2 (2013): 219-43.

——–

Critical Practice is: Metod Blejec, Marsha Bradfield, Cinzia Cremona, Neil Cummings, Neil Farnan, Angela Hodgson-Teal, Karem Ibrahim, Catherine Long, Amy McDonnell, Claire Mokrauer-Madden, Eva Sajovic, Kuba Szreder, Sissu Tarka and many more besides.

www.criticalpracticechelsea.org

criticalpracticeinfo@gmail.com

Charlotte Webb: @otheragent

Marsha Bradfield: @marshabradfield