Join us in using play to design a utopian economy by coming to play Utopoly at Furtherfield Commons.

Utopoly is a tool for inquiry, reflection and idea generation. Its purpose is to generate alternatives to the neoliberal orthodoxy and address the social and ecological crises it creates. It uses a game as utopian practice to critique the state of society and engage in speculation about how to shape the future. Through improvisational play Utopoly provides that rare space for people to re-imagine society, where values, forms of exchange and social relations can be reconsidered and reconfigured. Players then interact with and evaluate the alternative social and political spaces that emerge.

Utopoly starts with a Future Workshop, a method developed by Robert Jungk in 1962 to re-engage people’s innate creative genius which had been suppressed by school, work and consumerism. This involves separate stages of critique, fantasy and implementation. It starts with a discussion and critical exploration around a selected topic or situation. Players critically engage with the now or what-has-become to then open up space for the future or the what-is-yet-to-become. They create fantasies of a utopian nature unconstrained by whether they can be realized or not. Desires, ideas, alternative values, attributes and features of a utopian future are discussed. Moving from the limits of knowing to the possibilities of the yet-to-be-known. This is the political space where the future is open and crucially not a continuation of the present.

The implementation stage involves a ‘hack’ of Monopoly, a popular game which in its original form in 1904 had a progressive and beneficial informative function, but now celebrates and normalises competitive accumulation and socially useless rentier behaviour.

Players discuss and decide which of the features of a utopian future they want represented in the game Utopoly. They determine how the new economy works and – by introducing alternative values, currencies and transactions – can inspire new ways of considering existing social norms. Players then collaborate in a contest against the prevailing crises bound by the neoliberal agenda.

By playing Utopoly participants have the opportunity to reflect on alternative realities and social relations. They can navigate and negotiate the various game features and experience what it is like to inhabit a world incorporating the new economic and social possibilities they have created. In addition, by providing a platform for beneficial expectations Utopoly cultivates the ‘education of desire’ for a better world.

Further information about Utopoly can be found in the following articles:

New School (New York) Public Seminar, Utopoly – A utopian design game

Furtherfield UTOPOLY – playing as a tool to reimagine our future: an interview with Neil Farnan

When Charlotte Webb asked me to write a piece about the future of work for Furtherfield, I immediately thought about Utopoly. Even though this game doesn’t directly discuss how we will be employed or occupied in the future, it creates a rare space where people can re-imagine a different society in which values, forms of exchange and social relations are reconsidered and reconfigured.

To better understand the ethos behind Utopoly, I interviewed Neil Farnan, who is currently undertaking a PhD at University of the Arts London with the research title ‘Art, Utopia and Economics’. He became an Utopoly advocate, introducing many ideas and concepts featured in its current iteration. Neil’s interest in designing a utopian version of Monopoly was initially shaped by his previous studies in User Interface Design, where he developed an interest in Scandinavian design practice and Future Workshops.

Francesca Baglietto: What is Utopoly? More specifically, how does it relate to and differ from Elizabeth Magie’s original version of Monopoly?

Neil Farnan: Utopoly is both a tool for utopian practice and a fun game. It draws on Robert Jungk’s Future Workshop methodology to re-engage people’s imagination and ideas for a better society and incorporates the results into a ‘hack’ of Monopoly.

Elizabeth Magie’s original game (1904) was intended to show how landlords accumulate wealth and impoverish society. Players could choose either a winner takes all scenario or one where wealth was distributed evenly via a land tax. Magie also hoped that children’s sense of fairness meant they would choose the latter and apply these ideas in adulthood. But the Monopoly we have today normalises and celebrates competitive land grabbing and rentier behaviour and Magie was airbrushed out of history and replaced with a more acceptable mythology of the American Dream.

Whilst Magie’s game informed players about the current situation, Utopoly gives people the opportunity to imagine and incorporate values and attributes they would want in a more utopian world. Players are able to determine the properties, the chance and community cards and even rules of the game. The rules being determined by the players means the game is a work-in-progress, however some features that work well can get adopted and carried through to the next iteration.

FB: As you just said, Utopoly doesn’t have a definitive form and rules but changes with each interaction. So, while the future of Utopoly is still in progress, what I would like to know is who started the project and how has this evolved so far?

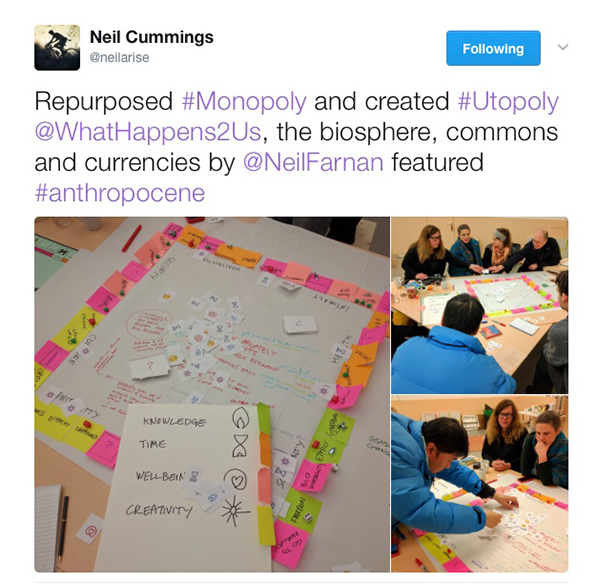

NF: Critical Practice, a research cluster at Chelsea College of Arts, played a central role. We were concurrently developing both Utopoly and an event #TransActing – A Market of Values, and the current version of Utopoly is a synergy of aspects of these two projects. The first ‘hack’ of Monopoly occurred at Utopographies, co-organised by Critical Practice (28th – 29th March 2014), where the elements of the game were redesigned to incorporate utopian values. Inspired, we decided to continue developing the ideas and a second ‘hack’ took place (December 2014). Some of the ideas and values that emerged from this iteration fed into and were represented in the design of the currencies used for #TransActing. A further opportunity presented itself for another ‘hack’ within the research event ‘What Happens to Us’ at Wimbledon College of Art. This iteration was hosted by Neil Cummings and I was invited to include the currencies developed for #TransActing. It was here that Utopoly as a ‘method’ began to emerge, a method for collectively producing possible futures. I have since convened a number of iterations using a large laminated board to facilitate design adaptations and ease of play.

Additionally, researchers from the international ValueModels project (modelling evaluative communities utilising blockchain technology) recently visited Chelsea – we played Utopoly and they loved the method. They have since been inspired to use Utopoly in their research, and I’m excited to receive their feedback on how their version develops.

FB: Utopoly is experimenting with possible new monetary ecosystems in which multiple currencies and values might be exchanged. How might these currencies work and what are they inspired by?

NF: The currencies developed for #TransActing generated the concept of an ecosystem of value exchange and these are used in Utopoly. I have since come across the work of economist Bernard Lietaer, who highlights the problems of mono-currency economies and advocates for a monetary ecosystem using multiple currencies. With their origins in subjugation and taxation, mono-currencies are tools for value extraction. They also contribute to cycles of boom and bust, resulting in the withdrawal of money from the economy and the prevention of economic activity. Historical evidence suggests that economies operating multiple currencies are more resilient – they work in a counter cyclical manner compensating for this withdrawal and allow the economy to keep working.

The irony of Monopoly is that the winner is ultimately left in control of a non-functioning economy. A more preferable state would be to have a healthy flow of values in balance where people are able to exchange their contributions in a mutually beneficial way. A feature of Utopoly is that players no longer seek to own all the property but work together for the common good. The currencies are used to bring privately held properties back into the commons. The economist Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel prize for debunking the myth of the “tragedy of the commons” (Ostrom, 2015) demonstrating the benefits and effective use of common resources. Utopoly also allows economies of gifting and sharing.

I am currently working on ways of modelling innovations such as the blockchain and associated digital currencies.

FB: How would you interpret “work” in this utopian economy? For example, do you think the relation between paid work and unpaid work and/or people’s dependence on employment might be shaped in an ecosystem in which assets/values are brought into the commons to generate value/wealth for all?

Whilst not directly about work, Utopoly reflects the future nature of wealth and values in a Utopian economy. It touches on the current abstract separation of paid work from non-paid work and people’s employment dependency.

In Magie’s original game the players collect wages as they pass ‘Go’. They then buy properties and accumulate wealth extracted from other players. On one corner of Magie’s game is the Georgist statement “Labor Upon Mother Earth Produces Wages”, reminding us that land ownership should not provide unearned income.

As an economy develops people become less self-sufficient and more dependent on employment to meet their needs and a mono-currency makes the separation of paid and unpaid work even starker. The social contract that existed from 1950-70s where employers had a responsibility to their employees is disappearing. Outsourcing, short term and zero-hours contracts make the future of paid work increasingly precarious, and we also face further threats from automation and artificial intelligence.

Economist Mariana Mazzucato (2011) documents the substantial contribution of public investment to the success of today’s businesses. These businesses stand not so much ‘on the shoulders of giants’ but on the shoulders of a multitude of diverse contributions from society at large. A new social contract is needed to take this into account.

Fintech companies make much of the term ‘disintermediation’, but we also need a new form of ‘intermediation’ where contributions are reconnected and recognised. An ecosystem of currencies which register currently unpaid valuable activities together with a basic income could meet this need. This approach is suggested in Utopoly where people collaborate to contribute values and are valued for their contributions. The properties are brought into the commons to generate value and wealth for all.

FB: Playing seems to provide a very rare space in which, by operating in an interstice between reality and fantasy (what the psychoanalyst Winnicott called a transitional space), it is still possible for the players to imagine alternatives to our current economic system. Would you agree that the main political purpose of Utopoly is to provide such a space in order to reopen the capacity to be imaginative about economic and societal organisations?

NF: This is the utopian aspect of Utopoly, using people’s imagination as a means of prefiguring the future. We endure in a society where the mainstream orthodoxy would like us to accept that ‘there is no alternative’. One of the last great taboos is money and the associated economic system. If you consider our mono-currency as a societal tool imposed from the top down, it shapes and informs how we behave and the values we are expected to live by. In a way, it is like DNA; if we can change the DNA of our economy we could create new exchanges, values and social relations. We have become so used to this abstract construct that it is the water we swim in and the box we need to think out of. In order for people to start thinking that another world is possible we need to open up a space for imagination to play out. Art, games and play are some of the few remaining arenas available to engage in speculation about the future. Utopoly fulfils many research functions including acting as a tool for inquiry and reflexion, and a means of modelling future possibilities. It is rare for people to have the opportunity to criticise the existing state of society and work out how to reshape it. By allowing people the space to consider different approaches we can start to encourage better societal norms of exchange and interaction and construct new social contracts.

Darko Aleksovski interviews artist Toni Dimitrov about his work ‘Total surveillance’ featured in the group exhibition SEAFair ’11 ‘Energy, Biopolitics, Resistance strategies and Cultural subversion’. Curated by Melentie Pandilovski, Elena Veljanovska, Zoran Petrovski, ending on the 20th November at the Skopje Museum of Contemporary Art, SEECAN (South East European Contemporary Art Network) and Kontejner, Zagreb. SEAFair 2011 contextualises the artistic and theoretical discourses developing around Bio-politics, aiming at re-evaluating its meaning today, as well as address the possibilities for resisting the dominant international discourses through emancipation and cultural subversion.

Darko Aleksovski: Inspiration is a term which has been differently interpreted throughout the history of art, but generally implies the genealogy of the idea. What was the main inspiration for a project like this? Can you tell us about your references (other similar projects, theory, philosophy, etc)?

Toni Dimitrov: Throughout the twentieth century, art changed its forms of representation. Representation through painting, making objects and visual contemplation, and prior to all – the mimesis – artists changed them with new ways of representation which more and more directly respond and represent the changes in the society, emphasising process, concept, action, interaction, new media, technology, surroundings and of course, the critical discourse… The thing that challenged, and still challenges me to express is the critical discourse and the resignation which is a result of the systematised life and the limitations of the system. It is that primordial anger which one feels at the moment of gaining awareness, when we actually realise where and how we live. Everything that is presented to us as a system that aims to ease our life, is not actually quite so. Take for instance, science and technology, and their goal to “work” for the benefit of humanity. It is not just that they do not seem to make life easier, but on the contrary their usage is harmful for humanity. Exactly from the moment when the greatest hopes were given to technology, science and the great theories, they seem to have failed to fulfill the expectations. Instead of being tools for achieving the ideals of humanity and attaining prosperity, they are becoming the most powerful tools of the system for establishing new forms of power and domination. That same indignation generated from this cognition is my greatest inspiration, from my first critical artwork, through to some other art project, different philosophical essays, and until now.

As inspiration from philosophy, primarily I can mention Baudrillard and Virilio, who precisely vivisect contemporary reality. Then my greatest interest for the utopians and anti-utopians from More and Campanella, who criticise the system at the moment by offering a solution, and all the way to Orwell, Zamyatin and, of course, Huxley, who gives the most precise image of the society we live in – benevolent totalitarianism. I also need to mention the Frankfurt School through From, Horkheimer, Adorno and of course Markuse and other contemporary scholars like Zygmunt Bauman, Ulrich Beck, Frank Furedi, Lars Svendsen…

Darko Aleksovski: To which extent digital media is important for you as an artist? Do you regard the digital artworks to be carriers of more information in a present day digital surplus, or you think that art necessary expresses through digital media because it is the prevalent media in today’s life? How much is the ready-made aspect of this project necessary?

Toni Dimitrov: Digital art affirms all these social changes and at the same time offers a departure from them, leaving different questions from different areas in the center of the discussion. Unambiguously, digital art develops wider contexts and penetrates in other different fields like philosophy, physics, linguistics, semiotics, politics, sociology, even biology. When you visit an exhibition like this, you no more have the feeling that you are at an exhibition where you should experience something beautiful, but you feel like being in a lab where something new is created, something unacceptable even for science itself. Ethic rules and scientific methods have no significance here. Some of those works went too far and by looking at them, you are likely to feel disgust or resignation, feelings that are important for expressing the critical dimension and gaining awareness.

Concerning the ready-made aspect of the digital art, we have to agree with Walter Benjamin, who considers that through making reproductions, the unique experience is replaced by many others and the replication contributes to the loss of the aura of the artwork, with the fact that the artwork through the process of distribution, is not so original, unrepeatable, unique, but can be reproduced and replicated. Simply, the uniqueness of the original is transformed in infiniteness or many others. That is one of the main critical perspectives addressed towards the art that originates after the mechanical reproduction and the development of arts such as film, photography, printmaking, and today we can include a wide variety of digital arts, where practically the original is not present. Here art loses its uniqueness, or aura to be more precise, but receives the “readiness” of the ready-made aspect.

Besides this critique with which I agree, I still think that art/music are created today to be seen/heard today, and not after ten years when they will be a part of the history. This means that art today is created with digital tools and digital media, equally as electronic music is created. In my opinion one should be current and to express through momentary assets, in order to express and present the new social and critical streams more precisely. On the other hand, this does not mean that we should not use classical media in a contemporary way and that I do not draw, or even make a mosaic, but still “officially” I use digital media and conceptual art to express myself and to address a critique.

Darko Aleksovski: Do you consider your project as a critique towards the social apparatus and the instrumentalised life, or towards the inert subject, instructed to accept ready-made social situations?

Toni Dimitrov: Of course the critique is directly addressed to the society and the system. Society is the one who possesses the monopole of power and imposes these aspects of subtle, total control. However, the subject itself is not spared from the critique, precisely because of his inertness, because he does not react against this imposition, but unconditionally accepts it under the vague excuses that all of it is for “his own good”, for his security, protection, etc. Still this imposition is generated by the system, through the upbringing, educating and modeling of the subject itself, so it is more than obvious who is to blame for this condition.

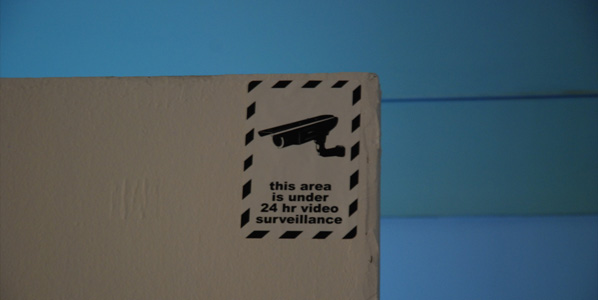

“Total surveillance” addresses the critique towards one of the most explicit “benefits” of contemporary society, which is so much present in our everyday life, that we do not even notice it. The project refers to the anti-utopian dimensions society gets in today’s context. The exposure to constant surveillance is the subject of the anti-utopian works, which precisely anticipate the consequences of irregular use of technology, and the philosophical dimension of which totally corresponds with our present.

It is in these points that we see the postmodern analysis of institutions and discourses of modern art and the ways in which they normalise and discipline the subjects, analyses of the new communication technology, mass-media and their mechanisms of establishing power and domination… We see a critique directly addressed towards today’s modern forms of power which establish new forms of domination. The critique towards information and communication technologies that contribute to the development of human capacities, decomposition of the centralised structure and concentration of power, democratisation of culture… as much as they contribute to the depersonalisation of individuals and manipulation of people.

The realisation of this progress is a vision of the anti-utopia made real, realisation for which time is becoming increasingly shorter. Today we see that, the anti-utopian predictions for the negative consequences of technological and social development are realised with surgeon’s precision, in all of its wide variety, realised through social restrictions, concentration of power, social insecurity, depersonalisation of the individual, destroying of the emotions, control via mass media, mass production, instant entertainment… All these are described and anticipated by the smallest detail, in the works of the anti-utopians years before they became reality.

Darko Aleksovski: Do you see art as the most relevant way for critical actions?

Toni Dimitrov: No. Art is just one, maybe the most banal, but still most receptive way of critical action which will not leave many traces in reality. Art is a paradigm which represents things in a symbolic way. That does not mean that art is insignificant and that there are not examples of art and its critique generating a change or at least raising awareness of some issues, but still it is an accompanying method for addressing direct critique. Theory/ philosophy MUST be inevitable part of the art through which it gets the crucial point for a direct critique and eventually initiating changes. Art without theoretical basis is nearly empty art.

Darko Aleksovski: Your project is a vicious circle copy of the surveillance cameras. To which extent this artistic situation is a replica of the real one, or you consider the real situation to be even worse? How much you think engaged and critical art are perceived nowadays, considering the dispersed art system?

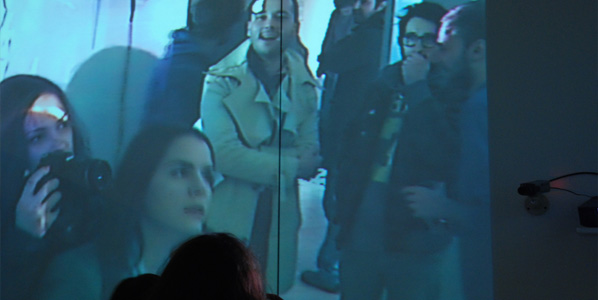

Toni Dimitrov: Unfortunately too true a copy of reality. When you enter the exhibition room, you practically enter a real situation, i.e. you exit in the social reality. This is practically a copy of the social system which we live in. In that case there is no need for gradation of better or worse situation. Go out on the street, pass by the surveillance cameras and feel it. There were mixed reactions when visitors entered the exhibition room, most of them were real, expressed with unpleasant feeling and disgust when they realise they are uncoated and observed from every side. It is the very same thing that happens in every institution and outside on the streets, but we are unaware of who is observing us. That is the feeling I conveyed here; the feeling when you see the results of the observation. It is a precise reflection of the anti-utopian character of our society which develops in this direction mediated by technology.

On the other hand the technological revolution that happened in the last fifty years and the IT revolution created in the digital age, also created fundamental changes in society and the way it functions, even in the physical space. For Virilio, even reality is divided or more accurately it is substituted with another – a virtual one that becomes more powerful mediated by the new technologies. That is why the essay that goes along with the installation begins with a quote by Virilio: One day the virtual world might overwhelm over the real world. This is that same virtual reality in which monitors you look at your existence. It is Virilio that warned us that almost every critique toward the technology disappeared and that we unconsciously accept every innovation without critical view on its consequences, by which we slip in the dogmatism of totalitarian techno-culture. All of this is criticising the way technology changes the contemporary world and human himself, recognising a key factor in technology that determines the modern world.

Finally “Total surveillance” represents a kind of video installation or a network/structure composed of video cameras, video projectors and screens which mutually intersect and constantly record the object/viewer in front of them, from every angle. The viewer, with his/her presence is a participator and part of it at the same time. The cameras record his presence from all four sides, and the viewer is capable of watching the recordings on the screen in front of him i.e. to watch himself. It is about the total surveillance of the viewer, but one in which the viewer is under surveillance by himself from every side and perspectives which are usually invisible for him. In the surveillance, other viewers in the room are also included, by watching themselves, or by watching other viewers. With this, you get a network of crossed cameras and projectors which project images of the viewer from every side, fill the whole room and complement it with the visual noise of the space. This replication and reproduction creates a projection of the viewer in the screens, outside himself, in a sort of virtual world, which continues to infinity, similar to a mirror projected in another mirror, gaining new and new aesthetical forms, a product of the replication and reproduction of themselves.

More information about the project and the artist: tonidimitrov [at] gmail.com

All images by Ilija Madzarovski.