Featured image: Spork patient rights (jpeg copy). Millie developed Spork who experienced all manner of catastrophes.

Download PDF of The Last Collaboration

The Last Collaboration comprises the joint fatality review of Millie Niss’s final illness in a Western New York hospital’s ICU by mother and daughter, Martha Deed and Millie Niss in 2009. Furtherfield could scarcely have chosen a more significant time to reintroduce the collaboration.

As is the case for hundreds of thousands of people in this year of COVID-19, Millie’s story has no happy ending. In fact, those who knew and loved her were forewarned that Martha could not compose an upbeat conclusion to the recounting of Millie’s final illness.

2020 is also the year in which the web art so central to Millie’s life will end as well. In this, as in her death from a virus that could not be avoided, Millie also is not alone.

In fact, in parallel to steps Millie took to make sure the story of her illness and death was told in The Last Collaboration, Millie also anticipated the need for future upgrades to her award-winning Erewhon installation.

News from Erewhon, in its initial incarnation is an example of Web Art 1.0 with a slight leaning towards 1.1 because we exploit Google Image search: We display our text with our design. In Erewhon 2.0, we propose to do what older websites have had to do: upgrade from 1.0 to 2.0 whilst preserving the essence of Erewhonicity and without alienating users. Thus, instead of a single URL in a web journal, there will now be a profusion of Erewhon web installations hosted by us and by others. . . (Millie Niss. &Now talk, October 15, 2009)

What Millie did not anticipate, despite her knowledge that she might not have many years ahead of her, was that she would not be able to meet the goal of protecting her work from future changes on the web or with her tools, such as Flash and Actionscript. She died six weeks after delivering her talk.

Martha constructed The Last Collaboration from a collection of circumstances and documents not ordinarily available for a family to review. Family members can keep logs of their observations and conversations with hospital personnel and with their family member patients. They can collect medical records. However, Millie’s documentation of her month in the ICU is nearly unique.

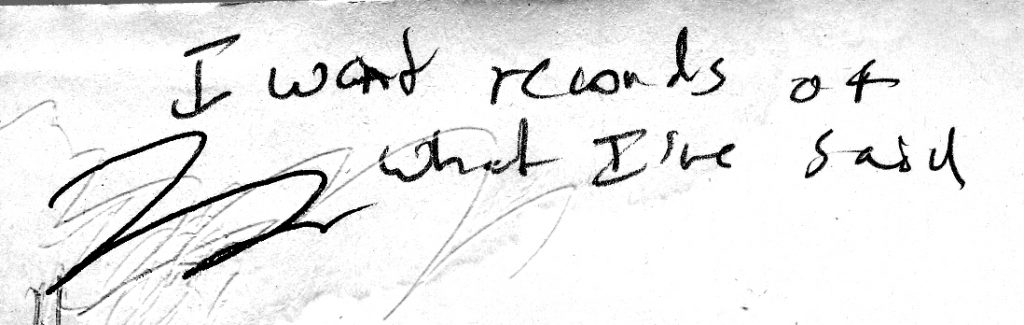

Millie suffered respiratory arrest within an hour of entering the ER, was resuscitated and placed on a ventilator. But she did not require sedation. Millie couldn’t speak while on the ventilator. Thus, with her oxygen supply restored, and her computer in front of her or with pencil and notebook in hand, for the next four weeks, she sent reports home, posted emails, and ‒ perhaps most important ‒handwrote her side of every conversation with her family or medical staff. When filled, each notebook was sent home for safekeeping, because Millie wanted her story told. These notebooks are dated and can be linked to her medical record. Thus, both sides of her conversations with medical staff are recorded. Millie’s communications in writing can be lined up with progress notes and medical reports to assess whether staff understood the significance of what Millie reported to them.

Millie had struggled with chronic illness that had left her bedridden for several years. She had regained sufficient strength to apply with Martha, her mother, to present at &Now, an international e-poetry conference held in Buffalo, NY. With power wheelchair and oxygen and the help of her aides and family, she had made that presentation. But there was a terrible irony, given our world’s current struggle with COVID-19.

This was October 2009, and there was a major outbreak of H1N1 in the city. Because a vaccine was on the way, but not yet available, local public health officials decided not to announce the outbreak to avoid panic. Only after a dozen or more people, including Millie, had died from H1N1, was the public informed.

Millie and Martha discovered the outbreak when Millie arrived at the ICU, which normally had approximately 20 beds for non-heart patients. Seventeen patients were on ventilators (instead of the usual 3-5), the coronary care ICU had been reduced to accommodate desperately ill patients arriving with H1N1. Patients were forced to remain in the ER until the beds and other equipment were retrieved from storage and set up.

Millie’s presentation of her new work, work which excited her because it represented a significant advance in her technical skills led her into H1N1’s path and contributed to her death.

And here is the irony to top all others: Erewhon itself will soon disappear. Millie constructed it in Flash and Flash Actionscript, stretching those utilities to their outer limits. And now, the presentation of that project, which was groundbreaking for her, not only is Millie, the author, gone, but in an act of willful obsolescence by Adobe, the work itself also will soon be gone. Although the dire messages of Flash’s demise are somewhat contradictory, it appears that the work may not even be viewable downloaded onto laptops and viewed off the web.

To a web artist like Millie, what is happening to her work as well as the work of many others who used Flash when Flash was cutting edge technology, is akin to paper manufacturers decreeing that libraries may no longer use paper in their collections.

Three years’ notice is hardly adequate to ensure the work of those early artists, some of whom are no longer here to protect their work.

Impossible to know whether Millie, had she anticipated the early death of her project, would have been willing to risk her impaired immune system to make her &Now presentation in 2009, even absent H1N1 rampant in the community. She had been shut-in for years, as many have been shut in for many months in 2020, due to her risk of death if she had caught a common cold.

Almost certainly, if Millie Niss were here today, she would be coding her own language to preserve her work.

Reading The Last Collaboration in 2020, it is possible to see that changes in health care have improved, particularly in the area of hospital acquired infections (HAI) and medical staff communication with family. The importance of coordinatated, accessible and affordable health care remains critical. Perhaps the most important contribution Martha and Millie’s account makes today when families are often excluded from visiting family members seriously ill from COVID-19, is the picture it presents of life in the ICU.

Featured image: The Last Collaboration, cover image

Read The Last Collaboration online

“The United States loses more American lives to patient safety incidents every six months than it did in the entire Vietnam War.” Edward Picot introduces The Last Collaboration an art documentary book by artists and poets Martha Deed and Millie Niss. This work is a construction of Millie’s hospital experiences in the last hospital she ever visited. The story is told through Millie’s notes, emails, the daily diary she sent home, her posts on her Sporkworld blog, her mother’s log, and Millie’s medical records. These primary, often raw, documents are framed with medical notes and clinical guidelines as well as the outcomes of two NYS Department of Health investigations of Millie’s care. Millie wanted her story told. She wanted an autopsy performed if she died. Because of the autopsy, we have the story.

At 09:57 on the morning of 15th November 2009, Millie Niss sent an e-mail from her hospital bed to her parents:

…they have an inexperienced person treating the sickest patients… and by the time she knows enough to do a good job, she is burned out & ready for a part time practice. They should have inexperienced doctors treat the least sick patients, not the sickest ones… This is true in every specialty and I am sure patients die as a result.

She had been in hospital for two weeks, by her own account she had already come close to death, and in another two weeks her life would be over. Already she was unable to move, catheterised, usually in pain, and on a ventilator which prevented her from communicating verbally. Not many patients in her position would have the energy to analyse their own care, never mind write down their conclusions so lucidly. But Millie was no ordinary patient.

She was a writer and new media artist: she had been seriously ill with Behcet’s Disease for years – virtually a cripple – but her artistic powers were undiminished, and with the help of her laptop and the internet she continued to work and communicate. When she was admitted to hospital with swine flu, it still didn’t stop her writing and thinking. She actually sent off a contribution to a new media project from her hospital bed. She listened to WNYC during the day and BBC4 at night. She couldn’t talk, but she kept up a constant stream of e-mails and handwritten notes – to hospital staff, to her parents, and to friends online. She wanted to record everything and comment on everything. If she died – which she could always see was on the cards – then she wanted an autopsy, and she wanted the story of her death to be told.

The remarks quoted above show how acute she could be. She has put her finger right onto a recognised problem of healthcare – that the most complex and stressful cases are often looked after by the least experienced practitioners. Senior doctors are often all too glad to distance themselves from the front line as soon as they get the chance. In a way this is completely understandable, but as a result front line work is frequently characterised by an atmosphere of muddling through, which can rapidly degenerate into bluster, hysteria, bullying and panicky incompetence when the going gets tough.

This book is an account of Millie’s experiences at the front line during her final illness. She was hospitalised in New York State, but I can recognise many of the problems described herein from my own experience of the NHS in England, where I have worked in a doctor’s surgery for more than twenty years. The story has been assembled by Martha Deed, Millie’s longtime collaborator and Mom, using not only Millie’s e-mails and jottings, but her own own notes made at the time, her reflections since (which often take the form of poems), and the results of her subsequent investigations and complaints. In artistic terms the different elements are blended and balanced with great skill, and we find ourselves shuttling between documentary evidence, poems about bereavement, first-person narratives and nature-notes about birds, without any sense of incongruity or disjunction. The story unfolds both in the present tense and in flashback, both from Martha’s point of view and from Millie’s. It is a shocking depiction of how badly things can sometimes go wrong in a hospital.

Doubtless the hospital would argue that this is a one-sided account. They would also say – indeed, in their response to Martha’s complaints they did say – that Millie was not the easiest patient to care for. And leaving Millie’s case on one side for a moment, it has to be admitted that caring for the sick, especially in a hospital, is an extremely difficult job. Unreasonable behaviour from patients may not be the norm, but it is certainly commonplace. At least in a doctor’s surgery you can get to know your clientele over a period of years, and they can get to know you. In a hospital the turnover is much higher, and bonds of trust are correspondingly more difficult to form. People are generally sicker, which makes them more stressed; and relatives are more worried, which makes them more demanding. Furthermore some people simply cannot accept the realities of ill-health and death, and lash out or place blame as a means of relieving their feelings. Perhaps it’s not surprising, therefore, that some hospital employees come to regard the patients – and their families – with a mixture of nervousness and resentment rather than sympathy and helpfulness.

The best carers can deal with tricky customers without losing their cool. They avoid getting into confrontations and status-competitions with the public, and they treat the people they don’t like with the same meticulous care and respect as the ones they do. They are not only skilled and sympathetic, but detached enough to keep a sense of perspective at all times. They make good decisions in pressurised circumstances. They communicate clearly at every stage of the caring process. They admit their own shortcomings and seek expert help when they need it, instead of trying to bluster and bluff their way out of difficulties. Unsurprisingly, a lot of employees in the health service fall a long way short of this ideal; but what is less excusable is that some of them don’t even recognise it as the ideal for which they should be aiming.

What these pages make painfully clear is that although hospital staff are supposed to treat all patients the same, they can sometimes be prejudiced against certain types, for example the obese, who are often regarded as having created their own health problems. Furthermore, although they officially welcome questions and comments, in practice they tend to prefer grateful submissiveness, and there are those who interpret anything else as troublemaking.

Of course, Millie’s story mustn’t be taken as representative of what’s likely to happen to anyone who goes into a hospital, either in the UK or the USA, and it mustn’t prevent us from realising how hard people in healthcare generally work – a lot of them for not very much money – or what an invaluable job most of them do.

All the same, the situations described in this book will strike a chord with many people both inside and outside of the health care sector. One thing it lays bare is that the psychology of caring can be a disturbing subject. We are such touchy creatures, so desperate to justify ourselves and not lose face, so anxious to get the better of anyone who seems to pose a challenge, that in no time at all, even when another person’s health is at stake, we can forget our duties and become embroiled in a petty struggle for the upper hand. Furthermore power corrupts, and a health care worker is in a position of power, able to grant or deny favours, wielding the authority of the surgery, the hospital or the System itself.

And then there is the impossible-to-ignore feeling that the patients are making our lives a misery by forcing their demands upon us. Even outside the health system, when we are caring for our loved ones, our concern for them is rarely untainted with resentment – why can’t they leave us alone instead of pestering us for help all the time? So what chance is there that staff in a doctor’s surgery or on a hospital ward will be able to avoid upsurges of ill-feeling towards the patients, particularly when things get difficult? And once they have taken a dislike to someone, they may subject that person to obstructiveness, bossiness, bullying, uncaring treatment or even cruelty.

Hopefully, to recognise these impulses and their grounding in normal human feelings is the first step towards controlling them. Unfortunately, people coming into health care are usually given very little training in its psychological aspects, and what training they do get tends to be so simplistic that it’s difficult to apply in real-life situations.

Furthermore what happens on the front line, as Millie so shrewdly observed, is very often a knock-on consequence of organisational decisions made higher up. If senior members of staff use their seniority as an excuse for distancing themselves from the most stressful and difficult areas of work, then those areas are going to be looked after by juniors. Mistakes are more likely to be made, and although the senior members of staff won’t be the ones making them, they will be indirectly responsible.

In badly-managed organisations leaders and decision-makers tend to become detached figures issuing edicts from ivory towers, and because of their detachment those edicts become increasingly abstracted from the realities of working life. “Ordinary” members of staff are left to muddle along as best they can. Organisations like this are often characterised by high-sounding written policies which nobody ever reads or puts into action – and there are examples of such policies in this book.

In the best-run teams, leaders and decision-makers do not become separated from the rank-and-file: everybody communicates with everybody else, everybody plays a part in the decision-making process, everybody knows what’s going on and continuity of care is ensured. But this book shows what can happen at the other extreme: fragmentation of care, no coherent plan, rogue individuals doing pretty much what they like, poor communication, needless delays, and ultimately fatal errors.

Then there are the questions of incompetence and cover-ups. Nobody is immune from making mistakes, and the best individuals and institutions are able to recognise them and learn from them. Yet people in all walks of life just as frequently react to criticism with defensiveness and self-justification, or by simply brushing things under the carpet. Again, these are perfectly normal reactions in a way: no matter how rewarding it may be to learn lessons from our own failures, it is always an uncomfortable process, and our first impulse tends to be either to deny them or hurry away from them as soon as possible. In the health service this reluctance to acknowledge mistakes can shade into blaming patients for their own difficulties, or trading on the disinclination of relatives to trawl through the details after someone has died. The death of a mismanaged patient can even come to be regarded as a desireable outcome, since it usually has the effect of silencing criticism and drawing a veil over people’s mistakes. All of these things seem to have happened where Millie was concerned.

Needless to say, given its subject, this book can be a tough read at times. But it’s full of insightful comments – here are just a few examples:

Do not confuse personality or communication skills with medical competence. It’s great to have both, but the more important quality – absent personal nastiness – is medical competence. [Martha]

I have also gotten a lot of good care, but once you die or are terribly damaged it is too late to say “Most of the care was ok”. [Millie]

You would not believe how nasty nurses can be to people who are very sick and helpless. [Millie]

I am sorry, my dear,

but the leg you say is broken because it looks all twisty and it hurts…

is not broken

because we have met our broken leg target for the month.

[Martha]

As these quotes show, the style in which the book is written, even when the subject-matter is at its grimmest, is always natural and engaging. And although, in places, the narrative shows us some unsavoury aspects of human nature, Millie is such a living presence, and the relationship between her and her mother comes across so powerfully, that what we are left with in the end, paradoxically, is a sense of affirmation.

It is encouraging to learn that a medical professor in the USA is already planning to use The Last Collaboration as a training aid. It could well prove invaluable, not only as a cautionary tale of how things can go wrong in the health care system, but as a tremendously vivid insight into what it feels like to be on the receiving end when they do. Given the choice, Millie would undoubtedly have preferred to escape with her life rather than achieve this particular form of immortality. Nevertheless, she would certainly be gratified to know that her story was making a difference. It is a story which she desperately wanted to be told, and which needed to be told for the good of the health service and its patients. And almost all of us will be its patients one day.

—

Read Edward Picot’s article about Millie Niss on Furtherfield