3 October 2019 – 5 January 2020, Daily. Free Entry

The roar of an airplane is a familiar sound for many parts of west London, home to one of the busiest airports in the world and the subject of a new exhibition, Air Matters at Watermans Arts Centre in Brentford, just a few miles away from Heathrow.

Echoing the experience of hearing an aircraft in action, sound itself plays an integral part in the show and leads with The Substitute (2019) by Hermione Spriggs and Laura Cooper. Through overhead speakers outside the main entrance, visitors are greeted by an authoritative voice musing on the fate of local flocks in an airspace strictly controlled by humans and their contraptions, intermittently reciting names of affected birds like a tribute, and ultimately urging listeners to “work with nature” which sets a critical tone.

The audio installation is reminiscent of public announcements at airports, a strategy that continues into the foyer with Frequency (2019) by Louise K Wilson. It features intimate anecdotes of air travel through resonance devices on a skylight roof where planes might fly by at any moment. Speaking softly akin to ASMR, one person wonders about the destinations of travellers, while another recalls vivid memories of flights that seem traumatic, bouncing back and forth between excitement and anxiety.

The theme reaches its crescendo inside the gallery, with a mixture of ambient sounds reverberating across the space from Ascending Composition I (For Planes) (2019) by Kate Carr, an atmospheric concoction of incidental noises recorded around Heathrow including birds, markets, and trains on tracks. With pocket-sized media players attached to deconstructed speakers on strings of fabric, the installation documents an intervention that already took place when the work itself flew up on balloons blasting whispers from the ground, a small but meaningful gesture challenging the sonic waves of jumbo jets that dominate the surrounding sky and soundscape.

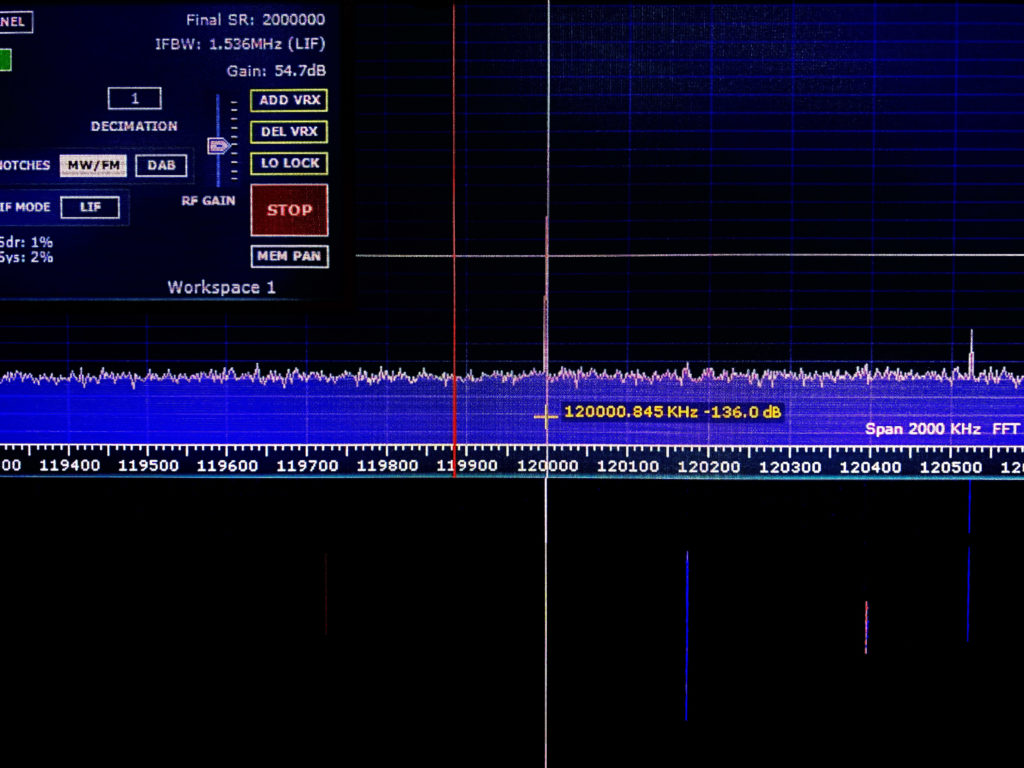

This act of defiance flows into Skyport (2019) by Magz Hall, a mixed media installation with a set of frequency scanners emitting an unsettling static. The title refers to a pirate radio station based along a Heathrow flightpath in the 1970s, illustrated with archival images and texts from an attempt to reclaim airwaves colonised by traffic control and engine noise. The work emulates this spirit with an LCD screen broadcasting airport channels as visual wavelengths, the contents of which are protected as classified information in UK law, consequently questioning ownership, access, and authority over radio frequencies.

The symphony of sounds become unavoidable throughout, and there is a possibility that it might grow vexing for some, perhaps more so for the people that work here who may not have a choice but to hear it again and again. Yet, as irksome as that might be, it is a crucial part of what makes this show effective. The audible pieces collectively transform the spaces into simulations of airport lounges and peripheral towns, simultaneously mimicking and counteracting oppressive noises from airplanes and terminals that have become inevitable in contemporary life, irrespective of its value and/or harm.

Beyond aural tendencies, the exhibition reaches further by considering scale and movement. The sheer volume of Capsule (2019) by Nick Ferguson is an imposing presence in the gallery with a wooden sculpture modelled after the wheel bay of a Boeing 777, floating a few inches off the ground and hovering over visitors. Shown alongside printed images of microscopic substances found in a real plane, it orchestrates a juxtaposition between the enormity of a flying machine and the imperceptible residue it accumulates, revealing traces from the many places it has been including sand, spores, and bacteria.

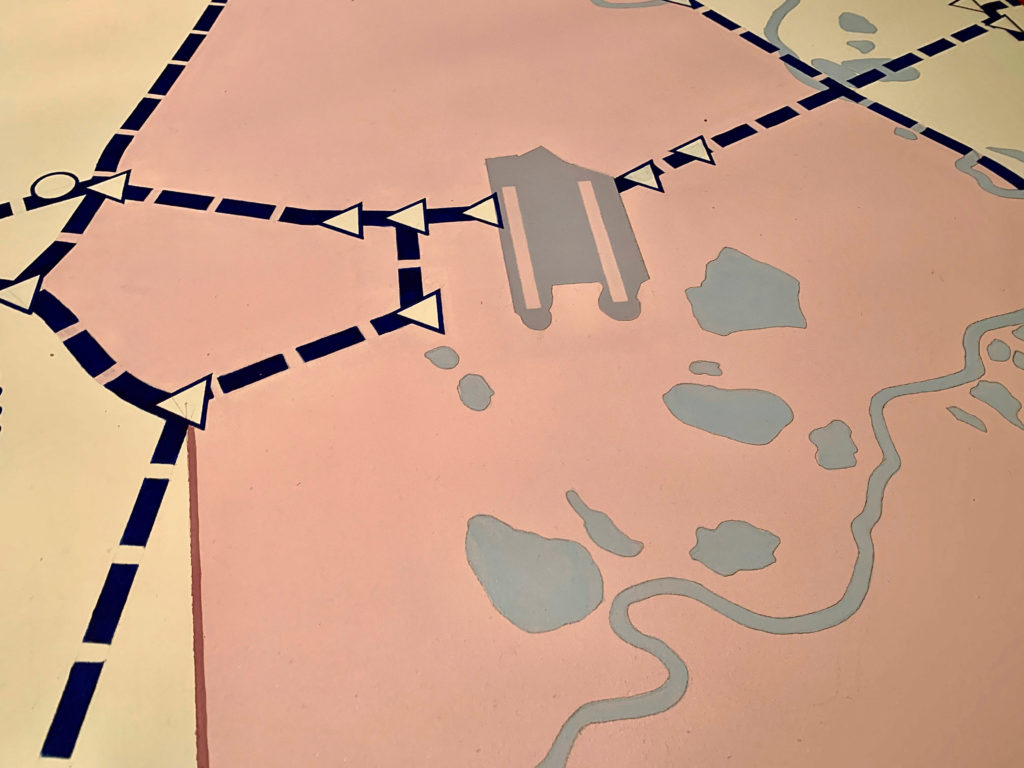

A map nearby, Heathrow (Volumetric Airspace Structures) (2019) by Matthew Flintham, takes the viewer back to west London with a bird’s eye view of the airport complex. Presented on a table that might be used for urban planning, military operation, or board games, it illustrates the topography of the area highlighting a vast infrastructure beneath large sections of controlled airspace, seemingly encroaching on everything else which becomes almost invisible or insignificant.

Navigating the show functions as an exercise of remembrance in many ways, bringing to mind a number of issues that have been at the forefront of public discourse in recent years: from the role of aviation on climate change, to its impact on local communities and ecosystems around airports. And it comes, as if on cue, at a period of heightened environmental concern, propelled most prominently by the Extinction Rebellion movement and climate activist Greta Thunberg, ringing the alarm on the perils of flying.

The controversial Heathrow Airport Expansion also comes through in this context, caught between government plans for future economic growth, and the ongoing resistance from neighbouring residents with campaigns like Stop Heathrow Expansion, No Third Runway Coalition, and Heathrow Association for the Control of Aircraft Noise.

It conjures up conflicting perspectives that unpack a classic dilemma for a society in flux. On one hand, the flight industry is evidently harmful because of its pollution to the planet and the unfair toll on local hosts. Yet, on the other, it is part of a system that facilitates international trade, freedom of movement, and cultural exchanges, each one increasingly more accessible to broader people beyond a privileged few who will always have it. And while it has serious problems that must be addressed, some of which are rightly pointed out here, a world without it entirely is at risk of descent into tribalism and isolationism.

With so much at stake at this particular time and place, the exhibition feels important for its worthwhile attempt in raising these pertinent questions through art, successfully using Heathrow as a case study for matters that undoubtedly have wider implications.

Like the rumble of a plane and many works in this show, the politics of flying will become inescapable as air travel is projected to almost double in size by 2036, despite recent backlash from flight shaming, the rise of staycation, and a spotlight on frequent flyers. The solutions to its unintended consequences are not as straightforward as it might seem, and will likely require a nuanced approach combining systemic changes, paradigm shifts, technological developments, and personal adjustments, all of which cannot come soon enough.

Air Matters: Learning From Heathrow is at Watermans Arts Centre until 5 January 2020. Curated by Nicholas Ferguson in collaboration with Klio Krajewska. Supported by Arts Council England, Forma, London Borough of Hounslow, Kingston School of Art, and Richmond University.

Featured main image: Kate Carr. Image 11. NF. Ascending Composition 1 (For planes). Mixed media, 2019. Included in Air Matters: Learning from Heathrow. 3 October – 5 January 2019.

“Hello, I’m Riz Lateef. Tonight our top story: Instagram travel-star Amber Hinton is missing in Indonesia. Initial reports suggest she has been kidnapped by an ISIS faction operating in the region. We’ll have more on that after the headlines.”

In 2014 Amber Hinton left a lucrative job in finance to follow her ‘dream’ of travelling the world. Like many young women she recognised the potential inherent in her looks; she had an ability to tap into veins of social media, and grasped the appeal for people to ‘follow’ in her footsteps. Educated, professional and dedicated she began by surveying Twitter and Instagram; filtering by hashtags she categorised countries by cultural capital (aka likes, retweets, comments) and then cross referenced with existing coverage. Logic followed that if Thailand was hot right now it might not be hot in a year’s time. Novelty and newness would be essential to getting a foothold in the market.

After months of post-work spread-sheeting, Amber was ready. At a brunch with friends she introduced a mood-board and sales-pitched her new life. I say mood-board, but really I mean a highly aestheticised business strategy. She’d categorised hundreds of travel lifestyle pics and identified core principles of success. With Google Analytics she’d examined the lifespan of a hashtag. She’d reviewed where successful Instagram travellers had been, which countries were oversaturated and which were primed to explode. She’d mapped a route, ensuring a balance between city, beach and country, simultaneously factoring in cost efficiency. She’d prototyped a website and employed a graphic designer to mock up a look and feel for her personal ‘brand identity’. She’d run financial predictions, how long her start-up capital would last, how she expected to turn a profit through funding websites, travel blogging, and eventually as an advertising service for hotels and travel companies.

It was, in short, a stunning piece of work. If Amber had been inclined towards the monastic life of a PhD researcher, she could have turned it into four years paid writing, then subsequently taught her findings at Oxbridge without ever leaving the UK.

With her friends’ enthusiasm and her parents’ consent Amber left for Italy. Between 2014 and 2017 she travelled across the world, first moving in small steps, from Italy to Slovenia, to Bulgaria and Turkey. From Turkey she jumped around the Middle East and North Africa, avoiding conflict zones and skipping countries whose religious codes might frown upon her displayed body. Everywhere she went she befriended new contacts to utilise, chic twenty-somethings who’d invite her to their parents’ villas, rich bankers who’d get her into rooftop parties. Courting the cultural elite was vital; she didn’t have the financial reserves to fund a lavish lifestyle, but she could enter those worlds and achieve an image of effortless glamour.

By the time she reached the Moroccan coast she’d amassed over 75K followers. Enough to be on the radar of international PR girls. Invitations started flying in: five star luxury hotels and exotic adventures. Whilst sipping alcohol-free cocktails and bronzing her skin, she strategised her next move.

She flew to Malta, then across the Atlantic, island-hoping round the Caribbean. In America she visited boutique ranches and hunted down bohemian culture. Down to Mexico, then South America, a perfect blend of high class living and poverty porn. From South America she crossed the Pacific, stopping in at Hawaii on the way, then modern China and finally, in early 2017, Indonesia.

The world first knew something had gone wrong for Ms Hinton was when she posted a unusual message on Twitter. For three days she’d been five star eco-glamping in the rain-forested hills of Lombok, swimming in waterfalls, taking selfies with monkeys and then suddenly:

@amber_abroad

I heard a gun shot! What do I do! HELP HELP HELP

Minutes later a second tweet followed:

@amber_abroad

They said my name, tell me parents I love them

Within minutes a storm of activity was echoing around the Twitter-sphere and #saveamber was the number one trending topic on social media. Facebook campaigns began and Indonesian public officials were receiving flak from latte drinking yuppies in North London. By the second day the Foreign Office had publicly announced that British tourists in Indonesia were advised to leave the country immediately. Typically slow to respond, but then absolutely committed, ISIS announced that Ms Hinton’s abduction had been orchestrated by them, despite it obviously being carried out by a unassociated cell with little to no connection with the upper echelons. For three consecutive days BBC Breakfast News dedicated a half hour to the unfolding crisis; they even flew Naga Munchetty out to Bali to goad tourists into overreactions.

Five days of media fixation were followed by a week of not giving a damn; then out of the blue something very odd began to happen. Instagram accounts operating out of the Indonesian and Philippine ISIS territories started taking on a much more aesthetically sensitive tone. Poorly photoshopped images were replaced with a wave of creative shots. Against verdant jungle foliage, handsome young fighters were pictured topless, sweat glistening on their ripped pecks, rifles casually held over their shoulders. Puppies were photographed wrapped in ISIS flags. Trope travel images, ‘everyone jumping on the beach together’ and ‘girl leading boy’, were bastardised into calls to martyrdom.

At first Amber’s family was relieved; their daughter was alive and communicating with the world. Security services reassured them that eventually she would reveal her position, then they’d be able to plan her rescue. Weeks developed into months and still it seemed Amber was so tightly under the thumb of her captors that she couldn’t encode a message. All they could do was watch her PR strategy unfold.

Back home Theresa May used the crisis to spearhead her personal campaign against social media giants and internet freedoms. “By doing nothing, Instagram encourages ISIS”. In truth they were shutting down hundreds of accounts each day and actively handing data to the NSA and GCHQ.

By the time a video appeared online, ‘Amber’s Top 5 Tips For The Perfect Jihadi Pic’, Theresa had reached her line in the sand. Co-ordinating with the Indonesian President Joko Widodo, Ms Hinton was marked a priority target. If and when they had a lock on her location, an American drone would strike.

The final Instagram post attributed to Ms Hinton was posted on the 25th of June 2017.

For three weeks MI6 had been working in close communication with Indonesian intelligence officials to triangulate her location, scrutinising every post for a telltale clue. Eventually it was a sun umbrella that gave her away; its pattern of red and yellow stripes was attributed to a hotel on a recently occupied island. The post was confirmed as being a Amber original due to her characteristic use of the Juno filter and the Smiling Cat Face With Heart-Eyes emoji.

Amber’s parents were never told the truth about their daughter’s death. Several months afterwards a nice man from the intelligence services told them they believed ISIS had killed her, citing a lack of posts as evidence. Communications were falsified when they demanded proof. They were never shown the photos of her charred scalp, or the one of her left foreleg on the beach; it’d be blown clean clear of the hotel. In the end only a few people, in secret rooms, ever saw the evidence. None of the photos ever made their way online.

The insights of American anarchist ecologist Murray Bookchin, into environmental crisis, hinge on a social conception of ecology that problematises the role of domination in culture. His ideas become increasingly relevant to those working with digital technologies in the post-industrial information age, as big business daily develops new tools and techniques to exploit our sociality across high-speed networks (digital and physical). According to Bookchin our fragile ecological state is bound up with a social pathology. Hierarchical systems and class relationships so thoroughly permeate contemporary human society that the idea of dominating the environment (in order to extract natural resources or to minimise disruption to our daily schedules of work and leisure) seems perfectly natural in spite of the catastrophic consequences for future life on earth (Bookchin 1991). Strategies for economic, technical and social innovation that fixate on establishing ever more efficient and productive systems of control and growth, deployed by fewer, more centralised agents have been shown conclusively to be both unjust and environmentally unsustainable (Jackson 2009). Humanity needs new strategies for social and material renewal and to develop more diverse and lively ecologies of ideas, occupations and values.

In critical media art culture, where artistic and technical cultures intersect, alternative perspectives are emerging in the context of the collapsing natural environment and financial markets; alternatives to those produced (on the one hand) by established ‘high’ art-world markets and institutions and (on the other) the network of ubiquitous user owned devices and corporate social media. The dominating effects of centralised systems are disturbed by more distributed, collaborative forms of creativity. Artists play within and across contemporary networks (digital, social and physical) disrupting business as usual and embedded habits and attitudes of techno-consumerism. Contemporary cultural infrastructures (institutional and technical), their systems and protocols are taken as the materials and context for artistic and social production in the form of critical play, investigation and manipulation.

This essay presents We Won’t Fly for Art, a media art project initiated by artists Marc Garrett and I in April 2009 in which we used online social networks to activate the rhetoric of Gustav Metzger’s earlier protest work Reduce Art Flights (from 2007) in order to reduce art-world-generated carbon emissions... Download full text (pdf- 88Kb) >

Published in PAYING ATTENTION: Towards a Critique of the Attention Economy

Special Issue of CULTURE MACHINE VOL 13 2012 by Patrick Crogan and Samuel Kinsley.