Featured image: Image from Joel Bakan: The Panopticon Power of the new media. Adbusters Jan 2012.

Marc Garrett and Ruth Catlow interview McKenzie Wark ahead of his keynote speech for Transmediale 2015 in Berlin this year.

It’s ten years since McKenzie Wark published his influential book, A Hacker Manifesto. Divided into 17 chapters, each offers a series of short, numbered paragraphs that mimic the epigrammatic style of Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle. Wark then published, amongst others, a series of critically engaging books such as Gamer Theory and the Spectacle of Disintegration. Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett from Furtherfield ask Wark how things have changed since these publications, focusing on how our everyday lives have been infiltrated by competitive game-like mechanisms that he described more than a decade ago.

Furtherfield: You published the experimental writing project Gamer Theory first as a book in 2006 and then in 2007 with a specially revised 2.0 version online.

Mckenzie Wark: Yes, although I think the network book version is mostly broken now. Good thing there’s a dead-tree format back-up!

F: In it you argue that we’re living in a world that is increasingly game-like and competitive. Also that computer games develop a utopian version of the world that realizes the principles of the level playing field and reward based on merit; whereas in the world, this is promised, but rarely realized.

MW: Yes, I think one way of thinking about certain games is that they are a fully realized neo-liberal utopia, which actually gives them some critical leverage of everyday life, which is a sort of less-real, only partially realized version of this, where the playing field is not level, where the 1% get to ‘cheat’ and get away with it.

F: You also talk of the “enclosure of the world” within the “gamespace” where the logics of the game are applied as the general patterns of organization in the world. And this happens as we adapt to the allegorical forms of contemporary games media.

How do you think this situation has changed since you wrote Gamer Theory?

MW: Well, to me it looks like the tendency analyzed in Gamer Theory became even more the case. GamerGate looks among other things like a reactive movement among people who really want the neoliberal utopia in all its actual neofascist and misogynist glory to not be exposed as different to everyday life. When women gamers or game journalists stick their hands up and say, “hey, wait a minute”1, they just want to mow them down with their pixelated weapons. So the paradox is that as gamespace becomes more and more ubiquitous, the tension between promise and execution becomes ever more obvious.

F: Do you see the term Gamification that many theorists use currently as an elaboration of the ideas you developed in Gamer Theory? Or are there significant new ideas being explored?

MW: Ha! Well no, gamification was about celebrating the becoming game-like of everyday life. So I always saw that as a kind of regression from thinking about the phenomena to sort of cheerleading for it.

F: The software developer and software freedom activist Richard Stallman, when visiting Korea in June 2000 illustrated the meaning of the word ‘Hacker’ in a fun way. During a lunch with GNU fans a waitress placed 6 chopsticks in front of him. Of course he knew they were meant for three people but he found it amusing to find another way to use them. Stallman managed to use three in his right hand and then successfully pick up a piece of food placing it into in his mouth. Stallman’s story is a playful illustration of “hack value,” about changing the purpose of something and making it do something different to what it was originally designed to do, or changing the default.2

Stallman was highlighting fun and the mischievous imagination as part of the spirit of what he sees as hack value.

Where do you see lies the hack value in games culture? What has happened to the fun in games? Who’s having it and where is it happening?

MW: Stallman is one of the greats. Sometimes, people have this experience of scientific or technical culture as one of free collaboration, where there’s a real play of rivalry and recognition but based on producing and sharing knowledge as a kind of gift. JD Bernal had that experience in physics in the 30s and Stallman had, I think, a similar experience in computing. I think it’s important for those of us from the arts or humanities to honor that utopian and activist impulse coming out of more technical fields.

There’s a lively, critical and even avant-garde movement in games right now. That’s part of why it has provoked such a fierce reaction from a certain conservative corner. The culture wars are being fought out via games, which is as it should be, as it’s one of the dominant media forms of our times. So there’s certainly some sophisticated fun to be had alongside the more visceral pleasure of clearing levels.

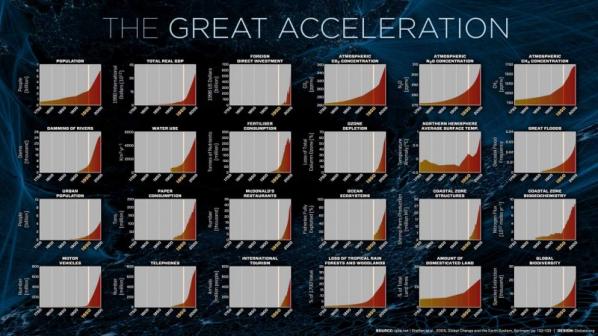

F: “Our species’ whole recorded history has taken place in the geological period called the Holocene – the brief interval stretching back 10,000 years. But our collective actions have brought us into uncharted territory. A growing number of scientists think we’ve entered a new geological epoch.”3 And, this new geological epoch has been proposed as – the Anthropocene.

In your essay ‘Critical Theory After the Anthropocene’4 you say “At a minimum, the Anthropocene calls on critical theory to entirely rethink its received ideas, its habituated traditions, its claims to authority. It needs to look back in its own archive for more useful critical tools.”

What are these ‘useful critical tools’ and how might theorists, new media artists, game designers and society at large put these to work?

MW: The ‘cene’ part of Anthropocene (from the Greek kainos) means a qualitative break in time. If time is in a sense always different, then kainos is the differently-different – a new kind of time. Those like Paul Crutzen who have advocated the use of the term Anthropocene to designate a new geological time have issued a major challenge as to how to interpret such a possibility. I leave it to the scientists to figure out if such a claim is scientifically valid. As someone trained in the humanities, I think the generous, comradely, cooperative thing to do is to try to interpret what our friends and colleagues in the sciences are telling us about the times. So in Molecular Red that was what I set out to do. Let’s take seriously the claim that these times are not ‘like’ other times. That I think calls for a rethinking of what from the cultural past might be useful now. I think we need new ancestors. Which is why, in Molecular Red, I went looking for them, based on the question: to which past comrades would the Anthropocene come as no surprise? I think Alexander Bogdanov, who understood a bit about the biosphere and the carbon cycle, would not be surprised. I think Andrey Platonov, who wrote about the attempts and failures to build a new kind of infrastructure for the Soviet experiment in a new mode of production would not be surprised. There are others, but those I thought were particularly helpful, not least because their Marxism remained in dialog with the sciences and technical arts. I don’t think the more romantic anti-science side of Western Marxism and continental thought is all that helpful at the moment, not least because it rules out of court exactly the kinds of scientific knowledges through which we know about the Anthropocene in the first place. The anti-science critique has been captured by the right, so we need new tactics.

F: Who’d be empowered by an encounter with your ideas and where do you see the potential for agency in the current economic and environmental contexts?

MW: Not for me to say really. Writers are usually the last people to have any clues as to what their writing says. There’s a sort of idiot quality to banging away on a keyboard. We’re word processors. Its always surprising to me the range of people who find something in what I write.

My hunch is that the future is in the hands of an alliance between those who make the forms and those who make the content: a hacker and worker alliance. It is clear that this civilization has already become unreal. Everyone knows it. We have to experiment now with what new forms might be.

F: And, where in the world do you see examples of individuals, groups and organizations, and or companies – who are putting into action some of the critical questions that you’re exploring in your writing?

MW: Besides Furtherfield? I never like to give examples. Everyone should be their own example. To détourn an old slogan of the 60s: be impossible, do the realistic!

F: In your later essay ‘The Drone of Minerva’5 you continue to write about the Anthropocene. But, you also bring to the table the subject of the Proletkult.6 The Proletkult aspired to radically modify existing artistic forms of revolutionary working class aesthetic which drew its inspiration from the construction of modern industrial society in Russia. At its peak in 1920, Proletkult had 84,000 members actively enrolled in about 300 local studios, clubs, and factory groups, with an additional 500,000 members participating in its activities on a more casual basis.

You are writing about the Proletkult in your latest book. Could you tell us a little something about this and how it will connect to contemporary lives?

MW: Proletkult was influential in Britain too, during the syndicalist phase of the British labor movement, up until the defeat of the 1926 general strike. After that the dominant forms were, on the one hand, the ethical-socialism and parliamentary path of the Labour Party, or the revolutionary Leninist party. Well, those paths have been defeated now too. I think we have to look at all of the past successes and failures all over again and cobble together new organizational and cultural forms, including a 21st century Proletkult.7 What that might mean is trying to self-organize in a comradely way to try and gain some collective charge of our everyday lives. It does not mean just celebrating actually existing working class cultures. Rather it’s more about starting there and developing culture and organization not as something reactive and marginalized but as something with organizational consistency and breadth. Since the ruling class clearly doesn’t give a fuck about us, let’s take charge of our own lives – together.

Thank you McKenzie Wark – Ruth Catlow & Marc Garrett 😉

Ruth Catlow will be at Transmediale 2015 CAPTURE ALL, moderating the keynote Capture All_Play with McKenzie Wark, on Sat, 31 Jan at 18:00.

Ruth is also participating in two other events, Play as a Commons: Practical Utopias & P2P Futures and The Post-Digital Review: Cultural Commons – http://www.transmediale.de/content/ruth-catlow