Anonymous, untitled, dimensions variable is the title of a show by 0100101110101101.ORG (Eva and Franco Mattes) at Carroll/Fletcher gallery in London from 13th April to 18th May 2012. Or at least it was. The title changes each day based on submissions to a blog (http://exhibitiontitlechange.tumblr.com/). The new titles have been printed out and displayed on the wall to the left as you walk in to the gallery.

You don’t expect this kind of playful intersection of the virtual and the real in a gallery off of Oxford Street, across from Soho, opposite other new galleries. Carroll/Fletcher’s glass-fronted welcomingly brutalist interior says “serious contemporary art space”. Inhabiting such a space presents a challenge to net and digital art that must be met with careful presentation and considered curation.

Through the glass front of the gallery, and as you enter, you see a sculpture or assemblage of a (stuffed) cat trapped in a birdcage by a (stuffed) canary (Catt, 2010). The cat has suffered Epic Fail as the Internet would say, and did in the meme image that the sculpture is based on. It’s a comic and unnerving object even without the extra layers of reference provided by the original meme and the knowledge that it was originally presented as a fake Maurizo Cattelan sculpture. It is art with its roots in the net that can stand on its own without that context. Its companion piece, Rot, 2011, is a fake Dieter Roth sculpture consisting of detritus in a glass jar on a plinth against the far wall. 0100101110101101.ORG briefly inserted it into the Wikipedia page on Roth, and the fact that its materials were all ordered via the Internet drives home just how commonplace this has become.

Both are given the room they need to work as objects in a gallery. Neither originates in itself as net art, more in 0100101110101101.ORG’s history of tricksterism and transgression. These are concerns that are easily linked to net culture, possibly too easily on the part of the reviewer, but it is telling that they are the works that the show opens with. They physically establish the playful appropriation and hyperreality that is the basis of much of 0100101110101101.ORG’s work.

Pride of place in the first room of the gallery goes to the projection The Others, 2011, 10,000 digital photographs (supposedly) copied without authorization from the folders of computers used by people on a peer-to-peer filesharing network that 0100101110101101.ORG used to distribute their own work. These are private images, projected at an angle and slightly across the corner. Configure your peer-to-peer filesharing client wrongly and it shares all the files in the folder you share. Including the images of you naked, drunk, lonely, partying, or whatever else you wouldn’t post anywhere a future employer might find them.

In the next, smaller, room is Colorless, odorless and tasteless, 2011. It is an old-fashioned car racing video arcade game retro-fitted with a petrol engine that starts up when you insert a coin and revs as you press the pedal to accelerate the virtual car on the screen, filling the (sealed…) room with carbon monoxide. Combining the virtual made physical of Catt and the moral impact of The Others, it is the most immediately dangerous artwork I’ve ever had to review.

Moving into the larger room at the back of the ground floor of the gallery, the video No Fun, 2010, is the most shocking piece in the show. Franco Mattes pretending to hang hineself on the random Internet webcam video chat switchboard Chatroulette is one thing, but the reactions of other Chatroulette users as they connect and see him apparently hanging there is quite another. Some laugh, some jeer, only one I watched displayed any lasting concern. This is the moral and aesthetic flipside of The Others.

Reenactments, 2007, is my aesthetic and technical favourite piece in the show. Videos of canonical performance art pieces being re-enacted by Eva and Franco’s Second Life avatars are displayed on CRT monitors arranged at floor level surrounded by the cables and adapters used to play back the video from SD cards. It’s much easier for an avatar to remain still as a “Singing Sculpture” than it is for a human being, making it even stranger, and Marina Abramovic’s “Imponderabilia” works much better with impossibly buff avatars than with mere naked human models stood in a doorway. It exquisitely foregrounds the social mediation of Second Life and its players self-presentation. A large cartoon wolf squeezes through between the naked avatars, their polygons intersecting. A vampire attempts to fly over them but hits the bounds of the architecture. The crowd in the background chat and bide their time. The virtual intensifies the real, out-doing and critiquing its appropriated source material.

Stolen Pieces, (1995, made public 2010) claims to move beyond fakery and unauthorized copying to physical appropriation. Stolen physical fragments of canonical postmodern artworks (Duchamp, Warhol, Koons, Rauschenberg) are displayed like forensic evidence, protected in small plexiglass containers, accompanied by large photographs of them and by documentary evidence of their theft. There’s no statute of limitation on theft in the UK, and damaging artworks shouldn’t be applauded. But it’s a daring performance and a concrete critique of the fetishism that lies at the heart of the art market and the institutions that help drive its value.

Following the brutalist concrete staircase to the basement reveals My Generation, 2010, a smashed but still working early-2000s PC lying on the floor. On its monitor, that appears to have fallen on its side, show video clips of computer game players giving in to and venting their frustration at the games they play. This isn’t the kind of image of yourself you want as your lasting monument on the Internet. Gathered together, like the images in The Others and the videos in No Fun, they again form a summation of an aspect of society and our visual environment that could not be achieved with such immediacy by other means. And the clear space and architectural solidity of the gallery again help to put a different emphasis on the material than if it was encountered on the web.

The wall-filling video projection of Freedom, 2011, records Eva’s attempts to plead with the players of networked First Person Shooter computer games not to kill her character. Touch-typing might have helped, but even when Eva manages to type long enough to explain that she’s an artist, or to ask people not to shoot, the social and game logic of the virtual world mean that her character is executed again and again, the screen shifting to third person as her avatar moves out of her control in death. Like No Fun, there is a core of callousness to these Internet interactions, and like My Generation they are unexpectedly preserved and presented for contemplation.

The final piece in the show is the documentary Let them believe, 2010, a video record of 0100101110101101.ORG’s Tarkovsky-haunted journey into Chernobyl’s “Exclusion Zone” in order to recover part of a fairground ride to turn into Plan C, 2010. Bringing part of the ride to life in a place where people can enjoy it is an effective and resonant symbolic resolution of the kind that art more than any other mode of human endeavor can provide.

0100101110101101.ORG’s work presented physically has more than enough presence to fill the gallery and benefits from the space and the considered curation afforded it here. Some of the work is more physical than virtual and vice versa, sometimes the ethics of the work place 0100101110101101.ORG as the villain sometimes as the victim, and sometimes the work is performance whereas other times it is assemblage. I mention this to point out both the strong themes to the work and how individual the effect of each piece is.

Net art in the gallery might seem a category error, like museum postal art. Or it might seem a commodity, like auctions of land art documentation. But net art is transitioning from being the contact language of artworld emigrants learning the net’s protocols to the contact language of net emigrants learning artworld protocols. 0100101110101101.ORG have made art of these encounters from the start, and have always been as at home in the gallery as on the net.

The text of this review is licenced under the Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 Licence.

Marc Garrett: You are an artist who works solo and with others in various ways. A large body of your work consists of performances, interventions and sound recordings. I want to begin this interview by asking, why you decided to form ‘The NeoFuturist Collective‘, and what was the main mission or purpose behind such a collective?

Joseph Young: The NeoFuturist Collective was born as a convenient way to house a piece of work I was making called ReAwakening of a City. The idea had started as part of a practice-based PhD at SMARTlab UEL, but as soon I got funding for the project from the Arts Council, I realised I didn’t want to spend the next four years writing about it…

I invited a group of artists to join me in making a collaborative piece of work from a seemingly simple premise – the transformation of urban noise, inspired by futurist artist Luigi Russolo’s Art of Noises manifesto. Russolo had created a series of “noise networks” or symphonies for his mechanical intonarumori (noise makers) back in 1914, and in so doing he had influenced the entire course of 20th century music.

Despite his contemporary resonance, little is generally known about Russolo’s work, as all of his instruments were destroyed in the intervening two world wars. Of the scores he wrote, only the first 7 bars remain of Awakening of a City, and that only because it was reprinted in the art magazine Lacerba. Apart from the fragment of written score there are letters, reviews, photographs and other forms of documentation which have led researchers and artists over the years to try and recreate his noise making instruments.

Our project is rather different – we use the remaining 7 bars as the starting point for a new piece of work, ReAwakening of a City, engaging with all forms of visual and aural urban noise that we spend so much time trying to block out. Traffic noise, junk emails, health and safety warnings, advertising and street furniture. The form is performative, visual and mediated as well as musical, using all available means at the disposal of the 21st century artist.

By engaging with my artist-collaborators’ practices, I commission work that responds to this central idea and then set up an appropriate curatorial context for extending that individual response into a collective noise network.

MG: Where did these ReAwakening of a City events happen, and what kind of response did you receive when these performance, interventions took place? How important was it to connect with others – every day people, whilst engaging in the process of expressing these real-life experiments?

JY: The first ReAwakening took place in Brighton in Feb 2008. We started off the project by declaiming the NeoFuturist manifesto (written by Rowena Easton) in Jubilee Square, with a bunch of workmen and their drills providing a fabulously appropriate accompaniment to the text which celebrates Urban NOISE. (The manifesto can be downloaded from www.neofuturist.org). The crowd then followed us onto the Arts Council offices where we laid a wreath on their steps in support of all the companies that had been recently cut – we were ourselves in receipt of Arts Council funding at the time. A classic case of biting the hand that feeds you. Our activities provoked mild amusement and little controversy however, as the good citizens of Brighton & Hove are used to seeing “crazy” artists peddle their wares in public.

A couple of months later we had our first performances of work-in-progress at The Basement, Brighton. The reaction here was far more hostile and interesting, with some audience members questioning our politics in the Q&A session afterwards, accusing us of proto- fascism. Actually the level of debate was thrilling, as we really touched people’s buttons and ended in a deep discussion about the impact of the Futurists and their relevance to the current political climate. This question surfaced again a few of months later in an online interview with The Thing Is… magazine.

We were fortunate after that to be invited to make a piece of work on Wall Street in New York for the psychogeographic festival, Conflux. Our proposal was to make a walking performance that explored the everyday experience of living and working in the Wall Street district and how this might inform our understanding of the impact that this small area of real estate has on the rest of the planet. We arrived on September 11th 2008 to be met by 9/11 conspiracy theorists on street corners, and proceeded to spend several days mapping the area through sound recordings, text and video in preparation for a dawn performance on 14th September – a ReAwakening as the city awakes. The effect was dramatic and unexpected, as my declaration of the NeoFuturist manifesto outside 1 Wall Street brought about the collapse of Lehmann Brothers that weekend and the subsequent domino effect on the global economic system. Sorry world!

Our next major intervention was more low key, but no less dramatic as we were commissioned by Fuse Medway festival to engage with and inspire the village community of Upnor. Our mission was to get the people to take to the streets in a protest/celebration march. We worked with the community over a number of months, holding public workshops and meetings, networking furiously in the local pub (one of four!) and it soon became clear that the general apathy towards the arts, and outsiders in general, meant that if the public were not going to come to us, then we would have to go to them. So we took to the streets and made work in public which enraged some, who questioned where our funding had come from, but delighted others and built a momentum towards our final performance.

A Call to Arms (as the piece was finally called) took place in June last year and was a very successful example, I think, of how one can make “community art” challenging as well as accessible. See http://neofuturist.blogspot.com for full documentation and a film of the performance.

Other pieces of work, include shouting at the Futurist paintings with a megaphone, as part of the Tate Modern Futurist retrospective last summer. An experience as liberating as it was faithful to the original spirit of futurism, causing equal anger and delight amongst an unsuspecting public. I was also invited as a panellist to take part in a public debate along with other luminaries from the art world, on the subject of “Is the Avant Garde Passe?” organised by The Institute of Ideas in London. Here the public paid to witness a lively and informed panel discussion around the relevance of contemporary art, proving, it seems to me, that there is a real appetite for intelligent, politically driven commentary and debate.

A group of artists drawn from the fields of visual, performance, video and sound art will attempt to transform the everyday language of urban sounds and visual junk (such as spam emails and billboard advertising) into a true multi-media experience to do just that; asking us to question our assumptions about what is beautiful in a modern world of information overload.

MG: Your comments that contemporary art is in need of intelligent, politically driven commentary and debate rings true. In respect of my own art context(s). Thinking of the many amazing self-organised, networked communities, of which there are many, on-line and in physical space; there has been a massive shift of art creating, moving independently, yet in parallel to the ‘official’ and hegemonic examples accepted or considered contemporary at the moment. Of course, if we think about what contemporary means itself, it means existing, occurring, or living at the same time. The relationship between institutions and art which is actively critical and more challenging than easier processed art such as Brit Art, how they represent contemporary art.

Considering the history and knowledge we have regarding the original Futurist movement, and its close connections with fascism. For instance, what is less known is that, the Futurist movement did not only consist of fascists, but within it there were also socialists, anarchists, leftist and anti-Fascist supporters. Consisting of interesting individuals such as Georges Sorel, who explored his own views and intellectual thinking, right across the political spectrum. Georges Sorel “…was a voluntarist Marxism: he rejected those Marxists who believed in inevitable and evolutionary change, emphasising instead the importance of will and preferring direct action. These approaches included general strikes, boycotts, and constant disruption of capitalism with the goal being to achieve worker control over the means of production.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Sorel

I can see a direct link from Sorel’s activist approach and The NeoFuturist Collective’s ReAwakening events and performances. Of course, there are some other pretty good contemporary art activists out there at the moment, who also incorporate performance as part of their creative process; such as ‘The Office of Community Sousveillance’. “This work rests between legality and illegality. By posing as security officers, ‘PCSO Watch’ imaginatively play at the borders of what is typically deemed right and wrong, real and unreal, pushing their expression in the form of political enactments and direct action. This is a paradigm shift, not particularly interested in the art critic’s perspective.” http://www.furtherfield.org/displayreview.php?review_id=338

“Futurism has produced several reactions, including the literary genre of cyberpunk — in which technology was often treated with a critical eye — whilst artists who came to prominence during the first flush of the Internet, such as Stelarc and Mariko Mori, produce work which comments on futurist ideals.” The legacy of Futurism. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futurism#The_legacy_of_Futurism

With the understanding that there have been various influences, mutations and re-appropriations from the Fururist movement, I am wondering what elements you feel or think are still important to reclaim, reshape and reintroduce into a contemporary world, both in respect of the art arena and in relation to our everyday environments?

JY: What interests me in relation to the Milan Futurists is, first of all, the misperception, as you have pointed out, that futurism was primarily a fascist movement. My understanding is that Marinetti was the only artist to have that association, having been invited to serve on the Central Fascist Party Council after the First World War. He resigned not long after as soon as the Catholic Church was also invited to sit on the Council – Marinetti being an avowed atheist. This is not to excuse the entire movement of this problematic association, but it does put it in context. It also recognises that a spirit of optimism and a belief in technological solutions to the world’s problems, that futurism embodied, also has its’ darker side. And it is with this knowledge that I choose to engage with (neo)futurist ideas in the 21st century, as it seems to me, that in a world seemingly on the verge of collapse, that a spirit of positivity renewal is both urgent and necessary, and also the ultimate political gesture.

You mention various artist collectives that have appropriated the futurist legacy in this way, and to that I would add Ultra-Red who, incidentally, published a short sound piece of mine, recorded on Wall Street during the crash of 2008, as part of Fifteen Sounds of the War on the Poor vol.3.

In order to engage with the state of the planet, artists can no longer cling to romantic, utopian notions of nature/beauty in opposition to man/technology. This dichotomy seems to represent more about human self-loathing than it does about a workable solution to global warming/terrorism/the energy crisis/reform of global capitalism, etc. Moreover it leads us towards a new “medievalism” (ban air travel, ban cars, buy local) that is all too prevalent in ecological pressure groups. In this argument, man has brought us to the edge of destruction, therefore we must drastically scale back all of our wealth-producing activities. As if the (post)modern world could be wished away in either Luddite vision of the future or more worryingly in the ideology of The Zeitgeist Movement, whose apocalyptic vision of a radical eco-future involves tearing down our cities and rebuilding them.

This thinking is also represented in the work of acoustic ecologist and renowned nature recordist, Bernie Krause in his article, Anatomy of the Soundscape: New Perspectives, Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, Jan/Feb 2008 Vol. 56 Number 1/2, Pg 73-80 (2008), in which he dissects the soundscape (a term first coined by R Murray Schafer in Soundscape: The Tuning of the World) into 3 separate strata:

“GEOPHONY is framed as natural sounds emanating from non-biological sources in a given habitat.acoustic variations. BIOPHONY By far the most complex and laden with information, this unique feature of the soundscape is comprised of all of the biological sources of sound from microscopic to megafauna that transpire over time within a particular territory. ANTHROPHONY, defined as all of the human-generated sounds that occur in a given environment: physiological (talking, grunting, body sounds), electromechanical, controlled sound (music, theatre, etc.), and inci- dental (walking, clothes rustling, etc.).”

In this breathtaking philosophical leap, Krause removes the human from the natural environment and pits him/her in opposition to it. In creating a separate category for human sound activities outside of the biophony (i.e. the sounds of all other species on the planet), he is both over-stating human control and dominance over the environment and also denying us a role in the Gaia hypothesis – one of the green movement’s central texts, that views the Earth (and all of its inhabitants) as a single organism.

I am certainly not refuting or seeking to contradict many of the arguments regarding human sound activities and stress levels, posited by the World Soundscape Project, of which Krause is a prominent member, but it is worrying that so many eco-activists see humanity as a problem and not as a solution. And this is where Futurism and its antecedents/mutations can offer a way forward…

If, as I believe, we can find beauty within the drone (our drone), then the clamour of urban noise, both visual and aural, can be transformed in our perceptions into something of interest and value, rather a thing to be blocked out or ignored. If we can stand in a busy place such as Oxford Circus in the centre of London and open our ears to the sonic detail that is contained within the omnipresent drone of human activity, then we can begin to understand that activity as a creative as well as a destructive force. We can then harness and use this energy to power and revitalise the human spirit.

So, for me, the Art of Noises manifesto is the central and critical text in beginning to shape a new understanding of the contemporary sound and land-scape. If we can find a way of reframing urban noise as a meditative experience, as I recently did in my residency with Blast Theory, then we are part of the way to ReAwakening our cities as places of hope and optimism. To do this, I made a number of immersive binaural recordings of the area around 20 Wellington Road, where Blast Theory are based on the industrial outskirts of Brighton, and mediated these as iPod listening experiences in a temporary installation space that I set up for the event. When I came to retrieve participants from the room (they went in 4 at a time) they had invariably made themselves comfortable and been totally immersed in the sounds of the local traffic. They often described their experiences as “relaxing” and “enjoyable”, and how many times can you say that of the experience of standing beside a busy, urban, traffic-filled road?

So that is my mission for ReAwakening of a City; to take Russolo’s lead from the surviving 7 bars of his score to Awakening of a City (1914) and reframe and rework the paradigm of the celebration of urban noise to (re)awaken of all of the senses through a heightened perceptual shift in one of them – that of hearing; the neglected sensory cousin in our predominately visual culture. My ultimate ambition being to create a large-scale performance event for the 100th anniversary celebrations in 2014, in collaboration with like-minded artists from around the globe.

Featured image: F.A.T. Lab (Free Art and Technology Lab) were found causing trouble at the Transmediale.10 this year.

An interesting outsider project at Transmediale.10 this year, was F.A.T. Lab (Free Art and Technology Lab). A collective of artists, engineers, scientists, lawyers, musicians and trouble-makers who have been working together for two years, on the intersections of Pop culture and Open source. Their stapline describes them as “An organization who is dedicated to enriching the public domain through the research and development of creative technologies and media”. Beware, they love using the word ‘Fuck’. A lot! Which means they are cool, and some you grown ups may feel slightly unnerved by their over generous outpouring of flippant explitives, but the kids out there just love it!

You can read an explanation of their work in the about section on their website, and view a video presenting some of their ideas and works. With a simple rap base with nasty yellow and pink colors, it could be considered as a joke. Perhaps, to some degree it is, but at another level they are playing around with social contexts of the Internet culture’s, presumptions and acceptance of things. Through an omnipresent ludic approach they reuse what is given to us all with a contemporary pop attitude – showing us the many contradictions from these given systems. Proposing other possibilities in order to loosen and to free things up from the copyright laws and prescribed rules of both big companies and clumsy governments.

One of their projects called Public Domain Donor, consists of D.I.Y stickers saying “In the event of death please donate all intellectual property to the public domain”. They write “Why let all of your ideas die with you? Current Copyright law prevents anyone from building upon your creativity for 70 years after your death. Live on in collaboration with others. Make an intellectual property donation. By donating your IP into the public domain you will “promote the progress of science and useful arts” (U.S. Constitution). Ensure that your creativity will live on after you are gone, make a donation today.”Simple and humurous.

Yet, behind their process of cultural detournment exists a reference to earlier net art critique, by Critical Art Ensemble who way back in 1995 said “Each one of us has files that rest at the state’s fingertips. Education files, medical files, employment files, financial files, communication files, travel files, and for some, criminal files. Each strand in the trajectory of each person’s life is recorded and maintained. The total collection of records on an individual is his or her data body -a state-and-corporate-controlled doppelganger. What is most unfortunate about this development is that the data body not only claims to have ontological privilege, but actually has it. What your data body says about you is more real than what you say about yourself. The data body is the body by which you are judged in society, and the body which dictates your status in the world. What we are witnessing at this point in time is the triumph of representation over being. The electronic file has conquered self-aware consciousness.” The Mythology of Terrorism on the Net. Critical Art Ensemble Summer, 95

Also as stimulating, is the idea Graffiti Markup Language, an XML file type specifically designed for archiving graffiti tags, and easily reproducing them.

For Transmediale.10 they presented a project called Fuck google, one of their more involved works, appropriating the image of Haus der Kultur der Welt, the futuristic bulding hosting Transmediale, formerly known as the Kongresshalle conference hall, a gift from the United States, designed in 1957 by the American architect Hugh Stubbins Jr. as a part of the Interbau exhibition. John F. Kennedy spoke there during his June 1963 visit to West Berlin. Fuckgoogle focuses on reminding us all how this big company has become omnipresent in our digital lives, refering to the risk that too much data is owned and is going to be owned more and more, just by Google alone. It exists as a collection of browser add-ons, open source software, theoretical musings and direct actions.

Not necessarily trying to be a definitive solution against the big G in any sense of the word, but more a reminder, a provocative virus to diffuse. So we have a graffiti firefox skin, fuck google pins, The F.A.T Pad or some plugins to reclaim your public individual space on your browser. Everything is D.I.Y and opensource, so you can easily replicate it. The approach can be find with FuckFlickr a free image gallery script offering everyone who visits a Flicker-like image gallery.

The F.A.T. Lab is an example of technological sabotage. Of course, it’s not a new thing in respect of the hacker community: using the instrument, medium directly, in order to change perceived assumptions of our reality. What is quite new is F.A.T. Lab’s blatant exploitation of everyday Pop culture and its language. The hacker counterculture has always had it’s own way of communication, built in the late 80’s and 90’s. These days, more and more people use the computer, not just hackers. Using Pop culture in order to communicate one’s message could be one possible way to escape the duality culture/counterculture. On the other hand, F.A.T. Lab could be creating a fresh paradigm which allows others who would not normally appreciate hacker culture or even media art culture, filling a space beyond art culture which could be considered as too refined.

Marcello & Gaia: Can you describe who you are and how do you connect each other?

Evan Roth from F.A.T. Lab: We are a group of friends. There’s not any formal application process or open call, many come from typical art organizations. It started out as a group of friends and then slowly, more friends joined. We also made more friends, collaborators on line. Here at Transmediale.10, it’s actually our first chance to meet face to face and some of us have not met before. There are two things that mainly characterize us. On one side, there is the open source culture and advertisement free culture, but also the idea that this all should be fun. Art and political activism doesn’t have to be a boring, the interface of it all, can be accessible to more people. We try to push this candy coding, get the those audiences who are using youtube videos, that is our primary audience. We like it when art organizations pay attention to us but really our main audience is at the borders of things, using different networks, commercial networks out there, happening outside of the gallery.

M&G: If we look at the projects you are showing here there is a kind of aesthetic in common, the colours are really interesting, the pink and the yellow remind us early 90’s spam. Is that aesthetic a primary decision, is the style you choose to define you, or has it just happened in the progress of your work.

E: I answer that in two. There is a thing from open source development culture that is ‘release early and release often’, we try to apply this model to the media production. We try to release ‘early and often’. If you are on the fence where you should release something or not and it is not quite ready, just push out the door, because it is better to have it in the public counter system than not. So the aesthetic of the website is in part probably pushing out the door rather taking care of the nuances or the color it is. We just try to get this thing published quickly. Someone could be sitting on their brilliant idea and waiting for years to release, waiting for some details and then you find that no one really cares about this in the end. But there is also an aesthetic interest in common, that comes from this ‘dirty style’. There is an artist friend, Cory Arcangel who is one of my favorites, and he describes the dirty style as ‘either you take little interest in design so it becomes so un-aesthetic or you over-work it to a point that the work itself becomes something too trivial’. We don’t have meetings about how the website is going or what it looks like.

M&G: Don’t you think that this “dirty style” is somehow hiding the real content or the message? The use of ‘dirty style’ is obviously an answer of the hyper sensibilization, concern of the form but at the same time this makes your work splitting in between the no-attention of form and pushes content in the corner.

E: The way our websites look matter’s less and less now, because people don’t go to websites for content anymore. Most of the traffic in the websites do not even see the pink and the yellow, design. There is some kind of form/function relationship going on. We are interested in rolling up this web 2.0 idea a little bit, and that’s what this installation here is about at Transmediale. The early 90’s aesthetic was with people hand coding html and making tables, not downloading a WordPress thing. In that sense, there is a sort of connection to the DIY, rolling back to the way of 1.0 – where the files are hosted in your own server and not google or yahoo.

M&G: Isn’t it more interesting to try and critique in a more constructive way, creating something else, not just another google appropriation but other kind of net platform for a community? Could that be one of the important challenges for artists now?

E: Open source is a big movement and free culture is even bigger and so we know that there are people out there hacking in this way right now, but we are not programmers, there are programmers taking part but these are not our skills. Our place in this movement is in the media side. We do have programmers in our group but we feel more like media makers. We make these videos and they are kind of funny and taking something from the pop/culture, twisting them, possibly people have a look and pass them around. But there are messages in them. And the messages are trying to reveal the money and the branding business that google is making and saying it is not cool, and being involved in an alternative open source culture looks better. We also have a development tool like fuck flicker and flv player where you can have your own videos up like you tube.

M&G: Why are you are supposed to win this year’s Transmediale? You stood up on the stage during the award claiming the award for yourselves!

E: Oh no, we don’t think we are supposed to win. Do you know Kanye West? This is a USA story, we joked about Kanye a little bit. We’re always trying to pay attention to what is going on in pop culture and surf a little bit. Kanye was notorious for interrupting a ceremony whenever he lost, grabbing the mic. As we were for this fuck google project – last night, the winner was a youtube related project, and google is a sponsor. The message we tried to get across last night, was a reference to this, and we are gonna have an official press release on it soon. But I think that for Transmediale, our project was an anomolie, showing this fuckgoogle in contrast to accepting web 2.0, which is actually a range of projects. We were surprised to be invited, who know’s what for? But we think that it was a very wise decision, and we are really happy to be here.

On their website you can get a clear impression of their feelings towards Google “So, what is so “fuck-worthy†about Mother-google? It is the fact that a corporate entity, even one as beloved and competent as Google, is in control of such a large stake in the digital network and public utility upon which we have all grown so reliant. And, that as a publicly traded company, it doesn’t have to answer to anyone but its largest shareholders, despite the fact that its decisions effect the lives and private information of millions of people. Few even question or raise a voice in opposition to the Google-ification of the Internet.”

There were more than 1,500 submissions for the Transmediale.10 awards, nine art projects were nominated and F.A.T. Lab was a runner up amongst them. Showing contemporary, activist art within a larger more incorporated festival is to be commended, it is not an easy thing to do. And we all know how easy it is to criticize rather than make something ‘real’ and positive happen. F.A.T. Lab are a tangible byproduct of a culture, caught in the trappiings of Hyperreal situations, a confused world losing itself even further into a perpetual state of denial. Pop culture and celebrity related banalities are constantly distracting our gaze. It is an interface which can only handle life via mediated proxy. F.A.T. Lab know’s this, and have adapted themselves to literally scrap with it on their own terms. Their role and place in the world is to get out there on the front line and go places where the common people reside. They want to be on the main stage battling it out, whilst challenging the interface presented to us all – making it their playground.

You can also read Marcello Lussana and Gaia Novati’s article about this year’s Transmediale.10 here…

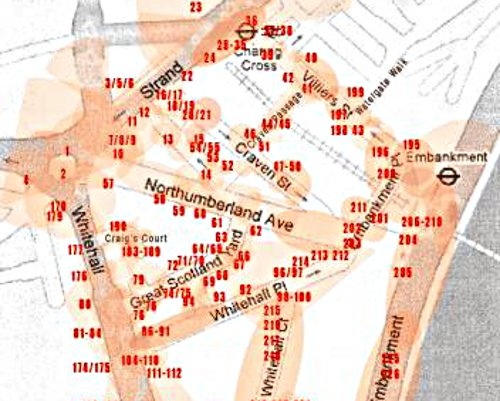

“Mapping CCTV around Whitehall”, 2008, is, as its name implies, a performance of mapping Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) security cameras around the UK’s parliament in London and a video record of that performance by Ambient.tv’s Manu Luksch.

Starting with a HAL 9000-like image of a CCTV lens, the video of “Mapping CCTV In Whitehall” has a glitchy techno aesthetic of sound and images with a post-MTV-Style Guide reportage feel. The first half consists of a recording of the police stop-and-search interviewing Luksch under anti-terrorism legislation, with a map of the area superimposed. The second half consists of CCTV views of the range of Camera number 40 being taped out, and of the people caught within those bounds. Words flash on the screen to identify the subjects of CCTV (….Artists! Sexy Arses!). This redeployment of the language of mass media visual persuasion opens up what we see rather than closing it down, making it a very effective encapsulation of the project’s ideas and aesthetics.

(One tiny criticism is that the video ends with a Creative Commons logo but doesn’t specify the licence. Artists, please at least give the licence URL, and do choose the copyleft BY-SA licence if you can…)

Wandering around to locate CCTV cameras may seem like a cosy techno-fetishist performance, a post-cyberpunk flaneur’s stroll around the streets of London with a pencil, an A-Z, and a tri-field meter. But the creeping authoritarianism of still-Thatcherite Britain makes it an act of protest against a specific law and a reversal of the assumptions of our seemingly unstoppable surveillance culture.

The Serious and Organized Crime and Police Act of 2005 criminalized political expression within an exclusion zone for a kilometre around Parliament Square. It is an indicator of the authoritarianism and assumption of privilege that has come to define political culture in the UK. It is too easy to become cynical in the face of such brazenly opportunistic ideology. If art can help to defamiliarise this in a playful and aesthetically rewarding way then it can help to undo that cynicism, and even more to go beyond it.

The assumption that the State needs to know where you are at all times, just in case you are a terrorist or a paedophile, but that you must not know the workings of the State, just in case you are a terrorist or a paedophile, is at odds with the idea of an open society. The area of London that Luksch has mapped is the SOCPA exclusion zone. A map of CCTV cameras is clearly useful to terrorists, and a map of the CCTV cameras near Parliament is clearly an act of dissent against the political consensus that constitutes domestic extremism. The police who interview Luksch touch on these ideas.

A political elite that is fearful both of and for its polity has retreated into managerial, authoritarian, paternalistic risk-management. That polity is conceived of, post-cold-war, not even economically, more nihilistically. This produces the very loss of freedom that it claims to protect against. The paradigm of government has become the watchful parent who is seen to be good by their watchful neighbours because they prevent their child ever straying into danger. But it is impossible to protect the population against all risk and this knowledge leads to impotent fearfulness. “Something must be done” and so security theatre, the spectacle of impossible systems and behaviours designed to reduce the perception of risk to zero, is used to reassure. Although whether the populace or the politicians are meant to be reassured it is hard to tell.

CCTV is part of that reassurance, of the spectacle of security theatre. The UK has the highest density of Closed Circuit Television Cameras (CCTV) in the world. The average Briton is (allegedly) captured on CCTV 300 times a day and there are more cameras in the supposedly open society of the UK than in notionally communist China. Not per head, in total. The area that “Mapping CCTV around Whitehall” focusses on is ground zero for this tendency.

CCTV doesn’t solve crime, it is used to spy on legal protest and it has been placed in school classrooms and pubs.

CCTV recordings are subject to the Data Protection Act, and from 2002-2008 Manu Luksch used personal data requests under the act to obtain the CCTV recordings of her going about her business that she used to make the film “Faceless”. The videos usually had other people’s faces blotted out to protect their privacy, which gave the resulting film its science fiction plot of people starting to lose their faces. But as Luksch was making “Faceless”, the responses to her personal data requests became rarer as the authorities adjusted the balance of power back in favour of themselves.

In 2008, Luksch returned to the subject of CCTV with “Mapping CCTV around Whitehall”, this time mapping out the CCTV cameras themselves within a particular area of London over two days. On the first day she located hundreds of CCTV cameras, on the second she measured the range of the wireless broadcasts of one of them. Part performance, part land art, this has a number of artistic precedents, from the 1960s conceptual artworks that consisted of magnetic fields or patterns of heat, to Situationists strategies for recontextualising the city by navigating it using the wrong map.

Mapping unseen electromagnetic forms was a strategy of some Conceptual Art, whether Art & Language’s landscape art infrared photograph of buried hotwires under a field or gallery-based magnetic and radio-proximity devices. Contemporary artists have used RFID tags Intangible form is irresistible for post-Duchampian attempts to keep the philosophy of art about aesthetics, and for conceptualism it is a way of keeping the artwork open. But the range of a CCTV camera is both definite and, if you have access to the camera, visual. The unseen form of the limits of its observation and the transmission of what it sees tie form to power quite directly.

In “Mapping CCTV around Whitehall” these forms and their composition are part of the landscape of the city. The city is obviously an artificial environment. In contrast, nothing might seem more natural than a painting of the landscape of the countryside. But landscape painting are depictions of valuable property for the landed gentry who commissioned them. They show and by showing make real the products of the ideology of the ruling class using aesthetics. They extend the domain of taste, a novel and socio-economically exclusionary concept, to the presentation of nature as property. They are as artificial, as culturally determined and laden, as cityscapes.

The successor to landscape painting is the “land art” of the 1960s and 1970s with its photographs of walks, mud and stones. Viewed cynically, the ‘land art’ of the 1970s is less about one man’s journey through nature than it is about cheap transport and expensive large-format cameras. It is a predecessor of the logistics art of Relationalism. The Romanticism that it shares with landscape painting is for its audience, not its commissioners. As with much art, those are two separate constituencies.

Art creates visual order and visual form for the unseen ideological order and form of the ruling class. Religious icons, jet-age land art and neoliberal Relationalism all serve this function. Critical art also depicts this ideological order, ideological form, aesthetically but to make it strange and criticise its production or content rather than to promote and naturalise it.

The Situationists treated Natopolitan 1950s Paris as a landscape to be made strange through art in order to critique the ideologies that sought to capture its population. Wandering its streets using the wrong maps was a way of challenging the authority embedded in its layout by the old regime and the new order that sought to impose its own new way of looking at things. Creating rather than using a map again re-arranges an equation, not just the equation of ‘derive’ but of the mass-media mass-politics spectacle that the Situationists were so opposed to. CCTV cameras may not seem like generators of spectacle, but their footage is used to sensationalise media reports of crime and terrorism, and their presence and visibility enforces the message that we are all part of an observed spectacle.

Radical land art sounds oxymoronic. But the aesthetics projected onto a landscape can be used as links to the ideology flattered by those aesthetics. And re-arranging the terms of land art can critique that ideology, or at least expose it to critique. “Mapping CCTV around Whitehall” re-arranges the equation of land art to make art of travelling to cameras in order to map the landscape they observe. This is a kind of critical, urban, reverse land art.

George Orwell’s vision of a mediatised totalitarian society from his novel “1984” is often used as a reference point for Britain’s surveillance culture. But this can obscure as much as it illuminates. Bringing out the true, novel, problems with CCTV surveillance as the default solution to the ruling class’s perception of society’s ills is an urgent and difficult task. As CCTV is a matter of the production and control of images, it is an area that art can usefully comment on. “Mapping CCTV around Whitehall” uses the status of art to represent the dark heart of surveillance ideology. Look upon its works…

http://ambienttv.net/content/?q=mappingcctv

Public screenings include ‘Films by Manu Luksch’ at Cinema2, Centre Pompidou (2009)

Betting on Shorts (2009)

http://ambienttv.net/content/www.bettingonshorts.com

NHK Japan (Japanese National Television, 2008), LIFT (2008)

Watch the video (160 sec, mp4) online at low-res.org

http://lo-res.org/~manu/MAPPINGCCTV.mp4

Or on Vimeo

http://www.vimeo.com/3802118

Image by Alice Alexandrescu.

This year’s edition of Artivistic brings the fields of art, politics and academia together under the theme of TURN*ON.

Eventually, the investigation about systems of representation – be they semiotic, informational or political – might slip into the one psychoanalysis considers the most elementary and surreptitious of them all: sex. That’s precisely where the Artivistic gathering got into in its fourth edition, which happened in Montreal from 15th to 17th October. To be exact, the theme under which the event tied the fields of art, politics and academia together was TURN*ON – according to its curatorial statement, ‘a fragile bridge extending, over a valley of which the depth you cannot see, to a life centered on pleasure, consciousness, togetherness, understanding, and joy’.

Formulated this way, the concept seems to be a response to the well-worn verses by journalist Eduardo Galeano, in which he states that utopia ’causes us to advance’ only because it ‘lies in the horizon’. With turn on, Artivistic proposes that the forces that move people forward and bring worlds into existence are not far away: in a scenario emptied of grand narratives, the desire (of the self?) should gain preponderance over any masterplans (of the party?).

So, if libido is the why, could we say that art is the how? As crude as it can be, this comparison makes clear that aesthetics, just as politics, mainly operate in the level of methods. They are more concerned with the way desire is manipulated (often repressed or enhanced) than with its ontological truth. Language cannot explain affect, and it shouldn’t pretend to – the best it can do is create spaces for its continuous exercise.

In that sense, what really stood out during the event were the workshops. I wouldn’t go as far as to agree with the idea that such activities are a distinct genre within the contemporary art circuit. Workshops indeed revitalize the exhibition space – however, they do so not by occupying it with new forms, but by proposing new forms of occupying it. In Artivistic, these interfaces ranged from diy electronics and card game design to pornographic filmmaking and even a kind of un-workshop on workshops! Among those, there was a remarkable amount of projects concerning the performative of one’s own identity.

In fact, the workshops punctuated Artivistic in a not much different way than the everyday activities of cooking and eating in group (or translating things to French or English – it was a true bilingual event). One thing led to another, keeping the gathering together in spite of the healthy excess of participant autonomy allowed by the organization crew. Of course, the concentration of (almost) all activities in the same place helped building this integration. This was a strategic option, very coherent with the intimate theme of this edition; the former Artivistic, about un.occupied spaces, had been distributed in different venues throughout Montreal.

The integration of the participants was so successful it had the minor side effect of creating an almost self-centred environment. Even though some activities would have been very interesting for people outside regular art-audience, it was hard to see among the public someone besides those that were immersed 24/7 in the event. For instance, it was a pity that the orgasmic birth workshop, which introduced alternative ways of pregnancy and labour, had no pregnant women participating.

This paradoxical isolation was imploded in the last night of the event – most ironically, not by the long-waited closing performance Resist Me Release Me: Turn On Act On, which artist Shu Lea Cheang had been organising with the participants throughout the gathering, but because of its impending cancellation. It seems that the managers of the venue where Artivistic was happening had not understood that the event would contain nudity and explicit sexual acts, and took account of this just in time of the final soiree. Since they had no public license to host this kind of activity, they said it was impossible to have the performance there: either it had to be suspended or transferred elsewhere.

The organizers explained this incident to the participants and called for a collective decision. That immediately ignited a very intense discussion, where it became clear that what was at hand was not mere censorship, but a very subtle negotiation of the different spheres that Artivistic addressed. The autonomy people were requesting was not sexual, but artistic – ‘we do not intend to do an orgy, but performances’, as someone said. Hence, it was not a simple conflict between raw libidinal impulse and oppressive morality; it concerned more complex, structured systems – i.e. art and Montreal society, both already contradictory in themselves.

I dare say that some solutions proposed in this debate – for example, live-streaming the works from another place or ‘censoring’ performances in real-time – were way more interesting than any prescripted show might have been. These proposals were the sign of an art that was alive and kicking, ready to respond emergencies and fight back, instead of just claiming its secular, innocuous freedom (a freedom that critic Julian Stallabrass very cunningly regards as supplementary to that of the market).

The result was that in a couple hours the whole programme for the night was adapted and moved to a venue nearby, in a beautifully orchestrated, self-organized effort. Unfortunately, due to limitations of structure and space, not everything that had been planned before could be presented. Nevertheless, the accident had allowed the necessary hands-on without which a turn on just fades away, and something bigger was engendered in the process – I’d say revolutionary freedom, a kind of autonomy that, as the old leftist maxima states, must always be conquered.

Links: