“Flexicity, information city, intelligent city, knowledge-based city, MESH city, telecity, teletopia, ubiquitous city, wired city… [what is] a city that dreams of itself?” (Jones 2016).

This April, 28 brave souls came together for the first time to explore algorithmic ghosts in Brighton — a city known for its blending of new-age spiritualities and digital medias, but perhaps not yet for its ghosts — through the launch of a new psychogeography tour for the Haunted Random Forest festival. Unveiling machine entities hidden within seemingly idyllic urban landscapes, from peregrine falcon webcams to always-listening WiFi hotspots, we witnessed a new glimpse of an old city, one that afforded many strange moments of unexpected (and perhaps even radical!) wisdom regarding the forgotten structures, algorithms and networks that traverse Brighton daily alongside its human inhabitants.

This intervention found its greatest inspiration in the playful, crtitical, anti-authoritarian strategies of the Situationist International group that was prominent in 1950s Europe and birthed the fluid concept of dérive or “drift”, a new method for engaging with cities like Paris through “psychogeographic” walks that charted increasingly inconsistent evolutions of urban environments and their effects on individuals. “Perhaps the most prominent characteristic of psychogeography is the activity of walking,” explains Sherif El-Azma from the Cairo Psychogeographical Society. “The act of walking is an urban affair, and in cities that are increasingly hostile to pedestrians, walking [itself]… become[s] a subversive act.”

Psychogeographical drifts have been interpreted in many ways in many places, from radical city tours with no set destination, to public pamphlets meant to shock people out of their daily urban routines, to unsanctioned street artworks that explore changing architectures and hegemonies of the built environment through direct dialogues. As the Loiterer’s Resistance Movement explains, “We can’t agree on what psychogeography means, but we all like plants growing out of the sides of buildings, looking at things from new angles, radical history, drinking tea and getting lost, having fun and feeling like a tourist in your home town. Gentrification, advertising, surveillance and blandness make us sad… our city is made for more than shopping. We want to reclaim it for play and revolutionary fun.”

In our own interpretation of the psychogeography “play box“, people from across the UK came together from local community discussion lists, universities and creative networks to join the group. We called them ‘node guardians’ to connote a shared sense of ownership regarding both the tour nodes (which were lead not only by ourselves but also by several other brave participants, who also facilitated hands-on activities to engage listeners more deeply in the lived experiences of each machine node). We were intrigued about the moments of access, control and liberation that might be exposed when the machines, networks and algorithms that we engage with on a daily basis were revealed. In the unearthing of lesser-known instances of code-based activity (and the patterns within), we hoped to meet machine spirits, languages and loves along the way. And meet them we did.

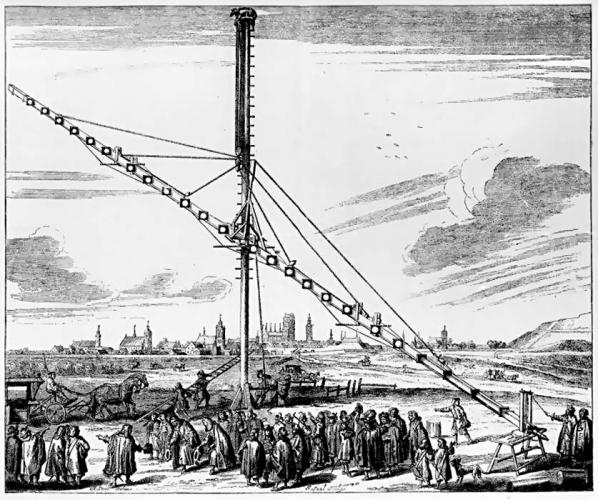

Although the tour aimed to seek out algorithms and machines, we didn’t feel limited to influences from our current digital age. Brighton has a rich history of invention and engineering which has influenced the local geography as well as wider culture. The ghosts of Magnus and George Herbert Volk, father-and-son engineers, can be found all over the city, from Magnus Volk’s seafront Electric Railway which opened in 1883 — making it the oldest working electric railway in the world — to George’s seaplane workshop in the trendy North Laine shopping area, which went on to house a thoroughly modern digital training provider, Silicon Beach Training. Magnus Volk’s most unusual invention, though, only exists as a part of Brighton’s colourful history: the Brighton and Rottingdean Electric Railway, as it was officially called, earned the nickname the ‘daddy-long-legs railway’ as it ran right through the sea with the train car raised up above the waves on 7-meter-long legs. The railway was only in operation for 5 years from 1896 to 1901, but you can still see some of the railway sleepers for the tracks along the beach at low tide.

For a relatively small town, Brighton also played a surprisingly big role in the development of the international cinema industry. In the 1890s and 1900s, a group of early filmmakers, chemists and engineers called the Brighton School pioneered film-making techniques such as dissolves, close-ups and double exposure, and created new processes for capturing and projecting moving images. Key members of the group used the old pump house in local pleasure garden St Ann’s Wells as a film laboratory and shot the world’s first colour motion picture called ‘A Visit to the Seaside’ in Brighton in 1908, using a colour film process called Kinemacolour invented by the group. Although the city’s early passion for cinema is remembered by several blue plaques marking key locations — and the presence of the Duke of York’s cinema, the oldest continually operating cinema in the UK — we wondered how much of Brighton life had been captured in the dozens of short films made at the turn of the century, only to be lost forever?

The rest of the stops on our walking tour took in more contemporary machine ghosts, including the last remaining trace of the city’s USB dead drop network — conveniently embedded in a brick wall on the seafront above the Fishing Museum — which prompted us to ask what information people may have passed to each other before these devices were destroyed by weather and vandals. Dead drops were originally set up to be an anonymized form of peer-to-peer file-sharing that anyone could use in public spaces. They have since been embedded into buildings, walls, fences and curbs across the world. Perhaps some of our tour participants will even be inspired to set up new dead drops around the city to keep the potential for off-grid knowledge-sharing alive.

In a reversal of this spirit of anonymous digital communication, a new network of WiFi-enabled lampposts, CCTV cameras and other pieces of ‘street furniture’ has been unobtrusively installed across the city by BT, in partnership with Brighton & Hove City Council. They now eavesdrop on the personal musings of passers-by who connect to them. These hidden devices provide users with a free WiFi service, but the group wondered at what cost. Participants found themselves questioning whether BT can be trusted to keep our information secure in an age where data has become a valuable marketing commodity.

As part of our psychogeographical aim to unveil the hidden lives of once-familiar urban artefacts, we also summoned the machine ghosts of some of Brighton’s most famous (and infamous) landmarks. Looming over the city centre is a towering modernist high-rise called Sussex Heights, a building that sticks out like a sore thumb amidst the classic Regency architecture of the city’s Old Town. Yet atop the concrete tower also live families of peregrine falcons, whose nesting activities are broadcast to the world by an ever-watching webcam. Conservation groups, architects and technologies intersected in 1990 to provide a nesting box that would enable the falcons, extinct in the area at the time, to successfully breed. They now return to the tower block every spring to rear their young (except in 2002, when they chose the West Pier instead). Writing down our best wishes to this season’s hatchlings, we pasted them onto the building for future city ghosts to browse.

The other most visible instance of architectural and structural technologies descending upon the city can be seen in the new British Airways i360 viewing tower, variously described as a ‘suppressed lollipop’, a ‘hanging chad’, ‘an oversized flagpole’, an ‘eyesore’ and a ‘corporate branding post’. Even if you leave the city, you can’t get away from the sight of the 162-metre tall tower, as it is equally visible from the countrysides surrounding Brighton. It overshadows its neighbour, the beloved remains of the burnt-out West Pier, and opened exactly 150 years after the West Pier first opened in 1866. However, the ‘innovation’ in the i360’s name may be a boon to the city, as it’s expected to pour £1 million a year in the local community and potentially inspire the renovation of the West Pier. Our node-guardians bravely attempted a participatory activity outside the i360 which involved sketching out mock flight warnings to those who entered its gates; the mock flight attendants situated at the base of the i360 were less than amused by these efforts.

In most towns, the shopping centre becomes a well-known haunt for both locals and visitors to congregate, yet most people who visit Brighton’s Churchill Square shopping mall pass by the square’s large pair of digital sound sculptures without even a glance. The sculptures look like a pair of matching stone and bronze spheres, and are the type of public art that you can walk past everyday without actually looking at, but after looking into their always-observing faces once, you’ll never miss them again. They quietly interact with the sky every day through a set of complicated light sensors that trigger a series of musical notes tuned in to each orchestration and angle of the sun. As the sun rises, they call out to one another, their combined song fading away as the sky turns dark. Or at least, we are told they communicate; after a group activity to emulate the interactivities of the spheres, we found ourselves quite unsure if we had actually heard ghostly spherical music emanating from spherical mouths, or just the sound of shoppers and buses passing by.

And finally, if you’ve lived in Brighton for a while you’ve probably come across the French radio station FIP, which until a few years ago you could tune into on radios across the city. While standing in the bustling North Laine cultural quarter, we were briefly transported to Paris by one of our node guardians’ melodica renditions of Parisian cafe music, and heard the story of how a local resident introduced Brighton to FIP in the late 1990s when they started re-broadcasting the radio station out over the city. It became one of the most popular radio stations in town and transmissions continued until 2013, even surviving an Ofcom raid on the mystery broadcaster’s house in 2007 when their equipment was confiscated. The story of Brighton’s love for FIP radio, including a monthly fan-organised club night called Vive La FIP that joyously ran from clubs around the city for years, shows that as well as its own ghosts, our city is also haunted by the machines of distant places.

Indeed, from the distant ghosts of rebellions past to those who quietly slip by underfoot as we walk to the pier, the derives of this tour taught us that unearthing hidden histories of a city can bring both good and bad spirits back to life — moments of local liberation and defiance existing alongside a national state of increased surveillance, conglomeration and control. We call for future tours, psychogeographic and otherwise, that challenge participants to think about Brighton through new forms of engagement that focus on grassroots and community efforts, and their implications in the spaces and places we use every day. Only then can we determine whether the ghosts that surround us are in charge of our fates, or whether the myriad past and present struggles of this city can co-exist in collaboration.

Roger Malina is a physicist and astronomer, Executive Editor of Leonardo Publications (The M.I.T. Press), and Distinguished Chair of Arts and Technology at the University of Texas at Dallas. Dr. Malina helped found IMéRA (Institut méditerranéen de recherches avancées), a Marseille-based institution nurturing collaboration between the arts and sciences.

Mariateresa Sartori and Bryan Connell are two artists recently based at IMéRA. Their work connects with human movement through the city, and addresses the intersection between technology and perception. Recent work by Venice-based Mariateresa Sartori has encompassed drawing and video. Bryan Connell, Exhibit/Project Developer at San Francisco’s Exploratorium, works especially with landscape observation devices and mapping.

Lawrence Bird interviewed Roger Malina, Mariateresa Sartori, and Bryan Connell about the intersection of their work with the city. Images above courtesy: Roger Malina, Rita Gambardella, Bryan Connell.

Lawrence Bird: Roger Malina, in your recent writing you make the case that science is no longer just a field of positive knowledge. Scientists are increasingly open to engagement with the arts — for example artists’ residencies at CERN. You’ve even argued that we’re in a crisis of representation as profound as that of the Renaissance or the 19th century, and this is “driving a new theatricalisation of science.”

Urban life has often been understood as performative – display, performance of social roles, presentation of oneself before others are all part of the public life in cities. How would you say that crisis of representation plays out with regards to this performative dimension of urban life? How is science implicated alongside art in the city, in these conditions?

Roger Malina: One of my arguments for the ‘crisis of representation’ really looks at Renaissance systems of representation — first driven by what the eye could see, and then the eye extended by microscopes and telescopes. These systems of representation were developed that led to a deep contextualising of the viewer in the world.

Today we are in a new situation because so much of our perception of the world comes not through extended senses but, in a real way, through new senses. This has been happening over a number of decades; the first wave of this was at the end of the 19th century when there was a cultural shock with the introduction of x-ray images, infra-red and later radio — which didn’t extend existing senses but augmented them.The most recent series of triggers maybe comes from the nano-sciences and synthetic biology — we now perceive phenomena of which we have no daily experience of (eg quantum phenomena). Field emission microsopy or MRI or some of the other new forms of imaging really don’t build on our existing experience — there are discontinuities and dislocations. Another element is of course the hand held device that leads to techniques for ‘augmented reality’ — I have a phone app that I can point at an aeroplane overhead and it tells me what the plane is, where it came from, and where it is going.

Coming to your question about the city — there is clearly a shift in map construction and reading — from the Cartesian map that we have been acculturated to. The ability to toggle between the bird’s eye view and the “street view”, and the ability to view maps that have multiple layers simultaneously are driving artists and others to develop new forms of representation.

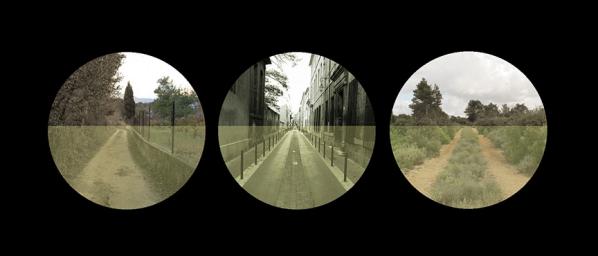

Someone whose work is interesting in this regard is Bryan Connell in San Francisco, he just finished an art science residency at IMéRA in Marseille. He was working on a large urban trail project called GR13 — 300 miles through industrial, urban, sub urban, and wild landscapes (the city had a hell of a time getting right of way through these areas). Bryan is currently working on a web site for the Marseille European City of Culture events, where he’s working on some of these questions of representation. The project involves a collective of ‘artist-walkers’ that I think fits right into this question of performativity.

LB: There’s currently a great deal of interest in the connections between representation, digital technology, and politics, for example the current Hybrid City II conference in Athens. As you’ve pointed out, these often underline the connections between what digital media mean for artists and what they can contribute to citizens — what’s emancipatory about them. What can art offer civil life in this context? Are there any conflicts or contradictions in that relationship?

RM: One pertinent example is the work of Bruno Giorgini, a physicist, and Mariateresa Sartori (visual artist) who work on the “physics of the city.” They were recently in residence in the IMéRA Mediterranean Institute of Advanced Study which hosts artists and scientists in residence who want to work with each other. We now have access to incredible amounts of data on human mobility (pedestrian and various forms of transportation) so it is now possible to study human behaviour quantitatively. Sartori discovered that she could tell many things about a person just through the morphology or topology of their movements through the city. Girogini discovered that people’s movements could be predicted at the 80% level, but 20% of the time he had to introduce what he called ‘social temperature’; in discussions he also referred to this as a ‘free will’ parameter. Barabasi has found similar results analysing cell phone GPS data of individuals. So its interesting to think of the development of cities as 80% predictable and 20% serendipitous. This of course then highlights the role of the arts and culture in making cities part of the cultural imaginary that drives people to make choices. Recently Max Schich here at the University of Texas has analysed very large data bases looking at where prominent people are born and where they die over the last 500 years. Immediately you can see how suddenly certain cities become cultural ‘attractors,’ say the way Berlin or Hong Kong are now. And of course cities are now trying to ‘design’ this into the development of cities. Here in Dallas there has been a huge investment in the ‘arts district’ and in institutions of higher learning in the belief that healthy cities require such investments. See for instance the US National Endowment for the Arts Program; there are many similar programs in Europe.

This doesn’t yet address your ’emancipation’ question. One of the things that is happening is that we are becoming a data taking culture (see the recent literature on ‘big data”). The cell phone has transformed every citizen (that has one) into a data taker. Of course much of this data is used by companies for marketing objectives. But many citizen groups are now able to take data for their social objectives. Some of this is captured by the ‘citizen science’ movement ( one example is here). There have been good examples of citizen’s taking data (on pollution, on illegal activities etc.) and then being in a position to challenge ‘authorities’ of various kinds whether scientific, political or economic (see for instance the way citizen groups have mobilised to collect data after man-made disasters such as oil spills, or illegal logging in forests).

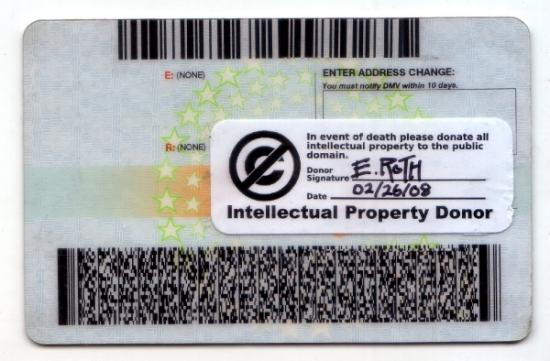

A few years ago I wrote an open data manifesto which argued that I would like to advance a new human right and a human obligation:

1. Each of us has the right to the data that has been collected about ourselves and our own environment.

2. Each of must contribute to the knowledge construction by collecting and interpreting data about our own world.

Most scientific data collection is funded by public tax payer funding. The public has a fundamental right to all data collected and funded by public tax money.

LB: How do you imagine an artist’s training will change as these conditions evolve? And a scientist’s — could we foresee any kind of convergence?

RM: One interesting development is a cohort of hybrids, who have one degree in science or engineering and one in art and design ( for example J.F. Lapointe, a researcher at the National Research Council of Canada with degrees in molecular biology and dance) or degrees in Science or engineering and employment in art or design (like myself or Paul Fishwick, a key figure in the field of aesthetic computing). There’s been an emergence of art/science Ph. D. programs that take students from art or design or science or engineering. I suspect this cohort will grow over the coming years.

LB: Mariateresa Sartori, your IMéRA research project with Bruno Giorgini focused on mobility in the city. Can you tell us a little bit about how your work and Dr. Giorgini’s work complemented each other? What kind of evidence did you bring to the table as an artist?

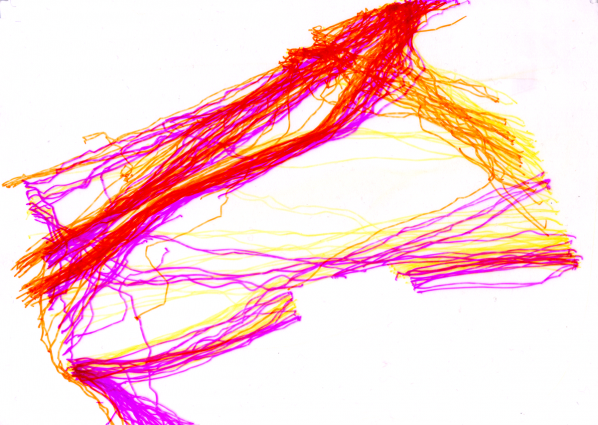

MS: The project I worked on with Bruno Giorgini developed an exploration that began with earlier work in Venice. There I created a series of drawings using a rudimentary, even crude procedure: I traced out the movements of each pedestrian in the Piazza San Marco, drawing their paths with a felt-tipped pen on a transparent sheet placed over the computer monitor. I then faithfully transferred the results onto ordinary large sheets of white paper. The lines thus drawn in different directions created a space, drawing a St. Mark’s Square that is actually not there. As well as the actual physical space, it is also a drawing of our individual and collective manner of relating to space. Each single path determines the route of others, in a continuous and reciprocal game of influences that makes our collective progress.

At IMERA we developed this method for a new environment, a city more ethnically and culturally plural than Venice. Together we set up procedures and tools for collecting data about mobility networks there: nodes, links, chronotopi. These drew on the work of Bruno Giogini’s Laboratorio di Fisica della Città of the University of Bologna. We shot videos focusing on specific behavioural patterns where strategies of shifting, approaching and distancing play a decisive role; and we were also attracted by the places and situations of pedestrian congestion. Using the same technique as in Venice, I translated these into drawings of movement. These again created a space that marks out squares and places which are actually not there, each synthesizing space, time and humanity in a single image.

LB: Is there an emancipatory or governance-related dimension to this work? Degrees of mobility have human rights implications. How does your work as an artist connect with these rights, especially the notion of the right to the city?

MS: The first goal when I work as an artist observing reality is observation, i.e. a way of observing that implies a new attention. The result is always instructive because I do not have particular expectations. After lines have been traced following my process, something always emerges and what emerges can be a useful and indicative element for the emancipatory dimension of the urban condition. I would say that Bruno Giorgini is more involved in that dimension than me, especially in the notion of the right to the city.

LB: There’s a current preoccupation among researchers in a number of fields with the relationship between representation, often engaged with/through technology, and urban life. How has your latest work connected with this relationship?

MS: My way of working with technological instruments such as computers is very particular and limited. I use the computer as a technical tool strongly mediated by the senses, i.e. by human perception. I am very interested in modalities of perception: they are so imperfect, yet sufficiently perfect to make our existence possible.

LB: You described the way you work with technological instruments as “particular and limited.” Another way to look at this is that you make the technological system slow down by inserting yourself into the process… and the result is your drawings, which still movement. Might this be one role for art — to insert the human into the machine? Much net art focuses on flows of information, virtual movement, and representing that. While not quite glitch art, do your representations of movement in some sense intentionally put a brake on the machinery?

MS: I find your words enlightening, you describe my way of working better than me….. Actually I insert myself into the technological process…..but this is not a statement of a position against technology.

I can say that what interests me the most (and art’s relation to science is just one instance of this) is the thread of connection between specific cases and general theory, between subjective and objective. Between, on the one hand, the singularity of events and, on the other, general theory. The individual’s experience is singular, unique; but there is always a thread, even if fine, that leads each individual case to a wider generalisation. What interests me is this incessant – indispensable as much as concealed – mental activity that every day leads us to search for generalisations and regulating principles. What interests me is the human tendency to comprehend phenomena, even the most complex, via schematic representation, via a generalisation that leads to the identification of organising principles. I mean “Comprehension” in very wide sense, where emotions and feelings participate too in embracing reality, including reality. Maybe in this sense I put the human in the machine…

There is a discrepancy between how we perceive reality, mediated by our senses, and the truth decreed by science. On a rational level we recognize the truth, but we cannot internalize in a deep way this knowledge; this is beyond our human capabilities. I think that in my artistic research I find myself in this deep discrepancy.

LB: Bryan Connell, your work in Marseille addresses, among other concerns, technology and its relationship to nature. Do you see the urban environment as playing any particular role in that relationship — of having a particular status in our negotiation of it?

Bryan Connell: One of the things that intrigued me about the metropolitan hiking trail in Marseille is the way it plays with our sense of meaning and value in the exploration of contemporary landscapes. Most long distance hiking trails are designed to lead out of urban environments, not into them. We don’t usually think of carrying a field guide that illustrates the taxonomy of fire hydrants, electrical pylons, or urban weeds on an extended city or suburban walk. That kind of engaged, systematic attention is usually reserved for wild natural terrains. From a traditional environmental perspective, the less altered a place is by human technology, the more scientifically interesting, ecologically exemplary, and aesthetically rich it’s going to be. Without undermining the validity of ever-present environmental concerns, the trail functions as an invitation into a more challenging and complex relationship to the emerging para-wilds and novel ecosystems that are arising at the intersection of the natural world and the technological infrastructure of the built environment.

Similarly, the Marseille trail doesn’t really focus on the kinds of urban sites that are traditionally thought of as having significant historic, architectural, or cultural interest. Instead, the trail route incites visitors into an exploration of the everyday environments and working landscapes of the contemporary urban transect – a world of parking lots, freeway overpasses, suburban developments, abandoned railways, and semi-rural wildlands.

Landscape ecologist Earl Ellis argues that to better navigate our way through the current geohistorical epoch, the Anthropocence, we must expand the traditional ecological concept of regional biomes into the parallel notion of “anthromes” – biomes that are complex interconnected melds of human technology and natural systems. In a sense, the GR 2013 Marseille trail is a sketch or system of exploratory paths into what a publically accessible, anthrome based urban ecology observatory might look like.

LB: A similar question is in relation to the image, especially sequential images. What does it mean for our negotiation of the relationship between nature and technology? Between science and art?

BC: We increasingly live in a networked digital metropolis with an image and information density that both mirrors and exceeds the high population densities of the physical metropolis. One topic of particular interest to me is the role these images play in transfiguring the quality of our desire. To what extent do scientific or aesthetic images that increase our ability to find meaning and satisfaction in observing and understanding urban landscape phenomena mitigate our need to physically alter the landscape to conform to an idealized image of what it should or shouldn’t be?

For example, the Marseille metropolitan trail didn’t require much physical alteration of the terrain – it’s a conceptually designated network of pre-existing roads, paths, streets and highways. The trail’s function is not to alter place, but alter the cognitive landscape of trail users so they have a richer sense of place. If you are fascinated by the diversity of ways a para-wild plant population has adapted to a technologically modified environment, do you need to engage in an energy and material intensive re-landscaping of that environment with a palette of conventional horticultural plantings to make it more “beautiful”? In this sense, constructing interpretive images of landscape is more than a way of augmenting a recreational hiking experience, it’s a way of shifting and re-configuring what we think we have to consume and alter to find meaning and vitality in contemporary landscapes.

http://uranus.media.uoa.gr/hc2/

Hybrid City is an international biennial event dedicated to exploring the emergent character of the city and the potential transformative shift of the urban condition, as a result of ongoing developments in information and communication technologies (ICTs) and of their integration in the urban physical context. After the successful homonymous symposium in 2011, the second edition of Hybrid City has grown into a peer reviewed conference, aiming to promote dialogue and knowledge exchange among experts drawn from academia, as well as artists, designers, researchers, advocates, stakeholders and decision makers, actively involved in addressing questions on the nature of the technologically mediated urban activity and experience.

The Hybrid City 2013 events also include an online exhibition and workshops, relevant to the theme

Hybrid City Conference 2013: Subtle rEvolutions will take place on 23-25 of May 2013.

The Hybrid City II events will take place at the central building of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

This document was edited with the instant web content composer. Use the online HTML editor tools to convert the documents for your website.

Featured image: Environmental Risk Assessment Rover – ERAR – AT (2008) Mobile, Solar Powered, Networked Installation Off the Grid, Neuberger Mus

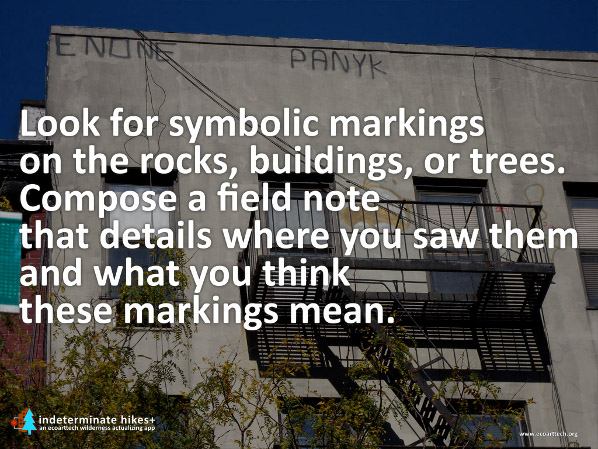

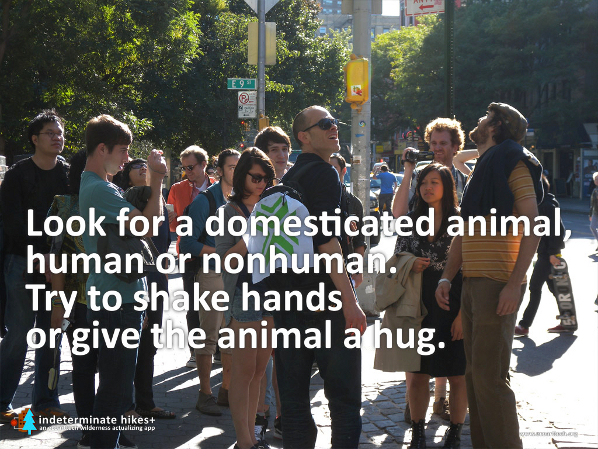

Refusing to regard technology merely as a tool, Ecoarttech expand the uses of mobile technology and digital networks revealing them to be fundamental components of the way we experience our environment. Their most recent work Indeterminate Hikes + (IH +) is a phone app that maps a series of trails through the city. IH + can be accessed globally, or wherever users have access to Google Maps on their mobile phones. After identifying the users’ location, IH + generates a route along random “Scenic Vistas” within urban spaces. Users are directed to perform a series of tasks along the trail and provide feedback in the form of snapshots generating an ongoing, open-ended dialogue.

But the experience of their work is primarily an encounter with technology. Since 2005, Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint of Ecoarttech have been engaged in an artistic exploration of environmental sustainability and convergent media. By drawing our attention to the increasing replacement or mediation of physical experiences by technology, Ecoarttech challenge the widely reproduced distinction between nature and culture. They present their work in the form of videos, digital networks, blogs, performance and installations. Their early video-based work (Wilderness Trouble and Frontier Mythology) plays out a performative and ironic encounter with the natural environment as a historically constructed concept. In the summer of 2005 Ecoarttech made A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness (2005) a database networked performance in QuickTime (DVD and Podcast). The short clips document what Ecoarttech ironically describe as “the experiences of two New Yorkers embarking on their first four months in the woods“. Their objectives were nothing short of

…establishing a functional home without running water, electricity, or maintained roads; developing relationships with locals; un-learning the romanticization of nature while re-learning humanity’s dependence on the environment for survival; and researching the details of the history of the land and the surrounding area.

Sophia Kosmaoglou: The confrontation with the concept of “wilderness” appears to motivate much of your work to date. How did A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness begin and how did you fare?

Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint: About eight years ago, we were very fortunate to acquire a primitive cabin on 50 acres of wild, wooded land, and the experiences we had there changed us completely. Each time we drove from NYC to our “camp” as the locals called it, we were immobilized for about 3-4 days, hardly able to move our bodies as our nervous systems screeched to a halt, adjusting to the quiet. We found a freedom in the woods that we couldn’t find the city – the freedom to take up space, to play, to be quiet, slow, and still. We were also amazed by how some people in the country could seemingly live more independently from bloated global economic systems, growing their own food, chopping their own fuel, harvesting solar energy. They interacted directly with the natural environment whereas we had spent our entire lives ecologically infantilized by overdependence on the industrial grid. We began spending several months at a time at our cabin in the woods: A Series of Practical Performances in the Wilderness is a document of our environmental adventures at that time. It was our first attempt at making art in remote, wilderness spaces. It was a sort of performance of ecological/cultural collision.

SK: How did this experience inform your subsequent work?

LN & CP: As we began to study environmental theory, we realized that not only does little “true” wilderness actually exist, the myth of wilderness was used to obscure the history of indigenous people living on the North American continent. Our own land, we learned, had once been a pasture and had been logged numerous times. Coming to terms with the fact that we hadn’t really retreating to “nature” was the focus of our video Wilderness Trouble which attempts to imagine a new kind of environmental ethics that includes urban and electronic spaces and modern networked culture. However, we still believe that wilderness provides a lot of imaginative potential. Amazement at sublime landscapes can provoke an emotional response that can be politically motivating, and we have tried to take advantage of that potential in our smartphone app Indeterminate Hikes +. By importing the rhetoric of wilderness into everyday life through Google-mapped hiking trails, the app attempts to inspire a sense of ecological wonder at usually disregarded spaces, such as city sidewalks, alleyways, and apartment buildings. We wanted to see what would happen if a walk down a sidewalk were treated as a wilderness excursion. What if we consider the water dripping off an air-conditioner with the same attention that we give a spectacular waterfall in the wilderness?

SK: There is a recurring effort in your work to question the opposition between environment and technology, which is usually accompanied by an ironic undercurrent in your narration and editing that acknowledges what you call “cultural collision”. In Google is a National Park and Nature is a Search Engine which is also part of a series of performances called Center for Wildness in the Everyday (2010), itself conceived as an ecosystem, you suggest that an “environment” is a network of relationships common to natural as well as technological systems, whether it is the ecosystem of a river estuary or Google. Do you see this as a sustainable analogy or a productive contradiction?

LN & CP: Part of what we find frustrating about a lot of environmental thought is that it either wholly rejects technology as the cause of ecological crises so our only solution is to go primitive or wholly embraces technological progress as a saviour, which often means we have to trust in corporate and scientific innovation to lead the way. We think there is another way. We see humans as essentially technical beings: human-animals literally cannot survive without technics. The U.S. military survival guide comes right out and admits that your situation is pretty hopeless if you are stranded in the wilderness without at least a knife. If technology is part of who we are – and we find Bernard Stiegler’s work helpful for thinking this through – then we have also evolved with technology. We are not the same sorts of humans as, for example, Leila’s great-grandmothers in Slovakia or Afghanistan a century ago. The question, then, is not, Yes or No to Technology, but rather, How do we engage technology sustainably and in a way that supports creativity and freedom? And if human beings are technical beings, relying on nature and culture simultaneously, is it even possible to distinguish between what’s natural and what’s not? Isn’t our sustenance dependent upon not only our biological needs (clean air, water and food) but also our cultural practices, beliefs, and imagination? This is why we find it essential to think about electronic spaces and digital technologies whenever we think about the “environment.”

The installation called Google is a National Park and Nature is a Search Engine, a work that is part of a series of performances called Center for Wildness in the Everyday commissioned by the University of North Texas. Our task for this commission was to create a networked artwork about the Trinity River Basin, the source of water for the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex. In the image, the Trinity River looks like a space of natural refuge but the scientists we worked with there explained that the River’s flow is guaranteed only by the recycling of waste water at treatment plants. We wanted to create a work that juxtaposed this hidden constructedness of “nature” with the more obvious man-made Google – two processes or entities that we rely on everyday for our ecological sustenance: water management and online information.

SK: In 2008, you made the Environmental Risk Assessment Rover, a solar-powered module, which gathers and projects information regarding threats in the immediate environment. Although the ERAR is a sizeable aggregate of equipment that is carted around in a wagon, it seems to be the precursor to handy mobile phone apps. How does the ERAR work?

LN & CP: This project is part of our ongoing engagement with science – especially environmental science, which is also a focus of our 2009 work Eclipse. When you work at the crossroads of art and science, as we do, there is often an assumption that the role of the arts in this interdisciplinary exchange is to visualize or communicate knowledge produced by scientists. In contrast, ERAR asks what we learn when science breaks down – or when we use science to “interrupt” experience rather than to predict behaviours. The project arose out of our observations of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s handy yet arguably useless colour-coded terror alert system launched post 9/11 and our experiences with what risk theorist Ulrich Beck calls “science’s monopoly on truth”. Somewhere Beck writes that cows can turn blue next to a chemical plant, but unless science actually proves that the chemicals are the cause of the blue, nothing will be done about the situation. So although other forms of knowing might tell us that the plant is a public health risk, there is nothing we can do until Science “proves” a direct causal relationship. The Rover collects real-time risk data relative to its GPS coordinates, such as car or subway accidents, air pollution levels, violent crimes, proximity of superfund sites, and ground water toxicity, and then determines the aggregate local threat level through a 14-tiered alert system, ranging from “Holiday Shopping” and “Plastic Bags” to “Girls Gone Wild” and “Ask Your Doctor”. Obviously there is a bit of Dada in this work – but not Dada as simple chaos, as it is popularly invoked, but rather Dada as a shocking exposure of the limits of modern reason at the same time as it brings to the surface something that many of us have repressed from consciousness: the subliminal knowledge that there are ways of knowing the world that come from non-scientific experiences and observations. This tension between scientific expertise and everyday experience is also at play in our recent work #TrainingYRHuman.

SK: Have you considered launching it as a phone app?

LN & CP: The ERAR was our first truly mobile work, and it would probably make an interesting phone app – however, the public spectacle it creates is integral to the effectiveness of the work. Pulling around a wagon of technological parts that beams alerts onto the side of buildings is an art action and an effective conversation starter.

SK: Social networks and mobile phone app technology have rapidly become established means of communication and art galleries currently employ these technologies conventionally to replace audio guides. Your current work explores social networks and phone apps as potentially innovative platforms for art. Indeterminate Hikes + (2012) and #TrainingYRHuman (2011) can be accessed in diverse contexts and within everyday activities. They address a broad public, providing a plurality of entry points without necessarily being identified as art. How has the public responded to these projects so far and how do you hope to see them pan out in the long-term?

LN & CP: What motivates us most about working with new technologies is how they can be misused for unexpected purposes. Smartphones, generally, are deployed as devices of rapid communication and consumerism, to get you what you want and where you want as quickly as possible. Our app Indeterminate Hikes + reappropriates this mobile technology for a very different end, turning smartphones into tools of environmental imagination and meditative wonder. It transforms ubiquitous computing into an opportunity to notice the happenings occurring all around us in our local environments, to see sublimity in our backyards, alleyways, streets and neighbourhoods. Like many of our works, this is also a way to aesthetically pose an alternative to environmentalism’s frequent anti-media stance and to popular culture’s uncritical embrace of technology. We want to dream new ways of being without falling into prescribed behaviours or reactionary responses, whether with the food we eat, the technologies we interact with, or the environmental relations we imagine. Foucault’s call for the creation of “gay style” as an antidote to heteronormative culture has always resonated with us in our attempts to rethink dominant ways of being: what is the space of freedom in which one can intervene and express oneself, invent, upend? The mood after our public indeterminate hikes is often euphoric, and participant-hikers comment that they see the world anew. If enabled to be, smartphones can be a platform for chance operations, which, as Allen Kaprow explained, can create “near-miracles”: “when something goes ‘wrong,’ something far more ‘right,’ more revelatory, has many times emerged”. Our app can be used anywhere, any time, by anyone who has an Android phone or who attends our performances, so hopefully there will be many people misusing their smartphones and taking wilderness hikes in the wrong places for a long time. An iPhone version will be released this spring/summer 2012.

#TrainingYRHuman, a work-in-progress, is a participatory Twitter-based net artwork about the agency of animals who live with human-animals as well as an attempt to speak back to science’s monopoly on truth. In recent years, a burst of scientific research has illuminated animals’ behaviours, ethical attitudes, modes of cognition, and psychological awareness, yet usually when we read news of this work, we think: Were all those scientific tests really necessary to figure out that a certain animal species has feelings? Many people who work and live closely with animals already had abundant anecdotal evidence to support the fact that nonhuman animals have diverse personalities and creative problem-solving skills, that they think, feel, and are conscious. #TrainingYRHuman is a gesture toward bringing those anecdotes into the public record, toward creating a sort of oral history database of animal-agency stories that usually only circulate subliminally in our informal conversations. At the same time, it is a moment for human-Tweeters to imagine what it’s like to be a nonhuman animal, inventing unique ways to express oneself and meet one’s needs and desires in a human-dominated world.

SK: There are multiple registers and modes of address in your work and an ambiguity regarding the speaking subject. To an extent, this is because there are two of you, but you also construct voices and use various techniques to create further ambiguity around your agency. Can you elaborate on your strategies of collaboration and decision-making and how these relate to the tension and displacement that you create between the cultural and the technological, the physical and the digital, the artistic and the scientific, the collective and the individual?

LN & CP: Our primary collaborators are each other. Though we have a division of labour, we don’t have a conscious strategy of how we work conceptually, perhaps because we fell into making art together organically, out of collaborating on life. Ideas emerge for us out of an ongoing, sometimes unconscious, sometimes over-analytical, conversation that meanders through the digital/physical places we inhabit, whether we are in our studio or the kitchen. Whose idea it was to add orange juice to our hummus recipe or who came up with facilitating alter-wilderness hikes via smartphones is impossible to figure out. We are committed to an experimentality in process that involves interaction, exchange, exposure, and research that can take advantage of the energy created by blurring the lines between self and other. Proprietary works and the myth of the “genius” artist are detrimental to emerging modes of working, especially with regard to new media art production. Lately, animals have been a significant part of this process for us, shaking up our stale human behaviours and assumptions, especially the cows, sheep, and pigs we visited recently at the Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glen, NYState, and the birds of prey we met through a local bird sanctuary called Friends with Feathers.

We can’t really say with authority whether our extended collaboration relates to the ambiguities of our artworks. However, we do try to welcome the breakdown of categories like digital, physical, human, nature, and animal as well as media, disciplinary, and environmental boundaries. What really is a “human”, and why has there been this historical obsession with somehow distinguishing humans from animals, as if we are somehow specially different from every other animate being on earth, more evolved and complex? As eco-critic Timothy Morton said recently, “According to evolution science, there are two things humans do very well, but they are a bit of an ego blow: throwing and sweating. Everything else is also done by nonhumans, including consciousness, feelings, art, tool use”. So we are simply sweaty throwers who think very highly of ourselves! It seems to us that the effort to hold tight to definitions, to reliable knowledge, or to the self blocks the more interesting conflations that happen (or are already happening) when we let categories slip away. Therefore, rather than try to determine, define, and predict in our art, we are more interested in staging fluid experiences that ask difficult questions and interrupt our sense of certainty. When assumptions fail, things fall apart, and we can’t depend on what we think we know, that is when our most creative thinking takes place. These are exciting, experimental moments.

Leila Nadir and Cary Peppermint founded Ecoarttech in 2005. They teach Video Art and Sustainability Studies at the University of Rochester in New York and they work with a range of institutions, including the Whitney Museum, Turbulence.org and the University of North Texas. They have exhibited at MIT Media Lab, Smackmellon Gallery, European Media Art Festival, Exit Art Gallery and the Neuberger Museum of Art. In June 2012, they will be artists in residence at Joya: Arte+Ecología, an off-the-grid residency program based at Cortijada Los Gázquez in Parque Natural Sierra Maria-Los Velez in Eastern Andalucía.

Featured image: Martijn de Waal, co-founder of The Mobile City, introduces the conference (image courtesy Virtueel Platform)

On Feb. 17th Amsterdam hosted Social Cities of Tomorrow, a conference on new media and urbanism. Adapting its title from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow, but taking equal inspiration from the work of Archigram, the conference presented a snapshot of the direction cities are moving today: as conventional means of planning and designing are renegotiated through our engagement with new media technologies:

Organized by The Mobile City and Virtueel Platform, the event showcased best-practise examples of the use of media in urban analysis, design, art and activism. These ranged from “Homeless SMS”, a text-messaging system designed to provide information to the 70% of homeless Londoners who own cell phones; “Amsterdam Wastelands”, an on-line mapping of disused sites in Amsterdam and Zaanstad; “Koppelkiek”, a game project in which residents of a troubled area of Utrecht collected “couple snapshots” (in couples of friends, relatives or complete strangers), promoting social interaction through play; and “Urbanflow”, and New York-based project to rethink the contents of urban screens. In all, a dozen such projects were presented at the conference.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/showcases

Immediately preceding the conference an intensive three-day workshop took place at ARCAM, the Amsterdam Centre for Architecture. This event brought together two dozen interdisciplinary creatives from around the world to tackle urban issues in four current case-studies: Haagse Havens, Den Haag; Zeeburgereiland; Strijp-S Eindhoven; and the Amsterdam Civic Innovator Network (a proposal to open up Amsterdam’s civic resources to distributed control by citizens). Working with local stakeholder organizations, the participants brainstormed how to leverage new media to solve intractable or new problems in these real-world sites.

http://www.socialcitiesoftomorrow.nl/workshop/the-four-cases

Also at ARCAM, a roundtable discussion on the alternative forms of trust emerging out of new media conditions was held, with panelists (below, left to right) Tim Vermeulen, Henry Mentink, Rietveld Landscape, Scott Burnham, Michiel de Lange (image courtesy Aurelie).

Keynote speakers Usman Haque, Natalie Jeremijenko, and Dan Hill concluded the conference with a panel discussion that placed the presentations in the context of distributed technology, contemporary art, social innovation, and architecture (image courtesy Virtueel Platform).

Playing Hard: Urban Art Games of Summer 2010.

Not long ago, urban games were a kind of novelty. Some grew out of the street performance tradition of live theater. Some came from gamers who were involved in tabletop RPG and wanted to experiment with live reenactment. Others were produced by media artists as a way of experimenting with new technologies like GPS and text messaging. But along with these approaches to play, and at times learning from their carefree attitude towards entertainment, there grew another tradition of the urban game, a tradition of using the city focusing on exploration, and as a specific kind of critique. At its worst, the artist produced street game replicates of hollow self-promotion, through corporate, sponsored seasonal festivals. But just as experimental art can involve an analysis of mainstream art, the urban game can embody a palatable critique of the routines of city systems, including the deadening routines of metropolitan life and some of the large scale mechanisms of corporate capitalism.

These kinds of games echo the spirit of the Situationist International, which called on artists to create alternate experiences through the construction of situations, psychogeography, and the use of play as a form of critical thinking. Urban games can also remind us of Hakim Bey and his idea of a Temporary Autonomous Zone by using goals, rules, and play with the creation of the ‘magic circle’, a world inside a world, as a method of directing public imagination towards an alternative presence, a way of acting and existing as an independent community within a larger, more repressive reality, even if only momentarily. Urban games also continue the Fluxus idea of the ‘happening’, a participatory media form in which audiences support artists, moving beyond the role of observers of performance to become collaborators in events. With the urban games season about to begin, this review takes a look at how several groups, either consciously or at times not so consciously, have interpreted these traditions for summer 2010.

In New York, the much loved Come Out and Play Festival will run from June 4th through June 6th, with events scattered throughout the city borough of Brooklyn. Games include playground mods, GPS exploits, extreme sports, narrative quests, and massively multiplayer scavenger hunts. The festival hosts about forty game designers from around the world and about two thousand people will attend. Executive producer Greg Trefry says COaP strives to be entertaining and is not so much concerned with philosophy as it is with place: “Where the festival is located each year is actually really important to us. We look for interesting parts of the city to experiment on and use as the stage for the festival. So we’ve played everywhere from big anonymous urban areas like Times Square to now more family oriented locales like Park Slope.”

Still, the designers of COaP seem to have a way of engulfing serious issues with comedy and encouraging people reclaim neglected parts of the city by giving them a second look. Along these lines, Atmosphere Industries of Toronto will present Gentrification, a game that picks up on Brooklyn’s ongoing housing conflicts by asking players to assume the roles of real estate developers or neighborhood locals while collecting properties and gentrifying neighborhoods. Meanwhile, Gnarwhal Studios of Baltimore will sponsor ‘Humans vs. Zombies’, a modification of the playground game tag that introduces large groups of strangers to one another by sending players out into the city as the walking dead.. It’s hard to sit in a park, completely shut off from everyone around you, during a two hundred person simulation of a zombie attack. Also part of COaP, New York’s Crux Club will confront community fears of toxic contamination through their game ‘It Lurks in Gowanus’, a hide-and-seek mod that asks participants to track down a creature who has ominously escaped from legendary pollution of the neighborhood’s Gowanus Canal.

Although he agrees that all urban game events take some kind of cue from historical antecedents like the Situationist International or Fluxus, producer Trefry resists making a formal connection between these movements and COaP. Instead, he says, the main concern was and continues to be community building, getting people together in a surprising way and in an unexpected space: “At its heart, the festival is about running around outside and having fun with your friends. It sounds silly, but that’s such an amazing thing to experience.” This goal of community building has caused COaP to inspire other urban games festivals, including the Hide & Seek Festival in London and the igFest in Bristol, and the Steel City Games Fest in Pittsburgh. The organized versus the random, or the juxtaposition of the carefully designed structure of a game with the largely unstructured, seemingly arbitrary activity of ordinary public space continues to be a common interest among COaP design groups, which are likely to include engineers, academics, and urban planners alongside artists and actors.

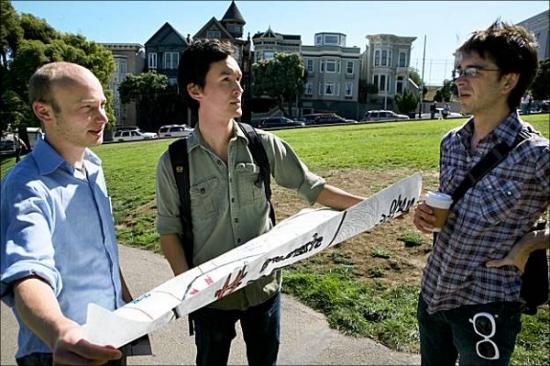

In San Francisco, the artists of SFZero cite Situationism and Fluxus as fundamental to their practice. The SFZero collective was founded by Ian Kizu-Blair, Sam Lavigne, and Sean Mahan in January 2006. Initially, the group used something like a Fluxus process of writing instructions for happening-like events that teams of other players acted out. Soon, these collaborations became the basis for both an online community and real world urban games network that now include over five thousand players. Through the SFZero website, participants initiate events by challenging other participants to ‘Eat a food that frightens you’, or ‘Go to a street corner of your choosing and wait for something fantastic to happen.’ SFZero seems to agree with classic Situationist objectives. A good game shifts awareness, Kizu-Blair says, changing the city for the people who play: ‘Oftentimes the players report that they have a completely different experience of the urban environment as a result of playing and go to places in their city where they have never been before. There is a cinematic quality whereby players live out experiences that normally exist only in spy movies – chases down dark alleys, chance meetings, etc.’ Typical SFZero tasks range from exploring overlooked locations in the city to taking a chance on meeting new people.

As fantastic as some of these instructions sound, and as important as the Internet is to SFZero’s success, Kizu-Blair says it is essential that some productions have a real world component: ‘As people become disenchanted with eight plus hours per day of screen time, they are increasingly gravitating towards hybrid activities that bridge the space between the virtual imaginary and the physical real world. These activities blend the safety and simple pleasure of screens with the risk, tension and excitement of physical interaction. More and more, members of our society will seek to escape from escapism towards an ethics of action, to escape from movies to real experiences. They will find that they have little idea how to have real experiences after their time in the imaginary. SFZero is the transition. ‘SFZero offers both real-world excitement and eternal return to the screen, to re-live, re-experience and re-imagine your engagement with reality.’

Recently, Kizu-Blair, Lavigne, and Mahan have begun staging riskier, more elaborate game events like ‘Journey To the End Of Night’, in which runners try to make it through six checkpoints on foot or by public transportation, while avoiding capture by chasers. An early version of Journey actually opened the 2006 season of Come Out and Play. This July, the veteran SFZero player Lincoln will stage a further production of Journey in Los Angeles.

This summer, SFZero will present The Wanderers Union, a game that is loosely based on a French style of self-supported long-distance cycling called randonneuring. To perform Wanderers Union, players get a set amount of time to travel on foot and by public transportation through a series of zones. The idea is to create a single holistic experience of a urban area. The journey intends to juxtapose city spaces in ways that reveal meanings that might otherwise remain unobserved. Players who complete all of the events will progress from an initial four hour wandering to a final twenty-four hour wandering. By using play as a means of gaining understanding, participants will hopefully gain a small degree of mastery over urban space. Kizu-Blair says: ‘It’s like a video game – you level up and gain powers – but you have the added satisfaction of doing something real, and you can include anyone in the experience.’

Back on the East coast, the New York based artist’s collective Opt-In found that what started as a thesis project for an experimental film class unexpectedly became a series of multimedia events that now includes filmmakers, fine artists, dancers, performers, and musicians. Titled ‘ZeroDay Exploits’, these evenings are the work of Bryn Jackson, Sarah Lerner, and Nathaniel Barker, who says the group has adapted the Fluxus concept of “happening” to the 21st century: ‘We create immersive environments in which strangers and friends can form new communities around a project, an idea, or a simple good time. We bring people from all walks of life together by promoting open dialogue and the creative expression of public discourse through a vast array of mediums and the use of public space.’

Past themes for the Opt-In exploits have included faith and technology. This July, the group plans to explore the idea of “home” by inviting guest artists and guests to contribute items and materials that evoke a sensation of home. The goal of this event is to create a sense of rootedness in New York, a city of perpetual resettlement. Another major goal for Opt-In is the deconstruction of the digital experience through live performance. According to Barker: ‘Our focus has always been on participation, so our events offer multiple means for encouraging visitors to get their hands dirty including music, secret actors to stimulate conversation, inclusive performances, and free art materials for spontaneous art creation.’

Also related to Fluxus, but in a gesture that seems more directed towards the Brazilian director Augusto Boal, a group calling themselves Invisible Playground Berlin, uses the urban game as a kind of political visualization. Founded by the artist known as Sebastian Quack Sebastian, this group’s interests lie at the intersection of theater and digital gaming. In ‘F Be I, See I A’, Invisible Playground re-enacted peer-to-peer communication as a giant game of urban capture the flag. Later, in Space Station Escape, the group simulated the release of an alien virus inside a phantom space station supposedly docked underground beneath Alexanderplatz.

Sebastian views missions and rule sets as ‘experience systems’, Games are a kind of participatory appropriation, an interrogative code that is placed over or enacted within an existing urban mechanism. In other words, if you want to get people to think more critically about the way immigration works in your city, you’d design a game that plays with the existing locations, activities, and mechanisms of immigration. In this way, Invisible Playground intends to put forward what otherwise goes unnoticed, tolerated, or is even passively accepted. Sebastian is careful to structure his rule sets in ways that highlight the power structures that arise between groups of players, between players and their environments, or between players and organizers. According to the Schwellenland site: ‘Players must work together and against each other. Over SMS and email you are guided to appointments and arrive at places where you were barred from entry until now. The game asks you to decipher who is legal, who is questionable, who can be trusted, who will trust you, who observes you, what should be ignored, what is critical. You are accompanied by a coach and by referees who left the usual national borders behind long ago and are now in Vienna as refugees without papers. These specialists can help you to master the challenges of being from a developing country. But they have also power to turn on you if you make too many errors.’

Finally, with a practice based in both New York and in Brazil, Adriana Varella is one of the artists behind the AnarkoArtLab, a collective of new-media, visual, dancers and genre benders in residence at the Living Theatre. Each month, Anarko creates a multimedia event that runs as part lab, part performance. This summer, the group plans to become mobile and to bring the Lab to different situations and neighborhoods. ‘We are searching,’ Varella says ‘for a last trace of that most ephemeral and elusive state where only a dusty dystopian haunting may yet remain. ‘Of course,’ Varella says, ‘all of them, Dada, the Situationists, Fluxus they are all our ancestors.’

Marc Garrett: You are an artist who works solo and with others in various ways. A large body of your work consists of performances, interventions and sound recordings. I want to begin this interview by asking, why you decided to form ‘The NeoFuturist Collective‘, and what was the main mission or purpose behind such a collective?

Joseph Young: The NeoFuturist Collective was born as a convenient way to house a piece of work I was making called ReAwakening of a City. The idea had started as part of a practice-based PhD at SMARTlab UEL, but as soon I got funding for the project from the Arts Council, I realised I didn’t want to spend the next four years writing about it…

I invited a group of artists to join me in making a collaborative piece of work from a seemingly simple premise – the transformation of urban noise, inspired by futurist artist Luigi Russolo’s Art of Noises manifesto. Russolo had created a series of “noise networks” or symphonies for his mechanical intonarumori (noise makers) back in 1914, and in so doing he had influenced the entire course of 20th century music.

Despite his contemporary resonance, little is generally known about Russolo’s work, as all of his instruments were destroyed in the intervening two world wars. Of the scores he wrote, only the first 7 bars remain of Awakening of a City, and that only because it was reprinted in the art magazine Lacerba. Apart from the fragment of written score there are letters, reviews, photographs and other forms of documentation which have led researchers and artists over the years to try and recreate his noise making instruments.

Our project is rather different – we use the remaining 7 bars as the starting point for a new piece of work, ReAwakening of a City, engaging with all forms of visual and aural urban noise that we spend so much time trying to block out. Traffic noise, junk emails, health and safety warnings, advertising and street furniture. The form is performative, visual and mediated as well as musical, using all available means at the disposal of the 21st century artist.

By engaging with my artist-collaborators’ practices, I commission work that responds to this central idea and then set up an appropriate curatorial context for extending that individual response into a collective noise network.

MG: Where did these ReAwakening of a City events happen, and what kind of response did you receive when these performance, interventions took place? How important was it to connect with others – every day people, whilst engaging in the process of expressing these real-life experiments?

JY: The first ReAwakening took place in Brighton in Feb 2008. We started off the project by declaiming the NeoFuturist manifesto (written by Rowena Easton) in Jubilee Square, with a bunch of workmen and their drills providing a fabulously appropriate accompaniment to the text which celebrates Urban NOISE. (The manifesto can be downloaded from www.neofuturist.org). The crowd then followed us onto the Arts Council offices where we laid a wreath on their steps in support of all the companies that had been recently cut – we were ourselves in receipt of Arts Council funding at the time. A classic case of biting the hand that feeds you. Our activities provoked mild amusement and little controversy however, as the good citizens of Brighton & Hove are used to seeing “crazy” artists peddle their wares in public.

A couple of months later we had our first performances of work-in-progress at The Basement, Brighton. The reaction here was far more hostile and interesting, with some audience members questioning our politics in the Q&A session afterwards, accusing us of proto- fascism. Actually the level of debate was thrilling, as we really touched people’s buttons and ended in a deep discussion about the impact of the Futurists and their relevance to the current political climate. This question surfaced again a few of months later in an online interview with The Thing Is… magazine.

We were fortunate after that to be invited to make a piece of work on Wall Street in New York for the psychogeographic festival, Conflux. Our proposal was to make a walking performance that explored the everyday experience of living and working in the Wall Street district and how this might inform our understanding of the impact that this small area of real estate has on the rest of the planet. We arrived on September 11th 2008 to be met by 9/11 conspiracy theorists on street corners, and proceeded to spend several days mapping the area through sound recordings, text and video in preparation for a dawn performance on 14th September – a ReAwakening as the city awakes. The effect was dramatic and unexpected, as my declaration of the NeoFuturist manifesto outside 1 Wall Street brought about the collapse of Lehmann Brothers that weekend and the subsequent domino effect on the global economic system. Sorry world!

Our next major intervention was more low key, but no less dramatic as we were commissioned by Fuse Medway festival to engage with and inspire the village community of Upnor. Our mission was to get the people to take to the streets in a protest/celebration march. We worked with the community over a number of months, holding public workshops and meetings, networking furiously in the local pub (one of four!) and it soon became clear that the general apathy towards the arts, and outsiders in general, meant that if the public were not going to come to us, then we would have to go to them. So we took to the streets and made work in public which enraged some, who questioned where our funding had come from, but delighted others and built a momentum towards our final performance.

A Call to Arms (as the piece was finally called) took place in June last year and was a very successful example, I think, of how one can make “community art” challenging as well as accessible. See http://neofuturist.blogspot.com for full documentation and a film of the performance.

Other pieces of work, include shouting at the Futurist paintings with a megaphone, as part of the Tate Modern Futurist retrospective last summer. An experience as liberating as it was faithful to the original spirit of futurism, causing equal anger and delight amongst an unsuspecting public. I was also invited as a panellist to take part in a public debate along with other luminaries from the art world, on the subject of “Is the Avant Garde Passe?” organised by The Institute of Ideas in London. Here the public paid to witness a lively and informed panel discussion around the relevance of contemporary art, proving, it seems to me, that there is a real appetite for intelligent, politically driven commentary and debate.

A group of artists drawn from the fields of visual, performance, video and sound art will attempt to transform the everyday language of urban sounds and visual junk (such as spam emails and billboard advertising) into a true multi-media experience to do just that; asking us to question our assumptions about what is beautiful in a modern world of information overload.

MG: Your comments that contemporary art is in need of intelligent, politically driven commentary and debate rings true. In respect of my own art context(s). Thinking of the many amazing self-organised, networked communities, of which there are many, on-line and in physical space; there has been a massive shift of art creating, moving independently, yet in parallel to the ‘official’ and hegemonic examples accepted or considered contemporary at the moment. Of course, if we think about what contemporary means itself, it means existing, occurring, or living at the same time. The relationship between institutions and art which is actively critical and more challenging than easier processed art such as Brit Art, how they represent contemporary art.

Considering the history and knowledge we have regarding the original Futurist movement, and its close connections with fascism. For instance, what is less known is that, the Futurist movement did not only consist of fascists, but within it there were also socialists, anarchists, leftist and anti-Fascist supporters. Consisting of interesting individuals such as Georges Sorel, who explored his own views and intellectual thinking, right across the political spectrum. Georges Sorel “…was a voluntarist Marxism: he rejected those Marxists who believed in inevitable and evolutionary change, emphasising instead the importance of will and preferring direct action. These approaches included general strikes, boycotts, and constant disruption of capitalism with the goal being to achieve worker control over the means of production.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Sorel

I can see a direct link from Sorel’s activist approach and The NeoFuturist Collective’s ReAwakening events and performances. Of course, there are some other pretty good contemporary art activists out there at the moment, who also incorporate performance as part of their creative process; such as ‘The Office of Community Sousveillance’. “This work rests between legality and illegality. By posing as security officers, ‘PCSO Watch’ imaginatively play at the borders of what is typically deemed right and wrong, real and unreal, pushing their expression in the form of political enactments and direct action. This is a paradigm shift, not particularly interested in the art critic’s perspective.” http://www.furtherfield.org/displayreview.php?review_id=338

“Futurism has produced several reactions, including the literary genre of cyberpunk — in which technology was often treated with a critical eye — whilst artists who came to prominence during the first flush of the Internet, such as Stelarc and Mariko Mori, produce work which comments on futurist ideals.” The legacy of Futurism. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futurism#The_legacy_of_Futurism

With the understanding that there have been various influences, mutations and re-appropriations from the Fururist movement, I am wondering what elements you feel or think are still important to reclaim, reshape and reintroduce into a contemporary world, both in respect of the art arena and in relation to our everyday environments?

JY: What interests me in relation to the Milan Futurists is, first of all, the misperception, as you have pointed out, that futurism was primarily a fascist movement. My understanding is that Marinetti was the only artist to have that association, having been invited to serve on the Central Fascist Party Council after the First World War. He resigned not long after as soon as the Catholic Church was also invited to sit on the Council – Marinetti being an avowed atheist. This is not to excuse the entire movement of this problematic association, but it does put it in context. It also recognises that a spirit of optimism and a belief in technological solutions to the world’s problems, that futurism embodied, also has its’ darker side. And it is with this knowledge that I choose to engage with (neo)futurist ideas in the 21st century, as it seems to me, that in a world seemingly on the verge of collapse, that a spirit of positivity renewal is both urgent and necessary, and also the ultimate political gesture.

You mention various artist collectives that have appropriated the futurist legacy in this way, and to that I would add Ultra-Red who, incidentally, published a short sound piece of mine, recorded on Wall Street during the crash of 2008, as part of Fifteen Sounds of the War on the Poor vol.3.

In order to engage with the state of the planet, artists can no longer cling to romantic, utopian notions of nature/beauty in opposition to man/technology. This dichotomy seems to represent more about human self-loathing than it does about a workable solution to global warming/terrorism/the energy crisis/reform of global capitalism, etc. Moreover it leads us towards a new “medievalism” (ban air travel, ban cars, buy local) that is all too prevalent in ecological pressure groups. In this argument, man has brought us to the edge of destruction, therefore we must drastically scale back all of our wealth-producing activities. As if the (post)modern world could be wished away in either Luddite vision of the future or more worryingly in the ideology of The Zeitgeist Movement, whose apocalyptic vision of a radical eco-future involves tearing down our cities and rebuilding them.

This thinking is also represented in the work of acoustic ecologist and renowned nature recordist, Bernie Krause in his article, Anatomy of the Soundscape: New Perspectives, Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, Jan/Feb 2008 Vol. 56 Number 1/2, Pg 73-80 (2008), in which he dissects the soundscape (a term first coined by R Murray Schafer in Soundscape: The Tuning of the World) into 3 separate strata:

“GEOPHONY is framed as natural sounds emanating from non-biological sources in a given habitat.acoustic variations. BIOPHONY By far the most complex and laden with information, this unique feature of the soundscape is comprised of all of the biological sources of sound from microscopic to megafauna that transpire over time within a particular territory. ANTHROPHONY, defined as all of the human-generated sounds that occur in a given environment: physiological (talking, grunting, body sounds), electromechanical, controlled sound (music, theatre, etc.), and inci- dental (walking, clothes rustling, etc.).”

In this breathtaking philosophical leap, Krause removes the human from the natural environment and pits him/her in opposition to it. In creating a separate category for human sound activities outside of the biophony (i.e. the sounds of all other species on the planet), he is both over-stating human control and dominance over the environment and also denying us a role in the Gaia hypothesis – one of the green movement’s central texts, that views the Earth (and all of its inhabitants) as a single organism.

I am certainly not refuting or seeking to contradict many of the arguments regarding human sound activities and stress levels, posited by the World Soundscape Project, of which Krause is a prominent member, but it is worrying that so many eco-activists see humanity as a problem and not as a solution. And this is where Futurism and its antecedents/mutations can offer a way forward…