The first interview with Jake Harries, took place on one of Furtherfield’s Radio broadcasts on Resonance FM, earlier this March 2011. Fascinated by the historical context that came out of the radio discussion, we asked Jake for a second interview, this time it took place via email.

Jake Harries has been making music in Sheffield since the 1980s and is a sound artist, musician/producer, composer and field recordist with a strong interest in media art and the practical use of Open Source audio-visual software. He was a member of electronic funk band Chakk which is best known for building Sheffield’s first large recording studio, FON Studios, in the mid 1980s. He is currently one of “freestyle techno” trio Heights of Abraham and The Apt Gets, a band which uses guitars and only Open Source software on recycled computers to create songs from spam emails. He is Digital Arts Programme Manager at open access media lab, Access Space, and the current curator of the LOSS Linux Open Source Sound a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS.

Marc Garrett: Lets talk a bit about your own history first. You were in a band in the 80s called Chakk, could you tell us a bit about that?

Jake Harries: Chakk was based in Sheffield during the mid 80s and we are best known for building a heavily used facility, FON Studio, Sheffield’s first large commercial recording studio. Chakk made “industrial funk” music, a mix of funk base lines and drums with influences ranging from punk to soul to free jazz and electronica. Our music was aimed squarely at the dance floor. We believed that technology, in this case the recording studio, was the most important instrument a band could have both creatively and financially.

MG: So, you are part of the electro music history of Sheffield with bands like Cabaret Voltaire & The Human League in the late 70s – 80s?

JH: Yes, but the band itself didn’t have too much commercial success, a couple of indie chart top 10s and a couple of low 50s in the main UK chart, so few people remember us now. People are more likely to remember FON Studio.

Recently a documentary has been made, called The Beat Is Law, about Sheffield music at that time, so perhaps there will be a bit more interest in the band.

MG: Open Source software is freely downloadable from the Internet for free and Linux is the most widely used Open Source operating system. How long have you been using Linux operating systems and Open Source?

JH: I had heard of Linux before, of course, but I came across music applications which were developed only for Linux in 2002-3 while searching for new software tools. These intrigued me sufficiently to install the operating system on a pc which I had fixed where I was working at the time.

MG: Do you feel that artists, techies and others are choosing Free and Open Source resources for reasons which connect with ethical and environmental issues and concerns?

JH: Well, I’d like to integrate into this answer the general themes of openness and transparency. FLOSS is akin to an encyclopedia of how to make things in the software realm because all the code is available for anyone to download and develop; closed, proprietary software is like a “sealed box” which it is illegal to prise open.

But it goes a bit deeper than that: in the world we are living in now the “sealed box” is increasingly becoming the mode of choice for all kinds of products, most of which, because they are designed to be superseded, have built in obsolescence. When something goes wrong with a product, you are unable to fix it yourself because you can’t get inside it, and even if you could you can’t find out how to fix it. If it is out of warranty, either you pay a lot of money to get it fixed or you throw it away; then you buy a new one! (Which is what the market wants you to do…)

So, it feels very much as if we are surrounded by technology we are not encouraged to understand and products with a limited life span: the obvious environmental concern is, “what happens to my ‘sealed box’ when I throw it away?”

Using a Linux operating system can increase the useful life of a computer by several years, and perhaps, if you can hack into them, other products too. So it is great if both hardware and software are open.

We also know that sharing knowledge is generally considered to be a good thing as it allows people to build on what has already been discovered. Being able to give the people in workshops the software they have been learning to use because it is FLOSS, rather than them having to pay several hundred pounds because it is only available on a commercial license, is great and often the idea of this kind of freedom takes a while for people to get used to if they’ve not come across it before.

MG: Why is it important as a creative practitioner to be using Open Source?

JH: Well, personally, I have realised that what I’m interested in is freedom, not just as a hypothetical, but the practical reality, finding out how to achieve some of it and if it is possible to sustain it. Free & Open Source operating systems and software are one way of stepping out side of the constant pressures of the commercial market places which dominate our culture.

We tried this in Chakk in the 80s with FON Studio, attempting not only to personally own the means of producing our music, the studio (allowing us to be outside the corporate system of production), but also to be able to explore our creativity in the way we wanted to. In the case of Chakk it didn’t work out. We had, rather cheekily, persuaded a giant corporate (MCA Records, owned by Universal) to bank roll it all and they found ways of scuppering our plan by making our product conform to their idea of the market place: transforming it into something “radio friendly” and bland, taking the energy and urgency out of the music. We were quite a politicised band and that energy was essential to our musical integrity.

However, when MCA dropped us we had a recording studio which could help nurture new music without too much external pressure, and this led to records produced there by local acts fulfilling their potential and going into the charts.

I think it is important for artists to have certain freedoms, to have ownership over the means with which they create their work. The fact that FLOSS allows you the user the potential of customising the tools you use and to distribute them freely via the web or other means is quite profound. And one of the real benefits of using FLOSS as a creative practitioner are the use of open standards and formats.

MG: OK, let’s move onto your own band: The Apt Gets. Now, since The Human League & Cabaret Voltaire, a whole generation has experienced the arrival of the Internet. Your group seems to reflect this aspect of contemporary, networked culture – a kind of Open Source rock band. Could you tell us about this band The Apt Gets, how you all got started and why?

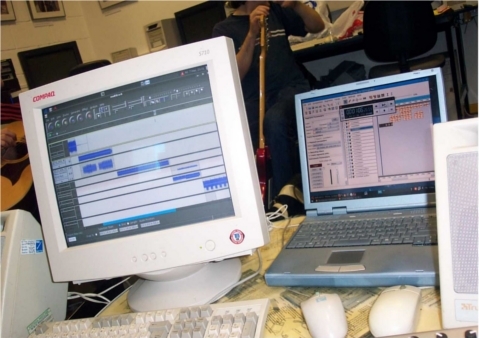

JH: It began with workshops I was leading for musicians on FLOSS audio tools in 2007. The idea of an “open source rock band” came up – at the time we didn’t think there was one so a couple of the workshoppers and myself formed one. The Internet was the main source of inspiration really: we used recycled computers with Linux we’d downloaded, as well as guitars and vocals. I’m interested in re-purposing junk as raw material for creative processes and decided to re-use some of my spam emails as lyrics. We all hate spam, but re-contextualising it like this is fun, as is introducing a song by saying, “Here’s a classic Nigerian email asking for your bank details”. The themes of spam emails are generally things like greed & money, status & sex appeal as well as “meds”, so there’s more to them than you might think.

MG: Now, I personally know why, but others who are not as familiar with Linux and Open Source Operating systems, will not immediately know this. The naming of your band’s name – it’s specific to installing software. Could you tell us more about that?

JH: On a Debian Linux based operating system one can install software from the internet using an application called apt. One could type apt-get install the-name-of-the-software into the command line and apt will get the software from what is called a repository on the Internet, where the software is stored for download. We thought that if you called someone an Apt Get it could be interpreted as an insult meaning something like, clever bastard. So, that’s why we named the band The Apt Gets.

MG: How long has your research project with FLOSS been going?

JH: The research project started in 2007. Ever since I began to use FLOSS I’ve been interested in the practical realities of using it, particularly as an every day set of tools, as an ordinary computer user would use it: for instance, when I do work on the arts programme at Access Space I don’t use anything else. So, it made sense to discover how a number of non-Linux using musicians would find using FLOSS audio tools – if I was being an advocate for FLOSS I ought to look at it from the new user’s angle and discover how far they could go and what kind of time scale they need.

MG: And the web site address is?

JH: http://audiotools.lowtech.org

MG: How easy is it for someone with little or no experience of Open Source software and Linux based operating systems to install it?

JH: It is quite easy nowadays. A Linux distribution like Ubuntu has an easy to follow installer which allows you to create a dual boot if you want it, that is, keeping your Windows system as well so you have the choice of both.

MG: At Access Space in Sheffield, you are curator and researcher of LOSS (Linux Open Source Sound) a website dedicated to music made with FLOSS – which is basically LOSS with the letter ‘F’ added, meaning ‘Free Linux Open Source Sound’ – FLOSS!

JH: Yeah! Free is the word! It is a repository for music made with FLOSS tools and released under a Creative Commons license. You can freely download and upload tracks. Initially it was based around two projects, a physical CD issued in 2006 curated by Ed Carter, and LOSS Livecode, a mini conference and gig curated by Alex McLean and Jim Prevett based around the international livecoding community. The website is at http://loss.access-space.org.

MG: What is Access Space and what is different about them as a group?

JH: Access Space is an open access media lab, based in central Sheffield. It uses reused and donated computer technology to provide Internet access and Open Source creative tools, free of charge, five days a week. It started in 2000 and has become the longest running free Internet project in the UK.

We recycle computers, put on art exhibitions, creative workshops and sonic art events. We’re currently developing a DIY Lab, modelled on MIT’s FabLab or fabrication laboratory. This will be an interface between the physical and digital domains where new kinds of creative activity can be developed.

MG: What operating systems would you suggest to newbies coming to Linux for the first time?

JH: Ubuntu or its derivative, Linux Mint, are both very user friendly for everyday use. For audio try Ubuntu Studio, 64 Studio or Pure:dyne.

MG: And regarding yourself, what are you using?

JH: I have set up eight Ubuntu Studio pcs for use in audio and video workshops at Access Space; and I use Pure:dyne live DVDs if I’m out and demonstrating on other people’s pcs. For everyday use, again Ubuntu Studio with a few additional applications like OpenOffice.

MG: Thank you for a fascinating conversation.

JH: It was a pleasure…

Open Access All Areas: an Interview with James Wallbank about Access Space by Charlotte Frost

http://www.metamute.org/en/Open-Access-All-Areas

Ubuntu Studio 11.04 release.

http://ubuntustudio.org/

64 Studio Ltd. produces bespoke GNU/Linux distributions which are compatible with official Debian and Ubuntu releases. http://www.64studio.com/

Puredyne is the USB-bootable GNU/Linux operating system for creative multimedia.

http://puredyne.org/

Pure:dyne Discussion, interview by Marc Garrett & Netbehaviour list Community 2008.

http://www.furtherfield.org/interviews/puredyne-discussion-netbehaviour